- School of Statistics, Shandong Technology and Business University, Yantai, China

This study constructs an evaluation system incorporating the four chains of talent, innovation, industry, and capital to measure marine new-quality productivity across 11 coastal provinces in China from 2011 to 2022. Using entropy weighting, kernel density estimation, and fuzzy-set Qualitative Comparative Analysis (fsQCA), the study analyzes the spatiotemporal evolution and policy-driven pathways of marine productivity. The results indicate an overall upward trend in marine productivity with significant regional disparities. High-level regions exhibit synergistic policies across the four chains, while medium- and low-level regions face constraints due to insufficient talent and capital support. The policy focus has shifted from industry-led development to innovation-capital synergy, providing empirical support for differentiated policy design to promote coordinated regional development of marine new-quality productivity.

1 Introduction

The ocean economy has become a key driver of global economic growth, especially in coastal countries where marine industries play a crucial role in resource provision, energy development, and international trade. However, rapid development has also led to challenges such as environmental pollution and ecosystem degradation, highlighting the need for sustainable development.

The concept of “marine new-quality productivity” was first introduced by Xi Jinping, general secretary of the Communist Party of China (CPC) Central Committee, during his inspection tour in September 2023. It emphasizes the importance of advancing marine industries through innovation, environmental protection, and sustainable development. China has accelerated the implementation of its “Marine Power Strategy,” which promotes institutional innovation and policy guidance to ensure the high-quality development of the ocean economy. Since the 20th National Congress of the Communist Party of China, the concept of “new quality productive forces” has been central to transforming economic development models.

Marine new-quality productivity emphasizes technological innovation, skilled human capital, a modern industrial system, and a functioning financial system as key elements. This approach aims for breakthroughs in technologies, improvement of industrial linkages, and optimization of talent structures. Despite the growing literature on marine productivity, there is still a gap in understanding how policies influence the development of marine new-quality productivity. Since the 18th National Congress, Xi Jinping has emphasized the importance of integrating the four chains—talent, innovation, industry, and capital—in driving high-quality development. However, empirical studies on how these chains converge to affect marine productivity disparities remain limited.

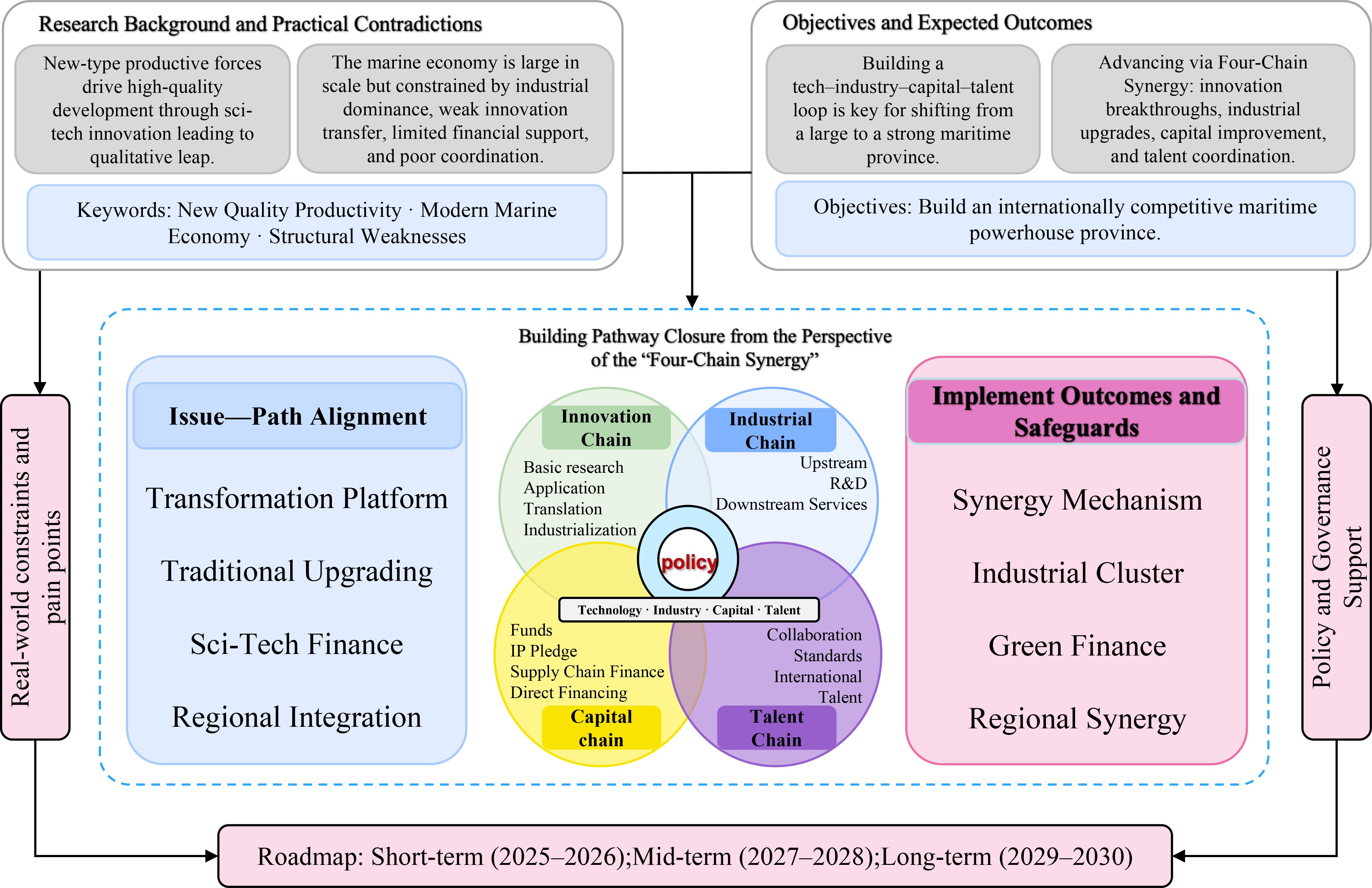

In summary, this study proposes a theoretical framework for marine new quality productivity from the perspective of four chain integration, and constructs a corresponding evaluation index system. Figure 1 shows this four chain collaborative framework, which includes four main parts: industrial chain, innovation chain, talent chain, and capital chain. This diagram vividly illustrates how these four chains interact with each other. The industrial chain lays the foundation for the expansion and structural upgrading of the marine economy, the innovation chain is the core for promoting technological research and achievement transformation, the talent chain focuses on the cultivation and application of marine talents, and the capital chain supports the development of industries and innovation through financial support, investment, and financing conditions. These four chains work together to promote the improvement of regional marine productivity through their interactions.

2 Related works

The development of marine new-quality productivity has gained increasing attention in recent years, driven by the need for sustainable growth in the ocean economy. This body of research spans multiple dimensions, including the ocean economy’s role in global trade, the theoretical foundations of new-quality productivity, the four-chain synergy model, and the impact of policy frameworks.

2.1 Ocean economy and sustainability challenges

The ocean economy is recognized as a key driver of economic growth, particularly in coastal regions, where marine industries contribute significantly to resource provision, energy development, and international trade (Ahammed et al., 2025; Brenton et al., 2022). However, rapid industrial development has led to environmental challenges such as pollution, overexploitation of resources, and ecosystem degradation (Carroll et al., 2024). These issues threaten the balance between economic growth and environmental sustainability.

Studies suggest that the integration of innovative technologies, environmental protection measures, and green development pathways is crucial to addressing these challenges (Curry et al., 2021). In particular, the decarbonization of maritime transport is a critical frontier; the effectiveness of current carbon emission control measures in international shipping warrants careful examination to align economic activities with global sustainability goals (Xu et al., 2025c). The role of technology and sustainability in the marine economy has been explored, with some studies emphasizing how digital and technological innovation can foster a sustainable transformation of marine industries (Jiang et al., 2025). Moreover, policies promoting innovation and environmental governance are vital to facilitating this transition (Zhou et al., 2025a).

2.2 New-quality productive forces and four-chain synergy

The concept of new-quality productive forces, which incorporates technological innovation, industrial modernization, human capital, and financial systems, has been proposed as a guiding framework for economic transformation (Han and Deng, 2025; Onkelinx et al., 2016). In the context of the marine economy, these elements support technological advancements and industrial upgrades, contributing to the overall productivity of coastal regions (Sha et al., 2025; Ji et al., 2024).

The integration of the four key chains—industrial, innovation, talent, and financial—has emerged as a central mechanism for driving high-quality marine development (Bhati et al., 2025; Duan et al., 2024). The synergies between these chains are fundamental for optimizing productivity in coastal economies, yet research on their interaction is still limited. Emerging studies provide valuable insights into this synergy. For instance, evaluations of emerging Arctic passages consider multifaceted factors to assess navigation capacity, directly engaging with the optimization of industrial and innovation chains under new geopolitical and climatic conditions (Xu et al., 2025b). Simultaneously, at the micro-supply chain level, research on marine green fuel coordination demonstrates how contractual mechanisms like cost-sharing and revenue-sharing can align the interests of different stakeholders, illustrating a practical model for integrating the industrial chain with the financial chain to promote green transformation (Xu et al., 2025a). Studies focusing on regional disparities in marine productivity highlight the challenges faced by less developed areas, such as insufficient financial support and talent shortages, which hinder their ability to benefit from these synergies (Xiu and Lis, 2024). Recent work in maritime logistics and resource allocation provides insights into optimizing the four chains, with emphasis on the integration of innovation and financial mechanisms to promote balanced development across regions (Zhuo et al., 2025).

2.3 Policy and institutional innovation

Policy frameworks play a critical role in the development of marine new-quality productivity. The integration of industrial, innovation, talent, and financial chains, often driven by policy, is seen as a key mechanism for regional economic growth (Dominguez-Diaz et al., 2025; Zhang and Yi, 2024). The Chinese “Marine Power Strategy” has underscored the importance of such policy-driven mechanisms, promoting institutional innovation as a core driver for sustainable marine development (Chen et al., 2023; Zhang et al., 2023). Comparative studies reveal that regions with comprehensive policy frameworks, combining subsidies, innovation incentives, and digital platforms, tend to exhibit higher productivity levels (Chen and Huang, 2023; Seidl and Nunes, 2021). The synergy between policy, technological development, and institutional innovation is pivotal in fostering a resilient and sustainable marine economy. The effectiveness of policy-driven mechanisms has been demonstrated in various sectors, where institutional innovation and multi-stakeholder collaboration have proven to enhance systemic efficiency and sustainability (Zhou et al., 2025b).

2.4 Summary

In summary, while significant progress has been made in understanding marine new-quality productivity, as evidenced by recent studies on specific issues like shore-to-ship power, shipping emissions, more research is needed to explore how the interaction among the four chains influences regional productivity disparities. By integrating insights from the literature and incorporating new perspectives from interdisciplinary studies, this research aims to further examine the synergies between the four chains and their role in enhancing marine economic growth, with a focus on policy-driven pathways.

3 Construction of theoretical framework and indicator system

3.1 Marine new-quality productivity: a four-chain view

Marine new-quality productivity is a key manifestation of advancing high-quality marine economic development under recent China’s national development strategies. Its essence lies in shifting from factor-driven growth to innovation-driven, capital-empowered, and talent-supported progress through factor upgrading and structural optimisation. Compared with conventional marine economic development, it stresses the synergy of technological innovation, talent cultivation, industrial coordination, and capital support.

From the four-chain integration perspective, it takes the industrial chain as the foundation for industry expansion and structural upgrading; the innovation chain as the core to strengthen research and technology transfer; the talent chain to enhance cultivation and application of marine talent; and the capital chain to improve fiscal input, investment, and financing conditions. These four chains interact and advance together, shaping the overall framework of regional marine new-quality productivity. This integration embodies the “Innovation-Driven Development” and “Maritime Power” strategies, and aligns with the requirements of successive marine economic plans since the 12th Five-Year Plan.

3.2 Four-chain based indicator construction

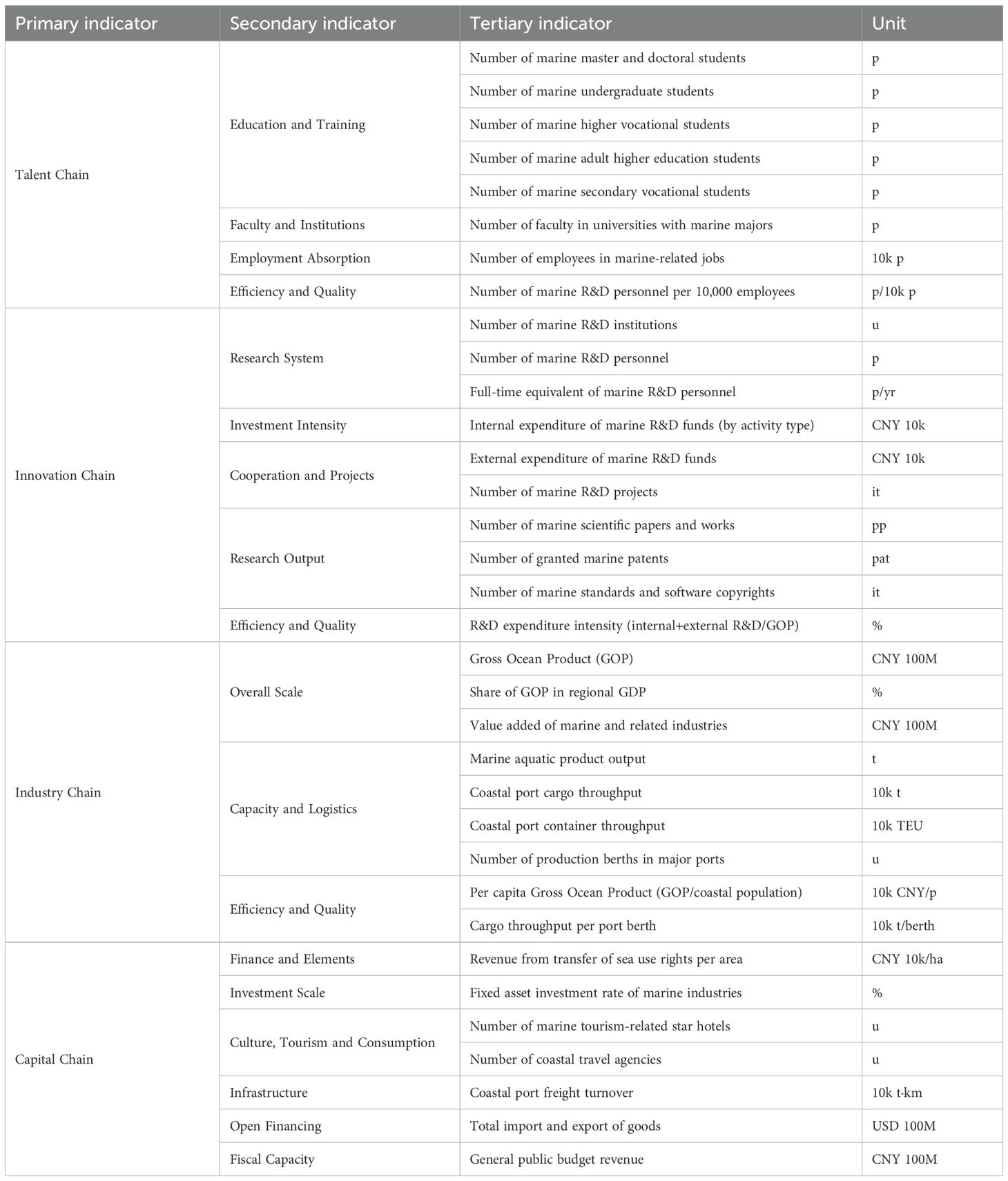

To characterise regional marine new-quality productivity, this paper develops an indicator system integrating industrial, innovation, talent, and capital chains. The selection of indicators follows the internal logic of productivity transformation and the practical demands of marine development. The specific indicator settings are as shown in Table 1.

a. Industry Chain: Indicators capture both the scale and efficiency of marine industries, reflecting how production capacity, circulation, and port infrastructure form the material basis of regional productivity.

b. Innovation Chain: Emphasis is placed on knowledge creation and application. Indicators of R&D inputs, organisational structures, and achievement transformation reveal innovation’s role in upgrading industries and sustaining competitiveness.

c. Talent Chain: Measures concern the cultivation and absorption of human resources across multiple education levels and employment channels, highlighting talent as the fundamental driver of productivity enhancement.

d. Capital Chain: Indicators reflect fiscal strength and openness, covering investment, financing, and external linkages, to show how financial capacity and institutional support provide conditions for industrial and innovative growth.

Overall, the four-chain framework moves beyond a simple aggregation of variables, aiming instead to reflect the structural logic of marine new-quality productive forces and to provide a systematic basis for regional evaluation and comparison.

4 Methods and data

4.1 Measurements methods

4.1.1 Entropy weight method

The entropy method is an objective weighting approach derived from information theory, which determines indicator weights based on the degree of data variability (Sha et al., 2025). Greater variation in an indicator implies more information and a higher weight, thereby reducing subjective bias in the evaluation process. In this study, it is used to determine the weights of the four-chain indicators, providing an objective basis for measuring the level of marine new-quality productivity.

4.1.2 Kernel density estimation method- KDE

KDE is a non-parametric method for estimating the probability density function of a random variable (Mood, 1950). By applying a smooth kernel function to each data point, it constructs a continuous density curve that reflects the distribution characteristics of the data. This method helps reveal the dynamic evolution and regional disparity of marine new-quality productivity over time, offering a more intuitive understanding of its distributional patterns.

4.1.3 Fuzzy set qualitative comparative analysis-fsQCA

FsQCA is a configurational approach that combines qualitative and quantitative analysis to examine how combinations of conditions lead to a particular outcome (Verweij, 2013). It transforms variables into fuzzy-set membership scores between 0 and 1, allowing the analysis of causal complexity and multiple concurrent pathways. In this paper, fsQCA is employed to identify typical policy configuration paths that enhance marine new-quality productivity across different regions and periods.

4.2 Data sources

4.2.1 Indicator data related to new marine productive forces

Based on China’s national conditions and the implementation context of the “Twelfth Five-Year Plan”, “Thirteenth Five-Year Plan”, and “Fourteenth Five-Year Plan”, this paper selects relevant indicator data on marine new production capacity from 11 coastal provinces from 2011 to 2022 for research. Due to the complexity of constructing this indicator, multiple data sources are involved, covering a wide range of fields, mainly including official statistical materials such as the “China Marine Economic Statistical Yearbook” and the “China Fisheries Statistical Yearbook”.

4.2.2 Policy data related to marine economy

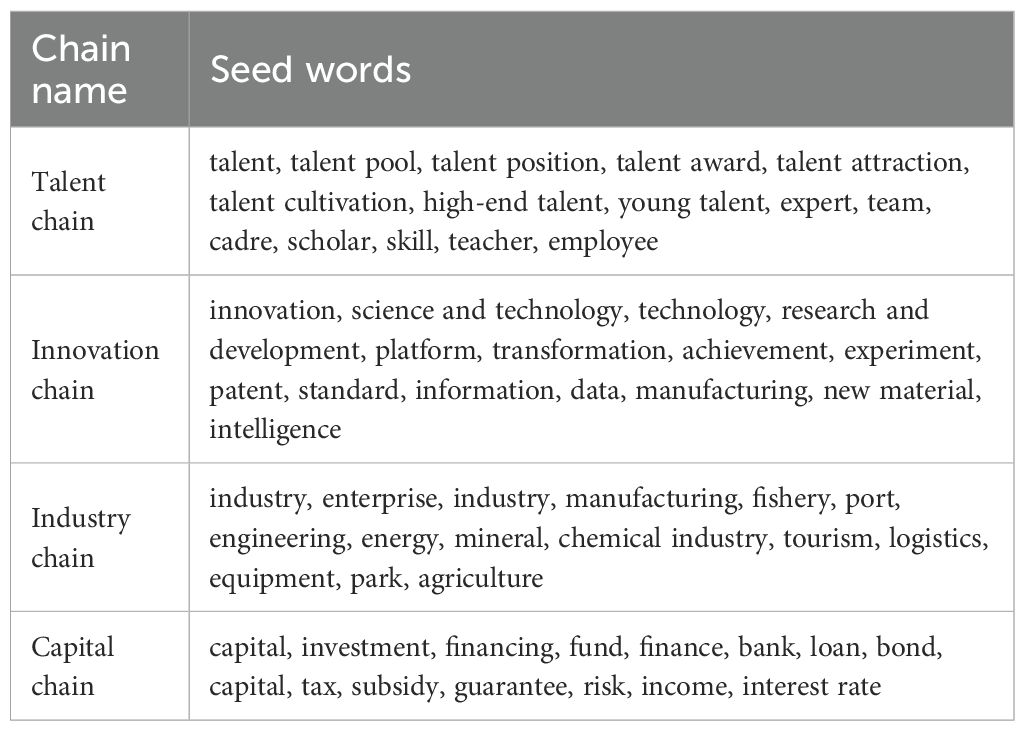

Based on the research needs in the field of marine economic policy, this paper focuses on four chains: talent, innovation, industry, and capital, and constructs 12 related seed lexicons respectively. The construction of these lexicons is based on the core elements of marine economic development, and combines China’s policy orientation towards the marine economy in recent years. The specific seed word libraries corresponding to each chain are shown in Table 2.

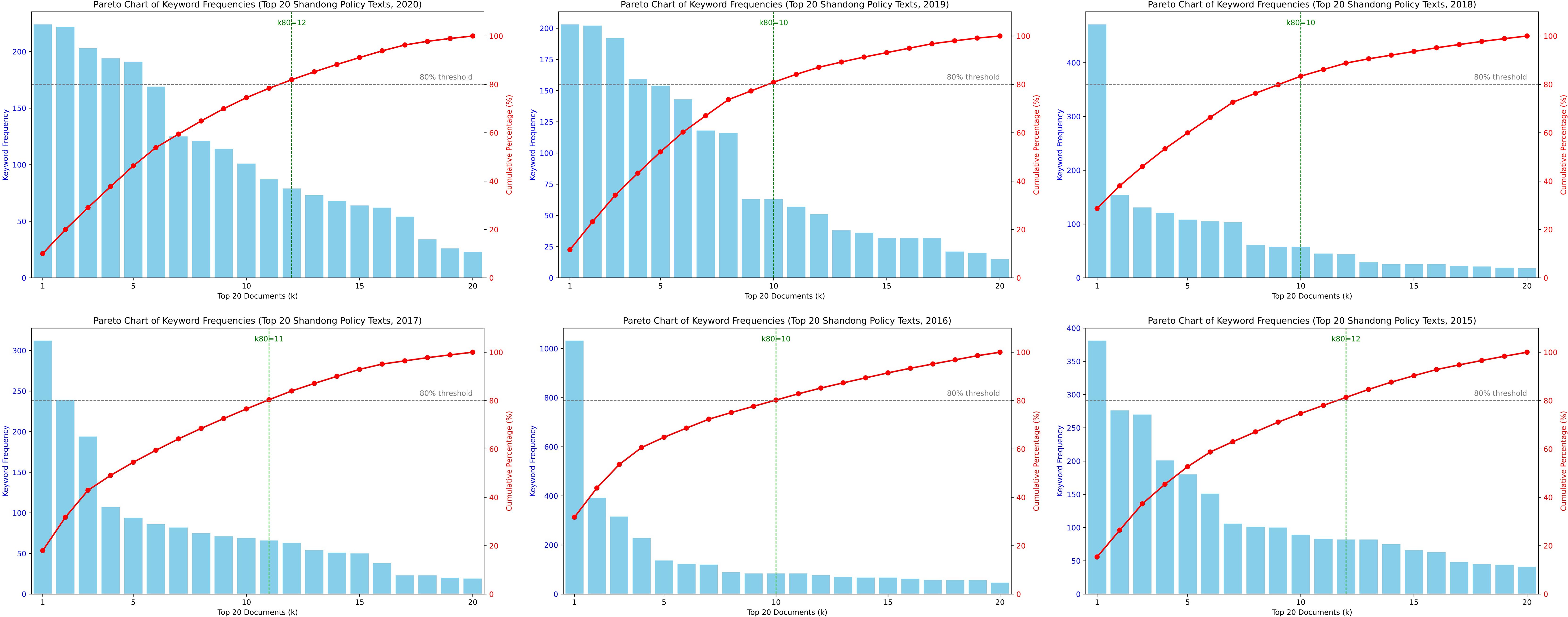

In the process of collecting policy texts, firstly, we visit websites such as “Peking University Treasure” and official websites of provincial governments to calculate the frequency of occurrence of five keywords using Equation 1, (including “ocean”, “talent”, “innovation”, “industry” and “capital”) in the policy document, which serves as the basis for evaluating the relevance of the document to marine new quality productivity and the four chains.

where d represents a policy document.

Specifically, we drew a Pareto chart of the top 20 policy documents with the highest frequency of keywords each year (taking Shandong Province as an example, the Pareto chart for the past 6 years is shown in Figure 2). The top ten documents can cover about 80% of the keywords. Therefore, in order to avoid data redundancy, we selected the top 10 policy documents with the highest relevance each year from the documents released by each province from 2011 to 2021. This process ensures the comprehensiveness and representativeness of the selected policy text in terms of content, covering all key aspects of the marine economy field. To ensure the authority of the data, all selected policy documents are official documents released by provincial governments, which largely reflect the latest policy developments of local governments in the development of the marine economy.

Figure 2. A set of Pareto charts showing the keywords contained in the policy documents issued by Shandong Province in each of the past six years.

In order to measure the degree of government attention to marine policies, we define four chains (talent chain, innovation chain, industry chain, and capital chain) with their corresponding sets of seed words. Let denote the total frequency of occurrence of seed words belonging to chain c in all provincial government policy documents issued in year t. Let the total frequency of all seed words across all chains in year t be defined as . Then, the policy attention intensity of a provincial government to chain c in year t is given by Equation 2.

where ranges between 0 and 1, indicating the relative degree of attention the government paid to chain c in year t.

5 Results

5.1 Calculation results of regional marine new quality productivity

This subsection employs the entropy method to measure the marine new-type productivity of 11 coastal provinces from 2011 to 2022. As shown in Table 3, overall trends demonstrate gradual upward trajectories, though regional disparities remain pronounced.

Temporally, during the 12th Five-Year Plan period (2011-2015), overall levels remained relatively low, with eastern coastal provinces establishing an early lead. The 13th Five-Year Plan period (2016-2020) saw Jiangsu, Zhejiang, and Shandong narrow regional disparities through innovation-driven development. Since 2021, under the “maritime power” strategy, core provinces like Shanghai and Guangdong have consolidated their leading positions. Spatially, Shanghai and Guangdong maintain comprehensive advantages in industry and innovation chains. Shandong and Zhejiang rank in the upper-middle tier with enhanced competitiveness, while Jiangsu has approached the high-level group in recent years. In contrast, Hebei, Guangxi, and Fujian lag significantly due to constraints in industrial foundations and talent concentration.

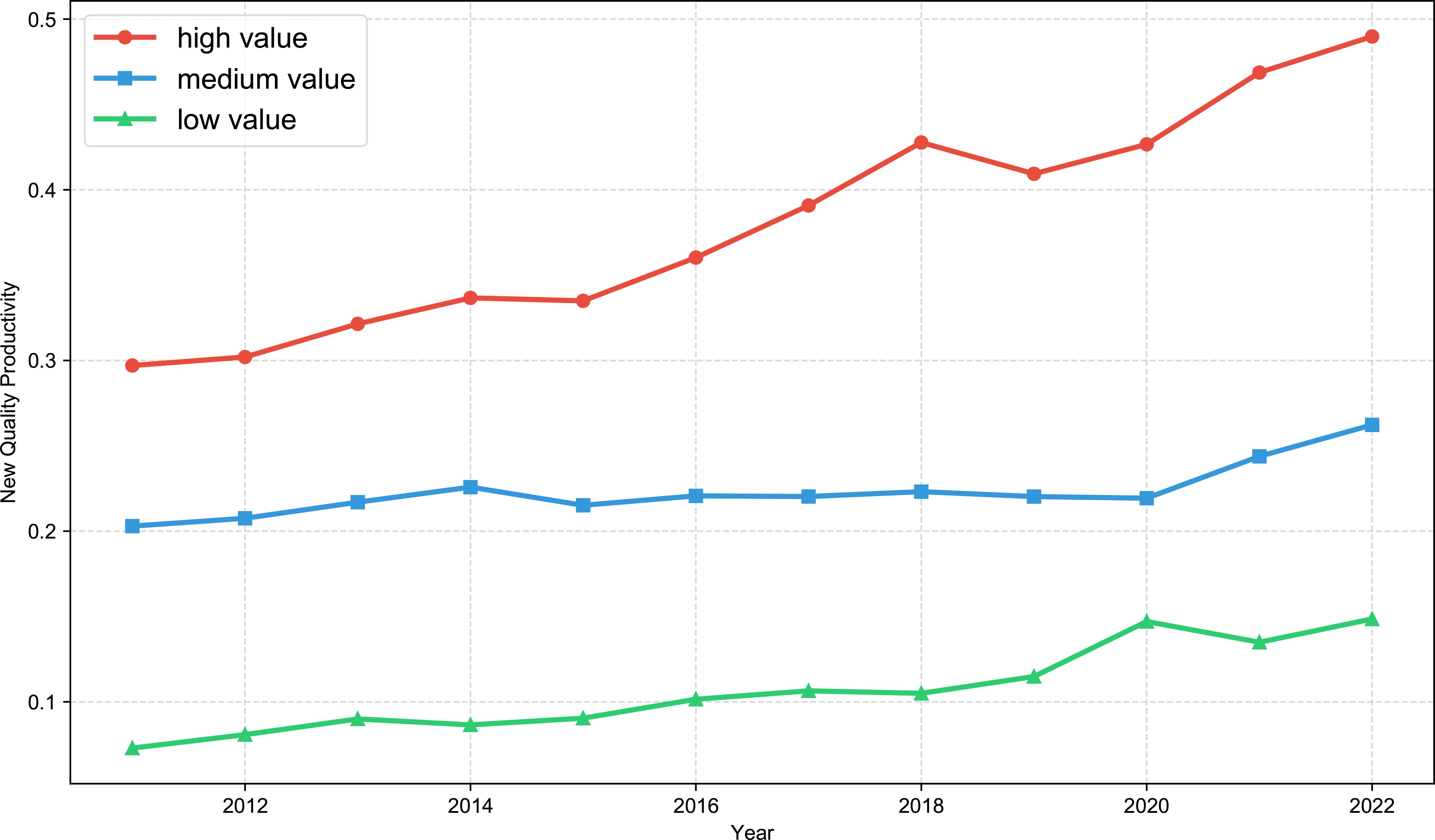

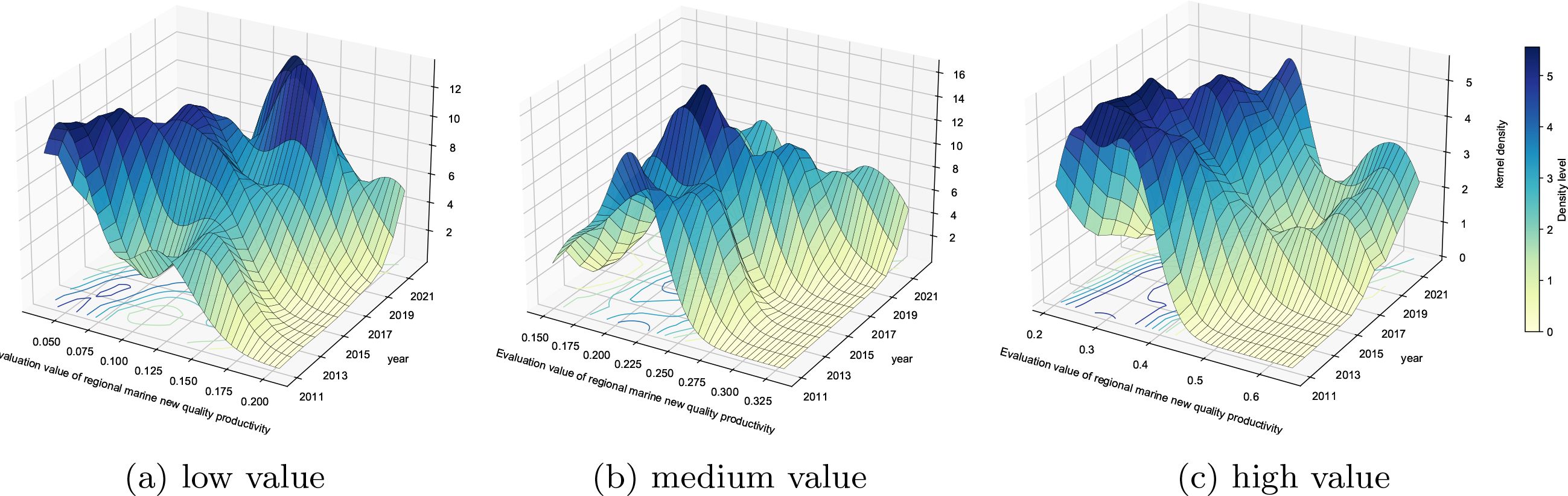

To further analyze the differences among provinces with varying development levels, this section employs the natural breaks method to classify the 11 coastal provinces into three tiers: high, medium, and low development levels. The low-level group includes Hebei, Guangxi, and Hainan; the medium-level group consists of Tianjin, Liaoning, Jiangsu, and Fujian; and the high-level group comprises Shanghai, Zhejiang, Shandong, and Guangdong. Figure 3 illustrates the temporal trends in new quality productivity development across these three regional categories.

5.2 Dynamic evolution of regional marine new quality productivity

Based on previous research, this section, kernel density estimation is employed to depict the temporal evolution of score distributions from 2011 to 2022 (see the three surfaces in Figure 4).

Figure 4. 3D Kernel density plots of regional marine new quality productivity (2011-2022). (a) Low-level group. The surface’s primary peak lies within the 0.15-0.22 range, gradually shifting rightward over time with its right tail extending to approximately 0.25. Overall dispersion remains modest yet predominantly concentrated at low values, reflecting Hebei and Guangxi’s sustained low positions alongside Hainan’s incremental improvement (from approximately 0.198 to 0.259 between 2011 and 2022). (b) Medium-level group. The primary peak gradually shifted from 0.20-0.26 to 0.24-0.30, exhibiting periodic ‘plateau/mild dual-peak’ phenomena: One side corresponds to the decline and fluctuations in Liaoning and Tianjin around 2014-2017 (e.g., Liaoning’s drop after reaching 0.249 in 2014), while the other side reflects Jiangsu’s sustained rise (to 0.323 by 2022). After a slight widening, differentiation within this group tends towards convergence. (c) High-level group. The primary peak shifted markedly to the right and elevated, with distribution transitioning from 0.26-0.30 to 0.31-0.38. A ‘jump’ characteristic emerged around 2017 (exemplified by Shanghai’s rise to 0.350 in 2017), Subsequently, density converged within the high-value zone, indicating stable high-level clustering and a ‘growth pole’ effect (e.g., Shanghai reaching 0.407 by 2021 and Guangdong reaching 0.351 by 2022).

In summary, all three groups of surfaces exhibit a rightward shift, albeit with differing magnitudes and rhythms: the high-level group shows the most pronounced rightward movement and tends towards convergence at elevated levels; the medium-level group shifts steadily to the right, experiencing phased differentiation before returning; the low-level group shifts slowly to the right, remaining predominantly concentrated in low-value areas.

5.3 Spatial evolution of regional marine new quality productivity

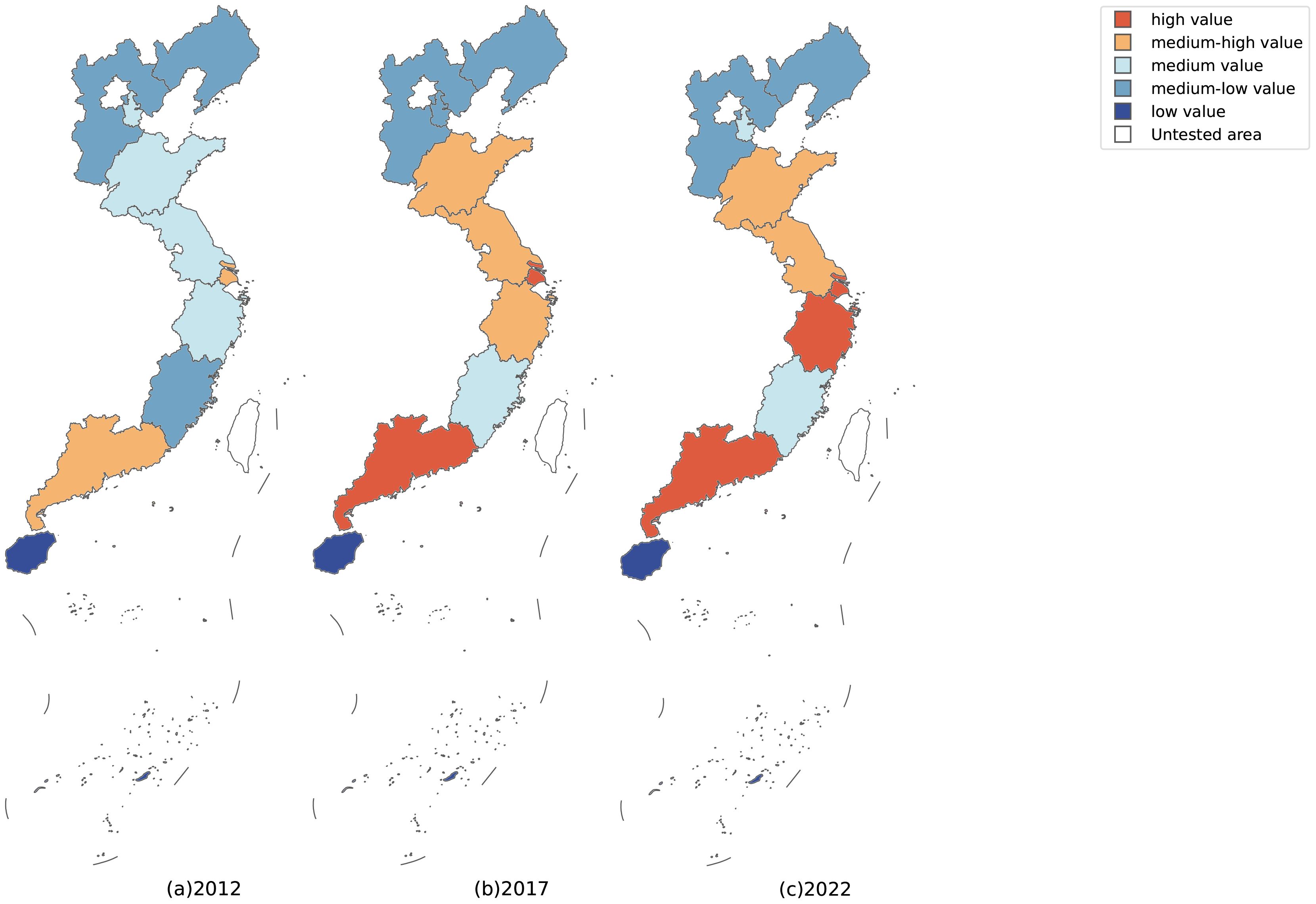

To further elucidate regional disparities, this subsection selected the years 2012, 2017, and 2022 to compare the spatial distribution patterns of marine new-type productive forces across coastal provinces (see Figure 5).

Figure 5. Spatial and temporal variations in the high-quality development of marine new- quality productivity in coastal provinces. This standard map was produced based on the standard map downloaded from the Ministry of Natural Resources’ Standard Graphic Service Map Service website, with the review number GS(2020)4619. (a) 2012: This map shows a concentration of low-to-medium value regions, with Shanghai and Guangdong as emerging high-value areas. (b) 2017: High-value zones expanded to include Jiangsu, Zhejiang, and Shandong, showing a shift from point-like clustering to belt-shaped enhancement. (c) 2022: By 2022, core eastern provinces formed stable high-value clusters, while regions like Hebei and Guangxi remained at lower levels.

In 2012, during the early phase of the Twelfth Five-Year Plan, overall levels remained relatively low, with only a few regions such as Shanghai and Guangdong exhibiting high values, forming nascent growth poles. with most provinces remaining concentrated in the low-to-medium value zone, indicating pronounced regional disparities. By 2017, midway through the 13th Five-Year Plan period, the advancement of China’s innovation-driven strategies and the maritime power strategy saw high-value zones gradually expand to Jiangsu, Zhejiang, Shandong and other areas. The spatial pattern evolved from ‘point-like clustering’ towards ‘belt-shaped enhancement’, moderating regional development gradients. Entering 2022, at the outset of the 14th Five-Year Plan period, the dominant position of core eastern coastal provinces further consolidated, with high-level regions forming relatively stable clusters. Guangdong and Shanghai demonstrated outstanding performance in capital chains and industrial chains, followed closely by Jiangsu, Zhejiang, and Shandong; whereas regions such as Hebei and Guangxi remained at low levels, with regional divergence persisting.

Overall, from 2012 to 2022, the spatial evolution of regional marine new-quality productive forces exhibited a pattern of ‘eastern coastal concentration - central expansion - north-south divergence’. High-level provinces continuously strengthened their role as growth poles under the dual drivers of national strategic support and autonomous innovation. Conversely, low-level provinces still lagged in resource endowment and policy implementation, urgently requiring industrial upgrading and talent aggregation to achieve leapfrog development.

5.4 Analysis of policy driven paths

In the formation of new-quality productive forces in the marine sector, the orientation and focus of government policies serve as key drivers. This section extracts policy attention levels for talent chains, innovation chains, industrial chains, and capital chains from policy documents issued by coastal provincial governments between 2011 and 2022. Employing fsQCA configuration analysis with new-quality productivity metrics as the outcome variable, it reveals the evolutionary patterns of policy-driven pathways across different stages and regions.

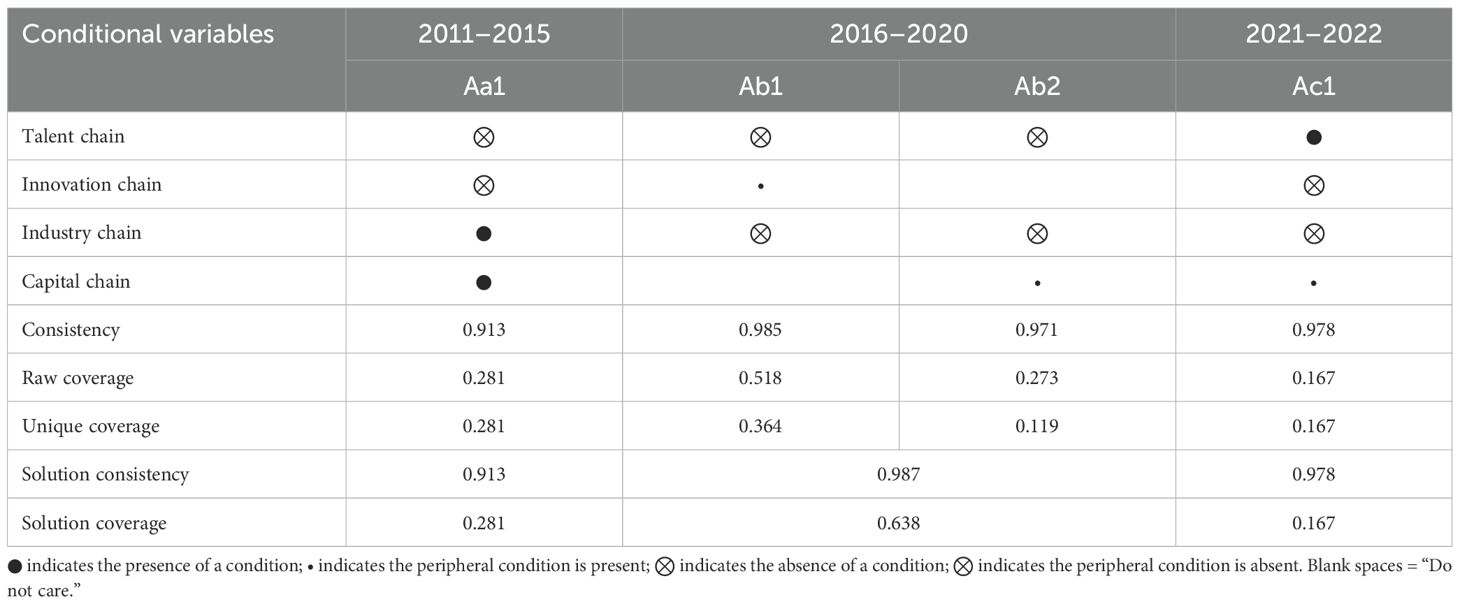

a. Evolution of Policy-Driven Pathways Across Time (Table 4) Table 4 demonstrates marked differences in policy pathways across three developmental phases. During the 12th Five-Year Plan period (2011-2015), policy focus centred on industrial chain development, with government emphasis on marine industry scale expansion and infrastructure construction. However, limited policy investment in talent and innovation chains resulted in new productive forces relying predominantly on traditional factor-driven approaches. During the 13th Five-Year Plan period (2016-2020), policy attention simultaneously increased for both innovation and industrial chains, reflecting the national policy orientation of the ‘Innovation-Driven Development Strategy’ and the ‘Maritime Power Strategy.’ Concurrently, the frequency of talent chain policies rose, with talent cultivation and scientific research support becoming policy priorities. Pathway consistency and coverage significantly improved during this phase. During the initial phase of the 14th Five-Year Plan (2021-2022), policy attention on the capital chain markedly intensified. Fiscal support, investment and financing innovation, and capital factors emerged as key drivers for new-quality productivity, forming a new policy pathway alongside industry and innovation chains. This evolutionary process indicates a gradual shift in policy-driven pathways from ‘industry-oriented’ to ‘innovation-capital synergy,’ reflecting phased adjustments in national macro-strategies.

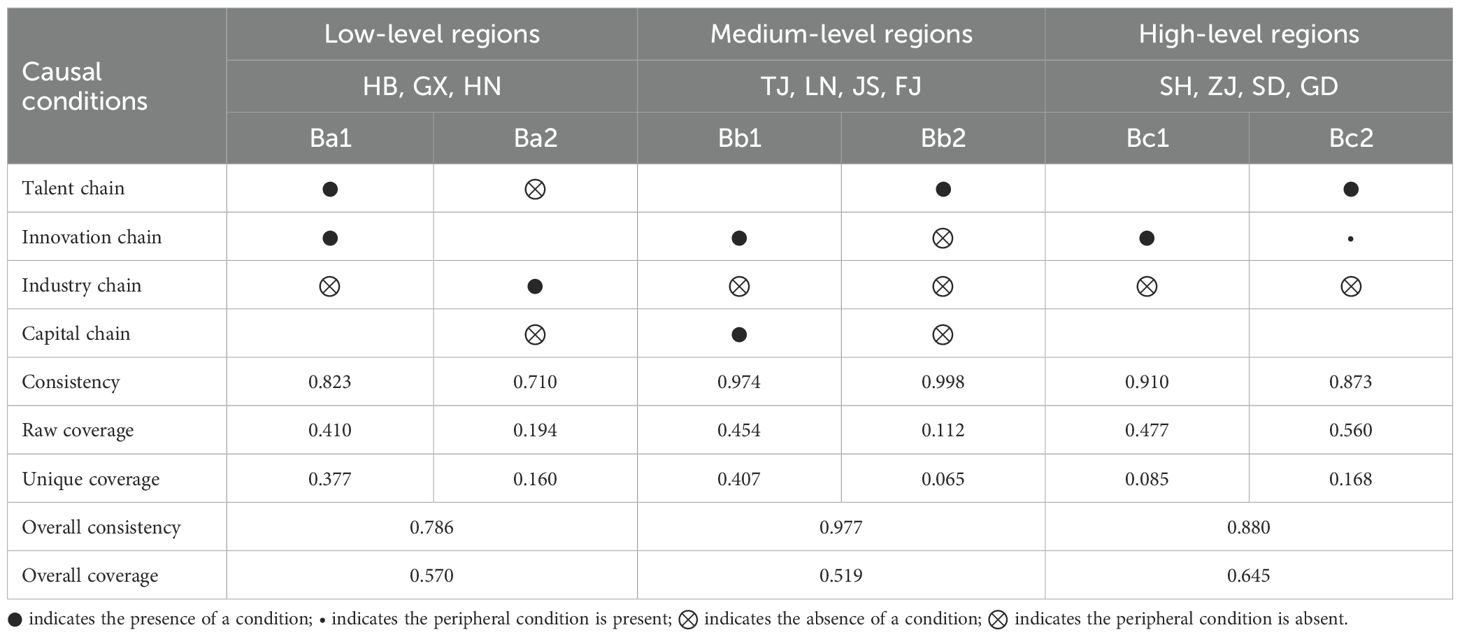

b. Spatial Differentiation in Policy-Driven Pathways Table 5 employs kernel density estimation and natural break analysis to categorise coastal provinces into high, medium, and low tiers, revealing regional disparities in policy-driven pathways. Low-level regions (Hebei, Guangxi, Hainan) generally exhibit insufficient attention to the four chains in policy documents, particularly with limited policy support for the capital chain and industrial chain, resulting in weaker policy-driven effects. Medium-level regions (Tianjin, Liaoning, Jiangsu, Fujian) demonstrate diverse policy combinations: some prioritise industrial chain policy orientation, while others emphasise talent and innovation chains. However, overall capital chain investment remains inadequate, forming diversified yet unbalanced policy pathways. High-level regions (Shanghai, Zhejiang, Shandong, Guangdong) demonstrate significant attention to all four chains, with frequent policies targeting innovation and capital chains complementing industrial and talent chains. This reflects systematic and synergistic policy combinations. Such multi-chain integrated policy-driven models align with these regions’ long-established economic and scientific advantages, propelling them to pioneer high-level new productive forces nationally.

In summary, China’s marine new-quality productive forces exhibit clear phased and spatial differentiation. Policy emphasis has shifted from industrial expansion to innovation and then capital-innovation synergy. Leading regions benefit from integrated multi-chain policy systems, whereas less-developed areas face constraints due to inadequate policy support. Governmental policy design across industry, innovation, talent, and capital chains fundamentally shapes regional development trajectories. Moving forward, policy interventions should prioritize strengthening talent and capital mechanisms in lagging regions to promote balanced and coordinated marine productivity growth.

6 Discussion

This study employs a four-chain integration approach, synthesising entropy analysis, kernel density estimation and fsQCA to elucidate the spatio-temporal evolution and policy-driven mechanisms of marine new-quality productivity in coastal provinces. Overall findings indicate that national strategies and local policy orientations significantly shape inter-regional disparity patterns. Temporally, the evolution of new-type marine productivity closely aligns with national strategic phases. The Twelfth Five-Year Plan prioritized industrial scale and infrastructure, yet limited innovation and talent investment sustained reliance on traditional factors in some areas. The 13th Five-Year Plan emphasized innovation and talent policies, enabling regions like Jiangsu, Zhejiang, and Shandong to transform research advantages into productive gains. Entering the 14th Five-Year Plan, capital chain policies gained prominence, with fiscal and financial innovations facilitating high-level development in Shanghai and Guangdong.

Spatially, provincial performance correlates strongly with resource endowment, policy implementation capacity, and external conditions. High-level regions (Shanghai, Zhejiang, Shandong, Guangdong) exhibit synergistic multi-chain coordination supported by robust port, research, and financial systems. Medium-level regions (Tianjin, Liaoning, Jiangsu, Fujian) display divergent pathways. Liaoning’s development has been particularly affected by macro-industrial policies: environmental regulations under the Blue Sky Protection Campaign and supply-side structural reforms imposed stringent constraints on its traditional heavy chemical and marine equipment industries. Simultaneously, insufficient policy support for industrial transformation and a lack of targeted regional innovation policies hindered its ability to cultivate new growth drivers. Compounded by external challenges such as Sino-US trade friction, these policy limitations resulted in slower growth in new quality productive forces compared to eastern and southern provinces. Lower-level regions (Hebei, Guangxi, Hainan) received insufficient policy support, particularly in capital and industry chains, hindering developmental momentum and remaining dependent on central interventions.

In summary, phased policy adjustments and regional implementation have shaped a landscape of “overall growth—regional divergence—diversified pathways” in marine new productive forces. Future efforts should maintain eastern leadership while enhancing policy coordination and industrial supplementation in central and western coastal regions to achieve balanced development.

7 Conclusion

This study constructs an evaluation framework integrating industry, innovation, talent, and capital chains, and employs the entropy method to measure marine new-quality productivity in 11 coastal provinces from 2011 to 2022. Using kernel density estimation and spatial analysis, it reveals an overall improvement alongside persistent regional disparities. Based on this, fsQCA identifies temporal evolution and spatial variation in policy-driven pathways. Key findings are as follows: First, marine new-quality productivity shows a steady upward trend, but provincial gaps remain, with high-performing regions forming stable growth poles. Second, policy pathways have shifted from “industry-first” to “innovationcapital synergy,” reflecting adjustments in strategic orientation. Third, high-level regions exhibit integrated multi-chain policy models, while medium-to-low-level regions face chain deficiencies and policy constraints, limiting breakthroughs.

Going forward, policies should reinforce coordination among the four chains. High-level regions should enhance their demonstration role, while the state should strengthen fiscal support, talent attraction, and industrial assistance in weaker areas to narrow disparities and support the maritime power strategy and high-quality development.

Data availability statement

Publicly available datasets were analyzed in this study. This data can be found here: https://www.pkulaw.com.

Author contributions

DL: Data curation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. LL: Writing – review & editing, Formal Analysis.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. This paper is one of the phased research achievements of the Key R&D Program (Soft Science) of Shandong Province, China (Project No. 2025RKY0704).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Ahammed S., Rana M. M., Uddin H., Majumder S. C., and Shaha S. (2025). Impact of blue economy factors on the sustainable economic growth of China. Environ. Dev. And Sustainability 27, 12625–12652. doi: 10.1007/s10668-023-04411-6

Bhati M., Goerlandt F., and Pelot R. (2025). Digital twin development towards integration into blue economy: A bibliometric analysis. Ocean Eng. 317. doi: 10.1016/j.oceaneng.2024.119781

Brenton P., Chemutai V., and Pangestu M. (2022). Trade and food security in a climate change-impacted world. Agric. Econ 53, 580–591. doi: 10.1111/agec.12727

Carroll D., Ahola M. P., Carlsson A. M., Skold M., and Harding K. C. (2024). 120-years of ecological monitoring data shows that the risk of overhunting is increased by environmental degradation for an isolated marine mammal population: The baltic grey seal. J. Of Anim. Ecol. 93, 525–539. doi: 10.1111/1365-2656.14065

Chen Z. and Huang W. (2023). Evolutionary game analysis of governmental intervention in the sustainable mechanism of China’s blue finance. Sustainability 15. doi: 10.3390/su15097117

Chen Y., Zhang R., and Miao J. (2023). Unearthing marine ecological efficiency and technology gap of China?s coastal regions: A global meta-frontier super sbm approach. Ecol. Indic. 147. doi: 10.1016/j.ecolind.2023.109994

Curry G. N., Nake S., Koczberski G., Oswald M., Rafflegeau S., Lummani J., et al. (2021). Disruptive innovation in agriculture: Socio-cultural factors in technology adoption in the developing world. J. Of Rural Stud. 88, 422–431. doi: 10.1016/j.jrurstud.2021.07.022

Dominguez-Diaz R., Hurtado S., and Menendez C. (2025). Fiscal stimulus and productivity: simulating the ngeu program with an endogenous growth model. Series-Journal Of Spanish Economic Assoc. 16, 191–228. doi: 10.1007/s13209-025-00304-1

Duan X., Zhao X., Zou M., and Chang Y.-C. (2024). Maritime laws and sustainable development of blue economy: Conference report. Mar. Policy 169. doi: 10.1016/j.marpol.2024.106339

Han Q. and Deng C. (2025). Evaluating the development of China’s modern industrial system. Finance Res. Lett. 74. doi: 10.1016/j.frl.2024.106676

Ji J., Chi Y., and Yin X. (2024). Research on the driving effect of marine economy on the high-quality development of regional economy - evidence from China’s coastal areas. Regional Stud. In Mar. Sci. 74. doi: 10.1016/j.rsma.2024.103550

Jiang G., Fan Q., Zhang Y., Xiao Y., Xie J., and Zhou S. (2025). A tradable carbon credit incentive scheme based on the public-private-partnership. Transportation Res. Part E-Logistics And Transportation Rev. 197. doi: 10.1016/j.tre.2025.104039

Mood A. M. (1950). Introduction to the theory of statistics. 33(3):1065–1076. doi: 10.1214/aoms/1177704472

Onkelinx J., Manolova T. S., and Edelman L. F. (2016). The human factor: Investments in employee human capital, productivity, and sme internationalization. J. Of Int. Manage. 22, 351–364. doi: 10.1016/j.intman.2016.05.002

Seidl A. and Nunes P. A. L. D. (2021). Finance for nature: Bridging the blue-green investment gap to inform the post-2020 global biodiversity framework. Ecosystem Serv. 51. doi: 10.1016/j.ecoser.2021.101351

Sha X., Tang H., and Wang Y. (2025). Research on the measurement and spatio-temporal evolution of marine new-quality productivity in China. Front. In Mar. Sci. 12. doi: 10.3389/fmars.2025.1551481

Verweij S. (2013). Set-theoretic methods for the social sciences: a guide to qualitative comparative analysis. Int. J. Of Soc. Res. Method. 16, 165–166. doi: 10.1080/13645579.2013.762611

Xiu C. and Lis A. M. (2024). Collaborative development model and strategies of multi-energy industry clusters: Multi-indicators analysis affecting the development of coastal energy clusters. Energy 295. doi: 10.1016/j.energy.2024.131036

Xu L., Huang J., Fu S., and Chen J. (2025b). Evaluation of navigation capacity in the northeast arctic passage: evidence from multiple factors. Maritime Policy Manage. 52, 497–513. doi: 10.1080/03088839.2024.2376126

Xu C.-y., Wang Y.-q., Yao D.-l., Qiu S.-y., and Li H. (2025a). Research on the coordination of a marine green fuel supply chain considering a cost-sharing contract and a revenue-sharing contract. Front. In Mar. Sci. 12. doi: 10.3389/fmars.2025.1552136

Xu L., Wu J., Yan R., and Chen J. (2025c). Is international shipping in right direction towards carbon emissions control? Transport Policy 166, 189–201. doi: 10.1016/j.tranpol.2025.03.009

Zhang S., Mao Z., and Zhang Z. (2023). China’s maritime strategy in the new vision. Mar. Policy 155. doi: 10.1016/j.marpol.2023.105769

Zhang X. and Yi G. (2024). Start-ups and innovation ecosystem in China. Sci. Technol. And Soc. 29, 54–74. doi: 10.1177/09717218231215379

Zhou S., Guo Z., Chen J., and Jiang G. (2025a). Large containership stowage planning for maritime logistics: A novel meta-heuristic algorithm to reduce the number of shifts. Advanced Eng. Inf. 64. doi: 10.1016/j.aei.2024.102962

Zhou S., Liu X., Chen J., Zhao M., Wang F., and Wu L. (2025b). Joint optimization of slot and empty container co-allocation for liner alliances with uncertain demand in maritime logistics industry. Transportation Res. Part E-Logistics And Transportation Rev. 204. doi: 10.1016/j.tre.2025.104437

Keywords: marine new-quality productivity, four-chain integration, policy pathways, regional development, fuzzy-set Qualitative Comparative Analysis (fsQCA), modern marine economy, structural weaknesses

Citation: Lu D and Li L (2025) Four-chain integration and policy pathways for marine new type productivity. Front. Mar. Sci. 12:1710678. doi: 10.3389/fmars.2025.1710678

Received: 22 September 2025; Accepted: 17 November 2025; Revised: 11 November 2025;

Published: 03 December 2025.

Edited by:

Lang Xu, Shanghai Maritime University, ChinaReviewed by:

Shaorui Zhou, Sun Yat-sen University, ChinaXu Changyan, Shanghai Maritime University, China

Copyright © 2025 Lu and Li. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Dandan Lu, bGRkNzg5MjFAMTYzLmNvbQ==; Li Li, bGlmZWxvdmVybGlsaUB5ZWFoLm5ldA==

Dandan Lu

Dandan Lu Li Li*

Li Li*