- 1Institute of Marine Sciences - Okeanos, University of the Azores and Instituto do Mar - IMAR, Horta, Portugal

- 2Istituto Zooprofilattico Sperimentale delle Venezie (IZSVe), World Organisation for Animal Health (WOAH) Reference Laboratory for Viral Encephalo-Retinopathy, Padua, Italy

This study reports the first viral nervous necrosis (VNN) outbreak in wild dusky grouper (Epinephelus marginatus) in the North Atlantic, and the first detection of the virus in island grouper (Mycteroperca fusca). Most affected fish displayed typical VNN clinical signs and lesions, and laboratory analyses confirmed the virus as the primary cause of mortality. The majority of the diseased individuals were large adults, underscoring the risk to stock sustainability and conservation of this vulnerable and iconic species. Viral sequences were highly homogeneous (>99% nucleotide similarity), suggesting a single, recent introduction. The outbreak coincided with a severe marine heatwave affecting the Azorean Archipelago in the summer of 2024, during which sea surface temperatures exceeded 25 °C, the optimal range for the RGNNV genotype replication. The absence of fatalities in the eastern islands may be due to several factors, including heterogeneous introduction pathways, oceanographic differences, and lower grouper densities. This event highlights the vulnerability of long-lived, site-attached species to emerging pathogens, particularly under climate-driven stress. Effective management requires coordinated regional responses, ecosystem monitoring and early detection systems to prevent further spread and safeguard wild grouper populations.

Highlights

● First VNN outbreak reported in wild dusky groupers (Epinephelus marginatus) in the North Atlantic.

● Virus also detected for the first time in island grouper (Mycteroperca fusca).

● Viral homogeneity suggests a recent, single introduction into the Azores.

● 2024 marine heatwaves likely triggered disease activation and spread.

● VNN poses a major conservation risk to endangered grouper populations.

Introduction

Marine heatwaves (MHWs), defined as prolonged periods of anomalously high sea surface temperatures, have intensified and become more frequent over the past century, including in the North Atlantic region (Oliver et al., 2018). Largely driven by human-induced global warming, this phenomenon poses severe risks to marine ecosystem structure and functioning (Smith et al., 2023). The North Atlantic, including the waters surrounding the Azores archipelago, has recently experienced exceptionally high sea surface temperatures (SST), setting new records in the duration, extent, and intensity of MHWs (Cheng et al., 2025; Copernicus, 2023; Dong et al., 2025). These extreme events have been associated with short-term atmospheric anomalies, particularly a weakening of northerly winds, which led to a significant reduction in cloud cover and increase in incoming shortwave radiation, which contributed directly to upper ocean warming (Dong et al., 2025).

MHWs significantly impact marine communities at both individual and population levels threatening species viability and population stability (Smith et al., 2023). Mass mortality events during MHWs, frequently associated with disease outbreaks, have been documented in both wild and farmed fish populations (Garrabou et al., 2022; Genin et al., 2020), with drastic consequences for population structure (Kersting et al., 2024). Furthermore, projections indicate that under continued anthropogenic warming, MHWs will become increasingly frequent and extreme, potentially pushing marine organisms and ecosystems to the limits of their resilience (Frölicher et al., 2018).

In the Azores, persistent ocean warming has led to exceptionally high SSTs, with a record daily maximum of 27.3 °C recorded in August 2024, the highest since at least 1941. During that month, positive SST anomalies peaked at +2.7 °C above long-term climatological averages (IPMA, 2024). This North Atlantic volcanic archipelago lies approximately 1,700 km from the nearest continental landmass, making it the most isolated island group in the region. Embedded within a vast open-ocean context, the Azores encompass a diverse array of marine ecosystems—from coastal and pelagic zones to deep-sea and abyssal habitats—supporting high levels of biodiversity and unique phylogeographic patterns (Ávila et al., 2009; Freitas et al., 2019; Santos et al., 1995).

Groupers (family Serranidae, subfamily Epinephelinae) are ecologically and economically important rocky reef demersal fish in the Azores coastal ecosystem. Among them, the dusky grouper (Epinephelus marginatus) is particularly notable for its large size, longevity, and role as a top predator in coastal reef habitats. It is considered a keystone species due to its strong influence on community structure and trophic dynamics (Valls et al., 2012). In the Azores, both dusky and island groupers (Mycteroperca fusca) are primarily caught by hand-line, with bottom longline fishing prohibited for these species since 2012. The dusky grouper, an iconic and highly valued species, is listed as Vulnerable globally and Endangered in Europe according to the IUCN Red List (Pollard et al., 2016), while the island grouper is an endemic species, with its distribution restricted to the Macaronesia Islands in the eastern Atlantic. Albeit limited by data availability, recent assessments suggest that dusky grouper populations in the Azores are fished at sustainable levels (Amorim et al., 2021); however, other studies highlight the species’ high vulnerability in the region (Torres et al., 2022). Its strong site fidelity and slow growth rate make it particularly susceptible to overfishing and environmental stressors. Local conservation initiatives, such as the establishment of no-take zones, have shown promising signs of biomass recovery in resident grouper populations. These positive outcomes are largely attributed to the species’ ecological traits, including small home ranges and strong site fidelity, which enable individuals to remain within the protected area for extended periods (Afonso et al., 2011, 2016, 2018).

Nervous necrosis virus (NNV), which is the causative agent of the disease named viral nervous necrosis (VNN), belong to the Betanodavirus genus within the Nodaviridae family. These positive-sense single-stranded RNA viruses are non-enveloped and exhibit an icosahedral geometry with a diameter of approximately 37 nm. The genome (total of 4.5 kb) is bipartite, consisting of two genetic segments, RNA1 and RNA2, encoding the RNA-dependent RNA polymerase and the viral capsid respectively. The RNA1 segment also gives rise to the subgenomic transcript RNA3 which encodes protein B2, an inhibitor of cell RNA. Betanodaviruses can infect a wide range of teleost fish, with over 170 susceptible species, primarily marine (Bandín and Souto, 2020). Betanodavirus primarily infects neural tissues—namely, the brain, spinal cord, and retina—of the infected fish, resulting in neurological impairments such as loss of coordination and vision. The affected fish commonly exhibit similar signs such as skin lesions, retinal damage (including keratitis and/or panophthalmitis), swim bladder hyper-inflation and are often found floating at the surface and unable to swim properly (Bandín and Souto, 2020). Mortality rates can reach up to 100%, especially in larval and juvenile fish. Survivors can remain persistently infected and transmit the disease to progeny. Betanodaviruses are classified into four major species officially recognized by the International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses (ICTV) namely: Betanodavirus pseudocarangis (SJNNV), Betanodavirus takifugui (TPNNV), Betanodavirus verasperi (BFNNV) and Betanodavirus epinepheli (RGNNV) (Sahul Hameed et al., 2019). Due to the segmented nature of their genome, betanodaviruses can exchange genetic materials and generate reassortant strains. To date, only reassortant viruses originated from the RGNNV and SJNNV viral species are reported, namely RGNNV/SJNNV and SJNNV/RGNNV. These reassortants, presently described only in the Mediterranean basin may exhibit unique pathogenic and epidemiological properties, complicating disease management strategies in aquaculture (Toffolo et al., 2007; Toffan et al., 2017). Nevertheless, the most widespread and virulent Betanodavirus is RGNNV, which infects a broad range of warm-water marine fish species, including groupers (Epinephelus spp.), European sea bass (Dicentrarchus labrax), Asian sea bass (Lates calcarifer), shi drum (Umbrina cirrosa), cobia (Rachycentron canadum), and golden pompano (Trachinotus ovatus). This genotype has been reported across the Mediterranean, Asia, and the Indo-Pacific, where it has caused recurrent epidemics. Over the past two decades, dusky grouper mortalities linked to RGNNV Betanodavirus infections have been documented at multiple sites across the Mediterranean (Haddad-Boubaker et al., 2014; Kara et al., 2014; Kersting et al., 2024; Marino and Azzurro, 2001; Valencia et al., 2019; Vendramin et al., 2013). Water temperature is an important factor that can influence the appearance of clinical signs and mortality of NNV infected fish. The effect of temperature is particularly well known in European sea bass farming and in fact the disease was preliminary identified as “Summer Disease” (Bellance and Gallet de Saint-Aurin, 1998; Fukuda et al., 1996; Vendramin et al., 2013).

The present study aims to identify and characterize the cause of a mass mortality event affecting wild grouper populations in 2024 in the Azores Archipelago—an area where this phenomenon has not been previously documented. By integrating in situ oceanographic data with diagnostic analyses and molecular data from the mortality event, we seek to elucidate the epidemiology of the outbreak and discuss its future implications for the region.

Materials and methods

Study area

The Azores volcanic archipelago, located in the North Atlantic Ocean between approximately 37° and 40° N latitude and 25° and 31° W longitude and approximately 1,700 km from the nearest continental landmass, represents the most remote archipelago in the North Atlantic region (Figure 1). Coastal geomorphology is dominated by narrow island shelves resulting from wave erosion on volcanic slopes, which are marked by steep bathymetric gradients (Quartau et al., 2015). Positioned within a broader open-ocean setting, the Azores supports a wide range of ecosystems—from coastal and pelagic zones to deep-sea and abyssal environments. The region functions as an evolutionary hotspot, particularly for marine coastal species with limited dispersal capacity (Vieira et al., 2019) and is known for its biologically rich seamounts (Carriço et al., 2020; Cascão et al., 2017; Menezes et al., 2006; Morato et al., 2008) and critical habitats for various threatened and endangered fish and megafauna (Afonso et al., 2020).

Figure 1. Map of the Azores Archipelago showing the three island groups: western group (Flores and Corvo), central group (Faial, Pico, São Jorge, Graciosa, and Terceira), and eastern group (São Miguel and Santa Maria). Circles represent the number of grouper morbidity and mortality cases per island, and circle color corresponds to the respective island group. An inset map in the higher right corner indicates the location of the Azores in the North Atlantic Ocean, outlined in red.

From an oceanographic standpoint, the Azores occupy a strategically important position within a convergence zone between western and eastern North Atlantic water masses, which plays a crucial role in shaping regional ocean circulation and enhancing biological productivity (Caldeira and Reis, 2017). The archipelago is influenced by major oceanic currents, notably the Gulf Stream and its offshoot, the Azores Current, both of which are instrumental in modulating local climate conditions and sustaining the region’s high marine biodiversity (Santos et al., 1995). Sea surface temperatures vary seasonally, with average values ranging between 16 °C in winter and 24 °C in summer. The Azores’ complex seafloor topography, steep bathymetric gradients, and regional ocean circulation generates a dynamic frontal zone that enhances nutrient availability and water-column mixing (Caldeira and Reis, 2017). This process underpins elevated biological productivity, shapes distinctive phylogeographic patterns, and sustains the archipelago’s unique marine biodiversity (Ávila et al., 2009). In a recent integrated ecosystem assessment in the Azores (Gomes et al., under revision), the authors reported that the Azorean coastal zone, although covering only 1% of the Exclusive Economic Zone, is highly affected by anthropogenic pressures, including species extraction and the introduction of non-indigenous species.

Temperature data

SST data used in this study were obtained from the Multiparametric Buoy Network, for the period 2005-2025, managed by the Instituto Hidrográfico (IH) of the Portuguese Navy. In the Azores, this monitoring system includes Datawell Directional Waverider buoys deployed offshore from several islands, namely Flores, Graciosa, Faial, Terceira, São Miguel, and Santa Maria. These buoys provide high-frequency, real-time measurements of oceanographic parameters. SST is recorded at the surface using an integrated precision temperature sensor, with data transmitted at 10-minute intervals for the period 2005-2025.

In situ sea temperature data were collected at depth using autonomous temperature loggers (HOBO Water Temp Pro v2, Onset Computer Corporation) deployed at fixed coastal monitoring stations across selected Azorean islands, from 1997 to 2025. Loggers were positioned at depths ranging from 20 to 25 m, depending on local bathymetry and habitat type, and programmed to record water temperature at 30-minute intervals. Devices were retrieved periodically for data download, battery replacement, and sensor calibration checks. Prior to analysis, all-time series underwent quality control to remove outliers and correct for potential sensor drift, ensuring data consistency.

Daily mean temperatures were calculated and analyzed in R to identify MHWs using the Hobday et al. (2016) algorithm. MHW events were defined as periods of at least five consecutive days with SST exceeding the seasonally varying 90th percentile from a long-term climatology. Here, we used climatology derived from our in-situ daily temperature average for the period available (2005 to 2025). According to Hobday et al. (2016), two warm periods are treated as distinct events if they are interrupted by more than two cold days or if the second warm period lasts fewer than five days. MHW intensity was classified following Hobday et al. (2018) into four categories, based on the magnitude relative to the climatological mean and the 90th percentile. The threshold for MHW detection is defined as the local difference between the climatological mean and the 90th percentile, and intensity categories are expressed as multiples of this value: moderate (Category I, 1×), strong (Category II, 2×), severe (Category III, 3×), and extreme (Category IV, >4×).

Fish mortality

Starting from September 2024, fishermen and other marine users observed many dead and moribund groupers during routine coastal activities, subsequently reporting these observations to our research team or regional authorities. Whenever possible, observers recorded key data for each individual encountered, including the date, location, health status (moribund or deceased), total length and included relevant photos and/or videos. A total of 162 dead fish were documented, morphometrical data were collected from 69 of them and necropsy was performed on 40 carcasses.

Necropsy

Due to the large number and size of the specimens collected, all individuals were frozen prior to necropsy. Morphometric measures were recorded for each sample. A standard necropsy was conducted to assess external lesions, the presence of macroscopic external parasites, and internal pathological changes. Sex was determined through gonadal inspection, and gonads were collected for subsequent analyses to evaluate reproductive condition. Organs were collected based on the preservation status of each carcass, aiming to capture the maximum variability across sizes, collection sites, and dates.

Eye, optic nerve, brain, heart, kidney, liver, spleen, and gonads were collected in 10% neutral buffered formalin for histological analysis. Twenty-four (24) samples of brain, eye, and optic nerve were preserved in RNAlater and sent to the reference laboratory for molecular analyses, and a subset of brain samples was stored frozen for virus isolation.

Viral isolation

A few samples of frozen brain homogenates were thawed and prepared by grinding with sterile quartz sand and suspended in a 1:3 w/v ratio with cell culture medium (Eagle Minimum Essential Medium, Sigma). Homogenates were centrifuged at 4,000 x g for two minutes. Then, 180 μl of each supernatant added with 20 μl (10%) of mixed antibiotic/antimycotic solution containing 10.000 IU/ml penicillin G, 10 mg/ml streptomycin sulfate, 25 µg/ml amphotericin B (Sigma) and 0.4% of 50 mg/ml kanamycin solution (Sigma) were left in incubation with antibiotics overnight at +4 °C. After incubation, samples were inoculated on 24h-old SSN-1 monolayers seeded in 24 well plates at two different dilutions (1:10-1:100) (Frerichs et al., 1996). Plates were incubated for 10 days at 25 °C. Daily observation for appearance of cytopathic effect (CPE) was performed. Negative samples were subjected to a second passage of 10 days performed as described before on fresh cell monolayer.

Histopathology and immunohistochemistry

Grouper samples were collected from defrost specimens and fixed in 10% neutral buffered formalin. Samples were then dehydrated through a graded ethanol–xylene series and embedded in paraffin. Sections of 3 μm were first deparaffinized, rehydrated and then either stained with Mayer’s haematoxylin–eosin (HandE) for histopathological examination or subjected to immunohistochemical analyses (IHC) following (Vázquez-Salgado et al., 2020). IHC was performed automatically from dewaxing to counter-staining using the Discovery-Ultra instrument (Ventana Medical Systems Inc., Tucson, USA) on tissue sections collected on poly-l-lysine-coated slide (HistoBond®+; Marienfeld Superior). The IHC reaction was performed with a rabbit polyclonal serum against Betanodavirus RGNNV genotype produced in-house (PAb283) (Panzarin et al., 2016), at the dilution of 1:5,000. Slides were then counterstained with Mayer’s haematoxylin for 8 min, air-dried, dipped in xylene, and mounted in Eukitt medium (Kaltek, Saonara, Italy). The slides were observed with a Nikon H550L microscope at 40–1000×. Bright red IHC staining highlighted the presence of Betanodavirus antigens. Digital images were captured using a Nikon DS-Ri2 integrated camera and NIS Elements 5.30 software (Nikon, Japan).

Qualitative real-time RT-PCR, genotyping and phylogenetic analysis

Specimens for molecular analysis were sent to the laboratory stored in RNA later™. Samples homogenates were obtained as for virus isolation and then clarified by centrifugation at 8.000 x g for two minutes. For each sample, nucleic acids were purified starting from 250 μl of harvested supernatant added with 300 μl of ATL lysis buffer (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) from the QIAsymphony® DSP Virus/Pathogen Midi Kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) which was used in combination with the automated system QIAsymphony SP (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany), according to the manufacturer’s instruction (Qiagen). The remaining supernatants were immediately stored at -80 °C for further analysis.

Each sample was then tested for the presence of Betanodavirus using a qualitative real time RT-PCR (rRT-PCR) targeting the RNA1 segment of all known Betanodavirus species (Baud et al., 2015). According to the laboratory internal validation, samples with cycle threshold (Ct) < 34.00 were considered positive, doubtful if Ct values ranged from 34.00 and 36.00 and negative if Ct values were > 36.00 or showing no amplification.

The genetic characterization of NNV positive samples was obtained by performing a reverse transcription followed by PCR amplifications targeting the genetic segments RNA1 (RNA-dependent RNA polymerase) and RNA2 (capsid protein). Primers employed for the amplification of RNA1 and RNA2 partial sequences had been previously published by Toffolo et al. (2007) and Bovo et al. (2011). For this purpose, the OneStep RT-PCR kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) was used applying the following cycling conditions: 50 °C for 30 min, 95 °C for 15 min and 40 cycles of 40 s denaturation at 94 °C, 40 s annealing at 55 °C and 70 s elongation at 72 °C; the reaction was terminated with 10 min elongation at 72 °C. PCR products were analyzed for purity and size by capillary electrophoresis on a QIAxcel Advanced System with QIAxcel DNA High Resolution kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany). Amplicons were then purified with ExoSAP-IT Express (Applied Biosystems by Thermo Fisher Scientific, Baltics, UAB, Lithuania) and sequenced bidirectionally using the BrilliantDye™ Terminator (v3.1) Cycle Sequencing kit (NimaGen, Nijmegen, The Netherlands). Sequencing reaction products were cleaned up using the BigDye XTerminator™ Purification Kit (Applied Biosystems by Thermo Fisher Scientific, Bedford, MA, USA) and analyzed on a 16-capillary ABI PRISM 3130xl Genetic Analyzer (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA).

Sequencing data were assembled and edited using the SeqScape software v3.0 (Applied Biosystems). Partial RNA1 and RNA2 consensus sequences were aligned and compared to a selection of reference nucleotide sequences retrieved from GenBank using the MEGA 7.0 package (Kumar et al., 2016). The selection of reference sequences for the dataset construction was performed according to i) the BLAST results obtained for each gene of each sample and ii) a selection of nodavirus derived from recent groupers die-off in the Mediterranean Sea. For both segments, phylogenetic relationships among isolates were inferred using the maximum likelihood (ML) method available in the IQ-Tree software v1.6.9 (Nguyen et al., 2015). The best fitting model of nucleotide substitution was determined with ModelFinder (Kalyaanamoorthy et al., 2017). One thousand bootstrap replicates were performed to assess the robustness of individual nodes of the phylogeny, and only values ≥70% were considered significant. Phylogenetic trees were visualized with the FigTree v1.4 software (http://tree.bio.ed.ac.uk/software/figtree/, accessed on 02 January 2025.

Pairwise nucleotide and amino acid similarities (p-distance method) among the Azorean NNV sequences, and between this latter group and RGNNVs detected in the Mediterranean Sea groupers, were determined with the MEGA6 software.

Results

Grouper mortality event

Between August 2024 and January 2025, a total of 161 dusky groupers and 1 island grouper exhibiting signs of morbidity or found deceased were reported along the coastal waters of seven islands in the Azores Archipelago. Of these, approximately 65% were recorded in the central group of islands—primarily around Faial and Graciosa—while the remaining 35% were reported in the western group, around Flores and Corvo. One individual was reported in the eastern group (São Miguel); however, no photographic evidence or biological samples were available to confirm the latter case (Figure 1) that should then be only considered in case of future outbreaks in the area.

Of the 162 animals reported, 70 individuals (42.9%) were observed alive at the water’s surface, 57 (35.0%) were discovered dead and stranded in coastal areas, 14 (8.6%) were floating dead at the surface, and 3 (1.8%) were found alive on the seafloor. The remaining cases were unclassified due to lack of detailed reporting. Live individuals observed floating at the surface consistently exhibited exophthalmos, neurological and behavioral abnormalities, including circular swimming patterns, loss of equilibrium, lethargy, and an inability to maintain normal body orientation.

The first isolated case was reported on 19 August 2024 in Faial Island; however, the onset of multiple cases began in early September in the western group of islands. Approximately two weeks later, consistent reports started emerging from the central group. A pronounced peak in incidence was observed between 7 September and 10 October, during which nearly 90% of all cases were documented. While the majority occurred within this five-week window, sporadic cases continued into November, with the final affected individual reported in January 2025. The M. fusca specimen was recorded in early October in the central group (Faial Island), measuring 66.5 cm in total length. The individual was observed alive, swimming erratically at the surface, and displaying an inflated abdomen and opaque eyes.

Among the 69 dusky grouper individuals for which total length was recorded, the mean body length was 74.1 ± 20.3 cm (mean ± standard deviation), with sizes ranging from 20 cm to 110 cm (Figure 2 and Table 1). There was a clear prevalence of adult individuals, with approximately 80% of the measured groupers exceeding L50 for this species (L50 = 57,1cm (Amorim et al., 2021)). Sex determination was based on macroscopic analysis of the gonads, and all the necropsied individuals were identified as female. However, some carcasses were too degraded to allow for sex determination. Female gonads were identified based on their shape, color, texture, and visible signs of maturity. Further histological analyses are required to confirm these observations and accurately determine the gonadal maturity stages.

Figure 2. Size–frequency distribution of moribund or deceased Epinephelus marginatus individuals. The dashed red line marks the L50, the length at which 50% of the population reaches sexual maturity, estimated at 57.1 cm (Amorim et al., 2021).

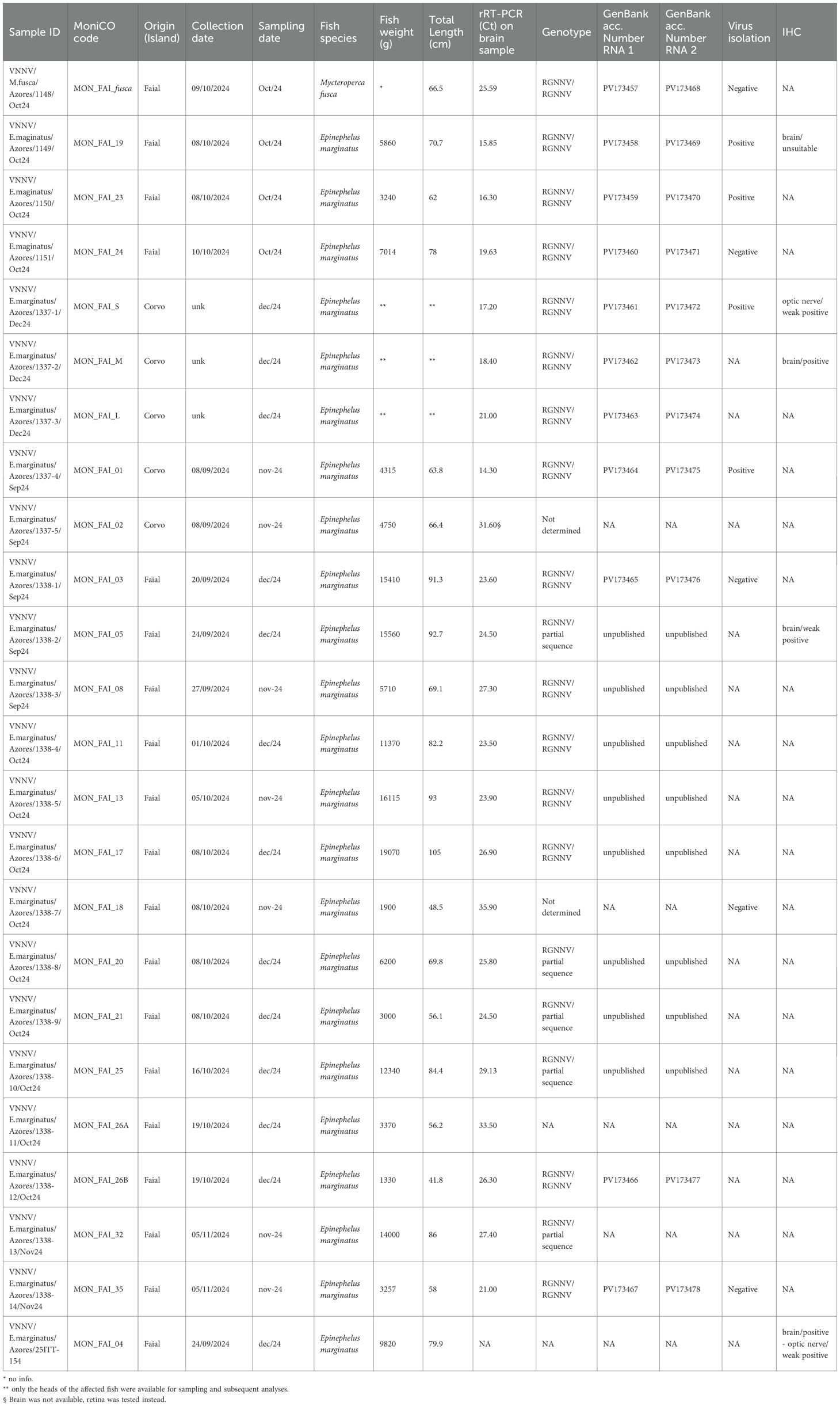

Table 1. Summary of morphometrical data and results of laboratory tests. NA: Not available/Not performed. .

Temperature data

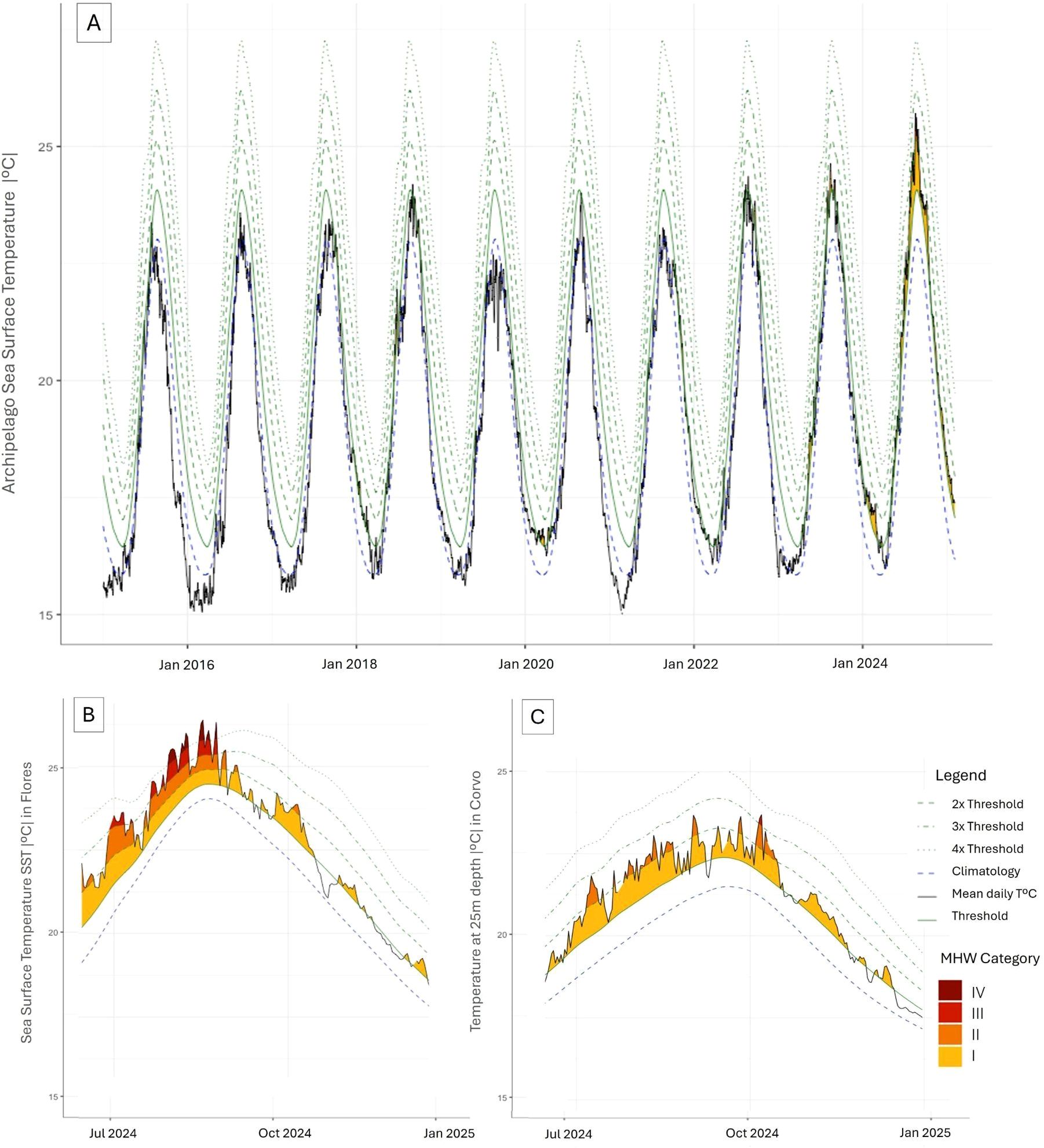

In the Azores archipelago, several MHWs were observed between 2005 and 2025, with a marked increase in frequency in recent years (see Figure 3A and Supplementary Material 1 for details).The years 2023 and 2024 recorded the highest intensity and frequency of events. In 2024 alone, five MHWs took place in the region, two of which lasting over 100 days. The most intense was recorded between August 12 and October 20, lasting 131 days and reaching a cumulative intensity of 2.76 °C. This event was classified as strong (Category II) (see Figure 3A and Supplementary Material 2 for details).On Flores Island, located in the western group of the archipelago, a prolonged MHW event was recorded in 2024, lasting 73 days (from 14 June to 25 August) and reaching a maximum cumulative intensity of 2.97 °C (Figure 3B).Based on this analysis, this represents the only extreme event (Category IV) documented in the Azores archipelago within the 2005–2025 dataset. At a depth of 25 meters, data loggers on the island of Corvo recorded seven MHW events in 2024 (Figure 3C), four of which were classified as strong and one as severe (Category III), the first time such an event was recorded at this depth. This event lasted 28 days, from September 19 to October 16, with a cumulative intensity of 2.52 °C.

Figure 3. (A) SST trends in the Azores from January 2015 to 2025, based on buoy measurements. Long-term climatology (2005–2025) was derived and averaged from all buoys across the archipelago. For resolution purposes, only the last ten years are shown in Panel (A) (see full dataset in Supplementary Material 1). Marine heatwave (MHW) events were identified and characterized following Hobday et al. (2016).A strong MHW (Category II) occurred in September 2024. (B) SST record from Flores Island buoy, showing an extreme MHW in August 2024, relative to the long-term climatology (2006–2025). (C) Daily temperature at 25 m depth in Corvo Island, showing MHW events in 2024 (long-term climatology period 1997–2025). The black line represents the daily mean temperature, the blue dashed line the climatological mean, and the green line the 90th percentile threshold. Green dashed lines represent multiples of the 90th percentile difference (2× twice, 3× three times, 4× four times) from the mean climatology value. Shaded areas highlight MHW events, with color intensity indicating event severity.

Necropsy

Post-mortem examinations were conducted on a subset of 40 individuals. External lesions were consistent among necropsied specimens and were also frequently reported in field observations of non-necropsied cases. The most observed external abnormalities included skin and fin erosion, exophthalmos, corneal opacity and abdominal distension (Figure 4). Internal examinations revealed no pathognomonic lesions, but several notable findings were recurrent. These included hyperinflation of the swim bladder, cerebral congestion and absence of ingesta throughout the stomach and intestines. Parasite cysts were occasionally detected in various tissues—primarily in the gills—but no consistent or significant parasitic burden was identified.

Figure 4. Photographs illustrating typical findings in wild groupers during the 2024 outbreak: (A) live individual exhibiting erratic swimming behavior; (B) Epinephelus marginatus stranded on the beach with hyperinflated abdomen and opaque eyes; (C) adult Mycteroperca fusca with opaque eyes; (D) swim bladder showing a perforation; (E) brain collection for virus identification and isolation, with signs of inflammation.

Qualitative real-time RT-PCR, viral isolation, IHC, genotyping and phylogenetic analysis

All tested specimens (n°24: 23 brains and 1 retina) resulted positive by rRT-PCR for NNV RNA detection. NNV sequences were obtained from 19 samples selected according to geographical origin, species affected and sample quantity. RNA1 and RNA2 partial genes sequences were obtained for all of them. Due to high degree of identity, 11 sequences have been deposited to GenBank under the accession number PV173457 - PV173478 and used for the phylogenetic analysis.

Five out of 9 samples tested also positive by virus isolation on cell culture showing typical cytopathic effects on SNN-1 cells. Moreover, while testing samples by IHC n° 3 samples out of 4 presented immunostaining (weak or strong, depending on the tested organs) (Figure 5). One additional sample was stored only in formalin and therefore was tested only by IHC, and this sample tested clearly positive as well (Table 1). Cumulatively 24 specimens of grouper (23 E. marginatus + 1 M. fusca), corresponding to the 100% of tested fish out of 162 reported, tested positive for NNV by different laboratory methods.

Figure 5. Immunohistochemistry of the encephalon of affected Epinephelus marginatus. Bright red immunostaining (arrows) indicates the presence of RGNNV antigens. (A) encephalic parenchyma of E. marginatus from Corvo island, vacuolation is not clearly discernible due to freezing artifacts; (B) encephalic parenchyma of E. marginatus from Faial Island.

Histology performed on the internal organs (liver, heart, kidney, spleen) from n° 8 of these specimens, beside freezing alterations, did not reveal lesions indicative of any other infectious agent or parasitic disease.

Maximum likelihood phylogenetic analysis based on a selection of the longest nucleotide sequences for both RNA1 and RNA2 clearly grouped all sequences in a single strongly supported cluster within the RGNNV genotype (Figure 6). The Azorean viral isolates were highly homogeneous, presenting a nucleotide (nt) similarity ranging from 99.24 to 100% according to RNA1 sequence and from 99.68 to 100% at the amino acidic (aa) level. RNA2 sequence presented a similarity ranging from 99.29 - 100% at the nt level and 99.47-100% at the aa level. Correspondingly, the Azorean viruses, when compared with other RGNNV detected in grouper mortality events occurred in the Mediterranean Sea in previous years, showed a higher divergence with nt similarity ranging from 96.55 - 97% for RNA1 and 93.63 - 94.1% for RNA 2, and an aa similarity ranging from 99.68 - 100% (RNA1) to 94 - 94.15% (RNA2).

Figure 6. ML phylogenetic trees based on partial (A) RNA1 and (B) RNA2 sequences. The Azorean betanodavirus strains isolated from wild diseased Epinephelus marginatus and Mycteroperca fusca are highlighted in red. Betanodavirus genotype subdivision is displayed by branch labelling. Bootstrap values are shown at nodes (only values ≥70% are reported), while branch lengths are scaled according to the number of nucleotide substitutions per site. The scale bars are reported.

Discussion

This study reports, for the first time, a VNN outbreak in wild dusky groupers in the Atlantic Ocean, with potential links to recent MHWs. Notably, it is the first time NNV is detected in island groupers.

In the Mediterranean region, Betanodavirus has long been present and is recognized as the causative agent of recurrent mortality outbreaks among different grouper species. Historical data indicate that wild-grouper mortality events due to Betanodavirus date back to at least the early 1990s, with recurrent outbreaks documented in various European and North African countries (Boukedjouta et al., 2020; Haddad-Boubaker et al., 2014; Kara et al., 2014; Kersting et al., 2024; Marino and Azzurro, 2001; Valencia et al., 2019; Vendramin et al., 2013).

Typical VNN lesions were observed in the majority of fish observed and collected in the Azorean archipelago, allowing for a presumptive diagnosis, which was subsequently confirmed through laboratory analyses. Laboratory findings revealed no other obvious causes of mortality in the affected individuals. Combined with the 100% prevalence of VNN in the tested samples, these results indicate that the viral infection was the primary cause of fish mortality at least for the dusky grouper. With reference to island grouper, more studies are needed in order to investigate the susceptibility of this species to NNV infection. The island grouper (M.fusca) is an endemic serranid species native to the Macaronesian archipelagos. It is by far the least abundant of the three coastal Serraninae species occurring in the Azores, with an average frequency of occurrence of 7.5% in standardized underwater visual censuses across the archipelago, compared with 32.4% and 80.1% for Epinephelus marginatus and Serranus atricauda, respectively (Afonso et al., 2018). The Azores represent the northernmost limit of this thermophilic species, which likely explains its naturally low abundance in the region compared with other Macaronesian archipelagos, such as the Canary Islands.

Notably, as frequently reported in previous studies, only large adult fish were observed, a pattern consistent with other VNN-related mortality in the Mediterranean Sea (Boukedjouta et al., 2020; Kara et al., 2014; Vendramin et al., 2013). Smaller individuals are usually more difficult to detect and may be easily preyed on by local predators (sharks, cetaceans, seagulls, etc.). Consequently, it is not currently known whether this pattern reflects a higher susceptibility of the large specimen to the disease or simply their easier detection. As a protogynous, long-lived, and slow-growing species with limited dispersal, maintaining larger individuals is essential for reproduction and overall stock sustainability. The loss of a substantial proportion of mature fish poses significant risks, including slow population recovery, which may be further exacerbated by the archipelago’s remoteness and widely dispersed fishing grounds.

Comparison of viral sequences from individual fish revealed high uniformity (always >99% of nucleotidic similarity) indicating a single virus strain being introduced and transmitted within the population. This high sequence uniformity is consistent with observations from other VNN outbreaks, such as those in hatcheries, where viral sequences were mostly identical (Knibb et al., 2017). Both the observed high sequence uniformity, together with the large distances between the Azorean islands (>250 Km from Western and Central islands) further accentuated by the deep-water columns separating them, suggests a single, likely recent introduction of VNN into the region, rather than long-term endemic presence. Indeed, if the virus had been circulating previously among different fish populations across the islands, a higher degree of genetic variability would be expected. Therefore, the absence of relevant genetic variation among viruses from different islands supports a relatively short history of local viral circulation.

Regional geographical clustering of RGNNV strains has been reported by multiple authors (He and Teng, 2015; Knibb et al., 2017; Lovy et al., 2025; Panzarin et al., 2012) and is thought to result from three main mechanisms (He and Teng, 2015): (i) parallel or convergent evolution, where independent viral populations acquire similar genetic traits in response to comparable environmental pressures; (ii) transfer via wild carriers; and (iii) mechanical spread of the virus, including the commerce of infected stocks in aquaculture. The absence of significant aquaculture activities, combined with the remoteness of the archipelago and the surrounding deep waters, makes rapid spread via imported or migratory fish or passive water transport unlikely. Nevertheless, highly mobile species visiting the archipelago—such as blue marlins (Makaira nigricans) could act as natural vectors (Cook et al., 2024). Additionally, the high and continually increasing number of susceptible and carrier fish species further amplifies the potential for viral dispersal (Bandín and Souto, 2020). However, the low observed viral homogeneity points towards the fact that the virus entered the Azores through a mechanical transmission or discrete introduction event, most likely associated with human-mediated vectors.

Ballast water is one of the most important global vectors for the transfer and spread of marine organisms across ocean basins (Bailey, 2015; Takahashi et al., 2008), including many pathogens (Zhou et al., 2023). The European Environment Agency reports that 346 ballast-related non-indigenous species were introduced into European seas between 1949 and 2021 (European Environment Agency, 2021), highlighting its role as a major pathway for species introductions. Kim et al., 2016 provided direct evidence that ballast water harbors a high diversity of viruses and can disperse them across global marine environments. The Azores archipelago occupies a strategic position at the crossroads of the central Atlantic, shaping transatlantic and transboundary maritime operations as part of major routes connecting North America with Northern Europe and the Mediterranean. In recent years, vessel activity across the region has intensified, with notable increases in both freight and passenger traffic. As previously mentioned, VNN is endemic to the Mediterranean Sea, making it plausible that ballast water from European vessels could also transport Betanodavirus. Notably, the viral sequences of the Azorean isolates clustered, according to the phylogenetic tree, with other viral sequences (designated MmNNV in the tree) detected during a similar grouper mortality event in the Columbretes Islands in 2023 (Kersting et al., 2024). Nevertheless, it should be emphasized that a potential origin of the virus from the American continent cannot be ruled out. Indeed, despite the few reports available, VNN has been reported both in North and Central America (where it was detected for the very first time) and its prevalence is most probably underestimated (Bellance and Gallet de Saint-Aurin, 1998; Curtis et al., 2001; Lovy et al., 2025). However, based on current information, the mechanisms of viral introduction and spread in the Azores remain unclear.

A plausible hypothesis for the arrival and spread of VNN in the Azores is that the virus was introduced into the region via ballast water, and may have persisted in a dormant or subclinical state, constrained by local SSTs generally remaining below 24 °C. The strong correlation between virulence and water temperature is supported by both in vitro and in vivo studies (Hata et al., 2010; Iwamoto et al., 1999; Panzarin et al., 2014; Toffan et al., 2016), which show that the RGNNV genotype replicates most efficiently at warmer temperatures (25–30 °C). Water temperature is therefore a key factor influencing the course of betanodavirus infections, affecting both viral replication efficiency and disease severity (Fukuda et al., 1996; Toffan et al., 2016; Vendramin et al., 2013). In the summer of 2024, during an extended and severe MHW in the Azores, SSTs surpassed this thermal threshold for prolonged periods. Most notably, in Flores Island where most of the cases were reported initially, there was an extreme MHW (Category IV) with a highest cumulative intensity reaching 3 °C in August. Importantly, MHW were not limited to surface waters but were also recorded at 25 m depth, where temperatures exceeded historical averages, thereby increasing the exposure of demersal species such as groupers. These anomalously high temperatures likely reactivated the virus, facilitating replication, invasion of nervous tissues and subsequent emergence of clinical disease. Elevated temperatures can impair fish immune function by suppressing immune responses, while also affecting multiple physiological processes, including metabolism, thereby exacerbating susceptibility to disease (Scharsack and Franke, 2022). The temporal coincidence between the unprecedented heatwave and the mortality event therefore supports the hypothesis that climate-driven thermal anomalies acted as the trigger for VNN activation and spread within closely connected grouper populations.

The dusky grouper exhibits a complex life-history strategy as a protogynous hermaphrodite: individuals first mature as females and may later transition to males. Reported sizes at sexual transition vary widely, from 51.5 cm TL in Brazil to 68.5 cm TL in Italy (Condini et al., 2018). Spawning occurs from late spring to late summer, with aggregations documented in the Mediterranean (Hereu et al., 2006), southeastern Africa (Fennessy, 2006), and the southwestern Atlantic (Andrade et al., 2003; Condini et al., 2015; Gerhardinger et al., 2006). In our study, among the 40 necropsies performed, only females were observed. Furthermore, for all animals for which we could obtain size estimates, the vast majority were reproductively active adults, with 80% exceeding the estimated L50. These findings may reflect aggregation behavior of large individuals, which could have facilitated virus spread within these groupings. Spawning aggregations are generally characterized by large individuals, with males establishing territories in deeper waters, typically below the thermocline, while females remain in shallower depths (Louisy and Culioli, 1999). The loss of mature fish, particularly larger and older females, is especially concerning, as these individuals contribute disproportionately to reproductive output by producing more numerous and higher-quality offspring (Hixon et al., 2014). Mortality in this size class may therefore have significant long-term consequences for recruitment and the sustainability of local populations.

The absence of reported cases in the most eastern islands such as Terceira, São Miguel and Santa Maria may reflect a combination of ecological, environmental, and epidemiological factors. First, grouper populations in Terceira and São Miguel are typically less dense, likely due to increased historical coastal exploitation. The reduced frequency of host–host encounters may limit viral transmission and decrease the likelihood of an outbreak. Kersting et al. (2024) and Valencia et al. (2019) reported similar severe RGNNV disease outbreaks in areas with dense dusky grouper populations, namely marine reserves in the Mediterranean. Second, local differences in oceanographic conditions may have contributed, as thermal anomalies associated with the 2024 MHW were not spatially uniform, and variations in sea surface temperature could have influenced whether viral replication surpassed the activation threshold required for disease expression. Finally, the introduction of the virus may have followed specific maritime routes or mechanical vectors that favored initial entry into certain islands over others. Environmental factors, including sea temperature, host density, and physiological stress, have been suggested to influence the occurrence and severity of VNN outbreaks (Munday et al., 2002) and have likely determined the spatially heterogeneous impact of VNN across the Azorean archipelago.

Conclusion and way forward

This study documents the first VNN-related mortality event in wild groupers in the North Atlantic, impacting both dusky groupers and possibly island groupers, with large females disproportionately affected. The findings underscore the urgent need to monitor coastal grouper populations and their environments, particularly in areas of high density, to detect early signs of mortality and assess population health.

Given the substantial impacts of MHWs on ecosystems, developing effective early warning systems would be invaluable for managers across marine sectors, providing advance information on the likelihood, intensity, duration, and frequency of these events (Spillman et al., 2021). Adaptive measures such as temporary fishery closures, catch limits, or the establishment of climate-refugia marine protected areas may help affected stocks recover while promoting the sustainable use of marine resources.

The implementation of international guidelines and regulations on ballast water management is also critical to reduce the risk of introducing pathogens, including viruses, between marine regions.

The 2024 VNN outbreak in the Azores highlights the vulnerability of wild dusky and potentially island groupers to emerging pathogens, representing an additional threat to these already endangered species. The removal, proper storage, and burial of carcasses represent effective measures to reduce the risk of disease transmission among fish populations. In the present study, affected individuals were collected, frozen, and subsequently buried to minimize the potential spread of viral particles. Similar actions have been recommended in other outbreak events, such as that reported by Kersting et al. (2024). Effective management requires coordinated response protocols, including rapid and standardized virus identification, diagnostics, and the prompt removal of dead or moribund individuals to limit further transmission. Close collaboration between regional authorities and competent institutions is also essential to ensure timely information exchange, harmonized response strategies, and access to technical expertise. The long-term impacts on population abundance and biomass remain to be determined and are currently the focus of ongoing monitoring and evaluation.

Data availability statement

The datasets presented in this study can be found in online repositories. The names of the repository/repositories and accession number(s) can be found below: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/genbank/, Accession numbers from PV173457 to PV173478.

Ethics statement

Ethical approval was not required for the study involving animals in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements.

Author contributions

IG: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Supervision, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. AN-P: Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Resources, Writing – review & editing. MA: Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Software, Writing – review & editing. TP: Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Software, Writing – review & editing. JR: Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Writing – review & editing. LS: Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Writing – review & editing. PT: Data curation, Investigation, Methodology, Writing – review & editing. AM: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Resources, Software, Writing – review & editing. PA: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Supervision, Writing – review & editing. AT: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Resources, Software, Supervision, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declared that financial support was received for this work and/or its publication. This work was supported by the Azorean Regional Government under the MoniCO Program – Azores Coastal Resources and Environmental Monitoring Program (SRMCT/DRP) and the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under Grant Agreement No 862428 (MISSION ATLANTIC). Further funding was granted by national funds through the FCT – Foundation for Science and Technology, I.P., under the project UIDB/05634/2025 and UIDP/05634/2025. IG was supported by FCT (Fundação para a Ciência e Tecnologia) individual contract (CEECINST/00024/2021) and AN-P, JR, LS, and PA were supported by the MoniCO Program – Azores Coastal Resources and Environmental Monitoring Program (SRMCT/DRP).

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Inês Duarte, Mariana Cruz, Amparo Ferragud, Margarida Duran, Peter West, Leonor Mendonça, Jorge Fontes (OKEANOS Institute of Marine Sciences) and Célia Mesquita (Regional Secretariat for Agriculture and Food) for their valuable assistance with individual removal and necropsies. Soraia Estacio (Regional Secretariat of the Sea and Fisheries), Lara Aguiar (Corvo Agricultural Development Service), Alice Ramos (Flores Agricultural Development Service) for information about epidemiology and support in logistics. We also thank the Regional Directorate of Fisheries for providing a freezer container to store the carcasses and the Regional Directorate for the Environment and Climate Action for facilitating their proper burial. We thank Nuno Brito Mano for his assistance with the graphical design of the graphical abstract. Alessandra Buratin, IZSVe, is kindly acknowledged for technical assistance.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared that this work was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declared that generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript. During manuscript preparation, we used ChatGPT (OpenAI, March 2025 version) as a tool for editing text and improving clarity. All content was reviewed and approved by the authors. The authors take full responsibility for the accuracy, reliability, and integrity of the final manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fmars.2025.1712250/full#supplementary-material

References

Afonso P., Abecasis D., Santos R. S., and Fontes J. (2016). Contrasting movements and residency of two serranids in a small Macaronesian MPA. Fisheries Res. 177, 59–70. doi: 10.1016/j.fishres.2015.12.014

Afonso P., Fontes J., Giacomello E., Magalhães M. C., Martins H. R., Morato T., et al. (2020). The azores: A mid-atlantic hotspot for marine megafauna research and conservation. Front. Mar. Sci. 6. doi: 10.3389/fmars.2019.00826

Afonso P., Fontes J., and Santos R. S. (2011). Small marine reserves can offer long term protection to an endangered fish. Biol. Conserv. 144, 2739–2744. doi: 10.1016/j.biocon.2011.07.028

Afonso P., Schmiing M., Fontes J., Tempera F., Morato T., and S. Santos R. (2018). Effects of marine protected areas on coastal fishes across the Azores archipelago, mid-North Atlantic. J. Sea Res. 138, 34–47. doi: 10.1016/j.seares.2018.04.003

Amorim P., Sousa P., and Menezes G. M. (2021). Sustainability status of the grouper fishery in the Azores archipelago: A length-based approach. Mar. Policy 130, 104562. doi: 10.1016/j.marpol.2021.104562

Andrade Á.B., MaChado L. F., Hostim-Silva M., and Barreiros J. P. (2003). Reproductive biology of the dusky grouper Epinephelus marginatus (Lowe 1834). Braz. Arch. Biol. Technol. 46, 373–382. doi: 10.1590/S1516-89132003000300009

Ávila S. P., Da Silva C. M., Schiebel R., Cecca F., Backeljau T., and De Frias Martins A. M. (2009). How did they get here? the biogeography of the marine molluscs of the Azores. Bull. la Societe Geologique France 180, 295–307. doi: 10.2113/gssgfbull.180.4.295

Bailey S. A. (2015). An overview of thirty years of research on ballast water as a vector for aquatic invasive species to freshwater and marine environments. Aquat. Ecosystem Health Manage. 18, 261–268. doi: 10.1080/14634988.2015.1027129

Bandín I. and Souto S. (2020). Betanodavirus and VER disease: A 30-year research review. Pathogens 9, 106. doi: 10.3390/pathogens9020106, PMID: 32050492

Baud M., Cabon J., Salomoni A., Toffan A., Panzarin V., and Bigarré L. (2015). First generic one step real-time Taqman RT-PCR targeting the RNA1 of betanodaviruses. J. Virological Methods 211, 1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jviromet.2014.09.016, PMID: 25311184

Bellance R. and Gallet de Saint-Aurin D. (1998). L’encephalite virale de loup de mer. Caraibes Med. 2, 105–114.

Boukedjouta R., Pretto T., Abbadi M., Biasini L., Toffan A., and Mezali K. (2020). Viral encephalopathy and retinopathy is endemic in wild groupers (genus Epinephelus spp.) of the Algerian coast. J. Fish Dis. 43, 801–812. doi: 10.1111/jfd.13181, PMID: 32462696

Bovo G., Gustinelli A., Quaglio F., Gobbo F., Panzarin V., Fusaro A., et al. (2011). Viral encephalopathy and retinopathy outbreak in freshwater fish farmed in Italy. Dis. Aquat. Organisms 96, 45–54. doi: 10.3354/dao02367, PMID: 21991664

Caldeira R. M. A. and Reis J. C. (2017). The Azores confluence zone. Front. Mar. Sci. 4. doi: 10.3389/fmars.2017.00037

Carriço R., Silva M. A., Menezes G. M., Vieira M., Bolgan M., Fonseca P. J., et al. (2020). Temporal dynamics in diversity patterns of fish sound production in the Condor seamount (Azores, NE Atlantic). Deep-Sea Res. Part I: Oceanographic Res. Papers 164. doi: 10.1016/j.dsr.2020.103357

Cascão I., Domokos R., Lammers M. O., Marques V., Domínguez R., Santos R. S., et al. (2017). Persistent enhancement of micronekton backscatter at the summits of seamounts in the Azores. Front. Mar. Sci. 4. doi: 10.3389/FMARS.2017.00025

Cheng L., Abraham J., Trenberth K. E., Reagan J., Zhang H. M., Storto A., et al. (2025). Record high temperatures in the ocean in 2024. Adv. Atmospheric Sci. 42, 1092–1109. doi: 10.1007/s00376-025-4541-3

Condini M. V., García-Charton J. A., and Garcia A. M. (2018). A review of the biology, ecology, behavior and conservation status of the dusky grouper, Epinephelus marginatus (Lowe 1834). Rev. Fish Biol. Fisheries 28, 301–330. doi: 10.1007/s11160-017-9502-1

Condini M. V., Hoeinghaus D. J., and Garcia A. M. (2015). Trophic ecology of dusky grouper Epinephelus marginatus (Actinopterygii, Epinephelidae) in littoral and neritic habitats of southern Brazil as elucidated by stomach contents and stable isotope analyses. Hydrobiologia 743, 109–125. doi: 10.1007/s10750-014-2016-0

Cook K. A., Hawke J. P., Groman D. B., Pretto T., Toffan A., Hanson L. A., et al. (2024). Betanodavirus meningoencephalitis in an Atlantic blue marlin. J. Veterinary Diagn. Invest. 36, 389–392. doi: 10.1177/10406387231218223, PMID: 38331725

Copernicus (2023). Record-breaking North Atlantic Ocean temperatures contribute to extreme marine heatwaves. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2761.2001.00292.x

Curtis P. A., Drawbridge M., Iwamoto T., Nakai T., Hedrick R. P., and Gendron A. P. (2001). Nodavirus infection of juvenile white seabass, Atractoscion nobilis, cultured in southern California: first record of viral nervous necrosis (VNN) in North America. J. Fish Dis. 24, 263–271. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2761.2001.00292.x

Dong T., Zeng Z., Pan M., Wang D., Chen Y., Liang L., et al. (2025). Record-breaking 2023 marine heatwaves. Science 389, 369–374. doi: 10.1126/science.adr0910, PMID: 40705884

European Environment Agency (2021). Pathways of introduction of non-indigenous species to Europe’s seas 1970-2021. Available online at https://www.eea.europa.eu/en/analysis/indicators/marine-non-indigenous-species-in/pathways-of-introduction-of.

Fennessy S. T. (2006). Reproductive biology and growth of the yellowbelly rockcod Epinephelus marginatus (Serranidae) from South-East Africa. Afr. J. Mar. Sci. 28, 1–11. doi: 10.2989/18142320609504128

Freitas R., Romeiras M., Silva L., Cordeiro R., Madeira P., González J. A., et al. (2019). Restructuring of the ‘Macaronesia’ biogeographic unit: A marine multi-taxon biogeographical approach. Sci. Rep. 9, 1–18. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-51786-6, PMID: 31690834

Frerichs G. N., Rodger H. D., and Peric Z. (1996). Cell culture isolation of piscine neuropathy nodavirus from juvenile sea bass, Dicentrarchus labrax. J. Gen. Virol. 77, 2067–2071. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-77-9-2067, PMID: 8811004

Frölicher T. L., Fischer E. M., and Gruber N. (2018). Marine heatwaves under global warming. Nature 560, 360–364. doi: 10.1038/s41586-018-0383-9, PMID: 30111788

Fukuda Y., Nguyen H. D., Furuhashi M., and Nakai T. (1996). Mass mortality of cultured sevenband grouper, Epinephelus septemfasciatus, associated with viral nervous necrosis. Fish Pathol. 31, 165–170. doi: 10.3147/jsfp.31.165

Garrabou J., Gómez-Gras D., Medrano A., Cerrano C., Ponti M., Schlegel R., et al. (2022). Marine heatwaves drive recurrent mass mortalities in the Mediterranean Sea. Global Change Biol. 28, 5708–5725. doi: 10.1111/gcb.16301, PMID: 35848527

Genin A., Levy L., Sharon G., Raitsos D. E., and Diamant A. (2020). Rapid onsets of warming events trigger mass mortality of coral reef fish. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. United States America 117, 25378–25385. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2009748117, PMID: 32958634

Gerhardinger L. C., Freitas M. O., Bertoncini Á.A., Borgonha M., and Hostim-Silva M. (2006). Collaborative approach in the study of the reproductive biology of the dusky grouper Epinephelus marginatus (Lowe 1934) (Perciformes: serranidae). Acta Scientiarum - Biol. Sci. 28, 219–226.

Haddad-Boubaker Sondès, Boughdir W., Sghaier S., Souissi J., Aida Megdich B., Dhaouadi R., et al. (2014). Outbreak of Viral Nervous Necrosis in Endangered Fish species Epinephelus costae and E. marginatus in Northern Tunisian Coasts. Fish Pathol. 49, 53–56. doi: 10.3147/jsfp.49.53

Hata N., Okinaka Y., Iwamoto T., Kawato Y., Mori K.-I., and Nakai T. (2010). Identification of RNA regions that determine temperature sensitivities in betanodaviruses. Arch. Virol. 155, 1597–1606. doi: 10.1007/s00705-010-0736-7, PMID: 20582605

He M. and Teng C. B. (2015). Divergence and codon usage bias of Betanodavirus, a neurotropic pathogen in fish. Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 83, 137–142. doi: 10.1016/j.ympev.2014.11.016, PMID: 25497669

Hereu B., Diaz D., Pasqual J., Zabala M., and Sala E. (2006). Temporal patterns of spawning of the dusky grouper Epinephelus marginatus in relation to environmental factors. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 325, 187–194. doi: 10.3354/meps325187

Hixon M., Johnson D. W., and Sogard S. M. (2014). BOFFFFs: on the importance of conserving old-growth age structure in fishery populations. ICES J. Mar. Sci. 71, 2171–2185. doi: 10.1093/icesjms/fst200

Hobday A. J., Alexander L. V., Perkins S. E., Smale D. A., Straub S. C., Oliver E. C. J., et al. (2016). A hierarchical approach to defining marine heatwaves. Prog. Oceanogr. 141, 227–238. doi: 10.1016/j.pocean.2015.12.014

Hobday A. J., Gupta A.S., Benthuysen J. A., Burrows M. T., Donat M. G., Holbrook N. J., et al. (2018). Categorizing and naming marine heatwaves. Oceanography 31, 162–173. doi: 10.5670/oceanog.2018.205

IPMA (2024). Boletim climatológico Agosto 2024 (Boletim Climatológico Mensal). Available online at: https://www.ipma.pt/resources.www/docs/im.publicacoes/edicoes.online/20240928/otpQzlqWOgqEhDYLtkiO/cli_20240801_20240831_pcl_mm_az_pt.pdf.

Iwamoto T., Mori K., Arimoto M., and Nakai T. (1999). High permissivity of the fish cell line SSN-1 for piscine nodaviruses. Dis. Of Aquat. Organisms 39, 37–47. doi: 10.3354/dao039037, PMID: 11407403

Kalyaanamoorthy S., Minh B. Q., Wong T. K. F., Von Haeseler A., and Jermiin L. S. (2017). ModelFinder: Fast model selection for accurate phylogenetic estimates. Nat. Methods 14, 587–589. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.4285, PMID: 28481363

Kara H. M., Chaoui L., Derbal F., Zaidi R., de Boisséson C., Baud M., et al. (2014). Betanodavirus-associated mortalities of adult wild groupers Epinephelus marginatus (Lowe) and Epinephelus costae (Steindachner) in Algeria. J. Fish Dis. 37, 273–278. doi: 10.1111/jfd.12020, PMID: 24397531

Kersting D. K., García-Quintanilla C., Quintano N., Estensoro I., and del Mar Ortega-Villaizan M. (2024). Dusky grouper massive die-off in a Mediterranean marine reserve. Mediterr. Mar. Sci. 25, 578–585. doi: 10.12681/MMS.38147

Kim Y., Aw T. G., and Rose J. B. (2016). Transporting ocean viromes: Invasion of the aquatic biosphere. PloS One 11, 1–18. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0152671, PMID: 27055282

Knibb W., Luu G., Premachandra H. K. A., Lu M.-W., and Nguyen N. H. (2017). Regional genetic diversity for NNV grouper viruses across the Indo-Asian region – implications for selecting virus resistance in farmed groupers. Sci. Rep. 7, 10658. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-11263-4, PMID: 28878324

Kumar S., Stecher G., and Tamura K. (2016). MEGA7: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis version 7.0 for bigger datasets. Mol. Biol. Evol. 33, 1870–1874. doi: 10.1093/MOLBEV/MSW054, PMID: 27004904

Louisy P. and Culioli J. M. (1999). Synthèse des observations sur l’activité reproductrice du mérou brun Epinephelus marginatus (Lowe 1834) en Méditerranée nord-occidentale. Mar. Life 9, 47–57.

Lovy J., Abbadi M., Toffan A., Das N., Neugebauer J. N., Batts W. N., et al. (2025). Detection and genetic characterization of red-spotted grouper nervous necrosis virus and a novel genotype of nervous necrosis virus in black sea bass from the U. S. Atlantic coast. Viruses 17. doi: 10.3390/v17091234, PMID: 41012662

Marino G. and Azzurro E. (2001). Nodavirus in dusky grouper (Epinephelus marginatus, lowe 1834) of the natural marine reserve of Ustica, South Thyrrenian Sea. Biol. Mar. Medit. 8, 837–841.

Menezes G. M., Sigler M. F., Silva H. M., and Pinho M. R. (2006). Structure and zonation of demersal fish assemblages off the Azores Archipelago (mid-Atlantic). Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 324, 241–260. doi: 10.3354/meps324241

Morato T., Varkey D. A., Damaso C., Machete M., Santos M., Prieto R., et al. (2008). Evidence of a seamount effect on aggregating visitors. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 357, 23–32. doi: 10.3354/meps07269

Munday B. L., Kwang J., and Moody N. (2002). Betanodavirus infections of teleost fish : a review. J. Fish Dis. 25, 127–142. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2761.2002.00350.x

Nguyen L. T., Schmidt H. A., Von Haeseler A., and Minh B. Q. (2015). IQ-TREE: A fast and effective stochastic algorithm for estimating maximum-likelihood phylogenies. Mol. Biol. Evol. 32, 268–274. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msu300, PMID: 25371430

Oliver E. C. J., Donat M. G., Burrows M. T., Moore P. J., Smale D. A., Alexander L. V., et al. (2018). Longer and more frequent marine heatwaves over the past century. Nat. Commun. 9, 1–12. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-03732-9, PMID: 29636482

Panzarin V., Cappellozza E., Mancin M., Milani A., Toffan A., Terregino C., et al. (2014). In vitro study of the replication capacity of the RGNNV and the SJNNV betanodavirus genotypes and their natural reassortants in response to temperature. Veterinary Res. 45, 56. doi: 10.1186/1297-9716-45-56, PMID: 24885997

Panzarin V., Fusaro A., Monne I., Cappellozza E., Patarnello P., Bovo G., et al. (2012). Molecular epidemiology and evolutionary dynamics of betanodavirus in southern Europe. Infection Genet. Evolution: J. Mol. Epidemiol. Evolutionary Genet. Infect. Dis. 12, 63–70. doi: 10.1016/j.meegid.2011.10.007, PMID: 22036789

Panzarin V., Toffan A., Abbadi M., Buratin A., Mancin M., Braaen S., et al. (2016). Molecular basis for antigenic diversity of genus Betanodavirus. PloS One 11, 1–18. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0158814, PMID: 27438093

Pollard D. A., Afonso P., Bertoncini A. A., Fennessy S., Francour P., and Barreiros J. (2016). Epinephelus marginatus (IUCN Red List of Threatened Species). doi: 10.2305/IUCN.UK.2018-2.RLTS.T7859A100467602.en

Quartau R., Madeira J., Miichell N. C., Tempera F., Silva P. F., and Brandão F. (2015). The insular shelves of the Faial-Pico Ridge (Azores archipelago): A morphological record of its evolution. Geochem. Geophysics Geosystems 16, 1401–1420. doi: 10.1002/2015GC005733

Sahul Hameed A. S., Ninawe A. S., Nakai T., Chi S. C., and Johnson K. L. (2019). ICTV virus taxonomy profile: Nodaviridae. J. Gen. Virol. 100, 3–4. doi: 10.1099/jgv.0.001170, PMID: 30431412

Santos R. S., Hawkins S., Monteiro L. R., Alves M., and Isidro E. J. (1995). Marine research, resources and conservation in the Azores. Aquat. Conservation: Mar. Freshw. Ecosyst. 5, 311–354. doi: 10.1002/aqc.3270050406

Scharsack J. P. and Franke F. (2022). Temperature effects on teleost immunity in the light of climate change. J. Fish Biol. 101, 780–796. doi: 10.1111/jfb.15163, PMID: 35833710

Smith K. E., Burrows M. T., Hobday A. J., King N. G., Moore P. J., Sen Gupta A., et al. (2023). Biological impacts of marine heatwaves. Annu. Rev. Mar. Sci. 15, 119–145. doi: 10.1146/annurev-marine-032122-121437, PMID: 35977411

Spillman C. M., Smith G. A., Hobday A. J., and Hartog J. R. (2021). Onset and decline rates of marine heatwaves: global trends, seasonal forecasts and marine management. Front. Climate 3. doi: 10.3389/fclim.2021.801217

Takahashi C., Lourenço N., Lopes T., Rall V., and Lopes C. (2008). Ballast water: a review of the impact on the world public health. J. Venomous Anim. Toxins Including Trop. Dis. 14, 393–408. doi: 10.1590/S1678-91992008000300002

Toffan A., Panzarin V., Toson M., Cecchettin K., and Pascoli F. (2016). Water temperature affects pathogenicity of different betanodavirus genotypes in experimentally challenged Dicentrarchus labrax. Dis. Aquat. Organisms 119, 231–238. doi: 10.3354/dao03003, PMID: 27225206

Toffan A., Pascoli F., Pretto T., Panzarin V., Abbadi M., Buratin A., et al. (2017). Viral nervous necrosis in gilthead sea bream (Sparus aurata) caused by reassortant betanodavirus RGNNV/SJNNV: an emerging threat for Mediterranean aquaculture. Sci. Rep. 7, 46755. doi: 10.1038/srep46755, PMID: 28462930

Toffolo V., Negrisolo E., Maltese C., Bovo G., Belvedere P., Colombo L., et al. (2007). Phylogeny of betanodaviruses and molecular evolution of their RNA polymerase and coat proteins. Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 43, 298–308. doi: 10.1016/j.ympev.2006.08.003, PMID: 16990016

Torres P., Milla i Figueras D., Diogo H., and Afonso P. (2022). Risk assessment of coastal fisheries in the Azores (north-eastern Atlantic). Fisheries Res. 246, 106156. doi: 10.1016/j.fishres.2021.106156

Valencia J. M., Grau A., Pretto T., Pons J., Jurado-Rivera J. A., Castro J. A., et al. (2019). Viral encephalopathy and retinopathy (VER) disease in epinephelus marginatus from the Balearic Islands marine protected areas. Dis. Aquat. Organisms 135, 49–58. doi: 10.3354/dao03378, PMID: 31244484

Valls A., Gascuel D., Guénette S., and Francour P. (2012). Modeling trophic interactions to assess the effects of a marine protected area: Case study in the NW Mediterranean Sea. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 456, 201–214. doi: 10.3354/meps09701

Vázquez-Salgado L., Olveira J. G., Dopazo C. P., and Bandín I. (2020). Role of rotifer (Brachionus plicatilis) and Artemia (Artemia salina) nauplii in the horizontal transmission of a natural nervous necrosis virus (NNV) reassortant strain to Senegalese sole (Solea Senegalensis) larvae. Veterinary Q. 40, 205–214. doi: 10.1080/01652176.2020.1810357, PMID: 32813983

Vendramin N., Patarnello P., Toffan A., Panzarin V., Cappellozza E., Tedesco P., et al. (2013). Viral Encephalopathy and Retinopathy in groupers (Epinephelus spp.) in southern Italy: a threat for wild endangered species? BMC Veterinary Res. 9, 20. doi: 10.1186/1746-6148-9-20, PMID: 23351980

Vieira P. E., Desiderato A., Holdich D. M., Soares P., Creer S., Carvalho G. R., et al. (2019). Deep segregation in the open ocean: Macaronesia as an evolutionary hotspot for low dispersal marine invertebrates. Mol. Ecol. 28, 1784–1800. doi: 10.1111/mec.15052, PMID: 30768810

Keywords: viral nervous necrosis, groupers, climate change, ocean warming, epizootic, North Atlantic

Citation: Gomes I, Novoa-Pabon A, Abbadi M, Pretto T, Rosa J, Silva L, Torres P, Marsella A, Afonso P and Toffan A (2025) Marine heatwave associated Betanodavirus outbreak in wild groupers of the Azores. Front. Mar. Sci. 12:1712250. doi: 10.3389/fmars.2025.1712250

Received: 24 September 2025; Accepted: 17 November 2025; Revised: 06 November 2025;

Published: 17 December 2025.

Edited by:

Davide Asnicar, Huntsman Marine Science Centre, CanadaReviewed by:

Diego K. Kersting, University of Barcelona, SpainSutanti Sutanti, Badan Riset dan Inovasi Nasional (BRIN), Indonesia

Copyright © 2025 Gomes, Novoa-Pabon, Abbadi, Pretto, Rosa, Silva, Torres, Marsella, Afonso and Toffan. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Inês Gomes, aXN0Z29tZXNAZ21haWwuY29t

Inês Gomes

Inês Gomes Ana Novoa-Pabon

Ana Novoa-Pabon Miriam Abbadi

Miriam Abbadi Tobia Pretto

Tobia Pretto Joana Rosa

Joana Rosa Luís Silva

Luís Silva Paulo Torres

Paulo Torres Andrea Marsella

Andrea Marsella Pedro Afonso

Pedro Afonso Anna Toffan

Anna Toffan