Abstract

The conflicts between pinnipeds and coastal fisheries are harmful for both pinniped conservation and fishermen’s livelihood. In Hokkaido, Japan, negative interactions between Steller sea lions (SSL) and gillnet and set net fisheries have been an issue for decades. Damage control measures have been implemented, but little is known about fishermen’s perception of the conflict. The recent increase in human dimension research has demonstrated the necessity of this approach in conflict mitigation and resolution. This study aims to clarify the fishermen’s perception of and attitude toward SSL and mitigation methods, and explores the context in which fishermen face this conflict. We conducted 29 on-site interviews with fishermen in several fishing villages along the Sea of Japan and Sea of Okhotsk coasts. We found that most fishermen approved population control as a damage control measure and considered it the only effective method. However, they were open to the development of non-lethal methods. Gillnet and set net fishermen’s perception of SSL's ecological role was more complex than just a threat to their catch. Gillnet fishermen showed a more negative attitude toward SSL compared to set net fishermen. We conclude that fishermen need solutions not only to mitigate the conflict with SSL but also to maintain a decent livelihood while practicing their fishing activity. Our findings explored the larger context surrounding conflict with wildlife and provided valuable information for developing strategies to coexist with wildlife.

1 Introduction

Conflicting interactions between small-scale fisheries and pinnipeds have been reported from all over the world (Tixier et al., 2021). Operational interactions such as depredation, damage to fishing gear or bycatch are detrimental to both pinniped conservation and fishermen’s livelihood. Therefore, it is important to establish strategies to open the door for coexistence between pinnipeds and fisheries by finding ways to protect both parties. For example, deterrence tools have been widely implemented in fisheries and aquaculture (Nelson et al., 2006; Götz and Janik, 2013). Modified fishing gear with stronger material or added features like seal exclusion device (SED) (Calamnius et al., 2018; Iriarte et al., 2020) or barriers (Isono et al., 2013) have also been successfully introduced (Westerberg et al., 2006). In some places, the alternative consisted in modifying the fishing technique by changing the fishing gear (Königson et al., 2015). Indirect measures such as financial compensation have also been implemented (Varjopuro, 2011). The strategies have to be adapted not only to the predator species and fishing technique, but also to the cultural and political context of the region where the conflict occurs, as it is the case with adaptations to climate change (Adger et al., 2013).

In the Japanese waters, conflicts between coastal fisheries and Steller sea lions (Eumetopias jubatus, SSL) have been the cause of consequent damage annually over the last decades (Sasakawa, 1989). In 2023, the conflict with SSL had cost around 727 million ¥ (4.9 million dollars) accounting for catch loss and damaged gear (Hokkaido Government, 2024b). Coastal fishing in Hokkaido is important economically and culturally, especially in remote and sparsely populated areas. However, due to the difficulty in passing the business to the next generation and the low fishing income, the fisheries are threatened. Especially on the western coasts of Hokkaido, the interactions with SSL have been serious and have impacted fishermen’s livelihood. Therefore, SSL-fisheries conflict management is necessary for the continuation of coastal fishery. Despite considerable efforts to mitigate the damage, the level of conflict is still considered unsatisfactory for the fishing communities. Therefore, a different approach is needed.

Conflict with wildlife extends beyond the physical damage caused by animals and is deeply embedded within social contexts (Dickman, 2010). In human–wildlife conflict research, the human dimension, i.e. the social factors influencing how people perceive the conflict, the wildlife involved, and potential solutions, has become increasingly recognized as essential for progress toward coexistence (Dickman, 2010; Guerra, 2019). These factors can often intensify perceptions and reactions more than the actual magnitude of the damage itself, meaning that successful long-term management requires understanding these social mechanisms (Butler et al., 2015).

Despite the severity and long history of interactions between SSL and coastal fisheries in Hokkaido, the human dimension of this specific conflict remains largely unexplored. In particular, how fishermen, the most directly impacted stakeholders, perceive SSL, the conflict and the mitigation strategies has not yet been investigated. A previous study on human dimension of seal-fisheries conflict stressed that understanding the attitudes toward mitigation measures and their influence on the stakeholder livelihood was an important component of conflict resolution (Waldo et al., 2020). It has also been established that people’s attitude toward the conflicting wildlife and perceived ecological roles, including evaluations of both risks and benefits of predators, can strongly shape attitudes toward mitigation measures including support for or opposition to lethal methods (Frank et al., 2019; Jackman et al., 2024).

In this study, we explore the human dimension of SSL-Hokkaido small-scale fisheries. We examined fishermen’s (1) attitudes toward existing and potential mitigation measures, (2) attitudes toward SSL, and (3) perception of SSL ecological role. We focused on two major coastal fisheries that differ in their level of interaction with SSL: gillnet and Japanese set net fisheries. To capture a wide range of perspectives from the fishing community, we conducted face-to-face interviews in 12 fishing villages within SSL distribution areas. By opening the dialogue directly with fishermen, we aim to provide the first detailed assessment of the human dimension in this conflict, laying essential groundwork for trust-building and the development of socially supported pathways toward pinniped–fisheries coexistence (Butler et al., 2015; Guerra, 2019).

2 Methods

2.1 Study area

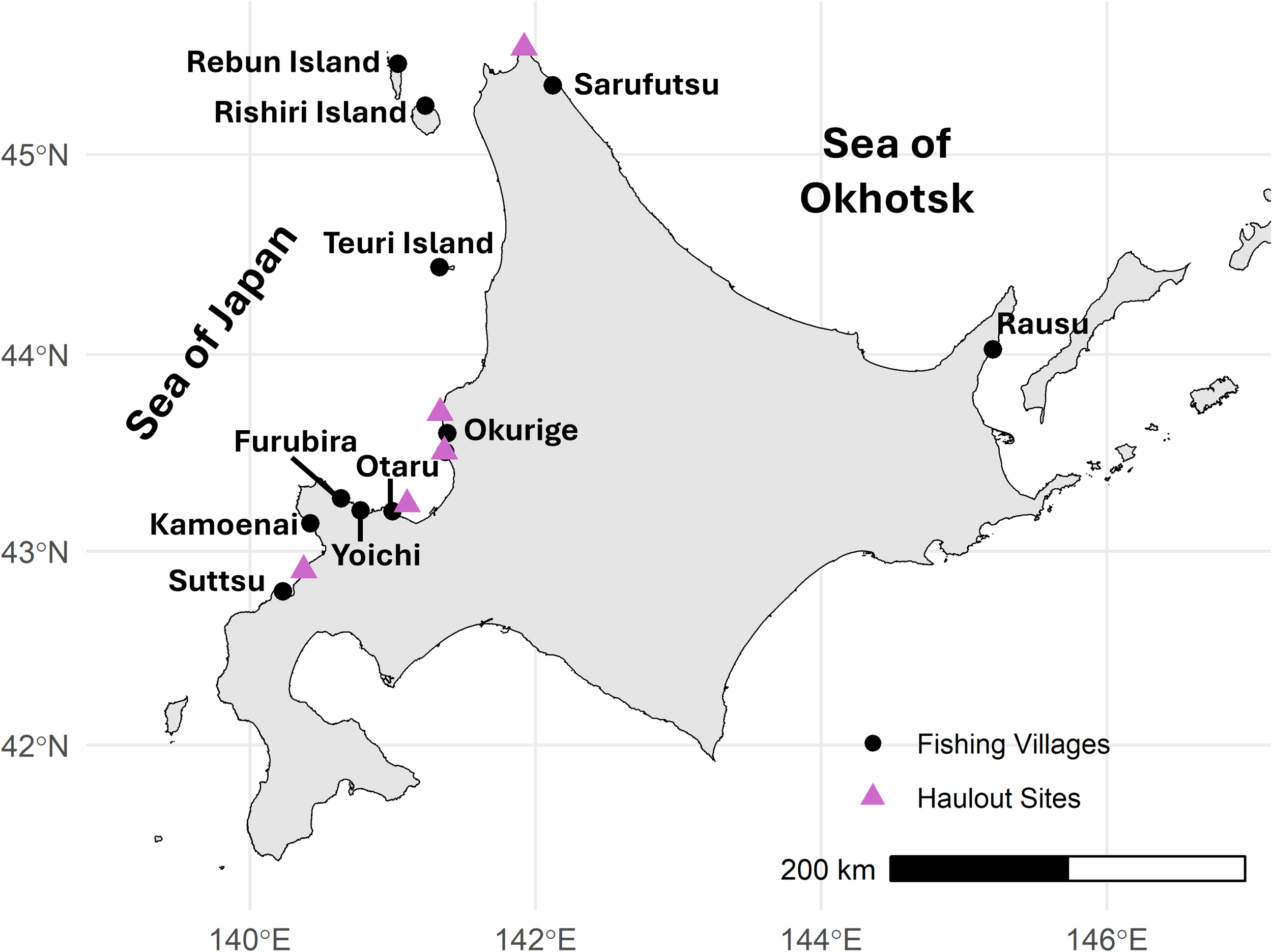

Hokkaido Island is the second largest and the northern most island in Japan. It is surrounded by the Sea of Japan on the western side, the Sea of Okhotsk on the North-East Side and the Pacific Ocean on the South and East sides (Figure 1). Each coastline is under the influence of different current systems: the Tsugaru Warm Current, the Eastern Sakhalin Current and the Oyashio Current, respectively (Tsujino et al., 2008). This complex oceanography makes the area productive for marine life and fishery. SSL migrate every winter from their natal rookeries in Russia and the Kuril Islands to the waters around Hokkaido (Burkanov and Loughlin, 2005). SSL are opportunistic feeders. From November through May they winter in the Hokkaido coastal areas in the Sea of Japan and the Sea of Okhotsk. Their diet is composed of several species that are important commercial species including giant Pacific octopus (Enteroctopus dofleini), Pacific cod (Gadus macrocephalus), walleye pollock (Gadus chalcogrammus), herring (Clupea pallasii), and flounders (Goto et al., 2017). On the other hand, fishing is also active in this area. Two passive gear fisheries, bottom gillnet fisheries and set net (pound net) fisheries are the most affected fisheries by the interaction with SSL (Japan Fisheries Research and Education Agency, 2024). Gillnet fisheries target mainly herring, flounders, cod, monkfish (Lophiidae spp.) and Okhotsk Atka mackerel (Pleurogrammus azonus). They are generally small-scale family-run operations that generate relatively low annual incomes (Hokkaido Government, 2024a; unpublished data). Thus, they suffer high catch and gear damage from SSL interaction. In comparison, set net fisheries mainly target salmon species in spring and autumn, outside of the main migrating season of SSL to Hokkaido waters, therefore suffering less damage. In addition, in areas where the main targets are Pacific cod and Okhotsk Atka mackerel during winter, the use of reinforced net is well established, therefore limiting the damage from SSL (Isono et al., 2013). An illustration of the nets is provided in Appendix A (gillnet) and B (set net).

Figure 1

Map of Hokkaido showing the visited fishing village and the main known haulout sites of Steller sea lions.

2.2 Research design

We compiled an interview form based on the previous studies (Gruber and Orbach, 2014; Cummings et al., 2019; Waldo et al., 2020) and discussions with fishermen in November 2022. It contained closed- and open-ended questions, aiming to cover most aspects of the interactions with SSL, including respondents’ socio-economic information, fishing activities, interactions with SSL, impact of this interaction on their livelihood, attitude toward SSL, management measures, and one final free question enabling them to broaden the subject if necessary. This question form was meant to provide an overview of the human dimension of the fisheries-SSL conflict. From these questions, we focused on 12 question items grouped into four categories: perceived ecological role of SSL (3 items), attitudes toward SSL (4 items), attitudes toward management measures (2 items) and conditions for coexistence with SSL (3 items). The question items for each category are described in Appendix C. All questions were coded on a 5-points scale ranging from disagree = -2 to agree = +2. We also analyzed the themes brought up in the final open question.

2.3 Interview process

Fishermen were recruited either by direct introduction from a researcher known by the interviewee or by requiring the help of the local fisheries’ cooperative officers. The interviews were conducted in Japanese by the principal investigator. To minimize the language barrier, at least one Japanese person accompanied the investigator to assist with the interview. Fishermen were interviewed one at a time except for two occasions when three and two fishermen were interviewed together (Appendix D). The participants were given a short explanation of the content of the interview, use of collected data and respect for anonymity. They were informed that they could skip any question or resign from the interview at any time and were asked to allow the interview to be audio-recorded.

From April 24th 2023 to August 21st 2024, we interviewed a total of 29 fishermen (17 gillnets, 11 set nets, 1 both) in 12 fishing villages. The opportunities to contact participants were very limited. In Japan, it is not well received to ask fishermen to provide information on who could be interested in participating in interviews. Therefore, we could not use the snowball method to increase the number of participants in our study. We cannot assume that the results about attitudes and perceptions presented in this study represent all fishermen in Hokkaido and further studies involving more participants are necessary to confirm our preliminary findings. Nevertheless, 29 participants are considered sufficient for thematic and nuance saturations (Wutich et al., 2024). Therefore, we can assume that the themes raised during the interviews can provide an adequate framework for further studies.

2.4 Data processing and analysis

The interviews were transcribed using the software Notta.ai (Notta Co., Ltd., Chiyoda, Tokyo, Japan) supporting Japanese language. The transcription accuracy was checked by two native Japanese helpers. The data were then translated using two different sources (ChatGPT, OpenAI and Google Translate, Google) to minimize the risk of loss in translation. We verified the internal consistency of our constructs of ecological role, attitude toward SSL and conditions for coexistence with Cronbach’s alpha reliability test (Cronbach, 1951). The coefficients were 0.49 for the ecological role, 0.72 for the attitude toward SSL and 0.66 for the conditions for coexistence. Even though the coefficient were low for ecological role and conditions for coexistence, the number of items were small (3 items), thus were considered acceptable (Tavakol and Dennick, 2011; Vaske, 2019). To detect a difference in perception and attitude between gillnet and set net fishermen, we used the potential conflict index (PCI2) as a quantitative measure for the closed-ended questions (Vaske et al., 2010). This index had been developed to facilitate the visualization of data in human dimension research (Manfredo et al., 2003). The index provides information on the potential for conflict between and within groups represented by bubbles of different colors and sizes respectively. The response variables are the answers of each of the 12 question items and the explanatory variable is the net used by the fishermen. The colored bubbles are placed on a vertical axis representing the mean answer for one group ranging from -2 (disagree) to +2 (agree). The bubble size represents the potential conflict ranging from 0 to 1 within the same group. An index of 0 indicates a consensus, meaning that all answers are similar. An index of 1 indicates a conflict, with answers at both extremes. The PCI2 were computed using the material provided in (Vaske et al., 2010). To test whether the two groups of fishermen were significantly different, we used the Mann-Whitney U test with a p-value lower than 0.05 considered as significant. All tests were performed on R 4.5.1 (R Core Team, 2024).

In addition, due to the explorative nature of this study, the recurrent themes that emerged from the open-ended part of the interview were summarized using thematic content analysis. Using (Burnard et al., 2008) method, we coded the transcription of the respondents’ answers into topics which were then grouped into themes. This allows a broader perception of the possible drivers shaping fishermen’s attitudes and perceptions of the fishery-SSL conflict.

3 Results

We interviewed 17 gillnet fishermen, 11 set net fishermen and one who uses both fishing gears when SSL are present in Hokkaido (Table 1). The latter was included in both groups. The respondent fishermen were all males. Fishing was the main source of income for all of them.

Table 1

| Age category | n | Gender | n | Fishing as the main source of income | n | Main net used | n |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 20’s | 1 | Male | 29 | Yes | 29 | Gillnet | 17 |

| 30’s | 2 | Female | 0 | No | 0 | Japanese set net | 11 |

| 40’s | 10 | Both | 1 | ||||

| 50’s | 6 | ||||||

| 60’s | 6 | ||||||

| 70’s | 4 |

Socio-demographics and main fishing gear of the interviewed fishermen (n = 29).

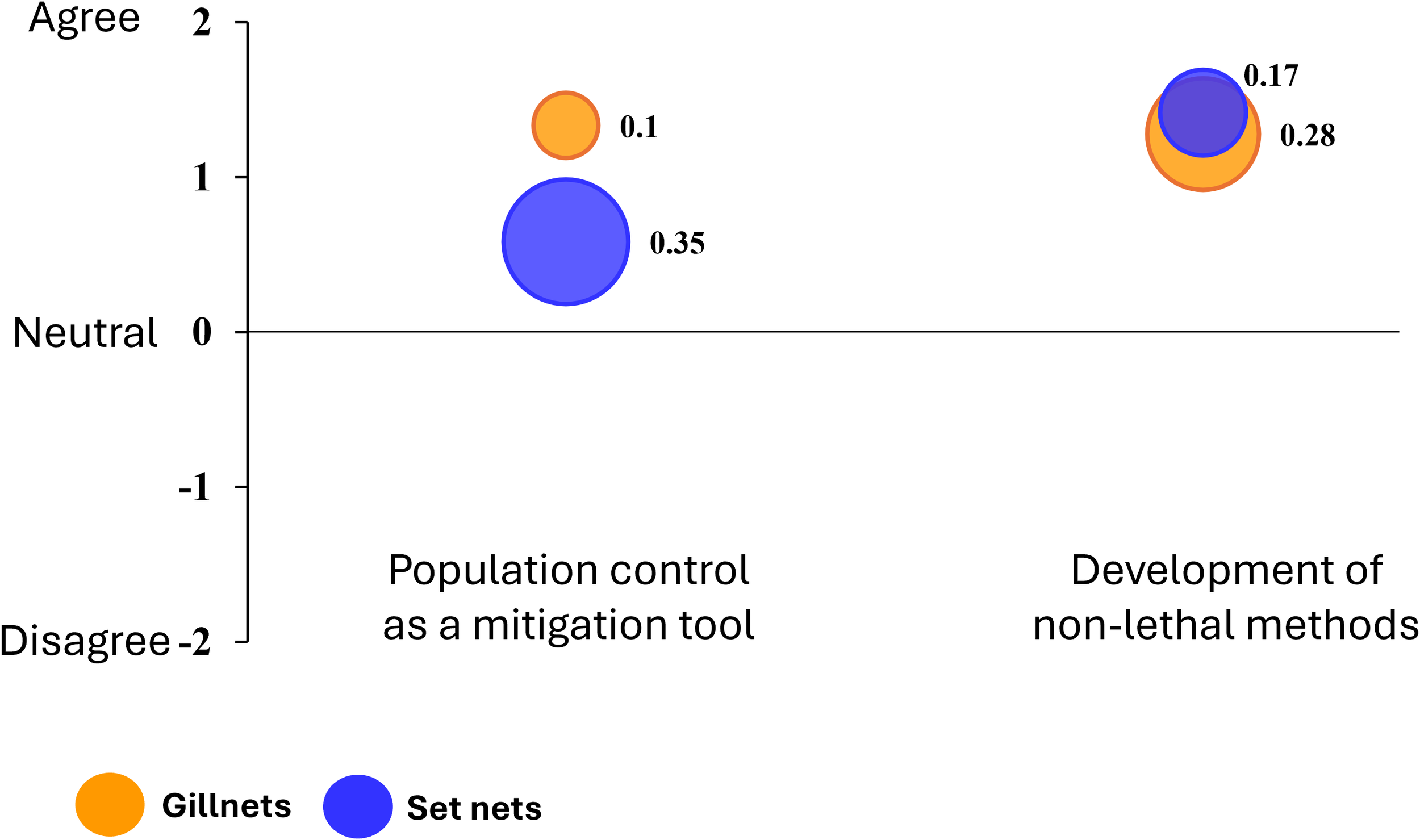

3.1 Mitigation measures

We inquired fishermen about their attitude toward SSL population control and the need to develop non-lethal methods. Twenty out of 29 fishermen were in favor of population control as a mitigation measure (Figure 2). Gillnet fishermen had a slight tendency of being more strongly favorable and had less internal conflict than set net fishermen. The main reason for approving population control was that there is no other effective method to deal with the damage. During the interview, three fishermen referred to the killing as target removal, meaning killing only the sea lions specifically attacking the net, rather than as population control stating that protecting the net was what they needed.

Figure 2

Potential conflict index (PCI2) for the attitudes toward population control and development of non-lethal methods for gillnets (orange) and set nets (blue). The vertical position of the bubbles indicates the level of agreement with a statement ranging from -2 = disagree to 2 = agree. The size of the bubbles corresponds to the value of the PCI2 ranging from 0 to 1, with a lower value representing a higher degree of consensus withing a group.

Like I just said, there’s no choice but to carry out lethal control. To eliminate the damage, there’s no other option but to kill them. I’ve been doing this for decades myself. (Yoichi).

[ … ] there are individuals nearby the nets causing trouble, so that’s probably it. So when we ask hunters for help, they are likely to target the prey nearby. (Sarufutsu 2, the number after the location represents the interview number of this location).

Among the nine fishermen who remained neutral or disagreed, they pointed out the feasibility and potential impacts of the measure on ecosystems or showed some empathy toward living beings.

I mean, killing a living creature, that’s what it means, right? Instead of that, it’s better to drive them away, like throwing something at them. (Furubira).

In reality, even if you kill them, it’s not like you can wipe them all out. And killing them could also disrupt the ecosystem, there’s really no clear answer to that. (Rishiri 2).

Fishermen were generally open to the development of non-lethal methods other than population control. The methods mentioned during the interviews mostly concerned damage reduction, such as sound repellent or reinforced nets, but one fisherman also talked about an idea to help the fishing activity in general. One motivation for this was the need for additional support, as the current situation is unacceptable.

Well, it’s that there really isn’t much support. (Rishiri 1).

As the fisheries sector is currently on an upward trend, looking ahead to the future, maybe we need to start thinking about different fishing methods compared to the past, not just for herring but for other catches too. We might need new approaches. That’s important not only for safe operations but also to increase landings. (Okurige).

On the other hand, fishermen were also skeptical about the possibility of finding such alternatives. These doubts were also brought up by the ones who agreed to the importance of developing alternatives.

No, it isn’t [meaningful]. It’s not even a matter of whether [developing new non-lethal methods] is meaningful or not, is there really anything at all? (Rebun 1).

3.2 Conditions for coexistence

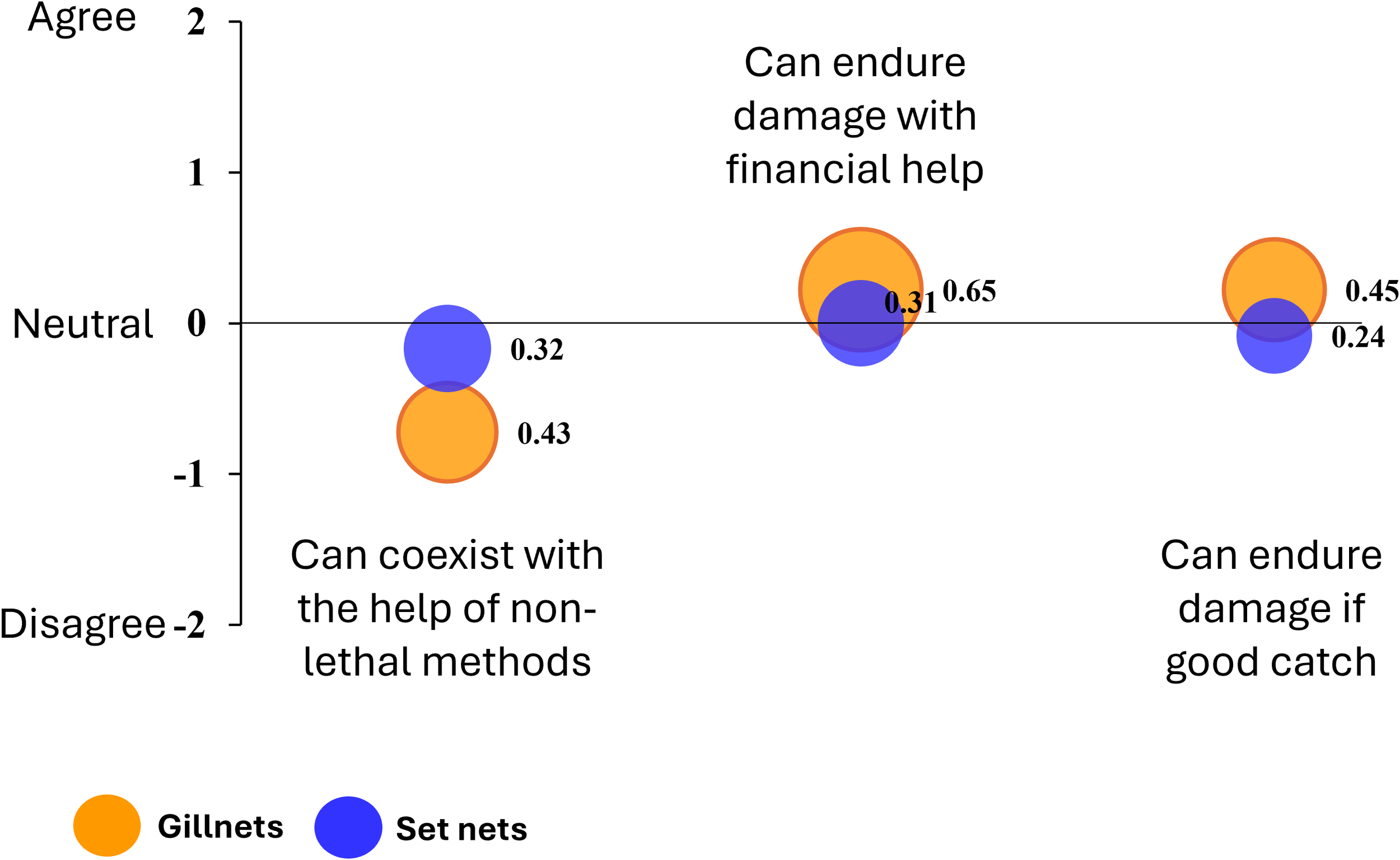

We then explored some possible conditions that could help fishermen coexist with SSL or tolerate the damage (Figure 3). Coexistence with only non-lethal methods was considered difficult in the current situation for the same reasons presented in the above section (3.1).

Figure 3

Potential conflict index (PCI2) for the attitude toward possible conditions for coexistence with SSL and damage tolerance for gillnets (orange) and set nets (blue). The vertical position of the bubbles indicates the level of agreement with a statement ranging from -2 = disagree to 2 = agree. The size of the bubbles corresponds to the value of the PCI2 ranging from 0 to 1, with a lower value representing a higher degree of consensus withing a group.

Fishermen showed a lukewarm attitude toward compensation. Half of the fishermen regardless of gear types said that they would be happy to receive compensation for SSL damage and that it would help to tolerate the damage. The other half showed some skepticism about how the method would be implemented or stressed that they want to practice fishing rather than to rely on compensation.

This is difficult, not in terms of the amount of money, but regarding the catch volume or the value of the catch. If there were compensation for taking those and converting them into money, then that would be fine. However, it feels like relying on that compensation might not be the best approach. (Sarufutsu 3).

I mean, we want to catch fish, right? That’s what it’s about. It’s not really about what kind of compensation there is, the point is, we’re fishermen, and we want to catch plenty of fish. So I’d rather things stay the way they’ve always been. I don’t really like the idea of relying on compensation. If we go down that road, it feels like nothing really matters anymore. Just because there’s compensation, it’s like I’d start to lose who I am. I’m a fisherman, after all. (Rebun 3).

Finally, we asked about whether a good catch could help them tolerate the damage from SSL. The fishermen interpreted the question in two different ways. Some respondents considered the question of whether the number of fish caught is abundant or not. Among them, eleven fishermen agreed that an abundant catch would help tolerate the damage. They explained that during “good catch” days, the damage looks smaller even when a lot of SSL are present. In contrast, others remarked that the number of SSL increases with high catch and therefore, the damage also increases when the catch is high. The second interpretation was whether the catch brings decent money or not. In that second case, the general answer was that, similar to compensation, making more money would not help with tolerating the damage. This confirms the fact that one of the needs of the fishermen is the satisfaction of providing fish rather than just the financial aspect. About the second meaning, although taking more fish is helpful, no matter the amount of catch, it is not tolerable when the level of damage is too high.

Yeah, so if that happens, the number of sea lions will also increase because there’s food for them. (Hamamasu).

3.3 Perception of the role of SSL

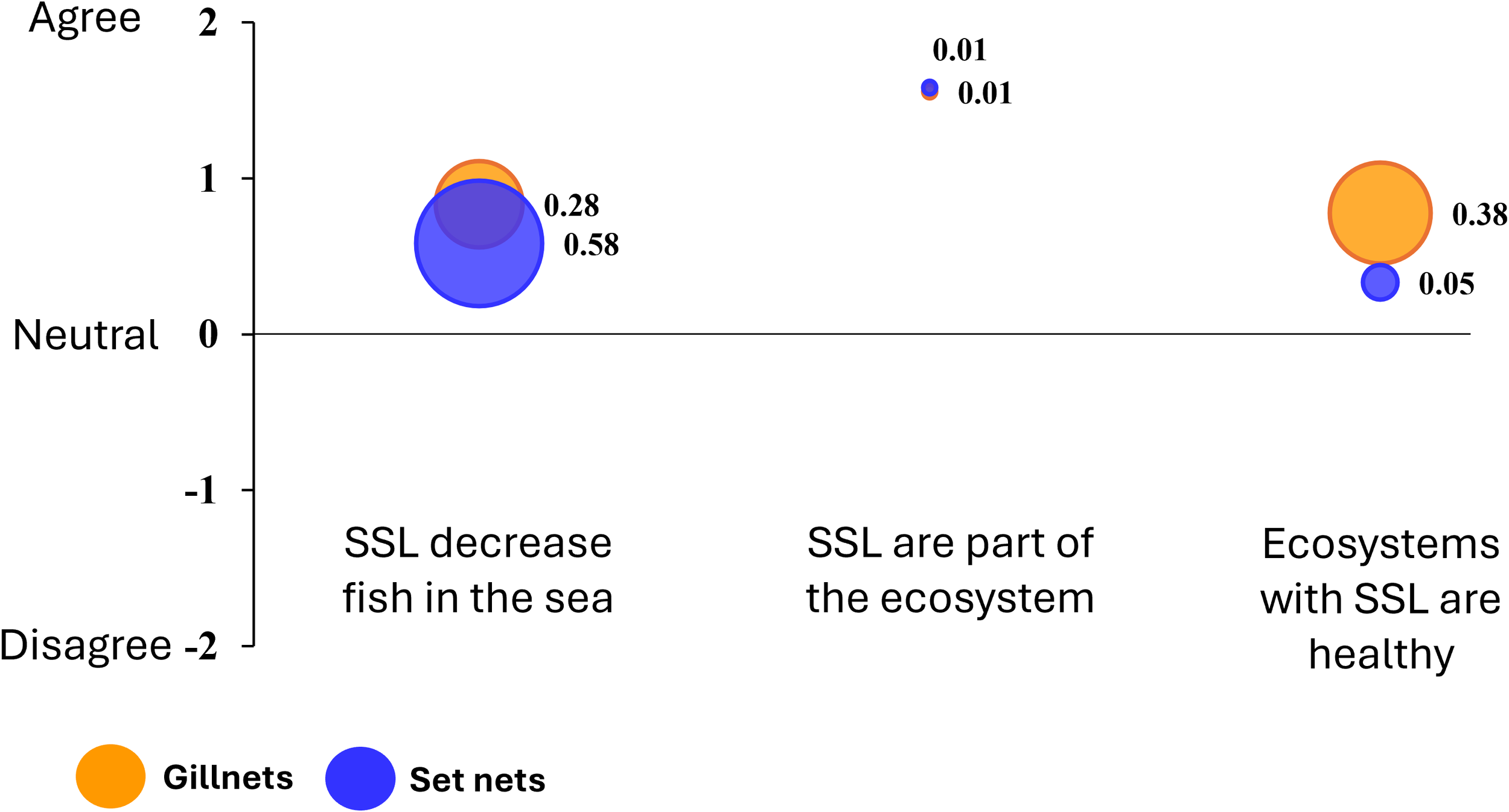

In answering the questions about their perception of the role of SSL in the ecosystem, all fishermen agreed that SSL are a natural part of the environment (Figure 4). However, both groups mostly agreed that SSL decrease fish abundance in the sea. Of these, set net fishermen showed a higher potential conflict index within the group (0.58), reflecting the fact that three of them thought that SSL impact on fish stock was unclear or that humans, rather than SSL, were the culprits:

Figure 4

Potential conflict index (PCI2) for the perceived ecological role of Steller sea lions for gillnets (orange) and set nets (blue). The vertical position of the bubbles indicates the level of agreement with a statement ranging from -2 = disagree to 2 = agree. The size of the bubble corresponds to the value of the PCI2, ranging from 0 to 1, with a lower value representing a higher degree of consensus within a group.

They eat about 30 kilos a day, right? Just one of them, in a single day. (Rausu 4).

No, that [SSL] doesn’t matter. I don’t know how many tons of sea lions there are, but I don’t think they eat enough to impact the resources. Humans are the ones making a significant impact, right? It’s clear that the damage caused by sea lions [to the fishery stocks] is limited. (Suttsu).

Similarly, even though both groups considered an environment with SSL as healthy, the gillnet fishermen presented a higher potential for conflict (0.43), with a few who did not view SSL presence as healthy.

I don’t know if you can call it ‘healthy.’ Can you really call the sea lions’ situation healthy? After all, they weren’t here in the past. (Yoichi).

That’s difficult. Perspectives vary by region, but it’s definitely not healthy around here. (Sarufutsu 2)

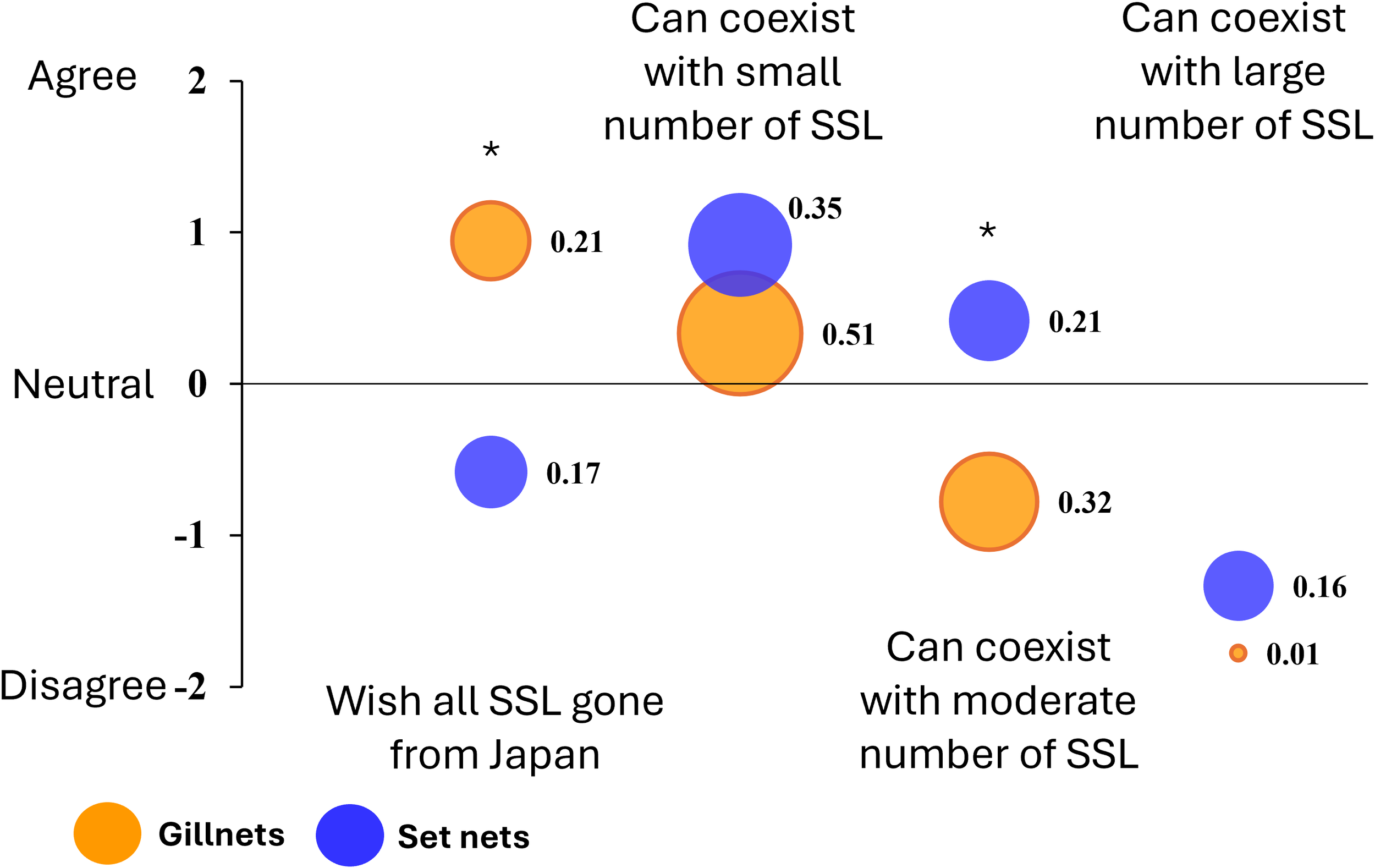

3.4 Tolerance toward SSL

The last set of questions inquired about the attitude, here presented as the tolerance, toward SSL (Figure 5). Gillnet and set net fishermen showed a clear difference in tolerance toward SSL. Gillnet fishermen were significantly less tolerant toward SSL as they wished for SSL to be gone from Japanese waters (p-value = 0.002). They also answered that they could tolerate only a small number of SSL (p-value = 0.020). On the other hand, set net fishermen were more accepting of SSL as they did not wish for a total disappearance of SSL from Japanese waters and agreed to coexistence unless there were too many SSL. The conflict within groups was limited, except for the question about the coexistence with a small number of SSL. The main issue raised in this question was the severity of damage to the fishing gear. Several fishermen stated that they could consider coexisting with SSL without damage. On the other hand, coexistence would not be possible even with a small number of SSL if the level of damage is high.

Figure 5

Potential conflict index (PCI2) for the attitude toward Steller sea lions for gillnets (orange) and set nets (blue). The vertical position of the bubbles indicates the level of agreement with a statement ranging from -2 = disagree to 2 = agree. The size of the bubble corresponds to the value of the PCI2 ranging from 0 to 1, with a lower value representing a higher degree of consensus within a group. The * indicates the significant difference between groups.

Yes, even if there are many of them, it’s fine if they don’t cause damage. But even a few, if they cause harm, feels unpleasant. (Teuri 2)

3.5 Other recurrent themes

Eighteen fishermen gave comments in addition to what has been discussed during the structured part of the interview. Here we report on the three main themes that emerged from these additions.

3.5.1 The damage and the impact on the livelihood

The damage was a recurrent theme across all interviews and questions and evoked again by 10 fishermen in the last question. Specifically, how this damage is related to the theme of the fishermen livelihood which was mentioned by 6 fishermen in the last question. Fishermen expressed the harshness of their profession and how the conflict with SSL was painfully adding to their burdens.

It’s just that, you know, they tear up the nets and snatch the fish, that’s the only reason we think, “These bastards!” (Furubira)

But yeah, there’s still quite a lot of sea lion damage going on. Even now, catching fish doesn’t really bring in money, to be honest. So if the damage gets any worse, I don’t think we can keep going, it might just be impossible. (Teuri 3)

3.5.2 Need for help from the government

Six fishermen mentioned that they wished for some help from the government and revealed a negative attitude toward it. They felt that the results of the government’s actions were invisible or not properly communicated and that the issue of the SSL conflict was not taken seriously.

So, you know, they’re researching things like what kind of behavior the sea lions show, what they come here to eat, what they’re after — but whether they’ve actually reached any real answers or not, we just don’t know. It feels like, what are they doing, just killing time and wasting unnecessary money? (Okurige)

But up until now, there’s been no support, they just tell us: ‘File a damage report. The sea lions will keep eating your fish. Learn to coexist with them.’ For us fishermen, that naturally turns into, ‘They’re eating our catch, so let’s just kill them, let’s wipe them out.’ But in the end, just like with [brown] bears, if we’re expected to coexist, then at the national level, they need to recognize, ‘Okay, that’s just how it is.’ Still, when landings are getting smaller, not necessarily because of sea lion damage, but as the overall catch keeps decreasing and we can’t make a living, and on top of that we’re taking hits from the sea lions, the government should step in and say, ‘Let’s provide some compensation here.’ I think that’s what a lot of fishermen are hoping for. (Rausu 1)

4 Discussion

4.1 Attitude toward current and possible mitigation measures

Our study attempted to contextualize fishermen’s perception of the conflict with SSL by investigating their perception and attitudes toward SSL and mitigation measures. Fishermen approved of population control as a mitigation measure and currently saw it as the only solution. In their study of fishermen and local people’s attitudes toward management measures, Waldo et al. (2020) also found that culling was seen as the only option by fishermen. This was also reported by Cleary (2021), who found that when some conservation measures were considered harmful for the fishing communities, culling was considered the unique option. There are often calls for culls in fishing communities where the conflict with seals or sea lions is very intense or when there is a lack of non-lethal alternatives (Königson et al., 2007; Rauschmayer et al., 2008). Although the difference between groups was not significant, gillnet fishermen were slightly more positive toward population control than set net fishermen. In addition, the consensus about population control among gillnet fishermen was clearly higher than for set net fishermen. Gillnet fishermen suffer higher damage from their interaction with SSL (Japan Fisheries Research and Education Agency, 2024), explaining their stronger tendency to approve population control. A study comparing the impression of fishermen using trap nets and trawls in Scotland also found that fishermen using trap nets preferred more intensive population control than fishermen using trawls, emphasizing that the damage severity affects the demand for culls (Moore, 2003). In Japan, most of the efforts dedicated to fisheries-SSL conflict mitigation lie in population control (Matsuda et al., 2015). This lack of alternatives, especially for gillnet fishermen, partially explains the current position of fishermen concerning population control despite a relatively neutral view about the ecological role of SSL and differences in tolerance discussed below. Population control is not the only lethal method used in fishery-pinniped conflict. Target removal, shooting individuals who came near the nets, rather than randomly culling, has also been used as a mitigation tool. Several studies reported that it was more effective than population control as it is more likely to remove individuals specialized in feeding from the nets (Lehtonen and Suuronen, 2010; Graham et al., 2011; Königson et al., 2013). As the idea of targeting these specialized individuals has been mentioned during some interviews, this might be a possible alternative to population control.

Both gillnet and set net fishermen clearly voiced the necessity to develop other measures, as an alternative or in addition to population control. Attempts to find alternative damage-preventing solutions such as acoustic deterrence (Iida et al., 2006) or barriers for set nets (Sasakawa, 1989) have been investigated in the past, but without convincing results. Acoustic devices showed promising results in some places, in particular when used as an additional tool to other methods (Fjälling et al., 2006; Harris et al., 2014; Vetemaa et al., 2021), but they have also been criticized elsewhere for not being effective in the long term due to the quick habituation of pinnipeds and being harmful to pinnipeds or other marine mammals (Westerberg et al., 2006; Findlay et al., 2022; Lehtonen et al., 2022). The most promising non-lethal method has been the introduction of a reinforced gillnet in the Sea of Japan (Isono et al., 2013). This has been implemented by some fishermen since 2014. The nets are constructed by sandwiching regular netting fabric between coarse netting made of strong fibers. Although the gaps in fishing capacity and handling have been greatly reduced, the high cost remains a problem until the end, and public subsidies are essential for their introduction (Isono et al., 2013).

Fishermen were not entirely convinced that damage compensation would help to tolerate the current damage level, as relying on compensation is not considered valid for business, which is similar to the opinion of fishermen in Sweden (Waldo et al., 2020). The need to run a business and practice fishing activity in good conditions is also reflected in the answers to the question of good catch. When the damage to their fishing gear is high, they struggle to do their job even if the catch brings a lot of money. The interviews also revealed some concerns that they would lose their identity as a fisherman if they heavily relied on subsidies, as shown in a study of (Cleary, 2021), who interviewed fishermen about the conflict with seals in the Baltic Sea. However, compensation can be effective if the damage is not too extensive like with the Mediterranean Monk seals (Monachus monachus) in Turkey and Greece (Güçlüsoy, 2008; Panagopoulou et al., 2017), or a means to shift the perception of a predator from a nuisance to a natural hazard (Varjopuro, 2011). However, this measure is often viewed as a short-term solution and not a replacement for other damage preventing tools (Varjopuro, 2011; Cummings et al., 2019; Johansson and Waldo, 2021).

4.2 Perceived role of SSL

Gillnet and set net fishermen showed a contradicting perception of SSL ecological role as they acknowledged both the benefits and the risks of SSL presence in the area. This suggests that fishermen make an important difference between enjoying the value of the presence of sea lions in the area and the struggle caused by the negative interaction they experience. In their study, Ramos et al. (2023) also found a mixed perception of sea lions by fishermen stating that they “find it beautiful to witness the sea lions in their moments of rest in the protected area and on other rocky substrates of the coast, because at this moment the animals do not interfere in the fisheries” (section 4, p 7) but have opposite opinions regarding the interaction with fisheries. The potential for conflict for set net fishermen concerning the ecological risk was high (0.58). The main fish target and the damages differ considerably between the set net fisheries in the Sea of Okhotsk and the ones in the southern part of the study area (Japan Fisheries Research and Education Agency, 2024). This could explain the difference in perception within the set net group. Further studies will be needed to explore the difference between locations. Nevertheless, the mixed perception did not differ between groups. However, a few fishermen in Sarufutsu (Figure 1) and in the southern part of the study area did not think that the presence of SSL meant that the ecosystem was healthy. At the Benten-jima haulout site, near Sarufutsu, there has been a dramatic increase in SSL (Goto et al., 2022) and, in the southern part, SSL has been absent for years before recently appearing in the area. This suggests that the comparison to the past situation can influence the perception of the ecological role of SSL, which is known as the shifting baseline syndrome (Pauly, 1995). This shows that the perception of fishermen is directly affected by changes in SSL distribution.

In our study, even though fishermen associate SSL with a healthy ecosystem, they approved of population control regardless of the fishing technique. This is contrasting with the findings of previous studies on the influence of perceived ecological role of a predator on fishermen’s attitude toward lethal management (Cummings et al., 2019; Jackman et al., 2024). In their study, Jackman et al. (2024) found that fishermen considered seals to be more a risk than a benefit for the ecosystem and were more accepting of lethal management. Similarly, a study in Australia found that 46% of the commercial fishermen did not view sea lions as an essential part of a healthy ecosystem and were more likely to approve of lethal management (Cummings et al., 2019). The mixed perception found in our study is therefore unexpected and might be linked to the different perception of Japanese people for nature compared to Western countries. Indeed, the concept of Satoumi defined as “a coastal area with high productivity and biodiversity due to human interaction” (Yanagi, 2006), emphasizes the importance of the interaction between humans and their natural environment. Though recently conceptualized, it is anchored in the Japanese culture as demonstrated in (Mizuta and Vlachopoulou, 2017; Uehara et al., 2019). Through this lens, considering a predator as a sign of a healthy environment and as a risk for human activity, is not mutually exclusive. Our findings suggest that, in the Japanese context, the perceived role of SSL has only a little influence on the attitude of fishermen toward lethal management.

4.3 Different tolerance toward SSL between the two groups of fishing gears

We found that gillnet fishermen were less tolerant of SSL compared to set net fishermen. The interaction with SSL impacted the livelihood of both fishermen groups. However, damage from SSL is thought to be heavier on gillnet livelihood, due to the extensive damage on this fishery and their family-based system. This might influence their stronger negative attitude toward SSL who might be viewed as a direct threat to their livelihood, as fishing is their only source of income (Pont et al., 2016). In contrast, a study in India found that positive attitude toward Irrawaddy dolphin (Orcaella brevirostris) was associated with increased income and catch from this interaction (D’Lima et al., 2013). Despite this difference in tolerance toward SSL, we found no difference in attitudes toward the mitigation measures. This contrasts with the findings of several studies investigating the relation between attitude towards a predator and approval of lethal management. Ramos et al. (2023) found that a negative attitude was linked to greater approval of lethal management of South American sea lions (Otaria flavescens). Similarly, Jackman et al. (2024) also found a link between negative attitudes toward seal and higher approval of the use of lethal methods. However, Cummings et al. (2019) concluded that personal experience rather than attitude toward the fur seals influenced preferences for mitigation methods. In our study, all fishermen experienced negative interactions with SSL. Still, due to the difference in fishing technique, the level of interaction as well as the impact of these interactions on their livelihood was not the same between the two groups. Therefore, despite contrasting attitudes toward SSL, they agreed on the mitigation measures.

4.4 Fishermen-government relationship

From the interviews, it became clear that the conflict between SSL and fishermen is included in the broader context of fishermen’s livelihood and the harshness of the fishing profession, especially for gillnet fishermen. Fishermen want to practice fishing as well as being able to promise an acceptable future for their successors. Currently, they are struggling to do both. Therefore, they voiced the need for something to be done and better communication with the government. The lack of communication between fishermen and the government, and their need to be listened are not separate issues (Karamanlidis et al., 2020; Waldo et al., 2020). There is also a need for empowerment and inclusion of fishermen in conversations about the fishing system and resolving the conflict with SSL. An issue often raised in studies on the human dimension of wildlife conflict is the lack of trust between fishing communities and authorities that could undermine the possibilities of collaboration (Tonder and Jurvelius, 2004; Matsuda et al., 2015; Waldo et al., 2020). In this study, the lack of trust relies on the perceived minimization of their issues and lack of communication from the government. Such a situation also occurred in eastern Hokkaido when the government could not fulfil its promise to fishermen to reduce the harbor seal (Phoca vitulina) population and lost the trust of the fishing community (Matsuda et al., 2015). Appropriate communication and collaboration between the government and fisheries could prevent such an event by prioritizing measures suitable for all stakeholders. This is even more important when there are different perceptions, needs and perspectives represented among a same group of stakeholders. Therefore, including fishermen in the solution-making process might be well received by the Japanese fishing communities. Opening the conversation between fishermen, government and the scientific community has recently been recognized as necessary and effective for fisheries-pinniped conflict management and can help the population to have a better perception of the predator species (Sakurai et al., 2020; Bogomolni et al., 2021; Trukhanova et al., 2021). In their study on cormorant (Phalacrocorax carbo) and sea otter (Lutra lutra) conflict with fisheries and aquaculture, Rauschmayer et al. (2008) concluded that demands for population management increases with the intensity of the conflict. Still, information exchange and inclusion could reduce the costs of the conflict (Rauschmayer et al., 2008). Studies on participatory management also concluded that including the fishermen in the solution-making process helped find solutions useful for fishermen (Bruckmeier and Höj Larsen, 2008). Therefore, fisheries, authorities and scientists in Japan would also benefit from improving communication and knowledge sharing (both scientific and cultural) between stakeholders to enable everyone to work toward sustainable fisheries and SSL management. For example, organizing workshops between scientists and fishermen to share cultural knowledge (Bogomolni et al., 2021; Marchini et al., 2021). During these workshops, discussing ways to revitalize fishermen villages could be beneficial for the empowerment of the local communities especially in the context of depopulation of the rural areas (Frank et al., 2019; Enari, 2021). This would enable the scientific community and authorities to build a trust relationship with the fishing communities, which is an initial step toward finding strategies adapted to their needs and constraints.

5 Conclusion

We interviewed 29 fishermen working on either gillnet or set net fisheries in Hokkaido, Japan. We found that fishermen showed a complex perception of SSL’s ecological role beyond the fact that they cause damage to their catch and gear. As the fishing profession has already been full of struggles, the conflict with SSL only adds to their reality. We also found that the interviewed fishermen are open to trying new measures to find a path toward coexistence.

In Hokkaido, fishing is an essential source of food for the Japanese people, and a source of cultural pride. Thus, protecting fishermen’s livelihood by mitigating the conflict with SSL, and ensuring promising perspectives for their successors is crucial for the future. Studies about the human dimension of marine mammals and small-scale fisheries are scarce (Jog et al., 2022). In Asia, studies on the subject have mainly focused on cetacean conservation (Liu et al., 2016, 2019; Whitty, 2016; Kusuma Mustika et al., 2021). This present study is the first step in understanding the human dimension of the fisheries-SSL conflict in Japan. Given the limited number of interviewees, some reservations about whether they represented the set net and gillnet fishing industry must be made. Even though we gathered opinions in villages covering the whole range of SSL presence in Hokkaido, it has been difficult to get the cooperation of fishermen. Thus, we cannot ignore the fact that the ones who agreed to participate in our study might have similar opinions they needed to express. Nevertheless, this points the way forward for future research on the human dimension of wildlife conflict. Rather than focusing solely on the ecology of the animal involved in the conflict, our study included ecological knowledge of fishermen and provide an understanding of the circumstances surrounding wildlife damage. Now that the door is open, further studies should involve more fishermen and include themes that could not be addressed during this study due to the novelty of the approach with the fishermen. In this rapidly changing world, especially in Japan, with reduced fishing resources, aging population and rural exodus, the conflict with terrestrial and marine wildlife will likely intensify. Therefore, investing effort and working together to find mitigation strategies adapted to the majority’s needs will be the key to coexistence.

Statements

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

Ethical approval was not required for the studies involving humans because The participants were given a short explanation of the content of the interview, use of collected data and respect for anonymity. They were informed that they could skip any question or resign from the interview at any time and were asked to allow the interview to be audio-recorded. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. Written informed consent for participation was not required from the participants or the participants’ legal guardians/next of kin in accordance with the national legislation and institutional requirements because Oral consent was requested at the beginning of every interview. A copy of the cover page of the interview with description provided to the fishermen before the interview is included in the Supplementary Material (S2).

Author contributions

FB: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. NA: Data curation, Investigation, Writing – review & editing. MJ: Investigation, Writing – review & editing. ST: Methodology, Writing – review & editing. OY: Conceptualization, Methodology, Supervision, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. This study was supported by Hokkaido University Doctoral Fellowship, JST SPRING Grant Number JPMJSP2119. This study was also partly funded by the Fishing Industry/Communities Promotion Organization.

Acknowledgments

We would like to warmly thank all the fishermen who agreed to participate in the interviews. We would also like to thank the fisheries cooperatives of all the visited villages, which allowed and arranged these interviews. We are also grateful to Drs. K. Hattori, T. Horimoto, T. Isono, Y. Kobayashi, A. Wada and Y. Watanuki for their valuable help in this study. We thank K. Ito and E. Ozasa who helped with the data collection and handling and Dr. M. Otsuki who provided valuable comments on the manuscript. We are grateful to the reviewers and the editor for their comments which significantly improved the manuscript.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fmars.2025.1716630/full#supplementary-material

References

1

Adger W. N. Quinn T. Lorenzoni I. Murphy C. Sweeney J. (2013). Changing social contracts in climate-change adaptation. Nat. Clim Chang3, 330–333. doi: 10.1038/nclimate1751

2

Bogomolni A. Nichols O. C. Allen D. (2021). A community science approach to conservation challenges posed by rebounding marine mammal populations: seal-fishery interactions in new england. Front. Conserv. Sci.2. doi: 10.3389/fcosc.2021.696535

3

Bruckmeier K. Höj Larsen C. (2008). Swedish coastal fisheries-From conflict mitigation to participatory management. Mar. Policy32, 201–211. doi: 10.1016/j.marpol.2007.09.005

4

Burkanov V. N. Loughlin T. R. (2005). Distribution and abundance of steller sea lions, eumetopias jubatus, on the asian coast 1720’s–2005. Mar. Fisheries Review67, 1–62.

5

Burnard P. Gill P. Stewart K. Treasure E. Chadwick B. (2008). Analysing and presenting qualitative data. Br. Dent. J.204, 429–432. doi: 10.1038/sj.bdj.2008.292

6

Butler J. R. A. Young J. C. McMyn I. A. G. Leyshon B. Graham I. M. Walker I. et al . (2015). Evaluating adaptive co-management as conservation conflict resolution: Learning from seals and salmon. J. Environ. Manage160, 212–225. doi: 10.1016/j.jenvman.2015.06.019

7

Calamnius L. Lundin M. Fjälling A. Königson S. (2018). Pontoon trap for salmon and trout equipped with a seal exclusion device catches larger salmons. PloS One13, 1–13. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0201164

8

Cleary C. (2021). “Alive with seals”: seal-fishery conflict and the conservation conversation in Ireland. Irish Journal of Anthropology (Cork: University College Cork) 24, 73–91.

9

Cronbach L. (1951). Coefficient alpha and the internal structure of tests. Psychometrika16, 297–334. doi: 10.1007/BF02310555

10

Cummings C. R. Lea M. A. Lyle J. M. (2019). Fur seals and fisheries in Tasmania: an integrated case study of human-wildlife conflict and coexistence. Biol. Conserv.236, 532–542. doi: 10.1016/j.biocon.2019.01.029

11

D’Lima C. Marsh H. Hamann M. Sinha A. Arthur R. (2013). Positive interactions between irrawaddy dolphins and artisanal fishers in the chilika lagoon of eastern India are driven by ecology, socioeconomics, and culture. Ambio43, 614–624.

12

Dickman A. J. (2010). Complexities of conflict: The importance of considering social factors for effectively resolving human-wildlife conflict. Anim. Conserv.13, 458–466. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-1795.2010.00368.x

13

Enari H. (2021). Human-macaque conflicts in shrinking communities: Recent achievements and challenges in problem solving in modern Japan. Mammal Study46, 115–130. doi: 10.3106/ms2019-0056

14

Findlay C. R. Hastie G. D. Farcas A. Merchant N. D. Risch D. Wilson B. (2022). Exposure of individual harbour seals (Phoca vitulina) and waters surrounding protected habitats to acoustic deterrent noise from aquaculture. Aquat Conserv.32, 766–780. doi: 10.1002/aqc.3800

15

Fjälling A. Wahlberg M. Westerberg H. (2006). Acoustic harassment devices reduce seal interaction in the Baltic salmon-trap, net fishery. ICES J. Mar. Sci.63, 1751–1758. doi: 10.1016/j.icesjms.2006.06.015

16

Frank B. Glikmann J. A. Silvio M. (2019). “ Human-wildlife interactions: turning conflict into coexistence,”. Eds. FrankB.GlickmanJ. A.MarchiniS. ( Cambridge University Press, Cambridge).

17

Goto Y. Isono T. Ikuta S. Burkanov V. (2022). Origin and Abundance of Steller Sea Lions (Eumetopias jubatus) in Winter Haulout at Benten-Jima Rock Off Cape Soya, Hokkaido, Japan between 2012-2017. Mammal Study47, 87–101. doi: 10.3106/ms2020-0029

18

Goto Y. Wada A. Hoshino N. Takashima T. Mitsuhashi M. Hattori K. et al . (2017). Diets of Steller sea lions off the coast of Hokkaido, Japan: An inter-decadal and geographic comparison. Mar. Ecol.38, 1–22. doi: 10.1111/maec.12477

19

Götz T. Janik V. M. (2013). Acoustic deterrent devices to prevent pinniped depredation: Efficiency, conservation concerns and possible solutions. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser.492, 285–302. doi: 10.3354/meps10482

20

Graham I. M. Harris R. N. Middlemas S. J. (2011). Seals, salmon and stakeholders: Integrating knowledge to reduce biodiversity conflict. Anim. Conserv.14, 604–607. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-1795.2011.00513.x

21

Gruber C. P. Orbach M. (2014). Social, Economic, and Spatial Perceptions of Gray Seal (Halichoerus grypus) Interactions with Commercial Fisheries in Cape Cod, MA (Durham, NC: Duke University).

22

Güçlüsoy H. (2008). Damage by monk seals to gear of the artisanal fishery in the Foça Monk Seal Pilot Conservation Area, Turkey. Fish Res.90, 70–77. doi: 10.1016/j.fishres.2007.09.012

23

Guerra A. S. (2019). Wolves of the Sea: Managing human-wildlife conflict in an increasingly tense ocean. Mar. Policy99, 369–373. doi: 10.1016/j.marpol.2018.11.002

24

Harris R. N. Harris C. M. Duck C. D. Boyd I. L. (2014). The effectiveness of a seal scarer at a wild salmon net fishery. ICES J. Mar. Sci.71, 1913–1920. doi: 10.1093/icesjms/fst216

25

Hokkaido Government (2024a). 2018 fisheries census results (Hokkaido) (Confirmed values) - marine fisheries survey and fishery management survey. Available online at: https://www.pref.hokkaido.lg.jp/ss/tuk/067cfs/18kk.html (Accessed July 29, 2025).

26

Hokkaido Government (2024b). Countermeasures against marine mammal damage. Available online at: https://www.pref.hokkaido.lg.jp/sr/sky/186211.html (Accessed August 1, 2025).

27

Iida K. Park T.-G. Mukai T. Kotani S. (2006). “ Avoidance of artificial stimuli by the steller sea lion,” in Sea lions of the world: conservation and research in the 21st century. Eds. TritesA. W.AtkinsonS. K.DeMasterD. P.FritzL. W.GelattT. S.ReaL. D.et al ( Alaska Sea Grant College Program, University of Alaska Fairbanks, Anchorage), 535–548.

28

Iriarte V. Arkhipkin A. Blake D. (2020). Implementation of exclusion devices to mitigate seal (Arctocephalus australis, Otaria flavescens) incidental mortalities during bottom-trawling in the Falkland Islands (Southwest Atlantic). Fish Res.227, 1–12. doi: 10.1016/j.fishres.2020.105537

29

Isono T. Niimura K. Hattori K. Yamamura O. (2013). Development of reinforced bottom gillnets for mitigation of damages from steller sea lion eumetopias jubatus. Journal of Fisheries Technology (Yokohama: Japan Fisheries Research and Education Agency) 6, 17–26.

30

Jackman J. L. Vaske J. J. Dowling-Guyer S. Bratton R. Bogomolni A. Wood S. A. (2024). Seals and the marine ecosystem: attitudes, ecological benefits/risks and lethal management views. Hum. Dimensions Wildlife29, 142–158. doi: 10.1080/10871209.2023.2212686

31

Japan Fisheries Research and Education Agency (2024). Summary of results of the Steller sea lion resource survey. Available online at: https://www.fra.go.jp/shigen/fisheries_resources/result/todo.html (Accessed July 15, 2025).

32

Jog K. Sutaria D. Diedrich A. Grech A. Marsh H. (2022). Marine mammal interactions with fisheries: review of research and management trends across commercial and small-scale fisheries. Front. Mar. Sci.9. doi: 10.3389/fmars.2022.758013

33

Johansson M. Waldo Å. (2021). Local people’s appraisal of the fishery-seal situation in traditional fishing villages on the baltic sea coast in southeast Sweden. Soc. Nat. Resour34, 271–290. doi: 10.1080/08941920.2020.1809756

34

Karamanlidis A. A. Adamantopoulou S. Kallianiotis A. A. Tounta E. Dendrinos P. (2020). An interview-based approach assessing interactions between seals and small-scale fisheries informs the conservation strategy of the endangered Mediterranean monk seal. Aquat Conserv.30, 928–936. doi: 10.1002/aqc.3307

35

Königson S. Fjälling A. Berglind M. Lunneryd S. G. (2013). Male gray seals specialize in raiding salmon traps. Fish Res.148, 117–123. doi: 10.1016/j.fishres.2013.07.014

36

Königson S. J. Fredriksson R. E. Lunneryd S. G. Strömberg P. Bergström U. M. (2015). Cod pots in a Baltic fishery: Are they efficient and what affects their efficiency? ICES J. Mar. Sci.72, 1545–1554. doi: 10.1093/icesjms/fsu230

37

Königson S. Hemmingsson M. Lunneryd S. G. Lundström K. (2007). Seals and fyke nets: An investigation of the problem and its possible solution. Mar. Biol. Res.3, 29–36. doi: 10.1080/17451000601072596

38

Kusuma Mustika P. L. Wonneberger E. Erzini K. Pasisingi N. (2021). Marine megafauna bycatch in artisanal fisheries in Gorontalo, northern Sulawesi (Indonesia): An assessment based on fisher interviews. Ocean Coast. Manag208, 1–11. doi: 10.1016/j.ocecoaman.2021.105606

39

Lehtonen E. Lehmonen R. Kostensalo J. Kurkilahti M. Suuronen P. (2022). Feasibility and effectiveness of seal deterrent in coastal trap-net fishing – development of a novel mobile deterrent. Fish Res.252, 1–6. doi: 10.1016/j.fishres.2022.106328

40

Lehtonen E. Suuronen P. (2010). Live-capture of grey seals in a modified salmon trap. Fish Res.102, 214–216. doi: 10.1016/j.fishres.2009.10.007

41

Liu M. Lin M. Turvey S. T. Li S. (2019). Fishers’ experiences and perceptions of marine mammals in the South China Sea: Insights for improving community-based conservation. Aquat Conserv.29, 809–819. doi: 10.1002/aqc.3073

42

Liu T. K. Wang Y. C. Chuang L. Z. H. Chen C. H. (2016). Conservation of the eastern Taiwan strait chinese white dolphin (Sousa chinensis): fishers’ Perspectives and management implications. PloS One11, 1–15. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0161321

43

Manfredo M. Vaske J. Teel T. (2003). The potential for conflict index: A graphic approach to practical significance of human dimensions research. Hum. Dimensions Wildlife3, 219–228. doi: 10.1080/10871200304310

44

Marchini S. Ferraz K. M. P. M. B. Foster V. Reginato T. Kotz A. Barros Y. et al . (2021). Planning for human-wildlife coexistence: conceptual framework, workshop process, and a model for transdisciplinary collaboration. Front. Conserv. Sci.2. doi: 10.3389/fcosc.2021.752953

45

Matsuda H. Yamamura O. Kitakado T. Kobayashi Y. Kobayashi M. Hattori K. et al . (2015). Beyond dichotomy in the protection and management of marine mammals in Japan. Therya6, 283–296. doi: 10.12933/therya-15-235

46

Mizuta D. D. Vlachopoulou E. I. (2017). Satoumi concept illustrated by sustainable bottom-up initiatives of Japanese Fisheries Cooperative Associations. Mar. Policy78, 143–149. doi: 10.1016/j.marpol.2017.01.020

47

Moore P. G. (2003). Seals and fisheries in the Clyde Sea area (Scotland): Traditional knowledge informs science. Fish Res.63, 51–61. doi: 10.1016/s0165-7836(03)00003-1

48

Nelson M. L. Gilbert J. R. Boyle K. J. (2006). The influence of siting and deterrence methods on seal predation at Atlantic salmon (Salmo salar) farms in Maine 2001-2003. Can. J. Fisheries Aquat. Sci.63, 1710–1721. doi: 10.1139/F06-067

49

Panagopoulou A. Meletis Z. A. Margaritoulis D. Spotila J. R. (2017). Caught in the same net? Small-scale fishermen’s perceptions of fisheries interactions with sea turtles and other protected species. Front. Mar. Sci.4. doi: 10.3389/fmars.2017.00180

50

Pauly D. (1995). Anecdotes and the shifting baseline syndrome of fisheries. Trends Ecol. Evol.10, 430. doi: 10.1016/S0169-5347(00)89171-5

51

Pont A. C. Marchini S. Engel M. T. MaChado R. Ott P. H. Crespo E. A. et al . (2016). The human dimension of the conflict between fishermen and South American sea lions in southern Brazil. Hydrobiologia770, 89–104. doi: 10.1007/s10750-015-2576-7

52

Ramos K. L. MaChado R. Zapelini C. de Castilho L. C. Schiavetti A. (2023). Knowledge, attitudes and behavioural intentions of gillnet fishermen towards the South American sea lion in two marine protected areas in southern Brazil. Ocean Coast. Manag242, 1–10. doi: 10.1016/j.ocecoaman.2023.106673

53

Rauschmayer F. Wittmer H. Berghöfer A. (2008). Institutional challenges for resolving conflicts between fisheries and endangered species conservation. Mar. Policy32, 178–188. doi: 10.1016/j.marpol.2007.09.008

54

R Core Team (2024). R: A language and environment for statistical computing (Vienna, Austria: R Foundation for Statistical Computing).

55

Sakurai R. Tsunoda H. Enari H. Siemer W. F. Uehara T. Stedman R. C. (2020). Factors affecting attitudes toward reintroduction of wolves in Japan. Glob Ecol. Conserv.22, 1–10. doi: 10.1016/j.gecco.2020.e01036

56

Sasakawa Y. (1989). The damage of submerged bottom setnets by northern sea lions and its encounter plan (Sapporo, Japan: Hokkaido University).

57

Tavakol M. Dennick R. (2011). Making sense of Cronbach’s alpha. Int. J. Med. Educ.2, 53–55. doi: 10.5116/ijme.4dfb.8dfd

58

Tixier P. Lea M. A. Hindell M. A. Welsford D. Mazé C. Gourguet S. et al . (2021). When large marine predators feed on fisheries catches: Global patterns of the depredation conflict and directions for coexistence. Fish Fisheries22, 31–53. doi: 10.1111/faf.12504

59

Tonder M. Jurvelius J. (2004). Attitudes towards fishery and conservation of the Saimaa ringed seal in Lake Pihlajavesi, Finland. Environ. Conserv.31, 122–129. doi: 10.1017/S0376892904001201

60

Trukhanova I. S. Andrievskaya E. M. Alekseev V. A. (2021). Bycatch in Lake Ladoga Fisheries Remains a Threat to Ladoga Ringed Seal (Pusa hispida ladogensis) Population. Aquat Mamm47, 470–481. doi: 10.1578/am.47.5.2021.470

61

Tsujino H. Nakano H. Motoi T. (2008). Mechanism of currents through the straits of the Japan sea: mean state and seasonal variation. J. Oceanogr64, 141–161. doi: 10.1007/s10872-008-0011-7

62

Uehara T. Hidaka T. Matsuda O. Sakurai R. Yanagi T. Yoshioka T. (2019). Satoumi: Re-connecting people to nature for sustainable use and conservation of coastal zones. People Nat.1, 435–441. doi: 10.1002/pan3.10047

63

Varjopuro R. (2011). Co-existence of seals and fisheries? Adaptation of a coastal fishery for recovery of the Baltic grey seal. Mar. Policy35, 450–456. doi: 10.1016/j.marpol.2010.10.023

64

Vaske J. J. (2019). Survey research and analysis. 2nd (Champaign, IL: Sagamore-Venture).

65

Vaske J. J. Beaman J. Barreto H. Shelby L. (2010). An extension and further validation of the potential for conflict index. Leis Sci.32, 240–254. doi: 10.1080/01490401003712648

66

Vetemaa M. Päädam U. Fjälling A. Rohtla M. Svirgsden R. Taal I. et al . (2021). Seal-induced losses and successful mitigation using acoustic harassment devices in Estonian baltic trap-net fisheries. Proc. Estonian Acad. Sci.70, 207–214. doi: 10.3176/PROC.2021.2.09

67

Waldo Å. Johansson M. Blomquist J. Jansson T. Königson S. Lunneryd S. G. et al . (2020). Local attitudes towards management measures for the co-existence of seals and coastal fishery - A Swedish case study. Mar. Policy118, 1–11. doi: 10.1016/j.marpol.2020.104018

68

Westerberg H. Lunneryd S. Fjälling A. B. Wahlberg M. (2006). Reconciling Fisheries Activities with the Conservation of Seals throughout the Development of New Fishing Gear: A Case Study from the Baltic Fishery–Gray Seal Conflict. Available online at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/236149625 (Accessed April 25, 2022).

69

Whitty T. S. (2016). Multi-methods approach to characterizing the magnitude, impact, and spatial risk of Irrawaddy dolphin (Orcaella brevirostris) bycatch in small-scale fisheries in Malampaya Sound, Philippines. Mar. Mamm Sci.32, 1022–1043. doi: 10.1111/mms.12322

70

Wutich A. Beresford M. Bernard H. R. (2024). Sample sizes for 10 types of qualitative data analysis: an integrative review, empirical guidance, and next steps. Int. J. Qual. Methods23, 1–14. doi: 10.1177/16094069241296206

71

Yanagi T. (2006). Creation of satoumi (Tokyo, Japan: Koseisha-Koseikaku).

Summary

Keywords

pinnipeds, human-wildlife conflict, local attitude, coastal fisheries, interview, set net, gillnet

Citation

Brochut FEC, Abe N, Jimbo M, Tatsuzawa S and Yamamura O (2025) Human dimension of small-scale fisheries and Steller sea lion conflict in Hokkaido coastal water, Japan: exploring perceptions and attitudes between fishermen groups. Front. Mar. Sci. 12:1716630. doi: 10.3389/fmars.2025.1716630

Received

30 September 2025

Revised

10 November 2025

Accepted

17 November 2025

Published

17 December 2025

Volume

12 - 2025

Edited by

Kit Yue Kwan, JiMei University, China

Reviewed by

Takanori Kooriyama, Rakuno Gakuen University, Japan

Lei Zhang, Chinese Academy of Fishery Sciences (CAFS), China

Updates

Copyright

© 2025 Brochut, Abe, Jimbo, Tatsuzawa and Yamamura.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Fleur E. C. Brochut, brochut.fleur@elms.hokudai.ac.jp

† Present address: Nanami Abe, Kodansha Co., Ltd., Bunkyo, Tokyo, Japan

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.