Abstract

Background:

Seaweeds are typically considered a part of traditional diets in several Asian countries and have recently acquired significant attention owing to the therapeutic potential of their bioactive compounds. sulfated polysaccharides, polyphenols, and proteins are the most common seaweed-derived substances with pronounced antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties. However, the analgesic effects of these compounds have not yet been well established.

Methods:

An extensive systematic search of four databases, including PubMed, Scopus, Web of Science, and the Cochrane Library, was conducted until May 2025. Preclinical and clinical studies evaluating the analgesic effects of seaweed-derived compounds were included in this review.

Results:

Preclinical studies have shown significant antinociceptive effects of various seaweed-derived substances. Sulfated polysaccharides demonstrated a dose-dependent peripheral analgesic effect, whereas central analgesic effects appeared at the highest doses. Phlorotannin-rich polyphenols also showed substantial peripheral analgesic effects, reaching 90.16% inhibition in the writhing test, and prominent central analgesic responses lasting 120 min. Furthermore, lecithin extracts exhibited significant peripheral antinociceptive effects with favorable safety profiles. Evidence from human studies is limited to four small trials (total n = 91). In one study (n = 30) on mild knee osteoarthritis, a multi-mineral seaweed formulation (Aquamin+) produced greater pain reduction than glucosamine. Risk of bias assessment showed an overall low-to-moderate quality across the included studies.

Conclusion:

Seaweed extracts exhibit promising peripheral and central antinociceptive effects. However clinical data remain preliminary and heterogenous. Further research is warranted to standardize the extracts, explore chronic pain applications, and validate the findings in large-scale human trials.

Clinical trial registration:

https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/prospero/, identifier systematic review is registered with PROSPERO CRD420251078862.

1 Introduction

The Global Burden of Disease 2021 study estimated that chronic pain affects 1.5 billion people globally and contributes to approximately 5% of the years lived with a disability (GBD 2021 Diseases and Injuries Collaborators, 2024). It is a major contributor to lower economic output and lower standards of living (Shetty et al., 2024). The search for chemicals produced by marine algae as possible analgesics is in line with the World Health Organization’s 2021–2030 Pain Management Framework (World Health Organization, 2023), which highlights the pressing need for safe, reasonably priced, and non-opioid alternatives. Seaweeds, or marine macroalgae, have been widely utilized in traditional diets and medicinal practices across Asia for many decades, particularly in China, Japan, and South Korea (Paiva et al., 2017). Recently, the use of edible seaweeds as functional foods has expanded, particularly in France, the United States, and South America (Bocanegra et al., 2009; Faggio et al., 2016; Paiva et al., 2017). Seaweeds contain high concentrations of polysaccharides, polyphenols, fucoidan, and other phytochemicals. These unique marine-derived compounds possess notable antioxidant, antiviral, and anti-inflammatory properties (Jung et al., 2013; Leandro et al., 2020; Lin et al., 2018; Myers, 2010; Sathivel et al., 2013; Walsh et al., 2019). Seaweed does not require arable land or freshwater, and its favorable safety profile further emphasizes its potential as an alternative medicinal therapy for various diseases (Meinita et al., 2022).The incorporation of seaweed into traditional diets has been associated with lower estimates of chronic diseases, including cancer, obesity, arthritis, and cardiovascular disorders (Brown et al., 2014; Iso, 2011; Iso et al., 2007; Kim et al., 2009; Mary et al., 2012; Park et al., 2021).The growing evidence of its safety and edible and functional properties (Lomartire and Gonçalves, 2022) has led to increased interest in the therapeutic benefits of seaweed, particularly in pain management. Oxidative stress plays a significant role in many chronic inflammatory and neurodegenerative diseases linked to pain (Teleanu et al., 2022). The excessive generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) can harm cells and tissues, which can worsen inflammation and pain (Checa and Aran, 2020). Natural antioxidants have gained attention as potential therapeutic options. Algae produce a variety of bioactive compounds with antioxidant capabilities (Guiry, 2024).

These compounds include polyphenols, carotenoids, vitamins, minerals, and sulfated polysaccharides, which are especially abundant in marine species. This antioxidant effect helps to minimize cellular damage and inflammation, which is particularly important in managing conditions related to chronic pain. Consequently, marine algae are considered valuable resources for developing new antioxidant-based treatments. Although the anti-inflammatory and antioxidant effects of seaweeds have been well documented, their efficacy in pain management remains undetermined and, at times, conflicting. Preliminary results suggest a promising analgesic potential, indicating that future research should focus on evaluating the effects of specific algal extracts or isolated compounds within the framework of clearly defined pain mechanisms (Belda-Antolí et al., 2025).

By adopting a targeted, evidence-based approach that considers the underlying aetiopathogenesis of different pain types, algal compounds can be more effectively integrated into multimodal pain management strategies, ultimately contributing to improved clinical outcomes for patients. The effects of seaweed compounds on pain appear to be multifactorial (Sanjeewa et al., 2021). Polyphenols (such as phlorotannins) interact with GABAergic and TRP ion channels to influence nociceptive transmission (Kwon et al., 2023), lectins control cytokine-mediated inflammatory cascades (e.g., TNF-α, IL-1β) (De Queiroz et al., 2015), which are linked to central sensitization, and sulfated polysaccharides modulate prostaglandin and nitric oxide signaling (Manlusoc et al., 2019). Their demonstrated analgesic effects have biological plausibility owing to these molecular linkages (Belda-Antolí et al., 2025). This systematic review aims to summarize the available preclinical and clinical evidence regarding the analgesic effects of different seaweed-derived compounds.

2 Methods

We followed the PRISMA 2020 standards for reporting systematic reviews when conducting this study (Page et al., 2021). We prospectively registered the protocol of this study in the PROSPERO database with the following ID: CRD420251078862.

2.1 Search strategy and source of information

We conducted a comprehensive literature search across four databases (Web of Science, Cochrane Library, Scopus, and PubMed) from inception until April 2025. We developed a thorough search approach to identify research assessing the effects of seaweed or seaweed-derived substances on pain outcomes. We used Boolean operators to combine keywords associated with seaweed (marine algae, seaweed extract, phlorotannin, and fucoidan) and pain (pain, analgesia, nociception, writhing, and thermal latency). No restrictions were applied to language, publication date, or study location. Supplementary Table 1 provides specific search terms and results for each database.

2.2 Eligibility criteria

Inclusion criteria:

-

Studies involving human and animal participants that evaluated the analgesic or pain-relieving effects of seaweed or biologically active compounds derived from seaweed were considered.

-

Regardless of the species, extraction methods, dosage, mode of administration, or duration of therapy, seaweed extracts, whole seaweed, and isolated bioactive components were deemed eligible interventions.

-

Studies that assessed pain outcomes, which could incorporate behavioral pain tests (e.g., the formalin test, hot-plate latency, tail-flick, or acetic acid-induced writhing) as well as molecular biomarkers of nociception (such as PGE2, CGRP, TNF-α, IL-1β, or pain-related leukocyte migration).

Exclusion criteria:

-

Studies that exclusively evaluated outcomes other than pain, such as inflammation, metabolic metrics, oxidative stress, or general toxicity, without assessing endpoints related to pain.

-

Reviews, editorials, and research that lacked original data.

2.3 Study selection

We used the EndNote™ reference manager (from Clarivate) to import all the retrieved citations. After duplicate removal, they underwent a two-round screening. Two researchers independently examined the abstracts and titles to identify potentially eligible studies using the Rayyan screening tool (Ouzzani et al., 2016). Subsequently, studies retrieved from the first round underwent full-text screening. Any disagreements regarding inclusion were discussed, and if no agreement could be achieved, a third reviewer was consulted. The final collection of studies was carefully chosen based on the established eligibility criteria of this review.

2.4 Data extraction

Two authors independently extracted the data using an adapted extraction sheet. The extracted data incorporated the key findings, population or species details (e.g. human participants, mice, or rats), experimental design (for example, RCT, animal trial), number of participants, type of seaweed or bioactive substances used, dosage, route and duration of administration, pain induction model, form of pain outcome measured, and study characteristics (author, year, and country). Common animal research models include chemically induced writhing, thermal nociception, and formalin tests. The chemicals extracted from red, brown, and green seaweeds included lectins, fucoidans, heterofucans, phenol tannins, and other polysaccharides, which varied throughout the studies. Various dosages and delivery methods have been used, including intravenous, intraperitoneal, and oral methods. Both behavioral pain responses and, when applicable, molecular markers were included in the results section.

2.5 Risk of bias assessment

For randomized controlled trials involving human participants, we used the Cochrane Risk of Bias 2.0 (RoB 2) tool (Sterne et al., 2019), which evaluates potential bias across five domains: randomization process, deviations from intended interventions, missing outcome data, measurement of outcomes, and selection of the reported result (Sterne et al., 2019). For animal studies, we used the SYRCLE Risk of Bias tool, which is an adaptation of the original Cochrane tool for preclinical models that addresses sequence generation, allocation concealment, baseline variables, random housing, blinding, incomplete outcome data, and other sources of bias (Hooijmans et al., 2014). Two reviewers independently evaluated the risk of bias in each study, and disagreements were settled through discussion or adjudication by a third reviewer, as needed.

2.6 Evidence synthesis

Quantitative synthesis via meta-analysis was deemed unfeasible due to substantial variations between studies in terms of species, pain models, seaweed types, chemicals investigated, study design, and outcome measurement. Therefore, we synthesized the evidence narratively. We compared the principal results across models and study contexts, and studies were categorized by compound class and seaweed species. Where feasible, we discussed plausible modes of action as well as trends in the consistency or variability of the included studies.

3 Results

3.1 Literature search and study characteristics

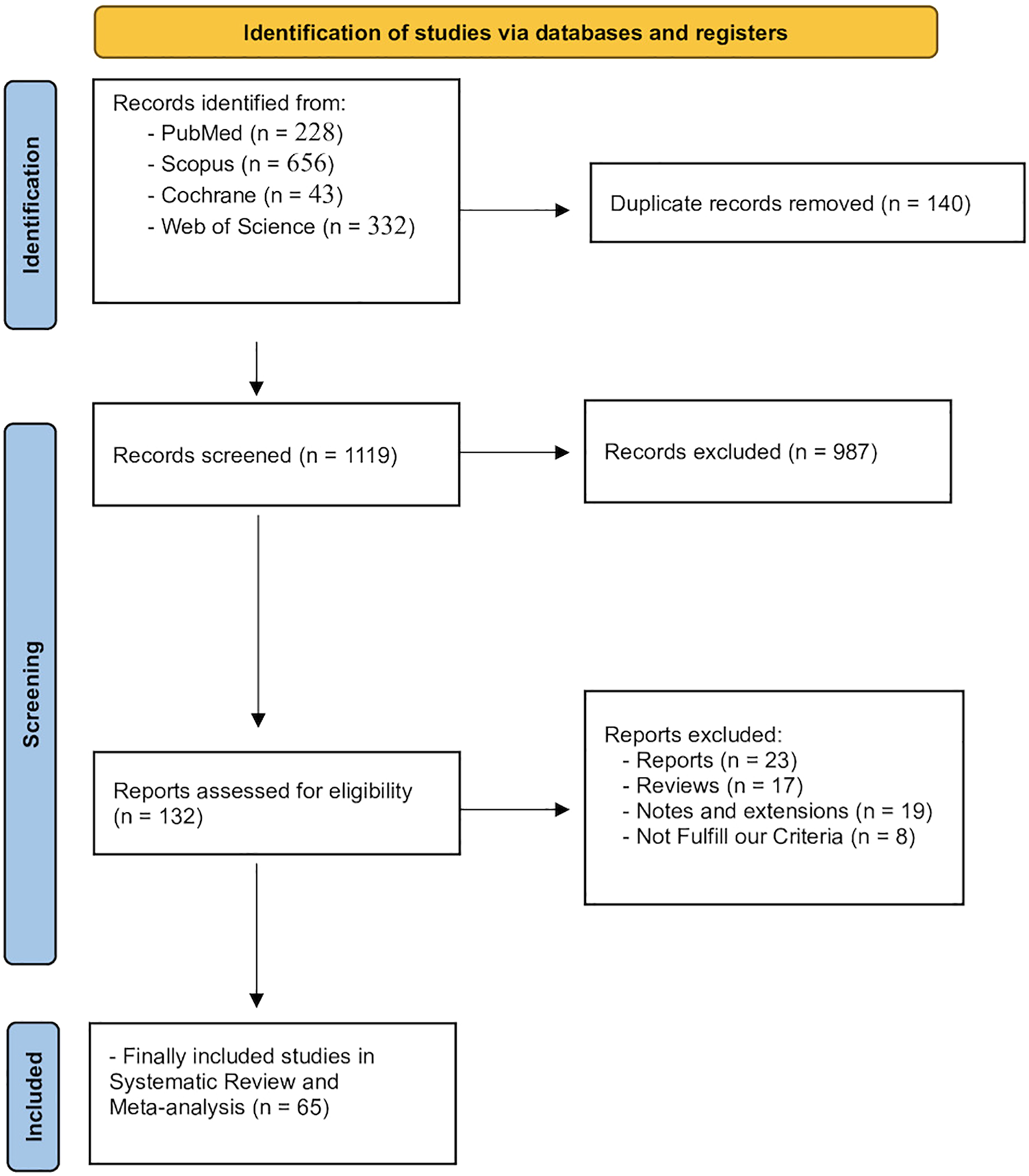

Our initial electronic search of four databases retrieved 1259 records, 140 of which were eliminated as duplicates, and 1119 were evaluated through the title and abstract screening phase. After the rigorous application of our inclusion criteria, 987 articles were excluded, and 132 were retrieved for the full-text screening phase. Finally, 65 articles were included in this systematic review (Abdelhamid et al., 2018; Abreu et al., 2016; Albuquerque et al., 2013; Anca et al., 1993; Aragao et al., 2016; Araújo et al., 2017; Ardizzone et al., 2023; Assreuy et al., 2008; Bhatia et al., 2019, Bhatia et al, 2015; Bitencourt et al., 2008; Brito Da Matta et al., 2011; Carneiro et al., 2014; Chatter et al., 2012; Chen et al., 2019; Costa et al., 2020, Costa et al., 2015; Coura et al., 2017, Coura et al., 2012; Da Conceição Rivanor et al., 2014; De Araújo et al., 2016, De Araújo et al., 2016, De Araújo et al., 2011; De Sousa et al., 2013; De Souza et al., 2009; Figueiredo et al., 2010; Frestedt et al., 2009; García Delgado et al., 2013; Guzman et al., 2001; Hassan et al., 2024; Heffernan et al., 2020; Hong et al., 2011; Hu et al., 2014; Jarmkom et al., 2024; Jeon et al., 2019; Joung et al., 2020; Kim et al., 2014; Lee et al., 2023; Mahardani Adam et al., 2021; Matta et al., 2015; Merchant et al., 2000; Moon et al., 2018; Myers, 2010; Neelakandan and Venkatesan, 2016; Oliveira et al., 2020; Pereira et al., 2014; Phull et al., 2017; Quinderé et al., 2013; Ramamoorthi et al., 2025; Ribeiro et al., 2014; Rivanor et al., 2018; Rodrigues et al., 2014, Rodrigues et al., 2013, Rodrigues et al., 2012; Samaddar and Koneri, 2019; Santos et al., 2015; Shih et al., 2017; Silva et al., 2010; Souza et al., 2019, Souza et al., 2009; Vaamonde-García et al., 2022; Vanderlei et al., 2010; Vieira et al., 2004; Yegdaneh et al., 2020; Yuvaraj et al., 2013; Yuvaraj, 2017). Figure 1 shows the PRISMA flow diagram of the study selection process.

Figure 1

PRISMA flow diagram of the study selection process.

Most of the included studies were animal-controlled studies using mouse models, while only four were human-controlled studies encompassing 91 individuals. Studies were conducted in various geographical areas, with 37 studies conducted in North and South America, mainly in Brazil and the USA; 20 in Asia; 7 in Europe, and one in Africa. Several types of seaweed species were evaluated, such as Solieria filiformis, Porphyra vietnamensis, Gracilaria cornea, Ulva Lactuca, and Caulerpa cupressoides. SPs, polyphenols, and lectin proteins were the most extracted bioactive compounds. In-depth information regarding the study characteristics is presented in Table 1.

Table 1

| Study ID | Study design | Population/model | Sample size | Country | Seaweed species | Bioactive compounds | Intervention (dose, route, and details if available) | Target condition (osteoporosis, rheumat…, egarthritis…,eg) | Key findings (↓PGE2, ↓paw swelling…….eg) | Conclusion |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Abdelhamid et al, 2018 | An animal randomized controlled study | Swiss mice model Adult Wistar Rats model |

48 | Tunisia |

Cystoseira sedoides

Cladostephus spongeosis Padina pavonica |

Phlorotannin | 50 or 100 mg/kg of phlorotannin fraction of seaweed species. | Pain | ↓ Writhing response. ↑ Hot-plate reaction time. |

Phlorotannin-rich extracts, especially from Cystoseira sedoides (PHT-SED), showed strong peripheral and central antinociceptive effects in mice. |

| Abreu et al, 2016 | Animal-controlled study | Swiss mice model | 6 | Brazil | Red marine alga Solieria filiformis | Lectin | IV injection of 1, 3, or 9 mg/kg S. filiformis lectin | Pain | ↓ Writhing response. ↓ Paw licking time. |

The lectin from S. filiformis exhibits antinociceptive effects primarily through peripheral inhibition of inflammatory pain. It also shows anti-inflammatory activity, possibly by inhibiting serotonin and supporting the heme oxygenase-1 pathway. |

| Mahardani Adam, 2021 | In silico experimental study | NA | NA | Indonesia | Sargassum species | Tannins, terpenoids, and fucoidan | NA | Migrane | ↓ CGRP ↓ TNF-α |

The active substance in Sargassum sp has an inhibitory effect on the occurrence of CGRP and TNF-α in migraine, based on in silico studies. |

| Albuquerque et al, 2013 | Animal-controlled study | Mice model | 5 | Brazil | Dictyota menstrualis | Heterofucan | 20.0 mg/kg for heterohucan | Pain | ↓ Leukocyte migration | This study showed that the heterofucan compound has excellent potential as an antinociceptive agent. |

| Anca et al, 1993 | Animal-controlled study | Mice model | NA | Spain | Himanthalia elongata | Phlorotannins, Fucoidans, Alginates, and Fucoxanthin | 4.5 g of brown aqueous fraction | Pain | ↑ Hot-plate reaction time. | The fraction from himanthalia elongata showed significant analgesic effects on the hot-plate test at all of the assayed doses but not on the writhing test, where only the highest dose showed significant activity. |

| Aragao et al, 2016 | Animal-controlled study | Swiss mice model | NA | Brazil | Red algae Amansia multifida | Phenolic compounds, Galactans, Lectins, and Sulfated polysaccharides | 10 mg kg of ethanolic extract | Pain | ↓ Writhing response. ↑ Tail flick test latency |

In conclusion, EEAm presents antinociceptive, anti-inflammatory, and anticonvulsant effects involving peripheral and central-acting mechanisms in mice. |

| De Araújo et al., 2011 | Animal-controlled study | Swiss mice model | NA | Brazil | Solieria filiformis | Sulfated polysaccharide | (1, 3, or 9 mg/kg) of sulfated polysaccharide. | Pain | ↓ Writhing response. | In this study, we demonstrate the efficacy of sulfated polysaccharides from the red seaweed S. filiformis in experimental models of nociception. Although the exact molecular mechanisms of SP-Sf activity remain unknown, our data demonstrate that the antinociceptive effects of SP-Sf occur via a peripheral mechanism. However, the edematogenic effects of SP-Sf suggest the involvement of prostaglandins, NO, and primary cytokines (IL-1 and TNF-) |

| Aragao, 2016 | Animal-controlled study | Swiss mice model Wister mice model |

6 | Brazil | Ulva lactuca | Polysulfated fraction | (1, 3, or 9 mg/kg; i.v) of polysulfated fraction | Pain | ↓ Writhing response. ↓ Formalin inflammatory response |

The sulfated polysaccharide from Ulva lactuca showed optimal antinociceptive and anti-inflammatory effects at 1 mg/kg, acting via peripheral mechanisms. |

| Araújo et al, 2017 | Animal-controlled study | Wister mice model | 5 animals per group | Brazil | Solieria filiformis | Sulfated polysaccharide | (0.03, 0.3, or 3.0 mg/kg) of sulfated polysaccharide | Temporomandibular joint pain | ↓ Formalin-induced nociception ↓ Serotonin-induced nociception ↑ β-endorphin |

This study suggests that F II has a potential antinociceptive and anti-inflammatory effect in the TMJ mediated by activation of opioid receptors in the subnucleus caudalis and inhibition of the release of inflammatory mediators in the periarticular tissue. |

| Ardizzone et al, 2023 | Animal randomized controlled study | Mice model | 10 animals per group | Italy | Ulva pertusa | NA | 50 and 100 mg/kg by oral gavage. | Colitis | NA | This study offers a novel perspective on the pain-relieving and immunomodulatory properties of Ulva pertusa, potentially mediated through the inhibition of TLR4 and NLRP3 signaling pathways, leading to the modulation of immune-inflammatory responses. These results highlight the potential of natural therapeutic strategies targeting immune mechanisms as a promising advancement in the pharmacological management of ulcerative colitis (UC), with the potential to enhance patients’ quality of life. |

| Assreuy et al, 2008 | Animal-controlled study | Swiss mice model | 10 animals per group | Brazil | Red Algae Champia feldmannii | Sulfated polysaccharide | 0.2, 1, 5, and 25 mg of sulfated polysaccharide | Pain | ↓ Writhing response. | This study has shown that the sulfated polysaccharide from the red marine algae Champia feldmannii possesses interesting anticoagulant, pro-inflammatory, and antinociceptive properties. The potential underlying mechanisms involved in these activities are currently being evaluated and form the basis of an ongoing study |

| Bhatia et al, 2015 | Animal-controlled study | Swiss mice model | 6 animals per group | India | Porphyra vietnamensis | Porphyran Porphyra extract |

250 mg/kg body of Porphyran 250 mg/kg of Porphyra extract |

Pain | ↓ Writhing response. ↑ Hot-plate reaction time. |

The results of this study demonstrated that P. vietnamenis aqueous fraction possesses biological activity that is close to the standards taken for the treatment of peripheral painful |

| Bhatia et al, 2019 | Animal-controlled study | Swiss mice model | 36 | India | Porphyra vietnamensis | Porphyran, Polyphenols, Flavonoids, Mycosporine-like amino acids, and Sulfated polysaccharides | 100 mg/kg of each extract | Pain | ↓ Writhing response. ↑ Hot-plate reaction time. |

This study showed that the acetone fraction of Porphyra showed marked antinociceptive and antioxidant activities; however, pharmacological and chemical investigations are required to identify principal compounds responsible for activities and characterize their respective mechanism(s) for their respective actions. |

| Bitencourt et al, 2008 | Animal-controlled study | Swiss mice model Wister mice model |

NA | Brazil | Hypnea cervicornis | Mucin-binding agglutinin | 10 mg/kg | Pain | ↓ Writhing response ↓ Formalin-induced nociception |

HCA from Hypnea cervicornis exhibits strong peripheral antinociceptive effects, particularly in inflammatory pain models. Its activity is mediated through lectin–carbohydrate interactions, without involvement of central mechanisms. |

| Carneiro et al, 2014 | Animal-controlled study | Swiss mice model | 6 animals per group | Brazil | Caulerpa mexicana | Sulphated Polysaccharides | 10 or 20 mg/kg of sulfated polysaccharides | Pain | ↓ Writhing response ↓ Formalin-induced nociception |

Cm-SPs from Caulerpa mexicana exhibit significant peripheral antinociceptive and anti-inflammatory effects without toxicity. Their action targets histamine-mediated pathways, making them promising candidates for pain and inflammation management. |

| Chatter et al, 2012 | Animal-controlled study | Mice model | NA | France | Laurencia glandulifera | Brominated diterpene | 10 mg/kg of Brominated diterpene | Pain | ↓ Writhing response | This study demonstrated significant analgesic properties for the algal metabolite VLC5, which is able to signal directly to primary afferents, through a mechanism dependent on the activation of opioid receptors. This identifies a new natural compound capable of activating peripheral opioidergic systems, exerting analgesic properties |

| Chen et al, 2019 | Animal-controlled study | Rat model | 50 | Taiwan | Brown seaweed | Fucoxanthin | 0.1 mg/kg/10 mg/kg of fucoxanthin | Pain | NA | Pre-treatment with fucoxanthin may protect the eyes from denervation and inhibit trigeminal pain in UVB-induced photokeratitis models. |

| Costa et al, 2015 | Animal-controlled study | Mice model | 7 animals per group | Brazil | Lithothamnion muelleri | Crude extract and the polysaccharide-rich fractions | (10, 30, or 100 mg.kg−1, in carboxymethylcellulose [CMC] 0.5% in filtered water), CaCO3 (100 mg.kg−1, dissolved in CMC 0.5% in filtered water) or FR (1 mg.kg−1, dissolved in CMC 0.5% in filtered water) | Arthritis | NA | L. muelleri extract and its polysaccharide-rich fraction effectively reduced joint inflammation and pain in an arthritis model. Treatment decreased neutrophil migration and chemokine production via effects on leukocyte-endothelial adhesion. These findings highlight L. muelleri as a promising source of anti-inflammatory polysaccharides for joint disorders. |

| Costa et al, 2020 | An animal randomized controlled study | Swiss mice model | 18 | Brazil | Gracilaria intermedia | Sulfated polysaccharide | 0.1, 0.3, 1, or 3 mg/kg of sulfated polysaccharide | Pain | ↓ Writhing response ↓ Formalin-induced nociception |

The Gracilaria intermedia polysaccharide reduced inflammatory pain by inhibiting paw edema and neutrophil migration. It modulated IL-1β production and reduced vascular and cellular phase inflammation. Its antinociceptive effect is linked to peripheral inhibition of inflammation-related pain mediators. |

| Coura, 2011 | Animal controlled study | Swiss mice model Wister mice model |

NA | Brazil | Gracilaria cornea | Sulfated polysaccharide | 3, 9, or 27 mg/kg of sulfated polysaccharide | Pain | ↓ Writhing response ↓ Formalin-induced nociception ↑ Hot-plate reaction time. |

In conclusion, Gc-TSP exhibits dose-dependent antinociceptive effects, acting peripherally at lower doses and centrally at 27 mg/kg. Its efficacy across writhing, formalin, and hot-plate tests highlights its potential as a broad-spectrum analgesic agent. |

| Coura et al, 2017 | Animal-controlled study | Wister rat model | 5 animals per group | Brazil | Gracilaria cornea | Polysulfated fraction | 9 mg/kg of polysulfated fractions | The temporomandibular joint | ↓ Formalin-induced nociception | In conclusion, Gc-FI from Gracilaria cornea significantly reduced TMJ pain in rats through activation of μ/δ/κ-opioid receptors and the NO/cGMP/PKG/K+ATP pathway. Its effect also involves heme oxygenase-1 (HO-1), highlighting multiple mechanisms in its antinociceptive action. |

| Delgado, 2013 | Animal-controlled study | Male OF-1 mice | 192 | Cuba | Dichotomaria obtusata | Lactonic/phenolic compounds | Methanolic extract (50 g seaweed in 500 mL methanol, 8-hour soak) | Inflammation, Pain | 1-No inhibition of phospholipase A2 activity 2-inhibited edema |

*The methanolic extract of D. obtusata exhibits potent topical anti-inflammatory and peripheral antinociceptive activities, likely due to synergistic effects of its bioactive compounds (e.g., phenolics, triterpenes). *Therapeutic potential: May be useful for treating inflammatory pain (e.g., arthritis, dermatitis) but requires further isolation of active compounds and mechanistic studies. |

| Santos et al., 2015 | Animal-controlled study | Male Swiss mice | 200 | Brazil | Sargassum polyceratium | 13²-hydroxy-(13²-S)-pheophytin-a Pheophytin-a (0.006% dry weight) 13²-hydroxy-(13²-R)-pheophytin-a |

Ethanol extract (SpEE) from 3 kg dried seaweed (7% yield), Intraperitoneal (i.p.): 50, 100, 200 mg/kg | Pain | reduced writhes Inhibited inflammatory phase Reduced paw-licking time |

*The ethanol extract of S. polyceratium exhibits significant peripheral antinociceptive activity in inflammatory pain models, attributed to porphyrin derivatives (pheophytins) and fucosterol. *Therapeutic Potential: May be useful for inflammatory pain conditions (e.g., arthritis), but central analgesic effects were absent. |

| De Sousa et al., 2013 | Animal-controlled study | Male Wistar rats Male Swiss mice |

23 | Brazil | Gelidium crinale | Sulfated galactan (SG-Ge) | Purified by ion-exchange chromatography (DEAE-cellulose). Doses: Anti-inflammatory (rats): 0.01, 0.1, 1 mg/kg (i.v.). Antinociceptive (mice): 0,1, 1, 10 mg/kg (i.v.). |

inflammation, Pain | Reduced the paw edema elicited by histamine Reduced the edema evoked by PLA2 |

SG-Ge presents an anti-inflammatory effect involving inhibition of histamine and arachidonic acid metabolites and also antinociceptive activity, especially in inflammatory pain with participation of the opioid system |

| De Souza et al., 2009 | Animal-controlled study | Swiss albino mice | 141 | Brazil | Caulerpa racemosa | Caulerpin (bisindole alkaloid) | Caulerpin: 100 µmol/kg (oral administration, p.o.) | Pain and inflammation | ↓ Writhing response ↑ Hot plate latency ↓ Formalin-induced licking |

Caulerpin demonstrated dual antinociceptive and anti-inflammatory effects in murine models. Acts on both peripheral (e.g., prostaglandins) and central (e.g., hot plate) pain pathways. No sedation or toxicity observed at tested doses. |

| de Araújo et al., 2016 | Animal controlled study | Swiss albino mice | 36 | Brazil | Ulva lactuca | Sulfated polysaccharide fraction (SP-UI) | SP-UI isolated via enzymatic digestion and ion-exchange chromatography, Dose: 1, 3, or 9 mg/kg (intravenous or subcutaneous). | Pain and inflammation | Reduced acetic acid-induced writhing Reduced bradykinin-induced paw edema No significant reduction in neutrophil infiltration |

SP-UI exhibits peripheral antinociceptive and anti-inflammatory effects primarily via bradykinin pathway inhibition, with low toxicity |

| Figueiredo et al, 2010 | Animal-controlled study | Wistar rats | 5 animals per group | Brazil |

Hypnea cervicornis

J. Agardh |

Agglutinin (HCA), a lectin | Agglutinin (HCA), a lectin administered intravenously at 0.1, 1, and 10 mg/kg | Inflammatory hypernociception (pain sensitization) | inhibited neutrophil migration increased nitric oxide (NO) production |

HCA from Hypnea cervicornis alleviates inflammatory pain by inhibiting neutrophil migration and enhancing NO production, independent of cytokine modulation. |

| Frestedt et al, 2009 | RCTs | Adults (35–75 years) with moderate-to-severe knee osteoarthritis | 29 | USA | Lithothamnion corallioides | Aquamin F | 2400 mg/day Aquamin (3 capsules × 3/day, each containing 267 mg Aquamin + 167 mg maltodextrin). | Knee osteoarthritis (OA) | NA | Aquamin may improve knee mobility and walking distance in OA patients during partial NSAID reduction, though it did not replace NSAIDs entirely for pain relief. |

| Guzman et al., 2001 | Animal-controlled study | Charles River CD-1 mice and Sprague-Dawley rats | 6–10 animals per group | Spain | Marine microalgae Chlorella stigmatophora and Phaeodactylum tricornutum | Polysaccharides, Phenolic compounds, Sulfated glycoproteins, and Carotenoids | Marine microalgae Chlorella stigmatophora and Phaeodactylum tricornutum, 15.625–250 mg/kg (aqueous/methanol extracts, intraperitoneal) | Pain and inflammation | Reduced writhing Reduced paw edema |

Aqueous extracts of C. stigmatophora and P. tricornutum demonstrated significant dose-dependent analgesic and anti-inflammatory effects in rodent models, primarily through hydrosoluble components, with C. stigmatophora showing superior potency. |

| Heffernan et al, 2020 | RCTs | Adults aged 50–70 years with mild symptomatic knee osteoarthritis | 30 | Ireland | Lithothamnion species | NA | Aq+: Daily dose of 3056 mg (2668 mg mineral-rich algae, 268 mg Mg (OH)2, 120 mg pine bark) | knee osteoarthritis (KOA) | NA | The study demonstrated that Lithothamnion-derived mineral-rich algae combined with seawater magnesium and pine bark (Aq+) was superior to glucosamine in reducing pain, improving physical function, and decreasing analgesic use in mild KOA, suggesting its potential as a supplementary treatment for early-stage osteoarthritis. |

| Hong et al, 2011 | Animal-controlled study | Wistar albino rats and Swiss albino mice | 6 animals per group | Vietnam | Sargassum swartzii (brown seaweed) and Ulva reticulata (green seaweed) | Polyphenols and Sulfated polysaccharides | Sargassum swartzii (brown seaweed) and Ulva reticulata (green seaweed), 250 mg/kg and 500 mg/kg body weight (oral) | Pain and inflammation | Reduced acetic acid-induced writhing writhing reduction Reduced carrageenan-induced paw edema |

Both seaweeds demonstrated significant analgesic and anti-inflammatory activity, with S. swartzii being more potent in chronic inflammation. No toxicity was observed up to 66 g/kg, supporting their safety for therapeutic use. |

| Hu et al, 2014 | Animal-controlled study | Sprague-Dawley rats | 30 | China | sulfated polysaccharide | Purified fucoidan | sulfated polysaccharide, Intrathecal injection (once daily, POD 11–20) at 15, 50, or 100 mg/kg | Neuropathic pain | ↓ Glial activation (GFAP/mac-1 markers) ↓ Pro-inflammatory cytokines (TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-6) ↓ ERK phosphorylation (MAPK pathway) |

Fucoidan attenuated neuropathic pain by inhibiting spinal neuroimmune activation (glia/cytokines/ERK), with optimal effects at 50–100 mg/kg. No toxicity observed. |

| Jarmkom et al, 2024 | In vitro experimental study | Caulerpa lentillifera | NA | Thailand | Caulerpa lentillifera (green seaweed, “sea grape”) | Flavonoids, saponins, terpenoids, coumarins | Caulerpa lentillifera: Decoction (boiling 100 g seaweed powder in 1,500 mL water for 2 hours, freeze-dried). Dose: 31.25–1,000 µg/mL. |

Arthritis | BSA denaturation inhibition | The decoction extract of Caulerpa lentillifera demonstrated significant anti-arthritis and antioxidant activities, attributed to its high phenolic/flavonoid content. Its potency surpassed diclofenac sodium in inhibiting protein denaturation, suggesting potential as a natural therapeutic for arthritis-related pain and inflammation. |

| Jeon et al, 2019 | Animal-controlled study | mice | 50 | South Korea | Sargassum muticum (brown algae) | Apo-9′-fucoxanthinone | Sargassum muticum (brown algae), SME at 50, 100, and 200 mg/kg (oral administration) | Rheumatoid Arthritis (RA) | reduced paw swelling, arthritis scores, and levels of inflammatory cytokines (IL-6, TNF-α, IFN-γ) in serum and lymphocytes | Sargassum muticum extract demonstrated potent anti-arthritic and analgesic effects by suppressing inflammatory cytokines and protecting joint integrity, suggesting its potential as a functional food or therapeutic agent for RA-related pain and inflammation. |

| Joung et al., 2020 | Animal-controlled study | mice | 40 | South Korea | Sargassum serratifolium (brown alga) | Meroterpenoid-rich fraction (MES) containing sarghydroquinotic acid (SHQA, 37.6%), sargaquinotic acid (SQA, 1.89%), and sargachromenol (SCM, 6.23%) | Sargassum serratifolium (brown alga): 20 mg/kg and 100 mg/kg MES orally administered via diet | Rheumatoid Arthritis (RA) | ↓ Pro-inflammatory cytokines: TNF-α, IL-6, and IL-1β levels decreased in serum and joint tissue ↓ MMP-9 and F4/80 ↓ NF-κB pathway |

MES from Sargassum serratifolium significantly alleviated RA symptoms, including pain-associated paw swelling and inflammation, by inhibiting NF-κB and downstream pro-inflammatory mediators. |

| Kim et al, 2014 | Animal-controlled study | mice | 7 animals per group | South Korea | Ecklonia cava (brown seaweed) | Ethanol extract (19.46% yield), rich in phlorotannins | Ecklonia cava (brown seaweed): 300 mg/kg (oral administration, p.o.). Duration: Single dose for postoperative pain (assessed at 6 h and 24 h). Daily for 15 days for neuropathic pain. |

Postoperative Pain Neuropathic Pain |

↓ Mechanical Hypersensitivity ↓ Thermal Hypersensitivity ↓ Ultrasonic Vocalizations (USVs) |

Ecklonia cava extract (300 mg/kg) significantly alleviated postoperative and neuropathic pain in rats by reducing mechanical/thermal hypersensitivity and distress vocalizations, likely via modulation of GABAergic pathways, suggesting potential as a natural analgesic. |

| Lee et al, 2023 | Animal-controlled study | Rats | NA | South Korea | Ulva prolifera (green macroalgae) | 30% methanol extract (30% PeUP; 22.1% yield), rich in polysaccharides, polyphenols, and sulfated compounds | Ulva prolifera (green macroalgae): 0.2, 0.4, 0.6 mg/mL of 30% PeUP. Duration: 1-hour pretreatment before IL-1β (10 ng/mL) stimulation for 24 hours. |

Osteoarthritis (OA) | ↓ PGE2 ↓ COX-2/iNOS ↓ MMPs/ADAMTS ↑ Collagen II & Aggrecan ↓ MAPK Pathway |

Ulva prolifera extract (30% PeUP) alleviated OA-related pain by inhibiting PGE2/COX-2, reducing cartilage-degrading enzymes (MMPs/ADAMTS), and blocking MAPK-driven inflammation, suggesting potential as a natural therapeutic for OA pain management. |

| Matta et al, 2015 | Animal-controlled study | Swiss mice | 6 animals per group | Brazil | Caulerpa kempfii (green algae) | Caulerpin, Caulerpicin, Sesquiterpenoids, and Caulerpenyne | Caulerpa kempfii (green algae): 100 mg/kg (oral administration, p.o.). Duration: Single dose administered 40 min before pain/inflammation induction. |

Pain | ↓ Visceral Pain (Acetic Acid Writhing) ↓ Neurogenic Pain ↓ Inflammatory Pain ↓ Inflammation (Carrageenan Peritonitis): Reduced leukocyte migration |

Caulerpa kempfii fractions (HE, EA, HA) demonstrated potent peripheral antinociceptive and anti-inflammatory effects, significantly reducing visceral and inflammatory pain (via prostaglandin/COX inhibition) and leukocyte migration, but lacked central analgesic activity (no thermal pain relief). |

| Brito Da Matta, 2011 | Animal-controlled study | Swiss mice | 6 animals per group | Brazil | Caulerpa mexicana and Caulerpa sertularioides | Caulerpin, Caulerpicin, Sesquiterpenoids, and Diterpenoids | Caulerpa mexicana and Caulerpa sertularioides: Oral administration of extracts (100 mg/kg) | Pain and inflammation | Reduced acetic acid-induced writhing increased latency time inhibited leukocyte migration |

Caulerpa extracts exhibit significant peripheral and central antinociceptive activity, likely via inhibition of inflammatory mediators (e.g., prostaglandins, cytokines) and opioid-like mechanisms. |

| Merchant et al, 2000 | Open-label pilot study | 20 patients (19 females, 1 male) with fibromyalgia syndrome | 20 | USA | Chlorella pyrenoidosa (unicellular green alga) | Chlorophyll, β-carotene, Chlorella Growth Factor (CGF), vitamins (B1, B2, B6, B12, C, K), minerals (Mg, Zn, Fe), amino acids, and dietary fiber | Chlorella pyrenoidosa (unicellular green alga): 10 g/day of Sun Chlorella tablets + 100 mL/day of Wakasa Gold liquid (containing CGF, malic acid, fructose) | Fibromyalgia syndrome | NA | Chlorella pyrenoidosa supplementation significantly reduced fibromyalgia-associated pain (TPI) in 44% of patients, though gastrointestinal side effects were common, warranting further placebo-controlled trials. |

| Moon et al, 2018 | Animal-controlled study | Rats | 25 | Korea | Codium fragile (Suringar) Hariot (green algae) | Aqueous extract of Codium fragile (AECF); contains sulfated polysaccharides, anti-inflammatory, and antioxidant compounds. | Codium fragile (Suringar) Hariot (green algae): In vitro: AECF (0.5, 1, 2 mg/mL) pre-treatment for 1 h, followed by IL-1β (10 ng/mL) stimulation. In vivo: Oral AECF (50, 100, 200 mg/kg body weight) daily for 8 weeks post-DMM surgery. |

Osteoarthritis (OA) | ↓ nitrite production, Inhibition of MAPK/NF-κB pathways | AECF alleviates OA progression by reducing cartilage degradation and inflammation via suppression of MAPK/NF-κB signaling, making it a potential therapeutic agent for OA-related pain and joint damage. |

| Myers, 2010 | Combined phase I and II open-label pilot study | 12 participants (5 females, 7 males) with diagnosed knee osteoarthritis (OA) | 12 | Australia | Fucus vesiculosus (85%), Macrocystis pyrifera (10%), Laminaria japonica (5%) | Fucoidans, polyphenols (phlorotannins), plus vitamin B6, zinc, manganese | Fucus vesiculosus (85%), Macrocystis pyrifera (10%), Laminaria japonica (5%): Low dose: 100 mg/day (75 mg fucoidan). High dose: 1000 mg/day (750 mg fucoidan). |

Osteoarthritis (OA) | NA | The seaweed extract complex significantly reduced OA-related pain and stiffness in a dose-dependent manner, demonstrating safety and efficacy over 12 weeks, warranting further phase III trials. |

| Neelakandan and Venkatesan, 2016 | Animal-controlled study | Rats | 6 animals per group | India | Sargassum wightii (brown seaweed) and Halophila ovalis (seagrass) | Sulfated polysaccharide fractions (Sw FrIII, Sw FrIV, Ho FrIII, Ho FrIV) with high sulfate (21–21.3%) and sugar (74.5–75.2%) content | Sargassum wightii (brown seaweed) and Halophila ovalis (seagrass): Dose: 2.5, 5, or 10 mg/kg (intravenous or subcutaneous). | Pain | Reduction in neutrophil migration reduction in paw volume |

Sulfated polysaccharides from S. wightii and H. ovalis demonstrated potent dose-dependent antinociceptive and anti-inflammatory effects in acute and chronic pain models, likely via central and peripheral mechanisms, with efficacy comparable to standard drugs (e.g., diclofenac). |

| Oliveira et al, 2020 | Experimental animal study | Rodent model (Male Swiss Mice) | 7 animals per group | Brazil | Gracilaria caudata | Sulfated polysaccharide | SP-GC (3, 10 or 30 mg/kg) | Rheumatoid arthritis (RA) and associated inflammatory pain (hypernociception) | ↓IL-1β levels, ↓MPO activity, ↓total leukocytes, PMN infiltrate, and ↓NO levels | SP-GC from Gracilaria caudata alleviates arthritis-related pain and inflammation by modulating neutrophil migration, IL-1β, and NO pathways, demonstrating therapeutic potential for RA without CNS side effects. |

| Pereira et al, 2014 | Animal-controlled study | Male Swiss mice | 5–6 animals per group | Brazil | Digenea simplex | Sulfated polysaccharide | PLS 10, 30, or 60 mg/kg (intraperitoneal) | Inflammatory pain (acute edema, peritonitis) and nociception (chemically/thermally induced pain) | ↓ Abdominal writhing (77% inhibition vs. acetic acid). ↓ Formalin-induced licking (60.5% in neurogenic phase; 61.7% in inflammatory phase). ↑ Latency in the hot plate test (160.5% at 90 min), suggesting central analgesic effects. |

PLS from D. simplex exhibits potent anti-inflammatory and antinociceptive effects by inhibiting neutrophil migration, pro-inflammatory cytokines (IL-1β, TNF-α), and mediators (histamine, serotonin), while also modulating central pain pathways, making it a promising candidate for inflammatory pain management. |

| Phull et al, 2017 | Animal-controlled study |

In vitro: Rabbit articular chondrocytes In vivo: Male Sprague-Dawley rats |

35 | Korea | Undaria pinnatifida | Fucoidans |

In vitro: Fucoidan (0–100 µg/ml) on chondrocytes. In vivo: Oral fucoidan (50 or 150 mg/kg body weight) |

Rheumatoid arthritis | Fucoidan ↓ COX-2 expression, ↓ paw edema, restored joint histology, and normalized hematological/biochemical markers (e.g., ↓ WBC, ↑ RBC, ↓ ESR). | Fucoidan from U. pinnatifida alleviates arthritis-related pain and inflammation by suppressing COX-2 and oxidative stress, offering a safer alternative to NSAIDs. |

| Quinderé et al, 2013 | Animal-controlled study | Male Swiss mice and male Wistar rats | 6 animals per group | Brazil | Acanthophora muscoides | Sulfated polysaccharide fraction (AmII) and total sulfated polysaccharides (Am-TSP) | AmII (1, 3, or 9 mg/kg, intravenous [iv] or subcutaneous [sc]) in writhing, formalin, and hot plate tests. | Pain: Peripheral nociception | Pain: ↓ Writhing response ↓ Licking time in the formalin test No effect in the hot plate test |

AmII from A. muscoides exhibits potent peripheral antinociceptive and anti-inflammatory effects, likely via histamine/serotonin pathway inhibition, without central action or significant toxicity, supporting its potential as a natural analgesic for inflammatory pain. |

| Ramamoorthi et al, 2025 | Preclinical in vivo study using a randomized controlled design | female Sprague-Dawley rats | 30 | India | Sargassum ilicifolium | Crude sulfated polysaccharide | CSP (5 mg/kg and 10 mg/kg, oral) | Rheumatoid arthritis | ↓ Paw swelling: CSP (5 mg/kg) showed 39.55% inhibition of edema (comparable to methotrexate). ↓ Pro-inflammatory cytokines: CSP reduced TNF-α, IL-2, and CD4+ cell expression in lymph nodes. ↓ Biochemical markers: Lowered ALT, AST, CRP, creatinine, and urea vs. arthritic control. |

CSP from S. ilicifolium at 5 mg/kg significantly alleviated arthritis symptoms by modulating cytokine cascades (↓TNF-α, IL-2) and reducing joint inflammation, with efficacy similar to methotrexate but fewer hepatic side effects. |

| Ribeiro et al, 2014 | Preclinical in vivo study using a randomized controlled design | Swiss mice and Wistar rats | 6 animals per group | Brazil | Caulerpa racemosa | Sulfated polysaccharide fraction | CrII (0.01, 0.1, 1.0 mg/kg, intravenous) | Inflammatory and nociceptive pain | ↓ Abdominal writhing ↓ Formalin-induced pain (Phase II): No central analgesia ↓ Paw edem ↓ Neutrophil migration |

CrII from C. racemosa demonstrated potent peripheral antinociceptive and anti-inflammatory effects (via HO-1 pathway) at low doses (0.01–1.0 mg/kg), with no central opioid-like activity or toxicity, suggesting therapeutic potential for inflammatory pain. |

| Da Conceição Rivanor et al, 2014 | Experimental study | Male Wistar rats | 6 animals per group | Brazil | Green seaweed Caulerpa cupressoides | Lectin (CcL) | CcL was administered intravenously at 0.1, 1, or 10 mg/kg, 30 minutes before zymosan injection (2 mg/articulation) into the TMJ. | TMJ inflammatory hyper-nociception and arthritis | CcL significantly reduced mechanical hypernociception and decreased leukocyte influx (77.3–98.5%) and myeloperoxidase activity in synovial fluid. | CcL from Caulerpa cupressoides demonstrated potent anti-nociceptive and anti-inflammatory effects in a rat model of TMJ arthritis, likely mediated through inhibition of IL-1β and TNF-α, offering a potential therapeutic alternative for inflammatory pain conditions. |

| Rivanor et al, 2018 | Experimental study | Male Wistar rats | 6 animals per group | Brazil | Green seaweed Caulerpa cupressoides | Lectin (CcL) | CcL administered intravenously at 0.1, 1, or 10 mg/kg, 30 minutes before inflammatory agents | Inflammatory hypernociception in the TMJ | Reduced plasma protein extravasation (↓Evans blue dye) and pro-inflammatory cytokines (TNF-α, IL-1β). Inhibited COX-2 and ICAM-1 expression, but not CD55. |

CcL from Caulerpa cupressoides demonstrated potent anti-nociceptive and anti-inflammatory effects in TMJ inflammatory hypernociception by inhibiting cytokines (TNF-α, IL-1β), COX-2, and ICAM-1, without involvement of cannabinoid/opioid systems or NO signaling, suggesting its potential as a peripheral-targeted therapeutic for inflammatory pain. |

| Rodrigues et al, 2013 | Experimental animal study | Male Swiss mice | 246 | Brazil | Caulerpa cupressoides | Sulfated polysaccharide fraction (SP1) | 3, 9, or 27 mg/kg (intravenous, i.v.) for antinociceptive tests; 27 mg/kg (intraperitoneal) | Pain (nociception) and inflammation | Reduced acetic acid-induced writhing | SP1 from Caulerpa cupressoides exhibits potent peripheral antinociceptive activity with minimal toxicity, supporting its potential as a natural analgesic for inflammatory pain. |

| Rodrigues et al, 2014 | Experimental animal study | Male Wistar rats | 36 | Brazil | Caulerpa cupressoides | Sulfated polysaccharide fraction (SP1) | 1, 3, or 9 mg/kg (subcutaneous, s.c.) administered 1 hour before zymosan injection | Acute arthritis | Pain: Cc-SP1 reduced mechanical hypernociception by 78.12% (1 mg/kg), 81.13% (3 mg/kg), and 87.43% (9 mg/kg) (p < 0.01 vs. zymosan). Inflammation: Inhibited leukocyte influx by 85–89.95% and myeloperoxidase (MPO) activity by 51–77.92% (p < 0.05), indicating reduced neutrophil infiltration. |

Cc-SP1 demonstrated potent dose-dependent antinociceptive and anti-inflammatory effects in TMJ arthritis, likely mediated by peripheral mechanisms (e.g., leukocyte migration inhibition), without central nervous system involvement. |

| Rodrigues et al, 2012 | Experimental animal study | Male Swiss mice | 6 animals per group | Brazil | Caulerpa cupressoides | Sulfated polysaccharide fraction (SP1) | Mice: 3, 9, or 27 mg/kg (intravenous, iv, for nociception tests). Rats: 3, 9, or 27 mg/kg (subcutaneous, sc, for inflammation tests). |

Acute nociception | Acetic acid test: Reduced writhes by 57% (3 mg/kg), 89.9% (9 mg/kg), 90.6% (27 mg/kg) Formalin test: Inhibited Phase 1 (neurogenic pain) by 42.47% (9 mg/kg), 52.1% (27 mg/kg), and Phase 2 (inflammatory pain) by 68.95–84.61% |

Cc-SP2 exhibits potent peripheral and central antinociceptive effects (via opioid pathways) and anti-inflammatory actions (via leukocyte migration inhibition), with minimal toxicity, supporting its potential as a natural analgesic for inflammatory pain. |

| Samaddar and Koneri, 2019 | Experimental animal study | Male Wistar rats | 6 per group | India | Ecklonia cava (brown seaweed) | Polyphenolic fraction (ECPP) | ECPP at 100 mg/kg and 200 mg/kg orally for 30 days | Diabetic Peripheral Neuropathy (DPN) | ECPP significantly improved neuropathic thermal analgesia, reducing tail-flick latency (↓3.29-fold) and hot-plate response time (↓5.06-fold). | EC polyphenols demonstrated potent neuroprotective effects in DPN by mitigating hyperglycemia-induced oxidative stress, inflammation, and AR overactivity, leading to significant pain relief and improved nerve function. |

| Shih et al, 2017 | Experimental animal study | Male Wistar rats | 6 animals per group | Taiwan | Sarcodia ceylanica | Polysaccharides, Acylglycerol compounds, and Aromatic compounds | PD1 (20 or 50 mg/kg, oral) | Inflammatory pain | ↓Paw edema: PD1 (50 mg/kg) reduced swelling ↓Thermal hyperalgesia ↓Mechanical allodynia ↓Leukocyte infiltration: Reduced MPO-positive cells in paw tissue ↓Pro-inflammatory mediators: Suppressed iNOS, IL-1β, and MPO expression |

PD1 alleviates pain by blocking inflammation (iNOS/IL-1β/MPO) and restoring nociceptive thresholds, supporting Sarcodia ceylanica as a natural pain-relief agent. |

| Silva et al., 2010 | Experimental animal study | Male Wistar rats | 6–8 animals per group | Brazil | Pterocladiella capillacea | Lectin | PcL (0.9, 8.1, or 72.9 mg/kg, intravenous (i.v.)) | Inflammatory pain (acute edema, peritonitis) and nociception (chemically/thermally induced pain) | ↓Writhing (acetic acid test): PcL (72.9 mg/kg) reduced writhes by 52% | PcL exhibits potent peripheral analgesic and anti-inflammatory activity by reducing inflammatory pain responses (writhing, formalin, edema) without central opioid effects, suggesting potential as a natural alternative for inflammatory pain management. |

| Souza et al, 2009 | Experimental animal study | male and female Swiss albino mice | 6–8 animals per group | Brazil | Caulerpa racemosa | Terpenoids, Acetogenins, and Polyphenols | 100 mg/kg, administered orally | Pain (nociception) and inflammation | Acetic acid test: All extracts reduced writhing (47.39–76.11% inhibition). Hot-plate test: Chloroformic and ethyl acetate phases increased latency (central analgesic effect). |

C. racemosa extracts, especially the ethyl acetate phase, exhibit promising antinociceptive and anti-inflammatory properties, validating their traditional use and potential for developing novel analgesics. |

| Souza et al, 2019 | Experimental animal study | male and female Swiss albino mice | 6–8 animals per group | Brazil | Hypnea pseudomusciformis | Sulfated polysaccharides (PLS) | PLS was administered orally at 5 mg/kg and 10 mg/kg doses. | Orofacial and craniofacial pain | PLS significantly reduced nociceptive behaviors induced by formalin, capsaicin, glutamate, cinnamaldehyde, and acidified saline, with mechanisms involving glutamatergic, nitrergic, TRP, and K+ATP pathways. No cytotoxicity or motor impairment was observed. | PLS from Hypnea pseudomusciformis exhibits significant orofacial antinociceptive activity in rodents, likely through modulation of TRP channels, glutamatergic signaling, and NO/K+ATP pathways, without adverse effects, supporting its potential as a therapeutic agent for acute pain. |

| Vaamonde-García et al., 2022 | In vitro experimental study | Human primary chondrocytes from the hip joints of 4 adult female donors | 4 | Spain | Undaria pinnatifida (Up), Sargassum muticum (Sm) | Crude fucoidans extracted via: Microwave-assisted extraction (Up-MAE). Pressurized hot-water extraction (Sm-PHW). Ultrasound-assisted extraction (Sm-US). |

Undaria pinnatifida (Up), Sargassum muticum (Sm) 1, 5, and 30 µg/mL of crude fucoidans. | Osteoarthritis (OA) | Anti-inflammatory effects: Significant reduction in IL-6 production (protein level) by all fucoidans, with Up-MAE showing the most consistent effect. Downregulation of IL-6 and IL-8 gene expression by Up-MAE Antioxidant effects: Upregulation of Nrf-2/HO-1 pathway (↓ oxidative stress). |

Crude fucoidans from Undaria pinnatifida and Sargassum muticum exhibit anti-inflammatory and antioxidant properties in OA chondrocytes, reducing IL-6 and ROS—key mediators of pain and joint degradation. While ineffective against senescence, their ability to modulate inflammatory pathways supports their potential as therapeutic agents for OA pain relief. Further in vivo studies are needed to validate efficacy and optimal dosing. |

| Vanderlei et al, 2010 | Experimental animal study | Male Swiss mice, and Male Wistar rats | 6 animals per group | Brazil | Caulerpa cupressoides | Purified lectin (Ccl.) | Caulerpa cupressoides 3, 9, or 27 mg/kg (intravenous, i.v.) for antinociception; 9 mg/kg (i.v.) for anti-inflammatory tests. | Inflammatory pain and nociception | Antinociceptive effects: Reduced acetic acid-induced writhing Inhibited formalin-induced licking time No effect in the hot plate test (central analgesia), suggesting peripheral action. |

Ccl. from Caulerpa cupressoides exerts significant peripheral antinociceptive and anti-inflammatory effects via lectin-specific and partial opioid pathways, without central action or toxicity. It represents a potential therapeutic alternative for inflammatory pain management, warranting further clinical investigation. |

| Vieira et al, 2004 | Experimental animal study | Swiss mice | NA | Brazil | Bryothamnion seaforthii | PII Fraction and Carbohydrate Fraction | PII Fraction (26.8% carbohydrate, lectin-rich): 0.1–10 mg/kg (ip/po) Carbohydrate Fraction (CF) (21% of alga weight): 1–20 mg/kg (ip/po) |

Pain | PII Fraction: ↓ Writhing ↓ Formalin-induced licking ↑ Hot-plate latency CF: ↓ Writhing ↓ Formalin licking Effects are heat-stable but independent of sulfate groups. |

Carbohydrate-rich fractions from B. seaforthii exhibit potent, dose-dependent antinociceptive effects in murine pain models, mediated partially via opioid pathways, with oral efficacy and heat stability, suggesting therapeutic potential for pain management. |

| Yegdaneh et al., 2020 | Experimental animal study | NMRI male mice | 6–8 animals per group | Iran | Sargassum glaucescens | Methanol-ethyl acetate | Sargassum glaucescens: Acute: 100, 200 mg/kg (i.p., single dose). Chronic: 25–200 mg/kg (i.p., daily for 5 days). |

Neuropathic Pain | Acute: ↓ Paw licking duration (P < 0.001) at 100 and 200 mg/kg (i.p.) vs. control. Chronic: ↓ Paw licking at 100–200 mg/kg (i.p.) over 5 days (P < 0.05). |

Sargassum glaucescens extract effectively alleviates paclitaxel-induced neuropathic pain in mice, with both acute and chronic treatments showing significant antinociceptive effects. The lack of reversal by naloxone or yohimbine indicates a unique, non-opioid mechanism of action. This supports the potential use of S. glaucescens as complementary therapy for chemotherapy-related neuropathy, though clinical studies are required to validate efficacy and safety in humans. |

| Yuvaraj, 2017 | Experimental animal study | Wistar albino rats | 6 animals per group | India | Dictyopteris australis | Methanol extraction (Soxhlet method) of dried seaweed | Methanol extraction Doses: 200 mg/kg and 400 mg/kg (oral). |

Thermal nociception | Significantly ↑ tail withdrawal latency | The methanolic extract of Dictyopteris australis exhibits dose-dependent analgesic activity in thermal pain models, with 200 mg/kg being optimal. The non-linear response suggests complex bioactive interactions. Future research should isolate specific compounds (e.g., terpenes, sulfated polysaccharides) to elucidate mechanisms and therapeutic potential for pain relief. |

| Yuvaraj et al, 2013 | Experimental animal study | Male Wistar rats | 6 animals per group | India | Sargassum wightii | Sulfated polysaccharides | Sulfated polysaccharides Doses: Antinociceptive tests: 2.5, 5, 10 mg/kg (intravenous, i.v.). Anti-inflammatory tests: 2.5–10 mg/kg (subcutaneous, s.c.). |

Pain and inflammation | ↓ Licking time, ↑ Latency to thermal pain, and ↓ Paw edema | Sw-SP and Ho-SP exhibit significant antinociceptive and anti-inflammatory activities in acute and chronic pain models, likely via inhibition of inflammatory mediators and neutrophil migration. The 10 mg/kg dose showed optimal efficacy, supporting further development as natural therapeutics for inflammatory pain conditions like arthritis. |

Summary characteristics of included studies.

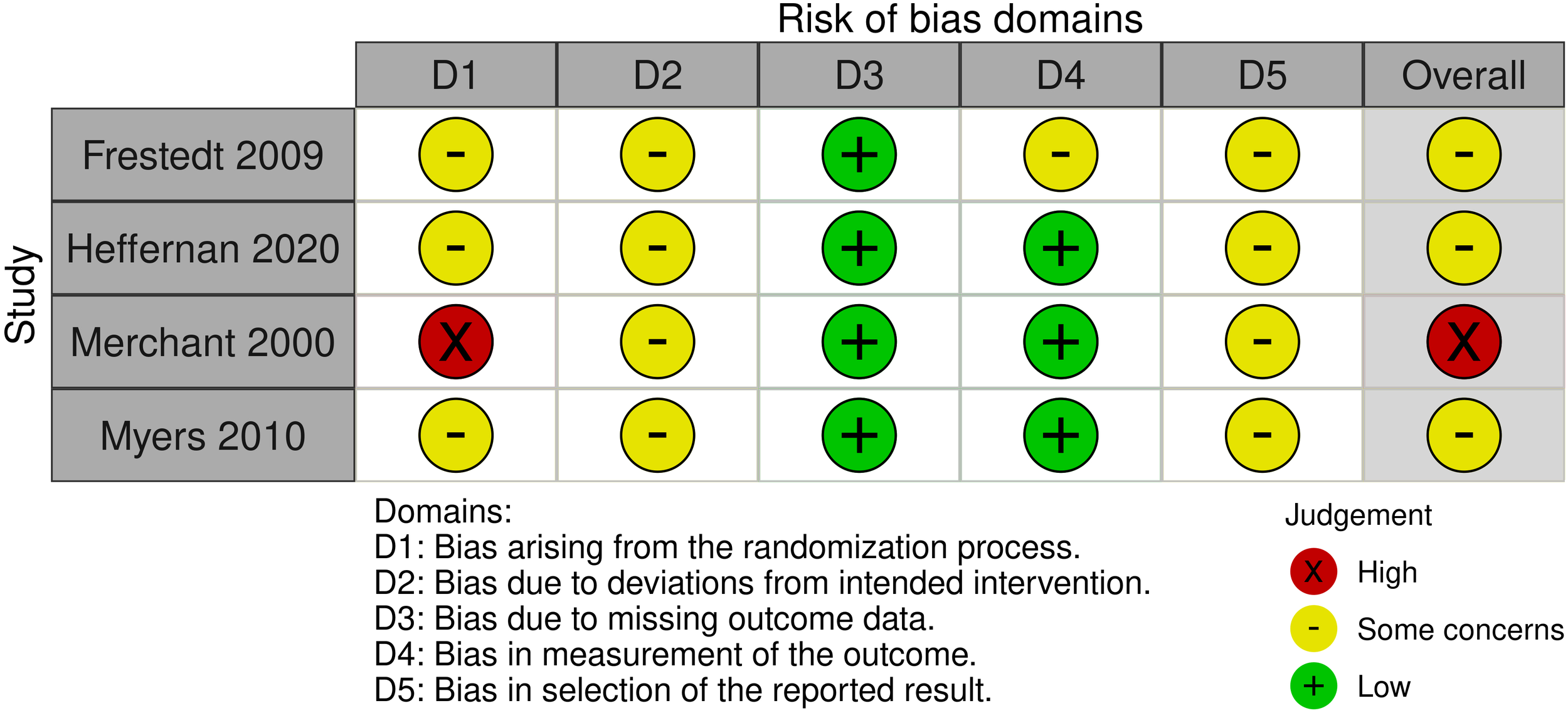

3.2 Risk of bias

Sixty-one studies were evaluated using the SYRCLE tool, with 33 studies categorized as having a low risk of bias, 19 exhibiting an unclear risk, and 9 showing a high risk of bias. Detailed information regarding the risk of bias for each study is presented in Table 2. ROB2 was implemented to assess the randomized trials, with three studies rated as having some concerns and one demonstrating a high risk of bias, as illustrated in Figure 2.

Table 2

| Study ID | Sequence generation: Was the allocation sequence adequately generated and applied? | Baseline characteristics: Were groups similar at baseline? | Allocation concealment: Was allocation adequately concealed? | Random housing: Were animals randomly housed? | Blinding of caregivers/investigators: Were personnel blinded? | Random outcome assessment: Were animals selected randomly for outcome? | Blinding of outcome assessor: Was outcome assessor blinded? | Incomplete outcome data: Were dropouts explained? | Selective reporting: Are all outcomes reported? | Overall |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Abdelhamid et al, 2018 | Low | Low | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Low | Low | Low |

| Abreu et al, 2016 | Unclear | Low | Unclear | Unclear | High | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Low | Unclear |

| Mahardani Adam, 2021 | Low | Unclear | High | Unclear | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low |

| Albuquerque et al, 2013 | High | Low | Unclear | Unclear | High | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low |

| Anca et al, 1993 | Unclear | Unclear | High | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | High | High | Unclear | High |

| Aragao et al, 2016 | Low | Low | Unclear | Unclear | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low |

| De Araújo et al, 2011 | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low |

| Aragao et al, 2016 | Low | Low | High | Unclear | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low |

| Araújo et al, 2017 | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low |

| Ardizzone et al, 2023 | Unclear | Unclear | High | High | Unclear | Low | High | Low | Low | High |

| Assreuy et al, 2008 | Low | High | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low |

| Bhatia et al, 2015 | Low | Low | Unclear | Unclear | Low | Unclear | Unclear | Low | Low | Unclear |

| Bhatia et al, 2019 | Unclear | High | Unclear | High | Low | Low | High | Low | Low | High |

| Bitencourt et al, 2008 | High | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low |

| Carneiro et al, 2014 | Unclear | Low | High | Unclear | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low |

| Chatter et al, 2012 | Low | Low | Unclear | Unclear | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low |

| Chen et al, 2019 | Unclear | Unclear | High | High | Unclear | Low | High | Low | Low | High |

| Costa et al, 2015 | Low | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low |

| Costa et al, 2020 | Low | Low | High | Unclear | Low | Low | Unclear | Low | Low | Low |

| Coura et al, 2012 | Unclear | Low | Unclear | Unclear | High | Low | High | Low | Low | Unclear |

| Coura et al., 2017 | Low | Unclear | High | Unclear | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low |

| García Delgado et al, 2013 | Unclear | Low | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Low | Unclear | Low | Low | Unclear |

| Santos et al., 2015 | Low | Unclear | High | Unclear | Low | Low | Unclear | Low | Low | Low |

| de Sousa et al., 2013 | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Low | Unclear | Low | Low | Unclear |

| De Souza et al, 2009 | Low | Low | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Low | Low | Low | Unclear | Unclear |

| de Araújo et al., 2016 | Low | Low | High | Unclear | Low | Low | Unclear | Low | Low | Low |

| Figueiredo et al., 2010 | Unclear | Unclear | High | High | Unclear | Low | High | Low | Low | High |

| Guzman et al, 2001 | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Low | Unclear | Low | Low | Unclear |

| Hong et al, 2011 | Unclear | Low | Unclear | Low | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Low | Low | Low |

| Hu et al, 2014 | Low | Low | Unclear | Low | Low | Low | Unclear | Low | Low | Low |

| Jarmkom et al., 2024 | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | High | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Low | Unclear |

| Jeon et al, 2019 | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Unclear | Low | Low | Low | Unclear |

| Joung et al, 2020 | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Low | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Low | Unclear |

| Kim et al, 2014 | Unclear | Low | Unclear | Low | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Low | Unclear |

| Lee et al, 2023 | Low | Unclear | High | Low | Unclear | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low |

| Matta et al, 2015 | Unclear | Low | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Low | Unclear | Unclear |

| Brito Da Matta et al., 2011 | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Low | Unclear |

| Moon et al, 2018 | Unclear | Low | Unclear | Low | Low | High | Unclear | Low | Low | Low |

| Neelakandan and Venkatesan, 2016 | Low | Unclear | Unclear | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low |

| Oliveira et al, 2020 | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Low | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Low | Unclear |

| Pereira et al., 2014 | Low | Unclear | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low |

| Phull et al, 2017 | Unclear | Low | Unclear | Low | Unclear | High | Unclear | Low | Low | High |

| Quinderé et al, 2013 | Unclear | Low | Unclear | Low | Low | Unclear | Unclear | Low | Low | Low |

| Ramamoorthi et al, 2025 | Low | Unclear | Low | Low | Unclear | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low |

| Ribeiro et al, 2014 | Low | Low | Low | Low | Unclear | Low | Low | Low | Unclear | Low |

| Da Conceição Rivanor et al, 2014 | Unclear | Low | High | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Low | Unclear |

| Rivanor et al, 2018 | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Low | Low | Unclear | High | Low | Low | Low |

| Rodrigues et al, 2013 | Low | Low | Low | Low | Unclear | Low | Low | Unclear | Low | Unclear |

| Rodrigues et al, 2014 | Unclear | Low | Unclear | Low | High | High | Low | Low | Low | Low |

| Rodrigues et al, 2012 | Low | Unclear | Unclear | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low |

| Samaddar and Koneri, 2019 | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | High | High | Low | Low | High |

| Shih et al, 2017 | Unclear | Low | Unclear | Low | Low | Unclear | Low | Low | Unclear | Low |

| Silva et al, 2010 | Low | Unclear | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low |

| Souza et al, 2009 | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Low | Unclear | Unclear | Low | Unclear | Unclear |

| Souza et al, 2019 | Low | Unclear | Low | Low | Unclear | Low | Unclear | Low | Low | Low |

| Vaamonde-García et al., 2022 | Unclear | Unclear | High | High | High | Unclear | High | Low | Low | High |

| Vanderlei et al, 2010 | Unclear | Low | Unclear | Low | Low | Unclear | Low | Low | Low | Low |

| Vieira et al., 2004 | Low | Low | Unclear | Low | Low | Low | Unclear | Low | Low | Low |

| Yegdaneh et al., 2020 | Unclear | Low | Unclear | Low | Unclear | High | High | Low | Low | High |

| Yuvaraj, 2017 | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Unclear | Low | Unclear | Low | Unclear |

| Yuvaraj, 2017 | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Low | Low | Low | Unclear |

SYRCLE ROB for animal studies.

Figure 2

Risk of bias of randomized controlled trials.

3.3 Evidence from experimental studies

3.3.1 Sulphated polysaccharides

SPs demonstrated a potent peripheral analgesic effect, with studies revealing their ability to reduce pain through several mechanisms. For instance, Araújo et al (De Araújo et al., 2011). demonstrated a dose-dependent inhibition of writhing responses, with reductions of 40.6%, 56.6%, and 70.2% at 1 mg/kg, 3 mg/kg, and 9 mg/kg of SPs extracted from Solieria filiformis, respectively. Notably, more recent evidence supports these peripheral analgesic benefits through the significant release of β-endorphin in the subnucleus caudalis by SP extracts from Solieria filiformis (Araújo et al., 2017). The central analgesic effects of SPs have also been evident in several studies. Coura et al (Coura et al., 2012). found a central antinociceptive effect for SPs derived from Gracilaria cornea, as evidenced by the significantly increased latency in the hot-plate test at the highest SP dosage (27 mg/kg). Similar findings were obtained from the SPs extracted from Digenea simplex, with a 160.5% elevation in thermal pain latency in the hot plate test with a dose of 60 mg/kg (Pereira et al., 2014). Nevertheless, Albuquerque et al (Albuquerque et al., 2013). did not find any significant central antinociceptive effect of SPs derived from Dictyota menstrualis at any of the tested concentrations in the hot plate test.

3.3.2 Polyphenols

phlorotannins, have emerged as potent analgesics with peripheral and central mechanisms. Abdelhamid et al (Abdelhamid et al., 2018). demonstrated a marked peripheral antinociceptive effect of phlorotannin-rich fractions from Cystoseira sedoides, as evidenced by a 90.16% reduction in acetic acid-induced writhing. Notably, the central analgesic effects were also prominent with this polyphenolic derivative, as shown by the significant increase in latency in the hot-plate test, with effects lasting 120 min (Abdelhamid et al., 2018). In the same context, Ecklonia cava polyphenols have been shown to significantly reduce postoperative and neuropathic pain in rats, with enhancements in mechanical sensitivity by 682% and decreases in distress vocalizations by 62.8% (Kim et al., 2014). These findings align with those of Samaddar et al (Samaddar and Koneri, 2019), who revealed a significant reduction in neuropathic pain in diabetic rats through notable improvements in thermal analgesia and substantial inhibition of aldose reductase and subsequent sorbitol accumulation.

3.3.3 Proteins

Protein extracts from seaweeds, particularly lectins, are key elements in managing pain through proposed peripheral and central antinociceptive effects. Solieria filiformis lectin showed a considerable reduction in abdominal writhing without a significant impact on thermal nociception in the hot plate test, indicating a lack of central analgesic action (Abreu et al., 2016). Notably, there were no signs of toxicity in mice over the 7-day administration period, highlighting S. filiformis lectin as a safe, peripherally acting analgesic agent. Furthermore, a dose-dependent antinociceptive response was observed with Caulerpa cupressoides-derived lectin, showing reductions of 37.2%, 53.5%, and 86% in acetic acid-induced writhing with 3, 9, and 27 mg/kg lectin doses, respectively (Vanderlei et al., 2010).

3.3.4 Other compounds

A brown aqueous fraction derived from Himanthalia elongata revealed considerable central analgesic activity, as evidenced by the notable increase in reaction time in the hot-plate test at doses of 20, 40, and 100 mg/kg (Anca et al., 1993). However, only the highest dose of this aqueous fraction (100 mg/kg) showed a pronounced peripheral analgesic effect, with a significant reduction in nociceptive responses in the writhing test (Anca et al., 1993). Chatter et al (Chatter et al., 2012). found a significant reduction in pain for brominated diterpene derivatives from Laurencia glandulifera across several mechanisms. The brominated diterpene exhibited dose-dependent inhibition of acetic acid-induced writhing, reducing the frequency of pain behavior and increasing the onset latency, which ranged from approximately 20 to over 60 s.

An alkaloid extract, Caulerpin, from green algae also revealed pronounced peripheral and central analgesic actions by mitigating writhing responses and increasing hot-plate latency (De Souza et al., 2009). Furthermore, Amansia multifida ethanolic extracts demonstrated dose-dependent inhibition of peripheral nociceptive responses, with a maximum reduction of 78% at 5 mg/kg in the acetic acid writhing test, outperforming the standard drug indomethacin (45%) (Aragao et al., 2016). The A. multifida ethanolic extracts also demonstrated a central analgesic effect in the tail flick test, increasing pain latency by 64% and 56% at 90 and 150 min, respectively, at a dose of 10 mg/kg. Yuvaraj et al (Yuvaraj, 2017). found notable analgesic activity for the methanolic extract of Dictyopteris australis in rats. Although the 200 mg/kg dosage of the methanolic extract showed a significant increase in tail withdrawal latency compared to diclofenac sodium (at 3 h, 5.75 s vs. 2.25 s), the 400 mg/kg dosage showed less efficacy relative to diclofenac sodium (at 3 h, 3 s vs. 2.25 s), indicating a non-linear dose-response.

3.4 Evidence from human studies

Multiple human studies have explored the role of seaweed in managing pain associated with various diseases, particularly in osteoarthritis. For instance, a randomized trial by Frestedt et al (Frestedt et al., 2009). found no significant difference between seaweed-derived Aquamin F (2400 mg/day) and placebo in WOMAC pain scores (p = 0.63) in patients with knee osteoarthritis. Notably, Aquamin F was associated with significant improvements in range of motion and six-minute walk distance compared to the placebo, following a 50% reduction in NSAID use. In contrast, in symptomatic knee osteoarthritis, the combination of mineral-rich algae with seawater-derived magnesium and pine bark significantly reduced pain, with a large effect size (d’ = 0.73, p < 0.01). At the same time, glucosamine showed no significant reduction in pain (d’ = 0.38, p = 0.06) (Heffernan et al., 2020). In the same context, a seaweed extract complex containing fucoidans from brown algae, vitamin B6, zinc, and manganese showed significant pain relief in patients with osteoarthritis, with a dose-dependent pattern of pain reduction (Myers, 2010). Chlorella pyrenoidosa, a unicellular green alga rich in chlorophyll and β-carotene, was utilized in patients with fibromyalgia. Supplementation resulted in significant reductions in the tender point index after two months (30 vs. 25, p = 0.01) (Merchant et al., 2000).

4 Discussion

This systematic review provides a comprehensive and robust evaluation of the role of different seaweed species and their associated bioactive extracts in pain management. Different seaweed species and their bioactive compounds have demonstrated pronounced peripheral and central analgesic effects.

4.1 Preclinical evidence

SPs derived from Solieria filiformis revealed significant peripheral antinociceptive effects, with a dose-dependent inhibition in the writhing test, reaching 70% with a 9 mg/kg dosage of SP. Furthermore, Gracilaria cornea-derived SPs also showed a considerable central analgesic effect, with a substantial increase in latency in the hot-plate test at the highest SP dosage (27 mg/kg). In contrast, Dictyota menstrualis-SP extracts showed no significant central analgesic effect in the hot plate test at any of the evaluated doses. Polyphenols, particularly phlorotannins from Cystoseira sedoides, have also demonstrated significant antinociceptive effects. These substances resulted in a 90% reduction in the writhing test and a substantial increase in latency in the hot plate test. Moreover, polyphenols extracted from Ecklonia cava have been shown to improve mechanical sensitivity and decrease stress in postoperative and neuropathic pain models. Notably, Amansia multifida ethanolic extracts showed superior peripheral and central analgesic effects compared to standard drugs such as indomethacin. Furthermore, protein extracts, such as lectins from Solieria filiformis and Caulerpa cupressoides, demonstrated peripheral analgesic benefits without significant central effects. Other derivatives, such as brominated diterpenes from Laurencia glandulifera and the alkaloid caulerpin, also exhibited pronounced peripheral and central antinociceptive actions.

4.2 Human evidence

Human evidence has shown conflicting results. Aquamin F showed no improvement in pain scores compared to the placebo, despite substantial improvements in the range of motion and six-minute walk distance in patients with knee osteoarthritis. In contrast, a mineral-rich algae blend with seawater magnesium and pine bark significantly reduced pain, surpassing the effects of glucosamine supplementation. Similarly, fucoidan-containing seaweed extracts improved osteoarthritis-related pain.

Seaweeds are multicellular, photosynthetic organisms that significantly impact aquatic ecosystems, contribute to oxygen production, and serve as food and physical habitats for various marine organisms. Additionally, they aid in minimizing ocean acidity, which emphasizes their significant role as a nature-based solution to global warming (Cabral et al., 2016; Duarte et al., 2017; Kim et al., 2017; Hasselström et al., 2018). Seaweeds have been traditionally consumed in multiple Asian countries, including China, Japan, and Korea, owing to their health-promoting properties. From a nutritional standpoint, seaweeds are rich in carbohydrates (up to 60%) and proteins (17-44%), contain very little fat (< 4.5%), and are packed with essential micronutrients such as vitamins, minerals, and pigments (Lomartire and Gonçalves, 2022). Many seaweed species are considered promising candidates for biotechnological applications because of their unique biological properties. Several compounds derived from seaweeds are associated with significant health benefits. However, the effects of these bioactive compounds on pain management have not yet been well established.

SPs are commonly extracted from seaweed and exhibit prominent antinociceptive, anti-inflammatory, and antioxidant effects (De Araújo et al., 2011). These extracts have a unique chemical structure rich in polyanions, which enables them to interact with various types of proteins (Arfors and Ley, 1993). In vivo evidence by Araújo et al (De Araújo et al., 2011). supported the ability of SPs to significantly reduce peripheral pain without a notable impact on the central pain pathways. SPs showed a marked dose-dependent inhibition in the acetic-acid writhing test and the inflammatory phase of the formalin test, reaching 70.2% inhibition at 9 mg/kg in the writhing test and 84.6% in the formalin test, indicating a substantial peripheral anaglesic effect for SPs. These antinociceptive effects were similar to those of conventional analgesics, such as indomethacin and morphine, highlighting the strong peripheral analgesic effect of SPs. These peripheral analgesic effects could be attributed to the significant inhibition of peripheral inflammatory mediators, such as prostaglandins, substance P, bradykinin, and cytokines, which sensitize nociceptors (Araújo et al., 2017; De Araújo et al., 2011). Importantly, Araújo et al (De Araújo et al., 2011). did not find any significant effect of SPs on the hot plate test, a model that measures the centrally mediated analgesic response, at any of the SP doses (1, 3, and 9 mg/kg). In contrast, Coura et al (Coura et al., 2012). found a significant increase in pain latency in the hot plate test with the highest SP dose (27 mg/kg); however, lower doses (3 and 9 mg/kg) were ineffective. Notably, the effect of the 27 mg/kg dose was comparable to that of morphine at the 30-minute time point and further reversed by naloxone, an opioid antagonist, which confirms an opioid-like central mechanism for SPs.

These findings highlight the potent peripheral analgesic action of SPs at either lower or higher dosages, whereas the central analgesic effect was achieved at higher SP doses. Seaweed extracts showed reductions ranging from approximately 40 to 90 percent, depending on the species, extract, and dose in several preclinical experiments, indicating significant percent inhibition in conventional nociceptive assays (acetic acid-induced writhing, formalin, and hot plate). Although direct head-to-head statistical equivalency claims are rare and methods/reporting heterogeneity precludes conclusive conclusions regarding equivalence to NSAIDs or opioids, some of these studies also included positive controls (indomethacin, morphine), leading to reductions in the expected ranges for these assays. Consequently, even though the impact sizes seem encouraging, the therapeutic relevance needs to be confirmed (Coura et al., 2012).

Polyphenols are naturally occurring substances extracted mainly from brown seaweeds and have pronounced antioxidant and anti-inflammatory activities. Phlorotannins belong to the polyphenol family and have emerged as promising substances for managing pain. An in vivo animal study utilized phlorotannin-rich fractions (PHT) from three different Mediterranean brown seaweeds (Cystoseira sedoides, Cladostephus spongeosis, and Padina pavonica) found significant analgesic effects for these substances (Abdelhamid et al., 2018). Among these, the phlorotannin extracts from C. sedoides exhibited the most substantial peripheral analgesic effects, achieving 90.16% inhibition with a 100 mg/kg dosage in the acetic acid-induced writhing test, outperforming standard drugs such as acetylsalicylate of lysine, which achieved a 57.79% inhibition at a 200 mg/kg dosage. Furthermore, phlorotannin extracts from C. sedoides and C. spongeosis demonstrated a considerable increase in pain latency in the hot plate test. In contrast, the extracts from P. pavonic were ineffective. Moreover, the central analgesic effects of phlorotannin extracts from C. sedoides (50 and 100 mg/kg) were comparable to those of tramadol and lasted up to 120 min. Interestingly, the co-administration of phlorotannin extracts from C. sedoides (100 mg/kg) and tremadol (25 mg/kg) showed a significantly greater and longer-lasting analgesic effect than either agent alone, suggesting a potential synergistic interaction between them.