Abstract

Vibrio harveyi is capable of inducing vibriosis in Haliotis discus hannai and causes enormous economic losses to marine mollusks. The intestinal microbiota plays critical roles in immune homeostasis and provides essential health benefits or poses risks to the host. However, there is still little information about the intestinal microbiota responses of H. discus hannai to V. harveyi infection. We investigated the variations in the mortality rate, pathological changes, and intestinal microbiota communities of abalone after exposure to V. harveyi. The present study investigated the intestinal microbial response to acute infection of H. discus hannai with V. harveyi at 12 hours post-infection (hpi), 32 hpi and 60 hpi by 16S rRNA gene sequencing. The results indicated that prolongation of infection exerts a significant impact on the intestinal microbial community, and within-group variability gradually decreased. At 32 hpi and 60 hpi, the relative abundance of Mycoplasmataceae and Ruminococcaceae was significantly decreased, while Vibrionaceae and Fusobacteriaceae exhibited a significant increase in relative abundance. The results demonstrated that infection of abalone with V. harveyi promoted the proliferation of pathogenic bacteria in the intestinal microbiota and thereby facilitated the development of disease in the abalones. This study aimed to explore the role of the intestinal microbiota in the pathogenic mechanism of V. harveyi infection, and provide new scientific insights into disease courses of abalones.

1 Introduction

In marine environments, bacterial pathogens are ubiquitous and pose a continuous threat to the health of most aquaculture species. Particularly, vibriosis is a significant challenge to mollusks, as many Vibrio species are recognized as key causative agents of widespread aquatic animal mortality outbreaks (Ma et al., 2024). The Gram-negative marine bacterium V. harveyi is an opportunistic pathogen, it is also a prominent member of the Vibrionaceae family widely distributed in both artificial and natural aquatic systems (Montánchez and Kaberdin, 2020). It is widely distributed in the seawater, sediments, biological surfaces of tropical and subtropical marine environments, and infects a diverse range of economically important aquatic animals through waterborne transmission, mechanical injury, or the food chain (Nurhafizah et al., 2021; Ke et al., 2017), including Crassostrea hongkongesis (Hou et al., 2023), Epinephelus coioides (Zhang et al., 2023), Litopenaeus vannamei (Gan et al., 2024), and H. discus hannai (Choi et al., 2022; Lee et al., 2023). Typically, V. harveyi infects its host through the sequential processes of adhesion, invasion, proliferation, and toxin secretion, ultimately resulting in host mortality (Mok et al., 2003). Thus, V. harveyi is a highly pathogenic bacterium that poses a severe threat to global aquaculture sustainability.

Pacific abalone (H. discus hannai) is a gastropod species distributed along the coastline across East Asia, where it is one of the most value-added mollusk species (Cook, 2019). During large-scale disease outbreaks in abalone, the bacterial pathogens are typically Gram-negative bacteria, particularly V. harveyi (Sawabe et al., 2007; Travers et al., 2008; Jiang et al., 2013). In 2002, mass mortalities of H. discus hannai occurred within a few days at abalone farm. The primary clinical manifestation was severe hemolymphatic abnormalities in the circulatory system, characterized by disrupted hemocyte morphology and impaired coagulation function, which conclusively identified V. harveyi as the causative agent of this epizootic event (Sawabe et al., 2007). Subsequently, V. harveyi-associated myatrophy syndrome has been increasingly reported in southern China, with this pathogen infecting Haliotis diversicolor supertexta across all size classes and inducing high mortality rates in aquaculture (Jiangyong et al., 2010). Lee et al. (2023) reported that high water temperature made H. discus hannai more susceptible to V. harveyi infection, which increased the reactive oxygen species in the blood cells and destroyed the mitochondria. Concurrently, H. discus hannai hemocytes exhibit heightened pro-inflammatory responses and caspase-dependent apoptosis, compromising immune defenses. Besides, according to the transcriptomic analysis, high temperature activates TNF-α and interleukin 17 signaling pathways to induce inflammation (Lee et al., 2023). The research on the pathogenic mechanisms of V. harveyi infection in H. discus hannai is still under exploration.

The intestinal microbiota is widely recognized as the “second genome” of animals. The symbiotic relationship between the intestinal microbiota and its host is crucial, as it contributes to the host’s energy balance, metabolism, intestinal health, immune activity, and neural development (Singh et al., 2025). However, when the mutualistic relationship between the host and its microbiota is disrupted, the intestinal microbiota can cause or contribute to disease (Yang and Cong, 2021). For example, the relative abundances of Proteobacteria, Fusobacteria, Bacteroidetes, and Firmicutes change in grass carp (Ctenopharyngodon idellus) after Aeromonas hydrophila challenge, leading to the deformation of the intestinal villi, redness and congestion at the injection site, and even the host mortality (Yang et al., 2016). On the contrary, the gut immune responses that are induced by commensal microbiota regulate the composition of the microbiota. In fish, Wu et al. (2016) comprehensively investigated gut liver immunity in Streptococcus agalactiae infected tilapia, demonstrating that the tilapia gut and liver collaborate immunologically to maintain immune homeostasis via species specific strategies (Wu et al., 2016). In addition, the intestinal microbiota exerts pivotal functions in the development of gut-associated lymphoid tissue, the activation of intestinal immune responses, and the inhibition of pathogen colonization—thereby contributing to disease resistance and the maintenance of intestinal homeostasis (Okubo et al., 2015; Deng et al., 2020). Therefore, the changes in the intestinal microbiota caused by V. harveyi infection play an important role in host resistance to V. harveyi infection (Whyte, 2007). Neither the changes in the intestinal microbiota of H. discus hannai infected with V. harveyi nor the corresponding disease progression has been investigated or reported. Whether the intestinal microbiota contributes to disease progression or regulates immune homeostasis remains unknown.

In the present study, H. discus hannai was selected as the research object. We conducted histopathological analysis and examined the structure and function of the intestinal microbiota in H. discus hannai following V. harveyi infection. High-throughput 16S rRNA gene sequencing and bioinformatic analysis were used to investigate dynamic changes in the intestinal microbiota under different infection processes, and to evaluate how the interspecific interactions and functions of intestinal microbiota were altered during the progression of V. harveyi - induced disease in H. discus hannai. This study provides a scientific basis for immunological or microbe-based therapies for V. harveyi disease in H. discus hannai.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Animals and experimental infection

H. discus hannai (with an average shell length of 6.53 ± 0.2 cm) were purchased from Yancheng, Jiangsu Province, China, with 100 abalones. After being transferred to the aquaculture facility of the School of Marine and Biological Engineering, Yancheng Teachers University, they were cultivated in 40 L tanks (20 individuals per tank) containing aerated, sand-filtered seawater for a period of five days. During this period, the salinity and temperature of the seawater were maintained at 30 ± 1 ppt and 25 ± 1 °C, respectively. During the acclimatization period, half of the seawater was provided daily, and fresh seaweed (Laminaria japonica) was provided daily. After the acclimatization period, aquaculture water and 20 abalones were randomly selected for V. harveyi testing, which yielded negative results.

Bacterial V. harveyi strains were previously isolated from the sick abalones and characterized in our laboratory. The V. harveyi strains were cultured on glass slants overnight and resuspended in 5 mL sterile seawater. The cells were diluted to an optical density at OD600 of 1.0 with sterile seawater. The bath method was used because it mimics the real environment where abalones are exposed to V. harveyi. The infection groups were treated with the bath method at a final dosage of 3×106 CFU/mL (acute infection, the most prominent histopathological changes in the hepatopancreas of abalones), and the control group were bath with sterile seawater. All methods were conducted in accordance with the approved protocols and relevant guidelines.

2.2 Sample collection

Daily inspections of the tanks were carried out three times a day (morning, noon, and evening) to monitor the survival status of H. discus hannai. Dead abalones were promptly removed and recorded for constructing the survival curve at 0 hpi, 6 hpi, 12 hpi, 24 hpi, 32 hpi, 48 hpi, 60 hpi, and 72 hpi. Sampling was conducted after the stage close to death at each infection processes, including 12 hpi (start of the experiment), 32 hpi (rapid mortality), 60 hpi (after rapid mortality). During the infection processes, one abalone was sampled from each of the three challenged tanks at each time point. The abalone was dissected on a clean ice surface for sampling. Cross-sections of abalones, including hepatopancreas, were sampled from each individual. One section was fixed in Davidson’s alcohol-formalin-acetic acid fixative for 36 h, after which it was transferred to 70% ethanol in anticipation of a histological analysis. Briefly, the histological sections were made according to standard protocols, including dehydration in ethanol series, clearing, embedding in paraffin and cutting into 3-5 μm thick sections using a rotary microtome. The tissue sections were subjected to staining with hematoxylin and eosin (Li et al., 2024). Intestinal contents were carefully extruded using graded ethanol, thoroughly mixed in sterile culture dishes, and transferred into 1.5 mL sterile centrifuge tubes, each of the six abalones was treated as an independent sample. The samples were flash-frozen in liquid nitrogen and then stored at -80 °C for intestinal microbiota analysis.

2.3 DNA extraction and bacterial 16S rRNA gene sequencing

Total bacterial DNA from the intestinal contents of H. discus hannai was extracted using the HiPure Stool DNA Kit (Magen Biotech Inc., Guangzhou, China), with all operations strictly following the manufacturer’s recommended standard protocol. The concentration and purity of the extracted DNA were quantified and qualified using a Nanodrop™ 2000 spectrophotometer (NanoDrop Technologies, LLC, Wilmington, DE, USA). Only DNA samples that met the quality criteria for PCR amplification were selected for subsequent experiments.

Amplification of the V3-V4 hypervariable region of the bacterial 16S rRNA gene was carried out using the primer pair 343F (5’-TACGGRAGGCAGCAG-3’) and 798R (5’- AGGGTATCTAATCCT-3’). The total volume of the PCR reaction mixture was 30 μL, with the following components: 15 μL of 2×Gflex Buffer, 2 μL of dNTPs (2.5 mM), 1 μL each of the forward and reverse primers (5 μM), 0.6 μL of Tks GflexTM DNA Polymerase (1.25 U/μL), and 50 ng of DNA template. Amplification was performed on an ABI GeneAmp® 9700 thermal cycler (ABI, Carlsbad, CA, USA), and the thermal cycling program was set as follows: initial denaturation at 94 °C for 5 minutes, followed by 30 cycles of denaturation at 94 °C for 30 seconds, annealing at 56 °C for 30 seconds, and extension at 72 °C for 20 seconds, and concluded with a final extension at 72 °C for 5 minutes. For each sample, three independent PCR replicates were conducted to ensure the reliability of experimental results.

The quality of PCR amplicons was verified by 1% agarose gel electrophoresis. Amplicons that passed quality verification were purified using magnetic bead-based purification kits. The purified amplicons served as templates for the second round of PCR amplification. The second PCR used the same reaction mixture composition and thermal cycling conditions as the first round, except that the number of cycles was reduced (to minimize the accumulation of non-specific amplicons). After the second round of PCR, the amplicons were re-verified by agarose gel electrophoresis and subjected to a second magnetic bead purification step. The concentration of the finally purified amplicons was determined using a Qubit 2.0 fluorometer (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA, USA). All samples were pooled at equimolar concentrations based on the quantified values of individual purified products. The pooled sample was subsequently subjected to high-throughput sequencing using the NovaSeq 6000 platform (Shanghai OE Biomedical Technology Co., Ltd.).

2.4 Processing of illumina sequencing data

Raw sequencing data of 16S rRNA gene amplicons were processed and analyzed using QIIME2 (Hall and Beiko, 2018), a widely used platform for microbiome bioinformatics. The DADA2 workflow-an established tool for high-fidelity sequence processing-was utilized for denoising steps (including filtering, trimming, and error correction), a process that yielded a table of amplicon sequence variants (ASVs)-a high-resolution alternative to traditional operational taxonomic units (OTUs) [25]. Representative sequences for each ASV were selected according to the default parameter settings of the QIIME2 platform. These representative sequences were then taxonomically classified against the SILVA 138 database, a comprehensive and frequently updated resource for prokaryotic taxonomic assignment (Hall and Beiko, 2018; Bars-Cortina et al., 2023). To ensure comparability across all samples (and eliminate biases introduced by uneven sequencing depths), the ASV abundance table was rarefied to match the lowest sequence depth detected among the entire set of samples.

2.5 Statistical analyses

Survival curves were generated with GraphPad. Taxonomic compositions of the microbiota were characterized via the QIIME script summarize_taxa_through_plots.py, which generates hierarchical taxonomic summaries across samples. Alpha diversity was evaluated based on the Observed species index, a core metric for quantifying species richness. These indices were computed using the alpha_diversity.py and collate_alpha.py scripts within the QIIME framework. For beta diversity analyses, Bray-Curtis dissimilarity matrices-commonly used to measure community compositional differences were generated via the beta_diversity.py script. Principal Coordinates Analysis (PCoA) based on Bray-Curtis distances was employed to visualize group-specific clustering patterns in microbiota composition. Clustering analysis of inter-group microbiota differences, also based on Bray-Curtis distances, was conducted via the unweighted pair-group method with arithmetic mean (UPGMA) algorithm implemented in the R package phangorn. Statistical differences in microbiota structure across groups were evaluated using ADONIS (Permutational Multivariate Analysis of Variance, PERMANOVA) from the R package vegan, which tests for significant community-level variations. One-way Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) was conducted utilizing the aov function in R, with post-hoc comparisons performed using Tukey’s test from the multcomp package to identify pairwise differences. Differences in taxon relative abundances were assessed via Linear Discriminant Analysis (LDA) Effect Size (LEfSe) with a threshold LDA score>3.0, implemented on the Galaxy platform (version 2.0; http://galaxy.biobakery.org/). To reduce noise from low-abundance taxa, ASVs with a relative abundance > 1% in at least one sample were retained for co-occurrence network analysis. Spearman correlation coefficients between all retained ASV pairs were computed, with only pairs exhibiting R>0.6 and P<0.05 included in the network. Correlations were calculated via the Hmisc package in R, and the resulting co-occurrence network was visualized using Gephi software (version 0.10). All other data visualizations were generated with the R package ggplot2 for consistent and publication-ready figures.

3 Results

3.1 Clinical signs and mortality

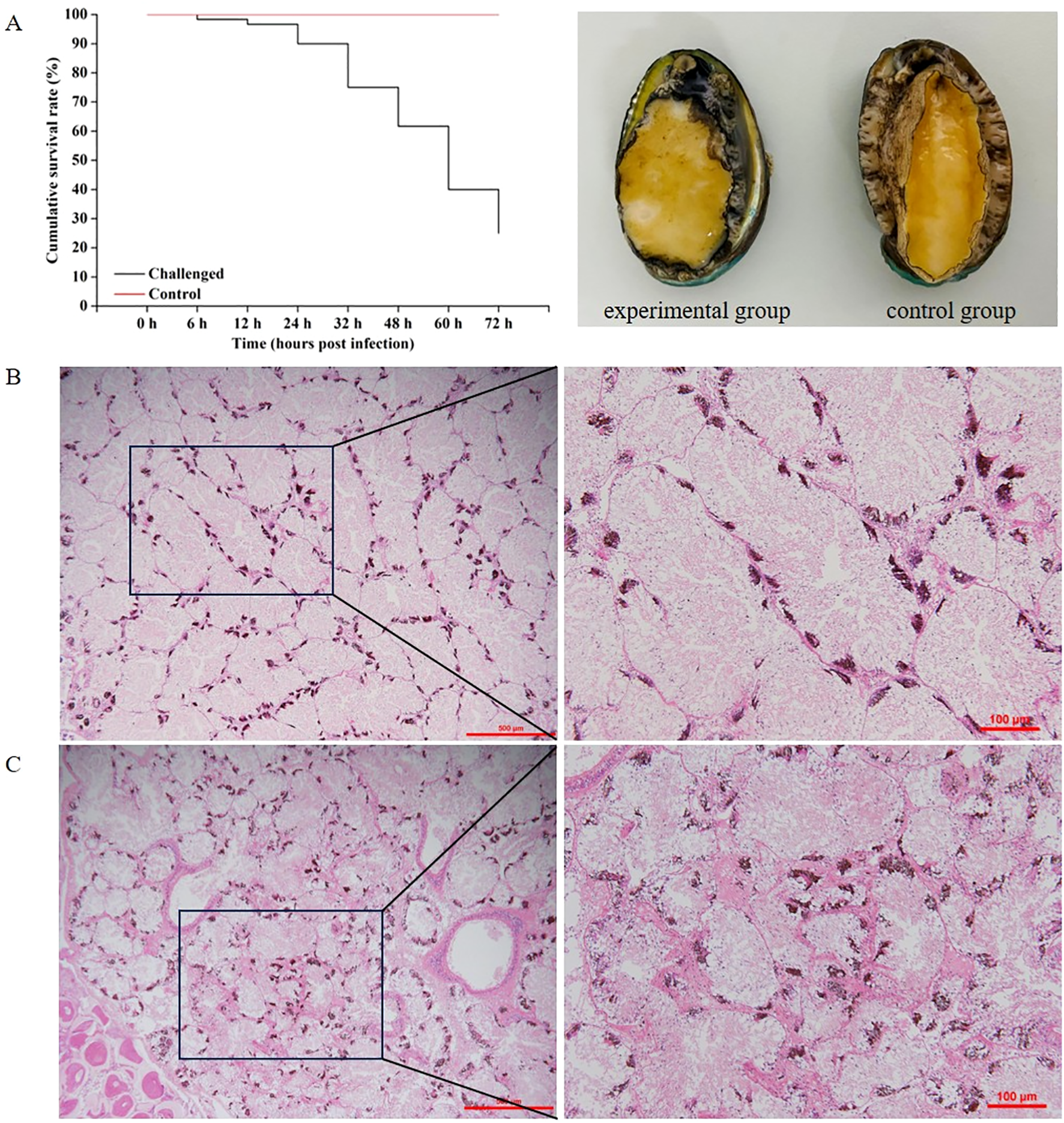

The survival of abalones were monitored on a daily basis, and the resulting survival curves were plotted (Figure 1A). The most striking anomaly observed in the experimental group was the turbid and frothy water, which manifested approximately 24 hpi. Acute mortality was observed in abalones at 48 hpi. The cumulative mortality of abalones was 1.67% at 6 hpi, 3.33% at 12 hpi, 10% at 24 hpi, 25% at 32 hpi, 38.33% at 48 hpi, 60% at 60 hpi and 75% at 72 hpi (Figure 1A). The control group demonstrated no mortality, the seawater remained relatively clear, abalone individuals were healthy and free of rotten tissues, and no histopathological changes were observed in HE staining. White rotten parts could be seen on the abdominal feet of abalones during V. harveyi infection period (Figures 1A, B). We aimed to investigate the changes in the intestinal microbiota of H. discus hannai with V. harveyi. Therefore, this study only focus on the description of pathological changes in H. discus hannai hepatopancreas, which is also a key target organ for V. harveyi infection in abalones. At 48 hpi and 72 hpi, gross lesions were observed in the hepatopancreas in all cases. The most notable sign of inflammation was the aggregation and infiltration of hemocytes in the connective tissues of the hepatopancreas. The heavy infiltration of hemocytes was particularly evident around the vacuolated digestive tubules at 60 hpi (Figure 1C). These results were consistent with the subsequent results of intestinal microbiota.

Figure 1

(A) Survival curve and clinical images of V. harveyi-infected diseased abalone (left) and healthy abalone (right). (B) Histopathology investigation of healthy H. discus hannai hepatopancreas. (C) Histopathological investigation of V. harveyi infected H. discus hannai hepatopancreas at 60 hpi. Scale bar = 500 μm and 100 μm, respectively.

3.2 Intestinal microbial diversity of H. discus hannai under different infection times

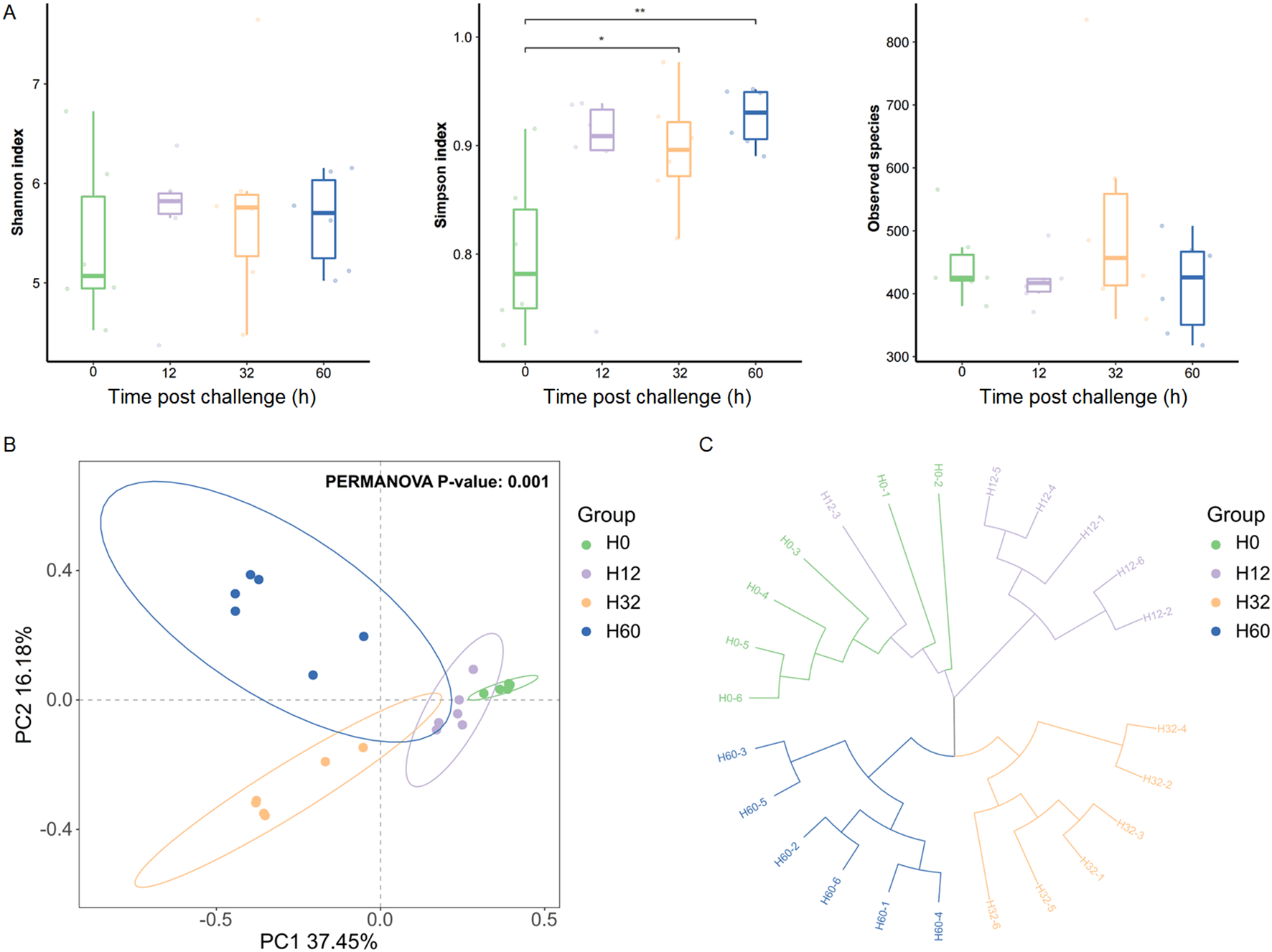

The diversity of intestinal microbiota in H. discus hannai showed significant differences under V. harveyi infection. The alpha diversity of the intestinal microbiota was assessed using the Shannon index, Simpson index and Observed species (Figure 2A). Simpson index showed that the species of intestinal microbiota increased over time at 30 hpi (P<0.05) and 60 hpi (P<0.01), while it remained stable at 12 hpi (Figure 2A). Principal component analysis (PCA) of the H. discus hannai intestinal microbiota 16S rRNA gene sequencing during V. harveyi infection. Each shape represents an individual group. The PCA plot captures the variance in the dataset in terms of the principal components and displays the most significant of these on the X and Y axes. The results indicate that the intestinal microbiota data are of high quality, as the six replicate samples are clustered together based on infection conditions. PERMANOVA showed that the community compositions differed marginally significantly among the four groups (P=0.001) (Figure 2B). UPGMA clustering of intestinal microbiota based on Bray-Curtis distance, the results showed that there were differences in community structure at the four infection time points (Figure 2C). The structure of the intestinal bacterial community was similar before 32 hpi, whereas significant changes occurred after 32 hpi.

Figure 2

The diversity changes of the intestinal microbiota in H. discus hannai.(A) Shannon index (α-diversity) of intestinal microbiota. (B) PCoA plot (β-diversity) of intestinal microbiota. (C) UPGMA clustering of intestinal microbiota based on Bray-Curtis distance. Significant differences are indicated by asterisks (*p value < 0.05; **p value < 0.01).

3.3 Dominant bacterial composition of intestinal microbiota under different infection times

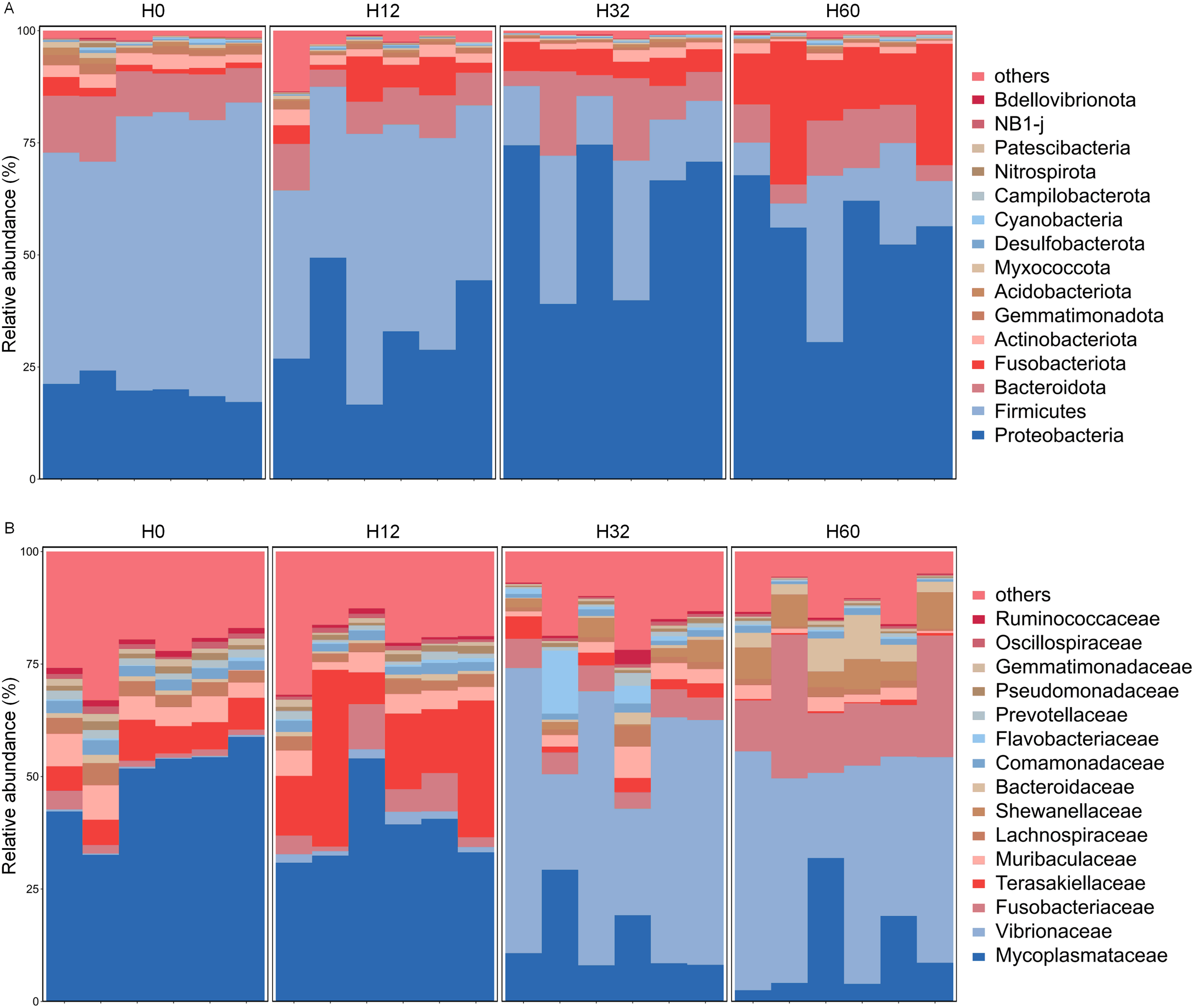

The composition of the intestinal microbiota in H. discus hannai showed significant differences under V. harveyi infection (Figure 3). The top 15 species in terms of abundance of the intestinal microbiota of H. discus hannai in each group at the phylum and family levels are shown in Figure 3. At the phylum level, the top 15 phyla in abundance were Bdellovibrionota, NB1-j, Patescibacteria, Nitrospirota, Campilobacterota, Cyanobacteria, Desulfobacterota, Mococcota, Acidobacteriota, Gemmatimonadota, Actinobacteriota, Fusobacteriota, Bacteroidota, Firmicutes, and Proteobacteria, respectively. Before infection with V. harveyi, the dominant phylum of the intestinal microbiota was Firmicutes. As the infection duration prolonged, Proteobacteria and Bdellovibrionota were the dominant phyla at 32 hpi and 60 hpi. At the family level, the top 15 taxa in terms of abundance were Ruminococcaceae, Oscillospiraceae, Gemmatimonadaceae, Pseudomonadaceae, Prevotellaceae, Flavobacteriaceae, Comamonadaceae, Shewanellaceae, Bacteroidaceae, Lachnospiraceae, Muribaculaceae, Terasakiellaceae, Fusobacteriaceae, Vibrionaceae, and Mycoplasmataceae, respectively. Before infection with V. harveyi and at 12 hpi, the dominant phylum of the intestinal microbiota in H. discus hannai was Mycoplasmataceae, whereas at 32 hpi and 60 hpi, the dominant phylum shifted to Vibrionaceae.

Figure 3

Dominant bacterial composition of intestinal microbiota under different infection times in H. discus hannai (top 15 relative abundances). (A) The bar chart showed the top 15 relative abundances at phylum level. (B) The bar chart showed the top 15 relative abundances at family level. Bars represent individual samples, different colors correspond to distinct annotation information, others denote all species excluding the top 15.

3.4 Differential genera in the intestinal microbiota of H. discus hannai infected with V. harveyi

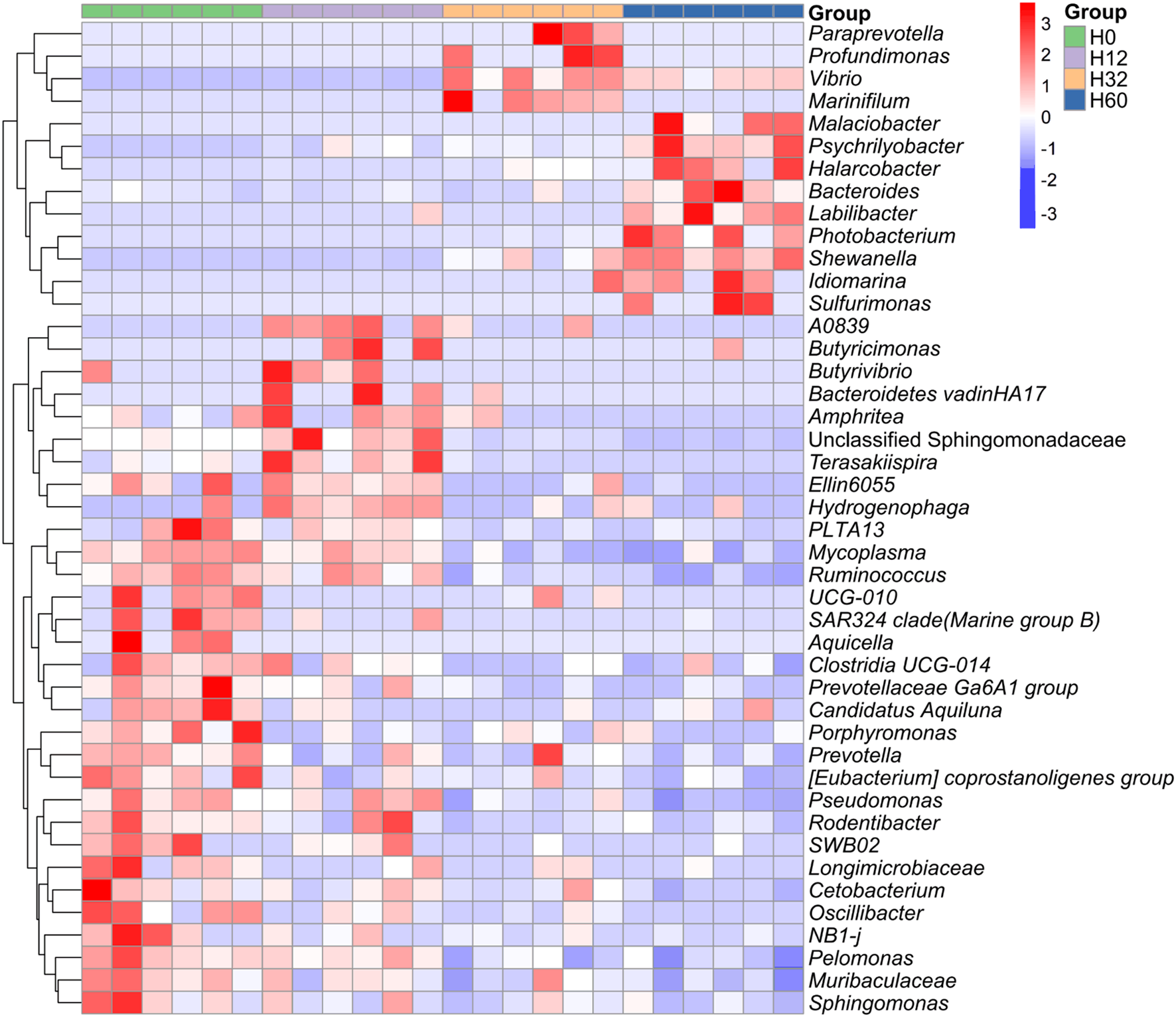

As revealed by the comparison of heatmaps of the differential bacterial communities among the four groups after Z-score normalization (Figure 4), among the differential bacterial communities in the four groups (in terms of relative abundance), the dominant genera in the intestinal microbiota of H. discus hannai at 32 hpi with V. harveyi were mainly Paraprevotella, Profundimonas, Vibrio, and Marinifilum. At 60 hpi, the dominant genera were mainly the Malaciobacter, Psychrilyobacter, Halarcobacter, Bacteroides, Labilibacter, Photobacterium, Shewanella, Idiomarina, and Sulfurimonas. However, the dominant genera at the early stage of infection (12 hpi) and before infection were highly similar, for example, PLTA13, Mycoplasma, and Ruminococcus.

Figure 4

Differential genera in the intestinal microbiota of H. discus hannai infected with V. harveyi. Heatmap of shared genera in the intestinal microbiota of H. discus hannai under different infection times (H0, H12, H32 and H60, relative abundance of at least >3% in one sample). The group labels at the top denote the group affiliation of the samples (H0, H12, H32 and H60). The dendrogram on the left side represents the clustering of genera. Orange indicates a relatively high abundance of genera, while blue indicates a relatively low relative abundance of genera.

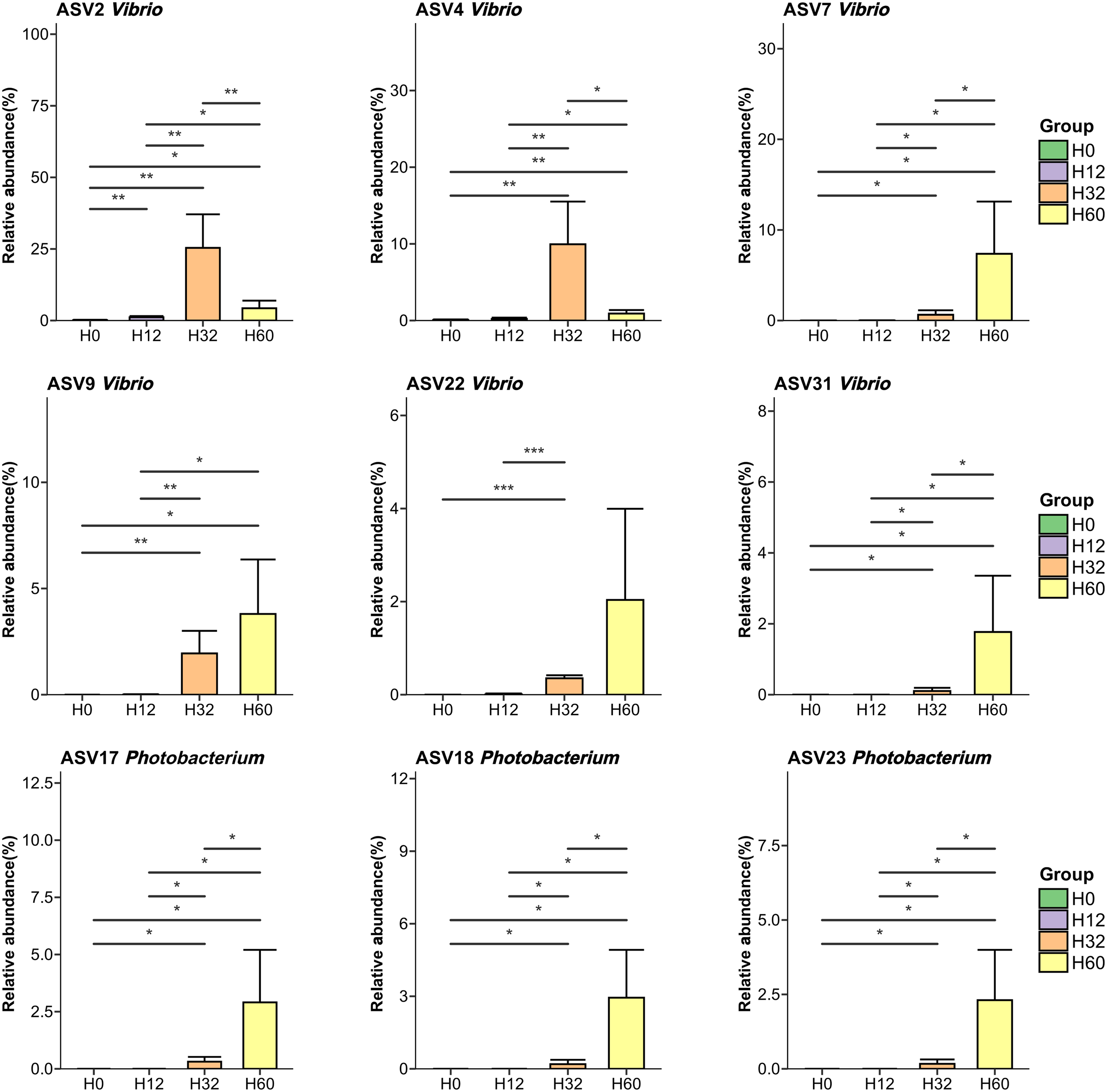

3.5 Analysis of the changes in the Vibrionaceae ASV in the intestinal microbiota

To investigate the temporal dynamics of specific taxa in the intestinal microbiota during V. harveyi infection, the relative abundances of Vibrio- and Photobacterium-associated ASVs were quantified across four groups (Figure 5). For Vibrio-affiliated ASVs, ASV2 and ASV4 exhibited extremely low abundances in H0 and H12 but significantly peaked at H32 (relative abundances ~25% and ~12%, respectively; P < 0.01), followed by declines in H60. In contrast, ASV7, ASV9, ASV22, and ASV31 showed negligible abundances in H0–H32 yet were specifically enriched at H60 (relative abundances ranging from ~3% to ~10%, P< 0.05 or P< 0.001). Meanwhile, all Photobacterium-associated ASVs (ASV17, ASV18, ASV23) remained at low levels in H0–H32 but exclusively proliferated at H60 (relative abundances ~3% for each, P< 0.05). Collectively, these results indicated that V. harveyi infection drove time-dependent enrichment of distinct Vibrio subpopulations (with peaks at either 32 hpi or 60 hpi) and late-stage proliferation of Photobacterium in the intestinal microbiota.

Figure 5

Analysis of the changes in the Vibrio ASV and Photobacterium ASV. With a relative abundance greater than 3% in at least one sample. Significant differences are indicated by asterisks (*p value < 0.05; **p value < 0.01; ***p value < 0.001).

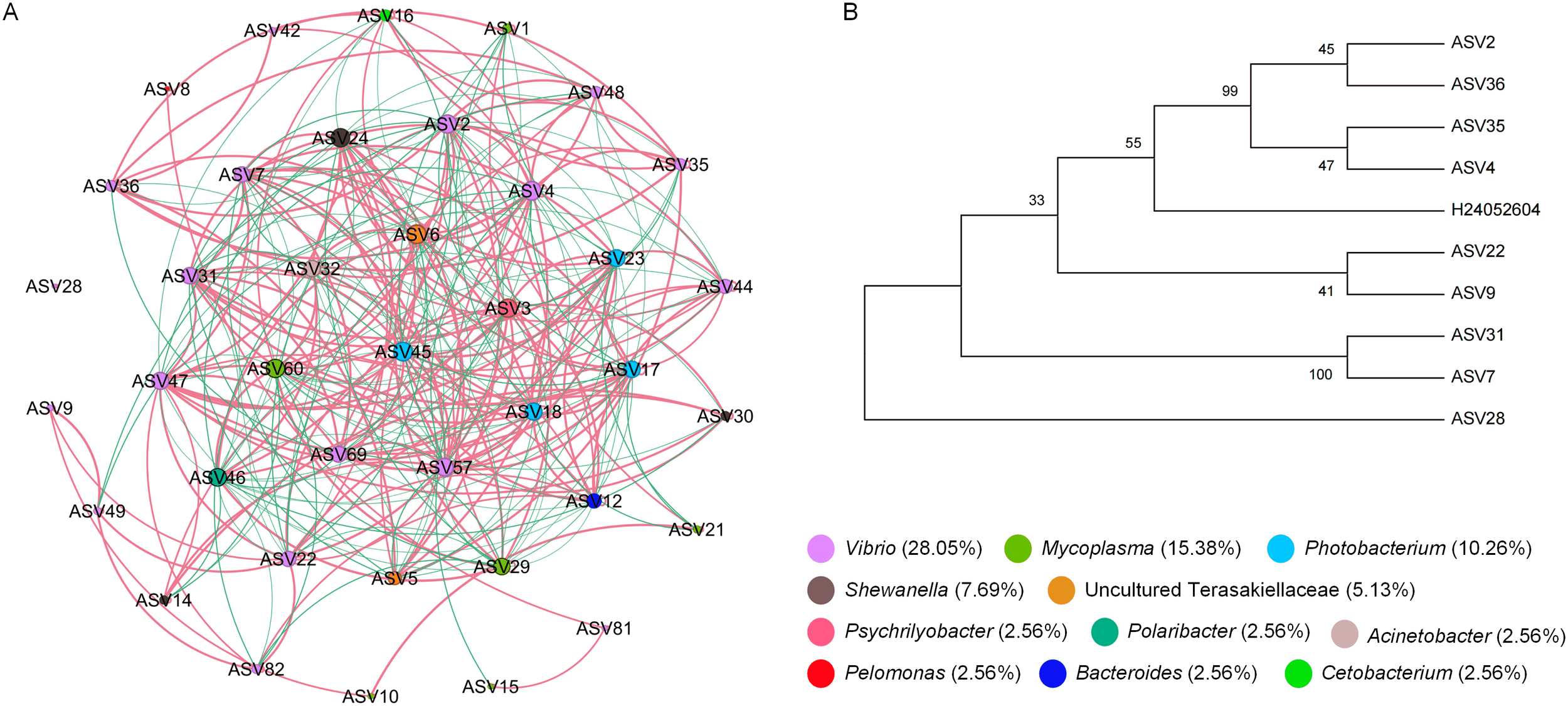

3.6 Microbial co-occurrence network analysis

Microbial co-occurrence network analysis was performed to explore the dynamic effects of V. harveyi infection on the interaction network of intestinal microbiota in H. discus hannai (Figure 6). The dense network of edges suggested complex interspecific interactions among ASVs, with Vibrio-associated nodes (e.g., ASV2, ASV4, ASV7) exhibiting extensive connections, implying their potential core roles in microbial interactions. Additionally, network topological parameters such as degree, closeness centrality, harmonic closeness centrality, and betweenness centrality all indicated that ASV2 and ASV4 were crucial central nodes, serving as the “keystone” of the co-occurrence network. The results showed that network analysis based on the time points after 32 hpi (i.e., at 32 hpi and 60 hpi) revealed that ASV2 and ASV4 were identified as core species due to their highest connectivity. Sequence alignment indicated that ASV2 and ASV4 shared the highest sequence similarity with V. harveyi.

Figure 6

Microbial co-occurrence network analysis. (A) Co-occurrence networks of the intestinal microbiota in H. discus hannai (H0, H12, H32 and H60, relative abundance at least >0.1% in one sample). (B) Comparison chart of ASV sequence and V. harveyi sequence.

4 Discussion

Infections caused by the Vibrio species pose a significant threat to the health of H. discus hannai and the productivity of abalone aquaculture (Wei et al., 2022). Accumulating studies indicate that such infections profoundly disrupt the homeostasis of the host intestinal microbiota, triggering dynamic shifts in community composition and function (Im and Kim, 2020). The intestinal microbiota of mollusks plays a pivotal role in host physiology, encompassing nutritional metabolism, immune modulation, and environmental adaptation. As the most diverse class within Mollusca, gastropods harbor distinct microbial consortia that contribute to host growth, immunity, and host-parasite interactions (Li et al., 2023). In this study, we investigated the temporal dynamics of the intestinal microbiota in H. discus hannai following V. harveyi infection. The results showed that different infection times shaped intestinal microbiota into community profiles. The intestinal microbiota of healthy abalones exhibit a taxonomic composition pattern consistent with that of other mollusks: it is predominantly composed of Tenericutes, Fusobacteria, and Proteobacteria, with Mycoplasma being the most abundant genus at the genus level (Im and Kim, 2020). However, the dominant genera in the intestinal microbiota of H. discus hannai at 32 hpi or 60 hpi post- V. harveyi infection were primarily Paraprevotella and Malaciobacter, respectively. Notable differences were observed in the dominant bacterial taxonomic compositions across different V. harveyi infection times, and these differences became more pronounced over time. The relative abundances of Mycoplasmataceae and Ruminococcaceae were significantly decreased, while those of Vibrionaceae and Fusobacteriaceae were significantly increased at 32 hpi and 60 hpi. Ruminococcaceae are critical for cellulose hydrolysis and short chain fatty acid biosynthesis, which are processes directly linked to intestinal nutrient absorption (Xie et al., 2022). Our results showed that the abundance of Ruminococcaceae was decreased, which indicates impaired cellulose degradation and reduced intestinal feed conversion efficiency (Gu et al., 2021). In addition, within the intestinal microbiota, Vibrionaceae secrete hemolysins and extracellular proteases that degrade intestinal epithelial cells, leading to increased gut permeability and further exacerbating gut dysbiosis (Crowther et al., 1987). Fusobacteriaceae are significantly enriched in the intestines of patients with ulcerative colitis. They induce the polarization of pro-inflammatory M1 macrophages and suppress the anti-inflammatory M2 response by activating the AKT2 signaling pathway in macrophages, thereby exacerbating intestinal inflammation (Liu et al., 2019). The relative abundances of both Vibrionales and Fusobacteriales were significantly increased at 32 hpi and 60 hpi, which may be important contributors to the exacerbated mortality H. discus hannai infected with V. harveyi.

Metagenomic analysis revealed that high-dose V. harveyi infection induces significant alterations in the intestinal microbiota of the host at 24 hpi. Specifically, this infection is associated with a marked reduction in microbial α-diversity, alongside increased relative abundances of bacteria from the genera Vibrio and Shewanella, including multiple potential pathogenic strains (Wu et al., 2024). This study is consistent with the results from our 16S rRNA-based analysis of the intestinal microbiota of H. discus hannai infected with V. harveyi. Additionally, other Vibrio species not only share the same habitat as V. harveyi but also exhibit closer phylogenetic relationships and more similar metabolic profiles. Notably, these fast-growing bacterial species are common and highly pathogenic in aquaculture, such as Profundimonas (Hao et al., 2023), Sulfurimonas (Giraud et al., 2021), Photobacterium (Molari et al., 2023), and Labilibacter (Romalde, 2002). Meanwhile, as the duration of V. harveyi infection or pathogenic bacterial infections increases, H. discus hannai is at high risk of co-infection with other pathogens, particularly other Vibrio species (Figures 4, 5). Following the disruption of intestinal microbiota structure resulting from pathogenic bacterial invasion, a range of potential pathogens acquire the opportunity to proliferate, thereby increasing the risk of co-infection or secondary infection (Kang et al., 2023; Kotob et al., 2016). This also explains why the mortality rate of H. discus hannai and the severity of its infected lesions increase significantly as the duration of V. harveyi infection extends (Figure 1).

5 Conclusions

This study demonstrates that V. harveyi infection reshapes the structure and composition of the intestinal microbiota in H. discus hannai, resulting in distinct microbiota characteristics at different V. harveyi infection time points. In conclusion, acute V. harveyi infection in H. discus hannai disrupts the host’s native intestinal microbiota and drives the explosive proliferation of potential intestinal pathogens—primarily those belonging to the Vibrionaceae and Proteobacteria. Notably, this study focused on a short-term acute infection experiment. Given the widespread distribution of Vibrio species in the aquatic habitats of H. discus hannai, additional studies are required to further elucidate the adaptation and competition between intestinal microbes and pathogens.

Statements

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author/s.

Ethics statement

The animal study was approved by College of Ocean and Biology Engineering, Yancheng Teachers University. The study was conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements.

Author contributions

YL: Data curation, Investigation, Writing – original draft. JC: Investigation, Methodology, Validation, Writing – review & editing. XP: Investigation, Methodology, Validation, Writing – review & editing. RW: Data curation, Formal Analysis, Writing – review & editing. YZ: Funding acquisition, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. This work was supported by the Natural Science Foundation of Shandong Province (No. ZR2022QC037), High-Level Talents Re- search Fund of Qingdao Agricultural University (No. 663/1120033), Shandong Key R&D Program (For Academician team in Shandong): 2023ZLYS02.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to express their sincere thanks to the personnel of these teams for their kind assistance.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript. We used Generative AI to discover relevant publications and check the English grammar. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1

Bars-Cortina D. Moratalla-Navarro F. García-Serrano A. Mach N. Riobó-Mayo L. Vea-Barbany J. et al . (2023). Improving species level-taxonomic assignment from 16S rRNA sequencing technologies. Curr. Protoc.3, e930. doi: 10.1002/cpz1.930

2

Choi M. J. Kim Y. R. Park N. G. Kim C. H. Oh Y. D. Lim H. K. et al . (2022). Characterization of a C-type lectin domain-containing protein with antibacterial activity from pacific abalone (Haliotis discus hannai). Int. J. Mol. Sci.23, 698. doi: 10.3390/ijms23020698

3

Cook P. A. (2019). Worldwide abalone production statistics. J. Shellfish. Res.38, 401–404. doi: 10.2983/035.038.0222

4

Crowther R. S. Roomi N. W. Fahim R. E. Forstner J. F. (1987). Vibrio cholerae metalloproteinase degrades intestinal mucin and facilitates enterotoxin-induced secretion from rat intestine. Biochim. Biophys. Acta924, 393–402. doi: 10.1016/0304-4165(87)90153-X

5

Deng Y. Zhang Y. Chen H. Xu L. Wang Q. Feng J. (2020). Gut-Liver Immune Response and Gut Microbiota Profiling Reveal the Pathogenic Mechanisms of Vibrio harveyi in pearl gentian grouper (Epinephelus lanceolatus♂ × E. fuscoguttatus♀). Front. Immunol.11, 607754. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2020.607754

6

Gan L. Zheng J. Xu W. H. Lin J. Liu J. Zhang Y. et al . (2024). Author Correction: Deciphering the virulent Vibrio harveyi causing spoilage in muscle of aquatic crustacean Litopenaeus vannamei. Sci. Rep.14, 21131. doi: 10.1038/s41598-024-71652-4

7

Giraud C. Callac N. Beauvais M. Mailliez J. R. Ansquer D. Selmaoui-Folcher N. et al . (2021). Potential lineage transmission within the active microbiota of the eggs and the nauplii of the shrimp Litopenaeus stylirostris: possible influence of the rearing water and more. PeerJ9, e12241. doi: 10.7717/peerj.12241

8

Gu X. Sim J. X. Y. Lee W. L. Cui L. Chan Y. F. Z. Chang E. D. et al . (2021). Gut Ruminococcaceae levels at baseline correlate with risk of antibiotic-associated diarrhea. iScience25, 103644. doi: 10.1016/j.isci.2021.103644

9

Hall M. Beiko R. G. (2018). 16S rRNA gene analysis with QIIME2. Methods Mol. Biol.1849, 113–129. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4939-8728-3_8

10

Hao Y. Zhao Y. Zhang Y. Liu Y. Wang G. He Z. et al . (2023). Population response of intestinal microbiota to acute Vibrio alginolyticus infection in half-smooth tongue sole (Cynoglossus semilaevis). Front. Microbiol.14, 1178575. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2023.1178575

11

Hou Y. Zhang T. Zhang F. Liao T. Li Z. (2023). Transcriptome analysis of digestive diverticula of Hong Kong oyster (Crassostrea hongkongesis) infected with Vibrio harveyi. Fish. Shellfish. Immunol.142, 109120. doi: 10.1016/j.fsi.2023.109120

12

Im J. Kim H. S. (2020). Genetic features of Haliotis discus hannai by infection of vibrio and virus. Genes Genomics42, 117–125. doi: 10.1007/s13258-019-00892-w

13

Jiang Q. Shi L. Ke C. You W. Zhao J. (2013). Identification and characterization of Vibrio harveyi associated with diseased abalone Haliotis diversicolor. Dis. Aquat. Organ103, 133–139. doi: 10.3354/dao02572

14

Jiangyong W. Xiushou S. Ruixuan W. Youlu S. (2010). Isolation, identification and phylogenetic analysis of pathogen from Haliotis diversicolor reeve with withering syndrome. South China Fish. Sci.6 (5).

15

Kang Y. H. Yang B. T. Hu R. G. Zhang P. Gu M. Cong W. (2023). Gut microbiota and metabolites may play a crucial role in sea cucumber Apostichopus japonicus aestivation. Microorganisms11, 416. doi: 10.3390/microorganisms11020416

16

Ke H. M. Prachumwat A. Yu C. P. Yang Y. T. Promsri S. Liu K. F. et al . (2017). Comparative genomics of Vibrio campbellii strains and core species of the Vibrio Harveyi clade. Sci. Rep.7, 41394. doi: 10.1038/srep41394

17

Kotob M. H. Menanteau-Ledouble S. Kumar G. Abdelzaher M. El-Matbouli M. (2016). The impact of co-infections on fish: a review. Vet. Res.47, 98. doi: 10.1186/s13567-016-0383-4

18

Lee Y. Roh H. Kim A. Park J. Lee J. Y. Kim Y. J. et al . (2023). Molecular mechanisms underlying the vulnerability of Pacific abalone (Haliotis discus hannai) to Vibrio harveyi infection at higher water temperature. Fish. Shellfish . Immunol.138, 108844. doi: 10.1016/j.fsi.2023.108844

19

Li P. Hong J. Yuan Z. Huang Y. Wu M. Ding T. et al . (2023). Gut microbiota in parasite-transmitting gastropods. Infect. Dis. Poverty.12, 105. doi: 10.1186/s40249-023-01159-z

20

Li Y. N. Zhang X. Huang B. W. Xin L. S. Wang C. M. Bai C. M. (2024). Localization and tissue tropism of ostreid herpesvirus 1 in blood clam anadara broughtonii. Biol. (Basel).13, 720. doi: 10.3390/biology13090720

21

Liu L. Liang L. Liang H. Wang M. Lu B. Xue M. et al . (2019). Fusobacterium nucleatum Aggravates the Progression of Colitis by Regulating M1 Macrophage Polarization via AKT2 Pathway. Front. Immunol.10, 1324. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2019.01324

22

Ma Z. Wu Y. Zhang Y. Zhang W. Jiang M. Shen X. et al . (2024). Morphologic, cytometric, quantitative transcriptomic and functional characterisation provide insights into the haemocyte immune responses of Pacific abalone (Haliotis discus hannai). Front. Immunol.15, 1376911. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2024.1376911

23

Mok K. C. Wingreen N. S. Bassler B. L. (2003). Vibrio harveyi quorum sensing: a coincidence detector for two autoinducers controls gene expression. EMBO J.22, 870–881. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdg085

24

Molari M. Hassenrueck C. Laso-Pérez R. Wegener G. Offre P. Scilipoti S. et al . (2023). A hydrogenotrophic Sulfurimonas is globally abundant in deep-sea oxygen-saturated hydrothermal plumes. Nat. Microbiol.8, 651–665. doi: 10.1038/s41564-023-01342-w

25

Montánchez I. Kaberdin V. R. (2020). Vibrio harveyi: A brief survey of general characteristics and recent epidemiological traits associated with climate change. Mar. Environ. Res.154, 104850. doi: 10.1016/j.marenvres.2019.104850

26

Nurhafizah W. W. I. Lee K. L. Laith A A. R. Nadirah M. Danish-Daniel M. Zainathan S. C. et al . (2021). Virulence properties and pathogenicity of multidrug-resistant Vibrio harveyi associated with luminescent vibriosis in Pacific white shrimp, Penaeus vannamei. J. Invertebr. Pathol.186, 107594. doi: 10.1016/j.jip.2021.107594

27

Okubo H. Nakatsu Y. Sakoda H. Kushiyama A. Fujishiro M. Fukushima T. et al . (2015). Interactive roles of gut microbiota and gastrointestinal motility in the development of inflammatory disorders. Inflammation Cell Signaling2 (1). doi: 10.14800/ics.643

28

Romalde J. L. (2002). Photobacterium damselae subsp. piscicida: an integrated view of a bacterial fish pathogen. Int. Microbiol.5, 3–9. doi: 10.1007/s10123-002-0051-6

29

Sawabe T. Inoue S. Fukui Y. Yoshie K. Nishihara Y. Miura H. (2007). Mass mortality of Japanese abalone Haliotis discus hannai caused by Vibrio harveyi infection. Microbes Environ.22, 300–308. doi: 10.1264/jsme2.22.300

30

Singh B. K. Thakur K. Kumari H. Mahajan D. Sharma D. Sharma A. K. et al . (2025). Kumar R. A review on comparative analysis of marine and freshwater fish gut microbiomes: insights into environmental impact on gut microbiota. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol.101, fiae169. doi: 10.1093/femsec/fiae169

31

Travers M. A. Le Goïc N. Huchette S. Koken M. Paillard C. (2008). Summer immune depression associated with increased susceptibility of the European abalone, Haliotis tuberculata to Vibrio harveyi infection. Fish. Shellfish. Immunol.25, 800–808. doi: 10.1016/j.fsi.2008.08.003

32

Wei J. Zhang X. Yang F. Shi X. Wang X. Chen R. et al . (2022). Gut microbiome changes in anti-N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor encephalitis patients. BMC Neurol.22, 276. doi: 10.1186/s12883-022-02804-0

33

Whyte S. K. (2007). The innate immune response of finfish–a review of current knowledge. Fish. Shellfish. Immunol.23, 1127–1151. doi: 10.1016/j.fsi.2007.06.005

34

Wu N. Song Y. L. Wang B. Zhang X. Y. Zhang X. J. Wang Y. L. et al . (2016). Fish gut-liver immunity during homeostasis or inflammation revealed by integrative transcriptome and proteome studies. Sci. Rep.6, 36048. doi: 10.1038/srep36048

35

Wu Z. Yu X. Chen P. Pan M. Liu J. Sahandi J. et al . (2024). Dietary Clostridium autoethanogenum protein has dose-dependent influence on the gut microbiota, immunity, inflammation and disease resistance of abalone Haliotis discus hannai. Fish. Shellfish. Immunol.151, 109737. doi: 10.1016/j.fsi.2024.109737

36

Xie J. Li L. F. Dai T. Y. Qi X. Wang Y. Zheng T. Z. et al . (2022). Short-chain fatty acids produced by Ruminococcaceae mediate α-Linolenic acid promote intestinal stem cells proliferation. Mol. Nutr. Food Res.66, e2100408. doi: 10.1002/mnfr.202100408

37

Yang W. Cong Y. (2021). Gut microbiota-derived metabolites in the regulation of host immune responses and immune-related inflammatory diseases. Cell Mol. Immunol.18, 866–877. doi: 10.1038/s41423-021-00661-4

38

Yang Y. Yu H. Li H. Wang A. (2016). Transcriptome profiling of grass carp (Ctenopharyngodon idellus) infected with Aeromonas hydrophila. Fish. Shellfish . Immunol.51, 329–336. doi: 10.1016/j.fsi.2016.02.035

39

Zhang Y. Wu F. Yang G. Jian J. Lu Y. Wang Z. (2023). Molecular and functional characterization of α chain of interleukin-15 receptor (IL-15Rα) in orange-spotted grouper (Epinephelus coioides) in response to Vibrio harveyi challenge. Anim. (Basel).13, 3641. doi: 10.3390/ani13233641

Summary

Keywords

Vibrio harveyi , Haliotis discus hannai , intestinal microbiota, infection progress, 16S rRNA gene sequencing

Citation

Li Y, Chen J, Pan X, Wang R and Zhu Y (2025) Exploring the infection process of Haliotis discus hannai to Vibrio harveyi based on changes in intestinal microbiota. Front. Mar. Sci. 12:1725327. doi: 10.3389/fmars.2025.1725327

Received

15 October 2025

Revised

01 November 2025

Accepted

06 November 2025

Published

24 November 2025

Volume

12 - 2025

Edited by

Pengsheng Dong, Henan Agricultural University, China

Reviewed by

Yu-qing Xia, Dalian Ocean University, China

Xiuxiu Li, Henan Normal University, China

Updates

Copyright

© 2025 Li, Chen, Pan, Wang and Zhu.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Ying Zhu, zhuying@qau.edu.cn

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.