Abstract

Marine litter is composed of various types of debris and poses a significant risk to marine ecosystems, biodiversity, and human life. Effective management and mitigation measures of marine litter, otherwise known as marine waste, can only be achieved through proper classification. The paper presents a new method based on panoptic segmentation and vision transformer (ViT) to perform the overall classification of marine litter. Panoptic segmentation, developed by synthesizing instance and semantic segmentation, can be used to identify both marine litter objects and background objects simultaneously. The image quality is added, and noise removal is provided to the raw input images to provide optimal input to the analysis. With the help of the panoptic segmentation model and a Vision Transformer, marine litter images are divided into semantically coherent segments, which can then be classified and located accurately and reliably as debris objects. Analysis on different datasets has shown good results, and both the quantitative and qualitative analyses support the usefulness of the methodology. These objectives include improving the levels of detection, localization of different kinds of debris under challenging marine environments, and comparing the effectiveness of the technique with the current ones. The proposed methodology can give valuable information regarding marine waste distribution and organization. The approach enables rational decision-making in protecting and managing pollution. Panoptic segmentation is an effective method that can be used in future studies and implementation in marine litter monitoring and mitigation due to its scalability and flexibility.

1 Introduction

Marine litter is a universal and escalating worldwide problem that poses serious threats to the health of the ocean, biodiversity, and the health of humans. The sources of plastic debris in marine litter are numerous because they arise from land-based work, maritime work, and marine transportation. They end up being deposited on coastal waters, open waters, and secluded seas (Freitas et al., 2021; Politikos et al., 2021). The marine litter is a broad term that comprises all types of anthropogenic waste, starting with the macro level (greater than 2.5cm) products such as plastic bottles, fishing gears, abandoned vessels, etc. These macro litter particles continue breaking down to microscopic-sized litter like microplastics and nano plastics (Merlino et al., 2021). Such a variety of debris is a complicated threat to the marine environment, animals, and human beings (Kylili et al., 2021). The dangerous impact of litter is especially dangerous to marine organisms, such as entangling, consuming, and destroying habitats. The most prevalent effect of marine litter is chemical contamination. The inflow of marine litter continues even with increased awareness and international attempts at curbing this vice. Therefore, it is critical to require creative methods to be able to manage and control its effects.

Marine litter has great ecological effects and has an impact on the marine life at all trophic levels. It is also interfering with the operations of the ecosystem. Marines usually confuse litter materials with food, causing inner injuries, obstruction of digestive tract, undernourishment, and death (Gonçalves et al., 2020; Balsi et al., 2021). In addition, plastics in the ocean act as carriers of toxic substances. Adsorbing and concentrating such toxic material as polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs), polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAH), and heavy metals (Freitas et al., 2022). These pollutants have the potential to bioaccumulate up the food chain and cause threats to marine ecology and health of human beings.

Marine litter has serious economic and social issues as well as environmental impacts. The so-called ghost gear, or lost or abandoned fishing equipment, still fishes blindly, becoming a source of ghost fishing, which results in empty fish stocks and destroys habitats. It goes to the extent of questioning the sustainable fisheries management by the government (Escobar-Sánchez et al., 2022). In addition, the aesthetic of the beaches and the shorelines is also minimized by presence of marine litter, which provides fewer recreational activities, and it negatively impacts tourism.

The resolution of the marine litter crisis should be taken in concerted and multidimensional approaches, and they can be classified as prevention, mitigation facets, cleanup and monitoring. Among them is marine litter classification, which is a major aspect of comprehending the delicateness, distribution and origin of marine litter. It also enables specific interventions and policy actions of the marine ecosystem (Kremezi et al., 2021). Classification techniques can be used to identify and quantify the types of litter materials by different attributes in terms of material, size, shape and origin (Taggio et al., 2022; Corrigan et al., 2023).

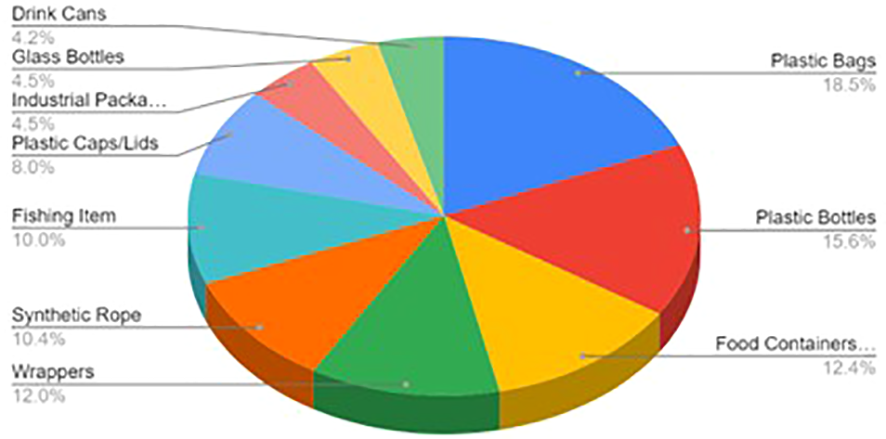

The classification of marine litter gives a very crucial overview of the problem in nature and magnitude. The largest part of marine litter is plastic waste, and it is the one that includes the vast majority of the total, comprising plastic bottles, bags, and packaging, as well as the fisheries equipment and micro-level plastics. Metal (10%), mostly cans and metal containers, glass (5%), bottles, and fragments of glass, rubber (4%), tyers, and other rubber products, paper (3%), e.g. newspapers, cardboard and textiles (3%) including clothing, ropes and other fabric products are other important categories of marine litter. The distribution of marine litter categories considered in this study is illustrated in Figure 1. The size distribution of marine litter is very wide, with most of the macro-litter being plastic bottles as well as large debris and constituting approximately 55 per cent of the whole. Meso-litter, which is between 5 mm and 25 mm in size, i.e. bottle caps and small pieces, is 30 per cent, with micro-litter, which is less than 5 mm in size, accounting for 15 per cent.

Figure 1

Litter categories in the Ocean, Source: AquaTrash dataset (Dataset collected from: https://github.com/Harsh9524/AquaTrash/tree/master/, [[NoYear]]).

Marine waste sources are varied, but the land-related activities contribute about 80 per cent of the total. These are runoffs in urban areas, landfills and beach activities. The rest of the 20% is attributed to ocean-based, which are mostly a result of fishing vessels, shipping activities and offshore platforms. The distribution patterns of geographic data show that there are high concentrations of marine litter along the coastal waters, which are specifically adjacent to urban areas, river mouths and beaches (Garcia-Garin et al., 2021). The accumulation of litter is also present in open oceans in the form of gyres, most of which lie in the Great Pacific Garbage Patch. The effects of marine litter are also not exempt from even the remote marine environments where human beings cannot be found, such as the Arctic and the deep-sea areas. Marine litter is extremely dangerous to marine animals, and there are many cases of entanglement and ingestion that are reported. Having these incidents normally leads to injuries, starvation, and death of marine organisms such as turtles, birds, and fish. Moreover, plastics within the oceanic system take in the toxicants PCBs, PAHs, and heavy metals, which can be carried up the food chain, posing additional hazards to the marine life and health (Armitage et al., 2022; Hidaka et al., 2022). The social and economic effects of marine litter are also high. Lost or abandoned fishing equipment leads to ghost fishing, which incurs an estimated loss of $ 250 million per year all over the world. In addition to that, marine debris on the beaches and the coastal waters also decreases the aesthetic qualities of the beaches, and thus, there is a reported 50 per cent decline in the tourism income in the regions that are affected by it.

The recent sea incidents, the 2025 Toconao at sea accident on the waters surrounding Spain and Portugal, indicate the urgency to have powerful litter monitoring and response systems. The discharge of plastic particles (microplastics) in this accident caused serious ecological damage and emergency mobilisation (Cocozza et al., 2025). The incident underscores the need to develop superior and real-time detection and classification systems that are able to facilitate chronic pollution and real-time disaster management.

Recent technology, especially in the areas of artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning (ML), and computer vision, could be used to improve the accuracy and efficiency of marine litter classification. The machine classification algorithms can process massive amounts of marine videos and images in the form of satellite, drone, and underwater vehicles. It can also be used to quickly and cost-effectively evaluate the distribution and abundance of marine litter (Themistocleous et al., 2020). The paper has made its contributions as below,

-

In this research, a new method of marine litter categorization is proposed based on the panoptic segmentation methods when marine litter objects and the background objects are searched in the same image.

-

The proposed methodology is more accurate and precise in the classification and localization of marine garbage types due to the use of panoptic segmentation. And also presents some useful observations on their dispersion and structure.

-

The usefulness of the methodology is strictly proved and tested based on the various types of datasets that had litter images of different kinds. It uses quantitative measures, e.g. precision, recall, and F1 score, and also qualitative analysis as visual inspection and comparison with ground truth annotations.

-

The research results are relevant in the process of informed decision-making in conservation and pollution control activities in the marine setting because the results offer comprehensive data on the pattern and nature of marine litter, thus contributing to the specific intervention measures and policy-making.

The main missions are to increase the accuracy and precision of debris detection and classification in various marine conditions and to make it easier to identify litter objects and background objects at the same time. Strict assessment based on quantitative and qualitative measurements will be done over the dataset to confirm the suggested method. The study aims to fill gaps in current approaches regarding scalability, generalization, and applicability in real-time. And with some valuable information on the effective marine pollution monitoring and management. The other part of the paper is structured in the following manner. Part II includes the problem statement and the list of works that are relevant. Section III gives and describes the proposed protocol. Subsequently, part IV contains the findings and discussion, and the conclusion is found in section V.

2 Literature review

Recent developments in marine litter detection have also shown considerable improvements in methodology as well as implementation, where a dynamic interface between remote sensing, deep learning, and autonomous monitoring is dynamic.

In the study by Kremezi et al (Kremezi et al., 2022), the fusion methods are discussed in order to differentiate plastics and seawater via synchronized spectral acquisition. This method is a hybrid of component substitution, spectral unmixing and deep learning methods in detecting litter. Their analysis in various WV-2/3 band combinations and litter indexes is quite striking, as it is important to optimize spectral and spatial information in order to identify plastics correctly.

Advances in automated image analysis are depicted by Pinto et al (Pinto et al., 2021), who developed a multiclass Neural Network to recognize autonomously abandoned plastic rubbish in UAS-generated orthophotos. Their analysis has suggested the utility of color-based methods in categorical classification, particularly of objects where there is little color difference. It is a big step forward in the mapping of marine litter by drones, which makes use of the Ortho mosaic images.

Deng et al (Deng et al., 2021). provide improvements to instance segmentation frameworks by adding the dilated convolution and spatial-channel attention to a better version of the Mask R-CNN architecture. Their approach to the issue is based on training on the Transcan dataset and, therefore, considers the limitations of low-resolution underwater images. This model is able to provide the enhanced feature extraction and segmentation performance that is important in object detection in the marine setting. Mask R-CNN aims at instance segmentation and object detection, two important aspects in marine litter detection.

Knowledge of the automatic detection of litter items on sandy beaches is introduced by a recent study by Sozio et al. (2025), introducing a novel tool based on SAM-ViT. It is a combination of Segment Anything Model (SAM) and a Vision Transformer backbone. This design resembles the design used in my proposed study, where the feature extraction using transformers is incorporated with panoptic segmentation. The application of SAM allows segmentation performance that is highly generalizable, whereas ViT is the best at comprehending global context. And ViT proves to be better adapted to varying coastal conditions characterised by blocked and submerged images (Sozio et al., 2024a).

Environmental surveillance has gone a step further as Farré et al (Farré, 2020). indicated through the implementation of autonomous systems such as drones to collect data, conduct monitoring remotely, and create spatial maps of contaminant spills. Such approaches underpin the overall objectives of the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDG) and precondition sustainable ocean pollution control on a large scale. The oil spills are largely surveyed using drone pictures. These attempts were continued by Goncalves et al. (2020), who used Unmanned Aerial Systems (UAS) with photogrammetry, geomorphology, machine learning, and hydrodynamic modelling. The above technique establishes a multidisciplinary model for effective litter mapping in coastal areas.

The lifecycle and impact assessment of marine litter is also discussed in the present-day research. The Woods et al (Woods et al., 2021). conducted a complex LCIA (Life Cycle Impact Assessment) model of the sources of marine plastic litter to the environment, which helps to coordinate the work of other researchers to comprehend and reduce the influence of environmental pollution by plastic waste on nature. Being aware of overfitting as the major problem, Nagy et al (Nagy et al., 2022). proposed to apply synthetic data that is just images created with the help of AI algorithms to support the improvement of model generalisation. The synthetic image generation can frequently be done using the GAN model through these methods. Their virtual data sets are useful in training machine learning models, making it possible to successfully transfer algorithms to detect automatic pollution in real satellite images.

Recent developments in deep learning are concerned with the efficiency of resources and real-time performance. The article by Huang et al (Huang et al., 2023). describes the formation of the lightweight neural network called DSDebrisNet and the corresponding dataset that allows detecting underwater debris quickly and efficiently. In the same manner, Ma et al (Ma et al., 2023). introduced a powerful object detector, MLDet, which was more effective than the existing methods and highlighted the importance of automation, which promotes waste recovery and ocean conservation. Ren et al (Ren et al., 2021). emphasise the scientific progress in the framework of detecting objects, revealing a deep convolutional neural network built on the Faster R-CNN. As it was stated above Faster R-CNN model is concentrated on the detection of objects. The combined use of multi-scale fusion and fine-grained semantic extraction, parameter optimisation and data augmentation makes their method extremely accurate in waste detection of small and subtle marine debris.

Recent research has provided efficiency comparisons of the direct survey, nothing but physical survey and the indirect methodology, such as image-based and ML-based approaches on detecting litter on beaches. As a case in point, Sozio et al. (2024) examine the advantages and disadvantages of classical ML algorithms, such as SVM and Mask-RCNN, based on manual and UAV-based surveys, in great detail. Their results point to the problem of detection in hard-to-find coastal conditions. Thus, we are putting the emphasis on the need for strong deep learning models followed in the current study. The inclusion of these insights into the discussion also explains why the proposed Vision Transformer approach is superior and has more practical benefits in the context of large-scale and automated litter mapping (Sozio et al., 2024b).

Overall, all these studies focus on the key issues in marine litter detection, such as enhancing detection accuracy, deploying optimised models to the real-world setting, preventing overfitting, and automated monitoring. Nevertheless, there are still shortcomings in field validation and even integration of various data sources of satellite and drone operations. Our current work is based on this rich background, with the addition of the application of Vision Transformers and panoptic segmentation algorithms to improve mapping the marine litter even more.

Based on the Literature study, the primary significant gap would be the absence of real-time detecting and processing possibilities. The majority of works are devoted to the post-processing techniques in the context of which immediate response and action are pre-empted. Most of the suggested solutions cannot be easily scaled, which restricts their ability to provide a wide and large area of the marine environment. This discourages mass implementation and tracking. In many cases, field validation on different and nonspecialized conditions is not adequate, and one is left wondering how strong and reliable the suggested methods are in practice. So little connection with autonomous monitoring and data acquisition systems. The a necessity to have some common structures and guidelines when assessing and comparing various methods.

2.1 Problem statement

The research has had a number of problems as it was developing and implementing the methodology proposed for marine litter classification. To start with, it was not an easy task to guarantee the quality and consistency of marine litter imagery of varying datasets and under varying environmental conditions. The inconsistency of image resolution, lighting and debris types necessitated sound preprocessing algorithms that would help in improving the quality of the image and eliminating undesired noise. Second, there was a difficulty in the creation and application of panoptic algorithms of segmentation with high computational efficiency and scalability, especially in a large-scale marine litter dataset. The trade-off between complexity of the algorithm and optimization of its performance was to be considered carefully and experimented with. Also, the subjectivity of the process of classifying types of marine litter and the laboriousness of manual annotation tasks posed a problem in generating proper ground truth annotations to train and evaluate the proposed approaches. Lastly, it was necessary to guarantee that the applied methodology could be generalised and applicable within various coastal settings and geographical locations, through the wide-scale testing and validation to determine the level of robustness and reliability of the approach at application scales.

3 Proposed methodology

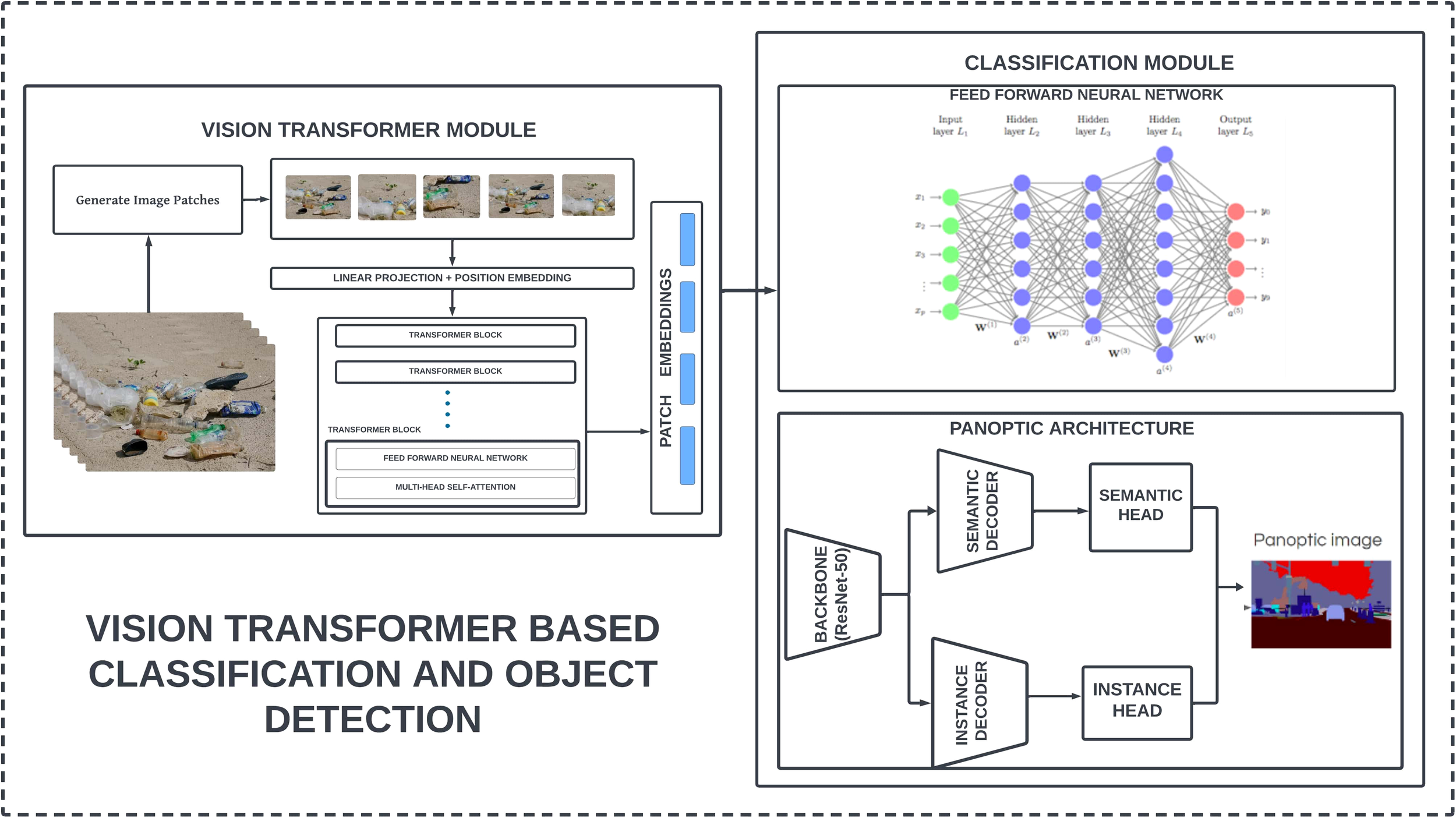

The classification of marine litter involves the use of very sophisticated methods, such as panoptic segmentation, to determine and classify types of rubbish in the ocean. This approach consists of instance and semantic segmentation, which allows recognising litter items and the surrounding features at the same time. The issues encountered comprise variability of data, complexity of algorithms and ground truth annotation, which do not support the successful classification and localisation of marine debris. Our paper introduces a novel approach with the set of panoptic segmentation and vision transformer to the comprehensive classification of marine litter. The general proposed architecture is shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2

Proposed Architecture for Marine Litter Classification using a vision transformer and the panoptic segmentation.

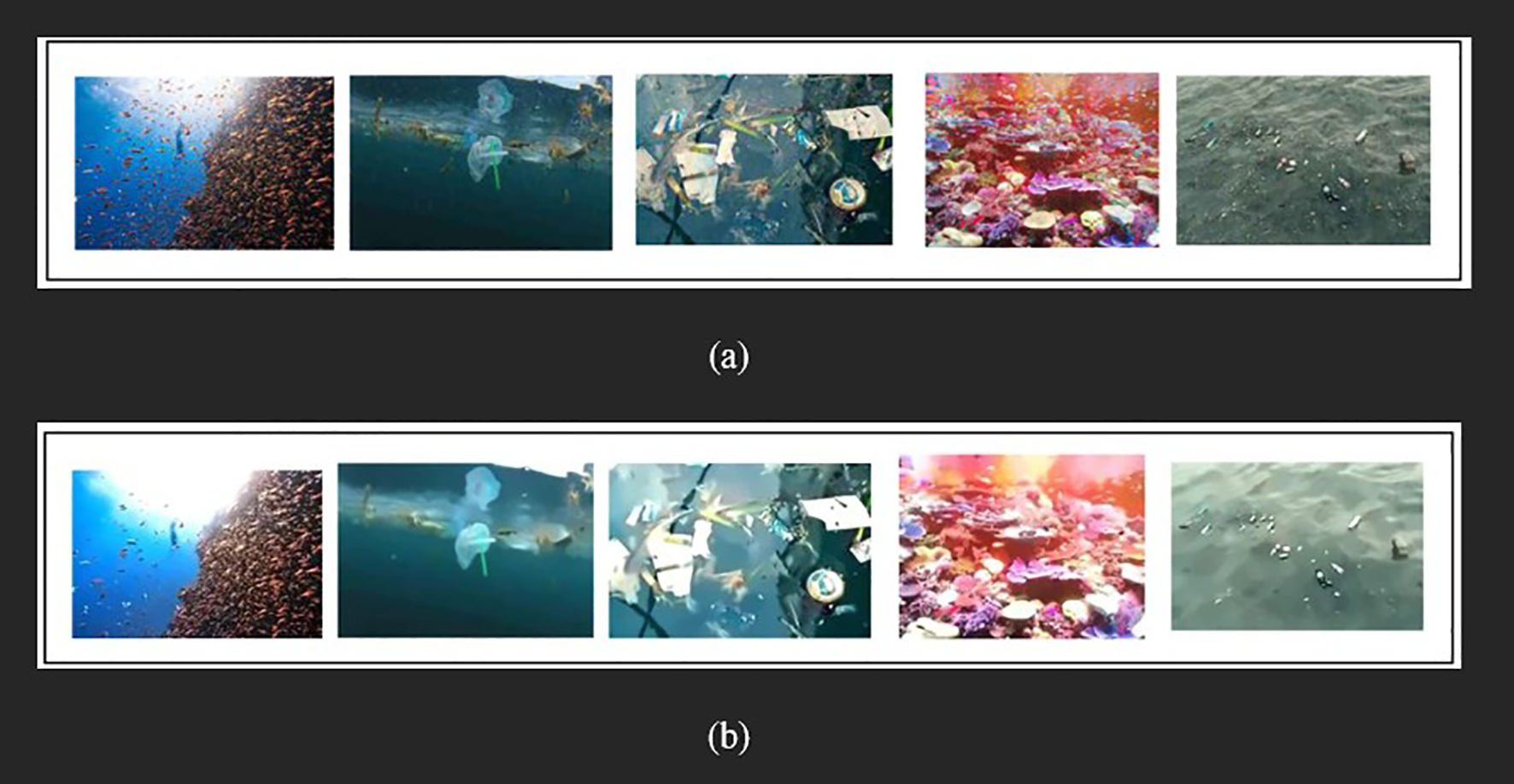

3.1 Pre-processing

The preprocessing stage involved methods to improve the quality of marine litter image and eliminate noise, which is undesirable to maximise the input of the next processing phase. Image improvement entailed modifying the parameters of brightness, contrast, and sharpness, among others, to increase the overall image clarity and visibility of marine litter constituents. This pre-processing was to improve the disparity of litter items in the background. Such a procedure enhances the precision of the further segmentation and classification activities. Further, noise-cancelling methods were used to remove undesired artefacts and distractions in the picture. This entailed the use of filters and algorithms that had the effect of reducing noise and leaving behind significant image characteristics. The preprocessing step was beneficial in case of noise reduction, which would improve the signal-to-noise ratio and increase the credibility of the analysis results in general. The preprocessing phase was critical to achieving the quality of the marine litter image to provide a background for proper and efficient classification. The preprocessing phase was a success that made the methodology successful in identifying and classifying marine litter items in the image accurately due to noise reduction and an improvement in the quality of images. It entails a few important activities like de-noising, blurring and sharpening. All these are required steps involved in preparing the image prior to it being fed into machine learning model depicted in Figure 3.

Figure 3

Shows the transformation of images through pre-processing techniques: (a) displays the original, unprocessed images, and (b) presents the images after de-noising, blurring, and sharpening for enhanced clarity.

3.1.1 De-noising

Noise is the unwanted outcome that is removed in images. During image capture, noise may be added under different circumstances, including low-light environments and sensor flaws. De-noising aims to enhance the quality of the image by reducing the noise while preserving important details. In this proposed methodology, a Gaussian filter is used for the denoising.

• Gaussian Filter

A common technique for denoising is the Gaussian filter, which smooths the image by averaging the pixel values with a Gaussian kernel. The Gaussian filter can be represented mathematically as per Equation 1.

Where is the standard deviation of the Gaussian distribution.

3.1.2 Blurring

Blurring is used to reduce image details and smooth transitions. It is often used to remove small details and noise, and can also serve as a preprocessing step for other image processing tasks like edge detection. Here Gaussian blur technique is used for the smoothing effect.

• Gaussian Blur

Gaussian blur is a specific type of blurring using the Gaussian function, similar to de-noising but applied to achieve a broader smoothing effect. The Gaussian blur uses the same Gaussian function as the de-noising step, but applied over a larger kernel size as per Equation 2.

3.1.3 Sharpening

Sharpening enhances the edges and improves the fine details in an image. It is the process of highlighting edges and fine details that might have been lost or blurred in previous steps or during image capture.

• Unsharp Masking

One popular sharpening technique is unsharp masking, which enhances the contrast of edges by subtracting a blurred version of the image from the original image can be represented mathematically as per Equation 3.

where, is the sharpened image, is the original image, is the blurred image, is a scaling factor that controls the strength of sharpening.

3.2 Object detection

In this work, vision transformers employ self-attention mechanisms for object detection, breaking images into patches initially. Panoptic segmentation then differentiates the foreground objects from the background context. NLP analyses such patches, giving objects the labels. This combined method enjoys the strength of computer vision as well as natural language processing to comprehend images more easily.

3.2.1 Vision transformers

Based on the massive success of transformer models in Natural Language Processing (NLP), Vision Transformers (ViT) are a transformational approach to addressing image-related classification problems. ViT is a direct implementation of the key concepts of transformer architecture to image data with minor modifications. It begins with the breaking down of the input image into patches, in the case of sentences tokens of NLP. Every patch itself is linearly transformed to an embedding in a lower dimensionality. These patch embeddings in the form of a sequence are the inputs to the transformer model. In the transformer, the patch sequence that is embedded is fed through a series of layers of Multiple Head Self-Attention (MHA) modules and the Feed-forward Neural Networks (MLP). This enables the model to learn complicated spatial relationships and hierarchical attributes in the image. Mathematically, attention scores are multiplied by the value vectors and added with attention scores to get attention output. This may be expressed as shown in the form of Equation 4.

Iterative processing of the attention output is done in transformer layers, which refine the image representation at each step. At every layer, the sequence is trained with Layer Normalisation and MHA and MLP modules. A linear layer is used on the CLS token embedding to obtain the final output in the form of class probabilities. This equation of prediction heads may be written as in Equation 5.

These are the equations that define ViT, which is the interaction of attention mechanisms and transformer encoders to extract complex spatial relationships. The model can work with various sections of the image at the same time, owing to the MHA mechanism, which helps in grasping the global context. The embedded patch matrix is passed through the transformer encoder layers, and in a process of iteration, the patch image approximation is enhanced with each new step. ViT model outputs a result that is acquired by appending a prediction head to the encoder output. This prediction head, which is generally a linear layer, generates the probability of the classes, and it is a mapping of the encoded image representation to the required output space. The weights and biases used in the prediction head also need to be learned in the training process. Altogether, ViT is a strong paradigm change in computer vision, which utilises transformer scalability and generality to demonstrate the state-of-the-art performance on a broad spectrum of image recognition tasks.

Convolutional Neural Networks (CNN) and Vision Transformers (ViT) have little to nothing in common with the style of processing images. CNNs rely on convolutional layers as a way of extracting local features, which pick simple patterns in the lower layers and complex ones in higher layers. They are effective with smaller images and simpler tasks and enjoy a great deal of strong inductive biases, making them effective with fewer data. ViT, in its turn, splits the image into patches and captures the global relationships with the help of self-attention mechanisms at the very beginning. The benefit of this method is that it enables one to see a larger portion of the image, but it also needs larger datasets and more computing power to accomplish the detection. Whereas CNNs are better adapted to tasks focusing on local features, conversely, ViT is better at tasks that require a global view, and it can be significantly more competitive with large-scale data.

3.2.2 Panoptic segmentation

Panoptic segmentation (PS) is a hybrid between the semantic and instance segmentation, which labels each pixel with a category and a distinct ID, differentiating between the stuff and things. PS, introduced by Kirillov et al., goes forth to give a semantic class and an instance ID to each pixel of the image. The image that results gives a comprehensive picture of elements of the scene. Although PS and Semantic Segmentation (SS) are similar in that they are both designed to provide the semantic label of the pixels, PS is differentiated by the fact that it assigns instance IDs as well. In contrast to instance segmentation (IS), in which the segmentation overlap can occur, PS makes every pixel possess a unique semantic label and instance ID. It aids in different computer vision applications, such as medical imaging and self-driving.

PS, a combined segmentation task of Semantic and Instance segmentation, and contains the performance measures previously calculated as separate ones. It has 3 significant measures, namely Panoptic Quality (PQ), Segmentation Quality (SQ), and Recognition Quality (RQ). PQ is used to determine the quality of PS in comparison with ground truth by segment matching. SQ calculates Intersection over Union (IoU) score. RQ estimates quality in identification scenarios, considering segments matching only if IoU exceeds 0.5. The formula for the Intersection over Union (IoU) score is given as per Equation 6.

and represent the ground truth and predicted segments, respectively. Panoptic Quality (PQ) is computed for each class independently, then averaged across all classes. Unique matching categorises predicted and ground truth segments into true-positives (TPs), false-positives (FPs), and false-negatives (FNs).

PQ is calculated as the sum of IoU for matched segments divided by the total number of true positives (TP), false positives (FP), and false negatives (FN), including a penalty term to account for unmatched segments. Each segment receives equal consideration regardless of its area. PQ can be expressed as the product of Segmentation Quality (SQ) and Recognition Quality (RQ), where SQ measures the IoU of matched segments and RQ accounts for true positives as per Equation 7. PQ = SQ × RQ. However, SQ and RQ are not independent, as SQ is only measured over matched segments. Additionally, consideration of void regions and groups of instances is valuable.

Several remarkable achievements in PS have emerged, each offering unique contributions to the field. The Panoptic Feature Pyramid Network (P-FPN) integrates SS and IS tasks by combining Mask R-CNN with a shared Feature Pyramid Network (FPN). This architecture allows the multi-scale feature to be extracted, boosting the object detection and segmentation processes. The Attention-Guided Unified Network is considered to deal with both the foreground and background segmentation, incorporates region proposal networks (RPN) and pixel-level attention. Using foreground cues, this network attains a constant increase in accuracy on the foreground and the background segmentation. Panoptic DeepLab is trained on dense prediction of atrous convolution, atrous spatial pyramid pooling, and object boundary localisation. The Panoptic DeepLab results in the high accuracy of localisation of object boundaries through a combination of deep convolutional neural networks (NNs) with probabilistic graphical models, enhancing the performance of segmentation. Seamless image Segmentation proposes a convolutional NN framework that jointly incorporates both multi-scale and contextual features. Through a common execution of semantic and instance segmentation activities, this architecture yields state-of-the-art outcomes on different datasets, such as Cityscapes and Mapillary Vistas.

Our methodology is novel when compared directly with Sozio et al. (2025) through architectural analogy. Although SAM is considered a strong transferability with flexible segmentation, we implement the Panoptic Segmentation. Suggested model more strongly targeted the specific issues of marine litter, such as buried litter, managing complex beach features, and desensitising to particular material types (Sozio et al., 2024a).

The suggested panoptic segmentation, which includes a special marine debris classifier (PS + ViT), enables greater discrimination, more instance-oriented mapping, and higher use of annotated datasets than the generic one provided by SAM. The description of these differences not only positions our study at the forefront of transformer-segmentation architectures but also highlights the particular innovations and contributions that our proposed system brings to the table.

Unified Panoptic Segmentation Network uses a special convolution head to solve PS tasks. This network extends the reasoning of semantic and instance segmentation heads, resolving the issues of instance variation and allowing end-to-end backpropagation to make faster inferences. Efficient Panoptic Segmentation presents a common backbone structure with semantic and instance heads to bring about a seamless panoptic segmentation result. This architecture proves useful in different datasets due to its ability to combine fine contextual features and use Mask R-CNN.

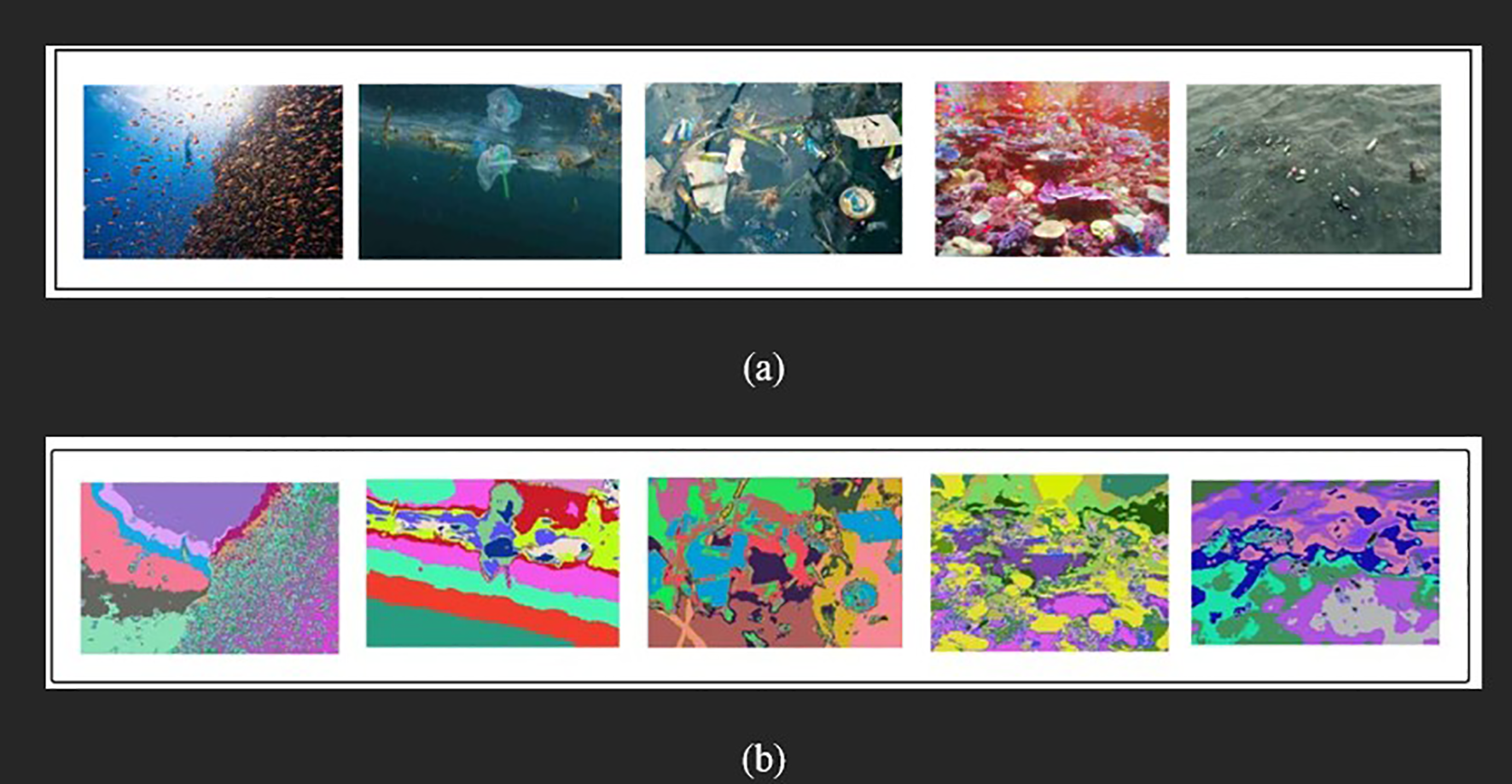

Figure 4 provides the stages of marine litter classification pre-processing. Subfigure (a) presents the original photos taken in marine settings, and they represent different kinds of litter. The same images are introduced in subfigure (b) following Papnotic segmentation technique, which is used to emphasise and isolate litter items in the background to facilitate analysis.

Figure 4

(a) Original images (b) Panoptic Segmented images.

4 Result and discussion

The suggested model is executed on Python platform. The effectiveness of the proposed model in the marine litter classification can be analysed by comparing the measures of performance, i.e., accuracy, precision, recall, and f1-score, which would help to understand the benefit of the proposed model over the current procedures.

4.1 Dataset collection

AquaTrash dataset (Dataset collected from: https://github.com/Harsh9524/AquaTrash/tree/master/, [[NoYear]]), which is one of the components of the AquaVision project, is a collection of 369 images employed to train the deep learning model to identify waste in water bodies. The images get labelled manually, and thus, there are 470 bounding boxes in four classes, namely: glass, paper, metal and plastic. The coordinates of the bounding boxes of each image are described in the annotations.csv file, which contains annotations. The data can be used in the study of waste management and aquatic life protection by having correctly labelled pictures. The photos are published under the licence of the CC BY 4.0 by Pedro F Proença and Pedro Simões, and the annotations are also under the same licence. The dataset is also open source, which motivates the expansion of automated waste detection technology through the deep learning approach.

4.2 Graphical representation

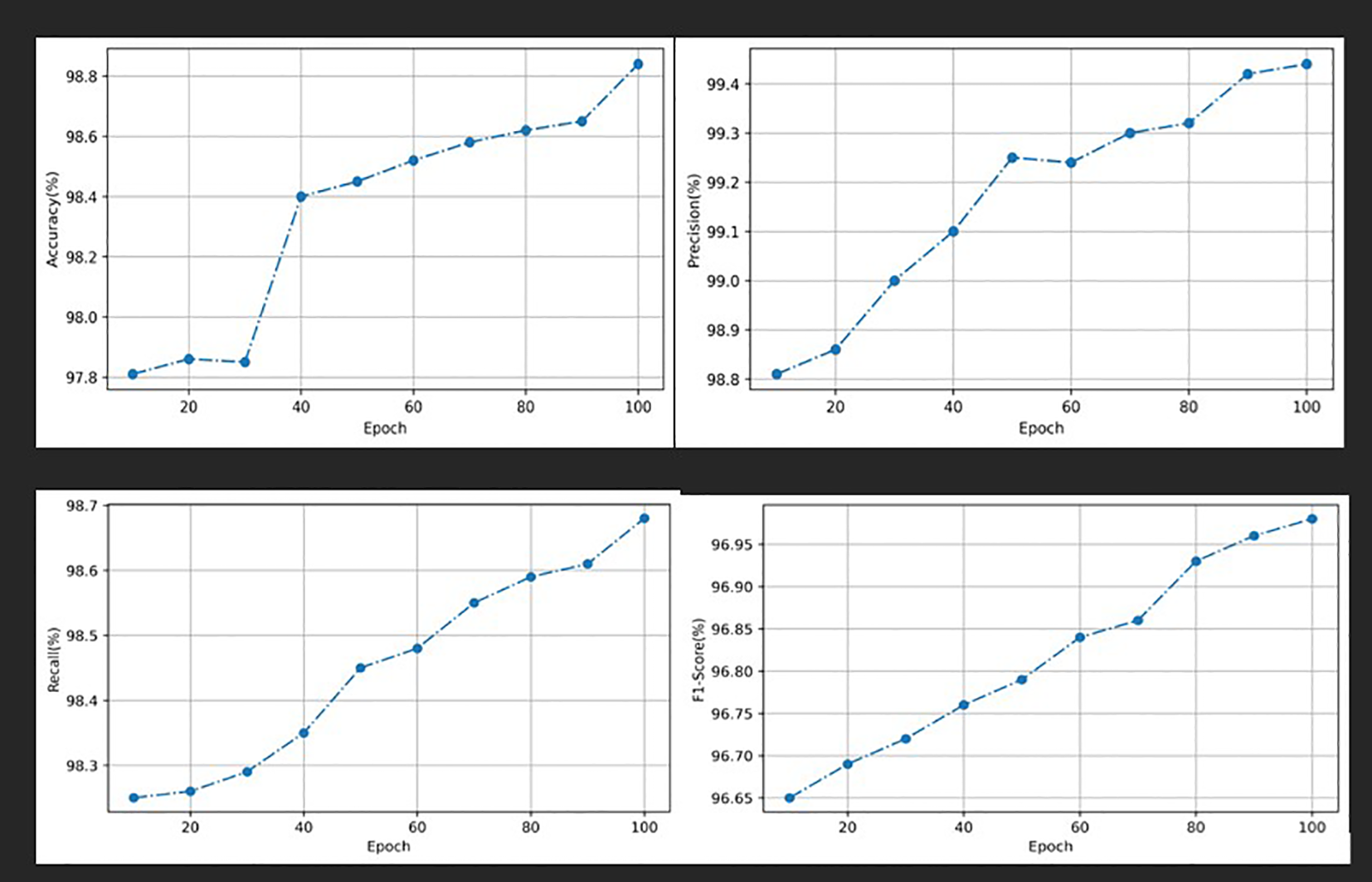

Figure 5 represents the graphical representation of the performance metrics that change with epoch. Probably, it represents the metrics of accuracy, precision, recall, or F1-score as a function of training epochs used to optimise a model. The given visualisation helps track the model’s progress during training cycles and calculate convergence. The fluctuations in these metrics are analysed to optimise training strategies, overfitting or underfitting, and due to them, the most appropriate model checkpoints can be chosen. This knowledge is essential in the development of machine learning models in multiple fields, which guarantee high-level performance and extrapolation to previously unknown data.

Figure 5

Graphical representation of performance metrics varying by epoch.

Figure 6 demonstrates object detection using Vision Transformer, which emphasises object detection. The original images contain beach litter, display processed images, which could be sharpened or feature extracted. This shows the findings of object detection using panoptic and Vision transformers. It allows the interpretation of spaces and makes the interpretation of scenes more correct.

Figure 6

Object detection with vision transformer.

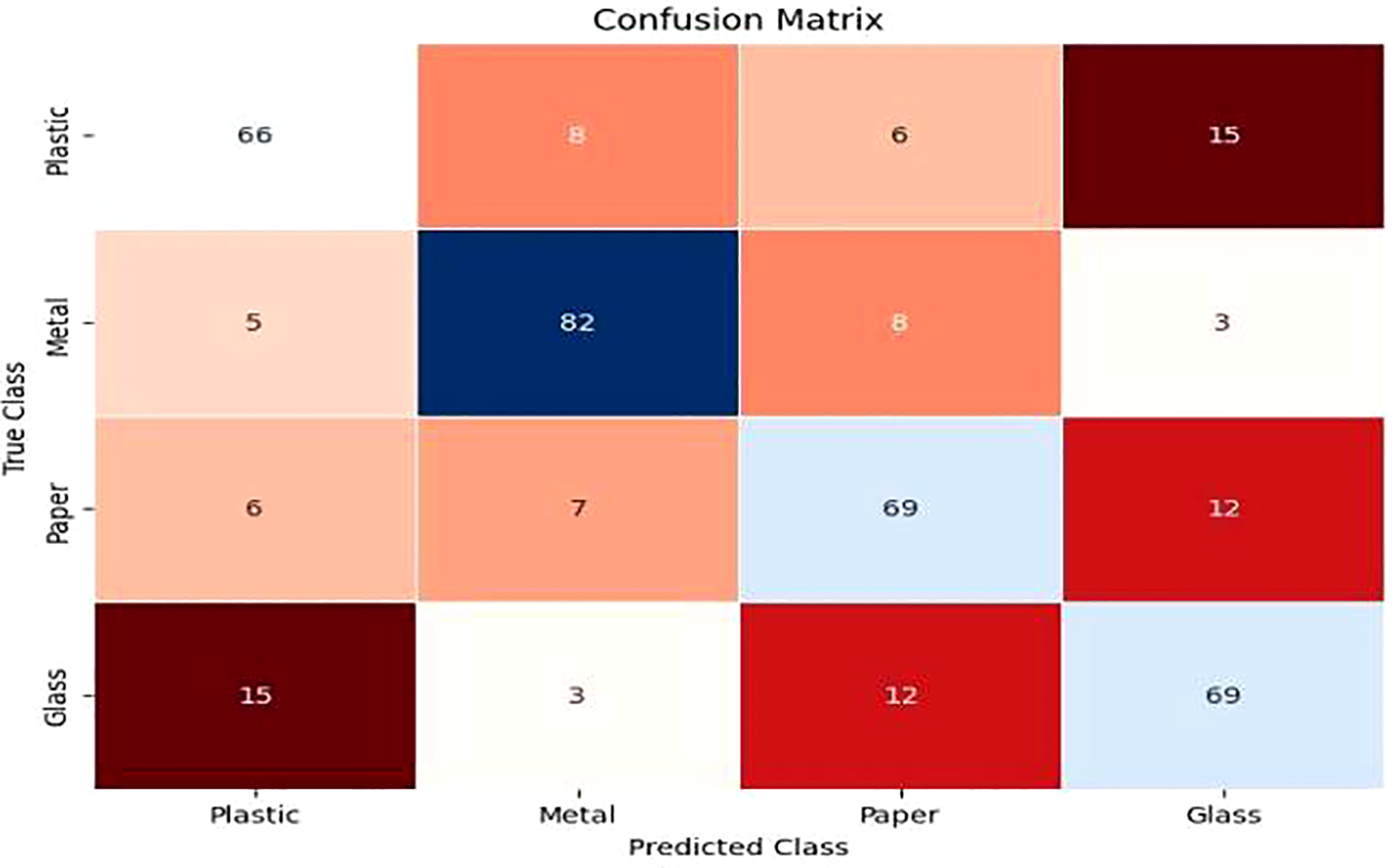

Confusion Matrix, which is presented in Figure 7, is an essential instrument for assessing the work of the classification model. Every cell denotes the number of occurrences where the predicted and actual classes are similar or different. The correct prediction is indicated by diagonal cells, and the error is indicated by off-diagonal cells. The matrix can be analysed to give information about the model accuracy, precision, recall and F1 score.

Figure 7

Confusion matrix.

Table 1 makes a comparison of the existing model AquaVision and the proposed model in identification of various classes of materials (Glass, Metal, Paper, Plastic) according to the average score of precision.

Table 1

| Methods | Class | Average precision |

|---|---|---|

| AquaVision (Panwar et al., 2020) | Glass | 0.7353 |

| Metal | 0.8427 | |

| Paper | 0.8589 | |

| Plastic | 0.8223 | |

| mAP (mean of Average Precision) | 0.8148 | |

| Proposed | Glass | 0.9866 |

| Metal | 0.8427 | |

| Paper | 0.8723 | |

| Plastic | 0.8690 | |

| mAP (mean of Average Precision) | 0.8926 |

Existing vs proposed model.

AquaVision can reach a mean average precision (mAP) of 0.8148 with the precisions of classes varying between 0.7353 (Glass) and 0.8589 (Paper). Contrastingly, the proposed model has a great enhancement, especially in the Glass class (0.9866), and has an overall higher mAP of 0.8926. The proposed model has the same performance as Metal but a little better with Paper and Plastic, which proves that it is more effective in material detection tasks.

4.3 Advantages over existing methods

The biggest advantage of the Vision Transformer is that the model possesses a self-attention system, which it employs to extract world contextual data in an image. This makes it different to the traditional CNNs, which only isolate localised characteristics. The outputs in a better understanding of marine waste, that is, in the complex oceanic environments, where littered products can overlap, be of different forms or carry negligible differences with the environment. Panoptic segmentation also extends the segmentation to include the labelling of each pixel with both semantic category and instance ID so that all litter and background objects are correctly defined. The proposed method has a higher mean average precision (mAP) with respect to the existing ones, like AquaVision, especially in the glass class, as shown in Table 1. This indicates the strength of this model to identify materials that have low inter-class variation, which is a major weakness in earlier studies. The findings of the suggested project demonstrate that the combination of instance and semantic segmentation can help identify litter and locate debris in various marine environments more accurately. Its performance can be seen in the scalability with different datasets and types of debris.

4.4 Potential limitations

Although the method has its strengths, it has a number of challenges. The training of Vision Transformers needs a lot of computational resources and may be delayed in real-time applications on field devices with limited resources, like drones or underwater robots. The quality and diversity of the input data are attributes that determine the effectiveness of the approach. In cases where there could be a low image resolution or classes that are too unbalanced, it to impact detection accuracy. Also, marine litter could be manually annotated to develop training data, which is labour-intensive and can be subjective, which can create noise during model evaluation.

4.5 Implications for future work

To overcome current constraints, future research could explore:

-

Optimisation of models to minimise the amount of computations and allow onboard real-time detection.

-

Automated or semi-supervised annotation procedures that will facilitate the creation of the dataset and enhance the generalizability.

-

Growth of methodology to identify micro-level pollution or modification to widen survey range by satellite-based remote sensing.

-

Using autonomous environmental monitoring systems to enable end-to-end detection, reporting, and mitigation of actions.

On the whole, this work preconditions more precise, trustworthy and scalable marine litter mapping, both in scientific studies and application in ocean conservation, through the power of advanced segmentation and Vision Transformer.

5 Conclusion

In this paper, the new approach to the overall marine litter classification was introduced and utilised panoptic segmentation. The combined instance and semantic segmentation enabled determining marine litter objects and background elements simultaneously through panoptic segmentation. The preprocessing methods gave the optimum input to the analytical process by enhancing the quality of images and removing noise. Through a combined panoptic segmentation strategy, the marine litter image was segmented into logical semantic segments, which facilitated the litter and found in the image. The efficiency of the offered methodology was confirmed with the help of qualitative analysis and quantitative indicators, and the assessment performed with the help of numerous datasets demonstrated a promising outcome. The technique gave skilled judgement on pollution control and preservation through providing insightful data on the distribution and composition of marine debris. The concept of panoptic segmentation was found to be a possible method of future investigation and implementation in the field of marine litter control and monitoring, since it is scalable and flexible.

Statements

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author contributions

KP: Methodology, Writing – original draft, Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Writing – review & editing, Validation, Data curation. PS: Supervision, Formal analysis, Investigation, Conceptualization, Methodology, Validation, Project administration, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declared that financial support was not received for this work and/or its publication.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fmars.2025.1726472/full#supplementary-material

References

1

Armitage S. Awty-Carroll K. Clewley D. Martinez-Vicente V. (2022). Detection and classification of floating plastic litter using a vessel-mounted video camera and deep learning. Remote Sens.14, 3425. doi: 10.3390/rs14143425

2

Balsi M. Moroni M. Chiarabini V. Tanda G. (2021). High-resolution aerial detection of marine plastic litter by hyperspectral sensing. Remote Sens.13, 1557. doi: 10.3390/rs13081557

3

Cocozza P. Scarrica V. M. Rizzo A. Serranti S. Staiano A. Bonifazi G. et al . (2025). Microplastic pollution from pellet spillage: Analysis of the Toconao ship accident along the Spanish and Portuguese coasts. Mar. pollut. Bull.211, 117430. doi: 10.1016/j.marpolbul.2024.117430

4

Corrigan B. C. Tay Z. Y. Konovessis D. (2023). Real-time instance segmentation for detection of underwater litter as a plastic source. J. Mar. Sci. Eng.11, 1532. doi: 10.3390/jmse11081532

5

Dataset collected from: https://github.com/Harsh9524/AquaTrash/tree/master/ . Available online at: https://github.com/Harsh9524/AquaTrash/tree/master/ (Accessed January 5, 2024).

6

Deng H. Ergu D. Liu F. Ma B. Cai Y. (2021). An embeddable algorithm for automatic garbage detection based on complex marine environment. Sensors21, 6391. doi: 10.3390/s21196391

7

Escobar-Sánchez G. Markfort G. Berghald M. Ritzenhofen L. Schernewski G. (2022). Aerial and underwater drones for marine litter monitoring in shallow coastal waters: factors influencing item detection and cost-efficiency. Environ. Monit. Assess.194, 863. doi: 10.1007/s10661-022-10519-5

8

Farré M. (2020). Remote and in situ devices for the assessment of marine contaminants of emerging concern and plastic debris detection. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sci. Health18, 79–94. doi: 10.1016/j.coesh.2020.10.002

9

Freitas S. Silva H. Silva E. (2021). Remote hyperspectral imaging acquisition and characterization for marine litter detection. Remote Sens.13, 2536. doi: 10.3390/rs13132536

10

Freitas S. Silva H. Silva E. (2022). Hyperspectral imaging zero-shot learning for remote marine litter detection and classification. Remote Sens.14, 5516. doi: 10.3390/rs14215516

11

Garcia-Garin O. Monleón-Getino T. López-Brosa P. Borrell A. Aguilar A. Borja-Robalino R. et al . (2021). Automatic detection and quantification of floating marine macro-litter in aerial images: Introducing a novel deep learning approach connected to a web application in R. Environ. pollut.273, 116490. doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2021.116490

12

Gonçalves G. Andriolo U. Pinto L. Bessa F. (2020). Mapping marine litter using UAS on a beach-dune system: a multidisciplinary approach. Sci. total Environ.706, 135742. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2019.135742

13

Hidaka M. Matsuoka D. Sugiyama D. Murakami K. Kako S. I. (2022). Pixel-level image classification for detecting beach litter using a deep learning approach. Mar. pollut. Bull.175, 113371. doi: 10.1016/j.marpolbul.2022.113371

14

Huang B. Chen G. Zhang H. Hou G. Radenkovic M. (2023). Instant deep sea debris detection for maneuverable underwater machines to build sustainable ocean using deep neural network. Sci. Total Environ.878, 162826. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2023.162826

15

Kremezi M. Kristollari V. Karathanassi V. Topouzelis K. Kolokoussis P. Taggio N. et al . (2021). Pansharpening PRISMA data for marine plastic litter detection using plastic indexes. IEEE Access.9, 61955–61971. doi: 10.1109/ACCESS.2021.3073903

16

Kremezi M. Kristollari V. Karathanassi V. Topouzelis K. Kolokoussis P. Taggio N. et al . (2022). Increasing the Sentinel-2 potential for marine plastic litter monitoring through image fusion techniques. Mar. pollut. Bull.182, 113974. doi: 10.1016/j.marpolbul.2022.113974

17

Kylili K. Artusi A. Hadjistassou C. (2021). A new paradigm for estimating the prevalence of plastic litter in the marine environment. Mar. pollut. Bull.173, 113127. doi: 10.1016/j.marpolbul.2021.113127

18

Ma D. Wei J. Li Y. Zhao F. Chen X. Hu Y. et al . (2023). MLDet: Towards efficient and accurate deep learning method for Marine Litter Detection. Ocean Coast. Manage.243, 106765. doi: 10.1016/j.ocecoaman.2023.106765

19

Merlino S. Paterni M. Locritani M. Andriolo U. Gonçalves G. Massetti L. (2021). Citizen science for marine litter detection and classification on unmanned aerial vehicle images. Water13, 3349. doi: 10.3390/w13233349

20

Nagy M. Istrate L. Simtinică M. Travadel S. Blanc P. (2022). Automatic detection of marine litter: a general framework to leverage synthetic data. Remote Sens.14, 6102. doi: 10.3390/rs14236102

21

Panwar H. Gupta P. K. Siddiqui M. K. Morales-Menendez R. Bhardwaj P. Sharma S. et al . (2020). AquaVision: Automating the detection of waste in water bodies using deep transfer learning. Case Stud. Chem. Environ. Eng.2, 100026. doi: 10.1016/j.cscee.2020.100026

22

Pinto L. Andriolo U. Gonçalves G. (2021). Detecting stranded macro-litter categories on drone orthophoto by a multi-class Neural Network. Mar. pollut. Bull.169, 112594. doi: 10.1016/j.marpolbul.2021.112594

23

Politikos D. V. Fakiris E. Davvetas A. Klampanos I. A. Papatheodorou G. (2021). Automatic detection of seafloor marine litter using towed camera images and deep learning. Mar. pollut. Bull.164, 111974. doi: 10.1016/j.marpolbul.2021.111974

24

Ren C. Jung H. Lee S. Jeong D. (2021). Coastal waste detection based on deep convolutional neural networks. Sensors21, 7269. doi: 10.3390/s21217269

25

Sozio A. Rizzo A. Mariano Scarrica V. Patrizio Ciro Aucelli P. Anfuso G. Barracane G. et al . (2024a). “ An innovative SAM-ViT based tool for the automatic detection of litter items on sandy beaches,” in EGU General Assembly Conference Abstracts. 8657.

26

Sozio A. Scarrica V. M. Rizzo A. Aucelli P. P. C. Barracane G. Dimuccio L. A. et al . (2024b). An innovative SAM-ViT based tool for the automatic detection of litter items on sandy beaches. EGU General Assembly 2024, EGU24-8657, Vienna, Austria.

27

Taggio N. Aiello A. Ceriola G. Kremezi M. Kristollari V. Kolokoussis P. et al . (2022). A Combination of machine learning algorithms for marine plastic litter detection exploiting hyperspectral PRISMA data. Remote Sens.14, 3606. doi: 10.3390/rs14153606

28

Themistocleous K. Papoutsa C. Michaelides S. Hadjimitsis D. (2020). Investigating detection of floating plastic litter from space using sentinel-2 imagery. Remote Sens.12, 2648. doi: 10.3390/rs12162648

29

Woods J. S. Verones F. Jolliet O. Vázquez-Rowe I. Boulay A. M. (2021). A framework for the assessment of marine litter impacts in life cycle impact assessment. Ecol. Indic.129, 107918. doi: 10.1016/j.ecolind.2021.107918

Summary

Keywords

marine litter, panoptic segmentation, mapping, debris, vision transformer

Citation

Pushkala KP and Subbulakshmi P (2025) Synergistic integration of vision transformers and advanced segmentation algorithms for panoptic mapping of marine litter. Front. Mar. Sci. 12:1726472. doi: 10.3389/fmars.2025.1726472

Received

21 October 2025

Revised

20 November 2025

Accepted

20 November 2025

Published

11 December 2025

Volume

12 - 2025

Edited by

Matteo Baini, University of Siena, Italy

Reviewed by

Carola Murano, Anton Dohrn Zoological Station Naples, Italy

Vincenzo Mariano Scarrica, University of Naples Parthenope, Italy

Updates

Copyright

© 2025 Pushkala and Subbulakshmi.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: P Subbulakshmi, subbulakshmi.p@vit.ac.in

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.