- 1Department of Internal Medicine, Laboratory of Vascular Medicine, Erasmus University Medical Center, Rotterdam, Netherlands

- 2Key Laboratory of Marine Drugs, Ministry of Education, School of Medicine and Pharmacy, Ocean University of China, Qingdao, China

- 3State Key Laboratory of Respiratory Disease, Department of Physiology, School of Basic Medical Sciences, Guangzhou Medical University, Guangzhou, China

- 4Institute of Clinical Chemistry and Clinical Pharmacology, University Hospital Bonn, Bonn, Germany

- 5Department of Neuroscience, Biomedical Research Institute, Hasselt University, Hasselt, Belgium

- 6Department of Immunology, Erasmus University Medical Center, Rotterdam, Netherlands

- 7Department of Ophthalmology, Erasmus University Medical Center, Rotterdam, Netherlands

- 8Department of Microbiology and Systems Biology, The Netherlands Organization for Applied Scientific Research (TNO), Leiden, Netherlands

- 9Mental Health and Neuroscience Research Institute, Maastricht University, Maastricht, Netherlands

- 10Department of Pediatrics, University of Groningen, University Medical Center Groningen, Groningen, Netherlands

- 11European Research Institute for the Biology of Ageing (ERIBA), University of Groningen, University Medical Center Groningen, Groningen, Netherlands

- 12Department of Food and Drug, University of Parma, Parma, Italy

- 13Department of Medicine and Surgery, University of Parma, Parma, Italy

Marine sterols from brown seaweeds, particularly fucosterol and its oxidized derivative saringosterol, have shown therapeutic potential for Alzheimer’s disease (AD) and cardiovascular diseases. Here, we aimed to elucidate the cellular and in vivo mechanisms underlying their beneficial effects. In human HepG2 hepatocytes and CCF-STTG1 astrocytoma cells, we assessed liver x receptor (LXRα /LXRβ) activation, sterol uptake, and effects on cholesterol metabolism using luciferase reporter assays, GC–MS sterol profiling, and 13C-acetate incorporation. In THP-1–derived macrophages, we evaluated sterol-induced cholesterol efflux using radiolabeled [3H]-cholesterol assays and characterized anti-inflammatory responses by quantifying lipopolysaccharide (LPS) -induced cytokine production. Wild-type C57BL/6J mice were fed diets enriched with either fucosterol (0.2% w/w) or saringosterol (0.02% w/w) for 7 days, after which sterol profiles in serum, liver, and brain were quantified by GC–MS. Hippocampal transcriptional responses were assessed by RNA sequencing. Both fucosterol and saringosterol were internalized by HepG2 and CCF-STTG1 cells and activated LXRα/β, but elicited distinct metabolic effects: fucosterol increased cholesterol synthesis and intracellular desmosterol, whereas saringosterol reduced both; only saringosterol suppressed LPS-induced interleukin (IL)-6 and tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α production in macrophages, while both enhanced cholesterol efflux. In vivo, fucosterol somewhat elevated hepatic desmosterol and decreased 5α-cholestanol and circulating oxysterols, whereas saringosterol also increased hepatic desmosterol and elevated 7α-hydroxycholesterol in liver and brain as well as serum 27-hydroxycholesterol. Transcriptome analysis revealed that fucosterol primarily modulated synaptic signaling and hormonal pathways linked to neuronal plasticity, while saringosterol affected protein quality control and neurodegenerative pathways. These data are the first on the direct comparison of the cellular and in vivo effects of fucosterol and saringosterol, revealing shared LXR activation but divergent impacts on hepatic, brain and systemic cholesterol metabolism and expression of genes involved in neural pathways, indicating complementary neuroprotective effects with therapeutic potential for AD and related disorders.

1 Introduction

The oxysterol-activated nuclear receptors, liver X receptor α (LXRα/NR1H3) and liver X receptor β (LXRβ/NR1H2), are key transcriptional regulators of cholesterol metabolism, lipogenesis, and inflammatory processes (Im and Osborne, 2011; Bilotta et al., 2020). LXRs form heterodimers with the retinoid X receptor-α (RXRα) and bind to LXR response elements (LXREs) in the regulatory regions of their target genes. Although synthetic LXR agonists have shown promise for treating cardiovascular and neurodegenerative diseases such as Alzheimer’s disease(AD) (Vanmierlo et al., 2011; Hong and Tontonoz, 2014; Moutinho and Landreth, 2017; Fitz et al., 2019), their clinical application has been hampered by serious adverse effects such as hepatic steatosis and hypertriglyceridemia (Bogie et al., 2019; Martens et al., 2021; Martens et al., 2024). Natural (oxy)phytosterols, such as saringosterol—a mixture of its 24(S)- and 24(R)-epimers—that activate LXRs without inducing the adverse effects have recently emerged as promising therapeutic candidates (Martens et al., 2021).

We previously reported that diet supplementation with lipid extracts of the brown seaweeds Sargassum fusiforme (S. fusiforme) and Himanthalia elongata (H. elongata) – which are rich in (oxy)phytosterols fucosterol and its oxidation product saringosterol – prevented deterioration of hippocampus-dependent spatial memory and reduced markers of neuroinflammation in AD mice (Bogie et al., 2019; Martens et al., 2024). Notably, saringosterol has been found to prevent cognitive decline and inflammation-related neuropathology in AD mice (Martens et al., 2021), as well as to alleviate atherosclerosis development in ApoE-deficient mice (Yan et al., 2021). Importantly, neither saringosterol nor the seaweed extracts induced adverse effects (Bogie et al., 2019; Martens et al., 2021; Martens et al., 2024). Administration of pure fucosterol – the predominant sterol in brown seaweeds – has also been found to exert neuroprotective effects by attenuating cognitive impairment and Aβ-induced neuronal death in aging rats (Oh et al., 2018). However, the underlying mechanisms by which fucosterol and saringosterol exert their neuroprotective effects are not fully clear.

In this study, we sought to delineate mechanisms by which fucosterol and saringosterol modulate cholesterol metabolism, inflammatory signaling and neural function. Through a combination of in vitro assays applying different cell types to assess LXR activation, cholesterol biosynthesis and efflux, and inflammatory cytokine expression, coupled with in vivo lipid analysis and hippocampal transcriptome profiling, we provide a comprehensive analysis of their biological actions. Complementary target prediction and pathway enrichment analyses were applied to further substantiate their systemic effects. Our findings offer novel insights into the potential regulatory roles of these seaweed-derived sterols in the control of cellular cholesterol metabolism and the modulation of inflammatory pathways, highlighting their therapeutic potential in neurodegenerative and cardiovascular diseases.

2 Material and methods

2.1 Cell culture

HepG2 (human hepatocellular carcinoma) and CCF-STTG1 (human astrocytoma) cells (ECACC, UK) were cultured in DMEM/F-12 with GlutaMAX™ supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) and 1% penicillin/streptomycin (P/S) (all from Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) at 37 °C in a humidified 5% CO2 incubator.

Primary human astrocytes (#1800, ScienCell, Carlsbad, CA, USA), kindly provided by Prof. B. Broux (Hasselt University, Belgium), were cultured in astrocyte medium (#1801, ScienCell) supplemented with 2% FBS, 1% astrocyte growth supplement, and 1% P/S in PLL-coated flasks, following the manufacturer’s protocol. Cells were seeded at 3.75 × 106 cells per T-75 flask and cultured until 90% confluence.

THP-1 cells (human monocytic cell line; kindly provided by C. van Holten-Leelen, Erasmus MC, Rotterdam, The Netherlands) were cultured in RPMI 1640 with GlutaMAX™ and 25 mM HEPES, supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated FBS, 1% P/S, 1 mM sodium pyruvate, 0.05 mM 2-mercaptoethanol, and 11 mM glucose. For cytokine assays, cells were seeded in 24-well plates at 0.5 × 106 cells/well and differentiated with 100 ng/mL phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate (PMA, Merck) for 72 h, followed by 24 h in medium with 50 ng/mL PMA. For cholesterol efflux experiments, THP-1 cells (ECACC; Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) were cultured in RPMI 1640 medium (Euroclone, Milan, Italy) supplemented with 25 mM HEPES, 0.05 mM 2-mercaptoethanol, 0.5% v/v gentamicin, 11 mM glucose, 1 mM sodium pyruvate, and 10% FBS. Cells were seeded in 24-well plates at 0.5 × 106 cells/well and differentiated with 100 ng/mL PMA for 72 h. Because these experiments were conducted at the Erasmus MC and at the University of Parma respectively, THP-1 cells were obtained from the locally available sources. Both cell lines were authenticated and maintained under comparable culture conditions to ensure experimental consistency.

2.2 Reporter assays

HepG2 or CCF-STTG1 cells (0.55 × 106) were plated in 4 mL DMEM/F-12 on T-25 dishes 24 h prior to transfection. Cells were transfected with pcDNA3.1/V5H6 vectors encoding LXRα or LXRβ, RXRα, LXRE-firefly luciferase, and renilla luciferase using FuGENE® 6 (E2692, Promega, USA) (Zhan et al., 2023). After overnight incubation at 37°C/5% CO2, cells were trypsinized, seeded in 96-well plates, and cultured in DMEM/F-12 with 10% FBS and 1% P/S. Cells were then incubated for 24 h with 2.5 μM 24(S/R)-saringosterol or fucosterol (isolated from Sargassum fusiforme, Prof. Liu, Ocean University of China) in phenol red-free medium containing 10% heat-inactivated FBS. Compounds were dissolved in ethanol, and vehicle controls containing the same final ethanol concentration (≤ 0.1% v/v) were included in all experiments to account for potential solvent effects. To confirm that ethanol at the applied concentrations does not affect cell viability, MTT assays were performed using 0.1%, 0.2%, and 0.3% ethanol; no significant effect on cell metabolism or viability was observed. Firefly and renilla luciferase activities were measured using the Dual-Luciferase® Reporter (DLR™) Assay System (E1980, Promega, USA) on a Perkin Elmer Victor X4 luminometer.

2.3 In vitro effect of fucosterol and saringosterol on cholesterol metabolism

HepG2 and CCF-STTG1 cells plated in 12-well plates were incubated with 24(S)-saringosterol, 24(R)-saringosterol, fucosterol (isolated from Sargassum fusiforme, provided by Prof. Liu, Ocean University of China), or SH42 (Item No. 34677, Cayman, USA), a selective DHCR24 inhibitor, in standard DMEM/F-12 culture medium for 24 h. Then, the extracellular medium was collected. The cells were washed with non-supplemented DMEM/F-12 (4 °C), trypsinized, and collected by centrifugation (4 °C, 1500 rpm, 5 min). Medium and cell samples were stored at -80 °C for subsequent analysis.

2.4 Cholesterol synthesis from 13C-acetate

HepG2 cells were seeded at 1 × 106 cells/well in 12-well plates and cultured for 24 h in DMEM/F-12 with 10% FBS and 1% P/S. Medium was replaced with DMEM/F-12 containing 10 mM 1-¹³C-acetate and 2.5 µM of 24(S)-saringosterol, 24(R)-saringosterol, or fucosterol. Cells were incubated for 48 or 72 h, with medium refreshed every 24 h. After incubation, cells were washed, trypsinized, centrifuged (4 °C, 1500 rpm, 5 min), dried, and weighed. Cells and media were analyzed for sterol content by GC-MS. Incorporation of 13C-acetate into cholesterol was quantified by analyzing m/z 372–379 and 462–469, correcting for natural 13C abundance (1.1%), and compared with unlabeled controls (Ahmed et al., 2014; Gkiouli et al., 2019).

2.5 Cholesterol efflux

THP-1-derived macrophages were labeled for 24 h with [1,2-3H]-cholesterol (2 μCi/mL, #NET13900, PerkinElmer, MA, USA) in RPMI with 1% FBS and 2 μg/mL ACAT inhibitor (#S9318, Sandoz 58-035, Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA), according to a standardized radioisotopic technique (Turri et al., 2023). Cells were equilibrated for 20 h in 0.2% BSA medium (#A8806, Sigma-Aldrich) supplemented with 22-hydroxycholesterol (22-OHC, 12.4 µM, #H9384) and 9-cis-retinoic acid (9cRA, 10 µM, #R4643, Sigma-Aldrich) and treated with saringosterol, fucosterol, and desmosterol (1.25, 2.5, 5 µM) or vehicle (ethanol). Cholesterol efflux was induced for 6 h using 2% pooled human serum, 10 µg/mL ApoA-I, or 12.5 µg/mL HDL (#A0722 and #LP3 all from Sigma-Aldrich). Cholesterol efflux capacity (CEC) was calculated as the percentage of radiolabeled cholesterol released in culture medium relative to total cellular radioactivity and normalized to ethanol-treated controls. Intra-assay coefficient of variation for ApoA-I- and HDL-mediated CEC was <10%.

2.6 Cytokine production

THP-1-derived macrophages were stimulated with 10 ng/mL LPS (Merck, St. Louis, MO, USA) and incubated with saringosterol, fucosterol, or desmosterol at 5 or 10 µM for 24 h at 37 °C and 5% CO2. Culture media were collected and stored at −80 °C. Pro- and anti-inflammatory cytokines (IL-1β, IL-8, TNF-α, IL-6, IL-10) were quantified using a Human Magnetic Luminex Discovery Assay Kit (Kit Lot: L140180, Cat #: LXSAHM, R&D Systems, Abdingdon, UK) with data acquisition on BioPlex MAGPIX™ and analysis in Bio-Plex Manager MP software (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA).

2.7 Animals and diets

Wild-type male C57BL6/J mice (8–10 weeks old) were obtained through in-house breeding (fucosterol trial: breeding protocol ID202132B, Hasselt University, saringosterol trial: breeding protocol 1005EM, University of Groningen). The mice were housed in a conventional animal facility, with ad libitum access to food and water, and maintained on an inversed 12 h light/dark cycle. The animal procedures were approved by the ethical committees for animal experiments of Hasselt University (fucosterol trial: protocol ID202249) or the University of Groningen (saringosterol trial: protocol ID AVD10500202115290) in accordance with institutional guidelines. Mice received either non-supplemented standard chow (vehicle, n = 5) or fucosterol (Lemeitian Medicine, Chengdu, China)-supplemented chow (0.2% w/w, n = 5) or saringosterol (COMFiON BV, Leimuiden, The Netherlands)-supplemented chow (0.02% w/w, n = 5) for 7 consecutive days. The fucosterol and saringosterol dosages were based on their average concentrations in seaweed extracts used in previous experiments (Bogie et al., 2019; Martens et al., 2024).

2.8 Tissue preparation

Mice were euthanized via intraperitoneal injection of Dolethal (200 mg/kg, Vetoquinol, Aartselaar, Belgium), followed by cardiac puncture and transcardiac perfusion with heparin-PBS. Blood was centrifuged at 4000 x g for 5 minutes to obtain serum, which was stored at -80°C. Brains were hemisected; the right cerebellum and hippocampus were snap-frozen for sterol analyses, and the left hippocampus for RNA sequencing. Livers were removed, snap-frozen, and stored at -80°C for sterol and triglyceride measurements.

2.9 Quantification of (oxy)sterols and stanols

Cells or tissue samples were spun in a speed vacuum dryer (Thermo Fisher Scientific) and weighed to determine the dry weight. (Oxy)sterols and stanols were quantified as previously described (Lütjohann et al., 2002; Mackay et al., 2014; Vanbrabant et al., 2021), using 50 µg 5α-cholestane (1 mg/mL, Serva, Heidelberg, Germany) and 1 µg epicoprostanol (100 µg/mL, Sigma, Deisenhofen, Germany) as internal standards. Steroids were extracted with cyclohexane after saponification and neutralization, evaporated, and derivatized to (di-)trimethylsilyl (TMSi)-ethers by adding 300 µL TMSi-reagent (pyridine-hexamethyldisilazane-chlorotrimethylsilane, 9:3:1, v/v/v; Merck, Darmstadt, Germany) and incubating for 2 h at 90°C. Derivatized samples were evaporated under nitrogen at 65°C, dissolved in 80 µL n-decane, and analyzed by GC-MS-SIM. Concentrations of sterols and stanols, including 24(S)- and 24(R)-saringosterol, fucosterol, cholesterol precursors, oxycholesterols, and plant sterols/stanols, were calculated from standard curves using epicoprostanol, while cholesterol concentrations were determined by one-point calibration with 5α-cholestane using GC-FID (Šošić-Jurjević et al., 2019).

2.10 Triglyceride measurements

Liver samples were homogenized using the BioSpec Mini-Beadbeater (Biospec Products, Bartlesville, OK, USA). Lipid extraction was performed as described by Bligh and Dyer (1959). Serum samples were collected as described in the tissue preparation section. Triglyceride concentrations in hepatic lipid extracts and serum were determined using a colorimetric enzymatic assay (DiaSys Diagnostic Systems, Holzheim, Germany) based on glycerol measurement. In brief, triglycerides were enzymatically hydrolyzed by lipoprotein lipase (LPL) to release glycerol and free fatty acids. The released glycerol was phosphorylated by glycerol kinase (GK) to glycerol-3-phosphate, which was then oxidized by glycerol-3-phosphate oxidase (GPO) to produce hydrogen peroxide. Hydrogen peroxide reacted with 4-aminoantipyrine and 4-chlorophenol in the presence of peroxidase (POD) to form quinoneimine, a chromophore detected colorimetrically. Baseline free glycerol in samples was corrected according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

2.11 RNA sequencing

Hippocampus samples of wild-type mice were homogenized (BioSpec Mini-Beadbeater, Biospec Products, Bartlesville, OK, USA), and total RNA was isolated as described above. RNA integrity was assessed using the RNA 6000 Nano Lab-on-a-Chip kit and a Bioanalyzer 2100 (Agilent Technologies, Amstelveen, The Netherlands). Libraries were prepared using the NEBNext Ultra II Directional RNA Library Prep Kit (NEB #E7760S/L, New England Biolabs, Ipswich, MA, USA), including mRNA isolation, fragmentation, cDNA synthesis, adapter ligation, and PCR amplification. Library quality and size distribution (300–500 bp) were confirmed with a Fragment Analyzer (Agilent Technologies). Sequencing was performed on an Illumina NovaSeq6000 (GenomeScan B.V., Leiden, the Netherlands) at 1.1 nM library concentration, yielding ≥15 million 150 nt paired-end reads per sample. Reads were aligned to Mus musculus GRCm38.gencode.vM19 using STAR 2.5, counted with HTSeq-count v0.6.1p1, and differential expression was analyzed using DESeq2. Functional enrichment of genes with p < 0.01 was performed using Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) and Gene Ontology (GO) pathways in R (version 4.4.1) using the clusterProfiler and enrichplot packages. Pathways with adjusted p < 0.01 were considered significantly enriched.

2.12 Target prediction for saringosterol, fucosterol, and desmosterol

The chemical structures of saringosterol, fucosterol, and desmosterol were uploaded to the PubChem compound website (https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/) and exported as an SDF file. Next, the SDF file was uploaded to the PharmMapper database for target prediction. Targets were identified with the fit score threshold set at 3.5 and the Z-score set at 1 (Wang et al., 2016; Wang et al., 2017). The human target proteins (25 predicted targets of saringosterol, 29 predicted targets of fucosterol, and 30 predicted targets of desmosterol) were imported into and analyzed by String (https://string-db.org/). KEGG pathways and Reactome pathways were analyzed to explore the effects of saringosterol, fucosterol, and desmosterol on metabolic pathways. The Venn diagram was drawn through venny 2.1.0 (https://bioinfogp.cnb.csic.es/tools/venny/).

2.13 Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism 9.5. Data are presented as mean ± SD. Differences between two groups were analyzed using the Mann–Whitney U test, and multiple-group comparisons were performed using the Kruskal–Wallis test followed by Dunn’s post hoc test. When comparing a single experimental group against a reference value of 1, a one-sample Wilcoxon signed-rank test was used. RNA sequencing data were analyzed using the Differential Gene Expression–Gene Set Analysis (DGE–GSA) algorithm, with statistical significance defined as p < 0.05.

3 Results

3.1 LXR activation by seaweed-derived fucosterol and saringosterol

Both fucosterol and saringosterol activated LXRα and LXRβ in HepG2 and in CCF-STTG1 cells (Figure 1). However, the activation potency of fucosterol was consistently lower than that of saringosterol. At the two tested concentrations (2.5 and 5.0 µM), both saringosterol epimers [24(S) and 24(R)] and fucosterol were internalized dose-dependently, with a similar fraction of sterols internalized (Figures 2A, B). Time-course experiments revealed comparable uptake kinetics across all sterols, but the intracellular levels of fucosterol reached only 40–60% of those of either saringosterol epimer within 24 h (Figure 2C). Despite increased cellular content over time, the apparent equilibration rate declined within 24 h for all sterols, with fucosterol exhibiting approximately half the rate observed for both saringosterol epimers (Figure 2D). All sterols underwent substantial re-release into the culture medium, indicating rapid equilibration with the extracellular environment. Notably, fucosterol was re-released to a higher extend than both saringosterol epimers, resulting in lower net cellular accumulation (Figures 2E, F). The weaker LXR activation observed for fucosterol may correlate with its reduced cellular retention, which results from both slower uptake and enhanced re-release.

Figure 1. Fucosterol and saringosterol activated LXRα and LXRβ. (A) Schematic overview of the luciferase reporter assay used to evaluate LXRα/β activation. (B, C) LXRα/β activation measured in HepG2 (B) and CCF-STTG1 (C) cells. Cells were treated with saringosterol (Saringo, 2.5 µM), fucosterol (Fuco, 2.5 µM), or the positive control T0901317 (1 µM). Receptor activity is expressed as fold change relative to ethanol (EtOH)-treated cells (n ≥ 9). Data represent mean ± SD from three to four independent experiments, each performed with three technical replicates. Statistical significance relative to EtOH-treated cells was determined using a Mann–Whitney U test: *p<0.05, **p<0.01, and ***p<0.001.

Figure 2. Internalization and re-release of fucosterol and saringosterol by HepG2 and CCF-STTG1 cells. (A, B) Internalization of 24(S)-saringosterol [24(S)-S], 24(R)-saringosterol [24(R)-S)], and fucosterol (Fuco) in HepG2 (A) and CCF-STTG1 (B) cells after 24 h incubation with 2.5 or 5.0 µM sterols, expressed as % of added sterol. (C) Time-dependent changes in intracellular sterol fraction in CCF-STTG1 cells. (D) Average apparent equilibration rate of sterols in CCF-STTG1 cells, expressed as % change per hour (%/h). (E, F) Re-release of fucosterol and saringosterol into the culture medium by HepG2 (E) and CCF-STTG1 (F) cells. Following 24 h of sterol loading (2.5 µM), the medium was collected (medium-first 24 h), cells were washed and cultured in sterol-free medium for another 24 h before measuring sterol concentrations in cells and media. Data represent mean ± SD from at least three independent experiments (n ≥ 9).

3.2 Fucosterol and saringosterol differentially modulate cholesterol metabolism

We investigated whether the distinct LXR activation profiles of fucosterol and saringosterol differentially affect cholesterol biosynthesis in vitro. We first measured desmosterol, the immediate precursor of cholesterol and an endogenous LXR ligand. In CCF-STTG1 cells, fucosterol caused a trend toward increased intracellular desmosterol, accompanied by a non-significant increase in extracellular desmosterol (p > 0.05; Supplementary Figure S1), comparable to the Δ24-dehydrocholesterol reductase (DHCR24) inhibitor SH42 (Müller et al., 2017). In primary human astrocytes, fucosterol and saringosterol exerted opposing trends on desmosterol (increase of 31.9 ± 48.9% vs. decrease of 46.3 ± 27.4%), though these changes did not reach statistical significance (Supplementary Figure S2).

In HepG2 cells, as illustrated in the schematic representation of the cholesterol metabolic pathway (Figure 3A), fucosterol increased intracellular desmosterol while reducing lathosterol, without significantly affecting cholesterol or lanosterol levels (Figures 3B–E). While fucosterol caused a ~2-fold increase in desmosterol, SH42 induced a ~15-fold increase (Supplementary Figure S3). In contrast, both 24(S)- and 24(R)-saringosterol dose-dependently decreased desmosterol, cholesterol, and lathosterol, while lanosterol remained unchanged. (Figures 3B–E). Downstream cholesterol metabolites were also differentially affected. At 2.5 µM, 5α-cholestanol showed a decreasing trend with all sterols. At 5.0 µM, a significant reduction was observed for both 24(S)- and 24(R)-saringosterol, whereas fucosterol did not significantly alter 5α-cholestanol levels (Figure 3F). Both saringosterol epimers, but not fucosterol, dose-dependently increased 27-hydroxycholesterol (27-OHC) up to 3–5-fold (Figure 3G).

Figure 3. Fucosterol and saringosterol affect cholesterol metabolism in HepG2 cells. Simplified schematic diagram of cholesterol Bloch and Kandutsch Russell cholesterol synthesis pathways (A). Intracellular concentrations of desmosterol (B), cholesterol (C), lanosterol (D), lathosterol (E), and 5α-cholestanol (F), and 27-hydroxycholesterol (27-OHC, fold change) (G) were measured after 24 h incubation with saringosterol or fucosterol at 2.5 or 5.0 µM. Data are mean ± SD (n = 3). Statistical significance versus the vehicle control [EtOH; 0.1% ethanol] was assessed by the Mann–Whitney U test: *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001.

3.3 Fucosterol enhances de novo cholesterol biosynthesis in HepG2 cells

To quantify the effects of fucosterol and saringosterol on cholesterol biosynthesis, we performed stable isotope tracing in HepG2 cells using [1-13C]-acetate (Figure 4A). Both 24(S)- and 24(R)-saringosterol significantly suppressed de novo cholesterol synthesis, reducing intracellular 13C-cholesterol by 35–37% at 48 h and 27–35% at 72 h (p < 0.05, Figures 4B, C). Extracellular 13C-cholesterol was also decreased across all time points (24–72 h; Figures 4B, C). Conversely, fucosterol increased both intracellular (17.38 ± 9.07%) and extracellular (15.61 ± 7.36%) 13C-cholesterol levels, but only at the 72 h (p < 0.05), with no significant effects observed at earlier time points (Figures 4C, D).

![Diagram showing the process of [1-\[1-C^{13}\]-acetate] incubation with HepG2 cells, followed by GC-MS analysis for [C^{13}]-cholesterol enrichment. Bar graphs illustrate cholesterol enrichment at 48 hours (B) and 72 hours (C) of incubation with different sterols, including fucoasterol and saringosterol, represented by varying shades for medium and wash conditions. Significant differences are indicated by asterisks. Graph (D) shows a time-course analysis of \[1-C^{13}\]-cholesterol in the medium, plotted against time in hours, for ethanol, 24(S)-S, 24(R)-S, and Fuco. Error bars indicate standard deviations.](https://www.frontiersin.org/files/Articles/1728727/fmars-12-1728727-HTML-r1/image_m/fmars-12-1728727-g004.jpg)

Figure 4. Fucosterol and Saringosterol differentially affect cholesterol synthesis in HepG2 cells. (A) Schematic diagram of sodium [1-13C]-acetate incorporation into cholesterol. (B, C) Intracellular and extracellular 13C-cholesterol levels were quantified in HepG2 cells after 48 h (B) and 72 h (C) incubation with 2.5 μM 24(S)-saringosterol (24(S)-S), 24(R)-saringosterol (24(R)-S), or fucosterol (Fuco). Culture medium was refreshed every 24 h, and all fractions (each 24 h medium, the final wash medium, and cell lysates) were collected and analyzed. (D) 13C-cholesterol release rates (%/h) were calculated from the 24, 48, and 72 h medium fractions shown in (C) Data represent mean ± SD from three independent experiments, each performed in triplicate. Statistical significance versus control (EtOH) was assessed by Mann–Whitney U test: *p < 0.05, ***p < 0.001.

3.4 Effects of fucosterol and saringosterol on the pro-inflammatory phenotype of human macrophages

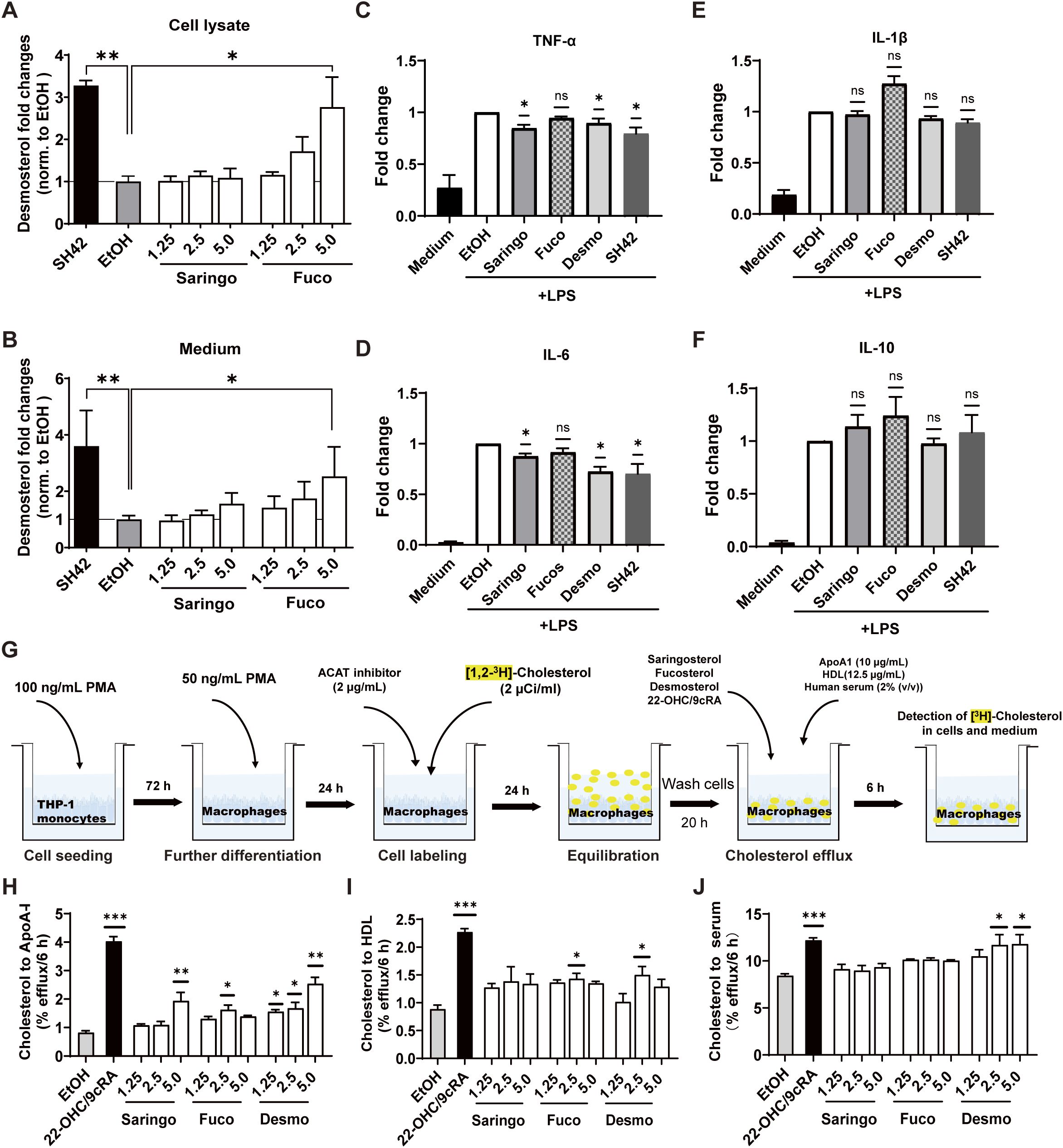

Consistent with the results obtained in CCF-STTG1 and HepG2 cells (Figures 3, S1), fucosterol, but not saringosterol, increased intracellular desmosterol concentrations in THP-1-derived macrophages at 5.0 µM, as well as in the culture medium (Figures 5A, B). An increase in desmosterol concentrations in macrophages has been shown to dampen the inflammatory response (Spann et al., 2012; Zhang et al., 2021). Following LPS stimulation, saringosterol, desmosterol, and the DHCR24 inhibitor SH42, which promotes intracellular desmosterol accumulation, all reduced the production of TNF-α and IL-6 (Figures 5C, D). The production of IL-1β and IL-10 remained unaffected across all treatments (Figures 5E, F).

Figure 5. Fucosterol and saringosterol differentially modulate desmosterol levels, cytokine production, and cholesterol efflux in THP-1-derived macrophages. Desmosterol level in THP-1-derived macrophages (A) and culture medium (B) after incubation for 24 h with saringosterol (Saringo), fucosterol (Fuco), and SH42. Data are expressed as fold changes relative to EtOH-incubated cells (n = 9). (C–F) Concentrations of pro-inflammatory cytokines TNF-α (C), IL-6 (D), and IL-1β (E), as well as anti-inflammatory cytokine IL-10 (F) in the culture medium of LPS-activated THP-1-derived macrophages. Cells were treated for 24 h with 5.0 μM saringosterol, fucosterol, desmosterol, or SH42 (n = 3). Data are expressed as fold changes relative to LPS-stimulated cells incubated with EtOH. (G) Schematic diagram of cholesterol efflux assay. (H–J) Cholesterol efflux from cholesterol-loaded THP-1-derived macrophages to lipid-free ApoA-I (H), HDL (I), and normolipidemic serum (J) after 24 h treatment with 1.25, 2.5 or 5.0 μM saringosterol, fucosterol, desmosterol, or 22-hydroxycholesterol/9-cis-retinoic acid (22-OHC/9cRA) at 12.4 µM/10 µM) used as positive controls. Data are expressed relative to EtOH-treated cells (n = 6). Data are presented as mean ± SD from three independent experiments. Statistical analysis was performed using a one-sample Wilcoxon signed-rank test relative to 1 for panels (C–F), and a Kruskal–Wallis test followed by Dunn’s post-hoc test for panels (A, B, H–J). Significance levels: *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001.

Cholesterol accumulation in macrophages is known to promote inflammatory responses, whereas enhanced cholesterol efflux can counteract this effect (Tall and Yvan-Charvet, 2015). We assessed the ability of saringosterol, fucosterol, and desmosterol to induce cholesterol efflux from THP-1-derived macrophages (Figure 5G). Cholesterol efflux to ApoA-I was increased by saringosterol (5.0 μM) and fucosterol (2.5 µM), and by desmosterol (2.5 and 5.0 µM) (Figure 5H). Fucosterol and desmosterol at 2.5 µM also significantly increased cholesterol efflux to HDL, while saringosterol did not (Figure 5I). Cholesterol efflux to serum was significantly induced exclusively by desmosterol (2.5 and 5 µM, Figure 5J).

3.5 Tissue-selective remodeling of cholesterol metabolism by dietary fucosterol and saringosterol in wild-type mice

Wild-type mice received diet supplementation with fucosterol for one week to determine the effect on sterol metabolism and the early phase modulatory effect on the transcriptome. Fucosterol supplementation led to an accumulation of fucosterol in liver, serum, cerebellum, and hippocampus (Figures 6A–D). Desmosterol concentrations were modestly increased in the liver (p < 0.01), but not in serum, hippocampus, or cerebellum. Alongside the rise in fucosterol, concentrations of other phytosterols were significantly reduced in liver and serum (Figures 6C, D). Fucosterol supplementation also lowered hepatic 5α-cholestanol, as well as 7α-OHC, and 27-OHC in serum (Figures 6C, D).

Figure 6. Tissue-selective alterations in Steroid profiles after one week of dietary fucosterol supplementation in wild-type mice. (A–D) Concentrations of plant sterols and stanols, cholesterol, cholesterol precursors, and metabolites in the cerebellum (A), hippocampus (B), liver (C), and serum (D) of wild-type mice after one week of dietary supplementation with fucosterol. Data are presented as mean ± SD (n = 5). Abbreviations: 7α-hydroxycholesterol (7α-OHC), 24-hydroxycholesterol (24-OHC), and 27-hydroxycholesterol (27-OHC), 5α-cholestanol (cholestanol). Statistical significance was assessed using the Mann–Whitney U test: *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01.

Saringosterol supplementation for one week increased saringosterol concentrations in the liver, serum, and cerebellum (Supplementary Figure S4). It also decreased the hepatic fucosterol and campesterol concentrations, whereas other plant sterols and total plant sterols remained unaffected. Unlike the reduction in desmosterol upon saringosterol administration to HepG2 cells, diet supplementation with saringosterol to wild-type mice slightly increased hepatic desmosterol concentrations, similar to fucosterol (Supplementary Figure S4B). Saringosterol supplementation decreased the lathosterol concentration and increased the 7α-OHC concentration in cerebellum (Supplementary Figure S4A), as well as 7α-OHC in liver and 27-OHC in serum (Supplementary Figures S4B, C).

3.6 Fucosterol does not increase hepatic or circulating triglycerides in mice

To evaluate whether fucosterol affects hepatic lipogenesis, a common side effect of most synthetic LXR agonists (Cha and Repa, 2007), we assessed serum and hepatic triglyceride (TG) concentrations in mice after one week of fucosterol treatment: TG in serum and liver remained unaltered (Figure 7). Consistently, fucosterol did not affect the expression of SREBF1, the master regulator of lipogenesis, or SCD1, a key enzyme in fatty acid synthesis, in HepG2 cells (Supplementary Figure S5). These findings demonstrate that fucosterol administration does not induce lipogenesis or hypertriglyceridemia under these experimental conditions.

Figure 7. Effect of dietary fucosterol on TG levels in mice. Triglyceride (TG) concentrations in serum (A) and liver (B) of wild-type mice after one week of dietary supplementation with fucosterol. Data are presented as mean ± SD of 5 animals per group (n = 5). Statistical significance versus vehicle control (non-supplemented standard chow) was assessed by Mann–Whitney U test. No statistically significant differences were detected.

3.7 Dietary fucosterol and saringosterol differentially modulate hippocampal transcriptome in mice

Although fucosterol accumulated in the brain following oral administration, it did not significantly affect levels of desmosterol or of other sterols in cerebellum or hippocampus, suggesting that its neurological effects are unlikely to be mediated via local changes in sterol composition, particularly cholesterol intermediates such as desmosterol. To explore the potential neural impact of fucosterol beyond sterol alterations, we performed RNA-sequencing of hippocampal tissue from mice after one week of its diet supplementation (Figure 8).

Figure 8. Transcriptome profiling of the hippocampus reveals distinct gene expression patterns following fucosterol and saringosterol supplementation. RNA-sequencing was performed on hippocampal tissue from mice after one week of dietary supplementation with fucosterol or saringosterol. KEGG pathway enrichment of differentially expressed genes (DEGs) following (A) fucosterol versus control-fed mice and (B) saringosterol- versus control-fed mice. Gene Ontology (GO) enrichment analysis for significantly enriched categories (p < 0.05, padj < 0.01) is shown for (C) fucosterol-fed and (D) saringosterol-fed mice relative to controls. Direct comparison between fucosterol- and saringosterol-fed mice highlights (E) differentially enriched GO categories, and (F) KEGG pathways. These comparisons indicate both shared and distinct transcriptional responses elicited by the two sterols. Biological process (BP), cellular component (CC), and molecular function (MF).

Transcriptome profiling revealed that fucosterol primarily modulated genes involved in neuronal structure and signaling. Gene Ontology (GO) enrichment highlighted cellular components such as axons and microtubules, and molecular functions related to myosin II binding, small GTPase binding, and histone modification. Biological processes included RNA polymerase III-mediated transcription, oligodendrocyte development, dendritic spine formation, and microtubule polymerization. KEGG analysis showed enrichment in apelin signaling, cholinergic synapses and insulin signaling pathways, suggesting enhanced neuronal plasticity and intracellular signaling (Figures 8A, B).

In contrast, saringosterol enriched pathways related to proteostasis and RNA metabolism, including protein refolding, RNA splicing and RNA catabolic process. Enriched cellular components included the proteasome, nuclear pores and ER-Golgi compartments. For molecular functions, enriched terms were mainly associated with chromatin modification, RNA regulation, and ubiquitin-mediated processes, such as histone methyltransferase activity, RNA polymerase II complex binding, NF-κB binding, and ubiquitin recognition. KEGG pathways implicated in neurodegenerative diseases—such as AD, Huntington’s, prion, and Parkinson’s diseases—were also among the top 10 enriched terms (Figures 8C, D), suggesting an effect on neurodegeneration-related processes.

Direct comparison of fucosterol versus saringosterol further underscored their differential effects. Fucosterol treatment was associated with enriched GO terms in chromatin remodeling, proteasome complex, microtubule anchoring, and positive regulation of transcription by RNA polymerase III (Figure 8E). KEGG pathways significantly enriched in this comparison included multiple neurodegenerative diseases (e.g., Parkinson’s disease, Huntington’s disease, prion disease, AD) (Figure 8F). Notably, these neurodegeneration-related pathways were absent in the fucosterol versus control group but present in both the saringosterol versus control and fucosterol versus saringosterol comparisons.

Importantly, hippocampal transcriptomic analyses did not reveal strong enrichment of cholesterol metabolism pathways, suggesting that the neural effects of fucosterol and saringosterol are mediated primarily through transcriptional programs related to neuronal structure, signaling, and protein homeostasis rather than through direct modulation of sterol metabolism.

3.8 Target prediction and potential key pathways identification

To capture potential systemic mechanisms that might not be evident from brain-restricted transcriptome data, we performed in silico target prediction for fucosterol, saringosterol, and desmosterol using PharmMapper (Wang et al., 2016; Wang et al., 2017), with results for Homo sapiens summarized in Supplementary Table S1. Pathway enrichment analysis using Reactome and KEGG via STRING revealed several putative mechanisms through which these sterols may influence both brain and systemic cholesterol homeostasis and broader metabolic functions.

Shared Reactome pathways enriched by all three sterols included SUMOylation of nuclear receptors, bile acid synthesis via 27-OHC, nuclear receptor-mediated transcription, and general steroid metabolism (Figure 9A). These common pathways point to overlapping roles in lipid homeostasis and nuclear receptor signaling, consistent with hippocampal transcriptome findings implicating lipid-related signaling and cytoskeletal organization.

Fucosterol and saringosterol jointly enriched pathways related to LXR-mediated cholesterol uptake, bile acid homeostasis, lipogenesis, and PPARα-activated gene expression, further reinforcing their capacity to regulate lipid metabolism at the transcriptional level. Uniquely, fucosterol and desmosterol were associated with pathways related to retinoid metabolism, including the canonical retinoid cycle in rods, retinoid transport, and visual phototransduction, indicating a potential link between these sterols and retinoid-sensitive transcriptional networks. Fucosterol-specific targets were enriched in heme degradation and platelet sensitization by LDL.

KEGG enrichment also revealed a systemic role in detoxification and metabolic adaptation. Targets of all three sterols were significantly enriched in xenobiotic metabolism pathways, including cytochrome P450-related drug metabolism, steroid hormone biosynthesis, and insulin resistance. Additionally, desmosterol was significantly enriched in pathways such as chemical carcinogenesis, glutathione metabolism, Th17 cell differentiation, and adipocytokine signaling, suggesting a potential immunometabolic crosstalk mediated by this sterol (Figure 9B).

Figure 9. Enrichment analysis of predicted key targets of saringosterol, fucosterol, and desmosterol in PharmMapper database. Venn diagram of the predicted Reactome (RCTM) pathways affected by saringosterol, fucosterol, and desmosterol (A). KEGG pathway enrichment analysis of saringosterol, fucosterol, and desmosterol (B). False discovery rate < 0.05, strength > 1.0.

Overall, whereas hippocampal transcriptome primarily reflected neural-specific effects, these target predictions highlight broader systemic roles, particularly in cholesterol metabolism and lipid homeostasis, that are not directly apparent in the brain.

4 Discussion

LXRs have emerged as promising therapeutic targets for neurodegenerative and cardiometabolic diseases due to their central roles in lipid metabolism and inflammatory regulation. Our prior studies showed that dietary administration of 24(S)-saringosterol or seaweed lipid extracts rich in fucosterol and saringosterol attenuated cognitive decline in APPswePS1ΔE9 mice (Martens et al., 2021; Martens et al., 2024). However, the mechanisms underlying these neuroprotective effects have remained unclear. Here, we reveal that fucosterol and saringosterol both activate LXRs, albeit with distinct potencies partly related to differences in cellular uptake efficiency, leading to differential mechanisms of action in different cell types. The integrated hippocampus-specific transcriptomic profiling with systemic in silico target prediction using PharmMapper indicated complementary effects.

Saringosterol’s more potent LXR agonistic activity can be attributed to its polar 24-hydroxyl group, which enhances receptor binding, hydrophilicity, and transcriptional activation (Chen et al., 2014). By contrast, fucosterol possesses a double bond at the same position, lacking the polar group needed for optimal receptor interaction. Cellular assays demonstrated that saringosterol exhibited more efficient uptake and lower release from the cells into the culture medium, leading to greater intracellular accumulation and stronger downstream activation. Upon 24 h incubation with 5 µM sterol, HepG2 cells internalized about twice as much saringosterol as fucosterol (~76 ng/mg cells vs. ~33 ng/mg cells). The concentrations of fucosterol and saringosterol used (≤ 5 µM) are well below reported cytotoxic ranges in cultured cells (Chen et al., 2014; Choi et al., 2015; Meinita et al., 2021). This higher intracellular accumulation of saringosterol likely underlies its stronger LXR activation. Notably, despite lower cellular uptake, fucosterol raised intracellular desmosterol from 14 ng/mg in control cells to 19.8 ng/mg at 2.5 µM and 27 ng/mg at 5.0 µM, whereas both 24(S)- and 24(R)-saringosterol decreased desmosterol, suggesting fucosterol’s potential for indirect LXR activation via modulation of desmosterol (Spann et al., 2012).

These findings imply that fucosterol may modulate LXR activity primarily by interfering with cholesterol biosynthesis, likely through inhibition of DHCR24, the terminal enzyme in the Bloch pathway that converts desmosterol to cholesterol (Luu et al., 2014). This is supported by the elevated desmosterol-to-cholesterol ratio in fucosterol-treated cells and aligns with prior findings showing that phytosterols with double bonds in their side chains, such as stigmasterol, brassicasterol, and ergosterol, can inhibit DHCR24 (Fernández et al., 2002). While indirect, this mechanism fosters intracellular accumulation of desmosterol, an endogenous LXR ligand that enhances ABCA1/ABCG1-mediated cholesterol efflux (Yang et al., 2006; Muse et al., 2018), and suppresses SREBP2 cleavage via SCAP interaction, thereby downregulating cholesterol synthesis and uptake (Körner et al., 2019). However, despite these pronounced in vitro effects, fucosterol administration in vivo did not significantly affect brain desmosterol nor cholesterol levels. Here we show that one-week supplementation of wild-type mice with pure fucosterol only modestly increased hepatic desmosterol levels by approximately 40%, without affecting desmosterol concentrations in serum or brain. This modest increase in hepatic desmosterol is markedly lower than the ~750% elevation previously observed after 12-week dietary supplementation with seaweed lipid extracts (Martens et al., 2024). This difference might be explained by several factors. First, the short time frame limits tissue accumulation and CNS penetration of fucosterol, preventing strong engagement of cholesterol biosynthesis pathways. Second, the complex extracts used in long-term studies contain multiple sterols that may potentially act synergistically to inhibit DHCR24 and enhance LXR activation, unlike fucosterol alone. Third, the modulation of DHCR24 and downstream desmosterol accumulation is a relatively slow process that requires sustained exposure. Therefore, our one-week intervention primarily captures early metabolic responses and initial tissue distribution, without sufficient time for pronounced desmosterol accumulation in liver or brain. These prolonged supplementation studies are necessary to determine whether fucosterol alone can reproduce the strong CNS desmosterol elevation and neuroprotective effects observed in the previous extract studies involving long term exposure to extracts. Interestingly, in contrast to its effects in HepG2 cells, saringosterol administration to mice modestly increased hepatic desmosterol concentrations, comparable to the effect of fucosterol. However, while fucosterol supplementation reduced hepatic cholesterol and total phytosterol concentrations, these were not affected by saringosterol. This likely reflects the greater complexity of cholesterol homeostasis in peripheral tissues, which depends on a tightly regulated balance between synthesis, absorption, transport, and excretion (Vaughan and Oram, 2006), unlike the less complicated regulation observed in isolated cells.

These in vivo findings contrast with the pronounced increase in desmosterol and cholesterol observed in vitro, likely due to limited transfer across the blood-brain barrier and CNS entrance, rapid peripheral metabolism, and efficient secretion of synthesized cholesterol from the liver into the circulation, which together prevent substantial accumulation in hepatic or brain tissues. After one week of dietary supplementation, fucosterol (0.2% w/w) modestly increased cerebellar fucosterol concentrations (from 2.31 to 3.52 ng/mg), whereas saringosterol supplementation (0.02% w/w) caused a more pronounced increase in cerebellar saringosterol concentration (from 1.58 to 7.38 ng/mg), despite a tenfold lower dietary dose. These results highlight the relatively poor CNS penetration of fucosterol, likely due to its hydrophobic Δ24-unsaturated side chain, similar to cholesterol (Saeed et al., 2014). Consequently, the observed transcriptional changes in the hippocampus are unlikely to result from major alterations in local sterol levels. Instead, fucosterol may modulate neural pathways related to neuronal structure, synaptic signaling, and plasticity, through a small fraction that penetrates the brain or via indirect systemic mechanisms.

Fucosterol and saringosterol also differentially modulated bile acid precursors, suggesting divergent influences on cholesterol elimination pathways. Saringosterol supplementation increased hepatic 7α-OHC and serum 27-OHC, both key intermediates in bile acid synthesis. These oxysterols not only promote bile acid conversion and cholesterol excretion, but also function as endogenous LXR ligands and negative regulators of cholesterol biosynthesis via INSIG binding and SREBP2 suppression (Björkhem, 2009; Ma et al., 2022). In contrast, fucosterol decreased the hepatic and serum concentrations of multiple bile acid precursors, including 7α-OHC, 27-OHC, and 5α-cholestanol. This was accompanied by a decrease in hepatic cholesterol levels, which may reflect enhanced conversion to bile acids and subsequent excretion into the intestine. Fucosterol also reduced serum and hepatic phytosterol concentrations, as well as the ratios of campesterol, stigmasterol, and 5α-cholestanol to cholesterol, indirect markers of reduced intestinal sterol absorption (Miettinen et al., 1989). These effects may be partially mediated by LXR-induced activation of ABCG5 and ABCG8, which promote biliary sterol secretion (Ikeda et al., 1988; Yu et al., 2003). Thus, saringosterol appears to primarily modulate cholesterol metabolism via LXR activation and feedback inhibition through oxysterols, whereas fucosterol likely facilitated cholesterol clearance, indicated by reduced hepatic and serum phytosterol and oxysterol levels.

Our data further demonstrate that both fucosterol and saringosterol, though to a limited extent, enhance cholesterol efflux from THP-1-derived macrophages. Enhanced cholesterol efflux reduces intracellular cholesterol accumulation, a key driver of macrophage-mediated inflammation in diseases such as atherosclerosis and AD (Tall and Yvan-Charvet, 2015). Consistently, saringosterol as well as desmosterol and the DHCR24 inhibitor SH42—which promotes intracellular desmosterol accumulation—reduced LPS-induced TNFα and IL-6 expression, likely through LXR activation. LXR activation besides facilitating cholesterol efflux, also suppresses NF-κB-dependent transcription via SUMOylation-dependent recruitment of corepressors to NF-κB target genes, further repressing inflammation (Treuter and Venteclef, 2011; Bi et al., 2016). On the other hand, fucosterol did not significantly modulate TNF-α, IL-6, IL-1β, or IL-10 production in THP-1-derived macrophages, which appears inconsistent with previous findings that attributed anti-inflammatory properties to this compound (Li et al., 2015; Mo et al., 2018). This discrepancy may arise from differences in experimental context, including cell type–specific responsiveness to inflammatory stimuli and variations in fucosterol exposure dose or duration (Yoo et al., 2012; Jayawardena et al., 2020). For example, THP-1-derived human macrophages and RAW264.7 mouse macrophages differ in baseline NF-κB activity, sterol uptake, and metabolism, which can influence intracellular fucosterol accumulation and downstream LXR activation. Additionally, prior studies often employed higher fucosterol concentrations (10–50 µM) (Yoo et al., 2012), facilitating stronger LXR activation and more pronounced suppression of pro-inflammatory cytokines such as TNF-α, IL-6, and IL-1β following LPS stimulation. Therefore, the modest anti-inflammatory response observed here likely reflects both lower intracellular accumulation and inherent differences in cellular responsiveness.

Importantly, neither saringosterol nor fucosterol induced the expression of lipogenic genes such as SREBF1 or SCD1 in HepG2 cells, nor did fucosterol administration to mice elevate hepatic or serum TG levels, in line with previous findings with 24(S)-saringosterol (Martens et al., 2021). This suggests that both sterols activate LXRs without triggering lipogenesis, a key limitation of most conventional synthetic LXR agonists such as T0901317, highlighting their therapeutic potential in lipid disorders.

Transcriptomic profiling highlights that fucosterol and saringosterol exert distinct modulatory effects in the hippocampus. Fucosterol primarily modulates neuronal plasticity, dendritic spine formation, and hormone-related signaling, whereas saringosterol preferentially regulates proteostasis, RNA metabolism, and neurodegeneration-related pathways, consistent with its potent LXR agonist activity in vitro. These differences may reflect their structural divergence and differential LXR-binding capacities, and point to potentially complementary neuroprotective mechanisms of the two phytosterols. Neither fucosterol nor saringosterol significantly altered brain cholesterol levels, consistent with the tight regulation of CNS cholesterol homeostasis (Balazs et al., 2004; Zhang and Liu, 2015). Their neuroprotective effects therefore likely arise from modulation of neuronal signaling, lipid metabolic networks, and inflammatory pathways rather than direct changes in cholesterol content. Complementary in silico target prediction using PharmMapper identified broader systemic targets, including nuclear receptor signaling and sterol metabolism. Together, these complementary approaches uncover both shared and distinct biological actions of fucosterol and saringosterol, providing a mechanistic basis for their potential therapeutic utility in lipid- and inflammation-associated CNS disorders.

This study has some limitations. The in vitro studies have been conducted in cell lines of different origins that may not fully reflect the in vivo setting. Secondly, the in vivo experiments were conducted in wild-type mice, which may not fully capture the pathological context of neurodegenerative diseases such as AD. Additionally, the duration of dietary supplementation was relatively short and longer-term studies are needed to evaluate the sustained effects and potential clinical relevance of these marine sterols.

5 Conclusion

Brown seaweed sterols fucosterol and saringosterol exert distinct yet complementary effects on cholesterol metabolism and LXR activation. Saringosterol functions as a potent direct LXR agonist with higher brain bioavailability and modulates neurodegeneration-associated pathways, whereas fucosterol primarily influences cholesterol homeostasis by elevating intracellular desmosterol and enhancing cholesterol efflux to HDL. Saringosterol, but not fucosterol, suppressed pro-inflammatory cytokines without inducing lipogenic gene expression, highlighting its therapeutic potential. These findings advance our understanding of their mechanistic roles and support further investigation into their application for neurodegenerative and cardiometabolic diseases.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Ethics statement

The animal procedures were approved by the Ethical Committee for Animal Experiments of Hasselt University (fucosterol trial: protocol ID202249) and the Animal Ethics Committee of the University of Groningen (saringosterol trial: protocol ID AVD10500202115290), in accordance with institutional guidelines. The study was conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements.

Author contributions

MM: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Supervision, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. NZ: Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. NM: Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. YL: Investigation, Validation, Visualization, Writing – review & editing. GV: Investigation, Validation, Writing – review & editing. FL: Investigation, Methodology, Writing – review & editing. SF: Investigation, Writing – review & editing, Validation. MC: Investigation, Validation, Writing – review & editing. LV: Methodology, Writing – review & editing. TV: Methodology, Conceptualization, Resources, Writing – original draft. MS: Investigation, Writing – review & editing. FK: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Writing – review & editing. JJ: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Methodology, Resources, Writing – review & editing. VB: Formal analysis, Writing – review & editing. MP: Investigation, Validation, Writing – review & editing. FZ: Methodology, Writing – review & editing. MA: Methodology, Writing – review & editing. HL: Funding acquisition, Methodology, Resources, Supervision, Conceptualization, Project administration, Writing – review & editing. DL: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Supervision, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. This research was funded by the Dutch Research Council (NWO-TTW) (#16437), the Alzheimer Nederland and Alzheimer Forschung Initiative (#AFI-22034CB, #WE.03-2018-06 AN, #WE.03-2022-06, and #WE. 15-2021-08). This work was supported by NextGenerationEU (NGEU), the MIUR Dipartimenti di Eccellenza 2023–2027 (to Department of Food and Drug, University of Parma, Parma, Italy), the National Recovery and Resilience Plan (NRRP), M4 C2 Investment 1.3—Project code PE0000006 (MNESYS). The authors acknowledge the financial support from the Dutch Research Council (NWO), Alzheimer Nederland, Alzheimer Forschung Inititiative, National Natural Science Foundation of China, and China Scholarship Council (File No. 201906330056).

Acknowledgments

Special thanks to Milaine Hovingh and Niels Kloosterhuis (University Medical Center Groningen, The Netherlands) for their excellent technical assistance. The experimental work was carried out at Erasmus MC, Ocean University of China, University Hospital Bonn, Hasselt University, University of Parma, University of Groningen, and the Netherlands Organization for Applied Scientific Research (TNO), while the part data analysis and manuscript preparation were completed at Guangzhou Medical University. The authors are grateful to these institutions for their support.

Conflict of interest

HL holds patents for the synthesis method of saringosterol from hyodeoxycholic acid Chinese Patent Application No. CN202111052828.8 and for the use of saringosterol as an LXR agonist in the treatment of LXRβ-related diseases, including atherosclerosis, diabetes, and Alzheimer’s disease Chinese Patent Application No. CN201210302962.3.

The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fmars.2025.1728727/full#supplementary-material

References

Ahmed Z., Zeeshan S., Huber C., Hensel M., Schomburg D., Münch R., et al. (2014). ‘Isotopo’ a database application for facile analysis and management of mass isotopomer data. Database: J. Biol. Database Curation 2014, 1–8. doi: 10.1093/database/bau077

Balazs Z., Panzenboeck U., Hammer A., Sovic A., Quehenberger O., Malle E., et al. (2004). Uptake and transport of high-density lipoprotein (HDL) and HDL-associated α-tocopherol by an in vitro blood–brain barrier model. J Neurochem. 89, 939–950. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2004.02373.x

Bi X., Song J., Gao J., Zhao J., Wang M., Scipione C. A., et al. (2016). Activation of liver X receptor attenuates lysophosphatidylcholine-induced IL-8 expression in endothelial cells via the NF-κB pathway and SUMOylation. J. Cell. Mol. Med. 20, 2249–2258. doi: 10.1111/jcmm.12903

Bilotta M. T., Petillo S., Santoni A., and Cippitelli M. (2020). Liver X receptors: regulators of cholesterol metabolism, inflammation, autoimmunity, and cancer. Front. Immunol. 11, 584303. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2020.584303

Björkhem I. (2009). Are side-chain oxidized oxysterols regulators also in vivo? J. Lipid Res. 50 Suppl, S213–S218. doi: 10.1194/jlr.R800025-JLR200

Bligh E. G. and Dyer W. J. (1959). A rapid method of total lipid extraction and purification. Can. J. Biochem. Physiol. 37, 911–917. doi: 10.1139/y59-099

Bogie J., Hoeks C., Schepers M., Tiane A., Cuypers A., Leijten F., et al. (2019). Dietary Sargassum fusiforme improves memory and reduces amyloid plaque load in an Alzheimer’s disease mouse model. Sci. Rep. 9, 4908. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-41399-4

Cha J. Y. and Repa J. J. (2007). The liver X receptor (LXR) and hepatic lipogenesis. The carbohydrate-response element-binding protein is a target gene of LXR. J. Biol. Chem. 282, 743–751. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M605023200

Chen Z., Liu J., Fu Z., Ye C., Zhang R., Song Y., et al. (2014). 24 (S)-Saringosterol from edible marine seaweed Sargassum fusiforme is a novel selective LXRβ agonist. J. Agric. Food Chem. 62, 6130–6137. doi: 10.1021/jf500083r

Choi J. S., Han Y. R., Byeon J. S., Choung S. Y., Sohn H. S., and Jung H. A. (2015). Protective effect of fucosterol isolated from the edible brown algae, Ecklonia stolonifera and Eisenia bicyclis, on tert-butyl hydroperoxide- and tacrine-induced HepG2 cell injury. J. Pharm. Pharmacol. 67, 1170–1178. doi: 10.1111/jphp.12404

Fernández C., Suárez Y., Ferruelo A. J., Gómez-Coronado D., and Lasunción M. A. (2002). Inhibition of cholesterol biosynthesis by Delta22-unsaturated phytosterols via competitive inhibition of sterol Delta24-reductase in mammalian cells. Biochem. J. 366, 109–119. doi: 10.1042/BJ20011777

Fitz N. F., Nam K. N., Koldamova R., and Lefterov I. (2019). Therapeutic targeting of nuclear receptors, liver X and retinoid X receptors, for Alzheimer’s disease. Br. J. Pharmacol. 176, 3599–3610. doi: 10.1111/bph.14668

Gkiouli M., Biechl P., Eisenreich W., and Otto A. M. (2019). Diverse roads taken by 13C-glucose-derived metabolites in breast cancer cells exposed to limiting glucose and glutamine conditions. Cells 8, 1113. doi: 10.3390/cells8101113

Hong C. and Tontonoz P. (2014). Liver X receptors in lipid metabolism: opportunities for drug discovery, Nature reviews. Drug Discov. 13, 433–444. doi: 10.1038/nrd4280

Ikeda I., Tanaka K., Sugano M., Vahouny G. V., and Gallo L. L. (1988). Inhibition of cholesterol absorption in rats by plant sterols. J. Lipid Res. 29, 1573–1582. doi: 10.1016/S0022-2275(20)38403-0

Im S. S. and Osborne T. F. (2011). Liver x receptors in atherosclerosis and inflammation. Circ. Res. 108, 996–1001. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.110.226878

Jayawardena T. U., Sanjeewa K. K. A., Lee H. G., Nagahawatta D. P., Yang H. W., Kang M. C., et al. (2020). Particulate Matter-Induced Inflammation/Oxidative Stress in Macrophages: Fucosterol from Padina boryana as a Potent Protector, Activated via NF-κB/MAPK Pathways and Nrf2/HO-1 Involvement. Mar. Drugs 18, 628. doi: 10.3390/md18120628

Körner A., Zhou E., Müller C., Mohammed Y., Herceg S., Bracher F., et al. (2019). Inhibition of Δ24-dehydrocholesterol reductase activates pro-resolving lipid mediator biosynthesis and inflammation resolution. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. United States America 116, 20623–20634. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1911992116

Lütjohann D., Brzezinka A., Barth E., Abramowski D., Staufenbiel M., von Bergmann K., et al. (2002). Profile of cholesterol-related sterols in aged amyloid precursor protein transgenic mouse brain. J Lipid Res. 43, 1078–1085. doi: 10.1194/jlr.m200071-jlr200

Li Y., Li X., Liu G., Sun R., Wang L., Wang J., et al. (2015). Fucosterol attenuates lipopolysaccharide-induced acute lung injury in mice. J. Surg. Res. 195, 515–521. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2014.12.054

Luu W., Zerenturk E. J., Kristiana I., Bucknall M. P., Sharpe L. J., and Brown A. J. (2014). Signaling regulates activity of DHCR24, the final enzyme in cholesterol synthesis. J. Lipid Res. 55, 410–420. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M043257

Ma L., Cho W., and Nelson E. R. (2022). Our evolving understanding of how 27-hydroxycholesterol influences cancer. Biochem. Pharmacol. 196, 114621. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2021.114621

Mackay D. S., Jones P. J., Myrie S. B., Plat J., and Lütjohann D. J. (2014). Methodological considerations for the harmonization of non-cholesterol sterol bio-analysis. J Chromatogr B Analyt Technol Biomed Life Sci. 957, 116–122. doi: 10.1016/j.jchromb.2014.02.052

Martens N., Schepers M., Zhan N., Leijten F., Voortman G., Tiane A., et al. (2021). 24 (S)-Saringosterol prevents cognitive decline in a mouse model for Alzheimer’s disease. Mar. Drugs. 19, 190. doi: 10.3390/md19040190

Martens N., Zhan N., Yam S. C., Leijten F. P. J., Palumbo M., Caspers M., et al. (2024). Supplementation of seaweed extracts to the diet reduces symptoms of alzheimer’s disease in the APPswePS1ΔE9 mouse model. Nutrients. 16, 1614. doi: 10.3390/nu16111614

Meinita M. D. N., Harwanto D., Tirtawijaya G., Negara B., Sohn J. H., Kim J. S., et al. (2021). Fucosterol of marine macroalgae: bioactivity, safety and toxicity on organism. Mar. Drugs 19, 545. doi: 10.3390/md19100545

Miettinen T. A., Tilvis R. S., and Kesäniemi Y. A. (1989). Serum cholestanol and plant sterol levels in relation to cholesterol metabolism in middle-aged men. Metabolism: Clin. Exp. 38, 136–140. doi: 10.1016/0026-0495(89)90252-7

Mo W., Wang C., Li J., Chen K., Xia Y., Li S., et al. (2018). Fucosterol protects against concanavalin A-induced acute liver injury: focus on P38 MAPK/NF-κB pathway activity. Gastroenterol. Res. Pract. 2018, 2824139. doi: 10.1155/2018/2824139

Moutinho M. and Landreth G. E. (2017). Therapeutic potential of nuclear receptor agonists in Alzheimer’s disease. J. Lipid Res. 58, 1937–1949. doi: 10.1194/jlr.R075556

Müller C., Hemmers S., Bartl N., Plodek A., Körner A., Mirakaj V., et al. (2017). New chemotype of selective and potent inhibitors of human delta 24-dehydrocholesterol reductase. Eur. J. medicinal Chem. 140, 305–320. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2017.08.011

Muse E. D., Yu S., Edillor C. R., Tao J., Spann N. J., Troutman T. D., et al. (2018). Cell-specific discrimination of desmosterol and desmosterol mimetics confers selective regulation of LXR and SREBP in macrophages. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. United States America 115, E4680–E4689. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1714518115

Oh J. H., Choi J. S., and Nam T.-J. (2018). Fucosterol from an edible brown alga Ecklonia stolonifera prevents soluble amyloid beta-induced cognitive dysfunction in aging rats. Mar Drugs. 16, 368. doi: 10.3390/md16100368

Saeed A. A., Genové G., Li T., Lütjohann D., Olin M., Mast N., et al. (2014). Effects of a disrupted blood-brain barrier on cholesterol homeostasis in the brain. J. Biol. Chem. 289, 23712–23722. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M114.556159

Šošić-Jurjević B., Lütjohann D., Renko K., Filipović B., Radulović N., Ajdžanović V., et al. (2019). The isoflavones genistein and daidzein increase hepatic concentration of thyroid hormones and affect cholesterol metabolism in middle-aged male rats, The Journal of steroid biochemistry and molecular biology. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 190, 1–10. doi: 10.1016/j.jsbmb.2019.03.009

Spann N. J., Garmire L. X., McDonald J. G., Myers D. S., Milne S. B., Shibata N., et al. (2012). Regulated accumulation of desmosterol integrates macrophage lipid metabolism and inflammatory responses. Cell 151, 138–152. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.06.054

Tall A. R. and Yvan-Charvet L. (2015). Cholesterol, inflammation and innate immunity, Nature reviews. Immunology 15, 104–116. doi: 10.1038/nri3793

Treuter E. and Venteclef N. (2011). Transcriptional control of metabolic and inflammatory pathways by nuclear receptor SUMOylation. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1812, 909–918. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2010.12.008

Turri M., Conti E., Pavanello C., Gastoldi F., Palumbo M., Bernini F., et al. (2023). Plasma and cerebrospinal fluid cholesterol esterification is hampered in Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimer’s Res. Ther. 15, 95. doi: 10.1186/s13195-023-01241-6

Vanbrabant K., Van Meel D., Kerksiek A., Friedrichs S., Dubbeldam M., Schepers M., et al. (2021). 24(R, S)-Saringosterol - From artefact to a biological medical agent. J. Steroid Biochem. Mol. Biol. 212, 105942. doi: 10.1016/j.jsbmb.2021.105942

Vanmierlo T., Rutten K., Dederen J., Bloks V. W., Kuipers F., Kiliaan A., et al. (2011). Liver X receptor activation restores memory in aged AD mice without reducing amyloid. Neurobiol. Aging 32, 1262–1272. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2009.07.005

Vaughan A. M. and Oram J. F. (2006). ABCA1 and ABCG1 or ABCG4 act sequentially to remove cellular cholesterol and generate cholesterol-rich HDL. J. Lipid Res. 47, 2433–2443. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M600218-JLR200

Wang X., Pan C., Gong J., Liu X., and Li H. (2016). Enhancing the enrichment of pharmacophore-based target prediction for the polypharmacological profiles of drugs. J. Chem. Inf. modeling 56, 1175–1183. doi: 10.1021/acs.jcim.5b00690

Wang X., Shen Y., Wang S., Li S., Zhang W., Liu X., et al. (2017). PharmMapper 2017 update: a web server for potential drug target identification with a comprehensive target pharmacophore database. Nucleic Acids Res. 45, W356–w360. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkx374

Yan Y., Niu Z., Wang B., Zhao S., Sun C., Wu Y., et al. (2021). Saringosterol from sargassum fusiforme modulates cholesterol metabolism and alleviates atherosclerosis in ApoE-deficient mice. Mar Drugs. 19, 485. doi: 10.3390/md19090485

Yang C., McDonald J. G., Patel A., Zhang Y., Umetani M., Xu F., et al. (2006). Sterol intermediates from cholesterol biosynthetic pathway as liver X receptor ligands. J. Biol. Chem. 281, 27816–27826. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M603781200

Yoo M. S., Shin J. S., Choi H. E., Cho Y. W., Bang M. H., Baek N. I., et al. (2012). Fucosterol isolated from Undaria pinnatifida inhibits lipopolysaccharide-induced production of nitric oxide and pro-inflammatory cytokines via the inactivation of nuclear factor-κB and p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase in RAW264.7 macrophages. Food Chem. 135, 967–975. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2012.05.039

Yu L., York J., von Bergmann K., Lutjohann D., Cohen J. C., and Hobbs H. H. (2003). Stimulation of cholesterol excretion by the liver X receptor agonist requires ATP-binding cassette transporters G5 and G8. J. Biol. Chem. 278, 15565–15570. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M301311200

Zhan N., Wang B., Martens N., Liu Y., Zhao S., Voortman G., et al. (2023). Identification of side chain oxidized sterols as novel liver X receptor agonists with therapeutic potential in the treatment of cardiovascular and neurodegenerative diseases. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 24, 1290. doi: 10.3390/ijms24021290

Zhang J. and Liu Q. (2015). Cholesterol metabolism and homeostasis in the brain. Protein Cell 6, 254–264. doi: 10.1007/s13238-014-0131-3

Zhang X., McDonald J. G., Aryal B., Canfrán-Duque A., Goldberg E. L., Araldi E., et al. (2021). Desmosterol suppresses macrophage inflammasome activation and protects against vascular inflammation and atherosclerosis, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 118. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 118, e2107682118. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2107682118

Keywords: fucosterol, saringosterol, liver X receptors, cholesterol homeostasis, Alzheimer’s disease

Citation: Zhan N, Martens N, Li Y, Voortman G, Leijten F, Friedrichs S, Caspers MPM, Verschuren L, Vanmierlo T, Smit M, Kuipers F, Jonker JW, Bloks VW, Palumbo M, Zimetti F, Adorni MP, Liu H, Lütjohann D and Mulder MT (2025) Divergent regulation of cellular cholesterol metabolism by seaweed-derived fucosterol and saringosterol. Front. Mar. Sci. 12:1728727. doi: 10.3389/fmars.2025.1728727

Received: 20 October 2025; Accepted: 17 November 2025; Revised: 14 November 2025;

Published: 02 December 2025.

Edited by:

Lior Guttman, University of Haifa, IsraelReviewed by:

Dorit Avni, Migal - Galilee Research Institute, IsraelXue Xiaoyong, Beijing University of Chinese Medicine, China

Copyright © 2025 Zhan, Martens, Li, Voortman, Leijten, Friedrichs, Caspers, Verschuren, Vanmierlo, Smit, Kuipers, Jonker, Bloks, Palumbo, Zimetti, Adorni, Liu, Lütjohann and Mulder. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Monique T. Mulder, bS50Lm11bGRlckBlcmFzbXVzbWMubmw=

†These authors have contributed equally to this work

‡These authors share last authorship

Na Zhan1,2,3,4†

Na Zhan1,2,3,4† Martien P. M. Caspers

Martien P. M. Caspers Lars Verschuren

Lars Verschuren Tim Vanmierlo

Tim Vanmierlo Johan W. Jonker

Johan W. Jonker Marcella Palumbo

Marcella Palumbo Francesca Zimetti

Francesca Zimetti Maria Pia Adorni

Maria Pia Adorni Hongbing Liu

Hongbing Liu Monique T. Mulder

Monique T. Mulder