Abstract

This study evaluated the effects of a probiotic blend of Bacillus subtilis and Bacillus licheniformis, administered as a water additive, on the growth performance, feed efficiency, body composition, blood biochemistry, histology, gene expression, and resistance to Vibrio parahaemolyticus infection in Sparus aurata fingerlings. A total of 240 healthy fingerlings (6.10 ± 0.06 g) were distributed into 12 tanks (3 tanks per group), with 20 fish per tank. Over a period of 10 weeks, the fish were exposed to four treatments with increasing probiotic concentrations (0, 0.01, 0.02, and 0.03 g/m³), designated as Control, BSL1, BSL2, and BSL3, respectively. The water additives of BSL significantly increased the dissolved oxygen (mg/L) in a dose-dependent manner, while the values of TAN were significantly reduced by increasing the levels of BSL in the water. The NH3 levels were the lowest in BSL2 and BSL3 compared to other groups; however, BSL1 was lower than the control group. The BSL3 group exhibited higher growth performance (final body weight, BWG, survival rate) compared to the other groups (P < 0.05). Adding BSL significantly improved the crude protein and ash content in S. aurata, while it significantly reduced the lipid content (P<0.05). BSL also significantly improved blood hematology parameters (PCV, RBCs, and Hb) and immune responses (phagocytic activity, phagocytic index, lysozyme activity, IgM, total Ig, and WBCs) in a dose-dependent manner (P<0.05) compared to the control group. Blood biochemical parameters (Total protein, albumin, globulin, and glucose), digestive enzymes (amylase and lipase) and antioxidant status (TAC, SOD, CAT) were significantly increased in a dose-dependent manner with increasing levels of probiotic in the water (P<0.05). Liver enzymes and MDA were significantly decreased by BSL-water addition (P<0.05). BSL enhanced the intestinal structure integrity of Sparus aurata. The addition of B. subtilis and B. licheniformis probiotics significantly improved the growth factors (IGF-1, IGF-2, and GHR) and immune-related genes (TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-10) compared to the control group (P<0.05) in a dose-dependent manner. Importantly, probiotic-treated fish exhibited increased resistance to V. parahaemolyticus infection. These findings suggest that water addition of Bacillus subtilis and Bacillus licheniformis probiotics at a concentration of 0.2-0.3g/m3 improved the growth and overall health of Sparus aurata by regulating the immune responses and antioxidant status.

Introduction

The ultimate goal of aquaculture is to achieve high production while maintaining maximum profitability. However, the expansion and intensification of aquaculture operations have generated concerns about physiological state and potential systematic difficulties with disease outbreaks on farms (Chauhan and Singh, 2019; Darafsh et al., 2020). The gilthead seabream (Sparus aurata) is one of the most extensively farmed marine fish, and it is popular with consumers (Torrecillas et al., 2024). Decades of research and development have developed aquaculture techniques for gilthead seabream, resulting in efficient and dependable output. While the gilthead seabream is well-known for its adaptability, growth, nutritional value, and flavor, modern aquaculture procedures have included improvements to improve growth and reduce bacterial infections (Tzortzatos et al., 2024).

Aquaculture has encountered significant challenges due to the widespread occurrence of infectious diseases during fish farming operations. To mitigate bacterial infections, there has been a substantial reliance on antibiotics (Yu et al., 2023). Vibrio parahaemolyticus is commonly found in temperate and tropical coastal waters, is a major pathogen responsible for considerable economic losses in aquaculture production (Millard et al., 2021; Eissa et al., 2025a). Numerous studies have documented antibiotic resistance in Vibrio species, particularly resistance to drugs such as ampicillin, ceftriaxone, and imipenem, which have been isolated from farmed shrimp (Costa et al., 2015). The use of antibiotics, however, poses risks not only to aquatic animals but also to human health, primarily due to the accumulation of antibiotic residues in seafood products (Li et al., 2017; Abd El-Aziz et al., 2024; Eissa et al., 2024b; Mathew et al., 2025). In response, regulatory restrictions on antibiotic use have intensified global research efforts aimed at identifying alternative strategies, particularly the use of functional feed additives. These alternatives include antimicrobial peptides, plant-derived extracts, probiotics, prebiotics, and synbiotics, all of which are being explored for their potential to enhance fish health without the drawbacks of antibiotics.

Among these alternatives, probiotics have gained considerable attention as a sustainable method for controlling infectious diseases in aquaculture (Eissa et al., 2023; Hendam et al., 2023). Their application offers several advantages, including enhancing water quality, promoting digestion, immune function and improving fish growth, Probiotics used in aquaculture water function by altering the microbial ecology, inhibiting infections, and increasing fish health via several processes: competitive pathogen exclusion, antimicrobial compound production, immunological system stimulation, water quality improvement and biofilm formation (Wuertz et al., 2021). By stimulating digestive enzyme activity and supporting a balanced intestinal microbiota, probiotics also contribute to improved feed conversion efficiency in aquatic species, making them a valuable tool for advancing sustainable aquaculture practices. This results in increased nutrient use efficiency, and enhanced fish reproduction (Abuljadayel et al., 2023). Probiotic supplementation also improves appetite and organism digestion (Banerjee and Ray, 2017). Bacillus licheniformis and B. subtilis and bacteria are crucial probiotic additions that help aquatic animals develop and operate normally by delivering vitamins, minerals, and digestive enzymes (Monier et al., 2023). These parameters improve feed consumption, nutritional absorption, and growth performance (Eissa et al., 2024a). Bacillus species offer a range of beneficial effects in aquaculture, notably enhancing feed utilization, producing and releasing exogenous enzymes, and promoting the growth of beneficial gut microbiota that support intestinal physiological functions (Dighiesh et al., 2024). As a result, fish fed diets supplemented with various Bacillus strains have demonstrated notable improvements in growth performance indicators (Soltani et al., 2019; Redhwan et al., 2024). In addition, modulation of the intestinal microbial community—by reducing harmful bacteria and increasing beneficial populations—can strengthen both innate and adaptive immune responses while maintaining intestinal integrity in the host (Hoseinifar et al., 2019). Therefore, this study aims to investigate the impacts of B. subtilis and B. licheniformis probiotics on growth, feed efficiency, physiology, and disease resistance against V. parahaemolyticus in S. aurata fingerlings.

Material and methods

Diet and experimental design

This research was conducted at a private fish farm in Ismailia Province, Egypt. Two hundred forty Sea bream (initial average body weight 6.10 ± 0.06 g) were randomly assigned to four experimental groups (three replicates per treatment). The fish were housed in 12 fiberglass tanks (1 m³) with 20 fish per tank. The control group was without supplementation. The three treatment groups received supplemention with Bacillus species probiotics, which are commercially sold as SANOLIFERPRO-W (a mixture of Bacillus subtilis and B. licheniformis (BSL) at 5 × 105 CFU/g; INVE Aquaculture, Belgium) at levels of 0.01, 0.02, and 0.03 g/m3 water, respectively. Fish were fed on a basal diet consisted of a commercial fish feed sourced from Aller Aqua (ALLER MARINE 42/15 EX) (https://www.aller-aqua.com). The given feed was divided equally into three portions and offered to fish three times a day (8.00, 12.00, and 16.00 h). The chemical composition of this feed was: Crude protein (%); 42, Crude fat (%); 15, NFE (%); 24.4, Ash (%); 7.4, Fibre (%); 3.2, P (%); 1.1, Gross energy (MJ); 20.6 and Digestible energy (MJ); 14.8. Tanks were equipped with compressed air through air stones using air pumps. A daily water change rate of 25% for the control group and 5% for the treatment groups was used throughout the ten-week experiment.

Physico-chemical analyses of water

Water quality was monitored throughout the 10-week experiment. A SensoDirect150 MultiMeter was utilized to evaluate salinity, dissolved oxygen, temperature, and pH. Nitrogenous compounds (NH3 and TAN) were analyzed with a DREL 2000 spectrophotometer (HACH) following (APHA. American Public Health Association, 1998) guidelines.

Fish performance and feed utilization

Fish growth performance and feed utilization were evaluated using standard equations established by (Cho and Kaushik, 1990), and further referenced by (Eissa et al., 2024a). Key parameters assessed included average weight gain (AWG), average daily gain (ADG), specific growth rate (SGR), feed conversion ratio (FCR), and survival rate (%). These metrics are essential for accurately assessing growth efficiency, nutrient utilization, and the overall health and performance of the fish.

Body composition and blood analysis of experimental fish

The proximate composition of the experimental fish crude protein, dry matter, ash, and crude lipid was determined following (AOAC, 2000) protocols. At trial end, three fish per replicate (n = 9 per treatment) were frozen at -18°C for analysis. Dry matter was assessed by drying at 105°C, ash by incineration at 550°C, crude lipid via Soxhlet extraction, and crude protein using the Kjeldahl method (N × 6.25). Dry weight was determined after dehydration at 55°C.

For blood analysis, samples (n = 6 per treatment) were collected after anesthetizing fish with clove oil (5 mL/L). Blood drawn from caudal vessels (2 mL) was divided into two portions: one with anticoagulant (0.1 mL sodium citrate) for hematological assessments (Red blood cells (RBCs), hematocrit, hemoglobin, and phagocytic activity), and another without anticoagulant for serum analysis. The serum was centrifuged at 2000 × g for 10 min. and saved at -20°C for biochemical assessments, including lysozyme activity and immune responses.

Biochemical parameters were analyzed using standard protocols: Red blood cells (RBCs) and Packed Cell Volume (PCV) were determined with a Neubauer hemocytometer, hemoglobin concentration via the cyanomethemoglobin method, and serum aspartate aminotransferase (AST) and alanine aminotransferase (ALT) activities using commercial kits. Total protein, albumin, and globulin levels were measured following established methods.

Hematological assessments included Total immunoglobulin (Ig) and Immunoglobulin M (IgM) levels using assay kits. Serum lysozyme activity was evaluated as per (Ellis, 1990), while phagocytic activity and index were calculated following (Kawahara et al., 1991). Antioxidant activity was measured using diagnostic kits: Superoxide dismutase (SOD) activity via (Nishikimi et al., 1972), catalase (CAT) by (Koroliuk et al., 1988), Malondialdehyde (MDA) following (Buege and Aust, 1978), and Total Antioxidant Capacity (TAC) using (Galaktionova et al., 1998).

Digestive enzyme activities

Amylase and lipase were assayed in serum using Mindray BS-230 kits and a Tecan Infinite 200 PRO spectrophotometer. Amylase activity (405 nm) was determined kinetically based on 2-chloro-4-nitrophenol formation, with results expressed as U/mg protein (Eissa et al., 2025b). Lipase activity (580 nm) was measured using a kinetic assay (García-Meilán et al., 2023), with a buffer containing Tris, taurodeoxycholate, deoxycholate, tartrate, DGGR, CaCl2, mannitol, and colipase (pH 8.3). Lipase activity was also expressed as U/mg protein.

Histological analysis

Anterior intestinal samples from S. aurata (n = 3 per treatment) were carefully collected, tissues were trimmed into small pieces (~1 cm³) before fixation to ensure proper penetration and immediately fixed in 10% buffered neutral formalin for 24 hours. Following fixation, the tissues were dehydrated via a series of ethanol (70%, 80%, 95%, and 100%) (half hour for each conc.), cleared in xylene I, and xylene II (1hour and half for each solu.), and embedded in paraffin wax I, and II (1hour and half for each wax.). Sections of 5 µm thickness were cut using a Leica RM 2155 microtome (Leica, England). These sections were stained routinely with hematoxylin and eosin, then examined under a light microscope according to standard histological procedures (Suvarna et al., 2018).

For histomorphometric analysis, key measurements included villus width (VW), villus height (VL), and absorptive surface area (ASA). Fifty well-oriented villi were selected from each intestinal section, and the values were averaged per fish. Villus height (VL) was measured from the tip to the base, while VW was measured at the midpoint of the villus. The ASA was calculated using the formula: ASA (mm²) = VL × VW, as described by (Mohammady et al., 2021). All measurements were done using a high-resolution light microscope with an HD camera (Leica Microsystems, Germany) and image J analysis software version 1.x.

Relative gene expression analysis

Total RNA was extracted from fish liver tissues (n = 3 per treatment) using a commercial kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA) following the manufacturer’s instructions. DNase treatment was applied during RNA extraction to eliminate any residual genomic DNA contamination. RNA purity and concentration were measured with a NanoDrop Lite spectrophotometer and all samples showed acceptable A260/280 ratios within the 1.8-2.0 range. For cDNA synthesis, 1 µg of RNA was reverse-transcribed using the SuperScript™ III system (Invitrogen, USA) with Oligo-dT primers and stored at -20°C. Gene expression of IGF-1, IGF-2, TNF-α, GHR, IL-10, and IL-1β was quantified by qPCR (SensiFast SYBR Lo-Rox kit, Bioline, UK) under thermal cycling conditions: 95°C for 10 min, 40 cycles of 95°C for 15 s, 60°C for 30 s, and 85°C for 5 min. qPCR was performed using (Applied Biosystems QuantStudio series, QuantStudio 7 Pro) instrument and melting curve was included to confirm the specificity of the amplified products. Expression levels were normalized to EF-1 α using the 2−ΔΔCT method (Table 1).

Table 1

| Gene | Primer Sequence 5´ - 3´ | bp | Accession no/ref. |

|---|---|---|---|

| IGF-1 | F: GGGCGAGCCCAGAGA R: GCCGTAGCCAGGTTTACTGAAATAA |

98 | XM_030440256.1 |

| IGF-2 | F: GTCGGCCACCTCTCTACAG R: TGCTTCCTTGAGACTTCCTGTTTT |

66 | XM_030425968.1 |

| GHR | F: ACCTGTCAGCCACCACATGA R: TCGTGCAGATCTGGGTCGTA |

99 | XM_030417994.1 |

| TNF-α | F: TTCCGACTGGTGGACAATAAG R: GAGATCCTGTGGCTGAGAGG |

143 | XM_030392876.1 |

| IL-1β | F: AGCGCAGTAGAAGAGCGAAC R: CACTCGGACTAAGTGCCTCTG |

117 | XM_030416076.1 |

| IL-10 | F: CTCACATGCAGTCCATCCAG R: TGTGATGTCAAACGGTTGCT |

98 | XM_030420872.1 |

| EF-1 α | F: CTTCAACGCTCAGGTCATCAT R: GCACAGCGAAACGACCAAGGGGA |

263 | XM_030411990.1 |

Primer sequences for the selected genes used in the qPCR analysis.

Insulin growth factor -1(IGF-1), and 2 (IGF-2), Growth honrone recpetor (GHR), Tumor Necrosis Factor-alpha (TNF-α), interluekin-1β (IL-1β), interluekin-10 (IL-10), Eukaryotic translation elongation factor 1 alpha 1 (EF-1 α).

Challenge assay against Vibrio parahaemolyticus

Twenty fish from each treatment group, totaling 80 fish, were placed in 50-liter tanks. Both treated and control groups were exposed to a virulent strain of V. parahaemolyticus (obtained from the Sakha Animal Production Research Station, Egypt) at a concentration of 107 CFU/mL. The bacterial challenge was conducted via immersion in water containing the prepared suspension for 24 hours at 28°C, following the method described by (Balcázar et al., 2007).

Statistical analysis

The Kolmogorov-Smirnov and Levene’s tests were used to check the normal distribution of the data and the homogeneity of variances. All data were analyzed with IBM SPSS Statistics (version 25.0) and are reported as the mean ± SE. To compare means across groups, a one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was employed. Before ANOVA, the assumption of equal variances was verified using Levene’s test. If this assumption was met, post hoc analysis was completed using the LSD test to determine specific group differences. The threshold for statistical significance was set at p < 0.05. The heatmap was visualized using GraphPad Prism 8.

Results

Water quality

The impacts of various BSL (0, 0.01, 0.02, and 0.03 g/m³, designated Control, BSL1, BSL2, and BSL3, respectively) on water quality are explained in Table 2. The water additives of B. subtilis and B. licheniformis significantly increased the dissolved oxygen (mg/L) in a dose-dependent way. In contrast, the values of TAN were significantly reduced by increasing the levels of BSL in the water. The NH3 levels were the lowest in BSL2 and BSL3 compared to other groups; however, BSL1 was lower than the control group. For pH, BSL2 and BSL3 significantly reduced the water pH values compared to the remaining groups. The salinity and temperature of the water were not affected by the administration of B. subtilis and B. licheniformis (Table 2).

Table 2

| Parameters | Control | BSL1 | BSL2 | BSL3 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Salinity (g/L) | 31.85 ± 0.51 | 31.37 ± 0.27 | 31.35 ± 0.34 | 31.33 ± 0.28 |

| Temperature °C | 27.10 ± 0.06 | 27.17 ± 0.03 | 27.10 ± 0.01 | 27.20 ± 0.01 |

| Dissolved oxygen (mg/L) | 7.33 ± 0.02d | 7.44 ± 0.02c | 7.52 ± 0.01b | 7.86 ± 0.02a |

| pH | 8.18 ± 0.01a | 8.17 ± 0.01a | 8.14 ± 0.01b | 8.13 ± 0.01b |

| TAN (mg/L) | 1.20 ± 0.01a | 0.72 ± 0.01b | 0.54 ± 0.01c | 0.45 ± 0.01d |

| NH3 (mg/L) | 0.12 ± 0.01a | 0.07 ± 0.01b | 0.05 ± 0.01c | 0.04 ± 0.01c |

Impacts of B. subtilis and B. licheniformis water additives on water quality parameters in S. aurata over 10 weeks.

Fish were exposed to four treatments with increasing probiotic concentrations (0, 0.01, 0.02, and 0.03 g/m³), designated as Control, BSL1, BSL2, and BSL3, respectively. a-dDifferent letters in each row indicate significant differences between the groups (P < 0.05). Data presented as mean ± SE.

Growth performance and feed efficiency

Supplementation of water treatments with B. subtilis and B. licheniformis showed significant effects on feed efficiency and growth performance in Sparus aurata (Table 3). The BSL3 group exhibited higher final body weight, weight gain, specific growth rate (SGR), and average daily gain (ADG) compared to the other groups (P < 0.05). The feed conversion ratio (FCR) was higher in the control group, with the lowest values observed in the BSL3 group (P < 0.05). Feed intake decreased in the BSL3 group but increased in the other experimental groups (P > 0.05). The survival rate was improved by BSL administration. Overall, supplementing S. aurata water with BSL significantly enhanced growth indices and feed efficiency, particularly at a dose of 0.03 g/m3 water.

Table 3

| Parameters | Control | BSL1 | BSL2 | BSL3 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Initial fish weight(g) | 6.07 ± 0.03 | 6.10 ± 0.06 | 6.10 ± 0.06 | 6.07 ± 0.03 |

| Final fish weight (g) | 31.40 ± 0.51c | 35.33 ± 0.52b | 36.27 ± 0.55b | 38.13 ± 0.20a |

| Weight gain | 25.33 ± 0.49c | 29.23 ± 0.47b | 30.17 ± 0.50b | 32.07 ± 0.18a |

| SGR (%/fish/day) | 2.35 ± 0.02d | 2.51 ± 0.01c | 2.55 ± 0.01b | 2.63 ± 0.01a |

| Feed intake (g) | 38.22 ± 0.21a | 38.43 ± 0.36a | 38.43 ± 0.36a | 38.22 ± 0.21a |

| FCR (g feed/g gain) | 1.51 ± 0.02a | 1.31 ± 0.01b | 1.27 ± 0.01b | 1.19 ± 0.00c |

| ADG (g) | 0.36 ± 0.01c | 0.42 ± 0.01b | 0.43 ± 0.01b | 0.46 ± 0.00a |

| Initial Fish number (n) | 20.00 ± 0.01 | 20.00 ± 0.00 | 20.00 ± 0.00 | 20.00 ± 0.00 |

| Fish final number (n) | 18.33 ± 0.33a | 19.33 ± 0.67a | 19.00 ± 0.01a | 19.67 ± 0.33a |

| Fish biomass (per 1m3) | 575.57 ± 11.70c | 682.87 ± 22.40b | 689.07 ± 10.54b | 750.07 ± 16.10a |

| Survival rate (%) | 91.67 ± 1.67a | 96.67 ± 3.33a | 95.00 ± 0.01a | 98.33 ± 1.67a |

Impact of B. licheniformis and B. subtilis administered as water additives on the growth indices and feed utilization of S. aurata during a 10-week period.

FCR, Feed conversion ratio; SGR, specific growth rate; ADG, average daily gain. Fish were exposed to four treatments with increasing probiotic concentrations (0, 0.01, 0.02, and 0.03 g/m³), designated as Control, BSL1, BSL2, and BSL3, respectively. a-dDifferent letters in each row indicate significant differences between the groups (P < 0.05). Data presented as mean ± SE.

Approximate body composition analysis

The dry matter was not affected by the water administration of B. licheniformis and B. subtilis probiotics (Table 4). Adding B. licheniformis and B. subtilis probiotics to water significantly improved the crude protein content in S. aurata, with maximum values observed in the BSL3 group. Ash content in all BSL groups was greater compared to the control group (P < 0.05). Lipid content significantly decreased with increasing levels of probiotics in the water (P < 0.05). BSL3 had the lowest lipid content and the highest ash content compared to other groups (P < 0.05).

Table 4

| Parameters | Control | BSL1 | BSL2 | BSL3 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dry matter (%) | 30.52 ± 0.37 | 31.10 ± 0.06 | 31.37 ± 0.45 | 31.30 ± 0.09 |

| Crude protein (%) | 51.92 ± 0.12c | 52.58 ± 0.34b | 52.98 ± 0.11ab | 53.24 ± 0.03a |

| Lipids (%) | 28.62 ± 0.04a | 28.38 ± 0.04b | 28.23 ± 0.02c | 28.10 ± 0.02d |

| Ash (%) | 15.91 ± 0.03d | 16.46 ± 0.03c | 16.87 ± 0.03b | 17.08 ± 0.01a |

Impact of various water additive B.licheniformis and B. subtilis probiotic on approximate body composition analysis of S. aurata for 10 weeks.

Fish were exposed to four treatments with increasing probiotic concentrations (0, 0.01, 0.02, and 0.03 g/m³), designated as Control, BSL1, BSL2, and BSL3, respectively. a-dDifferent letters in each row indicate significant differences between the groups (P < 0.05). Data presented as mean ± SE.

Blood hematology and biochemical parameters

The water addition of combined probiotic B. licheniformis and B. subtilis significantly improved the PCV, RBCs, and Hb in a dose-dependent way (P<0.05) compared to the control group (Table 5). BSL3 exhibited the highest values of PCV, RBCs, and Hb compared to other groups. The values of MCV, MCH, and MCHC were higher in BSL2 and BSL3 groups compared to other groups (P<0.05). BSL1 had greater MCV and MCH than those of the control group (P<0.05). Total protein, albumin, globulin, and glucose were significantly increased in a dose-dependent manner by increasing the levels of probiotic in the water (P<0.05). BSL3 had the highest values of total protein, albumin, and globulin compared to other BSL and control groups (P<0.05). BSL2 and BSL3 showed similar levels of glucose, urea, and creatinine (P>0.05). The addition of probiotics significantly reduced the levels of AST and ALT compared to the control group, with the lowest values shown in BSL3 followed by BSL2 (P<0.05). Urea levels were decreased by the addition of B. licheniformis and B. subtilis (P < 0.05).

Table 5

| Parameters | Control | BSL1 | BSL2 | BSL3 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Blood hematology | ||||

| PCV (%) | 28.81 ± 0.25d | 30.91 ± 0.13c | 34.06 ± 0.10b | 35.92 ± 0.08a |

| RBCs (106/μL) | 2.34 ± 0.01d | 2.39 ± 0.00c | 2.58 ± 0.02b | 2.72 ± 0.01a |

| Hb (g/dL) | 8.87 ± 0.03d | 9.66 ± 0.21c | 11.05 ± 0.05b | 11.75 ± 0.03a |

| MCV (fL) | 122.93 ± 0.91c | 129.51 ± 0.70b | 132.03 ± 0.81a | 132.07 ± 0.46a |

| MCH (pg/cell) | 37.87 ± 0.16c | 40.47 ± 0.86b | 42.83 ± 0.25a | 43.20 ± 0.13a |

| MCHC (g/dL) | 30.81 ± 0.18b | 31.25 ± 0.67b | 32.44 ± 0.04a | 32.71 ± 0.12a |

| Blood biochemical parameters | ||||

| Total protein (g/dL) | 2.95 ± 0.07d | 3.75 ± 0.01c | 4.39 ± 0.04b | 5.32 ± 0.07a |

| Albumin (g/dL) | 1.58 ± 0.05d | 2.14 ± 0.02c | 2.50 ± 0.04b | 2.97 ± 0.06a |

| Globulin (g/dL) | 1.37 ± 0.02d | 1.61 ± 0.02c | 1.89 ± 0.03b | 2.35 ± 0.01a |

| Glucose (mmol/L) | 13.08 ± 0.04c | 14.01 ± 0.14b | 14.57 ± 0.05a | 14.46 ± 0.02a |

| AST (U/L) | 20.98 ± 0.07a | 20.21 ± 0.04b | 19.36 ± 0.31c | 17.78 ± 0.19d |

| ALT (U/L) | 31.43 ± 0.22a | 29.91 ± 0.11b | 29.15 ± 0.16c | 28.27 ± 0.12d |

| Uric acid (mg/dL) | 3.28 ± 0.04a | 2.35 ± 0.05b | 2.18 ± 0.03c | 1.73 ± 0.05d |

| Urea (mg/dL) | 102.18 ± 0.17a | 101.97 ± 0.23a | 100.55 ± 0.06b | 100.08 ± 0.18b |

| Creatinine (mg/dL) | 0.49 ± 0.01a | 0.43 ± 0.01b | 0.40 ± 0.00c | 0.38 ± 0.01c |

Impact of B. licheniformis and B. subtilis water additives on the blood hematology and biochemical parameters of S. aurata.

Fish were exposed to four treatments with increasing probiotic concentrations (0, 0.01, 0.02, and 0.03 g/m³), designated as Control, BSL1, BSL2, and BSL3, respectively. a-dDifferent letters in each row indicate significant differences between the groups (P < 0.05). Data presented as mean ± SE.

Immunoglogical parameters

The results in Table 6 indicate that the water additives Bacillus subtilis and B. licheniformis significantly increase the phagocytic activity, phagocytic index, lysozyme (LYZ) activity, IgM, total Ig, and white blood cells (WBCs) compared to the control group. This increase in the investigated immunological parameters of S. aurata was independent (P<0.05). The highest levels for the highest values of immunological parameters of S. aurata were shown with the addition of 0.3 g/m³.

Table 6

| Parameters | Control | BSL1 | BSL2 | BSL3 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Phagocytic activity (%) | 21.47 ± 0.12d | 23.83 ± 0.19c | 25.53 ± 0.41b | 28.27 ± 0.26a |

| Phagocytic index (%) | 2.04 ± 0.02d | 2.15 ± 0.01c | 2.54 ± 0.02b | 3.00 ± 0.04a |

| LYZ activity (Unit/mL) | 0.11 ± 0.01d | 0.15 ± 0.01c | 0.23 ± 0.01b | 0.27 ± 0.01a |

| IgM (ng/mL) | 3.24 ± 0.05d | 4.29 ± 0.03c | 4.61 ± 0.04b | 4.94 ± 0.05a |

| Total Ig (mg/mL) | 1.12 ± 0.01d | 1.27 ± 0.01c | 1.40 ± 0.01b | 1.70 ± 0.01a |

| WBCs (mm3) | 22.48 ± 0.65d | 24.73 ± 0.17c | 26.61 ± 0.41b | 28.61 ± 0.19a |

Effect of various water additive Bacillus subtilis and B. licheniformis probiotic on immunoglogical parameters of S. aurata for 10 weeks.

Fish were exposed to four treatments with increasing probiotic concentrations (0, 0.01, 0.02, and 0.03 g/m³), designated as Control, BSL1, BSL2, and BSL3, respectively. a-dDifferent letters in each row indicate significant differences between the groups (P < 0.05). Data presented as mean ± SE.

Antioxidant biomarkers parameters

Significant reductions in MDA levels were shown in all water additive B. subtilis and B. licheniformis groups (Table 7), with the lowest values shown in BSL2 and BSL3 groups (P < 0.05). In contrast, adding B. subtilis and B. licheniformis at various levels significantly improved the antioxidant status, such as SOD, CAT, and TAC, of S. aurata. The BSL3 group had the greatest values of SOD, CAT, and TAC, followed by BSL2 and BSL1 with statistical differences among all groups (P < 0.05).

Table 7

| Parameters | Control | BSL1 | BSL2 | BSL3 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MDA (nmol/mL) | 23.80 ± 0.38a | 21.00 ± 0.15b | 19.77 ± 0.15c | 19.00 ± 0.25c |

| SOD (U/mg protein) | 2.30 ± 0.12d | 3.20 ± 0.06c | 3.90 ± 0.10b | 4.57 ± 0.03a |

| CAT (U/mg protein) | 1.98 ± 0.07d | 2.40 ± 0.04c | 2.98 ± 0.08b | 3.25 ± 0.01a |

| TAC (mM/L) | 0.40 ± 0.02d | 0.51 ± 0.02c | 0.61 ± 0.03b | 0.67 ± 0.01a |

Effect of various water additive B. subtilis and B. licheniformis probiotic on antioxidant biomarkers parameters of S. aurata for 10 weeks.

Fish were exposed to four treatments with increasing probiotic concentrations (0, 0.01, 0.02, and 0.03 g/m³), designated as Control, BSL1, BSL2, and BSL3, respectively. a-dDifferent letters in each row indicate significant differences between the groups (P < 0.05). Data presented as mean ± SE.

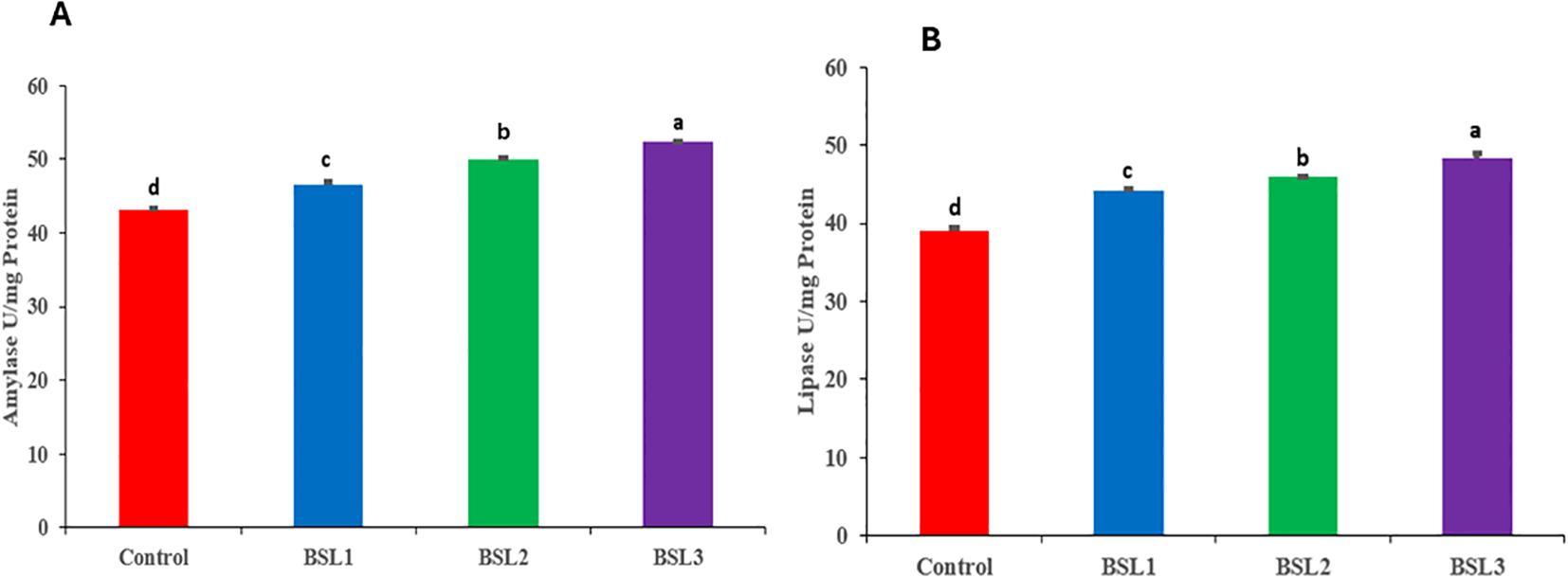

Digestive enzyme activities

Supplementation with combined probiotics at different levels of B. subtilis and B. licheniformis (0.1, 0.2, and 0.3 g/m3) significantly improved the amylase (Figure 1A) and lipase (Figure 1B) activity in Sparus aurata. The high levels of probiotics exhibited the greatest values of lipase and amylase, followed by the BSL2 groups with significant differences (P<0.05).

Figure 1

Effect of various water additives Bacillus subtilis and Bacillus licheniformis probiotics on digestive enzyme activities such as amylase (A) and lipase (B) of Sparus aurata for 10 weeks. Superscripts represent significant (P < 0.05) differences among treatments.

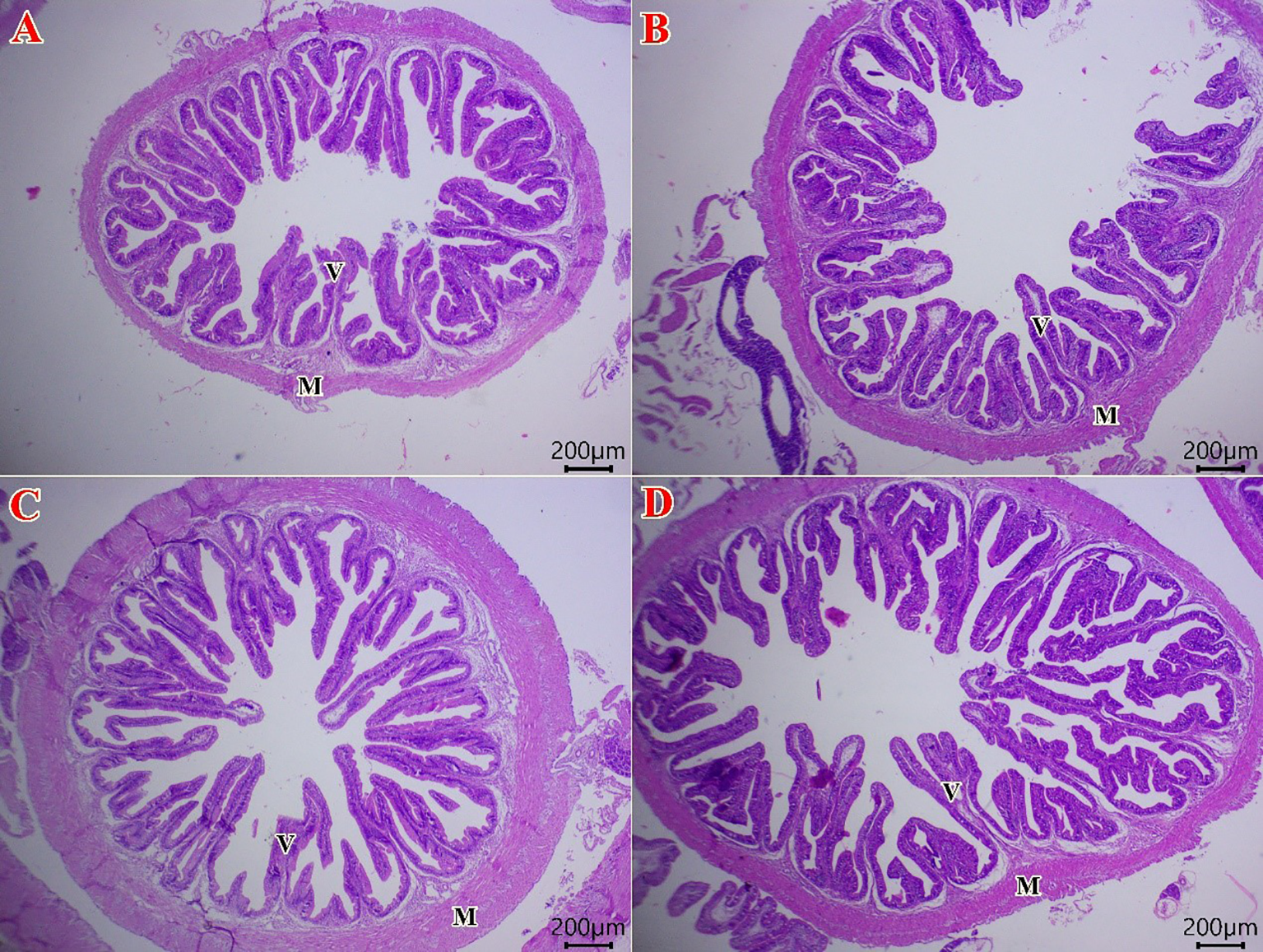

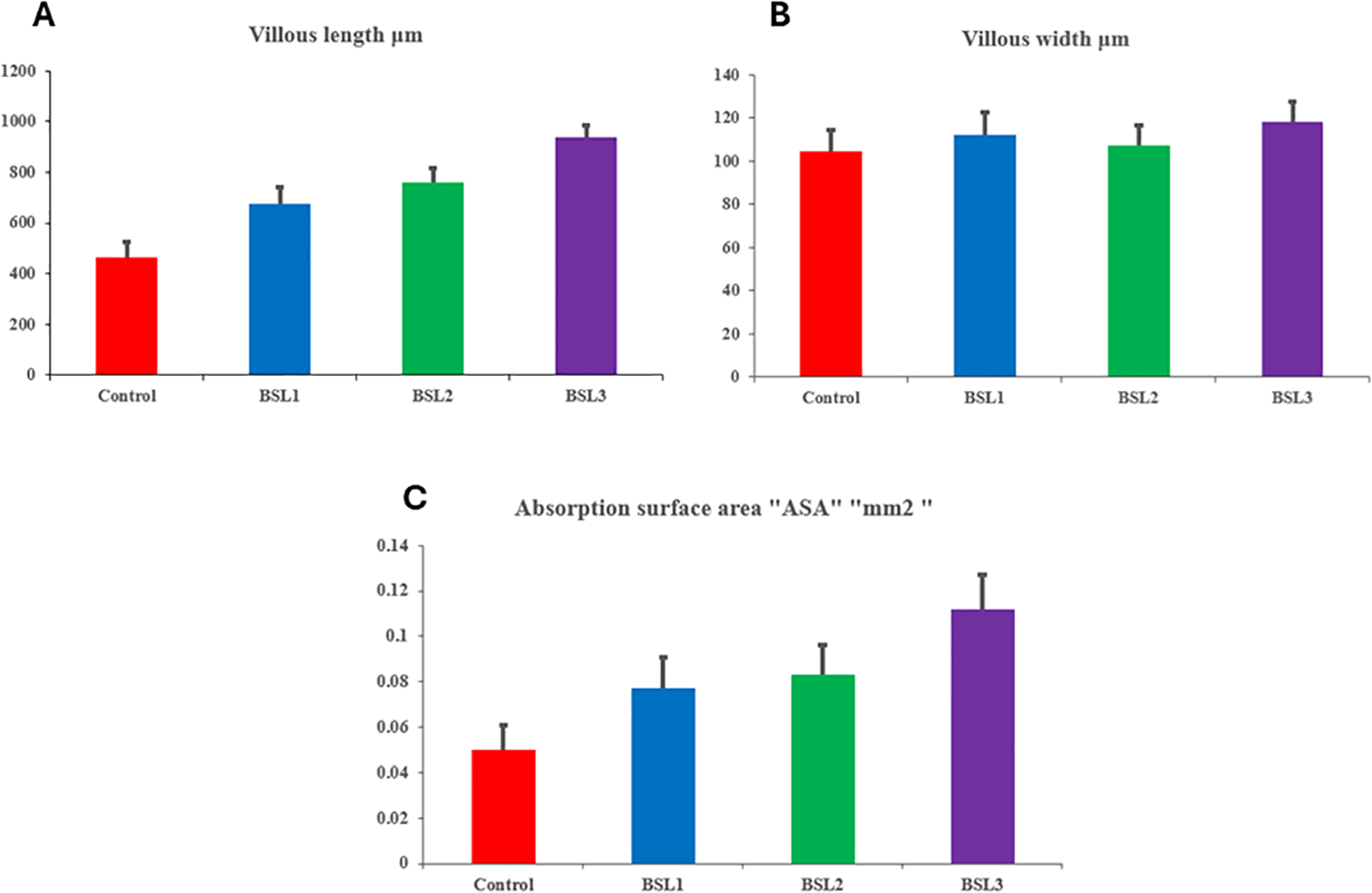

Histological study

All groups of fish intestines in the “control to BSL3” category exhibited normal histological structures (Figure 2). The intestinal villi were lined with simple columnar epithelium, and both the submucosal and muscular layers appeared intact and well-organized, indicating no signs of pathological alterations across the examined groups. Moreover, a gradual improvement in villous length and width was demonstrated from the control group to the BSL3 group, respectively (Figure 2A–D). Figure 3 illustrates the histo-morphometric analysis of villus length (Figure 3A), width (Figure 3B), and absorption surface area (Figure 3C) among different groups. Despite improvements in villus length, width, and absorption surface area in all BSL groups with increasing levels, there were no statistically significant differences among all groups (P > 0.05).

Figure 2

Photomicrograph of H&E stained sections from the intestine of Sparus aurata fish (Scale bar 200 μm). The fish intestine in control group (A) shows the normal histology of a simple columnar epithelial lining intestinal villi (V), submucosa, and muscular layer (M) in all groups from the control group to BSL3 group. There is a gradual improvement in villous length and width in fish treated with 0.1 (B), 0.2 (C), and 0.3 (D) g/m3 of B. subtilis and B. licheniformis probiotic.

Figure 3

The histo-morphometric analysis of villus length (A), width (B), and absorption surface area (C) in of Sparus aurata fish treated with 0.1, 0.2, and 0.3 g/m3 of B. subtilis and B. licheniformis probiotic.

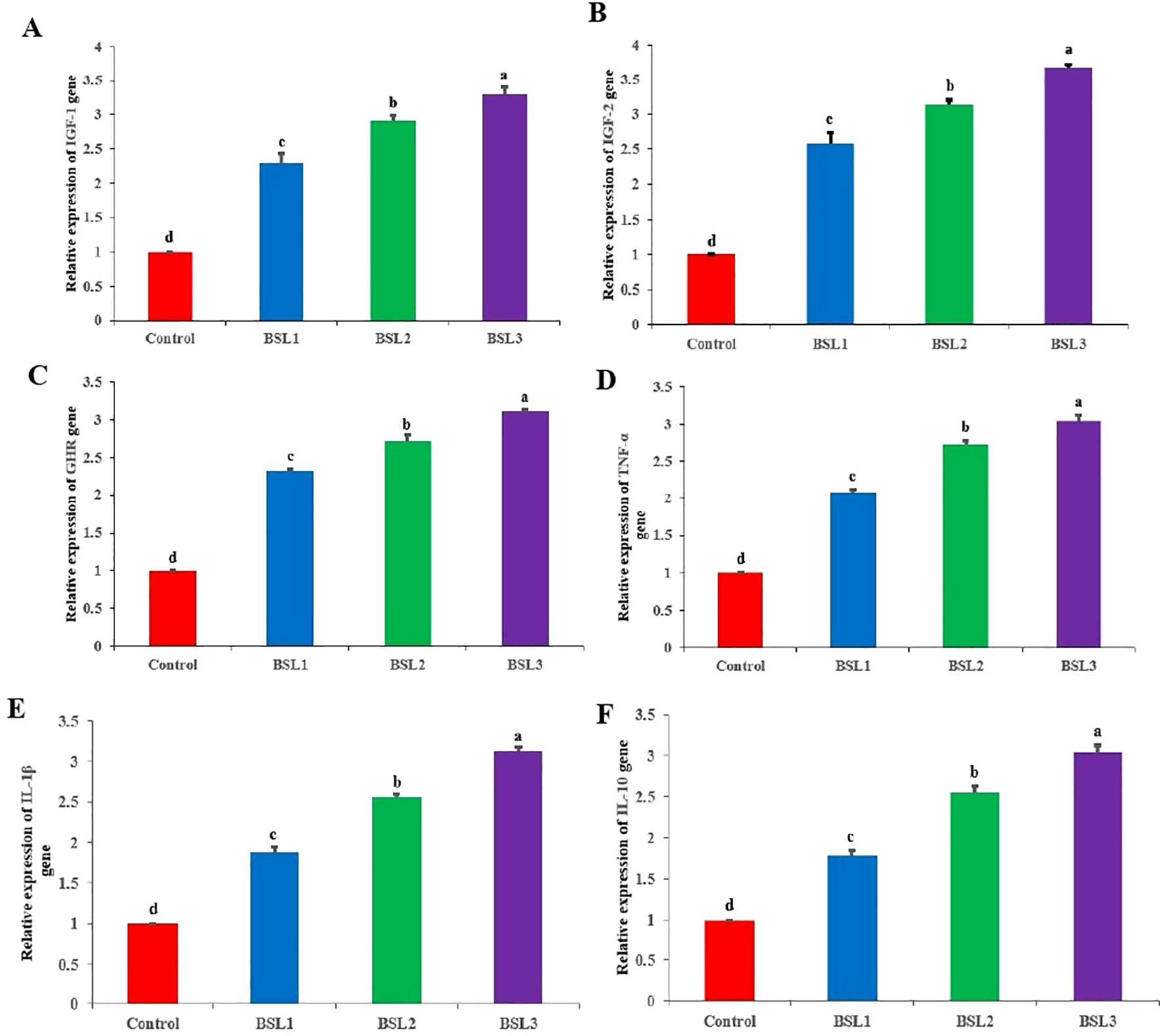

Gene expression

Effect of various water additives B. subtilis and B. licheniformis probiotics on gene expression of Sparus aurata for 10 weeks are shon in Figures 4A–F. These genes include mRNA expressions of growth factors IGF-1 (Figure 4A), IGF-2 (Figure 4B), and GHR (Figure 4C), as well as immune-related genes such as TNF-α (Figure 4D), IL-1β (Figure 4E), and IL-10 (Figure 4F). The addition of B. subtilis and B. licheniformis probiotics significantly improved the growth factors IGF-1 (Figure 4A), IGF-2 (Figure 4B), and GHR compared to the control group (P<0.05) in a dose-dependent manner. It was shown that increasing the levels of B. subtilis and B. licheniformis significantly increased the levels of growth genes (P<0.05) with statistical differences among all groups. The same trend was shown for immune-related genes such as TNF-α (Figure 4D), IL-1β (Figure 4E), and IL-10 (Figure 4F), indicating the growth beneficial effects of probiotics and immune modulatory effects.

Figure 4

Effect of various water additives Bacillus subtilis and Bacillus licheniformis probiotics on gene expression of Sparus aurata for 10 weeks. These genes include mRNA expressions of growth factors IGF-1 (A), IGF-2 (B), and GHR (C), as well as immune-related genes such as TNF-α (D), IL-1β (E), and IL-10 (F). Superscripts represent significant (P < 0.05) differences among treatments.

Challenge assay against Vibrio parahaemolyticus

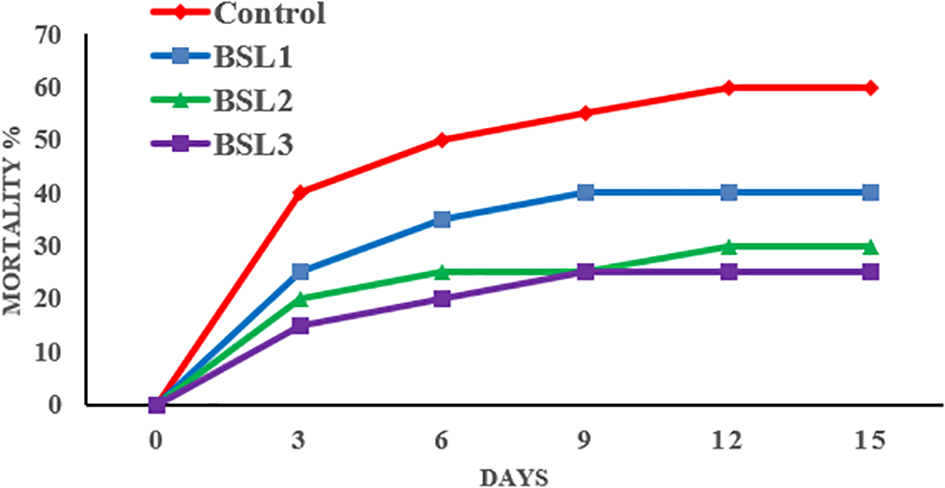

In the post-challenge period, fish reared in water with BSL showed improved immune status, resulting in reduced mortality rates in the treated groups (Figure 5). BSL3 exhibited significantly lower mortality (25%), followed by BSL2 (30%), BSL1 (40%), and Control (60%).

Figure 5

Effect of various water additive B. licheniformis and B. subtilis probiotic on resistance of S. aurata against Vibrio parahaemolyticus for 15 days.

Correlation analysis

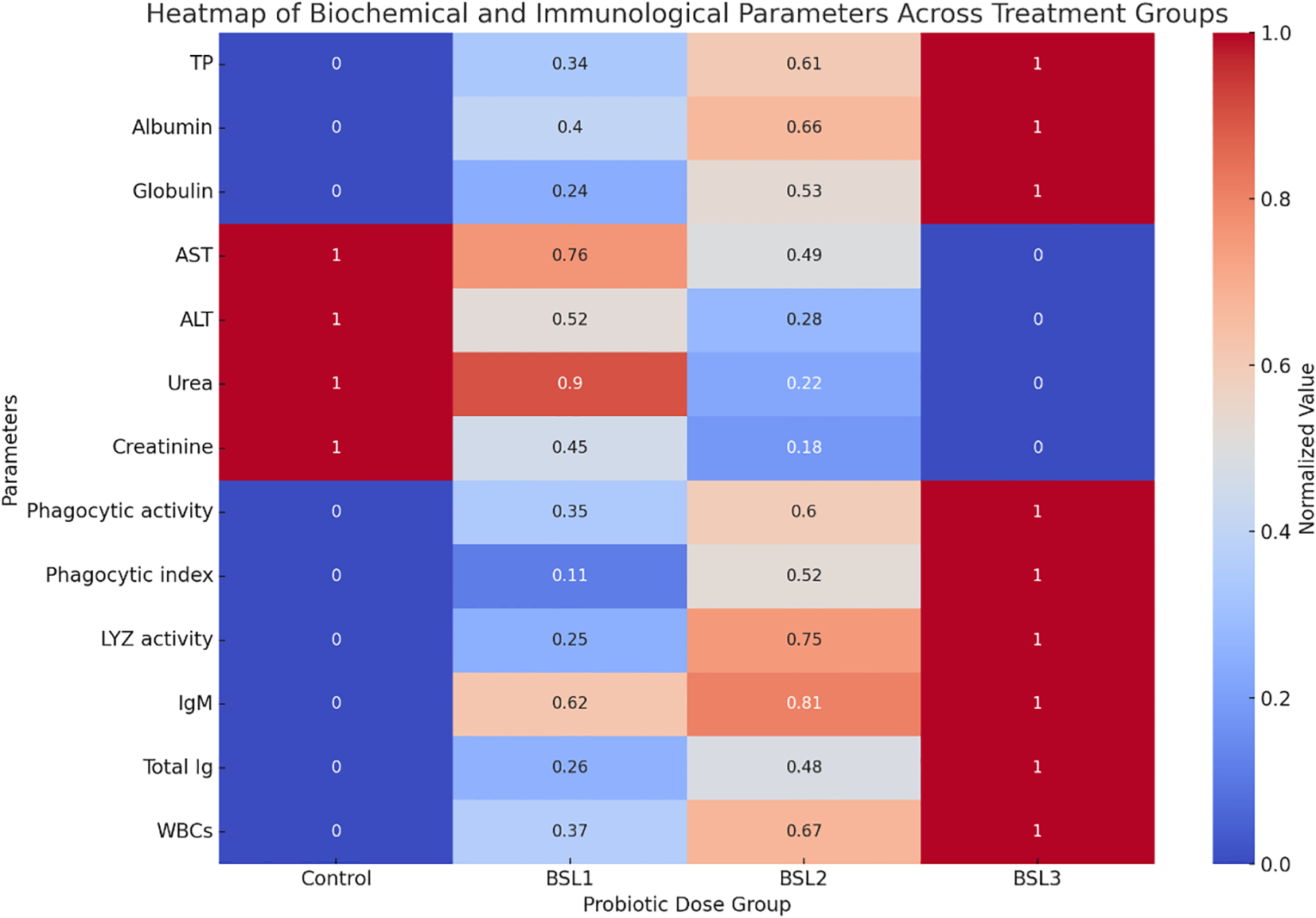

This heatmap illustrates the normalized values of key biochemical parameters (e.g., total protein, albumin, AST, ALT, urea, creatinine) and immunological parameters (e.g., phagocytic activity, lysozyme, immunoglobulins, WBCs) across different probiotic treatments (Control, BSL1, BSL2, BSL3) (Figure 6). The color gradients indicate relative increases or decreases compared to other groups. The BSL3 group exhibits the most favorable biochemical and immunological profile, suggesting improved health status with probiotic supplementation.

Figure 6

Heatmap of biochemical and immunological profiles in sparus aurata across probiotic dose groups. This heatmap illustrates the normalized values of key biochemical parameters (e.g., total protein, albumin, AST, ALT, urea, creatinine) and immunological parameters (e.g., phagocytic activity, lysozyme, immunoglobulins, WBCs) across different probiotic treatments (Control, BSL1, BSL2, BSL3). The color gradients indicate relative increases or decreases compared to other groups. The BSL3 group exhibits the most favorable biochemical and immunological profile, suggesting improved health status with probiotic supplementation.

Discussion

In response to the ban on antibiotics, the use of natural molecules like phytochemicals or probiotics has emerged as a sustainable and environmentally friendly strategy to promote growth performance, enhance immune function, modulate blood health, and improve disease resistance. However, the combined effects of these natural molecules on sea bream blood health, immunity, and growth indices have not been thoroughly investigated.

Water quality is the most important factor affecting fish development and production. The combination of physical and biological components influences water quality (Khademzade et al., 2020). Probiotics play a significant role in improving water quality by reducing the levels of organic contaminants, keeping the water clean, and creating an optimal environment for fish in the pond. Both B. subtilis and B. licheniformis have been found to effectively enhance water quality while maintaining it within acceptable levels for fish farming. Maintaining optimal water quality parameters is essential for promoting growth and reducing disease incidence in fish farming. The high alkalinity and buffering properties of saline water in this study resulted in minimal pH fluctuations, making it an excellent environment for aquaculture (Boyd and Tucker, 1998).

According to the study by (Zhang et al., 2011), the addition of B. licheniformis as a denitrifying bacterium to rearing water effectively reduced toxic compounds such as (TAN and NH3), while also promoting the breakdown of residual feed proteins and starches. Moreover, Bacillus species play a key role in the biodegradation of nitrogenous waste through mineralization processes, thereby contributing to improved water quality (Eissa et al., 2024a). Ensuring good water quality is essential for the survival of aquatic species, especially Broadstock fish, as ammonia and nitrite nitrogen are key indicators in aquaculture. Elevated levels of these compounds can harm cultured animals, making efficient water management vital for production. Introducing beneficial microbial communities helps recycle organic waste and maintain cleaner water (Qiu et al., 2023). Studies have shown that B. subtilis (109 CFU/mL) supplementation significantly lowers total nitrogen and ammonia levels.

Here, adding a Bacillus probiotic mixture to water significantly enhanced seabream growth, likely due to the growth-promoting properties of these bacteria. Similarly, B. licheniformis has been shown to improve weight gain and specific growth rate in prawns (Chen et al., 2020) and Litopenaeus vannamei (Cao et al., 2022). In line with these findings, dietary inclusion of B. subtilis and B. licheniformis blend improved growth and feed efficiency in Kutum fry (Azarin et al., 2015) and Nile tilapia (Abarike et al., 2018). Moreover, studies by (Monier et al., 2023; Eissa et al., 2024a) informed notable improvements in the growth parameters of whiteleg shrimp and red tilapia, respectively, following treatment with these Bacillus strains.

Haemato-biochemical parameters are widely recognized as valuable indicators of fish health (Hamada et al., 2025). In the present study, the inclusion of BSL in the rearing water improved the hematological profile of Sparus aurata. Treated groups showed significant increases in hemoglobin (HB), mean corpuscular hemoglobin (MCH), mean corpuscular hemoglobin concentration (MCHC), and packed cell volume (PCV), reflecting enhanced blood oxygen-carrying capacity (Yaqub et al., 2021). Moreover, water supplementation with B. subtilis led to notable improvements in serum levels of albumin, total protein, and globulin (Ghiasi et al., 2018; Hassaan et al., 2018).

Changes in blood serum composition—particularly under probiotic treatment—are indicative of physiological status and organ function, notably the kidneys, liver, and circulatory system. Hepatic enzymes such as AST and ALT are regularly used as biomarkers for liver health. In this trial, groups receiving B. licheniformis and B. subtilis exhibited substantially reduced liver enzyme levels, suggesting improved hepatic condition. These results are consistent with previous findings in Nile tilapia (Redhwan et al., 2024).

Additionally, probiotic supplementation led to significant reductions in serum urea, creatinine, and uric acid levels, implying better renal function. This contrasts with the study by (Zhao et al., 2022), which reported no significant changes in these parameters among probiotic-treated groups. The graded inclusion of B. subtilis and B. licheniformis also enhanced antioxidant enzyme activities, (SOD and CAT), in agreement with results by (Eissa et al., 2023).

There is a well-established link between diet composition and the activity of digestive enzymes in aquatic species. In this study, the application of Bacillus strains in water significantly elevated digestive enzyme activity compared to the control. Notably, B. licheniformis was found to enhance nutrient digestion by stimulating enzymes such as amylase and cellulase. Similarly the probiotic Bacillus strains increased digestive enzyme activities in Litopenaeus vannamei, with elevated amylase and lipase levels likely contributing to improved growth performance (Monier et al., 2023). These findings suggest that B. licheniformis enhances nutrient absorption and utilization (Yaqub et al., 2021).

Histological examination in this study further confirmed the effective impacts of B. subtilis and B. licheniformis on intestinal tissue architecture in S. aurata. These outcomes are consistent with prior research showing that probiotics and prebiotics can improve the microscopic structure of digestive organs in fish (Ngamkala et al., 2020; Ruiz et al., 2020).

Tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNFα) was initially identified in fish as a single gene expressed in activated leukocytes of the Japanese flounder. It is now recognized as a crucial cytokine involved in antibacterial defense and inflammatory responses (Abd El-Aziz et al., 2024). In fish, the GH and IGF-I genes play vital roles in regulating growth and cellular functions through various signaling pathways (Wang et al., 2020). The GHR facilitates the activity of GH by binding peptide hormones and mediating signaling through the JAK-STAT pathway, thereby regulating growth (de Vos et al., 1992; Dehkhoda et al., 2018). Interleukin-1 beta (IL-1β) functions to attract leukocytes in fish and controls their migration via activation of G protein-coupled receptors and chemokine gradients.

In this study, both pro-inflammatory cytokines (TNF-α and IL-1β) and the anti-inflammatory cytokine IL-10 were selected to assess their involvement in cytokine signaling pathways under stimulation. The administration of B. subtilis and B. licheniformis across different treatments led to upregulation of IL-1β, TNF-α, IL-10, IGF-1, and GH, indicating a shift in the immune response toward enhanced protection. Furthermore, the expression levels of IGF-1 and GH genes were significantly higher in fish cultured in water treated with B. subtilis and B. licheniformis compared to the control group, aligning with improvements observed in growth performance and serum biochemical parameters.

These results corroborate previous studies by (El-Kady et al., 2022; Abd El-Aziz et al., 2024), who reported that probiotic supplementation notably increased IGF-1 and GH gene expression in Nile tilapia. Similarly, probiotics added to the rearing water of Yellow Perch significantly elevated the expression of GH and IGF-I genes relative to controls (Wang et al., 2020). Additionally, probiotic treatment in Yellow Perch enhanced the expression of IL-1β and IL-10 genes compared to untreated groups (Dighiesh et al., 2024).

Research on fish immunology has primarily concentrated on developing preventive strategies to enhance disease resistance and improve fish survival following pathogen exposure (Magnadottir, 2010). In this study, all fish fed diets supplemented with the probiotic B. subtilis (BS) demonstrated significantly enhanced protection against V. parahaemolyticus infection compared to the control group, with the BSL3 dosage offering the greatest level of protection. This marked improvement in tilapia’s resistance supports the idea that Bacillus spp. probiotics can effectively stimulate and prolong the immune response against pathogenic challenges. Many previous natural compounds have been used for optimizing the overall health and well-being in animals (Saleh et al., 2015; Bakeer, 2021; Bakeer et al., 2022) and aquatic fish (Magnadottir, 2010; Darafsh et al., 2020). Comparable increases in disease resistance have been reported in Nile tilapia fed Bacillus spp. mixtures (Abarike et al., 2018; Redhwan et al., 2024), as well as in Persian sturgeon (Darafsh et al., 2020), and in whiteleg shrimp and red tilapia reared in water treated with Bacillus spp. blends (Monier et al., 2023; Eissa et al., 2024a). The overall enhancement in biochemical and immunological parameters across probiotic-treated groups is visually summarized in Figure 5, highlighting the dose-dependent health benefits, particularly in the BSL3 group.

Conclusion

This study demonstrates that supplementing Sparus aurata rearing water with a probiotic blend of Bacillus subtilis and B. licheniformis, particularly at a concentration of 0.03 g/m³, significantly improves water quality, growth performance, feed efficiency, and survival rates. The probiotics enhance fish physiological health by optimizing body composition, hematological and biochemical parameters, and antioxidant defenses, while boosting immune responses and digestive enzyme activities. Improved intestinal morphology and upregulated expression of growth and immune-related genes further support these benefits. Importantly, probiotic-treated fish show greater resistance to V. parahaemolyticus infection. Overall, this probiotic mixture offers a promising, eco-friendly approach to enhancing the health, welfare, and productivity of sea bream in aquaculture systems.

Statements

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Ethics statement

All animal care and experimental procedures were approved by the Zagazig University, Egypt (Approval No. ZU-IACUC/1/F/84/2025). Moreover, all experimental procedures and animal handling were followed according to both institutional guidelines and the ARRIVE guidelines for the ethical treatment of animals.

Author contributions

SN: Writing – review & editing, Visualization, Validation. OA: Validation, Writing – review & editing, Visualization. RE: Validation, Writing – review & editing, Visualization. FM: Visualization, Writing – review & editing, Validation. EE: Investigation, Visualization, Writing – review & editing, Validation. RO: Visualization, Validation, Writing – review & editing. ME: Resources, Validation, Formal analysis, Writing – review & editing, Visualization, Methodology, Writing – original draft, Data curation, Investigation, Conceptualization, Software. EE: Writing – original draft, Formal analysis, Resources, Visualization, Project administration, Supervision, Methodology, Writing – review & editing, Conceptualization, Data curation, Software, Validation, Investigation. NA: Writing – review & editing, Validation, Visualization, Investigation.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank their universities.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1

Abarike E. D. Cai J. Lu Y. Yu H. Chen L. Jian J. et al . (2018). Effects of a commercial probiotic BS containing Bacillus subtilis and Bacillus licheniformis on growth, immune response and disease resistance in Nile tilapia, Oreochromis niloticus. Fish. Shellfish. Immunol. 82, 229–238. doi: 10.1016/j.fsi.2018.08.037

2

Abd El-Aziz Y. M. Jaber F. A. Nass N. M. Awlya O. F. Abusudah W. F. Qadhi A. H. et al . (2024). Strengthening growth, digestion, body composition, haemato-biochemical indices, gene expression, and resistance to Fusarium oxysporum infection and histological structure in Oreochromis niloticus by using fructooligosaccharides and β-1,3 glucan mixture. Aquacult. Int. 32, 7487–7508. doi: 10.1007/s10499-024-01526-z

3

Abuljadayel D. A. Bukhari D. A. A. Eissa M. E. H. Munir M. B. Chowdhury A. J. K. Eissa E.-S. H. (2023). Utilization of probiotic bacteria Pediococcus acidilactici to enhance water quality, growth performance, body composition, hematological indices, biochemical parameters, histopathology and resistance of red tilapia (Oreochromis sp.) against Aeromonas sobria. Desalina. Water Treat. 315, 469–478. doi: 10.5004/dwt.2023.30013

4

AOAC (2000). “ Official methods of analysis,” in Association of Offcial Analytical Chemists., 17th ed ( Washington, DC, USA, Arlington, TX, USA).

5

APHA. American Public Health Association (1998). Standard methods for the examination of water and wastewater.. 20th Ed (New York: American Public Health Association).

6

Azarin H. Aramli M. S. Imanpour M. R. Rajabpour M. (2015). Effect of a Probiotic Containing Bacillus licheniformis and Bacillus subtilis and Ferroin Solution on Growth Performance, Body Composition and Haematological Parameters in Kutum (Rutilus frisii kutum) Fry. Probiot. Antimicrob. Proteins. 7, 31–37. doi: 10.1007/s12602-014-9180-4

7

Bakeer M. R. (2021). Focus on the effect of dietary pumpkin (Cucurbita moschata) seed oil supplementation on productive performance of growing rabbits. J. Appl. Vet. Sci. 6, 22–26. doi: 10.21608/javs.2021.154577

8

Bakeer M. Abdelrahman H. Khalil K. (2022). Effects of pomegranate peel and olive pomace supplementation on reproduction and oxidative status of rabbit doe. J. Anim. Physiol. Anim. Nutr. 106, 655–663. doi: 10.1111/jpn.13617

9

Balcázar J. L. Rojas-Luna T. Cunningham D. P. (2007). Effect of the addition of four potential probiotic strains on the survival of pacific white shrimp (Litopenaeus vannamei) following immersion challenge with Vibrio parahaemolyticus. J. Invertebr. Pathol. 96, 147–150. doi: 10.1016/j.jip.2007.04.008

10

Banerjee G. Ray A. K. (2017). The advancement of probiotics research and its application in fish farming industries. Res. Vet. Sci. 115, 66–77. doi: 10.1016/j.rvsc.2017.01.016

11

Boyd C. E. Tucker C. S. (1998). Pond Aquaculture Water Quality Management. ( Springer US). doi: 10.1007/978-1-4615-5407-3

12

Buege J. A. Aust S. D. (1978). “ [30] Microsomal lipid peroxidation,” in Methods in Enzymology. ( Elsevier). doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(78)52032-6pp302-310

13

Cao H. Chen D. Guo L. Jv R. Xin Y. Mo W. et al . (2022). Effects of Bacillus subtilis on growth performance and intestinal flora of Penaeus vannamei. Aquacult. Rep. 23, 101070. doi: 10.1016/j.aqrep.2022.101070

14

Chauhan A. Singh R. (2019). Probiotics in aquaculture: a promising emerging alternative approach. Symbiosis. 77, 99–113. doi: 10.1007/s13199-018-0580-1

15

Chen M. Chen X.-Q. Tian L.-X. Liu Y.-J. Niu J. (2020). Beneficial impacts on growth, intestinal health, immune responses and ammonia resistance of pacific white shrimp (Litopenaeus vannamei) fed dietary synbiotic (mannan oligosaccharide and Bacillus licheniformis). Aquacult. Rep. 17, 100408. doi: 10.1016/j.aqrep.2020.100408

16

Cho C. Kaushik S. (1990). Nutritional energetics in fish: energy and protein utilization in rainbow trout (Salmo gairdneri). Aspects. Food Prod. Consumpt Energy Values. 61, 132–172.

17

Costa R. A. Araújo R. L. Souza O. V. dos Fernandes Vieira R. H. S. (2015). Research Article Antibiotic-Resistant Vibrios in Farmed Shrimp. Biomed Res. Int. 505914.

18

Darafsh F. Soltani M. Abdolhay H. A. Shamsaei Mehrejan M. (2020). Improvement of growth performance, digestive enzymes and body composition of Persian sturgeon (Acipenser persicus) following feeding on probiotics: Bacillus licheniformis, Bacillus subtilis and Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Aquacult. Res. 51, 957–964. doi: 10.1111/are.14440

19

Dehkhoda F. Lee C. M. M. Medina J. Brooks A. J. (2018). The growth hormone receptor: mechanism of receptor activation, cell signaling, and physiological aspects. Front. Endocrinol. (Lausanne). 9. doi: 10.3389/fendo.2018.00035

20

de Vos A. M. Ultsch M. Kossiakoff A. A. (1992). Human growth hormone and extracellular domain of its receptor: crystal structure of the complex. Science. 255, 306–312. doi: 10.1126/science.1549776

21

Dighiesh H. S. Alharbi N. A. Awlya O. F. Alhassani W. E. Hassoubah S. A. Albaqami N. M. et al . (2024). Dietary multi-strains Bacillus spp. enhanced growth performance, blood metabolites, digestive tissues histology, gene expression of Oreochromis niloticus, and resistance to Aspergillus flavus infection. Aquacult. Int. 32, 7065–7086. doi: 10.1007/s10499-024-01502-7

22

Eissa E.-S. H. Dowidar H. A. Al-Hoshani N. Baazaoui N. Alshammari N. M. Bahshwan S. M. A. et al . (2025a). Dietary supplementation with fermented prebiotics and probiotics can increase growth, immunity, and histological alterations in Pacific whiteleg shrimp (Litopenaeus vannamei) challenged with Vibrio parahaemolyticus. Aquacult. Int. 33, 62. doi: 10.1007/s10499-024-01704-z

23

Eissa E.-S. H. El-Sayed A.-F. M. Ghanem S. F. Dighiesh H. S. Abd Elnabi H. E. Hendam B. M. et al . (2023). Dietary mannan-oligosaccharides enhance hematological and biochemical parameters, reproductive physiology, and gene expression of hybrid red tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus x O. mossambicus). Aquaculture. 581, 740453. doi: 10.1016/j.aquaculture.2023.740453

24

Eissa E.-S. H. El-Sayed A.-F. M. Hendam B. M. Ghanem S. F. Abd Elnabi H. E. Abd El-Aziz Y. M. et al . (2024a). The regulatory effects of water probiotic supplementation on the blood physiology, reproductive performance, and its related genes in Red Tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus X O. mossambicus). BMC Vet. Res. 20, 351–351. doi: 10.1186/s12917-024-04190-w

25

Eissa E. S. H. Okon E. M. Abdel-Warith A. W. A. Younis E. M. Dowidar H. A. Elbahnaswy S. et al . (2024b). In-water Bacillus species probiotic improved water quality, growth, hemato-biochemical profile, immune regulatory genes and resistance of Nile tilapia to Aspergillus flavus infection. Aquacult. Int. 32, 7087–7102. doi: 10.1007/s10499-024-01503-6

26

Eissa E.-S. H. Salama W. M. Elbahnaswy S. El-Son M. A. M. Eldin Z. E. Amer S. et al . (2025b). Pumpkin seed oil-loaded chitosan nanoparticles enhance growth, digestive enzymes, and immune response in whiteleg shrimp (Litopenaeus vannamei): Impacts on histopathology and survival against Vibrio parahaemolyticus. Aquacult. Rep. 40, 102599. doi: 10.1016/j.aqrep.2024.102599

27

El-Kady A. A. Magouz F. I. Mahmoud S. A. Abdel-Rahim M. M. (2022). The effects of some commercial probiotics as water additive on water quality, fish performance, blood biochemical parameters, expression of growth and immune-related genes, and histology of Nile tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus). Aquaculture. 546, 737249. doi: 10.1016/j.aquaculture.2021.737249

28

Ellis A. E. (1990). Lysozyme assays. Techn. Fish. Immunol. 1, 101–103.

29

Galaktionova L. Molchanov A. El’chaninova S. A. BIa V. (1998). Lipid peroxidation in patients with gastric and duodenal peptic ulcers. Klinicheskaia. Laboratornaia. Diagn. 6, 10–14.

30

García-Meilán I. Herrera-Muñoz J. I. Ordóñez-Grande B. Fontanillas R. Gallardo Á. (2023). Growth Performance, digestive enzyme activities, and oxidative stress markers in the proximal intestine of european sea bass (Dicentrarchus labrax) fed high starch or lipid diets. Fishes. 8, 223. doi: 10.3390/fishes8050223

31

Ghiasi M. Binaii M. Naghavi A. Rostami H. K. Nori H. Amerizadeh A. (2018). Inclusion of Pediococcus acidilactici as probiotic candidate in diets for beluga (Huso huso) modifies biochemical parameters and improves immune functions. Fish. Physiol. Biochem. 44, 1099–1107. doi: 10.1007/s10695-018-0497-x

32

Hamada A. Attia M. Marzouk M. Korany R. Elgendy M. Abdelsalam M. (2025). Co-infection with caligus clemensi and vibrio parahaemolyticus in Egyptian farmed mullets: diagnosis, histopathology, and therapeutic management. Egyptian. J. Vet. Sci. 56, 353–368. doi: 10.21608/ejvs.2024.272080.1871

33

Hassaan M. S. Soltan M. A. Jarmołowicz S. Abdo H. S. (2018). Combined effects of dietary Malic acid andBacillus subtilison growth, gut microbiota and blood parameters of Nile tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus). Aquacult. Nutr. 24, 83–93. doi: 10.1111/anu.12536

34

Hendam B. M. Munir M. B. Eissa M. E. H. El-Haroun E. Doan H.v. Chung T. H. et al . (2023). Effects of water additive probiotic, Pediococcus acidilactici on growth performance, feed utilization, hematology, gene expression and disease resistance against Aspergillus flavus of Nile tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus). Anim. Feed. Sci. Technol. 303, 115696. doi: 10.1016/j.anifeedsci.2023.115696

35

Hoseinifar S. H. Van Doan H. Dadar M. Ringø E. Harikrishnan R. (2019). “ Feed additives, gut microbiota, and health in finfish aquaculture,” in Microbial Communities in Aquaculture Ecosystems. ( Springer International Publishing). doi: 10.1007/978-3-030-16190-3_6pp121-142

36

Kawahara E. Ueda T. Nomura S. (1991). In Vitro Phagocytic Activity of White-Spotted Char Blood Cells after Injection with Aeromonas salmonicida Extracellular Products. Fish. Pathol. 26, 213–214. doi: 10.3147/jsfp.26.213

37

Khademzade O. Zakeri M. Haghi M. Mousavi S. M. (2020). The effects of water additive Bacillus cereus and Pediococcus acidilactici on water quality, growth performances, economic benefits, immunohematology and bacterial flora of whiteleg shrimp (Penaeus vannamei Boone, 1931) reared in earthen ponds. Aquacult. Res. 51, 1759–1770. doi: 10.1111/are.14525

38

Koroliuk M. Ivanova L. Maĭorova I. Tokarev V. A. (1988). A method of determining catalase activity. Laboratornoe delo. 1, 16–19.

39

Li K. Liu L. Zhan J. Scippo M.-L. Hvidtfeldt K. Liu Y. et al . (2017). Sources and fate of antimicrobials in integrated fish-pig and non-integrated tilapia farms. Sci. Total. Environ. 595, 393–399. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2017.01.124

40

Magnadottir B. (2010). Immunological control of fish diseases. Mar. Biotechnol. 12, 361–379. doi: 10.1007/s10126-010-9279-x

41

Mathew R. T. Alkhamis Y. A. Saud Alsaqufi A. Mansour A. T. Aldakhillalla O. N. El Sayed M. S. et al . (2025). Effects of quadric probiotic blend supplementation on growth, biochemical markers, organ histology, immunity, antioxidant status, and gene expression in Nile tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus). Aquacult. Int. 33, 649. doi: 10.1007/s10499-025-02313-0

42

Millard R. S. Ellis R. P. Bateman K. S. Bickley L. K. Tyler C. R. van Aerle R. et al . (2021). How do abiotic environmental conditions influence shrimp susceptibility to disease? A critical analysis focussed on White Spot Disease. J. Invertebr. Pathol. 186, 107369. doi: 10.1016/j.jip.2020.107369

43

Mohammady E. Y. Soaudy M. R. Abdel-Rahman A. Abdel-Tawwab M. Hassaan M. S. (2021). Comparative effects of dietary zinc forms on performance, immunity, and oxidative stress-related gene expression in Nile tilapia, Oreochromis niloticus. Aquaculture. 532, 736006. doi: 10.1016/j.aquaculture.2020.736006

44

Monier M. N. Kabary H. Elfeky A. Saadony S. El-Hamed N. N. B. A. Eissa M. E. H. et al . (2023). The effects of Bacillus species probiotics (Bacillus subtilis and B. licheniformis) on the water quality, immune responses, and resistance of whiteleg shrimp (Litopenaeus vannamei) against Fusarium solani infection. Aquacult. Int. 31, 3437–3455. doi: 10.1007/s10499-023-01136-1

45

Ngamkala S. Satchasataporn K. Setthawongsin C. Raksajit W. (2020). Histopathological study and intestinal mucous cell responses against Aeromonas hydrophila in Nile tilapia administered with Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG. Vet. World. 13, 967–974. doi: 10.14202/vetworld.2020.967-974

46

Nishikimi M. Appaji Rao N. Yagi K. (1972). The occurrence of superoxide anion in the reaction of reduced phenazine methosulfate and molecular oxygen. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 46, 849–854. doi: 10.1016/s0006-291x(72)80218-3

47

Qiu Z. Xu Q. Li S. Zheng D. Zhang R. Zhao J. et al . (2023). Effects of probiotics on the water quality, growth performance, immunity, digestion, and intestinal flora of giant freshwater prawn (Macrobrachium rosenbergii) in the biofloc culture system. Water. 15, 1211. doi: 10.3390/w15061211

48

Redhwan A. Eissa E.-S. H. Ezzo O. H. Abdelgeliel A. S. Munir M. B. Chowdhury A. J. K. et al . (2024). Effects of water additive mixed probiotics on water quality, growth performance, feed utilization, biochemical analyses and disease resistance against Aeromonas sobria of Nile tilapia. Desalina. Water Treat. 319, 100480. doi: 10.1016/j.dwt.2024.100480

49

Ruiz M. L. Owatari M. S. Yamashita M. M. Ferrarezi J. V. S. Garcia P. Cardoso L. et al . (2020). Histological effects on the kidney, spleen, and liver of Nile tilapia Oreochromis niloticus fed different concentrations of probiotic Lactobacillus plantarum. Trop. Anim. Health Prod. 52, 167–176. doi: 10.1007/s11250-019-02001-1

50

Saleh S. Y. Sawiress F. A. Tony M. A. Hassanin A. M. Khattab M. A. Bakeer M. R. (2015). Protective role of some feed additives against dizocelpine induced oxidative stress in testes of rabbit bucks. J. Agric. Sci. 7, 239–252. doi: 10.5539/jas.v7n10p239

51

Soltani M. Ghosh K. Hoseinifar S. H. Kumar V. Lymbery A. J. Roy S. et al . (2019). Genus Bacillus, promising probiotics in aquaculture: Aquatic animal origin, bio-active components, bioremediation and efficacy in fish and shellfish. Rev. Fisheries. Sci. Aquacult. 27, 331–379. doi: 10.1080/23308249.2019.1597010

52

Suvarna K. S. Layton C. Bancroft J. D. (2018). Bancroft’s theory and practice of histological techniques E-Book. ( Elsevier health sciences).

53

Torrecillas S. Aboelsaadat E. Carvalho M. Acosta F. Monzón-Atienza L. Gordillo Á. et al . (2024). Dietary supplementation of a combination of formic acid and sodium formate in practical diets promotes gilthead sea bream (Sparus aurata) gut morphology and disease resistance. Aquacult. Rep. 35, 101951. doi: 10.1016/j.aqrep.2024.101951

54

Tzortzatos O.-P. Toubanaki D. K. Kolygas M. N. Kotzamanis Y. Roussos E. Bakopoulos V. et al . (2024). Dietary Artemisia arborescens Supplementation Effects on Growth, Oxidative Status, and Immunity of Gilthead Seabream (Sparus aurata L.). Anim. (Basel). 14, 1161. doi: 10.3390/ani14081161

55

Wang R. Guo Z. Tang Y. Kuang J. Duan Y. Lin H. et al . (2020). Effects on development and microbial community of shrimp Litopenaeus vannamei larvae with probiotics treatment. AMB. Express. 10, 109–109. doi: 10.1186/s13568-020-01041-3

56

Wuertz S. Schroeder A. Wanka K. M. (2021). Probiotics in fish nutrition—Long-standing household remedy or native nutraceuticals? Water. 13, 1348. doi: 10.3390/w13101348

57

Yaqub A. Awan M. N. Kamran M. Majeed I. (2021). Evaluation of potential applications of dietary probiotic (Bacillus licheniformis SB3086): Effect on growth, digestive enzyme activity, hematological, biochemical, and immune response of Tilapia (Oreochromis mossambicus). Turkish. J. Fisheries. Aquat. Sci. 22. doi: 10.4194/trjfas19882

58

Yu Y. Zhang Y. Wang Y. Liao M. Li B. Rong X. et al . (2023). The Genetic and Phenotypic Diversity of Bacillus spp. from the Mariculture System in China and Their Potential Function against Pathogenic Vibrio. Mar. Drugs. 21, 228. doi: 10.3390/md21040228

59

Zhang Q.-H. Feng Y.-H. Wang J. Guo J. Zhang Y.-H. Gao J.-Z. et al . (2011). Study on the characteristics of the ammonia-nitrogen and residual feeds degradation in aquatic water by Bacillus. Acta Hydrobiol. Sin. 35, 497–503. doi: 10.3724/sp.j.1035.2011.00498

60

Zhao S. Feng P. Hu X. Cao W. Liu P. Han H. et al . (2022). Probiotic Limosilactobacillus fermentum GR-3 ameliorates human hyperuricemia via degrading and promoting excretion of uric acid. iScience. 25, 105198–105198. doi: 10.1016/j.isci.2022.105198

Summary

Keywords

Bacillus spp., water quality, growth, health, gene expression, Vibrio parahaemolyticus

Citation

Nassar SE, Abd Al-Kareem OM, El Araby RES, Mahsoub F, El-Haroun E, Osailan R, Eissa MEH, Eissa E-SH and Ahmed NH (2025) Effects of probiotic Bacillus subtilis and B. licheniformis on water quality, growth, physiology, gene expression, and disease resistance in Sparus aurata fingerlings. Front. Mar. Sci. 12:1737048. doi: 10.3389/fmars.2025.1737048

Received

31 October 2025

Revised

22 November 2025

Accepted

25 November 2025

Published

15 December 2025

Volume

12 - 2025

Edited by

Ming Li, Ningbo University, China

Reviewed by

Neeraj Kumar, National Institute of Abiotic Stress Management (ICAR), India

Sofia Priyadarsani Das, National Taiwan Ocean University, Taiwan

Updates

Copyright

© 2025 Nassar, Abd Al-Kareem, El Araby, Mahsoub, El-Haroun, Osailan, Eissa, Eissa and Ahmed.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Moaheda E.H. Eissa, moahedaelsayed@gmail.com; Ehab El-Haroun, ehab.reda@uaeu.ac.ae

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.