Abstract

The epiretinal membrane (ERM) is a pathological tissue formed at the vitreoretinal interface. The formation of this tissue is associated with numerous symptoms related to disturbances of vision. These types of lesions may arise idiopathically or be secondary to eye diseases, injuries and retinal surgeries. ERM tissue contains numerous cell types and numerous cytokines, which participate in its formation. The aim of this paper is to summarize information about the etiology, epidemiology, pathophysiology and treatment of ERM, with a brief description of the main cells that build the ERM – as well as the cytokines and molecules related to ERM pathogenesis – being provided in addition.

1. Introduction

The epiretinal membrane (ERM), commonly known as macular pucker or cellophane maculopathy, is a pathological tissue formed at the junction of the vitreous body and the retina – the vitreoretinal interface. The formation of this tissue is associated with symptoms related to visual disturbances. The lesions of this type may arise idiopathically or be secondary to eye diseases, injuries and retinal surgery. In the case of idiopathic changes, a number of factors may favor the development of these lesions (1).

ERM tissue contains many cell types deriving from different parts of eyeball: retinal pigment epithelium (RPE) cells, fibrocytes, fibrous astrocytes, myofibroblast-like cells, glial cells, endothelial cells (ECs), and macrophages. The cellular composition of this tissue varies individually and depends on the cause of the lesions and the participation of numerous cytokines such as growth factors, tumor necrosis factor (TGF) or chemokines (2).

The aim of this paper is to summarize information on the etiology, epidemiology, pathophysiology, and treatment of ERM.

2. Pathophysiology of ERM

The vitreous body, consisting of a colorless, highly hydrated gel matrix, fills the space called the vitreous chamber located posteriorly to the ciliary body. The vitreous body adheres loosely to the retina, connecting most strongly around the ora serrata and the optic nerve (3). Its outer layer – vitreous cortex – is made of collagen, while the inside is filled with vitreous humor containing mainly water (98–99%), fibrous protein called vitrosin, type II collagen fibers, glycosaminoglycans, hyaluronates, opticins and other proteins (4).

The vitreous body contains a small number of cells, mainly phagocytes, that remove cellular debris and hyalocytes the main function of which is to produce hyaluronans (5). Vitreous body is involved in maintaining proper intraocular pressure, protecting the lens against oxidative stress and is one of the optical centers (3, 6).

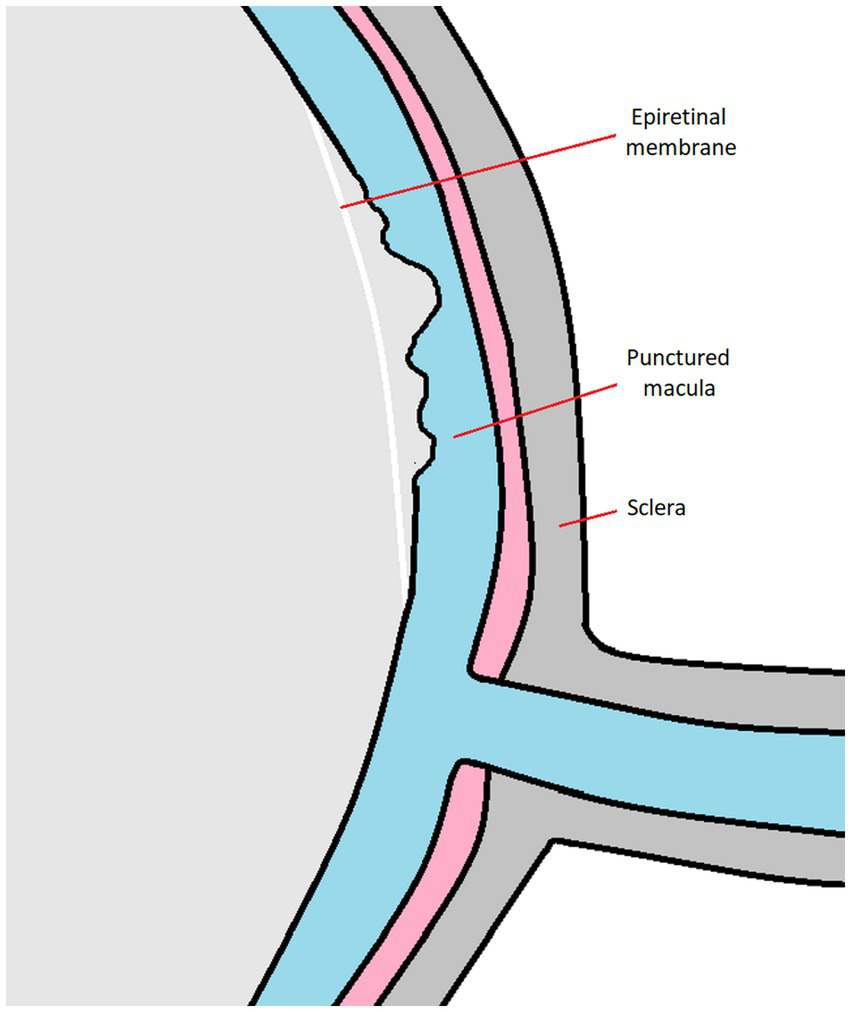

With age, an increase in liquefaction and fiber aggregation occurs, one which may lead to many ophtalmic diseases (7, 8). As a result of these processes, the volume of the vitreous body decreases, the said body collapses, and the collagen fibers reorganize. This leads to changes in the shape of the vitreous body and posterior vitreous detachment (PVD). If this process is not complete, and macula and vitreous body come into contact, a posterior vitreomacular adhesion (VMA) is formed at the point of this contact. This process may lead to the formation of vitreomacular traction (VMT), which involves foveal contour distortion and retinal layer disorders, with a possible elevation of the retina above the pigment epithelium (RPE), not interrupting, however, the retina’s continuity. In this state most patients self-heal due to completion of PVD. When VMT is not self-healed and a hole in the macula occurs, the next step in the evolution of the pathology could be vitreoschisis, which occurs in the case of the half of PVD patients. During this process posterior vitreous cortex splits, leaving the outermost layer attached to the macula, while the remainder of the vitreous collapses forward. This can lead to the proliferation within the retinal vitreous residue, i.e., the formation of an epiretinal membrane (ERM) (9, 10) (Figure 1).

Figure 1

This illustration presents ERM tissue in relation to other eyeball parts.

Formed ERM tissue can cause macular edema or distortion of the vitreoretinal interface, which may lead to visual disturbances, including blurred vision and a reduction of visual acuity (11) (Figure 2).

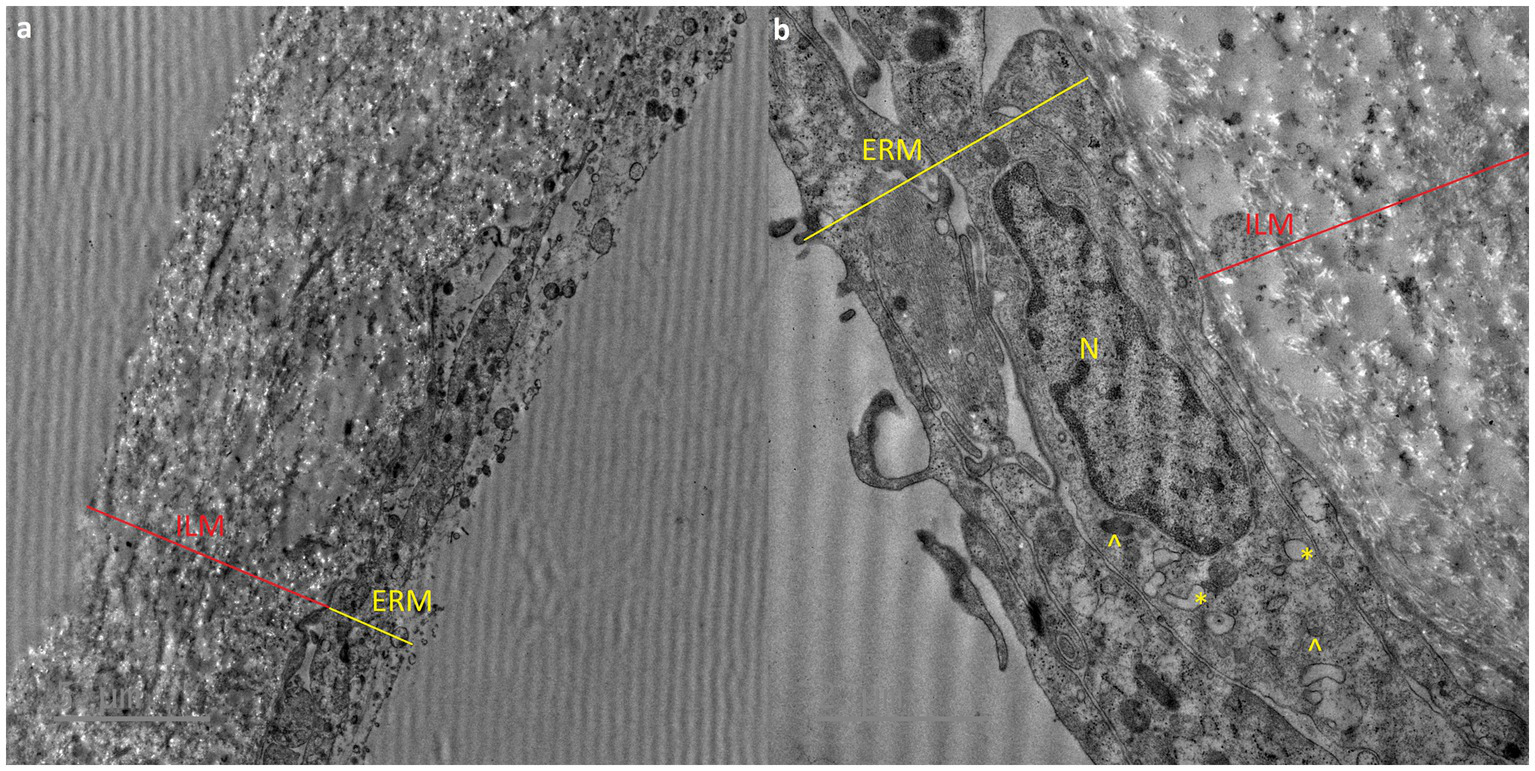

Figure 2

Transmission electron micrograph showing epiretinal membrane (ERM) and internal limiting membrane (ILM). a – original micrograph showing comparison of ERM and ILM structure (original magnification x4200), b – micrograph showing detailed structure of ERM and phagocytes: N – cell nuclei, asterix (*) – vacuoles, arrowhead (^) – dense granules (magnificated and focused micrograph a).

2.1. ERM tissue formation

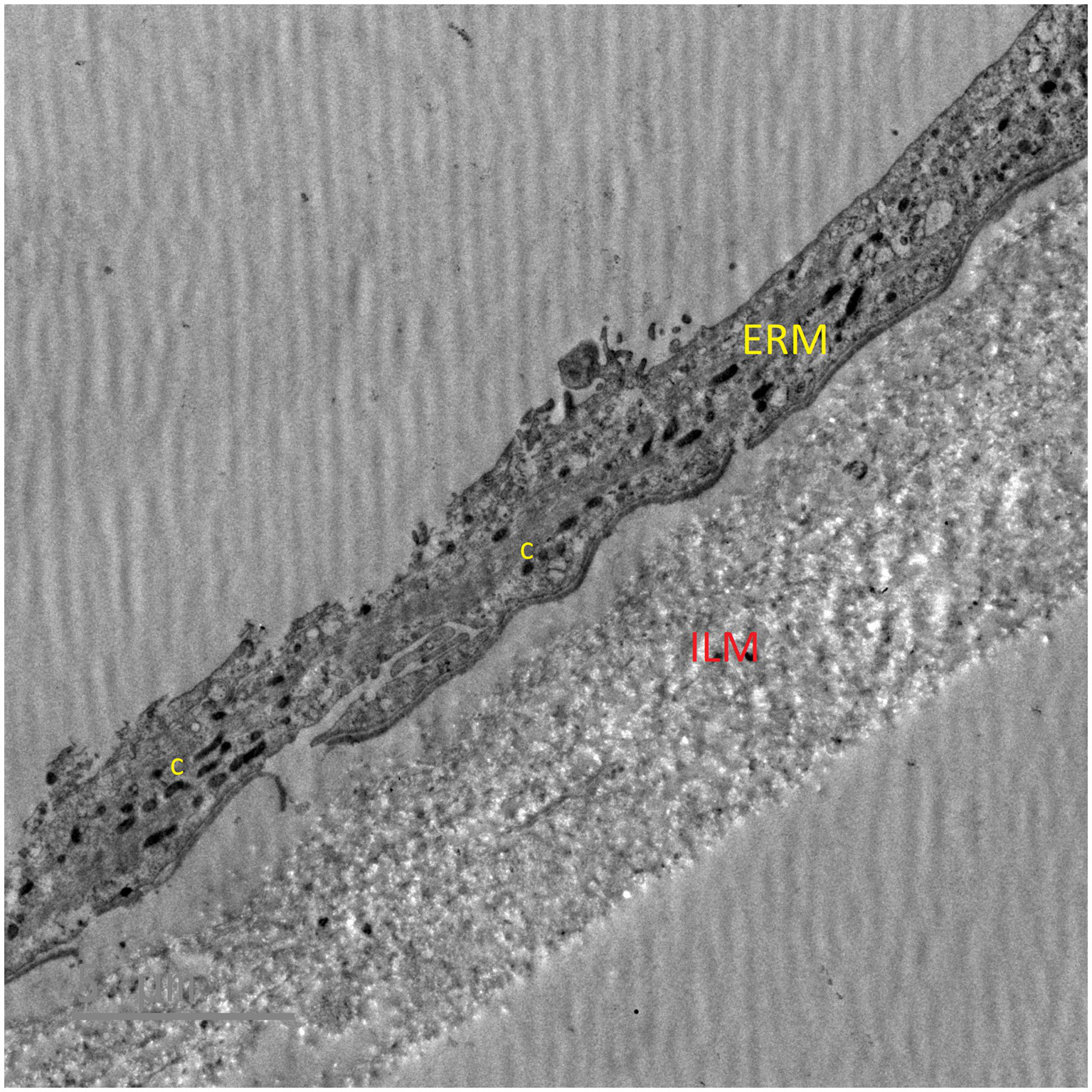

Pathological cell proliferation on the internal limiting membrane (ILM) surface is the basis for the formation of pathological tissue at the interface between the vitreous body and the retina. As a result of PVD, ILM dehiscence occurs, which leads to the migration of microglial cells to the surface. Microglial cells then interact with the neighboring hyalocytes and laminocytes of the vitreous cellular membrane (12). These cells then differentiate into fibroblast-like cells, which are directly responsible for the formation of the collagen scaffolding of the ERM (13, 14) (Figure 3).

Figure 3

Transmission electron micrograph showing collagen fibers in epiretinal membrane. ERM – epiretinal membrane, ILM – internal limiting membrane, c – collagen fibers.

ERMs can arise idiopathically or secondary to certain disease states, and as a result of a trauma or surgery within the eyeball.

In the case of the idiopathic ERM retinal glial cells, hyalocytes, fibroblasts, and myofibroblasts generated by cell migration and differentiation of microglial cells, hyalocytes, and laminocytes predominate (2, 14).

In secondary ERM, the presence of the retinal pigment epithelial cells, macrophages, T cells, and B cells is observed due to inflammation appearing in the etiology of this lesion (15, 16).

The leading theory presents the sequence of changes leading to the emergence of the ERM thus:

-

Microglial cells migrate to the surface of the retina as a consequence of PVD and the resulting formation of the cracks within the ILM.

-

The fragments of the vitreous membrane remaining on the surface of the ILM contain hyalocytes, which, due to contact with microglial cells, differentiate into myofibroblasts, while microglial cells may differentiate into fibroblasts.

-

PVD-induced ILM avulsion enhances the action of some ERM-promoting cytokines (17–19).

2.2. Idiopathic ERM

The idiopathic form of ERM affects approximately 95% of patients and is directly related to cellular proliferation resulting from PVD.

It is possible to distinguish 2 types of iERM. Type I is formed due to collagen of the vitreous body coming into contact with the internal limiting membrane (ILM) of the retina, which results in the production of a collagen membrane separating the two structures. Type II, on the other hand, results from cell proliferation that takes place directly on the ILM surface with or without a small layer of collagen in between (20).

2.3. Secondary ERM

The secondary form of ERM develops in the course of eye diseases or as a result of injuries of the eyeball or the surgeries performed on it.

As a result of these disorders, inflammation within the retina occurs, which leads to an inflammatory infiltration and, ultimately, a migration of cells from other layers of the retina to the ERM being in the process of formation (21) (Table 1).

Table 1

| Type of complication | Disease entities |

|---|---|

| Iatrogenic | Cataract surgery |

| Vitrectomy surgery | |

| Retinopexy (laser or cryotherapy) | |

| Retinal vascular diseases | Diabetic retinopathy |

| Retinal vascular occlusive disease | |

| Coat’s disease | |

| Retinal arteriolar macroaneurysm | |

| Radiation retinopathy | |

| Sickle-cell retinopathy | |

| Intraocular tumors | Retinal haemangioblastoma |

| Vasoproliferative tumor | |

| Choroidal melanoma | |

| Hamartoma of the retina and retinal pigment epithelium combined | |

| Retinal astrocytic hamartoma | |

| Vitreomacular traction disorders | Macular hole |

| Vitreomacular traction syndrome | |

| Other retinal diseases | Retinal tears |

| Retinitis pigmentosa | |

| Other diseases of the eyeball | Uveitis |

| Myopia | |

| Trauma | |

| Age-related macular degeneration | |

| Neurofibromatosis type 2 |

Diseases associated with secondary ERM.

3. Histopatology of ERM

3.1. The cells that build ERM

ERM is usually made up of two layers placed on the ILM. The outer layer directly overlying the ILM consists of randomly oriented proteins, while the inner layer consists of one or more layers of cells from the retina (22). The cells observed are glial cells, hyalocytes, RPE cells, macrophages, fibroblasts, and myofibroblast-like cells. Apart from the latter type, the source of the cells within the ERM is uncertain. It is known, however, that myofibroblast-like cells are formed by differentiating from other cell types within ERM (22, 23) (Table 2).

Table 2

| Type of cells | Description |

|---|---|

| Glial cells | Microglia are small cells of a monocytic / macrophagal origin, placed in retina and optic nerve. Those cells as parts of ERM tissue produce TGF-beta, which is mainly involved in the differentiation of myofibroblast-like cells (24). |

| Within the ERM there is low abundance of astrocytes (which migrate from retina and optical nerve), the presence of which appears more prominent in other vitreomacular traction disorders such as vitreomacular traction syndrome (VMTS), lamellar macular holes (LMHs) and myopic traction maculopathies (24). | |

| The proliferation of Muller cells (a characteristic type of cells in retina) is believed to be one of the direct causes of ERM formation as source of proinflamatory cytokines (25, 26). | |

| Hyalocytes | These are phagocytic cells, also of monocytic/macrophagal origin found on the surface of the vitreous base. Main function of this cells is production of elements of the extracellular matrix. These cells are responsible for the production of TGF-b which is a major contributor to the differentiation of myofibroblast-like cells (27, 28). |

| Retinal pigment epithelium (RPE) cells | These cells, originally forming single layer arranged at the outermost layer of the retina, migrate through retinal breaks and attach themselves to the inner retina. They are likely to transform to myofibroblast-like cells (22). |

| Macrophages | The presence of macrophages within lesion (which could be found by default in cornea, uveal tract and choroid) can be observed mainly in the secondary ERM associated with vitreous haemorrhage. They are the source of many cytokines involved in the pathophysiology of the lesion (29, 30). |

| Fibroblasts and myofibroblast-like-cells | These cells are responsible for the production of proteins forming the ERM intercellular matrix and produce many pro-inflammatory cytokines (22). |

Cells that built epiretinal membranes.

3.2. Cytokines and molecules related to ERM pathogenesis

A number of cytokines and molecules related to this process which directly or indirectly influence the development of this pathology have been identified. These cells are responsible for the production of proteins that constitute the ERM extracellular matrix (31) (Table 3).

Table 3

| Cytokine or molecule | Description |

|---|---|

| Vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) | VEGF is a growth factor that stimulates mitosis and endothelial cell migration and chemotactic factor for leukocytes. One of the main factors stimulating the production of VEGF is tissue hypoxia – in the case of its appearance, any type of cell is able to commence the production of VEGF (23). |

| One of the phenomena observed in the course of PDR is capillary oclusion in the retina, which, by causing hypoxia, increases the expression of VEGF by the cells that build the retina (32). Pathological retinal angiogenesis promotes the formation of subretinal hemorrhages, which in turn promotes the development of ERM (33). | |

| Increased VEGF expression has been observed not only in the retina of ERM patients, but also within the lesion itself. Additionally, the presence of VEGF receptors in ERM-forming cells was demonstrated. This suggests that VEGF acts as a growth factor for ERM-forming cells (34, 35). | |

| Placenta growth factor (PlGF) | PlGF is a homologue of VEGF that shares receptors with it, but displays significantly lower mitogenic properties on endothelial cells. PlGF has been demonstrated to act synergistically with VEGF and its low expression significantly stimulates the action of VEGF (36). |

| Tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-a) | TNF-α is a family of pro-inflammatory cytokines with pleiotropic effects. They participate in the pathogenesis of many diseases such as cancer and autoimmune diseases (37). In the case of the eyeball, TNF-a participates in the neovascularization of the retina after hypoxia (38). |

| Platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF) | PDGF is a cytokine that plays major role in wound healing. Its expression has been confirmed in the cases of many types of cells, such as endothelial cells, macrophages and fibroblasts (39). High expression of this factor has been demonstrated in the case of all retinal proliferative diseases (40). The expression of this factor in the eyeball is probably stimulated by retinal hypoxia. Apart from the proangiogenic effect of PDGF, this cytokine is also a mitogenic and chemotactic factor for RPE and glial cells (41). |

| Transforming growth factors-b (TGF-b) | TGF-b is a family of cytokines that exhibit pleiotropic effects on tissues. These cytokines are involved in the control of the proliferation and migration of endothelial cells (34, 42). Within the ERM, this cytokine is responsible for the differentiation of cells into fibroblast-like cells – responsible mainly for the production of ERM-building proteins (43). |

| Angiopoietins | It is a group of proangiogenic cytokines that are of greatest importance in embryonic angiogenesis. It is of great importance in the maturation and stabilization of blood vessels (44, 45). |

| Interleukin-6 (IL-6) | It is a pleiotropic cytokine that plays an important role in the activation of lymphocytes (46). Increased expression of this cytokine has been observed in the course of retinal injuries and in the case of diabetic patients (47, 48). |

| Vascular cell adhesion molecules | Intracellular adhesion molecule 1 (ICAM-1), vascular cell adhesion molecule 1 (VCAM-1), E-selectin, and P-selectin play an important role in the circulation of leukocytes in areas of inflammation. TNF-α (and other cytokines) increase their expression, which in turn increases the migration of leukocytes to the surrounding tissues (49, 50). |

| Tenascin-C | Tenascin-C is an extracellular glycoprotein that modulates cell growth and adhesion. Its participation is essential in the process of blood vessel sprouting (51, 52). |

| Basic fibroblast growth factor (bFGF) | bFGF is a growth factor and a signaling protein involved in cell growth, morphogenesis and tissue regeneration. It plays an important role in the survival of cells subjected to stress (53). Expression of bFGF and its receptors has been demonstrated within the retina, where they probably influence the course of retinal ischemia (54–56). |

| Hepatocyte growth factor (HGF) | HGF is a kinase that plays an important role in regulating cell growth and morphogenesis. It has been shown to be pro-angiogenic (57). |

| Glial cell line-derived neurotrophic factor (GDNF) | GDNF is a cytokine that promotes the survival of many types of nerve cells. It is usually secreted by astrocytes, oligodendrocytes, Schwann cells and motor neurons (58). It has a chemotactic effect on glial cells (59). |

Cytokines and molecules involved in epiretinal formation.

4. Epidemiology

The main risk factors for ERM are age and PVD. PVD is observed in the case of 70% of patients in the initial stages of the disease. Although PVD can appear early in life or childhood, ERM usually appears after the age of 50, and the risk of its appearance increases exponentially with age.

Gender was not observed to exert any influence as to the risk of the appearance of ERM, although some studies indicate a slight predominance of women among the afflicted (60). Statistically, significant differences in risk of occurrence seem to emerge due to ethnicity – in studies concerning the American society, the highest number of ERM cases is identified in the population of Chinese origin, followed by the ethnic groups of, respectively, Latin American, Caucasian and African descent.

Geographic differences were also observed to play a part: ERM is more common in Europe and South America, and the least common in Asia. This phenomenon is probably related to lifestyle and diet. Other factors contributing to the development of ERM are obesity, type II diabetes, hypertension and hypercholesterolaemia (60, 61).

5. Symptoms and diagnosis

The symptoms reported by patients depend on the stage (phase of development) and type of ERM. In some cases, the presence of ERM does not produce clinical symptoms and is diagnosed accidentally. Patients usually complain of: visual disturbances – metamorphopsia, micropsia or macropsia, photopsia, decreased visual acuity, diplopia, and a loss of central vision. The diagnosis of ERM is based on a clinical examination and Optical Coherence Tomography (OCT). In the case of fundoscopy, a cellophane reflex or wrinkling on the retinal surface resulting from the contracture of the membrane can be observed. It usually affects the foveal and parafoveal area. Cystoid macular oedema (CMO), lamellar or full-thickness macular holes (MHs) and/or small retinal hemorrhages can be seen in association with ERM. The diagnosis of idiopathic ERM is based on the exclusion of other ophthalmic diseases like retinal vascular diseases including diabetic retinopathy, retinal vein occlusion, uveitis and other inflammatory diseases, trauma, intraocular tumors, and retinal tear or detachment (62).

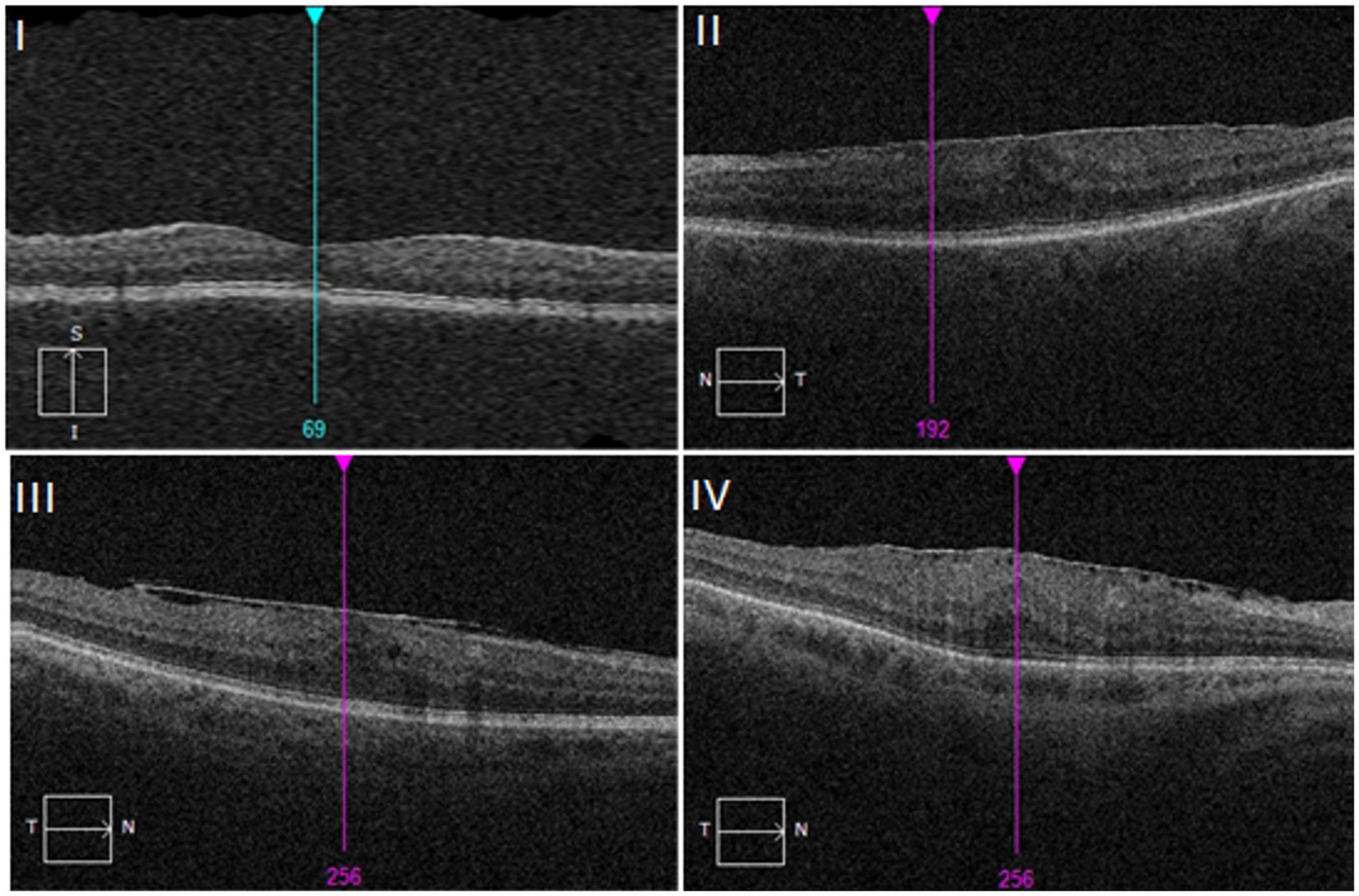

There are several ERM classification systems based on OCT findings. No classification, however, is currently suggested for general use in clinical practice (63) (Figure 4).

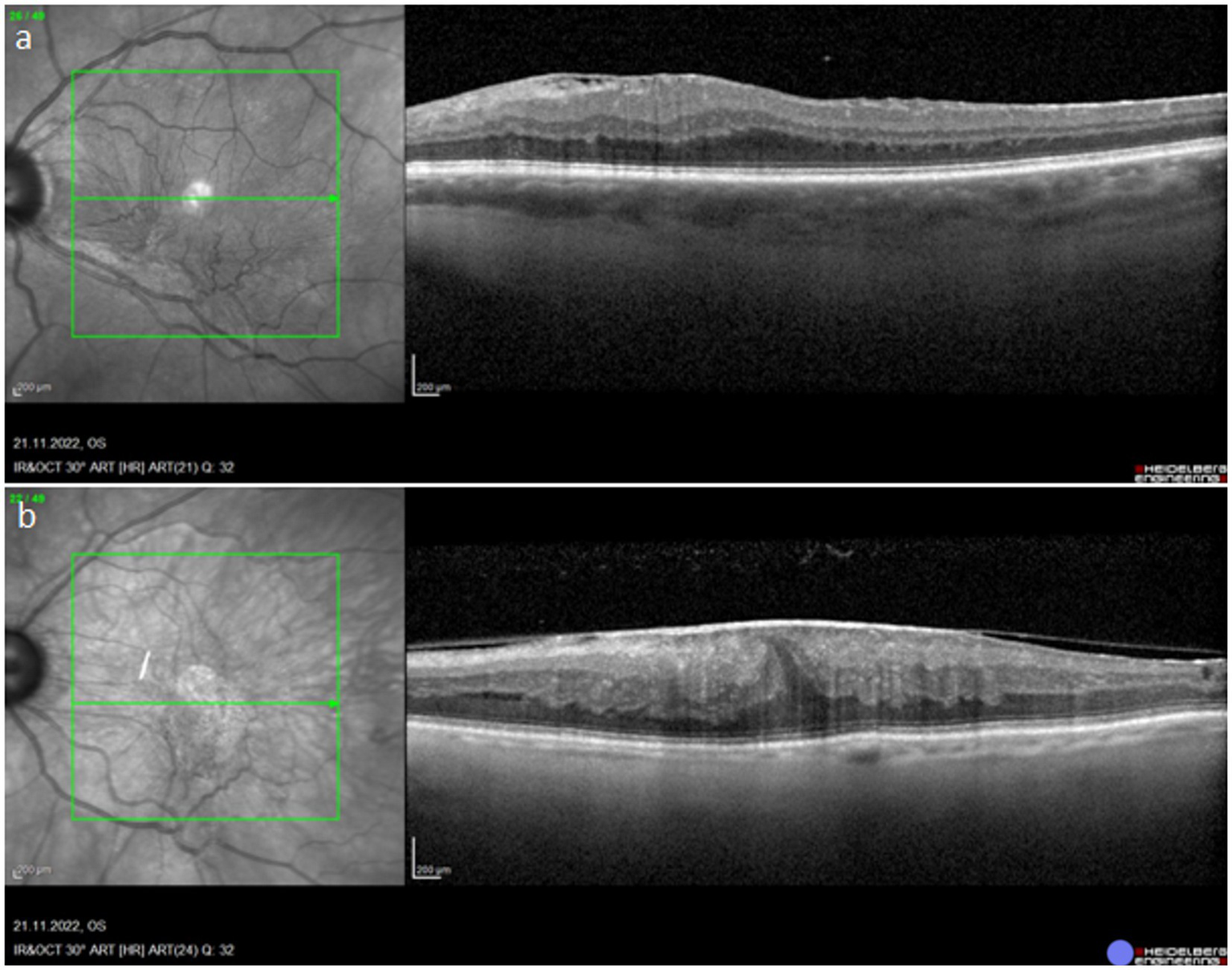

Figure 4

Stages of ERM showed on optical coherence tomography (OCT) images. I – ERMs are mild and thin. Foveal depression is present. II – ERMs with a widening of the outer nuclear layer and loss of the foveal depression. III – ERMs with continuous ectopic inner foveal layers crossing the entire foveal area. IV – ERMs are thick with continuous ectopic inner foveal layers and disrupted retinal layers. Based on clasification by Govetto et al. (64).

From the additional diagnostic tools, one worth mentioning is fluorescein angiography (FA), which is useful in the case of secondary ERM when it comes to identifying preoperatively the underlying cause of like intraocular tumors or retinal vascular diseases. Macular edema can also be confirmed with angiography (62). The OCT examination allows not only to deepen the diagnosis, but also to distinguish different stages of the ERM development (64) (Table 4 and Figure 5).

Table 4

| Stage | Description |

|---|---|

| I | Thin layer of ERM on the retinal surface; foveal depression is present; the layered structure of the retina is preserved |

| II | Presence of ERM accompanied by the loss of the foveal depression; widening of the retinal outer nuclear layer, the layered structure of the retina is preserved |

| III | ERMs with continuous (ectopic inner foveal layers) hyporeflective or hyperreflective band, extending from the inner nuclear layer (INL) and inner plexiform layer (IPL) crossing the entire foveal area; foveal depression is absent; the layered structure of the retina is preserved |

| IV | Thick ERM with continuous ectopic inner foveal layers; foveal depression is absent; distortion of the retinal layers |

Optical coherence tomography staging scheme proposed by Govetto et al. (64).

Figure 5

OCT images showing stage 3 and stage 4 of ERM. a – stage 3, b – stage 4.

6. ERM treatment

The management options for ERM are limited and consist of observation or surgical intervention. Official guidelines for performing the surgical ERM removal have not been established. Before taking appropriate intervention measures, it is advisable to discuss with the patient all the possible benefits and complications related to the surgery in relation to the severity of the patient’s symptoms and their lifestyle (65).

During the surgical intervention called pars plana vitrectomy (PPV), the epiretinal membrane is removed and the retinal tractions are released. ILM is considered to be the scaffold for myofibroblast proliferation, thus it is commonly removed alongside with ERM, in order to minimize the risk of ERM recurrence. Sometimes PPV is combined with a simultaneous cataract surgery involving intraocular lens implantation (phacovitrectomy). During the surgery, special dyes, like triamcinolone acetonide, trypan blue, indocyanine green (ICG), and brilliant blue, are used to distinguish ERM from the retinal layers (66).

It is possible to discern two types of PPV – complete vitrectomy, which involves the whole vitreous body being detached from the retina and removed, and limited vitrectomy, which involves removing only the central part of the vitreous body. Most of the times, the complete vitrectomy is performed, however, there is no difference when it comes to the results of it and the limited vitrectomy. Limited vitrectomy is usually faster and potentially produces fewer long-term side effects (67).

The surgical treatment of ERM provides excellent postoperative visual outcomes and is a relatively safe procedure. Improvement in the vascularity of the choroid was also observed (68). Like any other surgical intervention, ERM surgery can cause complications, such as endophtalmitis, retinal detachment or ERM recurrence (69).

7. Conclusion

It is estimated that the main risk factor that significantly preceding the development of ERM, i.e., PDV, occurs in about 2% of the population. The main epidemiological factor associated with PDV is old age (60, 61, 70). An increased incidence of ERM is therefore to be expected due to the aging of the population. By understanding the successive processes leading to the formation of ERM, we better understand the causes of not only this pathology but also PDV. Currently, it is not possible to predict the development of this pathology based on biochemical tests, while the development of knowledge about the histological structure of ERM and the expression of cytokines and molecules related to ERM pathophysiology may in the future allow for the detection of a biochemical marker allowing for early detection of ERM development without the need for costly OCT, development guidelines for qualifying patients for surgical treatment and a potential conservative treatment regimen. Currently, there is also no prophylaxis for idiopathic ERM development, but by understanding the inflammatory factors involved in this process, it will be possible to develop some. In the case of secondary ERM, in addition to reducing the risk by appropriate treatment of the cause, it is possible, thanks to potential biochemical markers, to include some of these patients in regular observation due to high risk of ERM development.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Statements

Author contributions

MO and MN-W: conceptualization and writing—original draft preparation. WR: writing—review and editing, and supervision. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

1.

Kwok AK Lai TY Yuen KS . Epiretinal membrane surgery with or without internal limiting membrane peeling. Clin Exp Ophthalmol (2005) 33:379–85. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-9071.2005.01015.x

2.

Oberstein SY Byun J Herrera D Chapin EA Fisher SK Lewis GP . Cell proliferation in human epiretinal membranes: characterization of cell types and correlation with disease condition and duration. Mol Vis (2011) 17:1794–805. PMID:

3.

Rękas M. Rejdak M. (2020). Choroby ciała szklistego i powierzchni szklistkowo-siatkówkowej.Siatkówka i ciało szkliste.BCSC12.Seria Basic and clinical science course. Edra Urban & Partner, Wrocław, Poland2020. pp. 371–374

4.

Donati S Caprani SM Airaghi G Vinciguerra R Bartalena L Testa F et al . Vitreous substitutes: the present and the future. Biomed Res Int (2014) 2014:351804. doi: 10.1155/2014/351804

5.

Boneva SK Wolf J Wieghofer P Sebag J Lange AKC . Hyalocyte functions and immunology. Expert Rev Ophthalmol (2022) 17:249–62. doi: 10.1080/17469899.2022.2100763

6.

Ankamah E Sebag J Ng E Nolan JM . Vitreous antioxidants, degeneration, and vitreo-retinopathy: exploring the links. Antioxidants (Basel) (2019, 2019) 9, 9:7. doi: 10.3390/antiox9010007

7.

Los LI van der Worp RJ van Luyn MJA Hooymans JMM . Age-related liquefaction of the human vitreous body: LM and TEM evaluation of the role of proteoglycans and collagen. Invest Opthalmol Vis Sci (2003) 44:2828–33. doi: 10.1167/iovs.02-0588

8.

Tram NK Swindle-Reilly KE . Rheological properties and age-related changes of the human vitreous humor. Front Bioeng Biotechnol (2018) 6:199. doi: 10.3389/fbioe.2018.00199

9.

Ramovecchi P Salati C Zeppieri M . Spontaneous posterior vitreous detachment: a glance at the current literature. World J Exp Med (2021) 11:30–6. doi: 10.5493/wjem.v11.i3.30

10.

Moon SY Park SP Kim Y-K . Evaluation of posterior vitreous detachment using ultrasonography and optical coherence tomography. Acta Ophthalmol (2020) 98:e29–35. doi: 10.1111/aos.14189

11.

Frisina R De Salvo G Tozzi L Gius I Sahyoun JY Parolini B et al . Effects of physiological fluctuations on the estimation of vascular flow in eyes with idiopathic macular pucker. Eye (Lond) (2022) 37:1470–8. doi: 10.1038/s41433-022-02158-4

12.

Tsotridou E Loukovitis E Zapsalis K Pentara I Asteriadis S Tranos P et al . A review of last decade developments on epiretinal membrane pathogenesis. Med Hypothesis Discov Innov Ophthalmol (2020) 9:91–110. PMID:

13.

Bianchi L Altera A Barone V Bonente D Bacci T De Benedetto E et al . Untangling the extracellular matrix of idiopathic epiretinal membrane: a path winding among structure, interactomics and translational medicine. Cells (2022) 11:2531. doi: 10.3390/cells11162531

14.

Myojin S Yoshimura T Yoshida S Takeda A Murakami Y Kawano Y et al . Gene expression analysis of the irrigation solution samples collected during vitrectomy for idiopathic epiretinal membrane. PLoS One (2016) 11:e0164355. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0164355

15.

Sheybani A Harocopos GJ Rao PK . Immunohistochemical study of epiretinal membranes in patients with uveitis. J Ophthalmic Inflamm Infect (2012) 2:243–8. doi: 10.1007/s12348-012-0074-x

16.

Ueki M Morishita S Kohmoto R Fukumoto M Suzuki H Sato T et al . Comparison of histopathological findings between idiopathic and secondary epiretinal membranes. Int Ophthalmol (2016) 36:713–8. doi: 10.1007/s10792-016-0194-7

17.

Yamashita T Uemura A Sakamoto T . Intraoperative characteristics of the posterior vitreous cortex in patients with epiretinal membrane. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol (2008) 246:333–7. doi: 10.1007/s00417-007-0745-8

18.

Hamoudi H . Epiretinal membrane surgery: an analysis of sequential or combined surgery on refraction, macular anatomy and corneal endothelium. Acta Ophthalmol (2018) 96:1–24. doi: 10.1111/aos.13690

19.

Foos RY . Vitreoretinal juncture; epiretinal membranes and vitreous. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci (1977) 16:416–22. PMID:

20.

Wiznia RA . Posterior vitreous detachment and idiopathic preretinal macular gliosis. Am J Ophthalmol (1986) 102:196–8. doi: 10.1016/0002-9394(86)90144-3

21.

Lee GW Lee SE Han SH Kim SJ Kang SW . Characteristics of secondary epiretinal membrane due to peripheral break. Sci Rep (2020) 10:20881. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-78093-9

22.

da Silva RA Roda VM Matsuda M Siqueira PV Lustoza-Costa GJ Wu DC . Cellular components of the idiopathic epiretinal membrane. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol (2022) 260:1435–44. doi: 10.1007/s00417-021-05492-7

23.

Shibuya M. (2011). Vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) and its receptor (VEGFR) signaling in angiogenesis: a crucial target for anti-and pro-Angiogenic therapies. Genes Cancer2:1097–1105. doi: 10.1177/1947601911423031

24.

Vishwakarma S Gupta RK Jakati S Tyagi M Pappuru RR Reddig K et al . Molecular assessment of Epiretinal membrane: activated microglia, oxidative stress and inflammation. Antioxidants (Basel) (2020) 9:654. doi: 10.3390/antiox9080654

25.

Bringmann A Wiedemann P . Involvement of Müller glial cells in epiretinal membrane formation. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol (2009) 247:865–83. doi: 10.1007/s00417-009-1082-x

26.

Colakoglu A Balci AS . Potential role of Müller cells in the pathogenesis of macropsia associated with epiretinal membrane: a hypothesis revisited. Int J Ophthalmol (2017) 10:1759–67. doi: 10.18240/ijo.2017.11.19

27.

Schumann RG Gandorfer A Ziada J Scheler R Schaumberger MM Wolf A et al . Hyalocytes in idiopathic epiretinal membranes: a correlative light and electron microscopic study. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol (2014) 252:1887–94. doi: 10.1007/s00417-014-2841-x

28.

Kohno RI Hata Y Kawahara S Kita T Arita R Mochizuki Y et al . Possible contribution of hyalocytes to idiopathic epiretinal membrane formation and its contraction. Br J Ophthalmol (2009) 93:1020–6. doi: 10.1136/bjo.2008.155069

29.

Tang S Gao R Wu DZ . Macrophages in human epiretinal and vitreal membranes in patients with proliferative intraocular disorders. Yan Ke Xue Bao (1996) 12:28–32. PMID:

30.

Baek J Park HY Lee JH Choi M Lee JH Ha M et al . Elevated M2 macrophage markers in epiretinal membranes with ectopic inner foveal layers. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci (2020) 61:19. doi: 10.1167/iovs.61.2.19

31.

Joshi M Agrawal S Christoforidis JB . Inflammatory mechanisms of idiopathic epiretinal membrane formation. Mediat Inflamm (2013) 2013:192582. doi: 10.1155/2013/192582

32.

Bianchi E Ripandelli G Feher J Plateroti AM Plateroti R Kovacs I et al . Occlusion of retinal capillaries caused by glial cell proliferation in chronic ocular inflammation. Folia Morphol (Warsz) (2015) 74:33–41. doi: 10.5603/FM.2015.0006

33.

Giachos I Chalkiadaki E Andreanos K Symeonidis C Charonis A Georgalas I et al . Epiretinal membrane-induced intraretinal neovascularization. Am J Ophthalmol Case Rep (2021) 23:101180. doi: 10.1016/j.ajoc.2021.101180

34.

Stafiej J Kaźmierczak K Linkowska K Żuchowski P Grzybowski T Malukiewicz G . Evaluation of TGF-Beta 2 and VEGFα gene expression levels in Epiretinal membranes and internal limiting membranes in the course of retinal detachments, proliferative diabetic retinopathy, macular holes, and idiopathic Epiretinal membranes. J Ophthalmol (2018) 2018:8293452. doi: 10.1155/2018/8293452

35.

Rezzola S Guerra J Krishna Chandran AM Loda A Cancarini A Sacristani P et al . VEGF-independent activation of Müller cells by the vitreous from proliferative diabetic retinopathy patients. Int J Mol Sci (2021) 22:2179. doi: 10.3390/ijms22042179

36.

Lennikov A Mukwaya A Fan L Saddala MS De Falco S Huang H . Synergistic interactions of PlGF and VEGF contribute to blood-retinal barrier breakdown through canonical NFκB activation. Exp Cell Res (2020) 397:112347. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2020.112347

37.

Jang DI Lee A-H Shin H-Y Song H-R Park J-H Kang T-B et al . The role of tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α) in autoimmune disease and current TNF-α inhibitors in therapeutics. Int J Mol Sci (2021) 22:2719. doi: 10.3390/ijms22052719

38.

Mirshahi A Hoehn R Lorenz K Kramann C Baatz H . Anti-tumor necrosis factor alpha for retinal diseases: current knowledge and future concepts. J Ophthalmic Vis Res (2012) 7:39–44. PMID:

39.

Andrae J Gallini R Betsholtz C . Role of platelet-derived growth factors in physiology and medicine. Genes Dev (2008) 22:1276–312. doi: 10.1101/gad.1653708

40.

Edqvist PHD Niklasson M Vidal-Sanz M Hallböök F Forsberg-Nilsson K . Platelet-derived growth factor over-expression in retinal progenitors results in abnormal retinal vessel formation. PLoS One (2012) 7:e42488. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0042488

41.

Vinores SA Henderer JD Mahlow J Chiu C Derevjanik NL Larochelle W et al . Isoforms of platelet-derived growth factor and its receptors in epiretinal membranes: immunolocalization to retinal pigmented epithelial cells. Exp Eye Res (1995) 60:607–19. doi: 10.1016/s0014-4835(05)80003-x

42.

Hachana S Larrivée B . TGF-β superfamily signaling in the eye: implications for ocular pathologies. Cells (2022) 11:2336. doi: 10.3390/cells11152336

43.

Kanda A Noda K Hirose I Ishida S . TGF-β-SNAIL axis induces Müller glial-mesenchymal transition in the pathogenesis of idiopathic epiretinal membrane. Sci Rep (2019) 9:673. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-36917-9

44.

Pafumi I Favia A Gambara G Papacci F Ziparo E Palombi F et al . Regulation of Angiogenic functions by angiopoietins through calcium-dependent signaling pathways. Biomed Res Int (2015) 2015:965271:1–14. doi: 10.1155/2015/965271

45.

Joussen AM Ricci F Paris LP Korn C Quezada-Ruiz C Zarbin M . Angiopoietin/Tie2 signalling and its role in retinal and choroidal vascular diseases: a review of preclinical data. Eye (2021) 35:1305–16. doi: 10.1038/s41433-020-01377-x

46.

Tanaka T Narazaki M Kishimoto T . IL-6 in inflammation, immunity, and disease. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol (2014) 6:a016295. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a016295

47.

Ghasemi H . Roles of IL-6 in ocular inflammation: a review. Ocul Immunol Inflamm (2018) 26:37–50. doi: 10.1080/09273948.2016.1277247

48.

Limb GA Kapur S Woon H Franks WA Jones SE Chignell AH . Expression of mRNA for interleukin 6 by cells infiltrating epiretinal membranes in proliferative vitreoretinopathy. Agents Actions (1993) 38:C73–6. doi: 10.1007/BF01991142

49.

Harjunpää H Llort AM Guenther C Fagerholm SC . Cell adhesion molecules and their roles and regulation in the immune and tumor microenvironment. Front Immunol (2019) 10:1078. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2019.01078

50.

Tang S Le-Ruppert KC Gabel VP . Expression of intercellular adhesion molecule-1 (ICAM-1) and vascular cell adhesion molecule-1 (VCAM-1) on proliferating vascular endothelial cells in diabetic epiretinal membranes. Br J Ophthalmol (1994) 78:370–6. doi: 10.1136/bjo.78.5.370

51.

Chiquet M . Tenascin-C: from discovery to structure-function relationships. Front Immunol (2020) 11:611789. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2020.611789

52.

Kobayashi Y Yoshida S Zhou Y Nakama T Ishikawa K Arita R et al . The role of tenascin-C in fibrovascular membrane formation in diabetic retinopathy. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci (2015) 56:224.

53.

Yun YR Won JE Jeon E Lee S Kang W Jo H et al . Fibroblast growth factors: biology, function, and application for tissue regeneration. J Tissue Eng (2010) 2010:218142. doi: 10.4061/2010/218142

54.

Cassidy L Barry P Shaw C Duffy J Kennedy S . Platelet derived growth factor and fibroblast growth factor basic levels in the vitreous of patients with vitreoretinal disorders. Br J Ophthalmol (1998) 82:181–5. doi: 10.1136/bjo.82.2.181

55.

Frank RN Amin RH Eliott D Puklin JE Abrams GW . Basic fibroblast growth factor and vascular endothelial growth factor are present in epiretinal and choroidal neovascular membranes. Am J Ophthalmol (1996) 122:393–403. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9394(14)72066-5

56.

Hueber A Wiedemann P Esser P Heimann K . Basic fibroblast growth factor mRNA, bFGF peptide and FGF receptor in epiretinal membranes of intraocular proliferative disorders (PVR and PDR). Int Ophthalmol (1996) 20:345–50. doi: 10.1007/BF00176889

57.

Ding X Zhang R Zhang S Zhuang H Xu G . Differential expression of connective tissue growth factor and hepatocyte growth factor in the vitreous of patients with high myopia versus vitreomacular interface disease. BMC Ophthalmol (2019) 19:25. doi: 10.1186/s12886-019-1041-1

58.

Shpak AA Guekht AB Druzhkova TA Troshina AA Gulyaeva N . Glial cell line-derived neurotrophic factor in patients with age-related cataract. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci (2021) 62:718.

59.

Nishikiori N Tashimo A Mitamura Y Ohtsuka K . Glial cell line–derived neurotrophic factor in the vitreous of patients with proliferative diabetic retinopathy. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci (2005) 46:3103.

60.

Xiao W Chen X Yan W Zhu Z He M . Prevalence and risk factors of epiretinal membranes: a systematic review and meta-analysis of population-based studies. BMJ Open (2017) 7:e014644. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-014644

61.

Ng CH Cheung N Wang JJ Islam AF Kawasaki R Meuer SM et al . Prevalence and risk factors for epiretinal membranes in a multi-ethnic United States population. Ophthalmology (2010) 118:694–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2010.08.009

62.

Fung AT Galvin J Tran T . Epiretinal membrane: a review. Clin Exp Ophthalmol (2021) 49:289–308. doi: 10.1111/ceo.13914

63.

Stevenson W Prospero Ponce CM Agarwal DR Gelman R Christoforidis JB . Epiretinal membrane: optical coherence tomography-based diagnosis and classification. Clin Ophthalmol (2016) 10:527–34. doi: 10.2147/OPTH.S97722

64.

Govetto A Lalane RA 3rd Sarraf D Figueroa MS Hubschman JP . Insights into Epiretinal membranes: presence of ectopic inner foveal layers and a new optical coherence tomography staging scheme. Am J Ophthalmol (2017) 175:99–113. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2016.12.006

65.

Folk JC Adelman RA Flaxel CJ Hyman L Pulido JS Olsen TW . Idiopathic epiretinal membrane and vitreomacular traction preferred practice pattern(®) guidelines. Ophthalmology (2016) 123:P152–81. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2015.10.048

66.

Matoba R Morizane Y . Surgical treatment of epiretinal membrane. Acta Med Okayama (2021) 75:403–13. doi: 10.18926/AMO/62378

67.

Forlini M Date P D'Eliseo D Rossini P Bratu A Volinia A et al . Limited vitrectomy versus complete vitrectomy for epiretinal membranes: a comparative multicenter trial. J Ophthalmol (2020) 2020:1. doi: 10.1155/2020/6871207

68.

Meduri A Oliverio GW Trombetta L Giordano M Inferrera L Trombetta CJ . Optical coherence tomography predictors of favorable functional response in Naïve diabetic macular edema eyes treated with dexamethasone implants as a first-line agent. J Ophthalmol (2021) 2021:1. doi: 10.1155/2021/6639418

69.

Dawson SR Shunmugam M Williamson TH . Visual acuity outcomes following surgery for idiopathic epiretinal membrane: an analysis of data from 2001 to 2011. Eye (Lond) (2014) 28:219–24. doi: 10.1038/eye.2013.253

70.

Shen Z Duan X Wang F Wang N Peng Y Liu DTL et al . Prevalence and risk factors of posterior vitreous detachment in a Chinese adult population: the Handan eye study. BMC Ophthalmol (2013) 13:33. doi: 10.1186/1471-2415-13-33

Summary

Keywords

epiretinal membrane, macular pucker, myofibroblasts, pre-macular fibrosis, retina, cellophane maculopathy

Citation

Ożóg MK, Nowak-Wąs M and Rokicki W (2023) Pathophysiology and clinical aspects of epiretinal membrane – review. Front. Med. 10:1121270. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2023.1121270

Received

11 December 2022

Accepted

24 July 2023

Published

10 August 2023

Volume

10 - 2023

Edited by

Georgios D. Panos, Nottingham University Hospitals NHS Trust, United Kingdom

Reviewed by

Laura De Luca, University of Messina, Italy; Livio Vitiello, University of Salerno, Italy; Maddalena De Bernardo, University of Salerno, Italy

Updates

Copyright

© 2023 Ożóg, Nowak-Wąs and Rokicki.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Mateusz Kamil Ożóg, mateusz.ozog@sum.edu.pl

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.