Abstract

Introduction:

Within 5 years of having acute pancreatitis (AP), approximately 20% of patients develop diabetes mellitus (DM), which later increases to approximately 40%. Some studies suggest that the prevalence of prediabetes (PD) and/or DM can grow as high as 59% over time. However, information on risk factors is limited. We aimed to identify risk factors for developing PD or DM following AP.

Methods:

We systematically searched three databases up to 4 September 2023 extracting direct, within-study comparisons of risk factors on the rate of new-onset PD and DM in AP patients. When PD and DM event rates could not be separated, we reported results for this composite outcome as PD/DM. Meta-analysis was performed using the random-effects model to calculate pooled odds ratios (OR) with 95% confidence intervals (CI).

Results:

Of the 61 studies identified, 50 were included in the meta-analysis, covering 76,797 participants. The studies reported on 79 risk factors, and meta-analysis was feasible for 34 risk factor and outcome pairs. The odds of developing PD/DM was significantly higher after severe and moderately severe AP (OR: 4.32; CI: 1.76–10.60) than mild AP. Hypertriglyceridemic AP etiology (OR: 3.27; CI: 0.17–63.91) and pancreatic necrosis (OR: 5.53; CI: 1.59–19.21) were associated with a higher risk of developing PD/DM. Alcoholic AP etiology (OR: 1.82; CI: 1.09–3.04), organ failure (OR: 3.19; CI: 0.55–18.64), recurrent AP (OR: 1.89; CI: 0.95–3.77), obesity (OR: 1.85; CI: 1.43–2.38), chronic kidney disease (OR: 2.10; CI: 1.85–2.38), liver cirrhosis (OR: 2.48; CI: 0.18–34.25), and dyslipidemia (OR: 1.82; CI: 0.68–4.84) were associated with a higher risk of developing DM.

Discussion:

Severe and moderately severe AP, alcoholic and hypertriglyceridemic etiologies, pancreatic necrosis, organ failure, recurrent acute pancreatitis and comorbidities of obesity, chronic kidney disease liver disease, and dyslipidemia are associated with a higher risk of developing PD or DM.

Systematic review registration::

https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/prospero/, identifier CRD42021281983.

1 Introduction

Acute pancreatitis (AP) is characterized by premature activation of pancreatic enzymes leading to autodigestion and inflammation of the pancreatic tissue. Potential short-term complications include acute pancreatic fluid collection, pancreatic necrosis, and organ failure (1). Patients with preexisting diabetes mellitus (DM) have an increased risk of developing complications during an AP episode (2). Additionally, elevated glucose levels during hospitalization are associated with more severe AP episodes and increased mortality rates (3). Moreover, it is gaining recognition that DM might also develop after AP as a potential long-term complication (4, 5).

A large population-based study of 14,830 people found that compared to the general population the risk of DM is 2-fold having had a single episode of mild AP (6). Multiple meta-analyses found that within 5 years of an AP episode 18–20% of the patients develop DM, which later increases to approximately 37–40% (7, 8). New-onset prediabetes (PD) is also frequent. Das et al. found the combined incidence of PD and DM to be 35% in the first year following the first AP episode, increasing to 59% after 5 years (7). Not only is the risk of these conditions substantially increased in the context of AP, but their therapy is also challenging. Post-AP DM is recognized as a distinct subtype of DM (9) with more frequent hypoglycemic events (10, 11) and simultaneously greater insulin needs (5, 12, 13) than type 2 DM.

Studies focusing on acute pancreatitis patients with extended follow-up periods are limited (14) and investigations into the implications of developing post-AP DM are even more scarce. Compared to type 2 DM, post-AP DM carries a higher risk of cardiovascular and cerebrovascular disease based on cohort studies exceeding 150,000 patients (5, 11). A population-based matched cohort study of 10,549 individuals in New Zealand reported higher cancer-related deaths (not including pancreatic cancer) and increased mortality from gastrointestinal and infectious diseases in patients with post-AP DM compared to type 2 DM (15). Patients with post-AP DM also have an increased risk of all-cause mortality compared to patients with type 2 DM (5, 10, 11).

Therefore, it is essential to understand the risk factors of developing PD and DM after AP, to facilitate prompt diagnosis and treatment. Two previous meta-analyses provided data on possible risk increasing features, but with conflicting results (7, 8). One possible reason is that instead of pooling direct within-study comparisons these studies used analytical methods conferring a significantly higher risk of bias and less accurate estimations, i.e., meta-regression of PD and DM based on the proportion of a proposed risk factor, indirect comparison of PD and DM prevalence in individuals with different proposed risk factors. The number of analyzed variables was also very limited (to severity, alcoholic and biliary etiology, necrosis, age, sex, follow-up length, and publication year).

We aimed to conduct a comprehensive systematic review and meta-analysis of all available risk factors for PD and DM development after AP, including only studies where prognostic factors are directly compared, allowing for more reliable conclusions.

2 Methods

2.1 Protocol and reporting

Our review followed the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews (16) and adhered to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) 2020 guideline (Supplementary Table S1) (17). The study protocol was registered with the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO, CRD42021281983).

2.2 Eligibility criteria

Our study aimed to investigate risk factors for developing PD and DM following AP, via analyzing all factors assessed during the hospitalization with AP, that were compared between new-onset PD or DM and normal glucose regulation groups. To establish the eligibility criteria, we used the PECOTS framework.

Population (P): adult AP patients without confirmed DM at discharge. Exposure and comparator (E): any factor assessed at the time of hospitalization with AP and (C) its control group, such as severe vs. non-severe AP, necrosis vs. absence of necrosis, smoking vs. not smoking, male vs. female. Classification of AP severity has changed over the years. Our study group’s data in two ways firstly comparing severe AP (SAP) vs. moderately severe and mild AP as one group and alternatively comparing SAP and moderately severe AP as one group vs. mild AP. Some studies applied classification criteria with only two categories: severe and non-severe AP. These studies defined SAP based on 1992 Atlanta criteria (18–21), Scoring ≥8 on APACHE II (22), ≥3 Ranson score (23), and ≥ 2 Japanese severity score (24). We analyzed the findings of these studies using the categories of SAP vs. moderate and mild AP as one group.

Outcome (O): Number of AP patients who developed, after hospital discharge: DM or PD (impaired fasting glucose, impaired glucose tolerance, and HbA1c ≥5.7 and < 6.5%) as reported by the study authors. Multiple studies provided the number of patients who developed PD or DM combined; we included this composite outcome in our analyses as PD/DM. In case of studies providing incomplete or no definition for glycemic outcomes or not stating explicitly that preexisting DM was excluded from the cohort, this uncertainty was taken into account during the risk of bias assessment.

Timing (T): Initially, we planned to include studies assessing the outcome at least 3 months after hospital discharge. However, we decided to deviate and include all studies that reported on the relevant outcomes after hospital discharge because of the limited and heterogeneous data on follow-up and diagnosis time intervals.

Study design (S): The analysis included interventional and observational studies that met the criteria of our review’s PECO framework. Case reports, case series, and studies with less than 10 participants per outcome group or less than 10 participants in the exposed or comparator group were excluded. Conference abstracts were retained.

2.3 Search strategy and selection process

The systematic search was carried out in three databases: MEDLINE (via PubMed), Embase, and Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) from database inception to September 04, 2023 without any filters or restrictions. The main concepts in the search strategy were prediabetes, diabetes, acute, and pancreatitis. See Supplementary Table S2 for the detailed search key and selection process.

2.4 Data collection process and data items

Data collection process is detailed in Supplementary Table S2. Data on the following variables were collected when available: country, year of publication, study period, follow-up time, name and the number of centers, study design, sample size, age, sex and weight of participants, inclusion and exclusion criteria of participants, classification of AP severity, outcome domains reported and their assessment method, and risk factors during the initial AP episode and their definitions. For a complete list of the risk factors investigated in relation to new-onset PD, DM, or PD/DM by the included studies, see Supplementary Table S3.

2.5 Data synthesis

We calculated odds ratios (ORs) with 95% confidence intervals (CI). Refer to Supplementary Table S4 for detailed description.

2.6 Risk of bias

Two independent reviewers (OZ and AK) assessed each study for risk of bias using the Quality In Prognosis Studies (QUIPS) tool (25). Disagreements were resolved by discussion until reaching a consensus. Risk of bias analyses were conducted for each outcome and prognostic factor separately. To simplify and ease the interpretation of these results, three summary Risk of bias assessments were created for the three main outcomes (DM, PD, and PD/DM), taking into account the worst possible scenario for each study and each domain.

2.7 Publication bias

To assess the possibility of publication bias (small study effect), we created and visually assessed funnel plots for every analysis where at least six studies were included. Harbord modified Egger’s test was performed in the case of 10 or more included studies (26), with a p < 0.1 indicating statistical significance for funnel plot asymmetry.

3 Results

3.1 Study selection

The systematic search yielded 14,977 results (Figure 1). Overall, 61 studies with 85 reporting articles were eligible for inclusion. The meta-analysis encompassed 50 studies and 76,797 patients.

Figure 1

PRISMA flow diagram of screened and included studies. PD, Prediabetes; DM, Diabetes mellitus.

3.2 Characteristics of included studies

Key study characteristics are summarized in Table 1. Approximately 68% of the studies were based on the general AP population, four included only SAP patients, six focused on necrotizing AP patients and in 10 studies participants were superselected for other criteria. The outcome was reported as PD, DM, and PD/DM in 6, 43, and 22 studies, respectively. A total of 79 prognostic factors were reported on by at least one study and the unique combinations of prognostic factors and outcomes numbered 137 different comparisons. Meta-analysis was possible in the case of 34 risk factor and outcome pairs.

Table 1

| Study identifier | Country | Study design | Population | Total No. of participants (male %) | Age * (year) | Outcome type | Outcome assessment method | Mean time to follow-up (months)* | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PD | DM | PD/DM | ||||||||

| Akbar et al. (48)† | India | Prospective cohort | AP | 86 (77%) | 36§ ±12¶ | 23.3% | 10.5% | 33.7% | FPG, OGTT, HbA1c | 12§§ |

| Akbar et al. (32) | India | Prospective cohort | AP | 86 (77%) | 33§ (26–44.2)|| | 23.3% | 10.5% | 33.7% | FPG, OGTT, HbA1c | 12§§ |

| Andersson et al. (18) | Sweden | Prospective cohort | AP | 40 (40%) | 61§ (48-68)|| | 33.3% | 23.1% | 56.4% | FPG, OGTT | 42 (36–53) |

| Angelini et al. (53) | Italy | Prospective cohort | ANP | 27 (89%) | NA | 44.4% | 14.8% | 59.3% | OGTT | 12–36|| |

| Bharmal et al. (71)‡ | New Zealand | Cross-sectional | AP | 79 (62%) | 50 (41–63) | 34.2% | NA | NA | FPG, HbA1c | 26 (6–47) |

| Bharmal et al. (50) | New Zealand | Prospective cohort | AP | 120 (58%) | G1: 48 ± 16 ; G2: 54 ± 16 ; G3: 53 ± 20 |

NA | 6.6% | NA | HbA1c | 24§§ |

| Bharmal et al. (72)‡ | New Zealand | Prospective cohort | AP | 68 (47%) | G1: 60 ± 20 ; G2: 55 ± 18 ; G3: 48 ± 15 |

20.5% | NA | NA | FPG, HbA1c | 24 §§ |

| Bojková et al. (55) | Czech Republic | Retrospective cohort | AP progressing to CP in 1–2 years | 56 (52%) | 52** | NA | 21.4% | NA | NA | 12–24|| |

| Boreham and Ammori (61) | United Kingdom | Prospective cohort | AP | 23 (57%) | 55 (21–77) | NA | 17.4% | NA | FPG | 3§§ |

| Burge and Gabaldon-Bates (69) | New Mexico | Retrospective cohort | AP | 887 (56%) | NA | NA | 11.0% | NA | Diagnostic codes | NA |

| Buscher et al. (57) | Netherlands | Prospective case–control | ANP | 20 (75%) | 52** ±3†† | 30.0% | 25.0% | 55.0% | OGTT | 63** (8–136)|| |

| Castoldi et al. (19) | Italy | Cross-sectional | AP | 631 (50%) | 61 ± 19 | NA | 3.5% | NA | Questionnaire | 52 ± 8 |

| Chandrasekaran et al. (73)‡ | India | Prospective cohort | SAP | 35 (83%) | 37§ ±10¶ | NA | 48.6% | NA | OGTT | 26 ± 18 |

| Cho et al. (42) | New Zealand | Retrospective cohort | AP with gout | 9,471 (48%) | 56 ± 19 | NA | 5.9% | NA | Diagnostic codes Medication prescription | 46 ± 34 |

| Cho et al. (64) | New Zealand | Retrospective cohort | MAP, MSAP | 10,870 (49%) | 56 ± 19 | NA | 6.5% | NA | Diagnostic codes, medication prescription | G1: 107 ± 0.4 ; G2: 95 ± 0.6 |

| Chowdhury et al. (38)† | USA | Prospective cohort | AP | 723 (50.2%) | 43 ± 14 | NA | 4.6% | NA | HbA1c | 9–63|| |

| Doepel et al. (56) | Finland | Prospective cohort | SAP | 37 (68%) | 49** (26-90)|| | 10.8% | 54.1% | 64.9% | FPG, OGTT, and HbA1c | 74** (12–168)|| |

| Ermolov et al. (74)‡ | Russia | Prospective cohort | ANP | 210 (69%) | 55 ± 13 | NA | 29.5% | NA | FPG | 102 ± 36 |

| Firkins et al. (43) | United States | Retrospective case–control | AP | 42,818 (47%) | 53** ±0.2‡‡ | NA | 5.9% | NA | Diagnostic code | 12§§ |

| Frey et al. (54) | United States | Retrospective cohort | AP | 306 (69%) | NA | NA | 24.8% | NA | Medication prescription | NA |

| Garip et al. (22) | Turkey | Prospective cohort | AP | 109 (53%) | 57 ± 16 | NA | NA | 34.4% | OGTT | 32** (6-48)|| |

| Gold-Smith et al. (39) | New Zealand | Cross-sectional | AP non-iatrogenic |

93 (61%) | 53 (42–65) | NA | 12.9% | NA | FPG, HbA1c | 22 (7–46) |

| Guo et al. (70) | China | Retrospective cohort | AP | 492 (64%) | G1: 44 (35–54) ; G2: 52 (39–63) |

NA | NA | 31.0% | FPG, OGTT, HbA1c, random blood glucose | 3–60|| |

| Halonen et al. (52) | Finland | Prospective cohort | SAP | 145 (83%) | 44** (20-78)|| | NA | 41.4% | NA | Medical records and questionnaire | 66 ± 32 |

| Hietanen et al. (63) | Finland | Prospective cohort | AP | 62 (84%) | G1: 49§ (21-73)|| ; G2: 55§ (27-80) || |

NA | 8.1% | NA | NA | 31§ (17-53)|| |

| Ho et al. (20) | Taiwan | Retrospective cohort | AP | 12,284 (71%) | NA | NA | 5.0% | NA | Diagnostic codes | 12–120|| |

| Hochman et al. (60) | Canada | Prospective cohort | SAP | 25 (64%) | 59** (37-86)|| | NA | 32.0% | NA | Questionnaire | 24–36|| |

| Huang et al. (75)‡ | China | Prospective cohort | ANP | 50 (52%) | G1: 53 ± 16 ; G2: 51 ± 15 |

NA | Not stated | NA | FPG, random blood glucose | 3–69|| |

| Koziel et al. (44) | Poland | Prospective cohort | MAP, SAP | 150 (63%) | G1: 52 ± 17 ; G2: 57 ± 16 |

NA | 13.5% | NA | HbA1c | G1: 14 ± 4 ; G2: 15 ± 4 |

| Li et al. (47) | New Zealand | Cross-sectional | AP non-iatrogenic | 72 (67%) | G1: 60 (47–67) ; G2: 51 (43–59) |

NA | NA | 50.0% | FPG, HbA1c | 27** ±2‡‡ |

| Lv et al. (37) | China | Retrospective cohort | AP | 1,804 (63%) | 48 (36–62) | NA | 6.1% | NA | Questionnaire | 37 (21–54) |

| Ma et al. (45) | China | Cross-sectional | AP non-iatrogenic | 616 (63%) | 47 (37–63) | NA | 20.0% | NA | OGTT, HbA1c | 3§§ |

| Malecka-Panas et al. (67) | Poland | Prospective cohort | Alcoholic AP with pseudocyst | 50 (68%) | 46 ± 14 | NA | NA | 26.0% | OGTT | 46 ± 20 |

| Malecka-Panas et al. (23) | Poland | Prospective cohort | AP BMI ≤25 kg/m2 | 82 (67%) | 47 ± 8 | 4.9% | 15.9% | 20.3% | OGTT | 56 ± 43 |

| Man et al. (41) | Romania | Prospective cohort | AP | 308 (54%) | G1: 60 § (18-90)|| G2: 45.5 § (40-65)|| |

NA | 2.5% | NA | FPG, OGTT | 12§§ |

| Miko et al. (28)† | Hungary | Prospective cohort | AP | 178 (NA) | NA | 34.3% | 15.7% | 50.0% | OGTT | 12§§ |

| Nikkola et al. (29) | Finland | Prospective cohort | Alcoholic AP | 77 (90%) | 48§ (25-71)|| | 19.1% | 19.1% | 38.2% | FPG, OGTT, HbA1c | 126§ (37–155)|| |

| Nikolic et al. (76)‡ | Sweden, Italy | Retrospective cohort | AP | 35 (48.6%) | 41 § (26-NA)|| | NA | 8.6% | NA | Diagnostic codes, medical records | 54§ |

| Norbitt et al. (65) | New Zealand | Cross-sectional | AP | 69 (59.4%) | NA | NA | NA | 53.6% | FPG, HbA1c | 60§§ |

| Norbitt et al. (77)‡ | New Zealand | Cross-sectional | AP | 69 (59.4%) | NA | NA | NA | 53.6% | FPG, HbA1c | NA |

| Patra and Das (40) | India | Retrospective cohort | AP | 100 (64%) | 42** (14-88)|| | NA | 17.0% | NA | FPG, OGTT | 60§§ |

| Pendharkar et al. (66) | New Zealand | Cross-sectional | AP non-iatrogenic | 83 (60%) | G1: 47 ± 15 ; G2: 57 ± 13 |

NA | NA | 36.1% | FPG, HbA1c | G1: 33 ± 30 ; G2: 23 ± 19 |

| Pendharkar et al. (33) | New Zealand | Cross-sectional | AP non-iatrogenic | 83 (60%) | NA | NA | NA | 36.1% | FPG, HbA1c | 30** |

| Robertson et al. (36) | UK | Prospective cohort | AP | 337 (60%) | G1: 57 (17–90) G2: 58.5 (21–84) |

NA | 11.2% | NA | Insulin prescription | 22 § (11-33)|| |

| Symersky et al. (21) | Netherlands | Prospective cohort | biliary and iatrogenic AP | 34 (47%) | 53** ±3‡‡ | NA | 35.3% | NA | OGTT | 55** (12-90)|| |

| Takeyama (24) | Japan | Retrospective cohort | MSAP, SAP | 714 (NA) | NA | NA | 13.0% | NA | FPG | ≥ 156 |

| Thiruvengadam et al. (78)‡ | USA | Retrospective cohort | AP | 118,479 (NA) | NA | NA | 10.6% | NA | Diagnostic codes, medication prescription | 42§ |

| Trgo et al. (34) | Croatia | Prospective cohort | MAP, MSAP | 33 (100%) | NA | NA | NA | 42.4% | OGTT | 1§§ |

| Trikudanathan et al. (79)†‡ | USA | Prospective cohort | ANP | 390 (66%) | 51 (36–64) | NA | 25.8% | NA | NA | 13 (3–35) |

| Tu et al. (30) | China | Prospective cohort | AP | 113 (66%) | 47** ±1‡‡ | 29.2% | 30.1% | 59.3% | OGTT, HbA1c | 43 ± 4 |

| Tu et al. (46) | China | Prospective cohort | AP | 256 (66%) | 44** ±1‡‡ | NA | NA | 60.2% | FPG, random blood glucose, OGTT | 43 ± 4 |

| Tu et al. (4) | China | Cross-sectional | AP | 88 (NA) | NA | NA | 25.0% | NA | FPG, OGTT, HbA1c | 6–90|| |

| Uomo et al. (68) | Italy | Prospective cohort | ANP | 40 (43%) | 48 ± 18 | NA | 15.8% | NA | FPG, OGTT | 180 ± 13 |

| Vujasinovic et al. (35) | Slovenia | Prospective cohort | AP developing PEI | 21 (81%) | 57 ± 12 | NA | 28.6% | NA | OGTT, HbA1c | 32 ± 52 |

| Walker et al. (62) | Scotland | Prospective cohort | AP | 1,748 (49%) | NA | NA | 13.3% | NA | Diagnostic codes, Medication prescriptions | 73 (62–84) |

| Wu et al. (58) | China | Prospective cohort | AP | 59 (56%) | 59 ± 14 | NA | NA | 30.5% | FPG, HbA1c | 42** (12-72)|| |

| Wundsam et al. (80)‡ | Austria | Retrospective cohort | AP | 302 (59%) | 60 ± 18 | NA | 3.3% | NA | NA | NA |

| Yu et al. (31) | China | Retrospective cohort | AP | 361 (56%) | 49 ± 13 | NA | NA | 41.6% | FPG, OGTT | 24 ± 24 |

| Yuan et al. (27) | China | Retrospective cohort | AP | 310 (60%) | 52 (41–63) | 11.0% | 11.3% | 22.3% | FPG | 36 (22–53) |

| Zhang et al. (81)† ‡ | China | Retrospective cohort | AP | 946 (NA) | NA | NA | 7.0% | NA | NA | 0–48|| |

| Zhang et al. (49) | China | Retrospective cohort | AP | 820 (61.3%) | 50 (38–63) | NA | 8.3% | NA | Diagnostic codes | 3–57|| |

Basic characteristics of the included studies.

NA, Not available; AP, Acute pancreatitis; ANP, Acute necrotizing pancreatitis; CP, Chronic pancreatitis; SAP, Severe acute pancreatitis; MSAP, Moderately severe acute pancreatitis; MAP, Mild acute pancreatitis; DM, Diabetes mellitus; PD, Prediabetes; FPG, Fasting plasma glucose; OGTT, Oral glucose tolerance test; HbA1c, Hemoglobin A1c; G, Group; PEI, Pancreatic exocrine insufficiency; BMI, Body mass index; *Data reported as mean with standard deviation or median with interquartile range, unless otherwise specified; †Conference abstract; ‡Study not included in the meta-analyses; §Median; ¶SD; ||Range; **Mean; ††Standard error of the mean; ‡‡Standard error; and §§Predetermined follow-up time.

3.3 Synthesis of results

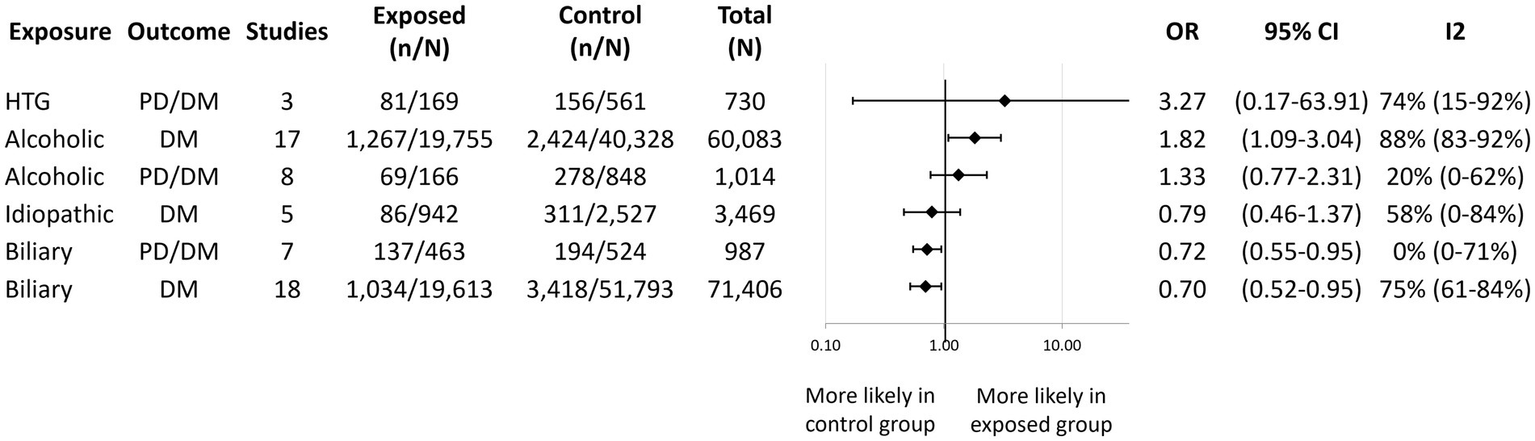

Our findings of the 34 meta-analyses are summarized in an aggregated forest plot, which shows the pooled OR for each risk factor and outcome pair (Figure 2). In addition, per risk factor groups we present the original forest plots or more detailed aggregated forest plots. All other individual plots can be found in the Supplementary material.

Figure 2

Aggregated forest plot summarizing our results for the 34 meta-analyses. Each row shows the pooled odds ratio for a risk factor and outcome pair. An odds ratio over 1.0 indicates that the given outcome (diabetes or PD/DM) is more likely to occur in the exposed group compared to the control group. Statistical significance is achieved if the line of null effect does not fall into the confidence interval. Black squares represent the pooled odds ratios and the lines represent the confidence intervals. PD, Prediabetes; DM, Diabetes mellitus; OR, Odds ratio; CI, Confidence interval; AP, Acute pancreatitis; SAP, Severe acute pancreatitis; MSAP, Moderately severe acute pancreatitis; MAP, Mild acute pancreatitis; HTG, Hypertriglyceridemic; RAP, Recurrent acute pancreatitis; CKD, Chronic kidney disease; and CVD, Cardiovascular disease. *Liver disease other than liver cirrhosis.

3.3.1 AP severity and complications

Having SAP or moderately severe AP was associated with a significantly greater odds of developing PD/DM [OR: 4.32; CI: 1.76–10.60; Figure 3A; (27–34)] and DM [OR: 2.11; CI: 1.30–3.41; Figure 3C; (28, 29, 35–41)] compared to mild disease. SAP was associated with significantly increased odds of developing PD/DM [OR: 3.13; CI: 1.60–6.11; Figure 3B; (18, 22, 23, 27, 28, 30, 31, 33)] and DM [OR: 1.86; CI: 1.27–2.73; Figure 3D; (19–21, 24, 28, 35–37, 41–45)] compared to mild-or-moderate disease.

Figure 3

The association between severity grades of acute pancreatitis (AP) and subsequent development of prediabetes and diabetes. (A) Severe or moderately severe AP vs. mild AP in relation to new-onset prediabetes and diabetes. (B) Severe AP vs. mild or moderately severe AP in relation to new-onset prediabetes and diabetes. (C) Severe or moderately severe AP vs. mild AP and new-onset diabetes. (D) Severe AP vs. mild or moderately severe AP and new-onset diabetes. AP, Acute pancreatitis; OR, Odds ratio; CI, Confidence interval; PD, Prediabetes; DM, Diabetes mellitus; SAP, Severe acute pancreatitis; MSAP, Moderately severe acute pancreatitis; MAP, Mild acute pancreatitis; and vs., versus.

We found a significantly greater odds of developing PD/DM with necrotizing AP [OR: 5.53; CI: 1.59–19.21; (22, 31, 46–48)] and a statistically non-significant tendency with DM [OR: 3.09; CI: 0.98–9.72; (24, 30, 36, 40, 41, 49, 50)] compared to non-necrotizing AP (Figure 4). Sensitivity analysis revealed that leaving out Takeyama (24) from the analysis would lead to a statistically significant OR (4.17; CI: 2.08–8.37) of developing DM in AP patients who had necrosis compared to its absence (Supplementary Figure S28). In this study, the data collection of index AP episode—and thus the evaluation of necrosis—occurred in 1987, which was 24 years earlier than any other study included in the analysis. Notably, computer tomography imaging has improved significantly in that time (51).

Figure 4

Aggregated forest plot showing the pooled odds ratios for various complications of acute pancreatitis and subsequent diabetes and prediabetes development. PD, Prediabetes; DM, Diabetes mellitus; OR, Odds ratio; and CI, Confidence interval.

A limited number of studies allowed for the analysis of the extent of pancreatic necrosis (Figure 4). Necrosis affecting over 50% of the pancreatic tissue was associated with a significantly higher odds of developing DM [OR: 4.12; CI: 1.83–9.30; (30, 36, 41)] compared to smaller proportions affected. We also observed a statistically non-significant tendency for developing PD/DM in patients whose pancreas was at least 30% necrotic [OR: 5.44; CI: 0.19–157.71; (30–32)].

Similarly, only a statistically non-significant tendency could be observed in case of any organ failure (regardless of organ and duration of impairment) and DM [OR: 3.19; CI: 0.55–18.64; (36, 40, 45, 52)] or PD/DM [OR: 2.14; CI: 0.51–9.06; (31, 32, 46); Figure 4].

3.3.2 AP etiology and recurrent AP

We conducted quantitative syntheses assessing the risk of PD/DM after alcoholic, biliary, and hypertriglyceridemia-induced AP, and the risk of DM after alcoholic, biliary, and idiopathic AP (Figure 5). We found that alcoholic AP patients had a higher odds of developing DM [OR: 1.82; CI: 1.09–3.04; I2 = 88%; (18, 20, 24, 35–40, 43, 45, 50, 53–57)] compared to patients with non-alcoholic AP. Moreover, after conducting a subgroup analysis based on follow-up time, we found reduced statistical heterogeneity (I2 = 57%) as well as a possible increasing effect over time (Supplementary Figure S6). While not reaching statistical significance, we observed a tendency of increased risk of new-onset PD/DM following alcoholic [OR: 1.33; CI: 0.77–2.31; (23, 27, 31, 33, 53, 57–59)] and hypertriglyceridemic AP [OR: 3.27; CI: 0.17–63.91; (27, 31, 58)] as well. Biliary etiology was associated with a significantly lower odds of developing DM [OR: 0.70; CI: 0.52–0.95; (18, 20, 24, 35–38, 41–43, 45, 50, 54, 55, 57, 60–62)] and PD/DM [OR: 0.72; CI: 0.55–0.95; (23, 27, 31, 33, 47, 57, 58)] compared to other etiologies. A statistically non-significant reducing trend could be observed for idiopathic AP and DM development [OR: 0.79; CI: 0.46–1.37; (24, 37, 45, 54, 55)].

Figure 5

Aggregated forest plot showing the pooled odds ratios for different etiologies of acute pancreatitis and new-onset diabetes alone or in combination with prediabetes. Etiologies listed in the exposure column are compared to all other etiologies to provide an odds ratio for the outcome of interest. PD, Prediabetes; DM, Diabetes mellitus; HTG, Hypertriglyceridemic; OR, Odds ratio; and CI, Confidence interval.

We observed a near statistically significant increased odds of DM [OR: 1.89; CI: 0.95–3.77; Figure 6A; (4, 20, 29, 35–37, 41–43, 50)] and PD/DM [OR: 1.72; CI: 0.92–3.20; Figure 6B; (23, 27, 29, 33, 47)] recurrent acute pancreatitis (RAP) compared to a single AP episode. Subgroup analysis for follow-up length found no effect of time; however, few studies made up each subgroup. Some studies explored the effect of different numbers of AP episodes. Three or more episodes of AP were associated with a near statistically significant increased odds of DM [OR: 2.53; CI: 0.95–6.74; (4, 20, 41)] compared to having one or two AP episodes (Supplementary Figure S10).

Figure 6

The association between recurrent acute pancreatitis and subsequent development of diabetes (A) and prediabetes or diabetes (B). PD, Prediabetes; DM, Diabetes mellitus; OR, Odds ratio; CI, Confidence interval; AP, Acute pancreatitis; and RAP, Recurrent acute pancreatitis.

3.3.3 Demographic factors and comorbidities

Figure 7 displays the pooled OR for the remainder of the prognostic factors that were reported on by a sufficient number of included studies in a comparable manner for quantitative synthesis (see Supplementary Figures S11–S22 for individual forest plots). We found that obesity (29, 39, 41, 43, 49, 50, 62) and chronic kidney disease (36, 38, 43) were associated with a significantly higher odds of developing DM (OR: 1.85; CI: 1.43–2.38 and OR: 2.10; CI: 1.85–2.38, respectively). We observed a statistically non-significant tendency of increased odds of developing DM with liver cirrhosis (20, 38, 63), other liver disease (37, 43, 64), dyslipidemia (20, 37, 42, 43), and being overweight or obese (37, 41, 50). We found no association between new-onset DM and hypertension (20, 36, 37, 43), cardiovascular disease (20, 36–38, 43), or age (20, 38, 43). Smoking (29, 31, 36–38, 43, 64–66), alcohol consumption (29, 31, 36, 37, 64, 67), and male sex (20, 27, 31–33, 35–38, 41, 42, 47, 50, 61, 62, 68–70) were not associated with either new-onset DM or PD/DM.

Figure 7

Aggregated forest plot showing the pooled odds ratios for various comorbidities, demographic factors, and new-onset diabetes alone or in combination with prediabetes. PD, Prediabetes; DM, Diabetes mellitus; OR, Odds ratio; CI, Confidence interval; CKD, Chronic kidney disease; and CVD, Cardiovascular disease. *Liver diseases other than liver cirrhosis. †Drinking refers to alcohol consumption.

3.3.4 Additional risk factors and outcomes

There were 55 additional prognostic factors investigated by the included studies that could not be meta-analyzed due to an insufficient number of reports or heterogeneity. See Supplementary Table S5 for the qualitative analysis, which includes the 11 eligible studies that could not be meta-analyzed (71–81).

3.4 Evaluation of bias and heterogeneity

Overall, the proportion of the high risk of bias studies was notable (32–44%) for all three outcome factors (Supplementary Figures S23–S25). This was primarily due to a lack of reporting on study attrition and suboptimal definitions of outcome measurements.

High heterogeneity was noted in several of our analyses. Subgroup analysis for follow-up length significantly reduced heterogeneity only for new-onset DM in relation to alcoholic etiology. For the other prognostic factors, heterogeneity remained high even after accounting for follow-up time.

Of the 34 risk factor and outcome pairs that could be meta-analyzed, sensitivity analysis was feasible in the case of 14 analyses (Supplementary Figures S26–S34). Leave-one-out analysis identified one study (24), whose omission would make a significant difference, which we reported in paragraph 3.3.1.

Publication bias assessment was limited to six meta-analyses on new-onset DM: severe AP, moderately severe and severe AP, alcoholic and biliary etiology, recurrent AP, and male sex (Supplementary Figures S35–S40). Possible small study publication bias was detected in the case of alcoholic etiology in relation to DM development based on Egger’s test and visual inspection of the funnel plot.

4 Discussion

This is the first systematic review and meta-analysis of risk factors for developing new-onset PD and DM after AP that pooled direct, within-study comparisons. We found that severe AP, moderately severe AP, and necrosis are associated with a greater risk of developing DM and PD/DM. We also observed a significant association with alcoholic etiology, obesity, chronic kidney disease, and new-onset DM, whereas biliary etiology was associated with a lower risk of developing DM and PD/DM compared to other etiologies. Additionally, we observed a tendency for increased risk of developing DM or PD/DM with hypertriglyceridemic AP, organ failure, RAP, and comorbidities of liver disease or dyslipidemia.

4.1 Severity and local complications

Past meta-analyses applying indirect comparisons found conflicting results regarding the association of AP severity and new-onset PD or DM (7, 8). Our analysis of direct, within-study comparisons confirms a positive relationship between SAP, moderately severe AP, and new-onset DM. Classification of AP severity is based on the development of local complications (such as necrosis) and organ failure (1). Beta cell death secondary to local complications of AP is believed to be one of the possible mechanisms behind the ensuing DM (82). Our meta-analysis supports this hypothesis as necrosis was associated with significantly greater risk of developing DM and PD/DM. Moreover, patients with local complications might require interventions such as pancreatic debridement, lavage, drainage, necrosectomy, and partial pancreatectomy, during which further pancreatic tissue is lost (83).

Nevertheless, cell death is only one aspect of the complex pathomechanism of post-AP DM. It was proposed that the inflammation accompanying AP stimulates endogenous beta-cell proteins to undergo post-translational modifications (84). Such modified proteins could trigger autoimmune processes as seen in type 1 diabetes (85), which could explain the earlier and greater need for insulin therapy seen with post-pancreatitis DM compared to type 2 DM (12). The level of inflammatory cytokines correlate well with persistent organ failure, which is the hallmark of SAP (86). Our study found an increase in the odds of developing DM and PD/DM after AP with organ failure, albeit not-statistically significant. It is noteworthy that none of the included studies specified the duration of the organ failure, and few mentioned the affected organs or the number of organs affected.

We found a more pronounced association with severity in the case of PD/DM than with DM suggesting an even more substantial influence of AP severity on the development of PD. Moreover, comparing severe and moderate AP as one group vs. mild yielded a higher odds ratio than the comparison of SAP to moderate and mild AP as one group. This could imply that progresses from mild to moderate AP severity has a greater impact on PD and DM development compared to the step from moderate to severe disease progression.

4.2 Etiology

We found that alcoholic AP was associated with an increased risk of developing DM. Alcohol has a toxic effect on the pancreas. Its metabolites elicit sustained intracellular calcium overload, which disrupts beta-cell functioning and insulin secretion while also leading to oxidative stress (87), to which beta-cells are especially vulnerable due to their low antioxidation capacity (88).

The most likely explanation for the tendency seen with hypertriglyceridemic etiology is that hypertriglyceridemia itself is associated with DM (89). The two conditions often coexist in metabolic syndrome. Analysis of the Hungarian Study Group’s registry data shows that 69% of the non-diabetic hypertriglyceridemic AP patients present with at least two factors of the metabolic syndrome on admission and they are at an increased risk of developing post-AP DM (90). Therefore, the development of DM might be a natural progression of the disease, possibly quickened by the AP episode.

Acute pancreatitis tends to be more severe if caused by excessive alcohol consumption or hypertriglyceridemia (91) and if metabolic syndrome is present (90). Toxic factors (e.g., alcohol and fatty acids) play a role in the development and severity of pancreatitis when they accumulate (92). This aligns with the multiple hits theory of AP severity documented for smoking, drinking (93), obesity, hypertension, and hyperlipidemia (90). The risk factors we identified—local complications, severity, alcoholic, and hypertriglyceridemic AP—often coexist (91, 94, 95). Suggesting that the development of post-AP DM might work on a similar multiple hits theory basis.

Both alcoholic and hypertriglyceridemic etiologies are linked to poor dietary habits that are difficult to change and the ongoing exposure conveys a high risk for RAP, progression of the disease, and development of complications (96). On the contrary, the recurrence of biliary AP is often prevented by cholecystectomy after the index episode (64). Without identifying a treatable or preventable etiology, there is a risk for RAP. However, we found no association between idiopathic AP and DM development, possibly due to the control group—containing alcoholic and hypertriglyceridemic etiology—demonstrating a positive association with DM.

4.3 Recurrence

Recurrent acute pancreatitis conveys repeated pancreatic inflammation and cellular insult or loss, leading to an assumed association with developing pancreatic endocrine dysfunction (96). Our analysis found a tendency of increased odds for new-onset DM and PD/DM with RAP, which neared statistical significance. It should be pointed out that there was considerable heterogeneity in the study designs. Some studies excluded patients presenting with RAP at the index AP episode while others included them. Importantly, those who had RAP and developed DM by the index AP episode were excluded from the analysis based on the premise of pre-existing DM. Moreover, 60% of the analyzed studies had a relatively short follow-up of less than 3 years. Finally, different distributions of the etiological factors among the included studies might influence the observed association between RAP and DM or PD/DM, as alcoholic and hypertriglyceridemic APs are associated with a greater risk of RAP (91). All four factors could influence the true relationship between disease recurrence and PD/DM development.

4.4 Other factors

Our study found that obesity was associated with a significantly greater risk of new-onset DM. Some of the other risk factors we identified for new-onset DM after AP (hypertriglyceridemic AP, AP-related complications, and SAP) tend to occur more frequently in obese individuals (90, 97). Moreover, excess weight is a known independent risk factor for type 2 DM. Therefore, it could be a natural progression of the disease or AP might even trigger DM in genetically or metabolically predisposed patients (7). At present, there is still a lack of consensus on differentiating type 2 DM from post-AP DM in patients who had an AP episode (7, 98). Most studies define post-AP DM as new-onset of hyperglycemia (using the standard cutoff values for DM as per the World Health Organization or American Diabetes Association recommendations) following an AP episode (12, 13, 99). The prospective, multi-center DREAM study (Diabetes RElated to Acute Pancreatitis and Its Mechanisms) was recently designed to characterize the DM phenotypes after AP and their pathomechanism (100, 101).

We found no association between sex, smoking, alcohol consumption, and DM or PD/DM. The lack of association with alcohol consumption is paradoxical in light of the increased risk of DM with AP of alcoholic etiology. However, the included studies mostly compared alcohol consumption to not-drinking, not taking into account the amount and duration of alcohol consumption. Studies with follow-up length over 4 years were more likely to favor an association between alcohol consumption and new-onset DM or PD/DM (29, 64, 67) compared to shorter studies (31, 36, 37). Also, the analysis included only four and three studies for DM and PD/DM, respectively, with two of the studies containing unusually low proportions of alcoholic etiology (4 and 14%) and three studies including only patients with AP of alcoholic etiology.

Additionally, we observed a clinically relevant odds ratio for post-AP DM with liver disease and dyslipidemia. We believe that statistical significance was not achieved due to the low number of studies investigating these risk factors and their heterogeneous nature. In our analysis, chronic kidney disease was associated with a significantly higher risk of post-AP DM. It is notable that the analysis was based on three studies, of which Firkins et al. (43) accounted for 99.4% of the pooled results due to the large sample size. This is a retrospective nationwide database analysis, where only patients with a second hospital admission within one calendar year were included. Patients with chronic kidney disease are admitted more frequently to hospitals (102); thus, they were likely over-represented in the study by Firkins et al. (43).

4.5 Follow-up after AP

Timely translation of scientific data to clinical practice has crucial importance in healthcare (103, 104). Long-term complications of AP (exocrine and endocrine insufficiency) were documented as early as 1941 (105); nonetheless, the Chinese guideline in 2021 was the first to recommend follow-up visits after AP (59). They recommend that all AP patients should be monitored after rehabilitation, however, for different lengths of time depending on severity. They rated the strength of recommendation and supporting evidence weak.

While all AP patients should be followed up for the development of long-term complications after AP, financial and human resources are often limited in healthcare. Our study highlights the sub-populations of AP patients who are at a higher risk for developing PD or DM. Therefore, more frequent follow-ups of these patients increase the likelihood of preventing and reducing post-AP diabetes-related morbidity, mortality, and healthcare costs.

4.6 Strengths and limitations

Due to the broad search strategy and lack of constraints on the results, this is the first comprehensive systematic analysis of potential risk factors for new-onset PD/DM following AP, with the largest number of included studies (50 in total) covering 76,797 participants in the meta-analysis. Our study was based on direct, within-study comparisons; therefore, it is more representative of the true effect of risk factors compared to previous meta-analyses (7, 8). Due to the inclusive nature of our research, there was substantial heterogeneity between the studies, which we attempted to reduce by performing separate analyses for PD/DM and DM and conducting subgroup analysis for follow-up length. Almost a third of the meta-analyses were based on three studies. For these risk factor and outcome pairs, conclusions should be cautiously handled.

4.7 Implication for practice

All patients require medical follow-up for endocrine and exocrine insufficiency after AP. Our results show that patients who have suffered severe or moderately severe AP, alcoholic or hypertriglyceridemic AP, develop pancreatic necrosis or organ failure, had multiple AP episodes, are obese or have pre-existing chronic kidney disease, liver disease or dyslipidemia are at a greater risk for developing PD or DM. Therefore, closer monitoring is warranted in these high-risk groups.

4.8 Implication for research

Further long-term follow-up studies of AP patients are needed to observe morbidity and mortality following single and multiple AP episodes as well. High-quality well-controlled observational studies with long follow-up duration are needed to establish an evidence-based follow-up schedule after AP to help identify patients early in a prediabetic state, where interventions could still prevent DM. Future studies should also explore interventions for preventing post-pancreatitis DM. In 2022 the Hungarian Pancreatic Study Group launched two longitudinal randomized controlled trials on dietary intervention (106) and smoking and alcohol cessation following hospitalization for AP (107).

4.9 Conclusion

We found that AP severity, alcoholic and hypertriglyceridemic etiologies, pancreatic necrosis, organ failure, RAP and comorbidities of obesity, chronic kidney disease, liver disease, and dyslipidemia are associated with a higher risk of developing PD or DM following AP. Glucose homeostasis should be regularly monitored in high-risk populations after hospital discharge. Further research is needed to establish an appropriate follow-up schedule and interventions for preventing DM after AP.

Glossary

| ANP | Acute necrotizing pancreatitis |

| AP | acute pancreatitis |

| BMI | Body mass index |

| CENTRAL | Cochrane central register of controlled trials |

| CI | 95% Confidence interval |

| CKD | Chronic kidney disease |

| CP | Chronic pancreatitis |

| CVD | Cardiovascular disease |

| DM | Diabetes mellitus |

| DREAM | Diabetes RElated to Acute Pancreatitis and Its Mechanisms |

| FPG | Fasting plasma glucose |

| G | Group |

| HbA1c | Hemoglobin A1c |

| HTG | Hypertriglyceridemic |

| MAP | Mild acute pancreatitis |

| MSAP | Moderately severe acute pancreatitis |

| NA | Not available |

| OGTT | Oral glucose tolerance test |

| OR | Odds ratio |

| PD | Prediabetes |

| PECOTS | Population, exposure, comparator, outcome, timing, study design |

| PEI | Pancreatic exocrine insufficiency |

| PRISMA | Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses |

| PROSPERO | International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews |

| QUIPS | Quality In Prognosis Studies |

| RAP | Recurrent acute pancreatitis |

| SAP | Severe acute pancreatitis |

Statements

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author contributions

OZ: Conceptualization, Writing – review & editing, Data curation, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Visualization, Writing – original draft. SB: Conceptualization, Methodology, Project administration, Visualization, Writing – review & editing. AK: Investigation, Writing – review & editing. DD: Investigation, Writing – review & editing, Visualization. LH: Visualization, Investigation, Writing – review & editing. BB: Investigation, Writing - review & editing. DV: Data curation, Visualization, Conceptualization, Writing – review & editing, Formal analysis, Methodology. NH: Conceptualization, Writing – review & editing, Methodology. BE: Writing – review & editing, Conceptualization, Methodology. BT: Writing – review & editing, Methodology, Project administration, Visualization. MJ: Writing – review & editing, Conceptualization, Methodology, Supervision. PH: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Supervision, Writing – review & editing, Methodology.

Funding

The author(s) declare financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. The research was supported by the Hungarian Ministry of Innovation and Technology, National Research, Development and Innovation Fund (TKP2021-EGA-23 to PH), Translational Neuroscience National Laboratory program (RRF-2.3.1-21-2022-00011 to PH), a project grant (K131996 and K147265 to PH) and the Translational Medicine Foundation.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

The author(s) declared that they were an editorial board member of Frontiers, at the time of submission. This had no impact on the peer review process and the final decision.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fmed.2023.1257222/full#supplementary-material

References

1.

Banks PA Bollen TL Dervenis C Gooszen HG Johnson CD Sarr MG et al . Classification of acute pancreatitis—2012: revision of the Atlanta classification and definitions by international consensus. Gut. (2013) 62:102–11. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2012-302779

2.

Mikó A Farkas N Garami A Szabó I Vincze Á Veres G et al . Preexisting diabetes elevates risk of local and systemic complications in acute pancreatitis: systematic review and meta-analysis. Pancreas. (2018) 47:917–23. doi: 10.1097/mpa.0000000000001122

3.

Nagy A Juhász MF Görbe A Váradi A Izbéki F Vincze Á et al . Glucose levels show independent and dose-dependent association with worsening acute pancreatitis outcomes: post-hoc analysis of a prospective, international cohort of 2250 acute pancreatitis cases. Pancreatology. (2021) 21:1237–46. doi: 10.1016/j.pan.2021.06.003

4.

Tu X Liu Q Chen L Li J Yu X Jiao X et al . Number of recurrences is significantly associated with the post-acute pancreatitis diabetes mellitus in a population with hypertriglyceridemic acute pancreatitis. Lipids Health Dis. (2023) 22:82. doi: 10.1186/s12944-023-01840-0

5.

Jang DK Choi JH Paik WH Ryu JK Kim Y-T Han K-D et al . Risk of cardiovascular disease and mortality in patients with diabetes and acute pancreatitis history: a nationwide cohort study. Sci Rep. (2022) 12:18730. doi: 10.1038/s41598-022-21852-7

6.

Shen HN Yang CC Chang YH Lu CL Li CY . Risk of diabetes mellitus after first-attack acute pancreatitis: a national population-based study. Am J Gastroenterol. (2015) 110:1698–706. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2015.356

7.

Das SL Singh PP Phillips AR Murphy R Windsor JA Petrov MS . Newly diagnosed diabetes mellitus after acute pancreatitis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Gut. (2014) 63:818–31. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2013-305062

8.

Zhi M Zhu X Lugea A Waldron RT Pandol SJ Li L . Incidence of new onset diabetes mellitus secondary to acute pancreatitis: a systematic review and Meta-analysis. Front Physiol. (2019) 10:637. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2019.00637

9.

World Health Organization . Classification of Diabetes Mellitus. Geneva: WHO (2019). 2019 p.

10.

Olesen SS Viggers R Drewes AM Vestergaard P Jensen MH . Risk of major adverse cardiovascular events, severe hypoglycemia, and all-cause mortality in Postpancreatitis diabetes mellitus versus type 2 diabetes: a Nationwide population-based cohort study. Diabetes Care. (2022) 45:1326–34. doi: 10.2337/dc21-2531

11.

Lee N Park SJ Kang D Jeon JY Kim HJ Kim DJ et al . Characteristics and clinical course of diabetes of the exocrine pancreas: a Nationwide population-based cohort study. Diabetes Care. (2022) 45:1141–50. doi: 10.2337/dc21-1659

12.

Woodmansey C McGovern AP McCullough KA Whyte MB Munro NM Correa AC et al . Incidence, demographics, and clinical characteristics of diabetes of the exocrine pancreas (type 3c): a retrospective cohort study. Diabetes Care. (2017) 40:1486–93. doi: 10.2337/dc17-0542

13.

Viggers R Jensen MH Laursen HVB Drewes AM Vestergaard P Olesen SS . Glucose-lowering therapy in patients with postpancreatitis diabetes mellitus: a nationwide population-based cohort study. Diabetes Care. (2021) 44:2045–52. doi: 10.2337/dc21-0333

14.

Czapári D Váradi A Farkas N Nyári G Márta K Váncsa S et al . Detailed characteristics of post-discharge mortality in acute pancreatitis. Gastroenterology. (2023) 165:682–95. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2023.05.028

15.

Cho J Scragg R Petrov MS . Risk of mortality and hospitalization after post-pancreatitis diabetes mellitus vs type 2 diabetes mellitus: a population-based matched cohort study. Am J Gastroenterol. (2019) 114:804–12. doi: 10.14309/ajg.0000000000000225

16.

Higgins J Thomas J Chandler J Cumpston M Li T Page M et al . Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions. Cochrane: John Wiley & Sons (2015).

17.

Page MJ McKenzie JE Bossuyt PM Boutron I Hoffmann TC Mulrow CD et al . The Prisma 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. Br Med J. (2021) 372:n71. doi: 10.1136/bmj.n71

18.

Andersson B Pendse ML Andersson R . Pancreatic function, quality of life and costs at long-term follow-up after acute pancreatitis. World J Gastroenterol. (2010) 16:4944–51. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v16.i39.4944

19.

Castoldi L De Rai P Zerbi A Frulloni L Uomo G Gabbrielli A et al . Long term outcome of acute pancreatitis in Italy: results of a multicentre study. Dig Liver Dis. (2013) 45:827–32. doi: 10.1016/j.dld.2013.03.012

20.

Ho TW Wu JM Kuo TC Yang CY Lai HS Hsieh SH et al . Change of both endocrine and exocrine insufficiencies after acute pancreatitis in non-diabetic patients: a Nationwide population-based study. Medicine (Baltimore). (2015) 94:e1123. doi: 10.1097/md.0000000000001123

21.

Symersky T van Hoorn B Masclee AA . The outcome of a long-term follow-up of pancreatic function after recovery from acute pancreatitis. J Pancreas. (2006) 7:447–53.

22.

Garip G Sarandöl E Kaya E . Effects of disease severity and necrosis on pancreatic dysfunction after acute pancreatitis. World J Gastroenterol. (2013) 19:8065–70. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v19.i44.8065

23.

Malecka-Panas E Gasiorowska A Kropiwnicka A Zlobinska A Drzewoski J . Endocrine pancreatic function in patients after acute pancreatitis. Hepato-Gastroenterology. (2002) 49:1707–12. PMID:

24.

Takeyama Y . Long-term prognosis of acute pancreatitis in Japan. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. (2009) 7:S15–7. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2009.08.022

25.

Hayden JA van der Windt DA Cartwright JL Côté P Bombardier C . Assessing Bias in studies of prognostic factors. Ann Intern Med. (2013) 158:280–6. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-158-4-201302190-00009

26.

Harbord RM Egger M Sterne JA . A modified test for small-study effects in Meta-analyses of controlled trials with binary endpoints. Stat Med. (2006) 25:3443–57. doi: 10.1002/sim.2380

27.

Yuan L Tang M Huang L Gao Y Li X . Risk factors of hyperglycemia in patients after a first episode of acute pancreatitis: a retrospective cohort. Pancreas. (2017) 46:209–18. doi: 10.1097/mpa.0000000000000738

28.

Miko A Lillik V Kato D Verboi M Sarlos P Vincze A et al . Endocrine and exocrine insufficiency after a 2-year follow-up of acute pancreatitis: preliminary results of the goulash-plus study. Pancreatology. (2022b) 22:e3. doi: 10.1016/j.pan.2022.06.015

29.

Nikkola J Laukkarinen J Lahtela J Seppänen H Järvinen S Nordback I et al . The long-term prospective follow-up of pancreatic function after the first episode of acute alcoholic pancreatitis: recurrence predisposes one to pancreatic dysfunction and pancreatogenic diabetes. J Clin Gastroenterol. (2017) 51:183–90. doi: 10.1097/mcg.0000000000000564

30.

Tu J Zhang J Ke L Yang Y Yang Q Lu G et al . Endocrine and exocrine pancreatic insufficiency after acute pancreatitis: long-term follow-up study. BMC Gastroenterol. (2017) 17:114. doi: 10.1186/s12876-017-0663-0

31.

Yu BJ Li NS He WH He C Wan JH Zhu Y et al . Pancreatic necrosis and severity are independent risk factors for pancreatic endocrine insufficiency after acute pancreatitis: a long-term follow-up study. World J Gastroenterol. (2020) 26:3260–70. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v26.i23.3260

32.

Akbar W Unnisa M Tandan M Murthy HVV Nabi Z Basha J et al . New-onset prediabetes, diabetes after acute pancreatitis: a prospective cohort study with 12-month follow-up. Indian J Gastroenterol. (2022) 41:558–66. doi: 10.1007/s12664-022-01288-7

33.

Pendharkar SA Singh RG Petrov MS . Pro-inflammatory cytokine-induced lipolysis after an episode of acute pancreatitis. Arch Physiol Biochem. (2018b) 124:401–9. doi: 10.1080/13813455.2017.1415359

34.

Trgo G Zaja I Bogut A Kovacic Vicic V Meter I Vucic Lovrencic M et al . Association of asymmetric dimethylarginine with acute pancreatitis-induced hyperglycemia. Pancreas. (2016) 45:694–9. doi: 10.1097/mpa.0000000000000516

35.

Vujasinovic M Tepes B Makuc J Rudolf S Zaletel J Vidmar T et al . Pancreatic exocrine insufficiency, diabetes mellitus and serum nutritional markers after acute pancreatitis. World J Gastroenterol. (2014) 20:18432–8. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v20.i48.18432

36.

Robertson FP Lim W Ratnayake B Al-Leswas D Shaw J Nayar M et al . The development of new onset post-pancreatitis diabetes mellitus during hospitalisation is not associated with adverse outcomes. HPB. (2023) 25:1047–55. doi: 10.1016/j.hpb.2023.05.361

37.

Lv Y Zhang J Yang T Sun J Hou J Chen Z et al . Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (Nafld) is an independent risk factor for developing new-onset diabetes after acute pancreatitis: a multicenter retrospective cohort study in Chinese population. Front Endocrinol. (2022) 13:903731. doi: 10.3389/fendo.2022.903731

38.

Chowdhury A Kong N Sun Kim J Hiramoto B Zhou S Shulman IA et al . Predictors of diabetes mellitus following admission for acute pancreatitis: analysis from a prospective observational cohort. Am J Gastroenterol. (2022) 117:e4–5. doi: 10.14309/01.ajg.0000856660.45970.88

39.

Gold-Smith FD Singh RG Petrov MS . Elevated circulating levels of motilin are associated with diabetes in individuals after acute pancreatitis. Exp Clin Endocrinol Diabetes. (2020) 128:43–51. doi: 10.1055/a-0859-7168

40.

Patra PS Das K . Longer-term outcome of acute pancreatitis: 5 years follow-up. JGH Open. (2021) 5:1323–7. doi: 10.1002/jgh3.12679

41.

Man T Seicean R Lucaciu L Istrate A Seicean A . Risk factors for new-onset diabetes mellitus following acute pancreatitis: a prospective study. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. (2022) 26:5745–54. doi: 10.26355/eurrev_202208_29511

42.

Cho J Dalbeth N Petrov MS . Relationship between gout and diabetes mellitus after acute pancreatitis: a Nationwide cohort study. J Rheumatol. (2020) 47:917–23. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.190487

43.

Firkins SA Hart PA Papachristou GI Lara LF Cruz-Monserrate Z Hinton A et al . Identification of a risk profile for new-onset diabetes after acute pancreatitis. Pancreas. (2021) 50:696–703. doi: 10.1097/mpa.0000000000001818

44.

Kozieł D Suliga E Grabowska U Gluszek S . Morphological and functional consequences and quality of life following severe acute pancreatitis. Ann Ital Chir. (2017) 6:403–11. PMID:

45.

Ma JH Yuan YJ Lin SH Pan JY . Nomogram for predicting diabetes mellitus after the first attack of acute pancreatitis. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. (2019) 31:323–8. doi: 10.1097/meg.0000000000001307

46.

Tu J Yang Y Zhang J Yang Q Lu G Li B et al . Effect of the disease severity on the risk of developing new-onset diabetes after acute pancreatitis. Medicine (Baltimore). (2018) 97:e10713. doi: 10.1097/md.0000000000010713

47.

Li X Kimita W Cho J Ko J Bharmal SH Petrov MS . Dietary fibre intake in type 2 and new-onset prediabetes/diabetes after acute pancreatitis: a nested cross-sectional study. Nutrients. (2021) 13. doi: 10.3390/nu13041112

48.

Akbar W Nabi Z Basha J Talukdar R Tandan M Lakhtakia S et al . (2020). “Diabetes is frequent after an episode of acute pancreatitis: a prospective, tertiary care centre study” in 61st Annual Conference of Indian Society of Gastroenterology; Online Indian Journal of Gastroenterology. S1–S127

49.

Zhang J Lv Y Hou J Zhang C Yua X Wang Y et al . Machine learning for post-acute pancreatitis diabetes mellitus prediction and personalized treatment recommendations. Sci Rep. (2023) 13:4857. doi: 10.1038/s41598-023-31947-4

50.

Bharmal SH Cho J Ko J Petrov MS . Glucose variability during the early course of acute pancreatitis predicts two-year probability of new-onset diabetes: a prospective longitudinal cohort study. United European Gastroenterol J. (2022a) 10:179–89. doi: 10.1002/ueg2.12190

51.

Booij R Budde RPJ Dijkshoorn ML van Straten M . Technological developments of X-ray computed tomography over half a century: User’s influence on protocol optimization. Eur J Radiol. (2020) 131:109261. doi: 10.1016/j.ejrad.2020.109261

52.

Halonen KI Pettilä V Leppäniemi AK Kemppainen EA Puolakkainen PA Haapiainen RK . Long-term health-related quality of life in survivors of severe acute pancreatitis. Intensive Care Med. (2003) 29:782–6. doi: 10.1007/s00134-003-1700-8

53.

Angelini G Pederzoli P Caliari S Fratton S Brocco G Marzoli G et al . Long-term outcome of acute necrohemorrhagic pancreatitis. A 4-year follow-up. Digestion. (1984) 30:131–7. doi: 10.1159/000199097

54.

Frey CF . The operative treatment of pancreatitis. Arch Surg. (1969) 98:406–17. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.1969.01340100038003

55.

Bojková M Dítě P Uvírová M Dvořáčková N Kianička B Kupka T et al . Chronic pancreatitis diagnosed after the first attack of acute pancreatitis. Vnitr Lek. (2016) 62:100–4. PMID:

56.

Doepel M Eriksson J Halme L Kumpulainen T Höckerstedt K . Good long-term results in patients surviving severe acute pancreatitis. Br J Surg. (1993) 80:1583–6. doi: 10.1002/bjs.1800801229

57.

Buscher HC Jacobs ML Ong GL van Goor H Weber RF Bruining HA . Beta-cell function of the pancreas after necrotizing pancreatitis. Dig Surg. (1999) 16:496–500. doi: 10.1159/000018775

58.

Wu D Xu Y Zeng Y Wang X . Endocrine pancreatic function changes after acute pancreatitis. Pancreas. (2011) 40:1006–11. doi: 10.1097/MPA.0b013e31821fde3f

59.

Li F Cai S Cao F Chen R Fu D Ge C et al . Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute pancreatitis in China (2021). J Pancreatol. (2021) 4:67–75. doi: 10.1097/jp9.0000000000000071

60.

Hochman D Louie B Bailey R . Determination of patient quality of life following severe acute pancreatitis. Can J Surg. (2006) 49:101–6.

61.

Boreham B Ammori BJ . A prospective evaluation of pancreatic exocrine function in patients with acute pancreatitis: correlation with extent of necrosis and pancreatic endocrine insufficiency. Pancreatology. (2003) 3:303–8. doi: 10.1159/000071768

62.

Walker A O'Kelly J Graham C Nowell S Kidd D Mole DJ . Increased risk of type 3c diabetes mellitus after acute pancreatitis warrants a personalized approach including diabetes screening. BJS Open. (2022b) 6:zrac148. doi: 10.1093/bjsopen/zrac148

63.

Hietanen D Räty S Sand J Mäkelä T Laukkarinen J Collin P . Liver stiffness measured by transient Elastography in patients with acute pancreatitis. Pancreatology. (2014) 14:91–4. doi: 10.1016/j.pan.2014.01.003

64.

Cho J Scragg R Petrov MS . The influence of cholecystectomy and recurrent biliary events on the risk of post-pancreatitis diabetes mellitus: a Nationwide cohort study in patients with first attack of acute pancreatitis. HPB. (2021) 23:937–44. doi: 10.1016/j.hpb.2020.10.010

65.

Norbitt CF Kimita W Ko J Bharmal SH Petrov MS . Associations of habitual mineral intake with new-onset prediabetes/diabetes after acute pancreatitis. Nutrients. (2021) 13:3978. doi: 10.3390/nu13113978

66.

Pendharkar SA Asrani VM Murphy R Cutfield R Windsor JA Petrov MS . The role of gut-brain Axis in regulating glucose metabolism after acute pancreatitis. Clin Transl Gastroenterol. (2017b) 8:e210. doi: 10.1038/ctg.2016.63

67.

Małecka-Panas E Juszyński A Gąsiorowska A Woźniak B Woźniak P . Late outcome of pancreatic pseudocysts-a complication of acute pancreatitis induced by alcohol. Med Sci Monit. (1998) 4:CR465–72.

68.

Uomo G Gallucci F Madrid E Miraglia S Manes G Rabitti PG . Pancreatic functional impairment following acute necrotizing pancreatitis: long-term outcome of a non-surgically treated series. Dig Liver Dis. (2010) 42:149–52. doi: 10.1016/j.dld.2009.08.007

69.

Burge MR Gabaldon-Bates J . The role of ethnicity in post-pancreatitis diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Technol Ther. (2003) 5:183–8. doi: 10.1089/152091503321827849

70.

Guo SY Yang HY Ning XY Guo WW Chen XW Xiong M . Combination of body mass index and fasting blood glucose improved predictive value of new-onset prediabetes or diabetes after acute pancreatitis: a retrospective cohort study. Pancreas. (2022) 51:388–93. doi: 10.1097/mpa.0000000000002025

71.

Bharmal SH Pendharkar SA Singh RG Cameron-Smith D Petrov MS . Associations between ketone bodies and fasting plasma glucose in individuals with post-pancreatitis prediabetes. Arch Physiol Biochem. (2020) 126:308–19. doi: 10.1080/13813455.2018.1534242

72.

Bharmal SH Kimita W Ko J Petrov MS . Cytokine signature for predicting new-onset prediabetes after acute pancreatitis: a prospective longitudinal cohort study. Cytokine. (2022b) 150:155768. doi: 10.1016/j.cyto.2021.155768

73.

Chandrasekaran P Gupta R Shenvi S Kang M Rana SS Singh R et al . Prospective comparison of long term outcomes in patients with severe acute pancreatitis managed by operative and non operative measures. Pancreatology. (2015) 15:478–84. doi: 10.1016/j.pan.2015.08.006

74.

Ermolov AS Blagovestnov DA Rogal ML Omel Yanovich DA . Long-term results of severe acute pancreatitis management. Khirurgiia. (2016) 10:11–5. doi: 10.17116/hirurgia20161011-15

75.

Huang J Xu G Ni M Qin R He Y Meng R et al . Long-term efficacy of endoscopic transluminal drainage for acute pancreatitis complicated with walled-off necrosis or pancreatic pseudocyst. Chin J Digest Endosc. (2022) 39:128–32. doi: 10.3760/cma.j.cn321463-20201021-00757

76.

Nikolic S Lanzillotta M Panic N Brismar TB Moro CF Capurso G et al . Unraveling the relationship between autoimmune pancreatitis type 2 and inflammatory bowel disease: results from two centers and systematic review of the literature. United European Gastroenterol J. (2022) 10:496–506. doi: 10.1002/ueg2.12237

77.

Norbitt CF Kimita W Bharmal SH Ko J Petrov MS . Relationship between habitual intake of vitamins and new-onset prediabetes/diabetes after acute pancreatitis. Nutrients. (2022) 14:1480. doi: 10.3390/nu14071480

78.

Thiruvengadam NR Schaubel DE Forde KA Lee P Saumoy M Kochman ML . Association of Statin Usage and the development of diabetes mellitus after acute pancreatitis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. (2023) 21:1214–1222.e14. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2022.05.017

79.

Trikudanathan G Abdallah MA Munigala S Vantanasiri K Jonason DE Faizi N et al . Predictors for new onset diabetes (nod) following necrotizing pancreatitis (np)—a single tertiary center experience in 525 patients. Gastroenterology. (2022) 162:S-175–6. doi: 10.1016/S0016-5085(22)60418-9

80.

Wundsam HV Spaun GO Bräuer F Schwaiger C Fischer I Függer R . Evolution of transluminal Necrosectomy for acute pancreatitis to stent in stent therapy: step-up approach leads to low mortality and morbidity rates in 302 consecutive cases of acute pancreatitis. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A. (2019) 29:891–9. doi: 10.1089/lap.2018.0768

81.

Zhang J Lv Y Li L . Stress Hyperglycaemia is associated with an increased risk of Postacute pancreatitis diabetes. Diabetologia. (2022) 65:1–469. doi: 10.1007/s00125-022-05755-w

82.

Ciochina M Balaban DV Manucu G Jinga M Gheorghe C . The impact of pancreatic exocrine diseases on the Beta-cell and glucose metabolism: a review with currently available evidence. Biomol Ther. (2022) 12:618. doi: 10.3390/biom12050618

83.

Ghimire R Limbu Y Parajuli A Maharjan DK Thapa PB . Indications and outcome of surgical Management of Local Complications of acute pancreatitis: a single-Centre experience. Int Surg J. (2021) 8:3238–42. doi: 10.18203/2349-2902.isj20214358

84.

Hart PA Bradley D Conwell DL Dungan K Krishna SG Wyne K et al . Diabetes following acute pancreatitis. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. (2021) 6:668–75. doi: 10.1016/s2468-1253(21)00019-4

85.

Purcell AW Sechi S DiLorenzo TP . The evolving landscape of autoantigen discovery and characterization in type 1 diabetes. Diabetes. (2019) 68:879–86. doi: 10.2337/dbi18-0066

86.

Rao SA Kunte AR . Interleukin-6: an early predictive marker for severity of acute pancreatitis. Ind J Critic Care Med. (2017) 21:424–8. doi: 10.4103/ijccm.IJCCM_478_16

87.

Huang W Booth DM Cane MC Chvanov M Javed MA Elliott VL et al . Fatty acid ethyl Ester synthase inhibition ameliorates ethanol-induced Ca2+-dependent mitochondrial dysfunction and acute pancreatitis. Gut. (2014) 63:1313–24. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2012-304058

88.

Lenzen S . Chemistry and biology of reactive species with special reference to the Antioxidative Defence status in pancreatic Β-cells. Biochim Biophys Acta Gen Subj. (2017) 1861:1929–42. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagen.2017.05.013

89.

Beshara A Cohen E Goldberg E Lilos P Garty M Krause I . Triglyceride levels and risk of type 2 diabetes mellitus: a longitudinal large study. J Investig Med. (2016) 64:383–7. doi: 10.1136/jim-2015-000025

90.

Szentesi A Párniczky A Vincze Á Bajor J Gódi S Sarlós P et al . Multiple hits in acute pancreatitis: components of metabolic syndrome synergize each Other's deteriorating effects. Front Physiol. (2019) 10:1202. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2019.01202

91.

Bálint ER Fűr G Kiss L Németh DI Soós A Hegyi P et al . Assessment of the course of acute pancreatitis in the light of Aetiology: a systematic review and Meta-analysis. Sci Rep. (2020) 10:17936. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-74943-8

92.

Barreto SG Habtezion A Gukovskaya A Lugea A Jeon C Yadav D et al . Critical thresholds: key to unlocking the door to the prevention and specific treatments for acute pancreatitis. Gut. (2021) 70:194–203. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2020-322163

93.

Sahin-Tóth M Hegyi P . Smoking and drinking synergize in pancreatitis: multiple hits on multiple targets. Gastroenterology. (2017) 153:1479–81. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2017.10.031

94.

Banks PA Freeman ML . Practice guidelines in acute pancreatitis. Am J Gastroenterol. (2006) 101:2379–400. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2006.00856.x

95.

Petrov MS Yadav D . Global epidemiology and holistic prevention of pancreatitis. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. (2019) 16:175–84. doi: 10.1038/s41575-018-0087-5

96.

Hegyi PJ Soós A Tóth E Ébert A Venglovecz V Márta K et al . Evidence for diagnosis of early chronic pancreatitis after three episodes of acute pancreatitis: a cross-sectional multicentre international study with experimental animal model. Sci Rep. (2021) 11:1367. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-80532-6

97.

Mosztbacher D Hanák L Farkas N Szentesi A Mikó A Bajor J et al . Hypertriglyceridemia-induced acute pancreatitis: a prospective, multicenter, international cohort analysis of 716 acute pancreatitis cases. Pancreatology. (2020) 20:608–16. doi: 10.1016/j.pan.2020.03.018

98.

Śliwińska-Mossoń M Bil-Lula I Marek G . The cause and effect relationship of diabetes after acute pancreatitis. Biomedicine. (2023) 11. doi: 10.3390/biomedicines11030667

99.

Petrov MS Basina M . Diagnosis of endocrine disease: diagnosing and classifying diabetes in diseases of the exocrine pancreas. Eur J Endocrinol. (2021) 184:R151–63. doi: 10.1530/EJE-20-0974

100.

Casu A Grippo PJ Wasserfall C Sun Z Linsley PS Hamerman JA et al . Evaluating the immunopathogenesis of diabetes after acute pancreatitis in the diabetes related to acute pancreatitis and its mechanisms study: from the type 1 diabetes in acute pancreatitis consortium. Pancreas. (2022) 51:580–5. doi: 10.1097/mpa.0000000000002076

101.

Dungan KM Hart PA Andersen DK Basina M Chinchilli VM Danielson KK et al . Assessing the pathophysiology of hyperglycemia in the diabetes related to acute pancreatitis and its mechanisms study: from the type 1 diabetes in acute pancreatitis consortium. Pancreas. (2022) 51:575–9. doi: 10.1097/mpa.0000000000002074

102.

Schrauben SJ Chen HY Lin E Jepson C Yang W Scialla JJ et al . Hospitalizations among adults with chronic kidney disease in the United States: a cohort study. PLoS Med. (2020) 17:e1003470. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1003470

103.

Hegyi P Petersen OH Holgate S Erőss B Garami A Szakács Z et al . Academia Europaea Position Paper on Translational Medicine: The Cycle Model for Translating Scientific Results into Community Benefits. J Clin Med. (2020) 9. doi: 10.3390/jcm9051532

104.

Hegyi P Erőss B Izbéki F Párniczky A Szentesi A . Accelerating the translational medicine cycle: the academia Europaea pilot. Nat Med. (2021) 27:1317–9. doi: 10.1038/s41591-021-01458-8

105.

Beazell JM Schmidt CR Ivy AC . The diagnosis and treatment of Achylia Pancreatica. J Am Med Assoc. (1941) 116:2735–9. doi: 10.1001/jama.1941.02820250001001

106.

Juhász MF Vereczkei Z Ocskay K Szakó L Farkas N Szakács Z et al . The effect of dietary fat content on the recurrence of pancreatitis (effort): protocol of a multicenter randomized controlled trial. Pancreatology. (2022) 22:51–7. doi: 10.1016/j.pan.2021.10.002

107.

Ocskay K Juhász MF Farkas N Zádori N Szakó L Szakács Z et al . Recurrent acute pancreatitis prevention by the elimination of alcohol and cigarette smoking (reappear): protocol of a randomised controlled trial and a cohort study. BMJ Open. (2022) 12:e050821. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2021-050821

Summary

Keywords

diabetes mellitus, prediabetes, acute pancreatitis (AP), pancreatitis—complications, gastrointestinal disorders, risk factor (RF)

Citation

Zahariev OJ, Bunduc S, Kovács A, Demeter D, Havelda L, Budai BC, Veres DS, Hosszúfalusi N, Erőss BM, Teutsch B, Juhász MF and Hegyi P (2024) Risk factors for diabetes mellitus after acute pancreatitis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Front. Med. 10:1257222. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2023.1257222

Received

12 July 2023

Accepted

12 December 2023

Published

09 January 2024

Volume

10 - 2023

Edited by

Michael Chvanov, University of Liverpool, United Kingdom

Reviewed by

Lu Ke, Nanjing University, China; Hanna Sternby, Lund University, Sweden

Updates

Copyright

© 2024 Zahariev, Bunduc, Kovács, Demeter, Havelda, Budai, Veres, Hosszúfalusi, Erőss, Teutsch, Juhász and Hegyi.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Péter Hegyi, hegyi2009@gmail.com

†These authors have contributed equally to this work and share last authorship

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.