Abstract

Introduction:

Immune thrombocytopenia (ITP) management with co-existing acute coronary syndrome (ACS) remains challenging as it requires a clinically relevant balance between the risk and outcomes of thrombosis and the risk of bleeding. However, the literature evaluating the treatment approaches in this high-risk population is scarce.

Methods and Results:

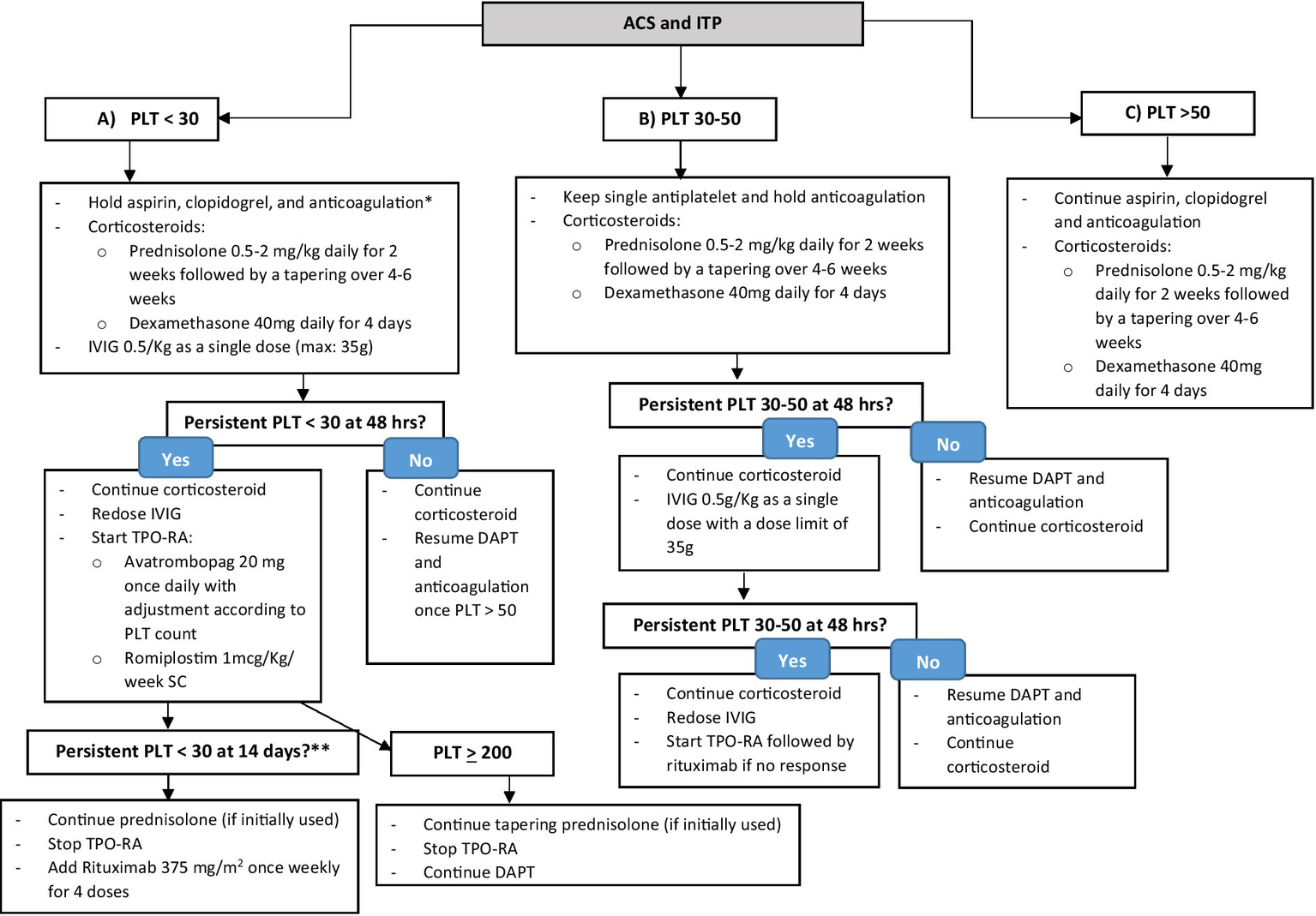

In this review, we aimed to summarize the available literature on the safety of ITP first- and second-line therapies to provide a practical guide on the management of ITP co-existing with ACS. We recommend holding antithrombotic therapy, including antiplatelet agents and anticoagulation, in severe thrombocytopenia with a platelet count < 30 × 109/L and using a single antiplatelet agent when the platelet count falls between 30 and 50 × 109/L. We provide a stepwise approach according to platelet count and response to initial therapy, starting with corticosteroids, with or without intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG) with a dose limit of 35 g, followed by thrombopoietin receptor agonists (TPO-RAs) to a target platelet count of 200 × 109/L and then rituximab.

Conclusion:

Our review may serve as a practical guide for clinicians in the management of ITP co-existing with ACS.

Introduction

Acute coronary syndrome (ACS) presents as unstable angina (UA), acute non-ST-elevation myocardial infarction (NSTEMI), or acute ST-elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI), which are considered cardiac emergencies, requiring prompt interventions, including the initiation of antithrombotic therapy with coronary angioplasty. Dual antiplatelet therapy (DAPT), including aspirin and a P2Y12 receptor inhibitor, is considered the cornerstone of ACS management as per the international clinical practice guidelines, including the American College of Cardiology Foundation (ACCF)/American Heart Association (AHA) and the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) (1, 2). Treatment with DAPT reduces the risk of both stent thrombosis and subsequent ischemic events; however, it increases the risk of bleeding (3, 4). Immune thrombocytopenia (ITP) is an acquired autoimmune disorder characterized by a low platelet count caused by platelet destruction along with impaired platelet synthesis. It is considered a rare hematological disorder with an estimated incidence in the general population of 2 to 5 per 100,000 persons (5).

The management of ITP co-existing with ACS is a challenging situation for healthcare providers, as this population is at a higher risk of bleeding and thrombosis (6). To minimize the risk of bleeding among patients with thrombocytopenia and co-existing ACS, McCarthy et al. proposed performing percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) through radial access if the platelet count >50 × 109/L without active bleeding and using drug-eluting stent (DES) instead of a bare-metal stent (BMS) with minimizing DAPT duration to 1 month followed by clopidogrel monotherapy thereafter (7). For ITP management, the American Society of Hematology (ASH) clinical practice guidelines recommend initial pharmacological treatment with corticosteroids with or without intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG) followed by second-line therapies, including thrombopoietin receptor agonists (TPO-RAs), rituximab, or splenectomy for non-responders or those dependent on corticosteroids with platelet counts < 30 × 109/L (5).

Nevertheless, corticosteroids are associated with an increased bleeding risk if used with DAPT and may worsen myocardial healing in ACS, and the remaining second-line ITP agents are associated with an increased risk of thrombosis (5, 8). Such considerations complicate the management of ITP co-existing with ACS. To the best of our knowledge, there are no current guideline recommendations or consensus reports to guide clinicians on the management of this high-risk cohort. In this review, we examined the evidence to date and provided our opinion on future directions and management strategies for ITP co-existing with ACS.

Search strategy

We searched PubMed and Embase databases for the studies published in English exploring the management of ITP co-existing with ACS. We used the following terms: “Immune Thrombocytopenia Purpura,” “Immune Thrombocytopenia,” “Acute Coronary Syndrome,” “Percutaneous Coronary Intervention,” “Coronary Artery Bypass Graft,” “corticosteroids,” “Intravenous immunoglobulin, “Thrombopoietin receptor agonists,” “eltrombopag,” “avatrombopag,” “romiplostim,” and “Rituximab.” “AND” and “OR” were used as Boolean operators to combine the terms. The literature search included all articles published until 5 October 2022. The reference lists of the retrieved articles were manually screened.

ITP pharmacological therapy

Corticosteroids

Corticosteroids are the recommended first-line treatment for newly diagnosed ITP in adult patients who require therapy, i.e., platelet count < 30 × 109/L or any platelet count with associated bleeding. In patients with a platelet count ≥ 30 × 109/L who require antiplatelet or anticoagulation therapy, corticosteroids may be considered (5). Corticosteroids are widely available at a low cost but are associated with significant multi-system side effects. Specifically, corticosteroids can precipitate or exacerbate classical risk factors of coronary artery disease (CAD), such as hypertension, impaired glucose tolerance, and hypercholesterolemia (5).

The ASH clinical practice guidelines for ITP management do not give preference to prednisolone over dexamethasone but highlight that platelet recovery at 7 days may be faster and more sustained with dexamethasone (5). A recent meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials by Xiao and colleagues supported this notion. Patients with newly diagnosed primary ITP who received high-dose dexamethasone had a significantly higher overall response than standard-dose prednisone. This was not associated with a significantly different incidence of side effects, including arthralgia, elevated blood pressure, hyperglycemia, or mood disorders (9).

ACS is a proinflammatory, prothrombotic state. Corticosteroids have long been hypothesized to be beneficial for patients with acute myocardial infarction (AMI) (10). However, concerns for corticosteroid effects on wound healing, myocardial wall thinning, and potential myocardial rupture make them unfavorable agents in the setting of ACS. Moreover, acute and chronic corticosteroid use has been reported to increase the risk of myocardial infarction (MI), not necessarily in the presence of conventional risk factors for CAD (11). Proposed mechanisms include an increase in clotting factor production and inducing coronary vasospasm (12–14). Interestingly, it has been shown that corticosteroids may result in a 26% mortality benefit in AMI without a clear association with myocardial rupture (8). Notably, many of the studies included in this analysis were before the advent of the current standard medical treatment in ACS and, more importantly, before the widespread availability of PCI.

The comparative safety of different corticosteroids in patients with concomitant newly diagnosed ITP and ACS is based on observational data. Larger doses (i.e., a daily dose of prednisolone equivalent to more than 10 mg), as well as longer duration of therapy, especially in the first 30 days of use, may confer a higher risk (15, 16). Hence, it can be inferred that prednisone may be safer than dexamethasone in this population, as it is used at a lower dose. Nevertheless, an important caveat is that patients with ACS require DAPT and anticoagulation, increasing the risk of bleeding in the setting of ITP. Consequently, faster platelet recovery is a priority, and this may be better achieved with dexamethasone (9). Each corticosteroid carries an important advantage; dexamethasone helps achieve faster platelet recovery, facilitating earlier use of antithrombotic therapy for ACS but might increase the risk of MI as larger doses are needed, while prednisolone might be a safer option but could result in late platelet recovery, which could delay antithrombotic therapy for ACS. Therefore, the treating clinician may choose the agent that best aligns with the patient’s profile, considering the risk stratification of ACS, the urgency of coronary angiography, and PCI, bleeding, and thromboembolic risks.

The standard high-dose dexamethasone regimen to treat ITP is 40 mg per day for 4 days. Prednisone is given at a dose of 0.5–2 mg/kg daily for 2 weeks followed by a tapering regimen (5, 17). Current evidence suggests that prednisolone equivalent doses as low as 7.5 mg daily were found to increase the risk of cardiovascular complications including AMI (15, 16). In the setting of ITP with ACS, we recommend using the lowest effective dose of prednisolone or a short course of high-dose dexamethasone under close monitoring for platelet response and the occurrence of new thromboembolic events.

Intravenous immunoglobulin

IVIG is considered one of the first lines of managing adults diagnosed with ITP. It is usually given if a faster platelet recovery is required, in cases of poor response to corticosteroids, concurrent contraindications to steroids, in the presence of active bleeding, or a high risk of bleeding (17, 18). It has been demonstrated that the concurrent use of corticosteroids and IVIG results in a shorter duration of complete remission and an overall response, without significant difference in adverse reactions (19, 20). In ITP, it can be administered at an initial dose of 1 g/kg as a one-time dose or 0.4 g/kg per day for 5 days and might be repeated if the response is suboptimal (17). IVIG has been shown to increase the likelihood of venous and arterial thromboembolic events (TEE). The first association of IVIG administration with thrombotic events was reported in 1986 when two patients had MI and two patients had a stroke after the infusion (21). The incidence of IVIG-induced thrombosis is estimated to be 1–16.9% as demonstrated in two retrospective studies with MI and stroke as the predominant arterial thrombotic events (22, 23). Cardiovascular events following immunoglobulin therapy have always been a challenge as the medical conditions managed with IVIG may contribute to ACS. Consequently, in 2013, the FDA mandated that a black box warning of increased risk of thrombosis be included on IVIG products (24).

We have identified a total of 16 cases of IVIG-induced MI as demonstrated in Table 1 (25–37). Certain risk factors were found to increase the risk of thrombosis with the use of IVIG infusion, including previous history of atherosclerotic diseases, thrombosis, concurrent hypercoagulable status, age of more than 45 years, and an IVIG daily dose of more than 35 g (38). Moreover, patients with ITP were found to have a higher incidence of thrombosis upon receiving IVIG than other pathological conditions treated with IVIG (38, 39). Taking all of the previous information into consideration, in the setting of ITP with ACS, we recommend using IVIG with corticosteroids among patients with profound thrombocytopenia, e.g., platelet count < 30 × 109/L, or refractory thrombocytopenia despite corticosteroids, with a daily dose capping of 35 g (e.g., 0.5 g/Kg).

Table 1

| Author, Year | Age and sex | IVIG dose | Indication | Cardiac risk factors | Type and time to MI (From 1st dose of IVIG) | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tan, 2008 | 23, Female | 60 g for 2 doses | Thrombocytopenia in the setting of concurrent SLE and aPL | None | STEMI (LAD), 14 days | Survival |

| Elkayam, 2000 | 60, Male | 660 mg/kg/day infusion for 3 days | Relapsing polychondritis | Hypertension | NSTEMI (thrombolytic therapy), 10 days | Survival |

| 41, Female | 1 g/kg/day infusion for 2 days every month for 12 months (uneventful) then 2nd cycle due to relapse | Anti-Jo1 positive polymyositis with progressive interstitial lung disease | FHx of CAD, steroid-related adverse effects after the 2nd cycle (marked obesity, hypertension, diabetes mellitus requiring insulin) | STEMI, 6 days after the 3rd dose of the 2nd cycle of IVIG | Survival | |

| 67, Male | 400 mg/kg/day for 5 days | Chronic inflammatory demyelinating polyneuropathy | Hypercholesterolemia | Non-Q wave MI (LAD), few hours after 1st infusion | Survival (IVIG treatment was renewed without further complication after PTCA treatment for the NSTEMI) | |

| 67, Male | 400 mg/kg/months for 5 days every month | Systemic castleman disease | None | Inferior MI, day 4 of the 5th IVIG course | Survival | |

| Eliasberg, 2007 | 43, Male | 400 mg/kg (one dose for thrombocytopenia prior to CAG) | Antiphospholipid syndrome with steroid-dependent thrombocytopenia | Obesity, a positive family history of CAD, and a smoking habit (50 pack years of cigarettes), anterior NSTEMI 1 week prior to IVIG (he did not receive antiplatelet or anticoagulant therapy but rather was treated with nitrates and beta blockers alone) | Anterior STEMI (MI reinfarction), 1 h after initiation of IVIG infusion | Survival (CAG was canceled due to thrombocytopenia of 29,000, no antiplatelet or anticoagulant) |

| Paolini, 2000 | 78, Female | 400 mg/kg daily (30 g) for 5 days | ITP | Severe hypertension, angina | Anteroseptal MI, 1 day after completion | -- |

| Stamboulis, 2004 | 39, Male | 0.5 g/kg/day for 5 days | Chronic Inflammatory Demyelinating Polyneuropathy in Association with a Monoclonal Immunoglobulin G Paraprotein | Heavy smoker | MI (CAG no lesion, mild anterior dyskinesia), 6 weeks after IVIG | -- |

| Barsheshet, 2007 | 72, Male | 0.4 g/kg per day for 5 days (32 g) | GBS | hypertension, hypercholesterolemia, IHD with PTCA, and stent implantation to LAD on account of stable angina pectoris 9 years ago | STEMI (CABG), 3 h following the start of infusion | -- |

| Vinod, 2014 | 69, Male | 0.4 g/kg/day × 5 days | GBS | None | Anterior STEMI (thrombolytics), when the last dose of IVIG was just about to be completed | Survival |

| Stenton, 2005 | 81, Male | IVIG 0.5 g/kg daily (38 g) | toxic epidermal necrolysis secondary to allopurinol | hypertension, angina, hypercholesterolemia, type 2 diabetes, chronic renal failure | NSTEMI, 30 min following the start of the IVIG infusion | Survival |

| Davé, 2007 | 65, Male | treated for 6 years with monthly IVIG [Polygam] without complications. 400 mg/kg (40 g) [Gammagard] tried for the 1st time | CVID | History of CAD and CABG before the diagnosis of CVID, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, and diet-controlled type 2 diabetes Mellitus, chronic stable angina with exercise 1 week prior to the Gammagard infusion | NSTEMI (repeat CABG), toward the end of the infusion of Gammagard | Survival |

| Mizrahi, 2009 | 76, Female | IVIG 2 mg/kg every month | Myasthenia gravis | None | NSTEMI (refused CAG), 2 h after IVIG (first day of her 3rd cycle) | Survival |

| Vucic, 2004 | 80, Female | 0.6 g mg/kg every month | CIDP | None | STEMI (RCA), 336 h (received 52 IVIG treatments before this event) | -- |

| Hefer, 2004 | 82, Male | 37.5 g of IVIG (day 1 of admission), total of 65 g received by day 2 before the event | CML with refractory ITP | Hypertension | STEMI (no CAG), 3 h after finishing the infusion of IVIg | Survival |

| Zaidan, 2003 | 47, Male | 0.25 g/kg/day |q4hr| increased after day 2 to 0.4 g/kg/day | GBS | Smoker, familial hypercholesterolemia, STEMI 3 weeks earlier | Inferior STEMI, during the 3rd dose | Survival |

Case reports of IVIG-induced myocardial infarction.

Thrombopoietin receptor agonists

Currently, there are five commercially available TPO-RAs, including eltrombopag, avatrombopag, lusutrombopag, romiplostim, and recombinant human thrombopoietin (rhTPO). Eltrombopag is an oral, small, non-peptide molecule that initiates thrombopoietin receptor signaling, thereby inducing cell proliferation, differentiation, and maturation in the megakaryocytic lineage (40). Avatrombopag is a small-molecule TPO-RA that mimics the biological effects of endogenous TPO on platelet production. It was approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in 2018, for treating thrombocytopenic disorders including ITP and chronic liver disease-induced thrombocytopenia (41). Lusutrombopag is a chemically synthesized orally active small-molecule TPO-RA that activates the signal transduction pathway in the same manner as endogenous TPO, thereby upregulating platelet production. It was approved in Japan in 2015 for use in patients with thrombocytopenia and chronic liver disease who are undergoing invasive procedures, and it is FDA-approved for liver disease-associated thrombocytopenia but not yet approved for ITP (42). Romiplostim is a novel peptide molecule that stimulates the megakaryocytopoiesis and increases the platelet count in the same manner as TPO (43). RhTPO is a glycosylated TPO that was approved in China as a second-line option for ITP (44).

According to the latest ASH guidelines for ITP management, the first-line therapy for newly diagnosed ITP is a short course of corticosteroids. For individuals with ITP ≥3 months who depend on corticosteroids or respond poorly to corticosteroids, the ASH guidelines suggest using second-line therapies, including TPO-RAs (once-daily oral eltrombopag or once-weekly subcutaneous injection romiplostim), rituximab, or splenectomy after appropriate immunizations (5). A recently published meta-analysis of 20 randomized controlled trials comprising 2,207 patients with ITP demonstrated that avatrombopag, lusutrombopag, eltrombopag, and romiplostim demonstrated a significantly better platelet response defined as platelet counts ≥ 30 or 50 × 109/L during the treatment period compared with placebo (OR 36.90, 95%CI 13.33–102.16; OR 19.33, 95%CI 8.42–44.40; OR 11.92, 95%CI 7.43–19.14; OR 3.71, 95%CI 1.27–10.86, respectively) (45).

Because of the higher incidence of thrombosis in patients with ITP than in the healthy population, it was recognized as a unique complication of ITP (46). However, the pathogenic mechanisms responsible for the increased thrombotic risk associated with TPO-RAs have not yet been identified (47). The excessive increase in platelet count among patients treated with TPO-RAs, and the production of immature, more active platelets may partially explain the reason for high risk of thrombosis (48). Interestingly, an excessive increase in platelet count to 200 × 109/L was associated with an increased risk of thrombosis within a median time of 21.5 days (range, 15 to 53) from the first dose of eltrombopag in a randomized controlled trial of eltrombopag use (49). In a meta-analysis of 2,207 patients receiving TPO-RAs for ITP, there were no significant differences between the TPO-RAs and placebo in terms of thrombosis (45). However, using surface under the cumulative ranking curve (SUCRA), with a larger SUCRA indicating a higher incidence of the outcome, the combination of rhTPO and rituximab had the highest SUCRA value for thrombosis of 74.3, followed by rituximab of 71.7 alone, and then the remaining TPO-RAs (45).

As demonstrated in Table 2 of studies evaluating the efficacy and safety of TPO-RAs, there was no dose-dependent thrombotic risk with TPO-RA use. Additionally, arterial thrombosis in the form of ACS was rare (49–63). Thus, TPO-RAs for ITP in the setting of ACS might be used at the regular dosing regimens for ITP. Nevertheless, eltrombopag undergoes extensive hepatic metabolism, and thus, its use with a high-intensity statin (atorvastatin and rosuvastatin) alters the elimination of statin therapy through the inhibition of OATP1B1 transporters, requiring lower doses of statin and frequent monitoring for statin-induced hepatotoxicity and myopathy (64). Therefore, eltrombopag might be the least favorable oral TPO-RA in ACS.

Table 2

| Study ID | Intervention and control | TPO-RA dose | Duration | Thrombotic events | Time to thrombosis | PLT count at time of thrombosis |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Afdhal, 2012 | Eltrombopag vs. placebo | Eltrombopag 75 mg | 14 days | TPO-RA: 6 PVT§ Placebo: 1 MI, 1 PVT |

TPO-RA: 1–38 days | TPO-RA: 33–417 × 109/L |

| Placebo: 20–128 days | Placebo: 83 × 109/L | |||||

| Hidaka, 2019 | Lusutrombopag vs. placebo | Lusutrombopag 3 mg daily | 7 days | TPO-RA: 1 PVT | TPO-RA: 14 days | TPO-RA: 70 × 109/L |

| Placebo: 1 superior mesenteric vein thrombosis | Placebo: 20 days | Placebo: 60 × 109/L | ||||

| Tateishi, 2019 | Lusutrombopag vs. placebo | Lusutrombopag 2 mg, 3 mg, 4 mg | 7 days | Lusutrombopag 2 mg: 1 PVT | - | TPO-RA: 37–91 × 109/L |

| Lusutrombopag 3 mg: none | ||||||

| Lusutrombopag 4 mg: 2 VTE (1 PVT, mesenteric vein thrombosis) | ||||||

| Placebo: 1 mesenteric vein thrombosis | Placebo: - | |||||

| Peck-Radosavljevic, 2019 | Lusutrombopag vs. placebo | Lusutrombopag 3 mg daily | 7 days | TPO-RA: 2 (1 left intrahepatic artery thrombosis, 1 left ventricular thrombus*) | - | TPO-RA: 62 and 119 × 109/L |

| Placebo: 2 splanchnic thrombosis | Placebo: - | |||||

| Terrault, 2018 | Avatrombopag vs. placebo | Avatrombopag 60 mg ➔ PLT < 40 | 5 days | TPO-RA: 1 PVT | TPO-RA: 18 days | TPO-RA: 61 × 109/L |

| Avatrombopag 40 mg ➔ PLT < 50 | Placebo: 2 (1 MI, 1 PE) | Placebo: - | Placebo: - | |||

| Jurczak, 2018 | Avatrombopag vs. placebo | Avatrombopag 5-40 mg | 6 months | TPO-RA: 4 (1 DVT, 1 PE, 1 CVA, 1 jugular vein thrombosis) | TPO-RA: 8–335 days | TPO-RA: 39–271 × 109/L |

| Placebo: 0 | ||||||

| Kuter, 2018 | Avatrombopag vs. placebo | Avatrombopag up to 100 mg daily | 14 days | TPO-RA: 0 | NA | NA |

| Placebo: 0 | ||||||

| Bussel, 2014 | Avatrombopag vs. placebo | Avatrombopag 2.5-20 mg | 28 days | TPO-RA: 5 (1 DVT, 1 MI**, 1 retinal artery occlusion, 1 superficial thrombophlebitis, 1 stroke) | TPO-RA: - | TPO-RA: 19–571 × 109/L |

| Placebo: 0 | ||||||

| Cheng, 2011 | Eltrombopag vs. placebo | Eltrombopag 50 mg | 6 months | TPO-RA: 2 PE***, 1 DVT*** | TPO-RA: 5–6 days | TPO-RA: 42–49 × 109/L |

| Placebo: 0 | ||||||

| Yang, 2016 | Eltrombopag vs. placebo | Eltrombopag 25–75 mg | 8 weeks | TPO-RA: 1 DVT | - | - |

| Placebo: 0 | ||||||

| Bussel, 2009 | Eltrombopag vs. placebo | Eltrombopag 50–75 mg | 6 weeks | TPO-RA: 0 | NA | NA |

| Placebo: 0 | ||||||

| Tomiyama, 2012 | Eltrombopag vs. placebo | Eltrombopag 12.5–50 mg | 6 weeks | TPO-RA: 1 TIA | TPO-RA: 8 days | TPO-RA: 76 × 109/L |

| Placebo: 0 | ||||||

| Bussel, 2006 | Romiplostim vs. placebo | Romiplostim 1, 3, or 6 μg/Kg SC weekly | 6 weeks | TPO-RA: 0 | - | - |

| Placebo: 1 DVT | ||||||

| Kuter, 2008 | Romiplostim vs. placebo | Romiplostim 1–15 μg/Kg SC weekly | 24 weeks | TPO-RA: 1 popliteal artery thrombosis, 1 CVA | TPO-RA: 147–224 days | TPO-RA: 11–107 × 109/L |

| Placebo: 1 PE | ||||||

| Shirasugi, 2011 | Romiplostim vs. placebo | Romiplostim 3 μg/Kg SC weekly | 12 weeks | TPO-RA: 0 | NA | NA |

| Placebo: 0 |

Literature evaluating the safety of TPO-RA use.

*Had history of CAD and LVT; **Had significant CV history with CABG and TIAs; ***Had risk factors for thrombosis; §five out of six events occurred when PLT > 200, and events after within a median of 8 days after last dose of therapy; PVT: portal vein thrombosis.

ITP management in the setting of ACS remains uncertain and challenging in view of the need for a balanced regimen between bleeding and thrombosis risk. Among patients with treatment-naive ITP and concurrent ACS who are either corticosteroid-dependent or corticosteroid-poor responders, we suggest using TPO-RA (avatrombopag, or once weekly subcutaneous injection romiplostim) as a second-line ITP therapy to target platelet count > 50 × 109/L, permitting the use of DAPT, to a maximum platelet count of 200 × 109/L to reduce the risk of TPO-RA-associated thrombosis. We recommend against using a combination therapy of TPO-RA and rituximab to reduce the risk of thrombosis.

Rituximab

Rituximab is another frequently used second-line treatment modality in ITP. The mechanism of action responsible for its efficacy is not fully understood (65). Rituximab is an anti-CD20 monoclonal antibody that targets B cells. It was proposed that B-cell destruction will result in the underproduction of antibodies, hence the therapeutic benefits of ITP (66). However, more recent evidence showed that the rituximab effect is more complicated than we thought and it extends to involve the T cells. It was found that rituximab neutralizes the auto-reactive T cells and patients who responded to the therapy demonstrated normalization of the T-cell abnormalities (67–69). It is proposed that B cells might play a role in keeping the T cells active and targeting the T cells indirectly is the main drive behind the successful use of rituximab in ITP patients (65).

According to the most recent ASH guidelines for ITP management, rituximab is not the initial therapy of choice (5). However, it can be used as add-on therapy to corticosteroids if more emphasis is placed on achieving remission while accepting the potential side effects. Rituximab is one of the second-line options, in addition to TPO-RAs and splenectomy, in patients who are corticosteroid-dependent for 3 months or more or who showed no response to corticosteroids (5).

There are several case reports of the development of ACS, mostly STEMI, following rituximab infusion that was used for different medical conditions as shown in Table 3 (70–79). More than half the events occurred after the first dose of rituximab. Unfortunately, the exact doses of rituximab were not reported in most cases. It is worth mentioning that almost all reported cases of MI occurred during rituximab infusion or just a few hours afterward. There was only one reported case of delayed MI occurring within 24 h after the infusion and that is the only case in which the indication for rituximab was the treatment of ITP, which raises questions about whether the event was related to rituximab (77). To the best of our knowledge, there are no other reported cases of ACS in ITP patients following rituximab infusion. Zhou et al. compared rituximab plus recombinant human thrombopoietin (rhTPO) vs. rituximab alone for corticosteroid-resistant or relapsed ITP in a randomized controlled trial, and they found that only one patient died from MI out of the 77 participants in the rituximab plus rhTPO group (44). The patient was 77 years old with known cardiac risk factors and was labeled as a non-responder after 8 months of treatment. No deaths or cardiac events were reported in the rituximab monotherapy group. In another study, two out of 55 patients on rituximab developed venous thromboembolic events (VTE); one pulmonary embolism and one deep venous thrombosis; however, no cardiac events were recorded (80). A recent study in 2019 investigated the risk of thromboembolism of rituximab by looking into the adverse events reported from two randomized clinical trials (81). It was noted that the rate of VTE was higher in ITP patients treated with rituximab; however, the authors could not conclude whether these events were triggered by rituximab or caused by other confounding factors.

Table 3

| Study | Age and sex | Rituximab dose | Indication | Cardiac risk factors | Type and time to MI | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Armitage, 2008 | 58, Male | First | CLL | Previous MI | Two have MI during the infusion (one of them was with a test dose of 25 mg) and the third at the completion of infusion | Survival |

| 61, Male | BL | +Risk factors | Survival | |||

| 72, Male | BLL | +Risk factors | Death | |||

| Arunprasath, 2011 | 60, Male | First | DLBCL | Diabetes | AWMI, 15 min after starting the infusion | Survival |

| Renard, 2013 | 52, Male | Third, 375 mg/m2 | MG | None | IWMI, 10 h after the infusion | Survival |

| Gogia, 2014 | 65, Male | First | SLVL | None | IWMI, after 5 min of starting the infusion | Survival |

| Van Sijl, 2014 | 70, Female | First and second | RA | Previous history of MI | ALWMI | Survival |

| 76, Female | Second | RA | None | AWMI | Survival | |

| Keswani, 2015 | 46, Male | Second | DLBCL | Smoking: 25 pack-years | IWMI, halfway through the infusion | Survival |

| Verma, 2016 | 62, Male | First | NHL | None | IWMI, after 5 min of starting the infusion | Survival |

| Mehrpooya, 2016 | 52, Female | First dose, 375 mg/m2 | ITP | HTN, mild CAD | IWMI, 24 h | Survival |

| Arenja, 2016 | 36, Male | Not specified | PR3-ANCA-positive granulomatosis with polyangiitis | Smoking: 20 pack-years, HTN, hypercholesterolaemia | AWMI | Survival |

| Sharif, 2017 | 58, Male | Fifth dose of 1,000 mg | RA + Scleroderma | HTN, smoking: 30 pack-years | AWMI, during infusion | Survival |

Case reports of Rituximab-induced myocardial infarction.

Among patients with ITP and concurrent ACS who are either corticosteroid-dependent or poor responders, we recommend using rituximab without combining it with TPO-RA due to the increased risk of MI.

General approach to ITP management with co-existing ACS

ITP with platelet count < 30 × 109/L

The management of patients with severe thrombocytopenia in the setting of ITP with concurrent ACS is challenging and requires an individualized approach based on the anticipated short- and long-term prognosis of the thrombotic event in case of delayed intervention vs. the risk of bleeding resulting from antithrombotic therapy, taking into consideration patient’s age, refractoriness of ITP, and concurrent comorbidities. The evaluation of such a patient requires a multidisciplinary team approach. We advise holding antithrombotic therapy, including DAPT and anticoagulation, until platelet count is >30–50 × 109/L after evaluating the risks and benefits in a multidisciplinary team to individualize the management, along with starting the first-line ITP treatment with corticosteroids, either low-dose prednisolone or short course of high-dose dexamethasone plus IVIG with dose limit of 35 g (e.g., 0.5 g/Kg) daily, as demonstrated in Figure 1. In case of an increase in platelet count within 48 h of initial treatment, we advise continuing corticosteroids; prednisolone with a tapering schedule over 4–6 weeks or dexamethasone for a total of 4 days, and resuming antithrombotic therapy once platelet count > 50 × 109/L. Among P2Y12 inhibitors, we prefer clopidogrel over ticagrelor and prasugrel in view of its lower risk of bleeding (82, 83). In case of persistent platelet count < 30 × 109/L within 48 h of initial therapy, in addition to corticosteroids, we recommend re-dosing IVIG with dose capping of 35 g along with starting a TPO-RA, including avatrombopag or romiplostim to a target platelet count of 200 × 109/L. We advise against using eltrombopag in the setting of ACS in view of drug–drug interaction with high-intensity statin therapy that is recommended in ACS, warranting dose reduction of statin therapy and close monitoring of liver enzymes and myopathy (64). In case of persistently severe thrombocytopenia within 14 days of TPO-RA, switching to TPO-RA is recommended. Rituximab 375 mg/m2 once weekly for four doses might be added. We advise against combining TPO-RA and rituximab therapy in view of the increased risk of thrombotic events (44, 45). In case of refractory thrombocytopenia despite IVIG, corticosteroids, TPO-RAs, and rituximab, the use of fostamatinib, which is a tyrosine kinase inhibitor recently approved in 2018 by the FDA for the treatment of chronic ITP unresponsive to previous therapies, might be considered (84). However, the thrombotic risk of fostamatinib has not yet been well evaluated (85). In cases of active bleeding, platelet transfusion can be considered, yet its role in ITP remains controversial (86).

Figure 1

Stepwise approach of the management of ITP co-existing with ACS. *After a multidisciplinary team evaluation of the case to assess risks and benefits. **To consider fostamatinib in refractory ITP despite TPO-RA and rituximab.

ITP with platelet count 30–50 × 109/L

Among patients with a platelet count of 30–50 × 109/L due to ITP co-existing with ACS, we advise considering only a single antiplatelet, either aspirin or clopidogrel, holding anticoagulation for ACS, and starting prednisolone or dexamethasone for ITP, as shown in Figure 1. Within 48 h of therapy initiation, we advise to resume DAPT and parenteral anticoagulation, preferably a short-acting agent (i.e., unfractionated heparin) (87) in case of platelet count improvement to >50 × 109/L. In case of persistent thrombocytopenia with platelet count of 30–50 × 109/L, we recommend starting IVIG with a dose capping of 35 g while continuing the initial corticosteroid regimen. In the next 48 h, in case of no improvement in platelet count, we advise re-dosing IVIG and starting a TPO-RA, followed by rituximab if there is no response, as demonstrated in Figure 1.

ITP with a platelet count of >50 × 109/L

In the least severe form of ITP with a platelet count of >50 × 109/L with co-existing ACS, we recommend continuing all antithrombotic therapies for ACS, including DAPT and parenteral anticoagulation, and starting corticosteroids for ITP as shown in Figure 1.

Conclusion

ITP management with co-existing ACS is a growing dilemma as a clinically relevant balance between thrombosis and risk of bleeding needs to be achieved, especially since corticosteroids, the cornerstone therapy in ITP, might increase the risk of bleeding once combined with antithrombotic therapy in ACS, and the second-line agents in ITP might increase the risk of venous and arterial thrombosis. The literature evaluating the treatment approaches and outcomes in this high-risk population is scarce. Therefore, in this review, we attempted to summarize the available evidence on the safety of ITP therapies and provide a practical guide on the management of ITP co-existing with ACS. In general, we advise holding antithrombotic therapy in cases of severe thrombocytopenia with a platelet count < 30 × 109/L after evaluating the risks and benefits in a multidisciplinary team, and then using a single antiplatelet agent if the platelet count falls between 30 and 50 × 109/L. DAPT along with anticoagulation should be continued if the platelet count is >50 × 109/L. We provide a stepwise approach to the management of ITP according to platelet count and response to initial therapy, starting with corticosteroids plus-minus IVIG with dosing capping. This can be followed by TPO-RAs to achieve a target platelet count of 200 × 109/L. Finally, rituximab without combining it with TPO-RA to reduce the risk of thrombosis can be considered. Future studies are needed to evaluate the safety and effectiveness of the stepwise approach in the treatment of ITP co-existing with ACS.

Statements

Author contributions

AR: Conceptualization, Data curation, Methodology, Resources, Software, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. DP: Conceptualization, Methodology, Validation, Writing – review & editing. WG: Conceptualization, Validation, Writing – review & editing. TJG-L: Conceptualization, Validation, Writing – review & editing. KS: Data curation, Writing – original draft. MN: Data curation, Writing – original draft. AAh: Data curation, Writing – original draft. WR: Data curation, Writing – original draft. AAr: Conceptualization, Resources, Validation, Writing – review & editing. MY: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Methodology, Resources, Supervision, Validation, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. Authors received fund for publication from Sobi pharmaceutical without interference with the content.

Conflict of interest

WG reports fees for participation in the Advisory board from Amgen, Novartis, Pfizer, Principia Biopharma Inc-a Sanofi Company, Sanofi, SOBI, Grifols, UCB, Argenx, Cellphire, Alpine, Kedrion, Hi-Bio, and HUTCHMED. Lecture honoraria from Amgen, Novartis, Pfizer, Bristol Myers Squibb, SOBI, Grifols, Sanofi, and Bayer. Research grants from Bayer, BMS/Pfizer, and UCB. AR, KS, AAr, and MY were employed by Hamad Medical Corporation. TJG-L has received research grants from Amgen and Novartis and speaker honoraria from Amgen, Novartis, Sobi, Grifols and Argenx.

The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1.

Levine GN Bates ER Bittl JA Brindis RG Fihn SD Fleisher LA et al . ACC/AHA guideline focused update on duration of dual antiplatelet therapy in patients with coronary artery disease: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association task force on clinical practice guidelines. Circulation. (2016) 134:e123. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000404

2.

Ibanez B James S Agewall S Antunes MJ Bucciarelli-Ducci C Bueno H et al . 2017 ESC guidelines for the management of acute myocardial infarction in patients presenting with ST-segment elevation. Eur Heart J. (2018) 39:119–77. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehx393

3.

Bhatt DL Hulot JS Moliterno DJ Harrington RA . Antiplatelet and anticoagulation therapy for acute coronary syndromes. Circ Res. (2014) 114:1929–43. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.114.302737

4.

Udell JA Bonaca MP Collet JP Lincoff AM Kereiakes DJ Costa F et al . Long-term dual antiplatelet therapy for secondary prevention of cardiovascular events in the subgroup of patients with previous myocardial infarction: a collaborative meta-analysis of randomized trials. Eur Heart J. (2016) 37:390–9. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehv443

5.

Neunert C Terrell DR Arnold DM Buchanan G Cines DB Cooper N et al . American Society of Hematology 2019 guidelines for immune thrombocytopenia. Blood Adv. (2019) 3:3829–66. doi: 10.1182/bloodadvances.2019000966

6.

McClure MW Berkowitz SD Sparapani R Tuttle R Kleiman NS Berdan LG et al . Clinical significance of thrombocytopenia during a non–ST-elevation acute coronary syndrome. Circulation. (1999) 99:2892–900. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.99.22.2892

7.

McCarthy CP Steg GP Bhatt DL . The management of antiplatelet therapy in acute coronary syndrome patients with thrombocytopenia: a clinical conundrum. Eur Heart J. (2017) 38:3488–92. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehx531

8.

Giugliano GR Giugliano RP Gibson CM Kuntz RE . Meta-analysis of corticosteroid treatment in acute myocardial infarction. Am J Cardiol. (2003) 91:1055–9. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9149(03)00148-6

9.

Xiao Q Lin B Wang H Zhan W Chen P . The efficacy of high-dose dexamethasone vs. other treatments for newly diagnosed immune thrombocytopenia: a meta-analysis. Front Med. (2021) 8:56792. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2021.656792

10.

Bush CA Renner W Boudoulas H . Corticosteroids in acute myocardial infarction. Angiology. (1980) 31:710–4. doi: 10.1177/000331978003101007

11.

Shokr M Rashed A Lata K Kondur A . Dexamethasone associated ST elevation myocardial infarction four days after an unremarkable coronary angiogram—another reason for cautious use of steroids: a case report and review of the literature. Case Rep Cardiol. (2016) 2016:1–6. doi: 10.1155/2016/4970858

12.

Jilma B Cvitko T Winter-Fabry A Petroczi K Quehenberger P Blann AD . High dose dexamethasone increases circulating P-selectin and von Willebrand factor levels in healthy men. Thromb Haemost. (2005) 94:797–801. doi: 10.1160/T04-10-0652

13.

Brotman DJ Girod JP Posch A Jani JT Patel JV Gupta M et al . Effects of short-term glucocorticoids on hemostatic factors in healthy volunteers. Thromb Res. (2006) 118:247–52. doi: 10.1016/j.thromres.2005.06.006

14.

Okumura W Nakajima M Tateno R Fukuda N Kurabayashi M . Three cases of vasospastic angina that developed following the initiation of corticosteroid therapy. Intern Med. (2014) 53:221–5. doi: 10.2169/internalmedicine.53.1008

15.

Wei L MacDonald TM Walker BR . Taking glucocorticoids by prescription is associated with subsequent cardiovascular disease. Ann Intern Med. (2004) 141:764–70. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-141-10-200411160-00007

16.

Varas-Lorenzo C Rodriguez LAG Maguire A Castellsague J Perez-Gutthann S . Use of oral corticosteroids and the risk of acute myocardial infarction. Atherosclerosis. (2007) 192:376–83. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2006.05.019

17.

Provan D Arnold DM Bussel JB Chong BH Cooper N Gernsheimer T et al . Updated international consensus report on the investigation and management of primary immune thrombocytopenia. Blood Adv. (2019) 3:3780–817. doi: 10.1182/bloodadvances.2019000812

18.

Neunert C Lim W Crowther MA Cohen A Solberg L . The American Society of Hematology 2011 evidence-based practice guideline for immune thrombocytopenia. Blood. (2011) 117:4190–207. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-08-302984

19.

Sun D Shehata N Ye XY Gregorovich S de France B Arnold DM et al . Corticosteroids compared with intravenous immunoglobulin for the treatment of immune thrombocytopenia in pregnancy. Blood. (2016) 128:1329–35. doi: 10.1182/blood-2016-04-710285

20.

Wang X Xu Y Gui W Hui F Liao H . Retrospective analysis of different regimens for Chinese adults with severe newly diagnosed immune thrombocytopenia. Clin Exp Med. (2020) 20:381–5. doi: 10.1007/s10238-020-00630-7

21.

Woodruff RK Grigg AP Firkin FC Smith IL . Fatal thrombotic events during treatment of autoimmune thrombocytopenia with intravenous immunoglobulin in elderly patients. Lancet. (1986) 328:217–8. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(86)92511-0

22.

Ramírez E Romero-Garrido JA López-Granados E Borobia AM Pérez T Medrano N et al . Symptomatic thromboembolic events in patients treated with intravenous-immunoglobulins: results from a retrospective cohort study. Thromb Res. (2014) 133:1045–51. doi: 10.1016/j.thromres.2014.03.046

23.

Daniel GW Menis M Sridhar G Scott D Wallace AE Ovanesov MV et al . Immune globulins and thrombotic adverse events as recorded in a large administrative database in 2008 through 2010. Transfusion. (2012) 52:2113–21. doi: 10.1111/j.1537-2995.2012.03589.x

24.

Fda Cber . CSL Behring Immune Globulin Intravenous (Human), 10% Liquid, Privigen highlights of prescribing information (2017). 1–30. Available at: https://www.fda.gov/downloads/BiologicsBloodVaccines/BloodBloodProducts/ApprovedProducts/LicensedProductsBLAs/FractionatedPlasmaProducts/UCM303092.pdf

25.

Tan S Tambar S Chohan S Ramsey-Goldman R Lee C . Acute myocardial infarction after treatment of thrombocytopenia in a young woman with systemic lupus erythematosus. J Clin Rheumatol. (2008) 14:350–2. doi: 10.1097/RHU.0b013e31817de0fb

26.

Elkayam O Paran D Milo R Davidovitz Y Almoznino-Sarafian D Zeltser D et al . Acute myocardial infarction associated with high dose intravenous immunoglobulin infusion for autoimmune disorders. A study of four cases. Ann Rheum Dis. (2000) 59:77–80. doi: 10.1136/ard.59.1.77

27.

Eliasberg T Saliba WR Elias M . Acute myocardial infarction during intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG) therapy. Eur J Intern Med. (2007) 18:166. doi: 10.1016/j.ejim.2006.09.011

28.

Paolini R Fabris F . Acute myocardial infarction during treatment with intravenous immunoglobulin for idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura (ITP). Am J Hematol. (2000) 65:176–9. doi: 10.1215/9780822379225-005

29.

Stamboulis E Theodorou V Kilidireas K Apostolou T . Acute myocardial infarction following intravenous immunoglobulin therapy for chronic inflammatory demyelinating polyneuropathy in association with a monoclonal immunoglobulin G paraprotein. Eur Neurol. (2004) 51:51. doi: 10.1159/000075091

30.

Barsheshet A Marai I Appel S Zimlichman E . Acute ST elevation myocardial infarction during intravenous immunoglobulin infusion. Ann N Y Acad Sci. (2007) 1110:315–8. doi: 10.1196/annals.1423.033

31.

Vinod KV Kumar M Nisar KK . High dose intravenous immunoglobulin may be complicated by myocardial infarction. Indian J Crit Care Med. (2014) 18:247–9. doi: 10.4103/0972-5229.130579

32.

Stenton SB Dalen D Wilbur K . Myocardial infarction associated with intravenous immune globulin. Ann Pharmacother. (2005) 39:2114–8. doi: 10.1345/aph.1G104

33.

Davé S Hagan J . Myocardial infarction during intravenous immunoglobulin infusion in a 65-year-old man with common variable immunodeficiency and subsequent successful repeated administration. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. (2007) 99:567–70. doi: 10.1016/S1081-1206(10)60388-2

34.

Mizrahi M Adar T Orenbuch-Harroch E Elitzur Y . Non-ST elevation myocardial infraction after high dose intravenous immunoglobulin infusion. Case Rep Med. (2009) 2009:1–4. doi: 10.1155/2009/861370

35.

Vucic S Siao P Chong T Dawson KT Cudkowicz M Cros D . Thromboembolic complications of intravenous immunoglobulin treatment. Eur Neurol. (2004) 52:141–4. doi: 10.1159/000081465

36.

Hefer D Jaloudi M . Thromboembolic events as an emerging adverse effect during high-dose intravenous immunoglobulin therapy in elderly patients: a case report and discussion of the relevant literature. Ann Hematol. (2004) 83:661–5. doi: 10.1007/s00277-004-0895-2

37.

Zaidan R Al Moallem M Wani BA Shameena AR Tahan ARA Daif AK et al . Thrombosis complicating high dose intravenous immunoglobulin: report of three cases and review of the literature. Eur J Neurol. (2003) 10:367–72. doi: 10.1046/j.1468-1331.2003.00542.x

38.

Guo Y Tian X Wang X Xiao Z . Adverse effects of immunoglobulin therapy. Front Immunol. (2018) 9:1299. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2018.01299

39.

Severinsen MT Engebjerg MC Farkas DK Jensen AØ Nørgaard M Zhao S et al . Risk of venous thromboembolism in patients with primary chronic immune thrombocytopenia: a Danish population-based cohort study. Br J Haematol. (2011) 152:360–2. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2010.08418.x

40.

Cheng G . Eltrombopag, a thrombopoietin-receptor agonist in the treatment of adult chronic immune thrombocytopenia: a review of the efficacy and safety profile. Ther Adv Hematol. (2012) 3:155–64. doi: 10.1177/2040620712442525

41.

Shirley M . Avatrombopag: First Global Approval. Drugs. (2018) 78:1163–8. doi: 10.1007/s40265-018-0949-8

42.

Kim ES . Lusutrombopag: first global approval. Drugs. (2016) 76:155–8. doi: 10.1007/s40265-015-0525-4

43.

Wang B Nichol JL Sullivan JT . Pharmacodynamics and pharmacokinetics of AMG 531, a novel thrombopoietin receptor ligand. Clin Pharmacol Ther. (2004) 76:628–38. doi: 10.1016/j.clpt.2004.08.010

44.

Zhou H Xu M Qin P Zhang HY Yuan CL Zhao HG et al . A multicenter randomized open-label study of rituximab plus rhTPO vs rituximab in corticosteroid-resistant or relapsed ITP. Blood. (2015) 125:1541–7. doi: 10.1182/blood-2014-06-581868

45.

Deng J Hu H Huang F Huang C Huang Q Wang L et al . Comparative efficacy and safety of thrombopoietin receptor agonists in adults with thrombocytopenia: a systematic review and network meta-analysis of randomized controlled trial. Front Pharmacol. (2021) 12:1–11. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2021.704093

46.

Doobaree IU Nandigam R Bennett D Newland A Provan D . Thromboembolism in adults with primary immune thrombocytopenia: a systematic literature review and meta-analysis. Eur J Haematol. (2016) 97:321–30. doi: 10.1111/ejh.12777

47.

Kado R Mccune WJ . Treatment of primary and secondary immune thrombocytopenia. Curr Opin Rheumatol. (2019) 31:213–22. doi: 10.1097/BOR.0000000000000599

48.

Rodeghiero F . Is ITP a thrombophilic disorder?Am J Hematol. (2016) 91:39–45. doi: 10.1002/ajh.24234

49.

Afdhal NH Giannini EG Tayyab G Mohsin A Lee JW Andriulli A et al . Eltrombopag before procedures in patients with cirrhosis and thrombocytopenia. N Engl J Med. (2012) 367:716–24. doi: 10.1056/nejmoa1110709

50.

Hidaka H Kurosaki M Tanaka H Kudo M Abiru S Igura T et al . Lusutrombopag reduces need for platelet transfusion in patients with thrombocytopenia undergoing invasive procedures. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. (2019) 17:1192–200. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2018.11.047

51.

Tateishi R Seike M Kudo M Tamai H Kawazoe S Katsube T et al . A randomized controlled trial of lusutrombopag in Japanese patients with chronic liver disease undergoing radiofrequency ablation. J Gastroenterol. (2019) 54:171–81. doi: 10.1007/s00535-018-1499-2

52.

Peck-Radosavljevic M Simon K Iacobellis A Hassanein T Kayali Z Tran A et al . Lusutrombopag for the treatment of thrombocytopenia in patients with chronic liver disease undergoing invasive procedures (L-PLUS 2). Hepatology. (2019) 70:1336–48. doi: 10.1002/hep.30561

53.

Terrault N Chen YC Izumi N Kayali Z Mitrut P Tak WY et al . Avatrombopag before procedures reduces need for platelet transfusion in patients with chronic liver disease and thrombocytopenia. Gastroenterology. (2018) 155:705–18. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2018.05.025

54.

Jurczak W Chojnowski K Mayer J Krawczyk K Jamieson BD Tian W et al . Phase 3 randomised study of avatrombopag, a novel thrombopoietin receptor agonist for the treatment of chronic immune thrombocytopenia. Br J Haematol. (2018) 183:479–90. doi: 10.1111/bjh.15573

55.

Kuter DJ Allen LF . Avatrombopag, an oral thrombopoietin receptor agonist: results of two double-blind, dose-rising, placebo-controlled phase 1 studies. Br J Haematol. (2018) 183:466–78. doi: 10.1111/bjh.15574

56.

Bussel JB Kuter DJ Aledort LM Kessler CM Cuker A Pendergrass KB et al . A randomized trial of avatrombopag, an investigational thrombopoietin-receptor agonist, in persistent and chronic immune thrombocytopenia. Blood. (2014) 123:3887–94. doi: 10.1182/blood-2013-07-514398

57.

Cheng G Saleh MN Marcher C Vasey S Mayer B Aivado M et al . Eltrombopag for management of chronic immune thrombocytopenia (RAISE): a 6-month, randomised, phase 3 study. Lancet. (2011) 377:393–402. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60959-2

58.

Yang R Li J Jin J Huang M Yu Z Xu X et al . Multicentre, randomised phase III study of the efficacy and safety of eltrombopag in Chinese patients with chronic immune thrombocytopenia. Br J Haematol. (2017) 176:101–10. doi: 10.1111/bjh.14380

59.

Bussel JB Provan D Shamsi T Cheng G Psaila B Kovaleva L et al . Effect of eltrombopag on platelet counts and bleeding during treatment of chronic idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. (2009) 373:641–8. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60402-5

60.

Tomiyama Y Miyakawa Y Okamoto S Katsutani S Kimura A Okoshi Y et al . A lower starting dose of eltrombopag is efficacious in Japanese patients with previously treated chronic immune thrombocytopenia. J Thromb Haemost. (2012) 10:799–806. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2012.04695.x

61.

Bussel JB Kuter DJ George JN McMillan R Aledort LM Conklin GT et al . AMG 531, a thrombopoiesis-stimulating protein, for chronic ITP. N Engl J Med. (2006) 355:1672–81. doi: 10.1056/nejmoa054626

62.

Kuter DJ Bussel JB Lyons RM Pullarkat V Gernsheimer TB Senecal FM et al . Efficacy of romiplostim in patients with chronic immune thrombocytopenic purpura: a double-blind randomised controlled trial. Lancet. (2008) 371:395–403. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60203-2

63.

Shirasugi Y Ando K Miyazaki K Tomiyama Y Okamoto S Kurokawa M et al . Romiplostim for the treatment of chronic immune thrombocytopenia in adult Japanese patients: a double-blind, randomized phase III clinical trial. Int J Hematol. (2011) 94:71–80. doi: 10.1007/s12185-011-0886-8

64.

Allred AJ Bowen CJ Park JW Peng B Williams DD Wire MB et al . Eltrombopag increases plasma rosuvastatin exposure in healthy volunteers. Br J Clin Pharmacol. (2011) 72:321–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.2011.03972.x

65.

Semple JW . Rituximab disciplines T cells, spares platelets. Blood. (2007) 110:2784–5. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-06-094839

66.

Stasi R Pagano A Stipa E Amadori S . Rituximab chimeric anti-CD20 monoclonal antibody treatment for adults with chronic idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura. Blood. (2001) 98:952–7. doi: 10.1182/blood.V98.4.952

67.

Coopamah MD Garvey MB Freedman J Semple JW . Cellular immune mechanisms in autoimmune thrombocytopenic purpura: an update. Transfus Med Rev. (2003) 17:69–80. doi: 10.1053/tmrv.2003.50004

68.

Stasi R del Poeta G Stipa E Evangelista ML Trawinska MM Cooper N et al . Response to B-cell-depleting therapy with rituximab reverts the abnormalities of T-cell subsets in patients with idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura. Blood. (2007) 110:2924–30. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-02-068999

69.

Stasi R Cooper N del Poeta G Stipa E Laura Evangelista M Abruzzese E et al . Analysis of regulatory T-cell changes in patients with idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura receiving B cell depleting therapy with rituximab. Blood. (2008) 112:1147–50. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-12-129262

70.

Armitage JD Montero C Benner A Armitage JO Bociek G . Acute coronary syndromes complicating the first infusion of rituximab. Clin Lymphoma Myeloma. (2008) 8:253–5. doi: 10.3816/CLM.2008.n.035

71.

Arunprasath P Gobu P Dubashi B Satheesh S Balachander J . Rituximab induced myocardial infarction: a fatal drug reaction. J Cancer Res Ther. (2011) 7:346–8. doi: 10.4103/0973-1482.87003

72.

Renard D Cornillet L Castelnovo G . Myocardial infarction after rituximab infusion. Neuromuscul Disord. (2013) 23:599–601. doi: 10.1016/j.nmd.2013.03.014

73.

Gogia A Khurana S Paramanik R . Acute myocardial infarction after first dose of rituximab infusion. Turkish J Hematol. (2014) 31:95–6. doi: 10.4274/Tjh.2013.0247

74.

Sijl A Weele W Nurmohamed M . Myocardial infarction after rituximab treatment for rheumatoid arthritis: is there a link?Curr Pharm Des. (2014) 20:496–9. doi: 10.2174/13816128113199990386

75.

Keswani AN Williams C Fuloria J Polin NMJE . Rituximab-induced acute ST elevation myocardial infarction. Ochsner J. (2015) 15:187–90. doi: 10.1002/9781118484784.ch8

76.

Verma SK . Updated cardiac concerns with rituximab use: a growing challenge. Indian Heart J. (2016) 68:S246–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ihj.2015.10.374

77.

Mehrpooya M Vaseghi G Eshraghi A Eslami N . Delayed myocardial infarction associated with rituximab infusion: a case report and literature review. Am J Ther. (2016) 23:e283–7. doi: 10.1097/MJT.0000000000000214

78.

Arenja N Zimmerli L Urbaniak P Vogel R . Acute anterior myocardial infarction after rituximab. Dtsch Med Wochenschr. (2016) 141:500–3. doi: 10.1055/s-0041-106055

79.

Sharif K Watad A Bragazzi NL Asher E Abu Much A Horowitz Y et al . Anterior ST-elevation myocardial infarction induced by rituximab infusion: a case report and review of the literature. J Clin Pharm Ther. (2017) 42:356–62. doi: 10.1111/jcpt.12522

80.

Ghanima W Khelif A Waage A Michel M Tjønnfjord GE Romdhan NB et al . Rituximab as second-line treatment for adult immune thrombocytopenia (the RITP trial): a multicentre, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. (2015) 385:1653–61. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61495-1

81.

Garabet L Holme PA Darne B Khelif A Tvedt THA Michel M et al . The risk of thromboembolism associated with treatment of ITP with rituximab: adverse event reported in two randomized controlled trials. Blood. (2019) 134:4892. doi: 10.1182/blood-2019-126974

82.

Wallentin L Becker RC Budaj A Cannon CP Emanuelsson H Held C et al . Ticagrelor versus clopidogrel in patients with acute coronary syndromes. N Engl J Med. (2009) 361:1045–57. doi: 10.1056/nejmoa0904327

83.

Wiviott SD Braunwald E McCabe CH Montalescot G Ruzyllo W Gottlieb S et al . Prasugrel versus clopidogrel in patients with acute coronary syndromes: commentary. Rev Port Cardiol. (2007) 357:2001–15. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0706482

84.

Newland A Lee EJ McDonald V Bussel JB . Fostamatinib for persistent/chronic adult immune thrombocytopenia. Immunotherapy. (2018) 10:9–25. doi: 10.2217/imt-2017-0097

85.

Cooper N Altomare I Thomas MR Nicolson PLR Watson SP Markovtsov V et al . Assessment of thrombotic risk during long-term treatment of immune thrombocytopenia with fostamatinib. Ther Adv Hematol. (2021) 12:20406207211010875. doi: 10.1177/20406207211010875

86.

Lieu T Ruchika G Lakshmanan K . Platelet transfusions in patients with immune thrombocytopenic purpura (ITP) – evaluation of the current Nationwide inpatient hospital practices. Blood. (2010) 116:3809. doi: 10.1182/blood.V116.21.3809.3809

87.

Hirsh J Raschke R Warkentin TE Dalen JE Deykin D Poller L . Heparin: mechanism of action, pharmacokinetics, dosing considerations, monitoring, efficacy, and safety. Chest. (1995) 108:258S–75S. doi: 10.1378/chest.108.4_supplement.258s

Summary

Keywords

immune thrombocytopenia, acute coronary syndrome, corticosteroids, intravenous immunoglobulin, thrombopoietin receptor agonist, rituximab

Citation

Rahhal A, Provan D, Ghanima W, González-López TJ, Shunnar K, Najim M, Ahmed AO, Rozi W, Arabi A and Yassin M (2024) A practical guide to the management of immune thrombocytopenia co-existing with acute coronary syndrome. Front. Med. 11:1348941. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2024.1348941

Received

03 December 2023

Accepted

19 February 2024

Published

11 April 2024

Volume

11 - 2024

Edited by

Ahmet Emre Eskazan, Istanbul University-Cerrahpasa, Türkiye

Reviewed by

Yildiz Ipek, Istanbul Kartal Dr. Lutfi Kirdar Education and Research Hospital, Türkiye

David Gomez-almaguer, Autonomous University of Nuevo León, Mexico

Updates

Copyright

© 2024 Rahhal, Provan, Ghanima, González-López, Shunnar, Najim, Ahmed, Rozi, Arabi and Yassin.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Alaa Rahhal, arahhal1@hamad.qa

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.