Abstract

For short periods, even without the presence of red blood cells, hyperbaric oxygen can safely allow plasma to meet the oxygen delivery requirements of a human at rest. By this means, hyperbaric oxygen, in special instances, may be used as a bridge to lessen blood transfusion requirements. Hyperbaric oxygen, applied intermittently, can readily avert oxygen toxicity while meeting the body's oxygen requirements. In acute injury or illness, accumulated oxygen debt is shadowed by adenosine triphosphate debt. Hyperbaric oxygen efficiently provides superior diffusion distances of oxygen in tissue compared to those provided by breathing normobaric oxygen. Intermittent application of hyperbaric oxygen can resupply adenosine triphosphate for energy for gene expression and reparative and anti-inflammatory cellular function. This advantageous effect is termed the hyperbaric oxygen paradox. Similarly, the normobaric oxygen paradox has been used to elicit erythropoietin expression. Referfusion injury after an ischemic insult can be ameliorated by hyperbaric oxygen administration. Oxygen toxicity can be averted by short hyperbaric oxygen exposure times with air breaks during treatments and also by lengthening the time between hyperbaric oxygen sessions as the treatment advances. Hyperbaric chambers can be assembled to provide everything available to a patient in modern-day intensive care units. The complication rate of hyperbaric oxygen therapy is very low. Accordingly, hyperbaric oxygen, when safely available in hospital settings, should be considered as an adjunct for the management of critically injured or ill patients with disabling anemia.

Preclinical introduction

The clinical use of hyperbaric oxygen therapy (HBOT) to address the absence of sufficient hemoglobin levels began with the work of Dutch surgeon, I. Boerema, in the late 1950s. He rapidly exsanguinated swine to hemoglobin levels as low as 1 g per deciliter and then resuscitated them by intravenous volume repletion with a Ringer's lactate–dextran 6%–dextrose water 5% solution. Next, he pressurized the unconscious, collapsed but still breathing, swine to three atmospheres of pressure in a hyperbaric chamber and made them breathe 100% oxygen. At three atmospheres of pressure, inhaled oxygen of 100% provided a surface equivalent fraction of inhaled oxygen of 300% (SEFIO2 300%). He kept the swine at three atmospheres of pressure for 15 min and then re-transfused them with their shed blood and depressurized the chamber to the surface, whereupon the swine walked off unimpaired. He published these results in an article entitled “Life Without Blood” (1).

These results were replicated in a laboratory in the United States in 2010 at the LSU Health Sciences Center in New Orleans in an Institutional Animal Care Utilization Committee (IACUC)-approved pilot study. An acutely anesthetized, exsanguinated swine was monitored by a polarographic oxygen tension probe through a cranial burr hole (2). The swine, breathing normobaric room air, had a baseline brain tissue pO2 level of 30 mmHg. After a rapid exsanguination involving the removal of 40% of the blood volume, the swine's brain tissue pO2 dropped to 0 mmHg even while the swine was being ventilated with normobaric 100% oxygen. For volume replacement, the swine received intravenous Ringers' D5W solution. Next, the animal was pressurized inside a hyperbaric chamber while being kept on 100% oxygen inhalation at three atmospheres of pressure. At this pressure, the oxygen inhalation provided SEFIO2 of 300% oxygen. The brain tissue pO2 rose back to 30 mmHg, and the animal remained pressurized for 50 min. Before ascent to the surface, the swine was transfused with its shed blood. Upon reaching the surface at ambient pressure, the animal was recovered from anesthesia, and monitoring access catheters were removed. The swine walked off unimpaired and was returned to a rescue ranch for a long life (3). Table 1 shows a summary of published animal experiments investigating the use of HBOT in severe anemia. The tabular summary includes a thumbnail of evidence-based analysis using three different criteria (AHA/NCI-PDQ/BMJ) (4).

Table 1

| Date | References | Animal species | Study groups | Hemorrhagic insult | Survival rates | Thumbnail evidence-based analysis | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | 1943 | Frank et al. (5) | Canine | 1. Paper relied-on non-HBO2 controls from results of independent authors in the same model 2. Controlled study of 3 HBO2 0.3 MPa 150-180 min treatment group (n = 18) |

Wiggers and Werle (6) “hypo-MAP” model for all animals | Survival at 4 h post-hem: 1. non-HBO2 group (NBA or NBO2) = 0% 2. HBO2 groups = 20% |

AHA | NCI-PDQ | BMJ evidence | |

| Level | Class | NA | NA | |||||||

| 6B | Indeter minate | |||||||||

| 2. | 1959 | Burnet et al. (7) | Rat | Controlled study: 1. NBA/120 min group (n = 25) 2. HBO2 0.2 Mpa/120 min group (n = 25) |

Intravascular hemolysis induced by 1 ml/100 g IM glycerol for all animals | Survival at 2 h. post insult, post-hem: 1. non-HBO2 group (NBA) = 20% 2. HBO2 group = 96% |

AHA | NCI-PDQ | BMJ evidence | |

| Level | Class | NA | NA | |||||||

| 6A | II.b. | |||||||||

| 3. | 1959 | Boerema et al. (1, 8) | Porcine | Controlled study: 1. HBO2 0.3 MPa/∴ι 75 min group (n = 3) HBO2 0.3 MPa with 30°C core temp/∴ι 75 min group (n = 20) NBA group (n = ?) |

All animals were subjected to variable volume bleed which produced Hgb level of 0.4-0.6 g/dL | Survival at 45 min post-hem: HBO2 group = 100% HBO2 + hypothermic group = 50% NBA group = 0/2 |

AHA | NCI-PDQ | BMJ evidence | |

| Level | Class | NA | NA | |||||||

| 6B | II.b. | |||||||||

| 4. | 1962 | Attar et al. (9) | Canine | Controlled study: 1. NBA group (n = 30) 2. HBO2 0.3 MPa/90 minutes group (n = 25) |

Wiggers and Werle (6) “hypo-MAP” model for all animals | Survival at 48 h post-hem: NBA group = 17% HBO2 group = 74% |

AHA | NCI-PDQ | BMJ evidence | |

| Level | Class | NA | NA | |||||||

| 6B | II.b. | |||||||||

| 5. | 1963 | Cowley et al. (10) | Canine | Controlled study: 1. NBA with hem group (n = 30) 2. HBO2 with hem 0.3 MPa/150 min group (n = 19) 3. HBO2 without hem 0.3 MPa/150 min group (n = 13) |

Wiggers and Werle (6) “hypo-MAP” model for all animals | Survival at 48 h post-hem: 1. NBA with hem group = 17% 2. HBO2 with hem group = 74% 3. HBO2 without hem group = 100% |

AHA | NCI-PDQ | BMJ evidence | |

| Level | Class | NA | NA | |||||||

| 6A | II.b. | |||||||||

| 6. | 1964 | Blair et al. (11) | Canine | Controlled study: NBA group (n = 23) HBO2 0.3 MPa/120 min group (n = 19) |

Wiggers and Werle (6) “hypo-MAP” model for all animals | “Long-term” survival post-hem: NBA group = 17% HBO2 group = 74% |

AHA | NCI-PDQ | BMJ evidence | |

| Level | Class | NA | NA | |||||||

| 6A | II.b. | |||||||||

| 7. | 1965 | Clark and Young (12) | Canine | Controlled study: NBA group (n = 8) HBO2 0.2 MPa/150 min group (n = 5) NBA + IV bicarb group (n = 6) |

Wiggers and Werle (6) “hypo-MAP” model for all animals | Survival at 18 h post-hem: NBA group = 75% HBO2 group = 100% |

AHA | NCI-PDQ | BMJ evidence | |

| Level | Class | NA | NA | |||||||

| 6A | II.b. | |||||||||

| 8. | 1965 | Cowley et al. (13) | Canine | Controlled study: 1. NBA group (n = 23) 2. HBO2 0.3 MPa/120 min group (n = 19) |

Wiggers and Werle (6) “hypo-MAP” model for all animals | Survival at 48 h post-hem: 1. NBA group = 22% 2. HBO2 group = 74% |

AHA | NCI-PDQ | BMJ evidence | |

| Level | Class | NA | NA | |||||||

| 6A | II.b. | |||||||||

| 9. | 1965 | Elliot and Paton (14) | Canine | Controlled study: 1. NBA group (n = 10) 2. NBO2 group (n = 10) 3. NBO2 with ventilator group (n = 10) 4. HBO2 0.28 MPa/100 min group (n = 11) |

Wiggers and Werle (6) “hypo-MAP” model for all animals | Survival at 72 h post-hem: 1. NBA group = 10% 2. NBO2 group = 50% 3. NBO2 with ventilator group = 50% 4. HBO2 group = 73% |

AHA | NCI-PDQ | BMJ evidence | |

| Level | Class | NA | NA | |||||||

| 6A | II.b. | |||||||||

| 10. | 1965 | Attar et al. (15) | Canine | Controlled study: Group I: 1. NBA/150 min subgroup (n = 25) 2. HBO2 0.3 Mpa/150 min subgroup (n = 29) Group II: Subgroup A 3. NBA/105 min group (n = 30) 4. HBO2 0.3 Mpa/105 min group (n = 22) Subgroup B 5. NBA/120 min group (n = 17) 6. NBO2/120 min group (n = 25) 7. HBO2/120 min group (n = 23) Subgroup C 8. NBA/150 min group (n = 30) 9. HBO2 0.3 MPa/ 0 min group (n = 4) Subgroup D 10. NBA/240 min group (n = 20) (n = ?) 11. HBO2 0.3 MPa/240 min group (n = 24) Group III: 12. HBO2 0.3 MPa/120 min started 30 min post-hem group (n = ?) 13. HBO2 0.3 MPa/120 min started 150 min post-hem group (n = ?) Group IV: 14. HBO2 0.2 MPa/120 min group (n = 11) 15. HBO2 0.2 MPa/150 min group (n = ?) 16. HBO2 0.3 MPa/120 min (n = 23) see above 17. HBO2 0.3 MPa/130 min (n = 4)see above |

Wiggers and Werle (6) “hypo-MAP” model for all animals | Survival at 72 h post-hem: 1. NBA group = 20% 2. HBO2 group = 41% 3. NBA group = 66% 4. HBO2 group = 47% 5. NBA group = 29% 6. NBO2 group = 20% 7. HBO2 group = 72% 8. NBA group = 17% 9. HBO2 group = 50% 10. NBA group = 50% 11. HBO2 group = 48% 12. HBO2 30 min post- hem = 74% 13. HBO2 150 min post-hem 50% 14. HBO2 0.2 MPa/120 min = 82% (n = ?) 15. HBO2 0.2 MPa/150 min = 30% 16. HBO2 0.3 MPa/120 min = 72% 17. HBO2 0.3 MPa/150 min = 50% |

AHA | NCI-PDQ | BMJ evidence | |

| Level | Class | NA | NA | |||||||

| 6A | II.b. | |||||||||

| 11. | 1965 | Jacobsonet al. (16, 17) | Rabbit | Controlled study: 1. NBA group (n = 10) 2. NBO2 group (n = 10) 3. HBO2 0.2 MPa/12 h (n = 10) |

Wiggers and Werle (6) “hypo-MAP” model for all animals | Survival at 48 h post-hem: 1. NBA group = 0% 2. NBO2 group = 10% 3. HBO2 group = 10% |

AHA | NCI-PDQ | BMJ evidence | |

| Level | Class | NA | NA | |||||||

| 6A | II.b. | |||||||||

| 12. | 1965 | Whalen et al. (18) | Canine | Controlled study: 1. NBA group (n = 5) 2. NBO2 group (n = 5) 3. HBO2 0.35 MPa (n = 5) 4. HBO2 0.35 MPa |

Complete replacement of blood volume of group 4 animals with dextran 6%/dextrose, 5%/RL solution to produce a Hct of 0.5% | All groups 100% survival, but group 4 had increased cardiac output and decreased peripheral vascular resistance | AHA | NCI-PDQ | BMJ evidence | |

| Level | Class | NA | NA | |||||||

| 6B | Indeter minate | |||||||||

| 13. | 1965 | Navarro and Ferguson (19) | Canine | Controlled study: 1. NBA/120 min dextran group (n = 15) 2. NBA/120 min dextrose group (n = 15) 3. HBO2 0.35 MPa/120 min dextran group (n = 15) 4. HBO2 0.35 MPa/120 min dextrose group |

Wiggers and Werle (6) “hypo-MAP” model for all animals | Survival at 48 h post-hem after administration of exp: 1. NBA dextran group = 26% 2. NBA dextrose group = 6.6% HBO2 dextran group = 60% 3. HBO2 dextrose group = 60% |

AHA | NCI-PDQ | BMJ evidence | |

| Level | Class | NA | NA | |||||||

| 6A | II.b. | |||||||||

| 14. | 1969 | Necas and Neuwirt (20) | Rat | Controlled study: 1a. NBA group (n = 5) 2a. HBO2 0.3 MPa/360-420 min group (n = 3) 3a. HBO2 0.2 MPa/360-420 min group (n = 2) 1b. NBA group (n = 3) 2b. HBO2 0.3 MPa/360-420 min group (n = 4) 3b. NBA group (n = 13) 4b. HBO2 0.3 MPa/360-420 min group (n = 9) |

Group a: Hemorrhage to Hct of 25% Group b: Hemorrhage to Hct of 10% | Survival at h: 1a. NBA with Hct 25% group = 60% 2a. HBO2 with Hct 25% group = 100% 3a. HBO2 with Hct 25% group = 100% 1b. NBA with Hct 10% = 0% 2b. HBO2 with Hct 10% = 100% 3b. NBA with Hct 10% group = 0% 4b. HBO2 with Hct 10% = 100% |

AHA | NCI-PDQ | BMJ evidence | |

| Level | Class | NA | NA | |||||||

| 6A | II.b. | |||||||||

| 15. | 1970 | Doi and Onji (21) | Canine | Controlled study: 1. NBA/90 min (∴ι120 min) group (n = 7) 2. HBO2 0.2 MB/90 min (∴ι 120 min) group (n = 7) |

Wiggers and Werle (6) “hypo-MAP” model for all animals | Survival at 4 h post-hem: 1. NBA group = 0% 2. HBO2 group = 100% |

AHA | NCI-PDQ | BMJ evidence | |

| Level | Class | NA | NA | |||||||

| 6A | II.b. | |||||||||

| 16. | 1970 | Oda and Takeori (22) | Canine | Controlled study: 1. NBA NS/5% dextran 40/80 min (n = 5) 2. HBO2 0.3 MPa/60 min NS/3% dextran 40 group (n = 5) 3. NBA NS/5% dextran 200 group (n = 5) 4. HBO2 0.3 MPa/60 min NS/6% dextran 200 group (n = 5) |

25 ml/kg shed blood with exchange of NS designated exchange followed by continued bleed to produce a Hct of 18% | Survival rates: 1. NBA dextran 40 group = 100% 2. HBO2 dextran 40 group = 100% 3. NBA dextran 200 group = 100% 4. HBO2 dextran 200 group = 100% |

AHA | NCI-PDQ | BMJ evidence | |

| Level | Class | NA | NA | |||||||

| 6A | Indeter minate | |||||||||

| 17. | 1974 | Trytyshnkov (23) | Rat | Controlled study: 1. NBA no hem group 2. NBA with hem group 3. HBO2 0.2 MPa/60 min no hem group 4. immediate HBO2 0.2 MPa/60 min post-hem group 5. delayed HBO2 0.2 MPa/60 min post-hem group (total n = 179) |

3% body weight hemorrhage by jugular blood draw over 30 min | Survival rates: 1. NBA group = 100% 2. NBA with hem group = 0% 3. HBO2 no hem group = 100% 4. immediate HBO2 post-hem group = 100% 5. delayed HBO2 post- hem group = 0% |

AHA | NCI-PDQ | BMJ evidence | |

| Level | Class | NA | NA | |||||||

| 6B | II.b. | |||||||||

| 18. | 1975 | Norman (24) | Controlled study: | AHA | NCI-PDQ | BMJ evidence | ||||

| Level | Class | NA | NA | |||||||

| 6A | II.b. | |||||||||

| 19. | 1976 | Barkova and Petrov (25) | Rat | Non-controlled study: 1. NBA group (n = 60) 2. HBO2 0.2 MPa/40 min group (n = 60) |

2.8% of body weight blood loss over 30 min | Survival rate: 1. NBA group = 0% 2. HBO2 group = 100% |

AHA | NCI-PDQ | BMJ evidence | |

| Level | Class | NA | NA | |||||||

| 6B | II.b. | |||||||||

| 20. | 1977 | Luonov and Takovlev (26) | Cat | Controlled study: 1. NBA/60 min group (n = ”?”) 2. HBO2 0.3 MPa/60 min group (n = ”?”) |

Wiggers and Werle (6) “hypo-MAP” model for all animals | Survival rate: 1. NBA group = increase in brain ammonia 2. HBO2 group = no increase in brain ammonia |

AHA | NCI-PDQ | BMJ evidence | |

| Level | Class | NA | NA | |||||||

| 6B | Indeter minate | |||||||||

| 21. | 1983-84 | Gross et al. (27–29) | Canine | Controlled study: 1. NBA 6% dextran 40 group (n = 6) 2. NBA RL group (n = 6) 3. NBA 10% dextrose group (n = 6) 4. NBA 6% dextran 70 group (n = 6) 5. HBO2 0.28 MPa/93-118 min 6% dextran-40 group (n = 6) 6. HBO2 0.28 MPa/93-118 min RL group (n = 6) 7. HBO2 0.28 MPa/93-118 min 10% dextrose (n = 6) 8. HBO2 9.28 MPa/93-118 min 6% dextran-70 group (n = 6) 9. HBA 0.6 MPa 6% dextran-40 (n = 6) 10. HBA 0.6 RL group (n = 6) 11. HBA 0.6 MPa 10% dextran group (n = 6) 12. HBO2 0.6 MPa 6% dextran-70 group (n = 6) |

Wigger and Werle (6) “hypo-MAP” model for all animals | Survival post-hem: 1. NBA 6% dextran-40 group = 100% 2. NBA RL group = 100% 3. NBA 10% dextrose group = 100% 4. NBA 6% dextran 70 group = 100% 5. HBO2 6% dextran- 40 group = 100% 6. HBO2 RL group = 100% 7. HBO2 10% dextrose group = 100% 8. HBO2 6% dextran-70 group = 100% 9. HBA 6% dextran-40 grou p = 100% 10. HBA RL group = 100% 11. HBA 10% dextrose group = 100% 12. HBA 6% dextran-70 group = 100% |

AHA | NCI-PDQ | BMJ evidence | |

| Level | Class | NA | NA | |||||||

| 6A | Indeter minate | |||||||||

| 22. | 1991 | Bitterman et al. (30) | Rat | Controlled study: 1. NBA sham group (n = 6) 2. NBA + hem group (n = 10) 3. NBO2/90 min + hem group (n = 10) 4. HB nitrox (7/93) 0.3 MPa/190 min + hem group (n = 8) 5. HBO2 0.3 MPa/90 min sham group (n = 6) 6. HBO2 0.3 MPa/90 min + hem group (n = 10) |

Hemorrhage within 90 min of 3.2 ml all animals so designated | Survival post-hem: MAP > 40 mmHg for 220 min: 1. NBA sham group = 100% 2. NBA + hem group = 10% 3. NBO2 + hem group = 50% 4. HB nitrox + hem group = 0% HBO2 sham group = 100% 5.HBO2 + hem group = 100% |

AHA | NCI-PDQ | BMJ evidence | |

| Level | Class | NA | NA | |||||||

| 6A | II.b. | |||||||||

| 23. | 1992 | Wen-Ren (31) | Canine | Controlled study: 1. NBA/95 min group (n = 6) 2. HBO2 0.3 MPa/95 min group (n = 6) |

Hemorrhage to 60 ml/kg | Survival rate: 1. NBA group = 0% 2. HBO2 group = 100% |

AHA | NCI-PDQ | BMJ evidence | |

| Level | Class | NA | NA | |||||||

| 6A | II.b. | |||||||||

| 24. | 1992 | Marzella et al. (32) | Rat | Controlled study: 1. NBA hem with 90 min monitoring group (n = ”?”) 2. HBO2 hem 15 min then 0.2 MPa/75 min with monitoring group (n = ”?”) |

Hemorrhage to 15 ml/kg | Survival rates not provided for groups 1. NBA group: BP decreased 25%, CO decreased 25% 2. HBO2 group: BP increased 10%, CO decreased 25% |

AHA | NCI-PDQ | BMJ evidence | |

| Level | Class | NA | NA | |||||||

| 6B | Indeter minate | |||||||||

| 25. | 1995 | Adir et al. (33) | Rat | Controlled study: 1. NBA no hem group (n = 11) 2. NBA + hem group (n = 10) 3. NBO2 + hem group (n = 10) 4. HBO2 0.3 MPa/90 min no hem group (n = 7) 5. HBO2 0.3 MPa/90 min + hem group ( n = 10) |

Hemorrhage 3.2 ml/100 g over 120 min for all animals so designated | Survival at 24 hour/7 day post-hem: 1. NBA no hem group = 100%/45% 2. HBA hem group = 70%/10% 3. NBO2 hem group = 90%/70% 4.HBO2 no hem group = 100%/55% 5. HBO2 hem group = 90%/10% |

AHA | NCI-PDQ | BMJ evidence | |

| Level | Class | NA | NA | |||||||

| 6A | Indeter minate | |||||||||

| 26. | 2000 | Yamashita and Yamashita (34) | Rat | Controlled study: 1. NBA + hem group (n = 15) 2. HBO2 0.3 MPa/60 min with 30 min decompression + hem group (n = 10) 3. HBO2 0.3 MPa/60 min with 30 min decompression no hem group (n = 10) |

Hemorrhage of 40 ml/kg over 1 h | Survival at 24 h post-hem: 1. NBA + hem group = 40% 2. HBO2 + hem group = 83% 3. HBO2 no hem group = 100% |

AHA | NCI-PDQ | BMJ | |

| Level | Class | NA | NA | |||||||

| 6A | IIb | |||||||||

Summary of published animal experiments investigating the use of hyperbaric oxygen therapy in severe anemia.

The clinical use of hyperbaric oxygen

Hyperbaric oxygen (HBO) may be used as a bridging therapy in the Advanced Trauma Life Support (ATLS) and Advanced Cardiac Life Support (ACLS) resuscitation of a precariously anemic patient to prevent multiunit transfusion until damage control surgical efforts can be implemented. The initial damage control surgery aims at preventing continued blood loss to allow the patient to retain transfused blood (35).

Likewise, HBO may be used as a bridging therapy for patients who refuse blood transfusions due to religious or philosophical reasons. Tincture of time could then allow the provision of hematinic nutrients and pharmaceuticals to support hematopoiesis to endogenously provide red blood cell replacement (36). If hemoglobin's ability to transport oxygen by carbon monoxide, cyanide, or hydrogen sulfide is impaired, HBO can be used acutely to treat these conditions to assist in patient recovery from the chemical hypoxia imposed by the poisoning (37–41).

In yet another clinical instance, HBO may be used if an anticipated complication of a blood transfusion precludes further transfusion (42):

-

Blood group incompatibility.

-

Febrile non-hemolytic transfusion reaction (FNHTR).

-

Both delayed amnestic and primary hemolytic anemia.

-

Allergy from urticaria to anaphylaxis.

-

Transfusion-associated graft-versus-host disease (TAGVHD).

-

Acute radiation-induced anemia in disasters with a supply shortage.

-

Transfusion-transmitted infections (TTI).

-

Both red blood cell and human leukocyte antigen (HLA) allosensitization.

-

Confounding severe congestive heart failure with profound anemia until stabilization, providing the safety of transfusion.

-

Stacking hemosiderosis from multiple transfusions by lessening the number of transfusions.

-

The prevention of long-term transfusion immunomodulation by lessening the number of transfusions.

-

The prevention of short-term induction of multiorgan failure by red blood cell-associated lipids and cytokines.

-

Transfusion-related lung injury (TRALI).

HBOT has been documented to ameliorate the adult respiratory syndrome induced by trauma or infection in severely anemic patients (43–46). This effect of HBOT may also be found to be an additional advantage of HBO as a bridging treatment until safe transfusions are possible in a patient with TRALI or acute respiratory distress (ARDS) in SARS-CoV2 patients with severe anemia (47). Research into this area is necessary. A randomized, controlled study has been published evidencing the use of HBOT to perform this (44). Table 2 shows human case studies and series for use in the treatment of severe anemia. The tabular summary includes a thumbnail, evidence-based analysis of the published papers using three different criteria (AHA/NCI-PDQ/BMJ) (4). More recently, a randomized, controlled trial of HBOT used in severe anemia has been published (57).

Table 2

| Date | References | Pt age/gender | Quantification of hemorrhagic insult | Adjunctive transfusion | Adjunctive hematinics and HBO2 | Survival | Thumbnail evidence-based analysis | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | 1969 | Ledingham (48) | 40 y/female | Admission Hgb = 1.5 g/dL Admission BP = 65/? Admission sensorium = AMS |

Yes (patient was transfused after stabilization by completed HBO2) | B12 folic acid, ascorbic acid HBO2 0.2 Mpa/5 hr + (at depth the pt would seize at first when oxygen mask was removed) |

Yes | AHA | NCI-PDQ | BMJ evidence | |

| Level | Class | 3.iii. | Likely to be beneficial | ||||||||

| 5 | Indeter minate | ||||||||||

| 2. | 1969 | Amonic et al. (49) | 26 y/male (JW) | S/P resuscitation of leiomyoma to resolve GI bleed Post-op Hct = 10% 3rd post-op day = CHF Serial HBO2 7th post-op day Hct = 12% 7th post-op week Hct = 42% |

No | Hematinics – yes Serial 17 cycles of HBO2 0.2 MPa/160 min (at depth the pt initially seized when oxygen mask was removed) |

Yes | AHA | NCI-PDQ | BMJ evidence | |

| Level | Class | 3.iii. | Likely to be beneficial | ||||||||

| 5 | Indeter minate | ||||||||||

| 3. | 1974 | Hart (50) | 27 y/female (JW) 67 y/female (JW) 27 y/male (JW) |

Perinatal pelvic hematoma and pulmonary embolism with Hgb 3.8 g/dL, congestive heart failure, AMS, and 88/40 BP Diverticulosis with rectal bleeding with Hgb 2.6 g/dL, AMS, and 90/70 BP MVA with liver laceration with Hgb 6.9 g/dL | No Yes (pt was transfused 2 units PRBC's on 4th hospital day after Continued bleeding) No | Iron dextran IM Serial HBO2 0.2 MPa/90 Iron dextran IM Serial HBO2 0.2 MPa/90 Iron dextran IM Serial HBO2 0.2 MPa/90 | Yes Yes Yes | AHA | NCI-PDQ | BMJ evidence | |

| Level | Class | 3.iii. | Likely to be beneficial | ||||||||

| 5 | Indeter minate | ||||||||||

| 4. | 1974 | Myking and Schreinen (51) | 55 y /female | AIHA with HGB 4.6 g/dL Failed prednisone with Hgb falling to 3 g/dL with AMS Serial HBO2 x 5 days with Hgb 5 g/dL | No | Prednisone Serial HBO2 0.26 MPa/240 min QID tapered to HBO2 0.26 MPa/120 min BID to day 5 with D/C | Yes | AHA | NCI-PDQ | BMJ evidence |

|

| Level | Class | 3.iii. | Likely to be beneficial | ||||||||

| 5 | Indeter minate | ||||||||||

| Level | Class | ||||||||||

| 5. | 1987 | Hart et al. (52) | 20 females (JW) 6 males (JW) (subgroup analysis of those patients without AMS leaves 19 pts) | Mean Hct of all 26 patients = 13% (all with class IV hem) | No No | All had hematinics, vitamin B12, vitamin c, iron All patients averaged 9.6 HBO2 sessions 0.2 MPa/90 min | 65% 83% 95% | AHA | NCI-PDQ | BMJ evidence | |

| Level | Class | 3.iii. | Beneficial | ||||||||

| 5 | II.b. | ||||||||||

| 6. | 1989 | Myerstein et al. (53) | 4 individual human blood samples were tested for levels of GSH, Hct/ free Hgb, MetHgb, and RBC volume | Study groups: Control RBCs, both fresh and stored samples Low GSH RBCs induced by diamide in both fresh and stored samples RBCs exposed to HBO2 0.3 MPa/120 min in both fresh and stored samples 4. Low GSH RBCs induced by diamide in both fresh and stored samples exposed to HBO2 0.3 MPa/120 min |

No damage or abnormality induced by HBO2 over controls | AHA | NCI- PDQ | BMJ evidence | |||

| Level | Class | NA | NA | ||||||||

| 6 | II.b. | ||||||||||

| 7. | 1992 | Young and Burns (54) | Yes | AHA | NCI- PDQ | BMJ evidence | |||||

| Level | Class | 3.iii. | Likely to be beneficial | ||||||||

| 5 | II.b. | ||||||||||

| 8. | 1999 | McLoughlin et al. (55) | 38 y/female | Antepartum hemorrhage with Hgb 2 g/dL 39 day post-bleed discharge Hgb 7.6 g/dL | No | Vitamin B12, EPO, folic acid, iron HBO2 0.3 MPa/90 min TID tapered to BID over 16 days (total 22 HBO2 sessions) |

Yes | AHA | NCI- PDQ | BMJ evidence | |

| Level | Class | 3.iii. | Likely to be beneficial | ||||||||

| 5 | II.b. | ||||||||||

| 9. | 2002 | Hart (56) | 20 y/female (JW) | GSW to left chest with left lung and hemidiaphragm penetration with spleen, left kidney and spinal cord injury Post-op Hct 18 Post-op intestinal perforation Post-op day 28 Hct 22 |

No | EPO HBO2 0.2 MPa/90 min TID tapering to BID for a total of 28 dives |

Yes | AHA | NCI- PDQ | BMJ evidence | |

| Level | Class | 3.iii. | Likely to be beneficial | ||||||||

| 5 | II.b. | ||||||||||

Human case reports and series for use of hyperbaric oxygen therapy in treatment of severe anemia.

When considering the use of HBOT in cases of severe anemia, the clinician should consult a hyperbaric physician specialist to determine whether HBOT would be helpful for the individual patient. Figure 1 demonstrates the treatment course recommended by the UHMS in their 2023 edition of the Hyperbaric Medicine Indications Manual. The patient would undergo HBOT at two–three ATA for 60–90 min with one–two intermittent 5-min air breaks (4).

Figure 1

Flowchart of Severe Anemia.

Discussion

The operational practicality of using HBO as a bridging therapy in a remote non-medical setting was reported in a case of severe exsanguination of a commercial diver while in saturation offshore in the Gulf of Mexico. The patient bled out hemoglobin of 2 g per deciliter acutely when his duodenal artery was eroded by a duodenal ulcer. The requisite decompression to the surface required 3 days. During his recompression, he was kept alive without transfusion by Ringers' D5 solution administered by hypodermoclysis and intermittent HBO breathing periods. At the surface, he was then transfused with intravenous packed red blood cells (58). Many years before, three cases of patients with severe blood loss who each refused transfusion for religious belief were reported in the medical literature. The cases were successfully treated with intermittently administered HBO in the same way at a naval dock in a hyperbaric chamber (50).

High concentrations of continuously administered oxygen have been reported to be deleterious when used in patient's resuscitative management (59, 60). This observation has remained consistent regardless of whether the patients enrolled in clinical trials have had high, normal, or low hemoglobin levels, whether acute or chronic (61). How could HBO provided by ventilation with SEFIO2 of inhaled oxygen of 150%−300% not be deleterious? For one, the inhaled oxygen under these conditions is not continuous but is intermittent, with administered air breaks incorporated during HBOT sessions (62). Additionally, as the series of HBO treatment sessions progresses and the patient's condition improves, the patient becomes increasingly tolerant of the off-oxygen periods. This allows the HBOT to be spread out with longer periods between treatments (49). During the HBO breathing periods, enough oxygen is dissolved in plasma to allow plasma to deliver oxygen to tissue mitochondria to reduce the previously accumulating oxygen debt, which, in effect, is an adenosine triphosphate (ATP) debt (63–66).

One might say that HBOT, as bridge therapy, serves to resuscitate patients much like the bridging function of veno-venous extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (VV-ECMO) during resuscitative support of critically anemic patients with restrictions on red blood cell transfusion. In the instance of intermittent non-invasive HBOT, the patient can similarly be successfully supported (67). By simile, one might compare VV-ECMO to a continuous weld and short-interval intermittent HBOT to a spot weld (in effect, intermittent HBOT is VV-ECMO-like or “ECMoid” in function). Both therapeutic modalities attempt to hold the metabolic structure of the patient together. ECMO has up to a 30% serious adverse side effect incidence (68). Hyperbaric oxygen has, on average, one in 10,000 incidences of serious side effects including pneumothorax, oxygen toxicity seizure, fire or explosion, and arterial gas embolism (69–71). The ECMO hospital facility support fee is often US $50,000 per day (72) and a hospital-based HBOT series of 30 treatments includes a facility charge of US $7,500 (73, 74). In almost all instances, 30 HBOT treatments would be more than enough to bridge a patient through an anemic crisis. In the United States, the cost of a unit of packed red blood cells, along with its administration, is comparable to the cost of one HBOT treatment (4).

The tolerance to high-dose oxygen administration by intermittent application has been well-documented with oxygen administered at one atmosphere pressure as well as at increased atmospheric pressure (62, 75). There is more than just oxygen tolerance provided by the intermittency of use; this is the effect of intermittency itself. ATP resupply occurs when the mitochondrial intermembrane space minimally attains 1.5–2.0 mmHg of oxygen, which is a requisite for the unimpaired production of ATP by the mitochondrial respiratory chain of enzymes (76). In a severely anemic patient, equally important is the return of tissue hypoxia after the completion of an HBOT treatment. It is hypoxia that incites ATP-dependent reparative cytokine tissue release and antioxidant production. For the reparative and anti-inflammatory cytokines to work at cellular receptor sites, ATP is needed. The anteceding HBOT would have supplied the needed ATP for this to occur. The ensuing tissue hypoxia between treatments induces the following energy-dependent or ATP-dependent activity:

-

Antioxidant productions and functions to include catalase and peroxidase (77), glutathione (78), superoxide dismutase (79), and ATP itself as an antioxidant (80).

-

Support of genomic activity (81).

-

Support of epigenomic activity (82).

-

Support of proteomic activity (83) and protein folding (84).

-

Support of lipidomic activity (85).

-

Support of anti-inflammatory and reparative cytokines/chemokines (86).

-

Adaptive function in hypoxia: (erythropoietin) (89, 90) (heat shock protein) (91) (nitric oxide) (92) (hypoxia-inducible factor) (93).

This oscillation between hyperoxia and hypoxia may be graphically depiected as a sinusoidal timeline by Figure 2 and is the crux of the oxygen paradox.

Figure 2

The sinusoidal horizontal timeline depicted by the thick wavy lines in the diagram represents an intermittent hyperbaric oxygen treatment course. The wave peaks represent a hyperbaric oxygen treatment producing ATP resupply (93). Post treatment when the tissue oxygen tension drops, energy requiring cytokine and antioxidant release occurs (85).

To provide ATP resupply in the instance of an acute hypoxic state, pulsed high-dose HBO inhalation can be used to diffuse minimally 1.5–2.0 mmHg of oxygen into the mitochondrial intermembrane space (94). At best, when a red blood cell gets to its destination in capillaries, it must offload a portion of its remaining oxygen content back into the plasma. As the patient inhales 100% oxygen at one atmosphere of pressure, the plasma can maximally contain only 2.3 volumes% of dissolved oxygen. In contrast, the patient in a hyperbaric chamber at three atmospheres of pressure would inhale a SEFIO2 of 300%, thereby delivering to the capillaries 6.6 volume% of dissolved oxygen with a five-fold diffusion distance outside of the capillary over that of a subject inhaling an FIO2 of 100% oxygen at one atmosphere of pressure (95–97). This concept was reported over 60 years ago by W. Brummelkamp when he reported that during an HBOT treatment, “drenching of the tissue with dissolved oxygen” occurred by way of immersing plasma with oxygen (98).

HBOT inhalation can only be accomplished safely when the entire patient is pressurized above ambient pressure in an enclosure (i.e., a hyperbaric chamber). The spectrum of potential treatment doses of oxygen using HBO pressure incorporates the pharmacologic effect of the gases at increased pressure and the physiologic effect of pressure itself (99).

A measure of the safety of HBO can best be described by Pascal's Law, where in a confined space, any contained fluid will transmit the pressure evenly throughout the fluid non-destructively. The human skin envelope contains the fluid of all the body's tissue (gas is not a problem in sinus spaces if vented by an open ostia and in the middle ear if vented by a patient's functioning Eustachian tube) (100). By virtue of the principle of Pascal's law, a patient may be ventilated without barotrauma by pressurized gas at the same pressure as that of hyperbaric chamber pressurization. Ventilators have been developed to do this safely, and chambers can be fitted with all the functions of critical care hospital units (101, 102).

Henry's Gas Law states that the concentration of a solute gas in a solution is directly proportional to the partial pressure of the gas over the solution. Inhalation of HBO at three atmospheres of pressure allows enough dissolved oxygen (6.6 volumes%) in plasma to supply the metabolic extraction rate of most of the tissue in a human body at rest (103).

The operational safety of hyperbaric medicine units has evolved through adherence to developing safety guidelines. This has allowed a remarkable safety record for hospital-based units for equipment, patients, and healthcare providers for both multiplace and monoplace chamber facilities (104, 105).

At the 21% oxygen content of air in one atmosphere, hemoglobin makes up for plasma's inability to deliver adequate oxygen to tissue. This is because a subject breathing air would have, at maximum, a 0.48 volume% of plasma dissolved oxygen, which clearly would not be enough to support human life (0.003 ml × 21% × 760 mmHg, where 0.003 ml is the amount at one atmosphere of oxygen dissolved in plasma for each mmHg of pressure, 21% is the oxygen content of air, and 760 mmHg is the pressure for each mmHg of pressure in the atmosphere at sea level) (106). Using the same equation for breathing 100% oxygen at one atmosphere, the maximum amount of dissolved oxygen in plasma would be 2.3 volume%. As mentioned, this would be far below the average oxygen extraction rate of most human tissue with the body at rest. To get around this problem, hemoglobin serves as a powerful gas clathrate, especially for oxygen. When a red blood cell picks up oxygen in the lung and discharges it in the periphery, the maximum oxygen conceivably dissolved in plasma would be 2.3 volume% at both ends of the line.

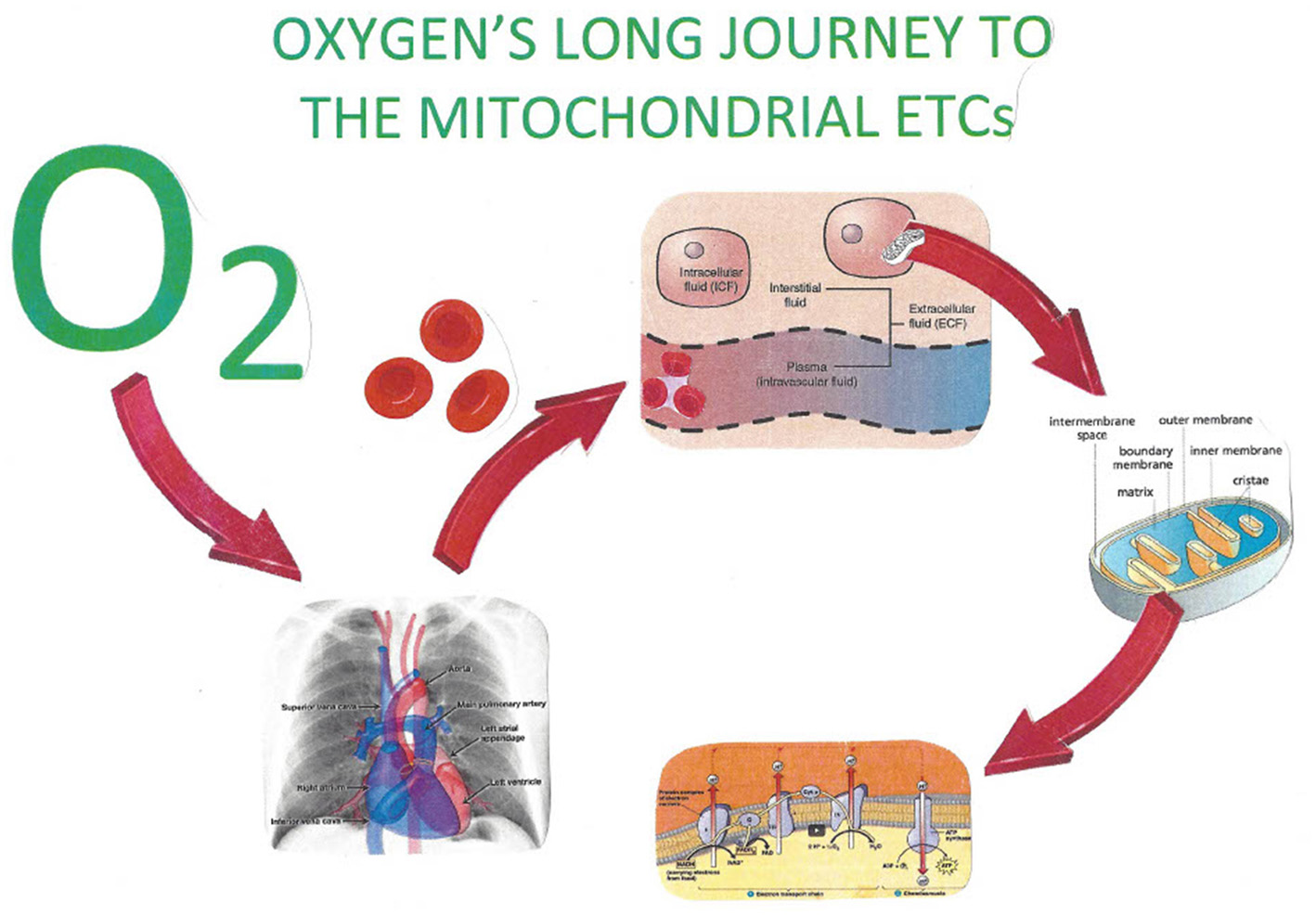

Plasma delivers the oxygen from the red blood cells to the endothelium, where it diffuses into the interstitial fluid, then diffuses through cellular membranes into the cytosol, and finally passes into the intermembrane space (IMS) of mitochondria. HBO administered at three atmospheres of pressure (SEFIO2 300%) allows 6.6 volume% of oxygen to be dissolved in plasma. It is this concentration that begins its journey by diffusion through the capillary endothelium, ultimately filling the IMS of mitochondria minimally with the 1.5–2.0 mmHg of dissolved oxygen requisite for the electron transport chain along with ATP synthase to produce ATP (107). Figures 3, 4 demonstrate this process.

Figure 3

The most oxygen that can conceivably be dissolved in plasma by a subject who breathes 100% oxygen is 2.3 volume%, and the plasma level enters the red blood cells in the lung capillary, where the blood content can be boosted as high as 20 volume% by the presence of the gas-clathrate-like function of hemoglobin. When the red blood cell gets to its destination in a capillary of distant tissue, the highest possible concentration as the oxygen unloads from the red blood cell into the plasma possible at normobaric pressure is again at the very highest, 2.3 volume%. Under hyperbaric conditions at three atmospheres of pressure, the equivalent amount of oxygen possible in plasma during the circulatory route all the way to distal capillaries at the very highest would be 6.6 volume% (108).

Figure 4

The increased ability of hyperbaric oxygen allows for an increased quantity of dissolved oxygen in body fluids. The facilitated delivery of oxygen thereby to the IMS of mitochondria throughout the body provides for necessary oxidative phosphorylation. Oxygen, by attaching to the cytochrome 3 oxidase enzyme of the mitochondrial electron transport chain, produces the necessary supply of hydronium ions for ATP.

The increased diffusivity of oxygen in tissue afforded by hyperbaric pressure is important. Krogh has described the diffusion distance of oxygen from plasma through the capillary endothelium (95, 97). This has been further expounded upon to include the added effect of the diffusivity of oxygen in the hyperbaric environment (99) as demonstrated in Figure 5.

Figure 5

Krogh calculated the diffusion distance of oxygen outside of capillaries into tissue when a human breathed normobaric air. Extrapolation incorporating three atmospheres of pressure provided by hyperbaric treatment would provide a fivefold improvement in diffusion distance (94, 110).

Tissue oxygen capacitance increases during and after an HBOT treatment. The oxygen that is onloaded into the tissue during HBOT is, in part, slowly off-gassed, much like an inert gas with tissue elimination half-lives supplemented by the additional elimination of oxygen by metabolic consumption (109). Furthermore, some oxygen is retained in tissue by attaching to cellular gas clathrates [i.e., neuroglobin (110), cytoglobin (111), and myoglobin (112)]. With serial HBOT treatment, tissue oxygen capacitance increases (113).

The red blood cell, as a biconcave disk, has a shape that maximizes its surface area. As a short-lived bag of hemoglobin, the mature red blood cell does not have mitochondria or a nucleus. An important mission of the red blood cell is to overcome the poor solubility of oxygen in plasma at one atmosphere in order to adequately get a supply of oxygen to mitochondria. The use of HBOT, especially in remote settings, has compelled some tertiary urban trauma medical staff to consider the development of a hyperbaric ambulance to mimic the success of the deck decompression chambers on operational sites to address injury of commercial divers (114). Figure 6 demonstrates this point.

Figure 6

Having a hyperbaric ambulance to bring immediate hyperbaric oxygen treatment to severely anemic, injured, or ill patients in transit to a hospital emergency department increases the chance of having the same success rate as commercial diving operations, which require a hyperbaric chamber on site for accidents.

A consideration of the potential toxic properties of a prolonged administration of O2 in almost all cases under normobaric, hyperbaric, or hypobaric exposures is a certainty (115–117). A judicious use of short-tie exposures of 60–90 min with intermittency of 5 min air breaks during administration and with gradual spreading of time intervals between treatments has thoroughly been documented to be safe, allowing the “hyperoxic–hypoxic paradox” prevail to the patient's benefit (118–120).

Conclusion

Red blood cells play an important role in the chain of oxygen delivery to the mitochondrial IMS. Finally, in the IMS, oxygen attaches to cytochrome c oxidase in the electron transport chain of enzymes embedded in the inner IMS (121). Reacting with the oxygen and hydrogen ions, cytochrome c oxidase expels the by-product of water. The hydrogen ions in the IMS fall down the molecular shoot of the ATP synthase nanomachine, and by rotary catalysis, Pi ions join with ADP to form ATP. It is an evolutionary wonder that the red blood cell without mitochondria carts oxygen to mitochondria in all the body's cells to provide the energy for the homeostasis of life.

HBOT, if used promptly, can serve as a bridge therapy to alleviate illness and injury when transfusion of red blood cells is necessary, otherwise requiring massive transfusion protocols. In other instances, HBOT could address severely anemic patients burdened with complicating comorbidities that otherwise would preclude the desirability of transfusion of red blood cells in any amount or by transfusion altogether. Hypoxic stress simulates recovery, and recovery requires energy provided by ATP.

Emerging ways that HBOT can safely and quickly be available are currently in existence (122). Hyperbaric units can be parts of emergency departments (123), intensive care units (124), and ambulances (114). Figure 7 shows schematics for a designed hyperbaric ambulance. The cost of an HBOT treatment is equal to the cost of a unit of blood and its administration (4). HBOT does not need type and crossing, or IV access, as the systemic dose of oxygen is administered via breathing or through a patient ventilator.

Figure 7

The best of all possibilities would be to have a hyperbaric ambulance system that deploys to the street to transport a severely anemic, ill, or injured patient under pressure with oxygen administration. Upon arrival at the hospital, the pressurized patient compartment would hydraulically depart the ambulance chaise and roll into the hospital emergency department to continue conventional normobaric resuscitation. The option could be for the detached patient compartment of the ambulance to mate with a hyperbaric intensive care multiplace chamber for continued hyperbaric resuscitation (113).

Statements

Author contributions

KV: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1.

Boerema I Meyne NG Brummelkamp WK Mensch MH Kamermans F Stern Hanf M et al . Life without blood: a study of the influence of high atmospheric pressure and hypothermia on dilution of the blood. J Cardiovasc Surg. (1960) 1:133–46.

2.

Maloney-Wilensky E Le Roux P . The physiology behind direct oxygen monitors and practical aspects of their use. Childs Nerv Syst. (2010) 26:419–30. 10.1007/s00381-009-1037-x

3.

Van Meter K . Hyperbaric oxygen use in exceptional blood loss anemia. In: WhelanHTKindwallEP editors. Hyperbaric Medicine Practice, 4th Edn. North Palm Beach, FL: Best Publishing (2017), p. 691–705.

4.

Van Meter K . Severe anemia. In: HuangET editor. Undersea and Hyperbaric Medical Society Hyperbaric Medicine Indications Manual, 15th Edn. North Palm Beach, FL: Best Publishing Company (2023), p. 295–304.

5.

Frank HA Fine J . Traumatic shock V: a study of the effect of oxygen on hemorrhagic shock. J Clin Invest. (1943) 22:305–14. 10.1172/JCI101396

6.

Wiggers CJ Werle JM . Exploration of method for standardizing hemorrhagic shock. Proc Soc Exper Biol Med. (1942) 49:601. 10.3181/00379727-49-13645

7.

Burnet W Clark RG Duthie HL Smith AN . The treatment of shock by oxygen under pressure. Scot Med J. (1959) 4:535–8. 10.1177/003693305900401105

8.

Boerema I Meyne NG Brummelkamp WH Bouma S Mensch MH Kamermans F et al . Life without blood. Arch Chir Neerl. (1959) 11:70–84.

9.

Attar S . Esmond WH, Cowley RA. Hyperbaric oxygenation in vascular collapse. J Thoracic Cardiovasc Surg. (1962) 44:759–70. 10.1016/S0022-5223(19)32911-3

10.

Cowley RA Attar S Esmond WJ Blair E Hawthorne I . Electrocardiographic and biochemical study in hemorrhagic shock in dogs treated with hyperbaric oxygen. Circulation. (1963) 27:670–5. 10.1161/01.CIR.27.4.670

11.

Blair E Henning G Esmond WG Attar S Cowley RA Michaelis M . The effect of hyperbaric oxygenation (OHP) on three forms of shock – traumatic, hemorrhagic, and septic. J Trauma. (1964) 4:652–63. 10.1097/00005373-196409000-00009

12.

Clark RG Young DG . Effects of hyperoxygenation and sodium bicarbonate in hemorrhagic hypotension. Brit J Surg. (1965) 52:704–8. 10.1002/bjs.1800520918

13.

Cowley RA Attar S Blair E Esmond WG Michaelis M Olloartr . Prevention and treatment of shock by hyperbaric oxygenation. Ann NY Acad Sci. (1965) 117:673–83. 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1964.tb56314.x

14.

Elliot DP Paton BC . Effect of 100% oxygen at 1 and 3 atmospheres on dogs subjected to hemorrhagic hypotension. Surgery. (1965) 57:401–8.

15.

Attar S Scanlan E Cowley RA . Further evaluation of hyperbaric oxygen in hemorrhagic shock. In: BrownIWCoxB, editors. Proceedings of the Third International Congress on Hyperbaric Medicine.Washington DC: NAS/NRC (1965), p. 417–24.

16.

Jacobson YG Keller MI Mundth ED DeFalco AJ McClenehan JE . Hyperbaric oxygen therapy in experimental hemorrhagic shock. In: BrownIWCoxB, editors. Proceedings of the third international congress on hyperbaric medicine. Washington DC: NAS/NRC (1965), p. 93–6.

17.

Jacobson YG Keller MI Mundth ED Defalco AJ McClenethan JE . Hemorrhagic shock: influence of hyperbaric oxygen on metabolic parameters. Calif Med. (1966) 105:93–6.

18.

Whalen RE Moor GF Mauney FM Brown IW McIntosh HD . Hemodynamic responses to “Life without blood.” In: BrownIWCoxB, editors. Proceedings of the Third International Congress on Hyperbaric Medicine. Washington DC: NAS/NRC (1965), p. 402–8.

19.

Navarro RU Ferguson CC . Treatment of experimental hemorrhagic shock by the combined use of hyperbaric oxygen and low-molecular weight dextran. Surg. (1968) 63:775–81.

20.

Necas E Neuwirt J . Lack of erythropoietin in plasma of anemic rats exposed to hyperbaric oxygen. Life Sci. (1969) 8:1221–8. 10.1016/0024-3205(69)90178-7

21.

Doi Y Onji Y . Oxygen deficit in hemorrhagic shock under hyperbaric oxygen. In: WadaJIwaJT, editors. Proceedings of the fourth international congress on hyperbaric oxygen. Baltimore, MD: Williams and Wilkins (1970), p. 181–4.

22.

Oda T Takeori M . Effect of viscosity of the blood on increase in cardiac output following acute hemodilation. In: WadaJIwaJT, editors. Proceedings of the Fourth International Congress on Hyperbaric Oxygen. Baltimore, MD: Williams and Wilkins (1970), p. 191–6.

23.

Trytyshnikov IM . Effect of acute massive blood loss during hyperbaric oxygen therapy on nucleic and metabolism in the albino rat liver. Biull Eksp Biol Med. (1974) 77:611–2. 10.1007/BF00789978

24.

Norman JN . Hemodynamic studies in total blood replacement. Biblio Haema. (1975) 41:203–8. 10.1159/000398118

25.

Barkova EN Petrov AV . The effect of oxygen barotherapy on erythropoiesis in the recuperative period following hemorrhagic collapse. Biull Eksp Bio Med. (1976) 81:156–8. 10.1007/BF00801054

26.

Luenov AN Takovlev VN . Role of cerebral nitrogen metabolism in the mechanisms of the therapeutic action of oxygen under elevated pressure in hemorrhagic shock. Biull Eksp Biol Med. (1977) 83:418–20. 10.1007/BF00807483

27.

Gross DR Moreau PM Jabor M Welch DW Fife WP . Hemodynamic effects of dextran-40 on hemorrhagic shock during hyperbaria and hyperbaric hyperoxia. Aviat Space Environ Med. (1983) 54:413–9.

28.

Gross DR Moreau PM Chaikin BN Welch DW Jabor M Fife WP . Hemodynamic effects of lactated Ringers' solution on hemorrhagic shock during exposure to hyperbaric air and hyperbaric hyperoxia. Aviat Space Environ Med. (1983) 54:701–8.

29.

Gross DR Dodd KT Welch KW Fife WP . Hemodynamic effects of 10% dextrose and of dextran-70 on hemorrhagic shock during exposure to hyperbaric air and hyperbaric hyperoxia. Aviat Space Environ Med. (1984) 55:1118–28.

30.

Bitterman H Reissman P Bitterman N Melamed Y Cohen L . Oxygen therapy in hemorrhagic shock. Circ Shock. (1991) 33:183–91.

31.

Wen-Ren L . Resection of aortic aneurysms under 3 ATA of hyperbaric oxygenation. In: BakkerDJCramerJS, editors. Proceedings of the Tenth International Congress of Hyperbaric Medicine. Flagstaff, AZ: Best Publishing Co (1992), p. 94–5.

32.

Marzella L Yin A Darlington D et al . Hemodynamic responses to hyperbaric oxygen administration in a cat model of hemorrhagic shock. Circ Shock. (1992) 37:12.

33.

Adir Y Bitterman N Katz E Melamed Y Bitterman H . Salutary consequences of oxygen therapy or long-term outcome of hemorrhagic shock in awake, unrestrained rats. Undersea Hyperb Med. (1995) 22:23–30.

34.

Yamashita M Yamashita M . Hyperbaric oxygen treatment attenuates cytokine induction after massive hemorrhage. Am J Physiol Endocrin Metab. (2000) 278:E811–6. 10.1152/ajpendo.2000.278.5.E811

35.

Van Meter K . Hyperbaric oxygen therapy as an adjunct to pre-hospital advanced trauma life support. Surg Technol Int. (2011) 21:61–73.

36.

Graffeo C Dishong W . Severe blood loss anemia in a Jehovah's Witness treated with adjunctive hyperbaric oxygen therapy. Am J Emerg Med. (2013) 31:756e3–4. 10.1016/j.ajem.2012.11.013

37.

Weaver LK Hopkins RO Chan KJ Churchill S Elliott CG Clemmer TP et al . Hyperbaric oxygen for acute carbon monoxide poisoning. N Engl J Med. (2002) 347:1057–67. 10.1056/NEJMoa013121

38.

Takano T Miyazaki Y Nashimoto I Kobayashi K . Effect of hyperbaric oxygen on cyanide intoxication: in situ changes in intracellular oxidation reduction. Undersea Biomed Res. (1980) 7:191–7.

39.

Hansen MB Olson NV Hyldegaard O . Combined administration of hyperbaric oxygen and hydroxocobalamin improves cerebral metabolism after acute cyanide poisoning in rats. J Appl Physiol. (2013) 115:1254–61. 10.1152/japplphysiol.00516.2013

40.

Hanley ME Murphy-Lavoie HM . Hyperbaric Evaluation and Treatment of Cyanide Toxicity. Treasure Island, FL: StatPearls Publishing (2023).

41.

Smilkstein MJ Bronstein AC Pickett HM Rumack BH . Hyperbaric oxygen therapy for severe hydrogen sulfide poisoning. J Emerg Med. (1985) 3:27–30. 10.1016/0736-4679(85)90216-1

42.

Van Meter KW . A systematic review of the application of hyperbaric oxygen in the treatment of severe anemia: an evidence-based approach. Undersea Hyperb Med. (2005) 32:61–83.

43.

Rogatsky GG Shifrin EG Mayevsky A . Acute respiratory distress syndrome in patients after blunt thoracic trauma: the influence of hyperbaric oxygen therapy. Adv Exp Med Biol. (2003) 540:77–85. 10.1007/978-1-4757-6125-2_12

44.

Cannellotto M Duarte M Keller G Larrea R Cunto E Chediack V et al . Hyperbaric oxygen as an adjuvant treatment for patients with COVID-19 severe hypoxaemia: a randomised, controlled trial. Emerg Med J. (2002) 39:88–93. 10.1136/emermed-2021-211253

45.

Senniappan K Jeyabalan S Rangappa P Kanchi M . Hyperbaric oxygen therapy: can it be a novel supportive therapy in COVID-19?Indian J Anaesth. (2020) 64:835–41. 10.4103/ija.IJA_613_20

46.

Koch A Kahler W Klapa S Grams B van Ooij PAM . The conundrum of using hyperoxia in COVID-19 treatment strategies: may intermittent therapeutic hyperoxia play a helpful role in the expression of the surface receptors ACE2 and furin in lung tissue via triggering of HIF-1a. Intensive Care Med Exp. (2020) 8:53. 10.1186/s40635-020-00323-1

47.

Tao Z Xu J Chen W Yang Z Xu X Liu L et al . Anemia is associated with severe illness in COVID-19: a retrospective cohort study. J Med Virol. (2021) 93:1478–88. 10.1002/jmv.26444

48.

Ledingham IM . Hyperbaric oxygen in shock. Int Anes Clin. (1969) 7:819–39. 10.1097/00004311-196907040-00007

49.

Amonic RS Cockett ATK Lonhan PH Thompson JC . Hyperbaric oxygen therapy in chronic hemorrhagic shock. JAMA. (1969) 208:2051–4. 10.1001/jama.208.11.2051

50.

Hart GB . Exceptional blood loss anemia: treatment with hyperbaric oxygen. JAMA. (1974) 228:1028–9. 10.1001/jama.228.8.1028

51.

Myking O Schreinen A . Hyperbaric oxygen in hemolytic crisis. JAMA. (1974) 227:1161–2. 10.1001/jama.227.10.1161

52.

Hart GB . Lennon PA, Strauss MB. Hyperbaric oxygen in exceptional acute blood loss anemia. J Hyperbar Med. (1987) 2:205–10.

53.

Meyerstein N Mazor D Tsach T et al . Resistance of human red blood cells to hyperbaric oxygen under therapeutic conditions. J Hyperbar Med. (1989) 4:1–5.

54.

Young BA Burns JR . Management of the severely anemic Jehovah's Witness. Ann Int Med. (1992) 119:170. 10.7326/0003-4819-119-2-199307150-00020

55.

McLoughlin PL Cope TM Harrison JC . Hyperbaric oxygen therapy in management of severe acute anemia in a Jehovah's witness. Anesthesia. (1999) 54:891–5. 10.1046/j.1365-2044.1999.01004.x

56.

Hart GB . Hyperbaric oxygen and exceptional blood loss anemia. In: KindwallEPWhelanHT, editors. Hyperbaric Medicine Practice, 2nd Edn. Flagstaff, AZ: Best Publishing Co. (2002), p. 741–51.

57.

Ueno S Sakoda M Kurahara H Iino S Minami K Ando K et al . Safety and efficacy of early postoperative hyperbaric oxygen therapy with restriction of transfusions in patients with HCC who have undergone partial hepatectomy. Langenbecks Arch Surg. (2011) 396:99–106. 10.1007/s00423-010-0725-z

58.

Van Meter KW . Hyperbaric oxygen in resuscitation. In: JainKK, editor. Textbook of Hyperbaric Medicine. New York, NY: Springer International (2017), p. 551–66. 10.1007/978-3-319-47140-2_42

59.

Hafner S . Beloncle F, Koch A, Radermacher P, Asfar P. Hyperoxia in intensive care, emergency and peri-operative medicine: Dr. Jekyll or Mr. Hyde? A 2015 update. Ann Intensive Care. (2015) 5:42. 10.1186/s13613-015-0084-6

60.

Schmidt H Kjaergaard J Hassager C Mølstrøm S Grand J Borregaard B et al . Oxygen targets in comatose survivors of cardiac arrest. N Engl J Med. (2022) 387:1467–76. 10.1056/NEJMoa2208686

61.

Llitjos JF Mira JP Duranteau J Cariou A . Hyperoxia toxicity after cardiac arrest: what is the evidence?Ann Intensive Care. (2016) 6:23. 10.1186/s13613-016-0126-8

62.

Hendricks PL Hall DA Hunter WL Haley PJ . Extension of pulmonary oxygen tolerance in man at 2 ATA by intermittent oxygen exposure. J Appl Physiol Respir Environ Exerc Physiol. (1977) 42:593–9. 10.1152/jappl.1977.42.4.593

63.

Balestra C Germonpre P Poortmans JR Marroni A . Serum erythropoietin levels in healthy humans after a short period of normobaric and hyperbaric oxygen breathing: the “normobaric oxygen paradox”. J Appl Physiol. (2006) 100:512–8. 10.1152/japplphysiol.00964.2005

64.

Van Meter KW . Hyperbaric oxygen and exceptional blood loss anemia. In: KindwallEPWhelenHT, editors. Hyperbaric Medicine Practice.Flagstaff, AZ: Best Publishing (2002), p. 741–51.

65.

Shoemaker WC Appel PL Kram HB . Tissue oxygen debt as a determinant of lethal and nonlethal postoperative organ failure. Crit Care Med. (1988) 16:1117–20. 10.1097/00003246-198811000-00007

66.

Van Meter KW . Hyperbaric oxygen clinical application in resuscitation from insult from acute severe anemia. Wound Care Hyperbar Med. (2014) 5:27–32.

67.

Vaquer S de Haro C Peruga P Oliva JC Artigas A . Systematic review and meta-analysis of complications and mortality of veno-venous extracorporeal membrane oxygenation for refractory acute respiratory arrest distress syndrome. Ann Intensive Care. (2017) 7:51–64. 10.1186/s13613-017-0275-4

68.

Heyboer M Sharma D Santiago W McCulloch N . Hyperbaric oxygen therapy: side effects defined and quantified. Advan Wound Care. (2017) 6:210–24. 10.1089/wound.2016.0718

69.

Camporesi EM . Side effects of hyperbaric oxygen therapy. Undersea Hyperb Med. (2014) 41:253–57.

70.

Plafki C Peters P Avmeling M Welslau W Busch R . Complications and side effects of hyperbaric oxygen therapy. Aviat Space Environ Med. (2000) 71:119–24.

71.

Hayanga JWA Aboagye J Bush E Canner J Hayanga HK Klingbeil A et al . Contemporary analysis of changes and mortality in the use of extracorporeal membrane oxygenation: a cautionary tale. HTCVS Open. (2020) 1:61–70. 10.1016/j.xjon.2020.02.003

72.

Gomez-Castillo JD Bennett MH . The cost of hyperbaric therapy at the Prince of Wales Hospital, Sidney. SPUMS J. (2005) 35:194–8.

73.

Hajhosseini B Kuehlmann BA Bonham CA Kamperman KJ Gurtner GC . Hyperbaric oxygen therapy: descriptive review of the technology and current application in chronic wounds. Plast Reconstr Surg Glob Open. (2020) 8:e3136. 10.1097/GOX.0000000000003136

74.

Wojan F Stray-Gundersen S Nagel MJ Lalande S . Short exposure to intermittent hypoxia increases erythropoietin level in healthy individuals. J Appl Physiol. (2021) 130:1955–60. 10.1152/japplphysiol.00941.2020

75.

Waypa GB Smith KA Schumacker PT . Oxygen sensing, mitochondria, and ROS signaling: the fog is lifelong. Mol Aspects Med. (2016) 47–48:76–89. 10.1016/j.mam.2016.01.002

76.

Avashalumov MV Chen BT Koos T Tepper JM Rice ME . Endogenous hydrogen peroxide regulates the excitability of midbrain dopamine neurons via ATP-sensitive potassium channels. J Neurosci. (2005) 25:4222–31. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4701-04.2005

77.

Ribas V Garcia Ruiz C Fernandez-Checa JC . Glutathione and mitochondria. Front Pharmacol. (2014) 5:151. 10.3389/fphar.2014.00151

78.

Chen HB Chan YT Hung AC Tsai YC Sun SH . Elucidation of ATP-stimulated stress protein expression of RBA-2 type-2 astrocytes: ATP potentiate HSP60 and Cu/Zn S0D expression and stimulates pI shift of peroxiredoxin II. J Cell Biochem. (2006) 97:314–26. 10.1002/jcb.20547

79.

Shi Y Tang M Sun C Pan Y Liu L Long Y Zheng Z . ATP mimics pH-dependent dual peroxidase-catalase activities driving H2O2 decomposition. CCS Chem. (2019) 1:373–83. 10.31635/ccschem.019.20190017

80.

Hargreaves DC Crabtree GR . ATP-dependent chromatin remodeling: genetics, genomics, and mechanisms. Cell Res. (2011) 21:396–420. 10.1038/cr.2011.32

81.

Runge JS Raab JR Magnuson T . Epigenetic regulation by ATP-dependent chromatin remodeling enzymes: SNF-ing out crosstalk. Curr Top Dev Biol. (2016) 117:1–13. 10.1016/bs.ctdb.2015.10.009

82.

Jewatt M Miller ML Chen Y Swartz JR . Continued protein synthesis at low [ATP] and [GTP] enables cell adaptation during energy limitation. J Bacteriol. (2009) 191:1083–91. 10.1128/JB.00852-08

83.

Ou X Lao Y Xu J Wutthinitikornkit Y Shi R Chen X et al . ATP can efficiently stabilize protein through a unique mechanism. JACS Au. (2021) 1:1766–77. 10.1021/jacsau.1c00316

84.

Verma DD Levchenko TS Bernstein EA Torchilin VP . ATP-loaded liposomes effectively protect mechanical functions of the myocardium from global ischemia in an isolated rat heart model. J Control Release. (2005) 108:460–71. 10.1016/j.jconrel.2005.08.029

85.

Mo Y Sarojini H Wan R Zhang Q Wang J Eichenberger S et al . Intracellular ATP delivery causes rapid tissue regeneration via upregulation of cytokines, chemokines and stem cells. Front Pharmacol. (2020) 10:1502. 10.3389/fphar.2019.01502

86.

Eltzchig HK Eckle T Mager A Küper N Karcher C Weissmüller T et al . ATP release from activated neutrophils occurs via connexin 43 and modulates adenosine-dependent endothelial cell function. Circ Res. (2006) 99:1100–8. 10.1161/01.RES.0000250174.31269.70

87.

Thom SR Mendiguren I Hardy K Bolotin T Fisher D Nebolon M et al . Inhibition of human neutrophil beta-2-ntegrin-dependent adherence by hyperbaric oxygen. Am J Physiol. (1997) 272:C770–7. 10.1152/ajpcell.1997.272.3.C770

88.

Yilmaz TU Yazihan N Dalgic A Kaya EE Salman B Kocak M et al . Role of ATP-dependent K channels in the effects of erythropoietin in renal ischaemia injury. Indian J Med Res. (2015) 141:807–15. 10.4103/0971-5916.160713

89.

Goto T Ubukawa I Kobayashi I Sugawara K Asanuma K Sasaki Y et al . ATP produced by anaerobic glycolysis is essential for enucleation of human erythroblasts. Exp Hematol. (2019) 72:14–26.e1. 10.1016/j.exphem.2019.02.004

90.

Mallouk Y Vayssier-Tassat M Bonventre JV Polla BS . Heat shock protein 70 and ATP as partners in cell homeostasis. Int J Mol Med. (1999) 4:463–74. 10.3892/ijmm.4.5.463

91.

Brown GC Borutaite V . Nitric oxide and mitochondrial respiration in the heart. Cardiovas Res. (2007) 75:283–90. 10.1016/j.cardiores.2007.03.022

92.

Cerychova R Pavlinkova G . HIF-1, metabolism, and diabetes in the embryonic and adult heart. Front Endocrinol. (2018) 9:460. 10.3389/fendo.2018.00460

93.

Wilson DF Erecinska M Drown C Silver IA . The oxygen dependence of cellular energy metabolism. Arch Biochem Biophys. (1979) 195:485–93. 10.1016/0003-9861(79)90375-8

94.

Krogh A . The number and distribution of capillaries in muscles with calculations of the oxygen pressure head necessary for supplying the tissue. J Physiol. (1919) 52:409–15. 10.1113/jphysiol.1919.sp001839

95.

Tissue oxygen measurements . In: DavidJCHuntTK editors. Problem Wounds: The Role of Oxygen. New York, NY: Elsevier Science Publishing (1977), p. 17–51.

96.

Brummelkamp WH Hogendijk J Boerema I . Treatment of anaerobic infections (clostridial myositis) by drenching the tissues with oxygen under high atmospheric pressure. Surg. (1961) 49:299–302.

97.

Gjedde A . Diffusive insights: on the disagreement of Christian Bohr and August Krogh at the Centennial of the Seven Little Devils. Adv Physiol Educ. (2010) 34:174–85. 10.1152/advan.00092.2010

98.

Harch PG . New scientific definitions: hyperbaric therapy and hyperbaric oxygen therapy. Med Gas Res. (2023) 13:92–3. 10.4103/2045-9912.356475

99.

O'Neill OJ Smykowski E Marker JA Perez L Gurash S Sullivan J . Proof of concept study using modified Politzer inflation device as a rescue modality for treating Eustachian tube dysfunction during hyperbaric oxygen treatment in a multiplace (Class A) chamber. Undersea Hyperb Med. (2019) 46:55–61. 10.22462/01.03.2019.6

100.

Kronlund P Lind F Olsson D . Hyperbaric critical care patient data management system. Diving Hyperb Med. (2012) 42:85–7.

101.

Bessereau J Aboab J Hullin T Huon-Bessereau A Bourgeois JL Brun PM et al . Safety of hyperbaric oxygen therapy in mechanically ventilated patients. Int Marit Health. (2017) 68:46–51. 10.5603/IMH.2017.0008

102.

Nichols D Nielsen ND . Oxygen delivery and consumption: a macrocirculatory perspective. Crit Care Clin. (2010) 26:239–53. 10.1016/j.ccc.2009.12.003

103.

Clarke R . Monoplace chamber treatment of decompression illness: review and commentary. Diving Hyperb Med. (2020) 50:264–72. 10.28920/dhm50.3.264-272

104.

Clarke R . Health care worker decompression sickness: incidence, risk and mitigation. Undersea Hyperb Med. (2017) 44:509–19. 10.22462/11.12.2017.2

105.

McLellan SA Walsh TS . Oxygen delivery and hemoglobin. Cont Educ in Anaes Crit Care Pain. (2004) 4:123–6. 10.1093/bjaceaccp/mkh033

106.

Mik EG Balestra GM Harms FA . Monitoring mitochondrial pO2: the next step. Curr Opin Crit Care. (2020) 26:289–95. 10.1097/MCC.0000000000000719

107.

Tzameli I . The evolving role of mitochondria in metabolism. Trends Endocrinol Metab. (2012) 23:417–9. 10.1016/j.tem.2012.07.008

108.

Tornroth-Horsefield S Neutz R . Opening and closing the metabolite gate. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. (2008) 105:19565–6. 10.1073/pnas.0810654106

109.

Burmester T Hankeln T . Neuroglobin: a respiratory protein of the nervous system. News Physiol Sci. (2004) 19:110–3. 10.1152/nips.01513.2003

110.

Yoshizato K Thuy LTT Shiota G Kawata N . Discovery of cytoglobin and its roles in physiology and pathology of hepatic stellate cells. Proc Jpn Acad Ser B Phys Biol Sci. (2016) 92:77–87. 10.2183/pjab.92.77

111.

Endeward V Gros G Jurgens KD . Significance of myoglobin as an oxygen store and oxygen transporter in the intermittently perfused heart: a model study. Cardiovas Res. (2010) 87:22–9. 10.1093/cvr/cvq036

112.

Siddiqi A Davidson JD Mustoe TA . Ischemic tissue oxygen capacitance after hyperbaric oxygen therapy: a new physiologic concept. Plast Resconst Surg. (1992) 99:148–55. 10.1097/00006534-199701000-00023

113.

Van Meter KW . Hyperbaric transport: New Orleans could host the first hyperbaric ambulance concept. Underwater. (2021) 2:16−9.

114.

Leveque C Mrakic-Sposta S . Lafere, Vezzoli A, Germonpré P, Beer A, et al. Oxidative stress response's kinetics after 60 minutes at different (30% or 100%) normobaric hyperoxia exposures. Int J Mol Sci. (2022) 24:664. 10.3390/ijms24010664

115.

Leveque C Sposta SM Theunissen S Germonpré P Lambrechts K Vezzoli A . et al. Oxidative stress response kinetics after 60 minutes at different (14 ATA and 25 ATA) hyperbaric hyperoxia exposures. Int J Mol Sci. (2023) 23:12361. 10.3390/ijms241512361

116.

Leveque C . Mrakic-Sposta S, Theunissen S, Theunissen S, Germonpré P, Lambrechts K, et al. Oxidative stress response kinetics after 60 minutes at different levels (10% or 15%) of normobaric hypoxia exposure. Int J Mol Sci. (2023) 24:10188. 10.3390/ijms241210188

117.

Hadanny A Efrati S . The hyperoxic-hypoxic paradox. Biomolecules. (2020) 10:958. 10.3390/biom10060958

118.

Lafere P Schubert T De Bels D Germonpré P Balestra C . Can the normobaric oxygen paradox (NOP) increase reticulocyte count after traumatic hip surgery?J Clin Anesth. (2013) 25:129–34. 10.1016/j.jclinane.2012.06.021

119.

De Bels D Corazza F Germonpre P Balestra C . The normobaric oxygen paradox: a novel way to administer oxygen as an adjuvant treatment for cancer?Med Hypotheses. (2011) 76:467–70. 10.1016/j.mehy.2010.11.022

120.

Burk R . Oxygen breathing may be a cheaper and safer alternative to exogenous erythropoietin (EPO). Med Hypotheses. (2007) 69:1200–4. 10.1016/j.mehy.2007.03.015

121.

Van Meter KW Weiss LD Harch PG . Hyperbaric oxygen in emergency medicine. In: JainKK, editors. Textbook of Hyperbaric Medicine, 3rd Edn. Seattle, WA: Hogrefe & Huber (1999), p. 557–88.

122.

Kot J Sicko Z Doboszynski T . The extended oxygen window concept for programming saturation decompressions using air and nitrox. PLoS ONE. (2015) 10:e130835. 10.1371/journal.pone.0130835

123.

Tibbles P Edelsberg JD . Hyperbaric oxygen therapy. N Engl J Med. (1996) 334:1642–8. 10.1056/NEJM199606203342506

124.

Kjellbert A Douglass J Pawlik MT Kraus M Oscarsson N Zheng X et al . Randomised, controlled, open label, multicentre clinical trial to explore safety and efficacy of hyperbaric oxygen for preventing ICU admission, morbidity and mortality in adult patients with COVID-19. BMJ Open. (2021) 11:e046738. 10.1136/bmjopen-2020-046738

Summary

Keywords

anemia, normobaric oxygen, hyperbaric oxygen, adenosine triphosphate, advanced cardiac life support, advanced trauma life support, oxygen debt, normobaric oxygen paradox

Citation

Van Meter KW (2024) Hyperbaric oxygen therapy in the ATLS/ACLS resuscitative management of acutely ill or severely injured patients with severe anemia: a review. Front. Med. 11:1408816. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2024.1408816

Received

28 March 2024

Accepted

19 August 2024

Published

08 October 2024

Volume

11 - 2024

Edited by

Carmine Siniscalchi, University of Parma, Italy

Reviewed by

Lucia Prezioso, University Hospital of Parma, Italy

Alfredo Caturano, University of Campania Luigi Vanvitelli, Italy

Costantino Balestra, Haute École Bruxelles-Brabant (HE2B), Belgium

Updates

Copyright

© 2024 Van Meter.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Keith W. Van Meter kvanme@lsuhsc.edu

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.