Abstract

Introduction:

Specific evidence regarding the pharmacist’s role in antifungal stewardship (AFS) is emerging. This review aims to identify pharmacist-driven AFS interventions to optimize antifungal therapy.

Methods:

A systematic review was conducted using Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines. Data (2018–2023) were collected through Google Scholar and PubMed. The collected data were presented descriptively due to variations in interventions and outcome metrics. Conclusions were derived through a qualitative synthesis of the identified findings.

Results:

A total of 232 articles were retrieved, and after applying inclusion and exclusion criteria, 27 were included in the review. Among the eight studies evaluating the impact of pharmacist interventions on antifungal consumption, 6 studies reported a significant decline in defined daily dose (DDD)/1,000 patient days and days of therapy (DOT)/1,000 patient days, one reported a non-significant decrease, and one reported an increase in the utilization of echinocandins. Educational intervention was the most commonly used stewardship approach. Nineteen studies reported data on various clinical outcomes. Mortality and length of hospital stay remain non-significant, but the occurrence of ADR decreased significantly, and the quality of antifungal use improved significantly.

Conclusion:

Pharmacist-led AFS has the potential to enhance the effectiveness of antifungal treatments by improving their overall quality, reduction in consumption, and adverse events. The healthcare system should encourage multidisciplinary collaboration where pharmacists play a central role in decision-making processes regarding antifungal use.

1 Introduction

Invasive fungal infections (IFIs) predominantly involving invasive candidiasis and aspergillosis represent a dynamic and growing global public health concern due to increased risk of morbidity and mortality. Patients with solid organ transplant, hematopoietic stem cell transplant, malignancy, critically ill, long-term corticosteroid and antibiotics use are at higher risk of IFIs (1). The incidence of IFIs varies based on the geographical location (2). Globally, over 800 million individuals experience IFIs, with annual mortality rates reaching 1,660,000, comparable to tuberculosis (1,700,000). In Asian countries, the prevalence of IFI is 3–15 times higher than that in the Western nations. Besides the elevated mortality rates ranging from 10 to 49%, IFIs pose significant economic challenges due to extended hospital stays and severe financial consequences (3).

Antimicrobial resistance (AMR) is recognized as a major deterrent to public health systems, impacting not only developing countries but also worldwide (4). Empiric use of antifungals in critically ill patients and immunocompromised patients increases the risk of antifungal resistance (AFR) (5). One of the biggest challenges in clinical practice is the resistance of Candida and Aspergillus species to azoles, followed by echinocandins (5). The resistance to antifungal agents can have various contributing factors, including host-related or drug-related factors such as inadequate dosing, inaccurate diagnosis, and patient non-compliance. Additionally, microbiological factors, such as genetic mutations in the organism, or a combination of both, may play a role in this multifactorial mechanism (6).

Drug-resistant microorganisms are becoming more prevalent, endangering the capacity to treat common infections and carry out life-saving procedures such as organ transplants and chemotherapy for cancer. Treatment for fungal infections can be challenging, in part because of interactions between drugs that are being prescribed to patients with comorbid infections, such as HIV and cancer. It is especially concerning with multidrug-resistant Candida auris, which is one of the fungal pathogens responsible for invasive fungal infections. WHO has developed a list of 19 fungal priority pathogens categorized into three priority groups, namely, critical, high, and medium priority. These fungi are responsible for invasive infections, which are difficult to treat, and there is a high risk of fungal resistance (7).

Establishing an efficient antifungal stewardship program (AFSP) is crucial for managing drug resistance. This program should integrate rapid fungal diagnostics, therapeutic drug monitoring, and clinical intervention teams. The advancement of improved diagnostic tools and strategies is imperative to enable the precise and targeted utilization of antifungals, ensuring the preservation of their effectiveness and reduction in resistance (8). Studies have shown that AFSP significantly improves the quality of antifungal use, antifungal consumption, and clinical outcomes (9). Pharmacist as a member of AFS program plays a pivotal role in promoting rational drug use and optimizing therapy. Several studies have highlighted the positive impact of pharmacist-led interventions on antimicrobial stewardship programs. Still, specific evidence regarding their role in antifungal stewardship is scarce. This systematic review aimed to explore and document the available literature on Pharmacist-led AFS and the impact of these interventions on antifungal consumption and clinical outcomes.

2 Methods

2.1 Information sources and search strategy

A comprehensive search was carried out to gather data on pharmacist interventions as a member of the antifungal stewardship team on optimizing antifungal use. The literature was searched through Google Scholar using the keywords “Antifungal stewardship and/or antimicrobial stewardship and/or pharmacist interventions and/or consumption and/or quality of antifungal use and/or clinical outcomes” which provided 130 publications; literature search through PubMed that derived 69 publications with mesh terms “Antimicrobial Stewardship” AND “Antifungal Agents” and 33 publications with mesh terms “Antimicrobial Stewardship” AND “Antifungal Agents” AND “Invasive Fungal Infections/Drug Therapy.” All the available data for the period 2018–2023 was searched in October 2023.

2.2 Study eligibility criteria

Inclusion criteria: (a) Studies that delineated an AFS program or intervention done by a pharmacist and presented data on antifungal consumption and clinical outcomes within the AFS program; (b) full access to original research articles; and (c) articles in the English language.

Exclusion criteria: (a) Review papers, editorials, abstracts, and duplicate studies were excluded; (b) Studies lacking an intervention; and (c) those not assessing the designated outcome of interest. The outcomes of interest include any stewardship interventions done by pharmacists that impact antifungal consumption and clinical measures (infectious diseases [IDs] consultation, mortality, length of hospital stay, adherence to guidelines, and adverse events).

2.3 Study selection and data extraction process

Two researchers independently screened studies by titles and abstracts initially. After screening titles and abstracts, 27 full-text articles that met the inclusion criteria were reviewed by one researcher. Microsoft Excel spreadsheet was used to document information on all of the included variables: study reference, study design, study setting and location, study period, number of patients, type of intervention, study objective, and study outcomes. A second researcher independently reviewed the extracted data. Any disagreement between collected data was resolved through discussion between all authors.

2.4 Synthesis of results

The systematic review adhered to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) checklist (10). The collected data were presented descriptively due to the variations in interventions and outcome metrics. Conclusions were derived through a qualitative synthesis of the identified findings. All primary studies used descriptive statistics for their evaluations, presenting findings as frequencies and percentages without employing an effect measure estimate. Therefore, the study results were organized descriptively into tables, ensuring transparent reporting of the systematic review findings.

2.5 Quality assessment

Three investigators independently assessed the risk of bias in all included studies using the Robin-I tool (11) which evaluates studies across seven domains, including confounding, participant selection, intervention classification, deviation from intended intervention, missing data, measured outcome, and selection of reported results, as shown in Figure 1. The final assessment regarding the risk of bias in all studies was made through a mutual agreement among all authors. Studies were judged as having a low risk of bias if it is comparable to randomized trials, a moderate risk of bias if it provides solid evidence for a non-randomized design, though they cannot be considered equivalent to a well-conducted randomized trial, and a serious risk of bias if it has significant issues that can impact the credibility of results (11). Studies with low or moderate risk were included.

Figure 1

Risk of bias assessment using Risk of Bias In Non-randomized Studies-of Interventions (ROBINS-I) tool. Domains: D1. Bias due to confounding, D2. Bias in the selection of participants in the study, D3. Bias in the classification of interventions, D4. Bias due to deviations from intended interventions, D5. Bias due to missing data, D6. Bias in measurement of outcome, D7. Bias in the selection of the reported result. Judgment: low risk  , moderate risk

, moderate risk  , serious risk

, serious risk  .

.

3 Results

3.1 Search results

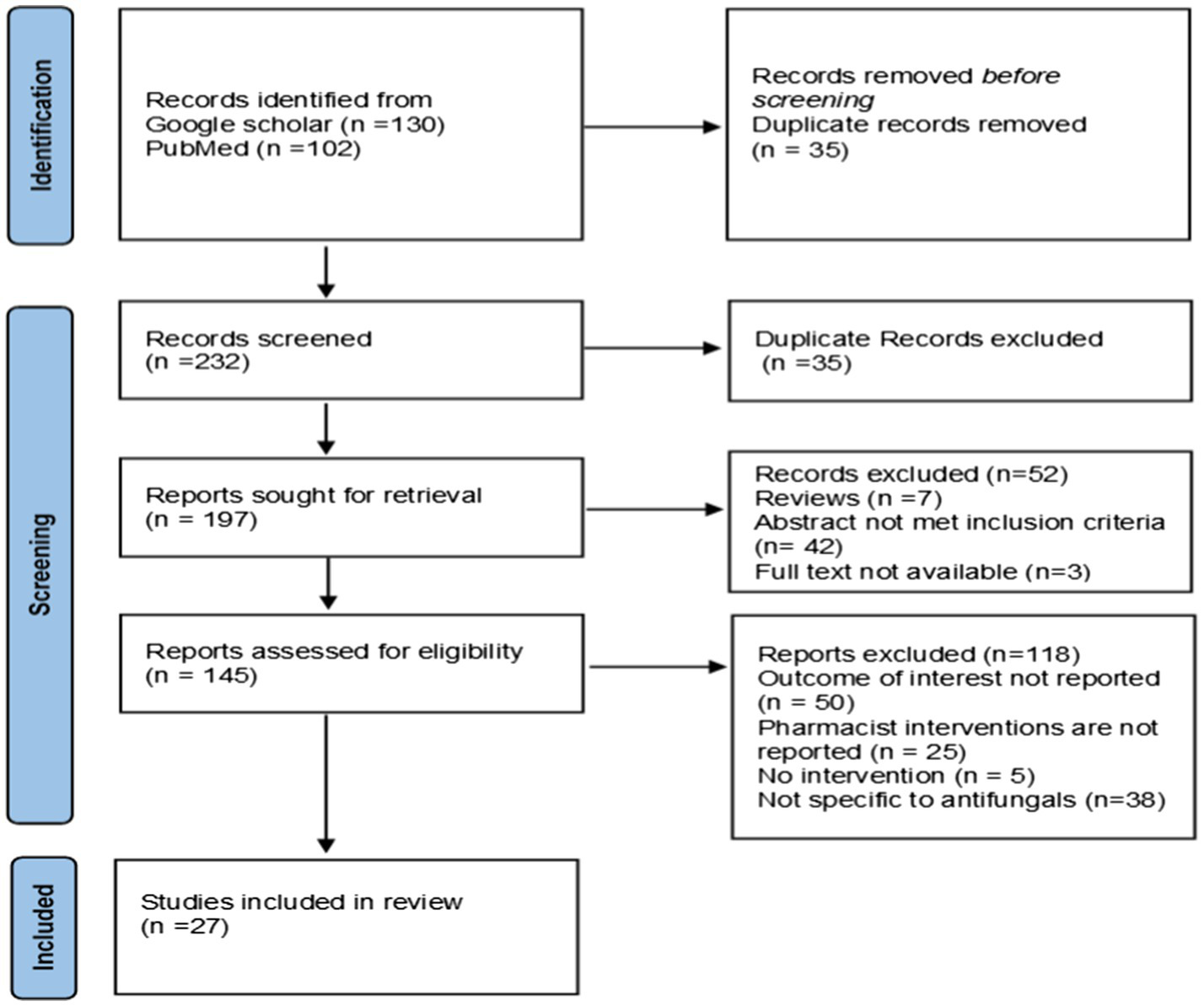

Two hundred and thirty two articles were identified using keywords and mesh terms through Google Scholar and PubMed. After removing duplicates, abstracts only, review papers, not evaluating pharmacist interventions or the outcome of interest, and not evaluating poststewardship activity impact on outcomes were excluded. After exclusion, 27 articles that met the criteria were included in the systematic review (Figure 2).

Figure 2

PRISMA 2020 flow diagram.

3.2 Study characteristics

Among 27 studies that are included in the review, eight studies evaluated the impact of pharmacist interventions on antifungal consumption in terms of defined daily dose (DDD) or days of therapy (DOT) and cost reduction. DDD is the assumed average maintenance dose per day of a drug for its primary indication in adults, whereas DOT measures the number of days a patient receives a particular drug, regardless of the dose (12). The remaining 19 studies evaluated the impact of pharmacist interventions on clinical outcomes, including 30-day mortality, length of hospital stay, ID consultations, and occurrence of adverse events, as summarized in Table 1.

Table 1

| Study reference | Study design | Study setting and location | Study population | Study period | Number of patients /prescriptions | Antifungal drug/s | Type of intervention | Study objective/method | Study outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Antifungal consumption (DDD/1,000 patient days; DOT/1,000 patient days; DDD/100 bed days) | |||||||||

| Morii et al. (33) | Prospective quasi-experimental study-interrupted time series | Showa General Hospital (Tokyo) | Adult in-patients | 2006–2016 | Not reported | Intravenous (IV) amphotericin B, liposomal amphotericin B, fosfluconazole, miconazole, itraconazole, voriconazole, micafungin, and caspofungin | Educational intervention, prospective audit, and feedback | AF use (DDD/1,000 patient days) and expenditure per fiscal year (FY) | 62% decrease in DDD/1,000 patient days and 73% reduction in total expenditure |

| Nwankwo et al. (34) | Prospective interrupted time series | Tertiary cardiopulmonary care center, Royal Brompton & Harefield NHS Foundation Trust (UK) | Adult in-patients with chronic fungal lung disease | 18 months | 178 patients | Intravenous antifungals | Recommendations on a diagnostic test, stepping down treatment to the oral drug, conducting TDM, and stopping treatment in patients without a confirmed diagnosis | AF use (DDD/100 bed days) and monthly AF expenditure | Significant reduction in DDD/100 bed days (p = 0.017) and 44.8% reduction in expenditure |

| So et al. (35) | Retrospective observational time series analysis | Tertiary care hospital Princess Margaret Cancer Centre, University Health Network (Canada) | Adult in-patient allogeneic stem cell transplantation in leukemia unit | 2005–2013 | 1,006 patients before ASP, 335 during ASP implementation, internal control (723/264); external control group (1.395/864) | Not reported | Educational intervention. Audit and feedback | Antimicrobial use (DDD per 100 patient days) and cost (Canadian dollar [C$] per patient days) | DDD/100 patient days reduced significantly (p < 0.01) and 13.76% reduction in AF expenditure |

| Kawaguchi et al. (28) | Retrospective, observational | OSAKA City University Hospital, Tertiary care teaching hospital (Japan) | Adults and pediatrics receiving systemic antifungals | 2011–2016 | 978 pre-intervention, 815 in the intervention group | L-AMB, caspofungin, micafungin, fosfluconazole, and voriconazole | Recommendation regarding appropriate selection and modification of AF | AF use (DDD/1,000 patient days), DOT /1,000 patient days. | Reduction in DDD/1000 patient days (NS), DOT/1000 patient days significantly reduced in the interventional group |

| (p = 0.009), and 13.5% reduction in AF expenditure | |||||||||

| Martín-Gutiérrez et al. (36) | Quasi-experimental-interrupted time series | Tertiary care teaching, University Hospital (Spain) | Adult patients ≥18 years with hospital-acquired candidemia | 2009–2017 | Not reported | Fluconazole, voriconazole, caspofungin, micafungin, anidulafungin and liposomal amphotericin B | Educational intervention including guideline development and periodical clinical sessions | DDD/1,000bed days | 38.3% reduction in DDD/1,000 bed days (p < 0.001) |

| Samura et al. (37) | Pre-/post-interventional (cohort) | Yokohama General Hospital (Japan) | Adult Inpatients who developed candidemia | 2008–2012 | 17/20 patients | Intravenous (IV) Fosfluconazole, micafungin, liposomal amphotericin B, and voriconazole, Oral itraconazole, fluconazole, voriconazole | ID pharmacist intervention regarding culture reports and antimicrobial use based on guidelines | Optimal AF drug selection, usage, and expenditure | 43.3% reduction in DOT (p < 0.001). post-AFS optimal AF usage significantly increased (p = 0.025), and AF expenditure significantly decreased (p = 0.002). |

| Markogiannakis et al. (38) | Prospective interrupted time series analysis | A tertiary care teaching hospital, General Hospital of Athens Laiko (Greece) | Adult patients ≥18 years with hematological/oncological malignancy | 2015–2017 | 147 + 138 (285) patients | Azoles, polyenes, and echinocandins antifungals | Educational intervention, prospective audit, and feedback | AF consumption and acquisition cost | 23.7% reduction in DDD/1,000 patient (p < 0.001) and 26.8% reduction in acquisition cost. |

| Kara et al. (27) | Prospective quasi-experimental | 1,040 bedded Tertiary Care University Hospital (Turkey) | Adult patients ≥18 years | 2019–2020 | 84/101/192 patients | Fluconazole, voriconazole, posaconazole, caspofungin, micafungin, Anidulafungin, Liposomal Amphotericin B and combinations | Educational intervention, audit, and feedback | AF consumption (DOT/1,000 patient days) | 59.4 and 60.9% increase in DOT/1.000 patient days for anidulafungin and for caspofungin, respectively, while 33.2 and 41.8% decrease for fluconazole and L-Amphotericin B |

| Clinical Outcomes(ID consultations, adherence to guidelines, Length of hospital stay, mortality, Adverse events, others) | |||||||||

| Murakami et al. (39) | Prospective quasi-experimental | Tertiary Care Saku Central Hospital (Japan) | Patients with candidemia aged >18 years | 2006–2012 | 30 + 46 | Micafungin, liposomal amphotericin B, voriconazole, fluconazole | Development of candidemia care bundle based on IDSA guidelines. | 30-day all-cause mortality and adherence to guidelines | 30-day all-cause mortality 11 (23.9%) vs. 7 (23.3%) NS. Appropriate drug and duration selection (p < 0.001), CVC removal following + blood culture (p = 0.012), and ophthalmological intervention (p < 0.001). |

| Rac et al. (40) | Prospective Quasi-experimental | Tertiary academic medical center (USA) | Patients ≥18 years having positive culture of candida | 2012–2016 | 50/67 | Micafungin and fluconazole | Implementing AF susceptibility testing, culture alerts, removal of central lines | Time to adequate AF therapy, infection-related LOS, compliance to ophthalmology consult, repeat cultures, and ≥ 14 days of adequate therapy | Significant ID consultation (p < 0.001), Switch towards oral AF (p = 0.015), reduction in time to order antifungal (p = 0.017) and receipt of antifungals (p = 0.026) post-intervention. No difference in LOS and compliance related to quality indicators in both groups. |

| So et al. (35) | Retrospective observational time series analysis | Tertiary care hospital Princess Margaret Cancer Centre (PM), University Health Network (Canada) | Adult patients admitted for allogeneic stem cell transplantation in leukemia unit | 2005–2013 | 1,006 patients before ASP, 335 during ASP implementation, internal control (723/264); external control group (1,395/864) | Not reported | Academic detailing (audit and feedback) and ID referrals | LOS, 30-day inpatient mortality | Post-intervention LOS (p = 0.29) and in patient mortality (p = 0.64) remains NS. |

| Benoist et al. (16) | Prospective cohort | French university hospital (France) | Adults and pediatric patients isolated with candida | 2012-2015 | 33/37 | Micafungin, fluconazole (IV/oral), amphotericin B IV, liposomal amphotericin flucytosine | Recommendation acc. to ESMID guidelines for candidemia management | ID consultations, AF treatment and dose de-escalation, Time to initiate treatment, 30-day and 90-day mortalities | Post-intervention ID consultations increased from 36.4 to 86.5%, with a significant increase in daily blood culture (p = 0.04), and dose de-escalation in 52.8% points. Echinocandins usage increased (p = 0.03), and 30-day, 90-day mortalities declined from 21.2% vs. 18.9 and 36.4 to 27.0%, respectively (NS). |

| Ito‐Takeichi et al. (24) | Prospective cohort | Tertiary care, Gifu University Hospital (Japan) | Adult patients with Candidemia infections | 2009–2016 | 35/22 | IV AF: Micafungin, fosfluconazole, voriconazole, liposomal Amphotericin B, Caspofungin Oral AF: Fluconazole, Itraconazole, Voriconazole |

Prospective audit and feedback along with monitoring βDG measurement | Time of starting therapy, 60-day clinical failure, LOS, and adverse events | Significant decline in clinical failure (p < 0.001) 60-day mortality decreased by 42.9% vs. 18.2%, LOS increased from 67 to 85 NS, and significant decline in AE (p = 0.004). |

| Kawaguchi et al. (28) | Retrospective, observational | Tertiary care teaching OSAKA City University Hospital (Japan) | Adult and pediatric patients on systemic antifungals | 2011–2016 | 978/815 | L-AMB, caspofungin, micafungin, fosfluconazole, and voriconazole. | Recommendations include selection and modification of AF based on + blood cultures and implementing a candidemia care bundle | 30-day mortality, in-hospital mortality, and achievement rates of the candida care bundle | NS decrease in 30-day mortality (p = 0.414) In-hospital, mortality reduced significantly (p = 0.054) Achievement of the candidemia care bundle was significant (p = 0.006). |

| Lachenmayr et al. (9) | Retrospective observational | University Hospital of Munich (Germany) | Adult patients ≥18 years with hematological/oncological malignancy | 2016–2017 | 103 | Liposomal Amphotericin B, voriconazole, posaconazole, fluconazole, caspofungin | Medical training for the physicians and on-ward pharmaceutical counseling | Quality of antifungal through pharmacist interventions and compliance rate of physicians toward interventions | Significant improvement in quality of AF prescriptions (p < 0.005) The compliance rate was 66.1%. |

| Chen et al. (20) | Retrospective observational | 2,600 bedded National Taiwan University Hospital (Taiwan) | Adult Patients admitted in hematology department | 2014-2016 | 670/773 | Not reported | Interventions in medication orders and therapeutic drug monitoring | Clinical and economic impact of interventions | Pharmacist intervention increased from 0.34 to 1.87% (p < 0.00001). LOS reduced from 19.27 to 16.69 Preventable ADE increased from 58 to 230, and 74.7% reduction in cost. |

| Hamada et al. (23) | Retrospective observational | 5 Hospitals (Japan) | Patient ≥18 years | 2015–2018 | 401 | voriconazole | Therapeutic drug monitoring | Impact of TDM-based dosing on AE | With dose adjustment, 8/9 patients with hepatotoxicity and 27/28 patients with visual symptoms completed treatment. |

| Martín-Gutiérrez et al. (36) | Prospective quasi-experimental—interrupted time series | 117 beds Tertiary care teaching, University Hospital (Spain) | Adult patients ≥18 years with hospital-acquired candidemia | 2009–2017 | Not reported | Fluconazole, voriconazole, caspofungin, micafungin, anidulafungin and liposomal amphotericin B | Educational intervention | Incidence of hospital-acquired candida infections and candidemia mortality. | Significant decline in incidence density of hospital-acquired candidemia (p = 0.009) and 14-day mortality rate reduced from 36.1 to 19.2% (p = 0.3) NS. |

| Mularoni et al. (41) | Prospective cohort study | Specialized care hospital, ISMETT-IRCCS (Italy) |

Adult Patients with invasive fungal infections and solid organ transplant recipient | 2009–2018 | 70 | Fluconazole, echinocandins | ID consult for empirical AF and switching from IV to oral fluconazole | Appropriateness of AF use, clinical cure, and costs. | Significant improvement inappropriate antifungal selection (40.5% vs. 78.6%) p < 0.0001, Clinical cure was improved 90% vs. 100%. Total expenditure was reduced by 45.8%. |

| Reslan et al. (32) | Prospective cohort, pre-/postinterventional | Tertiary referral hospital, outpatient cancer center (Sydney) | Out-patients adults >18 years & malignant hematology receiving chemotherapy elderly protocols | 2017–2018 | 40/42 | Azoles | Prospective review of prescriptions, suggesting azole TDM, identifying reasons for non-adherence to guidelines | Impact of a weekly pharmacist review on American and New Zealand Consensus Guidelines adherence for antifungal prophylaxis | Appropriate antifungal prophylaxis increased from 31 to 54% (p = 0.0001), Appropriate utilization of guidelines increased (p = 0.0344). Lack of TDM was the main reason for non-adherence, 48.5% vs. 46%. |

| Samura et al. (37) | Prospective cohort, pre-/postinterventional | Yokohama General Hospital (Japan) | Adult inpatients who developed candidemia | 2008–2012 | 17/20 patients | IIV Fosfluconazole, micafungin, liposomal amphotericin B, and voriconazole, Oral itraconazole, fluconazole, voriconazole | ID pharmacist intervention regarding culture reports and antimicrobial use based on guidelines | 30-day mortality | 30-day mortality rates pre-/post-AFS group was 29.4% vs. 60% (p = 0.099) NS. |

| Amanati et al. (14) | Cross-sectional | Tertiary Teaching Hospital, Sheraz, Amir Medical Oncology Center (Iran) | Children aged ≤18 years with hematologic malignancy or solid tumor | (2011–2012) (2017-2018) |

136 patients | Amphotericin B, caspofungin, voriconazole, itraconazole, fluconazole | AF susceptibility testing, adherence to guidelines, application of non-culture-based methods GM, PCR | Impact of AFS on AF susceptibility patterns of colonized Candida sp. | The most prevalent strain was Candida albicans. Resistance to azoles was significantly reduced from 52.5 to 1.5% (p < 0.001), caspofungin resistance reduced from 10.1 to 0.9%, fluconazole resistance reduced from 32.9 to 0.0% (p < 0.001). |

| Kara et al. (27) | Prospective quasi-experimental | 1,040-bedded Tertiary Care University Hospital (Turkey) | Adult patients ≥18 years receiving systemic antifungals | 2019–2020 | 84/101/192 patients | Fluconazole, voriconazole, posaconazole, caspofungin, micafungin, Anidulafungin, Liposomal Amphotericin B and combinations | Feedback/education to physicians, evaluation of appropriateness of AF, and adherence to guidelines | Adequacy of AF therapy, pDDI, and 30-day mortality | Appropriateness of AF use increased significantly (p < 0.001). The acceptance rate of recommendations was 96% (151/157). pDDI decreases significantly (p = 0.035) and 30-day mortality reduced (p = 0.05). |

| Markogiannakis et al. (38) | Prospective quasi-experimental interrupted time series analysis | 535-bed tertiary care teaching hospital, General Hospital of Athens Laiko (Greece) | Adult patients ≥18 years with hematological/oncological malignancy | 2015–2017 | 147 + 138 (285) patients | Azoles, polyenes, and echinocandins antifungals | Educational intervention, prospective audit, and feedback | Quality of prescriptions, in-hospital-mortality, and in-hospital length-of-stay | A significant increase in the appropriateness of prescriptions 47% → 76.2% (p = 0.01) All-cause in-hospital mortality reduced from 39.5 → 37.1, and LOS reduced from 5.19 → 4.96 (NS) |

| Gamarra et al. (22) | Prospective quasi-experimental | 250 bedded a university-affiliated tertiary care hospital, Hospital Universitario Clementino Fraga Filho (Brazil) | Patients admitted to the hematology ward, infectious diseases ward, internal medicine and ICU | 2016–2018 | 270 Patients | Fluconazole, amphotericin B (deoxycholate, lipid complex and liposomal), voriconazole, posaconazole, and echinocandins | Educational intervention using charts followed by a retrospective audit | Adequacy of AF use | Significant reduction of inappropriate prescriptions (80.2%) in the first audit vs. 64.6% in the second audit (p = 0.001). |

| Bio et al. (18) | Retrospective cohort | Children hospital (America) | In-patient children <18 years | 2020–2022 | 1,803 prescriptions | Fluconazole, posaconazole, isavuconazole, and echinocandins | Prospective audit and feedback | Recommendation rate and acceptance | Among 379 recommendations, 298 were accepted (78.62%). Among all, discontinuation of AF was the most common. |

| Keck et al. (29) | Prospective quasi-experimental | University of Mississippi Medical Center (Mississippi) | In-patients ≥18 years who had received at least one treatment dose of micafungin | 2020–2022 | 282 patients | Micafungin | ID consult via prospective audits and feedback. | Days of micafungin therapy, LOS, in-patient mortality, time to de-escalation, and discontinuation after 72-h time out | Duration of micafungin treatment decreased (p = 0.005), whereas, LOS (p = 0.137), in-patient mortality (p = 0.637), and micafungin discontinuation (p = 0.788), or de-escalation (p = 0.530) remains NS. |

Summary of studies.

p<0.05 indicates significant results. DDD, Defined daily dose; DOT, Days of therapy; NS, Non-significant; AFS, Antifungal stewardship; LOS, Length of hospital stay; ID, Infectious disease; pDDI, potential drug–drug interaction; IV, Intravenous; GM, Galactomannan; PCR, Polymerase chain reaction; AF, Antifungal.

All studies were single-centered except one that was conducted in five different hospitals. Among all included studies evaluating antifungal consumption, four studies evaluated DDD/1,000 patient days, and three studies measured DOT/1,000 patient days. Two studies measured DDD/100 patient or bed days (3, 13–18). Five studies were prospective quasi-experimental in design and conducted time series analysis, while two studies were observational, and 1 was prospective cohort. All studies have variable duration, with a least 18 months and a maximum duration of 10 years. Pharmacist interventions include educational interventions, prospective audits and feedback, and focusing adherence to guidelines.

Among studies evaluating clinical outcomes, seven studies were prospective, quasi-experimental in design, five studies were retrospective observational, five studies were prospective cohort, one was retrospective cohort, and one was cross-sectional in design. All studies were single-centered except one that evaluated clinical outcomes of AFS in five hospitals. The majority of studies were carried out on adult patients >18 years of age, and the maximum duration of the study was 7 years, and the minimum duration was 2 years (1, 2, 4–7, 9, 19–30), as shown in Table 1.

3.3 Interventions

Pharmacist interventions vary among the included studies. In five of the eight studies evaluating the impact of the consumption of antifungals, pharmacist interventions were based on educational activities that included academic detailing inculcating prospective audits and feedback (3, 13, 15, 17, 18). Other interventions include recommendations about diagnostic tests, TDM-based dosing and stopping treatment in patients without confirmed diagnosis (14), appropriate selection and modification of therapy (16), and optimizing antifungal therapy based on culture reports and guideline recommendations (18).

Nineteen studies that evaluated the impact on clinical outcomes, namely, pharmacist interventions included the development of candidemia care bundle based on Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA) guidelines (19, 22), implementing antifungal (AF) susceptibility testing, culture alerts, initiation of echinocandins, removal of central lines (20), academic detailing (audit and feedback) regarding appropriate empiric regimen, tailoring and reassessment (2, 4, 29, 30), therapeutic drug monitoring (4, 5, 23, 25), and infectious disease referrals (1, 4) along with β-d-glucan (βDG) measurement (7, 9), recommendation according to European Society of Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases (ESMID) guidelines for candidemia management (21), medical training for the physicians, pocket card summarizing recommendations for antifungal use and on-ward pharmaceutical counselling (6), stopping empirical antifungal after 72 h, automated alert and ID consult for empirical antifungals and switching from intravenous (IV) to oral fluconazole (1), ID pharmacist intervention regarding culture reports (26, 27), adherence to guidelines, application of non-culture based methods Galactomannan, polymerase chain reaction (PCR) (27), feedback/education to physician (28) are shown in Table 1.

3.4 Antifungal consumption

Eight studies evaluated the impact of pharmacist interventions on antifungal consumption. Consumption metrics used were variable, and few studies involved more than one metric. Three studies measured DDD/1,000 patient days (3, 16, 18), One study measured DDD/100 bed days (14), one measured DDD/100 patients (15), three measured DOT/1,000 patient days (3, 16, 18), and one measured DDD/1,000 bed days (17). Due to the variability in measuring units, a quantitative estimation was not possible; however, DDD/1,000 patient days significantly declined (62%; p = 0.009; p < 0.001); a significant reduction in DDD/100 bed days (p < 0.017); a significant decrease in DDD/100 patients (p < 0.01); DOT/1,000 patient days remained insignificant in one study and a significant decrease in one study (p < 0.001) was evident; and one study showed an increase in DOT/1000 patients for anidulafungin and caspofungin while declining in fluconazole and L-amphotericin B as a result of pharmacist interventions (Table 1).

3.5 Clinical outcomes

Clinical outcomes that were evaluated post-AFS implementation included mortality, the length of hospital stay, the occurrence of adverse events, and the quality of antifungal use (Table 1).

3.6 Mortality

The impact of stewardship interventions was evaluated on 30-day, 60-day, and 14-day mortalities and on in-patient mortality in the included studies. Five studies reported the data of 30-day mortality, in which four showed non-significant results pre-/postintervention (19, 21, 22, 26) and one study showed a significant decline in 30-day mortality post-AFS (p = 0.05) (28). Furthermore, 60-day, 90-day, and 14-day mortalities pre-/post-AFS also remained non-significant (7, 21, 24). In-hospital/in-patient mortality was decreased significantly in one study (p = 0.054) (22) and non-significantly in two studies (9, 29).

3.7 Length of hospital stay

Five studies measured the length of hospital stay as an outcome of antifungal stewardship, and in all included studies post-AFS, there is a non-significant change in the length of hospital stay (4, 7, 9, 20, 29).

3.8 Adverse events

Four studies evaluated the role of pharmacist interventions on the occurrence of adverse drug events. One study showed that pharmacist interventions resulted in a significant decline in adverse events (p = 0.004) (7), and one study showed a significant increase in preventable adverse drug events post-AFS 58 vs. 230 (23). The results of another study evaluating TDM-based dosing identified that the drug discontinuation due to hepatotoxicity and visual symptoms was 62.5 and 26.3%, respectively (5), and one study identified that potential drug–drug interaction (pDDI) decreased significantly as a result of pharmacist interventions (p = 0.035) (28).

3.9 Quality of antifungal use

Quality of antifungal use encompasses appropriate drug selection, referrals for ID consultation, implementing culture tests, and adherence to guidelines. Fifteen studies evaluated different parameters of the quality of antifungal use post-AFS. Seven studies (1, 6, 19, 25, 28–30) evaluated appropriate drug selection, and all studies showed significant improvement in antifungal selection (p < 0.001, p < 0.005, p < 0.0001, p = 0.0001, p < 0.001, p = 0.01, and p = 0.001) respectively. The result of one study showed that repeat blood cultures were improved significantly (p = 0.012 and p = 0.04) (19, 21). One study reported a significant increase in ID consultation (p < 0.001) (20), and another study reported an increase from 36.4 to 86.5% (21). One study reported data on the resistance rate to azoles post-AFS, which was significantly declined (p < 0.001) (27), and the incidence of hospital-acquired candidemia was also decreased (p = 0.009). Three studies evaluated adherence to guidelines. One study showed significant adherence to IDSA guidelines (19); another study reported that achievement and adherence to the candidemia care bundle were significant postintervention (p = 0.006) (22); and one study showed significant adherence to clinical guidelines for antifungal prophylaxis (p = 0.0344) (25) as shown in Table 1.

3.10 Antifungal expenditure

Seven studies reported the impact of pharmacist intervention on antifungal expenditure or cost savings. Among all, the maximum reduction in antifungal expenditure was 73% (13), and the least reduction in cost was 13.5% (16). Two studies reported a significant decline in antifungal cost (p = 0.03 and p = 0.002), as shown in Table 1. An overall summary of study characteristics is shown in Table 2.

Table 2

| Study characteristics | Number of studies | Study reference |

|---|---|---|

| Age group | ||

| Adult | 22 | (1–7, 9, 13–15, 17–20, 23–26, 28–30) |

| Pediatric | 2 | (2, 27) |

| Both | 3 | (16, 21, 22) |

| Patient type | ||

| Inpatient | 26 | (1–7, 9, 13–24, 26–30) |

| Outpatient | 1 | (25) |

| Country | ||

| High-income country | 23 | (1, 2, 4–7, 9, 13–26, 29) |

| Low-income country | 4 | (3, 27, 28, 30) |

| Study design | ||

| Prospective, quasi-experimental | 12 | (3, 9, 13, 14, 17–20, 24, 28–30) |

| Retrospective observational | 7 | (4–6, 15, 16, 22, 23) |

| Prospective cohort | 6 | (1, 7, 18, 21, 25, 26) |

| Retrospective cohort | 1 | (2) |

| Cross-sectional | 1 | (27) |

| Type of intervention | ||

| Educational intervention, audit, and feedback | 15 | (2–4, 6, 7, 9, 13, 15, 17–19, 24, 28–30) |

| Pharmacist recommendation for therapeutic drug monitoring, fungal markers, Antifungal susceptibility testing, and blood culture | 14 | (1, 5, 9, 14, 16–18, 20–23, 25–27) |

| Outcomes | ||

| Antifungal consumption | 8 | (3, 13–18) |

| Antifungal expenditure | 7 | (13–16, 18, 23) |

| Mortality | 8 | (4, 7, 9, 19, 21, 22, 24, 26) |

| Length of hospital stay | 4 | (4, 9, 20, 23) |

| Decline in clinical failure | 2 | (1, 7) |

| Referral for ID consults | 2 | (20, 21) |

| Quality of antifungal use | 8 | (2, 6, 9, 21, 25, 28–30) |

| Reduction in adverse drug events | 4 | (5, 7, 23, 28) |

| Reduction in resistance rate | 1 | (27) |

Summary of study characteristics.

4 Discussion

This review aims to evaluate the role of AFS pharmacists in optimizing antifungal therapy and its impact on antifungal usage, consumption, and clinical outcomes globally. The majority of healthcare systems lack proper diagnostic techniques, and suboptimal levels of antifungal drugs with non-linear kinetics result in treatment failure (21). Literature has shown that pharmacist-driven AFS can enhance the appropriateness of antifungal treatments by improving the selection of drugs, dosages, and therapy durations, while also preventing potential drug interactions (27).

The stewardship approach was variable among all included studies, but the most common pharmacist intervention was academic detailing with audit and feedback followed by dose adjustments based on therapeutic drug monitoring. Prospective audits and feedback in hospital settings have been demonstrated to enhance the quality of prescription practices and are advocated as a vital component of antifungal stewardship (18). Medical training for physicians and on-ward pharmaceutical counseling regarding antifungal utilization can be crucial in securing a sustained impact of an interdisciplinary AFSP (9). Previous studies have shown that prescribers could not differentiate between fungal colonization and underlying disease, as well as the appropriate use of prophylactic vs. empirical antifungal medication (31). Therapeutic drug monitoring (TDM) plays a crucial role in optimizing antifungal therapy, with routine recommendations for voriconazole monitoring outlined in the guidelines of the British Society for Medical Mycology and the IDSA (15). Voriconazole, being the first-line drug for invasive aspergillosis, exhibits non-linear pharmacokinetics, where both high and low serum concentrations are associated with increased risks of hepatotoxicity and therapeutic failure, respectively (25). Study results showed that with TDM-based dose adjustment, the treatment completion rate was increased (8.8%) (23). Another study reported that the major reason for non-adherence was a lack of TDM (32). Implementing TDM practices within healthcare institutions can enhance the effectiveness and safety of antifungal therapy by ensuring optimal drug exposure for each patient. Antifungal stewardship teams involving pharmacists in hospitals led to a notable decrease in the consumption and acquisition costs of antifungals (30). Mycoses Study Group Education and Research Consortium recommended that Stewardship team core members should possess a deep understanding of fungal epidemiology and susceptibility patterns, laboratory diagnosis of IFD, the spectrum, and pharmacokinetics of antifungal drugs, strategies for optimizing dosing and duration, fungal surveillance, and the ability to anticipate, interpret, and manage drug–drug interactions and antifungal toxicities. Furthermore, proficiency in interpreting therapeutic drug monitoring is essential. Ideally, the team should include infectious diseases (ID) physician(s) and ID-trained pharmacist(s) whenever feasible (26).

The impact of stewardship intervention was evaluated on the consumption of antifungals. All included studies utilize variable matrices DDD/100 patient days, DOT/1,000 patient days, or DDD/1,000 bed days. However, overall, antifungal consumption decreases (3, 13–18) and results in a cost reduction of up to 74.7 (23), with another reporting 73% (13). In a systematic review conducted in 2017 on AFS interventions and performance measures, it was noted that antifungal consumption exhibited a decrease ranging from 11.8 to 71% and a reduction in expenditure of 50% (17). AFS programs aim to strike a balance between effective treatment and prudent use of antifungal agents, decreasing overall antifungal consumption. Pharmacist interventions are crucial in reducing antifungal consumption by optimizing therapy, implementing evidence-based guidelines, utilizing therapeutic drug monitoring (TDM), providing education and training, and transitioning patients from intravenous to oral antifungals when appropriate. These strategies help ensure the judicious use of antifungal agents, ultimately reducing both consumption and associated healthcare costs (9). Antifungal drugs are expensive; their judicious use promotes better resource allocation, reduces healthcare costs, and improves patient outcomes. Optimization of antifungal therapy by ensuring appropriate selection, dosing, and treatment duration, not only curbs unnecessary spending but also lowers the risk of antifungal resistance, ultimately enhancing the quality of care for patients with fungal infections (13).

Another parameter evaluated in this review was clinical outcomes including mortality, the length of hospital stay, the occurrence of adverse events, and the quality of antifungal prescribing or use. Major interventions of pharmacists include academic detailing, tailoring drug therapy based on culture reports, and conducting therapeutic drug monitoring. In-hospital/patient mortality decreased significantly in one study (22), and one study showed a significant decline in 30-day mortality post-AFS (28), while all other included studies reported a non-significant decline in mortality and length of hospital stay. Although it was non-significant, overall, AFS decreases mortality and length of hospital stay. However, the exact estimate is not possible as the underlying disease may be associated with early mortality. More studies are required to further strengthen this evidence. Moreover, heterogeneity of patient population, diverse clinical presentation and variable treatment response contribute to the difficulty in providing precise estimates for mortality and LOS in immunocompromised patients with systemic fungal infections. Four studies identifying the impact of adverse events reported a significant decline in adverse event occurrence and potential drug–drug interactions (5, 7, 23, 28). AFS programs involve regular monitoring of patients on antifungal therapy. This surveillance helps promptly identify and address adverse events, contributing to improved patient safety (27).

Quality of antifungal use evaluated post-AFS in 15 studies includes appropriate prescribing, culture-based drug tailoring, and adherence to guidelines for fungal infection management. All included studies reported significant improvement in antifungal prescribing, culture evaluation for targeting therapy, and adherence to guidelines. Diagnostic precision and optimized dosing overall improve the quality of antifungal use (19).

5 Conclusion

Pharmacist-led AFS has the potential to enhance the effectiveness of antifungal treatments by improving their overall quality and reduction in antifungal consumption, adverse events, and antifungal expenditure. Moreover, novel fungal diagnostic techniques, TDM, and antifungal susceptibility testing must be integrated with AFS in hospitals to rationalize antifungal use and decrease the emerging threat of antifungal resistance.

5.1 Strength and limitation

Systematic reviews focusing on pharmacist-driven antifungal stewardship interventions after 2018 are scarce. Thus, we collected literature from PubMed and Google Scholar databases to present and evaluate the published evidence in the last 5 years (2018–2023). Due to limited institutional access to other resources such as Embase and Scopus, data collection was restricted only to two databases. The major limitation is variation in interventions and outcome metrics; hence, an integrative review approach was utilized. Variations in healthcare settings may limit the generalizability of the findings. All primary studies used descriptive statistics for their evaluations, presenting findings as frequencies and percentages without employing an effect measure estimate; therefore, results were presented descriptively.

5.2 Future perspective

Future research should investigate the influence of pharmacist-led stewardship in outpatient clinics and community settings. In addition, further studies are also warranted on the pediatric population using the DOT methodology to provide a more comprehensive and standardized assessment of pharmacist interventions on consumption as well as clinical outcomes. Detailed subgroup analyses based on specific healthcare settings and intervention types are also required to elucidate how differences in healthcare settings and types of interventions impact clinical outcomes.

Statements

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author contributions

ZA: Data curation, Writing – original draft. MA: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Writing – review & editing. ZS: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1.

Jenks JD Cornely OA Chen SCA Thompson Iii GR Hoenigl M . Breakthrough invasive fungal infections: who is at risk?Mycoses. (2020) 63:1021–32. doi: 10.1111/myc.13148

2.

Kmeid J Jabbour J-F Kanj SS . Epidemiology and burden of invasive fungal infections in the countries of the Arab league. J Infect Public Health. (2020) 13:2080–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jiph.2019.05.007

3.

Borjian Boroujeni Z Shamsaei S Yarahmadi M Getso MI Salimi Khorashad A Haghighi L et al . Distribution of invasive fungal infections: molecular epidemiology, etiology, clinical conditions, diagnosis and risk factors: a 3-year experience with 490 patients under intensive care. Microb Pathog. (2021) 152:104616. doi: 10.1016/j.micpath.2020.104616

4.

Dadgostar P . Antimicrobial resistance: implications and costs. Infect Drug Resist. (2019) 12:3903–10. doi: 10.2147/IDR.S234610

5.

Hendrickson JA Hu C Aitken SL Beyda N . Antifungal resistance: a concerning trend for the present and future. Curr Infect Dis Rep. (2019) 21:1–8. doi: 10.1007/s11908-019-0702-9

6.

Gupta AK Venkataraman M Renaud HJ Summerbell R Shear NH Piguet V . The increasing problem of treatment-resistant fungal infections: a call for antifungal stewardship programs. Int J Dermatol. (2021) 60:e474–9. doi: 10.1111/ijd.15495

7.

Fisher MC Denning DW . The who fungal priority pathogens list as a game-changer. Nat Rev Microbiol. (2023) 21:211–2. doi: 10.1038/s41579-023-00861-x

8.

Perlin DS Rautemaa-Richardson R Alastruey-Izquierdo A . The global problem of antifungal resistance: prevalence, mechanisms, and management. Lancet Infect Dis. (2017) 17:e383–92. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(17)30316-X

9.

Lachenmayr SJ Strobach D Berking S Horns H Berger K Ostermann H . Improving quality of antifungal use through antifungal stewardship interventions. Infection. (2019) 47:603–10. doi: 10.1007/s15010-019-01288-4

10.

Page MJ Mckenzie JE Bossuyt PM Boutron I Hoffmann TC Mulrow CD et al . The Prisma 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. Int J Surg. (2021) 88:105906. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2021.105906

11.

Sterne JA Hernán MA Reeves BC Savović J Berkman ND Viswanathan M et al . Robins-I: a tool for assessing risk of bias in non-randomised studies of interventions. BMJ. (2016) 355. doi: 10.1136/bmj.i4919

12.

Vallès J Fernández S Cortés E Morón A Fondevilla E Oliva JC et al . Comparison of the defined daily dose and days of treatment methods for evaluating the consumption of antibiotics and antifungals in the intensive care unit. Med Intensiva. (2020) 44:294–300. doi: 10.1016/j.medin.2019.06.008

13.

Alsalman J Althaqafi A Alsaeed A Subhi A Mady AF Alhejazi A et al . Middle Eastern expert opinion: strategies for successful antifungal stewardship program implementation in invasive fungal infections. Cureus. (2024) 16:e61127. doi: 10.7759/cureus.61127

14.

Amanati A Badiee P Jafarian H Ghasemi F Nematolahi S Haghpanah S et al . Impact of antifungal stewardship interventions on the susceptibility of colonized Candida species in pediatric patients with malignancy. Sci Rep. (2021) 11:14099. doi: 10.1038/s41598-021-93421-3

15.

Ashok A Mangalore RP Morrissey CO . Azole therapeutic drug monitoring and its use in the Management of Invasive Fungal Disease. Curr Fungal Infect Rep. (2022) 16:55–69. doi: 10.1007/s12281-022-00430-4

16.

Benoist H Rodier S De La Blanchardière A Bonhomme J Cormier H Thibon P et al . Appropriate use of antifungals: impact of an antifungal stewardship program on the clinical outcome of candidaemia in a French university hospital. Infection. (2019) 47:435–40. doi: 10.1007/s15010-018-01264-4

17.

Bienvenu AL Argaud L Aubrun F Fellahi JL Guerin C Javouhey E et al . A systematic review of interventions and performance measures for antifungal stewardship programmes. J Antimicrob Chemother. (2018) 73:297–305. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkx388

18.

Bio LL Weng Y Schwenk HT . Antifungal stewardship in practice: insights from a prospective audit and feedback program. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. (2023) 44:2017–21. doi: 10.1017/ice.2023.129

19.

Chakrabarti A Mohamed N Capparella MR Townsend A Sung AH Yura R et al . The role of diagnostics-driven antifungal stewardship in the Management of Invasive Fungal Infections: a systematic literature review. Open Forum Infect Dis. (2022) 9:ofac234. doi: 10.1093/ofid/ofac234

20.

Chen P-Z Wu C-C Huang C-F . Clinical and economic impact of clinical pharmacist intervention in a hematology unit. J Oncol Pharm Pract. (2020) 26:866–72. doi: 10.1177/1078155219875806

21.

Fisher MC Alastruey-Izquierdo A Berman J Bicanic T Bignell EM Bowyer P et al . Tackling the emerging threat of antifungal resistance to human health. Nat Rev Microbiol. (2022) 20:557–71. doi: 10.1038/s41579-022-00720-1

22.

Gamarra F Nucci M Nouér SA . Evaluation of a stewardship program of antifungal use at a Brazilian tertiary care hospital. Braz J Infect Dis. (2022) 26:102333. doi: 10.1016/j.bjid.2022.102333

23.

Hamada Y Ueda T Miyazaki Y Nakajima K Fukunaga K Miyazaki T et al . Effects of antifungal stewardship using therapeutic drug monitoring in voriconazole therapy on the prevention and control of hepatotoxicity and visual symptoms: a multicentre study conducted in Japan. Mycoses. (2020) 63:779–86. doi: 10.1111/myc.13129

24.

Ito-Takeichi S Niwa T Fujibayashi A Suzuki K Ohta H Niwa A et al . The impact of implementing an antifungal stewardship with monitoring of 1-3, β-D-glucan values on antifungal consumption and clinical outcomes. J Clin Pharm Ther. (2019) 44:454–62. doi: 10.1111/jcpt.12809

25.

Job KM Olson J Stockmann C Constance JE Enioutina EY Rower JE et al . Pharmacodynamic studies of voriconazole: informing the clinical management of invasive fungal infections. Expert Rev Anti-Infect Ther. (2016) 14:731–46. doi: 10.1080/14787210.2016.1207526

26.

Johnson MD Lewis RE Dodds Ashley ES Ostrosky-Zeichner L Zaoutis T Andes DR et al . Core recommendations for antifungal stewardship: a statement of the mycoses study group education and research consortium. J Infect Dis. (2020) 222:S175–98. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiaa394

27.

Kara E Metan G Bayraktar-Ekincioglu A Gulmez D Arikan-Akdagli S Demirkazik F et al . Implementation of pharmacist-driven antifungal stewardship program in a tertiary care hospital. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. (2021) 65:e0062921. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00629-21

28.

Kawaguchi H Yamada K Imoto W Yamairi K Shibata W Namikawa H et al . The effects of antifungal stewardship programs at a tertiary-care teaching hospital in Japan. J Infect Chemother. (2019) 25:458–62. doi: 10.1016/j.jiac.2019.01.015

29.

Keck JM Cretella DA Stover KR Wagner JL Barber KE Jhaveri TA et al . Evaluation of an antifungal stewardship initiative targeting micafungin at an Academic Medical Center. Antibiotics. (2023) 12:193. doi: 10.3390/antibiotics12020193

30.

Khanina A Cairns KA Kong DC Thursky KA Slavin MA Roberts JA . The impact of pharmacist-led antifungal stewardship interventions in the hospital setting: a systematic review. J Pharm Pract Res. (2021) 51:90–105. doi: 10.1002/jppr.1721

31.

Valerio M Vena A Bouza E Reiter N Viale P Hochreiter M et al . How much European prescribing physicians know about invasive fungal infections management?BMC Infect Dis. (2015) 15:80. doi: 10.1186/s12879-015-0809-z

32.

Reslan Z Lindsay J Kerridge I Gellatly R . Pharmacist review of high-risk haematology outpatients to improve appropriateness of antifungal prophylaxis. Int J Clin Pharm. (2020) 42:1412–8. doi: 10.1007/s11096-020-01090-5

33.

Morii D Ichinose N Yokozawa T Oda T . Impact of an infectious disease specialist on antifungal use: an interrupted time-series analysis in a tertiary hospital in Tokyo. J Hosp Infect. (2018) 99:133–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jhin.2018.01.003

34.

Nwankwo L Periselneris J Cheong J Thompson K Darby P Leaver N et al . Impact of an antifungal stewardship programme in a tertiary respiratory medicine setting: A prospective real-world study. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. (2018) 62:e00402-18. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00402-18

35.

So M Mamdani M Morris A Lau T Broady R Deotare U et al . Effect of an antimicrobial stewardship programme on antimicrobial utilisation and costs in patients with leukaemia: a retrospective controlled study. Clin Microbiol Infect. (2018) 24:882–8. doi: 10.1016/j.cmi.2017.11.009

36.

Martín-Gutiérrez G Peñalva G De Pipaón MR-P Aguilar M Gil-Navarro MV Pérez-Blanco JL et al . Efficacy and safety of a comprehensive educational antimicrobial stewardship program focused on antifungal use. J Infect. (2020) 80:342–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2020.01.002

37.

Samura M Hirose N Kurata T Ishii J Nagumo F Takada K et al . Support for fungal infection treatment mediated by pharmacist-led antifungal stewardship activities. J Infect Chemother. (2020) 26:272–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jiac.2019.09.016

38.

Markogiannakis A Korantanis K Gamaletsou MN Samarkos M Psichogiou M Daikos G et al . Impact of a non-compulsory antifungal stewardship program on overuse and misuse of antifungal agents in a tertiary care hospital. Int J Antimicrob Agents. (2021) 57:106255. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2020.106255

39.

Murakami M Komatsu H Sugiyama M Ichikawa Y Ide K Tsuchiya R et al . Antimicrobial stewardship without infectious disease physician for patients with candidemia: a before and after study. J Gen Fam Med. (2018) 19:82–9. doi: 10.1002/jgf2.159

40.

Rac H Wagner JL King ST Barber KE Stover KR . Impact of an antifungal stewardship intervention on optimization of candidemia management. Ther Adv Infect Dis. (2018) 5:3–10. doi: 10.1177/2049936117745267

41.

Mularoni A Adamoli L Polidori P Ragonese B Gioè SM Pietrosi A et al . How can we optimise antifungal use in a solid organ transplant Centre? Local epidemiology and antifungal stewardship implementation: a single-centre study. Mycoses. (2020) 63:746–54. doi: 10.1111/myc.13098

Summary

Keywords

antifungal, stewardship, pharmacist, consumption, clinical, interventions

Citation

Akbar Z, Aamir M and Saleem Z (2024) Optimizing antifungal therapy: a systematic review of pharmacist interventions, stewardship approaches, and outcomes. Front. Med. 11:1489109. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2024.1489109

Received

31 August 2024

Accepted

18 November 2024

Published

03 December 2024

Volume

11 - 2024

Edited by

L Gayani Tillekeratne, Duke University, United States

Reviewed by

Josh Clement, Mount Sinai Hospital, United States

Ana Afonso, NOVA University of Lisbon, Portugal

Updates

Copyright

© 2024 Akbar, Aamir and Saleem.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Zunaira Akbar, zunaira.akbar@hotmail.com

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.