Abstract

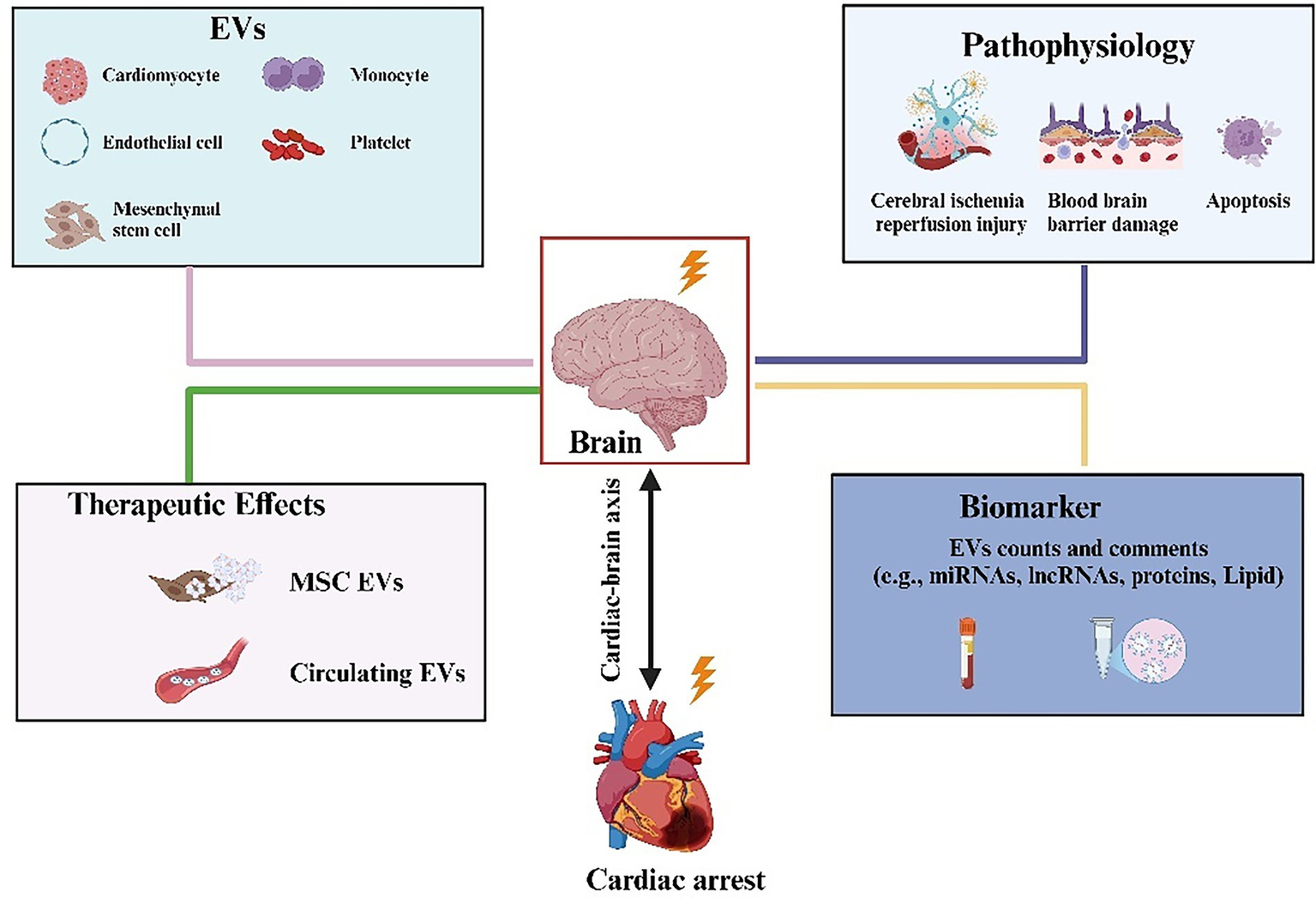

Acute brain injuries (ABI), such as traumatic brain injury, stroke, hypoxia-induced brain injury, and cardiac arrest, are critical and life-threatening conditions that contribute to substantial mortality and long-term disability. Despite extensive translational efforts, no effective therapy has improved long-term functional outcomes, highlighting a critical unmet need. Mesenchymal stem cell-derived extracellular vesicles (MSC-EVs) have emerged as promising cell-free therapeutic platform, offering multifaceted repair capabilities. This review synthesizes current evidence supporting the neuroprotective effects of MSC-EVs, which operate through synchronized immunomodulation, anti-apoptotic signaling, enhancement of neurogenesis, and stimulation of angiogenesis. We further delineated the fundamental EVs biology, including biogenesis pathways, spatiotemporal biodistribution, and blood–brain barrier (BBB) trafficking mechanisms that underpin therapeutic efficacy. Collectively, we established MSC-EV cargo as a strategic solution to unmet neuroprotective needs while mapping clinical translation roadmaps to accelerate the rational development of regenerative neurotherapeutics.

1 Introduction

Acute brain injury (ABI) is a common syndrome with poor prognosis and high disability in the emergency department and intensive care unit (1, 2). This condition encompasses diverse etiologies, including ischemic stroke (IS), traumatic brain injury (TBI), neonatal hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy (HIE), and cardiac arrest (CA), which share common pathophysiological pathways such as excitotoxicity, neuroinflammation, and blood–brain barrier (BBB) disruption (3). Preclinical studies have demonstrated the efficacy of several drugs for mitigating ABI and ameliorating neurological deficits in animal models (4–6). However, these findings have largely failed to translate into successful clinical outcomes. Consequently, the development of novel therapeutic strategies for ABI is imperative.

Accumulating evidence has revealed that mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) and their extracellular vesicles (MSC-EVs) exert therapeutic effects in ABI through multiple mechanisms. These include (1) secretion of neurotrophic factors (e.g., nerve growth factor, epidermal growth factor, and brain-derived neurotrophic factor), (2) inhibition of microglial activation and neuroinflammation, (3) suppression of neuronal apoptosis, and (4) promotion of synaptic remodeling (7, 8). Compared with parental MSCs, MSC-EVs are promising therapeutic candidates for ABI because of their superior BBB penetrability, modifiable membrane properties, enhanced stability, and favorable storage profiles.

Preclinical studies in animal models of middle cerebral artery occlusion (MCAO), TBI, and hypoxic-ischemic brain damage (HIBD) have demonstrated that MSCs and their EVs improve cognitive and motor deficits, correlating with microglial deactivation and reduced release of inflammatory factors (9–13). Proteomic analyses of BMSC-EVs have identified a protein cargo exceeding 700 distinct molecules that are significantly enriched in immune regulation and angiogenic pathways (14). Furthermore, MSC-EVs transport multifaceted bioactive substances, including non-coding RNAs (miRNAs and lncRNAs), genomic DNA fragments, and phospholipid mediators, which orchestrate critical pathophysiological processes, including cellular proliferation, programmed apoptosis, and autophagic flux modulation (15–17). Given their neurorestorative potential in ABI models, MSC-EVs are promising therapeutic candidates. Supporting this, Zhang et al. (18) and Lv et al. (19) collectively demonstrated that MSC-EVs reduced lesion volume and enhanced neurological function in MCAO models, primarily by attenuating neuronal apoptosis and promoting axonal growth.

Despite supporting evidence from multiple studies (Table 1; Supplementary Tables S1, S2), significant heterogeneity exists regarding the optimal EV dosage, administration route, frequency, and timing across preclinical models (18–54). Key translational challenges further limit efficacy: (1) rapid systemic clearance of intravenously administered EVs by macrophages and neutrophils; (2) the BBB acting as a physiological barrier restricting peripheral EV entry into the CNS; and (3) insufficient intrinsic bioactivity and scalable production yields of native EVs, necessitating bioengineering enhancement. Therefore, the therapeutic efficacy of MSC-EVs in preventing ABI remains controversial. To address these limitations, this review comprehensively analyzes the EV biogenesis pathways, systemic biodistribution kinetics, and engineered BBB traversal strategies that leverage receptor-mediated transcytosis. Additionally, we synthesized findings on the therapeutic potential of distinct MSC-EV subtypes in ameliorating non-infectious acute brain injuries. The biogenic pathways of EVs primarily determine their subtype properties through cargo sorting mechanisms and membrane composition, significantly limiting the therapeutic efficacy of EV-based ABI targeting.

Table 1

| Species | Cells | Administration route | Time | Dose of EVs | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C57BL | BMSC | Tail vein | After MCAO | NA | (20) |

| C57BL | BMSC | Tail vein | After MCAO | Released by 2 × 106 MSCs | (21) |

| C57BL | BMSC | Tail vein | 90 min after MCAO | 1010 | (22) |

| C57BL | BMSC | Tail vein | 2 h after reperfusion | 200 μL | (23) |

| C57BL | BMSC | Tail vein | 24 h after MCAO | 200 μg | (24) |

| C57BL | BMSC | Tail vein | 12 h after reperfusion | 300 μg | (25) |

| SD rat | BMSC | Tail vein | The next day of MCAO and 14 day later | 200 μL | (26) |

| SD rat | BMSC | Tail vein | 10 min after MCAO | 100 μg | (27) |

| SD rat | BMSC | Lateral ventricle | 24 h after MCAO | 100 μg | (28) |

| Postnatal day 9–10 C57BL | BMSC | Lateral ventricle/intranasal | At the time of reperfusion | 1 μg/μL or 5 μg/μL | (29) |

| Rat pups | UC-MSC | Tail vein | After MCAO | 150 μg | (30) |

| SD rat | UC-MSC | Tail vein | After MCAO | 100 μg/day for 3 days | (31) |

| SD rat | ADMSC | Lateral ventricle | Before MCAO | 100 μg/kg/day for 4 days | (18) |

| SD rat | ADMSC | Lateral cerebral ventricle | Before MCAO | 100 μg/kg/day for 3 days | (32) |

| SD rat | ADMSC | Tail vein | 1 h after MCAO | 150 μg | (19) |

| SD rat | NSC | Lateral ventricle | 2 h after surgery | 30 μg | (33) |

| SD rat | NSC | Tail vein | After 1 h of MCAO | 300 μg | (34) |

MSC-EVs alleviated ischemia stroke in vivo.

ADMSC, adipose mesenchymal stem cell; BMSC, bone marrow mesenchymal stem cell; MCAO, middle cerebral artery occlusion; NSC, nerve stem cell; UC-MSC, umbilical cord mesenchymal stem cell.

2 Biogenesis of EVs

EVs are lipid bilayer-enclosed nanoparticles that are constitutively secreted by all nucleated cells and serve as key mediators of intercellular communication (55). Based on their biogenic mechanisms and physical properties, EVs are operationally classified into three primary subtypes: (1) exosomes (30–150 nm) originating from endosomal multivesicular bodies; (2) microvesicles (MVs, 50–1,000 nm) generated via plasma membrane budding; and (3) apoptotic bodies (500–2,000 nm) released during programmed cell death (56). EVs with diameters <200 nm is commonly designated as “small EVs” (sEV). Critically, the Minimal Information for Studies of Extracellular Vesicles (MISEV2018) guidelines advocated using the size-based term “small EVs” (sEVs) over biogenesis-based terms like “exosomes” or “microvesicles,” provided size is rigorously determined (57).

Beyond size differences, the three subtypes of EVs originated through distinct biogenesis pathways. Exosome formation commences with the plasma membrane invagination, which generates early endosomes. These endosomes recruit the endosomal sorting complex required for transport (ESCRT) machinery to mediate inward budding, culminating in multivesicular body (MVB) maturation (58). Subsequent MVB docking and fusion with the plasma membrane release intraluminal vesicles into the extracellular space as exosomes (59). Conversely, microvesicles are formed by direct outward budding and fission of the plasma membrane, whereas apoptotic bodies arise from programmed membrane blebbing during cellular apoptosis (59). Compositional profiling of EVs via transmission electron microscopy and western blot revealed enrichment of the characteristic components, including sphingomyelin, cholesterol, phosphatidylserine, tetraspanins (CD9, CD63, and CD81), and heat shock proteins (HSP70 and HSP90). Furthermore, EVs encapsulate diverse donor cell-derived cargos, including nucleic acids (genomic DNA, mRNA, miRNA, and siRNA) and functional proteins (60). These bioactive payloads, particularly miRNAs, mediate the cross-cellular regulation of cell proliferation and apoptosis through recipient cell internalization via endocytic pathways.

In the pathophysiology of ABI, EVs secreted by bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells (BMSCs), adipose-derived mesenchymal stem cells (ADMSCs), and neural progenitor cells (NPCs) mediate neuroprotection through two mechanisms: (1) inhibition of caspase-3-dependent apoptotic pathways and (2) attenuation of reactive oxygen species (ROS)-induced oxidative stress. This concerted action promoted neural circuit repair (61, 62). Similar to the role of biogenic pathways, the in vivo distribution of EVs, particularly their accumulation in the brain, critically governs the efficacy of EV-based therapeutics for ABI. Subsequently, we delineated the systemic distribution patterns of EVs and the mechanisms underlying their traversal across the BBB.

3 Biodistribution of BMSC-EVs

The therapeutic efficacy of peripherally administered MSC-EVs requires efficient biodistribution to the cerebral parenchyma, necessitating the optimization of intracranial delivery strategies (63). EVs biodistribution is route dependent and is influenced by parental cell tropism and surface molecular signatures (63). Intravenous administration triggers rapid clearance by the mononuclear phagocyte system, with residual vesicles predominantly accumulating in hepatic Kupffer cells, renal proximal tubules, and splenic macrophages (64, 65). Comparatively, intranasal delivery achieved significantly higher brain EV concentrations via the olfactory ependymal bypass pathway (64). Crucially, EVs distribution correlated with cellular origin; MSC-EVs were localized primarily to the liver, lungs, and spleen, whereas microglia-derived EVs showed abundant hepatic and cerebral accumulation (66). Consistently, NSC-EVs demonstrated superior intracranial distribution over BMSC-EVs in MCAO models (67).

The EVs membrane surface displayed functionally critical transmembrane proteins, lipids, and glycans, predominantly featuring tetraspanins (CD9/CD63/CD81), integrins (α4β1/α5β1), and major histocompatibility complexes. Notably, EVs co-expressing quadruple transmembrane proteins and integrin α4 exhibit enhanced tropism toward endothelial cells (68). Phosphatidylglycines and polysaccharides concurrently modulate cellular uptake of MSC-EVs (69). These findings establish a rationale for achieving intracranial EV targeting through engineered modifications of surface molecules via chemical conjugation or genetic engineering (70). Critically, the biodistribution of MSC-EVs is correlated with their pathophysiological state. In a comparative study of AKI and healthy mice, intravenous MSC-EVs showed accelerated renal accumulation in an AKI cohort (70). Similarly, macrophage-derived EVs demonstrated a 3-fold increase in BBB transmigration during intracranial inflammation compared to that under physiological conditions (71).

4 Mechanism of transport of MSC-EVs across the blood–brain barrier

The synthesis and biological distribution of MSC-EVs have been described previously. In this section, we analyze the mechanism of MSC-EV transport across the BBB. Evidence indicates that peripherally administered MSC-EVs must traverse the BBB to exert neuroprotective effects. Central nerve markers, including α-synuclein and microtubule-associated proteins, have been detected in EVs derived from peripheral organs and blood under physiological and pathological conditions (72, 73). Furthermore, EVs have been established as mediators of CNS-peripheral communication (74). However, the mechanisms underlying EV transport across the BBB remain unclear.

The BBB, a selective interface between systemic circulation and CNS, dynamically regulates molecular exchange to maintain homeostasis and excludes neurotoxic agents (75). This constitutes the primary obstacle to the development of CNS-targeted therapeutics. Under physiological conditions, the BBB selectively allows several small substances, such as lipid- and water-soluble small molecules, to enter the brain tissue (76). However, molecules greater than 1 KD cannot cross this barrier (75). A minority of large molecules, such as carbohydrates and essential amino acids, can cross the BBB via transporter proteins and receptors on the surface of endothelial cells (76). Hydrophilic molecules, such as hormones and lipoproteins, can cross the BBB via transcytosis (77).

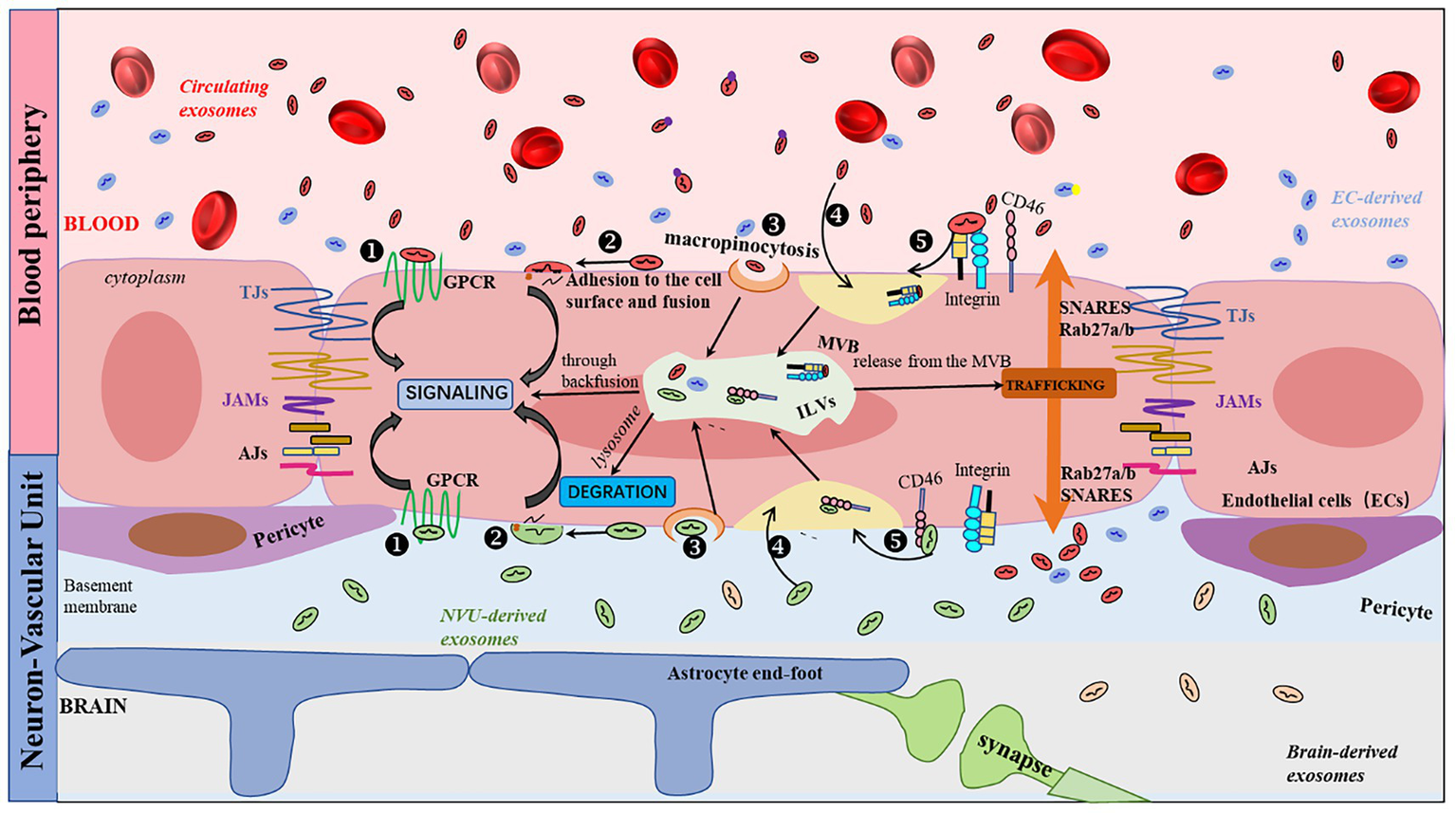

Currently, the mechanism by which EVs cross the BBB remains to be fully understood; however, five theoretical routes have been suggested: G protein-coupled receptor-mediated transport, macropinocytosis, transcytosis, lipid rafts, and receptor-mediated transcytosis (Figure 1). Among these, clathrin-mediated transcytosis is crucial for receptor-mediated transcytosis (74). When ligands bind to receptors, ligand-receptor compounds are concentrated in clathrin-coated pits created by clathrin and adaptor proteins. Once clathrin-coated pits are separated from the plasma membrane, the vesicles lose their clathrin coat and fuse with early endosomes. Finally, the cargo is sorted and released on the opposite sides of the cell membrane (78). In a BBB model, Zhao et al. (79) identified that HEK 293-derived EVs cross the BBB via receptor-mediated endocytosis, lipid rafts, and macropinocytosis. In contrast, Terasaki et al. (80) revealed that EVs transport across the BBB was highly linked to integrins and CD46 on the endothelial cell surface, and that the number of EVs crossing the BBB decreased 2-fold after CD46 knockdown. Upon entering the cerebral microvascular endothelium, most EVs bind to lysosomes and are rapidly degraded; some fuse inversely with MVB and release their contents into the cytoplasm. The remaining EVs fuse with the plasma membrane via the MVB to form new ILVs (Figure 1).

Figure 1

Schematic representation of the EVs transport pathway across the BBB. Five routes have been described for the interaction of EVs with receiving cells: (1) binding to protein G-coupled receptors on the cell surface, leading to the induction of signaling cascades; (2) adhesion and fusion to the cell surface, releasing the cytoplasmic content of EVs, which can result in a variety of events, including cellular signaling; (3) macropinocytosis; (4) nonspecific/lipid rafts; and (5) receptor-mediated transcytosis. There are three common outcomes of EVs: (i) degradation by lysosomes, (ii) induction (87) of signaling by releasing their contents into the cytoplasm through back-fusion events of the MVB, or (iii) translocation from the MVB to the plasma membrane as neoformed ILVs in the recipient cell.

5 MSC-EVs in ABI

5.1 Ischemic stroke and MSC-EVs

Ischemic stroke is one of the leading causes of death worldwide, and approximately 75% of survivors suffer from disabilities (81). Current FDA-approved therapies, such as recombinant tissue-type plasminogen activator (rt-PA) and endovascular thrombectomy, remain limited by narrow therapeutic windows and stringent eligibility criteria (82, 83). Therefore, novel strategies are urgently required to mitigate I/R injury and improve neurological outcomes. Stem cell-derived EVs have significant neuroprotective effects in ischemic stroke models. BMSC-EVs are the most extensively studied subtype, followed by adipose mesenchymal stem cell-derived EVs (ADMSC-EVs) and umbilical cord-derived MSC-EVs (UCMSC-EVs) (60).

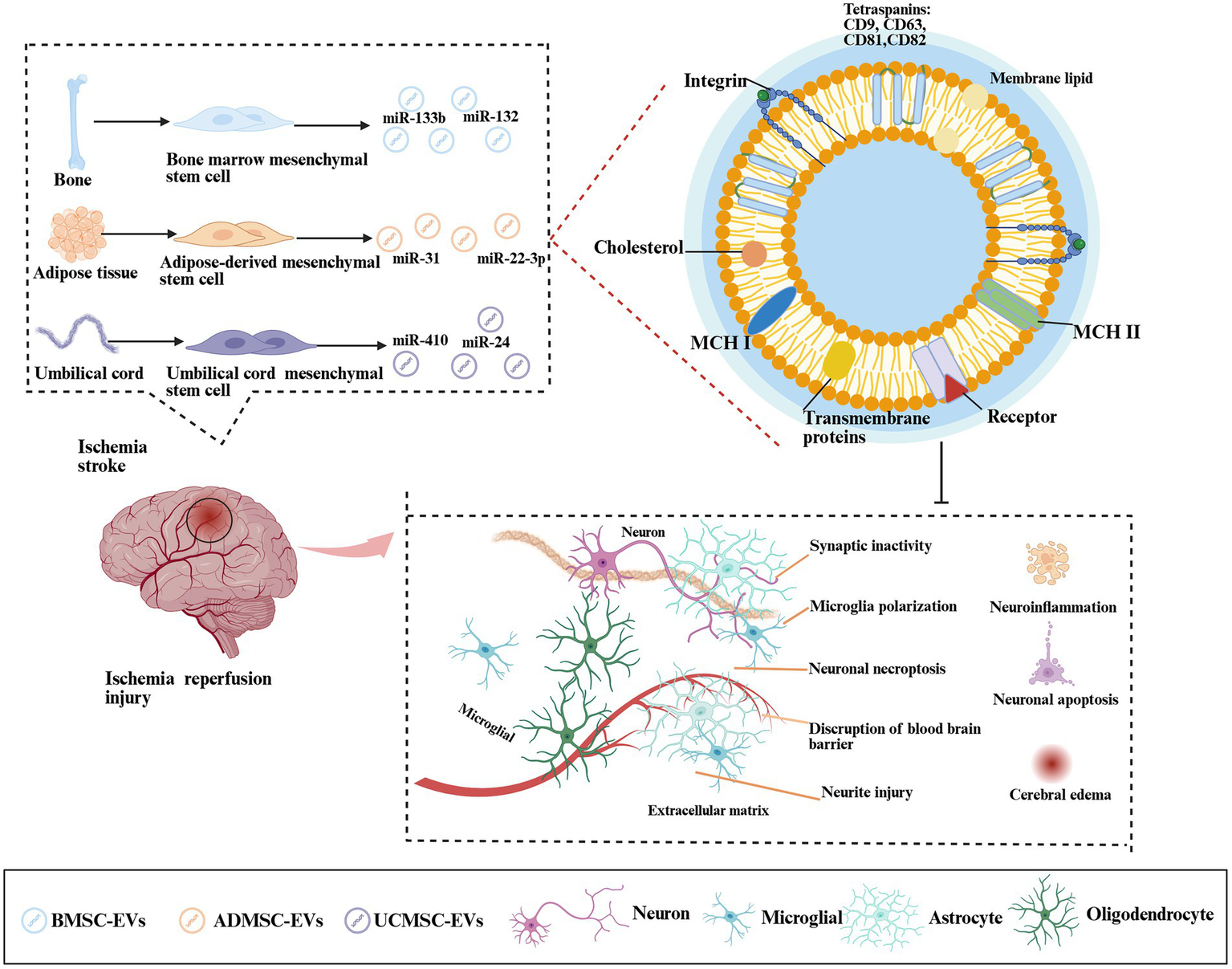

BMSC-EVs alleviate post-ischemic neuronal damage via various mechanisms, including immunomodulation, anti-apoptosis, inhibition of autophagy and oxidative stress, promotion of neuronal proliferation, and BBB improvement (Figure 2). These effects were mediated through key pathways: AMPK/mTOR, ACVR2B/p-Smad2/c-Jun, and JAK/AKT/GSK-3β/Wnt3 (21, 30, 84). A recent study confirmed that BMSC-EVs suppress neuronal apoptosis, decrease lactate dehydrogenase release, and promote neuronal proliferation after stimulation with oxygen-glucose deprivation/reoxygenation (84). Similarly, Feng et al. (24) revealed that BMSC-EV-derived miR-132 inhibits neuronal apoptosis via the Acvr2b/p-Smad 2/c-jun pathway (Figure 2).

Figure 2

Mechanism by which MSC-EVs regulate cerebral ischemia-reperfusion injury. Ischemic stroke triggered cerebral hypoxia-ischemia, driving pathological cascades—metabolic dysfunction, cellular edema, microglial polarization, neuroinflammation, blood–brain barrier (BBB) disruption, and synaptic damage. BMSCs, ADMSCs, and UCMSCs secreted EVs that delivered miRNAs (miR-133, miR-132, and miR-31) to mitigate neuroinflammation, inhibit neuronal apoptosis, reduce edema, and promote cognitive recovery.

In the MCAO model, BMSC-EVs-derived-miR-133b attenuated neuronal injury by targeting JAK1, thereby suppressing the release of inflammatory factors (85). Similarly, miR-132-3p enrichment in BMSC-EVs achieved via donor cell overexpression activates the Ras/PI3K/p-Akt/eNOS pathway, enhancing BBB integrity and cerebral perfusion (22). Parallel engineering approaches generated miR-26a-5p-enriched BMSC-EVs that inhibited CDK6 expression and microglial apoptosis (86), as well as miR-223-3p-modified BMSC-EVs that suppressed M1 microglial polarization, reduced pro-inflammatory cytokines, diminished infarct volume, and improved neurological scores (26).

ADMSC-EVs demonstrated comparable neuroprotective efficacy by reducing neuronal apoptosis, autophagy, and infarct volume (18). Zhang et al. (18) showed that ADMSC-EV-derived miR-22-3p targets KDM6B, which inhibits neuronal apoptosis via the BMP/BMF signaling pathway. Lv et al. (19) reported that the miR-31-mediated blockade of the TRAF6/IRF5 axis improved post-injury motor function. Notably, genetically engineered PEDF-ADMSC-EVs exhibit significantly enhanced anti-apoptotic activity relative to their unmodified counterparts (32), inhibiting neuronal apoptosis more efficiently than conventional approaches.

Umbilical cord MSC-derived EVs (UC-MSC EVs) modulate neuroinflammation by suppressing M1 glial polarization and attenuating inflammatory responses (87). These vesicles delivered miR-24 to downregulate AQP4 expression and activate the p38 MAPK/ERK/PI3K/AKT pathway, thereby collectively ameliorating ischemia-reperfusion-induced neuronal apoptosis (87).

5.2 Traumatic brain injury and MSC-EVs

Traumatic brain injury (TBI), a serious global public health problem, is a frequent and severe neurological illness encountered in emergency medicine (88, 89). Annually, more than 27 million cases of TBI are reported worldwide. TBI survivors frequently experience persistent cognitive, motor, and memory deficits, which are the leading causes of mortality and disability in adults under 45 years of age (88). Pathophysiologically, primary mechanical insults induce cerebral hemorrhage and tissue edema, whereas secondary injury cascades trigger excitotoxicity, mitochondrial dysfunction, neuroinflammation, axonal degeneration, and apoptosis (17). Current clinical management stratifies patients by severity: patients with mild to moderate TBI receive medical interventions, including intracranial pressure control, seizure prophylaxis, and targeted temperature management, whereas those with intracranial hematomas or severe contusions require surgical decompression (88, 89). Although these approaches mitigate acute symptoms and preserve vital function, they fail to address the underlying pathomechanisms, leaving long-term recovery contingent on endogenous repair processes. Emerging preclinical evidence has demonstrated that BMSC-EVs and ADMSC-EVs suppress post-TBI neuroinflammation and significantly improve functional recovery metrics in animal models (90, 91).

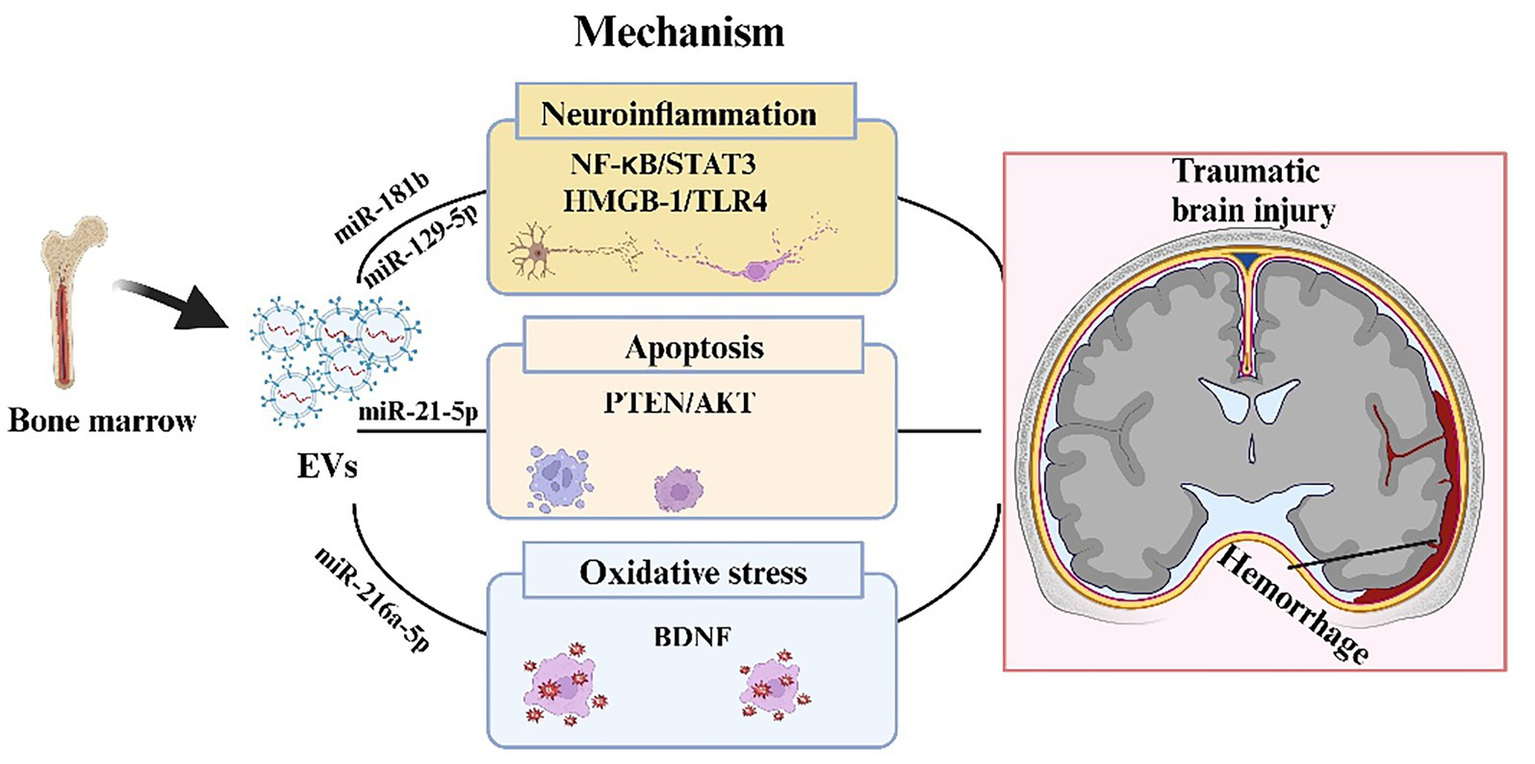

BMSC-EVs effectively improve brain injury after TBI through multifaceted mechanisms, including regulating microglial activation, reducing neuroinflammatory factors and oxidative stress responses, improving cerebral perfusion, and promoting angiogenesis (Figure 3) (35, 92). These effects are primarily mediated by EV-encapsulated miRNAs. The miR-181b/STAT3 axis is a key regulator of neuroinflammation, with BMSC-EVs suppressing NF-κB activation to mitigate post-TBI inflammatory responses (37). Parallel findings revealed that miR-216a-5p from BMSC-EVs enhanced neuroplasticity by modulating BDNF-dependent mechanisms, significantly improving spatial learning in TBI models through the coordinated regulation of cell migration and apoptosis (43). Complementary studies have demonstrated that the miR-17-92 cluster confers hippocampal neuroprotection, preserving dentate gyrus integrity, while stimulating neovascularization and neurological recovery (42).

Figure 3

Mechanism of BMSC-EV regulation of traumatic brain injury. In the process of traumatic brain injury, BMSC-EVs during traumatic brain injury, BMSC-EVs transported a variety of miRNAs, which can suppress the expression of target genes and regulate neuroinflammation, apoptosis, and oxidative stress, involving several signaling pathways such as NF-kB/STAT 3, HMGB-1/TLR4 and PTEN/AKT.

In addition to their direct neuronal effects, BMSC-EVs exhibit pronounced cerebrovascular benefits. While failing to modulate systemic hemodynamics in porcine TBI models, they significantly reduced intracranial pressure while enhancing cerebral perfusion (93). This vascular modulation was extended to subarachnoid hemorrhage models, where miR-21-5p-enriched BMSC-EVs ameliorated cerebral edema and cognitive deficits through PTEN/AKT pathway inhibition (39). Notably, similar neuroprotection was achieved via the miR-129-5p-mediated suppression of HMGB1/TLR4 signaling (38). suggesting conserved mechanisms across injury models (Figure 3). Collective evidence suggests that BMSC-EVs are multimodal therapeutic agents capable of simultaneously targeting neuroinflammation, vascular dysfunction, and excitotoxicity with particular efficacy against glutamate-mediated neurotoxicity and p38 MAPK activation (36). These findings underscore the translational potential of EV-based interventions in complex TBI pathophysiology.

Apart from BMSC EVs, ADMSC-EVs also repressed microglia and macrophage cell activity, relieved TBI impairment by suppressing the NF-κB and MAPK pathways (44). Intracardial injection of UC-MSC EVs into neonatal rats with ventricular hemorrhage significantly improved the motor coordination of injured rats (94). UC-MSC EVs also attenuated inflammation and apoptosis, while the neuroprotection can be reversed when BDNF expression was downregulated (94). Notably, Li et al. (95) found that exfoliated deciduous teeth cell-derived EVs inhibited the release of inflammatory factors and reduced cortical lesion volume in TBI rats.

5.3 Neonatal hypoxic-ischemic damage and MSC-EVs

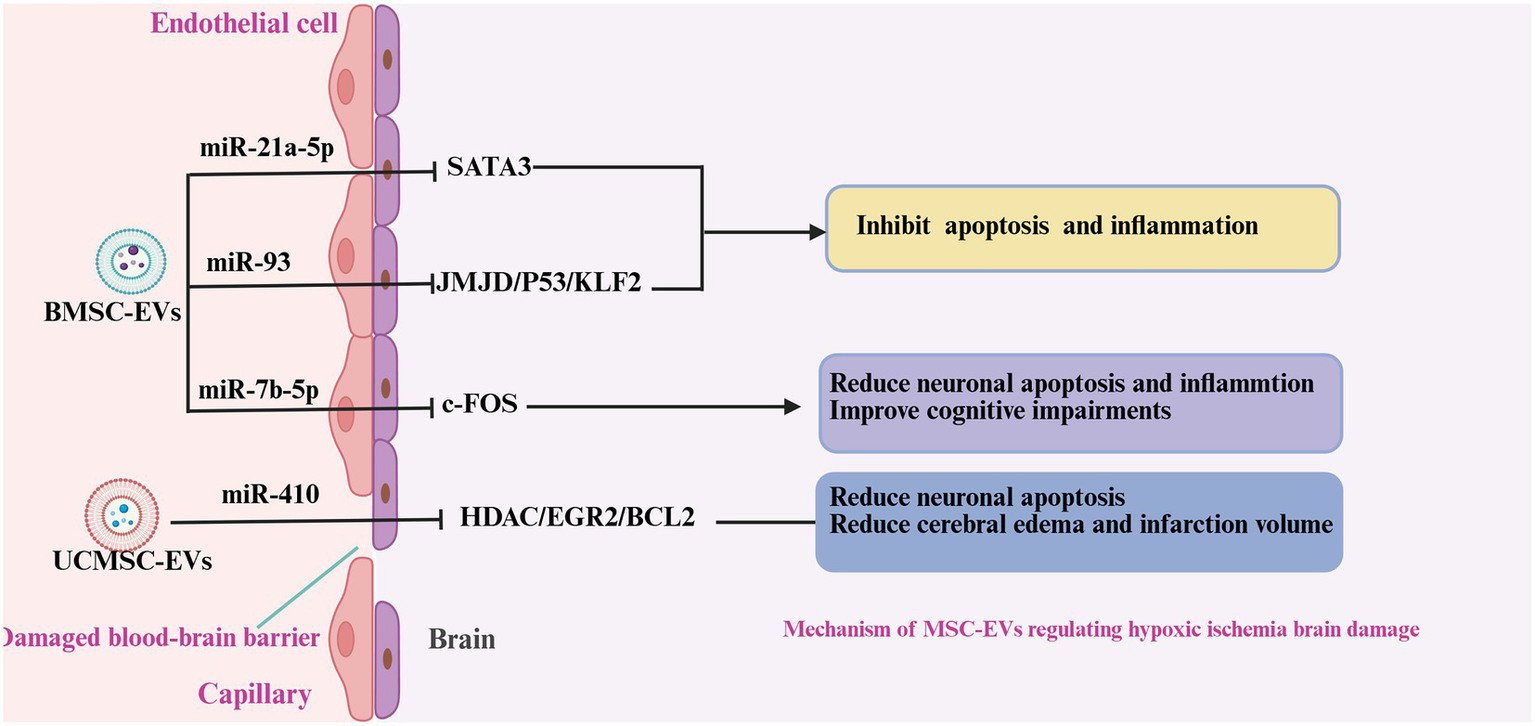

Neonatal hypoxic-ischemic damage (HIBD) is a serious neurological disorder caused by perinatal asphyxia, characterized by partial or complete deprivation of cerebral oxygen supply and blood flow during the perinatal period (31, 96). Current clinical management is limited to supportive care, highlighting the urgent need for effective therapeutic interventions. Emerging evidence suggests that MSC-EVs may exert neuroprotective effects by modulating neuroinflammatory responses and improving neurological outcomes in patients with neonatal HIBD (Figure 4).

Figure 4

Mechanism of MSC-EVs regulating neonatal hypoxic-ischemic damage. In neonatal ischemic-hypoxic brain injury, BMSC-EVs and UCMSC-EVs released various miRNAs to attenuate the neuroinflammation, neuronal apoptosis, and promote the BBB. Reduced microglia polarity, inhibited inflammation and apoptosis, promoted neuronal proliferation, and reduced brain edema.

BMSC-EVs attenuate pro-inflammatory cytokine release, upregulate neurotrophic factors (e.g., BDNF, VEGF, and EGF), and enhance neuronal and vascular endothelial cell proliferation in the subventricular area (44). These neuroprotective effects are mediated by specific miRNAs such as miR-21a-5p and miR-93, which modulate the SATA3 and JMJD/P53/KLF2 signaling pathways, respectively (48, 97). In a hypoxia-ischemia injury model, intracardiac BMSC-EV administration reduced microglial and macrophage activation, inhibited aberrant neuronal phagocytosis, and restored synaptic integrity (46). A previous study on hypoxia-ischemia injury showed that intracardiac injection of BMSC-EVs reduced microglial and macrophage activity, suppressed microglial phagocytosis in normal neurons, and restored neuronal synapses (49). This anti-inflammatory effect is also associated with the inhibition of P38-MAPK and NF-κB activation by BMSC-EVs (52). In contrast to the above findings, Ophelders et al. (53) revealed that BMSC-EVs did not attenuate neuroinflammation in ischemic-hypoxic fetuses but reduced seizure frequency and duration. To strengthen the neuroprotective function of BMSC-EVs, Chu et al. (47) modified BMSC-EVs with hydrogen sulfide and found that post-modification EVs were more abundant in miR-7b-5p. It suppressed c-Fos expression and inhibited the release of inflammatory factors. Osteopontin (OPN), an extracellular matrix glycoprotein, may exacerbate neuroinflammation following cerebral hemorrhage and ischemic or hypoxic brain injury (98, 99). OPN expression is suppressed by BMSC-EVs, which is accompanied by reduced inflammation (49).

Previous studies have shown that UC-MSC-EVs can reduce inflammation in post-ischemic hypoxic brain injury. In vitro, UC-MSC EVs upregulated FOXO 3a expression, attenuated microglial pyroptosis, and promoted proliferation after oxygen-glucose deprivation (100). In vivo, the intranasal administration of UC-MSC EVs also suppressed microglial activation and inflammatory factor release to alleviate hypoxic brain injury (46). Han et al. (45) demonstrated that UC-MSC-derived EVs are anti-apoptotic and inhibit inflammation, and reported that these effects were associated with the inhibition of the HDAC/EGR2/Bcl-2 pathway by UC-MSC EVs derived from miR-410.

5.4 Cardiac arrest and MSC-EVs

Cardiac arrest (CA) is a critical illness that causes acute death and disability worldwide. The survival rate for in-hospital cardiac arrest discharges has been reported to be 7–26% (101, 102). Most survivors suffer from different extents of neurological deficits due to ischemic-hypoxic brain injury (103, 104). To date, there is a lack of effective drugs to alleviate post-resuscitation brain injury (105).

Although there are few studies on EVs for cardiopulmonary resuscitation, several reports have indicated that EVs play a crucial role in post-resuscitation brain injury. Empana et al. (106) and Sinning et al. (107) found a significant increase in the number of monocyte-and endothelial cell-derived EVs after cardiac arrest. Among patients with STEMI, plasma vesicles were significantly larger in diameter and had elevated levels of GP IIb and PLP-1 in those who experienced out-of-hospital cardiac arrest (OHCA) (108). Based on these findings, Fink et al. (109) detected the expression of three different cell-derived EVs in resuscitated patients. Monocyte- and endothelial-derived EVs were significantly elevated in resuscitated patients, whereas platelet-derived EVs were maintained at normal levels (Figure 5). Among these EVs, monocyte-derived EVs are novel predictors of 20-day survival. Furthermore, a previous study on plasma EVs RNA expression in cardiac arrest/cardiopulmonary resuscitation patients identified that 5,231 lncRNAs and 706 miRNAs were significantly altered (Figure 5). These lncRNAs and miRNAs are mainly responsible for cytokine receptors, cholinergic synapses, mitochondrial respiratory chains, ion channels, and apoptosis (110). Shi et al. (54) reported that BMSC-EVs improve spatial learning and memory capacity in resuscitated rats. This is primarily attributable to the inhibition of neuroinflammation and apoptosis, which promote neurogenesis and angiogenesis. Further studies have shown that this anti-apoptotic and neuroprotective function is relevant to BMSC-EVs derived miR-133b, which regulates the JAK1/AKT/GSK-3β/WNT pathway (85).

Figure 5

Active participation of EVs from different cellular sources in neuron repair after cardiopulmonary resuscitation. The contents and number of vesicle contents released by various cells, such as erythrocytes, platelets, monocytes, and mesenchymal stem cells, are altered in patients after cardiopulmonary resuscitation. It can be used as a predictor to assess the neurological prognosis of patients after resuscitation.

6 Discussion

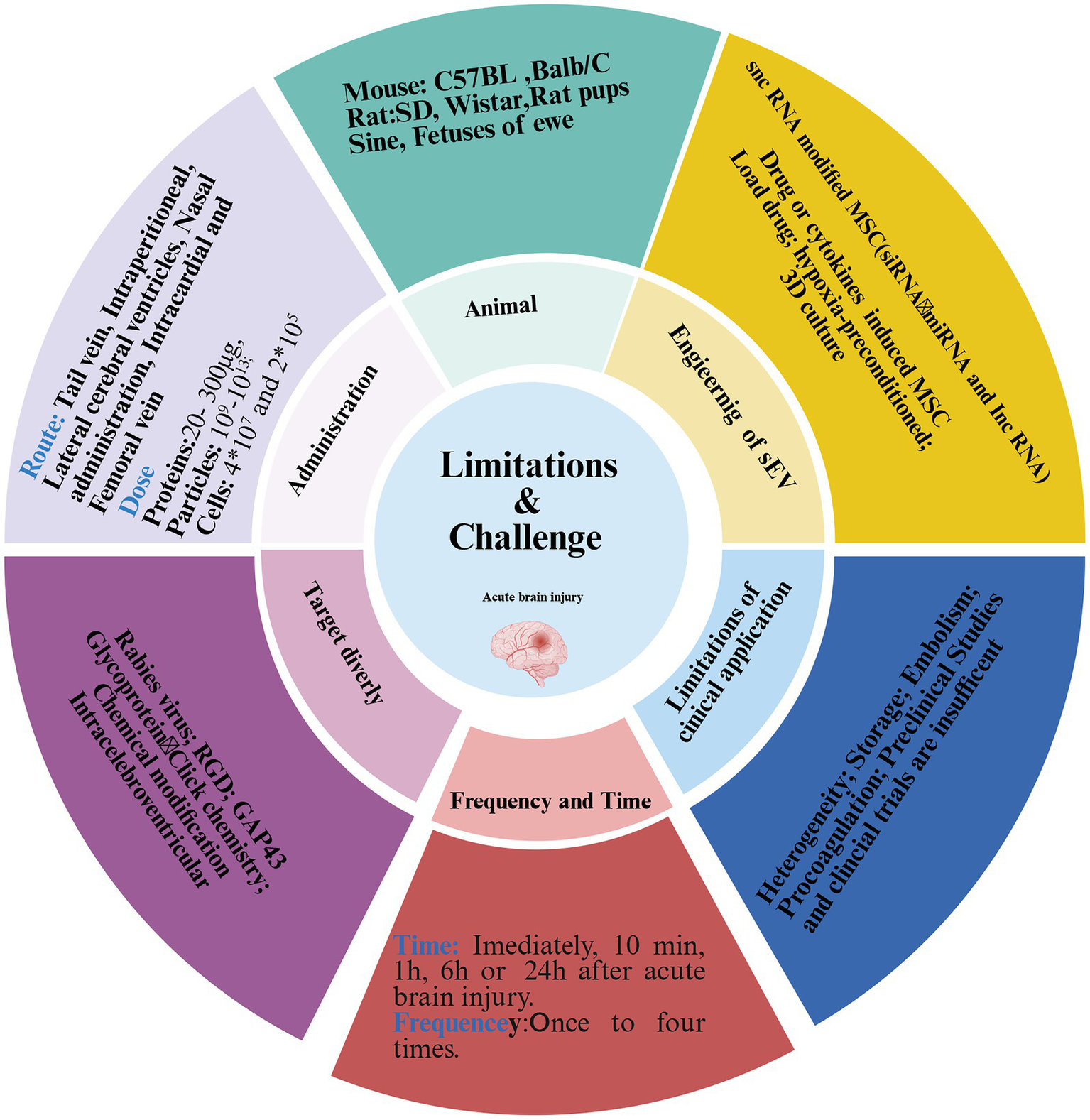

6.1 Ambiguities in the dosage and criterion for the treatment of ABI with MSC-EVs

Despite extensive evidence supporting the therapeutics potential of MSC-EVs for ABI, their clinical translation remains limited due to inconsistent preclinical outcomes and a lack of standardized protocols. Substantial ambiguity persists in key experimental parameters, including animal models, dosage, route of administration, and frequency. First, critical methodological inconsistencies existed across studies, particularly in dosing strategies that frequently neglected injury heterogeneity, species differences, animal body mass, and administration routes (111). Second, experimental models range from rodents (mice and rats) to large mammals (pigs and sheep), while delivery approaches (including intravenous, intraperitoneal, intracardiac, intracerebroventricular, and intranasal) differ considerably in both frequency (single to quadruple administration) and dosimetry criteria (Figure 6). The latter manifests as divergent metrics. Most studies employed total protein quantification, whereas others referenced particle counts or cellular equivalence (Figure 6). These discrepancies lead to significant variability in therapeutic outcomes, even within identical ABI models. For instance, reported doses of intravenous BMSC-EVs in murine MCAO models range from 200 to 300 μg (24, 112). A dose–response study on MSC-EVs therapy for TBI found that 100 μg was more effective than 200 μg in promoting angiogenesis and improving neurological deficits (41). In vitro models of ABI further suggest an optimal MSC-EVs dose range of 40–50 μg/mL (Supplementary Table S3) (34, 41, 84, 113–116). Due to variations in models, species, and administration time, we recommend that further studies systematically evaluate concentration gradients and time gradients when applying EV-base therapies for ABI. Third, it is important to note that ABI, especially ischemic stroke, often occurs in elderly patients with comorbidities such as hypertension. However, most current ABI models are established in young, healthy rodents without underlying conditions, which limits their clinical relevance. Therefore, we recommend that future relevant studies refer to research on MSC-EVs therapy for stroke and Alzheimer’s disease by using aged or diabetic mice (117, 118). Finally, as described previously, although tail vein injection was the predominant route of administration, phagocytosis by macrophages and differences in tissue distribution in the bloodstream greatly reduced the bioavailability of BMSC-EVs (64, 65).

Figure 6

Limitations and challenges of EVs in ABI treatment. Despite many animal model studies demonstrating that MSC-EVs attenuate acute brain injury, there was significant variability in these studies, including animal species, models, dosage, route, and frequency. The heterogeneity, mass production, and storage of MSC-EVs remained to be overcome, and targeting brain transport was also difficult. Furthermore, the side effects of BMSC-EVs have rarely been reported, and preclinical studies are insufficient.

According to their findings, a single intravenous dose of 100 mg is reasonable for EVs in the treatment of ABI (119). And intracerebroventricular injection may be the optimal route of administration to increase the concentration of EVs in brain tissue (120). Furtherly, we also recommend that both nanoparticle tracking analysis and total protein be quantified in prospective studies of MSC-EVs therapy for ABI in accordance with MISEV guidelines. This may facilitate comparisons of efficacy between different studies.

6.2 Safety and potential adverse effects of MSC-EVs

In addition to the lack of standardized dosages and administration protocols, the safety profiles and potential adverse effects of EVs are often neglected by researchers. Research on MSC-EVs for ABI has often followed highly similar pathways, lacking objective evaluation criteria, with a tendency to overemphasize therapeutic benefits while overlooking potential complications. Previous studies reported that EVs may facilitate carcinogenesis under certain conditions (121, 122). For instance, lung macrophages exposed to asbestos release EVs that induce epithelial-mesenchymal transition in pulmonary interstitial cell (123). This pro-oncogenic effect may be attributable to EV-carried miRNAs, arsenic-induced EVs from hepatic epithelial cells, for example, deliver miR-155-5p, activating NF-κB and creating a tumor-favorable inflammatory microenvironment (124).

Beyond carcinogenicity, other documented risks include off-target effects, immune activation, genotoxicity, and thrombotic complications (125). Although the high target specificity of natural EVs may reduce the likelihood of off-target toxicity. This remains a common concern in therapeutic application (125). Some studies may attempt to enhance efficacy by increasing intracranial EV concentrations through higher dose, but this raises the risk of immune reactions and thrombosis. EVs exhibit a tendency to aggregate due to poor zeta potential, which can trigger immune responses (126, 127). MSC-EVs carry proteins such as tetraspanins, integrins, and MHC-I, which are recognized by immune cells. Furthermore, bacterial endotoxins contamination in EV preparations could lead to septic complication. The immunogenicity of MSC-EVs depends on factors including the differentiation state of the parent cells, vesicle size, cargo composition, storage conditions, and infusion rate (128). EVs derived from highly differentiated or large parental cells are particularly prone to inducing immune response (128). Several reports have found that MSC-EVs influence coagulation pathways (129–131). ADMSC-EVs shorten clotting time via both the extrinsic and intrinsic pathway (129). Similarly, UC-MSC-EVs also promote coagulation process in a dose-and tissue factor-dependent manner (130). This effect may be mediated by TF expression on EVs, which enhances FXa production and accelerates clot formation (131). Pre-treatment with heparin has been shown to mitigate EV-induced thrombosis and reduce pulmonary embolism risk in vivo (130).

6.3 Major challenges in the clinical translation

Despite the considerable therapeutic potential of MSC-EVs, their clinical translation remains protracted. Analysis of trial registries1 indicated predominant applications for COVID-19, ARDS, and metabolic diseases, with ABI representing a minority indication (119, 132). This delayed translation reflects multidimensional challenges wherein production standardization constitutes a primary bottleneck: heterogeneous isolation techniques, including ultracentrifugation, microfluidics, and immunocapture, yield preparations with significant variations in size, cargo composition (e.g., miRNAs/proteins), and functional reproducibility (132). Safety assessment remains paramount. Maximizing the purity of MSC-EVs by minimizing manufacturing-derived impurities is essential (133). In vitro toxicity studies indicate that MSC-EVs were free from bacterial endotoxins, and show no genotoxic, hemolytic, platelet-aggregating or complement-activating properties. However, high doses can promote leukocyte proliferation. In contrast, bovine milk-derived EVs have been shown to contain endotoxins capable of inducing hemolysis, platelet aggregation, and complement activation, with adverse effects intensifying at higher concentrations (134). It is estimated that systemic EV therapy in humans may require approximately one trillion MSC-EVs per administration (135).

6.4 Critical perspective

To alleviate neurological impairment following ABI, numerous strategies have been explored, including antioxidants or NMDA receptor antagonists aimed at mitigating neuroinflammation (5, 136). However, these conventional neuroprotective agents are limited by single-target specificity, poor BBB penetration, and significant side effects, rendering them inadequate against the multifaceted pathology of ABI (137). In contrast, MSC-EVs serve as natural nanocarriers with excellent biocompatibility and high BBB permeability (13). They enable multi-mechanism regulation through the delivery of diverse bioactive molecules (e.g., miRNAs, proteins), suppressing neuroinflammation, reducing oxidative stress, promoting angiogenesis, and facilitating synaptic remodeling. Moreover, MSC-EVs can be engineered to enhance targeting and therapeutic efficacy, overcoming key limitations of conventional drugs (17). Surface modifications with targeting ligands, such as (arginine-glycine-aspartate) RGD peptides, which bind integrins on endothelial cells, can improve uptake and delivery (138–140). For example, RGD-C1C2-modified ReN cell-derived EVs facilitate targeted intracranial delivery and enhance anti-inflammatory effects in MCAO mice (34). The rabies virus glycoprotein (RVG), a neuron-specific viral peptide, has been employed to generate neuron-targeted delivery. Yang et al. (141) developed RVG-LAMP-modified BMSC-EVs that achieved successful brain-targeted delivery. Recent approaches also include click chemistry and metabolic labeling for attaching functional groups or therapeutic molecules to EV surfaces (63). Thus, MSC-EVs represent an innovative and comprehensive neurorepair strategy, offering the potential to overcome the efficacy barriers of conventional neuroprotection (14).

Despite promising advances in the use of MSC-EVs for ABI therapy, several challenges must be addressed to enable clinical translation. First, there is an urgent need to establish standardized preclinical frameworks, including, animal models, genetic backgrounds, administration routes (e.g., intravenous vs. intracerebroventricular), dosing metrics (particle count/protein mass), treatment frequency, and functional endpoints, to enable cross-study comparability. Second, scaling production under Good Manufacturing Practice (GMP)-compliant condition remains a major hurdle. Innovative isolation platforms and strict quality control, including purity, potency and reproducibility, are essential (138, 142). MSC-EVs products must comply with Food and Drug Administration (FDA) guidelines, requiring full disclosure of chemical, manufacturing, and control (CMC) information (135). Third, while MSC-EVs possess innate homing capabilities, their targeting efficiency remains suboptimal within the complex milieu of neuropathological injury. Engineering strategies are therefore essential to improve cell-type specificity and delivery precision (143). Forth, the inherent heterogeneity of BMSC-EV preparations must be addressed through genetic or pharmacological preconditioning approaches, which enhance therapeutic efficacy by modulating bioactive cargo (22, 144). For example, BDNF-overexpressing HEK293-derived EVs conferred 3.2-fold greater neuroprotection against ischemia-reperfusion-induced neural apoptosis compared with unmodified EVs (145). Fifth, comprehensive toxicological profiling of MSC-EVs is imperative, particularly concerning procoagulant tendencies and immunogenic reactions. Strategies to mitigate these risks include reducing injection frequency, employing genetic editing to downregulate MHC-I expression, pretreating with heparin, and administering infusions at slower rates to minimize coagulation activation (125). It is also critical to recognize that EVs derived from diverse cellular sources—such as endothelial cells, microglia, astrocytes, and MSCs—exhibit distinct functional profiles and collectively contribute to the pathophysiology of ABI (114, 146). Most prior studies have focused exclusively on a single EV type, overlooking this complex intercellular communication.

Looking ahead, engineering modifications represent a promising avenue for enhancing the neuroprotective effects of MSC-EVs and constitute a major future direction for the field. Robust clinical evaluation will require large-scale, multicenter collaborative efforts (147). Close collaboration among researchers, regulators, clinicians and industry partners is crucial for accelerating the translation and commercialization of MSC-EV-based therapies. Engagement with patient advocacy groups and other stakeholders will further ensure that development is ethical, equitable, and focused on patient accessibility and affordability (148). By addressing these challenges through shared standards and collaborative science, MSC-EV therapies may soon offer safe, effective, and accessible treatments for patients with ABI. Standardized protocols, best practices, and open knowledge exchange will be vital to fully realize the potential of this promising therapeutic approach (148). With technological advances and better understanding, MSC-EVs are expected to become an attractive therapeutic option for alleviating ABI and improving neurological prognosis.

Statements

Author contributions

FZ: Software, Writing – review & editing, Methodology, Writing – original draft, Funding acquisition, Formal analysis, Data curation, Validation. HW: Formal analysis, Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing – original draft. XZ: Formal analysis, Investigation, Software, Data curation, Supervision, Writing – original draft. RH: Investigation, Software, Data curation, Writing – original draft, Methodology, Formal analysis. XJ: Investigation, Writing – original draft, Data curation, Methodology, Formal analysis. HD: Writing – original draft, Investigation, Software, Data curation, Methodology, Conceptualization, Formal analysis. YM: Validation, Formal analysis, Methodology, Data curation, Conceptualization, Software, Visualization, Resources, Writing – review & editing, Investigation. SA: Conceptualization, Writing – review & editing, Supervision, Software, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Visualization, Validation.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. This work was supported by Eagle Talent Project of Chongqing Emergency Medical Center (SYRCCY20230312), Key Project Co-Organized by the Health Commission and the Science & Technology Bureau of Chongqing Province (2024ZDXM024), General Project of Chongqing Province Natural Science Foundation (CSTB2024NSCQ-MSX0873), Chongqing Key Laboratory of Emergency Medicine (2023-KFKT-03 and 2023-KFKT-05), Science and Technology Bureau of Deyang (2023SZZ016), and a grant from Guizhou Health Commission Science Foundation (Grant No. gzwkj2023-103).

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Editage (www.editage.cn) for English language editing. The authors also thank Biorender (www.biorender.com) for the drawing.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The authors declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fmed.2025.1654429/full#supplementary-material

Footnotes

References

1.

Kortelainen S Curtze S Martinez-Majander N Raj R Skrifvars MB . Acute ischemic stroke in a university hospital intensive care unit: 1-year costs and outcome. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. (2022) 66:516–25. doi: 10.1111/aas.14037

2.

Koenig MA . Brain resuscitation and prognosis after cardiac arrest. Crit Care Clin. (2014) 30:765–83. doi: 10.1016/j.ccc.2014.06.007

3.

Hayman EG Patel AP Kimberly WT Sheth KN Simard JM . Cerebral edema after cardiopulmonary resuscitation: a therapeutic target following cardiac arrest?Neurocrit Care. (2018) 28:276–87. doi: 10.1007/s12028-017-0474-8

4.

Panchal AR Bartos JA Cabanas JG Cabañas JG Donnino MW Drennan IR et al . Part 3: adult basic and advanced life support: 2020 American Heart Association guidelines for cardiopulmonary resuscitation and emergency cardiovascular care. Circulation. (2020) 142:S366–468. doi: 10.1161/Cir.0000000000000916

5.

Stocchetti N Taccone FS Citerio G Pepe PE Le Roux PD Oddo M et al . Neuroprotection in acute brain injury: an up-to-date review. Crit Care. (2015) 19:186. doi: 10.1186/s13054-015-0887-8

6.

Dell’anna AM Scolletta S Donadello K Taccone FS . Early neuroprotection after cardiac arrest. Curr Opin Crit Care. (2014) 20:250–8. doi: 10.1097/MCC.0000000000000086

7.

Hong SB Yang H Manaenko A Lu J Mei Q Hu Q . Potential of exosomes for the treatment of stroke. Cell Transplant. (2019) 28:662–70. doi: 10.1177/0963689718816990

8.

Yin F Guo L Meng CY Liu YJ Lu RF Li P et al . Transplantation of mesenchymal stem cells exerts anti-apoptotic effects in adult rats after spinal cord ischemia-reperfusion injury. Brain Res. (2014) 1561:1–10. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2014.02.047

9.

Zhang T Yang X Liu T Hao J Fu N Yan A et al . Adjudin-preconditioned neural stem cells enhance neuroprotection after ischemia reperfusion in mice. Stem Cell Res Ther. (2017) 8:248. doi: 10.1186/s13287-017-0677-0

10.

Mahmood A Lu DY Chopp M . Intravenous administration of marrow stromal cells (MSCs) increases the expression of growth factors in rat brain after traumatic brain injury. J Neurotrauma. (2004) 21:33–9. doi: 10.1089/089771504772695922

11.

McDonald CA Djuliannisaa Z Petraki M Paton MC Penny TR Sutherland AE et al . Intranasal delivery of mesenchymal stromal cells protects against neonatal hypoxic-ischemic brain injury. Int J Mol Sci. (2019) 20:2449. doi: 10.3390/ijms20102449

12.

Morioka C Komaki M Taki A Honda I Yokoyama N Iwasaki K et al . Neuroprotective effects of human umbilical cord-derived mesenchymal stem cells on periventricular leukomalacia-like brain injury in neonatal rats. Inflamm Regen. (2017) 37:1. doi: 10.1186/s41232-016-0032-3

13.

Zhou C Zhou F He Y Liu Y Cao Y . Exosomes in cerebral ischemia-reperfusion injury: current perspectives and future challenges. Brain Sci. (2022) 12:1657. doi: 10.3390/brainsci12121657

14.

Qiu G Zheng G Ge M Wang J Huang R Shu Q et al . Functional proteins of mesenchymal stem cell-derived extracellular vesicles. Stem Cell Res Ther. (2019) 10:359. doi: 10.1186/s13287-019-1484-6

15.

Shah R Patel T Freedman JE . Circulating extracellular vesicles in human disease. N Engl J Med. (2018) 379:958–66. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1704286

16.

Wang J Liu H Chen S Zhang W Chen Y Yang Y . Moderate exercise has beneficial effects on mouse ischemic stroke by enhancing the functions of circulating endothelial progenitor cell-derived exosomes. Exp Neurol. (2020) 330:113325. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2020.113325

17.

Cui LX Saeed Y Li HM Yang JL . Regenerative medicine and traumatic brain injury: from stem cell to cell-free therapeutic strategies. Regen Med. (2022) 17:37–53. doi: 10.2217/rme-2021-0069

18.

Zhang Y Liu J Su M Wang X Xie C . Exosomal microRNA-22-3p alleviates cerebral ischemic injury by modulating KDM6B/BMP2/BMF axis. Stem Cell Res Ther. (2021) 12:111. doi: 10.1186/s13287-020-02091-x

19.

Lv H Li J Che Y . MiR-31 from adipose stem cell-derived extracellular vesicles promotes recovery of neurological function after ischemic stroke by inhibiting TRAF6 and IRF5. Exp Neurol. (2021) 342:113611. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2021.113611

20.

Deng Y Chen D Gao F Lv H Zhang G Sun X et al . Exosomes derived from microRNA-138-5p-overexpressing bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells confer neuroprotection to astrocytes following ischemic stroke via inhibition of LCN2. J Biol Eng. (2019) 13:71. doi: 10.1186/s13036-019-0193-0

21.

Wang C Borger V Sardari M Murke F Skuljec J Pul R et al . Mesenchymal stromal cell-derived small extracellular vesicles induce ischemic neuroprotection by modulating leukocytes and specifically neutrophils. Stroke. (2020) 51:1825–34. doi: 10.1161/strokeaha.119.028012

22.

Pan Q Kuang X Cai S Wang X Du D Wang J et al . MiR-132-3p priming enhances the effects of mesenchymal stromal cell-derived exosomes on ameliorating brain ischemic injury. Stem Cell Res Ther. (2020) 11:260. doi: 10.1186/s13287-020-01761-0

23.

Zhao Y Gan Y Xu G Yin G Liu D . MSCs-derived exosomes attenuate acute brain injury and inhibit microglial inflammation by reversing CysLT2R-ERK1/2 mediated microglia M1 polarization. Neurochem Res. (2020) 45:1180–90. doi: 10.1007/s11064-020-02998-0

24.

Feng B Meng L Luan L Fang Z Zhao P Zhao G . Upregulation of extracellular vesicles-encapsulated miR-132 released from mesenchymal stem cells attenuates ischemic neuronal injury by inhibiting Smad2/c-jun pathway via Acvr2b suppression. Front Cell Dev Biol. (2020) 8:568304. doi: 10.3389/fcell.2020.568304

25.

Guo L Huang Z Huang L Liang J Wang P Zhao L et al . Surface-modified engineered exosomes attenuated cerebral ischemia/reperfusion injury by targeting the delivery of quercetin towards impaired neurons. J Nanobiotechnology. (2021) 19:141. doi: 10.1186/s12951-021-00879-4

26.

Zhao Y Gan Y Xu G Hua K Liu D . Exosomes from MSCs overexpressing microRNA-223-3p attenuate cerebral ischemia through inhibiting microglial M1 polarization mediated inflammation. Life Sci. (2020) 260:118403. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2020.118403

27.

Han M Cao Y Xue H Chu X Li T Xin D et al . Neuroprotective effect of mesenchymal stromal cell-derived extracellular vesicles against cerebral ischemia-reperfusion-induced neural functional injury: a pivotal role for AMPK and JAK2/STAT3/NF-κB signaling pathway modulation. Drug Des Devel Ther. (2020) 14:2865–76. doi: 10.2147/dddt.S248892

28.

Li X Zhang Y Wang Y Zhao D Sun C Zhou S et al . Exosomes derived from CXCR4-overexpressing BMSC promoted activation of microvascular endothelial cells in cerebral ischemia/reperfusion injury. Neural Plast. (2020) 2020:8814239. doi: 10.1155/2020/8814239

29.

Pathipati P Lecuyer M Faustino J Strivelli J Phinney DG Vexler ZS . Mesenchymal stem cell (MSC)-derived extracellular vesicles protect from neonatal stroke by interacting with microglial cells. Neurotherapeutics. (2021) 18:1939–52. doi: 10.1007/s13311-021-01076-9

30.

Zeng Q Zhou Y Liang D He H Liu X Zhu R et al . Exosomes secreted from bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells attenuate oxygen-glucose deprivation/reoxygenation-induced pyroptosis in PC12 cells by promoting AMPK-dependent autophagic flux. Front Cell Neurosci. (2020) 14:182. doi: 10.3389/fncel.2020.00182

31.

Lee ACC Kozuki N Blencowe H Vos T Bahalim A Darmstadt GL et al . Intrapartum-related neonatal encephalopathy incidence and impairment at regional and global levels for 2010 with trends from 1990. Pediatr Res. (2013) 74:50–72. doi: 10.1038/pr.2013.206

32.

Huang X Ding J Li Y Liu W Ji J Wang H et al . Exosomes derived from PEDF modified adipose-derived mesenchymal stem cells ameliorate cerebral ischemia-reperfusion injury by regulation of autophagy and apoptosis. Exp Cell Res. (2018) 371:269–77. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2018.08.021

33.

Mahdavipour M Hassanzadeh G Seifali E Mortezaee K Aligholi H Shekari F et al . Effects of neural stem cell-derived extracellular vesicles on neuronal protection and functional recovery in the rat model of middle cerebral artery occlusion. Cell Biochem Funct. (2020) 38:373–83. doi: 10.1002/cbf.3484.34

34.

Tian T Cao L He C Ye Q Liang R You W et al . Targeted delivery of neural progenitor cell-derived extracellular vesicles for anti-inflammation after cerebral ischemia. Theranostics. (2021) 11:6507–21. doi: 10.7150/thno.56367

35.

Zhang Y Chopp M Meng Y Katakowski M Xin H Mahmood A et al . Effect of exosomes derived from multipluripotent mesenchymal stromal cells on functional recovery and neurovascular plasticity in rats after traumatic brain injury. J Neurosurg. (2015) 122:856–67. doi: 10.3171/2014.11.JNS14770

36.

Zhuang Z Liu M Luo J Zhang X Dai Z Zhang B et al . Exosomes derived from bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells attenuate neurological damage in traumatic brain injury by alleviating glutamate-mediated excitotoxicity. Exp Neurol. (2022) 357:114182. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2022.114182

37.

Wen L Wang YD Shen DF Zheng PD Tu MD You WD et al . Exosomes derived from bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells inhibit neuroinflammation after traumatic brain injury. Neural Regen Res. (2022) 17:2717–24. doi: 10.4103/1673-5374.339489

38.

Xiong L Sun L Zhang Y Peng J Yan J Liu X . Exosomes from bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells can alleviate early brain injury after subarachnoid hemorrhage through miRNA129-5p-HMGB1 pathway. Stem Cells Dev. (2020) 29:212–21. doi: 10.1089/scd.2019.0206

39.

Gao X Xiong Y Li Q Han M Shan D Yang G et al . Extracellular vesicle-mediated transfer of miR-21-5p from mesenchymal stromal cells to neurons alleviates early brain injury to improve cognitive function via the PTEN/Akt pathway after subarachnoid hemorrhage. Cell Death Dis. (2020) 11:363. doi: 10.1038/s41419-020-2530-0

40.

Williams AM Dennahy IS Bhatti UF Halaweish I Xiong Y Chang P et al . Mesenchymal stem cell-derived exosomes provide neuroprotection and improve long-term neurologic outcomes in a swine model of traumatic brain injury and hemorrhagic shock. J Neurotrauma. (2019) 36:54–60. doi: 10.1089/neu.2018.5711

41.

Zhang Y Zhang Y Chopp M Zhang ZG Mahmood A Xiong Y . Mesenchymal stem cell-derived exosomes improve functional recovery in rats after traumatic brain injury: a dose-response and therapeutic window study. Neurorehabil Neural Repair. (2020) 34:616–26. doi: 10.1177/1545968320926164

42.

Zhang Y Zhang Y Chopp M Pang H Zhang ZG Mahmood A et al . MiR-17-92 cluster-enriched exosomes derived from human bone marrow mesenchymal stromal cells improve tissue and functional recovery in rats after traumatic brain injury. J Neurotrauma. (2021) 38:1535–50. doi: 10.1089/neu.2020.7575

43.

Xu H Jia Z Ma K Zhang J Dai C Yao Z et al . Protective effect of BMSCs-derived exosomes mediated by BDNF on TBI via miR-216a-5p. Med Sci Monit. (2020) 26:e920855. doi: 10.12659/msm.920855

44.

Chen Y Li J Ma B Li N Wang S Sun Z et al . MSC-derived exosomes promote recovery from traumatic brain injury via microglia/macrophages in rat. Aging. (2020) 12:18274–96. doi: 10.18632/aging.103692

45.

Han J Yang S Hao X Zhang B Zhang H Xin C et al . Extracellular vesicle-derived microRNA-410 from mesenchymal stem cells protects against neonatal hypoxia-ischemia brain damage through an HDAC1-dependent EGR2/Bcl 2 axis. Front Cell Dev Biol. (2020) 8:579236. doi: 10.3389/fcell.2020.579236

46.

Thomi G Surbek D Haesler V Joerger-Messerli M Schoeberlein A . Exosomes derived from umbilical cord mesenchymal stem cells reduce microglia-mediated neuroinflammation in perinatal brain injury. Stem Cell Res Ther. (2019) 10:105. doi: 10.1186/s13287-019-1207-z

47.

Chu X Liu D Li T Ke H Xin D Wang S et al . Hydrogen sulfide-modified extracellular vesicles from mesenchymal stem cells for treatment of hypoxic-ischemic brain injury. J Control Release. (2020) 328:13–27. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2020.08.037

48.

Luo H Huang F Huang Z Huang H Liu C Feng Y et al . MicroRNA-93 packaged in extracellular vesicles from mesenchymal stem cells reduce neonatal hypoxic-ischemic brain injury. Brain Res. (2022) 1794:148042. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2022.148042

49.

Xin D Li T Chu X Ke H Liu D Wang Z . MSCs-extracellular vesicles attenuated neuroinflammation, synapse damage and microglial phagocytosis after hypoxia-ischemia injury by preventing osteopontin expression. Pharmacol Res. (2021) 164:105322. doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2020.105322

50.

Sisa C Kholia S Naylor J Herrera Sanchez MB Bruno S Deregibus MC et al . Mesenchymal stromal cell derived extracellular vesicles reduce hypoxia-ischaemia induced perinatal brain injury. Front Physiol. (2019) 10:282. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2019.00282

51.

Kaminski N Koster C Mouloud Y Börger V Felderhoff-Müser U Bendix I et al . Mesenchymal stromal cell-derived extracellular vesicles reduce neuroinflammation, promote neural cell proliferation and improve oligodendrocyte maturation in neonatal hypoxic-ischemic brain injury. Front Cell Neurosci. (2020) 14:601176. doi: 10.3389/fncel.2020.601176

52.

Shu J Jiang L Wang M Wang R Wang X Gao C et al . Human bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells-derived exosomes protect against nerve injury via regulating immune microenvironment in neonatal hypoxic-ischemic brain damage model. Immunobiology. (2022) 227:152178. doi: 10.1016/j.imbio.2022.152178

53.

Ophelders DR Wolfs TG Jellema RK Zwanenburg A Andriessen P Delhaas T et al . Mesenchymal stromal cell-derived extracellular vesicles protect the fetal brain after hypoxia-ischemia. Stem Cells Transl Med. (2016) 5:754–63. doi: 10.5966/sctm.2015-019

54.

Shi J Jiang X Gao S Zhu Y Liu J Gu T et al . Gene-modified exosomes protect the brain against prolonged deep hypothermic circulatory arrest. Ann Thorac Surg. (2021) 111:576–85. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2020.05.075

55.

Hernando S Igartua M Santos-Vizcaino E Hernandez RM . Extracellular vesicles released by hair follicle and adipose mesenchymal stromal cells induce comparable neuroprotective and anti-inflammatory effects in primary neuronal and microglial cultures. Cytotherapy. (2023) 25:1027–32. doi: 10.1016/j.jcyt.2023.04.001

56.

Couch Y Buzas EI Di Vizio D Gho YS Harrison P Hill AF et al . A brief history of nearly EV-erything-the rise and rise of extracellular vesicles. J Extracell Vesicles. (2021) 10:e12144. doi: 10.1002/jev2.12144

57.

Thery C Witwer KW Aikawa E Alcaraz MJ Anderson JD Andriantsitohaina R et al . Minimal information for studies of extracellular vesicles 2018 (MISEV 2018): a position statement of the International Society for Extracellular Vesicles and update of the MISEV2014 guidelines. J Extracell Vesicles. (2018) 7:1535750. doi: 10.1080/20013078.2018.1535750

58.

Gurung S Perocheau D Touramanidou L Baruteau J . The exosome journey: from biogenesis to uptake and intracellular signalling. Cell Commun Signal. (2021) 19:47. doi: 10.1186/s12964-021-00730-1

59.

De Jong OG Kooijmans SAA Murphy DE Jiang L Evers MJ Sluijter JP et al . Drug delivery with extracellular vesicles: from imagination to innovation. Acc Chem Res. (2019) 52:1761–70. doi: 10.1021/acs.accounts.9b00109

60.

Ghoreishy A Khosravi A Ghaemmaghami A . Exosomal microRNA and stroke: a review. J Cell Biochem. (2019) 120:16352–61. doi: 10.1002/jcb.29130

61.

Zagrean AM Hermann DM Opris I Zagrean L Popa-Wagner A . Multicellular crosstalk between exosomes and the neurovascular unit after cerebral ischemia. Therapeutic implications. Front Neurosci. (2018) 12:811. doi: 10.3389/fnins.2018.00811

62.

Holm MM Kaiser J Schwab ME . Extracellular vesicles: multimodal envoys in neural maintenance and repair. Trends Neurosci. (2018) 41:360–72. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2018.03.006

63.

Choi H Choi Y Yim HY Mirzaaghasi A Yoo JK Choi C . Biodistribution of exosomes and engineering strategies for targeted delivery of therapeutic exosomes. Tissue Eng Regen Med. (2021) 18:499–511. doi: 10.1007/s13770-021-00361-0

64.

Betzer O Perets N Ange A Motiei M Sadan T Yadid G et al . In vivo neuroimaging of exosomes using gold nanoparticles. ACS Nano. (2017) 11:10883–93. doi: 10.1021/acsnano.7b04495

65.

Imai T Takahashi Y Nishikawa M Kato K Morishita M Yamashita T et al . Macrophage-dependent clearance of systemically administered B16BL6-derived exosomes from the blood circulation in mice. J Extracell Vesicles. (2015) 4:26238. doi: 10.3402/jev.v4.26238

66.

Zheng Y He RY Wang P Shi YJ Zhao L Liang J . Exosomes from LPS-stimulated macrophages induce neuroprotection and functional improvement after ischemic stroke by modulating microglial polarization. Biomater Sci. (2019) 7:2037–49. doi: 10.1039/c8bm01449

67.

Webb RL Kaiser EE Scoville SL Thompson TA Fatima S Pandya C et al . Human neural stem cell extracellular vesicles improve tissue and functional recovery in the murine thromboembolic stroke model. Transl Stroke Res. (2018) 9:530–9. doi: 10.1007/s12975-017-0599-2

68.

Rana S Yue SJ Stadel D Zoller M . Toward tailored exosomes: the exosomal tetraspanin web contributes to target cell selection. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. (2012) 44:1574–84. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2012.06.018

69.

Matsumoto A Takahashi Y Nishikawa M Sano K Morishita M Charoenviriyakul C et al . Role of phosphatidylserine-derived negative surface charges in the recognition and uptake of intravenously injected B16BL6-derived exosomes by macrophages. J Pharm Sci. (2017) 106:168–75. doi: 10.1016/j.xphs.2016.07.022

70.

Grange C Tapparo M Bruno S Chatterjee D Quesenberry PJ Tetta C et al . Biodistribution of mesenchymal stem cell-derived extracellular vesicles in a model of acute kidney injury monitored by optical imaging. Int J Mol Med. (2014) 33:1055–63. doi: 10.3892/ijmm.2014.1663

71.

Yuan DF Zhao YL Banks WA Ullock KM Haney M Batrakova E et al . Macrophage exosomes as natural nanocarriers for protein delivery to inflamed brain. Biomaterials. (2017) 142:1–12. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2017.07.011

72.

Shi M Kovac A Korff A Cook TJ Ginghina C Bullock KM et al . CNS tau efflux via exosomes is likely increased in Parkinson’s disease but not in Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement. (2016) 12:1125–31. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2016.04.00

73.

Shi M Liu CQ Cook TJ Bullock KM Zhao Y Ginghina C et al . Plasma exosomal alpha-synuclein is likely CNS-derived and increased in Parkinson’s disease. Acta Neuropathol. (2014) 128:639–50. doi: 10.1007/s00401-014-1314-y

74.

Matsumoto J Stewart T Banks WA Zhang J . The transport mechanism of extracellular vesicles at the blood–brain barrier. Curr Pharm Des. (2017) 23:6206–14. doi: 10.2174/1381612823666170913164738

75.

Cecchelli R Berezowski V Lundquist S Culot M Renftel M Dehouck MP et al . Modelling of the blood–brain barrier in drug discovery and development. Nat Rev Drug Discov. (2007) 6:650–61. doi: 10.1038/nrd236

76.

Pardridge WM . Blood–brain barrier delivery for lysosomal storage disorders with IgG-lysosomal enzyme fusion proteins. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. (2022) 184:26238. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2022.114234

77.

Wu D Chen Q Chen X Han F Chen Z Wang Y . The blood–brain barrier: structure, regulation, and drug delivery. Signal Transduct Target Ther. (2023) 8:217. doi: 10.1038/s41392-023-01481-w

78.

Ramos-Zaldivar HM Polakovicova I Salas-Huenuleo E Corvalán AH Kogan MJ Yefi CP et al . Extracellular vesicles through the blood–brain barrier: a review. Fluids Barriers CNS. (2022) 19:60. doi: 10.1186/s12987-022-00359-3

79.

Chen CC Liu LN Ma FX Wong CW Guo XE Chacko JV et al . Elucidation of exosome migration across the blood–brain barrier model in vitro. Cell Mol Bioeng. (2016) 9:509–29. doi: 10.1007/s12195-016-0458-3

80.

Kuroda H Tachikawa M Yagi Y Umetsu M Nurdin A Miyauchi E et al . Cluster of differentiation 46 is the major receptor in human blood–brain barrier endothelial cells for uptake of exosomes derived from brain-metastatic melanoma cells (SK-Mel-28). Mol Pharm. (2019) 16:292–304. doi: 10.1021/acs.molpharmaceut.8b00985

81.

Lackland DT Roccella EJ Deutsch AF Fornage M George MG Howard G et al . Factors influencing the decline in stroke mortality: a statement from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke. (2014) 45:315–53. doi: 10.1161/01.str.0000437068.30550.cf

82.

Gravanis I Tsirka SE . Tissue-type plasminogen activator as a therapeutic target in stroke. Expert Opin Ther Targets. (2008) 12:159–70. doi: 10.1517/14728222.12.2.159

83.

Khatri R Vellipuram AR Maud A Cruz-Flores S Rodriguez GJ . Current endovascular approach to the management of acute ischemic stroke. Curr Cardiol Rep. (2018) 20:46. doi: 10.1007/s11886-018-0989-4

84.

Gu SS Kang XW Wang J Guo XF Sun H Jiang L et al . Effects of extracellular vesicles from mesenchymal stem cells on oxygen-glucose deprivation/reperfusion-induced neuronal injury. World J Emerg Med. (2021) 12:61–7. doi: 10.5847/wjem.j.1920-8642.2021.01.010

85.

Li F Zhang J Chen A Liao R Duan Y Xu Y et al . Combined transplantation of neural stem cells and bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells promotes neuronal cell survival to alleviate brain damage after cardiac arrest via microRNA-133b incorporated in extracellular vesicles. Aging. (2021) 13:262–78. doi: 10.18632/aging.103920

86.

Cheng C Chen X Wang Y et al . MSCs‑derived exosomes attenuate ischemia-reperfusion brain injury and inhibit microglia apoptosis might via exosomal miR-26a-5p mediated suppression of CDK6. Mol Med. (2021) 27:67.

87.

Wang W Ji Z Yuan C Yang Y . Mechanism of human umbilical cord mesenchymal stem cells derived-extracellular vesicle in cerebral ischemia-reperfusion injury. Neurochem Res. (2021) 46:455–67. doi: 10.1007/s11064-020-03179-9

88.

GBD 2016 Traumatic Brain Injury and Spinal Cord Injury Collaborators . Global, regional, and national burden of traumatic brain injury and spinal cord injury, 1990–2016: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016. Lancet Neurol. (2019) 18:56–87. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(18)30415-0

89.

Chauhan NB . Chronic neurodegenerative consequences of traumatic brain injury. Restor Neurol Neurosci. (2014) 32:337–65. doi: 10.3233/RNN-130354

90.

Mot YY Moses EJ Mohd Yusoff N Ling KH Yong YK Tan JJ . Mesenchymal stromal cells-derived exosome and the roles in the treatment of traumatic brain injury. Cell Mol Neurobiol. (2023) 43:469–89. doi: 10.1007/s10571-022-01201-y

91.

Muhammad SA Abbas AY Imam MU Saidu Y Bilbis LS . Efficacy of stem cell secretome in the treatment of traumatic brain injury: a systematic review and meta-analysis of preclinical studies. Mol Neurobiol. (2022) 59:2894–909. doi: 10.1007/s12035-022-02759-w

92.

Pischiutta F Caruso E Cavaleiro H Salgado AJ Loane DJ Zanier ER . Mesenchymal stromal cell secretome for traumatic brain injury: focus on immunomodulatory action. Exp Neurol. (2022) 357:114199. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2022.114199

93.

Williams AM Bhatti UF Brown JF Biesterveld BE Kathawate RG Graham NJ et al . Early single-dose treatment with exosomes provides neuroprotection and improves blood–brain barrier integrity in swine model of traumatic brain injury and hemorrhagic shock. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. (2020) 88:207–18. doi: 10.1097/TA.0000000000002563

94.

Ahn SY Sung DK Kim YE Sung S Chang YS Park WS . Brain-derived neurotropic factor mediates neuroprotection of mesenchymal stem cell-derived extracellular vesicles against severe intraventricular hemorrhage in newborn rats. Stem Cells Transl Med. (2021) 10:374–84. doi: 10.1002/sctm.20-0301

95.

Li Y Yang YY Ren JL Xu F Chen FM Li A . Exosomes secreted by stem cells from human exfoliated deciduous teeth contribute to functional recovery after traumatic brain injury by shifting microglia M1/M2 polarization in rats. Stem Cell Res Ther. (2017) 8:198. doi: 10.1186/s13287-017-0648-5

96.

Novak CM Ozen M Burd I . Perinatal brain injury: mechanisms, prevention, and outcomes. Clin Perinatol. (2018) 45:357–75. doi: 10.1016/j.clp.2018.01.015

97.

Xin DQ Zhao YJ Li TT Ke HF Gai CC Guo XF et al . The delivery of miR-21a-5p by extracellular vesicles induces microglial polarization via the STAT3 pathway following hypoxia-ischemia in neonatal mice. Neural Regen Res. (2022) 17:2238–46. doi: 10.4103/1673-5374.336871

98.

Smith PLP Mottahedin A Svedin P Mohn CJ Hagberg H Ek J et al . Peripheral myeloid cells contribute to brain injury in male neonatal mice. J Neuroinflammation. (2018) 15:301. doi: 10.1186/s12974-018-1344-9

99.

Li YK Dammer EB Zhang-Brotzge X Chen S Duong DM Seyfried NT et al . Osteopontin is a blood biomarker for microglial activation and brain injury in experimental hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy. eNeuro. (2017) 4:ENEURO.0253-16.2016. doi: 10.1523/ENEURO.0253-16.2016

100.

Hu Z Yuan Y Zhang X Lu Y Dong N Jiang X et al . Human umbilical cord mesenchymal stem cell-derived exosomes attenuate oxygen-glucose deprivation/reperfusion-induced microglial pyroptosis by promoting FOXO3a-dependent mitophagy. Oxid Med Cell Longev. (2021) 2021:6219715. doi: 10.1155/2021/6219715

101.

Andersen LW Holmberg MJ Berg KM Donnino MW Granfeldt A . In-hospital cardiac arrest: a review. JAMA. (2019) 321:1200–10. doi: 10.1001/jama.2019.1696

102.

Wiberg S Holmberg MJ Donnino MW Kjaergaard J Hassager C Witten L et al . Age-dependent trends in survival after adult in-hospital cardiac arrest. Resuscitation. (2020) 151:189–96. doi: 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2020.03.008

103.

Hypothermia after Cardiac Arrest Study Group . Mild therapeutic hypothermia to improve the neurologic outcome after cardiac arrest. N Engl J Med. (2002) 346:549–56. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa012689

104.

Ajam K Gold LS Beck SS Damon S Phelps R Rea TD . Reliability of the cerebral performance category to classify neurological status among survivors of ventricular fibrillation arrest: a cohort study. Scand J Trauma Resusc Emerg Med. (2011) 19:38. doi: 10.1186/1757-7241-19-38

105.

Katz A Brosnahan SB Papadopoulos J Parnia S Lam JQ . Pharmacologic neuroprotection in ischemic brain injury after cardiac arrest. Ann N Y Acad Sci. (2022) 1507:49–59. doi: 10.1111/nyas.14613

106.

Empana JP Boulanger CM Tafflet M Renard JM Leroyer AS Varenne O et al . Microparticles and sudden cardiac death due to coronary occlusion. The TIDE (thrombus and inflammation in sudden DEath) study. Eur Heart J Acute Cardiovasc Care. (2015) 4:28–36. doi: 10.1177/2048872614538404

107.

Sinning JM Losch J Walenta K Bohm M Nickenig G Werner N . Circulating CD31+/annexin V+ microparticles correlate with cardiovascular outcomes. Eur Heart J. (2010) 32:2034–41. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehq478

108.

Zarà M Campodonico J Cosentino N Biondi ML Amadio P Milanesi G et al . Plasma exosome profile in ST-elevation myocardial infarction patients with and without out-of-hospital cardiac arrest. Int J Mol Sci. (2021) 22:8065. doi: 10.3390/ijms22158065

109.

Fink K Feldbrugge L Schwarz M Bourgeois N Helbing T Bode C et al . Circulating annexin V positive microparticles in patients after successful cardiopulmonary resuscitation. Crit Care. (2011) 15:R251. doi: 10.1186/cc10512

110.

Jing W Tuxiu X Xiaobing L Guijun J Lulu K Jie J et al . Lnc RNA GAS5/miR-137 is a hypoxia-responsive axis involved in cardiac arrest and cardiopulmonary cerebral resuscitation. Front Immunol. (2021) 12:790750. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2021.790750

111.

Al-Masawa ME Alshawsh MA Ng CY Ng AM Foo JB Vijakumaran U et al . Efficacy and safety of small extracellular vesicle interventions in wound healing and skin regeneration: a systematic review and meta-analysis of animal studies. Theranostics. (2022) 12:6455–508. doi: 10.7150/thno.73436

112.

Tian T Zhang HX He CP Fan S Zhu YL Qi C et al . Surface functionalized exosomes as targeted drug delivery vehicles for cerebral ischemia therapy. Biomaterials. (2024) 150:137–49. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2017.10.012

113.

Abuzan M Surugiu R Wang C Mohamud-Yusuf A Tertel T Catalin B et al . Extracellular vesicles obtained from hypoxic mesenchymal stromal cells induce neurological recovery, anti-inflammation, and brain remodeling after distal middle cerebral artery occlusion in rats. Transl Stroke Res. (2025) 16:817–30. doi: 10.1007/s12975-024-01266-5

114.

Wu W Liu J Yang C Xu Z Huang J Lin J . Astrocyte-derived exosome-transported microRNA-34c is neuroprotective against cerebral ischemia/reperfusion injury via TLR7 and the NF-κB/MAPK pathways. Brain Res Bull. (2020) 163:84–94. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresbull.2020.07.013

115.

Xu L Cao H Xie Y Zhang Y Du M Xu X et al . Exosome-shuttled miR-92b-3p from ischemic preconditioned astrocytes protects neurons against oxygen and glucose deprivation. Brain Res. (2019) 1717:66–73. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2019.04.009

116.

Gregorius J Wang C Stambouli O Hussner T Qi Y Tertel T et al . Small extracellular vesicles obtained from hypoxic mesenchymal stromal cells have unique characteristics that promote cerebral angiogenesis, brain remodeling and neurological recovery after focal cerebral ischemia in mice. Basic Res Cardiol. (2021) 116:40. doi: 10.1007/s00395-021-00881-9

117.

Cone AS Yuan X Sun L Duke LC Vreones MP Carrier AN et al . Mesenchymal stem cell-derived extracellular vesicles ameliorate Alzheimer’s disease-like phenotypes in a preclinical mouse model. Theranostics. (2021) 11:8129–42. doi: 10.7150/thno.62069

118.

Alptekin A Khan MB Parvin M Chowdhury H Kashif S Selina FA et al . Effects of low-intensity pulsed focal ultrasound-mediated delivery of endothelial progenitor-derived exosomes in tMCAo stroke. Front Neurol. (2025) 16:1543133. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2025.1543133

119.

Lotfy A Abo Quella NM Wang H . Mesenchymal stromal/stem cell (MSC)-derived exosomes in clinical trials. Stem Cell Res Ther. (2023) 14:66. doi: 10.1186/s13287-023-03287-7

120.

Yu Y Zhou H Xiong Y Liu J . Exosomal miR-199a-5p derived from endothelial cells attenuates apoptosis and inflammation in neural cells by inhibiting endoplasmic reticulum stress. Brain Res. (2020) 1726:146515. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2019.146515

121.

Munson P Lam YW Dragon J Mac Pherson M Shukla A . Exosomes from asbestos-exposed cells modulate gene expression in mesothelial cells. FASEB J. (2018) 32:4328–42. doi: 10.1096/fj.201701291RR

122.

Zhang X Yuan X Shi H Wu L Qian H Xu W . Exosomes in cancer: small particle, big player. J Hematol Oncol. (2015) 8:83. doi: 10.1186/s13045-015-0181-x

123.

Munson P Shukla A . Potential roles of exosomes in the development and detection of malignant mesothelioma: an update. Int J Mol Sci. (2022) 23:15438. doi: 10.3390/ijms232315438

124.

Bowers EC Hassanin AAI Ramos KS . In vitro models of exosome biology and toxicology: new frontiers in biomedical research. Toxicol In Vitro. (2020) 64:104462. doi: 10.1016/j.tiv.2019.02.016

125.

Takakura Y Hanayama R Akiyoshi K Futaki S Hida K Ichiki T et al . Quality and safety considerations for therapeutic products based on extracellular vesicles. Pharm Res. (2024) 41:1573–94. doi: 10.1007/s11095-024-03757-4

126.

Tzng E Bayardo N Yang PC . Current challenges surrounding exosome treatments. Extracell Vesicle. (2023) 2:100023. doi: 10.1016/j.vesic.2023.100023

127.

Zhang Y Dou Y Liu Y Di M Bian H Sun X et al . Advances in therapeutic applications of extracellular vesicles. Int J Nanomedicine. (2023) 18:3285–307. doi: 10.2147/IJN.S409588

128.

Xia Y Zhang J Liu G Wolfram J . Immunogenicity of extracellular vesicles. Adv Mater. (2024) 36:e2403199. doi: 10.1002/adma.202403199

129.

Fiedler T Rabe M Mundkowski RG Oehmcke-Hecht S Peters K . Adipose-derived mesenchymal stem cells release microvesicles with procoagulant activity. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. (2018) 100:49–53. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2018.05.008

130.

Yang BL Long YY Lei Q Gao F Ren WX Cao YL et al . Lethal pulmonary thromboembolism in mice induced by intravenous human umbilical cord mesenchymal stem cell-derived large extracellular vesicles in a dose- and tissue factor-dependent manner. Acta Pharmacol Sin. (2024) 45:2300–12. doi: 10.1038/s41401-024-01327-3

131.

Wright A Snyder OL He H Christenson LK Fleming S Weiss ML . Procoagulant activity of umbilical cord-derived mesenchymal stromal cells’ extracellular vesicles (MSC-EVs). Int J Mol Sci. (2023) 24:9216. doi: 10.3390/ijms24119216

132.

Fusco C De Rosa G Spatocco I Vitiello E Procaccini C Frigè C et al . Extracellular vesicles as human therapeutics: a scoping review of the literature. J Extracell Vesicles. (2024) 13:e12433. doi: 10.1002/jev2.12433

133.

Xu G Jin J Fu Z Wang G Lei X Xu J et al . Extracellular vesicle-based drug overview: research landscape, quality control and nonclinical evaluation strategies. Signal Transduct Target Ther. (2025) 10:255. doi: 10.1038/s41392-025-02312-w

134.

Maji S Yan IK Parasramka M Mohankumar S Matsuda A Patel T . In vitro toxicology studies of extracellular vesicles. J Appl Toxicol. (2017) 37:310–8. doi: 10.1002/jat.3362

135.

Miceli RT Chen TY Nose Y Tichkule S Brown B Fullard JF et al . Extracellular vesicles, RNA sequencing, and bioinformatic analyses: challenges, solutions, and recommendations. J Extracell Vesicles. (2024) 13:e70005. doi: 10.1002/jev2.70005

136.