Abstract

The primary pathological features of osteoarthritis (OA) involve articular cartilage degradation and structural damage, coupled with osteophyte formation and inflammatory responses. As aging populations expand, the prevalence of knee osteoarthritis has risen substantially, severely compromising patients’ quality of life. Current therapeutic strategies for knee osteoarthritis remain limited in clinical efficacy, creating an urgent need for novel treatments that are both effective and safe. Chinese herbal medicine monomers have demonstrated significant potential in OA management, offering multi-pathway therapeutic effects, multi-target modulation, and favorable safety profiles. However, its underlying mechanisms require further elucidation. Mitophagy, a selective mitochondrial quality control mechanism that eliminates reactive oxygen species-damaged organelles, plays a crucial role in maintaining chondrocyte homeostasis and function. Emerging evidence highlights the regulatory significance of mitophagy in OA progression, presenting novel therapeutic perspectives. This review comprehensively analyzes the molecular mechanisms and physiological roles of the oxidative stress-mitophagy axis in knee osteoarthritis pathogenesis, while summarizing recent advances in herbal monomer-mediated regulation of this pathway. Future research directions are proposed to facilitate the systematic exploration and clinical translation of Chinese herbal medicine in OA therapeutics.

1 Introduction

Osteoarthritis (OA) represents a highly prevalent and etiologically heterogeneous degenerative joint disease, clinically manifested by progressive cartilage erosion, osteophytosis, and low-grade synovitis (1). The recalcitrant pain and substantial disability associated with OA profoundly compromise life quality of patients, while engendering considerable socioeconomic consequences (2). Contemporary management of OA encompasses physical modalities, pharmacological interventions, and surgical approaches, all principally directed toward symptomatic relief and functional preservation. Nevertheless, therapeutic efficacy remains constrained by iatrogenic complications of pharmacotherapy, suboptimal treatment adherence, and inherent perioperative risks (3). This therapeutic impasse underscores the critical need for elucidating OA pathogenesis to facilitate development of mechanism-based targeted therapies.

Monomeric compounds derived from Chinese herbal medicine, which have garnered increasing scientific attention, exhibit multidimensional therapeutic potential in addressing multifactorial pathologies such as osteoarthritis (4, 5). Their natural provenance, rooted in botanical evolution, inherently confers low systemic toxicity and superior biocompatibility, attributes that distinguish them from synthetic pharmaceuticals (6). Through advanced purification protocols, which systematically eliminate impurities and xenobiotic contaminants, these compounds achieve a safety profile that minimizes adverse reactions and mitigates cumulative risks inherent to chronic pharmacotherapy (7). Mechanistically, they operate through poly-pharmacological networks, not only targeting discrete pathological nodes but also orchestrating synergistic effects across divergent signaling pathways, thereby resolving the therapeutic limitations of single-target interventions in complex diseases (8, 9). Culturally, their alignment with principles of traditional Chinese medicine (TCM), which emphasize holistic healing, fosters patient adherence (10), while Chinese agricultural-industrial integration, a system that harmonizes large-scale medicinal cultivation with advanced technology-driven extraction, guarantees resource scalability and ecological sustainability (11). The translational paradigm bridging millennia-old empirical knowledge, as exemplified by antimalarial efficacy of artemisinin, with contemporary molecular dissection tools accelerates drug discovery timelines and delivers precision therapies that reconcile ancestral wisdom with cutting-edge innovation (12). Consequently, prioritizing monomers in osteoarthritis therapeutics, which currently rely on symptom-alleviating agents with iatrogenic risks, could redefine global standards by offering solutions that integrate biosafety, mechanistic versatility, and culturally resonant care. Nevertheless, the exact molecular cascades through which these compounds exert chondroprotective and anti-inflammatory effects remain incompletely mapped, necessitating further investigations.

2 The process and regulatory mechanism of mitophagy

2.1 Mitochondria are the main site of reactive oxygen species generation

The mitochondrial matrix, housing the tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle, establishes a microenvironment characterized by elevated partial oxygen pressure. This oxygen enrichment potentiates Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS) generation by providing abundant substrate for univalent electron transfer to molecular oxygen. Multiple pathological factors, including perturbations inΔψm (mitochondrial membrane potential), compromised electron transport chain (ETC) complex activity, or substrate deficiency, collectively increase electron leakage probability, thereby augmenting ROS formation through aberrant oxygen reduction (13). During oxidative phosphorylation, electrons normally undergo sequential transfer through ETC complexes I-IV before final reduction of oxygen to water. However, an estimated 0.2–2% of electrons deviate from this pathway, undergoing direct single-electron transfer to oxygen at complexes I and III, yielding superoxide anion (O2−) as the primary ROS byproduct (14–16). The inherent redox activity of iron–sulfur (Fe-S) clusters within ETC complexes presents an additional ROS source. These evolutionarily conserved cofactors, while essential for electron shuttling, exhibit thermodynamic instability when exposed to matrix oxygen, spontaneously generating ROS via Fenton-like reactions (17).

2.2 The process of mitophagy

As the principal bioenergetic powerhouses of eukaryotic cells, mitochondria orchestrate adenosine triphosphate (ATP) biogenesis while governing critical physiological pathways whose dysregulation precipitates cellular dysfunction. This indispensable role necessitates stringent quality control mechanisms to maintain mitochondrial homeostasis (18). Mitophagy, a phylogenetically conserved selective autophagic process, serves as the cornerstone of mitochondrial quality surveillance by selectively eliminating dysfunctional organelles. The canonical mitophagic cascade progresses through four mechanistically distinct phases: (i) stimulus-induced mitochondrial depolarization triggering ubiquitin signaling cascades; (ii) LC3-mediated autophagosomal encapsulation forming double-membrane mitophagosomes; (iii) SNARE-dependent lysosomal fusion generating autolysosomes; and (iv) cathepsin-mediated proteolytic degradation enabling metabolic recycling (19).

2.3 ROS serves as the core initiating link of mitophagy

Mitophagy operates through two evolutionarily conserved molecular recognition paradigms: the ubiquitin-mediated degradation pathway and the receptor-dependent direct recognition pathway, each executing distinct yet complementary roles in mitochondrial quality surveillance. The canonical ubiquitin-dependent mechanism orchestrates mitochondrial clearance through sequential activation of the PINK1-Parkin signaling axis. PINK1, a mitochondrial-targeted serine/threonine kinase, exhibits dynamic subcellular localization. In normal mitochondria, due to the normal mitochondrial membrane potential (Δψm), PINK1 is imported into the mitochondrial matrix and degraded by proteases. When mitochondria are damaged (e.g., due to abnormal function of electron transport chain complexes III/IV), the production of ROS increases, which further impairs the integrity of the mitochondrial membrane and leads to a decrease in Δψm. As a result, PINK1 fails to enter the matrix and instead accumulates and becomes activated on the outer mitochondrial membrane (OMM) (20). The activated PINK1 phosphorylates ubiquitin molecules on the OMM, generating “phosphorylated ubiquitin (p-Ub).” This phosphorylation cascade induces the translocation of Parkin, which in turn mediates the polyubiquitination of substrates on the OMM (21). This modification is primarily achieved through K63-linked ubiquitin chains, which act as molecular signals to recruit autophagic adaptor proteins (such as p62/SQSTM1, NBR1, and OPTN) that possess both ubiquitin-binding domains and LC3-interacting regions (LIRs). The finally formed ubiquitin-LC3 scaffold initiates phagophore assembly, ultimately leading to the degradation of dysfunctional mitochondria by autolysosomes (22).

Conversely, the ubiquitin-independent pathway employs a cadre of OMM-resident LIR-containing receptors (BNIP3L/NIX, FUNDC1, BCL2L13) that bypass ubiquitination by directly engaging LC3/GABARAP proteins through their LIR motifs. These molecular sentinels detect mitochondrial stress signals and initiate selective encapsulation through LIR-mediated interactions with nascent autophagosomal membranes (23, 24). Notably, as a key direct driver, ROS can precisely mediate various oxidative modifications of protein cysteine residues, including disulfide bond formation, S-glutathionylation, S-nitrosylation, and S-sulfinylation, which can directly regulate the dynamic changes in protein conformation, thereby achieving “switch-like” precise regulation of the function of target proteins (25, 26). Previous studies have shown that the mitophagy receptor FUNDC1 exhibits significant changes in protein modification activity during its activation process. For instance, in HeLa cells treated with hypoxia (1% O2) or the mitochondrial uncoupler FCCP (which disrupts mitochondrial membrane potential), a marked induction of dephosphorylation at serine 13 (Ser13) of FUNDC1 can be observed (27). However, no studies have clearly reported a direct association between the activation mechanism of mitophagy receptors (such as FUNDC1) and ROS-mediated modifications so far. Therefore, future research should prioritize exploring how ROS-driven oxidative modifications specifically regulate mitophagy receptor activation and their underlying mechanisms, a direction of significant scientific value.

Both pathways ultimately converge on lysosomal degradation via conserved membrane fusion machinery (For example, STX17-SNAP29-VAMP8 complex), yet their divergent initiation mechanisms provide layered protection against mitochondrial dysfunction (28). This dual-pathway architecture ensures robust mitochondrial homeostasis by integrating multiple damage sensors with the core autophagy machinery, thereby maintaining cellular metabolic integrity under varying stress conditions.

2.4 Reverse feedback regulation of mitophagy on ROS

Dysfunctional mitochondria constitute intracellular “hotspots” for ROS generation, wherein these aberrant organelles not only produce excessive ROS autonomously but also inflict damage upon adjacent healthy mitochondria, thereby establishing a self-perpetuating vicious cycle (29). The core mechanistic function of mitophagy resides in its capacity to precisely identify, sequester, and degrade such compromised mitochondria through lysosomal degradation. This elimination of primary ROS sources enables mitophagy to directly and efficiently attenuate global intracellular ROS concentrations (30). Following the removal of damaged mitochondria, cells initiate a mitochondrial biogenesis program which is primarily regulated by PGC-1α, generating functionally intact organelles to maintain mitochondrial homeostasis (31). The resultant robust mitochondrial network demonstrates enhanced electron transport efficiency coupled with diminished electron leakage, a combination that fundamentally suppresses ROS production at its origin (Figure 1).

Figure 1

A brief overview of mitophagy.

3 ROS-mitophagy network in osteoarthritis

Articular cartilage represents a paradigm of metabolically constrained tissue due to its absence of vascular, lymphatic, and neural networks. Under homeostatic physiological conditions, this tissue exhibits minimal proliferative capacity, with cellular survival exclusively dependent upon passive nutrient diffusion (32). To accommodate the distinctive avascular high-load-bearing microenvironment, chondrocytes establish an unconventional metabolic paradigm wherein, even when cultured in vitro under oxygen-replete conditions, approximately 85–90% of their energy derives from anaerobic glycolysis, characterized by lactic acid generation through glucose catabolism, while mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation contributes merely 10–15% (33). Notably, upon completion of their proliferative and differentiation phases during embryonic development, these cells transition into a quiescent state during adulthood. This terminal phenotype manifests as profoundly diminished proliferative activity, alongside an irreversible loss of multipotent differentiation potential (34, 35).

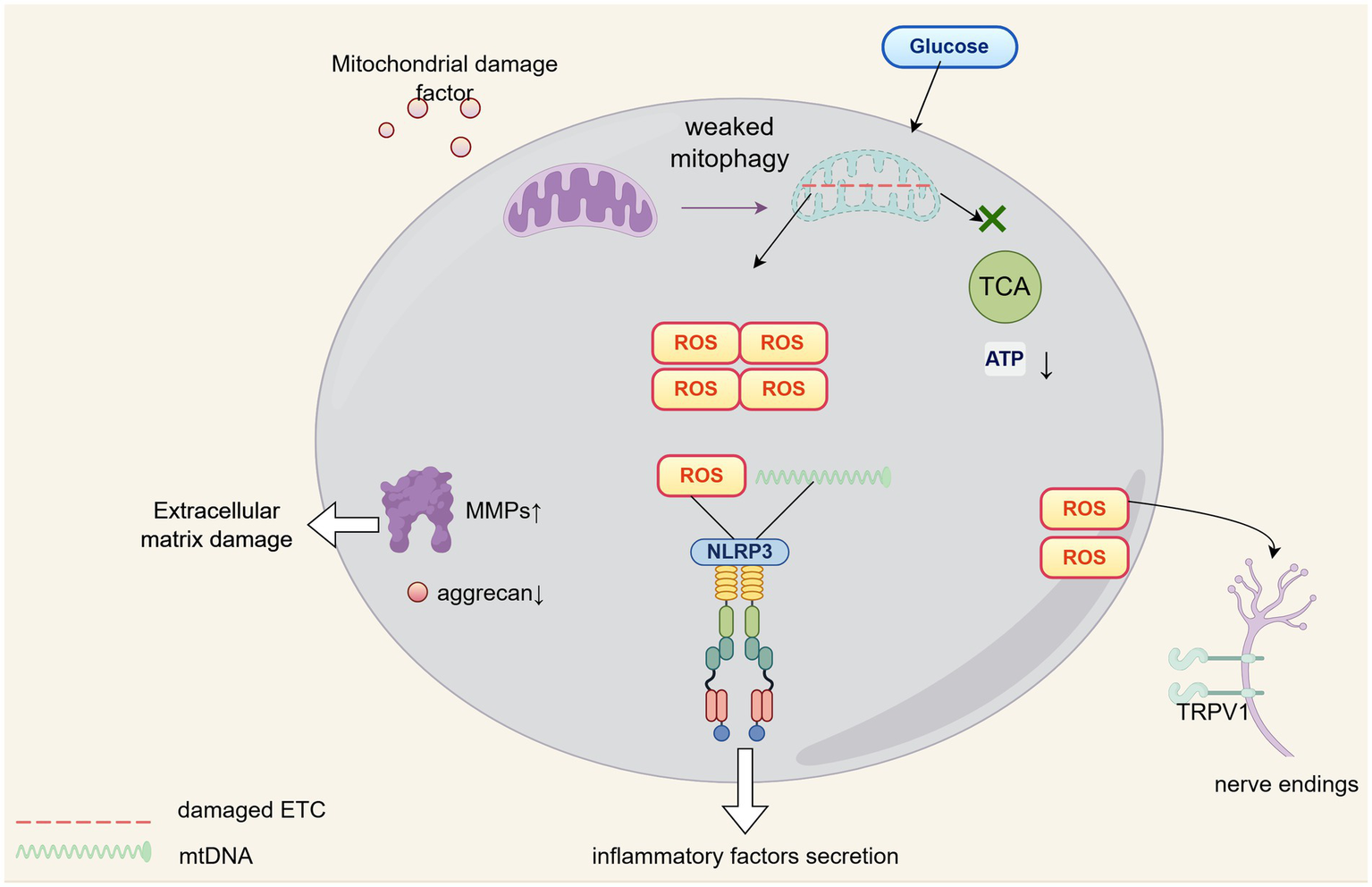

To overcome survival challenges inherent to their biological constraints, chondrocytes must sustain homeostasis through augmented autophagic activity wherein mitophagy constitutes the fundamental mechanism that preserves mitochondrial structural and functional integrity (36). When mitophagy dysfunction arises, damaged organelles accumulate which disrupts cellular energy equilibrium, thereby exacerbating chondrocyte dysfunction and accelerating cartilage degeneration (37). Specifically, such accumulated mitochondrial damage directly suppresses aerobic respiration, substantially diminishing ATP production via a pathway that merely functions as an auxiliary energy source for these cells; this energy deficit becomes particularly critical during high-demand states including injury repair or extracellular matrix synthesis (38). Concurrently, diminished mitophagic flux induces ROS accumulation, which elevates matrix metalloproteinase activity while suppressing type II collagen and aggrecan biosynthesis, a dual perturbation whose remediation through induced mitophagy has been experimentally demonstrated to restore extracellular matrix homeostasis and enhance cartilage biomechanical properties (39, 40). Furthermore, ROS synergizes with mitochondrial DNA released from impaired mitochondria to activate the NLRP3 inflammasome (41), triggering chondrocytes and synovial cells to secrete pro-inflammatory cytokines, such as interleukin-1β, tumor necrosis factor-α, and interleukin-6, thereby establishing an autocrine-paracrine inflammatory network that recruits infiltrating immune cells, polarizes them toward pro-inflammatory phenotypes (42, 43), and amplifies joint cavity inflammation which directly drives cartilage destruction (44). Mitophagy counteracts this cascade by sequestering compromised mitochondria, limiting damage-associated molecular pattern leakage, and restraining inflammasome hyperactivation (45). Simultaneously, elevated ROS upregulate transient receptor potential vanilloid 1 (TRPV1) expression, increasing nociceptive neuron sensitivity that directly contributes to osteoarthritis pain pathogenesis (46), a mechanism corroborated by clinical evidence showing significant positive correlation between synovial fluid reactive oxygen species levels and visual analog scale pain scores (47).

A schematic diagram depicting the molecular network of the ROS-mitophagy axis in the context of OA pathophysiology is shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2

The role of ROS-mitophagy in OA progression.

4 The mechanism of action of monomers of Chinese herbal medicine in targeted regulation of mitophagy for the prevention and treatment of OA

4.1 Inhibiting cellular oxidative stress

Mitochondrial dysfunction and ferroptosis induced by iron overload are key triggers for cartilage damage in OA (48), and a variety of natural compounds exert protective effects by targeting this pathway. Cardamonin, derived from Alpinia katsumadai Hayata, alleviated iron overload-induced mitochondrial dysfunction by restoring membrane potential, reducing ROS and intracellular Fe2+ levels, and preventing ultrastructural damage characterized by mitochondrial cristae fragmentation and outer membrane rupture, whose therapeutic efficacy was further linked to the upregulation of p53 and GPX4 (49). Biochanin A, serves as a pharmacologically active ingredient of Trifolium pratense L., directly targeted Nrf2/system xc−/GPX4 signaling pathway to scavenge ROS and prevent lipid peroxidation (50). Arctiin, from Arctium lappa L., enhanced chondrocyte viability, inhibited chondrocyte apoptosis and ferroptosis, reduced intracellular iron, ROS and lipid ROS levels, repaired mitochondrial damage, and finally alleviated chondrocyte oxidative stress by activating the AKT/NRF2/HO-1 signaling pathway (51). Naringenin, further demonstrated iron-chelating properties, upregulating Nrf2 and HO-1 to counteract iron overload-associated cartilage damage (52). And the chondroprotective efficacy of Ruscogenin arised from two elucidated pharmacological actions, which diminished ROS levels within chondrocytes to suppress ferroptosis, while concurrently targeted sirtuin 3 (SIRT3) to modulate macrophage reprogramming, thereby ameliorating joint inflammatory microenvironments (53).

Loganin, a bioactive compound derived from Cornus officinalis Siebold & Zucc, demonstrated protective efficacy against osteoarthritis through attenuating cartilage degradation and osteophyte formation, thereby delaying disease progression. This effect was mediated via reduction of ROS within chondrocytes, suppression of NLRP3 inflammasome activation, and potentiation of the NRF2/HO-1 signaling axis (54). It is worth noting that in this study, the interaction between Loganin and Nrf2 was confirmed by molecular docking, and immunofluorescence experiments verified that Loganin exerts its antioxidant effect by promoting the nuclear translocation of Nrf2. Ginkgolide C, pharmacologically active ingredient of Ginkgo biloba, inhibited NLRP3 inflammasome activation through modulation of ROS-mediated phospho-IRE1α suppression and Nrf2 pathway induction, which collectively alleviated joint pain in osteoarthritic rats, exert anti-inflammatory actions, impede extracellular matrix catabolism, and confer chondroprotection (55). Comparable pharmacological properties characterized nodakenin, the principal coumarin constituent of Radix Angelicae biseratae, wherein mitochondrial Drp1/ROS/NLRP3 axis regulation improved subchondral bone architecture, mitigates cartilage deterioration, and reduced knee joint inflammation in murine models (56). Cardamonin, isolated from fruits of chasteberry plant, exhibited documented therapeutic potential in knee osteoarthritis according to Li et al., operating through SIRT1 expression upregulation coupled with p38MAPK pathway inhibition that suppressed NLRP3 inflammasome vesicle formation and reversed iron overload-induced chondrocyte apoptosis alongside cartilage degeneration (57). Perillaldehyde, a compound extracted from Perilla frutescens, can alleviate IL-1β-induced mitophagy-associated apoptosis of chondrocytes and NLRP3-mediated inflammatory response by downregulating the expression of ALOX5 and inhibiting the activation of NF-κB signaling pathway, thus exhibiting potential protective effects in OA (58). Collectively, these studies substantiate that naturally occurring phytochemicals alleviate cartilage degradation and decelerate osteoarthritis progression by diminishing ROS burden, blocking NLRP3 inflammasome activation, and concurrently activating antioxidant defense systems exemplified by the Nrf2 pathway or modulating mitochondrial functional cascades such as the Drp1/ROS/NLRP3 axis.

In addition to inducing inflammatory responses and ferroptosis, ROS can further exacerbate mitochondrial damage and amplify mitochondrial dysfunction (59), while natural compounds can regulate this pathway through multiple targets. Apple polyphenols mitigated mitochondrial oxidative stress in OA by enhancing mitochondrial dehydrogenase activity and superoxide dismutase (SOD) bioavailability, which suppressed ROS-mediated inflammatory pathways, thereby attenuating synovitis and cartilage erosion facilitate by MMP-13 (60). Ginsenoside Rb1, isolated from Panax ginseng C., ameliorated oxidative stress through suppression of reactive oxygen species generation while concurrently preserving mitochondrial integrity and exerting articular cartilage protective effects. Within osteoarthritic conditions, this compound reduced reactive oxygen species production in a time-dependent manner, thereby significantly inhibiting prostaglandin E2 and matrix metalloproteinase-3 synthesis (61). Dendrobine, an alkaloid from Dendro bium nobile Lindl., rescued IL-1β-induced mitochondrial dysfunction by normalizing ROS overproduction and enhancing respiratory chain activity (62). Isoorientin, from both Gentiana straminea Maxim. and Fagopyrum esculentum Moench, modulated mitochondrial membrane potential and SOD/MDA ratios by regulating MAPK and PI3K/Akt pathways, offering protection against oxidative stress-driven chondrocyte death (63). Oleanolic acid, an organic acid derived from olea europaea L., attenuated synovial inflammation by elevating SIRT3 expression and inhibiting NF-κB nuclear translocation. Its pleiotropic actions included ROS neutralization, COX-2/PGE2 suppression, and restoration of mitochondrial bioenergetics (64).

As a core antioxidant defense system, the Nrf2 pathway is a key target for natural compounds to exert OA-protective effects (65). Beyond the aforementioned studies, multiple studies have confirmed that Chinese medicine monomers can target Nrf2 to promote downstream cellular antioxidant enzymes such as HO-1, enhance cellular antioxidant capacity to scavenge excessive ROS in OA, and simultaneously inhibit ROS-mediated inflammatory pathways, reduce chondrocyte apoptosis, and ultimately alleviate the pathological progression of OA. Valencene, a sesquiterpenoid compound extracted from Cyperus rotundus, is widely used in food flavors. Chen et al. revealed that it can scavenge ROS by activating the NRF2/HO-1 pathway, and reduce inflammation and cartilage matrix degeneration by inhibiting the NF-κB and MAPK signaling pathways (66). A subsequent integrated traditional Chinese and Western medicine study pointed out that the combined use of curcumin and catalase can synergistically enhance ROS scavenging capacity and inhibit oxidative stress-induced chondrocyte damage and apoptosis. The mechanism lies in the synergistic effect of curcumin regulating the NRF2/HO-1 pathway to upregulate antioxidant enzymes and catalase degrading hydrogen peroxide (67). In addition, although irisin does not directly rely on the Nrf2 pathway, it can indirectly inhibit inflammation-mediated oxidative stress and insufficient synthesis of chondrocyte extracellular matrix by maintaining mitochondrial biogenesis, dynamics, and autophagic processes. Together with Nrf2 pathway-targeting compounds, it forms a multi-dimensional oxidative stress regulatory network, providing a comprehensive theoretical basis for the treatment of OA with natural products (68).

4.2 Activating the PINK1-PARKIN signaling pathway

Curcumin, a classic traditional Chinese medicine monomer derived from a variety of plants, enhanced mitochondrial functionality in osteoarthritic chondrocytes through targeted mitophagy induction. Treatment with curcumin restores mitochondrial membrane potential, reduces ROS and intracellular Ca2+ overload, and elevates ATP synthesis. Quantitative proteomic analyses confirmed its reliance on the AMPK/PINK1/Parkin axis, with upregulated expression of phosphorylation AMPK PINK1, Parkin, and microtubule-associated protein 1 light chain 3 beta (LC3B). These coordinated actions decelerate OA progression by resolving mitochondrial dysfunction and oxidative stress (69). Protocatechuic aldehyde, a phenolic compound isolated from Salvia miltiorrhiza rhizomes, delayed chondrocyte senescence via PINK1/Parkin pathway potentiation. Notably, it elevated LC3-II/LC3-I ratios and enhanced Parkin/PINK1 colocalization at depolarized mitochondria, driving selective autophagic clearance of damaged organelles. This mechanism not only reinforced mitochondrial turnover but also mitigated age-related chondrocyte dysfunction, positioning it as a novel therapeutic candidate for OA management (70).

Acetyl zingerone is an active derivative found in Zingiber officinale Roscoe. It exhibited biological activities such as anti-inflammatory and antioxidant properties. By directly activating the PINK1/Parkin signaling pathway, it could promote mitophagy, thereby inhibiting chondrocyte pyroptosis and alleviating the progression of osteoarthritis (71). Koumine possessed pharmacological activities such as anti-inflammation and analgesia. By activating PINK1/Parkin-mediated mitophagy, it could inhibit IL-1β-induced chondrocyte inflammation, and ultimately reduced the extracellular matrix degradation in osteoarthritic cartilage (72).

Lentinan, the primary therapeutically active constituent derived from Lentinus edodes, demonstrated capacity to attenuate interleukin-1β-induced extracellular matrix degradation and inflammatory factor secretion in chondrocyte cultures when administered in vitro, while concurrently inhibiting cartilage degeneration in osteoarthritic rat models during in vivo application. The mechanism underlying these protective effects involved enhanced mitophagy promotion and mitochondrial homeostasis maintenance, which operated through mTOR-mediated modulation of the PINK1/Parkin pathway (73). Similarly, ginsenoside Rh1exhibited inhibitory actions against osteoarthritis progression and chondrocyte apoptosis both in vivo and in vitro, which was achieved through AMPK-dependent regulation of PINK1/Parkin-directed mitophagy, thereby preserving chondrocyte integrity across experimental contexts (74).

4.3 Activating non-ubiquitination-dependent mitophagy

Artemisinin, a flavonoid compound isolated from Artemisia annua L., enhanced autophagic capacity in knee osteoarthritis chondrocytes through modulation of the PI3K/Akt/mTOR signaling pathway. Experimental evidence indicated that this phytochemical upregulates expression of autophagy-related protein 5 (ATG5), autophagy effector protein Beclin-1, and microtubule-associated protein LC3, while promoting LC3-II conversion and mitochondrial activation. Consequently, artemisinin significantly ameliorated arthritis symptoms in rodent models (75). Similarly, Baicalin, from Scutellaria baicalensis Georgi, elevated expression of anti-apoptotic protein Bcl-2 while suppressing pro-apoptotic proteins Bax and Caspase-3. Mechanistically, these glucosides enhanced Beclin-1 and LC3II/I expression, reduced p62 accumulation, and restored mitochondrial membrane potential. By reversing interleukin-1β-mediated dysregulation of the PI3K/Akt/mTOR axis, they coordinate autophagy induction with mitochondrial functional preservation, thereby exerting chondroprotective effects (76).

Dihydromyricetin, a natural SIRT3 agonist derived from Ampelopsis grossedentata, rebalanced mitochondrial apoptosis and mitophagy. By activating SIRT3, DHM suppresses mitochondrial apoptosis via downregulation of Bax and upregulation of Bcl-2, effectively attenuating chondrocyte apoptosis (77). Oleanolic acid demonstrated multifaceted therapeutic potential in OA. It inhibited Caspase-3 expression while augmenting autophagosome and autolysosome formation via PI3K/Akt/mTOR pathway suppression. Oleanolic acid significantly reduced PI3K, p62, Akt, and mTOR protein levels and phosphorylation states, concomitant with elevated Beclin-1 and LC3-II/LC3-I ratios. Additionally, Oleanolic acid downregulated pro-inflammatory mediators (iNOS, COX-2) and matrix-degrading enzymes (MMP-3, MMP-13), ameliorating both inflammatory cascades and extracellular matrix catabolism (78).

At present, there are no relevant reports indicating that Chinese herbal monomers can initiate mitophagy through mitophagy receptors such as FUNDC1 or BNIP3L. Notably, in prior research on herbal compound formulas, Yang et al. first characterized the composition of a specific formula, then employed transcriptomic analyses to demonstrate that Gubi Zhitong Formula (GBZTF) attenuated OA progression by activating mitophagy pathways. Subsequent cellular experiments further confirmed that GBZTF induced mitophagy via BNIP3L regulation (79). Consequently, this study suggests that future investigations, while continuing to focus on the PINK1-Parkin pathway, should prioritize elucidating the role of ubiquitin-independent mitophagy in mediating the therapeutic effects of Chinese herbal monomers on OA.

A summary of the mechanisms by which Chinese herbal medicine monomers targeted regulation of mitophagy prevented OA was shown in Table 1.

Table 1

| Monomers | Origin | Model | Mitophagy-relative mechanism | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cardamonin | Alpinia katsumadai Hayata | Primary chondrocytes from rats and rat OA model built by anterior cruciate ligament transaction | Reducing ROS and intracellular Fe2+ levels by upregulating p53 and GPX4 | (49) |

| Biochanin A | Trifolium pratense L. | Surgically-induced OA model mice and chondrocytes | Scavenge ROS and prevent lipid peroxidation by Nrf2/system xc−/GPX4 | (50) |

| Arctiin | Arctium lappa L. | Rat OA model established by destabilized medial meniscus | Alleviates oxidative stress in chondrocytes via AKT/NRF2/HO-1 signaling pathway | (51) |

| Naringenin | Amacardi-um occidentale L. | Iron dextran and surgery-induced destabilized medial meniscus rats and chondrocytes | upregulated Nrf2 and HO-1 to anti-oxidative stress | (52) |

| Ruscogenin | Ophiopogon japonicus (L.f.) Ker Gawl. | Rats with anterior cruciate ligament transection-induced osteoarthritis and SW1353 cells | Regulate macrophage reprogramming by targeting Sirt3 and attenuate the ROS level | (53) |

| Loganin | Cornus officinalis Siebold & Zucc | OA mouse model by performing medial meniscus destabilization surgery | Inhibits the ROS-NLRP3-IL-1β axis by activating the NRF2/HO-1 pathway | (54) |

| Ginkgolide C | Ginkgo biloba | Monosodium Iodoacetate-induced osteoarthritis rat model | Inhibited activation of NLRP3 inflammasome by restraining ROS-mediated p-IRE1α and activating Nrf2/NQO1 | (55) |

| Nodakenin | Radix Angelicae biseratae | OA mice by destabilized medial meniscus and primary chondrocytes | Regulate mitochondrial Drp1/ROS/NLRP3 axis | (56) |

| Cardamonin | Chasteberry plant | Iron overload mouse model and then surgically induced osteoarthritis, primary chondrocytes | Attenuate ROS production and NLRP3 inflammasome activation via the SIRT1/p38MAPK signaling pathway | (57) |

| Perillaldehyde | Perilla frutescens | IL-1β-treated chondrocytes and destabilized medial meniscus induced rats | Inhibit mitophagy-associated apoptosis and NLRP3-mediated inflammation by regulating ALOX5/NF-kB signaling | (58) |

| Apple polyphenols | Malus pumila Mill | Surgically-induced OA model rats and HIG-82 synoviocytes | Suppress oxidative stress by enhanced SOD activity | (60) |

| Quercetin | Various plants | LPS treated C28/I2 cell and partial medial meniscectomy-treated Wistar rats | Reduced MDA levels, and activated the Keap1/Nrf2 signaling axis | (61) |

| Ginsenoside Rb1 | Panax ginseng C. A. Mey. | Rabbit osteoarthritis induced by hollow trephine on the femur trochlea | Reduced intracellular ROS through down-regulation of p-Akt, p-P38, and p-P65 | (62) |

| Dendrobine | Dendro bium nobile Lindl. | OA rats model constructed by the transection of anterior cruciate ligament and primary chondrocytes from rats | Improved mitochondrial function and reduced intracellular ROS via NF-κB | (63) |

| Isoorientin | Gentiana straminea Maxim. and Fagopyrum esculentum Moench | H2O2 induced chondrocytes | Modulate mitochondrial membrane potential and SOD/MDA ratios by regulating MAPK and PI3K/Akt pathways | (64) |

| Oleanolic acid | Olea europaea L. | Fibroblast-like synoviocytes | Included ROS neutralization via the SIRT3-NF-κB axis | (65) |

| Valencene | Cyperus rotundus L. | IL-1β induced primary chondrocytes and mouse model constructed by destabilization of medial meniscus | Reverse the rise of ROS by NRF2/HO-1/NQO1 pathway and downstream phosphorylation of NFκB P65 | (67) |

| Curcumin | Various plants | Anterior cruciate ligament transection of the right knee for rats and primary chondrocytes | Regulate the NRF2/HO-1 pathway to scaveng ROS | (68) |

| Curcumin | Various plants | Sodium monoiodoacetate-induced rat OA model and IL-1β induced OA chondrocyte | Maintained mitochondrial homeostasis and promoted PINK1/Parkin expression | (70) |

| Protocatechuic aldehyde | Salvia miltiorrhiza rhizomes | Medial meniscus -induced mice OA model and LPS induced chondrocyte | Facilitated mitochondrial autophagy by PINK1/Parkin pathway | (71) |

| Acetyl zingerone | Zingiber officinale Roscoe | Medial meniscus destabilization mice and LPS plus ATP induced ATDC5 | Activated the PINK1/Parkin | (72) |

| Koumine | Gelsemium elegans (Gardn. & Champ.) Benth. | IL-1β induced RCCS-1 and rat OA model established by intra-articular injection of 2% papain | Activated PINK1/Parkin-mediated mitophagy and promoted LC3II/I | (73) |

| Lentinan | Lentinus edodes | IL-1β induced chondrocytes and rat OA model with anterior cruciate ligament transection | Activate mitophagy via mTOR/PINK1/Parkin pathway | (74) |

| Ginsenoside Rh1 | Panax ginseng C. A. Mey. | IL-1β induced chondrocytes and rat OA model with anterior cruciate ligament transection | Attenuates chondrocyte senescence via AMPK/PINK1/Parkin-mediated mitophagy | (75) |

| Artemisinin | Artemisia annua L. | IL-1β stimulated chondrocytes and destabilized medial meniscus rats | Promoted the conversion of LC3-II and the activation of mitochondria by PI3K/AKT/mTOR signaling | (76) |

| Baicalin | Scutellaria baicalensis Georgi | IL-1β stimulated chondrocytes | Enhanced Beclin-1 and LC3II/I expression, reduce p62 accumulation, and upregulated Pink1 | (77) |

| Dihydromyricetin | Ampelopsis grossedentata | Chondrocytes and post-traumatic OA model | Recouped endogenous mtApoptosis and mitophagy balance by SIRT3 | (78) |

| Oleanolic acid | Olea europaea L. | Rat OA model established by intra-articular injection of monosodium iodoacetate and IL-1β induced ATDC5 cell | Inhibited the PI3K/AKT/mTOR signaling pathway and elevated LC3-II/LC3-I ratios | (79) |

Mechanism of action of Chinese herbal medicine monomers in treating osteoarthritis via targeted regulation of mitophagy.

5 Limitations of the current research

Although there are currently many studies on Chinese herbal medicine treating osteoarthritis by improving mitophagy, most of the current research focuses on basic experiments, and there is a lack of high-quality and high-level clinical studies. At the same time, the current research lacks the verification of the direct interaction between the monomers of Chinese herbal medicine and target molecules (such as Parkin/PINK1, Bcl-2). Most of the studies mainly focus on regulating a single mitochondrial-related pathway, and the detection indicators are limited. However, various mitochondrial-related pathways and targets may affect the development and outcome of osteoarthritis through interactions, and it is also worthy of in-depth investigation whether the changes in mitochondria are related to the alterations in mechanisms such as histones and the endoplasmic reticulum. Finally, as the center of energy metabolism, mitochondrial dysfunction can lead to changes in metabolic activity and the production of metabolic by-products such as lactic acid, and lactic acid can serve as a substrate for lactylation modification to participate in protein modification (80). Therefore, subsequent research can further focus on the roles of mitophagy and lactylation modification in osteoarthritis and the protective mechanisms of Chinese herbal medicine against these processes.

6 Summary and prospects

In recent years, mounting evidence has substantiated the pivotal role of bioactive monomers derived from Chinese herbal medicine in mitigating osteoarthritis through modulation of the ROS-mitophagy axis. These phytochemicals effectively attenuate oxidative stress by suppressing NADPH oxidase activity and activating the Nrf2-mediated antioxidant pathway, while concurrently orchestrating mitophagy-related signaling cascades to facilitate the selective removal of dysfunctional mitochondria, thereby preserving chondrocyte homeostasis and decelerating OA progression. Unlike conventional antioxidants, TCM monomers possess distinctive advantages, including multi-target regulatory capacity, favorable biosafety profiles, and natural origins. However, their precise molecular mechanisms, dose–response relationships, and discrepancies between in vitro and in vivo findings warrant further elucidation.

Future investigations should prioritize the following directions: (1) Target identification represented by activity-based protein profiling (81), limited proteolysis-coupled mass spectrometry (82) to delineate the interactions between TCM monomers and ROS/mitophagy-associated proteins; (2) Real-time spatiotemporal monitoring, for example live-cell imaging coupled with ROS/autophagosome biosensors, to dynamically track intracellular redox and mitophagic flux; (3) Clinical translation strategies (e.g., synergistic therapy with metformin, quantification of synovial fluid mtDNA as a mitophagy biomarker) and (4) Advanced drug delivery optimization, take hyaluronic acid-functionalized nanocarriers as an example to enhance joint-specific biodistribution.

Recent years have witnessed growing academic interest in plant-derived exosome-like nanoparticles (PELNs) as an innovative dosage form for traditional Chinese medicine. These nanovesicles exhibit significant advantages including broad source availability, low immunogenicity, and high accessibility. Substantial evidence demonstrates that PELNs possess multifaceted pharmacological properties encompassing anti-inflammatory, anti-tumor, and immunomodulatory activities, which render them therapeutically valuable against malignancies, inflammatory disorders, and bacterial infections (83, 84). A pioneering study concerning osteoarthritis therapy recently engineered a supramolecular network hydrogel by integrating rhein, a bioactive TCM monomer, with Spirulina platensis-derived exosomes. This composite system (designated Rh Gel@SP-EVs) concurrently delivers anti-inflammatory effects and metabolic support. Mechanistically, it attenuates pathological processes through selective inhibition of the JAK/STAT signaling pathway, thereby significantly suppressing aberrant reactive oxygen species generation and mitochondrial dysfunction within inflamed chondrocytes (85). Future investigations should prioritize three strategic directions: diversifying PELN sources and therapeutic applications, systematically screening anti-osteoarthritic PELNs from additional medicinal plants, and conducting comparative analyses of bioactive constituents and synergistic mechanisms across varied PELN types.

Moreover, artificial intelligence (AI)-assisted mining of TCM monomer libraries and their crosstalk with the ROS-mitophagy network, complemented by mechanistic reinterpretation of TCM theories through contemporary biomedical paradigms, will unveil novel therapeutic avenues for OA. Such interdisciplinary integration is poised to catalyze innovation in OA pharmacotherapy and foster convergence between traditional and modern medicine.

Statements

Author contributions

RL: Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. CZ: Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The authors declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1.

Abramoff B Caldera FE . Osteoarthritis: pathology, diagnosis, and treatment options. Med Clin North Am. (2020) 104:293–311. doi: 10.1016/j.mcna.2019.10.007

2.

Yan H Guo J Zhou W Dong C Liu J . Health-related quality of life in osteoarthritis patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychol Health Med. (2022) 27:1859–74. doi: 10.1080/13548506.2021.1971725

3.

Perruccio AV Young JJ Wilfong JM Denise Power J Canizares M Badley EM . Osteoarthritis year in review 2023: epidemiology & therapy. Osteoarthr Cartil. (2024) 32:159–65. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2023.11.012

4.

Miao K Liu W Xu J Qian Z Zhang Q . Harnessing the power of traditional Chinese medicine monomers and compound prescriptions to boost cancer immunotherapy. Front Immunol. (2023) 14:1277243. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2023.1277243

5.

Zhou G Zhang X Gu Z Zhao J Luo M Liu J . Research progress on the treatment of knee osteoarthritis combined with osteoporosis by single-herb Chinese medicine and compound. Front Med (Lausanne). (2023) 10:1254086. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2023.1254086

6.

Yan R Xie B Xie K Liu Q Sui S Wang S et al . Unravelling and reconstructing the biosynthetic pathway of bergenin. Nat Commun. (2024) 15:3539. doi: 10.1038/s41467-024-47502-2

7.

Zhao G Dong H Xue K Lou S Qi R Zhang X et al . Nonheme iron catalyst mimics heme-dependent haloperoxidase for efficient bromination and oxidation. Sci Adv. (2024) 10:eadq0028. doi: 10.1126/sciadv.adq0028

8.

Zhou S Qingman X Zhang W Zhang D Liu S . Quercetin as a multi-target natural therapeutic in aging-related diseases: systemic molecular and cellular mechanisms. Phytother Res. (2025) 39:4821–69. doi: 10.1002/ptr.70078

9.

Zhang X Wang G Kuang W Xu L He Y Zhou L et al . Discovery and evolution of berberine analogues as anti-Helicobacter pylori agents with multi-target mechanisms. Bioorg Chem. (2024) 151:107628. doi: 10.1016/j.bioorg.2024.107628

10.

Mei J Ju C Wang B Gao R Zhang Y Zhou S et al . The efficacy and safety of Bazi Bushen capsule in treating premature aging: a randomized, double blind, multicenter, placebo-controlled clinical trial. Phytomedicine. (2024) 130:155742. doi: 10.1016/j.phymed.2024.155742

11.

Guo X Zhang RR Sun JY Liu Y Yuan XS Chen YY et al . The molecular mechanism of action for the potent antitumor component extracted using supercritical fluid extraction from Croton crassifolius root. J Ethnopharmacol. (2024) 327:117835. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2024.117835

12.

Ma N Zhang Z Liao F Jiang T Tu Y . The birth of artemisinin. Pharmacol Ther. (2020) 216:107658. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2020.107658

13.

Cadenas S . Mitochondrial uncoupling, Ros generation and cardioprotection. Biochim Biophys Acta Bioenerg. (2018) 1859:940–50. doi: 10.1016/j.bbabio.2018.05.019

14.

Kudin AP Bimpong-Buta NY Vielhaber S Elger CE Kunz WS . Characterization of superoxide-producing sites in isolated brain mitochondria. J Biol Chem. (2004) 279:4127–35. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M310341200

15.

Fang J Wong HS Brand MD . Production of superoxide and hydrogen peroxide in the mitochondrial matrix is dominated by site I(Q) of complex I in diverse cell lines. Redox Biol. (2020) 37:101722. doi: 10.1016/j.redox.2020.101722

16.

Murphy MP . How mitochondria produce reactive oxygen species. Biochem J. (2009) 417:1–13. doi: 10.1042/BJ20081386

17.

Halcrow PW Lynch ML Geiger JD Ohm JE . Role of endolysosome function in iron metabolism and brain carcinogenesis. Semin Cancer Biol. (2021) 76:74–85. doi: 10.1016/j.semcancer.2021.06.013

18.

Liu BH Xu CZ Liu Y Lu ZL Fu TL Li GR et al . Mitochondrial quality control in human health and disease. Mil Med Res. (2024) 11:32. doi: 10.1186/s40779-024-00536-5

19.

Lu Y Li Z Zhang S Zhang T Liu Y Zhang L . Cellular mitophagy: mechanism, roles in diseases and small molecule pharmacological regulation. Theranostics. (2023) 13:736–66. doi: 10.7150/thno.79876

20.

Gan ZY Callegari S Cobbold SA Cotton TR Mlodzianoski MJ Schubert AF et al . Activation mechanism of Pink1. Nature. (2022) 602:328–35. doi: 10.1038/s41586-021-04340-2

21.

Kane LA Lazarou M Fogel AI Li Y Yamano K Sarraf SA et al . Pink1 phosphorylates ubiquitin to activate Parkin E3 ubiquitin ligase activity. J Cell Biol. (2014) 205:143–53. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201402104

22.

Sun Y Cao Y Wan H Memetimin A Cao Y Li L et al . A mitophagy sensor Pptc7 controls Bnip3 and nix degradation to regulate mitochondrial mass. Mol Cell. (2024) 84:327–44.e9. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2023.11.038

23.

Chen M Chen Z Wang Y Tan Z Zhu C Li Y et al . Mitophagy receptor Fundc1 regulates mitochondrial dynamics and mitophagy. Autophagy. (2016) 12:689–702. doi: 10.1080/15548627.2016.1151580

24.

Wang J Chen A Xue Z Liu J He Y Liu G et al . Bcl2L13 promotes mitophagy through Dnm1L-mediated mitochondrial fission in glioblastoma. Cell Death Dis. (2023) 14:585. doi: 10.1038/s41419-023-06112-4

25.

Nagarkoti S Dubey M Sadaf S Awasthi D Chandra T Jagavelu K et al . Catalase S-Glutathionylation by Nox2 and mitochondrial-derived Ros adversely affects mice and human neutrophil survival. Inflammation. (2019) 42:2286–96. doi: 10.1007/s10753-019-01093-z

26.

Mu B Zeng Y Luo L Wang K . Oxidative stress-mediated protein sulfenylation in human diseases: past, present, and future. Redox Biol. (2024) 76:103332. doi: 10.1016/j.redox.2024.103332

27.

Chen G Han Z Feng D Chen Y Chen L Wu H et al . A regulatory signaling loop comprising the Pgam5 phosphatase and Ck2 controls receptor-mediated mitophagy. Mol Cell. (2014) 54:362–77. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2014.02.034

28.

Wang L Zhu H Shi Z Chen B Huang H Lin G et al . Mk8722 initiates early-stage autophagy while inhibiting late-stage autophagy via Fasn-dependent reprogramming of lipid metabolism. Theranostics. (2024) 14:75–95. doi: 10.7150/thno.83051

29.

Lebiedzinska-Arciszewska M Suski J Bonora M Pakula B Pinton P Duszynski J et al . The relation between mitochondrial membrane potential and reactive oxygen species formation. Methods Mol Biol (Clifton, NJ). (2025) 2878:133–62. doi: 10.1007/978-1-0716-4264-1_8

30.

Li J Lin Q Shao X Li S Zhu X Wu J et al . Hif1α-Bnip3-mediated mitophagy protects against renal fibrosis by decreasing Ros and inhibiting activation of the Nlrp3 inflammasome. Cell Death Dis. (2023) 14:200. doi: 10.1038/s41419-023-05587-5

31.

Liu L Li Y Wang J Zhang D Wu H Li W et al . Mitophagy receptor Fundc1 is regulated by Pgc-1α/Nrf1 to fine tune mitochondrial homeostasis. EMBO Rep. (2021) 22:e50629. doi: 10.15252/embr.202050629

32.

Bhosale AM Richardson JB . Articular cartilage: structure, injuries and review of management. Br Med Bull. (2008) 87:77–95. doi: 10.1093/bmb/ldn025

33.

Chen Y Wu J Zhang S Gao W Liao Z Zhou T et al . Hnrnpk maintains chondrocytes survival and function during growth plate development via regulating Hif1α-glycolysis axis. Cell Death Dis. (2022) 13:803. doi: 10.1038/s41419-022-05239-0

34.

Chen Y Yu Y Wen Y Chen J Lin J Sheng Z et al . A high-resolution route map reveals distinct stages of chondrocyte dedifferentiation for cartilage regeneration. Bone Res. (2022) 10:38. doi: 10.1038/s41413-022-00209-w

35.

Cohen NP Foster RJ Mow VC . Composition and dynamics of articular cartilage: structure, function, and maintaining healthy state. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. (1998) 28:203–15. doi: 10.2519/jospt.1998.28.4.203

36.

Fang G Wen X Jiang Z du X Liu R Zhang C et al . Fundc1/Pfkp-mediated mitophagy induced by Kd025 ameliorates cartilage degeneration in osteoarthritis. Mol Ther. (2023) 31:3594–612. doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2023.10.016

37.

Hu S Zhang C Ni L Huang C Chen D Shi K et al . Stabilization of Hif-1α alleviates osteoarthritis via enhancing mitophagy. Cell Death Dis. (2020) 11:481. doi: 10.1038/s41419-020-2680-0

38.

Huang LW Huang TC Hu YC Hsieh BS Chiu PR Cheng HL et al . Zinc protects chondrocytes from monosodium iodoacetate-induced damage by enhancing Atp and mitophagy. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. (2020) 521:50–6. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2019.10.066

39.

Lin C Ge L Tang L He Y Moqbel SAA Xu K et al . Nitidine chloride alleviates inflammation and cellular senescence in murine osteoarthritis through scavenging Ros. Front Pharmacol. (2022) 13:919940. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2022.919940

40.

Liu L Zhang W Liu T Tan Y Chen C Zhao J et al . The physiological metabolite α-ketoglutarate ameliorates osteoarthritis by regulating mitophagy and oxidative stress. Redox Biol. (2023) 62:102663. doi: 10.1016/j.redox.2023.102663

41.

Mourmoura E Papathanasiou I Trachana V Konteles V Tsoumpou A Goutas A et al . Leptin-depended Nlrp3 inflammasome activation in osteoarthritic chondrocytes is mediated by Ros. Mech Ageing Dev. (2022) 208:111730. doi: 10.1016/j.mad.2022.111730

42.

Li H Yuan Y Zhang L Xu C Xu H Chen Z . Reprogramming macrophage polarization, depleting ROS by astaxanthin and thioketal-containing polymers delivering rapamycin for osteoarthritis treatment. Adv Sci (Weinh). (2024) 11:e2305363. doi: 10.1002/advs.202305363

43.

Xue C Tian J Cui Z Liu Y Sun D Xiong M et al . Reactive oxygen species (Ros)-mediated M1 macrophage-dependent nanomedicine remodels inflammatory microenvironment for osteoarthritis recession. Bioact Mater. (2024) 33:545–61. doi: 10.1016/j.bioactmat.2023.10.032

44.

Sebastian A Hum NR Mccool JL Wilson SP Murugesh DK Martin KA et al . Single-cell Rna-Seq reveals changes in immune landscape in post-traumatic osteoarthritis. Front Immunol. (2022) 13:938075. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2022.938075

45.

Yang X Han P Li M Xue Y Yu X Jiang M et al . Hiv-1 tat mediates microglial Nlrp3 inflammasome activation and neurotoxicity by inducing cytosolic mtdna stress. Int J Biol Macromol. (2025) 318:145093. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2025.145093

46.

Wang L Luo J Mao Z Zhao W du S Zhang Y et al . Glycine N-acyltransferase deficiency in sensory neurons suppresses osteoarthritis pain. J Pain. (2025) 33:105408. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2025.105408

47.

Srivastava S Saksena AK Khattri S Kumar S Dagur RS . Curcuma longa extract reduces inflammatory and oxidative stress biomarkers in osteoarthritis of knee: a four-month, double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Inflammopharmacology. (2016) 24:377–88. doi: 10.1007/s10787-016-0289-9

48.

Lu S Liu Z Qi M Wang Y Chang L Bai X et al . Ferroptosis and its role in osteoarthritis: mechanisms, biomarkers, and therapeutic perspectives. Front Cell Dev Biol. (2024) 12:1510390. doi: 10.3389/fcell.2024.1510390

49.

Gong Z Wang Y Li L Li X Qiu B Hu Y . Cardamonin alleviates chondrocytes inflammation and cartilage degradation of osteoarthritis by inhibiting ferroptosis via p53 pathway. Food Chem Toxicol. (2023) 174:113644. doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2023.113644

50.

He Q Yang J Pan Z Zhang G Chen B Li S et al . Biochanin a protects against iron overload associated knee osteoarthritis via regulating iron levels and Nrf2/system xc−/Gpx4 axis. Biomed Pharmacother. (2023) 157:113915. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2022.113915

51.

Yang J Chen D He Q Chen B Pan Z Zhang G et al . Arctiin alleviates knee osteoarthritis by suppressing chondrocyte oxidative stress induced by accumulated iron via Akt/Nrf2/ho-1 signaling pathway. Sci Rep. (2024) 14:31935. doi: 10.1038/s41598-024-83383-7

52.

Pan Z He Q Zeng J Li S Li M Chen B et al . Naringenin protects against iron overload-induced osteoarthritis by suppressing oxidative stress. Phytomedicine. (2022) 105:154330. doi: 10.1016/j.phymed.2022.154330

53.

Liu Y Li W Tang H Yang Z Wei M Zhou W et al . Ruscogenin attenuates osteoarthritis by modulating oxidative stress-mediated macrophage reprogramming via directly targeting Sirt3. Int Immunopharmacol. (2024) 143:113336. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2024.113336

54.

Li M Xiao J Chen B Pan Z Wang F Chen W et al . Loganin inhibits the Ros-Nlrp3-Il-1β axis by activating the Nrf2/ho-1 pathway against osteoarthritis. Chin J Nat Med. (2024) 22:977–90. doi: 10.1016/S1875-5364(24)60555-8

55.

Jia L Gong Y Jiang X Fan X Ji Z Ma T et al . Ginkgolide C inhibits Ros-mediated activation of Nlrp3 inflammasome in chondrocytes to ameliorate osteoarthritis. J Ethnopharmacol. (2024) 325:117887. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2024.117887

56.

Yi N Mi Y Xu X Li N Chen B Yan K et al . Nodakenin attenuates cartilage degradation and inflammatory responses in a mice model of knee osteoarthritis by regulating mitochondrial Drp1/Ros/Nlrp3 axis. Int Immunopharmacol. (2022) 113:109349. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2022.109349

57.

Li S He Q Chen B Zeng J Dou X Pan Z et al . Cardamonin protects against iron overload induced arthritis by attenuating Ros production and Nlrp3 inflammasome activation via the Sirt1/p38mapk signaling pathway. Sci Rep. (2023) 13:13744. doi: 10.1038/s41598-023-40930-y

58.

Zhou Q Li X Hou D . Perillaldehyde protect chondrocytes from mitophagy-associated apoptosis and Nlrp3-mediated inflammation by regulating Alox5/Nf-kB signaling in osteoarthritis. Int Immunopharmacol. (2025) 158:114820. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2025.114820

59.

Lin S Wu B Hu X Lu H . Sirtuin 4 (Sirt4) downregulation contributes to chondrocyte senescence and osteoarthritis via mediating mitochondrial dysfunction. Int J Biol Sci. (2024) 20:1256–78. doi: 10.7150/ijbs.85585

60.

Kobayashi M Harada S Fujimoto N Nomura Y . Apple polyphenols exhibits chondroprotective changes of synovium and prevents knee osteoarthritis. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. (2022) 614:120–4. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2022.05.016

61.

Hossain MA Alam MJ Kim B Kang CW Kim JH . Ginsenoside-Rb1 prevents bone cartilage destruction through down-regulation of p-Akt, p-P38, and p-P65 signaling in rabbit. Phytomedicine. (2022) 100:154039. doi: 10.1016/j.phymed.2022.154039

62.

Chen H Tu M Liu S Wen Y Chen L . Dendrobine alleviates cellular senescence and osteoarthritis via the Ros/Nf-κB Axis. Int J Mol Sci. (2023) 24:2365. doi: 10.3390/ijms24032365

63.

Cui T Lan Y Lu Y Yu F Lin S Fu Y et al . Isoorientin ameliorates H(2)O(2)-induced apoptosis and oxidative stress in chondrocytes by regulating Mapk and Pi3K/Akt pathways. Aging (Albany NY). (2023) 15:4861–74. doi: 10.18632/aging.204768

64.

Bao J Yan W Xu K Chen M Chen Z Ran J et al . Oleanolic acid decreases Il-1β-induced activation of fibroblast-like synoviocytes via the Sirt3-Nf-κb axis in osteoarthritis. Oxidative Med Cell Longev. (2020) 2020:7517219. doi: 10.1155/2020/7517219

65.

Saha S Rebouh NY . Anti-osteoarthritis mechanism of the Nrf2 signaling pathway. Biomedicine. (2023) 11:3176. doi: 10.3390/biomedicines11123176

66.

Chen S Meng C He Y Xu H Qu Y Wang Y et al . An in vitro and in vivo study: Valencene protects cartilage and alleviates the progression of osteoarthritis by anti-oxidative stress and anti-inflammatory effects. Int Immunopharmacol. (2023) 123:110726. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2023.110726

67.

Chen B He Q Chen C Lin Y Xiao J Pan Z et al . Combination of curcumin and catalase protects against chondrocyte injury and knee osteoarthritis progression by suppressing oxidative stress. Biomed Pharmacother. (2023) 168:115751. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2023.115751

68.

Wang FS Kuo CW Ko JY Chen YS Wang SY Ke HJ et al . Irisin mitigates oxidative stress, chondrocyte dysfunction and osteoarthritis development through regulating mitochondrial integrity and autophagy. Antioxidants (Basel). (2020) 9:810. doi: 10.3390/antiox9090810

69.

Jin Z Chang B Wei Y Yang Y Zhang H Liu J et al . Curcumin exerts chondroprotective effects against osteoarthritis by promoting Ampk/Pink1/Parkin-mediated mitophagy. Biomed Pharmacother. (2022) 151:113092. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2022.113092

70.

Jie L Shi X Kang J Fu H Yu L Tian D et al . Protocatechuic aldehyde attenuates chondrocyte senescence via the regulation of Pten-induced kinase 1/Parkin-mediated mitochondrial autophagy. Int J Immunopathol Pharmacol. (2024) 38:3946320241271724. doi: 10.1177/03946320241271724

71.

Zhang Z Huang T Chen X Chen J Yuan H Yi N et al . Acetyl zingerone inhibits chondrocyte pyroptosis and alleviates osteoarthritis progression by promoting mitophagy through the Pink1/parkin signaling pathway. Int Immunopharmacol. (2025) 161:115055. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2025.115055

72.

Kong X Ning C Liang Z Yang C Wu Y Li Y et al . Koumine inhibits Il-1β-induced chondrocyte inflammation and ameliorates extracellular matrix degradation in osteoarthritic cartilage through activation of Pink1/Parkin-mediated mitochondrial autophagy. Biomed Pharmacother. (2024) 173:116273. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2024.116273

73.

Li Q Gu H Song K Kong X Li Y Liu Z et al . Lentinan rewrites extracellular matrix homeostasis by activating mitophagy via mtor/Pink1/Parkin pathway in cartilage to alleviating osteoarthritis. Int J Biol Macromol. (2025) 322:146900. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2025.146900

74.

Chen H Zhao D Liu S Zhong Y Wen Y Chen L . Ginsenoside Rh1 attenuates chondrocyte senescence and osteoarthritis via Ampk/Pink1/Parkin-mediated mitophagy. Int Immunopharmacol. (2025) 159:114911. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2025.114911

75.

Li J Jiang M Yu Z Xiong C Pan J Cai Z et al . Artemisinin relieves osteoarthritis by activating mitochondrial autophagy through reducing Tnfsf11 expression and inhibiting Pi3K/Akt/mtor signaling in cartilage. Cell Mol Biol Lett. (2022) 27:62. doi: 10.1186/s11658-022-00365-1

76.

He J He J . Baicalin mitigated Il-1β-induced osteoarthritis chondrocytes damage through activating mitophagy. Chem Biol Drug Des. (2023) 101:1322–34. doi: 10.1111/cbdd.14215

77.

Xia X Liu Y Lu Y Liu J Deng Y Wu Y et al . Retuning mitochondrial apoptosis/Mitophagy balance via Sirt3-energized and microenvironment-modulated hydrogel microspheres to impede osteoarthritis. Adv Healthc Mater. (2023) 12:e2302475. doi: 10.1002/adhm.202302475

78.

Yu Y Ma T Lv L Jia L Ruan H Chen H et al . Oleanolic acid targets the regulation of Pi3K/Akt/mTOR pathway and activates autophagy in chondrocytes to improve osteoarthritis in rats. J Funct Foods. (2022) 94:105144. doi: 10.1016/j.jff.2022.105144

79.

Yang J Zhou Z Ding X He R Li A Wei Y et al . Gubi Zhitong formula alleviates osteoarthritis in vitro and in vivo via regulating Bnip3L-mediated mitophagy. Phytomedicine. (2024) 128:155279. doi: 10.1016/j.phymed.2023.155279

80.

Dong F Yin H Zheng Z . Hypoxia-inducible factor-1α regulates Bnip3-dependent Mitophagy and mediates metabolic reprogramming through histone lysine Lactylation modification to affect glioma proliferation and invasion. J Biochem Mol Toxicol. (2025) 39:e70069. doi: 10.1002/jbt.70069

81.

Luo P Zhang Q Zhong TY Chen JY Zhang JZ Tian Y et al . Celastrol mitigates inflammation in sepsis by inhibiting the Pkm2-dependent Warburg effect. Mil Med Res. (2022) 9:22. doi: 10.1186/s40779-022-00381-4

82.

Peng YC He ZJ Yin LC Pi HF Jiang Y Li KY et al . Sanguinarine suppresses oral squamous cell carcinoma progression by targeting the Pkm2/Tfeb aix to inhibit autophagic flux. Phytomedicine. (2025) 136:156337. doi: 10.1016/j.phymed.2024.156337

83.

Teng Y Ren Y Sayed M Hu X Lei C Kumar A et al . Plant-derived Exosomal Micrornas shape the gut microbiota. Cell Host Microbe. (2018) 24:637–52.e8. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2018.10.001

84.

Teng Y Luo C Qiu X Mu J Sriwastva MK Xu Q et al . Plant-nanoparticles enhance anti-Pd-L1 efficacy by shaping human commensal microbiota metabolites. Nat Commun. (2025) 16:1295. doi: 10.1038/s41467-025-56498-2

85.

Liang F Zheng Y Zhao C Li L Hu Y Wang C et al . Microalgae-derived extracellular vesicles synergize with herbal hydrogel for energy homeostasis in osteoarthritis treatment. ACS Nano. (2025) 19:8040–57. doi: 10.1021/acsnano.4c16085

Summary

Keywords

osteoarthritis, Chinese herbal medicine monomers, reactive oxygen species, mitophagy, mitochondrion

Citation

Lei R and Zhou C (2025) The role of reactive oxygen species-mitophagy regulation in the treatment of osteoarthritis by active Chinese herbal medicine monomers: a review. Front. Med. 12:1686190. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2025.1686190

Received

15 August 2025

Accepted

20 October 2025

Published

03 November 2025

Volume

12 - 2025

Edited by

Xuchang Zhou, The First Affiliated Hospital of Xiamen University, China

Reviewed by

Chunhao Cao, Hong Kong Baptist University, Hong Kong SAR, China

Baolong Liu, Cancer Hospital of China Medical University, China

Dongxue Wang, University of Macau, Macao SAR, China

Updates

Copyright

© 2025 Lei and Zhou.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Chaoqing Zhou, chaoqingzhou@126.com

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.