Abstract

Background:

Ex vivo perfusion models to simulate aqueous humor dynamics are commonly used to test interventions for glaucoma treatment. Many models, however, overestimate the effect of surgical interventions. Periorbital tissue is routinely removed during the experimental preparation. Evidence suggests that up to 50% of total outflow resistance is attributable to the distal outflow pathways. It is currently unclear if varying degrees of tissue removal alone elicit changes in total outflow facility (Ctot). We compared Ctot in whole globes with and without preserved periorbital tissue with intact trabecular meshwork (TM) and with surgical TM bypass in an ex vivo perfusion model.

Methods:

A total of 33 post-mortem porcine eyes with intact surrounding tissue were either trimmed (TISS−, n = 17) or left unchanged (TISS+, n = 16). Constant-flow perfusion at 4.5 μL/min and IOP measurement in the anterior chamber were performed. In a subgroup of 13 globes, a 5 mm goniotomy was performed before perfusion (7 TISS+, 6 TISS−). Ctot was analyzed once a stable equilibrium was reached.

Results:

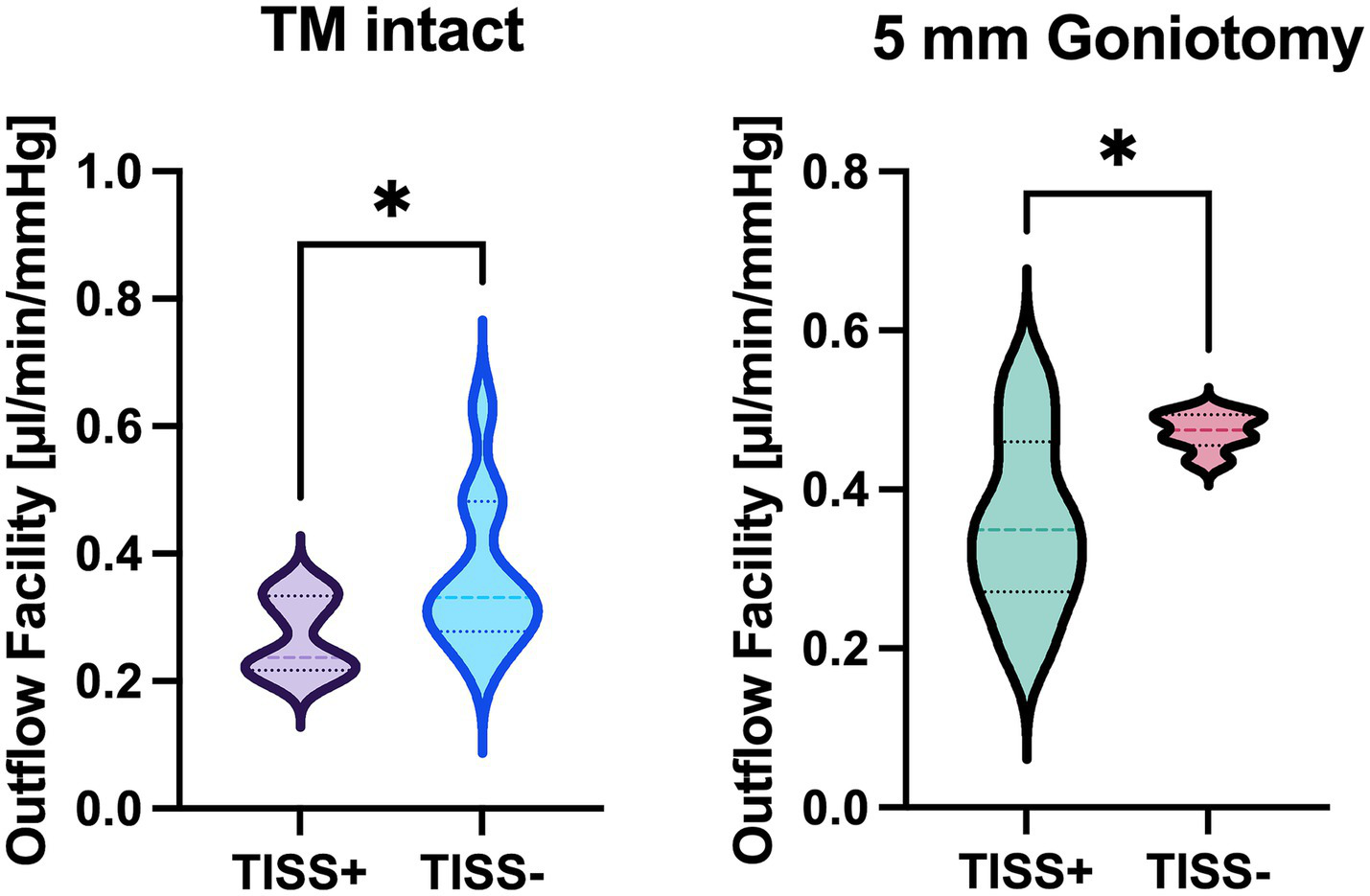

Ctot was 0.27 ± 0.06 with intact TM and 0.36 ± 0.11 μL/mmHg/min with goniotomy in TISS+ globes, as well as 0.36 ± 0.12 and 0.47 ± 0.02 μL/mmHg/min in TISS− globes. Both comparisons (TM intact/ goniotomy) between TISS+ and TISS− globes were statistically significant (TM intact: p = 0.044, goniotomy: p = 0.031).

Conclusion:

This study demonstrates the influence of distal outflow pathways on Ctot with intact TM and after goniotomy. Thus, tissue preparation is a potential confounder in ex vivo AHO perfusion setups and may contribute to the different effect sizes of TM bypass surgery between ex vivo and in vivo studies.

Introduction

Intraocular pressure (IOP) is the most important risk factor for glaucoma, and IOP lowering is the mainstay of glaucoma treatment (1). The modified Goldmann equation expresses steady-state intraocular pressure (IOP) as the balance between aqueous humor production and outflow facility, with episcleral venous pressure (EVP) as an additive factor (2). The structures downstream of Schlemm’s canal (including EVP) are commonly termed ‘distal outflow structures’ and known to account for up to 50% of the total outflow facility (i.e., the combination of trabecular meshwork (TM) and distal outflow facility) (3, 4). For the study of aqueous humor dynamics, ex vivo models are frequently used, and a recent consensus paper guides the optimal usage of such models (5). An important shortcoming of ex vivo models, however, is the incomplete modelling of the distal outflow resistance: EVP is zero, and the periorbital tissue (conjunctiva, portions of the episcleral, as well as eyelids and periorbital fat) is trimmed during tissue preparation. In our own unpublished experience with aqueous angiography, after tissue removal, we can sometimes see direct and immediate tracer flow through the cut aqueous and episcleral vein after tracer application, indicating that normal tissue anatomy is disrupted. Hence, in the present study, we set out to investigate the effect of periorbital tissue (including conjunctival portions of the episclera, periorbital fat, and eyelids) on the total outflow facility (Ctot) in a porcine ex vivo perfusion model with the TM intact and after trabecular bypass surgery (goniotomy). In order to do so, Ctot between eyes with intact periorbital tissue (TISS+) or trimmed periorbital tissue (TISS− group) was compared during whole globe perfusion with the TM intact and after goniotomy.

Methods

Thirty-three porcine eyes were acquired from a local abattoir immediately after the animals were sacrificed and transported to the laboratory. All eyes were stored in a moist environment at 4 °C and used within 24 h after collection. In the TISS+ group (n = 16), all orbital tissues were left intact, i.e., the conjunctiva, including the fornix, was intact (Supplementary Figure 1B). The medial and lateral canthus were cut gently to release tension and the weight of the eyelids from the bulbus, but the eyelids were otherwise left intact. In the TISS− group (n = 17), all surrounding ocular tissues were trimmed, and only a 5 mm conjunctival base was left at the limbus (Supplementary Figure 1A). After initial tissue preparation, both groups were handled using the same experimental protocol. A 25G needle was inserted into the anterior chamber and connected to a pressure transducer (MLT0380/A, ADInstruments Ltd., Oxford, United Kingdom) to measure IOP continuously. A second 25G needle was inserted into the anterior chamber parallel to the iris and positioned in the posterior chamber to simulate aqueous humor inflow (Supplementary Figure 1C). This needle was connected to a syringe pump (AL-1000, World Precision Instruments Germany, Friedberg, Germany). In 13 globes (7 TISS+, 6 TISS−), a needle goniotomy was performed as previously described (6). In short, globes were placed under a stereo microscope (OZM-922, Kern Optics, Balingen, Germany), and, via a paracentesis, a 25G needle was inserted. Using a surgical gonioscopy prism, the TM was visualized, and 5 mm cut was made with the needle tip. Afterward, the paracentesis was sealed using cyanoacrylate glue. In the experimental group with intact TM, the goniotomy was omitted. Perfusion was started with the flow rate set to 4.5 μL/min (at room temperature), and a stable equilibrium (defined as IOP change < 1 mmHg over 15 min) was awaited (5–8). Total outflow facility (Ctot) was calculated by dividing the constant perfusion rate by the measured intraocular pressure average within a 20-min analysis period. Figure 1 illustrates the experimental protocol using a representative tracing: the grey bar highlights the stabilization period, and the blue bar the analyzed data segment. All data were recorded continuously using a digital data recording system (PowerLab C and LabChart 8, ADInstruments Ltd., Oxford, United Kingdom). Unpaired t-tests were used to compare Ctot values between TISS+ and TISS− globes (Prism GraphPad 10, GraphPad Software Inc., Boston, MA).

Figure 1

Representative single tracing of IOP (upper panel) and total outflow facility (lower panel) over time in a representative TISS+ globe with intact TM. Blue box: stability evaluation period and grey box: analyzed segment.

Results

In all eyes, a stable equilibrium was reached. With the TM intact, Ctot was 0.27 ± 0.06 μL/mmHg/min in TISS+ globes and 0.36 ± 0.12 μL/mmHg/min in TISS− globes. After surgical TM bypass, TISS+ globes showed a Ctot of 0.36 ± 0.11 μL/mmHg/min and TISS− globes a Ctot of 0.47 ± 0.02 μL/mmHg/min. As visualized in Figure 2, differences between TISS+ and TISS− were statistically significant for globes with intact TM (p = 0.0443) and for globes after TM bypass (p = 0.0310).

Figure 2

Total outflow facility comparison between TISS+ and TISS− globes with intact TM (left panel) and after goniotomy (right panel). *p < 0.05 for unpaired t-test.

Discussion

In this study, we report significant outflow facility differences between eyes with and without preserved periorbital tissue after trabecular bypass surgery and with intact TM. Ctot values in the TISS− groups are comparable to previously published outflow facilities in porcine anterior segment and whole globe perfusion setups, although previously reported values are subject to notable inter-study variability (4, 7, 9–22). The exact reason for the observed Ctot differences between TISS+ and TISS− globes is currently unknown, and research of involved anatomical structures has been proven to be intricate: A recent consensus statement on ex vivo AHO perfusion setups acknowledges the incomplete modelling of the distal outflow resistance after Schlemm’s canal (collector channels, scleral vessels, and episcleral circulation) as a significant model limitation (5). Although distal outflow resistance has been identified as a significant and pharmacologically modifiable contributor to total outflow resistance in porcine and human anterior segments with trimmed conjunctiva (4), the role of downstream anatomical structures, including the episcleral circulation in IOP regulation, is still unclear. The episcleral circulation has unique and partially unexplored features suggesting a role in IOP homeostasis: 1) lack of a capillary bed, 2) two distinct types of autonomously innervated arteriovenous anastomoses (AVAs) in multiple species (23–27), and 3) the capability of these AVAs to alter IOP and EVP upon pharmacological manipulation and/or neuronal stimulation in rabbits and rats (28–31). Owing to this complex vascular architecture, EVP measurement itself has yielded varying results over the years, depending on the species, location of measurement, and measurement method (31–33). Due to the lack of venous pressure in ex vivo models for AHO (another limitation stated in the above-mentioned consensus statement), the uncertainty concerning EVP has conventionally been irrelevant in these reductionist scenarios. By omitting EVP, the outflow facility can be calculated by dividing the rate of inflow by IOP in these models (2, 5). This also holds true for the calculation of the total outflow facility in TISS+ and TISS− globes in this report. To address the limitation of missing EVP, we recently presented an experimental approach to simulate above-zero EVP values by ophthalmic artery perfusion (34).

The effect size of intact periorbital tissue on total outflow facility (~30%) is comparable between globes with and without goniotomy. Of note, TISS− globes with intact TM and TISS+ eyes after goniotomy had a comparable mean Ctot of 0.36, suggesting a similar effect of intact conjunctiva/episcleral and intact TM on Ctot—at least in our porcine whole globe perfusion setup. More experiments, including intraluminal pressure measurements along the outflow pathway, are necessary to precisely determine the mentioned effect sizes. In their current form, the findings of the present study indicate that the periorbital tissue and its imposed outflow resistance may be a confounder when ex vivo aqueous humor dynamics models are used.

We are aware that our results are of a preliminary character, and the setup used has shortcomings that need to be acknowledged. First of all, only relatively short-term perfusions have been performed. Furthermore, perfusion has been performed at room temperature. This is based on previous studies using a similar setup that allowed for measurements for up to 7 h before the well-known washout phenomenon set in, and this model has been used successfully for surgical interventions in the past (6, 8). A stable equilibrium could, however, be reached in all eyes, indicating the validity of the data for the observed time period, and no difference in the appearance of eyes between the groups was noted.

Moreover, we did not measure intraluminal pressures in episcleral vessels. While this information would undoubtedly be of high scientific interest, the complex architecture of the episcleral circulation and dependency on position relative to AVAs complicate such measurements. Finally, our current approach cannot answer which exact anatomical structures that were removed/compromised in the TISS− group are responsible for the observed Ctot differences (i.e., where the increased resistance in the TISS+ group is generated). Simultaneously, multipoint intraluminal pressure, as well as episcleral flow measurements combined with in silico simulations, might overcome the latter two limitations in the future (35).

In summary, this report highlights the influence of periorbital tissue integrity on outflow biology in ex vivo AHO perfusion setups. Therefore, researchers ought to be aware of tissue preparation as a potential confounder in studies involving these setups, especially when focusing on the characteristics of the distal outflow pathways. More studies are necessary to precisely characterize the exact anatomical structures in the periorbital tissue contributing most to the observed facility difference, to study the effect of intraluminal pressures, and to analyze potential regulation mechanisms.

Statements

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

Ethical approval was not required for the study involving animals in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements because the study involved ex-vivo porcine eyes obtained from a local abattoir—collected after the animals were sacrificed.

Author contributions

MK: Investigation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. SK: Investigation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. PP: Data curation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. SH: Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. MB: Supervision, Validation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. AH: Supervision, Validation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. CS: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Project administration, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declared that financial support was received for this work and/or its publication. This study was supported by the Adele Rabensteiner Foundation, the JKU Clinician Scientist Program (MK), the JKU KMA Program (CS), the JKU Impetus Program (Project Number I-03-22), the Austrian Science Fund (FWF, Grant DOI: 10.55776/PAT4100224), and the National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD (grant number: R01EY030501. Research to Prevent Blindness David Epstein Career Advancement Award in Glaucoma Research sponsored by Alcon (AH) and an unrestricted grant from Research to Prevent Blindness (New York, NY) [UCSD]. The funding covered both personnel costs and general lab materials. No funding agencies were involved in the study‘s design or manuscript preparation. Open access funding provided by Johannes Kepler University Linze.

Conflict of interest

The author(s) declared that this work was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declared that Generative AI was not used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fmed.2025.1705023/full#supplementary-material

SUPPLEMENTARY FIGURE 1Pictures of the experimental setup in the TISS− (A) and TISS+ (B) group. (C) A magnified view of the needle position in the anterior and posterior chamber.

References

1.

Leske MC Heijl A Hyman L Bengtsson B Dong L Yang Z . Predictors of long-term progression in the early manifest glaucoma trial. Ophthalmology. (2007) 114:1965–72. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2007.03.016

2.

Goldmann H . Out-flow pressure, minute volume and resistance of the anterior chamber flow in man. Doc Ophthalmol. (1951) 5-6:278–356. doi: 10.1007/BF00143664,

3.

Barany EH . A mathematical formulation of intraocular pressure as dependent on secretion, ultrafiltration, bulk outflow, and osmotic reabsorption of fluid. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. (1963) 2:584–90.

4.

McDonnell F Dismuke WM Overby DR Stamer WD . Pharmacological regulation of outflow resistance distal to Schlemm’s canal. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. (2018) 315:C44–51. doi: 10.1152/AJPCELL.00024.2018,

5.

Acott TS Fautsch MP Mao W Ethier CR Huang AS . Consensus recommendations for studies of outflow facility and intraocular pressure regulation using ex vivo perfusion approaches. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. (2024) 65:32. doi: 10.1167/iovs.65.14.32,

6.

Strohmaier CA Wanderer D Zhang X Agarwal D Toomey CB Wahlin K et al . Greater outflow facility increase after targeted trabecular bypass in Angiographically determined low-flow regions. Ophthalmol Glaucoma. (2023b) 6:570–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ogla.2023.06.008,

7.

Dang Y Wang C Shah P Waxman S Loewen RT Hong Y et al . Outflow enhancement by three different ab interno trabeculectomy procedures in a porcine anterior segment model. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. (2018) 256:1305–12. doi: 10.1007/s00417-018-3990-0,

8.

Strohmaier CA McDonnell FS Zhang X Wanderer D Stamer WD Weinreb RN et al . Differences in outflow facility between angiographically identified high- versus low-flow regions of the conventional outflow pathways in porcine eyes. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. (2023a) 64:29. doi: 10.1167/iovs.64.3.29,

9.

Birke MT Birke K Lütjen-Drecoll E Schlötzer-Schrehardt U Hammer CM . Cytokine-dependent ELAM-1 induction and concomitant intraocular pressure regulation in porcine anterior eye perfusion culture. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. (2011) 52:468–75. doi: 10.1167/iovs.10-5990,

10.

Dang Y Wang C Shah P Waxman S Loewen RT Loewen NA . RKI-1447, a rho kinase inhibitor, causes ocular hypotension, actin stress fiber disruption, and increased phagocytosis. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. (2019) 257:101–9. doi: 10.1007/s00417-018-4175-6,

11.

Dismuke WM Ellis DZ . Activation of the BK(ca) channel increases outflow facility and decreases trabecular meshwork cell volume. J Ocul Pharmacol Ther. (2009) 25:309–14. doi: 10.1089/jop.2008.0133,

12.

Dismuke WM Mbadugha CC Faison D Ellis DZ . Ouabain-induced changes in aqueous humour outflow facility and trabecular meshwork cytoskeleton. Br J Ophthalmol. (2009) 93:104–9. doi: 10.1136/bjo.2008.142133,

13.

Ellis DZ Dismuke WM Chokshi BM . Characterization of soluble guanylate cyclase in NO-induced increases in aqueous humor outflow facility and in the trabecular meshwork. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. (2009) 50:1808–13. doi: 10.1167/iovs.08-2750,

14.

Epstein DL Rowlette LL Roberts BC . Acto-myosin drug effects and aqueous outflow function. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. (1999) 40:74–81.

15.

Faralli JA Filla MS Peters DM . Effect of αvβ3 integrin expression and activity on intraocular pressure. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. (2019) 60:1776–88. doi: 10.1167/iovs.18-26038,

16.

Fujimoto T Inoue T Kameda T Kasaoka N Inoue-Mochita M Tsuboi N et al . Involvement of RhoA/rho-associated kinase signal transduction pathway in dexamethasone-induced alterations in aqueous outflow. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. (2012) 53:7097–108. doi: 10.1167/iovs.12-9989,

17.

Goldwich A Ethier CR Chan DW-H Tamm ER . Perfusion with the olfactomedin domain of myocilin does not affect outflow facility. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. (2003) 44:1953–61. doi: 10.1167/iovs.02-0863,

18.

Khurana RN Deng P-F Epstein DL Vasantha Rao P . The role of protein kinase C in modulation of aqueous humor outflow facility. Exp Eye Res. (2003) 76:39–47. doi: 10.1016/s0014-4835(02)00255-5,

19.

Njie YF Qiao Z Xiao Z Wang W Song Z-H . N-arachidonylethanolamide-induced increase in aqueous humor outflow facility. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. (2008) 49:4528–34. doi: 10.1167/iovs.07-1537,

20.

Oltmann J Morell M Dakroub M Verma-Fuehring R Hillenkamp J Loewen N . VEGF-A-induced changes in distal outflow tract structure and function. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. (2024) 262:537–43. doi: 10.1007/s00417-023-06252-5,

21.

Ramos RF Stamer WD . Effects of cyclic intraocular pressure on conventional outflow facility. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. (2008) 49:275–81. doi: 10.1167/iovs.07-0863,

22.

Yang Y-F Sun YY Acott TS Keller KE . Effects of induction and inhibition of matrix cross-linking on remodeling of the aqueous outflow resistance by ocular trabecular meshwork cells. Sci Rep. (2016) 6:30505. doi: 10.1038/srep30505,

23.

Funk RH Mayer B Wörl J . Nitrergic innervation and nitrergic cells in arteriovenous anastomoses. Cell Tissue Res. (1994) 277:477–84. doi: 10.1007/BF00300220,

24.

Ladek AM Trost A Bruckner D Schroedl F Kaser-Eichberger A Lenzhofer M et al . Immunohistochemical characterization of neurotransmitters in the episcleral circulation in rats. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. (2019) 60:3215–20. doi: 10.1167/iovs.19-27109,

25.

Selbach JM Buschnack SH Steuhl K-P Kremmer S Muth-Selbach U . Substance P and opioid peptidergic innervation of the anterior eye segment of the rat: an immunohistochemical study. J Anat. (2005a) 206:237–42. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7580.2005.00379.x,

26.

Selbach JM Rohen JW Steuhl KP Lutjen-Drecoll E . Angioarchitecture and innervation of the primate anterior episclera. Curr Eye Res. (2005b) 30:337–44. doi: 10.1080/02713680590934076,

27.

Selbach JM Schonfelder U Funk RH . Arteriovenous anastomoses of the episcleral vasculature in the rabbit and rat eye. J Glaucoma. (1998) 7:50–7. doi: 10.1097/00061198-199802000-00010,

28.

Funk RH Gehr J Rohen JW . Short-term hemodynamic changes in episcleral arteriovenous anastomoses correlate with venous pressure and IOP changes in the albino rabbit. Curr Eye Res. (1996) 15:87–93. doi: 10.3109/02713689609017615,

29.

Strohmaier CA Kiel JW Reitsamer HA . Episcleral venous pressure response to brain stem stimulation: effect of topical lidocaine. Exp Eye Res. (2021) 212:108766. doi: 10.1016/j.exer.2021.108766,

30.

Strohmaier CA Reitsamer HA Kiel JW . Episcleral venous pressure and IOP responses to central electrical stimulation in the rat. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. (2013) 54:6860–6. doi: 10.1167/iovs.13-12781,

31.

Zamora DO Kiel JW . Topical proparacaine and episcleral venous pressure in the rabbit. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. (2009) 50:2949–52. doi: 10.1167/iovs.08-3048,

32.

Sit AJ McLaren JW . Measurement of episcleral venous pressure. Exp Eye Res. (2011) 93:291–8. doi: 10.1016/j.exer.2011.05.003,

33.

Sultan M Blondeau P . Episcleral venous pressure in younger and older subjects in the sitting and supine positions. J Glaucoma. (2003) 12:370–3. doi: 10.1097/00061198-200308000-00013,

34.

Kallab M Casazza M Schneider S Murauer O Reisinger A Bolz M et al . The effect of simulated episcleral venous pressure on total outflow facility in an ex-vivo porcine model for aqueous humor dynamics. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. (2024) 65:1263.

35.

Strohmaier CA Kallab M Oechsli S Huang AS Saeedi OJ . Minimally invasive Glaucoma surgery and the distal aqueous outflow system: the final frontier?Ophthalmol Glaucoma. (2025) 8:209–12. doi: 10.1016/j.ogla.2024.11.006,

Summary

Keywords

aqueous humor dynamics, distal outflow, glaucoma, minimally invasive glaucoma surgery (MIGS), porcine model

Citation

Kallab M, Kaltenboeck S, Panahi P, Hinterberger S, Bolz M, Huang AS and Strohmaier CA (2026) Total outflow facility before and after goniotomy in ex vivo perfusion models for aqueous humor dynamics: effect of periocular tissue. Front. Med. 12:1705023. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2025.1705023

Received

14 September 2025

Revised

14 December 2025

Accepted

19 December 2025

Published

12 January 2026

Volume

12 - 2025

Edited by

Karanjit Kooner, University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, United States

Reviewed by

Ivan Šoša, University of Rijeka, Croatia

Guorong Li, Duke University, United States

Updates

Copyright

© 2026 Kallab, Kaltenboeck, Panahi, Hinterberger, Bolz, Huang and Strohmaier.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Clemens A. Strohmaier, clemens.strohmaier@kepleruniklinikum.at

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.