Abstract

Background:

Sepsis, a leading cause of mortality in intensive care units, is associated with coagulation dysfunction, a key pathological feature linked to multi-organ failure. However, the prognostic value of coagulation markers remains heterogeneous across studies.

Objective:

This meta-analysis aimed to evaluate the association between coagulation parameters and clinical outcomes in sepsis patients, focusing on their predictive performance.

Methods:

Following PRISMA guidelines, nine studies (n = 1954) were included from PubMed, Embase, Cochrane Library, and Web of Science. The associations of coagulation markers (APTT, PT, D-dimer, fibrinogen, INR) and SOFA scores with the outcome were quantified using pooled odds ratios (ORs) with 95% confidence intervals. Diagnostic accuracy was summarized by the area under the curve (AUC). Heterogeneity was assessed using the I2 statistic, and a random-effects model was employed to account for between-study variation. The robustness of the findings was evaluated through sensitivity analyses.

Results:

Fibrinogen showed a significant inverse correlation with mortality [OR = 0.76, 95% CI (0.59–0.97)], while INR demonstrated moderate predictive ability (AUC = 0.68). APTT and PT had non-significant ORs but moderate AUCs (0.75 and 0.75, respectively). D-dimer and SOFA score ORs were non-significant, though SOFA’s AUC indicated good prognostic utility. High heterogeneity (I2 > 74%) and sensitivity to individual studies were noted.

Conclusion:

Specific coagulation markers, notably fibrinogen and INR, may aid in sepsis prognosis assessment, but variability across studies limits generalizability. Further high-quality studies are warranted to validate these findings.

Systematic review registration:

https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/PROSPERO/view/CRD420251049209, identifier CRD420251049209.

1 Introduction

Sepsis is one of the leading causes of mortality worldwide, especially in intensive care units (ICUs), where its high incidence and mortality rates lead to a significant disease burden (1). The pathogenesis of sepsis is complex, primarily involving an exaggerated immune response triggered by infection, systemic inflammatory response, and microvascular dysfunction, which ultimately leads to multi-organ failure (2). Although early diagnosis and timely treatment can significantly improve the prognosis of some patients, a considerable number of patients still fail to benefit due to the inability to identify high-risk groups in a timely manner or worsening of their condition, ultimately leading to ineffective control of the disease. Therefore, identifying biomarkers that can accurately assess the severity and prognosis of sepsis, particularly clinical indicators of coagulation dysfunction, has become an important focus in current sepsis research.

Coagulation dysfunction is a core feature of the pathological process in sepsis (3). The imbalance between the coagulation and fibrinolysis systems is considered one of the key factors in the multi-organ failure induced by sepsis (4). Sepsis activates widespread coagulation responses, especially the extrinsic and intrinsic coagulation pathways and the fibrinolysis system, which may ultimately lead to life-threatening complications such as disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC) (5). Prothrombin time (PT) and activated partial thromboplastin time (APTT) are commonly used coagulation tests that reflect coagulation factor consumption in sepsis patients (6), with prolonged values closely associated with the course of sepsis, organ failure, and mortality risk. The international normalized ratio (INR), a standardized measure of PT, is typically elevated when there is coagulation factor deficiency or suppressed coagulation function, which is also commonly observed in late-stage sepsis (6). Additionally, D-dimer, a product generated during fibrinolysis, is frequently elevated in sepsis patients, indicating excessive coagulation activation and fibrinolysis inhibition (6, 7). Fibrinogen (Fib) is another coagulation marker reflecting acute-phase responses. Its elevated levels are common in the early stages of sepsis, while a decrease in Fib as the disease progresses and coagulation factors are consumed may indicate more severe coagulation dysfunction (4). Although the roles of these coagulation markers in sepsis have been confirmed in several independent studies, there remains significant heterogeneity in the comprehensive evaluation of their prognostic value and their interrelationships in sepsis prognosis.

Currently, commonly used prognostic tools for sepsis, such as the SOFA score, can reflect organ dysfunction to some extent, but their sensitivity to coagulation dysfunction is relatively weak (8). Therefore, combining coagulation function parameters with traditional scoring systems to form a more accurate multi-parameter assessment model holds important clinical significance. In recent years, integrated scoring systems such as the ISTH, KSTH, and JAAM criteria have been increasingly applied to evaluate sepsis-associated coagulopathy (9). These frameworks have enhanced diagnostic consistency and prognostic precision. Nevertheless, the individual coagulation parameters that constitute the foundation of these scoring systems continue to provide essential information for clinical assessment, particularly in the early stages of sepsis or in resource-limited settings where comprehensive scoring is not always feasible. Although some coagulation markers have been used individually to predict sepsis prognosis, the lack of systematic evaluation of the combined predictive ability of these markers, due to differences in sample size, study design, and measurement methods, remains a significant gap in the literature (10).

This study aims to systematically evaluate the correlation between coagulation function markers and clinical outcomes in sepsis patients through meta-analysis, further exploring the clinical predictive value of different coagulation markers in early sepsis assessment. By quantifying the relationship between coagulation dysfunction and the prognosis of sepsis patients, this study hopes to provide more comprehensive and precise prognostic assessment tools for clinical practice and offer evidence-based support for the precise management of sepsis.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Search strategy

This study was designed and reported according to the PRISMA guidelines. A comprehensive literature search was conducted across four databases: PubMed, Embase, Cochrane Library, and Web of Science. The search was conducted from the inception of each database up to April 2025. The search strategy utilized a combination of MeSH terms and free-text keywords, including “Sepsis,” “Coagulation,” “mortality” and “prognosis,” with appropriate adjustments for each database’s specific syntax. Reference lists of the included studies were manually checked to identify any additional relevant studies.

2.2 Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Inclusion criteria: (1) Observational studies or randomized controlled trials (RCTs); (2) Participants diagnosed with sepsis; (3) Studies reporting at least one coagulation function parameter (such as APTT, D-Dimer, Fibrinogen, INR, PT) and its association with key clinical outcomes (such as mortality, organ dysfunction, ICU stay duration, or mechanical ventilation usage), with corresponding OR or AUC values provided. OR quantifies the association between coagulation markers and mortality risk, while AUC evaluates their overall prognostic discrimination.

Exclusion criteria: (1) Studies that are not observational studies or RCTs, such as reviews, commentaries, editorials, or non-research articles; (2) Studies that do not assess the relationship between coagulation function parameters and sepsis prognosis; (3) Studies with incomplete data that cannot be calculated from the provided information, and for which the authors could not be contacted for clarification, were excluded from the analysis.

2.3 Study selection and data extraction

Two reviewers independently screened the titles and abstracts of identified articles. Full-text reviews were conducted for potentially eligible studies, and data extraction was carried out independently by two reviewers. Extracted data included study design, sample size, patient characteristics, coagulation function parameters analyzed, and reported outcomes. In case of missing data, the authors were contacted for clarification. During study selection, any disagreements between the two independent reviewers were resolved through consensus discussion, with arbitration by a third senior investigator when necessary.

2.4 Risk of bias assessment

The risk of bias in the included studies was assessed using the PROBAST tool, which evaluates potential biases in participant selection, measurement of coagulation parameters, outcome assessment, and statistical analysis. It systematically evaluates potential biases across four key domains: participant selection, predictors, outcome assessment, and statistical analysis. Disagreements between reviewers were resolved through consensus or by consulting a third reviewer.

2.5 Statistical methods

Meta-analysis was performed using R software (version 4.3.3) with the “meta” and “metafor” packages. For predicted outcomes, the area under the curve (AUC) values were used, while for dichotomous outcomes, odds ratios (OR) were calculated. The results were expressed as odds ratios with 95% confidence intervals (CIs). Heterogeneity was assessed using the I2 statistic, with a random-effects model applied if I2 ≥ 50%, and a fixed-effect model used if I2 < 50%. Sensitivity analysis was performed to assess the robustness of the results.

3 Results

31 Literature search results and general characteristics

A total of 1,613 relevant articles were identified through searches in domestic and international databases. After applying the inclusion and exclusion criteria, 9 studies (11–19) were included, involving a total of 1,954 patients. The literature screening flowchart is shown in Figure 1, and the basic characteristics of the included studies are presented in Table 1.

FIGURE 1

Flow chart.

TABLE 1

| First author | Publication year | Number of cases | Age (year) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Exposure group | Control group | Exposure group | Control group | ||

| Liu (17) | 2021 | 17 | 49 | 77(63–84) | 69(54–82) |

| Semeraro (19) | 2019 | 89 | 89 | 70(62–77) | 71(63–77) |

| Fu (13) | 2023 | 44 | 94 | 70.56 ± 14.44 | 65.36 ± 16.91 |

| Levi (16) | 2020 | 191 | 194 | 63(55–74) | 63(55–75) |

| Iba (14) | 2018 | 419 | 30 | 77(73–82) | 74(65–82) |

| Czempik (12) | 2022 | 139 | 78 | 66(58–74) | 67(56.5–57.2) |

| Lorente (18) | 2022 | 80 | 134 | 62.7 ± 13.9 | 55.7 ± 15.4 |

| Bui-Thi (11) | 2023 | 91 | 70 | 69(60–81) | |

| Lemiale (15) | 2022 | 64 | 82 | 65(57–72) | 61(49–66) |

Baseline characteristics.

3.2 Risk of bias assessment for the included studies

In this meta-analysis, we assessed the risk of bias for 9 studies. Overall, most studies showed a low risk of bias in research subjects and ending. However, several studies had unclear information regarding analysis, predicted facto, which prevented the complete exclusion of bias risk in these areas (Table 2; Figure 2).

TABLE 2

| Risk of bias | Applicability | Overall | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study | Research subjects | Predictive factors | Ending | Analysis | Research subjects | Predictive factors | Ending | Risk of bias | Applicability |

| Liu | + | ? | + | + | + | + | + | ? | + |

| Semeraro | + | ? | + | ? | + | ? | + | ? | ? |

| Fu | − | − | + | + | − | + | + | − | − |

| Levi | + | ? | + | ? | + | ? | + | ? | ? |

| Iba | − | − | + | + | − | + | + | − | − |

| Czempik | + | − | ? | − | + | + | ? | − | ? |

| Lorente | + | ? | + | + | + | + | + | ? | + |

| Bui-Thi | ? | + | + | + | ? | + | + | ? | ? |

| Lemiale | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + |

Schematic table of PROBAST assessment results.

Low risk: +; High risk: −;Unclear: ?

FIGURE 2

Risk of bias graphs.

3.3 APTT

In the evaluation of APTT as a prognostic marker for sepsis patients, we included two studies. The meta-analysis of OR values showed that the OR for APTT in predicting sepsis prognosis was 2.32 [95% CI (0.45; 11.92)], which was not statistically significant. The heterogeneity test indicated I2 = 96.4%, τ2 = 1.3455, p < 0.0001, suggesting severe heterogeneity in the OR values of APTT across the studies. However, the pooled AUC result indicated an AUC value of 0.75 [95% CI (0.67; 0.82)] with no significant heterogeneity between studies, indicating that APTT has some value in predicting the prognosis of sepsis patients (Figure 3).

FIGURE 3

(A) Meta-analysis for OR of APTT. (B) Meta-analysis for AUC of APTT.

3.4 PT

A total of two studies involved PT, with I2 = 92.5%, τ2 = 1.1623, and p = 0.0003. Based on this, we selected a random-effects model for analysis. The results showed that the pooled effect size OR for PT was 2.37 [95% CI (0.50; 11.14)], indicating that PT has no significant correlation with sepsis prognosis and that its effectiveness in predicting the prognosis of sepsis patients varies considerably (Figure 4).

FIGURE 4

![Forest plot showing meta-analysis results of two studies, Liu 2021 and Lemiale 2022. Liu 2021 has a logOR of 0.1266 and SE(logOR) of 0.0496, while Lemiale 2022 has a logOR of 1.7120 and SE(logOR) of 0.4317. Odds ratios with 95% confidence intervals are 1.14 [1.03; 1.25] for Liu 2021 and 5.54 [2.38; 12.91] for Lemiale 2022. Common effect model OR is 1.16 [1.05; 1.28], and random effects model OR is 2.37 [0.50; 11.14]. Heterogeneity statistics indicate I² = 92.5%, τ² = 1.1623, p = 0.0003.](https://www.frontiersin.org/files/Articles/1706082/xml-images/fmed-12-1706082-g004.webp)

Meta-analysis for OR of PT.

3.5 D-Dimer

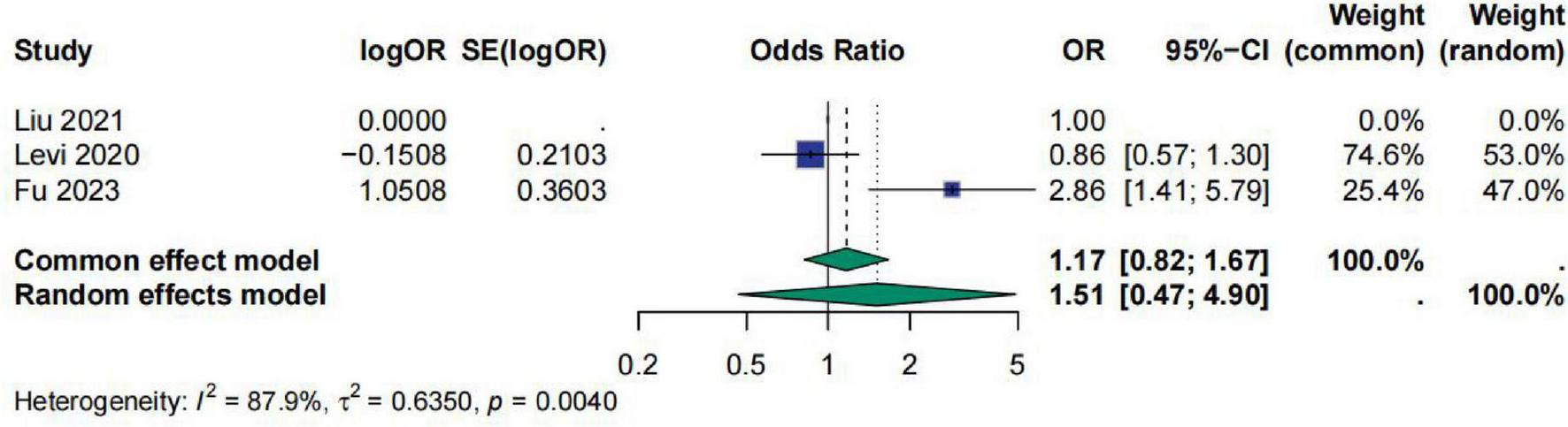

For the studies on D-Dimer, a total of three studies were included. The meta-analysis results showed that the pooled effect size OR for D-Dimer was 1.51 [95% CI (0.47; 4.90)], and the heterogeneity test indicated I2 = 87.9%, τ2 = 0.6350, p = 0.0040. This suggests that D-Dimer has no significant correlation with sepsis prognosis and there is considerable heterogeneity among the studies. The role of D-dimer in predicting the prognosis of sepsis patients therefore remains highly uncertain (Figure 5).

FIGURE 5

Meta-analysis for OR of D-Dimer.

3.6 Fibrinogen

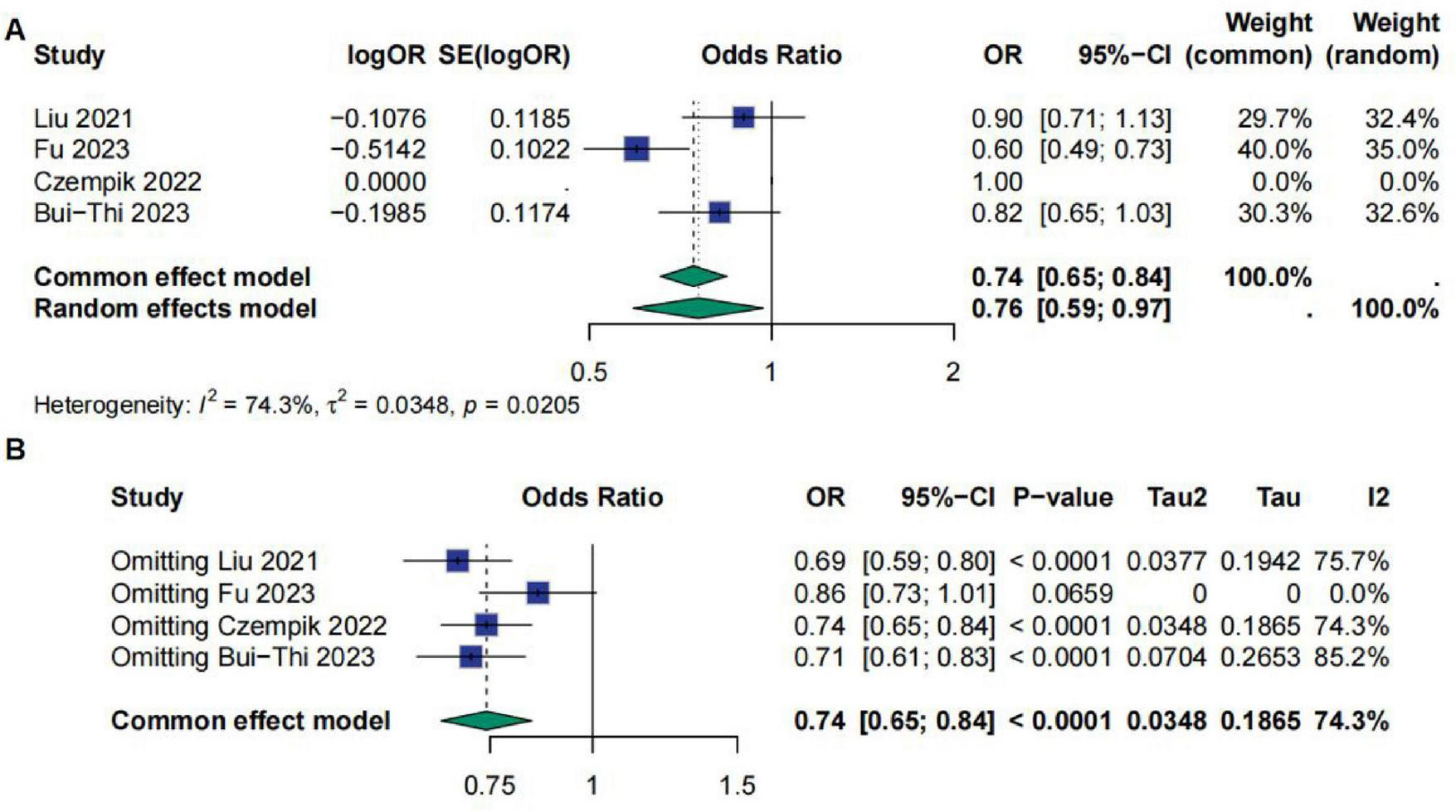

A total of four studies involved Fib (fibrinogen). The meta-analysis results indicated that the OR for Fib was 0.76 [95% CI (0.59; 0.97)], suggesting a significant correlation between Fib and sepsis prognosis. However, the results showed high heterogeneity, with I2 = 74.3%, τ2 = 0.0348, and p = 0.0205. Sensitivity analysis demonstrated that after excluding the study by Fu et al., the results became non-significant (Figure 6).

FIGURE 6

(A) Meta-analysis for OR of Fib. (B) Sensitive analysis for Fib.

3.7 INR

Regarding INR, a total of two studies evaluated the predictive efficacy of INR for sepsis prognosis using ROC curves. This study performed a meta-analysis on the AUC values from these studies. The meta-analysis results showed that the AUC value for INR was 0.68 [95% CI (0.62; 0.75)], indicating that INR has moderate predictive ability for sepsis prognosis. The heterogeneity test results indicated I2 = 0.0%, τ2 = 0, and p = 0.3763, suggesting no significant heterogeneity among the studies (Figure 7).

FIGURE 7

Meta-analysis for AUC of INR.

3.8 SOFA score

A total of four studies involved the SOFA score, with two of them reporting the area under the ROC curve for the SOFA score. The meta-analysis results showed that the OR value for the SOFA score was 1.28 [95% CI (0.82; 2.0)], indicating no significant correlation between the SOFA score and sepsis prognosis. However, the studies exhibited high heterogeneity, with I2 = 92.6%, τ2 = 0.1851, and p < 0.0001. Sensitivity analysis also indicated that the results were not robust (Figure 8). Additionally, a meta-analysis of the AUC for the SOFA score revealed an AUC of 0.75 [95% CI (0.65; 0.80)], suggesting that the SOFA score has good predictive ability for sepsis prognosis and shows no significant study heterogeneity (Figure 9).

FIGURE 8

(A) Meta-analysis for OR of SOFA. (B) Sensitive analysis for SOFA.

FIGURE 9

![Forest plot showing a meta-analysis of two studies, Liu 2021 and Iba 2018, with AUC values of 0.7320 and 0.7270, respectively. The common and random effects models both yield AUC values of 0.73 with a 95% confidence interval of [0.65, 0.80]. The heterogeneity is low, with I squared at 0.0% and a p-value of 0.9543. Weight distribution shows Liu 2021 at 27.1% and Iba 2018 at 72.9% for both models.](https://www.frontiersin.org/files/Articles/1706082/xml-images/fmed-12-1706082-g009.webp)

Meta-analysis for AUC of SOFA.

4 Discussion

Sepsis is a systemic inflammatory response syndrome triggered by infection (2, 20), characterized by insidious onset, rapid progression, and high mortality. It can lead to multiple organ dysfunction and even death. Early identification and risk stratification are crucial for improving patient outcomes. In clinical practice, coagulation dysfunction represents a key pathological process in sepsis, with manifestations such as consumption of clotting factors, activation of the fibrinolytic system, and microthrombus formation (4). These changes may not only reflect the severity of illness but also hold potential prognostic value. Therefore, exploring the predictive utility of coagulation-related indicators and scoring systems for sepsis prognosis has important clinical implications.

This meta-analysis synthesized current evidence on the associations of APTT, PT, D-dimer, fibrinogen, INR, and SOFA scores with sepsis prognosis. The findings revealed notable variability in predictive performance across these indicators, with some demonstrating substantial heterogeneity between studies. This heterogeneity may be attributable to differences in patient characteristics, disease stages, treatment regimens, study designs, and laboratory testing standards. In addition, the definitions of outcome events varied among studies—some used 28-day mortality, while others focused on in-hospital death—which may have introduced effect estimate bias and compromised the stability of pooled results.

Although APTT did not demonstrate statistical significance in pooled effect estimates, ROC curve analyses indicated potential predictive value. This discrepancy may reflect the complex regulation of APTT in sepsis. APTT prolongation in critically ill patients does not solely reflect coagulation impairment; it can also be influenced by hypothermia, acidosis, anticoagulation therapy, and inflammatory mediators, none of which were systematically adjusted for in the original studies (21, 22), thereby contributing to inter-study variability. Basic research has suggested that APTT prolongation during the early phase of sepsis may result from interactions between inflammation and the endogenous coagulation system (23), and may not directly indicate adverse outcomes.

PT and INR are commonly used indicators of the extrinsic coagulation pathway, yet they showed divergent results. PT is heavily influenced by laboratory-specific testing standards and thus prone to measurement error and unit inconsistency (24), limiting cross-study comparability. In contrast, INR, which is standardized across reagents, demonstrated more consistent prognostic performance in this meta-analysis. This finding aligns with evidence from large prospective cohorts and suggests that INR may serve as a more stable prognostic marker in sepsis. Moreover, INR may reflect the interplay between hepatic synthetic function and systemic inflammation (25), thus possessing dual clinical relevance in the context of sepsis.

D-dimer, a marker of fibrinolytic system activation, is commonly elevated across a range of clinical conditions but showed limited prognostic utility in sepsis (26), with substantial inter-study heterogeneity. This aligns with ongoing debate regarding the predictive validity of D-dimer in sepsis. Although D-dimer levels increase in conditions such as disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC), acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), and deep vein thrombosis, its specificity in sepsis is limited (27). Some studies have shown that D-dimer is strongly influenced by inflammatory burden, hepatic impairment, and infection source, with non-specific elevations potentially masking its prognostic utility (28). Additionally, inconsistency in threshold definitions and timing of measurement across studies may further explain the lack of significant pooled effects.

Although fibrinogen demonstrated a potential protective effect in pooled analyses, it was also associated with high heterogeneity, and sensitivity analyses suggested strong dependence on individual studies. Fibrinogen acts as an acute-phase reactant and may indicate preserved immune and coagulation compensatory mechanisms when moderately elevated (29), thereby correlating with favorable outcomes. However, excessively high or persistently elevated fibrinogen levels may reflect dysregulated inflammation or endothelial injury, implying a potential biphasic prognostic role. To date, studies exploring the mechanistic role of fibrinogen in sepsis remain limited, and it remains unclear whether dynamic changes in fibrinogen are more prognostically informative than static levels. Further prospective research is needed to validate these findings.

Recent studies have emphasized that dynamic changes in coagulation biomarkers may more accurately reflect disease progression and treatment response than single measurements. For instance, serial monitoring of D-dimer and fibrinogen trends has been shown to predict the transition from compensated to overt disseminated intravascular coagulation (4), while persistent INR elevation or a progressive decline in fibrinogen has been associated with poor outcomes in septic patients receiving anticoagulant therapy (30). Similarly, time-dependent increases in APTT or PT during the disease course may indicate worsening coagulopathy and organ dysfunction, even when baseline levels are inconspicuous (31). These findings suggest that longitudinal assessment of coagulation markers, rather than static values alone, could provide deeper insight into the temporal dynamics of sepsis-associated coagulopathy. Therefore, incorporating serial biomarker trends into future studies may improve prognostic accuracy and facilitate earlier recognition of clinical deterioration. The clinical applicability of coagulation biomarkers is also noteworthy. INR and fibrinogen, which are rapidly obtainable in ICU settings, show potential for bedside risk stratification. INR may help identify patients with impaired coagulation reserve, while fibrinogen can complement existing severity assessments by reflecting the interaction between inflammation and compensatory coagulation responses. Incorporating these markers with SOFA or other clinical scores may enhance early prognostic evaluation. However, prospective studies are still needed to determine whether their integration into clinical pathways can improve decision-making and outcomes.

This study has several limitations. First, the number of included studies was relatively small, and some indicators such as APTT, PT, and INR were represented by only two studies, which lowers statistical power and reduces confidence in the pooled estimates. Second, some studies lacked complete raw data or only provided graphical results, potentially affecting data-extraction accuracy. Third, heterogeneity in clinical assessments, interventions, and outcome definitions limited comparability and generalizability. Fourth, potential publication bias may exist, since studies with non-significant or negative results are less likely to be published, possibly inflating reported associations. In addition, we focused on individual coagulation parameters without incorporating composite coagulation scoring systems, and subgroup analyses were not possible due to limited data. Future research should include larger, high-quality prospective studies to validate these findings.

Despite these limitations, this meta-analysis has several notable strengths. It provides a systematic synthesis of multiple coagulation-related indices using contemporary evidence and highlights the distinct prognostic contributions of each marker. The findings underscore the potential value of integrating coagulation parameters into sepsis risk assessment and point to promising avenues for clinical application. Future investigations should prioritize large-scale prospective cohorts, standardized measurement protocols, and dynamic monitoring frameworks to assess temporal biomarker trajectories. Moreover, combining coagulation markers with composite clinical scores or machine-learning–based predictive models may help refine individualized risk stratification and support precision management strategies in sepsis.

Statements

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author contributions

CL: Conceptualization, Methodology, Validation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. WH: Data curation, Investigation, Software, Validation, Writing – original draft. XH: Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Writing – original draft. HL: Data curation, Investigation, Methodology, Software, Validation, Writing – original draft. XQ: Conceptualization, Project administration, Resources, Supervision, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declared that financial support was received for this work and/or its publication. This research was funded by the 2023 No. 945 Hospital Management Research Project.

Conflict of interest

The author(s) declared that this work was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declared that generative AI was not used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1.

Stanski NL Wong HR . Prognostic and predictive enrichment in sepsis.Nat Rev Nephrol. (2020) 16:20–31. 10.1038/s41581-019-0199-3

2.

van der Poll T van de Veerdonk FL Scicluna BP Netea MG . The immunopathology of sepsis and potential therapeutic targets.Nat Rev Immunol. (2017) 17:407–20. 10.1038/nri.2017.36

3.

Amaral A Opal SM Vincent JL . Coagulation in sepsis.Intensive Care Med. (2004) 30:1032–40. 10.1007/s00134-004-2291-8

4.

Iba T Levy JH Warkentin TE Thachil J van der Poll T Levi M et al Diagnosis and management of sepsis-induced coagulopathy and disseminated intravascular coagulation. J Thromb Haemost. (2019) 17:1989–94. 10.1111/jth.14578

5.

Kaplan KL . Coagulation activation in sepsis.Crit Care Med. (2000) 28:585–6. 10.1097/00003246-200002000-00057

6.

Iba T Levy JH Wada H Thachil J Warkentin TE Levi M et al Differential diagnoses for sepsis-induced disseminated intravascular coagulation: communication from the SSC of the ISTH. J Thromb Haemost. (2019) 17:415–9. 10.1111/jth.14354

7.

Levi M Schultz MJ . What do sepsis-induced coagulation test result abnormalities mean to intensivists?Intensive Care Med. (2017) 43:581–3. 10.1007/s00134-017-4725-0

8.

Shankar-Hari M Phillips GS Levy ML Seymour CW Liu VX Deutschman CS et al Developing a new definition and assessing new clinical criteria for septic shock: for the Third International consensus definitions for sepsis and septic shock (Sepsis-3). JAMA. (2016) 315:775–87. 10.1001/jama.2016.0289

9.

Zafar A Naeem F Khalid MZ Awan S Riaz MM Mahmood SBZ . Comparison of five different disseminated intravascular coagulation criteria in predicting mortality in patients with sepsis.PLoS One. (2024) 19:e0295050. 10.1371/journal.pone.0295050

10.

Pierrakos C Velissaris D Bisdorff M Marshall JC Vincent JL . Biomarkers of sepsis: time for a reappraisal.Crit Care. (2020) 24:287. 10.1186/s13054-020-02993-5

11.

Bui-Thi HD Gia KT Le Minh K . Coagulation profiles in patients with sepsis/septic shock identify mixed hypo-hypercoagulation patterns based on rotational thromboelastometry: a prospective observational study.Thromb Res. (2023) 227:51–9. 10.1016/j.thromres.2023.05.010

12.

Czempik PF Herzyk J Wilczek D Krzych ŁJ . Hematologic system dysregulation in critically Ill septic patients with anemia-a retrospective cohort study.Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2022) 19:6626. 10.3390/ijerph19116626

13.

Fu S Yu W Fu Q Xu Z Zhang S Liang TB . Prognostic value of APTT combined with fibrinogen and creatinine in predicting 28-Day mortality in patients with septic shock caused by acute enteric perforation.BMC Surg. (2023) 23:274. 10.1186/s12893-023-02165-6

14.

Iba T Arakawa M Ohchi Y Arai T Sato K Wada H et al Prediction of early death in patients with sepsis-associated coagulation disorder treated with antithrombin supplementation. Clin Appl Thromb Hemost. (2018) 24(9_suppl):145S–9S. 10.1177/1076029618797474

15.

Lemiale V Mabrouki A Miry L Mokart D Pène F Kouatchet A et al Sepsis-associated coagulopathy in onco-hematology patients presenting with thrombocytopenia: a multicentric observational study. Leuk Lymphoma. (2023) 64:197–204. 10.1080/10428194.2022.2136971

16.

Levi M Vincent JL Tanaka K Radford AH Kayanoki T Fineberg DA et al Effect of a recombinant human soluble thrombomodulin on baseline coagulation biomarker levels and mortality outcome in patients with sepsis-associated coagulopathy. Crit Care Med. (2020) 48:1140–7. 10.1097/CCM.0000000000004426

17.

Liu J Bai C Li B Shan A Shi F Yao C et al Mortality prediction using a novel combination of biomarkers in the first day of sepsis in intensive care units. Sci Rep. (2021) 11:1275. 10.1038/s41598-020-79843-5

18.

Lorente L Martín MM Ortiz-López R Pérez-Cejas A Gómez-Bernal F González-Mesa A et al Association between blood caspase-9 concentrations and septic patient prognosis. Wien Klin Wochenschr. (2023) 135:75–9. 10.1007/s00508-022-02059-2

19.

Semeraro F Ammollo CT Caironi P Masson S Latini R Panigada M et al D-dimer corrected for thrombin and plasmin generation is a strong predictor of mortality in patients with sepsis. Blood Transfus. (2020) 18:304–11. 10.2450/2019.0175-19

20.

Cohen J . The immunopathogenesis of sepsis.Nature. (2002) 420:885–91. 10.1038/nature01326

21.

Bajaj SP Joist JH . New insights into how blood clots: implications for the use of APTT and PT as coagulation screening tests and in monitoring of anticoagulant therapy.Semin Thromb Hemost. (1999) 25:407–18. 10.1055/s-2007-994943

22.

Sarıdaş A Çetinkaya R . The prognostic value of the CALLY index in sepsis: a composite biomarker reflecting inflammation, nutrition, and immunity.Diagnostics. (2025) 15:1026. 10.3390/diagnostics15081026

23.

Dempfle CE Borggrefe M . The hidden sepsis marker: aptt waveform analysis.Thromb Haemost. (2008) 100:9–10. 10.1160/TH08-05-0308

24.

Tripodi A Breukink-Engbers WG van den Besselaar AM . Oral anticoagulant monitoring by laboratory or near-patient testing: What a clinician should be aware of.Semin Vasc Med. (2003) 3:243–54. 10.1055/s-2003-44460

25.

Woźnica EA Inglot M Woźnica RK Łysenko L . Liver dysfunction in sepsis.Adv Clin Exp Med. (2018) 27:547–51. 10.17219/acem/68363

26.

Zhang J Xue M Chen Y Liu C Kuang Z Mu S et al Identification of soluble thrombomodulin and tissue plasminogen activator-inhibitor complex as biomarkers for prognosis and early evaluation of septic shock and sepsis-induced disseminated intravascular coagulation. Ann Palliat Med. (2021) 10:10170–84. 10.21037/apm-21-2222

27.

Semeraro F Ammollo CT Caironi P Masson S Latini R Panigada M et al Low D-dimer levels in sepsis: good or bad? Thromb Res. (2019) 174:13–5. 10.1016/j.thromres.2018.12.003

28.

Han YQ Yan L Zhang L Ouyang PH Li P Lippi G et al Performance of D-dimer for predicting sepsis mortality in the intensive care unit. Biochem Med. (2021) 31:020709. 10.11613/BM.2021.020709

29.

Davalos D Akassoglou K . Fibrinogen as a key regulator of inflammation in disease.Semin Immunopathol. (2012) 34(1):43–62. 10.1007/s00281-011-0290-8

30.

Wada T Tanigawa T Shiko Y Yamakawa K Gando S . Disseminated intravascular coagulation resolution as a surrogate outcome for mortality in sepsis-associated disseminated intravascular coagulation.Thromb Res. (2025) 255:109485. 10.1016/j.thromres.2025.109485

31.

Tong T Guo Y Wang Q Sun X Sun Z Yang Y et al Development and validation of a nomogram to predict survival in septic patients with heart failure in the intensive care unit. Sci Rep. (2025) 15:909. 10.1038/s41598-025-85596-w

Summary

Keywords

sepsis, meta-analysis, prognosis assessment, coagulation function, biomarker

Citation

Li C, Huang W, Han X, Li H and Qin X (2025) The association between coagulation function and prognosis in patients with sepsis: a meta-analysis of predictive performance introduction. Front. Med. 12:1706082. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2025.1706082

Received

15 September 2025

Revised

19 November 2025

Accepted

04 December 2025

Published

18 December 2025

Volume

12 - 2025

Edited by

Ali Sarıdaş, Prof. Dr. Cemil Tascioglu City Hospital, Türkiye

Reviewed by

Ikhwan Rinaldi, RSUPN Dr. Cipto Mangunkusumo, Indonesia

Mustafa Can Guler, Atatürk University, Türkiye

Updates

Copyright

© 2025 Li, Huang, Han, Li and Qin.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Xianyun Qin, sweetnight1983@163.com

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.