Abstract

Objective:

Desflurane is the most commonly suitable volatile anesthetic for elderly patients due to its low blood solubility, suggesting faster induction and awakening time. This study compared the safety and efficacy of desflurane versus sevoflurane in terms of postoperative cognitive function and early recovery quality in elderly orthopedic patients.

Methods:

Eighty elderly patients undergoing orthopedic surgery were included in this prospective, randomized controlled trial. After preoxygenation with a 5 L/min fresh oxygen flow via a facial mask for 5 min, anesthesia was induced using 0.2 μg/kg sufentanil, 1–2 mg/kg etomidate, and 0.2 mg/kg cisatracurium. General anesthesia was maintained through continuous infusion of remifentanil (0.05–0.20 μg/kg/min) and a sevoflurane expiratory concentration of 1–2% or desflurane 2–5%, in combination with air containing 40% oxygen to maintain bispectral index (BIS) values 40–60. Data collected included hemodynamic parameters, time to eye-opening, extubation, following commands, orientation, post-anesthesia care unit (PACU) length of stay, opioid consumption, patient and surgeon satisfaction scores, number of patients willing to repeat surgery with the same anesthesia regimen, and adverse events. Additionally, white blood cell counts, percentages of neutrophils and lymphocytes, and troponin I levels were recorded at baseline and 24 h post-surgery.

Results:

The Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) scores were lower at 1 h post-surgery in the desflurane group (D group) than in the sevoflurane group (S group), although the difference was not clinically significant (p > 0.05). Over 70% of patients in both groups returned to baseline MMSE levels 24 h postoperatively. There were no significant differences in MMSE scores at baseline, 6, 24, or 48 h post-surgery between the groups (p > 0.05). Patients in the D group recovered significantly faster, indicated by shorter times to eye-opening, extubation, following commands, and reduced PACU length of stay (p < 0.05). Patient and surgeon satisfaction scores and number of patients willing to repeat surgery with the same sedation regimen were significantly higher in the D group (p < 0.05), whereas white blood cell counts and percentage of neutrophils were significantly lower 24 h post-surgery in the D group (p < 0.05). No significant differences were observed in patient demographics, orientation times, opioid consumption, hemodynamics, adverse events, lymphocyte percentages, or troponin I levels between the groups (p > 0.05).

Conclusion:

Desflurane was not associated with reduced MMSE scores or postoperative respiratory complications. However, it demonstrated faster recovery times and higher patient satisfaction scores than sevoflurane.

Clinical trial registration:

ChiCTR2400093852.

Introduction

With advancements in medical techniques and economic growth, life expectancy has increased, leading to a rise in the number of patients aged ≥65 years undergoing general anesthesia (1). Elderly patients have a lower basal metabolic rate, diminished digestive function, muscle atrophy, poor adaptive capacity, reduced immunity, and degeneration of vital organs, neurotransmitters, and neurons (2). Consequently, they face an increased risk of postoperative delirium, which occurs in 10–60% of cases despite advancements in surgical and anesthetic techniques (3).

Delirium, a benign temporal disorientation occurring during the transition from anesthesia to wakefulness, typically resolves within minutes or hours. Increasing age is a significant risk factor for cognitive decline and prolonged recovery time from anesthesia (4). Postoperative cognitive decline or dysfunction (POCD), which occurs at least twice as frequently in individuals aged >60 years than in middle-aged or younger groups, is associated with prolonged hospital stays, higher treatment costs, and increased mortality 1 year after surgery (5). Previous studies have suggested that delirium may predict worsening cognitive function within the first year after surgery in patients aged >60 years (6). Additionally, the progressive loss of organ reserve in elderly individuals, coupled with coexisting diseases, can substantially modify pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic responses to drugs, significantly affecting the quality of recovery (7). Theoretically, the use of shorter-acting anesthetics and analgesic drugs may reduce postoperative cognitive impairment and confusion in elderly patients. Therefore, selecting appropriate anesthetic drugs is crucial for optimizing postoperative recovery in this population.

The use of volatile anesthetics that are rapidly eliminated with minimal metabolic breakdown may help reduce postoperative delirium and cognitive dysfunction in elderly surgical patients (8). Sevoflurane and desflurane are among the most commonly used volatile anesthetics for maintaining anesthesia. Both agents have low blood-gas partition coefficients (0.42 vs. 0.65), allowing for shorter induction times, rapid emergence, and early recovery of airway reflexes than other soluble inhaled anesthetics (9). Recent studies have indicated that desflurane has the lowest blood solubility, resulting in the fastest induction and awakening. Furthermore, volatile anesthetics may be advantageous for elderly patients with obstructive respiratory dysfunction due to their bronchodilating properties (10). This prospective, randomized controlled trial was designed to compare the safety and efficacy of desflurane versus sevoflurane in terms of postoperative cognitive function and early recovery quality in elderly orthopedic patients.

Methods

Study design

This study was a randomized, parallel, double-blind controlled trial. Informed consent was obtained in writing from all participating patients and their legal representatives. The study was conducted between May and September 2024 and was approved by the Ethics Committee of The Liaocheng Infectious Disease Hospital. It was also registered with the Chinese Clinical Trial Registry (ChiCTR2400093852) and adhered to the Helsinki Declaration.

The inclusion criteria were patients aged between 65 and 75 years undergoing orthopedic surgery. Patients were excluded if they had clinically significant cardiovascular, respiratory, hepatic, renal, neurological, psychiatric, or metabolic diseases; a Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) score ≤24; American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) grades >III; a history of long-term use of narcotic analgesics, sedatives, antidepressants, or alcohol; or if they had participated in other clinical trials within the last 3 months. Patients with body weight exceeding 150% of their ideal body weight were also excluded (11).

An independent investigator generated a random assignment sequence using randomization software and assigned 80 patients to one of two groups. To ensure consistency, the same research assistant—trained in the use of the Confusion Assessment Method (CAM) and MMSE—evaluated all patients and performed chart reviews. While the anesthesiologist could not be blinded due to differences in administration techniques for the two volatile anesthetics, the surgeons, nurses, patients, and other investigators remained blinded to group assignments until the study was completed.

Anesthesia

No perioperative sedation was administered. Upon arrival in the operating room, a venous catheter was inserted, and lactated Ringer’s solution was infused at 5 mL/kg before anesthesia and then adjusted to 5 mL/kg/h during surgery. Routine monitoring included peripheral oxygen saturation (SpO2), electrocardiography (ECG), noninvasive blood pressure, and bispectral index (BIS, E-8000, Beijing Thinking High Medical Technology Co., Ltd., China). End-tidal carbon dioxide tension (PetCO2) and concentrations of desflurane and sevoflurane were measured using a gas analyzer (Carestation 650 A1, 3,030 Ohmeda Dr. Madison, USA). After preoxygenation at a fresh oxygen flow of 5 L/min via facial mask for 5 min, anesthesia was induced with 0.2 μg/kg sufentanil, 0.1–0.2 mg/kg etomidate, and 0.2 mg/kg cisatracurium. General anesthesia was maintained using continuous infusion of remifentanil (0.05–0.20 μg/kg/min) and sevoflurane (1–2% expiratory concentration) or desflurane (2–5%) to maintain BIS levels 40–60. Mechanical ventilation was initiated with an inspired oxygen concentration of 40%, a fresh gas flow rate of 2 L/min, a tidal volume of 6–8 mL/kg, a respiratory rate of 12 breaths/min, and a positive end-expiratory pressure of 5 cmH2O (if there were no contraindications) to maintain PetCO2 between 35 and 40 mmHg. IV boluses of sufentanil and cisatracurium were administered at the discretion of the attending anesthesiologist. At the end of surgery, residual neuromuscular blockade was reversed using 0.02 mg/kg atropine and 0.05 mg/kg neostigmine. Extubation was performed when the following criteria were met: respiratory rate ≥8/min, tidal volume ≥5 mL/kg, hemodynamic stability, recovery of cough reflex, and SpO2 ≥ 95% (12). All patients were transferred to the post-anesthesia care unit (PACU) with oxygen flow at 5 L/min and were returned to the ward if the modified Aldrete score was ≥9.

Outcomes

The primary safety outcome was cognitive impairment measured using the MMSE (a scale from 0 to 30, with lower scores indicating worse impairment) at baseline and at 1, 6, 24, and 48 h post-surgery. A decrease in MMSE >2 points was considered clinically significant (13). Other safety outcomes included PACU length of stay; patient and surgeon satisfaction scores (1 = dissatisfied, 5 = satisfied); adverse events (e.g., respiratory infection, respiratory failure, pleural effusion, atelectasis, pneumothorax, bronchospasm, aspiration pneumonitis); and the number of patients willing to repeat surgery with the same sedation regimen. The incidence of postoperative delirium was assessed using CAM (assesses four criteria: acute onset/fluctuating course, inattention, disorganized thinking, and altered level of consciousness) at 6 and 24 h post-surgery. Delirium is considered present when both the first two criteria and either the third or fourth criteria are present at any of the postoperative assessment points (14). The efficacy outcomes were time to eye-opening, extubation, following commands, and orientation; hemodynamic measurements recorded at various time points (T0: arrival at the operating room; T1: before anesthesia induction; T2: before surgery; T3: 5 min after surgery start; T4: 10 min after surgery start; T5: surgery end; T6: arrival in PACU; T7: 5 min in PACU; T8: 10 min in PACU; T9: pre-discharge from PACU); opioid consumption. Additional measures included white blood cell counts, percentages of neutrophils and lymphocytes, and troponin I levels recorded at baseline and 24 h post-surgery.

Statistical analysis

Sample size calculations, based on an intergroup difference of our pre-experiment in MMSE decrease at 1 h post-surgery (25.22 ± 1.74 vs. 26.31 ± 1.39, power = 0.8, α = 0.05), revealed a required sample size of 36 patients per group. To account for a 10% dropout rate, 80 patients were recruited.

Statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism 8.0 and SPSS 24.0 (SPSS, Chicago, IL, USA). The Shapiro–Wilk test assessed normality, while Levene’s test evaluated homogeneity of variances. Continuous data were presented as means ± standard deviations or medians and interquartile ranges and analyzed using the Student’s t-test or Mann–Whitney U-test. Repeated measures analysis of variance assessed hemodynamic variables, MMSE, and CAM scores. Qualitative data were reported as numbers and frequencies and analyzed using χ2 or Fisher’s exact tests. A p-value <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Patient demographic characteristics

A total of 145 elderly patients undergoing orthopedic surgery were recruited between May and September 2024. Sixty-five patients were excluded for the following reasons: clinically significant cardiovascular, respiratory, hepatic, renal, neurological, psychiatric, or metabolic disease (n = 31); MMSE score ≤24 (n = 8); ASA grade >III (n = 6); history of long-term use of narcotic analgesics, sedatives, antidepressants, or alcohol (n = 12); participation in other clinical trials within the past 3 months (n = 2); or weight exceeding 150% of their ideal body weight (n = 6). As a result, 80 patients were equally divided into the D and S groups (n = 40 each; Figure 1). There were no significant differences in patient demographic characteristics between the two groups (p > 0.05; Table 1).

Figure 1

Patient flowchart with CONSORT guidelines.

Table 1

| Variable | Group D (n = 40) | Group S (n = 40) | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 68.98 ± 2.93 | 68.95 ± 2.61 | 0.968 |

| Gender (male/female) History of smoking, n (%) |

24/16 17 (42.50%) |

23/17 25 (62.50%) |

0.820 0.073 |

| Education (primary school/middle school/high school and above) | 13/19/8 | 15/19/6 | 0.807 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 25.67 ± 1.87 | 25.39 ± 1.81 | 0.491 |

| ASA I/II/III (n) | 10/23/7 | 7/23/10 | 0.589 |

| Comorbidity, n (%) | |||

| Hypertension | 17 (42.50%) | 22 (55.00%) | 0.962 |

| Diabetes | 15 (37.50%) | 20 (50.00%) | |

| Coronary heart disease | 15 (37.50%) | 22 (55.00%) | |

Demographics and baseline data between the two groups.

Variables presented as mean ± SD or number of patients n (%). BMI, Body Mass Index; ASA, American Society of Anesthesiology.

Primary outcome

The MMSE scores were lower in the D group 1 h post-surgery than those in the S group, although the difference did not reach clinical significance (p > 0.05; Table 2). A transient decline in MMSE was observed in 75% of patients in the D group and 67.5% in the S group 1 h post-surgery. More than 70% of patients in both groups returned to baseline MMSE levels by 24 h postoperatively. However, there were no significant differences in MMSE scores between the two groups at baseline or at 6, 24, and 48 h after surgery (p > 0.05; Table 2).

Table 2

| Variable | Group D (n = 40) | Group S (n = 40) | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | 27.03 ± 1.14 | 26.88 ± 1.14 | 0.558 |

| 1 h | 25.75 ± 0.84 | 26.00 ± 0.85 | 0.059 |

| 6 h | 26.68 ± 0.92 | 26.55 ± 0.88 | 0.535 |

| 24 h | 26.88 ± 1.02 | 26.70 ± 0.85 | 0.407 |

| 48 h | 27.15 ± 1.03 | 27.05 ± 1.04 | 0.666 |

Comparison of MMSE between the two groups.

Variables presented as mean ± SD.

Other outcomes

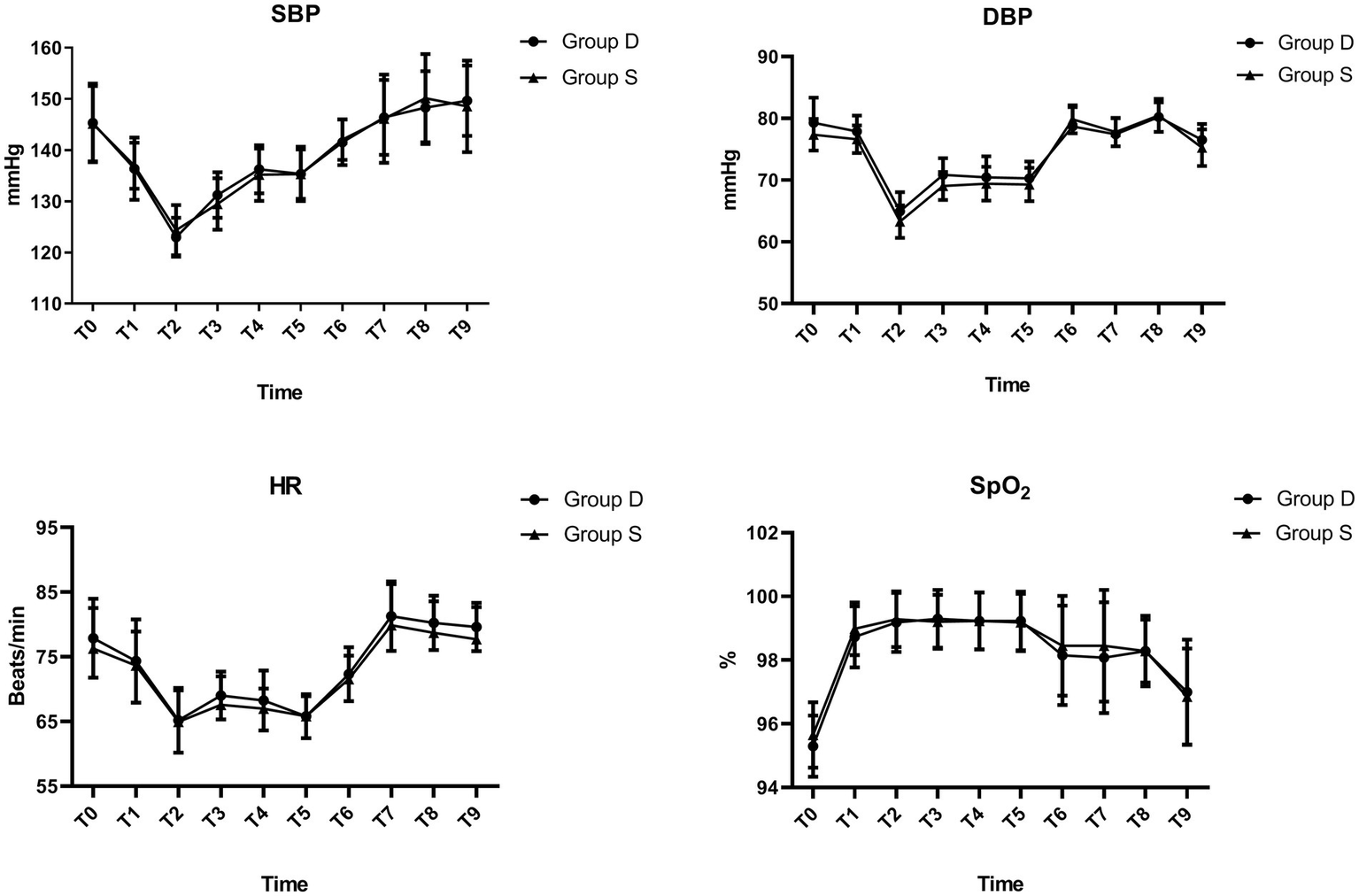

Patients in the D group recovered significantly faster in terms of time to eye-opening, extubation, following commands, and length of stay in the PACU (p < 0.05; Table 3). However, no differences were observed between the two groups in time to orientation, perioperative opioid consumption, or hemodynamic variables (p > 0.05; Table 3, Figure 2). Compared with the S group, patients in the D group reported significantly higher satisfaction scores and a greater willingness to repeat surgery with the same sedation regimen (p < 0.05; Table 3).

Table 3

| Variable | Group D (n = 40) | Group S (n = 40) | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Time metrics | |||

| Time to open eyes (min) | 4.95 ± 1.48 | 7.08 ± 1.25* | 0.001 |

| Time to extubation (min) | 7.15 ± 1.10 | 9.13 ± 1.22* | 0.001 |

| Time to orientation(min) | 10.13 ± 1.29 | 10.50 ± 1.24 | 0.188 |

| Time to follow commands (min) | 10.80 ± 1.16 | 11.45 ± 1.18* | 0.015 |

| Length of stay in the PACU (min) | 17.20 ± 1.57 | 18.23 ± 1.53* | 0.004 |

| Consumption of sufentanil (μg) | 16.39 ± 2.32 | 16.35 ± 2.14 | 0.936 |

| Consumption of remifentanil (μg) | 547.07 ± 92.82 | 573.25 ± 88.40 | 0.200 |

| Consumption of etomidate (mg) | 11.03 ± 2.15 | 10.65 ± 2.32 | 0.440 |

| Consumption of cisatracurium (mg) | 14.60 ± 1.13 | 14.49 ± 1.18 | 0.686 |

| Consumption of desflurane (MAC) | 3.86 ± 0.50 | — | |

| Consumption of sevoflurane (MAC) | — | 1.69 ± 0.85 | |

| Operative time (min) | 103.98 ± 11.72 | 97.38 ± 18.02 | 0.056 |

| Anesthesia time (min) | 123.80 ± 10.82 | 120.18 ± 11.46 | 0.150 |

| Patient satisfaction scores | 4.25 (4.00–4.75) | 4.00 (3.75–4.75)* | 0.034 |

| Surgeon satisfaction scores | 4.50 (4.00–4.75) | 4.25 (3.75–4.75) | 0.224 |

| Willing to the repeat surgery with the same sedation regimen, n (%) | 36 (90.00%) | 27 (67.50%)* | 0.014 |

Intra- and postoperative parameters between the two groups.

Variables presented as mean ± SD, median (interquartile range) or number of patients n (%). MAC, minimum alveolar concentration; PACU, Post Anesthesia Care Unit. *p < 0.05 vs. Group D.

Figure 2

Hemodynamic changes between the two groups.

There were no significant differences between the two groups in the incidence of postoperative respiratory complications, emergence cough, nausea and vomiting, or postoperative delirium (p > 0.05; Table 4). All observed adverse events were of minor severity (p > 0.05; Table 4).

Table 4

| Variable | Group D (n = 40) | Group S (n = 40) | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Respiratory complications | |||

| Respiratory infection | 6 (15.00%) | 6 (15.00%) | 1.000 |

| Respiratory failure | 2 (5.00%) | 2 (5.00%) | 1.000 |

| Pleural effusion | 4 (10.00%) | 8 (20.00%) | 0.210 |

| Atelectasis | 4 (10.00%) | 5 (12.50%) | 1.000 |

| The incidence of postoperative delirium | |||

| 6 h | 4 (10.00%) | 4 (10.00%) | 1.000 |

| 24 h | 1 (2.50%) | 1 (2.50%) | 1.000 |

| The incidence of nausea and vomiting | 5 (12.50%) | 10 (25.00%) | 0.152 |

| The incidence of emergence cough | 4 (10.00%) | 5 (12.50%) | 1.000 |

| Severity of adverse events | |||

| Grade 1 | 25 (62.50%) | 34 (85.00%) | |

| Grade 2 | 1 (2.50%) | 2 (5.00%) | 1.000 |

| Grade 3 | 0 | 0 | |

| Grade 4 | 0 | 0 | |

Adverse events between the two groups.

Variables presented as number of patients n (%).

White blood cell counts and neutrophil percentages decreased significantly 24 h post-surgery in the D group than in the S group (p < 0.05; Figure 3). However, lymphocyte percentages and troponin I levels were similar between the groups (p > 0.05; Figure 3).

Figure 3

White blood cell counts, percentage of neutrophils and lymphocytes, and troponin I levels preoperatively and 24 h post-surgery.

Discussion

This single-center prospective randomized controlled trial found that the use of desflurane for the maintenance of general anesthesia did not reduce the risk of cognitive impairment compared with sevoflurane. However, desflurane was associated with faster recovery than sevoflurane after general anesthesia in elderly orthopedic patients. Furthermore, patient satisfaction scores and the number of patients willing to undergo surgery with the same sedation regimen were significantly higher in the desflurane group, and white blood cell counts and neutrophil percentages were significantly reduced 24 h post-surgery.

Previous studies have characterized POCD as a condition involving impaired memory and concentration, though its exact pathogenesis remains unclear. The incidence of POCD has been reported to be 25.8% in elderly patients 1 week after surgery and 9.9% 3 months post-surgery (15). It is a multifactorial disorder influenced by patient, surgical, and anesthetic-related factors. General anesthesia, patient predisposition, type of surgery, age, alcohol abuse, low baseline cognition, comorbidities, prolonged preoperative fasting, opioid consumption, intraoperative bleeding, anticholinergic drug load, and excessively deep anesthesia have been considered contribute to the development of POCD (5). In line with previous findings, over 70% of patients in both groups returned to baseline cognitive function within 24 h postoperatively (16).

A previous study has reported that desflurane concentration for maintaining BIS value <50 was 3.58 and 2.75% in middle-aged and elderly patients, respectively, which was lower than that in our study (17). This may be due to the different types of surgeries and anesthesia regimens employed in the two studies. Intraoperative EEG characteristics associated with POCD are more noticeable with sevoflurane than with desflurane (9).

Besides, BIS was lower in patients receiving 1 MAC desflurane than in those receiving 1 MAC sevoflurane, suggesting that provides a deeper level of anesthesia at 1 MAC than sevoflurane (18). However, recent study revealed that intraoperative EEG patterns are associated with POCD development and can be utilized for the early detection of POCD (9). Besides, POCD was less frequent in elderly patients when moderate anesthesia depth was maintained using processed EEG guidance compared with routine care, based on clinical signs and end-tidal anesthetic agent concentration (19). Therefore, in this study, we chose BIS as the monitoring indicator for anesthesia depth and maintained BIS at 40–60 in line with the parameters applied in a previous study (18).

The clinical tools used to measure cognitive function after anesthesia have not been standardized, and the timing of the measurements has varied widely in earlier studies (20). Standard psychometric tests used to measure cognitive ability require a considerable amount of time to administer, which is impractical in the perioperative period. The use of the MMSE to evaluate patients after surgery under general anesthesia has been shown to be both easy and reliable for detecting mild cognitive impairment (21). Moreover, the greater sensitivity of more extensive testing panels is associated with a longer test time, which elderly patients may find challenging to perform in the immediate postoperative period (22). As a result, the MMSE was chosen for use in this study. Different studies have shown a significantly increased risk of developing POCD after desflurane anesthesia in older patients, even though burst suppression duration was shorter under desflurane anesthesia compared to sevoflurane or propofol anesthesia. The main speculation is that the different receptor affinities and induced neurotoxic and inflammatory effects at the cellular level of desflurane may be the underlying cause triggering POCD to a greater extent than propofol or sevoflurane (23, 24). Besides, it decreases CMRO2 and preserves cerebrovascular reactivity (25). MMSE scores were lower in the D group at 1 h after surgery compared with those in the S group; however, this difference was not clinically significant. Additionally, over 70% of patients in both groups returned to baseline levels at 24 h postoperatively.

A previous study has reported that the cause of cognitive decline is associated with the inflammation caused by the stress of surgery (26). However, the white blood cell counts and neutrophil percentages were significantly decreased 24 h post-surgery in the desflurane group, although the percentage of lymphocytes and troponin I levels were similar between the two groups. The results were similar to those of a previous study, which found that patients anesthetized with desflurane had significantly better white blood cell counts and percentage of neutrophils than patients in the sevoflurane group. This is likely because volatile anesthesia could significantly enhance both local and systemic oxidative stress, especially with desflurane (27). Furthermore, the systemic stress response caused by the release of cytokines during anesthesia and surgery may cause changes in brain function and play a role in the development of POCD. Neuroinflammation, characterized by inflammatory imbalance and neuronal damage, is an important mechanism that causes neurocognitive disorders during the perioperative period (28).

Inhalational anesthetics are mainly discharged through the respiratory tract and feature convenient administration, easy control of dosage, and stable hemodynamics. The speed of induction and recovery of inhalation agents depends mainly on the blood solubility of each inhalation anesthetic (29). Sevoflurane and desflurane have been widely used and provide relatively rapid induction and emergence due to their low blood solubilities (9). Consistent with the results of a previous study, recovery was significantly faster in the D group. The reason may be that desflurane has the lowest intra-hepatic metabolic rate among the inhalational anesthetics and extremely low toxicity to the liver and kidney. One previous study reported that desflurane increases sympathetic nerve activity, which might also contribute to rapid emergence from general anesthesia (30). Compared with the results of other studies, PACU length of stay was significantly shortened. As a result, the service fees were also reduced, which has a significant economic impact (31). A previous retrospective study indicated that male sex and obstructive respiratory function were factors that contributed to extubation time after general anesthesia with desflurane. In contrast, age, operation time, and BMI were not risk factors for prolonged extubation (32). However, there were no significant differences in patient demographic characteristics between the two groups in this study.

Postoperative respiratory complications are an important quality indicator associated with poor patient outcomes, longer hospital stays, and increased costs. Volatile anesthetics impair hypoxic and hypercarbic ventilatory responses and neuromuscular transmission. They also impair coordination between breathing and swallowing, increasing aspiration risk (33). Consistent with the results of a previous study, desflurane was not associated with reduced postoperative respiratory complications when compared with sevoflurane (34). The postoperative respiratory complications were lower in our study, which aligns with the results of a recent study that reported the use of higher volatile agents is associated with a reduction in risk of postoperative pulmonary complications and mortality compared with patients with total intravenous anesthesia. The reason may be that the immunomodulatory effects of inhalational anesthetics decrease inflammation and attenuate acute lung injury by suppressing inflammatory responses through modulation of alveolar macrophage responses, maintenance of neutrophil recruitment, and GABAA-receptor–mediated anti-inflammatory effects in lung epithelial cells (35).

A previous study reported that desflurane has insurmountable shortcomings such as high cost, and an increased risk of coughing, breath holding, laryngospasm, and tachycardia, especially when the concentrations exceed 1 MAC (36). However, the incidence of emergence cough was significantly reduced compared with the results of other studies. The reason may be partly due to the higher consumption of remifentanil in our study, even though there was no need to adjust the remifentanil Ce to prevent emergence cough between sevoflurane and desflurane anesthesia in elderly female patients (37). However, no increase in the incidence of adverse reactions such as respiratory depression, delayed emergence, nausea, and vomiting was recorded. A previous study reported that volatile anesthetics were potent greenhouse gases and a major contributor to environmental waste generated from the operating room, especially desflurane, which remains in the atmosphere for nearly 14 years and is known to have a global warming potential (GWP) that is 20-fold greater than sevoflurane (38). All of these defects limit the clinical application of desflurane. Moreover, volatile anesthetics can increase post-extubation shivering compared to propofol-based anesthesia, and some show a dose-dependent increase (39). In summary, clinical efficiency must be balanced with environmental responsibility. As stated in the previous investigation, the shift in practice by anaesthetists away from anaesthetic gases with high global warming potential toward lower emission techniques (e.g., total intravenous anaesthesia) could result in significant carbon savings for the health system (40).

This study has several limitations. First, in addition to MMSE, more sensitive tools such as the Saskatoon Delirium Checklist, Digit-Symbol Substitution Test, and Geriatric Mental State Examination have all been used to evaluate cognitive function in elderly patients. These tests assess recovery of consciousness, perception, orientation, coherence, memory, and motor activity (1). The use of a more sensitive psychological test of cognitive dysfunction associated with a longer test time might have demonstrated more prolonged impairment of cognitive performance after surgery and strengthen the clinical interpretation of the cognitive data. Second, the results of adverse reactions in this study were not specifically powered, and a large-volume study is needed to evaluate these values. Third, this study design specifies a single-center trial involving patients aged 65 to 75 years from one hospital. Such restriction limits the representativeness of the population. Future multicenter trials or inclusion of a broader age range and diverse ethnic or clinical backgrounds are needed to enhance the external validity of the findings. Fourth, Considering the small number of patients included in this study and in order to reduce statistical bias, we did not perform a post hoc subgroup analysis by sex though physiological responses to anesthetics may differ between men and women. Besides, multivariate regression or ANCOVA models are needed to verify whether the observed differences between anesthetics remain significant after adjusting other clinical covariates such as surgery duration, comorbidities, opioid dose, or intraoperative hemodynamics. Finally, we only performed cognitive testing at baseline, 1, 6, 24, and 48 h post-surgery, which could have missed cases within 48 h post-surgery due to the present time points or late cases beyond 48 h.

In conclusion, desflurane was not associated with reduced MMSE scores or postoperative respiratory complications, though recovery was significantly faster, and patient satisfaction scores were higher compared with sevoflurane. As a result, we should adhere to individualized treatment based on the advantages and disadvantages of each drug in clinical applications. Further research is needed to explore the relationship between anesthetic selection and long-term cognitive or economic outcomes.

Statements

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by the ethics committee of the Liaocheng Infectious Disease Hospital. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

RD: Formal analysis, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. CS: Data curation, Investigation, Methodology, Writing – review & editing. JL: Data curation, Project administration, Validation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. XJ: Formal Analysis, Funding acquisition, Supervision, Writing – review & editing. CR: Methodology, Writing – original draft. QZ: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Methodology, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. This study was supported by Shandong Province Medical and Health Technology Project (no. 202318001647).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The authors declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Abbreviations

ASA, American Society of Anesthesiologists; BIS, Bispectral index; CAM, Confusion Assessment Method; GWP, Global warming potential; MMSE, Mini-Mental State Examination; PACU, Post-anesthesia care unit; POCD, Postoperative cognitive decline or dysfunction.

References

1.

Bhushan S Huang X Duan Y Xiao Z . The impact of regional versus general anesthesia on postoperative neurocognitive outcomes in elderly patients undergoing hip fracture surgery: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Surg. (2022) 105:106854. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2022.106854

2.

Ocagli H Lanera C Azzolina D Piras G Soltanmohammadi R Gallipoli S et al . Resting energy expenditure in the elderly: systematic review and comparison of equations in an experimental population. Nutrients. (2021) 13:458. doi: 10.3390/nu13020458

3.

Li X Wu J Lan H Shan W Xu Q Dong X et al . Effect of intraoperative intravenous lidocaine on postoperative delirium in elderly patients with hip fracture: a prospective randomized controlled trial. Drug Des Devel Ther. (2023) 17:3749–56. doi: 10.2147/DDDT.S437599

4.

Zhou Q Zhou X Zhang Y Hou M Tian X Yang H et al . Predictors of postoperative delirium in elderly patients following total hip and knee arthroplasty: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. (2021) 22:945. doi: 10.1186/s12891-021-04825-1

5.

Arefayne NR Berhe YW van Zundert AA . Incidence and factors related to prolonged postoperative cognitive decline (POCD) in elderly patients following surgery and Anaesthesia: a systematic review. J Multidiscip Healthc. (2023) 16:3405–13. doi: 10.2147/JMDH.S431168

6.

Huang H Li H Zhang X Shi G Xu M Ru X et al . Association of postoperative delirium with cognitive outcomes: a meta-analysis. J Clin Anesth. (2021) 75:110496. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinane.2021.110496

7.

Araújo AM Machado H de Pinho PG Soares-da-Silva P Falcão A . Population pharmacokinetic-Pharmacodynamic modeling for Propofol anesthesia guided by the Bispectral index (BIS). J Clin Pharmacol. (2020) 60:617–28. doi: 10.1002/jcph.1560

8.

Han J Ryu JH Jeon YT Koo CH . Comparison of volatile anesthetics versus Propofol on postoperative cognitive function after cardiac surgery: a systematic review and Meta-analysis. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth. (2024) 38:141–7. doi: 10.1053/j.jvca.2023.09.038

9.

Kim YS Kim J Park S Kim KN Ha Y Yi S et al . Differential effects of sevoflurane and desflurane on frontal intraoperative electroencephalogram dynamics associated with postoperative delirium. J Clin Anesth. (2024) 93:111368. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinane.2023.111368

10.

Chen WS Chiang MH Hung KC Lin KL Wang CH Poon YY et al . Adverse respiratory events with sevoflurane compared with desflurane in ambulatory surgery: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Anaesthesiol. (2020) 37:1093–104. doi: 10.1097/EJA.0000000000001375

11.

Peterson CM Thomas DM Blackburn GL Heymsfield SB . Universal equation for estimating ideal body weight and body weight at any BMI. Am J Clin Nutr. (2016) 103:1197–203. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.115.121178

12.

Jia D Wang H Wang Q Li W Lan X Zhou H et al . Rapid shallow breathing index predicting extubation outcomes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Intensive Crit Care Nurs. (2024) 80:103551. doi: 10.1016/j.iccn.2023.103551

13.

Satoh T Sawada Y Saba H Kitamoto H Kato Y Shiozuka Y et al . Assessment of mild cognitive impairment using cog Evo: a computerized cognitive function assessment tool. J Prim Care Community Health. (2024) 15:21501319241239228. doi: 10.1177/21501319241239228

14.

Zhang Y Diao D Zhang H Gao Y . Validity and predictability of the confusion assessment method for the intensive care unit for delirium among critically ill patients in the intensive care unit: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Nurs Crit Care. (2024) 29:1204–14. doi: 10.1111/nicc.12982

15.

Verdonk F Cambriel A Hedou J Ganio E Bellan G Gaudilliere D et al . An immune signature of postoperative cognitive decline: a prospective cohort study. Int J Surg. (2024) 110:7749–62. doi: 10.1097/JS9.0000000000002118

16.

Chen G Zhou Y Shi Q Zhou H . Comparison of early recovery and cognitive function after desflurane and sevoflurane anaesthesia in elderly patients: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J Int Med Res. (2015) 43:619–28. doi: 10.1177/0300060515591064

17.

Kanazawa S Oda Y Maeda C Okutani R . Age-dependent decrease in desflurane concentration for maintaining bispectral index below 50. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. (2016) 60:177–82. doi: 10.1111/aas.12642

18.

Kanazawa S Oda Y Maeda C Okutani R . Electroencephalographic effect of age-adjusted 1 MAC desflurane and sevoflurane in young, middle-aged, and elderly patients. J Anesth. (2017) 31:744–50. doi: 10.1007/s00540-017-2391-6

19.

Xue S Xu AX Liu H Zhang Y . Electroencephalography monitoring for preventing postoperative delirium and postoperative cognitive decline in patients undergoing cardiothoracic surgery: a Meta-analysis. Rev Cardiovasc Med. (2024) 25:126. doi: 10.31083/j.rcm2504126

20.

Vide S Gambús PL . Tools to screen and measure cognitive impairment after surgery and anesthesia. Presse Med. (2018) 47:e65–72. doi: 10.1016/j.lpm.2018.03.010

21.

Zhang J Jia D Li W Li X Ma Q Chen X . General anesthesia with S-ketamine improves the early recovery and cognitive function in patients undergoing modified radical mastectomy: a prospective randomized controlled trial. BMC Anesthesiol. (2023) 23:214. doi: 10.1186/s12871-023-02161-6

22.

Yang X Huang X Li M Jiang Y Zhang H . Identification of individuals at risk for postoperative cognitive dysfunction (POCD). Ther Adv Neurol Disord. (2022) 15:17562864221114356. doi: 10.1177/17562864221114356

23.

Koch S Blankertz B Windmann V Spies C Radtke FM Röhr V . Desflurane is risk factor for postoperative delirium in older patients' independent from intraoperative burst suppression duration. Front Aging Neurosci. (2023) 15:1067268. doi: 10.3389/fnagi.2023.1067268

24.

Varsha AV Unnikrishnan KP Saravana Babu MS Raman SP Koshy T . Comparison of Propofol-based Total intravenous anesthesia versus volatile anesthesia with sevoflurane for postoperative delirium in adult coronary artery bypass grafting surgery: a prospective randomized single-blinded study. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth. (2024) 38:1932–40. doi: 10.1053/j.jvca.2024.05.027

25.

Mahajan S Sharma T Panda NB Chauhan R Joys S Sharma N et al . Comparison of propofol and desflurane for postoperative neurocognitive function in patients with aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage: a prospective randomized trial. Surg Neurol Int. (2024) 15:84. doi: 10.25259/SNI_788_2023

26.

Quan C Chen J Luo Y Zhou L He X Liao Y et al . BIS-guided deep anesthesia decreases short-term postoperative cognitive dysfunction and peripheral inflammation in elderly patients undergoing abdominal surgery. Brain Behav. (2019) 9:e01238. doi: 10.1002/brb3.1238

27.

Xia Z Luo T . Sevoflurane or desflurane anesthesia plus postoperative propofol sedation attenuates myocardial injury after coronary surgery in elderly high-risk patients. Anesthesiology. (2004) 100:1038–9; author reply 1039-1040. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200404000-00050

28.

Li N Ma Y Li C Sun M Qi F . Dexmedetomidine alleviates sevoflurane-induced neuroinflammation and neurocognitive disorders by suppressing the P2X4R/NLRP3 pathway in aged mice. Int J Neurosci. (2024) 134:511–21. doi: 10.1080/00207454.2022.2121921

29.

Markuliak RČLHM . General inhalational anesthetics - pharmacodynamics, pharmacokinetics and chiral properties. Cesk Slov Farm. (2021) 70:7–17. PMID:

30.

Tachibana S Hayase T Osuda M Kazuma S Yamakage M . Recovery of postoperative cognitive function in elderly patients after a long duration of desflurane anesthesia: a pilot study. J Anesth. (2015) 29:627–30. doi: 10.1007/s00540-015-1979-y

31.

Pakpirom J Kraithep J Pattaravit N . Length of postanesthetic care unit stay in elderly patients after general anesthesia: a randomized controlled trial comparing desflurane and sevoflurane. J Clin Anesth. (2016) 32:294–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinane.2015.08.016

32.

Takeyama E Nakajima M Nakanishi Y Amano E Shibuya H . Longer time to extubation after general anesthesia with desflurane in patients with obstructive respiratory dysfunction: a retrospective study. JA Clin Rep. (2021) 7:40. doi: 10.1186/s40981-021-00443-x

33.

Grabitz SD Farhan HN Ruscic KJ Timm FP Shin CH Thevathasan T et al . Dose-dependent protective effect of inhalational anesthetics against postoperative respiratory complications: a prospective analysis of data on file from three hospitals in New England. Crit Care Med. (2017) 45:e30–9. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000002015

34.

Zucco L Santer P Levy N Hammer M Grabitz SD Nabel S et al . A comparison of postoperative respiratory complications associated with the use of desflurane and sevoflurane: a single-Centre cohort study. Anaesthesia. (2021) 76:36–44. doi: 10.1111/anae.15203

35.

Zhang YT Chen Y Shang KX Yu H Li XF Yu H . Effect of volatile anesthesia versus intravenous anesthesia on postoperative pulmonary complications in patients undergoing minimally invasive Esophagectomy: a randomized clinical trial. Anesth Analg. (2024) 139:571–80. doi: 10.1213/ANE.0000000000006814

36.

Jiang Z Wu Y Liang F Jian M Liu H Mei H et al . Brain relaxation using desflurane anesthesia and total intravenous anesthesia in patients undergoing craniotomy for supratentorial tumors: a randomized controlled study. BMC Anesthesiol. (2023) 23:15. doi: 10.1186/s12871-023-01970-z

37.

Lee JW Kim MK Kim JY . Hemodynamic responses to 1 MAC desflurane inhalation during anesthesia induction with propofol bolus and remifentanil continuous infusion: a prospective randomized single-blind clinical investigation. BMC Anesthesiol. (2023) 23:59. doi: 10.1186/s12871-023-02002-6

38.

Hendrickx JFA Nielsen OJ De Hert S De Wolf AM . The science behind banning desflurane: a narrative review. Eur J Anaesthesiol. (2022) 39:818–24. doi: 10.1097/EJA.0000000000001739

39.

Shirozu K Nobukuni K Umehara K Nagamatsu M Higashi M Yamaura K . Comparison of the occurrence of postoperative shivering between sevoflurane and Desflurane anesthesia. Ther Hypothermia Temp Manag. (2022) 12:177–81. doi: 10.1089/ther.2021.0029

40.

Breth-Petersen M Barratt AL McGain F Skowno JJ Zhong G Weatherall AD et al . Exploring anaesthetists' views on the carbon footprint of anaesthesia and identifying opportunities and challenges for reducing its impact on the environment. Anaesth Intensive Care. (2024) 52:91–104. doi: 10.1177/0310057X231212211

Summary

Keywords

desflurane, sevoflurane, elderly patients, orthopedic surgery, postoperative cognitive function, early recovery quality

Citation

Dong R, Song C, Li J, Ji X, Ren C and Zhang Q (2025) Comparison of the safety and efficacy of desflurane versus sevoflurane on postoperative cognitive function and early recovery quality in elderly orthopedic patients: a prospective, randomized controlled trial. Front. Med. 12:1707107. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2025.1707107

Received

17 September 2025

Revised

02 November 2025

Accepted

13 November 2025

Published

26 November 2025

Volume

12 - 2025

Edited by

Luis Laranjeira, Ordem dos Médicos, Portugal

Reviewed by

Juan Moisés De La Serna, International University of La Rioja, Spain

Somchai Amornyotin, Mahidol University, Thailand

Updates

Copyright

© 2025 Dong, Song, Li, Ji, Ren and Zhang.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Qingzhi Zhang, 15339942816@163.com

†These authors share first authorship

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.