Abstract

Background:

Efficient oxygen transport depends on hemoglobin (Hb) affinity for O2, which is modulated by factors like PCO2, as described by the Bohr effect. This in vitro study explored how varying PO2 and PCO2 influence hemoglobin oxygen saturation (HbO2) and plasma electrolyte concentrations in whole human blood.

Methods:

Blood from six healthy volunteers was equilibrated at 37°C with gas mixtures spanning PO2 and PCO2 ranges. A total of 346 samples were analyzed for blood gases, HbO2, and electrolytes. The HbO2 dissociation curve was modeled using a Gompertz function within a non-linear mixed-effects framework, while electrolyte dynamics were assessed via polynomial models.

Results:

HbO2 saturation ranged from 1.4 to 99.6%. Increasing PCO2 shifted the dissociation curve rightward, steepening its slope and raising the inflection point—hallmarks of the Bohr effect—without affecting maximal HbO2. Electrolyte analysis revealed that chloride decreased with PCO2 and increased with HbO2, consistent with the erythrocyte chloride shift. Sodium increased with PCO2, and a significant interaction between HbO2 and PCO2 was observed. Strong ion difference (SID) decreased linearly with HbO2 and increased quadratically with PCO2, suggesting a compensatory role in CO2-induced acid-base changes.

Conclusion:

These findings, validated against external datasets, underscore the tight coupling between respiratory gas exchange and electrolyte homeostasis. The study provides novel insights into how CO2 modulates both oxygen delivery and plasma ionic composition, with implications for understanding acid-base physiology and its regulation in health and disease.

1 Introduction

The efficient transport of oxygen (O2) in mammals is a critical physiological process that underpins cellular respiration and metabolic function. If O2 transport relied solely on O2 dissolved in plasma, i.e., on Henry’s law, mammals would require an increased atmospheric pressure (1) to maintain an adequate O2 delivery to the tissues. Alternatively, to meet basal metabolic demands without hemoglobin (Hb), the cardiac output would need to rise to nearly 100 liters per minute—far beyond physiological limits.

Evolution has equipped mammals and nearly all vertebrates with Hb, a globular protein that facilitates oxygen transport. Hb reversibly binds O2, enabling efficient delivery from high-pressure environments (lungs) to low-pressure areas (tissues) where oxygen is utilized by mitochondria.

Hb is the second most abundant protein in the human body after collagen, comprised of four subunits—two alpha and two non-alpha chains—forming a tetrameric structure. Each subunit is associated with a heme group, which contains an iron ion (Fe2 +) that is essential for oxygen binding. The cooperative nature of O2 binding to Hb leads to the characteristic sigmoidal oxygen dissociation curve, a phenomenon first described by Paul Bert (2) and later explained in greater detail by Bohr (3–5) who highlighted the relationship between pH, partial pressure of carbon dioxide (PCO2), and the affinity of Hb for O2. The so called “Bohr effect” elucidates how increasing PCO2 and proton concentration (H+) reduces Hb’s affinity for O2, promoting its release in metabolically active tissues. Conversely, the Haldane effect (6, 7) describes how deoxygenated Hb can bind CO2 more effectively, enhancing the transport of CO2 to the lungs for elimination. This interplay between O2 and CO2 binding is crucial for maintaining acid-base balance and ensuring efficient gas exchange.

The conformational changes of Hb are crucial for gas exchange: the transition from a relaxed (R) state, characterized by high affinity for O2, to a taut (T) state, with lower affinity for O2, facilitates the transport and the subsequent release of O2 and CO2 between peripheral tissues and the lungs, and vice versa. Factors such as temperature, pH, and the presence of various ligands (e.g., 2,3-diphosphoglycerate (2,3-DPG), chloride ions) can modulate Hb conformational changes.

The transition from the R to the T conformation also enables Hb to bind or release other molecules, including chloride ions (Cl–) and protons (H+) (8, 9). More broadly, the blood flowing through systemic capillaries, and the resulting changes in gas partial pressures and electrolyte concentrations, leads to a net movement of charges and water across the erythrocyte membrane, and a shift in intracellular charge distribution (10).

Understanding these interactions is essential to understand how Hb responds to varying physiological and pathological conditions, allowing for optimized gas exchange, even under extreme circumstances.

The primary aim of our study is to investigate the behavior of O2 binding to Hb at varying partial pressures of O2 (PO2) and of CO2 (PCO2) in human whole blood and to explore how these variations influence plasma electrolyte levels. While the oxygen dissociation curve and hemoglobin conformational changes have been extensively characterized, the novel contribution of this work lies in the analysis of plasma electrolyte variations in response to changes in gas partial pressures. This aspect has received limited attention in previous literature, despite its physiological relevance. By coupling gas exchange dynamics with electrolyte behavior, our study may reveal previously unrecognized interactions between respiratory gases and membrane ion transport. This research is significant not only for advancing our understanding of the fundamental principles in respiratory physiology, but also for its potential clinical implications, particularly in conditions that affect acid-base balance, oxygen delivery, and carbon dioxide transport. By shedding light on the intricate dynamics of Hb function, we aim to contribute to the broader understanding of respiratory physiology and its critical role in maintaining homeostasis in the human body.

2 Materials and methods

The present study received approval from the Ethical Committee of Fondazione Ca’ Granda Ospedale Maggiore Policlinico (Milan) (Identifier: 429_2019; 21st May 2019). Six healthy volunteers were included in the study following the acquisition of written informed consent.

2.1 Blood sample collection

A total of 42 ml of venous blood was collected from each subject via peripheral venipuncture and distributed in 10 tubes.

Seven lithium-heparin tubes (Vacuette® Plasma Lithium Heparin, 4 mL, Greiner Bio-One™, Kremsmünster, Austria) were used for tonometry. The remaining three samples—two EDTA tubes (3 ml) and one K2EDTA tube with gel (3.5 mL)—were sent for complete blood count, electrolytes, albumin, total protein, and Hb electrophoresis, analyzed using the Cobas® 8000 modular analyzer (Roche, Basel, Switzerland).

2.2 Sample preparation and PCO2 tonometry

Whole blood anticoagulated with lithium heparin was stored at 6°C for at least 30 min to standardize samples and minimize 2,3-DPG degradation (no-touch phase). Each sample was then aspirated into a syringe pre-treated with anti-foam concentrate (T310, RNA Medical, Devens, MA, United States). Blood samples were equilibrated at 37°C with gas mixtures of known PO2 and PCO2, using a tonometer (Equilibrator, RNA Medical, Devens, MA, United States). Complete O2 saturation of hemoglobin at the target CO2 levels (10, 20, 50, 70, or 90 mmHg) was obtained by equilibrating the blood in a continuous-bubble tonometer with a gas mixture of known PO2 and PCO2. After verifying full hemoglobin saturation by blood gas analysis (blood PO2 > 600 mmHg), Hb desaturation was titrated by equilibrating the sample with a gas mixture containing the same target PCO2 (10, 20, 50, 70, or 90 mmHg), a PO2 of zero, and a nitrogen pressure (PN2) adjusted to achieve a total pressure (Ptot) equal to atmospheric pressure (Patm). The titration proceeded until either a PO2 < 10 mmHg was reached or lactate levels increased by more than 2 mmol⋅L–1; relative to baseline. Samples with lactate increases more than 2 mmol/L from baseline were excluded.

2.3 Blood gas analysis

During deoxygenation, samples were repeatedly analyzed at 37°C using a blood gas and electrolyte analyzer (ABL90 FLEX, Radiometer, Copenhagen, Denmark). Measured values were recorded in an Excel spreadsheet for further analysis.

Strong ion difference (SID) was calculated as follows:

where [Na+], [K+], [Ca2 +], [Cl–], and [Lac–] refer to the plasma concentrations of sodium, potassium, calcium, chloride, and lactate, respectively, expressed in mEq/L as measured by the blood gas analyzer. Magnesium [Mg2+] and Phosphate [PO43–] were excluded due to lack of measurement by the blood gas analyzer and minimal impact on SID.

2.4 Mathematical models and statistical analysis

2.4.1 Modeling the hemoglobin-oxygen curve at different PCO2 levels

In this study, we modeled the hemoglobin-oxygen dissociation curve using a three-parameter Gompertz function, which is well-suited for capturing sigmoidal shapes due to its flexibility. A mixed-effects Gompertz model was implemented using SAS PROC NLMIXED to assess the influence of PCO2 and random effects.

The Gompertz function used is defined as:

Where:

-

a represents the upper asymptote of the curve.

-

x0 represents the inflection point of the curve along the x-axis.

-

b controls the growth rate and the steepness of the curve.

To evaluate parameter distributions and determine which should be modeled as fixed or random effects, we conducted preliminary analyses on individual subject data. Further details are provided in Supplementary material.

2.4.1.1 Building the model

The nonlinear mixed model was initially constructed without random effects, modeling each parameter (a, b, x0) as a linear function of PCO2. Residual variance (s2e) was included. The equations were:

Random effects were added stepwise: -individually, in pairs, and jointly-. Effects were retained in the model only if significant (P ≤ 0.05). PCO2 was treated as a continuous variable. Initial values for fixed components were derived from individual fits. Full model selection details are provided in Supplementary material. To better understand how PCO2 affects oxygen affinity, we derived P50 values from the Gompertz model. P50 represents the PO2 at which hemoglobin is 50% saturated and is widely used to describe shifts in the oxygen–hemoglobin dissociation curve.

2.4.2 Strong ion difference and electrolytes

We investigated the effects of HbO2 and PCO2 on strong ion difference (SID) and electrolyte concentrations using polynomial multilevel models with both fixed and random effects.

To assess potential collinearity among the independent variables (HbO2 and PCO2), we calculated the variance inflation factor (VIF) and performed collinearity diagnostics, including the evaluation of eigenvalues and condition indices.

As an initial exploratory step, scatter plots with univariate regressions were used to examine the relationships between the dependent variables (SID and electrolytes) and the independent variables HbO2 and PCO2.

We then modeled the effects of HbO2 and PCO2 on the dependent variables, using a polynomial multilevel model with fixed and random effects, treating both variables as continuous. The inclusion of new effects and the functional form of the relationships were evaluated using likelihood ratio tests (significance threshold: P ≤ 0.100). The optimal covariance structure for the mixed model was selected based on the Akaike Information Criterion (AIC), ensuring the best fit to the data. Model adequacy was assessed through residual analysis, and model validation was performed using bootstrap resampling (see Supplementary material for further details).

The SID and electrolytes models were then tested using experimental data from 18 healthy subjects, as reported by Langer et al. (11).

Values of SID, Na+ and Cl– were estimated using our models at the average PCO2 values reported in the Langer’s study, assuming HbO2 of 98% as the original paper did not report HbO2 values. The authors stated that venous blood samples were tonometrically oxygenated at 21% O2. Based on this, we assumed that the blood was fully oxygenated at the end of the tonometry process. Since HbO2 is typically slightly lower than oxygen saturation due to the presence of carboxyhemoglobin and methemoglobin, we adopted a physiologically plausible HbO2 value of 98% for our estimations.

2.4.3 Other statistical analysis

Continuous data are presented as median and interquartile range (IQR) or mean [ ± standard deviation, SD], as appropriate. We did not apply any imputation for missing values. The initial assessment of the relationships between electrolytes, HbO2 and PCO2, between the values of PO2 at which Hb is 50% saturated (P50) and PCO2 and between SID and electrolytes were modeled by univariate regressions.

Analyses were performed using SAS 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, North Carolina, United States) and SigmaPlot (Systat Software, San Jose, CA).

3 Results

Table 1 summarizes the general characteristics of the population and presents the results of the blood analyses. Of note all parameters are in the normal range. No Hb alterations were detected.

TABLE 1

| Variables | Median [IQR] |

|---|---|

| Age (years) | 31 [29–34] |

| Height (m) | 1.78 [1.75–1.81] |

| Weight (kg) | 71.5 [70.3–75.0] |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 23.03 [22.27–23.50] |

| Sodium (mmol/L) | 142 [141–143] |

| Potassium (mmol/L) | 4.35 [4.15–4.55] |

| Chlorine (mmol/L) | 102 [101–103] |

| Tot. Protein (g/dL) | 7.20 [7.03–7.30] |

| Albumin (g/dL) | 4.8 [4.6–4.8] |

| Calcium (mg/dL) | 9.55 [9.42–9.61] |

| Phosphate (mg/dL) | 3.2 [3.1–3.7] |

| Magnesium (mg/dL) | 2.10 [2.02–2.14] |

| White blood cells (10^9/L) | 5.49 [5.29–6.47] |

| Red blood cells (10^9/L) | 5.32 [4.98–5.43] |

| Hemoglobin (g/dL) | 15 [15–16] |

| Hematocrit (%) | 43.7 [42.1–44.5] |

| Mean globular volume (fL) | 82.6 [80.9–84.8] |

| Anisocytosis index (%) | 35.1 [34.4–35.3] |

| MCH (pg) | 12.3 [11.9–12.7] |

| MCHC (g/dL) | 29.1 [27.9–29.9] |

| HbA2 (%) | 35.1 [34.4–35.3] |

| HbF (%) | 2.7 [2.6–2.8] |

Characteristics of population, blood count and electrolytes concentrations prior to any manipulation.

(MCHC, Mean Corpuscular Hemoglobin Concentration; MCH, Mean Corpuscular Hemoglobin; HbA2, A2 Hemoglobin; HbF, Fetal Hemoglobin).

Six healthy male subjects aged between 28 and 36 years old (mean age, 32 ± 3 years) were enrolled in the study. A total of 361 blood samples were collected, of which 15 (4.2%) were excluded from statistical analysis due to a lactate increase > 2 mEq/L compared to baseline. The final dataset therefore included 346 samples, with a median lactate variation of 0.3 mEq/L (IQR 0.1–0.6 mEq/L).

In the 346 blood samples titrated with nominal PCO2, the measured PCO2 values ranged between 6 and 111 mmHg (median 52.6 mmHg, IQR 18.1–73.7) and measured PO2 ranged between 0.1 and 721.0 mmHg (median 57.6 mmHg, IQR 32.5–97.5), resulting in a range of HbO2 from 1.4 to 99.6% (median 89.8%, IQR 67.2–96.7%).

3.1 Oxygen–hemoglobin dissociation curve

3.1.1 Analysis of experimental data and individual curve fitting

The results of the preliminary data analyses, including experimental data, individual fits, residuals, parameter distributions, and model selection details, are provided in Supplementary material. The inspection of the residuals indicated that the Gompertz model adequately described our data.

Graphs of the individual parameter means and 95% CIs at different nominal PCO2 levels suggested the need to test whether the parameters should be treated as random or fixed effects. The upper asymptote a is not affected by PCO2, on the contrary b and x0 are right-shifted at increasing nominal PCO2 values (Supplementary Table 5).

3.1.2 Building the mixed model

Details of the parameter selection process are provided in Supplementary material. The analysis showed that random effects did not significantly improve the model, so they were excluded. As expected from the individual curve fittings, parameter a did not show a significant dependence on PCO2 (aPCO2: P = 0.6751) and was therefore excluded from the model. Consequently, the final model was constructed without random effects with PCO2 affecting parameters b and x0:

where:

Table 2 reports the estimated parameters, along with standard errors, CIs and P-values.

TABLE 2

| Parameters | Estimate | Standard error | 95% CIs | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| a | 97.1399 | 0.1548 | 96.8354 | 97.4444 | <0.0001 |

| bfix | 9.2308 | 0.2089 | 8.8199 | 9.6418 | <0.0001 |

| bPCO2 | 0.1062 | 0.0037 | 0.0989 | 0.1136 | <0.0001 |

| x0fix | 11.1305 | 0.1659 | 10.8043 | 11.4568 | <0.0001 |

| x0PCO2 | 0.1793 | 0.0031 | 0.1732 | 0.1855 | <0.0001 |

| s2e | 3.2723 | 0.2488 | 2.7830 | 3.7616 | <0.0001 |

Estimated parameters from the nonlinear mixed model (Gompertz equation) applied to describe oxygen-hemoglobin dissociation curves at different PCO2.

CIs, confidence limits.

Figure 1 illustrates the oxygen–hemoglobin dissociation curves estimated using the Gompertz mixed model at PCO2 values ranging between 5 and 110 mmHg (in 5 mmHg increments), with experimental data points grouped into 5 mmHg intervals for visualization purposes. Experimental PCO2 values were categorized into groups, from 5 to 110 mmHg, centered on multiples of 5 mmHg, each spanning ± 2.5 mmHg (e.g., the group centered at 5 mmHg included values from 2.5 to 7.5 mmHg).

FIGURE 1

Figure shows oxygen–hemoglobin dissociation curves estimated using the Gompertz mixed model (lines) at PCO2 values ranging from 5 to 110 mmHg (in 5 mmHg increments), with experimental data points (dots) grouped into 5 mmHg intervals for visualization purposes. Experimental PCO2 values were categorized into groups, from 5 to 110 mmHg, centered on multiples of 5 mmHg, each spanning ± 2.5 mmHg (e.g., the group centered at 5 mmHg included values from 2.5 to 7.5 mmHg). Red dashed lines represent reference lines at 50 and 100% HbO2.

The values of P50 estimated by the Gompertz model at different PCO2 values (5–100 mmHg) are reported in Supplementary Table 16. The increase in PCO2 significantly shifted (P < 0.0001) the P50 values to the right following the equation P50 = 14.91 + 0.22⋅PCO2.

3.2 Electrolytes

Collinearity diagnostics showed no significant collinearity among the independent variables.

A detailed description of model selection procedures—including LRT results, AIC values, residual inspection, and graphical representations— and comparisons between experimental data points with the estimated relationships are provided in Supplementary material.

3.2.1 Strong ion difference

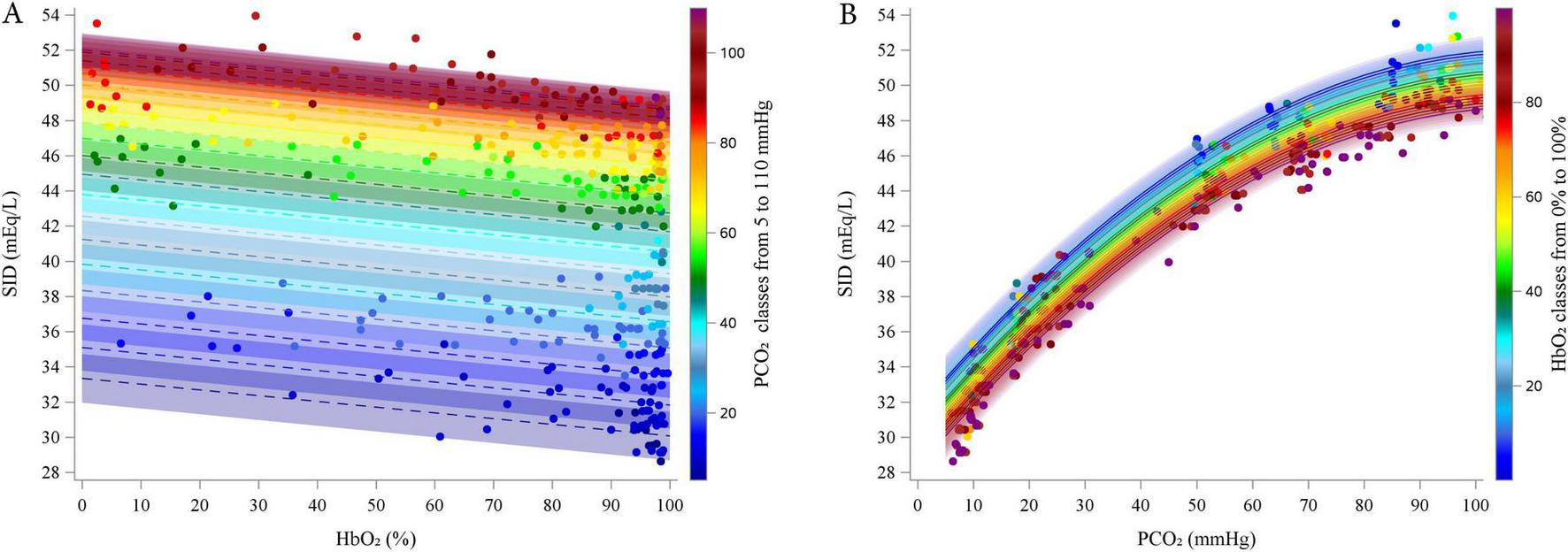

Preliminary graphical analyses suggested a linear relationship between SID and HbO2 and a quadratic relationship between SID and PCO2 (Supplementary Figures 10–13). The final polynomial multilevel model included HbO2 and PCO2 as predictors of both the intercept and the linear terms, as well as a quadratic term for PCO2. Random intercepts at the subject level and slopes for PCO2 were included. The model used an unstructured covariance matrix (AIC 892.8). Table 3 reports the estimated fixed effects parameters. Residual plots showed no autocorrelation, and bootstrap analysis (1,000 resamples) confirmed parameter reliability (see Supplementary material for details). Figure 2 illustrates the relationships between SID and HbO2 at different PCO2 levels (panel A; experimental data points grouped by 5 mmHg) and between SID and PCO2 and different HbO2 (panel B; data grouped in 5% intervals).

TABLE 3

| Parameters | Estimate | Standard error | 95% CIs | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept | 31.5013 | 0.5911 | 30.0517 | 32.9509 | <0.0001 |

| HbO2: linear | −0.0327 | 0.0015 | −0.0357 | −0.0297 | <0.0001 |

| PCO2: linear | 0.3763 | 0.0085 | 0.3584 | 0.3943 | <0.0001 |

| PCO2: quadratic | −0.0017 | 0.0001 | −0.0018 | −0.0016 | <0.0001 |

Estimated parameters from the linear mixed model applied to describe the relationship between SID, HbO2, and PCO2.

CIs, confidence limits.

FIGURE 2

Estimated relationship (lines) between estimated SID and HbO2 at different PCO2 (5–110 by 5 mmHg, A) and between SID and PCO2 at different HbO2 (0–100% by 5% B). Dots represent experimental points. categorized into groups, from 5 to 110 mmHg, centered on multiples of 5 mmHg, each spanning ± 2.5 mmHg (e.g., the group centered at 5 mmHg included values from 2.5 to 7.5 mmHg).

According to the model, SID decreased linearly with increasing HbO2 (coefficient = -0.0327, P < 0.0001). Conversely, SID initially increased with rising PCO2 (linear coefficient = 0.3763, P < 0.0001), but this effect diminished at higher PCO2 values, as indicated by the negative quadratic coefficient (coefficient = -0.0017, P < 0.0001). The interaction term was excluded from the final model due to lack of statistical significance.

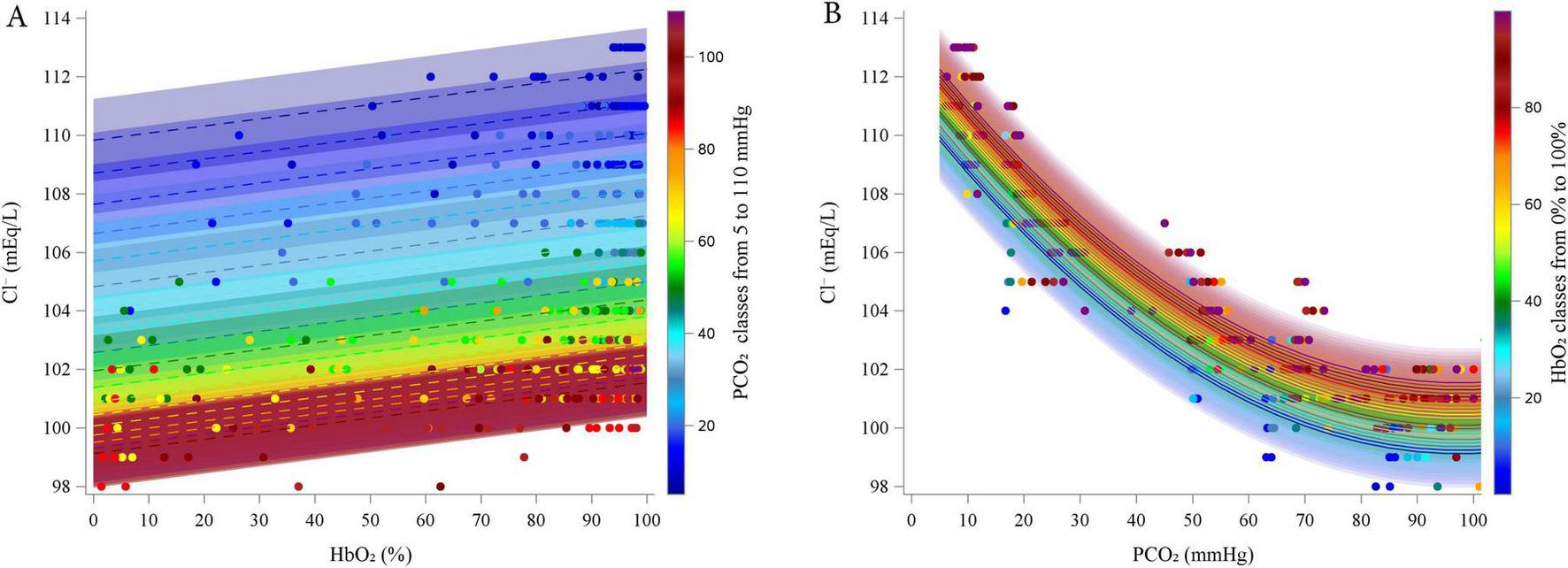

3.2.2 Chloride

Preliminary graphical analyses suggested a linear relationship between Cl– and HbO2, and a quadratic relationship between Cl– and PCO2 (see Supplementary Figures 21–24).

The final polynomial multilevel model included HbO2 and PCO2 as predictors of both the intercept and the linear terms, along with a quadratic term for PCO2. Random intercepts at the subject level and random slopes for PCO2 were included. The model was implemented using an unstructured covariance matrix (AIC = 846.0). The estimated fixed effects parameters are reported in Table 4.

TABLE 4

| Parameters | Estimate | Standard error | 95% CI | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept | 111.0100 | 0.5846 | 109.5700 | 112.4500 | <0.0001 |

| HbO2: linear | 0.0242 | 0.0014 | 0.0214 | 0.0271 | <0.0001 |

| PCO2: linear | −0.2438 | 0.0068 | −0.2575 | −0.2302 | <0.0001 |

| PCO2: quadratic | 0.0012 | 0.0001 | 0.0011 | 0.0014 | <0.0001 |

Estimated parameters from the linear mixed model applied to describe the relationship between chloride, HbO2 and PCO2.

CIs, confidence limits.

Residual plots showed no autocorrelation, and bootstrap analysis (1,000 resamples) confirmed parameter reliability (see Supplementary material for details).

Figure 3 illustrates the relationships between Cl– and HbO2 at different PCO2 levels (panel A; experimental data grouped in 5 mmHg intervals), and between Cl– and PCO2 at different HbO2 levels (panel B; data grouped in 5% intervals).

FIGURE 3

Estimated relationship (lines) between estimated Chloride and HbO2 at different PCO2 (5–110 by 5 mmHg, A) and between Chloride and PCO2 at different HbO2 (0–100% by 5%, B). Dots represent experimental points. categorized into groups, from 5 to 110 mmHg, centered on multiples of 5 mmHg, each spanning ± 2.5 mmHg (e.g., the group centered at 5 mmHg included values from 2.5 to 7.5 mmHg).

According to the model, Cl– increased linearly with increasing HbO2 (coefficient = 0.0242, P < 0.0001). In contrast, Cl– decreased with rising PCO2 (linear coefficient = -0.2438, P < 0.0001), but this effect diminished at higher PCO2 levels, as indicated by the positive quadratic coefficient (quadratic coefficient = 0.0012, P < 0.0001). The interaction term was excluded from the final model due to lack of statistical significance.

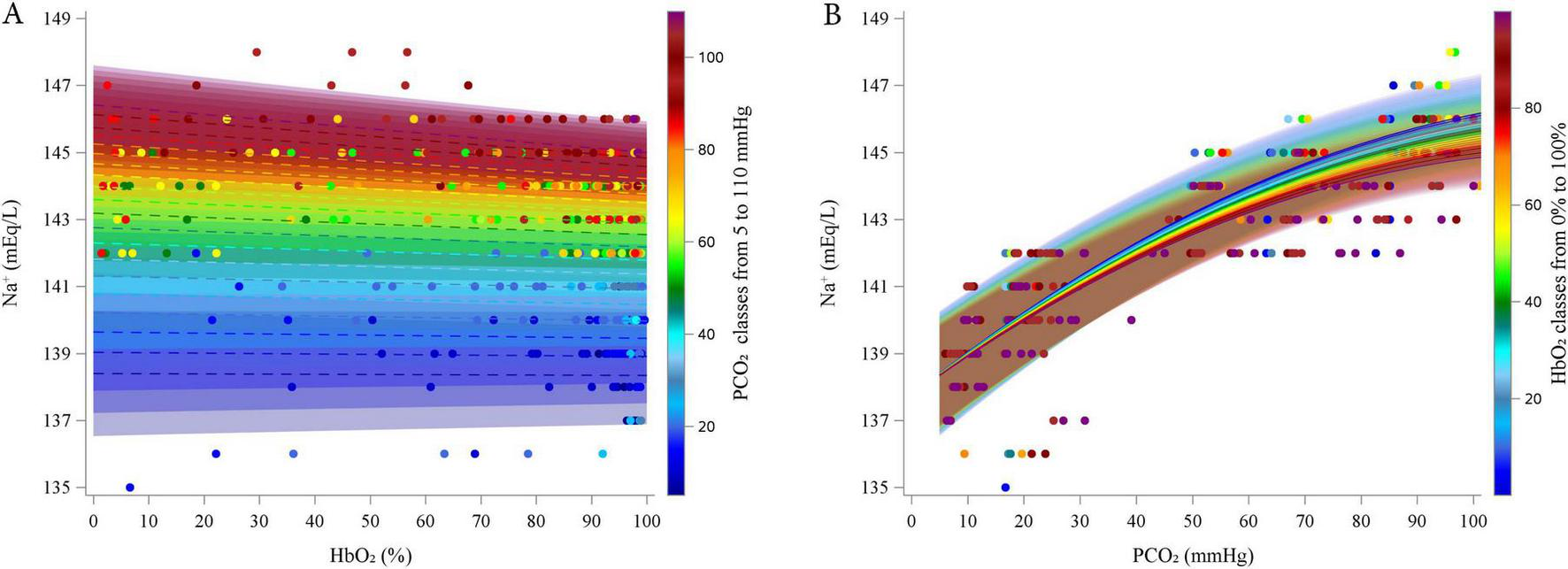

3.2.3 Sodium

Preliminary graphical analyses suggested a linear relationship between Na+ and HbO2 and suggested a quadratic association between Na+ and PCO2 (Supplementary Figures 32–35). The final polynomial multilevel model included HbO2 and PCO2 as predictors of both the intercept and the linear terms, along with a quadratic term for PCO2. An interaction term between the HbO2 and PCO2 was also included. Random intercepts at the subject level and random slopes for HbO2 and PCO2 were included. The model was fitted using an unstructured covariance matrix (AIC 940.9). Table 5 reports the estimated fixed effects parameters of the model. Residual plots showed no autocorrelation, and bootstrap analysis (730 resamples) confirmed parameter reliability (see Supplementary material for details). Figure 4 represents the relationships between Na+ and HbO2 at different PCO2 (panel A; experimental data grouped in 5 mmHg intervals) and between Na+ and PCO2 and different HbO2 (panel B; data grouped in 5% intervals). As PCO2 increased, Na+ initially increased due to the positive linear coefficient (coefficient = 0.134, P < 0.0001), but this effect diminished at higher levels of PCO2, as shown by the negative quadratic coefficient (coefficient = -0.00050, P < 0.0001). The linear effect HbO2 was not statistically significant. However, the interaction between HbO2 and PCO2 was significant (coefficient = -0.0001, P = 0.030), suggesting that HbO2 slightly reduced Na+ levels, particularly at higher PCO2 levels. This interaction may reflect a subtle but significant modulation of Na+ by oxygenation status under varying CO2 conditions.

TABLE 5

| Parameters | Estimate | Standard error | 95% CI | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept | 137.7400 | 0.8170 | 135.8100 | 139.6700 | <0.0001 |

| HbO2: linear* | 0.00007 | 0.0039 | −0.0078 | 0.0079 | 0.986 |

| PCO2: linear | 0.1339 | 0.0100 | 0.1138 | 0.1540 | <0.0001 |

| PCO2: quadratic | −0.00050 | 0.000059 | −0.00062 | −0.00038 | <0.0001 |

| HbO2 and PCO2 interaction | −0.000130 | 0.000060 | −0.000250 | −0.000010 | 0.030 |

Estimated parameters from the linear mixed model applied to describe the relationship between sodium, HbO2 and PCO2.

CIs, confidence limits.

*Not statistically significant.

FIGURE 4

Estimated relationship (lines) between estimated Sodium and HbO2 at different PCO2 (5–110 by 5 mmHg, A) and between Sodium and PCO2 at different HbO2 (0–100% by 5%, B). Dots represent experimental points. categorized into groups, from 5 to 110 mmHg, centered on multiples of 5 mmHg, each spanning ± 2.5 mmHg (e.g., the group centered at 5 mmHg included values from 2.5 to 7.5 mmHg).

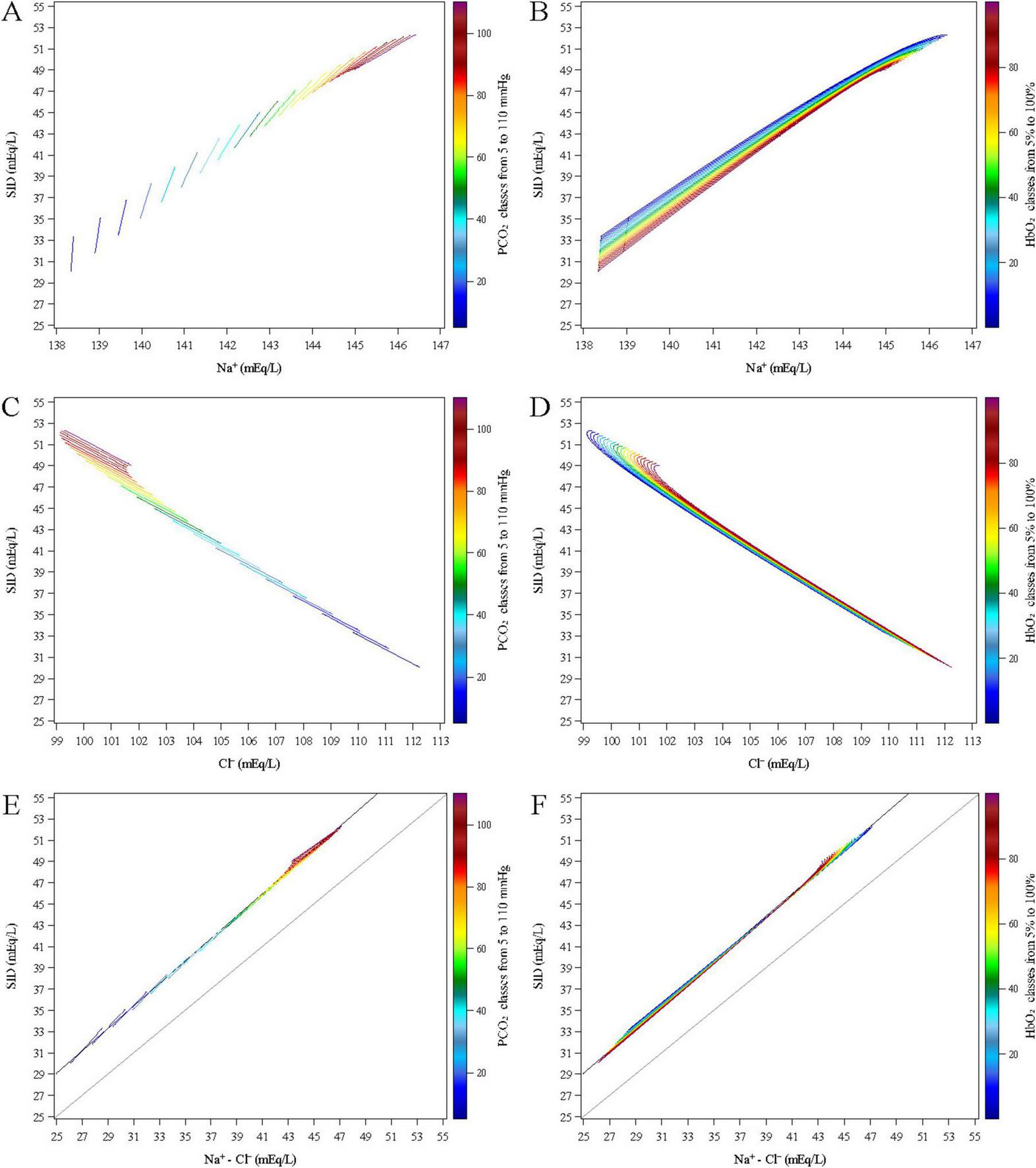

3.2.4 Correlations between electrolytes

Figure 5 shows the relationship between the SID and Na+, Cl– and their difference (Na+-Cl–) across a simulated range of PCO2 (from 5 to 110 mmHg in 5 mmHg increments) and of HbO2 (from 5 to 100% in 5% increments). The values of SID, Na+, and Cl– were computed using the equations derived from the previously described mixed linear models.

FIGURE 5

Estimated relationships between the SID and Na+ (upper panels A,B), Cl– (middle panels C,D) and their difference (Na+-Cl–, lower panels E,F) across a simulated range of PCO2 (from 5 to 110 mmHg in 5 mmHg increments, left panels A,C,E) and of HbO2 (from 5 to 100% in 5% increments, right panels B,D,F).

Figure 5A shows a direct relationship between Na+ and SID across varying levels PCO2. This relationship is modulated by HbO2 (Figure 5B), which drove the variation within each PCO2 value. SID consistently decreased with increasing HbO2, regardless of PCO2 level. At low PCO2, Na+ remained relatively stable across varying levels of HbO2 levels, resulting in a nearly linear relationship with a steep slope (e.g., slope = 56.67 at PCO2 = 5 mmHg). As PCO2 increased, the slope decreased markedly, approaching values close to 2 (e.g., 2.81, 2.66, and 2.53 at PCO2 = 90, 95, and 100 mmHg, respectively. At high PCO2 levels, the SID–Na+ curves tended to overlap, reflecting quadratic dependence on PCO2 in the underlying model equations.

Figures 5C,D show a negative relationship between SID and Cl– across all PCO2 levels. As Cl– increased, SID decreased, reflecting the inverse contribution of chloride to the strong ion balance. The relationship remained consistently linear across the full range of HbO2, with a constant slope of approximately -1.35. At higher PCO2 levels, the SID–Cl– curves also tended to overlap, again due to the quadratic terms in the underlying equations.

The lower panels (E and F) show a positive linear relationship between SID and the difference Na+- Cl– across all PCO2 levels. As Na+- Cl– increased, SID increased proportionally, reflecting the direct contribution of strong cations and anions to the strong ion balance. The relationship is described by the equation:

With an R2 = 0.999 (P < 0.0001), indicating that the Na+- Cl– difference explained nearly all of the variability in SID. The median ratio (Na+-Cl–)/SID was 89.2% (IQR: 88.5–89.6). The intercept of the regression model likely reflects the contribution of other strong ions—such as potassium, calcium, and lactate.

For each fixed PCO2 value, the relationship remained linear across the full range of HbO2. As PCO2 increased, the slope of SID vs. Na+—Cl– relationship slightly decreased (e.g., 1.32 at PCO2 = 5 mmHg vs. 0.88 at PCO2 = 110 mmHg). This reduction in slope was smaller than the difference between the slope of Na+ and that of Cl–, indicating that Na+—Cl– was not a simple linear combination of the two variables. At higher PCO2 levels, the SID vs. Na+- Cl– curves corresponding to different HbO2 values tended to overlap, again due to the quadratic terms in the model equations.

3.2.5 Model validation

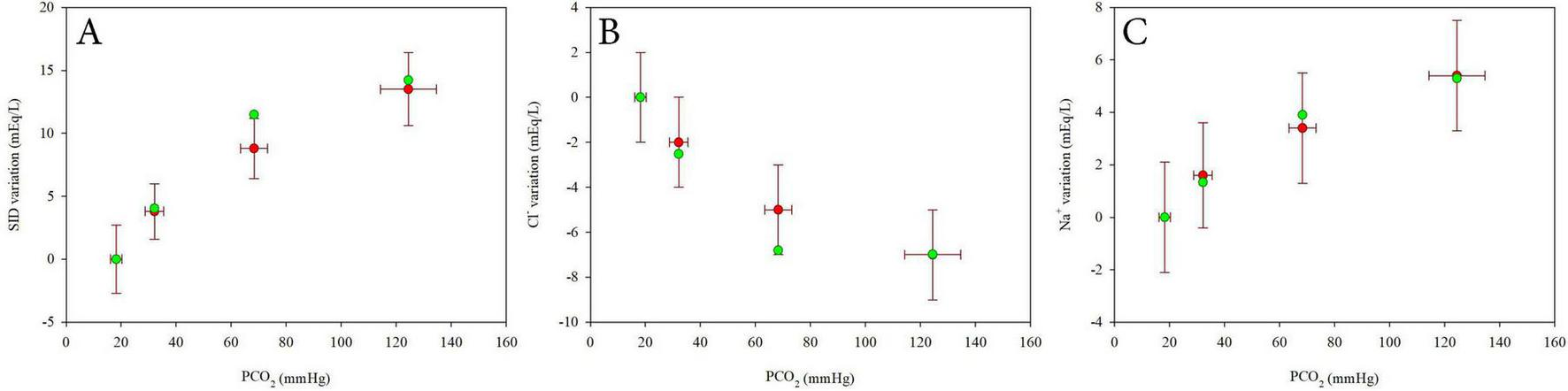

Supplementary Figure 43 and Figure 6 present the model validation using experimental data from 18 healthy subjects, as reported by Langer al. (11).

FIGURE 6

Comparison between experimental data from Langer et al. (9) (mean ± SD, red dots) and values estimated using linear mixed models (green dots) for SID variations (A), Chloride variations (B) and Sodium variations (C) at varying PCO2. Values are expressed as difference from the first value at 2% CO2.

Values of SID, Na+ and Cl– were estimated using the model at the average PCO2 values reported in the study and assuming HbO2 = 98%. Absolute values (Supplementary Figure 43) and the differences from the reference value at 5% CO2 (Figure 6) were plotted against PCO2 to assess model performance across a range of respiratory conditions. The model showed good agreement with the average experimental data, particularly in terms of the differences from the reference condition, supporting its validity and robustness.

4 Discussion

In this study, we investigated the hemoglobin-oxygen dissociation curves in whole human blood across a wide range of PO2 and PCO2. Using experimental data, we achieved a robust fit of the characteristic asymmetric sigmoidal shape of the dissociation curves at various levels of PCO2 by applying a Gompertz mixed-effects model. As expected, increasing PCO2 shifted the curves to the right, reflecting a decreased affinity of Hb for oxygen and thus promoting oxygen release. We also modeled the associated changes in plasma electrolyte concentrations using polynomial mixed-effects models. We observed that rising PCO2 and decreasing HbO2 were associated with an increased SID, primarily due to a reduction in chloride ions and a concurrent rise in sodium levels.

From an evolutionary perspective, the ability to utilize oxygen via mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation—aerobic metabolism—provided a substantial advantage in energy production over anaerobic pathways. This metabolic efficiency supported the development of more complex life forms, including humans. On a broader scale, terrestrial life emerged through the interplay of two complementary biochemical cycles: photosynthesis and cellular respiration. Photosynthesis converts solar energy, water, and carbon dioxide into glucose and oxygen, while cellular respiration uses glucose and oxygen to generate carbon dioxide, water, and energy in the form of adenosine triphosphate (ATP). Interestingly, while oxygen is essential for aerobic life, it is also highly reactive and potentially toxic in the absence of effective antioxidant defenses. As a result, aerobic organisms have evolved to maintain relatively low oxygen reserves in the body, relying instead on continuous delivery to meet metabolic demands. In the average adult human, total body oxygen content is surprisingly limited, approximately 1.5 L, despite a high consumption rate of around 250 mL per minute. More than half of this oxygen is carried in the blood, predominantly bound to Hb. Only a small fraction is dissolved in plasma, yet this dissolved component determines the partial pressure of oxygen (PO2). For examples, at a PO2 of 100 mmHg, only about 0.31 mL of O2 is dissolved per 100 mL of blood, whereas over 19 mL of O2 is carried bound to Hb in a healthy individual.

The shape of the oxygen–hemoglobin dissociation curve provides several physiological advantages that optimize both oxygen uptake in the lungs and delivery to peripheral tissues. The upper plateau of the curve ensures near-complete Hb saturation even when alveolar PO2 is moderately reduced, thereby maintaining a favorable diffusion gradient from alveoli to blood. In contrast, the steep slope of the lower portion of the curve facilitates rapid oxygen unloading in peripheral tissues, where PO2 is lower.

Importantly, the position of the dissociation curve is not fixed but is dynamically modulated by several factors, including pH, PCO2, temperature, and 2,3-DPG. Among these, PCO2, central to our investigation, plays a particularly prominent role as originally described by Bohr. Elevated PCO2 levels, such as those found in metabolically active tissues, shift the curve to the right, decreasing Hb’s affinity for oxygen and promoting its release. This rightward shift helps maintain the necessary PO2 gradient that drives oxygen diffusion from Hb to tissues, ultimately enabling oxygen to reach the mitochondria where it is consumed.

Based on our data, assuming a venous PO2 of 40 mmHg, a PCO2 of 46 mmHg, and 15 g/dL of Hb, the resulting Hb saturation would be approximately 77.02%, corresponding to an oxygen content of 16.18 mL O2 per 100 mL of blood. Without the rightward shift caused by the increase in PCO2 from 40 mmHg (arterial) to 46 mmHg (venous), the same PO2 of 40 mmHg would result in a saturation of 79.53%, with an oxygen content of 16.71 mL/100 mL. We can therefore estimate that the Bohr effect, due solely to the 6 mmHg arterio-venous increase in PCO2, contributes to the release of more than 26 mL of O2 per minute, approximately 10% of total oxygen consumption, at constant PO2.

Compared to the pivotal findings originally reported by Bohr (3), we observed a smaller shift of the oxygen–hemoglobin dissociation curve in response to varying PCO levels (see Supplementary Figure 9). This difference may be partially explained by the use of animal blood in Bohr’s experiments. It is well established that Hb’s affinity for oxygen varies across species (12–14). While maintaining a similar quaternary structure, differences in primary amino acid sequences can significantly alter ligand-binding properties. These changes at specific protein sites affect Hb’s behavior in the presence of gases. Furthermore, differences exist in the types of organic phosphate molecules bound by Hb, for example, inositol-5-phosphate in birds, 2,3-DPG in mammals, and ATP and GTP in fish. These differences may confer an evolutionary advantage under extreme conditions, such as those faced by organisms living at low temperatures, animals undergoing prolonged apnea, or organisms adapted to flight (15).

In our study, we also investigated the behavior of plasma electrolytes in whole blood from healthy human subjects in response to variations in PO2 and PCO2. The experimental design was structured to eliminate confounding factors such as electrolyte exchange between blood and interstitial compartments or organs, fluid infusion, and renal filtration.

Significant changes in chloride ion concentrations [Cl–] were observed with PCO2 variations. Specifically, [Cl–] decreased as at increasing PCO2 levels. In contrast, plasma [Na+] showed the opposite behavior.

Variations in HbO2 were also associated with significant changes in [Cl–], but not in [Na+]. Higher [Cl–] were observed at HbO2 near 100%, while lower [Cl–] concentrations were found at lower Hb saturation.

This chloride behavior is consistent with the classic “chloride shift” described over a century ago by Hamburger (16, 17). As PCO2 increases, bicarbonate ions accumulate within red blood cells due to the activity of carbonic anhydrase. Cl– ions are exchanged with bicarbonate, moving from the extracellular/plasma compartment into the erythrocytes. The chloride shift through the red blood cells membrane, can be the result of the Cl–/HCO3– antiport via Anion Exchanger 1 (also known as Band 3), the most abundant transport protein in the red blood cells membrane (18).

Moreover, the observed changes in [Cl–] with varying HbO2 may be attributed to the differing binding capacities of the two Hb conformational states. In the oxygenated R-state, Hb has significantly lower affinity for chloride ions, protons, and organic phosphates, resulting in their release into the erythrocytic cytoplasm. Previous studies have reported the release of approximately 1.8 Cl– per Hb tetramer during the T-to-R transition at pH 7.4 (19).

Prange et al. (8) reported no differences in [Na+] in human whole blood and plasma across physiological ranges of PO2 and PCO2 designed to mimic the arteriovenous difference. This contrasts with the findings of Langer et al. (20), who observed significant variations in both [Cl–] and [Na+] under varying gas pressures across an extracorporeal membrane oxygenation system. Similarly, Krbec et al. (11, 21) demonstrated comparable changes in [Cl–] and [Na+] in whole human blood by experimentally varying PCO2 levels.

Our results confirm the changes of both [Cl–] and [Na+] in response to variations in PCO2. While the mechanisms driving [Cl–] shifts are well established, the behavior of [Na+] remains less clear and requires further investigation. One hypothesis is that an increased intracellular negative charge, particularly during deoxygenation and bicarbonate accumulation, may favor the passive influx of positively charged ions such as Na+. Changes in intracellular [Na+] may also correlate with solute-free water movement across the erythrocyte membrane, a response to alterations in intracellular charge (22–24). Alternatively, changes in blood pH due to variations in gas pressures might affect the structure and charge of plasma proteins, altering their capacity to bind sodium. Consequently, Na+ could transit from the free ion pool to a protein-bound form, thereby contributing to the so-called Strong Ion Reserve (25), a buffer system consisting of ions reversibly bound to plasma proteins. According to Stewart’s model, both PCO2 and SID are independent variables influencing pH. However, our data suggests a more complex interplay between PCO2, Hb conformation, and SID. Although Stewart’s model primarily addresses equilibrium in a single-compartment system, it acknowledges both passive (as in the case of Cl–) and active ion shifts in response to PCO2 changes. In our experiment, plasma ion concentrations varied in a manner that appears to counteract the changes induced by PCO2 variation, potentially buffering pH changes. This agrees with the findings of Langer et al. (20), Prange et al. (8), and Krbec et al. (21), who noted that, without SID variations in response to increased PCO2, pH would change far more drastically during the arteriovenous transition.

Our data provide valuable insights into the dynamics of blood electrolyte changes following substantial shifts in PO2 and PCO2, which can occur in both physiological and pathological conditions, such as acute changes in minute ventilation or during extracorporeal treatments.

For instance, during extracorporeal respiratory support, blood entering the oxygenator undergoes a marked transition from deoxygenated, hypercapnic conditions to oxygenated, hypocapnic states. A clearer understanding of the mechanisms by which electrolyte concentrations across the red blood cell membrane respond to variations in gas partial pressures may help clinicians optimize extracorporeal support settings.

5 Limitations

First, we used a limited set of nominal PCO2 values (10, 20, 50, 70, and 90 mmHg), which left a portion of the physiological PCO2 range underrepresented. To mitigate this issue, we treated PCO2 as a continuous variable in the modeling process, leveraging the broader distribution of measured PCO2 values obtained from blood gas analysis. This approach allowed the model to interpolate across intermediate PCO2 levels not explicitly included in the experimental design. Importantly, the HbO2 vs. PO2 dissociation curves were highly precise, and the consistency of the model across the full PO2 range suggests that the estimated curves at untested PCO2 levels are reliable and physiologically plausible.

Second, since Hb saturation was titrated at 37°C by progressively reducing PO2 at constant PCO2, the duration of gas equilibration led to increased lactate levels at lower saturation values. This likely introduced a metabolic component influencing pH at the lowest HbO2 levels. To minimize this confounding effect, we excluded from analysis 16 data points in which lactate increased by more than 2 mmol/L compared to baseline.

It is important to note that the models used to describe SID and electrolytes are dependent on the chosen functional form of the equations. Although model selection was guided by statistical criteria to identify the best-fitting formulations, the use of polynomial mixed-effects models may have influenced the behavior of the curves, particularly at the extremes of the PCO2 range. For instance, what might physiologically correspond to a plateau could be misrepresented by a downward trend due to the curvature imposed by a polynomial function. This highlights the need for cautious interpretation of model predictions, especially outside the range of experimental data.

To further support our findings, we applied our equations to data extracted from a previously published study by Langer al. (11). Using their reported values, values of SID, Na+ and Cl– were estimated using our models at the average PCO2 values reported in the study and assuming HbO2 = 98%. Absolute values (Supplementary Figure 43) and differences from the reference value at 5% CO2 (Figure 6) show good consistency between our model predictions and the experimental data from that study, reinforcing the physiological plausibility of our approach.

Finally, our study was conducted exclusively on blood from healthy individuals. Thus, results may differ under pathological conditions.

6 Conclusion

Changes in PCO2 in human whole blood lead to a significant shift in the hemoglobin-oxygen dissociation curve (Bohr effect) and markedly alter plasma electrolyte concentrations. The rightward shift of the curve with increasing PCO2 can be effectively modeled using a Gompertz mixed-effects model. In contrast, the changes in plasma electrolyte concentrations, specifically, the reduction in chloride ions and the concurrent increase in sodium levels with rising PCO2, can be described using polynomial mixed-effects models. Understanding and modeling this physiology may help clarify not only the responses of healthy individuals exposed to extreme conditions but also, potentially, those of patients with underlying pathologies.

Statements

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by Comitato Etico-Milano Area 2. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

CV: Writing – original draft, Formal analysis, Conceptualization, Data curation. ElC: Writing – original draft, Formal analysis. MB: Data curation, Writing – review & editing. SC: Conceptualization, Writing – review & editing. EmC: Conceptualization, Writing – review & editing. FG: Conceptualization, Writing – review & editing. TL: Data curation, Writing – original draft, Conceptualization. GG: Funding acquisition, Conceptualization, Writing – review & editing. AZ: Conceptualization, Data curation, Writing – original draft, Formal analysis.

Funding

The author(s) declared that financial support was received for this work and/or its publication. This study was (partially) funded by the Italian Ministry of Health—Current Research IRCCS.

Acknowledgments

We thank Marina Leonardelli (Fondazione IRCCS Ca’ Granda Ospedale Maggiore Policlinico) and Patrizia Minunno (Fondazione IRCCS Ca’ Granda Ospedale Maggiore Policlinico) for their valuable support.

Conflict of interest

The author(s) declared that this work was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declared that generative AI was not used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fmed.2025.1708274/full#supplementary-material

References

1.

Boerema I Meyne N Brummelkamp W Bouma S Mensch M Kamermans F et al [Life without blood]. Ned Tijdschr Geneeskd. (1959) 104:949–54.

2.

Paul Bert’s C . “La pression barométrique” was published 100 years ago [Paul bert’s “la pression barométrique” was published 100 years ago].Ann Anesthesiol Fr. (1979) 20:7–15. French.

3.

Bohr C Hasselbalch K Krogh A . Ueber einen in biologischer Beziehung wichtigen Einfluss, den die Kohlensäurespannung des Blutes auf dessen Sauerstoffbindung übt [On a biologically important influence that the carbon dioxide tension of the blood has on its oxygen binding capacity].Skand Arch Physiol. (1904) 16:402–12. 10.1111/j.1748-1716.1904.tb01382.xGerman

4.

Torrance J Lenfant C . Methods for determination of O2 dissociation curves, including Bohr effect.Respir Physiol. (1969) 8:127–36. 10.1016/0034-5687(69)90050-4

5.

Jensen F . Red blood cell pH, the Bohr effect, and other oxygenation-linked phenomena in blood O2 and CO2 transport.Acta Physiol Scand. (2004) 182:215–27. 10.1111/j.1365-201X.2004.01361.x

6.

Christiansen J Douglas C Haldane J . The absorption and dissociation of carbon dioxide by human blood.J Physiol. (1914) 48:244–71. 10.1113/jphysiol.1914.sp001659

7.

Tyuma I . The Bohr effect and the Haldane effect in human hemoglobin.Jpn J Physiol. (1984) 34:205–16. 10.2170/jjphysiol.34.205

8.

Prange H Shoemaker J Westen E Horstkotte D Pinshow B . Physiological consequences of oxygen-dependent chloride binding to hemoglobin.J Appl Physiol. (2001) 91:33–8. 10.1152/jappl.2001.91.1.33

9.

Westen E Prange HD . A reexamination of the mechanisms underlying the arteriovenous chloride shift.Physiol Biochem Zool. (2003) 76:603–14. 10.1086/380208

10.

Giosa L Zadek F Busana M De Simone G Brusatori S Krbec M et al Quantifying pH-induced changes in plasma strong ion difference during experimental acidosis: clinical implications for base excess interpretation. J Appl Physiol. (2024) 136:966–76. 10.1152/japplphysiol.00917.2023

11.

Langer T Brusatori S Carlesso E Zadek F Brambilla P Ferraris Fusarini C et al Low noncarbonic buffer power amplifies acute respiratory acid-base disorders in patients with sepsis: an in vitro study. J Appl Physiol. (2021) 131:464–73. 10.1152/japplphysiol.00787.2020

12.

di Prisco G Condò S Tamburrini M Giardina B . Oxygen transport in extreme environments.Trends Biochem Sci. (1991) 16:471–4. 10.1016/0968-0004(91)90182-u

13.

Petruzzelli R Aureli G Lania A Galtieri A Desideri A Giardina B . Diving behaviour and haemoglobin function: the primary structure of the alpha- and beta-chains of the sea turtle (Caretta caretta) and its functional implications.Biochem J. (1996) 316:959–65. 10.1042/bj3160959

14.

Tamburrini M Condò S di Prisco G Giardina B . Adaptation to extreme environments: structure-function relationships in Emperor penguin haemoglobin.J Mol Biol. (1994) 237:615–21. 10.1006/jmbi.1994.1259

15.

Giardina B Mosca D De Rosa M . The Bohr effect of haemoglobin in vertebrates: an example of molecular adaptation to different physiological requirements.Acta Physiol Scand. (2004) 182:229–44. 10.1111/j.1365-201X.2004.01360.x

16.

Hamburger H . Anionenwanderungen in Serum und Blut unter dem Einfluss von CO2, Säure Alkali [Anion migrations in serum and blood under the influence of CO2, acid alkali].Biochem Z. (1918) 86:309–24. German.

17.

Lee D Hong J . The fundamental role of bicarbonate transporters and associated carbonic anhydrase enzymes in maintaining ion and pH homeostasis in non-secretory organs.Int J Mol Sci. (2020) 21:339. 10.3390/ijms21010339

18.

Mohandas N Gallagher P . Red cell membrane: past, present, and future.Blood. (2008) 112:3939–48. 10.1182/blood-2008-07-161166

19.

Riggs A . The Bohr effect.Annu Rev Physiol. (1988) 50:181–204. 10.1146/annurev.ph.50.030188.001145

20.

Langer T Scotti E Carlesso E Protti A Zani L Chierichetti M et al Electrolyte shifts across the artificial lung in patients on extracorporeal membrane oxygenation: interdependence between partial pressure of carbon dioxide and strong ion difference. J Crit Care. (2015) 30:2–6. 10.1016/j.jcrc.2014.09.013

21.

Krbec M Waldauf P Zadek F Brusatori S Zanella A Duška F et al Non-carbonic buffer power of whole blood is increased in experimental metabolic acidosis: an in-vitro study. Front Physiol. (2022) 13:1009378. 10.3389/fphys.2022.1009378

22.

Hastings A Salvesen H Sendroy J Van Slyke D . Studies of gas and electrolyte equilibria in the blood.J General Physiol. (1927) 8:701–11. 10.1085/jgp.8.6.701

23.

Wolf M . Mechanisms of whole body, respiratory, acid-base buffering: a first computer-model test of three physicochemical, acid-base theories.J Appl Physiol. (2024) 136:1580–90. 10.1152/japplphysiol.00147.2024

24.

Blumentals A Eichenholz A Mulhausen R . Acid-base equilibria in arterial blood and ascitic fluid.Metabolism. (1966) 15:414–9. 10.1016/0026-0495(66)90082-5

25.

Agrafiotis M . Strong ion reserve: a viewpoint on acid base equilibria and buffering.Eur J Appl Physiol. (2011) 111:1951–4. 10.1007/s00421-010-1803-1

Summary

Keywords

hemoglobin, oxygen, carbon dioxide, electrolytes, physiology, blood, erythrocyte

Citation

Valsecchi C, Carlesso E, Battistin M, Colombo SM, Cattaneo E, Gori F, Langer T, Grasselli G and Zanella A (2026) In vitro characterization of hemoglobin oxygen dissociation curves and electrolyte shifts in human blood under varying PCO2. Front. Med. 12:1708274. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2025.1708274

Received

18 September 2025

Revised

17 November 2025

Accepted

18 December 2025

Published

12 January 2026

Volume

12 - 2025

Edited by

Micah Liam Arthur Heldeweg, Amsterdam University Medical Center, Netherlands

Reviewed by

Mattia Busana, University Medical Center Göttingen, Germany

Swetha N. K, JSS AHER, India

Updates

Copyright

© 2026 Valsecchi, Carlesso, Battistin, Colombo, Cattaneo, Gori, Langer, Grasselli and Zanella.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Alberto Zanella, alberto.zanella1@unimi.it

†These authors share first authorship

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.