Abstract

Background:

Eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis (EGPA) and angioimmunoblastic T-cell lymphoma (AITL) are distinct entities that can present with overlapping clinical features, posing a significant diagnostic challenge. This case highlights a critical diagnostic pitfall where AITL was initially misdiagnosed as EGPA.

Case presentation:

A 55-year-old man presented in 2021 with recurrent wheezing, dyspnea, chronic sinusitis, peripheral eosinophilia (7.35 × 10⁹/L), and skin rash, leading to an initial diagnosis of asthma and later EGPA. Despite treatment with systemic corticosteroids, omalizumab, and mepolizumab, his respiratory symptoms persisted, and lymphadenopathy progressed. A fine-needle lymph node biopsy initially suggested Kimura disease. In 2024, the appearance of a parotid mass prompted further investigation. A subsequent surgical lymph node biopsy in 2025 revealed an effaced nodal architecture with a proliferation of atypical T-cell positive for CD3, CD5, ICOS, and PD-1. T-cell receptor gene rearrangement demonstrated clonality, and Epstein–Barr virus-encoded RNA was detected in situ. These findings confirmed the diagnosis of AITL. Treatment was switched to the CHOP chemotherapy regimen, leading to symptomatic improvement and normalization of eosinophil counts.

Conclusion:

This case underscores that AITL can closely mimic EGPA, presenting with severe asthma, hypereosinophilia, sinusitis, and systemic symptoms. It emphasizes the necessity of considering underlying lymphoma in patients with suspected EGPA who show an atypical or refractory course to conventional therapy. A definitive diagnosis often requires an adequate tissue sample, preferably from a surgical lymph node biopsy, to avoid misdiagnosis and ensure appropriate management. Respiratory physicians should maintain a high index of suspicion for lymphoid malignancies in such complex presentations.

Introduction

Eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis (EGPA) is a rare systemic vasculitis characterized by asthma, chronic rhinosinusitis, peripheral blood eosinophilia, and necrotizing vasculitis. The diagnostic journey is often complex, as its initial presentation, particularly treatment-resistant asthma with hypereosinophilia, can overlap with other conditions such as hypereosinophilic syndrome (HES) and, more rarely, lymphoid malignancies. Angioimmunoblastic T-cell lymphoma (AITL), a subtype of peripheral T-cell lymphoma, is notorious for its paraneoplastic manifestations, which frequently mimic autoimmune or inflammatory disorders, including rash, arthralgia, and hypergammaglobulinemia. The co-occurrence of eosinophilia, while not a classic feature, further blurs the diagnostic boundaries. Herein, we report a challenging case of a patient whose clinical picture was highly suggestive of EGPA but was ultimately diagnosed with AITL, illustrating a critical diagnostic pitfall and emphasizing the necessity of considering underlying lymphoma in refractory cases with eosinophilic predominance.

Case report

Initial presentation (2021)

A 55-year-old man has experienced recurrent intermittent episodes of chest tightness, shortness of breath, and wheezing, accompanied by coughing with expectoration and severe nasal congestion since 2021. He initially presented to a local hospital and underwent chest computed tomography (CT), which revealed multiple areas of bronchial wall thickening with the formation of mucus plugs. Spirometry demonstrated obstructive ventilatory impairment and markedly elevated fractional exhaled nitric oxide (FeNO) 215 ppb. Blood tests revealed eosinophilia (3.41*109 cells/L) and an increased IgE level (116 IU/mL). Based on the above examinations, a preliminary diagnosis of asthma was made. He received budesonide and formoterol fumarate powder for inhalation, omalizumab, and leukotriene receptor antagonists as initial therapies. However, his symptoms did not improve.

First referral (2023) and initial diagnoses

The patient was transferred to our hospital for further evaluation in 2023. On admission, in addition to the above symptoms, he also experienced hearing loss and developed rashes after eating seafood. Blood tests revealed eosinophilia (7.35*109cells/L). A PET/CT scan was performed, showing tonsil enlargement with increased metabolism and multiple lymph nodes with mildly elevated metabolism, spleen enlargement, and pan-sinusitis. The pathological findings after sinusitis surgery indicated a few scattered eosinophils in the nasal mucosal tissue. Bone marrow aspiration revealed eosinophils accounting for 5–10% of the total nucleated cells, and the pathology of the lymph node needle puncture biopsy showed a lymphoid proliferative lesion with mild atypia and numerous eosinophils, consistent with a diagnosis of “Kimura disease.” Regular follow-up examinations are recommended according to consultation with a hematologist. Taken together, the patient was therefore rediagnosed with Kimura disease and eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis (EGPA), according to the 1990 ACR diagnostic criteria. Budesonide/glycopyrronium bromide/formoterol for inhalation, systemic corticosteroids (1 mg/kg/day), omalizumab (600 mg q2w), and mepolizumab (100 mg q4w) were administered.

Treatment failure and new symptoms (2024)

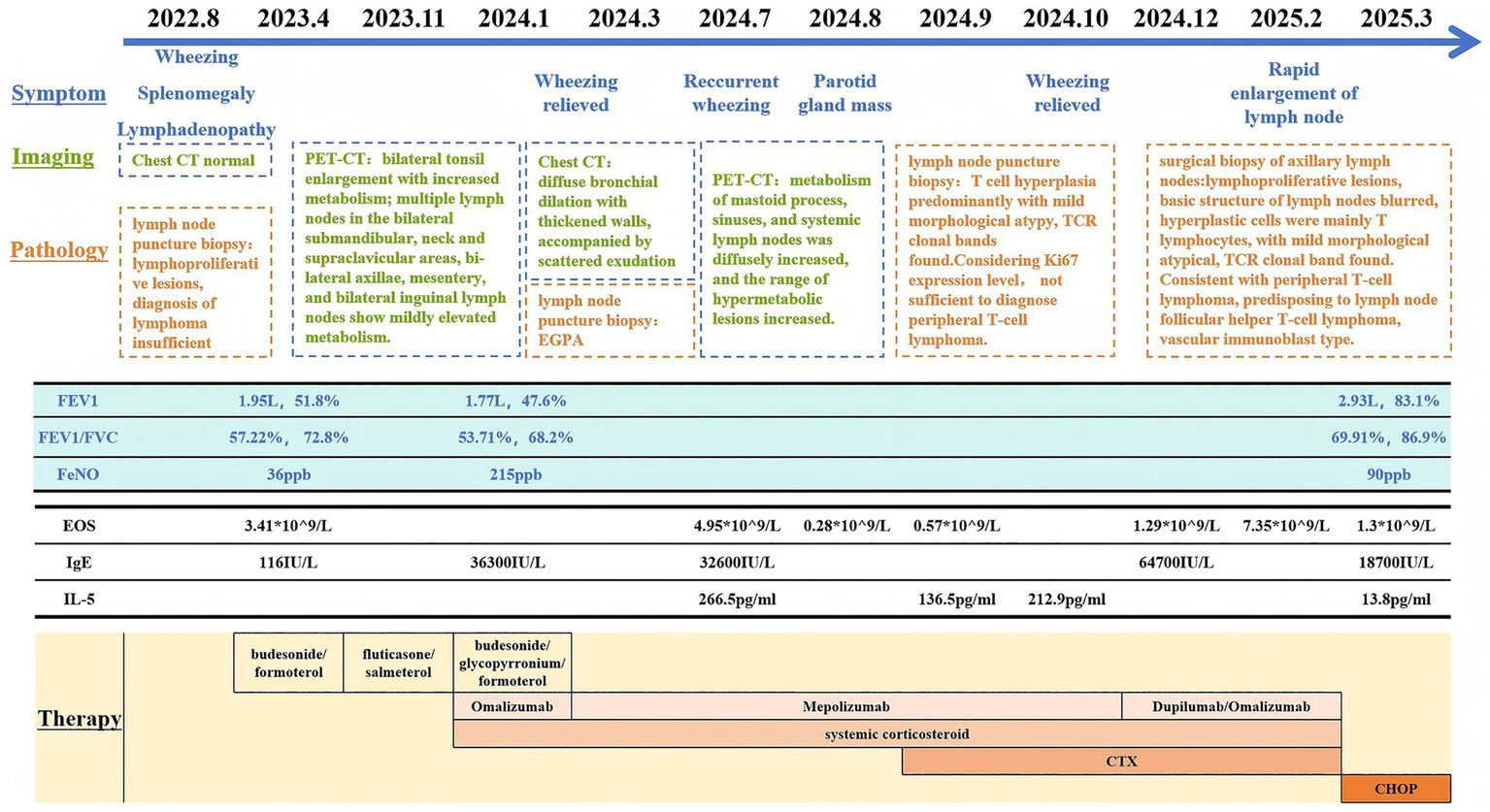

After treatment, his eosinophil count decreased, but his respiratory manifestations were not ameliorated, and the lymphadenopathy did not subside. The patient was readmitted to our hospital due to the appearance of a parotid gland mass in August 2024. Biopsy of the mass was performed, and the histopathological finding was basically consistent with that of the lymph node biopsy. A second lymph node puncture biopsy was performed, and the pathology showed T cell hyperplasia predominantly with mild morphological atypia and TCR clonal bands found, but a low Ki67 expression level (40%). After consultation with a rheumatologist, intravenous cyclophosphamide (0.8 g q4w) was administered. The patient was under regular mepolizumab and CTX treatment from July 2024 to November 2024, and the peripheral eosinophil count was kept normal, but the symptoms fluctuated, and a progressive thickening of the airway wall was noticed on the chest CT scan (Figure 1). Thus, dupilumab was administered in December 2024, and mepolizumab was stopped. Dupilumab (300 mg q2w) was given alternately with omalizumab (600 mg q2w) for 3 months. During this period, the patient’s wheezing symptoms were slightly improved, lung function was improved, and bronchial dilation and airway wall thickening on the CT scan improved as well.

Figure 1

Chest CT scan. Top, chest CT scan in September 2024; bottom, chest CT scan in February 2025.

Definitive diagnosis (2025)

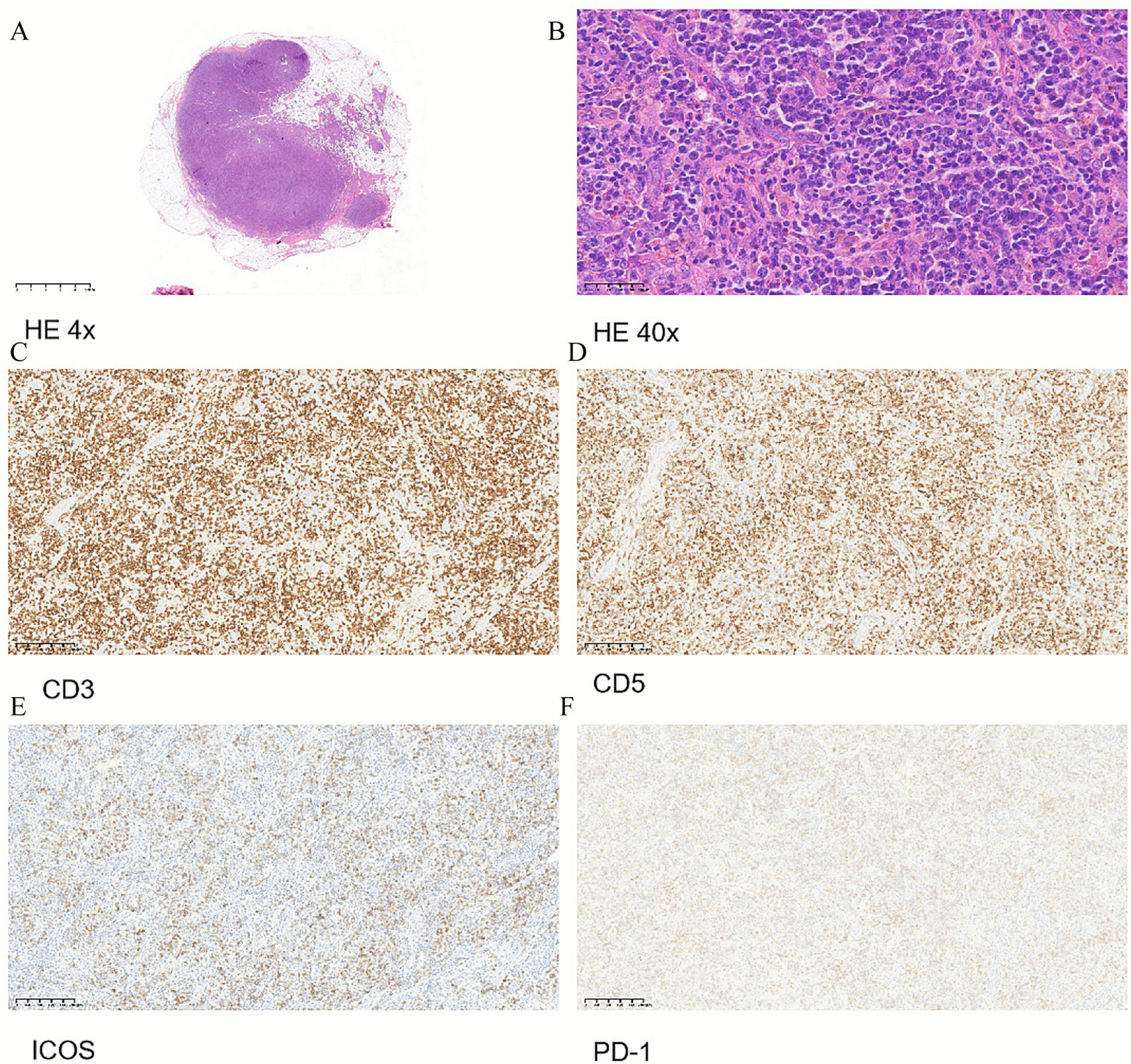

In February 2025, the patient developed a rapid enlargement of superficial lymph nodes, leading to difficulty turning the neck, accompanied by the re-elevation of peripheral blood eosinophils (7.35*109 cells/L). Thus, dupilumab was stopped. Since the patient’s wheezing improved, he tolerated a surgical lymph node biopsy, which was a decisive examination. The pathology of the surgical biopsy completed showed lymphoproliferative lesions with a basic structure of lymph nodes blurred; immunohistochemical markers showed that the hyperplastic cells were mainly T lymphocytes (CD3+, CD5+, CD7+, ICOS+, PD-1+), with mild morphological atypia; the TCR gene rearrangement test showed clonal bands; Epstein–Barr virus-encoded RNA in situ hybridization was positive in a certain proportion of tumor cells (Figure 2). These pathological performances were consistent with peripheral T-cell lymphoma, predisposed to lymph nodes, follicular helper T-cell lymphoma, vascular immunoblast type. The patient was finally diagnosed with angioimmunoblastic T cell lymphoma (AITL) and was treated with the CHOP regimen on 5 March 2025. After several cycles of chemotherapy, the EOS level of the patients still decreased with the interruption of mepolizumab therapy, and the wheezing symptoms were further improved. The patient is now being followed up in the hematology department.

Figure 2

Pathology and immunohistochemistry of lymph node surgical biopsy. (A) HE 4x. (B) HE 40x. (C) Immunohistochemistry of CD3. (D) Immunohistochemistry of CD5. (E) Immunohistochemistry of ICOS. (F) Immunohistochemistry of PD-1.

Discussion

The patient was initially misdiagnosed with asthma, which is a common airway inflammatory disease, but asthmatic symptoms can also be the result of other systemic diseases. EGPA is one of the differential diagnoses for asthma (1). EGPA, formerly known as Churg–Strauss syndrome, is a rare but serious form of vasculitis characterized by the inflammation of small- to medium-sized blood vessels and significant eosinophilia. In our case, the patient showed typical asthmatic symptoms, chest ground-glass opacities, pan-sinusitis, rashes with hypereosinophilia, and was rediagnosed with EGPA after the failure of asthma treatment. However, he did not respond well to corticosteroids and mepolizumab. This led us to dig out the underlying cause of his “asthmatic symptoms.”

There is considerable overlap in clinical presentations between hypereosinophilia syndrome (HES) and EGPA. Distinguishing between the two can be challenging. HES is a rare and complex hematological disorder characterized by persistently elevated levels of eosinophils (>1,500 cells/mL) (2). The pathophysiology of HES is rooted in both primary and secondary causes of eosinophilia. Primary causes of HES are often associated with hematologic malignancies or myeloproliferative disorders (Figure 3 and Table 1).

Figure 3

Timeline of clinical presentation and work-up. PET, Positron emission tomography; FEV1, Forced expiratory volume in 1 s; FVC, Forced vital capacity; FeNO, Fractional exhaled nitric oxide; EOS, Eosinophils; CTX, Cyclophosphamide.

Table 1

| Treatment | Change of clinical manifestation | Change of test results |

|---|---|---|

| Budesonide/Formoterol/Fumarate Powder + systematic corticosteroid |

Wheezing worsened, lymphadenopathy worsened | Eosinophil count elevated, IgE elevated, Spirometry worsened, Chest CT: almost normal |

| Omalizumab | Wheezing worsened, lymphadenopathy worsened, new symptom: rash |

Eosinophil count elevated, IgE elevated, Spirometry worsened, Chest CT:diffuse bronchial dilation with thickened walls, accompanied by scattered exudation |

| Mepolizumab | Wheezing recurrent, lymphadenopathy stable, new symptom: parotid gland mass |

Eosinophil count decreased, IgE elevated, Spirometry did not check, Chest CT: progressive thickening of airway wall |

| Mepolizumab + CTX | Wheezing ameliorated, lymphadenopathy stable, rash subsided, parotid gland mass subsided |

Eosinophil count decreased to normal, IgE elevated, Spirometry did not check, Chest CT: progressive thickening of airway wall |

| Dupilumab | Wheezing ameliorated, but rapid enlargement of lymph node | Eosinophil count re-elevated, IgE kept high, Spirometry improved, Chest CT: bronchial dilation and airway wall thickening improved |

| Chemotherapy | Wheezing ameliorated, lymphadenopathy ameliorated | Eosinophil count decreased to normal, IgE decreased, Spirometry improved, Chest CT: almost normal |

Treatment responses.

The first-line treatment for HES typically involves systemic corticosteroids. Hydroxyurea and imatinib may also be administered, particularly in steroid-refractory cases (3). Research into new treatment modalities is ongoing. Mepolizumab has recently received FDA approval for treating patients aged 12 years and older with HES (4). Benralizumab and dupilumab were also reported to be used in HES patients (5, 6). In this case, our patient’s eosinophil count decreased with mepolizumab, but the symptoms and radiological presentation did not ameliorate. The decrease of eosinophils allowed us to try dupilumab, which should not be used when the eosinophil count is high, and the patient showed a greater response to dupilumab with amelioration of clinical symptoms, spirometry, and chest CT imaging as well. However, the patient showed a quick enlargement of the lymph node and a dangerous re-elevation of peripheral eosinophil count after several injections of dupilumab. It is not clear whether this was related to dupilumab administration.

The patient was finally diagnosed with angioimmunoblastic T cell lymphoma (AITL) by a surgical lymph node biopsy. Clinical symptoms of AITL frequently mimic those of autoimmune or inflammatory disorders, leading to diagnostic challenges and delayed treatment. In our case, based on the initial fine-needle biopsy results, the diagnosis was considered to be Kimura’s disease. However, in retrospect of the entire disease course, the extensive eosinophil infiltration observed in the initial fine-needle aspiration should actually be attributed to the massive proliferation of Tfh cells in AITL and the release of cytokines such as IL-5 and IL-13. The small tissue sample from the fine-needle aspiration biopsy could lead to misinterpretation. There is also the possibility that the progression of the disease itself caused the change in pathological results between the two biopsies. Thus, surgical lymph node biopsy should be performed whenever possible.

One significant aspect of AITL is the involvement of the Epstein–Barr virus (EBV) (7), which is detectable in most patients, and also in our case. The precise role of EBV in AITL development remains unclear; however, it is believed to influence T cell activation and promote the survival of infected cells, thereby aiding in the progression of the disease. Profound immunosuppression due to the progression of AITL induces EBV reactivation in B cells. It is reported that EBV-positive B cells are frequently detected by AITL. Regrettably, we were not able to confirm whether EBV + cells were T cells or B cells in our case.

There are a few reports about misdiagnosis between AITL and EGPA (8, 9). Le Roy et al. (8) reported a 55-year-old woman, who complained of approximately a 1-year history of dry cough and dyspnea evolving into acute exacerbation. Initial blood revealed eosinophilia, and a chest CT-scan showed bilateral reticulonodular and ground-glass opacities. She was diagnosed with EGPA. Her symptoms were partially improved with combined therapies but relapsed after 2 months of follow-up. PET/CT scan showed homogeneous bone marrow and thyroid 18F-FDG uptake, cervical, diffuse hypermetabolic lymph nodes. The biopsy finally revealed AITL. The authors suggested that AITL may mimic EGPA and highlighted the multifaceted clinical presentation and the wide spectrum of other autoimmune manifestations that AITL may mimic. Underlying T-cell lymphoma should be considered in patients with suspected EGPA. Interestingly, Kawauchi et al. (9) reported EGPA may conversely mimic peripheral T-cell lymphoma. His patient was initially diagnosed with lymphoma via partial intestinal resection due to small intestinal perforation but recurred with an elevated eosinophil count. Additional review of the resected ileum revealed fibrinoid necrosis, eosinophilic infiltration, and rupture of the internal elastic laminae in the small- and medium-sized arteries of the submucosal layer, indicating necrotizing vasculitis, and a clonal T-cell population with TCR β gene rearrangement was not detected. Finally, the patient was therefore rediagnosed with EGPA.

Lymphoma is known to be associated with autoimmune diseases, probably related to persistent antigenic stimulation and immunosuppressive medications. Some people believe that B- and T-cell hyperactivity on account of chronic antigenic stimulation seems to play a key role in the pathogenesis of lymphoma. Advanced age at diagnosis, prolonged disease course, and disease severity are thought to increase the risk of lymphoma development in patients with autoimmune disorders, which may be induced by EGPA (10).

In conclusion, we experienced a case of AITL perfectly mimicking EGPA with recurrent asthmatic symptoms, chest ground-glass opacities, pan-sinusitis, rashes, and hypereosinophilia. We report this case to remind respiratory physicians that a thorough work-up and close follow-up are essential for patients with EGPA to eliminate underlying lymphoma, especially when they do not respond well to classic treatments.

Statements

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Ethics statement

Written informed consent was obtained from the individual(s) for the publication of any potentially identifiable images or data included in this article.

Author contributions

YN: Conceptualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. YS: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. SX: Writing – review & editing. JX: Data curation, Writing – review & editing. GS: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Writing – review & editing. RD: Conceptualization, Writing – review & editing. YG: Conceptualization, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declared that financial support was received for this work and/or its publication. This study was funded by the Noncommunicable Chronic Diseases-National Science and Technology Major Project 2024ZD0529805.

Conflict of interest

The author(s) declared that this work was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

The reviewer ZQ declared a past co-authorship with the author GS to the handling editor.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declared that Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript. Generative AI Deepseek was used to improve language expression. Authors verified and took full responsibility for the use of generative AI in the preparation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Abbreviations

EGPA, eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis; AITL, angioimmunoblastic T cell lymphoma; PET, positron emission tomography; FEV1, forced expiratory volume in 1 s; FVC, forced vital capacity; FeNO, fractional exhaled nitric oxide; EOS, eosinophils; CTX, cyclophosphamide; TCR, T-cell receptor; ICOS, inducible costimulatory molecules; PD-1, programmed cell death protein-1; HES, hypereosinophilia syndrome; LHES, lymphocytic hypereosinophilia syndrome; EBV, Epstein–Barr virus.

References

1.

Romero Gómez C Hernández Negrín H Ayala Gutiérrez MDM . Eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis. Granulomatosis eosinofílica con poliangeítis. Med Clin. (2023) 160:310–7. doi: 10.1016/j.medcli.2023.01.003

2.

Szymczyk A Jaworski J Podhorecka M . The challenge of diagnosing and classifying eosinophilia and eosinophil disorders: a review. Cent Eur J Immunol. (2024) 49:60–9. doi: 10.5114/ceji.2024.136512,

3.

Klion AD . How i treat hypereosinophilic syndromes. Blood. (2015) 126:1069–77. doi: 10.1182/blood-2014-11-551614,

4.

Roufosse F Kahn JE Rothenberg ME Wardlaw AJ Klion AD Kirby SY et al . Efficacy and safety of mepolizumab in hypereosinophilic syndrome: a phase III, randomized, placebo-controlled trial. J Allergy Clin Immunol. (2020) 146:1397–405. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2020.08.037,

5.

Ezekwe EAD Jr Weskamp AL Rahim R Makiya MA Wetzler L Ware JAM et al . Dupilumab use in patients with hypereosinophilic syndromes: a multicenter case series and review of the literature. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. (2025) 13:167–175.e6. doi: 10.1016/j.jaip.2024.10.036,

6.

Kuang FL Makiya MA Ware JM Wetzler L Nelson C Brown T et al . Long-term efficacy and safety of Benralizumab treatment for PDGFRA-negative Hypereosinophilic syndrome. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. (2025) 13:1421–1429.e2. doi: 10.1016/j.jaip.2025.03.016,

7.

Xing Y Huang J Zhang Y Wang Y Qi S . Advancing the understanding and management of angioimmunoblastic T-cell lymphoma: insights into its pathogenesis, clinical features, and emerging therapeutic strategies. Front Oncol. (2025) 15:1479179. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2025.1479179,

8.

Le Roy A Terrier B London J Paugam A Mouthon L Lifermann F . Angioimmunoblastic T-cell lymphoma mimicking eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis (Churg-Strauss). Joint Bone Spine. (2019) 86:273–4. doi: 10.1016/j.jbspin.2018.06.002,

9.

Kawauchi M Watanabe T Hattori T Suzuki A Ishizu A Jodo S . Eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis mimicking peripheral T-cell lymphoma, not otherwise specified. Scand J Rheumatol. (2019) 48:171–2. doi: 10.1080/03009742.2018.1493746,

10.

Sena Teixeira Mendes L Wotherspoon A . Marginal zone lymphoma: associated autoimmunity and auto-immune disorders. Best Pract Res Clin Haematol. (2017) 30:65–76. doi: 10.1016/j.beha.2016.07.006

Summary

Keywords

AITL, asthma, EGPA, lymphoma, misdiagnose

Citation

Ni Y, Sun Y, Xie S, Xie J, Shi G, Dai R and Guo Y (2026) Case Report: Angioimmunoblastic T-cell lymphoma initially diagnosed as eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis. Front. Med. 12:1716129. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2025.1716129

Received

30 September 2025

Revised

28 November 2025

Accepted

08 December 2025

Published

22 January 2026

Volume

12 - 2025

Edited by

Giuseppe Fiorentino, Colli Hospital, Italy

Reviewed by

Zhang Qingling, Guangzhou Institute of Respiratory Health, China

Wei Du, Gansu Medical College, China

Updates

Copyright

© 2026 Ni, Sun, Xie, Xie, Shi, Dai and Guo.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Yi Guo, guoyi621@163.com; Ranran Dai, drr11154@rjh.com.cn

†These authors have contributed equally to this work and share first authorship

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.