Abstract

Autoimmune gastritis (AIG) is an under-recognized, corpus-predominant autoimmune loss of oxyntic glands that creates a metaplastic, inflamed field in which hyperplastic polyps are common, while epithelial dysplasia is uncommon but management-defining. We report a 35-year-old woman with corpus-predominant atrophy and three pedunculated polyps removed by endoscopic mucosal resection (EMR); initial pathology called a hyperplastic polyp with focal low-grade dysplasia (LGD). On tertiary review, the background was identified as AIG (corpus-restricted oxyntic atrophy with pseudopyloric, also called oxyntic, metaplasia and mild intestinal metaplasia) and a small polyp-head focus was upgraded to high-grade dysplasia (HGD); margins were negative. Helicobacter pylori was negative on histology/immunohistochemistry and urea breath testing. Targeted serology at index and follow-up showed persistently elevated anti-parietal-cell antibodies and fasting gastrin, with intrinsic-factor antibody negative and vitamin B12 within range. Early follow-up confirmed a healed EMR site with a persistent corpus-predominant background, and a small body polyp that proved to be a hyperplastic polyp without dysplasia. This case highlights that concurrent AIG and HGD shift management from routine post-polypectomy care to definitive excision plus corpus-focused surveillance, and it argues for actively considering AIG when dysplasia is found in a body polyp—and considering dysplasia when AIG is present.

Introduction

Autoimmune gastritis (AIG) is an under-recognized, corpus-predominant autoimmune inflammation of the gastric mucosa that leads to progressive loss of oxyntic glands, hypochlorhydria, and secondary hypergastrinemia (1–3). Although AIG is often under-recognized, it has been linked to various gastric lesions, particularly hyperplastic polyps (4–6).

We report a 35-year-old woman with autoimmune gastritis (AIG) and a hyperplastic polyp, in whom expert pathology identified high-grade dysplasia (HGD) in the polyp following endoscopic mucosal resection (EMR). This case underscores the need for clinicians and pathologists to actively consider AIG when dysplasia is found in gastric polyps and to carefully evaluate for dysplasia in patients with AIG.

Case description

A 35-year-old woman presented with upper-abdominal bloating, dyspepsia, and poor appetite. She reported no long-term medications or proton-pump inhibitor use, and no personal or family history of autoimmune disease. Routine checkups confirmed normal thyroid function, with TSH, FT4 and FT3 within reference ranges, as summarized in Table 1 (7–9).

TABLE 1

| Test | Method | Reference range | Initial (Oct 2024) | Follow-up (May 2025) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gastrin-17, pmol/L | CLIA1 | 1.50–7.50 | 68.91 | 53.36 |

| Anti-parietal cell antibody (PCA-IgG), U/mL | CLIA | <20 | 350.07 | 320.30 |

| Anti-intrinsic factor antibody (IFA), U/mL | CLIA | <20 | < 0.50 | 4.14 |

| 13C-urea breath test (ΔDOB), % | CLIA | <4.0 | 0.6 | NA |

| Hemoglobin (HGB), g/L | Automated CBC2 | 115–150 | 110 | 106 |

| Vitamin B12, pmol/L | CLIA | 141.9–611.2 | 435 | 333.19 |

| Total T3, nmol/L | CLIA | 1.25–2.35 | 2.34 | 1.83 |

| Total T4, nmol/L | CLIA | 75.0–150.0 | 164.96 | 130.76 |

| Thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH), μIU/mL | CLIA | 0.60–4.90 | 1.06 | 1.00 |

Serologic and 13C-urea breath test results at initial presentation and follow-up.

1CLIA, chemiluminescence immunoassay.

2CBC, complete blood count. ΔDOB, delta over baseline; NA, not available. Initial tests were performed at first presentation (October 2024); follow-up tests were performed at repeat evaluation (May 2025). Reference ranges are those of the institutional laboratory. Values in bold are outside the reference range.

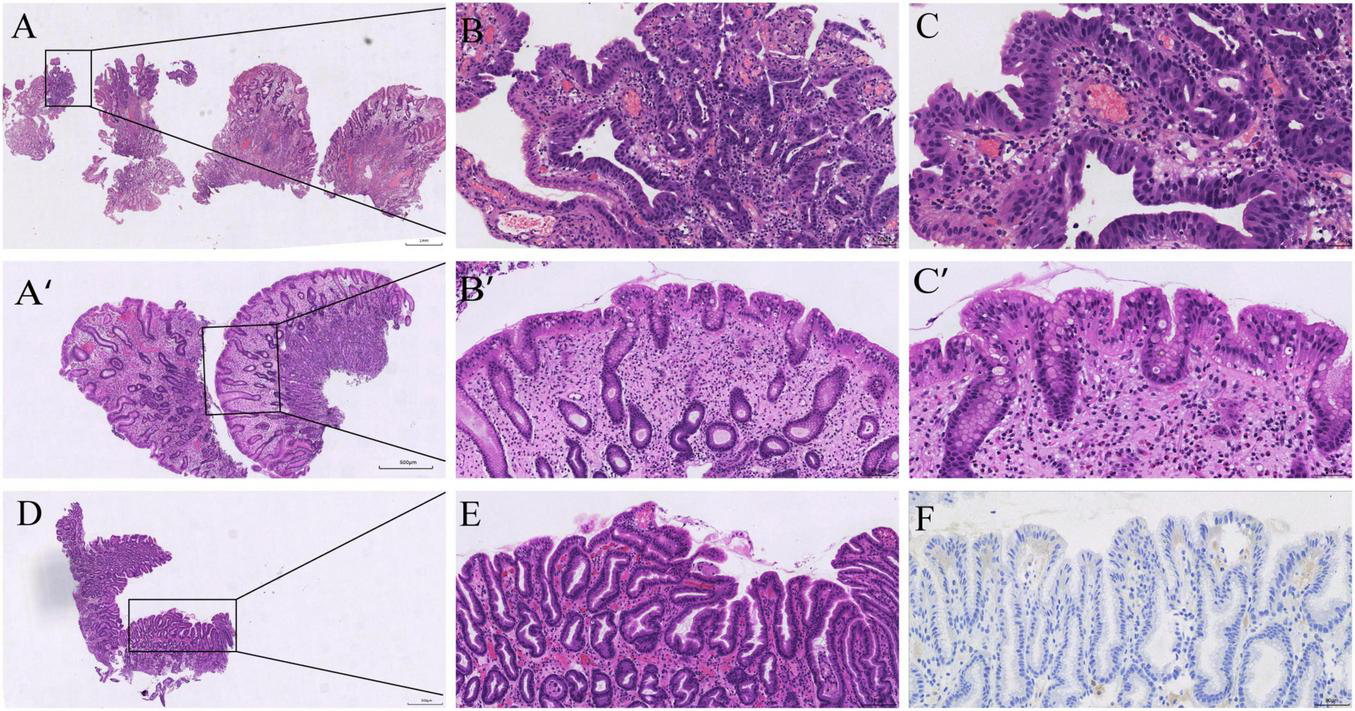

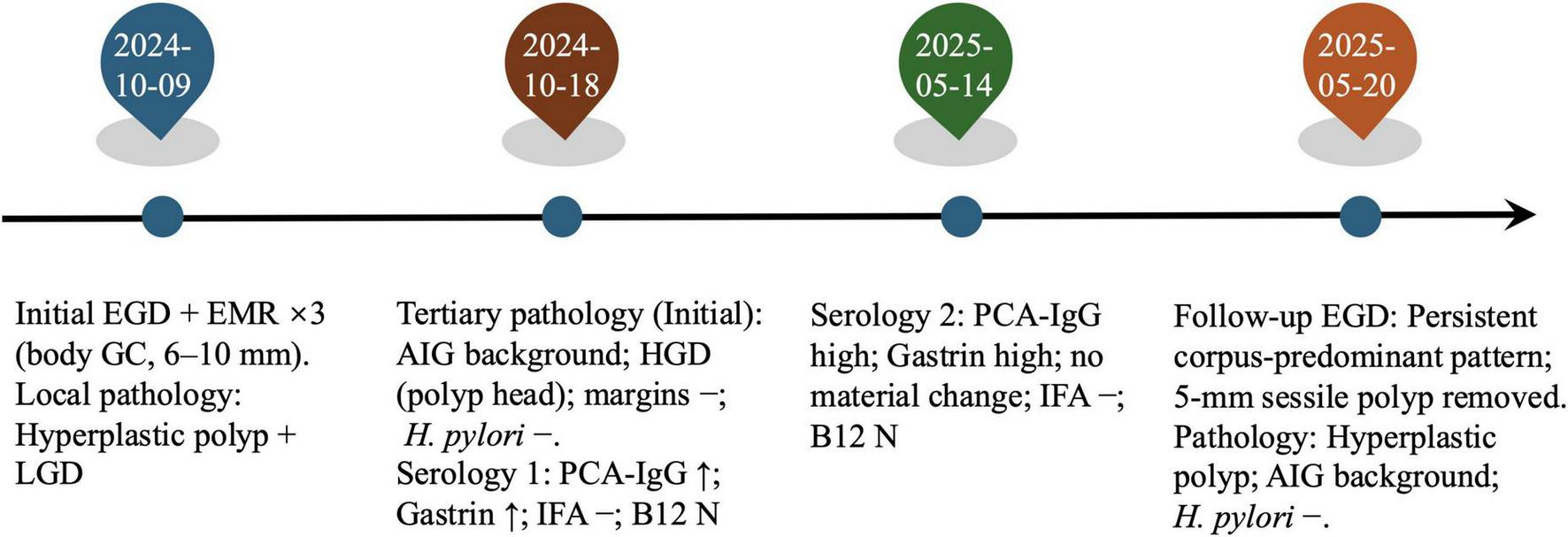

At the initial upper endoscopy, the gastric body showed diffuse punctate erythema with loss of the regular arrangement of collecting venules; three pedunculated polyps (∼6–10 mm) along the lower-body greater curvature were snare-resected en bloc in the same session (Figures 1A–C), and the entire EMR material was submitted for histologic examination, on which local pathology reported hyperplastic polyp with focal low-grade dysplasia (LGD) and did not assign a specific background gastritis. Because the endoscopic appearance suggested a corpus-predominant process in a young patient and the background was not characterized locally, slides were referred to Peking University Third Hospital for expert review. On consultation, the background body mucosa was diagnosed as autoimmune gastritis (AIG) and the polyp-head focus was upgraded to high-grade dysplasia (HGD; Vienna category C4) with negative margins. The AIG diagnosis was supported by diffuse oxyntic gland loss with parietal-cell depletion and replacement by tightly packed pyloric-type mucous glands (pseudopyloric metaplasia), with patchy intestinal metaplasia and relative antral sparing; H. pylori was negative on histology and immunohistochemistry (Figures 2A–C).

FIGURE 1

Initial and follow-up upper endoscopy. (A) Initial endoscopy (white-light imaging, WLI): corpus-predominant atrophic background with multiple pedunculated polyps; the regular arrangement of collecting venules (RAC) is absent. (B) Immediately after endoscopic mucosal resection (EMR) at the initial session: snare electrocautery with a post-resection cautery plume at the polyp stalk. (C) Initial narrow-band imaging (NBI): attenuated pit pattern and prominent subepithelial vessels compatible with oxyntic atrophy. (A’) Follow-up endoscopy (WLI): yellow arrow marks a small polyp along the mid-body greater curvature. (B’) Follow-up (WLI): site of the prior polypectomy showing a well-healed post-EMR scar at the original stalk/base. (C’) Follow-up NBI: persistent corpus-predominant atrophic background with altered pit/vascular architecture.

FIGURE 2

Histopathology from the initial and follow-up procedures. (A–C) Initial endoscopic mucosal resection (EMR) specimen from the gastric body: hyperplastic polyp with a focal high-grade intraepithelial neoplasia (HGD) in the polyp head; the background corpus mucosa shows oxyntic atrophy with pseudopyloric/oxyntic metaplasia and mild intestinal metaplasia (H&E, low→high power). (A’–C’) Follow-up body polyp: hyperplastic polyp without dysplasia on a background compatible with AIG (H&E, low→high power). (D–E) Follow-up antral mapping biopsy: mild chronic gastritis with focal intestinal metaplasia (H&E, low→high power). (F) Helicobacter pylori immunohistochemistry negative (antrum).

At follow-up in May 2025, endoscopy showed a well-healed EMR scar and a persistent corpus-predominant pattern (Figures 1A’–C’). A single ∼5-mm sessile body polyp was removed. Histology again showed a hyperplastic polyp without dysplasia on a body background compatible with AIG (Figures 2A’–C’). Mapping biopsies from the antrum demonstrated mild chronic gastritis without H. pylori on immunohistochemistry (Figures 2D–F).

After histology prompted targeted testing, baseline serology in October 2024 showed gastrin-17 68.91 pmol/L and anti-parietal-cell antibody 350.07 U/mL, while intrinsic-factor antibody was negative and vitamin B12 remained within range. Hemoglobin was 110 g/L, indicating mild anemia. The ^13C-urea breath test was negative (Table 1). These findings supported AIG. At follow-up in May 2025, serology showed no material change (persistently above reference), with intrinsic-factor antibody remaining negative and vitamin B12 within range. No additional therapy was required beyond corpus-focused surveillance. The overall clinical course, including diagnostic evaluations and longitudinal follow-up, is summarized in Figure 3.

FIGURE 3

Timeline@@@ of the clinical course. Initial EGD with endoscopic mucosal resection (EMR) of three body polyps (6–10 mm); local pathology: hyperplastic polyp with focal low-grade dysplasia (LGD). Tertiary review of the initial specimen: corpus-restricted autoimmune gastritis (AIG) and high-grade dysplasia (HGD) in the polyp head; margins negative; H. pylori negative. Targeted serology at baseline and again at follow-up showed persistently high PCA-IgG and fasting gastrin with IFA negative and vitamin B12 within range; mild anemia was present. Follow-up EGD: persistent corpus-predominant pattern; a 5-mm sessile body polyp was removed and read as a hyperplastic polyp on an AIG background; H. pylori immunohistochemistry negative.

Discussion

This case highlights the rare coexistence of AIG and HGD in 35-year-old woman, significantly altering management strategies. Although AIG is frequently associated with benign gastric lesions, the presence of HGD in a hyperplastic polyp is an unusual and clinically significant finding (4, 5). This case underlines the importance of considering AIG as a background condition in patients with gastric polyps and emphasizes the need for a more vigilant approach when dysplasia is detected in such patients (1, 2, 10). This case places the spotlight on comorbidity: HGD arising within a gastric hyperplastic polyp in an AIG field. Understanding how and why these two processes intersect explains both the presentation and the management (2).

Autoimmune gastritis’s pathophysiology involves chronic inflammation and oxyntic gland atrophy, leading to a metaplastic gastric environment that predisposes to polyp formation (1–3, 11). These polyps are typically benign; however, sustained inflammation and repeated regeneration can create diffuse mucosal susceptibility, with cumulative genomic stress that increases the risk of dysplasia (6, 12, 13). Our case suggests that the chronic inflammation and low-acid environment in AIG provide a plausible milieu for this progression, as evidenced by HGD developing within a hyperplastic polyp (5, 11).

Although the gastrin axis in AIG is classically linked to enterochromaffin-like (ECL) cell hyperplasia and type I gastric neuroendocrine tumors, our case suggests that AIG can also foster epithelial neoplasia via an inflammation-metaplasia-dysplasia pathway, resulting in HGD (1, 10, 14). The histologic findings in our patient, particularly pseudopyloric metaplasia with intestinal metaplasia, fit this framework (1, 3). This underscores the need for heightened awareness among clinicians and pathologists regarding the potential for dysplasia in AIG patients, even in seemingly benign lesions such as hyperplastic polyps (5, 15).

Compared with prior reports, high-grade dysplasia within a gastric hyperplastic polyp on an AIG background appears rare, which makes this co-morbidity clinically notable (16, 17). Although direct prospective data linking AIG itself to gastric adenocarcinoma are limited, the American Gastroenterological Association (AGA) Clinical Practice Update on Atrophic Gastritis (2021) classifies advanced atrophic gastritis as a preneoplastic condition and recommends surveillance, and a recent clinical review by Castellana et al. (2) synthesizes evidence that autoimmune atrophic gastritis carries increased neoplastic potential and outlines practical management (2, 15, 18). On this backdrop, our case documents epithelial HGD within a hyperplastic polyp in AIG, reinforcing complete excision and corpus-focused follow-up (10, 15).

This case also highlights the importance of early detection and intervention in patients with AIG and gastric polyps. As dysplasia in these patients may be subtle, expert pathology review is crucial for accurate diagnosis (3, 15). Once HGD is excised with clear margins, the management focus should shift from the polyp itself to the underlying background disease. AIG patients, particularly those with dysplastic lesions, should undergo short-interval re-inspections (6–12 months) with thorough gastric corpus inspection, a lower threshold for endoscopic resection of new lesions, and targeted biopsies to monitor background atrophy and metaplasia (10, 15, 18). In addition to short-interval endoscopic surveillance, longer-term follow-up is planned, including annual endoscopy and periodic serologic monitoring (gastrin, parietal cell antibody, intrinsic factor antibody, vitamin B12, and hemoglobin), in accordance with guideline-based management of AIG.

Future research should focus on better understanding the molecular mechanisms underlying dysplasia in AIG and developing biomarkers for early detection. Additionally, large-scale studies are needed to establish more detailed guidelines for surveillance in AIG patients with gastric polyps, as well as to identify optimal intervention strategies to prevent malignant progression.

Conclusion

This case demonstrates that recognizing AIG as the background disease can be as important as grading the lesion itself. In a young adult with a gastric body hyperplastic polyp, expert pathology identified corpus-restricted AIG and HGD at the polyp head—a combination that immediately changed management from routine post-polypectomy care to definitive excision plus corpus-focused surveillance. The practical lesson is simple: when endoscopy shows a corpus-predominant atrophic pattern with polyps, think AIG, look for pseudopyloric (oxyntic) metaplasia and surface pit hyperplasia, and scrutinize the polyp head for loss of maturation signaling HGD. Anchoring the diagnosis in these field-and-focus principles helps clinicians avoid under-recognition of AIG and ensures that surveillance intensity matches the true biological risk.

Statements

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in this article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Ethics statement

Ethical approval was not required for the study involving humans in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. Written informed consent to participate in this study was not required from the participants or the participants’ legal guardians/next of kin in accordance with the national legislation and the institutional requirements. Written informed consent was obtained from the individual(s) for the publication of any potentially identifiable images or data included in this article. Written informed consent was obtained from the participant/patient(s) for the publication of this case report.

Author contributions

TW: Data curation, Investigation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. JL: Investigation, Writing – review & editing, Validation. YH: Investigation, Methodology, Writing – review & editing, Validation. QY: Supervision, Writing – review & editing, Data curation, Investigation, Resources, Validation. SP: Investigation, Supervision, Writing – review & editing, Data curation, Resources, Validation.

Funding

The author(s) declared that financial support was not received for this work and/or its publication.

Conflict of interest

The author(s) declared that this work was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declared that generative AI was not used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1.

Shah SC Piazuelo MB Kuipers EJ Li D . AGA clinical practice update on the diagnosis and management of atrophic gastritis: expert review.Gastroenterology. (2021) 161:1325–32.e7. 10.1053/j.gastro.2021.06.078

2.

Castellana C Eusebi LH Dajti E Iascone V Vestito A Fusaroli P et al Autoimmune atrophic gastritis: a clinical review. Cancers. (2024) 16:1310. 10.3390/cancers16071310

3.

Kamada T Watanabe H Furuta T Terao S Maruyama Y Kawachi H et al Diagnostic criteria and endoscopic and histological findings of autoimmune gastritis in Japan. J Gastroenterol. (2023) 58:185–95. 10.1007/s00535-022-01954-9

4.

Hu H Zhang Q Chen G Pritchard DM Zhang S . Risk factors and clinical correlates of neoplastic transformation in gastric hyperplastic polyps in Chinese patients.Sci Rep. (2020) 10:2582. 10.1038/s41598-020-58900-z

5.

Zouridis S Michael M Arker SH Sangha M Batool A . Gastric hyperplastic polyps: a narrative review.Digest Med Res. (2023) 6:8. 10.21037/dmr-22-38

6.

Zhang D-X Niu Z-Y Wang Y Zu M Wu Y-H Shi Y-Y et al Endoscopic and pathological features of neoplastic transformation of gastric hyperplastic polyps: retrospective study of 4010 cases. World J Gastrointest Oncol. (2024) 16:4424–35. 10.4251/wjgo.v16.i11.4424

7.

Lahner E Conti L Cicone F Capriello S Cazzato M Centanni M et al Thyro-entero-gastric autoimmunity: pathophysiology and implications for patient management. Best Pract Res Clinical Endocrinol Metab. (2020) 34:101373. 10.1016/j.beem.2019.101373

8.

Miceli E Vanoli A Lenti MV Klersy C Stefano MD Luinetti O et al Natural history of autoimmune atrophic gastritis: a prospective, single centre, long-term experience. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. (2019) 50:1172–80. 10.1111/apt.15540

9.

Banks M Graham D Jansen M Gotoda T Coda S Di Pietro M et al British Society of Gastroenterology guidelines on the diagnosis and management of patients at risk of gastric adenocarcinoma. Gut. (2019) 68:1545–75. 10.1136/gutjnl-2018-318126

10.

Imura J Hayashi S Ichikawa K Miwa S Nakajima T Nomoto K et al Malignant transformation of hyperplastic gastric polyps: an immunohistochemical and pathological study of the changes of neoplastic phenotype. Oncol Lett. (2014) 7:1459–63. 10.3892/ol.2014.1932

11.

Orgler E Dabsch S Malfertheiner P Schulz C . Autoimmune gastritis: update and new perspectives in therapeutic management.Curr Treat Options Gastroenterol. (2023) 21:64–77. 10.1007/s11938-023-00406-4

12.

Vavallo M Cingolani S Cozza G Schiavone FP Dottori L Palumbo C et al Autoimmune gastritis and hypochlorhydria: known concepts from a new perspective. Int J Mol Sci. (2024) 25:6818. 10.3390/ijms25136818

13.

Reyes-Placencia D Cantú-Germano E Latorre G Espino A Fernández-Esparrach G Moreira L . Gastric epithelial polyps: current diagnosis, management, and endoscopic frontiers.Cancers. (2024) 16:3771. 10.3390/cancers16223771

14.

Murphy JD Gadalla SM Anderson LA Rabkin CS Cardwell CR Song M et al Autoimmune conditions and gastric cancer risk in a population-based study in the United Kingdom. Br J Cancer. (2024) 131:138–48. 10.1038/s41416-024-02714-7

15.

Pimentel-Nunes P Libânio D Marcos-Pinto R Areia M Leja M Esposito G et al Management of epithelial precancerous conditions and lesions in the stomach (MAPS II): European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ESGE), European Helicobacter and Microbiota Study Group (EHMSG), European Society of Pathology (ESP), and Sociedade Portuguesa de Endoscopia Digestiva (SPED) guideline update 2019. Endoscopy. (2019) 51:365–88. 10.1055/a-0859-1883

16.

Yamanaka K Miyatani H Yoshida Y Ishii T Asabe S Takada O et al Malignant transformation of a gastric hyperplastic polyp in a context of Helicobacter pylori-negative autoimmune gastritis: a case report. BMC Gastroenterol. (2016) 16:130. 10.1186/s12876-016-0537-x

17.

Xing Y Han H Wang Y Sun Z Wang L Peng D et al How to improve the diagnosis of neoplastic transformation of gastric hyperplastic polyps in the context of autoimmune gastritis?: A case report and lierature review. Medicine. (2022) 101:e32204. 10.1097/MD.0000000000032204

18.

Shah SC Wang AY Wallace MB Hwang JH . AGA clinical practice update on screening and surveillance in individuals at increased risk for gastric cancer in the United States: expert review.Gastroenterology. (2025) 168:405–16.e1. 10.1053/j.gastro.2024.11.001

Summary

Keywords

autoimmune gastritis, corpus-predominant gastritis, gastric hyperplastic polyp, high-grade dysplasia (hgd), hypergastrinemia

Citation

Wang T, Luo J, Han Y, Yang Q and Peng S (2026) Case Report: Concurrent autoimmune gastritis and high-grade dysplasia in a gastric hyperplastic polyp. Front. Med. 12:1716969. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2025.1716969

Received

01 October 2025

Revised

11 November 2025

Accepted

22 December 2025

Published

12 January 2026

Volume

12 - 2025

Edited by

Dan-Lucian Dumitraşcu, University of Medicine and Pharmacy Iuliu Hatieganu, Romania

Reviewed by

Ludovico Abenavoli, Magna Graecia University, Italy

Yang Yao, The First Affiliated Hospital of Xi’an Jiaotong University, China

Updates

Copyright

© 2026 Wang, Luo, Han, Yang and Peng.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Qiu Yang, yang.qiu@szhospital.comShusong Peng, 13713693611@163.com

†These authors have contributed equally to this work and share first authorship

‡These authors share last authorship

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.