Abstract

Background:

Diabetic kidney disease (DKD) remains a leading cause of end-stage renal disease (ESRD) worldwide. Understanding of DKD pathogenesis has undergone a pivotal shift, moving beyond traditional metabolic and hemodynamic paradigms to underscore the critical role of chronic inflammation.

Objective:

This review aims to systematically delineate recent advances in the inflammatory mechanisms of DKD and to discuss their translational implications. It will focus on emerging diagnostic biomarkers and novel inflammation-targeted therapeutic strategies.

Main content:

This review portrays the complex interplay of emerging inflammatory mechanisms in DKD, encompassing inflammatory pathway activation, cellular senescence, impaired podocyte autophagy, the gut microbiota-kidney axis, and regulation by non-coding RNAs (ncRNAs). Meanwhile, a novel diagnostic paradigm powered by omics technologies and artificial intelligence (AI) is described, highlighting the associated biomarkers. Lastly, the therapeutic landscape, focusing on agents with proven renal benefits, including sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 (SGLT2) inhibitors, non-steroidal mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists (ns-MRAs), and glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists (GLP-1RAs) is reviewed, with evaluating the promise of natural products as multi-target interventions.

Conclusion:

Inflammation in DKD is driven by an intricate network of local and systemic factors. A multifaceted approach which prioritizes the integration of multi-omics data for inflammatory subtyping, deciphering inter-organ communication, and developing combined therapies that leverage conventional drugs, targeted agents, and natural compounds should be adopted to advance the management of DKD.

1 Introduction

Diabetic kidney disease (DKD) is a leading cause of chronic kidney disease (CKD) and end-stage renal disease (ESRD) worldwide, affecting approximately 20%−40% of individuals with diabetes (1). As the global prevalence of diabetes continues to rise, the burden of DKD increases substantially. It poses a major public health challenge that severely compromises patients' quality of life and survival (2). Traditionally, the pathogenesis of DKD has been attributed to two core mechanisms, metabolic dysregulation and hemodynamic abnormalities (3, 4). Hyperglycemia induces renal cell injury through multiple metabolic pathways, including activation of the polyol pathway, formation of advanced glycation end products (AGEs), activation of protein kinase C (PKC), and upregulation of the hexosamine pathway. Concurrently, hemodynamic changes—particularly dilation of afferent arterioles and constriction of efferent arterioles—create a state of high perfusion, high pressure, and high filtration (the “triple high” state) within the glomerulus. “Triple high” state subsequently accelerates glomerulosclerosis and functional deterioration (5, 6). These two mechanisms intertwine to form the classic pathophysiological foundation of DKD.

However, the clinical diagnosis and management of DKD remain difficult. Although renin–angiotensin–aldosterone system (RAAS) inhibitors are widely used as the cornerstone therapy, a significant “ceiling effect” is observed, with many patients continuing to experience disease progression (7). Moreover, DKD exhibits considerable heterogeneity, and its pathogenesis extends beyond the traditional metabolic and hemodynamic paradigms. Current diagnostic approaches, which rely on urinary protein and estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR), often detect abnormalities only after irreversible structural kidney damage has occurred, thereby missing the optimal window for intervention (8). These clinical challenges emphasize the urgent need to explore pathogenic mechanisms beyond the traditional metabolic and hemodynamic paradigms. In this context, chronic low-grade inflammation has emerged as a crucial mechanism spanning the entire course of DKD.

Accumulating evidence indicates that chronic inflammation, triggered jointly by hyperglycemia, AGEs, and hemodynamic stress, interacts with fibrosis, cellular senescence, and other emerging pathways to form a complex pathophysiological network in DKD. Exploring these novel mechanisms and develop corresponding early diagnostic tools and targeted therapies is essential for overcoming current bottlenecks in DKD management. Notably, the pathogenesis of DKD should not be viewed as an isolated progress in the kidney. Diabetes is fundamentally a systemic metabolic disorder characterized by a chronic low-grade inflammatory state, with complications exhibiting typical panvascular features. Therefore, DKD can be regarded as the renal manifestation of diabetic panvascular disease, sharing common pathological features—such as endothelial dysfunction, oxidative stress, and chronic inflammation—with diabetic cardiovascular disease and retinopathy (9). This perspective highlights the intrinsic connections among organ-specific complications and provides a theoretical foundation for therapies with dual cardiorenal benefits, such as sodium–glucose cotransporter 2 (SGLT2) inhibitors. Furthermore, renal inflammatory injury arises not only from the activation of intrinsic renal cells but also remotely from extrarenal chronic inflammatory conditions, such as periodontitis, via “organ–organ crosstalk” (10).

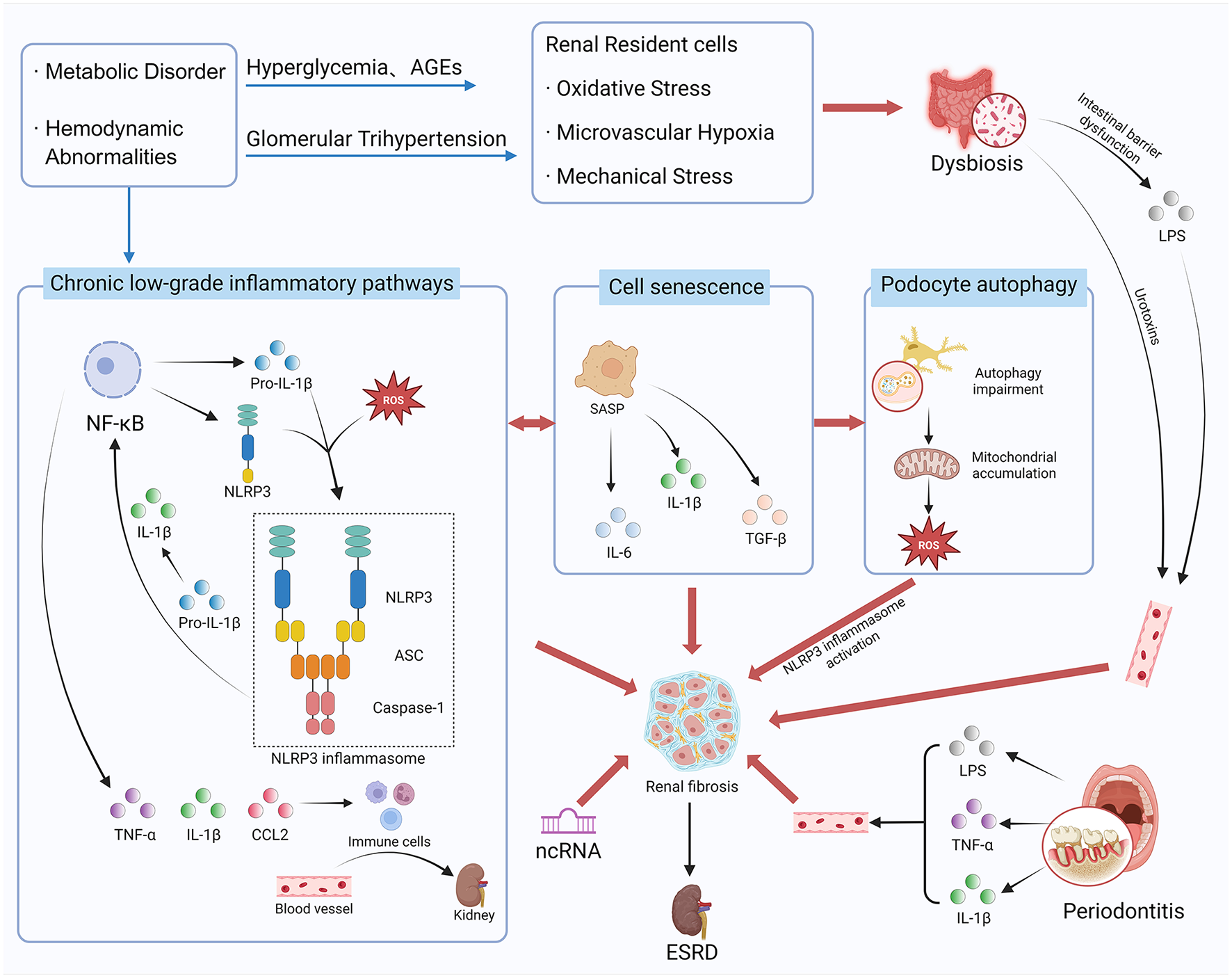

Inflammation in DKD constitutes a complex network driven by both local and systemic factors (Figure 1). This review will delineate key inflammatory mechanisms—including the activation of inflammatory pathways, cellular senescence, impaired podocyte autophagy, gut microbiota-kidney axis, and non-coding RNAs (ncRNAs) regulation—within the broader context of systemic inflammation and panvascular disease. It will also systematically characterize recent advance in diagnostic technologies based on multi-omics and artificial intelligence (AI). Last but not the least, emerging therapeutic strategies such as SGLT2 inhibitors, non-steroidal mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists (ns-MRAs) (e.g., Finerenone), glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists (GLP-1RAs), and natural products with multi-target potential will be summarized and discussed. Overall, this review aims to bridge bench-side discoveries with bedside applications, providing a translational perspective for the development of precision medicine in DKD management.

Figure 1

The complex pathogenesis network of diabetic kidney disease (DKD). Created with BioRender.com.

2 Emerging pathogenesis

2.1 Inflammatory pathway activation

Persistent hyperglycemia, metabolic dysregulation (e.g., AGEs), and hemodynamic alterations collectively stimulate intrinsic renal cells (e.g., podocytes, mesangial cells) and induce microvascular hypoxia (11). These stress signals, through pattern recognition receptors (e.g., TLRs), activate classic inflammatory pathways such as NF-κB and JAK/STAT (12, 13). Subsequently, local renal production of chemokines (e.g., CCL2) and pro-inflammatory factors (e.g., IL-1β, TNF-α) (14) recruit immune cells like monocytes/macrophages and directly damage the glomerular filtration barrier, inducing tubular epithelial cell transdifferentiation (3). Crucially, pro-inflammatory factors also function as potent pro-fibrotic mediators. They directly up-regulate the expression of transforming growth factor-β1 (TGF-β1) in renal resident cells and activate its downstream Smad signaling pathway, tightly coupling inflammation with fibrosis (15). The NOD-like receptor family pyrin domain containing 3 (NLRP3) inflammasome, comprising NLRP3, caspase-1, and apoptosis-associated speck-like protein containing a caspase recruitment domain (ASC), has been identified as a pivotal hub linking metabolic risk factors to the formation and release of IL-1β (16). Furthermore, abnormal activation of the adaptive immunity, particularly involving Th17 cells, exacerbates tissue injury (17). Chronic, low-grade inflammation and associated renal fibrosis represent a key mechanism in DKD progression.

Importantly, inflammatory pathways outlined above do not operate in isolation, they form a tightly interwoven and mutually amplifying regulatory network. Among these, the crosstalk between NF-κB and the NLRP3 inflammasome is particularly critical. NF-κB activation provides the “priming” signal for NLRP3 inflammasome activation by upregulating the transcriptional expression of NLRP3 and pro-IL-1β, preparing the ground for inflammasome assembly. Subsequently, upon a second signal [e.g., ATP, reactive oxygen species (ROS), or crystalline substances], the NLRP3 inflammasome becomes fully activated, catalyzing the cleavage of pro-IL-1β into mature IL-1β and facilitating its massive release. IL-1β, in turn, acts as a potent pro-inflammatory cytokine that can further trigger NF-κB signaling, forming a positive feedback loop that dramatically amplifies the inflammatory response (18–20). Notably, the precise hierarchical relationships and relative contributions of this crosstalk within different renal resident cells and infiltrating immune cells remain incompletely understood. Therefore, deciphering this regulatory network at a cell-specific level represents a key challenge and a priority for future research in this field.

Beyond intrarenal inflammation, systemic chronic inflammation also significantly contributes to DKD progression. A prime example is the inflammatory crosstalk along the oral-systemic axis. Periodontitis, a common chronic inflammatory oral disease, harbors a dysbiotic microbiome that serves as a persistent source of pro-inflammatory mediators. This reservoir releases factors such as lipopolysaccharides (LPS), IL-1β, and TNF-α into the circulation, exacerbating the systemic inflammatory burden in diabetic patients. Circulating inflammatory factors subsequently aggravate renal endothelial dysfunction and inflammatory responses, establishing an “oral-renal axis” that accelerates DKD progression (21–23). Hence, renal inflammation in DKD is an integrated process driven by both local and systemic factors.

2.2 Cellular senescence

Senescent cells refer to intrinsic renal cells that enter an irreversible state of growth arrest following prolonged exposure to stressors such as high glucose levels (24). Unlike traditional apoptosis, senescent cells do not die but instead transform into a senescence-associated secretory phenotype (SASP), continuously releasing large amounts of inflammatory mediators, chemokines, and pro-fibrotic factors. Hence, they create a chronic low-grade inflammatory and fibrotic network within the local microenvironment (25). This state not only directly impairs renal cell function (e.g., podocyte detachment), but also “contaminates” the surrounding healthy cells through paracrine effects, accelerating glomerulosclerosis, and renal interstitial fibrosis (26). Thus, cellular senescence is regarded as a critical bridge linking metabolic stress to the clinical-pathological alterations in DKD. “Anti-senescence therapies” facilitating senescent cell clearance have emerged as a highly promising new strategy for DKD.

2.3 Impaired podocyte autophagy

As highly differentiated terminal cells, podocytes are central to maintaining the glomerular filtration barrier. Injury or loss of podocytes represents a key event in glomerular filtration barrier disruption. In recent years, autophagy has gained attention as a critical mechanism for preserving podocyte homeostasis. Autophagy enables cells to degrade damaged components under stress, thereby maintaining energy balance and supporting intracellular quality control (27). Under diabetic conditions, however, persistent hyperglycemia, metabolic dysregulation, and oxidative stress suppress autophagic flux in podocytes. Consequently, dysfunctional organelles, such as damaged proteins and mitochondria, accumulate due to ineffective clearance (28). In the meantime, impaired autophagy promotes podocyte apoptosis, epithelial-mesenchymal transdifferentiation, and detachment, ultimately compromising the structural and functional integrity of the filtration barrier (29). Furthermore, autophagy-deficient podocytes accumulate damaged mitochondria, resulting in excessive ROS production that in turn activates inflammatory pathways, including the NLRP3 inflammasome described above (30–32). This mechanism closely links metabolic stress to local renal inflammation. Therefore, restoring podocyte autophagy has emerged as a promising therapeutic strategy for DKD. Interventions aimed at enhancing autophagic activity—whether by pharmacological or genetic means—may help to clear cytotoxic aggregates and protect podocytes from hyperglycemia-induced injury.

2.4 Gut microbiota-kidney axis

The gut microbiota-kidney axis has emerged as a concept of considerable interest in understanding the pathogenesis of DKD, suggesting a bidirectional communication network between the intestinal microbial ecosystem and renal physiology. In diabetic conditions, persistent hyperglycemia and dietary modifications frequently drive gut microbiota dysbiosis which is characterized by a diminished abundance of beneficial bacteria and an expansion of opportunistic pathogens (33). Several interconnected mechanisms are proposed for renal injury contributed by gut microbiota dysbiosis.

Firstly, dysbiotic microbiota enhance the production of harmful metabolites, including indole-3-sulfate and p-cresol sulfate. Upon entering the systemic circulation, these uremic toxins accumulate in the kidneys, where they promote oxidative stress, inflammation, and fibrosis (34). Secondly, dysbiosis impairs intestinal barrier function, facilitating the translocation of endotoxins such as LPS into the bloodstream. Consequently, persistent, low-grade systemic inflammation that accelerates DKD progression is triggered (35). Moreover, declining renal function further impedes the excretion of harmful metabolites and endotoxins, intensifying dysbiosis and establishing a self-sustaining vicious cycle. Targeted modulation of the gut microbiota—through prebiotics, probiotics, or dietary intervention—has gained attention as a promising therapeutic strategy to slow DKD progression by acting upon this mechanism. Several natural products have shown potential in modulating this axis. For example, studies indicate that medicinal herbs such as rhubarb and astragalus can reshape gut microbial composition. Subsequent reduction of uremic toxins mitigates renal inflammation and oxidative injury (36, 37). Evidence for promising treatment suggests the gut-kidney axis is a pivotal and actionable target in DKD.

2.5 Regulation by ncRNAs

The regulatory roles of ncRNAs constitute an emerging and rapidly advancing frontier in DKD pathogenesis research. Among them, microRNAs (miRNAs), long non-coding RNAs (lncRNAs), and circular RNAs (circRNAs) collectively establish a complex regulatory network. miRNAs such as miR-21, miR-29a, and miR-802 contribute to the regulation of inflammation, fibrosis, and apoptosis in renal cells through direct targeting of key mRNAs (38–40). For example, elevated miR-802 expression is associated with renal inflammation and fibrosis. Hence, miR-802 has the potential to be used as both diagnostic biomarker and therapeutic target. LncRNAs and circRNAs frequently operate as competitive endogenous RNAs that function as “molecular sponges,” sequestering specific miRNAs and thereby alleviating miRNA-mediated repression of target genes to modulate disease progression (41). In DKD, several circRNAs—including circRNA LDL receptor related protein 6 and circ_0000064—have been implicated in mediating podocyte injury, mesangial cell hypertrophy, and tubulointerstitial fibrosis via regulation of miRNA and protein expression (42). To elaborate specific roles of lncRNAs, up-regulation of lncRNA ISG20 exacerbates renal fibrosis (43). In the meantime, lncRNA NEAT1 promotes tubular epithelial cell injury through regulation of mitophagy (43). Furthermore, downregulation of lncRNA MALAT1 confers protection to podocytes under hyperglycemic conditions (43). Owing to their tissue-specific expression and detectability, ncRNAs not only provide novel insights into pathogenesis of DKD but also exhibit considerable promise as early biomarkers and targets for RNA-based therapeutics.

3 Cutting-edge diagnostic technologies and biomarkers

In recent years, the diagnosis and treatment of DKD have entered a new era of precision medicine. On one hand, leveraging high-throughput technologies such as proteomics and metabolomics, researchers have successfully identified multiple novel biomarkers (such as specific urinary protein fragments and circulating metabolites) that hold promise for earlier, more specific risk prediction and disease staging (44, 45). Simultaneously, AI technologies are being deeply integrated into renal imaging analysis, enabling intelligent recognition of subtle pathological features within medical images and significantly enhancing diagnostic efficiency and objectivity (46, 47). The convergence of these cutting-edge technologies collectively advances the early detection and personalized intervention of DKD.

3.1 Omics-based novel biomarkers

The rapid advancement of high-throughput omics technologies has revolutionized early diagnosis and precision intervention in DKD. Unlike traditional approaches that rely on relatively delayed indicators, proteomics and metabolomics enable unbiased, systematic screening of thousands of molecular alterations in patients' biofluids (e.g., urine and blood), which reveals disease-specific signatures at earlier pathological stages (48, 49). For instance, proteomic studies have identified specific collagen degradation fragments (e.g., type III collagen C-terminal peptides) and extracellular matrix-related proteins in urine, changes in which often precede the clinical detection of microalbuminuria and signal the initiation of renal fibrosis (50). Metabolomics, on the other hand, elucidates complex disturbances in systemic energy metabolism networks. It identifies gut microbiota-derived metabolites such as indoxyl sulfate and p-cresyl sulfate. It also detects disruptions in carnitine metabolism and TCA cycle intermediates linked to mitochondrial dysfunction. These molecules not only serve as indicators of renal injury but may also actively contribute to disease pathogenesis (51, 52).

The value of these novel omics-derived biomarkers extends beyond ultra-early risk prediction. They also help define distinct molecular subtypes of DKD, providing a robust scientific basis for personalized prognosis assessment, targeted drug development, and dynamic monitoring of therapeutic response. Together, these capabilities are steering the field toward the era of precision medicine. Importantly, the molecular subtypes delineated by these biomarkers frequently correlate with the activation of specific inflammatory pathways. For example, certain biomarker profiles may indicate an inflammatory subtype dominated by the NLRP3-IL-1β axis, whereas others may reflect inflammatory patterns driven by TNF-α or CCL2 (53). Omics-guided “inflammatory subtyping” strategy establishes a theoretical foundation for achieving precision anti-inflammatory therapy tailored to specific inflammatory cascades. A summary of representative novel biomarkers discovered via omics technologies is provided in Table 1.

Table 1

| Biomarker category | Specific examples | Source | (Patho)physiological significance/associated pathways | Clinical potential | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Protein | C-terminal propeptide of type III collagen and other extracellular matrix (ECM) fragments | Urine | Reflects early activation of renal fibrogenesis and ECM turnover; fibrosis is closely associated with TGF-β signaling and chronic inflammation. | Serves as an early biomarker of fibrosis, potentially detectable before the onset of microalbuminuria. | (50) |

| Metabolite | Indoxyl sulfate, p-cresyl sulfate | Serum/Urine | Gut microbiota-derived uremic toxins; induce oxidative stress and activate inflammatory pathways such as the NLRP3 inflammasome and NF-κB. | Connects the “gut-kidney axis”; potential utility for risk stratification and monitoring response to interventions. | (51) |

| Metabolite | TCA cycle intermediates, Acylcarnitines | Serum/Urine | Indicates mitochondrial dysfunction and impaired fatty acid oxidation; mitochondrial damage is a key source of reactive oxygen species (ROS) and can trigger inflammation (e.g., via NLRP3). | Aids in identifying metabolic subtypes of DKD and may improve prognostic evaluation. | (52) |

Representative novel biomarkers for DKD discovered by omics technologies.

3.2 Applications of bioinformatics and AI in diagnosis

The synergistic application of bioinformatics and AI is advancing diagnosis of DKD through several distinct technical pathways. In bioinformatics, it is demonstrated through the in-depth analysis of multi-omics data. Integration of genomic, metabolomic, and proteomic datasets enables the construction of molecular interaction networks. For example, KEGG and GO enrichment analyses help identify fibrosis-related pathways and energy metabolism pathways that are activated in early-stage DKD (54). From a methodological standpoint, techniques such as liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (LC-MS) facilitate the quantification of thousands of metabolites in urine samples (55). When coupled with machine learning algorithms (e.g., random forests), bioinformatics helps identify diagnostically informative combinations of characteristic metabolites (e.g., specific ratio alterations between tricarboxylic acid cycle intermediates and gut microbiota-derived metabolites) (46). Integrative analysis using both bioinformatics and AI not only aids in biomarker discovery but also contributes to the stratification of DKD into distinct molecular subtypes.

In the realm of AI, its impact is particularly evident in medical image analysis and predictive modeling. Deep learning-based systems, including convolutional neural networks, are now capable of automatically segmenting and quantitatively analyzing renal ultrasound images (56). These systems precisely measure kidney dimensions and volume while extracting textural features of the renal cortex through techniques like gray-level co-occurrence matrix analysis, translating subjective “echogenicity” into objective quantitative metrics. More importantly, AI enables the development of multimodal fusion models, algorithms such as gradient-boosting decision trees can be trained using diverse inputs, including imaging-derived features (e.g., cortical thickness), clinical parameters (e.g., urine protein-to-creatinine ratio), and omics-based biomarkers (57). Such models not only assist in diagnosis but also support personalized prognosis prediction. For instance, it can accurately estimate a patient's risk of experiencing a >50% decline in eGFR within 3 years.

In summary, bioinformatics extracts key molecular insights from large-scale datasets, while AI integrates these features with clinical and imaging data to build practical tools for precision diagnosis and prognostication. Synergistic use of bioinformatics and AI provides a concrete technical framework for early DKD detection and individualized intervention. Critically, the combined use of bioinformatics and AI is shifting DKD diagnosis from reliance on conventional markers toward a multi-omics driven precision prediction model that incorporates inflammatory signatures. Through the construction of multimodal fusion models, future applications may enable non-invasive, dynamic assessment of inflammatory activity and disease trajectory in patients. This prospect offers unprecedented support for the precise selection of anti-inflammatory treatment timing and targets, as well as for real-time monitoring of therapeutic response.

4 New advances in treatment

In recent years, SGLT2 inhibitors and ns-MRAs (e.g., Finerenone) have emerged as novel therapeutic strategies with significant renoprotective benefits. Their mechanisms extend beyond conventional glycemic or blood pressure control, with anti-inflammatory and antifibrotic properties representing core components of their efficacy. SGLT2 inhibitors alleviate glomerular hypertension and hyperfiltration by inhibiting the tubular reabsorption of glucose and sodium. They also improve mitochondrial function and reduce oxidative stress, suppressing inflammatory responses at the level of energy metabolism (58). On the other hand, Finerenone as a ns-MRA directly targets the overactivated mineralocorticoid receptor (MR) which is persistently stimulated by hyperglycemia and other risk factors in DKD. Activation of MRs leads to upregulation of pro-inflammatory and pro-fibrotic genes. By antagonizing MRs, Finerenone directly attenuates renal inflammation and fibrosis. It also confers multiple vascular and renal protective effects. For example, Finerenone is found to reduce endothelial cell apoptosis, inhibit smooth muscle cell proliferation, and limit inflammatory responses following vascular injury, facilitating endothelial repair and preventing maladaptive vascular remodeling (59).

In addition to theoretical feasibility, therapeutic value of both SGLT2 inhibitors and ns-MRAs is supported by robust clinical evidence. Both the CREDENCE trial (SGLT2 inhibitors) and the FIDELIO-DKD study (Finerenone) demonstrate that when added to standard renin-angiotensin system (RAS) blockade, these agents significantly reduce the risk of renal function decline and ESRD in patients with DKD (60, 61). Importantly, renoprotective effects of these agents are independent from glucose-lowering or blood pressure-lowering actions. Hence, SGLT2 inhibitors and Finerenone likely act directly on anti-inflammatory and antifibrotic pathways. The introduction of these medications marks a paradigm shift in DKD management, moving beyond risk factor control and toward direct targeting of pathophysiological processes.

Another important therapeutics, GLP-1RAs, has also been shown to provide renoprotection independent from glycemic control, partly due to their anti-inflammatory properties. Studies indicate that GLP-1RAs activate the cAMP/PKA signaling pathway and suppress key inflammatory mediators such as NF-κB in both renal and immune cells, thereby decreasing the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines (62). Post hoc analyses of major cardiovascular outcome trials (e.g., LEADER, REWIND) further revealed that GLP-1RAs significantly lower the risk of composite renal events in diabetic patients (63, 64). Thus, GLP-1RAs, together with SGLT2 inhibitors and Finerenone, form the cornerstone of a contemporary therapeutic framework aimed at mitigating DKD progression via anti-inflammatory mechanisms.

Beyond established agents described above, drug development is progressing along two major avenues. The first one involves targeted therapies informed by precision medicine, including specific NLRP3 inflammasome inhibitors (e.g., MCC950) and IL-1β antagonists (e.g., Canakinumab) (65–67). These agents are designed to precisely disrupt specific pathogenic inflammatory cascades, potentially offering enhanced efficacy and a more favorable safety profile. A key challenge in this area, however, is the achievement of kidney-selective drug delivery which enables effective local suppression of renal inflammation while minimizing systemic immune disruption. Overcoming this targeting barrier is essential for the successful clinical translation of similar therapies.

Simultaneously, natural products hold considerable promise in DKD drug development due to their multi-targeting, anti-inflammatory, and antioxidant properties (68–70). Extensive research has demonstrated that various natural bioactive compounds (e.g., flavonoids, alkaloids) exert synergistic protective effects by modulating multiple pathogenic pathways. Specifically for anti-inflammation, certain natural products directly inhibit NLRP3 inflammasome activation or antagonize the NF-κB signaling pathway, reducing the release of pro-inflammatory factors (71, 72). With respect to antifibrotic and cellular homeostasis regulation, natural products mitigate DKD progression through multidimensional mechanisms, including interference with the TGF-β/Smad pathway, activation of the Nrf2/ARE pathway, and restoration of podocyte autophagy (73–76). Critically, the integration of multi-omics technologies provides powerful tools for systematically deciphering complex actions of natural products, advancing relevant research from a “whole-system” model toward "precision targeting” and establishing a scientific foundation for the development of standardized therapies (77).

Of particular significance, the broad cardiorenal benefits observed with these treatments reinforce the concept of DKD as a manifestation of diabetes-associated panvascular disease. By intervening shared pathological pathways—such as inflammation and fibrosis—across the cardiovascular and renal systems, novel therapies enable synergistic management of multiple diabetic complications. This integrated approach represents a critical future direction not only for DKD treatment but also for comprehensive complication management in diabetes. Key anti-inflammatory and anti-fibrotic mechanisms of the therapeutics discussed above are summarized in Table 2.

Table 2

| Drug class | Experimental model | Key anti-inflammatory/anti-fibrotic mechanism | Dosage/concentration | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SGLT2 Inhibitors (e.g., Canagliflozin) | Patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) and CKD (CREDENCE trial) | Attenuates glomerular hypertension and improves mitochondrial function, thereby suppressing inflammation at the metabolic source; | 100 mg, once daily | (58, 60) |

| ns-MRAs (e.g., Finerenone) | Patients with T2DM and CKD (FIDELIO-DKD trial) | Antagonizes the MR to inhibit pro-inflammatory and pro-fibrotic signaling, reducing endothelial apoptosis, inhibiting smooth muscle cell proliferation, attenuating leukocyte recruitment, and promoting vascular repair; | 10 or 20 mg, once daily | (59, 61) |

| GLP-1 Receptor Agonists (e.g., Liraglutide, Dulaglutide) | Patients with T2DM (Cardiovascular outcome trials) | Activates the cAMP/PKA pathway, inhibiting key inflammatory signaling (e.g., NF-κB) and reducing pro-inflammatory cytokine production; | Liraglutide: 1.8 mg/day Dulaglutide: 1.5 mg/week | (62–64) |

| Targeted Therapies (Preclinical or Halted) (e.g., MCC950, Canakinumab) | Preclinical rodent models of DKD | Specifically inhibits NLRP3 inflammasome assembly and neutralizes IL-1β activity, thereby precisely blocking specific inflammatory pathways; | Preclinical concentrations | (65–67) |

| Natural Products (e.g., Flavonoids, Alkaloids) | Preclinical rodent models of DKD | Multi-targeted actions: modulates key signaling pathways including TGF-β/Smad, NF-κB, and NLRP3 to exert synergistic anti-inflammatory and anti-fibrotic effects; | Varies by specific compound | (68–76) |

Key anti-inflammatory and anti-fibrotic mechanisms of pharmacologic interventions in diabetic kidney disease.

5 Discussion

Despite substantial advances on multiple fronts—from understanding inflammatory mechanisms to developing diagnostics and anti-inflammatory therapies—numerous challenges and opportunities remain for DKD research. Firstly, inflammatory pathways in DKD is a highly complex and interconnected network. Future studies should extend beyond the description of isolated pathways to elucidate specific crosstalks and hierarchical relationships between key signaling axes—such as those involving the NLRP3 inflammasome and NF-κB. It is particularly important to determine whether these interactions vary among different renal intrinsic cells and infiltrating immune cells, with clarifying respective underlying mechanisms. For example, identifying cell types in which NF-κB serves as an essential “priming” signal for NLRP3 activation, and how following released IL-1β feeds back to modulate NF-κB in different cellular contexts, would help delineate the inflammatory amplification loops in DKD. Clarifying such cell-type-specific interaction network is fundamental to understand the central inflammatory processes in DKD, and developing precise therapies.

Secondly, constructing a molecular inflammatory subtyping system for DKD based on existing inflammatory biomarkers and integrating it with multi-omics technologies and AI, will be immensely helpful for advancing precision medicine. Future therapeutic approaches may thus evolve beyond the “one-size-fits-all“ model toward tailored regimens—selecting optimal combinations of drugs (SGLT2 inhibitors, Finerenone, or other investigational anti-inflammatory agents) according to specific inflammatory subtype.

Moreover, exploring novel therapies that target innate and adaptive immune responses—such as cytokine-directed biologics and regulatory T cell based strategies—holds considerable promise. Natural product derived bioactive compounds also offer unique potential for modulating complex inflammatory networks due to their multi-target properties. Future research should actively investigate the response to treatment containing both natural products and conventional standard therapies. Synergistic mechanisms by which the combined therapy mitigates DKD should also be systematically elucidated using multi-omics approaches.

Critically, future investigations must transcend a kidney-centric view and adopt a broader systemic perspective. DKD represents the renal manifestation of diabetic panvascular disease. Its pathogenesis and progression are profoundly influenced by systemic inflammation and inter-organ crosstalk. Therefore, further exploration of the molecular mechanisms governing “organ–organ dialogue”—such as the gut-kidney, oral-kidney, and heart-kidney axes—will be essential to unraveling the systemic nature of DKD. For instance, elucidating how gut microbiota-derived metabolites or orally sourced inflammatory mediators remotely regulate the renal immune microenvironment may reveal novel therapeutic targets. Findings from this research would also provide a rationale for precision modulation of the gut-kidney axis via dietary interventions, probiotics, or natural product-derived drugs.

To this end, integrated therapeutic strategies capable of simultaneously targeting multiple organs and pathways should be developed. These strategies should not only act directly on the kidneys but also aim to reduce systemic inflammatory burden and preserve vascular integrity. Successful development of such treatment enables fundamental prevention and control of diabetic panvascular complications. Finally, translating these preclinical insights into clinical practice will require validation through large-scale prospective studies and real-world evidence to evaluate the long-term benefits and safety. Optimal timing to apply different anti-inflammatory strategies across disease stages should also be determined.

In summary, this review highlights the importance of understanding DKD within a systemic inflammation and panvascular disease framework by examining its inflammatory mechanisms, emerging diagnostic approches, and new advance in treatments. Looking forward, a core strategy centered on anti-inflammation, combining with precise molecular subtyping, multi-target integrated interventions, and a deepened understanding of inter-organ mechanisms represents a critical pathway to ultimately overcome DKD.

Statements

Author contributions

SL: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Writing – original draft. ZS: Validation, Writing – original draft. MZ: Writing – review & editing. ZJ: Writing – review & editing. TW: Supervision, Writing – review & editing. XZ: Funding acquisition, Supervision, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declared that financial support was received for this work and/or its publication. The authors gratefully acknowledge financial support from the Beijing Natural Science Foundation (No. 7254372, Mi Zhou), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Nos. 82270888 and 81800732, Xiaojun Zhou), the Taishan Scholar Project of Shandong Province (No. tsqn202408367, Xiaojun Zhou), and the China Postdoctoral Science Foundation (No. 2021M691957, Xiaojun Zhou). This work is also supported by the China Scholarship Council (CSC).

Conflict of interest

The author(s) declared that this work was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declared that generative AI was not used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1.

Liu DW Li ZY Liu ZS . Treatment of diabetic kidney disease: research development, current hotspots and future directions. Zhonghua Yi Xue Za Zhi. (2021) 101:683–6. doi: 10.3760/cma.j.cn112137-20210106-00028

2.

Zhang R Wang Q Li Y Li Q Zhou X Chen X et al . A new perspective on proteinuria and drug therapy for diabetic kidney disease. Front Pharmacol. (2024) 15:1349022. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2024.1349022

3.

Ma RX Wang XJ Peng DQ . Advances in the diagnosis and poor prognosis of diabetic hyperfiltration. Zhonghua Yu Fang Yi Xue Za Zhi. (2024) 58:1256–62. doi: 10.3760/cma.j.cn112150-20240108-00027

4.

An N Wu BT Yang YW Huang ZH Feng JF . Re-understanding and focusing on normoalbuminuric diabetic kidney disease. Front Endocrinol. (2022) 13:1077929. doi: 10.3389/fendo.2022.1077929

5.

Petrica L . Special issue IJMS-molecular mechanisms of diabetic kidney disease. Int J Mol Sci. (2024) 25:790. doi: 10.3390/ijms25020790

6.

Petrica L . Special issue-molecular mechanisms of diabetic kidney disease 2.0. Int J Mol Sci. (2025) 26:7315. doi: 10.3390/ijms26157315

7.

Satirapoj B Adler SG . Comprehensive approach to diabetic nephropathy. Kidney Res Clin Pract. (2014) 33:121–31. doi: 10.1016/j.krcp.2014.08.001

8.

Sparling DP Tryggestad JB . Youth-onset type 2 diabetes: advances, treatments, and challenges in prevention. J Clin Lipidol. (2025) 19:29–36. doi: 10.1016/j.jacl.2025.05.020

9.

Zhang X Zhang J Ren Y Sun R Zhai X . Unveiling the pathogenesis and therapeutic approaches for diabetic nephropathy: insights from panvascular diseases. Front Endocrinol. (2024) 15:1368481. doi: 10.3389/fendo.2024.1368481

10.

Fang J Wu Y Wang H Zhang J You L . Oral health and diabetic cardiomyopathy: mechanisms, biomarkers, and early screening approaches. J Inflamm Res. (2025) 18:8689–704. doi: 10.2147/JIR.S521430

11.

Tang SCW Yiu WH . Innate immunity in diabetic kidney disease. Nat Rev Nephrol. (2020) 16:206–22. doi: 10.1038/s41581-019-0234-4

12.

Donate-Correa J González-Luis A Díaz-Vera J Hernandez-Fernaud JR . MicroRNA-630: a promising avenue for alleviating inflammation in diabetic kidney disease. World J Diabetes. (2024) 15:1398–403. doi: 10.4239/wjd.v15.i7.1398

13.

Al Madhoun A . MicroRNA-630: a potential guardian against inflammation in diabetic kidney disease. World J Diab. (2024) 15:1837–1841. doi: 10.4239/wjd.v15.i9.1837

14.

Liu Y Wang W Zhang J Gao S Xu T Yin Y . JAK/STAT signaling in diabetic kidney disease. Front Cell Dev Biol. (2023) 11:1233259. doi: 10.3389/fcell.2023.1233259

15.

Ma TT Meng XM . TGF-β/Smad and renal fibrosis. Adv Exp Med Biol. (2019) 1165:347–64. doi: 10.1007/978-981-13-8871-2_16

16.

Qiu YY Tang LQ . Roles of the NLRP3 inflammasome in the pathogenesis of diabetic nephropathy. Pharmacol Res. (2016) 114:251–64. doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2016.11.004

17.

Granda Alacote AC Goyoneche Linares G Castañeda Torrico MG Diaz-Obregón DZ Núñez MBC Murillo Carrasco AG et al . T-cell subpopulations and differentiation bias in diabetic and non-diabetic patients with chronic kidney disease. Biomedicines. (2024) 13:3. doi: 10.3390/biomedicines13010003

18.

Peng L Wen L Shi QF Gao F Huang B Meng J et al . Scutellarin ameliorates pulmonary fibrosis through inhibiting NF-κB/NLRP3-mediated epithelial-mesenchymal transition and inflammation. Cell Death Dis. (2020) 11:978. doi: 10.1038/s41419-020-03178-2

19.

Chen X Han R Hao P Wang L Liu M Jin M et al . Nepetin inhibits IL-1β induced inflammation via NF-κB and MAPKs signaling pathways in ARPE-19 cells. Biomed Pharmacother. (2018) 101:87–93. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2018.02.054

20.

Bauernfeind FG Horvath G Stutz A Alnemri ES MacDonald K Speert D et al . Cutting edge: NF-kappaB activating pattern recognition and cytokine receptors license NLRP3 inflammasome activation by regulating NLRP3 expression. J Immunol. (2009) 183:787–91. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0901363

21.

Kajiwara K Sawa Y Fujita T Tamaoki S . Immunohistochemical study for the expression of leukocyte adhesion molecules, and FGF23 and ACE2 in P. gingivalis LPS-induced diabetic nephropathy. BMC Nephrol. (2021) 22:3. doi: 10.1186/s12882-020-02203-y

22.

Sawa Y Takata S Hatakeyama Y Ishikawa H Tsuruga E . Expression of toll-like receptor 2 in glomerular endothelial cells and promotion of diabetic nephropathy by Porphyromonas gingivalis lipopolysaccharide. PLoS ONE. (2014) 9:e97165. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0097165

23.

Wu HQ Wei X Yao JY Qi JY Xie HM Sang AM et al . Association between retinopathy, nephropathy, and periodontitis in type 2 diabetic patients: a Meta-analysis. Int J Ophthalmol. (2021) 14:141–7. doi: 10.18240/ijo.2021.01.20

24.

Wei Y Mou S Yang Q Liu F Cooper ME Chai Z . To target cellular senescence in diabetic kidney disease: the known and the unknown. Clin Sci (Lond). (2024) 138:991–1007. doi: 10.1042/CS20240717

25.

Shen S Ji C Wei K . Cellular senescence and regulated cell death of tubular epithelial cells in diabetic kidney disease. Front Endocrinol. (2022) 13:924299. doi: 10.3389/fendo.2022.924299

26.

Yan Z Xu J Liu T Wang L Zhang Q Li X et al . The role of renal cell senescence in diabetic kidney disease: mechanisms and therapeutic advances. Diabetes Metab Syndr Obes. (2025) 18:3323–41. doi: 10.2147/DMSO.S543814

27.

Hartleben B Wanner N Huber TB . Autophagy in glomerular health and disease. Semin Nephrol. (2014) 34:42–52. doi: 10.1016/j.semnephrol.2013.11.007

28.

Yang H Sun J Sun A Wei Y Xie W Xie P et al . Podocyte programmed cell death in diabetic kidney disease: molecular mechanisms and therapeutic prospects. Biomed Pharmacother. (2024) 177:117140. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2024.117140

29.

Zhong S Wang N Zhang C . Podocyte death in diabetic kidney disease: potential molecular mechanisms and therapeutic targets. Int J Mol Sci. (2024) 25:9035. doi: 10.3390/ijms25169035

30.

Stanigut AM Tuta L Pana C Alexandrescu L Suceveanu A Blebea NM et al . Autophagy and mitophagy in diabetic kidney disease-a literature review. Int J Mol Sci. (2025) 26:806. doi: 10.3390/ijms26020806

31.

Audzeyenka I Bierżyńska A Lay AC . Podocyte bioenergetics in the development of diabetic nephropathy: the role of mitochondria. Endocrinology. (2022) 163:bqab234. doi: 10.1210/endocr/bqab234

32.

Jiang XS Chen XM Hua W He JL Liu T Li XJ et al . PINK1/Parkin mediated mitophagy ameliorates palmitic acid-induced apoptosis through reducing mitochondrial ROS production in podocytes. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. (2020) 525:954–61. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2020.02.170

33.

Hu ZB Lu J Chen PP Lu CC Zhang JX Li XQ et al . Dysbiosis of intestinal microbiota mediates tubulointerstitial injury in diabetic nephropathy via the disruption of cholesterol homeostasis. Theranostics. (2020) 10:2803–16. doi: 10.7150/thno.40571

34.

Liu J Guo M Yuan X Fan X Wang J Jiao X . Gut microbiota and their metabolites: the hidden driver of diabetic nephropathy? Unveiling gut microbe's role in DN. J Diabetes. (2025) 17:e70068. doi: 10.1111/1753-0407.70068

35.

Yu JX Chen X Zang SG Chen X Wu YY Wu LP et al . Gut microbiota microbial metabolites in diabetic nephropathy patients: far to go. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. (2024) 14:1359432. doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2024.1359432

36.

Zhao H Zhao T Li P . Gut microbiota-derived metabolites: a new perspective of traditional Chinese medicine against diabetic kidney disease. J Integr Med Nephrol Androl. (2024) 11:e23–00024. doi: 10.1097/IMNA-D-23-00024

37.

Miao H Wang KE Li P Zhao YY . Rhubarb: traditional uses, phytochemistry, multiomics-based novel pharmacological and toxicological mechanisms. Drug Des Devel Ther. (2025) 19:9457–80. doi: 10.2147/DDDT.S557114

38.

Zang J Maxwell AP Simpson DA McKay GJ . Differential expression of urinary exosomal MicroRNAs miR-21-5p and miR-30b-5p in individuals with diabetic kidney disease. Sci Rep. (2019) 9:10900. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-47504-x

39.

Yang Y Chen Y Tang JY Chen J Li GQ Feng B et al . MiR-29a-3p inhibits fibrosis of diabetic kidney disease in diabetic mice via downregulation of DNA methyl transferase 3A and 3B. World J Diabetes. (2025) 16:93630. doi: 10.4239/wjd.v16.i4.93630

40.

Tejera-Muñoz A Marchant V Tejedor-Santamaría L Opazo-Ríos L Lavoz C Gimeno-Longas MJ et al . The role of miR-802 in diabetic kidney disease: diagnostic and therapeutic insights. Int J Mol Sci. (2025) 26:5474. doi: 10.3390/ijms26125474

41.

Sheng J Lu C Liao Z Xue M Zou Z Feng J et al . Suppression of lncRNA Snhg1 inhibits high glucose-induced inflammation and proliferation in mouse mesangial cells. Toxicol In Vitro. (2023) 86:105482. doi: 10.1016/j.tiv.2022.105482

42.

Yuan L Duan J Zhou H . Perspectives of circular RNAs in diabetic complications from biological markers to potential therapeutic targets (Review). Mol Med Rep. (2023) 28:194. doi: 10.3892/mmr.2023.13081

43.

Wang Y Yang J Wu C Guo Y Ding Y Zou X . LncRNA SNHG14 silencing attenuates the progression of diabetic nephropathy via the miR-30e-5p/SOX4 axis. J Diabetes. (2024) 16:e13565. doi: 10.1111/1753-0407.13565

44.

Yang Y Zhang Y Li Y Zhou X Honda K Kang D et al . Complement classical and alternative pathway activation contributes to diabetic kidney disease progression: a glomerular proteomics on kidney biopsies. Sci Rep. (2025) 15:495. doi: 10.1038/s41598-024-84900-4

45.

Fan G Gong T Lin Y Wang J Sun L Wei H et al . Urine proteomics identifies biomarkers for diabetic kidney disease at different stages. Clin Proteomics. (2021) 18:32. doi: 10.1186/s12014-021-09338-6

46.

Peng J Yang S Zhou C Qin C Fang K Tan Y et al . Identification of common biomarkers in diabetic kidney disease and cognitive dysfunction using machine learning algorithms. Sci Rep. (2024) 14:22057. doi: 10.1038/s41598-024-72327-w

47.

Meng Z Guan Z Yu S Wu Y Zhao Y Shen J et al . Non-invasive biopsy diagnosis of diabetic kidney disease via deep learning applied to retinal images: a population-based study. Lancet Digit Health. (2025) 7:100868. doi: 10.1016/j.landig.2025.02.008

48.

Jørgensen SH Emdal KB Pedersen AK Axelsen LN Kildegaard HF Demozay D et al . Multi-layered proteomics identifies insulin-induced upregulation of the EphA2 receptor via the ERK pathway which is dependent on low IGF1R level. Sci Rep. (2024) 14:28856. doi: 10.1038/s41598-024-77817-5

49.

Zhang R Chang R Wang H Chen J Lu C Fan K et al . Untargeted metabolomic and proteomic analysis implicates SIRT2 as a novel therapeutic target for diabetic nephropathy. Sci Rep. (2025) 15:4236. doi: 10.1038/s41598-024-80492-1

50.

Poulsen CG Rasmussen DGK Genovese F Hansen TW Nielsen SH Reinhard H et al . Marker for kidney fibrosis is associated with inflammation and deterioration of kidney function in people with type 2 diabetes and microalbuminuria. PLoS ONE. (2023) 18:e0283296. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0283296

51.

Das S Devi Rajeswari V Venkatraman G Elumalai R Dhanasekaran S Ramanathan G . Current updates on metabolites and its interlinked pathways as biomarkers for diabetic kidney disease: a systematic review. Transl Res. (2024) 265:71–87. doi: 10.1016/j.trsl.2023.11.002

52.

Li H Li L Huang QQ Yang SY Zou JJ Xiao F et al . Global status and trends of metabolomics in diabetes: a literature visualization knowledge graph study. World J Diabetes. (2024) 15:1021–44. doi: 10.4239/wjd.v15.i5.1021

53.

Jung SW Moon JY . The role of inflammation in diabetic kidney disease. Korean J Intern Med. (2021) 36:753–66. doi: 10.3904/kjim.2021.174

54.

Yang Y He X Liu W Mu L Wang S . Comprehensive bioinformatics and in vivo validation reveal key molecular drivers of diabetic nephropathy progression. Front Endocrinol. (2025) 16:1654401. doi: 10.3389/fendo.2025.1654401

55.

Jiang J Zhan L Dai L Yao X Qin Y Zhu Z et al . Evaluation of the reliability of MS1-based approach to profile naturally occurring peptides with clinical relevance in urine samples. Rapid Commun Mass Spectrom. (2025) 39:e9369. doi: 10.1002/rcm.9369

56.

Wang YR Li N Zhao P Lin L . Value of contrast-enhanced ultrasound parameters in evaluating K-W nodule formation in diabetic nephropathy. Zhongguo Yi Xue Ke Xue Yuan Xue Bao. (2021) 43:314–21. doi: 10.3881/j.issn.1000-503X.13821

57.

Dholariya S Dutta S Sonagra A Kaliya M Singh R Parchwani D et al . Unveiling the utility of artificial intelligence for prediction, diagnosis, and progression of diabetic kidney disease: an evidence-based systematic review and meta-analysis. Curr Med Res Opin. (2024) 40:2025–55. doi: 10.1080/03007995.2024.2423737

58.

Winiarska A Knysak M Nabrdalik K Gumprecht J Stompór T . Inflammation and oxidative stress in diabetic kidney disease: the targets for SGLT2 inhibitors and GLP-1 receptor agonists. Int J Mol Sci. (2021) 22:10822. doi: 10.3390/ijms221910822

59.

Lv R Xu L Che L Liu S Wang Y Dong B . Cardiovascular-renal protective effect and molecular mechanism of finerenone in type 2 diabetic mellitus. Front Endocrinol. (2023) 14:1125693. doi: 10.3389/fendo.2023.1125693

60.

Oshima M Neuen BL Li J Perkovic V Charytan DM de Zeeuw D et al . Early change in albuminuria with canagliflozin predicts kidney and cardiovascular outcomes: a PostHoc analysis from the CREDENCE trial. J Am Soc Nephrol. (2020) 31:2925–36. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2020050723

61.

Ruilope LM Pitt B Anker SD Rossing P Kovesdy CP Pecoits-Filho R et al . Kidney outcomes with finerenone: an analysis from the FIGARO-DKD study. Nephrol Dial Transplant. (2023) 38:372–83. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfac157

62.

Lin K Wang A Zhai C Zhao Y Hu H Huang D et al . Semaglutide protects against diabetes-associated cardiac inflammation via Sirt3-dependent RKIP pathway. Br J Pharmacol. (2025) 182:1561–81. doi: 10.1111/bph.17327

63.

Riddle MC Gerstein HC Xavier D Cushman WC Leiter LA Raubenheimer PJ et al . Efficacy and Safety of Dulaglutide in Older Patients: A post hoc Analysis of the REWIND trial. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. (2021) 106:1345–51. doi: 10.1210/clinem/dgab065

64.

Persson F Bain SC Mosenzon O Heerspink HJL Mann JFE Pratley R et al . Changes in albuminuria predict cardiovascular and renal outcomes in type 2 diabetes: a post hoc analysis of the LEADER trial. Diabetes Care. (2021) 44:1020–6. doi: 10.2337/dc20-1622

65.

Li H Guan Y Liang B Ding P Hou X Wei W et al . Therapeutic potential of MCC950, a specific inhibitor of NLRP3 inflammasome. Eur J Pharmacol. (2022) 928:175091. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2022.175091

66.

Wu M Yang Z Zhang C Shi Y Han W Song S et al . Inhibition of NLRP3 inflammasome ameliorates podocyte damage by suppressing lipid accumulation in diabetic nephropathy. Metabolism. (2021) 118:154748. doi: 10.1016/j.metabol.2021.154748

67.

Speer T Dimmeler S Schunk SJ Fliser D Ridker PM . Targeting innate immunity-driven inflammation in CKD and cardiovascular disease. Nat Rev Nephrol. (2022) 18:762–78. doi: 10.1038/s41581-022-00621-9

68.

Chen Y Liu Y Cao A . The potential of huangqi decoction for treating diabetic kidney disease. Integr Med Nephrol Androl. (2024) 11:e00020. doi: 10.1097/IMNA-D-23-00020

69.

Lei Y Huang J Xie Z Wang C Li Y Hua Y et al . Elucidating the pharmacodynamic mechanisms of Yuquan pill in T2DM rats through comprehensive multi-omics analyses. Front Pharmacol. (2023) 14:1282077. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2023.1282077

70.

Liu J Ren J Zhou L Tan K Du D Xu L et al . Proteomic and lipidomic analysis of the mechanism underlying astragaloside IV in mitigating ferroptosis through hypoxia-inducible factor 1α/heme oxygenase 1 pathway in renal tubular epithelial cells in diabetic kidney disease. J Ethnopharmacol. (2024) 334:118517. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2024.118517

71.

Li H Dong A Li N Ma Y Zhang S Deng Y et al . Mechanistic study of schisandra chinensis fruit mixture based on network pharmacology, molecular docking and experimental validation to improve the inflammatory response of DKD through AGEs/RAGE signaling pathway. Drug Des Devel Ther. (2023) 17:613–32. doi: 10.2147/DDDT.S395512

72.

Zhang SJ Zhang YF Bai XH Zhou MQ Zhang ZY Zhang SX et al . Integrated network pharmacology analysis and experimental validation to elucidate the mechanism of acteoside in treating diabetic kidney disease. Drug Des Devel Ther. (2024) 18:1439–57. doi: 10.2147/DDDT.S445254

73.

Jiang CH Zhang SJ Li P Miao H Zhao YY . Natural products targeting TGF-β/Smad signaling in renal fibrosis: Multiomics-based novel molecular mechanisms and therapeutic strategies. Phytomedicine. (2025) 148:157496. doi: 10.1016/j.phymed.2025.157496

74.

Sun MY Ye HJ Zheng C Jin ZJ Yuan Y Weng HB . Astragalin ameliorates renal injury in diabetic mice by modulating mitochondrial quality control via AMPK-dependent PGC1α pathway. Acta Pharmacol Sin. (2023) 44:1676–86. doi: 10.1038/s41401-023-01064-z

75.

Zou TF Liu ZG Cao PC Zheng SH Guo WT Wang TX et al . Fisetin treatment alleviates kidney injury in mice with diabetes-exacerbated atherosclerosis through inhibiting CD36/fibrosis pathway. Acta Pharmacol Sin. (2023) 44:2065–74. doi: 10.1038/s41401-023-01106-6

76.

Liang ST Chen C Chen RX Li R Chen WL Jiang GH et al . Michael acceptor molecules in natural products and their mechanism of action. Front Pharmacol. (2022) 13:1033003. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2022.1033003

77.

Roy D Ghosh M Rangra NK . Herbal approaches to diabetes management: pharmacological mechanisms and omics-driven discoveries. Phytother Res. (2024) 39:5464–90. doi: 10.1002/ptr.8410

Summary

Keywords

diabetic kidney disease, GLP-1 receptor agonists, inflammation, multi-omics, NLRP3 inflammasome, non-steroidal mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists, pathogenesis, SGLT2 inhibitors

Citation

Lin S, Shu Z, Zhou M, Jia Z, Wei T and Zhou X (2026) Inflammatory mechanisms in diabetic nephropathy: emerging insights and targeted therapeutics. Front. Med. 12:1722159. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2025.1722159

Received

10 October 2025

Revised

19 December 2025

Accepted

22 December 2025

Published

16 January 2026

Volume

12 - 2025

Edited by

Federico Biscetti, Agostino Gemelli University Polyclinic (IRCCS), Italy

Reviewed by

Hua Miao, Northwest University, China

Xu Zhai, China Academy of Chinese Medical Sciences, China

Updates

Copyright

© 2026 Lin, Shu, Zhou, Jia, Wei and Zhou.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Xiaojun Zhou, 1989919zm@163.com; Tianshu Wei, tianshu-wei@outlook.com

†These authors have contributed equally to this work and share first authorship

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.