Abstract

Palmoplantar keratoderma (PPK) represents a heterogeneous group of disorders characterized by hyperkeratosis of the palms and soles. Epidermolytic palmoplantar keratoderma (EPPK) is typically caused by variations in KRT9 or KRT1 genes. However, growing evidence suggests that defects in desmosomal genes, particularly desmoplakin (DSP), may underlie atypical variants. We report a 17-year-old girl with a 10-year history of yellowish, hyperkeratotic plaques with greasy scales on the dorsal hands, soles, and axillae. Histopathology revealed hyperkeratosis, parakeratosis, and acantholysis. Whole-exome sequencing (WES) identified a novel heterozygous frameshift variation in DSP (c.6218_6219dup, p. Ala2074Ter), confirmed by Sanger sequencing. This is the first report of an atypical EPPK caused by a DSP frameshift variation in the C-terminal domain, expanding the genotypic and phenotypic spectrum of PPK. The variant was absent from the gnomAD database. Functional studies demonstrated significant downregulation of adhesion molecules (CDH1, JUP, and CTNNA1) upon DSP knockdown, suggesting impaired desmosome-keratin anchoring as the pathogenic mechanism. This case reveals that DSP C-terminal domain variations can cause a new subtype of EPPK, providing new insights into PPK diagnosis and treatment.

1 Introduction

Palmoplantar keratoderma (PPK) encompasses a group of inherited skin disorders marked by hyperkeratosis in the palms and soles, with notable clinical and genetic heterogeneity (1). The structural integrity of the epidermis, particularly in high-stress areas such as palms and soles, is maintained by specialized intercellular junctions (2). Desmosome is classified as a calcium-dependent anchoring junction that tethers cells together through its extracellular contacts and internally links to the intermediate filament (IF) cytoskeleton. Through this linkage between cells, the desmosome provides tissues with the ability to resist mechanical forces (3). Desmoplakin (DSP), a core desmosomal protein, links keratin intermediate filaments to the cell membrane, maintaining epidermal integrity (2). Inherited desmosomal disease can lead to both cutaneous and cardiac disease, including certain forms of PPK (4).

Individual PPK cases can exhibit significant heterogeneity in clinical presentation and associated symptoms. Since various forms of hereditary PPK, like many other monogenic disorders, demonstrate very low prevalence rates, establishing a correct diagnosis remains challenging and often requires molecular genetic analysis (1). Advances in high-throughput sequencing have identified over 50 genes associated with PPK, including those encoding keratins (e.g., KRT1 and KRT9), desmosomal proteins (e.g., DSP, JUP, and DSG1), and epidermal differentiation molecules (e.g., SLURP1 and CSTA) (5). Epidermolytic palmoplantar keratoderma (EPPK) is one phenotype of PPK. The incidence rate of EPPK is approximately 2.2 to 4.4 cases per 100,000 live births (6). Classic EPPK, primarily caused by KRT9 variations, manifests in infancy. The condition presents in adulthood with symmetric, presents with diffuse, yellowish hyperkeratosis on the palms and soles with an erythematous margin. A history of blistering may be present, and knuckle pads have been reported (7). Histologically characterized by vacuolar degeneration of the granular layer and keratin aggregation (6, 7). However, some PPK cases exhibit atypical clinical and histopathological features, implying unrecognized pathogenic mechanisms.

DSP is increasingly recognized in atypical PPK phenotypes. Recent systematic reviews highlight that DSP variations not only cause cutaneous manifestations but also give rise to a spectrum of additional syndromes. This spectrum includes severe syndromes such as Carvajal syndrome (characterized by striate PPK, woolly hair, and arrhythmogenic cardiomyopathy, CS) and skin fragility-woolly hair syndrome. The global epidemiology of DSP-related keratoderma is not fully established due to its rarity, but it is considered very rare, with sporadic cases reported worldwide. Recognized geographical clusters exist, such as in Greece (Naxos disease) and Ecuador (CS), yet cases have been identified across diverse populations, underscoring its universal occurrence. Critically, DSP pathogenic variations frequently confer a significant risk of multi-system involvement, particularly arrhythmogenic cardiomyopathy (ACM) (8, 9). The combination of PPK and hair shaft anomalies (e.g., woolly hair, WH) is a recognized warning signal for ACM, with 80.1% of such cases showing cardiac involvement (4). This link mandates a multidisciplinary management approach, including cardiac screening for affected individuals. Here, we describe a novel DSP frameshift variation (c.6218_6219dup) (RefSeq accession number: NM_004415.4, which corresponds to the GRCh37 p.13 or GRCh38 p.14 human reference genome assembly) in a patient with a novel phenotype of EPPK, featuring non-palmoplantar involvement (dorsal hands, axillae) and the presence of acantholysis on histology. DSP gene knockdown disrupted the expression of key adhesion molecules beyond desmosomes, including CDH1 and CTNNA1 (adherens junctions) (10) and JUP (bridging desmosomes and adherens junctions) (11). This reveals the interconnectedness and functional compensation among the diverse intercellular junctions (desmosomes, adherens, tight, gap) in keratinocytes. Desmosomal impairment thus propagates dysfunction through this molecular network, critically contributing to the adhesion defects observed.

2 Case report

A 17-year-old girl presented with a 10-year history of yellowish, scaly, hyperkeratotic plaques on the dorsal hands, soles, and axillae (Figures 1A–C). Ten years ago, the patient first developed erythematous patches on the plantar surface; this was soon followed by mild skin thickening. At that time, the patient did not experience pruritus or other complaints that warranted medical attention. Subsequently, the area of the plantar surface erythema gradually expanded, the thickening worsened, and the skin became yellowish, scaly, rough, and hardened (presenting as hyperkeratotic plaques). Over the past decade, this skin condition (similar erythematous thickening, yellowish discoloration, scaling, and hardening) has progressively extended to involve the axillae and dorsal hands. The affected skin occasionally develops fissures (cracks), particularly when they occur on the plantar surface. Hematological, cardiac, pulmonary, and other examinations showed no significant abnormalities. Cardiac evaluation via electrocardiogram (ECG) revealed no abnormalities (Supplementary Figure 1). No abnormalities were detected in nails, hair, or teeth, and no friction-related lesions either. Other family members were asymptomatic. All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. After the patient signed the informed consent was obtained for a skin biopsy, we performed a skin pathological biopsy on the patient. Skin biopsy showed hyperkeratosis, parakeratosis, vacuolar degeneration of the granular layer, and acantholysis, which conform to a typical pathological manifestation of EPPK (Figures 1D,E).

Figure 1

Clinical and histopathological features: yellow scaly keratotic plaques with oily appearance on the dorsum and soles of both hands; tan keratotic papules in the axilla (A–C). Pathological biopsy: “grain” in stratum corneum and characteristic “round body” in the acantholytic area, separated by normal intervals (D,E).

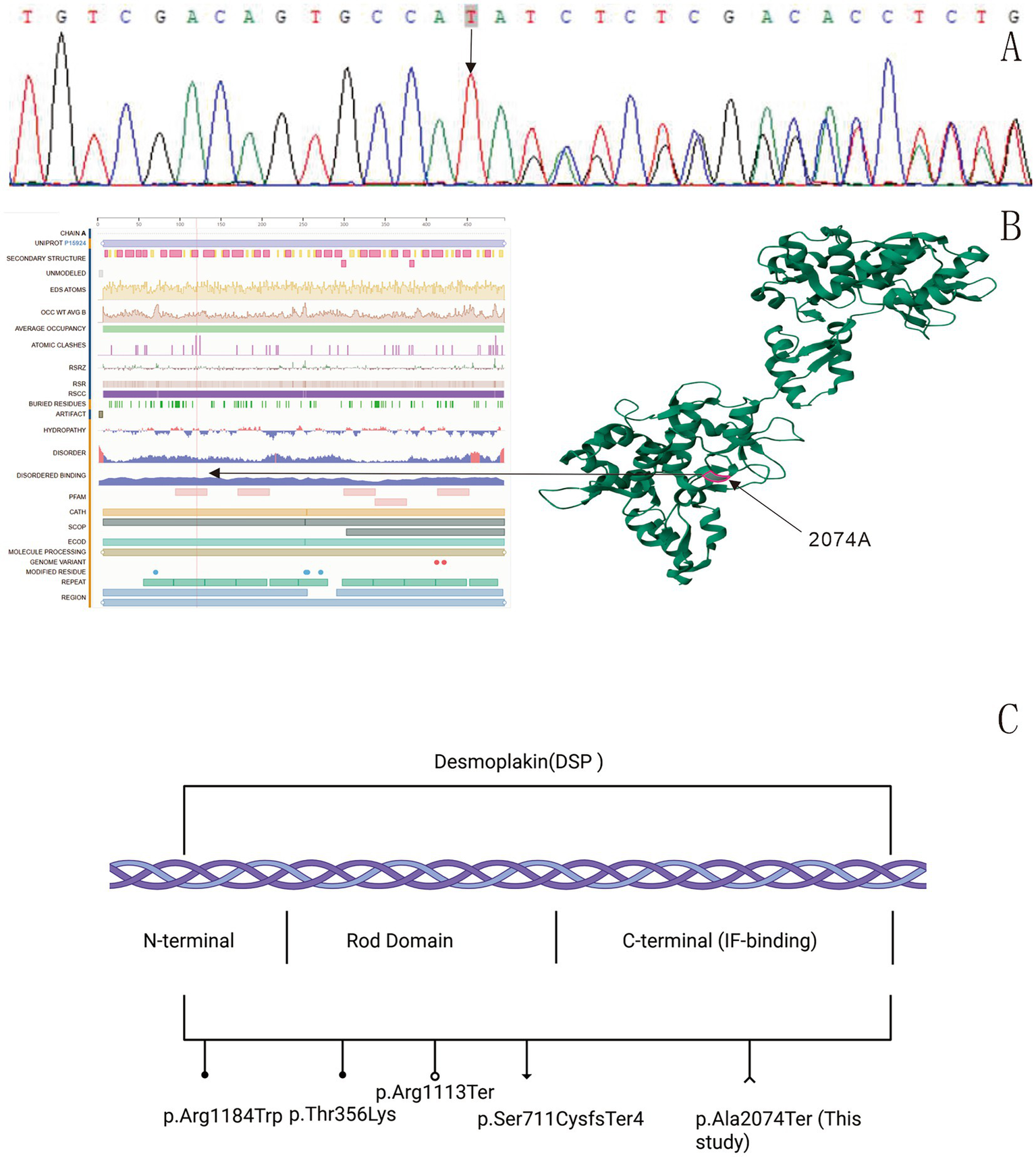

Whole-exome sequencing (WES) identified a heterozygous DSP variation (c.6218_6219dup), which was verified by Sanger sequencing (Figure 2A). This TA duplication causes a frameshift p. Ala2074Ter leading to premature termination (Figures 2B,C), representing a novel variant absent in gnomAD. Parental genetic testing was not performed as the patient’s parents and sister declined to undergo genetic analysis. According to the ACMG-AMP guidelines, the variant was classified as likely pathogenic, meeting the following criteria: PVS1 (null variant in a gene where loss-of-function is a known mechanism of disease), PM2 (absent from population databases), and PS3 (in vitro functional studies supportive of a damaging effect) (12).

Figure 2

Sequencing results: a DSP variation c.6218_6,219 dup (p.Ala2074Ter) was found in the patient (A). Protein structure model: the black arrow indicates the variation sequence (https://www.uniprot.org/uniprotkb/P15924/entry). The red highlighted region is the location of desmoplakin p.Ala2074Ter. A TA duplication between nucleotides 6,218 and 6,219 in the coding region of the DSP gene, resulting in a frameshift variation (p.Ala2074Ter). This variation introduces a premature termination codon at the first downstream stop signal, leading to the complete loss of all subsequent amino acids (B). Schematic representation of reported DSP mutations. ●: Denote missense mutations; ○: denote nonsense mutations; ▼: denote frameshift mutations. ∧: The novel nonsense mutation (p.Ala2074Ter) reported in this study (C).

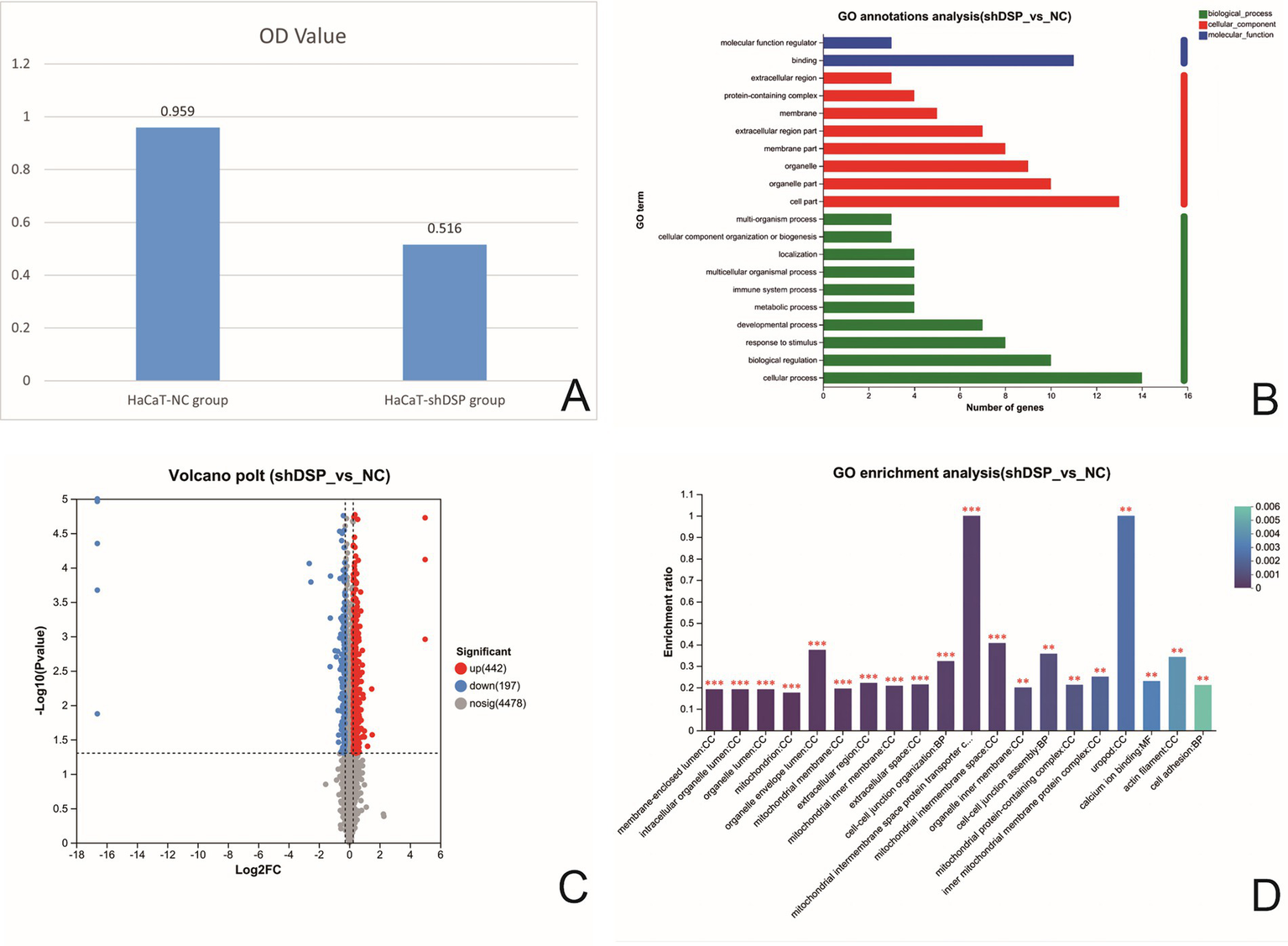

To further investigate the association between DSP gene variations and EPPK, we successfully constructed a stable HaCaT cell line with DSP gene interference (HaCaT-h-DSP-shRNA-ZSGREEN-PURO) (Supplementary Table 1) using the lentiviral infection method. The ethics of this study has been approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the First Affiliated Hospital of Gannan Medical University (LLSC-2025374). In vitro cell experiments showed that compared with the negative control group (HaCaT/NC), the cell adhesion and proliferation abilities of DSP-knockdown HaCaT cells (HaCaT/shDSP) were significantly weakened (p < 0.05) (Figure 3A). Transcriptomic profiling revealed 16 differentially expressed genes (DEGs) (Supplementary Table 2). Gene Ontology (GO) annotation indicated that these DEGs were primarily associated with cellular processes (biological process, BP), organelle components (cellular component, CC), and binding activities (molecular function, MF) (Figure 3B). Six DEGs—cadherin 26 (CDH26), S100 calcium-binding protein P (S100P), GRAM domain containing 2A (GRAMD2A), keratin 6B (KRT6B), keratin 4 (KRT4), and S100 calcium-binding protein A7 (S100A7)—were screened as potentially relevant to the pathology of PPK and are implicated in calcium ion binding, cell adhesion, and epidermal development (Supplementary Table 3).

Figure 3

Comparison of cell adhesion rates of HaCaT cells after DSP interference (A). Histogram of GO classification statistics for differential genes after DSP gene interference. (Note: In the figure, the vertical coordinate represents the second-level classification term of GO, the horizontal coordinate represents the number of genes compared to the second-level classification, and the three colors represent the three classifications) (B). Volcano map of differential proteins in DSP interfered stable strain (the abscissa is the fold change of protein expression in the shDSP group/NC group), and the ordinate is the statistical test value of the difference in protein expression, namely the p-value. The smaller the p-value, the more significant is the expression difference. Each dot in the figure represents a specific protein; the dots on the right are differentially upregulated proteins, and the dots on the left are differentially down-regulated proteins. The more to the left, the more significant the difference in expression is (C). GO enrichment analysis of differentially expressed proteins in DSP-transfected strains (the abscissa represents enriched entries, and the ordinate represents enrichment rates). The column color gradient indicates the significance of enrichment, where a P or FDR value of less than 0.001 is marked as ***, less than 0.01 as **, and less than 0.05 as *) (D).

To further elucidate the underlying molecular pathways, a proteomic analysis was conducted. (The raw proteomics data have been deposited in the iProX database under the accession number PXD070791). Proteomic analysis identified 639 differentially expressed proteins (DEPs) (Figure 3C and Supplementary Table 4). GO enrichment analysis demonstrated significant enrichment of these DEPs in terms related to cell adhesion, calcium ion binding, and the catenin complex (Figure 3D). Three target protein sets were constructed based on these functional categories (Supplementary Figure 2). Cross-analysis among these sets identified 10 key DEPs: EGF like repeats and discoidin domains 3 (EDIL3), thrombospondin 1 (THBS1), desmoglein 2 (DSG2), desmoglein 1 (DSG1), cadherin 2 (CDH2), cadherin 1 (CDH1), cadherin 13 (CDH13), junction plakoglobin (JUP), catenin delta 1 (CTNND1), and catenin alpha 1 (CTNNA1) (Supplementary Table 5). After DSP knockdown, the expression levels of molecules related to cell adhesion, such as E-cadherin (CDH1) (adherens junctions), catenins (CTNND1, CTNNA1) (adherens junctions), JUP (bridging desmosomes and adherens junctions), and calcium-binding protein (S100A7), significantly decreased (p < 0.05).

3 Discussion

PPK represents a group of dermatoses with high clinical and genetic heterogeneity. Different genetic variations can lead to varying clinical manifestations of EPPK (1). Table 1 shows the clinical features, gender, and age of EPPK caused by different variation sites in the DSP gene (Table 1). Our case presented a diagnostic challenge due to its combination of epidermolytic hyperkeratosis, acantholysis, and a non-palmoplantar distribution. This necessitates a careful differentiation from classic forms of PPK and other acantholytic disorders. Classic KRT9-related EPPK is characterized by diffuse, waxy, yellowish hyperkeratosis strictly localized to the pressure points of the palms and soles, and histology shows vacuolar degeneration without prominent acantholysis. The pathogenesis involves impaired keratin dimer assembly and reduced mechanical stability (6, 7). In contrast, our proband demonstrated extensive lesions involving the dorsal hands and axillae, a finding not seen in classic EPPK. While DSP dysfunction theoretically affects all keratinocytes, phenotypic expression can be modulated by regional factors. The extensive involvement in our case may be attributed to the particular susceptibility of flexural and dorsal skin, which experiences constant mechanical stress from stretching and friction. The underlying cause of this susceptibility is likely due to disrupted desmosome-keratin anchoring from the DSP C-terminal truncation (4). Furthermore, our case is distinct from focal or striate PPK. While those forms present with localized or linear keratoderma. More importantly, the hallmark histologic features of epidermolysis and acantholysis observed in our case are not characteristic of typical focal or striate PPK (13). Alternatively, we acknowledge that the precise reason for this specific distribution cannot be fully explained by our current data and may involve yet unidentified modifying factors.

Table 1

| Variation site | Variation protein | Age (years) | Gender | Variation | Reported number of cases | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3550C > T | Arg1184Trp | 61 | Male | Focal PPK and WH | 1 | Xue K, 2019 (20) |

| 1067C > A | Thr356Lys | 14 | Male | WH, dilated cardiomyopathy (DCM) with severe left ventricular insufficiency | 3 | Pigors M, 2015 (21) |

| 7566_7567delinsC | Arg2522SerfsTer39 | 5 | Male | Striate and focal keratoderma, keratotic papules | ||

| 2131_2132del | Ser711CysfsTer4 | 10 | Female | Mild focal plantar keratoses and hypotrichosis | ||

| 2493del | Glu831AspfsTer33 | 23–66 | Seven females and two males | Focal PPK and ACM | 9 | Karvonen V, 2022 (22) |

| 3337C > T | Arg1113Ter | 40 | Four females and five Males | Skin fragility, WH, PPK, ACM and, DCM | 1 | Andrei D, 2024 (23) |

| 6310del | Thr2104GlnfsTer12 | 30–69 | Males | Curly hair, PPK, and ACM with increased trabeculation | 9 | Krista Heliö, 2023 (24) |

| 6687del | Arg2229SerfsTer32 | 21–80 | Five females and one male | Mild PPK and non-lethal cardiomyopathy | 6 | Vermeer MCSC, 2022 (25) |

| 6687delA/273 + 5G > A | Predicted to modify the exon 2 splice site | 23–52 | Two females | Cardiomyopathy, PPK and WH | 2 | |

| 4198C > T | Arg1400Ter | 3 | Male | Cardiomyopathy congenital alopecia, nail dystrophy, PPK, and follicular hyperkeratosis with plugging on the extensor surfaces | 1 | Antonov NK, 2015 (26) |

| 6850C > T | Arg2284Ter |

Additional symptoms of EPPK with DSP gene variations.

Our patient lacked cardiac symptoms or hair shaft anomalies; prior studies emphasize that DSP variations—especially truncating variants—are strongly associated with arrhythmogenic cardiomyopathy. For example, Carvajal syndrome (N-terminal mutations) shows PPK, cardiomyopathy, and WH (absent in our case), while skin fragility-WH syndrome (rod domain mutations) causes blistering and hair anomalies (versus predominant hyperkeratosis here). Notably, cardiac involvement may emerge later in life; thus, lifelong cardiac monitoring (e.g., echocardiography, ECG) is recommended for all DSP variation carriers, regardless of current cardiac status.

Unlike Darier disease (DD), which results from ATP2A2 variations encoding SERCA2, it shares the histologic finding of acantholysis. The DD phenotype typically manifests during adolescence or early adulthood with greasy, hyperkeratotic papules in seborrheic areas (central chest, back, scalp margins, and flexures). The disease is characterized by distinctive nail abnormalities and, in severe forms, extensive malodorous plaques that impair mobility. Neurological and psychiatric abnormalities have been reported in DD. Histopathologically, DD is defined by suprabasal acantholysis leading to lacunae, along with the presence of “corps ronds” and “grains” (14). Our case had DSP (not ATP2A2) variations, palmoplantar involvement (unusual in DD), and cell adhesion (not calcium signaling) defects (15). This structured comparison highlights the novelty of our case, which fits neither the classic EPPK nor the DD profile, instead occupying a unique position in the PPK spectrum.

DD-like phenotypes (as in our case) suggest that C-terminal DSP variations may induce unique acantholytic hyperkeratosis. The wild-type DSP protein consists of 2,871 amino acids (UniProt P15924). Sanger sequencing of the patient revealed a TA duplication between nucleotides 6,218 and 6,219 in the coding region of the DSP gene, resulting in a frameshift variation (p. Ala2074Ter). This variation introduces a premature termination codon at the first downstream stop signal, leading to the complete loss of all subsequent amino acids. Consequently, the entire C-terminal intermediate filament (IF)-binding domain is truncated. The truncated DSP loses its ability to anchor desmosomes to keratin intermediate filaments, causing intercellular adhesion defects in keratinocytes. This disrupts mechanical stress transmission between cells, resulting in epidermal fragility with blister formation and acantholysis (5). We propose a pathogenic pathway: The truncated DSP impairs keratin filament anchoring, leading to mechanical stress imbalance, which causes acantholysis and downregulation of adhesion molecules (e.g., E-cadherin), resulting in aberrant differentiation (16); this subsequently downregulates S100A7, mediating proliferation and differentiation defects (17).

We identified a novel heterozygous DSP frameshift variation (c.6218_6219dup, p. Ala2074Ter) in a novel subtype of atypical EPPK. A limitation of this study is the inability to perform parental genetic testing to definitively determine the mode of inheritance (de novo vs. inherited), as family members declined testing. Nonetheless, the variant was classified as likely pathogenic according to ACMG criteria. The variation is predicted to result in a truncated protein lacking the C-terminal intermediate filament-binding domain, which is critical for anchoring keratin to the desmosomal plaque. Our functional studies support the pathogenicity of this variant. DSP knockdown in keratinocytes significantly impaired cell adhesion and proliferation. Multi-omics analyses revealed that DSP deficiency led to widespread downregulation of key adhesion molecules. While these proteomic findings provide crucial mechanistic insight by confirming the disruption of keratinocyte adhesion pathways and validating the variant’s pathogenicity, they do not directly alter the immediate clinical management strategy for this patient beyond reinforcing the need for cardiac surveillance, which is already standard of care for DSP-related disease.

This study is significant as the first report of atypical EPPK from a DSP C-terminal domain frameshift variation, expanding both the DSP variation spectrum and phenotypic range. Mechanistic insights suggest potential therapies such as topical retinoids (18) or JAK inhibitors (19). After unremarkable preoperative clearance, the patient had the hand lesions removed by excision of bilateral superficial hand masses with concurrent random-pattern flap reconstruction, and was discharged safely. The unresolved implications for cardiac desmosomes warrant long-term follow-up.

4 Conclusion

We describe a novel atypical EPPK caused by DSP c.6218_6219dup (p. Ala2074Ter), with atypical clinicopathological features. Functional studies demonstrate that DSP deficiency disrupts epidermal homeostasis through widespread adhesion molecule dysregulation, offering new perspectives for PPK diagnosis and treatment.

Statements

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by Ethics Committee of The First Affiliated Hospital of Gannan Medical University. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. Written informed consent for participation in this study was provided by the participants’ legal guardians/next of kin. Written informed consent was obtained from the minor(s)’ legal guardian/next of kin for the publication of any potentially identifiable images or data included in this article.

Author contributions

CL: Conceptualization, Data curation, Investigation, Methodology, Software, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. HC: Conceptualization, Data curation, Investigation, Methodology, Software, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. SL: Conceptualization, Investigation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. SH: Data curation, Software, Writing – review & editing. ZG: Data curation, Software, Writing – original draft. LX: Data curation, Project administration, Writing – review & editing. WZ: Data curation, Formal analysis, Project administration, Supervision, Writing – review & editing. JL: Data curation, Formal analysis, Methodology, Project administration, Writing – review & editing. ZZ: Data curation, Project administration, Resources, Supervision, Visualization, Writing – review & editing. CW: Data curation, Project administration, Resources, Supervision, Visualization, Writing – review & editing. LL: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Methodology, Resources, Supervision, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declared that financial support was not received for this work and/or its publication.

Acknowledgments

We thank all the families and physicians who participated in this study.

Conflict of interest

The author(s) declared that this work was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declared that Generative AI was not used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fmed.2025.1728762/full#supplementary-material

References

1.

Schiller S Seebode C Hennies HC Giehl K Emmert S . Palmoplantar keratoderma (PPK): acquired and genetic causes of a not so rare disease. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. (2014) 12:781–8. doi: 10.1111/ddg.12418,

2.

Green KJ Jaiganesh A Broussard JA . Desmosomes: essential contributors to an integrated intercellular junction network. F1000Res. (2019) 8:2150. doi: 10.12688/f1000research.20942.1,

3.

Najor NA . Desmosomes in human disease. Annu Rev Pathol. (2018) 13:51–70. doi: 10.1146/annurev-pathol-020117-044030,

4.

Polivka L Bodemer C Hadj-Rabia S . Combination of palmoplantar keratoderma and hair shaft anomalies, the warning signal of severe arrhythmogenic cardiomyopathy: a systematic review on genetic desmosomal diseases. J Med Genet. (2016) 53:289–95. doi: 10.1136/jmedgenet-2015-103403,

5.

Samuelov L Sprecher E . Inherited desmosomal disorders. Cell Tissue Res. (2015) 360:457–75. doi: 10.1007/s00441-014-2062-y,

6.

Li Y Tang L Han Y Zheng L Zhen Q Yang S et al . Genetic analysis of KRT9 gene revealed previously known mutations and genotype-phenotype correlations in Epidermolytic palmoplantar keratoderma. Front Genet. (2019) 9:645. doi: 10.3389/fgene.2018.00645,

7.

Liu X Qiu C He R Zhang Y Zhao Y . Keratin 9 L164P mutation in a Chinese pedigree with epidermolytic palmoplantar keratoderma, cytokeratin analysis, and literature review. Mol Genet Genomic Med. (2019) 7:e977. doi: 10.1002/mgg3.977,

8.

Yuan ZY Cheng LT Wang ZF Wu YQ . Desmoplakin and clinical manifestations of desmoplakin cardiomyopathy. Chin Med J. (2021) 134:1771–9. doi: 10.1097/CM9.0000000000001581,

9.

Protonotarios N Tsatsopoulou A . Naxos disease: cardiocutaneous syndrome due to cell adhesion defect. Orphanet J Rare Dis. (2006) 1:4. doi: 10.1186/1750-1172-1-4,

10.

Campbell HK Maiers JL DeMali KA . Interplay between tight junctions & adherens junctions. Exp Cell Res. (2017) 358:39–44. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2017.03.061,

11.

Whittock NV Eady RA McGrath JA . Genomic organization and amplification of the human plakoglobin gene (JUP). Exp Dermatol. (2000) 9:323–6. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0625.2000.009005323.x,

12.

Richards S Aziz N Bale S Bick D Das S Gastier-Foster J et al . Standards and guidelines for the interpretation of sequence variants: a joint consensus recommendation of the american college of medical genetics and genomics and the association for molecular pathology. Genet Med. (2015) 17:405–24. doi: 10.1038/gim.2015.30,

13.

Braun-Falco M . Hereditary palmoplantar keratodermas. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. (2009) 7:971–84. doi: 10.1111/j.1610-0387.2009.07058.x,

14.

Zheng L Jiang H Mei Q Chen B . Identification of two novel Darier disease-associated mutations in the ATP2A2 gene. Mol Med Rep. (2015) 12:1845–9. doi: 10.3892/mmr.2015.3605,

15.

Cabral RM Tattersall D Patel V McPhail GD Hatzimasoura E Abrams DJ et al . The DSPII splice variant is critical for desmosome-mediated HaCaT keratinocyte adhesion. J Cell Sci. (2012) 125:jcs.084152. doi: 10.1242/jcs.084152

16.

Wong SHM Fang CM Chuah LH Leong CO Ngai SC . E-cadherin: its dysregulation in carcinogenesis and clinical implications. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. (2018) 121:11–22. doi: 10.1016/j.critrevonc.2017.11.010,

17.

Eckert RL Broome AM Ruse M Robinson N Ryan D Lee K . S100 proteins in the epidermis. J Invest Dermatol. (2004) 123:23–33. doi: 10.1111/j.0022-202X.2004.22719.x,

18.

Marukian NV Levinsohn JL Craiglow BG Milstone LM Choate KA . Palmoplantar Keratoderma in Costello Syndrome Responsive to Acitretin. Pediatr Dermatol. (2017) 34:160–2. doi: 10.1111/pde.13057,

19.

Sanchez GAM Reinhardt A Ramsey S Wittkowski H Hashkes PJ Berkun Y et al . JAK1/2 inhibition with baricitinib in the treatment of autoinflammatory interferonopathies. J Clin Invest. (2018) 128:3041–52. doi: 10.1172/JCI98814,

20.

Xue K Zheng Y Cui Y . A novel heterozygous missense mutation of DSP in a Chinese Han pedigree with palmoplantar keratoderma. J Cosmet Dermatol. (2019) 18:371–6. doi: 10.1111/jocd.12533,

21.

Pigors M Schwieger-Briel A Cosgarea R Diaconeasa A Bruckner-Tuderman L Fleck T et al . Desmoplakin mutations with palmoplantar keratoderma, woolly hair and cardiomyopathy. Acta Derm Venerol. (2015) 95:337–40. doi: 10.2340/00015555-1974,

22.

Karvonen V Harjama L Heliö K Kettunen K Elomaa O Koskenvuo JW et al . A novel desmoplakin mutation causes dilated cardiomyopathy with palmoplantar keratoderma as an early clinical sign. Acad Dermatol Venereol. (2022) 36:1349–58. doi: 10.1111/jdv.18164,

23.

Andrei D Bremer J Kramer D Nijenhuis AM Van Der Molen M Diercks GFH et al . Epidermal growth factor receptor inhibition leads to cellular phenotype correction of DSP -mutated keratinocytes. Exp Dermatol. (2024) 33:e15046. doi: 10.1111/exd.15046,

24.

Heliö K Brandt E Vaara S Weckström S Harjama L Kandolin R et al . DSP c.6310delA p.(Thr2104Glnfs*12) associates with arrhythmogenic cardiomyopathy, increased trabeculation, curly hair, and palmoplantar keratoderma. Front Cardiovasc Med. (2023) 10:1130903. doi: 10.3389/fcvm.2023.1130903,

25.

Vermeer MCSC Andrei D Kramer D Nijenhuis AM Hoedemaekers YM Westers H et al . Functional investigation of two simultaneous or separately segregating DSP variants within a single family supports the theory of a dose-dependent disease severity. Exp Dermatol. (2022) 31:970–9. doi: 10.1111/exd.14571,

26.

Antonov NK Kingsbery MY Rohena LO Lee TM Christiano A Garzon MC et al . Early-onset heart failure, alopecia, and cutaneous abnormalities associated with a novel compound heterozygous mutation in Desmoplakin. Pediatr Dermatol. (2015) 32:102–8. doi: 10.1111/pde.12484,

Summary

Keywords

celladhesion, desmoplakin, epidermolyticpalmoplantar keratoderma, frameshiftvariation, phenotype

Citation

Lin C, Chen H, Lai S, Huang S, Guo Z, Xie L, Zheng W, Lu J, Zeng Z, Wan C and Li L (2026) A frameshift variation in the DSP gene causes a novel subtype of atypical epidermolytic palmoplantar keratoderma: Case report. Front. Med. 12:1728762. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2025.1728762

Received

20 October 2025

Revised

29 November 2025

Accepted

15 December 2025

Published

12 January 2026

Volume

12 - 2025

Edited by

Hans Christian Hennies, Staffordshire University, United Kingdom

Reviewed by

Leila Youssefian, City of Hope National Medical Center, United States

Kellicia Courtney Govender, University of KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa

Updates

Copyright

© 2026 Lin, Chen, Lai, Huang, Guo, Xie, Zheng, Lu, Zeng, Wan and Li.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Longnian Li, li_longnian@foxmail.com

†These authors have contributed equally to this work and share first authorship

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.