Abstract

Aim:

Primary dysmenorrhea is highly prevalent and often suboptimally managed, as non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) fail to provide analgesia in 18% of women. This review therefore aims to evaluate the efficacy and safety of heat therapy—a widely used self-care method—for both preventing and acutely treating primary dysmenorrhea.

Methods:

We searched seven databases (CENTRAL, PubMed, Web of Science, EMBASE, CNKI, VIP, Wanfang) from inception to October 28, 2024 and updated to August 03, 2025. Pairs of reviewers independently screened records, extracted data, and assessed risk of bias using a modified Cochrane RoB 1.0 tool. Random-effects meta-analyses were performed for pain intensity (converted to 10-cm VAS) and adverse events. Evidence certainty was graded via GRADE (Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development, and Evaluations).

Results:

We screened 2,733 citations and included 57 RCTs (involving 5,359 female participants). When compared with no treatment, heat therapy may reduce pain intensity to a greater extent after 3 months (25 RCTs, 2,393 females, WMD −1.85 cm, 95% CI −2.29 to −1.41 cm, RD 21%); it may lead to a greater reduction within 24 h of treatment (3 RCTs, 248 females; WMD −3.52 cm, 95% CI −5.01 to −2.02 cm, RD 45%). When compared to NSAIDs, heat therapy may provide comparable or slightly superior pain relief after 3 months of treatment (22 RCTs, 1,938 females, WMD −1.10 cm, 95% CI −1.51 to −0.70 cm, RD 4%), or within 24 h of treatment (2 RCTs, 167 females, WMD −1.50 cm, 95% CI −2.86 to −0.15 cm, RD 16%). For the safety assessment, heat therapy probably reduced the risk of adverse effects compared with NSAIDs (8 RCTs, 728 females, RR 0.30, 95% CI 0.15–0.59).

Conclusions:

Compared to no treatment, heat therapy is likely to reduce pain intensity both during prophylaxis and acute episodes. When compared to NSAIDs, heat therapy may achieve comparable analgesic efficacy while exhibiting a superior safety profile.

Systematic review registration:

https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/PROSPERO/view/CRD420251050944, identifier CRD420251050944.

1 Introduction

Primary dysmenorrhea is a pervasive yet frequently overlooked public health issue, affecting up to 90% of reproductive-aged women worldwide (1). It is defined as painful menstrual cramps in the absence of pelvic pathology (2). The repercussions are substantial, with severe symptoms leading to activity restriction and absenteeism from work or school in up to 15% of affected women, underscoring its considerable socioeconomic burden (3, 4).

Research indicates that women with dysmenorrhea have elevated levels of prostaglandins, a hormone known to cause crampy abdominal pain. NSAIDs are medications that work by blocking the production of prostaglandins (5). NSAIDs are effective for treating dysmenorrhea, as demonstrated by a meta-analysis of 35 randomized controlled trials (5). However, a review of 51 different clinical trials found that 18% of women reported little to no relief from menstrual pain with NSAIDs (6). And NSAIDs carry a range of adverse effects, primarily affecting the gastrointestinal, renal, and cardiovascular systems (7). Given these limitations, non-pharmacological alternatives are increasingly sought.

A diverse range of non-pharmacological interventions exists, including dietary supplements, transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (TENS), acupuncture, and exercise (8–11). Among these options, thermal therapy stands out by enabling self-care for patients, offering a superior safety profile, and demonstrating high accessibility and public acceptance. The rationale for focusing on heat is 2-fold. First, it aligns with the prostaglandin-based pathophysiology of dysmenorrhea; applied heat increases pelvic blood flow, which may help to dissipate and reduce the concentration of prostaglandins, thereby relieving ischemia and muscle cramps (12). Second, it offers a unique combination of immediate, non-invasive analgesia and an exceptional safety profile, presenting a practical and accessible option for women seeking to avoid medication-related side effects (13). Therefore, we posit that thermal therapy represents a promising and strategic non-pharmacological approach worthy of in-depth study.

2 Methods

2.1 Literature search

An academic librarian systematically designed and executed comprehensive, database-specific search strategies for seven major biomedical databases: Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL), PubMed, Web of Science, EMBASE, Chinese National Knowledge Infrastructure (CNKI), VIP Database for Chinese Technical Periodicals, and Wanfang Data. Our systematic search encompassed all available records from each database's inception through October 28, 2024 and updated to August 03, 2025, without imposing language or publication status limitations. We also searched the previous systematic reviews and screened the reference lists and the studies included (Supplementary Table 1).

2.2 Study selection

Pairs of reviewers (HZY, LXX, CZY, ZWY) independently screened titles, abstracts, and subsequently, the full texts of potentially eligible articles using standardized, pre-tested forms. The data extraction form was structured around the PICOS framework, covering participant characteristics (Population), detailed descriptions of the interventions and comparators (Intervention/Comparison), study design (Study), outcome measures (Outcome), along with risk of bias assessments and records of adverse effects (see Supplementary File 1).

Disagreements primarily concerned the applicability of the interventions or the certainty of outcome reporting in the full-text articles assessed. All disagreements were referred to the arbitrator (YDN). The arbitrator made the final decision by referring to the predetermined inclusion criteria outlined in the PICOS framework and based on the original article text.

We included trials that met the following criteria: (1) enrolled patients diagnosed with primary dysmenorrhea; (2) randomized participants to receive localized superficial heat therapy, defined as the application of any device or substance (e.g., electric heating pads, adhesive abdominal warmers, far-infrared belts, or moxibustion) aimed at transferring thermal energy continuously to the body, vs. a control (no treatment, placebo, or NSAIDs); (3) evaluated outcomes either in the immediate term (≤24 h) or analgesic effect or over the longer term (≥3 months) for repeated-use efficacy; and (4) reported measures of pain intensity or safety endpoints.

2.3 Data abstraction and risk of bias assessment

Four reviewers (YDN, LYY, HZY, CZY) extracted data from each eligible trial sequentially, ensuring they faced away from each other during the process. We gathered information on study characteristics, including author name, year of publication, study location, funding source, sample size, and length of follow-up, as well as intervention characteristics and all patient-important outcomes.

In cases where a study reported outcomes at multiple time points, we selected the most commonly reported follow-up period among the eligible trials. To account for within-person variability, we abstracted change scores from baseline; end scores were used only when change scores were not available. Additionally, when multiple instruments or questionnaires were employed to measure a common outcome (such as pain), we abstracted data solely for the most frequently used instrument across the eligible studies.

Three reviewers (HZY, LYY, CZY) independently assessed the risk of bias using a modified Cochrane Risk of Bias Tool 1.0 (14, 15). The tool assessed the following domains: random sequence generation; allocation concealment; blinding of study participants, healthcare providers, and outcome assessors; incomplete outcome data (≥20% missing data was considered high risk of bias); and other potential sources of bias. For each item, responses were scored as “definitely or probably yes” (low risk of bias) or “definitely or probably no” (high risk of bias). Disagreements between reviewers were resolved through discussion and, if necessary, by third-party adjudication (see Supplementary Table 2).

2.4 Data synthesis

For dichotomous outcomes, we calculated the relative risk (RR) and its corresponding 95% confidence interval (CI). For continuous outcomes, we calculated the weighted mean difference (WMD) and its corresponding 95%CI after we converted all the pain intensity data to the 10 cm visual analog scale (VAS) for pain (16). 1.5 cm was considered the minimal clinical important difference (MID) of pain intensity (17). We calculated the modeled risk difference (RD) value for comparisons to make the results easier to be understood.

We used a DerSimonian-Laird random effects model for all meta-analyses. Data were analyzed with STATA software version 17 (Stata Corp, College Station, TX, USA).

2.5 Certainty of evidence

We evaluated the certainty of evidence for all outcomes using the GRADE framework (Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development, and Evaluations) (18). Evidence from randomized controlled trials (RCTs) is initially rated as high certainty but was subject to downgrading by one or more levels (to moderate, low, or very low) following assessment across five domains: risk of bias, inconsistency, indirectness, imprecision, and publication bias—the latter evaluated through visual inspection of funnel plot asymmetry where ≥10 studies contributed to a meta-analysis. We defined it imprecise when 95% CIs of pain intensity contained either half MID (0.75 cm) or 0 cm, and 95% CIs of adverse events included no difference (RR = 1).

3 Results

3.1 Search results and study characteristics

We screened 2,733 citations, identifying 57 eligible trials (19–75) involving 5,359 participants (search flow shown in Figure 1). The median of the mean ages reported across the 53 trials (19–25, 27–47, 49–57, 59–74) that provided age data was 22.3 years. Among the 44 trials (19–24, 27, 28, 30–34, 37–44, 47, 50–55, 57–64, 66, 68–74) reporting the duration of primary dysmenorrhea, the median of the mean durations was 44 months. Of the studies reporting location, 54 were conducted in Asia (19–28, 30–44, 46–74), two in Europe (29, 75), and one in South America (45). Twenty-eight trials (24–26, 29–34, 38, 40, 42, 45, 46, 48, 49, 52, 53, 55, 56, 59, 61, 64, 66–68, 73, 74) compared heat therapy with a control group [three (26, 29, 45) assessing short-term effects], and 24 trials (21–23, 27, 29, 35, 37, 39, 41, 44, 47, 50, 51, 54, 57, 58, 60, 62, 65, 69–72, 75) compared heat therapy with NSAIDs [two (29, 60) assessing short-term effects] (see Table 1).

Figure 1

Search flowchart.

Table 1

| Study | Intervention | Control | Funding | Country | Number of participants at baseline, n | Length of follow-up, days | Mean duration of condition (SD), months | Mean age (SD), years |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ma G 2002 (19) | Microwave therapy | Ibuprofen | NR | China | 120 | 90 | 24 (4.23) | 19 (2.73) |

| Zhang SM 2008 (20) | TDP & Moxi | Indometacin | NR | China | 98 | 90 | 46.76(NR) | 19.2 (NR) |

| Liu C 2011 (21) | Moxi | Ibuprofen | NR | China | 80 | 90 | 68.2 (35.69) | 21.22 (5.86) |

| Sun GY 2012 (22) | Moxi & Usual care | Ibuprofen & Usual care | NR | China | 60 | 90 | 60 (NR) | 23 (NR) |

| Lai J 2012 (23) | Super Lizer | Indometacin | NR | China | 248 | 90 | 41.3 (17.02) | 17.7 (2.25) |

| Li P 2012 (24) | Moxi | Blank | NR | China | 50 | 90 | 74.6 (32.09) | 21.9 (1.92) |

| Hou K 2013 (25) | Moxi & NSAID | NSAID | NR | China | 78 | 90 | NR | 25.6(NR) |

| Li WJ 2013 (26) | Moxi | Blank | NR | China | 76 | 20 min | NR | NR |

| Wen XR 2013 (27) | Moxi | Ibuprofen | NR | China | 60 | 90 | 73.2 (36.6) | 22.3 (2.53) |

| Zhu L 2013 (28) | Moxi & Acupuncture | Acupuncture | NR | China | 60 | 90 | 72.7 (35.93) | 22.3 (2.53) |

| Potur DC 2014 (29) | Hot post | NSAID or Blank | Government | Turkey | 252 | 8h | NR | 59.62 (1.18) |

| Jing XX 2015 (30) | Moxi & Ibuprofen | Ibuprofen | NR | China | 100 | 90 | 27 (3.1) | 22.2 (2.14) |

| Qian SH 2015 (31) | RDP & Point application theropy | Point application therapy | NR | China | 52 | 90 | 41.3 (28.74) | 21 (3.96) |

| Ou Y 2015 (32) | Moxi & TCM | TCM | NR | China | 221 | 120 | 36 (NR) | 21.2 (NR) |

| Zhu LH 2015 (33) | Moxi | Blank | Government | China | 64 | 90 | 59.6 (20.25) | 20.3 (1.6) |

| Li Y 2017 (34) | Moxi & Usual care | Usual care | Government | China | 70 | 90 | 25.5 (12.58) | 20.3 (1.05) |

| Yang MX 2017 (35) | Moxi | Ibuprofen | Government | China | 152 | 90 | NR | 23 (2.92) |

| Hao MM 2017 (36) | Moxi | Painkiller | NR | China | 80 | 90 | NR | 19.7 (NR) |

| Wang LY 2018 (37) | Moxi | Ibuprofen | NR | China | 120 | 90 | 78.5 (39.76) | 22.3 (2.63) |

| Chen ZH 2018 (38) | Moxi & Acupuncture | Acupuncture | NR | China | 93 | 120 | 27.2 (14.23) | 22.8 (3.1) |

| Li C 2018 (39) | Moxi | Ibuprofen | NR | China | 72 | 90 | 54.7 (41.75) | 23 (1.42) |

| Li XJ 2018 (40) | Moxi | Blank | Government | China | 155 | 90 | 57 (5.39) | 20 (0.5) |

| Song J 2018 (41) | Moxi | Ibuprofen | NR | China | 60 | 90 | 60.1 (27.77) | 23.6 (3.44) |

| Xian SW 2018 (42) | Moxi & Acupuncture | Acupuncture | Government | China | 64 | 180 | 37.9 (32.13) | 20.6 (1.42) |

| Yan LH 2018 (43) | Moxi & Ibuprofen | Ibuprofen | NR | China | 106 | 90 | 5.4 (0.6) | 24.7 (4.64) |

| Chen CX 2018 (44) | Moxi & Ibuprofen | Ibuprofen | Government | China | 60 | 120 | 17.5 (7.05) | 20.3 (1.62) |

| Machado AFP 2019 (45) | Thermal therapy & TENS | TENS | NR | Brazil | 44 | 24 h | NR | 22.6 (4.08) |

| Wang MJ 2019 (46) | Moxi & TCM | TCM | NR | China | 60 | 90 | NR | 24.4 (NR) |

| Huang W 2019 (47) | Moxi | Ibuprofen | Government | China | 100 | 90 | 36.8 (22.82) | 20.4 (1.6) |

| Li L 2019 (48) | Moxi & Usual care | Usual care | NR | China | 150 | 90 | NR | NR |

| Liao BD 2019 (49) | Moxi & Needle warming Moxi | Needle warming Moxi | NR | China | 120 | 120 | NR | 24 (3) |

| Jiang M 2020 (50) | Moxi | Ibuprofen | Government | China | 60 | 90 | 30.4 (4.42) | 22.2 (4.03) |

| Liu Q 2020 (51) | Moxi | Ibuprofen | Government | China | 100 | 90 | 48.2 (14.42) | 26.3 (4.98) |

| Liu LY 2020 (52) | Moxi | Blank | Government | China | 144 | 90 | 54 (6.8) | 20 (0.5) |

| Sun L 2020 (53) | Moxi & TCM | TCM | NR | China | 72 | 90 | 68 (27.45) | 26 (3.75) |

| Wei MP 2020 (54) | Moxi | Ibuprofen | NR | China | 102 | 90 | 23.4 (7.04) | 20.1 (2.34) |

| Zhou WY 2020 (55) | Moxi & TCM | TCM | NR | China | 146 | 90 | 38.6 (13.01) | 26.7 (1.87) |

| Song H 2021 (56) | Moxi & Acupuncture and cupping | Acupuncture and cupping | NR | China | 127 | 90 | NR | 22.2 (2.88) |

| Wei XH 2021 (57) | Moxi | Ibuprofen | NR | China | 80 | 90 | 32.9 (13.53) | 20.4 (1.83) |

| Pan WB 2022 (58) | Moxi | Ibuprofen | Government | China | 99 | 90 | 39.5 (18.83) | NR |

| Wang GQ 2022 (59) | Moxi & TCM | TCM | NR | China | 90 | 90 | 23.4 (7.33) | 21 (2.62) |

| Liang H 2022 (60) | Electromagnetic wave | Ibuprofen | NR | China | 40 | 30 min | 34 (4.73) | 19.2 (1.02) |

| Yang JQ 2022 (61) | Moxi & TCM | TCM | NR | China | 62 | 90 | 86.7 (35.72) | 27 (3.04) |

| Yang YF 2022 (62) | Moxi | Ibuprofen | NR | China | 60 | 90 | 47.6 (5.23) | 35 (5.19) |

| Zhan L 2022 (63) | Moxi | Ibuprofen | NR | China | 104 | 90 | 19.1 (14.58) | 23.4 (2.77) |

| Shen JW 2023 (64) | Moxi patch & TCM | TCM | Government | China | 60 | 90 | 49.2 (22.86) | 29.4 (4.14) |

| Lin SF 2023 (65) | TDP & Moxi | Indometacin | NR | China | 50 | 90 | NR | 18.1 (3.5) |

| Ma TT 2023 (66) | Moxi patch & TCM | TCM | NR | China | 90 | 180 | 58.8 (39.49) | 27.6 (5.32) |

| Wu JJ 2023 (67) | Moxi & Usual care | Usual care | Government | China | 76 | 90 | NR | 22 (2.48) |

| Lin WM 2023 (68) | Moxi | Ibuprofen | Government | China | 120 | 90 | 80.8 (38.49) | 24.9 (6.05) |

| Xing BB 2023 (69) | Moxi | Ibuprofen | NR | China | 66 | 90 | 81 (32.28) | 25.2 (2.56) |

| Yu SY 2024 (70) | Moxi patch & TCM | TCM | NR | China | 88 | 90 | 12.5 (3.4) | 26.4 (3.26) |

| Yang SR 2024 (71) | Moxi | Ibuprofen | Government | China | 120 | 90 | 84 (NR) | 26.3 (NR) |

| Xu YY 2024 (72) | Moxi | Ibuprofen | NR | China | 68 | 90 | 142 (77.94) | 29.4 (6.49) |

| Chen Y 2024 (73) | Moxi & Acupuncture | Acupuncture | NR | China | 64 | 90 | 10.1 (8.33) | 25.1 (4.02) |

| Qiu J 2025 (74) | Moxi & catgut embedding | Catgut embedding | Government | China | 90 | 90 | 8.4 (1.74) | 23.4 (2.6) |

| Ceylan D 2025 (75) | Thermal therapy | Dexketoprofen trometamol | Government | Turkey | 56 | 90 | NR | NR |

Baseline characteristics of included studies.

Moxi, moxibustion; TCM, traditional Chinese medicine; TDP, Thermal Diffusion Therapy.

3.2 Risk of bias

The risk of bias assessment for the 57 included trials is summarized in Supplementary Table 2. Random sequence generation was adequately reported in 36 trials (63%) (21, 27–29, 31–35, 39–42, 44, 45, 47, 49–53, 55–58, 60, 62, 64–69, 71, 72, 74), suggesting a low risk of selection bias for this domain in these studies. However, allocation concealment was implemented in only 17 trials (30%) (21, 27–29, 31–35, 39–42, 45, 52, 55, 74), potentially compromising 1.5 cm was considered the minimal clinica integrity. Only 3 trials (5%) (45, 52, 74) blinded participants, and 3 (5%) (28, 40, 45) blinded healthcare providers. This high risk of performance bias means that the expectation of receiving a therapeutic intervention (heat) could have influenced participants' reporting of pain relief. Similarly, blinding of outcome assessors and data analysts was reported in only 6 trials (11%) (28, 33, 35, 40, 41, 52), constituting a significant source of detection bias for the subjective outcome of self-reported pain. Importantly, no trials had ≥20% missing data, which minimizes bias from incomplete outcomes and strengthens the robustness of the pooled analysis.

3.3 Heat therapy vs. blank control

3.3.1 Pain analgesia over 3 months

Low-certainty evidence (25 RCTs, 2,393 patients) (24, 25, 30–34, 38, 40, 42, 46, 48, 49, 52, 53, 55, 56, 59, 61, 64, 66–68, 73, 74) showed that compared with blank intervention, patients with dysmenorrhea who received heat treatment may have experienced more pain relief (WMD −1.85 cm, 95% CI −2.29 to −1.41 cm; the modeled RD 21%, 95% CI 19% to 22%) (see Tables 2, 3; Figure 2).

Table 2

| Comparison | Outcome | Time point | Certainty of evidence | Result (heat vs. comparator) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Heat vs. blank control | Pain relief (VAS, cm) | ≥3 months | Low | Superior to control (WMD −1.85 cm, 95% CI: −2.29 to −1.41) |

| Pain relief (VAS, cm) | ≤24 h | Low | Superior to control (WMD −3.52 cm, 95% CI: −5.01 to −2.02) | |

| Adverse effects | Various | Low | Little to no difference (RR 1.34, 95% CI: 0.44 to 4.16) | |

| Heat vs. NSAIDs | Pain relief (VAS, cm) | ≥3 months 24 h | Low | Similar efficacy (WMD −1.10 cm, 95% CI: −1.51 to −0.70) |

| Pain relief (VAS, cm) | ≤24 h | Low | Similar efficacy (WMD −1.5 cm, 95% CI: −2.86 to −0.15) | |

| Adverse effects | Various | Moderate | Safer than NSAIDs (RR 0.3, 95% CI: 0.15 to 0.59) |

Summary of key findings: heat therapy vs. control/NSAIDs for primary dysmenorrhea.

Table 3

| No. of trials (No. of patients) | Follow-up, weeks | Risk of bias | Inconsistency | Indirectness | Imprecision | Publication bias | Treatment association (95% CI) | Overall quality of evidence | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pain: 0–10 cm VAS for pain (3 months effect); lower is better; MID = 1.5 cm | |||||||||

| 25 (2,393) | Seriousa | Not seriousb, I2=95.95% | Not serious | Not serious | Seriousc | Achieved at or above MID | |||

| Heat 98% | Control 77% | Low | |||||||

| Modeled RD 21% (19%, 22%) | |||||||||

| WMD −1.85 (−2.29, −1.41) | |||||||||

| Pain: 0–10 cm VAS for pain (24 h effect); lower is better; MID = 1.5 cm | |||||||||

| 3 (248) | Seriousa | Not seriousb, I2 = 89.10% | Not serious | Seriousd | NA | Achieved at or above MID | Low | ||

| Heat 96% | Control 51% | ||||||||

| Modeled RD 45% (33%, 48%) | |||||||||

| WMD −3.52 (−5.01, −2.02) | |||||||||

| Adverse effects | |||||||||

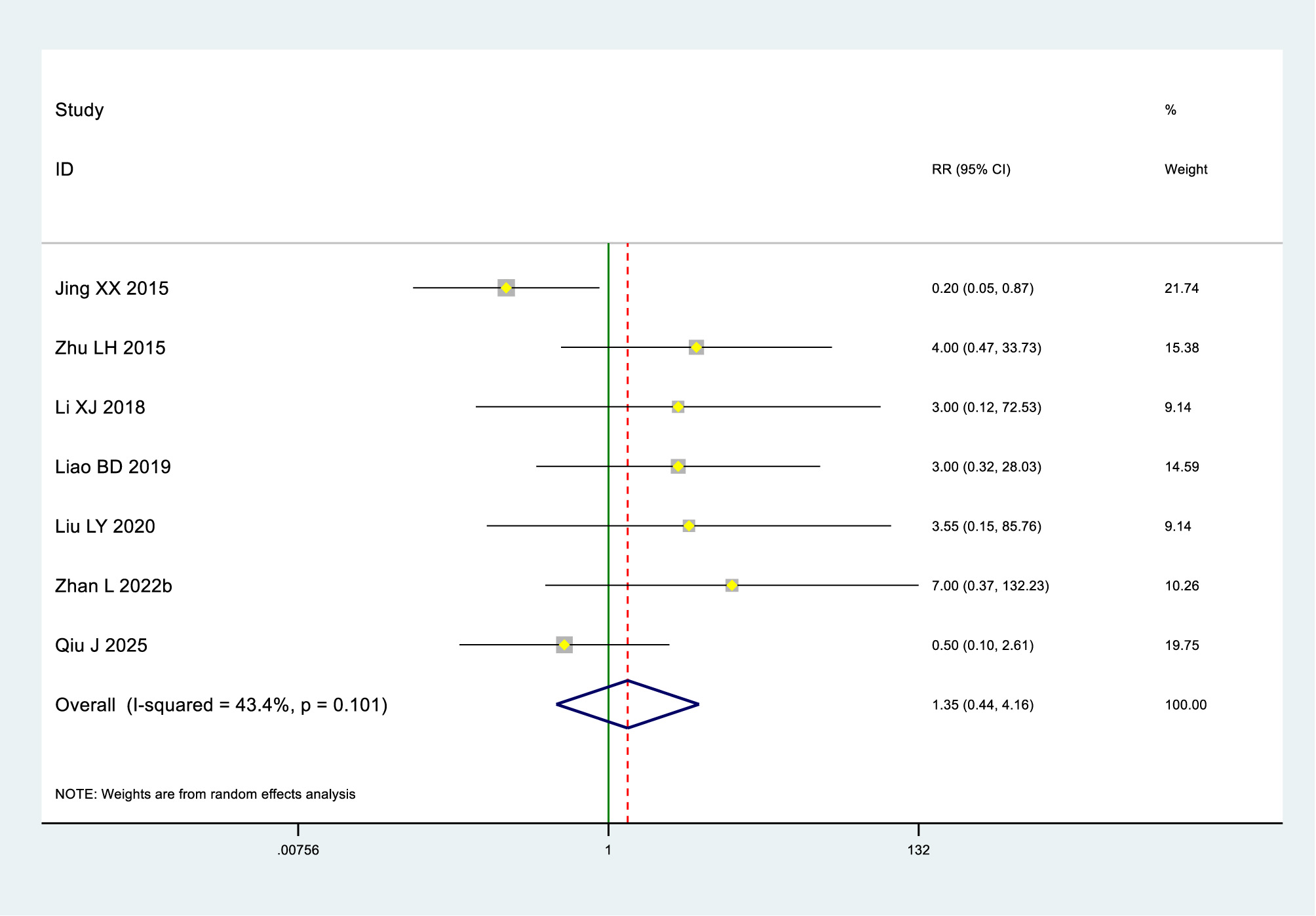

| 7 (784) | Seriousa | Not serious, I2 = 43.4% | Not serious | Seriouse | NA | RR 1.35 (0.44, 4.16) | Low | ||

Grade evidence profile of Heat therapy vs. the blank control on primary dysmenorrhea.

NA, not available. aHigh risk of bias in blinding and randomization bHeterogeneity of more than 50%, but all research effects pointed in the same direction and there were only variations in effect sizes cVisual inspection of the funnel plot indicated asymmetry, suggesting a potential risk of bias (see Supplementary Figure 1). dSmall sample size. e95%CI cross the null line.

Figure 2

Long-term pain relief: heat therapy group vs. blank group.

3.3.2 Pain analgesia within 24 h

Low-certainty evidence (3 RCTs, 248 patients) (26, 29, 45) suggested that compared with blank intervention, patients with dysmenorrhea who received heat treatment experienced more pain relief (WMD −3.52 cm, 95% CI −5.01 to −2.02 cm; the modeled RD 45%, 95% Cl 33% to 48%) (see Tables 2, 3; Figure 3).

Figure 3

Short-term pain relief: heat therapy group vs. blank group.

3.3.3 Adverse effects

Low-certainty evidence (7 RCTs, 784 patients) (30, 33, 40, 49, 52, 63, 74) indicated little to no difference in adverse effects between heat therapy and blank intervention for primary dysmenorrhea (RR 1.34, 95% Cl 0.44–4.16) (see Tables 2, 3; Figure 4).

Figure 4

Adverse effects in the heat therapy and bank groups.

3.4 Heat therapy vs. NSAIDs

3.4.1 Pain analgesia over 3 months

Low-certainty evidence (22 RCTs, 1,938 patients) (21–23, 27, 35, 37, 39, 41, 44, 47, 50, 51, 54, 57, 58, 62, 65, 69–72, 75) suggested that heat therapy and NSAIDs may be comparable in relieving pain, with WMD −1.10 cm (95% CI −1.51 to −0.70 cm), modeled RD 4% (95% CI 3% to 4%) (see Tables 2, 4; Figure 5).

Table 4

| No. of trials (No. of patients) | Follow-up, weeks | Risk of bias | Inconsistency | Indirectness | Imprecision | Publication bias | Treatment association (95% CI) | Overall quality of evidence | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pain: 0–10 cm VAS for pain (long-lasting effect); lower is better; MID = 1.5 cm | |||||||||

| 22 (1,938) | Seriousa | Not seriousb, I2 = 91.55% | Not serious | Not serious | Seriousc | Achieved at or above MID | |||

| Heat 100% | Control 96% | Low | |||||||

| Modeled RD 4% (3%, 4%) | |||||||||

| WMD −1.10 (−1.51, −0.70) | |||||||||

| Pain: 0–10 cm VAS for pain (short-lasting effect); lower is better; MID = 1.5 cm | |||||||||

| 2 (167) | Seriousd | Not seriouse, I2 = 80.77% | Not serious | Seriousf | NA | Achieved at or above MI | Low | ||

| Heat 93% | Control 77% | ||||||||

| Modeled RD 16% (2%, 21%) | |||||||||

| WMD −1.50 (−2.86, −0.15) | |||||||||

| Adverse effects | |||||||||

| 8 (728) | Seriousa | Not serious, I2 = 0% | Not serious | Not serious | NA | RR 0.30 (0.15, 0.59) | Moderate | ||

Grade evidence profile of Heat therapy vs. medication on primary dysmenorrhea.

NA, not available. aHigh risk of bias in blinding and randomization. bHeterogeneity of more than 50%, but all research effects pointed in the same direction and there were only variations in effect sizes. cVisual inspection of the funnel plot indicated asymmetry, suggesting a potential risk of bias (see Supplementary Figure 2). dHigh risk of bias in blinding. eWe downgraded for Imprecision but not for Inconsistency, as we judged the consistent results here would not substantially impact the overall findings. fSmall sample size and 95% CI cross the half of the MID value.

Figure 5

Long-term pain relief: heat therapy group vs. NSAIDs group.

3.4.2 Pain analgesia within 24 h

Low-certainty evidence (2 RCTs, 167 patients) (29, 60) suggested that heat therapy and NSAIDs may show similar efficacy in pain relief, with WMD −1.5 cm (95% CI −2.86 to −0.15 cm), modeled RD 16% (95% CI 2% to 21%) (see Tables 2, 4; Figure 6).

Figure 6

Short-term pain relief: heat therapy group vs. NSAIDs group.

3.4.3 Adverse effects

Moderate-certainty evidence (8 RCTs, 728 patients) (19, 20, 27, 28, 36, 43, 47, 63) indicated that heat therapy probably reduced the risk of adverse effects compared with NSAIDs in primary dysmenorrhea (RR 0.3, 95% Cl 0.15 to 0.59) (see Tables 2, 4; Figure 7).

Figure 7

Adverse effects in the Heat therapy and NSAIDs groups.

4 Discussion

4.1 Overall findings

Compared to no treatment, heat therapy reduces pain in primary dysmenorrhea with comparable safety. When compared to NSAIDs, heat therapy demonstrates minimal difference in pain intensity but is probably associated with fewer adverse events. These treatment outcomes remain consistent across both short-term (24-h) and long-term (3-month) assessments.

4.2 Relation to other studies

We have identified two systematic reviews in the literature addressing heat therapy for primary dysmenorrhea (76, 77); however, we excluded 6 RCTs for specific reasons. The first meta-analysis (76) included three RCTs on thermotherapy. One trial was excluded due to a lack of baseline data (78). The other two (79, 80), with treatment durations of 1 and 2 months, were also excluded. The second meta-analysis (77) included six RCTs (29, 78, 80–83), only one of which was included in our analysis (29). The other five trials were excluded due to the absence of extractable outcome measures (78, 80, 81), unavailable resources (82), or non-compliant interventions (83). A detailed breakdown is provided in Supplementary Table 3.

Earlier systematic reviews offered valuable preliminary insights by suggesting heat therapy might be effective and potentially comparable to analgesic medication. However, their conclusions were notably constrained: Jo and Lee's analysis, while indicating superiority over placebo, was limited to only 6 RCTs (77); Igwea et al. identified merely 3 heat therapy trials, were unable to perform a direct comparative meta-analysis, and ultimately highlighted the need for more robust evidence (76).

Our study comprehensively addresses these limitations through key advancements: a markedly expanded evidence base (57 RCTs) enabling more precise and generalizable treatment estimates; broader intervention diversity encompassing microwave therapy, electromagnetic wave therapy, moxibustion, and hot packs beyond previous narrow focus; and demonstration of consistent therapeutic benefits across both immediate (24-h) and sustained (3-month) timeframes—a previously unexamined dimension. Methodologically, the systematic application of the GRADE framework provides rigorous evidence certainty assessment, thereby substantiating prior hypotheses and establishing a more reliable foundation for positioning heat therapy as a viable non-pharmacological treatment for primary dysmenorrhea.

4.3 Strengths and limitations

This review has several strengths. We predefined the MIDs to visually demonstrate between-group differences and evaluate the clinical significance of the findings. The calculation of MID-derived risk differences (RDs) further enhanced the interpretation of the clinical feasibility of treatment effects. Moreover, our study overcomes the limitations of previous analyses by comprehensively incorporating diverse thermotherapy modalities and leveraging a robust sample size, thereby yielding more precise and generalizable estimates.

Nevertheless, several limitations warrant consideration. The methodological quality of many included trials was compromised by inadequate randomization and concealment of allocation. Furthermore, significant heterogeneity was observed in some analyses, likely stemming from clinical diversity in patient populations and variations in heat therapy protocols. Finally, the predominance of studies conducted in Asian populations may limit the generalizability of our findings to other regions.

4.4 Implications

Our findings provide evidence for informing a stepped-care approach to managing primary dysmenorrhea. During acute episodes, local heat therapy using modalities such as hot water bottles or self-heating patches can provide immediate pain relief comparable to NSAIDs, with a superior safety profile. This offers an ideal first-line option for patients who cannot or prefer not to use medication. During the intermenstrual period, regular application of heat therapies like moxibustion or infrared therapy can serve as an effective preventive measure. Long-term adherence may reduce the frequency and intensity of pain episodes and decrease reliance on analgesic medications. For patients with severe pain, a “heat therapy-first, medication-as-supplement” combination strategy could be considered—employing heat therapy both preventively and during acute phases, reserving short-term NSAID use only for peak pain levels to optimize both efficacy and safety.

From a research perspective, the application of MIDs in our meta-analysis offers a concrete method for evaluating the clinical significance of future findings. However, the promising results are constrained by the low certainty of evidence and prevalent risk of bias in existing studies.

Future research should therefore prioritize high-quality, adequately powered RCTs that are specifically designed to overcome these limitations. We recommend that future trials: (1) calculate sample sizes based on the established MIDs for pain scales to ensure sufficient statistical power; (2) predefine and consistently apply a standardized heat intervention protocol (specifying temperature, application site, duration, and treatment frequency) to reduce heterogeneity; (3) adhere to the CONSORT reporting guidelines, providing clear descriptions of randomization, allocation concealment, and blinding methods; and (4) systematically record and report all adverse events to better establish the long-term safety profile of repeated heat application. Such rigorously generated evidence is crucial to confirm these findings and establish clear, evidence-based clinical guidelines.

5 Conclusion

Compared to no treatment, heat therapy is likely to reduce pain intensity both during prophylaxis and acute episodes. When compared to NSAIDs, heat therapy may achieve comparable analgesic efficacy with a superior safety profile.

Statements

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author contributions

DY: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Software, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. YL: Data curation, Formal analysis, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft. ZC: Data curation, Investigation, Resources, Supervision, Writing – review & editing. ZH: Formal analysis, Methodology, Software, Validation, Writing – review & editing. XL: Funding acquisition, Project administration, Resources, Supervision, Writing – review & editing. WZ: Investigation, Software, Visualization, Writing – review & editing. KM: Investigation, Visualization, Writing – review & editing. WM: Investigation, Methodology, Writing – review & editing. LL: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Methodology, Project administration, Supervision, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declared that financial support was received for this work and/or its publication. This study was funded by the Chengdu University of Traditional Chinese Medicine University-Institute Joint Innovation Fund (Grant No. LH202402049) and Sichuan provincial project (Grant No. 2022YFS0401).

Conflict of interest

The author(s) declared that this work was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declared that generative AI was not used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fmed.2025.1730505/full#supplementary-material

References

1.

Iacovides S Avidon I Baker FC . What we know about primary dysmenorrhea today: a critical review. Hum Reprod Update. (2015) 21:762–78. doi: 10.1093/humupd/dmv039

2.

Ferries-Rowe E Corey E Archer JS . Primary dysmenorrhea: diagnosis and therapy. Obstet Gynecol. (2020) 136:1047–58. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000004096

3.

Dawood MY . Primary dysmenorrhea: advances in pathogenesis and management. Obstet Gynecol. (2006) 108:428–41. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000230214.26638.0c

4.

Ju H Jones M Mishra G . The prevalence and risk factors of dysmenorrhea. Epidemiol Rev. (2014) 36:104–13. doi: 10.1093/epirev/mxt009

5.

Marjoribanks J Ayeleke RO Farquhar C Proctor M . Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs for dysmenorrhoea. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. (2015) 2015:Cd001751. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD001751.pub3

6.

Owen PR . Prostaglandin synthetase inhibitors in the treatment of primary dysmenorrhea. Outcome trials reviewed. Am J Obstet Gynecol. (1984) 148:96–103. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9378(84)80039-3

7.

Essex MN Zhang RY Berger MF Upadhyay S Park PW . Safety of celecoxib compared with placebo and non-selective NSAIDs: cumulative meta-analysis of 89 randomized controlled trials. Expert Opin Drug Saf. (2013) 12:465–77. doi: 10.1517/14740338.2013.780595

8.

Xu T Hui L Juan YL Min SG Hua WT . Effects of moxibustion or acupoint therapy for the treatment of primary dysmenorrhea: a meta-analysis. Altern Ther Health Med. (2014) 20:33–42.

9.

Abaraogu UO Igwe SE Tabansi-Ochiogu CS Duru DO . A systematic review and meta-analysis of the efficacy of manipulative therapy in women with primary dysmenorrhea. Explore (NY). (2017) 13:386–92. doi: 10.1016/j.explore.2017.08.001

10.

Elboim-Gabyzon M Kalichman L . Transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (TENS) for primary dysmenorrhea: an overview. Int J Womens Health. (2020) 12:1–10. doi: 10.2147/IJWH.S220523

11.

López-Liria R Torres-Álamo L Vega-Ramírez FA García-Luengo AV Aguilar-Parra JM Trigueros-Ramos R et al . Efficacy of physiotherapy treatment in primary dysmenorrhea: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2021) 18:7832. doi: 10.3390/ijerph18157832

12.

Putney DJ Malayer JR Gross TS Thatcher WW Hansen PJ Drost M . Heat stress-induced alterations in the synthesis and secretion of proteins and prostaglandins by cultured bovine conceptuses and uterine endometrium. Biol Reprod. (1988) 39:717–28. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod39.3.717

13.

Tao XG Bernacki EJ A . randomized clinical trial of continuous low-level heat therapy for acute muscular low back pain in the workplace. J Occup Environ Med. (2005) 47:1298–306. doi: 10.1097/01.jom.0000184877.01691.a3

14.

Higgins JP Altman DG Gøtzsche PC Jüni P Moher D Oxman AD et al . The Cochrane Collaboration's tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ. (2011) 343:d5928. doi: 10.1136/bmj.d5928

15.

Akl EA Sun X Busse JW Johnston BC Briel M Mulla S et al . Specific instructions for estimating unclearly reported blinding status in randomized trials were reliable and valid. J Clin Epidemiol. (2012) 65:262–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2011.04.015

16.

Thorlund K Walter SD Johnston BC Furukawa TA Guyatt GH . Pooling health-related quality of life outcomes in meta-analysis-a tutorial and review of methods for enhancing interpretability. Res Synth Methods. (2011) 2:188–203. doi: 10.1002/jrsm.46

17.

Wang Y Devji T Carrasco-Labra A King MT Terluin B Terwee CB et al . A step-by-step approach for selecting an optimal minimal important difference. Bmj. (2023) 381:e073822. doi: 10.1136/bmj-2022-073822

18.

Santesso N Glenton C Dahm P Garner P Akl EA Alper B et al . GRADE guidelines 26: informative statements to communicate the findings of systematic reviews of interventions. J Clin Epidemiol. (2020) 119:126–35. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2019.10.014

19.

Ma Gang TY . Microwave therapy for 60 cases of primary dysmenorrhea. J Guangxi Med Univ. (2002) 2002:680–1. doi: 10.16190/j.cnki.45-1211/r.2002.05.036

20.

Siming Z Yuansheng N Baozhu Q Jinshu H Ruinong Z . A study on the nursing of primary dysmenorrhea with TDP combined with moxibustion. Bright Trad Chin Med. (2008) 2008:102–3. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1003-8914.2008.01.080

21.

Cheng L Haiyan Z . Therapeutic effect of moxibustion on primary dysmenorrhea due to damp-cold retention. World J Acupunct-Moxibust. (2011) 21:1–4.

22.

Guoyao S . Clinical efficacy of moxibustion box warm moxibustion in the treatment of primary dysmenorrhea. Inner Mongolia J Trad Chin Med. (2012) 31:25–6. doi: 10.16040/j.cnki.cn15-1101.2012.20.036

23.

Jian L Juan L . Clinical research on the treatment of primary dysmenorrhea with super laser. Clin Med Eng. (2012) 19:682–4. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1674-4659.2012.05.0682

24.

Pei L Sanqing Z Yuan L Feng J Sensen L . The effect of moxibustion at different time points on primary dysmenorrhea. J Fujian Univ Trad Chin Med. (2012) 22:1–3. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1004-5627.2012.05.001

25.

Ke H . A preliminary study on the treatment of cold-type dysmenorrhea with acupuncture. Everyone's Health (Acad Ed). (2013) 7:171.

26.

Weijiang L Andi W Xiaowen C Jie C Chen Z . Study on the abdominal infrared thermal imaging characteristics of patients with primary dysmenorrhea treated by acupuncture at dihou point. Shanghai J Acupunct. (2012) 31:659–61.

27.

Xinru W . Clinical study on the treatment of primary dysmenorrhea with acupuncture. J Chengdu Univ Trad Chin Med. (2013).

28.

Lan Z . Clinical analysis of 35 cases treated with acupuncture and moxibustion for dysmenorrhea. Chin Med J. (2013) 48:98–9. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1008-1070.2013.07.045

29.

Potur DC Kömürcü N . The effects of local low-dose heat application on dysmenorrhea. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol. (2014) 27:216–21. doi: 10.1016/j.jpag.2013.11.003

30.

Xinxin J Hang L Hang Y . The efficacy and nursing measures of moxibustion in the treatment of primary dysmenorrhea. Biotechnol World. (2015) 2015:138+40.

31.

Shanhai Q Lifang T Yin Z Ting J . Observation on the therapeutic effect of three-heat plaster combined with TDP irradiation in the treatment of cold-dampness stagnation type primary dysmenorrhea. Shanghai J Acupunct. (2015) 34:1067–9. doi: 10.13460/j.issn.1005-0957.2015.11.1067

32.

Yan O . The effect of moxibustion combined with Taohong Sibu Decoction on serum ET-1 and NO levels in patients with dysmenorrhea. J Changchun Univ Trad Chin Med. (2015) 31:582–4. doi: 10.13463/j.cnki.cczyy.2015.03.053

33.

Lihua Z . A randomized controlled study on the therapeutic effect of scheduled acupuncture for primary dysmenorrhea. J Chengdu Univ Trad Chin Med. (2015).

34.

Yan L Jing Z Yuwen Y Na L Zhenzhen Z . The effect of moxibustion on the symptoms of primary dysmenorrhea and sleep quality. J Mudanjiang Med Univ. (2017) 38:143–6. doi: 10.13799/j.cnki.mdjyxyxb.2017.03.052

35.

Yang M Chen X Bo L Lao L Chen J Yu S et al . Moxibustion for pain relief in patients with primary dysmenorrhea: a randomized controlled trial. PLoS ONE. (2017) 12:e0170952. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0170952

36.

Meimei H . Observation on the efficacy of moxibustion with moxa sticks in treating dysmenorrhea caused by cold-dampness stagnation. Chin Med Modern Dist Educ China. (2017) 15:108–9. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1672-2779.2017.11.047

37.

Lingyan W Hongpei C . Clinical observation on 60 cases of primary dysmenorrhea treated with grain-impregnated moxibustion. N Trad Chin Med. (2018) 50:174–6. doi: 10.13457/j.cnki.jncm.2018.07.052

38.

Zhihui C . A randomized parallel controlled study on the treatment of primary dysmenorrhea with acupuncture combined with needling. Pract J Trad Chin Intern Med. (2018) 32:55–7. doi: 10.13729/j.issn.1671-7813.Z20170114

39.

Cheng l Xinjian M Xiaoli W . Clinical study on the treatment of primary dysmenorrhea of the cold-damp accumulation type by moxibustion. J Acupunct Clin Pract. (2018) 34:48–51. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1005-0779.2018.06.015

40.

Xiaoji L . A randomized controlled trial of time-based acupuncture for elective treatment of primary dysmenorrhea based on the theory of time acupuncture. J Chengdu Univ Trad Chin Med. (2018).

41.

Juan S . Clinical study on the treatment of primary dysmenorrhea of cold-dampness stagnation type by moxibustion combined with “Ziwu flowchart of nailing the heavenly stems method”. J Chengdu Univ Trad Chin Med. (2018).

42.

Shuwen X Xinyan Z Chunhui L Xianying L . Observation on the therapeutic effect of silver needles combined with moxibustion in treating primary dysmenorrhea in female college students. Matern Child Health Care China. (2018) 33:2817–9. doi: 10.7620/zgfybj.j.issn.1001-4411.2018.12.61

43.

Lianhua Y Ting L . Observation on the therapeutic effect of warm moxibustion with moxibustion box on primary dysmenorrhea. Essent Read Health. (2018) 2018:187–8.

44.

Chunxia C Chen W Cong D Wei X Meizhen Z . Clinical research on the treatment of primary dysmenorrhea of cold coagulation syndrome with moxibustion. Popul Technol. (2018) 20:68–71. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1008-1151.2018.08.024

45.

Machado AFP Perracini MR Rampazo É P Driusso P Liebano RE . Effects of thermotherapy and transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation on patients with primary dysmenorrhea: a randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind clinical trial. Complement Ther Med. (2019) 47:102188. doi: 10.1016/j.ctim.2019.08.022

46.

Meijuan W Juncheng D . Observation on the clinical efficacy of danggui sini decoction combined with heat-sensitive acupuncture in the treatment of primary dysmenorrhea. Jiangxi Trad Chin Med. (2019) 50:57–8.

47.

Wei H . Analysis of the therapeutic effect of moxibustion on primary dysmenorrhea in female college students. Healthc Wellness Guide. (2019) 2019:345. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1006-6845.2019.08.329

48.

Ling L Guojuan S Xueli S Yalan W Zhi L Ping X . Observation on the therapeutic effect of acupuncture moxibustion combined with steam therapy in the treatment of primary dysmenorrhea (cold stagnation and blood stasis syndrome) in 150 cases. J Sichuan Trad Chin Med. (2019) 37:210–2.

49.

Bodan L Yuane L Zhimou P Chang Z Chao L Jingjing H et al . Observation on the therapeutic effect of acupoint moxibustion at shangwan combined with warm needling at guanyuan and sanyinjiao for the treatment of primary dysmenorrhea. Chin Acupunct Moxibust. (2019) 39:367–70+76. doi: 10.13703/j.0255-2930.2019.04.006

50.

Mei J Liping D Qingxia L Xiuwu H Chenying D . A controlled study on the intervention of long-needle moxibustion for primary dysmenorrhea of the cold-coagulation and blood-stasis type. Jiangxi Med. (2020) 55:568–70+611. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1006-2238.2020.05.025

51.

Qian L Yonghong L Yuting L Muying Z Haini Z Jie Q et al . clinical observation on the treatment of cold-induced primary dysmenorrhea with angelica sinensis and ginger lamb soup. Chin Folk Med. (2020) 28:65–9. doi: 10.19621/j.cnki.11-3555/r.2020.2426

52.

Liu LY Li XJ Wei W Guo XL Zhu LH Gao FF et al . Moxibustion for patients with primary dysmenorrhea at different intervention time points: a randomized controlled trial. J Pain Res. (2020) 13:2653–62. doi: 10.2147/JPR.S270698

53.

Lian S . Clinical observation on the treatment of primary dysmenorrhea of cold-obstructed blood stasis type with Xiaodui Zhuyu decoction combined with acupuncture therapy. J Shanxi Univ Chin Med. (2020). 2020. doi: 10.27820/d.cnki.gszxy.2020.000165

54.

Meipan W Tingting A Shanyan Q Meiwu W . Analysis of the effect of acupuncture therapy on primary dysmenorrhea. Contemp Med J. (2020) 18:204–5. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.2095-7629.2020.09.150

55.

Wenya Z Yanmei Z Lezhang Z A . randomized controlled study on the treatment of dysmenorrhea of the cold-stagnation and blood-stasis type with Jinling Sishui Powder combined with Wenzheng acupuncture. Pract Gynecol Endocrinol Electr J. (2020) 7:49–50. doi: 10.16484/j.cnki.issn2095-8803.2020.09.030

56.

Hong S . TDP combined with acupuncture and cupping therapy for the treatment of 127 cases of primary dysmenorrhea in college students. Health Focus. (2021) 2021:140.

57.

Xiaohan W Shuo Q . Comparison of the effects of moxibustion and Western medicine in treating cold-type dysmenorrhea and their respective advantages. Healthc Wellness Guide. (2021) 2021:28–9.

58.

Weibin P Xiaomin L Qiumei C Nan L Yuqiong W . Efficacy of dual-sided thermal stimulation at lumbosacral and abdominal regions for primary dysmenorrhea with cold coagulation and blood stasis pattern in female university students. J Shanxi Univ Chin Med. (2022) 23:567–70. doi: 10.19763/j.cnki.2096-7403.2022.06.12

59.

Guoqin W Yueping S Shanshan C . Therapeutic effects of moxibustion combined with taohong siwu decoction on dysmenorrhea: a clinical analysis. Health Friend. (2022) 2022:142–3.

60.

Hui L Yun X . Analysis of the effect of specific electromagnetic wave therapy devices on primary dysmenorrhea. Chin Sci J Database (Citat Ed): Med Health Sci. (2022) 39:345–7. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1000-7369.2018.03.023

61.

Jieqiong Y Ying L . Clinical efficacy of dysmenorrhea formula combined with moxibustion for treating primary dysmenorrhea with cold coagulation and blood stasis pattern. Health Essent. (2022) 2022:27–8.

62.

Yifan Y Furong Z . Therapeutic efficacy of gynecological-specific moxibustion for primary dysmenorrhea with cold-dampness congelation pattern. Adv Clin Med. (2022) 12:477–82. doi: 10.12677/ACM.2022.121070

63.

Liang Z . Therapeutic impact of intensive moxibustion at baliao points on moderate-to-severe primary dysmenorrhea with cold-dampness congelation pattern. Pract Clin J Integr Trad Chin West Med. (2022) 22:107–9. doi: 10.13638/j.issn.1671-4040.2022.01.036

64.

Jiewen S Wenrong X Feiyun G . Clinical efficacy of modified Shao-Fu-Zhu-Yu decoction combined with governor vessel moxibustion patch for primary dysmenorrhea with cold coagulation and blood stasis pattern. J Women Children′s Health Guide. (2023) 2:31–3+49. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.2097-115X.2023.3.whbb202303010

65.

Shaofen L . The application of specific electromagnetic spectrum combined with moxibustion in primary dysmenorrhea. J Pract Gynecol Endocrinol. (2023) 10:90–2. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.2095-8803.2023.18.028

66.

Tingting M Yanzheng L . Therapeutic analysis of empirical dysmenorrhea decoction combined with moxibustion for dysmenorrhea with cold coagulation and blood stasis pattern. Chin Health Care. (2023) 41:37–40.

67.

Jiaojiao W Jiangyan X Lingli R Xiaoyi Z Shan L Longtao K et al . Nursing intervention of auricular acupoint pressing with seeds combined with portable moxibustion for primary dysmenorrhea in female university students. J Modern Med Health. (2023) 39:879–81. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1009-5519.2023.05.032

68.

Wenmin L Jisheng W . Clinical study on grain-sized moxibustion for primary dysmenorrhea with cold-dampness congelation pattern. Guangming J Chin Med. (2023) 38:2137–9. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1003-8914.2023.11.031

69.

Bianbian X . Clinical efficacy of heat-sensitive moxibustion for primary dysmenorrhea with cold coagulation and blood stasis pattern (2023). doi: 10.27282/d.cnki.gsdzu.2023.000195

70.

Shuying Y Li Z . Therapeutic effects of bottle gourd moxibustion for primary dysmenorrhea with cold coagulation and blood stasis pattern. Weekly Digest: Senior Care Weekly. (2024) 2024:116–8.

71.

Songran Y Yan X Yu S Shoubo Y Kaidi G Yalin L . Therapeutic efficacy of bian stone-mediated moxibustion for primary dysmenorrhea. J Women Children′s Health Guide. (2024) 3:26–9. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.2097-115X.whbb202410008

72.

Yaoyao X Li G Yiya Y . Clinical efficacy of Bagua-style umbilical-region moxibustion for primary dysmenorrhea with cold coagulation and blood stasis pattern. Res Integr Trad Chin West Med. (2024) 16:70–2. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1674-4616.2024.01.019

73.

Yao C . Chrono-acupuncture combined with heat-sensitive moxibustion for primary dysmenorrhea: a clinical case series of 32 patients. Chin Med. (2024) 13:173–8. doi: 10.12677/TCM.2024.131027

74.

Jing Q Zheng H Ping Y Zhaohua X . Clinical study on heat-sensitive moxibustion combined with acupoint catgut embedding for treating dysmenorrhea due to cold coagulation and blood stasis. Capit Med. (2025) 32:148–51. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1005-8257.2025.09.051

75.

Ceylan D Başer M . The effect of hot application with cherry seed belt on dysmenorrhoea: a randomized controlled trial. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. (2025) 311:114027. doi: 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2025.114027

76.

Igwea SE Tabansi-Ochuogu CS Abaraogu UO . TENS and heat therapy for pain relief and quality of life improvement in individuals with primary dysmenorrhea: a systematic review. Complement Ther Clin Pract. (2016) 24:86–91. doi: 10.1016/j.ctcp.2016.05.001

77.

Jo J Lee SH . Heat therapy for primary dysmenorrhea: a systematic review and meta-analysis of its effects on pain relief and quality of life. Sci Rep. (2018) 8:16252. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-34303-z

78.

Navvabi Rigi S Kermansaravi F Navidian A Safabakhsh L Safarzadeh A Khazaeian S et al . Comparing the analgesic effect of heat patch containing iron chip and ibuprofen for primary dysmenorrhea: a randomized controlled trial. BMC Women's Health. (2012) 12:25. doi: 10.1186/1472-6874-12-25

79.

Kim JI . Effect of heated red bean pillow application for college women with dysmenorrhea. Korean J Women Health Nurs. (2013) 19:67–74. doi: 10.4069/kjwhn.2013.19.2.67

80.

Ke YM Ou MC Ho CK Lin YS Liu HY Chang WA . Effects of somatothermal far-infrared ray on primary dysmenorrhea: a pilot study. Evid-Based Complement Altern Med. (2012) 2012:240314. doi: 10.1155/2012/240314

81.

Akin MD Weingand KW Hengehold DA Goodale MB Hinkle RT Smith RP . Continuous low-level topical heat in the treatment of dysmenorrhea. Obstet Gynecol. (2001) 97:343–9. doi: 10.1097/00006250-200103000-00004

82.

Akin M Price W Rodriguez G Jr Erasala G Hurley G Smith RP . Continuous, low-level, topical heat wrap therapy as compared to acetaminophen for primary dysmenorrhea. J Reprod Med. (2004) 49:739–45.

83.

Lee CH Roh JW Lim CY Hong JH Lee JK Min EG et al . multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial evaluating the efficacy and safety of a far infrared-emitting sericite belt in patients with primary dysmenorrhea. Complement Ther Med. (2011) 19:187–93. doi: 10.1016/j.ctim.2011.06.004

Summary

Keywords

primary dysmenorrhea, heat therapy, pain, NSAIDs, meta-analysis

Citation

Yuan D, Liu Y, Chen Z, Hu Z, Li X, Zhang W, Mao K, Ma W and Lan L (2026) Heat therapy for primary dysmenorrhea: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Front. Med. 12:1730505. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2025.1730505

Received

22 October 2025

Revised

15 November 2025

Accepted

12 December 2025

Published

23 January 2026

Volume

12 - 2025

Edited by

Pranay Wal, Pranveer Singh Institute of Technology, Pharmacy, India

Reviewed by

Hanish Singh Jayasingh Chellammal, Universiti Teknologi MARA, Malaysia

Manish Bhise, Sant Gadge Baba Amravati University, India

Updates

Copyright

© 2026 Yuan, Liu, Chen, Hu, Li, Zhang, Mao, Ma and Lan.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Lei Lan, lanlei@cdutcm.edu.cn

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.