Abstract

Introduction:

The physiological decline with advancing age also affects the aging of the spine. The practice of physical activity (PA) appears to protect against spine degeneration. Hence, the aim of this study was to analyze the morphological differences of the spine in older women, comparing subjects with different levels of PA.

Methods:

Participants were divided into the three following groups based on the amount of PA practiced: low active (LA); moderate active (MA); high active (HA). The levels of PA were measured using the International Physical Activity Questionnaire—Short Form (IPAQ–SF). The spine morphology of each participant was assessed through a non-invasive, 3D optoelectronic detection system using the Light Detection and Ranging (LIDAR) technology. Spine parameters in the frontal and sagittal planes were considered for comparisons.

Results:

No significant differences in spine parameters in the frontal plane among the 3 groups were found. In the sagittal plane, we found a significant difference on the spine sagittal imbalance parameter (F(2, 40) = 6.17; p = 0.005), with the highest spine sagittal imbalance in the LA group. Furthermore, in the sagittal plane, we detected a significant difference in the spine inclination parameter (F(2, 40) = 5.93; p = 0.006), with the highest spine inclination in the LA group.

Conclusion:

Our results showed that older women who engage d in lower levels of PA exhibited some altered spinal sagittal parameters compared to peers with moderate and high levels of PA, suggesting that PA may contribute to maintain spinal sagittal alignment and preserve spinal sagittal balance.

1 Introduction

Aging is a physiological process which occurs in the human over time and is characterized by progressive and irreversible changes on both the structural and functional domains (1). Among the psychological aspects, the decline in cognitive abilities such as attention and memory represent the most serious issues in old age (2). Whereas, the most common physical conditions are sarcopenia and osteopenia, resulting in reduced functional capacity, compromising daily activities and quality of life (3). The physiological decline with advancing age also affects the aging of the spine which includes the reduction of bone mass and the development of degenerative changes (4). The degeneration of the spine with aging can affect different structures and at various spinal levels including the vertebral body, vertebral endplates, intervertebral discs, facet joints, muscles and ligaments (4, 5). Any alteration to any component, alone or in combination, lead to biomechanical changes which negatively affect range of motion, load carrying capacity, gait and posture (5, 6). Furthermore, this process can lead to several types of lesions and painful symptoms, although the course, speed, and severity of these processes, as well as their consequences, are individual (4).

Considering the prevalence in the population aged over 65, several research groups have shown a growing interest in the topic, by investigating the pathophysiology and biomechanics of the aging spine (4–6). Although this physiological process is dynamic, the extent and speed of these changes are subjective as they can depend on various factors, including the level of physical activity (PA) practice. In fact, the literature is in agreement concerning that regular PA among older women is associated with higher lumbar spine bone mineral density, and that PA programs with higher doses and involving multiple exercises and resistance exercises appear to be more effective (7). For this reason, regular PA appears to protect against spine degeneration, and it is effective to maintain muscle mass and strength, joint mobility, influencing positively body posture (8). Indeed, core muscles have a key role both in the stability and mobility of the spine (4). In contrast, physical inactivity is a risk factor for accelerating the process of musculoskeletal degeneration (9). However, the differences in spine morphology between physically active and sedentary older adults have not yet been extensively investigated.

Radiographic examination is the gold standard for the evaluation of the spine and although in previous decades the evaluation was mainly based on the frontal plane, the importance of the sagittal plane evaluation is now widely recognized (6, 10). Spine assessment includes thorough history, observations, and physical tests which are fundamental to warrant and integrate the radiographic examination (6). However, the use of non-invasive techniques for spine screening can be useful to detect and monitor spine morphology when spine assessment does not justify complementing radiographic examination. In this way, radiation-free examinations are increasingly used to evaluate the spine in order to avoid X-ray exposure (11, 12). Among these alternative methods, the rasterstereography technique, developed by Drerup and Hierholzer (13), represents a valid examination that allows the three-dimensional (3D) reconstruction of the spine by analyzing the back surface (14). In fact, by detecting specific anatomical landmarks of the back surface, the rasterstereography analyzes the 3D back shape and provides the 3D reconstruction of the spine (15). This technique uses the Light Detection and Ranging (LIDAR) technology in which: a sensor sends pulsed laser light (laser emission); a receiver captures the reflected laser light that bounce back from objects (light detection); a processor calculates the time for the pulsed laser light to travel out and back, using the speed of light to measure the distances to the objects; the system creates precise 3D models of objects surface (16). In fact, previous studies assessed the spine morphology through the LIDAR technology (17–20).

Hence, the aim of this study was to analyze the morphological differences of the spine in older women, comparing subjects with different levels of PA. Our hypothesis was that subjects with lower level of PA could present a greater spine imbalance, especially in the sagittal plane.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Study design

In this observational cross-sectional study, participants were divided into different groups, based on the amount of PA practiced, and then their spine morphology was assessed to explore any differences.

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee Palermo 1 of the University Hospital “Policlinico di Palermo” (n. 06/2022) and carried out in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki.

2.2 Participants

Inclusion criteria for participation in the study were as follows: (1) from 65 to 79 years of age; (2) regular participation in any PA or sports for at least 5 years. Exclusion criteria were as follows: (1) presence of any certified spinal deformity; (2) presence of any diagnosed musculoskeletal disease; (3) presence of diagnosed osteoporosis and/or sarcopenia.

A sample of 43 older women were recruited (age: 70.67 ± 3.78 years; weight: 65.22 ± 8.83 kg; height: 1.55 ± 0.08 m).

All participants were informed of the purpose of the study and provided written informed consent to participate.

2.3 Procedure

Participants were invited to the Posturology and Biomechanics Laboratory at the University of Palermo and were first asked to complete the International Physical Activity Questionnaire—Short Form (IPAQ–SF) to measure the levels of PA. Then, their weight and height were measured, and finally their spine was assessed.

2.4 Physical activity level measurement

Participants included in the study were physically active, as among the inclusion criteria there was the participation in any PA or sports for at least 5 years, and, in order to measure the level of PA practiced, expressed as energy expenditure (MET–minutes/week), the IPAQ–SF was administered (21). The IPAQ–SF is a standardized instrument used to assess the levels of PA practice in a population during the “last 7 days” or in the “usual week.” In detail, the questionnaire measures frequencies and durations of sitting activities, walking activities, moderate-intensity PA and vigorous-intensity PA.

Following the scoring protocol of the “Guidelines for Data Processing and Analysis of the International Physical Activity Questionnaire (IPAQ)–Short and Long Forms” and using the Compendium of Physical Activities (and subsequent updates) (22–24), participants were divided into the 3 following groups: low active (LA; <600 MET–minutes/week; n = 16); moderate active (MA; ≥600 MET–minutes/week and <3,000 MET–minutes/week; n = 15); high active (HA; ≥3,000 MET–minutes/week; n = 12).

2.5 Anthropometric measurements

Weight and height were recorded using a Seca electronic scale (maximum weight: 300 kg, resolution: 100 g; Seca; Hamburg, Germany) and a standard stadiometer (maximum height: 220 cm, resolution: 1 mm), respectively.

2.6 Spine assessment

In order to assess the spine morphology a non-invasive, 3D optoelectronic detection system using the Light Detection and Ranging (LIDAR) technology with an infrared Time-of-Flight (ToF) camera (Spine 3D; Sensor Medica, Guidonia Montecelio, Rome, Italy) was used (17–20, 25).

The validity of rasterstereography technique was previously investigated compared with X-ray and this examination has been shown to be valid for screening, monitoring scoliosis progression, follow-ups, as well as for scoliosis diagnosis (14). Furthermore, the rasterstereography technique has been shown to have excellent intra- and inter-day reliability in most parameters with the higher reliability coefficients ranging between 0.972 and 0.982 for the Intraclass Correlation Coefficient (ICC) and between 0.989 and 0.991 for the Cronbach Alpha (Cα) (26). Similarly, the rasterstereography technique has been demonstrated to have excellent intra- and inter-observer reliability of all parameters showing the maximum ICC = 0.988 and the minimum ICC = 0.918 (27). A previous study demonstrated a variability, expressed as Standard Error of Measurement (SEM), less than 1.5° and 1.5 mm for the angular and linear parameters, respectively (28).

Each participant was asked to stay 1 meter from the instrument, in upright position barefoot and with feet placed side-by-side, head in neutral position, and with the back bare-chested facing the camera of the instrument.

The anatomical landmarks were as follows: prominent vertebra (VP), right and left shoulder (SR and SL), right and left lumbar dimple (DR and DL) and the midpoint between them (DM). Based on these landmarks, the software computes specific parameters in the frontal, sagittal, and horizontal planes. The main parameters were as follows. Frontal plane—(a) Spine Length: the length of the segment from VP to DM; (b) Spine Frontal Imbalance: the length between the vertical line passing through DM and the vertical line passing through VP; (c) Spine imbalance: the angle between the line passing through VP and DM and the vertical line passing through DM; (d) Shoulder obliquity: the distance between the horizontal axis passing through SL and the horizontal axis passing through SR; (e) Shoulder tilt: the angle between the line passing through SL and SR and the horizontal axis; (f) Maximum left vertebral deviation: convexity to the left; (g) Maximum right vertebral deviation: convexity to the right; (h) Maximum left rotation surface: the angle between the line passing through the centre of the vertebral body and the apex of the spinous process and the line perpendicular to the frontal plane; (i) Maximum right rotation surface: the angle between the line passing through the centre of the vertebral body and the apex of the spinous process and the line perpendicular to the frontal plane; (j) Pelvis obliquity: the distance between the horizontal axis passing through DL and the horizontal axis passing through DR; (k) Pelvis tilt: the angle between the line passing through DL and DR and the horizontal axis; (l) Cobb curve thoraco-lumbar: the Cobb’s angle between T9 and L2; (m) Cobb curve lumbar: the Cobb’s angle between L2 and L4. Sagittal plane—(a) Spine Length: the length of the segment from VP to DM; (b) Spine Sagittal Imbalance: the length between the vertical line passing through VP and the vertical line passing through DM; (c) Spine Inclination: the angle between the line passing through VP and DM and the vertical line passing through DM; (d) Cervical Lordosis: the distance between the cervical apex and the tangent to the kyphotic apex; (e) Lumbar Lordosis: the distance between the lumbar apex and the tangent to the kyphotic apex; (f) Kyphotic Angle: the upper angle formed by the tangents to the surface at the cervico-thoracic inversion (ICT) and the thoraco-lumbar inversion (ITL) points; (g) Lordotic Angle: the upper angle formed by the tangents to the surface at ITL and the lumbosacral inversion (ILS) points. Horizontal plane—(a) Shoulder torsion: the angle of rotation of the shoulder girdle (SL-SR); (b) Pelvis torsion: the angle of rotation of the pelvis girdle (DL-DR).

For each participant, the spine assessment was conducted by the same researcher, who was an expert in the use of the instrument, during the same time slot (i.e., between 9:00 and 12:00) in order to minimize time-of-day effect.

2.7 Statistical analysis

Data distributions were tested using the Shapiro–Wilk’s test. Data are presented as mean ± standard deviation. Differences in spine parameters among the three groups, in the frontal and sagittal plane, were evaluated using the one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA). The Tukey’s post-hoc multiple comparisons test was carried out in presence of significant difference. Moreover, in case of significant difference, the eta-squared (η2) was carried out to measure the effect size. Mean differences in spine parameters among the three groups were calculated.

The level of significance for all statistical analyses was set at p < 0.05.

All statistical analyses were performed using Jamovi software; The jamovi project (2022). jamovi. (Version 2.3) [Computer Software]. Retrieved from: https://www.jamovi.org.

All figures were created using GraphPad Prism 8 (GraphPad Software Inc., San Diego, CA, USA).

A post hoc analysis was computed to detect the achieved sample size power, using an ANOVA design (f = 0.40, α = 0.05), using G*Power software (v. 3.1.9.2; Heinrich Heine University, Düsseldorf, Germany).

3 Results

The Shapiro–Wilk’s test showed that data were normally distributed.

Participants’ characteristics were as follows: LA group: n = 16; age: 71.38 ± 4.53 years; weight: 63.90 ± 8.98 kg; height: 1.55 ± 0.09 m; MA group: n = 15; age: 70.67 ± 3.74 years; weight: 66.45 ± 9.26 kg; height: 1.55 ± 0.09 m; HA group: n = 12; age: 69.75 ± 2.67 years; weight: 65.45 ± 8.61 kg; height: 1.56 ± 0.05 m.

The post hoc power analysis showed that with a total sample size of 43 participants a power of 0.61 was achieved.

Tables 1, 2 shows descriptive data of the spine parameters for each group in the frontal and sagittal plane, respectively.

Table 1

| Parameter | Group | Mean ± SD |

|---|---|---|

| Spine length (mm) | LA | 419.69 ± 34.71 |

| MA | 413.67 ± 29.34 | |

| HA | 407.08 ± 20.48 | |

| Spine frontal imbalance (mm) | LA | −4.63 ± 9.91 |

| MA | −0.33 ± 9.20 | |

| HA | −3.75 ± 10.22 | |

| Spine imbalance (°) | LA | 0.66 ± 1.39 |

| MA | 0.04 ± 1.26 | |

| HA | 0.52 ± 1.47 | |

| Shoulder obliquity (mm) | LA | −1.25 ± 12.87 |

| MA | 2.93 ± 11.63 | |

| HA | 3.92 ± 11.52 | |

| Shoulder tilt (°) | LA | −0.20 ± 2.45 |

| MA | 0.53 ± 2.08 | |

| HA | 0.72 ± 2.08 | |

| Maximum left vertebral deviation (mm) | LA | −4 ± 4.55 |

| MA | −5.67 ± 4.92 | |

| HA | −6.17 ± 5.15 | |

| Maximum right vertebral deviation (mm) | LA | 1.69 ± 2.21 |

| MA | 1.93 ± 2.58 | |

| HA | 3.42 ± 3.68 | |

| Maximum left rotation surface (°) | LA | −11.39 ± 7.44 |

| MA | −12.38 ± 7.02 | |

| HA | −13.23 ± 8.30 | |

| Maximum right rotation surface (°) | LA | 2.89 ± 4.09 |

| MA | 0.95 ± 1.90 | |

| HA | 3.28 ± 4.08 | |

| Pelvis obliquity (mm) | LA | 0.06 ± 4.74 |

| MA | 2.40 ± 4.66 | |

| HA | 2.50 ± 5.25 | |

| Pelvis tilt (°) | LA | −0.04 ± 2.60 |

| MA | 1.33 ± 2.68 | |

| HA | 1.47 ± 3.03 |

Descriptive data of the spine parameters in the frontal plane.

LA, low active; MA, moderate active; HA, high active; mm, millimeters; °, degrees.

Table 2

| Parameter | Group | Mean ± SD |

|---|---|---|

| Spine length (mm) | LA | 419.69 ± 34.71 |

| MA | 413.67 ± 29.34 | |

| HA | 407.08 ± 20.48 | |

| Spine sagittal imbalance (mm) | LA | 53.75 ± 17.49 |

| MA | 36.93 ± 17.29 | |

| HA | 32.42 ± 18.31 | |

| Spine inclination (°) | LA | 7.67 ± 2.76 |

| MA | 5.05 ± 2.28 | |

| HA | 4.50 ± 2.80 | |

| Cervical lordosis (mm) | LA | 42.63 ± 16.46 |

| MA | 39.93 ± 8.83 | |

| HA | 32.67 ± 13.58 | |

| Lumbar lordosis (mm) | LA | 59.38 ± 17.50 |

| MA | 57.00 ± 12.00 | |

| HA | 51.42 ± 13.89 | |

| Kyphotic angle (°) | LA | 57.04 ± 13.77 |

| MA | 54.62 ± 11.83 | |

| HA | 51.85 ± 14.29 | |

| Lordotic angle (°) | LA | 62.22 ± 34.05 |

| MA | 46.11 ± 15.79 | |

| HA | 48.34 ± 12.15 |

Descriptive data of the spine parameters in the sagittal plane.

LA, low active; MA, moderate active; HA, high active; mm, millimeters; °, degrees.

The one-way ANOVA detected no significant differences in spine parameters in the frontal plane among the 3 groups, as shown in Table 3.

Table 3

| Parameter | F | df1 | df2 | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Spine frontal imbalance (mm) | 0.82 | 2 | 40 | 0.45 |

| Spine imbalance (°) | 0.86 | 2 | 40 | 0.43 |

| Shoulder obliquity (mm) | 0.76 | 2 | 40 | 0.48 |

| Shoulder tilt (°) | 0.71 | 2 | 40 | 0.50 |

| Maximum left vertebral deviation (mm) | 0.80 | 2 | 40 | 0.46 |

| Maximum right vertebral deviation (mm) | 1.45 | 2 | 40 | 0.25 |

| Maximum left rotation Surface (°) | 0.21 | 2 | 40 | 0.81 |

| Maximum right rotation surface (°) | 1.84 | 2 | 40 | 0.17 |

| Pelvis obliquity (mm) | 1.21 | 2 | 40 | 0.31 |

| Pelvis tilt (°) | 1.36 | 2 | 40 | 0.27 |

One way ANOVA of the spine parameters in the frontal plane among the three groups.

df, degrees of freedom; mm, millimeters; °, degrees.

In the sagittal plane, we found a significant difference on the spine sagittal imbalance parameter among the 3 groups (F(2, 40)=6.17; p = 0.005) (Table 4), with the highest spine sagittal imbalance in the LA group (Tables 2, 5). The effect size was η2 = 0.229.

Table 4

| Parameter | F | df1 | df2 | p | η2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Spine length (mm) | 0.63 | 2 | 40 | 0.54 | – |

| Spine sagittal imbalance (mm) | 6.17 | 2 | 40 | 0.005 | 0.229 |

| Spine inclination (°) | 5.93 | 2 | 40 | 0.006 | 0.236 |

| Cervical lordosis (mm) | 1.96 | 2 | 40 | 0.15 | – |

| Lumbar lordosis (mm) | 1.02 | 2 | 40 | 0.37 | – |

| Kyphotic angle (°) | 0.52 | 2 | 40 | 0.60 | – |

| Lordotic angle (°) | 2.07 | 2 | 40 | 0.14 | – |

One way ANOVA of the spine parameters in the sagittal plane among the 3 groups.

df, degrees of freedom; mm, millimeters; °, degrees.

Table 5

| Multiple comparisons | Mean difference | p |

|---|---|---|

| LA vs. MA | 16.82 | 0.030 |

| LA vs. HA | 21.33 | 0.008 |

| MA vs. HA | 4.52 | 0.787 |

Tukey’s post-hoc multiple comparisons test for the spine sagittal imbalance (mm).

LA, low active; MA, moderate active; HA, high active.

The Tukey’s post-hoc multiple comparisons test showed a significant difference between LA and MA group (p = 0.030), and between LA and HA group (p = 0.008), as reported in Table 5 and Figure 1.

Figure 1

Spine sagittal imbalance differences among the three groups. LA, low active; MA, moderate active; HA, high active; mm, millimeters.

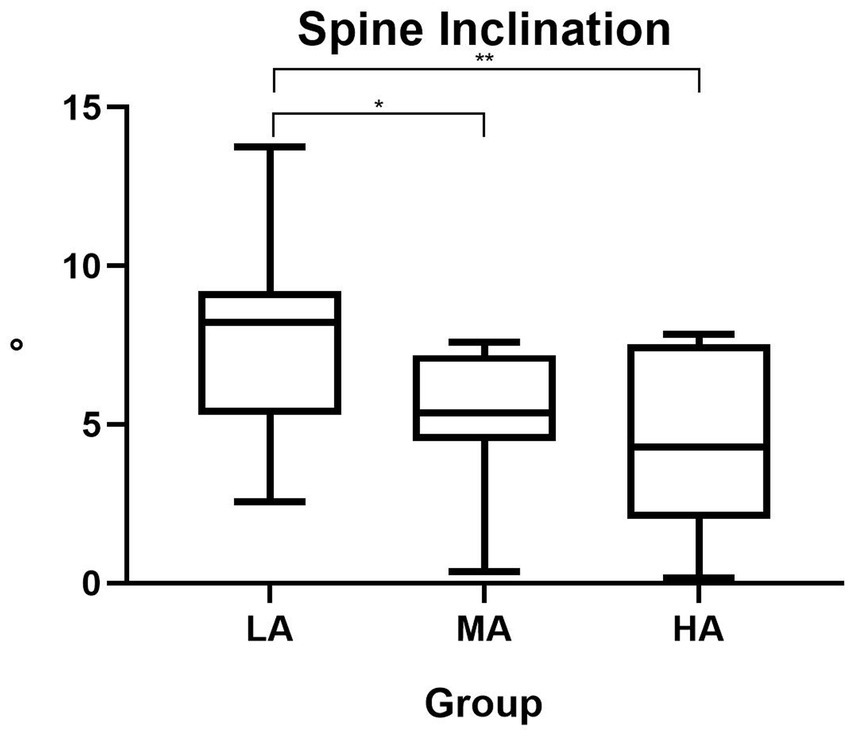

Furthermore, in the sagittal plane, we detected a significant difference in the spine inclination parameter among the 3 groups (F(2, 40)=5.93; p = 0.006) (Table 4), with the highest spine inclination in the LA group (Tables 2, 6). The effect size was η2 = 0.236.

Table 6

| Multiple comparisons | Mean difference | p |

|---|---|---|

| LA vs. MA | 2.62 | 0.021 |

| LA vs. HA | 3.16 | 0.008 |

| MA vs. HA | 0.54 | 0.854 |

Tukey’s post-hoc multiple comparisons test for the spine inclination (°).

LA, low active; MA, moderate active; HA, high active.

The Tukey’s post-hoc multiple comparisons test showed a significant difference between LA and MA group (p = 0.021), and between LA and HA group (p = 0.008), as reported in Table 6 and Figure 2.

Figure 2

Spine inclination differences among the three groups. LA, low active; MA, moderate active; HA, high active; °, degrees.

4 Discussion

The aim of this study was to analyze any spine differences in older women comparing subjects with different levels of PA. Our results showed that older women who engaged in lower levels of PA exhibited some altered spinal sagittal parameters compared to peers with moderate and high levels of PA. Specifically, we found an increasing sagittal imbalance of the spine as the level of PA decreased, that is, from high active to low active. Similarly, we detected the same trend for the sagittal inclination of the spine with the highest angle in the low active group. Moreover, the differences found are clinically meaningful. In fact, the significant mean differences we detected exceed the range of SEM of the rasterstereography technique (28). These alterations reflect a forward displacement of the trunk and consequent less efficient body posture (29, 30).

Physiological and biomechanical changes during aging such as a lumbar lordosis reduction and a thoracic kyphosis increase, leading to pelvic retroversion, have been documented (31). The existing literature has documented the importance of spine assessment in the sagittal plane, as spinal sagittal malalignment may reflect a loss of the physiological curves of the spine, with possible forward tilt of the trunk, and possible consequent posterior pelvic rotation (6, 10, 32). Indeed, the assessment of the spine in the sagittal plane can be useful in order to have an image of the spine shape, and to monitor differences in spine alignment and compensation (6). As a matter of fact, spinal balance can depend on muscle response of the trunk to maintain stable upright posture (33). In fact, a research group demonstrated that a sagittal vertical axis higher than 40 mm indicates a poor sagittal balance and higher values of this parameter indicate poorer sagittal alignment (34, 35). A sagittal vertical axis higher than 40 mm significantly increases the number of falls (36). In the sample we recruited, the LA group showed a spine sagittal imbalance of 53.75 ± 17.49 mm and this can represent a significant clinical risk (37). As a matter of fact, spinal sagittal alignment is a key factor for preventing and managing spinal disorders, especially during aging (29). Our results also showed that the LA group had a spine inclination of 7.67 ± 2.76 ° resulting in significant health risks that negatively impact the quality of life (30). In fact, an optimal spinal sagittal balance is fundamental for maintaining a neutral standing posture during daily activities (29).

These results could find practical application in evaluating spine differences based on age, gender, or PA practice. In fact, previous research showed age- and gender-related differences in spinal sagittal morphology. For example, a study by Yukawa et al. (38) showed changes in sagittal alignment according to gender and age in a large sample of asymptomatic individuals. In particular, in line with our results, the authors found, among their findings, an increase in the sagittal vertical axis as physiological change with advancing age (38). In the same way, Imagama et al. (39) reported that physical functions are negative correlated with both age and spinal inclination angle in middle-aged and elderly subjects and, among other, these could affect the quality of life. Moreover, the participants who were engaged in physical exercise exhibited higher levels of physical characteristics including greater thoracic spinal range of motion (ROM) and back muscle strength as well as good spinal balance underlining the importance of physical exercise on the morpho-functional characteristics of the spine (39). Indeed, the practice of leisure time PA, regular PA, structured exercise, and sports, can protect against spine degeneration, can prevent from sarcopenia and osteopenia in postmenopausal women (40–42). It is widely known that regular PA appears to protect against spinal deterioration by contributing to the maintenance of muscle mass and strength, joint flexibility, and posture (43, 44). In fact, the benefits of PA on the musculoskeletal health of the back are well documented in the literature (45, 46). It seems that the compressive strength of the spine tends to increase with the level of PA practiced and that PA strengthens both the vertebrae and the discs (47). An interesting study by Borg-Stein et al. (48) explored the aging spine in sports showing that the benefits of regular sports engagement overcome the potential risks of spine degeneration in middle-aged athletes. A seminal study in this field showed that in a sample of women aged 55 to 75 who had started physical exercise regularly at age 50, bone mineral density was significantly higher than that of women of an age-matched sample who had not engaged in physical exercise (48, 49).

Most of the participants recruited for this study had been participating in walking groups, and others in postural gymnastics or Pilates. Indeed, different types of exercise are effective for spine health as aerobic exercises, e.g., walking or swimming, thanks to the fact that these activities offer low impact on the spine (50, 51), in contrast to activities that can have high impact on the spine such as running (52). For example, a recent systematic review demonstrated that, due to compression pushing water content out of the disc, running has a negative impact on intervertebral discs (52). Furthermore, compression of the intervertebral discs can increase as the intensity of running increases (53). While, the types of load useful for intervertebral discs are dynamic, axial, at slow to moderate movement speeds, such as in walking (54). As for swimming, it has been demonstrated that can improve bone mineral density in postmenopausal women, especially in long-term, and this can prevent spinal deformities (51, 55). As a matter of fact, low bone mineral density is a predictor of spinal deformities (55–57).

Among the types of exercise recommended, the effectiveness of strength exercises for preventing and managing spine malalignment or spine disorders, e.g., Pilates or Yoga, is well demonstrated by several research groups (44, 58–61). For example, Pilates resulted an effective method for reducing pain and improving flexibility, as well as static and dynamic endurance in subjects with lumbar disc herniation (59). Similarly, the stretch and strength-based Yoga exercise showed a significant pain reduction in subjects with lumbar disc herniation (60). Based on previous studies, the improvement in back muscle strength as well as in core muscle strength through exercise can prevent spinal degeneration and prevent spinal sagittal malalignment (36, 62, 63). As reported in a recent umbrella systematic review, combined resistance exercises are effective in preserving bone mineral density of the lumbar spine, and the concurrent training showed significant improvements (64). Indeed, the literature agrees that combining various exercise programs has a positive effect on lumbar spine bone mineral density (65).

In contrast, it is well recognized that static sitting posture increases the compression of the lumbar intervertebral discs (66). These studies demonstrate that the health and the morphology of the spine can depend on the type and level of PA practice, supporting our research hypothesis.

4.1 Strengths and limitations

The originality of this study was to consider the level of PA practice as an influencing factor for spinal sagittal alignment, underlying that the amount of PA may play a key role in preventing spinal sagittal imbalance.

Among the limitations it must be mentioned that it is a cross-sectional study limiting causal inference. Furthermore, it must be mentioned that the sample size does not allow to generalize the results. In fact, the post hoc analysis showed that the sample size achieved a power of 0.61.

4.2 Practical implications

This study emphasizes the effectiveness of PA on the aging of the spine. Moreover, it should be underlined that the use of non-invasive techniques to screen and monitor spine morphology can be useful to avoid radiographic radiation when radiographic examination is not justified, and to adopt the rasterstereography technique in routine clinical use.

5 Conclusion

Our findings that low active women showed higher values of spine sagittal imbalance and spine inclination compared to women engaged in moderate or high levels suggest that PA may contribute to maintain spinal sagittal alignment and preserve spinal sagittal balance. This could probably be explained by the fact that PA leads to the strengthening of the back muscles, including stabilizing muscles of the spine, which could slow down the physiological progression of sagittal imbalance that occurs with advancing age. Although PA can prevent the aging of the spine, further studies should clarify to what extent PA can affect spinal alignment.

Statements

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by the Ethics Committee Palermo 1 of the University Hospital “Policlinico di Palermo” (n. 06/2022) and carried out in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

JB: Investigation, Software, Data curation, Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft. VG: Formal analysis, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. GM: Writing – review & editing, Conceptualization, Supervision. LD: Validation, Writing – review & editing. DK-N: Writing – review & editing, Visualization. MB: Validation, Writing – review & editing. RN: Visualization, Writing – review & editing. IL: Writing – review & editing, Software. AP: Visualization, Writing – review & editing. AB: Writing – review & editing, Methodology. GB: Validation, Conceptualization, Writing – review & editing. AI: Conceptualization, Writing – review & editing, Project administration. EP: Project administration, Writing – review & editing, Conceptualization.

Funding

The author(s) declared that financial support was not received for this work and/or its publication.

Conflict of interest

The author(s) declared that this work was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

The author(s) MB declared that they were an editorial board member of Frontiers, at the time of submission. This had no impact on the peer review process and the final decision.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declared that Generative AI was not used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1.

Dziechciaz M Filip R . Biological psychological and social determinants of old age: bio-psycho-social aspects of human aging. Ann Agric Environ Med. (2014) 21:835–8. doi: 10.5604/12321966.1129943,

2.

Cheng A Zhao Z Liu H Yang J Luo J . The physiological mechanism and effect of resistance exercise on cognitive function in the elderly people. Front Public Health. (2022) 10:1013734. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2022.1013734,

3.

Cruz-Jimenez M . Normal changes in gait and mobility problems in the elderly. Phys Med Rehabil Clin N Am. (2017) 28:713–25. doi: 10.1016/j.pmr.2017.06.005,

4.

Papadakis M Sapkas G Papadopoulos EC Katonis P . Pathophysiology and biomechanics of the aging spine. Open Orthop J. (2011) 5:335–42. doi: 10.2174/1874325001105010335,

5.

Ferguson SJ Steffen T . Biomechanics of the aging spine. Eur Spine J. (2003) 12:S97–S103. doi: 10.1007/s00586-003-0621-0,

6.

Diebo BG Shah NV Boachie-Adjei O Zhu F Rothenfluh DA Paulino CB et al . Adult spinal deformity. Lancet. (2019) 394:160–72. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(19)31125-0

7.

Pinheiro MB Oliveira J Bauman A Fairhall N Kwok W Sherrington C . Evidence on physical activity and osteoporosis prevention for people aged 65+ years: a systematic review to inform the WHO guidelines on physical activity and sedentary behaviour. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. (2020) 17:150. doi: 10.1186/s12966-020-01040-4,

8.

Patti A Thornton JS Giustino V Drid P Paoli A Schulz JM et al . Effectiveness of Pilates exercise on low back pain: a systematic review with meta-analysis. Disabil Rehabil. (2024) 46:3535–48. doi: 10.1080/09638288.2023.2251404,

9.

Izquierdo M de Souto Barreto P Arai H Bischoff-Ferrari HA Cadore EL Cesari M et al . Global consensus on optimal exercise recommendations for enhancing healthy longevity in older adults (ICFSR). J Nutr Health Aging. (2025) 29:100401. doi: 10.1016/j.jnha.2024.100401,

10.

Diebo BG Varghese JJ Lafage R Schwab FJ Lafage V . Sagittal alignment of the spine: what do you need to know?Clin Neurol Neurosurg. (2015) 139:295–301. doi: 10.1016/j.clineuro.2015.10.024,

11.

Hierholzer E Hackenberg L . Three-dimensional shape analysis of the scoliotic spine using MR tomography and rasterstereography. Stud Health Technol Inform. (2002) 91:184–9. doi: 10.3233/978-1-60750-935-6-184

12.

Hackenberg L Hierholzer E Liljenqvist U . Accuracy of rasterstereography versus radiography in idiopathic scoliosis after anterior correction and fusion. Stud Health Technol Inform. (2002) 91:241–5. doi: 10.3233/978-1-60750-935-6-241

13.

Drerup B Hierholzer E . Automatic localization of anatomical landmarks on the back surface and construction of a body-fixed coordinate system. J Biomech. (1987) 20:961–70. doi: 10.1016/0021-9290(87)90325-3,

14.

Mohokum M Schulein S Skwara A . The validity of rasterstereography: a systematic review. Orthop Rev (Pavia). (2015) 7:5899. doi: 10.4081/or.2015.5899

15.

Mohokum M Mendoza S Udo W Sitter H Paletta JR Skwara A . Reproducibility of rasterstereography for kyphotic and lordotic angles, trunk length, and trunk inclination: a reliability study. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). (2010) 35:1353–8. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e3181cbc157

16.

Liljenqvist U Halm H Hierholzer E Drerup B Weiland M . 3-dimensional surface measurement of spinal deformities with video rasterstereography. Z Orthop Ihre Grenzgeb. (1998) 136:57–64. doi: 10.1055/s-2008-1044652,

17.

Patti A Giustino V Messina G Figlioli F Cataldi S Poli L et al . Effects of cycling on spine: a case-control study using a 3D scanning method. Sports. (2023) 11:227. doi: 10.3390/sports11110227,

18.

Roggio F Petrigna L Trovato B Zanghi M Sortino M Vitale E et al . Thermography and rasterstereography as a combined infrared method to assess the posture of healthy individuals. Sci Rep. (2023) 13:4263. doi: 10.1038/s41598-023-31491-1,

19.

Marin L Lovecchio N Pedrotti L Manzoni F Febbi M Albanese I et al . Acute effects of self-correction on spine deviation and balance in adolescent girls with idiopathic scoliosis. Sensors (Basel). (2022) 22:1883. doi: 10.3390/s22051883,

20.

Scoppa F Graffitti A Pirino A Piermaria J Tamburella F Tramontano M . Three-dimensional posture analysis-based modifications after manual therapy: a preliminary study. J Clin Med. (2025) 14:634. doi: 10.3390/jcm14020634,

21.

Lee PH Macfarlane DJ Lam TH Stewart SM . Validity of the international physical activity questionnaire short form (IPAQ-SF): a systematic review. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. (2011) 8:115. doi: 10.1186/1479-5868-8-115,

22.

Ainsworth BE Haskell WL Leon AS Jacobs DR Jr Montoye HJ Sallis JF et al . Compendium of physical activities: classification of energy costs of human physical activities. Med Sci Sports Exerc. (1993) 25:71–80. doi: 10.1249/00005768-199301000-00011,

23.

Ainsworth BE Haskell WL Whitt MC Irwin ML Swartz AM Strath SJ et al . Compendium of physical activities: an update of activity codes and MET intensities. Med Sci Sports Exerc. (2000) 32:10993420:S498–516. doi: 10.1097/00005768-200009001-00009

24.

Ainsworth BE Haskell WL Herrmann SD Meckes N Bassett DR Jr Tudor-Locke C et al . 2011 compendium of physical activities: a second update of codes and MET values. Med Sci Sports Exerc. (2011) 43:1575–81. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0b013e31821ece12,

25.

Molinaro L Russo L Cubelli F Taborri J Rossi S , Reliability analysis of an innovative technology for the assessment of spinal abnormalities. 2022 IEEE international symposium on medical measurements and applications (MeMeA); 2022: IEEE.

26.

Guidetti L Bonavolonta V Tito A Reis VM Gallotta MC Baldari C . Intra- and interday reliability of spine rasterstereography. Biomed Res Int. (2013) 2013:745480. doi: 10.1155/2013/745480,

27.

Schulein S Mendoza S Malzkorn R Harms J Skwara A . Rasterstereographic evaluation of interobserver and intraobserver reliability in postsurgical adolescent idiopathic scoliosis patients. J Spinal Disord Tech. (2013) 26:E143–9. doi: 10.1097/BSD.0b013e318281608c,

28.

Schroeder J Reer R Braumann KM . Video raster stereography back shape reconstruction: a reliability study for sagittal, frontal, and transversal plane parameters. Eur Spine J. (2015) 24:262–9. doi: 10.1007/s00586-014-3664-5,

29.

Wang W Wang Z Wang D Liu C Kong C Zhu W et al . Age-related changes and spinal sagittal alignment in asymptomatic community dwelling adults over 50. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). (2025) 50:E431–7. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0000000000005248,

30.

Yasuda T Hasegawa T Yamato Y Kobayashi S Togawa D Arima H et al . Sagittal alignment in Japanese elderly people - how much can we tolerate as normal sagittal vertical axis?Scoliosis. (2015) 10:O34. doi: 10.1186/1748-7161-10-S1-O34

31.

Prost S Blondel B Bauduin E Pesenti S Ilharreborde B Laouissat F et al . Do age-related variations of sagittal alignment rely on SpinoPelvic organization? An observational study of 1540 subjects. Global Spine J. (2023) 13:2144–54. doi: 10.1177/21925682221074660,

32.

Schwab FJ Blondel B Bess S Hostin R Shaffrey CI Smith JS et al . Radiographical spinopelvic parameters and disability in the setting of adult spinal deformity: a prospective multicenter analysis. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). (2013) 38:E803–12. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e318292b7b9

33.

Abelin-Genevois K . Sagittal balance of the spine. Orthop Traumatol Surg Res. (2021) 107:102769. doi: 10.1016/j.otsr.2020.102769,

34.

Schwab F Farcy JP Bridwell K Berven S Glassman S Harrast J et al . A clinical impact classification of scoliosis in the adult. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). (2006) 31:2109–14. doi: 10.1097/01.brs.0000231725.38943.ab,

35.

Schwab F Lafage V Farcy JP Bridwell K Glassman S Ondra S et al . Surgical rates and operative outcome analysis in thoracolumbar and lumbar major adult scoliosis: application of the new adult deformity classification. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). (2007) 32:2723–30. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e31815a58f2,

36.

Imagama S Ito Z Wakao N Seki T Hirano K Muramoto A et al . Influence of spinal sagittal alignment, body balance, muscle strength, and physical ability on falling of middle-aged and elderly males. Eur Spine J. (2013) 22:1346–53. doi: 10.1007/s00586-013-2721-9,

37.

Matsumoto K Shah A Kelkar A Mumtaz M Kumaran Y Goel VK . Sagittal imbalance may Lead to higher risks of vertebral compression fractures and disc degeneration-a finite element analysis. World Neurosurg. (2022) 167:e962–71. doi: 10.1016/j.wneu.2022.08.119,

38.

Yukawa Y Kato F Suda K Yamagata M Ueta T Yoshida M . Normative data for parameters of sagittal spinal alignment in healthy subjects: an analysis of gender specific differences and changes with aging in 626 asymptomatic individuals. Eur Spine J. (2018) 27:426–32. doi: 10.1007/s00586-016-4807-7,

39.

Imagama S Hasegawa Y Matsuyama Y Sakai Y Ito Z Hamajima N et al . Influence of sagittal balance and physical ability associated with exercise on quality of life in middle-aged and elderly people. Arch Osteoporos. (2011) 6:13–20. doi: 10.1007/s11657-011-0052-1,

40.

Billot M Calvani R Urtamo A Sanchez-Sanchez JL Ciccolari-Micaldi C Chang M et al . Preserving mobility in older adults with physical frailty and sarcopenia: opportunities, challenges, and recommendations for physical activity interventions. Clin Interv Aging. (2020) 15:32982201:1675–90. doi: 10.2147/CIA.S253535

41.

Watson SL Weeks BK Weis LJ Harding AT Horan SA Beck BR . High-intensity resistance and impact training improves bone mineral density and physical function in postmenopausal women with osteopenia and osteoporosis: the LIFTMOR randomized controlled trial. J Bone Miner Res. (2018) 33:211–20. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.3284,

42.

Hagberg JM Zmuda JM McCole SD Rodgers KS Ferrell RE Wilund KR et al . Moderate physical activity is associated with higher bone mineral density in postmenopausal women. J Am Geriatr Soc. (2001) 49:1411–7. doi: 10.1046/j.1532-5415.2001.4911231.x,

43.

Warneke K Lohmann LH Wilke J . Effects of stretching or strengthening exercise on spinal and Lumbopelvic posture: a systematic review with Meta-analysis. Sports Med Open. (2024) 10:65. doi: 10.1186/s40798-024-00733-5,

44.

Li F Omar Dev RD Soh KG Wang C Yuan Y . Effects of Pilates exercises on spine deformities and posture: a systematic review. BMC Sports Sci Med Rehabil. (2024) 16:55. doi: 10.1186/s13102-024-00843-3,

45.

Heneghan NR Baker G Thomas K Falla D Rushton A . What is the effect of prolonged sitting and physical activity on thoracic spine mobility? An observational study of young adults in a UK university setting. BMJ Open. (2018) 8:e019371. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-019371,

46.

Alonso-Sal A Alonso-Perez JL Sosa-Reina MD Garcia-Noblejas-Fernandez JA Balani-Balani VG Rossettini G et al . Effectiveness of physical activity in the management of nonspecific low back pain: a systematic review. Medicina (Kaunas). (2024) 60:2065. doi: 10.3390/medicina60122065,

47.

Porter RW Adams MA Hutton WC . Physical activity and the strength of the lumbar spine. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). (1989) 14:201–3. doi: 10.1097/00007632-198902000-00009,

48.

Borg-Stein J Elson L Brand E . The aging spine in sports. Clin Sports Med. (2012) 31:473–86. doi: 10.1016/j.csm.2012.03.002,

49.

Jacobson PC Beaver W Grubb SA Taft TN Talmage RV . Bone density in women: college athletes and older athletic women. J Orthop Res. (1984) 2:328–32. doi: 10.1002/jor.1100020404,

50.

Suh JH Kim H Jung GP Ko JY Ryu JS . The effect of lumbar stabilization and walking exercises on chronic low back pain: a randomized controlled trial. Medicine (Baltimore). (2019) 98:e16173. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000016173,

51.

Su Y Chen Z Xie W . Swimming as treatment for osteoporosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Biomed Res Int. (2020) 2020:6210201. doi: 10.1155/2020/6210201,

52.

Shu D Dai S Wang J Meng F Zhang C Zhao Z . Impact of running exercise on intervertebral disc: a systematic review. Sports Health. (2024) 16:958–70. doi: 10.1177/19417381231221125,

53.

Kingsley MI D'Silva LA Jennings C Humphries B Dalbo VJ Scanlan AT . Moderate-intensity running causes intervertebral disc compression in young adults. Med Sci Sports Exerc. (2012) 44:2199–204. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0b013e318260dbc1

54.

Belavý DL Albracht K Bruggemann G-P Vergroesen P-PA van Dieën JH . Can exercise positively influence the intervertebral disc?Sports Med. (2016) 46:473–85. doi: 10.1007/s40279-015-0444-2

55.

Khalid SI Nunna RS Smith JS Shanker RM Cherney AA Thomson KB et al . The role of bone mineral density in adult spinal deformity patients undergoing corrective surgery: a matched analysis. Acta Neurochir. (2022) 164:2327–35. doi: 10.1007/s00701-022-05317-4,

56.

Chen JW McCandless MG Bhandarkar AR Flanigan PM Lakomkin N Mikula AL et al . The association between bone mineral density and proximal junctional kyphosis in adult spinal deformity: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Neurosurg Spine. (2023) 39:82–91. doi: 10.3171/2023.2.SPINE221101,

57.

Zhang TT Ding JZ Kong C Zhu WG Wang SK Lu SB . Paraspinal muscle degeneration and lower bone mineral density as predictors of proximal junctional kyphosis in elderly patients with degenerative spinal diseases: a propensity score matched case-control analysis. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. (2022) 23:1010. doi: 10.1186/s12891-022-05960-z,

58.

Tsekoura M Katsoulaki M Kastrinis A Nomikou E Fousekis K Tsepis E et al . The effects of exercise in older adults with Hyperkyphotic posture In: Adv Exp med biol, vol. 1425 (2023). 501–6. doi: 10.1007/978-3-031-31986-0_49

59.

Taspinar G Angin E Oksuz S . The effects of Pilates on pain, functionality, quality of life, flexibility and endurance in lumbar disc herniation. J Comp Eff Res. (2023) 12:e220144. doi: 10.2217/cer-2022-0144

60.

Yildirim P Gultekin A . The effect of a stretch and strength-based yoga exercise program on patients with neuropathic pain due to lumbar disc herniation. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). (2022) 47:711–9. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0000000000004316

61.

Rathore V Singh S Katiyar VK . Exploring the therapeutic effects of yoga on spine and shoulder mobility: a systematic review. J Bodyw Mov Ther. (2024) 40:586–96. doi: 10.1016/j.jbmt.2024.04.029,

62.

Huang D Wang Z Dekhne M Durbas A Subramanian T Dykhouse G et al . Balance or strength? Reconsidering muscle metrics in sagittal malalignment in adult sagittal deformity patients. J Clin Med. (2025) 14:3293. doi: 10.3390/jcm14103293,

63.

Hamzeh Shalamzari M Shamsoddini A Ghanjal A Shirvani H . Comparison of the effects of core stability and whole-body electromyostimulation exercises on kyphosis angle and core muscle endurance of inactive people with hyper kyphosis: a quasi-experimental pre-post study. J Bodyw Mov Ther. (2024) 38:474–82. doi: 10.1016/j.jbmt.2023.11.007,

64.

Fausto DY Martins JBB Machado AC Saraiva PS Pelegrini A Guimaraes ACA . What is the evidence for the effect of physical exercise on bone health in menopausal women?Umbrella Syst Rev Climact. (2023) 26:550–9. doi: 10.1080/13697137.2023.2249819,

65.

Hsu HH Chiu CY Chen WC Yang YR Wang RY . Effects of exercise on bone density and physical performance in postmenopausal women: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PM R. (2024) 16:1358–83. doi: 10.1002/pmrj.13206,

66.

Zanola RL Donin CB Bertolini GRF Buzanello Azevedo MR . Biomechanical repercussion of sitting posture on lumbar intervertebral discs: a systematic review. J Bodyw Mov Ther. (2024) 38:384–90. doi: 10.1016/j.jbmt.2024.01.018,

Summary

Keywords

aging, back, elderly, exercise, physical activity, spinal column, spine, sport

Citation

Brusa J, Giustino V, Messina G, Dominguez LJ, Kostrzewa-Nowak D, Barbagallo M, Nowak R, Leale I, Patti A, Bianco A, Battaglia G, Iovane A and Padua E (2026) Differences in the aging of the spine according to physical activity levels in older women. Front. Med. 12:1730935. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2025.1730935

Received

23 October 2025

Revised

22 December 2025

Accepted

29 December 2025

Published

13 January 2026

Volume

12 - 2025

Edited by

Di Wu, Harvard Medical School, United States

Reviewed by

Hiroki Takayama, Hanna Central College of Rehabilitation, Japan

Lilin Lan, Western Michigan University, United States

Updates

Copyright

© 2026 Brusa, Giustino, Messina, Dominguez, Kostrzewa-Nowak, Barbagallo, Nowak, Leale, Patti, Bianco, Battaglia, Iovane and Padua.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Giuseppe Messina, giuseppe.messina@uniroma5.it

†These authors share last authorship

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.