Abstract

While randomized controlled trials (RCTs) have compared bridging therapy (BT: IV thrombolysis prior to mechanical thrombectomy) with direct mechanical thrombectomy (dMT) in patients with acute ischemic stroke (AIS), their findings are inconsistent and may not fully represent real-world clinical practice. This study provides an updated synthesis of real-world observational data comparing the safety and efficacy of BT versus dMT in AIS due to large vessel occlusion (LVO). A systematic literature search was conducted across four major databases. Non-randomized studies comparing BT with dMT in AIS patients were included. Pooled odds ratios (ORs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were calculated using random-effects models for key clinical outcomes. Risk of bias was assessed using the Newcastle–Ottawa Scale, and publication bias was evaluated through funnel plot symmetry and Egger’s test. Thirty-one observational studies involving 93,297 patients (41,393 BT; 47,960 dMT) were included. BT was associated with significantly higher odds of excellent [modified Rankin Scale (mRS) 0–1; OR = 1.51, 95%CI: 1.30–1.77] and favorable (mRS 0–2; OR = 1.44, 95% CI: 1.29–1.61) recovery at 90 days, greater rates of successful reperfusion (TICI 2b/3; OR = 1.23, 95%CI: 1.09–1.39), and lower 90-day mortality (OR = 0.61, 95% CI: 0.52–0.71) compared with dMT. No significant differences were found in rates of symptomatic intracranial hemorrhage. Sensitivity analyses and publication bias assessments supported the robustness of these findings. Meta-regression identified baseline ASPECTS, NIHSS score, and several workflow intervals as significant predictors of outcome variability. These results support BT’s continued relevance in routine AIS care.

Systematic review registration:

PROSPERO no: CRD420251119894.

1 Introduction

Acute ischemic stroke (AIS) caused by large vessel occlusion (LVO) remains a leading cause of death and disability worldwide, with mechanical thrombectomy (MT) having emerged as the cornerstone of reperfusion therapy for eligible patients (1). In clinical practice, many patients who qualify for MT also meet criteria for intravenous thrombolysis (IVT), leading to the use of “bridging therapy” (BT)—IVT administration followed by MT—as a standard strategy recommended by international guidelines (2). The rationale behind BT lies in its potential to promote earlier recanalization, alter clot properties to facilitate mechanical retrieval, and address distal emboli that may be inaccessible to thrombectomy (3).

However, the clinical utility of BT compared with direct MT (dMT) has been the subject of considerable debate. While several observational studies have historically suggested that BT may be associated with better functional outcomes (4–8), randomized controlled trials (RCTs) designed to answer this question have yielded mixed results. To date, six RCTs have compared BT and dMT head-to-head, with most showing comparable efficacy and safety profiles between the two strategies (9–14). These trials have been synthesized in multiple recent meta-analyses (15, 16), which have increasingly guided clinical practice and policy recommendations.

Yet, RCTs, by design, enroll carefully selected patient populations under controlled conditions and may not fully reflect the complexity, comorbidities, and variations in care delivery present in real-world settings. Moreover, the existing RCTs differ considerably in design, population demographics, IVT protocols (e.g., alteplase vs. tenecteplase), and timing metrics, and some were underpowered or terminated early, further limiting their external validity. Real-world data—derived from observational studies, registries, and routine clinical practice—can provide valuable complementary insights, particularly concerning safety outcomes and generalizability.

A recent review by Qin et al. (17) synthesized real-world evidence from 12 registry-based studies, supporting the benefit of BT over dMT in terms of functional outcomes and mortality without a significant increase in hemorrhagic risk. However, the field has rapidly evolved, with new large-scale observational studies published in the interim. Furthermore, prior reviews often relied on unadjusted data or pooled estimates without fully addressing potential confounding through statistical matching or regression adjustment.

In this context, we conducted an updated meta-analysis focusing exclusively on non-randomized real-world studies comparing BT versus dMT in patients with AIS due to LVO. Our primary objective was to re-evaluate the safety and efficacy of BT using the most recent and methodologically robust observational evidence. Importantly, by limiting our analysis to non-RCT data, we aimed to capture a more accurate depiction of treatment performance in routine clinical practice and later compare these findings with the aggregated evidence from the six existing RCTs in the discussion.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Protocol and reporting standards

This meta-analysis was conducted in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines (18) and followed methodological recommendations outlined by the Meta-analysis Of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (MOOSE) statement (19). The protocol was registered with the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO; CRD420251119894).

2.2 Literature search strategy

A comprehensive literature search was performed across PubMed, Scopus, Web of Science, and Google Scholar from database inception through June 8th, 2025, without restrictions on language or publication status. The search strategy combined controlled vocabulary and free-text terms related to “acute ischemic stroke,” “intravenous thrombolysis,” “bridging therapy,” “mechanical thrombectomy,” and “endovascular therapy.” An experienced medical librarian validated the final strategy. The complete search syntax for each database is available in Supplementary Table S1. Additionally, we manually screened the reference lists of relevant articles and reviews for additional eligible studies (20).

2.3 Eligibility criteria

We included non-randomized studies (prospective or retrospective cohort studies, registries, or non-randomized interventional studies) that directly compared bridging therapy (IV thrombolysis prior to mechanical thrombectomy or endovascular therapy) with direct mechanical thrombectomy (dMT) in adult patients with acute ischemic stroke. Studies were eligible if they reported on at least one of the following outcomes: functional recovery [modified Rankin Scale (mRS)], successful reperfusion (Thrombolysis in Cerebral Infarction Score “TICI” 2b/3), symptomatic or asymptomatic intracerebral hemorrhage (sICH/aICH), or mortality at 90 days. Randomized controlled trials, review articles, conference abstracts without full texts, animal studies, and studies not specifying IVT status prior to MT were excluded. Duplicate reports and post-hoc analyses of randomized trials were also excluded.

2.4 Study selection

After deduplication in EndNote (Clarivate Analytics), two reviewers independently screened titles and abstracts. Full texts of potentially relevant articles were retrieved and reviewed for inclusion. Discrepancies were resolved through discussion or by the senior reviewer.

2.5 Data extraction

Data were independently extracted by two reviewers using a standardized, pilot-tested form. The following information was collected: first author, publication year, country, study design, sample size, number of patients in each group (BT and dMT), baseline characteristics (age, sex, NIHSS, ASPECTS), timing metrics (e.g., onset-to-groin puncture time), adjustment methods for confounding (e.g., propensity score matching or regression), and outcomes of interest. When numerical data were not directly reported, estimates were extracted from plots or calculated from available data. Authors were contacted for missing or unclear data as needed.

2.6 Risk of bias assessment

The methodological quality of included studies was appraised using the Newcastle–Ottawa Scale (NOS) for cohort studies (21). This tool evaluates three domains: selection, comparability, and outcome assessment, with scores ranging from 0 to 9. Studies scoring 7–9 were considered high quality, 5–6 moderate quality, and <5 low quality. All assessments were conducted independently by two reviewers, with disagreements resolved by consensus.

2.7 Statistical analysis

All analyses were performed using STATA version 18 (StataCorp LLC, College Station, TX). Pooled estimates were calculated using a random-effects model (DerSimonian and Laird method) due to expected between-study variability. The primary effect measure was the odds ratio (OR) with 95% confidence intervals (CI) for binary outcomes. Mean differences (MD) were used for continuous baseline variables. Statistical heterogeneity was assessed using the I2 statistic, with thresholds of 25, 50, and 75% representing low, moderate, and high heterogeneity, respectively. A p-value <0.10 for the Q test was considered significant for heterogeneity. Leave-one-out sensitivity analyses were conducted for all primary outcomes to test the robustness of pooled estimates. Potential publication bias was assessed visually using funnel plots and quantitatively via Egger’s regression test, with p < 0.05 suggesting significant asymmetry.

To explore potential sources of heterogeneity and identify study-level factors associated with variation in treatment effects, we performed meta-regression analyses for all reported outcomes. Univariable random-effects meta-regression models were constructed using the restricted maximum likelihood (REML) estimator. The following covariates were examined based on availability across studies: demographic variables (age, sex), vascular risk factors (hypertension, diabetes, atrial fibrillation, smoking, hypercholesterolemia, dyslipidemia, prior stroke), imaging and occlusion characteristics (ASPECTS, occlusion site including ICA, M1, or M2), medication history (anticoagulant or antiplatelet use), and workflow or timing metrics (onset-to-door, door-to-groin puncture, onset-to-recanalization, groin-to-revascularization, door-to-revascularization, onset-to-groin, onset-to-imaging, and imaging-to-groin). Regression coefficients, 95% confidence intervals, and p-values were reported.

3 Results

3.1 Literature search results

The results of the literature search and screening processes are illustrated in Figure 1. The literature search identified 750 reports, of which 233 duplicates were removed through Endnote, and 517 citations were screened. Only 106 reports were retrieved for full text screening, of which 75 were excluded either for not explicitly reporting BT use or IVT use before endovascular therapy (27 reports), being randomized trials (24 main and post-hoc reports), or review articles (24 reports). A complete list of excluded articles can be found in Supplementary Table S2. Finally, 31 articles were eligible for analysis (4–8, 22–47).

Figure 1

A PRISMA flow diagram showing the results of the database search.

3.2 Baseline characteristics of included studies

A summary of the baseline characteristics of included studies can be found in Table 1. Overall, most evidence came from prospective cohort studies (16 reports, 51.62%), followed by retrospective cohorts and registry-based studies (14 reports, 45.16%), with a single non-randomized study of intervention (3.23%). Most research was done in the United Stated (7 studies, 22.58%), followed by China (6 studies, 19.35%), and France (5 studies, 16.13%), respectively. Most studies used propensity-score matching or regression to adjust for confounding (24 studies, 77.42%). A total of 93,297 stroke patients were examined, of whom 41,393 cases underwent BT and 47,960 cases underwent dMT. The BT group was associated with a lower age (MD = −1.18 years) and higher male frequency (2.125%) than the dMT group. The NIHSS score at admission was 16.03 in the BT group and 15.79 in the dMT group (MD = 0.26). The ASPECTS score at admission was 7.82 in the BT group and 7.74 in the dMT group (MD = 0.075). The mean onset-to-groin puncture time was slightly lower in the BT group than the dMT group (MD = −54.54).

Table 1

| Author (YOP) | Design | Country | Sample | Age | Male (%) | ICA (%) | M1 (%) | M2 (%) | Confounding adjustment (regression) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BT | dMT | BT | dMT | BT | dMT | BT | dMT | BT | dMT | BT | dMT | ||||

| Chang et al. (2020) (24) | PC | USA | 87 | 83 | 68.4 | 69.8 | 46 | 38.5 | 28.5 | 32 | 55 | 50.5 | 17 | 16 | Yes |

| Da Ros (2021) (56) | RC | USA | 1,226 | 1,669 | 69.23 | 69.9 | 45.9 | 45.8 | – | – | – | – | – | – | Yes |

| Derraz et al. (2023) (25) | RC | USA | 603 | 660 | 66.8 | 68.4 | 56.6 | 55.6 | 27.5 | 24.1 | 53.2 | 53.6 | 4.1 | 6.5 | Yes |

| Di Maria et al. (2018) (5) | PC | France | 976 | 531 | 67.2 | 67.6 | 54.3 | 51.2 | 17.2 | 21.3 | 51.1 | 50.7 | 13.2 | 12.2 | Yes |

| Dicpinigaitis et al. (2022) (26) | RC | USA | 19,735 | 28,790 | 68.9 | 69.7 | 49.1 | 47 | – | – | – | – | – | – | Yes |

| El Malky et al. (2022) (27) | RC | Egypt | 150 | 51 | – | – | – | – | 16 | 11.8 | 53.3 | 64.7 | – | – | Yes |

| Faizy et al. (2022) (28) | RC | USA | 365 | 352 | 75 | 76 | 52 | 45 | 18 | 22 | 59 | 60 | 23 | 18 | Yes |

| Fang et al. (2022) (29) | pc | China | 257 | 593 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | Yes |

| Ferrigno et al. (2018) (6) | PC | France | 348 | 137 | 66.3 | 67.1 | 46 | 44.5 | – | – | – | – | – | – | Yes |

| Gong et al. (2019) (31) | RC | China | 42 | 31 | 69 | 71 | 35.71 | 51.61 | – | – | – | – | – | – | Yes |

| Guedin et al. (2015) (32) | PC | France | 28 | 40 | 69.2 | 64.6 | 39.3 | 37.5 | – | – | – | – | – | – | No |

| Guo et al. (2024) (33) | RC | China | 119 | 529 | 62 | 65 | 74.8 | 74.6 | – | – | – | – | – | – | Yes |

| Huu An et al. (2022) (34) | PC | Vietnam | 30 | 30 | 66.5 | 64 | 70 | 60 | 40 | 33.3 | 50 | 60 | 10 | 6.7 | No |

| Kaesmacher et al. (2018) (35) | RC | Germany | 160 | 79 | 69.8 | 73.3 | 45.6 | 45.6 | – | – | – | – | – | – | Yes |

| Kurminas et al. (2020) (37) | PC | Italy | 38 | 65 | 67.1 | 68.4 | 42.1 | 40 | – | – | – | – | – | – | No |

| Le Floch et al. (2023) (7) | RC | France | 570 | 562 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | Yes |

| Maier et al. (2017) (39) | PC | Germany | 81 | 28 | 75 | 76 | 59.4 | 42.9 | – | – | – | – | – | – | No |

| Molad et al. (2023) (40) | RC | Israel | 195 | 213 | 71.4 | 68.9 | 53.25 | 48.3 | 20.3 | 24.7 | 53.25 | 48.35 | 19.3 | 14.95 | No |

| Seetge et al. (2024) (42) | PC | Hungary | 51 | 31 | 67 | 72 | 47.1 | 35.5 | – | – | – | – | – | – | Yes |

| Smith et al. (2006) (44) | NRSI | USA | 30 | 81 | 65.4 | 66.5 | 43.3 | 43.2 | – | – | – | – | – | – | No |

| Tong et al. (2021) (45) | PC | China | 426 | 600 | 64 | 66 | 62.4 | 65.3 | 26.1 | 28.2 | 45.1 | 39.8 | 9.4 | 9 | Yes |

| Wang et al. (2017) (46) | RC | China | 138 | 138 | 67 | 67 | 56.5 | 55.1 | 35.5 | 42.7 | 60.1 | 50 | 4.3 | 7.2 | Yes |

| Weber et al. (2017) (47) | RC | Germany | 105 | 145 | 60.2 | 69.3 | 49.5 | 53.8 | 18.1 | 20.7 | 45.7 | 35.9 | 19 | 15.9 | No |

| Smith et al. (2022) (43) | RC | USA | 10,548 | 5,284 | 70 | 74 | 50.9 | 47.8 | 14.3 | 14.7 | 49.1 | 49.5 | 20.2 | 19.1 | Yes |

| Ahmed et al. (2021) (4) | PC | EU, Norway, Iceland | 3,944 | 72 (62–80) | 50.1 | – | – | – | – | – | – | Yes | |||

| Casetta et al. (2019) (22) | PC | Italy | 635 | 513 | 67.6 | 68.8 | 49.3 | 48.9 | – | – | 48.8 | 44.8 | 14.2 | 12.5 | Yes |

| Chalos et al. (2019) (23) | PC | Netherlands | 1,161 | 324 | 70 | 72 | 54 | 53 | 6.4 | 3.9 | 58 | 61 | 13 | 11 | Yes |

| Geng et al. (2021) (30) | RC | China | 2069 | 5,605 | 68 | 67 | 60 | 60 | – | – | – | – | – | – | Yes |

| Leker et al. (2018) (38) | PC | Israel | 159 | 111 | 68.1 | 67.4 | 57 | 52.25 | – | – | – | – | – | – | Yes |

| Minnerup et al. (2016) (8) | PC | France | 603 | 504 | 68.3 | 68.7 | 50.4 | 48 | 32.8 | 34.5 | 44.4 | 37.3 | 10.3 | 13.3 | Yes |

| Park et al. (2017) (41) | PC | Korea | 458 | 181 | 68 | 69 | 57 | 57 | 40 | 39 | – | – | – | – | Yes |

Baseline characteristics of real-world studies comparing BT to dMT in acute stroke settings.

YOP, year of publication; PC, prospective cohort; RC, retrospective cohort; EU, European union; USA, United States of America; NRSI, non-randomized study of intervention. Age is presented as mean.

3.3 Methodological quality

A summary of the methodological quality of included studies using the NOS scale can be found in Table 2. Overall, a total of 24 studies had good methodological quality, while 7 studies had fair quality.

Table 2

| Author (YOP) | Selection | Comparability | Outcome | Overall Rating | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| D1 | D2 | D3 | D4 | D5 | D6 | D7 | D8 | ||

| Chang et al. (2020) (24) | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | Good |

| Da Ros (2021) (56) | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | Good |

| Derraz et al. (2023) (25) | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | Good |

| Di Maria et al. (2018) (5) | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | Good |

| Dicpinigaitis et al. (2022) (26) | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | Good |

| El Malky et al. (2022) (27) | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | Good |

| Faizy et al. (2022) (28) | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | Good |

| Fang et al. (2022) (29) | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | Good |

| Ferrigno et al. (2018) (6) | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | Good |

| Gong et al. (2019) (31) | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | Good |

| Guedin et al. (2015) (32) | * | * | * | * | – | * | * | * | Fair |

| Guo et al. (2024) (33) | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | Good |

| Huu An et al. (2022) (34) | * | * | * | * | – | * | * | * | Fair |

| Kaesmacher et al. (2018) (35) | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | RC |

| Kurminas et al. (2020) (37) | * | * | * | * | – | * | * | * | Fair |

| Le Floch et al. (2023) (7) | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | Good |

| Maier et al. (2017) (39) | * | * | * | * | – | * | * | * | Fair |

| Molad et al. (2023) (40) | * | * | * | * | – | * | * | * | Fair |

| Seetge et al. (2024) (42) | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | Good |

| Smith et al. (2006) (44) | * | * | * | * | – | * | * | * | Fair |

| Tong et al. (2021) (45) | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | Good |

| Wang et al. (2017) (46) | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | Good |

| Weber et al. (2017) (47) | * | * | * | * | – | * | * | * | Fair |

| Smith et al. (2022) (43) | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | RC |

| Ahmed et al. (2021) (4) | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | Good |

| Casetta et al. (2019) (22) | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | Good |

| Chalos et al. (2019) (23) | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | Good |

| Geng et al. (2021) (30) | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | Good |

| Leker et al. (2018) (38) | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | Good |

| Minnerup et al. (2016) (8) | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | Good |

| Park et al. (2017) (41) | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | Good |

A summary of the methodological quality of included studies assessed by the Newcastle Ottawa Scale for cohort studies.

YOP, year of publication. D1, Representativeness of the exposed cohort; D2, selection of the non-exposed cohort; D3, ascertainment of exposure; D4, demonstration that outcome of interest was not present at start of study; D5, Comparability of cohorts on the basis of the design or analysis; D6, Assessment of outcome; D7, was follow-up long enough for outcomes to occur; D8, Adequacy of follow up of cohorts.

3.4 Excellent functional recovery (mRS 0–1) at 90 days

Eleven studies were eligible for meta-analysis. BT was associated with a significantly greater odds of excellent functional recovery compared to dMT (OR = 1.51; 95% CI: 1.30, 1.77) (Figure 2). Although heterogeneity was moderate (I2 = 59.99%, p = 0.02), the leave-one-out sensitivity analysis showed no change in the reported estimate (Supplementary Figure S1). The funnel plot showed no significant deviation (Supplementary Figure S2), and the Egger’s regression test showed no risk of publication bias (p = 0.680).

Figure 2

Forest plot showing the difference in excellent recovery between bridging therapy and direct mechanical thrombectomy at 90 days.

3.5 Favorable functional recovery (mRS 0–2) at 90 days

Twenty-two studies were eligible for meta-analysis. BT was associated with a significantly greater odds of favorable functional recovery compared to dMT (OR = 1.44; 95% CI: 1.29, 1.61) (Figure 3). Although heterogeneity was moderate (I2 = 53.75%, p = 0.01), the leave-one-out sensitivity analysis showed no change in the reported estimate (Supplementary Figure S3). The funnel plot showed no significant deviation (Supplementary Figure S4), and the Egger’s regression test showed no risk of publication bias (p = 0.881).

Figure 3

Forest plot showing the difference in favorable recovery between bridging therapy and direct mechanical thrombectomy at 90 days.

3.6 Successful reperfusion (TICI 2b/3) at 90 days

Twenty-four studies were eligible for meta-analysis. BT was associated with a significantly greater odds of successful reperfusion compared to dMT (OR = 1.23; 95% CI: 1.09, 1.39) (Figure 4). Although heterogeneity was moderate (I2 = 61.73%, p < 0.01), the leave-one-out sensitivity analysis showed no change in the reported estimate (Supplementary Figure S5). The funnel plot showed no significant deviation (Supplementary Figure S6), and the Egger’s regression test showed no risk of publication bias (p = 0.986).

Figure 4

![Forest plot showing the odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals for various studies comparing BT and dMT treatments. Each study is represented with a blue square and line indicating the odds ratio and its confidence interval. The sizes of the squares are proportional to the study weight. A red vertical line represents the null hypothesis (odds ratio of 1). The overall effect is shown as a diamond at the bottom, with an odds ratio of 1.23 [1.09, 1.39]. Heterogeneity statistics are provided below the plot.](https://www.frontiersin.org/files/Articles/1731626/xml-images/fmed-12-1731626-g004.webp)

Forest plot showing the difference in successful reperfusion between bridging therapy and direct mechanical thrombectomy at 90 days.

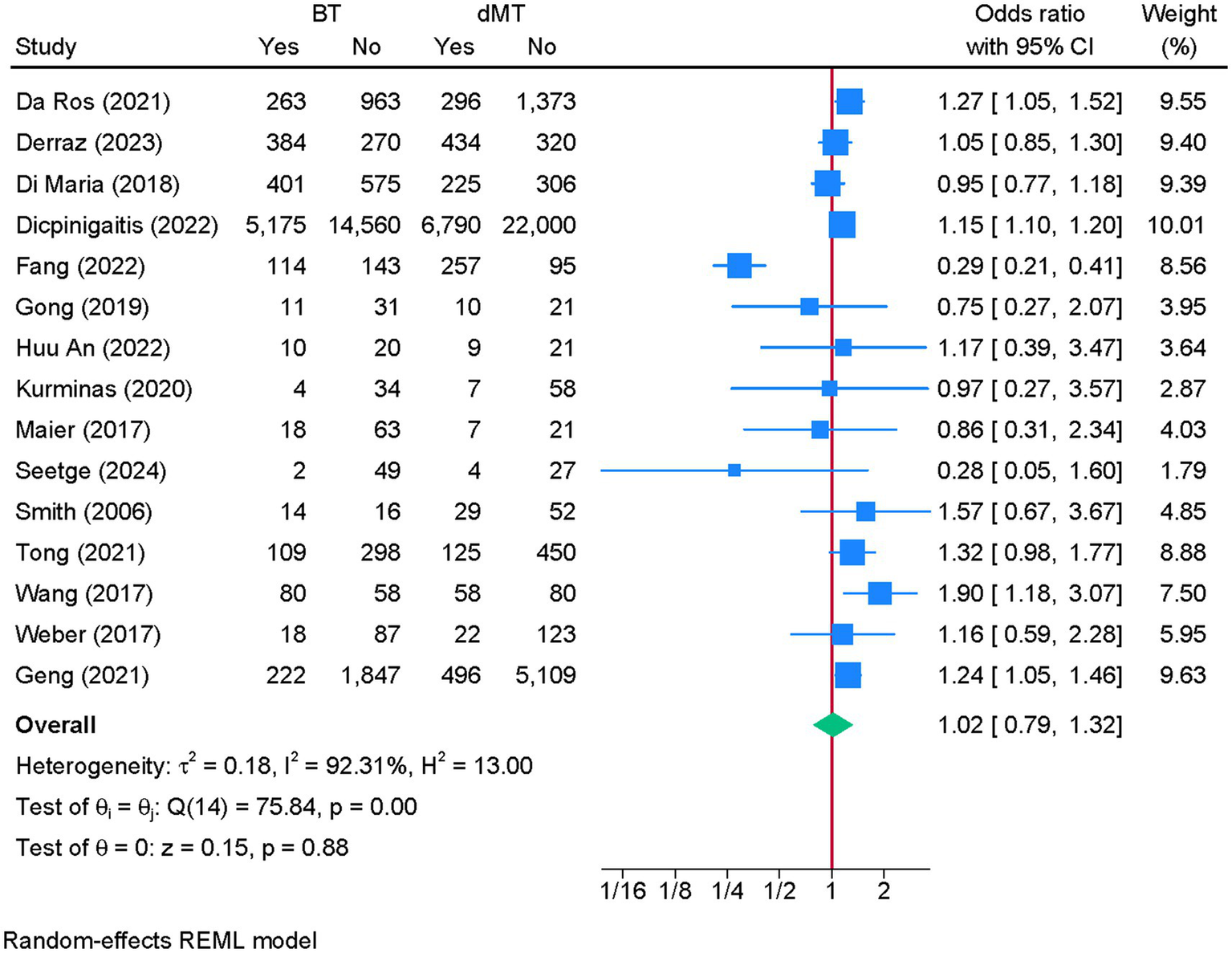

3.7 aICH at 90 days

Fifteen studies were eligible for meta-analysis. No difference in the risk of aICH was noted between BT and dMT (OR = 1.02; 95% CI: 0.79, 1.32) (Figure 5). Heterogeneity was high (I2 = 92.31%, p < 0.001). The leave-one-out sensitivity analysis showed a significantly higher risk of aICH with BT vs. dMT after excluding the study of Fang et al. (29) (OR = 1.15; 95% CI: 1.11, 1.20) (Figure 6). The funnel plot showed no significant deviation (Supplementary Figure S7), and the Egger’s regression test showed no risk of publication bias (p = 0.494).

Figure 5

Forest plot showing the difference in the risk of any intracranial hemorrhage between bridging therapy and direct mechanical thrombectomy at 90 days.

Figure 6

Sensitivity analysis of the difference in the risk of any intracranial hemorrhage between bridging therapy and direct mechanical thrombectomy at 90 days.

3.8 sICH at 90 days

Nineteen studies were eligible for meta-analysis. There was no difference in the risk of sICH between BT and dMT (OR = 1.07; 95% CI: 0.94, 1.22) (Figure 7). No heterogeneity was observed (I2 = 0%, p = 0.48). The funnel plot showed no significant deviation (Supplementary Figure S8), and the Egger’s regression test showed no risk of publication bias (p = 0.736).

Figure 7

Forest plot showing the difference in the risk of symptomatic intracranial hemorrhage between bridging therapy and direct mechanical thrombectomy at 90 days.

3.9 Mortality at 90 days

Twenty-two studies were eligible for meta-analysis. BT was associated with a significantly lower risk of 90-day mortality compared to dMT (OR = 0.61; 95% CI: 0.52, 0.71) (Figure 8). Although heterogeneity was moderate (I2 = 60.20%, p < 0.01), the leave-one-out sensitivity analysis showed no change in the reported estimate (Supplementary Figure S9). The funnel plot showed no significant deviation (Supplementary Figure S10), and the Egger’s regression test showed no risk of publication bias (p = 0.406).

Figure 8

Forest plot showing the difference in the risk of death between bridging therapy and direct mechanical thrombectomy at 90 days.

3.10 Meta-regression analyses

To explore sources of heterogeneity and potential effect modifiers, we conducted meta-regression analyses for all primary outcomes using study-level covariates (Table 3). For excellent functional recovery, higher baseline ASPECTS (p = 0.004), higher baseline NIHSS (p = 0.016), lower smoking rates (p = 0.037), lower onset-to-imaging time (p = 0.042), and higher percentage of male patients (p = 0.040) were significantly associated with greater effect estimates. For favorable recovery, antiplatelet use, ASPECTS score, and imaging-to-groin time were among the significant predictors. For sICH, male sex, hypertension, diabetes, NIHSS, ASPECTS, and onset-to-groin time showed significant associations. For mortality and reperfusion, hypertension, prior stroke, door-to-groin time, and ASPECTS were significant modifiers.

Table 3

| Characteristic | Coefficient | p-value | Low CI | High CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Outcome: excellent functional recovery | ||||

| Male (per %) | 0.0646 | 0.0400 | 0.0030 | 0.1262 |

| Smoking (per %) | −0.0580 | 0.0370 | −0.1127 | −0.0034 |

| Mean baseline NIHSS score (per point) | 0.2267 | 0.0160 | 0.0417 | 0.4118 |

| Mean baseline ASPECT score (per point) | 1.1438 | 0.0040 | 0.3577 | 1.9298 |

| Mean onset-to-imaging time (per min) | −0.0267 | 0.0420 | −0.0525 | −0.0010 |

| Outcome: mortality | ||||

| Hypertension (per %) | 0.0318 | 0.0130 | 0.0068 | 0.0567 |

| Prior stroke (per %) | 0.0339 | 0.0040 | 0.0106 | 0.0572 |

| Mean baseline ASPECT score (per point) | −1.3557 | 0.0000 | −2.0898 | −0.6217 |

| Outcome: sICH | ||||

| Male (per %) | −0.0659 | 0.0390 | −0.1284 | −0.0035 |

| Hypertension (per %) | 0.0439 | 0.0230 | 0.0059 | 0.0818 |

| Diabetes (per %) | −0.0885 | 0.0210 | −0.1637 | −0.0134 |

| Mean baseline NIHSS score (per point) | −0.1833 | 0.0420 | −0.3604 | −0.0063 |

| Mean baseline ASPECT score (per point) | −1.1361 | 0.0280 | −2.1524 | −0.1199 |

| Mean onset-to-groin time (min) | 0.0037 | 0.0460 | 0.0001 | 0.0074 |

| Outcome: favorable functional recovery | ||||

| Hypertension (per %) | −0.0254 | 0.0280 | −0.0481 | −0.0027 |

| Stroke location - M1 (per %) | −0.0280 | 0.0480 | −0.0558 | −0.0002 |

| General anesthesia (per %) | −0.0542 | 0.0020 | −0.0887 | −0.0198 |

| Antiplatelet use (per %) | 0.0420 | 0.0030 | 0.0147 | 0.0693 |

| Mean baseline ASPECT score (per point) | 1.2507 | 0.0000 | 0.5981 | 1.9034 |

| Mean imaging-to-groin time (per min) | −0.0216 | 0.0300 | −0.0411 | −0.0021 |

| Outcome: successful reperfusion | ||||

| Prior stroke (per %) | −0.0260 | 0.0370 | −0.0504 | −0.0016 |

| Mean door-to-groin time (per min) | −0.0162 | 0.0210 | −0.0299 | −0.0025 |

A summary of the significant determinates of reported outcomes based on meta-regression analyses.

sICH, symptomatic intracranial hemorrhage; CI, confidence interval. Meta-regression models additionally examined the following variables, which were not significantly associated with any of the reported outcomes: age, sex (female %), diabetes mellitus, atrial fibrillation, smoking status, hypercholesterolemia, dyslipidemia, prior stroke, internal carotid artery (ICA) occlusion rate, M2 occlusion rate, use of anticoagulant or antiplatelet therapy, and multiple workflow-related time intervals (onset-to-door, door-to-groin puncture, onset-to-recanalization, groin-to-revascularization, door-to-revascularization, onset-to-groin, and imaging-to-groin).

4 Discussion

This updated meta-analysis of over 93,000 real-world patients offers compelling evidence favoring the use of BT over dMT in AIS. Compared with dMT, BT was associated with significantly greater odds of achieving excellent and favorable functional outcomes at 90 days, higher rates of successful reperfusion, and lower mortality—without a corresponding increase in the risk of hemorrhagic complications. These findings are consistent with, and extend upon, prior real-world data (17) and provide critical complementary insights to those generated by RCTs (15).

Over the past few years, at least six major RCTs—DIRECT-MT (9), DEVT (10), SKIP (11), MR CLEAN-NO IV (12), SWIFT-DIRECT (13), and DIRECT-SAFE (14)—have attempted to resolve the clinical equipoise surrounding BT versus dMT in IVT-eligible patients. Pooled results from these RCTs generally support the non-inferiority of dMT for favorable functional outcomes (15, 16, 48), but their conclusions are tempered by regional heterogeneity, differences in imaging and selection protocols, and strict eligibility criteria. For example, Liu et al. (15) emphasized that while dMT met non-inferiority thresholds in some trials, others failed to demonstrate equivalence, underscoring unresolved uncertainty in specific subgroups.

In contrast, observational data—including the current study—reflect broader clinical settings, encompassing variations in hospital infrastructure, workflow logistics, and patient-level risk factors that are often underrepresented in RCTs. In this context, the term ‘real-world’ refers to several aspects of routine clinical practice that differ from the tightly controlled conditions of RCTs. These include broader and more heterogeneous inclusion criteria, encompassing patients with wider ranges of stroke severity, comorbidities, imaging profiles (including lower ASPECTS), and treatment windows. Real-world cohorts also reflect substantial variability in workflow metrics—such as onset-to-imaging, door-to-needle, and door-to-groin times—as well as differences in hospital infrastructure, transfer patterns, operator expertise, and local protocols for IVT and thrombectomy. Additionally, physician decision-making, system-level delays, and regional differences in prehospital logistics influence treatment delivery in ways not captured in trial settings. Together, these elements provide a more comprehensive and externally valid representation of how BT and dMT perform in everyday practice. Our findings align closely with those of Katsanos et al. (49), who similarly reported superior functional outcomes and reduced mortality with BT across 11,798 patients, even after adjustment for confounders. Likewise, a recent umbrella review by Campbell et al. (50) reiterated the modest yet consistent benefits of BT for functional recovery and reperfusion success, particularly in systems with efficient in-hospital workflows and minimal IVT-to-groin delay.

Importantly, this study contributes an up-to-date synthesis of real-world data at a larger scale than any previously published review (17). Compared to Waller et al. (51), who summarized older data from 2015 to 2020 and noted favorable BT outcomes in patients with anterior circulation LVOs, our analysis captures evolving practices, wider geographical representation, and improved adjustment for confounding via propensity-score matching or regression methods in 77% of included studies.

Concerns surrounding the potential risks of BT—particularly increased rates of thrombus fragmentation, distal embolization, or hemorrhagic transformation—remain important. However, in our meta-analysis, BT was not associated with increased rates of either symptomatic or asymptomatic intracerebral hemorrhage. However, this conclusion requires caution, particularly for aICH. The substantial heterogeneity among studies reporting aICH and the sensitivity finding—where exclusion of a single study shifted the effect toward significance—indicate that uncertainty remains. Differences in imaging criteria, reporting standards, and patient selection may contribute to this variability, making the true effect of BT on aICH less certain than the pooled summary suggests. This echoes the conclusions of Tsivgoulis et al. (52), who reported no excess bleeding risk with BT in their large observational cohort. Furthermore, the absence of heterogeneity for sICH across our included studies supports the robustness of this finding.

From a pathophysiological perspective, IVT may facilitate microvascular reperfusion, soften thrombus structure, and promote early partial recanalization before thrombectomy—mechanisms hypothesized in several translational studies and supported by improved TICI 2b/3 rates in both this and earlier meta-analyses (49, 53). Moreover, BT may act as a safety net in cases of failed or delayed thrombectomy, a scenario not uncommon in real-world settings but under-represented in RCTs. Additionally, intravenous thrombolysis may preferentially target the peripheral, branching projections of the clot—a phenomenon often described as the ‘finger-like thrombus’ effect—thereby reducing clot anchoring strength and improving device engagement during thrombectomy (54). IVT has also been shown to enhance microcirculatory reperfusion by dissolving distal microemboli and restoring capillary-level flow, effects that are not directly achieved by mechanical thrombectomy alone (55). Together, these mechanisms provide complementary biological pathways through which BT may improve successful reperfusion rates and functional outcomes, particularly in real-world settings where procedural delays or anatomical challenges may limit the effectiveness of dMT.

To further explore sources of heterogeneity and strengthen the interpretability of our findings, we performed meta-regression analyses across all primary outcomes using study-level covariates. Several demographics, clinical, imaging, and workflow-related characteristics were identified as significant modifiers of treatment effect (Table 3). Higher baseline ASPECTS and NIHSS scores were consistently associated with better odds of functional recovery, underscoring the importance of initial infarct size and neurological severity. Time intervals—particularly onset-to-imaging, imaging-to-groin, and door-to-groin metrics—also influenced effect estimates, highlighting the well-established impact of workflow efficiency on reperfusion success. In addition, risk-factor profiles such as hypertension, prior stroke, and smoking contributed to variations in mortality, sICH, or reperfusion outcomes. Although these associations should be interpreted cautiously given the ecological nature of study-level meta-regression, they provide important insights into factors that may shape real-world treatment performance and help explain some of the heterogeneity observed across included studies.

Still, our study is not without limitations. The non-randomized design of included studies introduces the possibility of residual confounding, although most employed statistical adjustments. The definition and adjudication of outcomes (e.g., functional independence, hemorrhage classification) varied across studies. Also, the predominance of data from high-income settings may limit generalizability to low-resource environments. Additionally, although most included studies performed statistical adjustment, the extent to which they accounted for thrombus characteristics or collateral circulation varied substantially. Several studies included imaging-based covariates such as collateral grade, mCTA collateral score, pial arterial collateral status, ASITN/SIR collateral grade, ASPECTS, and occlusion site, which partially capture thrombus burden and baseline tissue viability (see Supplementary Table S3). However, detailed thrombus morphology (e.g., clot length, clot perviousness) and standardized collateral scoring were not uniformly reported across studies. This heterogeneity may introduce residual confounding in reperfusion and functional outcomes. As such, while the majority of analyses adjusted for key clinical and imaging variables, incomplete adjustment for thrombus- and collateral-related factors remains an inherent limitation of real-world observational evidence.

Nevertheless, our findings offer a clinically meaningful perspective: in routine clinical practice, BT appears to confer modest yet consistent advantages in functional recovery and survival without added hemorrhagic risk. These real-world benefits contrast with the marginal differences reported in RCTs, raising important questions about the external validity of trial-based treatment algorithms. A structured comparison of RCT evidence versus real-world data is presented in Table 4 to illustrate these differences. Future research should prioritize individual patient data meta-analyses and explore tailored approaches to stroke triage, perhaps incorporating clot burden, collateral status, and time metrics into treatment selection.

Table 4

| Domain | RCTs [del Cuadra-Campos et al. (16)] | Real-world meta-analysis (current study) |

|---|---|---|

| Population size | 2,334 patients (6 RCTs) | 93,297 patients (31 observational studies) |

| Study design | Highly selected, strictly controlled; non-inferiority frameworks | Heterogeneous, routine clinical care; broad inclusion |

| Patient selection | Strict IVT eligibility; excludes posterior circulation and late-presenters | Includes diverse presentations, comorbidities, workflows; more inclusive |

| Baseline stroke severity (NIHSS) | Median 15–19 across trials | Wider range; often higher variability across centers |

| Imaging selection (ASPECTS) | Narrow ranges (typically ASPECTS 7–10) | Broader distribution; includes lower ASPECTS in some studies |

| Occlusion sites | Mostly ICA or M1; minimal M2 | ICA, M1, M2, and mixed anterior circulation distributions |

| Workflow metrics | Very short needle-to-groin intervals (8–44 min); door-to-puncture tightly controlled | Highly variable (urban vs. rural, primary vs. comprehensive centers) |

| Intervention fidelity | Protocol-driven; minimal delays; uniform alteplase use | Real-world variation in IVT-to-MT timing, operator skill, center resources |

| Functional outcomes (mRS 0–2) | OR ≈ 0.93 (no difference) | OR = 1.44 favoring BT |

| Excellent outcomes (mRS 0–1) | Not consistently reported across RCTs | OR = 1.51 favoring BT |

| Reperfusion success (TICI ≥2b/3) | Slight advantage for BT (OR ≈ 0.75 for dMT vs. BT) | Significant advantage for BT (OR = 1.23) |

| 90-day mortality | No significant difference | Lower mortality with BT (OR = 0.61) |

| Hemorrhagic complications | No difference in sICH | No difference in sICH; aICH uncertain due to high heterogeneity |

| External validity | Limited (direct-transfer to MT-capable centers only) | High; includes varied hospital systems, workflows, geographies |

Comparative summary of RCT evidence versus real-world meta-analysis findings for bridging therapy in acute ischemic stroke.

Data on RCTs are derived from the recent meta-analysis by del Cuadra-Campos et al. (16). AIS, acute ischemic stroke; LVO, large vessel occlusion; BT, bridging therapy; dMT, direct mechanical thrombectomy; RCT, randomized controlled trial; IVT, intravenous thrombolysis; mRS, modified Rankin Scale; TICI, Thrombolysis in Cerebral Infarction; ICA, internal carotid artery; NIHSS, National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale; ASPECTS, Alberta Stroke Program Early CT Score; EMS, emergency medical services; sICH, symptomatic intracranial hemorrhage; aICH, asymptomatic intracranial hemorrhage.

This updated meta-analysis of real-world observational data reinforces the clinical value of bridging therapy in patients with acute ischemic stroke due to large vessel occlusion. Compared to direct mechanical thrombectomy, bridging therapy was associated with significantly improved functional outcomes, higher rates of successful reperfusion, and lower mortality—without an increased risk of hemorrhagic complications. These findings highlight the continued relevance of intravenous thrombolysis as a component of acute stroke care and suggest that, in real-world settings, the benefits of bridging therapy may be more pronounced than those observed in randomized controlled trials. As treatment paradigms evolve, individualized decision-making that incorporates both trial-based evidence and real-world data will be essential to optimizing outcomes for stroke patients.

Statements

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author contributions

YH: Conceptualization, Data curation, Writing – original draft. XW: Formal analysis, Methodology, Writing – review & editing. GS: Investigation, Software, Validation, Writing – review & editing. XM: Conceptualization, Project administration, Supervision, Validation, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declared that financial support was not received for this work and/or its publication.

Conflict of interest

The author(s) declared that this work was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declared that Generative AI was not used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fmed.2025.1731626/full#supplementary-material

SUPPLEMENTARY FIGURE S1Sensitivity analysis of the excellent functional recovery outcome between bridging therapy and direct mechanical thrombectomy.

SUPPLEMENTARY FIGURE S2Funnel plot showing the risk of publication bias in the excellent functional recovery outcome.

SUPPLEMENTARY FIGURE S3Sensitivity analysis of the favorable functional recovery outcome between bridging therapy and direct mechanical thrombectomy.

SUPPLEMENTARY FIGURE S4Funnel plot showing the risk of publication bias in the favorable functional recovery outcome.

SUPPLEMENTARY FIGURE S5Sensitivity analysis of successful reperfusion outcome between bridging therapy and direct mechanical thrombectomy.

SUPPLEMENTARY FIGURE S6Funnel plot showing the risk of publication bias in the successful reperfusion outcome.

SUPPLEMENTARY FIGURE S7Funnel plot showing the risk of publication bias in the any intracranial hemorrhage outcome.

SUPPLEMENTARY FIGURE S8Funnel plot showing the risk of publication bias in the symptomatic intracranial hemorrhage outcome.

SUPPLEMENTARY FIGURE S9Sensitivity analysis of mortality risk between bridging therapy and direct mechanical thrombectomy.

SUPPLEMENTARY FIGURE S10Funnel plot showing the risk of publication bias in the mortality outcome.

References

1.

Saini V Guada L Yavagal DR . Global epidemiology of stroke and access to acute ischemic stroke interventions. Neurology. (2021) 97:S6–S16. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000012781,

2.

Berge E Whiteley W Audebert H De Marchis GM Fonseca AC Padiglioni C et al . European stroke organisation (ESO) guidelines on intravenous thrombolysis for acute ischaemic stroke. Eur Stroke J. (2021) 6:I-LXII. doi: 10.1177/2396987321989865,

3.

Mazighi M Meseguer E Labreuche J Amarenco P . Bridging therapy in acute ischemic stroke: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Stroke. (2012) 43:1302–8. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.111.635029,

4.

Ahmed N Mazya M Nunes AP Moreira T Ollikainen JP Escudero-Martinez I et al . Safety and outcomes of thrombectomy in ischemic stroke with vs without IV thrombolysis. Neurology. (2021) 97:e765–76. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000012327,

5.

Di Maria F Mazighi M Kyheng M Labreuche J Rodesch G Consoli A et al . Intravenous thrombolysis prior to mechanical thrombectomy in acute ischemic stroke: silver bullet or useless bystander?J Stroke. (2018) 20:385–93. doi: 10.5853/jos.2018.01543,

6.

Ferrigno M Bricout N Leys D Estrade L Cordonnier C Personnic T et al . Intravenous recombinant tissue-type plasminogen activator: influence on outcome in anterior circulation ischemic stroke treated by mechanical thrombectomy. Stroke. (2018) 49:1377–85. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.118.020490,

7.

Le Floch A Clarençon F Rouchaud A Kyheng M Labreuche J Sibon I et al . Influence of prior intravenous thrombolysis in patients treated with mechanical thrombectomy for M2 occlusions: insight from the endovascular treatment in ischemic stroke (ETIS) registry. J Neurointerv Surg. (2023) 15:e289–97. doi: 10.1136/jnis-2022-019672

8.

Minnerup J Wersching H Teuber A Wellmann J Eyding J Weber R et al . Outcome after thrombectomy and intravenous thrombolysis in patients with acute ischemic stroke: a prospective observational study. Stroke. (2016) 47:1584–92. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.116.012619,

9.

Yang P Zhang Y Zhang L Zhang Y Treurniet KM Chen W et al . Endovascular thrombectomy with or without intravenous alteplase in acute stroke. N Engl J Med. (2020) 382:1981–93. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2001123,

10.

Zi W Qiu Z Li F Sang H Wu D Luo W et al . Effect of endovascular treatment alone vs intravenous alteplase plus endovascular treatment on functional Independence in patients with acute ischemic stroke: the DEVT randomized clinical trial. JAMA. (2021) 325:234–43. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.23523,

11.

Suzuki K Matsumaru Y Takeuchi M Morimoto M Kanazawa R Takayama Y et al . Effect of mechanical thrombectomy without vs with intravenous thrombolysis on functional outcome among patients with acute ischemic stroke: the SKIP randomized clinical trial. JAMA. (2021) 325:244–53. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.23522,

12.

LeCouffe NE Kappelhof M Treurniet KM Rinkel LA Bruggeman AE Berkhemer OA et al . A randomized trial of intravenous alteplase before endovascular treatment for stroke. N Engl J Med. (2021) 385:1833–44. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2107727

13.

Fischer U Kaesmacher J Plattner PS Bütikofer L Mordasini P Deppeler S et al . Swift direct: solitaire™ with the intention for thrombectomy plus intravenous t-PA versus direct solitaire™ stent-retriever thrombectomy in acute anterior circulation stroke: methodology of a randomized, controlled, multicentre study. Int J Stroke. (2022) 17:698–705. doi: 10.1177/17474930211048768,

14.

Mitchell PJ Yan B Churilov L Dowling RJ Bush S Nguyen T et al . DIRECT-SAFE: a randomized controlled trial of DIRECT endovascular clot retrieval versus standard bridging therapy. J Stroke. (2022) 24:57–64. doi: 10.5853/jos.2021.03475,

15.

Liu W Zhao J Liu H Li T Zhou T He Y et al . Safety and efficacy of direct thrombectomy versus bridging therapy in patients with acute ischemic stroke eligible for intravenous thrombolysis: a Meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. World Neurosurg. (2023) 175:113–121.e3. doi: 10.1016/j.wneu.2023.04.018,

16.

del Carmen Cuadra-Campos M Vásquez-Tirado GA del Cielo Bravo-Sotero M . Direct mechanical thrombectomy versus bridging therapy in acute ischemic stroke: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials. World Neurosurg X. (2024) 21:100250. doi: 10.1016/j.wnsx.2023.100250,

17.

Qin B Wei T Gao W Qin HX Liang YM Qin C et al . Real-world setting comparison of bridging therapy versus direct mechanical thrombectomy for acute ischemic stroke: a meta-analysis. Clinics. (2024) 79:100394. doi: 10.1016/j.clinsp.2024.100394,

18.

Page MJ McKenzie JE Bossuyt PM Boutron I Hoffmann TC Mulrow CD et al . The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ. (2021) 372:n71. doi: 10.1136/bmj.n71

19.

Brooke BS Schwartz TA Pawlik TM . MOOSE reporting guidelines for meta-analyses of observational studies. JAMA Surg. (2021) 156:787–8. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2021.0522,

20.

Abdelaal A Serhan HA Mahmoud MA Rodriguez-Morales AJ Sah R . Ophthalmic manifestations of monkeypox virus. Eye. (2023) 37:383–5. doi: 10.1038/s41433-022-02195-z,

21.

Wells G.A. Shea B. O’Connell D. Peterson J. Welch V. Losos M. et al . The Newcastle-Ottawa scale (NOS) for assessing the quality of nonrandomised studies in meta-analyses. Ottawa: Ottawa Hospital Research Institute (2000).

22.

Casetta I Fainardi E Saia V Pracucci G Padroni M Renieri L et al . Endovascular thrombectomy for acute ischemic stroke beyond 6 hours from onset: a real-world experience. Stroke. (2020) 51:2051–7. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.119.027974,

23.

Chalos V LeCouffe NE Uyttenboogaart M Lingsma HF Mulder MJ Venema E et al . Endovascular treatment with or without prior intravenous alteplase for acute ischemic stroke. J Am Heart Assoc. (2019) 8:e011592. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.118.011592

24.

Chang A Beheshtian E Llinas EJ Idowu OR Marsh EB . Intravenous tissue plasminogen activator in combination with mechanical thrombectomy: clot migration, intracranial bleeding, and the impact of "drip and ship" on effectiveness and outcomes. Front Neurol. (2020) 11:585929. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2020.585929,

25.

Derraz I Moulin S Gory B Kyheng M Arquizan C Costalat V et al . Endovascular thrombectomy outcomes with and without intravenous thrombolysis for large ischemic cores identified with CT or MRI. Radiology. (2023) 309:e230440. doi: 10.1148/radiol.230440,

26.

Dicpinigaitis AJ Gandhi CD Shah SP Galea VP Cooper JB Feldstein E et al . Endovascular thrombectomy with and without preceding intravenous thrombolysis for treatment of large vessel anterior circulation stroke: a cross-sectional analysis of 50,000 patients. J Neurol Sci. (2022) 434:120168. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2022.120168,

27.

El Malky I Abdelhafiz M Abdelkhalek HM . Intravenous thrombolysis before thrombectomy in acute ischemic stroke: a dual Centre retrospective cohort study. Sci Rep. (2022) 12:21071. doi: 10.1038/s41598-022-25696-z,

28.

Faizy TD Mlynash M Marks MP Christensen S Kabiri R Kuraitis GM et al . Intravenous tPA (tissue-type plasminogen activator) correlates with favorable venous outflow profiles in acute ischemic stroke. Stroke. (2022) 53:3145–52. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.122.038560,

29.

Fang M Xu C Ma L Sun Y Zhou X Deng J et al . No sex difference was found in the safety and efficacy of intravenous alteplase before endovascular therapy. Front Neurol. (2022) 13:989166. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2022.989166,

30.

Geng C Li SD Zhang DD Ma L Liu GW Jiao LQ et al . Endovascular thrombectomy versus bridging thrombolysis: real-world efficacy and safety analysis based on a nationwide registry study. J Am Heart Assoc. (2021) 10:e018003. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.120.018003,

31.

Gong L Zheng X Feng L Zhang X Dong Q Zhou X et al . Bridging therapy versus direct mechanical thrombectomy in patients with acute ischemic stroke due to middle cerebral artery occlusion: a clinical- histological analysis of retrieved thrombi. Cell Transplant. (2019) 28:684–90. doi: 10.1177/0963689718823206,

32.

Guedin P Larcher A Decroix JP Labreuche J Dreyfus JF Evrard S et al . Prior IV thrombolysis facilitates mechanical thrombectomy in acute ischemic stroke. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis. (2015) 24:952–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jstrokecerebrovasdis.2014.12.015,

33.

Guo M Yue C Yang J Hu J Guo C Peng Z et al . Thrombectomy alone versus intravenous thrombolysis before thrombectomy for acute basilar artery occlusion. J Neurointerv Surg. (2024) 16:794–800. doi: 10.1136/jnis-2023-020361,

34.

Huu An N Dang Luu V Duy Ton M Anh Tuan T Quang Anh N Hoang Kien L et al . Thrombectomy alone versus bridging therapy in acute ischemic stroke: preliminary results of an experimental trial. Clin Ter. (2022) 173:107–14. doi: 10.7417/CT.2022.2403,

35.

Kaesmacher J Kleine JF . Bridging therapy with i. v. rtPA in MCA occlusion prior to endovascular thrombectomy: a double-edged sword?Clin Neuroradiol. (2018) 28:81–9. doi: 10.1007/s00062-016-0533-0,

36.

Kandregula S Savardekar AR Sharma P McLarty J Kosty J Trosclair K et al . Direct thrombectomy versus bridging thrombolysis with mechanical thrombectomy in middle cerebral artery stroke: a real-world analysis through National Inpatient Sample data. Neurosurg Focus. (2021) 51:E4. doi: 10.3171/2021.4.FOCUS21132,

37.

Kurminas M Berūkštis A Misonis N Blank K Tamošiūnas AE Jatužis D . Intravenous r-tPA dose influence on outcome after middle cerebral artery ischemic stroke treatment by mechanical thrombectomy. Medicina (Kaunas). (2020) 56. doi: 10.3390/medicina56070357,

38.

Leker RR Cohen JE Tanne D Orion D Telman G Raphaeli G et al . Direct thrombectomy versus bridging for patients with emergent large-vessel occlusions. Interv Neurol. (2018) 7:403–12. doi: 10.1159/000489575,

39.

Maier IL Behme D Schnieder M Tsogkas I Schregel K Kleinknecht A et al . Bridging-therapy with intravenous recombinant tissue plasminogen activator improves functional outcome in patients with endovascular treatment in acute stroke. J Neurol Sci. (2017) 372:300–4. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2016.12.001,

40.

Molad J Hallevi H Seyman E Ben-Assayag E Jonas-Kimchi T Sadeh U et al . The pivotal role of timing of intravenous thrombolysis bridging treatment prior to endovascular thrombectomy. Ther Adv Neurol Disord. (2023) 16:17562864231216637. doi: 10.1177/17562864231216637,

41.

Park HK Chung JW Hong JH Jang MU Noh HD Park JM et al . Preceding intravenous thrombolysis in patients receiving endovascular therapy. Cerebrovasc Dis. (2017) 44:51–8. doi: 10.1159/000471492,

42.

Seetge J Cséke B Karádi ZN Bosnyák E Szapáry L . Bridging the gap: improving acute ischemic stroke outcomes with intravenous thrombolysis prior to mechanical thrombectomy. Neurol Int. (2024) 16:1189–202. doi: 10.3390/neurolint16060090,

43.

Smith EE Zerna C Solomon N Matsouaka R Mac Grory B Saver JL et al . Outcomes after endovascular thrombectomy with or without alteplase in routine clinical practice. JAMA Neurol. (2022) 79:768–76. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2022.1413,

44.

Smith WS . Safety of mechanical thrombectomy and intravenous tissue plasminogen activator in acute ischemic stroke. Results of the multi mechanical Embolus removal in cerebral ischemia (MERCI) trial, part I. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. (2006) 27:1177–82.

45.

Tong X Wang Y Fiehler J Bauer CT Jia B Zhang X et al . Thrombectomy versus combined thrombolysis and thrombectomy in patients with acute stroke: a matched-control study. Stroke. (2021) 52:1589–600. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.120.031599,

46.

Wang H Zi W Hao Y Yang D Shi Z Lin M et al . Direct endovascular treatment: an alternative for bridging therapy in anterior circulation large-vessel occlusion stroke. Eur J Neurol. (2017) 24:935–43. doi: 10.1111/ene.13311,

47.

Weber R Nordmeyer H Hadisurya J Heddier M Stauder M Stracke P et al . Comparison of outcome and interventional complication rate in patients with acute stroke treated with mechanical thrombectomy with and without bridging thrombolysis. J Neurointerv Surg. (2017) 9:229–33. doi: 10.1136/neurintsurg-2015-012236,

48.

Podlasek A Dhillon PS Butt W Grunwald IQ England TJ . Direct mechanical thrombectomy without intravenous thrombolysis versus bridging therapy for acute ischemic stroke: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Int J Stroke. (2021) 16:621–31. doi: 10.1177/17474930211021353,

49.

Katsanos AH Malhotra K Goyal N Arthur A Schellinger PD Köhrmann M et al . Intravenous thrombolysis prior to mechanical thrombectomy in large vessel occlusions. Ann Neurol. (2019) 86:395–406. doi: 10.1002/ana.25544,

50.

Campbell BCV Kappelhof M Fischer U . Role of intravenous thrombolytics prior to endovascular thrombectomy. Stroke. (2022) 53:2085–92. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.122.036929,

51.

Waller J Kaur P Tucker A Amer R Bae S Kogler A et al . The benefit of intravenous thrombolysis prior to mechanical thrombectomy within the therapeutic window for acute ischemic stroke. Clin Imaging. (2021) 79:3–7. doi: 10.1016/j.clinimag.2021.03.020,

52.

Tsivgoulis G Katsanos AH Schellinger PD Köhrmann M Varelas P Magoufis G et al . Successful reperfusion with intravenous thrombolysis preceding mechanical thrombectomy in large-vessel occlusions. Stroke. (2018) 49:232–5. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.117.019261,

53.

Deng G Chu Y-h Xiao J Shang K Zhou L-Q Qin C et al . Risk factors, pathophysiologic mechanisms, and potential treatment strategies of futile recanalization after endovascular therapy in acute ischemic stroke. Aging Dis. (2023) 14:2096–112. doi: 10.14336/AD.2023.0321-1,

54.

Das S Goldstein ED De Havenon A Abbasi M Nguyen TN Aguiar de Sousa D et al . Composition, treatment, and outcomes by radiologically defined thrombus characteristics in acute ischemic stroke. Stroke. (2023) 54:1685–94. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.122.038563,

55.

Jia M Jin F Li S Ren C Ruchi M Ding Y et al . No-reflow after stroke reperfusion therapy: An emerging phenomenon to be explored. CNS Neurosci Ther. (2024) 30:e14631. doi: 10.1111/cns.14631,

56.

Da Ros V Scaggiante J Pitocchi F Sallustio F Lattanzi S Umana GE et al . Mechanical thrombectomy in acute ischemic stroke with tandem occlusions: impact of extracranial carotid lesion etiology on endovascular management and outcome. Neurosurgical focus. (2021) 51:E6.

Summary

Keywords

acute ischemic stroke, bridging therapy, intravenous thrombolysis, mechanical thrombectomy, meta-analysis

Citation

Huang Y, Wang X, Sheng G and Miao X (2026) Bridging therapy versus direct mechanical thrombectomy in acute ischemic stroke: an updated meta-analysis of real-world evidence. Front. Med. 12:1731626. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2025.1731626

Received

24 October 2025

Revised

30 November 2025

Accepted

04 December 2025

Published

09 January 2026

Volume

12 - 2025

Edited by

Abdelaziz Abdelaal, Harvard Medical School, United States

Reviewed by

Yingkun He, Henan Provincial People’s Hospital, China

Dandan Geng, First Affiliated Hospital of Chongqing Medical University, China

Updates

Copyright

© 2026 Huang, Wang, Sheng and Miao.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Xujian Miao, langzuyinyue@163.com

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.