Abstract

Introduction:

The case reports a rare case of a patient diagnosed with unicentric Castleman disease (UCD) with paraneoplastic pemphigus (PNP). According to the literature, surgery is considered the first-line therapy for such patient. Therefore, we collected and analyzed preoperative and postoperative data to evaluate the surgical outcome and prognosis.

Case presentation:

A 28-year-old female patient had manifested erosions on oral mucosa and fingers for several months. Contrast-enhanced CT imaging revealed an abdominal mass. Histopathology of the lesions revealed lichenoid interface dermatitis. Direct immunofluorescence examination of the skin revealed a reticular deposition of IgG and C3 in the intercellular spaces of the epidermis. According to the latest diagnostic criteria, she was diagnosed with PNP. She underwent surgery at our hospital, during which the mass was completely resected. Postoperative pathology confirmed the mass as UCD, specifically of the hyaline vascular type. Following the surgery, the patient was concurrently treated with a tapering regimen of oral glucocorticoids. After 2 years of follow-up, there was no recurrence of the oral or hand erosions, and a repeat abdominal CT scan showed no evidence of mass recurrence.

Conclusion:

Complete resection is the first-line therapy for UCD with PNP. Early and correct diagnosis is crucial for patient prognosis.

Background

Castleman disease (CD) is a heterogeneous disorder primarily characterized by lymph node enlargement, first described by Castleman in 1954 (1). Epidemiological data indicate that the incidence rate of CD is approximately 22–25 per million person-years (2). CD can involve lymph nodes throughout the body. Based on the distribution of affected lymph nodes, it is classified into unicentric Castleman disease (UCD) and multicentric Castleman disease (MCD) (3, 4). The clinical manifestations of these two subtypes differ significantly. Patients with UCD typically present with an enlarged single lymph node or a solitary group of lymph nodes and are usually asymptomatic (3). After complete resection, the prognosis of patients is usually favorable and the recurrence rate is low. The 5-year survival rate for UCD patients after complete resection exceeds 90% (5–7).

Paraneoplastic pemphigus (PNP) is a rare autoimmune disorder associated with underlying neoplasm. PNP is frequently associated with lymphoproliferative neoplasms. The majority of the neoplasms reported in PNP include non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma, chronic lymphocytic leukemia, CD, and thymoma (8). PNP is clinically characterized by painful stomatitis and polymorphous cutaneous lesions. Patients with PNP can present with oral lesions, other mucosal lesions, skin lesions and pulmonary manifestations (9). Oral lesions are the earliest manifestation and are present in almost all PNP patients (10–12). CD is the most common neoplasm in PNP patients with oral manifestations (10). Oral manifestations can range from blisters, erosions to diffuse painful stomatitis involving the lips, tongue, cheeks and gingivae or the entire oral cavity (13, 14). Painful ulcers on the tongue and vermillion border on the lips are also obvious clinical features (14). Moreover, nasal mucosa, pharynx, larynx or esophagus can be involved, causing odynophagia and dysphagia, seriously influence the quality of life, nutrition status of patients (8, 15, 16). Although repeated course of systematic corticosteroids may relieve the oral pain, lesions may recur and worsen (10, 11).

The progression of untreated PNP may lead to bronchiolitis obliterans (BO), which is life threatening and associated with poor prognosis (12, 17). Since immunosuppressive treatment alone is ineffective without treating the underlying neoplasm, complete surgical removal of the tumor should be performed as soon as possible, ideally before the onset of BO (18). PNP can progress even after the original malignancy is removed (9). However, PNP with CD shows better outcomes after removing the mass in surgery. Once the mass is removed, skin and mucosa erosions typically subside gradually (19).

Case presentation

A 28-year-old female patient presented with the erosions of multiple fingers and extensive painful oral erosions for several months. Treatment with oral hydroxychloroquine and prednisone, along with topical triamcinolone acetonide, yielded no significant improvement, prompting her referral to our institution for further evaluation. The patient denied fever, dyspnea abdominal distension, diarrhea, dyspnea or related symptoms of respiratory system. However, the worsening oral pain impaired the daily eating and leads to a weight loss of 7.5 kg.

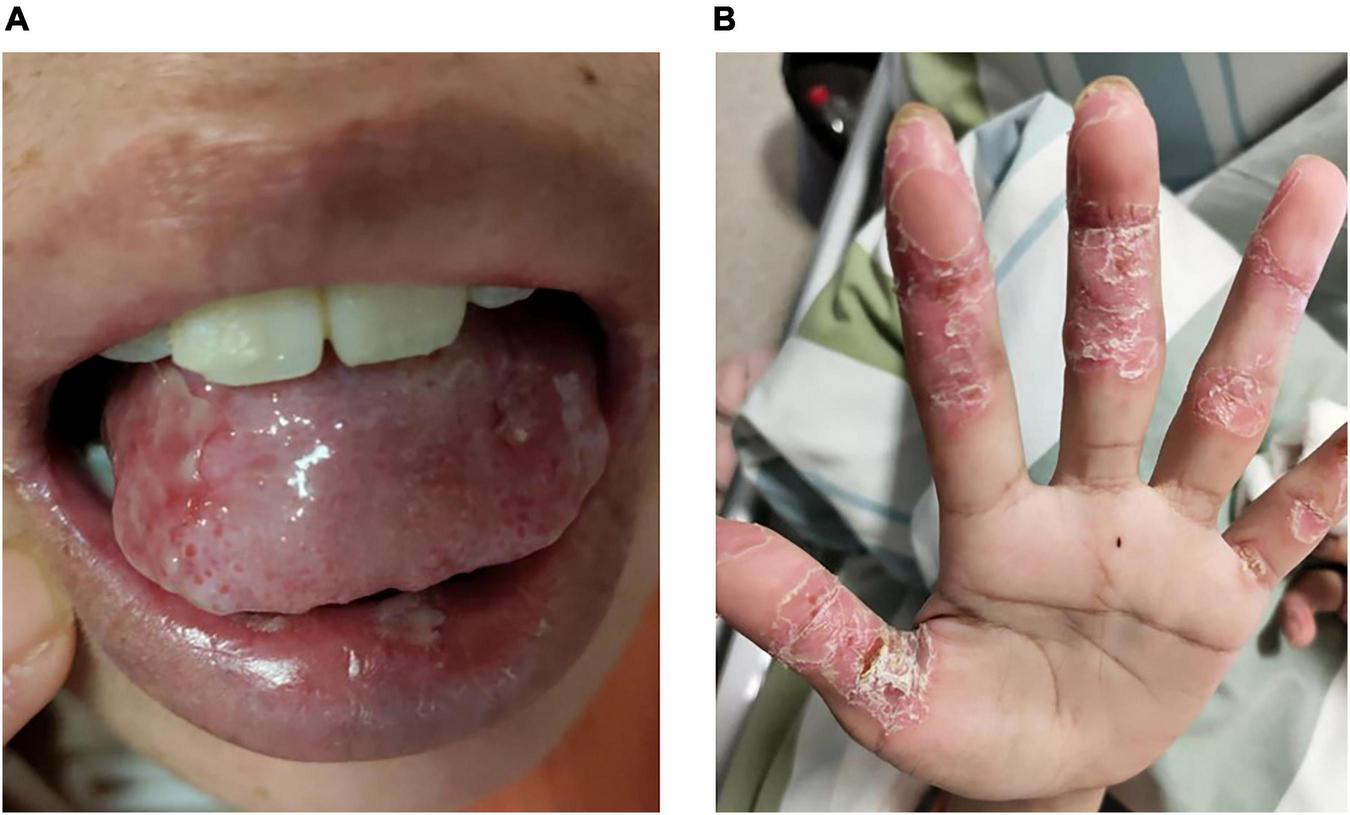

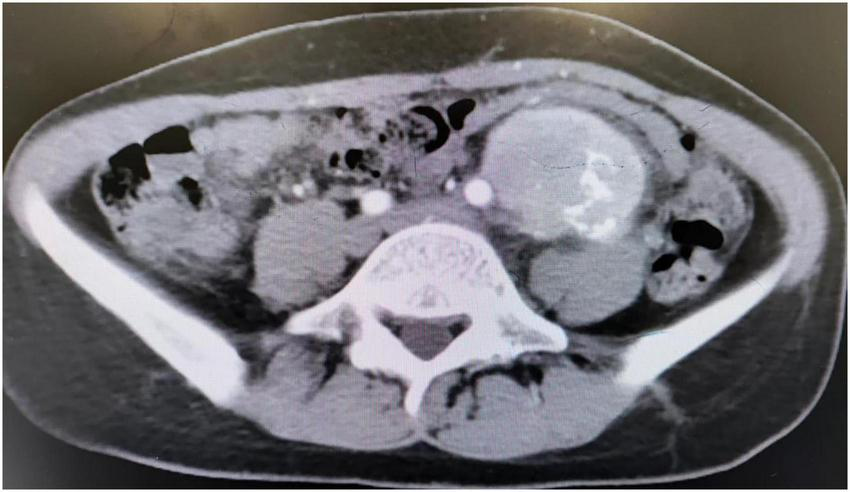

Multiple erosions were observed on the oral mucosa and tongue (Figure 1A), as well as on the fingers of both hands (Figure 1B). The physical examination of abdomen revealed no abnormal results. The abdomen was flat with no scars. There was no tenderness or rebound tenderness throughout the abdomen. A firm mass was palpable in the left lower quadrant, with a clear boundary from the surrounding tissues. A biopsy of a finger erosion was consistent with lichen planus. A contrast-enhanced abdominal CT scan revealed a solitary mass in the left lower abdomen measuring 5.4 cm × 5.1 cm × 9.2 cm, with a clear boundary from the surrounding tissues (Figure 2). The patient’s biochemical profile, full blood count, serum antibodies (IgA, IgG, and C3) and coagulation profile were normal with no significant abnormalities detected. The result of the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) screening test was also negative. One of the tumor markers was abnormal, the squamous cell carcinoma-associated antigen level was significantly elevated at >70 ng/ml (normal range: <1.5 ng/ml). Direct immunofluorescence examination of the skin revealed a reticular deposition of IgG and C3 in the intercellular spaces of the epidermis. Histopathology of the lesions revealed lichenoid interface dermatitis. According to the diagnostic criteria established by the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology in 2023, she was diagnosed with PNP (12).

FIGURE 1

Erosions on the (A) tongue and (B) fingers.

FIGURE 2

CT scan showed an abdominal mass.

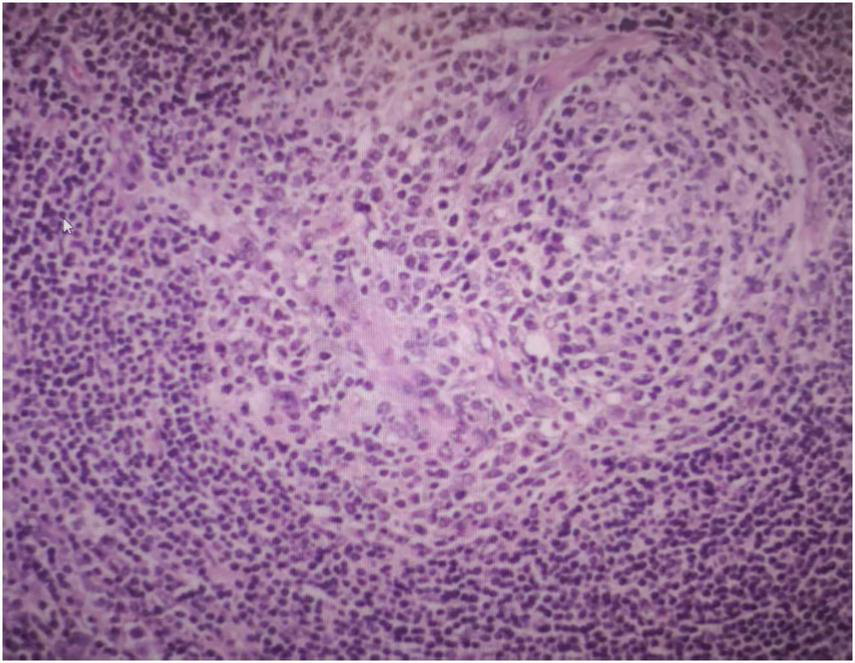

Three days after being admitted to hospital, the patient subsequently underwent surgery to completely resect the retroperitoneal mass under general anesthesia. A large mass, approximately 10 cm × 6 cm in size, was detected in the left retroperitoneum. It was well-defined and showed no infiltration into surrounding tissues, allowing for complete excision. Postoperative pathological examination confirmed the diagnosis of UCD, hyaline-vascular type (Figure 3). Immunohistochemical staining results were as follows:CD20 (lymphoid follicle cells +), CD79a (lymphoid follicle cells +), CD3 (interfollicular area cells +), CD5 (interfollicular area cells +), CD21 (follicular dendritic network +), Bcl-2 (follicular dendritic network and surrounding lymphocytes +), CD10 (focal +), CD138 (focal +), Cyclin D1 (scattered +), CD30 (individual cells +), Ki-67 (+).

FIGURE 3

Postoperative pathological examination showed the mass is UCD, hyaline-vascular type.

The patient recovered well postoperatively and received oral glucocorticoid therapy, with the dosage gradually tapered until discontinuation. At the 1-year follow-up, the oral erosions and hand erosions had healed. After 2 years of follow-up, there was no recurrence of the oral erosions or hand erosions, and an abdominal CT scan showed no evidence of recurrence.

Discussion and literature review

Unicentric Castleman disease is a rare disease characterized by single enlarged lymph node or several enlarged lymph nodes within a single lymph node station (20). According to a systematic review of 404 patients, UCD is more likely to be detected in the mediastinum (29%), neck (23%), abdomen (21%), and retroperitoneum (17%), but it can also be detected in any lymph node throughout the body (7). UCD is usually asymptomatic and mostly detected due to compression of adjacent structures (e.g., airways, blood vessels, nerves, ureters) or incidentally through imaging examinations (20–22). CT scan of the of the neck, chest, abdomen, and pelvis can clearly show the enlarged lymph nodes. CT–positron emission tomography scanning can also help locate the lymph nodes by monitoring the metabolic activity (20, 23, 24). Laboratory tests are usually normal, but anemia, hypergammaglobulinemia and elevated sedimentation rate may be present (22).

Biopsy is the gold standard for the diagnosis of CD (20). An excisional biopsy instead of core or fine-needle aspirate is needed to get the sample of the enlarged lymph node (3, 20). Based on histopathological features, CD is primarily classified into the hyaline-vascular (HV) type, plasma cell (PC) type, and mixed type (20). UCD is predominantly characterized by the HV histopathologic type, which is observed in 70%–90% of UCD patients. The plasma cell or mixed type is identified in approximately 10%–30% of UCD cases (22). Those patients can present with symptoms similar to those of MCD, such as sweats, fever, anorexia, or weight loss (20, 25).

In the present case, the patient reported no abdominal discomfort. Despite persistent growth, the mass did not compress any adjacent organs or tissues to become clinically apparent. Moreover, UCD patients, particularly those with the hyaline-vascular type, are frequently asymptomatic, making the mass difficult to detect (20, 22, 26). In preoperative examinations, the biochemical profile, full blood count, serum antibodies, and coagulation profile were all normal; however, the squamous cell carcinoma-associated antigen level was elevated, while in another case repot carcinoembryonic antigen is elevated (27). These largely normal findings initially led to a misdiagnosis of isolated mucosal lesions, resulting in a delay of several months before the correct diagnosis was established. Approximately sixty percent of patients present with oral manifestations prior to the diagnosis of an underlying neoplasm, only a small percentage of patients had oral manifestations concurrently with the diagnosis of neoplasm (10). When associated with PNP, UCD patients can present with severe stomatitis, frequent painful ulcers on the tongue and erosions on the lips that extend to the vermillion border of the lips (14). These lesions are refractory to prolonged symptomatic therapy, which is a hallmark of PNP (10, 11). Therefore, for such patients, it is crucial to consider a possible diagnosis of paraneoplastic pemphigus. If PNP is suspected, CT imaging serves as a valuable tool for identifying potentially enlarged lymph nodes or tumors to achieve an early diagnosis (8, 9).

Greater clinical attention is warranted for UCD patients with PNP (3). Unlike those with isolated UCD, these patients face an increased risk of respiratory failure and pulmonary infection, which are the leading causes of mortality (12, 17). Management should address not only the symptomatic control of PNP-associated mucosal lesions but also perioperative administration of high-dose intravenous immunoglobulin to prevent pulmonary complications, particularly BO (28). Our patient received both oral glucocorticoid therapy and intravenous immunoglobulin perioperatively. Additionally, a chest CT scan was performed to screen for any pulmonary involvement.

Complete surgical resection is the primary recommended therapy for patients with UCD and PNP (3, 20). Surgery serves to remove the mass, alleviate potential symptoms caused by compression of adjacent tissues, improve oral lesions, and halt the progression of PNP (9, 19). Preoperative evaluation should focus on assessing the feasibility of complete resection and weighing the surgical risks against benefits (20). If complete resection is not feasible, partial resection may be considered. Following partial resection, rituximab in combination with corticosteroids can help reduce the size of the residual mass, potentially meeting the criteria for a subsequent complete resection (3). Patients may benefit from a second surgery for complete resection if reevaluation after adjuvant drug therapy deems them suitable. The vast majority of UCD patients are cured after complete resection, with recurrence being rare (29–31). According to global multicenter reports, the 5-year survival rate for UCD patients after complete resection exceeds 90% (5–7). A 20-year French study of 273 CD patients reported a 2-year survival rate of 98.1% for UCD patients (26). Similarly, a retrospective study from China reported 1- and 5-year survival rates of 98.5% and 97.1%, respectively, for UCD patients (5). Postoperatively, treatment with oral systemic corticosteroids, topical treatment of lesions and annual follow-up is recommended (3, 12). The follow-up includes CT scan, complete blood count, lactate dehydrogenase, as well as assessments of liver and renal function, electrolytes, albumin, CRP, and quantitative immunoglobulins (3).

For patients with unresectable UCD after other therapies have been considered or attempted, radiation therapy may be an option, though it is often unsuitable for younger patients (32). A recent publication from the Mayo Clinic suggested that cryoablation could be a potential treatment for unresectable UCD (33). For patients assessed preoperatively as having a high risk of hemorrhage, angiographic embolization may be performed (3).

Overall, patients with PNP accompanied by CD have a relatively favorable prognosis (9, 18). Nevertheless, some patients may still experience pulmonary involvement, which can lead to respiratory failure or even death (19). The prognosis of PNP is generally poor. When associated with malignancy, the mortality rate approaches 90% (28). With early and complete surgical resection, such patients can achieve long-term remission, as evidenced by multi-year follow-up (19). In our case, the patient underwent complete resection, and two-year follow-up has shown a favorable prognosis without recurrence.

Conclusion

Unicentric Castleman disease associated with PNP represents a complicated clinical scenario, in which early diagnosis is crucial to intervene before the onset of BO and respiratory symptoms. Clinicians should consider the possible diagnosis of PNP in patients whose oral lesions show no improvement after symptomatic treatment. Complete surgical resection remains the first-line recommended therapy for these patients. Overall, with early recognition and timely operative management, the prognosis is generally favorable.

Statements

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in this article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by Nanjing First Hospital affiliated to Nanjing Medical University. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. Written informed consent for participation was not required from the participants or the participants’ legal guardians/next of kin in accordance with the national legislation and institutional requirements. Written informed consent was obtained from the individual(s) for the publication of any potentially identifiable images or data included in this article. Written informed consent was obtained from the participant/patient(s) for the publication of this case report.

Author contributions

G-tL: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing, Investigation, Methodology, Validation. Y-hZ: Methodology, Supervision, Writing – review & editing. J-lZ: Methodology, Writing – review & editing. Z-yZ: Methodology, Writing – review & editing. Z-jL: Supervision, Methodology, Validation, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declared that financial support was not received for this work and/or its publication.

Conflict of interest

The author(s) declared that this work was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declared that generative AI was not used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1.

Castleman B Towne VW . Case records of the Massachusetts General Hospital; weekly clinicopathological exercises. Case No. 40351.N Engl J Med. (1954) 251:396–400. 10.1056/NEJM195409022511008

2.

Simpson D . Epidemiology of Castleman disease.Hematol Oncol Clin North Am. (2018) 32:1–10. 10.1016/j.hoc.2017.09.001

3.

van Rhee F Oksenhendler E Srkalovic G Voorhees P Lim M Dispenzieri A et al International evidence-based consensus diagnostic and treatment guidelines for unicentric Castleman disease. Blood Adv. (2020) 4:6039–50. 10.1182/bloodadvances.2020003334

4.

Fajgenbaum DC Uldrick TS Bagg A Frank D Wu D Srkalovic G et al International, evidence-based consensus diagnostic criteria for HHV-8-negative/idiopathic multicentric Castleman disease. Blood. (2017) 129:1646–57. 10.1182/blood-2016-10-746933

5.

Zhang L Li Z Cao X Feng J Zhong D Wang S et al Clinical spectrum and survival analysis of 145 cases of HIV-negative Castleman’s disease: renal function is an important prognostic factor. Sci Rep. (2016) 6:23831. 10.1038/srep23831

6.

Dispenzieri A Armitage JO Loe MJ Geyer SM Allred J Camoriano JK et al The clinical spectrum of Castleman’s disease. Am J Hematol. (2012) 87:997–1002. 10.1002/ajh.23291

7.

Talat N Belgaumkar AP Schulte KM . Surgery in Castleman’s disease: a systematic review of 404 published cases.Ann Surg. (2012) 255:677–84. 10.1097/SLA.0b013e318249dcdc

8.

Anhalt GJ Kim SC Stanley JR Korman NJ Jabs DA Kory M et al Paraneoplastic pemphigus. an autoimmune mucocutaneous disease associated with neoplasia. N Engl J Med. (1990) 323:1729–35. 10.1056/NEJM199012203232503

9.

Paolino G Didona D Magliulo G Iannella G Didona B Mercuri SR et al Paraneoplastic pemphigus: insight into the autoimmune pathogenesis, clinical features and therapy. Int J Mol Sci. (2017) 18:2532. 10.3390/ijms18122532

10.

Messina S De Falco D Petruzzi M . Oral manifestations in paraneoplastic syndromes: a systematic review and meta-analysis.Oral Dis. (2025) 31:81–8. 10.1111/odi.15158

11.

Decaux J Ferreira I Van Eeckhout P Dachelet C Magremanne M . Buccal paraneoplastic pemphigus multi-resistant: case report and review of diagnostic and therapeutic strategies.J Stomatol Oral Maxillofac Surg. (2018) 119:506–9. 10.1016/j.jormas.2018.06.003

12.

Antiga E Bech R Maglie R Genovese G Borradori L Bockle B et al S2k guidelines on the management of paraneoplastic pemphigus/paraneoplastic autoimmune multiorgan syndrome initiated by the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology (EADV). J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. (2023) 37:1118–34. 10.1111/jdv.18931

13.

Rashid H Lamberts A Diercks GFH Pas HH Meijer JM Bolling MC et al Oral lesions in autoimmune Bullous diseases: an overview of clinical characteristics and diagnostic algorithm. Am J Clin Dermatol. (2019) 20:847–61. 10.1007/s40257-019-00461-7

14.

Schmidt E Kasperkiewicz M Joly P . Pemphigus.Lancet. (2019) 394:882–94. 10.1016/S0140-6736(19)31778-7

15.

Gissi DB Bernardi A D’Andrea M Montebugnoli L . Paraneoplastic pemphigus presenting with a single oral lesion.BMJ Case Rep. (2013) 2013:bcr2012007771. 10.1136/bcr-2012-007771

16.

Suliman NM Johannessen AC Ali RW Salman H Astrøm AN . Influence of oral mucosal lesions and oral symptoms on oral health related quality of life in dermatological patients: a cross sectional study in Sudan.BMC Oral Health. (2012) 12:19–30. 10.1186/1472-6831-12-19

17.

Ohzono A Sogame R Li X Teye K Tsuchisaka A Numata S et al Clinical and immunological findings in 104 cases of paraneoplastic pemphigus. Br J Dermatol. (2015) 173:1447–52. 10.1111/bjd.14162

18.

Wang J Zhu X Li R Tu P Wang R Zhang L et al Paraneoplastic pemphigus associated with Castleman tumor: a commonly reported subtype of paraneoplastic pemphigus in China. Arch Dermatol. (2005) 141:1285–93. 10.1001/archderm.141.10.1285

19.

Zhang J Qiao QL Chen XX Liu P Qiu JX Zhao H et al Improved outcomes after complete resection of underlying tumors for patients with paraneoplastic pemphigus: a single-center experience of 22 cases. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. (2011) 137:229–34. 10.1007/s00432-010-0874-z

20.

Carbone A Borok M Damania B Gloghini A Polizzotto MN Jayanthan RK et al Castleman disease. Nat Rev Dis Primers. (2021) 7:84. 10.1038/s41572-021-00317-7

21.

Boutboul D Fadlallah J Chawki S Fieschi C Malphettes M Dossier A et al Treatment and outcome of unicentric Castleman disease: a retrospective analysis of 71 cases. Br J Haematol. (2019) 186:269–73. 10.1111/bjh.15921

22.

Dispenzieri A Fajgenbaum DC . Overview of Castleman disease.Blood. (2020) 135:1353–64. 10.1182/blood.2019000931

23.

Hill AJ Tirumani SH Rosenthal MH Shinagare AB Carrasco RD Munshi NC et al Multimodality imaging and clinical features in Castleman disease: single institute experience in 30 patients. Br J Radiol. (2015) 88:20140670. 10.1259/bjr.20140670

24.

Polizzotto MN Millo C Uldrick TS Aleman K Whatley M Wyvill KM et al 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography in kaposi sarcoma herpesvirus-associated multicentric castleman disease: correlation with activity, severity, inflammatory and virologic parameters. J Infect Dis. (2015) 212:1250–60. 10.1093/infdis/jiv204

25.

Zhang MY Jia MN Chen J Feng J Cao XX Zhou DB et al UCD with MCD-like inflammatory state: surgical excision is highly effective. Blood Adv. (2021) 5:122–8. 10.1182/bloodadvances.2020003607

26.

Oksenhendler E Boutboul D Fajgenbaum D Mirouse A Fieschi C Malphettes M et al The full spectrum of Castleman disease: 273 patients studied over 20 years. Br J Haematol. (2018) 180:206–16. 10.1111/bjh.15019

27.

El-Enany G El-Mofty M Abdel-Halim MRE Dermpath D Nagui N Nada H et al Postpartum Castleman disease presenting as paraneoplastic pemphigus: a case report. Int J Dermatol. (2023) 62:e111–3. 10.1111/ijd.16505

28.

Yong AA Tey HL . Paraneoplastic pemphigus.Australas J Dermatol. (2013) 54:241–50. 10.1111/j.1440-0960.2012.00921.x

29.

Ren N Ding L Jia E Xue J . Recurrence in unicentric castleman’s disease postoperatively: a case report and literature review.BMC Surg. (2018) 18:1. 10.1186/s12893-017-0334-7

30.

He X Wang Q Wu Y Hu J Wang D Qi B et al Comprehensive analysis of 225 Castleman’s diseases in the oral maxillofacial and neck region: a rare disease revisited. Clin Oral Investig. (2018) 22:1285–95. 10.1007/s00784-017-2232-x

31.

Zhou N Huang CW Huang C Liao W . The characterization and management of Castleman’s disease.J Int Med Res. (2012) 40:1580–8. 10.1177/147323001204000438

32.

Chan KL Lade S Prince HM Harrison SJ . Update and new approaches in the treatment of Castleman disease.J Blood Med. (2016) 7:145–58. 10.2147/JBM.S60514

33.

Nishimura Y Atwell T Callstrom M McGarrah P Howard M King RL et al Cryoablation for unresectable unicentric Castleman disease. Am J Hematol. (2025) 100:149–51. 10.1002/ajh.27507

Summary

Keywords

case report, paraneoplastic pemphigus, prognosis, surgery, unicentric Castleman disease

Citation

Lv G-t, Zhao Y-h, Zhao J-l, Zheng Z-y and Liu Z-j (2026) Unicentric Castleman disease with paraneoplastic pemphigus in a young woman: a case report. Front. Med. 12:1749601. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2025.1749601

Received

19 November 2025

Revised

26 December 2025

Accepted

26 December 2025

Published

16 January 2026

Volume

12 - 2025

Edited by

Jinchao Chen, Zhejiang Cancer Hospital, China

Reviewed by

Nienie Qi, The Affiliated Hospital of Xuzhou Medical University, China

Domenico De Falco, University of Bari Aldo Moro, Italy

Updates

Copyright

© 2026 Lv, Zhao, Zhao, Zheng and Liu.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Zi-jun Liu, liuzijundoctor@sina.com

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.