- 1Department of Pediatrics, West China Second University Hospital of Sichuan University, Chengdu, China

- 2Key Laboratory of Birth Defects and Related Diseases of Women and Children, Ministry of Education, Chengdu, China

Background: Salmonella typically causes gastroenteritis and rarely leads to invasive infections.

Case presentation: A 14-year-old boy, without a definitive history of an unsanitary diet or open wounds, was residing in an area with a high prevalence of tuberculosis. His primary symptoms included fever, cough, lumbar pain, and weight loss. The initial pathogen test was negative. Medical imaging revealed pulmonary nodules, intervertebral space narrowing, vertebral bone destruction, and a psoas muscle abscess. Empirical antibiotic therapy and diagnostic anti-tuberculosis treatment yielded poor results. Ultimately, pathogen testing of the surgically excised lesion identified Salmonella Dublin. Antimicrobial therapy guided by susceptibility testing yielded favorable outcomes.

Conclusion: Empirical therapy is often necessary during the initial phase of treatment. However, clinicians should consider uncommon conditions and employ appropriate approaches to obtain pathogen-specific test results, which can guide targeted therapeutic strategies when the anticipated clinical outcome is suboptimal.

Background

Salmonella is one of the important causes of human foodborne disease. Non-typhoidal Salmonella refers to serotypes other than Salmonella typhi and Salmonella paratyphi. These non-typhoidal serotypes can cause a variety of clinical infections in humans. Most cases of non-typhoidal Salmonella infections typically present as gastroenteritis. However, in some patients, non-typhoidal Salmonella can cause invasive infections, including bacteremia, meningitis, and osteomyelitis (1). The incidence of invasive non-typhoidal Salmonella infections has been estimated at 44.8 per 100,000 persons per year (2). Here, we present a case of spondylitis caused by Salmonella Dublin, highlighting its challenging diagnostic and therapeutic course.

Case presentation

A 14-year-old boy was admitted to the pediatric infectious disease department due to “16 days of waist pain and 10 days of fever,” accompanied only by a mild cough. The patient received all standard immunizations, including hepatitis B vaccine, bacille Calmette-Guerin (BCG) vaccine, diphtheria-tetanus-pertussis vaccine, and polio vaccine. He had a history of recurrent atopic dermatitis in early childhood and no history of animal contact, a definitive unsanitary diet, travel to epidemic areas, or inherited disease. From the onset of symptoms to admission, he had lost 4.5 kg.

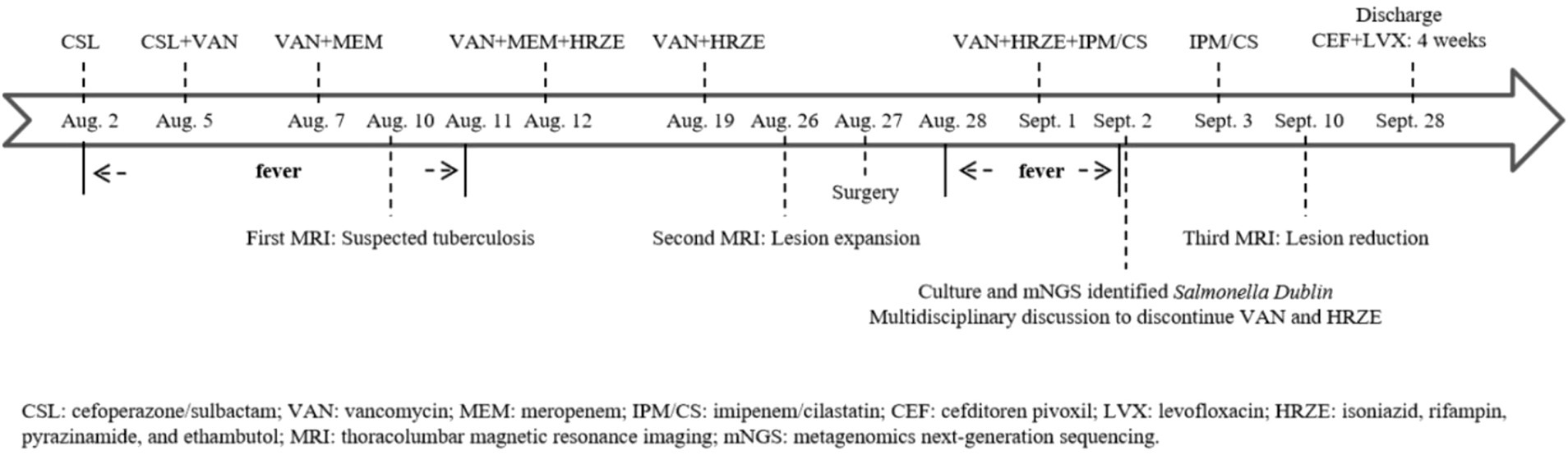

Physical examination revealed tenderness in the left upper quadrant and thoracolumbar spine. Laboratory tests showed the following: Complete blood count (CBC): white blood cell (WBC) 5.3 × 10^9/L, neutrophil (N) 73.2%, hemoglobin (HGB) 134 g/L, and platelet (PLT) 237 × 10^9/L; C-reactive protein (CRP) 41.9 mg/L; and erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) 38 mm/h. He received empirical treatment with cefoperazone/sulbactam, but there was no improvement. We adjusted the antibiotic regimen from targeting Gram-positive resistant bacteria to include Gram-negative resistant bacteria. After administering vancomycin combined with meropenem for five days, his temperature returned to normal.

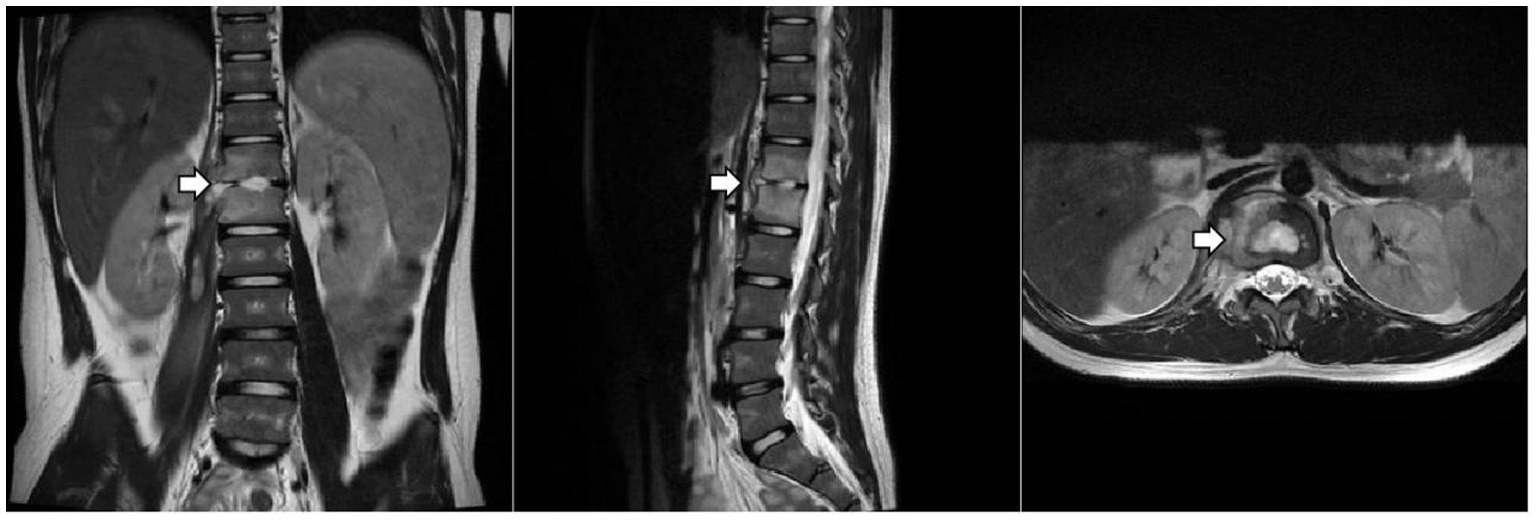

The patient underwent a series of tests to identify the cause of his illness, all of which were negative. These included urine and blood cultures, Epstein–Barr virus (EBV) DNA and antibody tests, serum 1,3-β-D-glucan and galactomannan tests, tuberculin skin test (TST), interferon-gamma release assay (IGRA), cryptococcus neoformans antigen test, serologic markers for hepatitis B, HIV antibody test, Treponema Pallidum antibody test, blood metagenomic next-generation sequencing (mNGS), and bone marrow culture. His serum immunoglobulin levels were normal, as were the counts and percentages of B, NK, and T lymphocytes. Computed tomography of the chest and abdomen showed pulmonary nodules, liver and spleen enlargement, intervertebral space narrowing from T12 to L1 with nodules, and local compression of the adjacent vertebral body. Thoracolumbar magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) (Figure 1) showed bone marrow edema of T12-L1, local bone destruction of T12 and L1, narrowing of the corresponding intervertebral space, abnormal signals in the intervertebral disc, paraspinal soft tissue swelling, and a right psoas muscle abscess.

Figure 1. Thoracolumbar MRI. The arrow indicates localized bone destruction of the T12 and L1 vertebral bodies, narrowing of the intervertebral spaces, and abnormal signals within the intervertebral discs.

Tuberculosis was initially suspected based on imaging findings, symptoms (fever, cough, and weight loss), and epidemiological history (residence in an area with a high prevalence of tuberculosis). He received diagnostic anti-tuberculosis treatment with isoniazid, rifampin, pyrazinamide, and ethambutol (HRZE) after obtaining the consent of the guardian. He also underwent a bronchoscopy with bronchoalveolar lavage. The lavage fluid tested negative for acid-fast staining, Mycobacterium tuberculosis culture, and mNGS (tuberculosis).

Given the predominance of Gram-positive bacteria in osteoarticular infections, meropenem was discontinued first, after his temperature had remained normal for one week. After two weeks of anti-tuberculosis therapy, repeat thoracolumbar MRI (Figure 2) showed progression of the T12 and L1 lesions. He underwent surgical debridement, and the excised tissue was sent for pathological examination and pathogen identification. The patient developed a fever again after surgery. Laboratory tests showed the following: CBC: WBC 8.1 × 10^9/L, N% 76.4, HGB 125 g/L, and PLT 304 × 10^9/L; CRP 77.9 mg/L. Imipenem/cilastatin was added to cover resistant Gram-negative bacteria.

Culture and metagenomic next-generation sequencing (mNGS) of the surgically excised lesion identified Salmonella Dublin. Through multidisciplinary discussion involving the pediatric infectious diseases department, orthopedics department, radiology department, and pharmacy department, we concluded that the patient’s imaging findings were consistent with invasive non-typhoidal Salmonella infection and that the pathogen identified by both culture and mNGS was highly credible. Treatment with imipenem/cilastatin was continued according to antimicrobial sensitivity tests, while HRZE and vancomycin were discontinued. After two days of imipenem/cilastatin therapy, the patient had no further episodes of fever. After 10 days of imipenem/cilastatin therapy, follow-up thoracolumbar MRI (Figure 3) showed a reduction in bone marrow edema at T12-L1, as well as decreased lesions in the paraspinal soft tissue and the right psoas muscle. The patient was discharged after completing four weeks of treatment with imipenem/cilastatin and subsequently continued oral therapy with cefditoren pivoxil and levofloxacin for an additional four weeks. The patient attended follow-up visits at a local hospital. We learned from a phone call that he had recovered and resumed his studies (Timeline of the patient’s treatment see Figure 4).

Discussion and conclusion

Non-typhoidal Salmonella infections involving the bloodstream or other normally sterile sites are referred to as invasive infections, and several host factors are associated with their development. Age is a common risk factor for the development of invasive infections. In a global burden survey of invasive non-typhoidal Salmonella disease, children (<5 years) and older adults (≥70 years) represented the two peaks in the age distribution (3). This patient was not in a high-risk age group and did not have gastrointestinal symptoms, so non-typhoidal Salmonella infection was not considered initially.

Non-typhoidal Salmonella is transmitted via the fecal-oral route. Humans may become infected through the consumption of contaminated milk, eggs, meat, or fresh produce or through contact with infected animals (4–8). We repeatedly inquired about the patient’s epidemiological history but failed to identify a definitive source of infection. However, we suspect gastrointestinal transmission as the route of infection, given the patient’s consumption of potentially contaminated food. In addition, some patients with non-typhoidal Salmonella infection continue to shed the bacteria for an extended period of time (months or even years) (9). The patient may have acquired the infection through person-to-person transmission while living in a school dormitory (10).

Primary immunodeficiency diseases, such as chronic granulomatous disease (CGD) and Mendelian susceptibility to mycobacterial disease (MSMD), also increase host susceptibility to invasive non-typhoidal Salmonella infections. CGD is a primary immunodeficiency disease of phagocytes—including neutrophils, monocytes, macrophages, and eosinophils—caused by mutations in NADPH oxidase. This defect limits superoxide production, impairing the ability of phagocytes to kill pathogens intracellularly and leading to increased risk of infection dissemination (11). Patients with MSMD are susceptible to non-typhoidal Salmonella infection due to a primary immunodeficiency affecting the IL-12/IL-23-IFNγ pathway (12). Many studies have shown the importance of IFNγ-mediated immunity in the host control of non-typhoidal Salmonella infections (13–17). In addition, patients with diabetes mellitus, chronic corticosteroid use, hematologic neoplasms, autoimmune diseases, organ transplants, or immunosuppressive drug use are also susceptible to invasive non-typhoidal Salmonella infections (18–23). The patient did not have any of the aforementioned conditions, and genetic testing for immunodeficiency disease did not reveal any known pathogenic mutations (Supplementary Table 1).

The diagnostic and therapeutic course in this case was particularly challenging. Initially, clinical evidence strongly suggested a tuberculosis infection. However, anti-tuberculosis treatment failed to improve the condition. To establish a definitive diagnosis, surgical debridement was performed to obtain tissue samples for pathogen identification. Subsequent culture and mNGS conclusively identified Salmonella as the causative agent. Fortunately, guided by antimicrobial susceptibility testing, targeted antibiotic therapy achieved favorable clinical outcomes. Previous reports of similar cases have shown that bone and joint infections caused by non-typhoidal Salmonella are often difficult to diagnose in the early stages, with the pathogen frequently being identified only after surgical debridement (24–26).

In conclusion, accurate identification of the causative pathogen is critical for effective treatment. When diagnostic treatment proves ineffective, the possibility of a rare pathogen or an atypical pathogen should be considered, and appropriate clinical specimens should be collected to confirm the pathogen.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Ethics statement

Ethical approval was not required for the study involving human in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements because it is a retrospective study about a single case and we have the patient and his parents informed consensus.

Author contributions

SG: Writing – original draft. YZ: Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declared that financial support was received for this work and/or its publication. Funding was received for the publication of this article from the National Science and Technology Major Project of China (No. 2025ZD01907802).

Conflict of interest

The author(s) declared that this work was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declared that Generative AI was not used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fmed.2025.1754318/full#supplementary-material

References

1. Zaidi, E, Bachur, R, and Harper, M. Non-typhi Salmonella bacteremia in children. Pediatr Infect Dis J. (1999) 18:1073–7. doi: 10.1097/00006454-199912000-00009,

2. Marchello, CS, Fiorino, F, Pettini, E, and Crump, JAVacc-iNTS Consortium Collaborators. Incidence of non-typhoidal Salmonella invasive disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Infect. (2021) 83:523–32. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2021.06.029,

3. GBD 2017 Non-Typhoidal Salmonella Invasive Disease Collaborators. The global burden of non-typhoidal salmonella invasive disease: a systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2017. Lancet Infect Dis. (2019) 19:1312–24. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(19)30418-9,

4. Weinstein, E, Lamba, K, Bond, C, Peralta, V, Needham, M, Beam, S, et al. Outbreak of Salmonella Typhimurium infections linked to commercially distributed raw Milk—California and four other states, September 2023-march 2024. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. (2025) 74:433–8. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm7427a1,

5. Braden, CR. Salmonella enterica serotype enteritidis and eggs: a national epidemic in the United States. Clin Infect Dis. (2006) 43:512–7. doi: 10.1086/505973,

6. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Multistate outbreak of Salmonella typhimurium infections associated with eating ground beef--United States, 2004. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. (2006) 55:180–2.

7. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Outbreak of Salmonella serotype Saintpaul infections associated with multiple raw produce items--United States, 2008. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. (2008) 57:929–34.

8. Cherry, B, Burns, A, Johnson, GS, Pfeiffer, H, Dumas, N, Barrett, D, et al. Salmonella Typhimurium outbreak associated with veterinary clinic. Emerg Infect Dis. (2004) 10:2249–51. doi: 10.3201/eid1012.040714,

9. Marzel, A, Desai, PT, Goren, A, Schorr, YI, Nissan, I, Porwollik, S, et al. Persistent infections by nontyphoidal Salmonella in humans: epidemiology and genetics. Clin Infect Dis. (2016) 62:879–86. doi: 10.1093/cid/civ1221,

10. Olsen, SJ, DeBess, EE, McGivern, TE, Marano, N, Eby, T, Mauvais, S, et al. A nosocomial outbreak of fluoroquinolone-resistant salmonella infection. N Engl J Med. (2001) 344:1572–9. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200105243442102,

12. Bousfiha, A, Moundir, A, Tangye, SG, Picard, C, Jeddane, L, Al-Herz, W, et al. The 2022 update of IUIS phenotypical classification for human inborn errors of immunity. J Clin Immunol. (2022) 42:1508–20. doi: 10.1007/s10875-022-01352-z,

13. Peñafiel Vicuña, AK, Yamazaki Nakashimada, M, León Lara, X, Mendieta Flores, E, Nuñez Núñez, ME, Lona-Reyes, JC, et al. Mendelian susceptibility to mycobacterial disease: retrospective clinical and genetic study in Mexico. J Clin Immunol. (2022) 43:123–35. doi: 10.1007/s10875-022-01357-8,

14. Mahdaviani, SA, Mansouri, D, Jamee, M, Zaki-Dizaji, M, Aghdam, KR, Mortaz, E, et al. Mendelian susceptibility to mycobacterial disease (MSMD): clinical and genetic features of 32 Iranian patients. J Clin Immunol. (2020) 40:872–82. doi: 10.1007/s10875-020-00813-7,

15. Prando, C, Samarina, A, Bustamante, J, Boisson-Dupuis, S, Cobat, A, Picard, C, et al. Inherited IL-12p40 deficiency: genetic, immunologic, and clinical features of 49 patients from 30 kindreds. Medicine (Baltimore). (2013) 92:109–22. doi: 10.1097/MD.0b013e31828a01f9,

16. Averbuch, D, Chapgier, A, Boisson-Dupuis, S, Casanova, JL, and Engelhard, D. The clinical spectrum of patients with deficiency of signal transducer and activator of Transcription-1. Pediatr Infect Dis J. (2011) 30:352–5. doi: 10.1097/INF.0b013e3181fdff4a,

17. Minegishi, Y, Saito, M, Morio, T, Watanabe, K, Agematsu, K, Tsuchiya, S, et al. Human tyrosine kinase 2 deficiency reveals its requisite roles in multiple cytokine signals involved in innate and acquired immunity. Immunity. (2006) 25:745–55. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2006.09.009,

18. Solanky, D, and Kwan, B. Nontyphoid Salmonella empyema in a patient with type 2 diabetes mellitus. J Glob Infect Dis. (2020) 12:219–20. doi: 10.4103/jgid.jgid_190_20,

19. Othman, MK, Yusof, Z, Hussin, SA, Samsudin, N, Muhd Besari, AB, and W Isa, WYH. The unusual cause of cardiac tamponade. JACC Case Rep. (2022) 4:1288–91. doi: 10.1016/j.jaccas.2022.07.016,

20. Mori, N, Szvalb, AD, Adachi, JA, Tarrand, JJ, and Mulanovich, VE. Clinical presentation and outcomes of non-typhoidal Salmonella infections in patients with cancer. BMC Infect Dis. (2021) 21:1021. doi: 10.1186/s12879-021-06710-7,

21. Small, C, Bria, A, Pena-Cotui, NM, Beatty, N, and Ritter, AS. Disseminated Salmonella infection in an immunocompromised patient. Cureus. (2022) 14:e26922. doi: 10.7759/cureus.26922,

22. Gerada, J, Ganeshanantham, G, Dawwas, MF, Winterbottom, AP, Sivaprakasam, R, Butler, AJ, et al. Infectious aortitis in a liver transplant recipient. Am J Transplant. (2013) 13:2479–82. doi: 10.1111/ajt.12353,

23. Mete, AÖ, and Tekin, ŞS. A rare case of salmonellosis with multifocal osteomyelitis and pulmonary involvement. J Infect Public Health. (2020) 13:1787–90. doi: 10.1016/j.jiph.2020.09.005,

24. An, K, Wu, Z, Zhong, C, and Li, S. Case report: uncommon presentation of Salmonella Dublin infection as a large paravertebral abscess. Front Med (Lausanne). (2023) 10:1276360. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2023.1276360,

25. Myojin, S, Kamiyoshi, N, and Kugo, M. Pyogenic spondylitis and paravertebral abscess caused by Salmonella Saintpaul in an immunocompetent 13-year-old child: a case report. BMC Pediatr. (2018) 18:24. doi: 10.1186/s12887-018-1010-5,

Keywords: abscess, children, osteomyelitis, Salmonella, spondylitis

Citation: Guo S and Zhu Y (2026) Case Report: A case of Salmonella spondylitis masquerading as tuberculosis in a child. Front. Med. 12:1754318. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2025.1754318

Edited by:

Jonas Wolf, Moinhos de Vento Hospital, BrazilReviewed by:

Jiafeng Zhang, Shanghai Changzheng Hospital, ChinaFelipe Wachholz Bartz, Federal University of Health Sciences of Porto Alegre, Brazil

Copyright © 2026 Guo and Zhu. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Yu Zhu, emh1eXVfd2pAMTYzLmNvbQ==

Shuai Guo

Shuai Guo Yu Zhu

Yu Zhu