Abstract

Background:

With the increasing use of assisted reproductive technology (ART), more women with endometriosis are achieving pregnancy through ART. However, the impact of endometriosis on pregnancy and perinatal outcomes following ART remains controversial. This study aimed to clarify the association between endometriosis and adverse pregnancy and perinatal outcomes through a meta-analysis.

Methods:

A systematic search of PubMed, Embase, Web of Science, and Cochrane Library was conducted to identify relevant studies published before March 12, 2025. Cohort studies comparing adverse pregnancy and perinatal outcomes between women with and without endometriosis undergoing ART were included. Meta-analysis was performed using STATA 12.0 and R 4.3.2 software to calculate risk ratios (RRs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for the association between endometriosis and adverse outcomes. Heterogeneity among studies was quantified using Cochran’s Q test, I2 statistics, and 95% prediction intervals (PIs). Subgroup analyses, sensitivity analyses, and publication bias assessments were also conducted.

Results:

A total of 29 cohort studies, including 93,071 women with endometriosis and 1,350,005 controls, were included in the meta-analysis. Compared with women without endometriosis, those with endometriosis undergoing ART had significantly lower clinical pregnancy rate (RR 0.850, 95% CI 0.726–0.994, 95% PI 0.570–1.267) and live birth rate (RR 0.716, 95% CI 0.556–0.923, 95% PI 0.341–1.504). They were also at higher risk for preterm birth (RR 1.277, 95% CI 1.187–1.373, 95% PI 1.024–1.591), placenta previa (RR 2.246, 95% CI 1.759–2.869, 95% PI 1.028–4.910), postpartum hemorrhage (RR 1.310, 95% CI 1.198–1.432, 95% PI 1.154–1.486), cesarean section (RR 1.296, 95% CI 1.165–1.441, 95% PI 0.944–1.779), low birth weight (RR 1.159, 95% CI 1.050–1.279, 95% PI 1.025–1.310), stillbirth (RR 1.219, 95% CI 1.032–1.440, 95% PI 0.930–1.597), and hypertensive disorders of pregnancy (RR 1.161, 95% CI 1.096–1.231, 95% PI 1.057–1.276). However, no significant differences were observed between the two groups in the risk of small for gestational age, miscarriage, preeclampsia, large for gestational age, or ectopic pregnancy (all p > 0.05). Subgroup analyses revealed variations in outcomes based on ethnicity, endometriosis stage, and mode of ART, but the overall results were robust.

Conclusion:

Endometriosis significantly impacts pregnancy and perinatal outcomes following ART, increasing the risk of multiple adverse outcomes. These findings provide critical evidence for individualized reproductive treatment and perinatal care in women with endometriosis.

1 Introduction

Endometriosis is a common chronic gynecological disorder characterized by the presence of functional endometrial-like tissue outside the uterine cavity, often accompanied by chronic inflammation and fibrotic changes (1). The prevalence of endometriosis is estimated to be approximately 10% among women of reproductive age, and it significantly impacts female fertility, being recognized as one of the leading causes of infertility in women (2). Studies have shown that women with endometriosis have substantially lower natural conception rates compared to those without the condition, particularly in cases of moderate to severe disease (3, 4). With the widespread application of assisted reproductive technology (ART), including in vitro fertilization (IVF) and intracytoplasmic sperm injection (ICSI), an increasing number of women with endometriosis are achieving pregnancy through these methods. However, existing evidence suggests that endometriosis may not only reduce the success rates of ART but also increase the risk of adverse pregnancy and perinatal outcomes (5, 6).

Previous research has demonstrated a strong association between endometriosis and various adverse pregnancy and perinatal outcomes. For instance, women with endometriosis were at a higher risk of preterm birth, which may be linked to chronic inflammation and alterations in the endometrial environment caused by the disease (7). Some studies have reported that women with endometriosis experience lower clinical pregnancy and live birth rates, as well as an increased risk of complications such as preterm birth, low birth weight (LBW), and hypertensive disorders of pregnancy (HDP) (8–10). Additionally, endometriosis has been associated with placental abnormalities, including placental abruption, abnormal placental implantation, and placenta previa, likely due to uterine damage and impaired endometrial function (11, 12). Furthermore, women with endometriosis undergoing ART were reported to have higher rates of cesarean section, placenta previa, and ectopic pregnancy compared to those without the condition (13–15). However, studies investigating these adverse outcomes showed considerable heterogeneity, which may be attributed to differences in sample sizes, endometriosis stage, mode of ART, and the extent of adjustment for confounding factors. This heterogeneity limited the comparability and generalizability of the findings.

Although systematic reviews and meta-analyses have previously explored the relationship between endometriosis and adverse pregnancy outcomes (16–18), these studies were published some time ago and often did not focus specifically on women with endometriosis undergoing ART. Moreover, current research has insufficiently addressed subgroup analyses related to disease stage, ethnic differences, and ART modalities. Considering the increasing prevalence of ART procedures among women diagnosed with endometriosis, it becomes crucial to explore the influence of this condition on ART outcomes. Gaining a deeper understanding of this relationship could offer essential guidance for tailoring reproductive advice and enhancing therapeutic approaches to meet the specific needs of these patients. Therefore, this study aimed to perform a meta-analysis to evaluate the risk of adverse pregnancy and perinatal outcomes in women with endometriosis undergoing ART. Additionally, this study seeks to investigate the potential impact of subgroup factors, including race, disease stage, and ART type, on the observed associations.

2 Methods

2.1 Protocol registration

This study followed the principles outlined in the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) framework (19). Additionally, the research protocol was registered in the PROSPERO database with the identifier CRD420251021677.

2.2 Search strategy

A systematic search of multiple electronic databases, including PubMed, Embase, Web of Science, and the Cochrane Library, was conducted to identify studies published from their inception up to March 12, 2025, investigating the association between endometriosis and reproductive or perinatal outcomes. The search strategy employed a combination of keywords, such as (“endometriosis” or “endometrioses” or “endometrioma” or “endometriomas”) AND (“pregnancy outcome” or “obstetric outcome” or “reproductive outcome” or “fertility outcome” or “preterm” or “cesarean section” or “small for gestational age” or “placenta previa” or “preeclampsia” or “postpartum hemorrhage” or “miscarriage” or “stillbirth” or “hypertensive disorders of pregnancy”) AND (“cohort study” or “cohort studies” or “longitudinal”). Supplementary Files 1 provided a detailed description of the search methodology applied to each database. No language restrictions were imposed during the search process. Furthermore, the reference lists of the relevant review articles included were manually reviewed to identify any additional relevant studies that were potentially missed in the database query.

2.3 Inclusion and exclusion criteria

For inclusion in this meta-analysis, studies were required to fulfill the following criteria: (i) Studies employed a cohort design to evaluate the relationship between endometriosis and adverse pregnancy outcomes; (ii) The exposure group consisted of women diagnosed with endometriosis who underwent ART; (iii) The control group comprised women without endometriosis who also underwent ART; (iv) The studies reported either risk ratios (RRs) or odds ratios (ORs) along with their 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for the association between endometriosis and adverse reproductive or perinatal outcomes. Exclusion criteria included: (i) Studies with a case–control or cross-sectional design; (ii) The reported outcomes were based on mixed populations of women who conceived either naturally or through ART; (iii) Studies that did not report required outcomes; (iv) Conference abstracts, reviews, case reports, editorials, or commentaries.

2.4 Data extraction and quality assessment

The screening of literature, extraction of data, and assessment of study quality were independently conducted by two researchers. Any discrepancies between the two were resolved through consultation with a third reviewer to reach a consensus. The extracted data encompassed the following categories: (i) study characteristics, including the first author’s name, publication year, study design, geographic location, and sample size; (ii) participant information, such as the diagnosis of endometriosis, its stage or phenotype, maternal age, method of conception, and whether surgical intervention for endometriosis had been performed; (iii) outcomes included in the meta-analysis and adjusted confounding variables. The quality of the included cohort studies was assessed using the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) (20), which evaluates three dimensions: cohort selection (4 items, 0–4 stars), cohort comparability (1 item, 0–2 stars), and outcome assessment (3 items, 0–3 stars). Each study was assigned a total score ranging from 0 to 9, with studies scoring 0–4 considered low quality, those scoring 5–6 categorized as moderate quality, and scores of 7–9 reflecting high-quality studies (21).

2.5 Statistical analysis

Meta-analyses were performed using STATA software (version 12.0) and R software (version 4.3.2). To evaluate the relationship between endometriosis and adverse pregnancy outcomes, RRs accompanied by 95% CIs were calculated. The degree of statistical heterogeneity across the included studies was examined using Cochran’s Q test, alongside the I2 and Tau2 statistics, as well as the 95% prediction interval (PI) (22, 23). Criteria for significant heterogeneity included p < 0.1 or I2 > 50%. When heterogeneity was detected, estimates were pooled using a random-effects model; otherwise, a fixed-effects model was applied (24). Subgroup analyses were conducted for groups with at least two included studies to analyze the effects of ethnicity, endometriosis stage, and categories of ART on the outcomes. Sensitivity analyses were conducted to assess the robustness of the results by excluding individual studies. Publication bias was evaluated using Begg and Mazumdar’s (25) and Egger’s et al. (26) tests. Statistical significance was defined as a two-sided p-value below 0.05.

3 Results

3.1 Study selection

A comprehensive search of the databases initially identified 9,887 articles for potential inclusion. After the removal of duplicate entries, 6,767 records remained. Titles and abstracts were then screened, resulting in the exclusion of 6,654 articles that were deemed unrelated to the research focus. Subsequently, 113 full-text articles underwent detailed evaluation to determine their eligibility. Following the application of inclusion and exclusion criteria, 84 studies were eliminated from consideration for the meta-analysis. Among these, 15 lacked a cohort design, 48 failed to provide essential RRs or ORs alongside 95% CIs for adverse pregnancy outcomes, and 21 did not distinguish between ART and natural conception in individuals with endometriosis. Ultimately, 29 studies met the eligibility criteria and were included in the meta-analysis (7, 9–11, 13–15, 27–48) (Figure 1).

Figure 1

Flow diagram of the process of study selection.

3.2 Characteristics and quality assessment of the included studies

The principal characteristics of the included studies and their participant cohorts were presented in Table 1. To ensure the incorporation of up-to-date and pertinent findings, only studies published from 2010 onward were considered for the meta-analysis. A total of 29 studies were ultimately included, encompassing 93,071 individuals diagnosed with endometriosis and 1,350,005 controls. Notably, two studies did not specify the number of participants analyzed. The primary outcomes assessed in the meta-analysis included clinical pregnancy rate, live birth rate, preterm birth, small for gestational age (SGA), placenta previa, and miscarriage. Secondary outcomes comprised preeclampsia, postpartum hemorrhage, cesarean section, LBW, large for gestational age (LGA), ectopic pregnancy, stillbirth, and HDP. Preterm birth was defined as delivery occurring before 37 completed weeks of gestation, while SGA and LGA were categorized as birth weights below the 10th percentile or above the 90th percentile for gestational age, respectively (49). LBW was defined as a birth weight under 2,500 g. All cohort studies included in the analysis were evaluated as being of high quality, as they provided detailed descriptions of their study designs (Supplemental Files 2).

Table 1

| First author (year) | Study design | Country/region | Diagnosis of endometriosis | Endometriosis stage/phenotype | Sample size (E/C) | Maternal age (E/C, years) | Mode of conception | Surgically treated endometriosis | Outcomes in meta-analysis | Adjustments |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gebremedhin et al. (2024) (31) | RCS | Australia | ICD-AM codes | All stages | 3,278/19,142 | 15–49 | ART | NR | Preeclampsia, PP, and PTB | Maternal age, birth year, socio-economic status, parity, and ethnicity/race |

| Yang et al. (2019) (47) | RCS | China | Laparoscopy or laparotomy | All stages | 1,006/2,012 | 33.04 ± 3.66/32.83 ± 3.76 | IVF/ICSI | Surgically treated and untreated endometriosis | Miscarriage | BMI, gravidity, parity, male factor infertility, total dose of FSH administered and number of oocytes retrieved |

| Glavind et al. (2017) (32) | Birth cohort study | Denmark | Histology | All stages | 193/1,614 | All age groups | ART | Surgically treated and untreated endometriosis | Preeclampsia, PTB, SGA, PH, and CS | Maternal age, maternal prepregnant BMI, parity, ethnicity, and years of school |

| Yu et al. (2022) (10) | RCS | China | NR | All stages | NR | NR | IVF | NR | PTB, SGA, LBW, and LGA | NR |

| Muteshi et al. (2018) (15) | RCS | United Kingdom | Laparoscopy | All stages | 531/737 | Median (range): 35 (23–44)/36 (19–44) | ART | NR | PTB, miscarriage, LBR, CPR, and EP | None |

| Vendittelli et al. (2025) (14) | RCS | France | Questionnaire survey | All stages | 543/13,382 | NR | ART | Surgically treated and untreated endometriosis | Preeclampsia, PP, PTB, SGA, PH, and stillbirth | Maternal age, maternal prepregnancy BMI, lives alone, geographic origin, and tobacco use during the pregnancy |

| Salmanov et al. (2024) (13) | RCS | Ukraine | Laparoscopy or vaginal ultrasound | All stages | 102/11,117 | All age groups | IVF | NR | Preeclampsia, PTB, SGA, CS, and stillbirth | Maternal age, BMI, parity, and year of birth of the child |

| Healy et al. (2010) (35) | RCS | Australia | NR | NR | 1,265/5,465 | Median (range): 34 (20–45) | IVF/ICSI | NR | PP and PH | Age, year of birth, country of birth Asia and Middle East, marital status, parity, any miscarriages or terminations of pregnancy, vertex presentation, tertiary and private hospital status, pre-eclampsia, APH, PP, PA, premature rupture of membranes, induced labour, caesarean section |

| Farland et al. (2022) (11) | Register-based cohort study | United States | ICD-9 and ICD-10 codes | All stages | 537/5,263 | 22–53/18–56 | ART | NR | PTB, SGA, CS, LBW, and HDP | Maternal age, body mass index, race, education, plurality, and birth year |

| Breintoft et al. (2022) (7) | Birth cohort study | Denmark | ICD-8 and ICD-10 codes | All stages | 247/2,102 | All age groups | ART | Surgically treated and untreated endometriosis | PTB | Maternal age, BMI, parity, years of school, country of birth, smoking during pregnancy, alcohol during pregnancy, and year of birth |

| Queiroz Vaz et al. (2017) (39) | RCS | Brazil | Laparoscopy or MRI | Deep endometriosis | 27/154 | 18–40 | IVF | Surgically treated and surgically untreated endometriosis | Miscarriage and CPR | None |

| Benaglia et al. (2012) (28) | RCS | Italy and Spain | Ultrasound | Ovarian endometrioma | 78/156 | 35.6 ± 3.5/36.1 ± 3.1 | IVF/ICSI | Surgically treated and surgically untreated endometriosis | PTB, SGA, CS, LBW, and LBR | Smoking, PTB, basal follicle-stimulating hormone and previous IVF |

| Sharma et al. (2020) (42) | PCS | India | Laparoscopy | rASRM stage III/IV | 294/358 | 18–40 | IVF | Surgically treated and untreated endometriosis | Miscarriage, LBR, and CPR | Age, ovarian reserve, the number of mature oocyte and embryos |

| Rombauts et al. (2014) (40) | RCS | Australia | NR | NR | 316/4,221 | NR | IVF | NR | PP | Endometrial tickness, smoking, embryo transfer type, and cycle type |

| Wu et al. (2021) (46) | RCS | China | Transvaginal ultrasonography or MRI or abdominopelvic surgery | Ovarian endometrioma | 862/862 | 32.73 ± 4.51/32.82 ± 4.82 | IVF/ICSI | Surgically treated and surgically untreated endometriosis | LBR | NR |

| Sunkara et al. (2021) (43) | Register-based cohort study | United Kingdom | NR | All stages | 5,053/112,300 | ≥ 18 | IVF/ICSI | NR | PTB and LBW | Female age category, year of treatment, previous live birth, IVF or ICSI, number of embryos transferred and fresh or frozen cycles |

| Hjordt Hansen et al. (2014) (36) | Register-based cohort study | Denmark | ICD-8 and ICD-10 codes | All stages | NR | NR | ART | NR | Miscarriage and EP | None |

| Carusi et al. (2022) (29) | RCS | United States | ICD codes | All stages | 1,259/21,086 | All age groups | ART | NR | PP | Advanced maternal age, history of previous cesarean delivery, and multiple gestations |

| González-Comadran et al. (2017) (34) | RCS | Latin America | NR | All stages | 3,583/18,833 | 34.83 ± 3.47/34.61 ± 3.91 | IVF/ICSI | NR | Miscarriage, LBR, and CPR | Age of the female partner and number of embryos transferred |

| Fujii et al. (2016) (30) | RCS | Japan | Laparoscopy | All stages | 92/512 | Mean: 34.7/35.4 | ART | Surgically treated and untreated endometriosis | PP, PTB, and SGA | Age, parity, and the number of transferred embryos |

| Sharma et al. (2019) (41) | RCS | India | Laparoscopy | rASRM stage III/IV | 355/466 | 32.67 ± 2.53/33.02 ± 3.4 | IVF/ICSI | Surgically treated and untreated endometriosis | Miscarriage, LBR, and CPR | None |

| Zhang et al. (2024) (48) | Register-based cohort study | Australia | ICD-10-AM | Deep, ovarian, superficial, or other endometriosis | 1,379/21,795 | 34.3 ± 4.0/34.9 ± 4.4 | ART | NR | PTB, SGA, and LGA | Mother’s age, whether mother had previous pregnancy, type of treatment, whether intracytoplasmic sperm injection was performed, number of embryo(s) transferred, stage of embryo(s) transferred, ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome during cycle, gestational hypertension, maternal smoking during pregnancy, socioeconomic index for area quintile, year of birth, and gestational diabetes |

| Volodarsky-Perel et al. (2022) (44) | RCS | Canada | Surgery or ultrasound | rASRM stage III-IV | 75/982 | 35.7 ± 3.9/35.6 ± 4.4 | IVF | NR | PP and PTB | Female age at embryo transfer, body mass index, number of previous pregnancies, hypothyroidism, chronic hypertension, pregestational diabetes mellitus, antral follicle count, endometrial thickness on the oocyte maturation trigger day, ICSI cycles, embryo stage at transfer, frozen embryo transfer cycles, number of transferred embryos, pre-eclampsia, GDM, newborn gender, PTB, and birthweight |

| Perkins et al. (2015) (38) | Register-based cohort study | United States | NR | All stages | 51,086/327,937 | NR | ART | NR | EP | Patient age, number of prior ART cycles, number of prior spontaneous abortions, number of prior live births, infertility diagnosis, year of ART procedure, use of assisted hatching, use of intracytoplasmic sperm injection, day of embryo transfer, number of embryos transferred, number of supernumerary embryos cryopreserved, and ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome |

| Wu et al. (2020) (45) | RCS | China | Histology | NR | 1,111/5,975 | 31.96 ± 3.50/31.74 ± 4.10 | IVF/ICSI | NR | PTB, SGA, LBW, and LGA | Maternal age, duration of infertility, parity, history of preterm birth, antral follicle count, fertilization method, endometrial preparation, embryo stage, number of embryos transferred, endometrium thickness, mode of delivery and pregnancy-related complications |

| Alson et al. (2024) (27) | PCS | Sweden | Ultrasound | Deep-infiltrating endometriosis and/or endometrioma | 234/806 | 32.3 ± 4.0/31.9 ± 4.0 | IVF/ICSI | NR | LBR and CPR | Age, serum antimullerian hormone, BMI, protocol, stimulation days, follicle-stimulating hormone dose, and day for embryo transfer |

| Gómez-Pereira et al. (2023) (33) | RCS | Spain | Laparoscopy or vaginal ultrasound | All stages | 45/1,125 | NR | IVF | Surgically treated and untreated endometriosis | PP | None |

| Lee et al. (2022) (37) | RCS | China | Laparoscopy or ultrasound | All stages | 421/3,253 | NR | IVF/ICSI | NR | HDP | None |

| Velez et al. (2022) (9) | RCS | Canada | ICD-9 codes | All stages | 19,099/768,350 | 32.95 ± 4.88/30.03 ± 5.60 | ART | Surgically treated and untreated endometriosis | PP, PTB, PH, CS, stillbirth, and HDP | Maternal age, income quantile, and history of fibroids |

Characteristics of the included studies investigating the association between endometriosis and adverse reproductive and perinatal outcomes in women undergoing assisted reproductive technology.

E, exposure group; C, control group; RCS, retrospective cohort study; PCS, prospective cohort study; ICD, International Classifcation of Diseases; AM, Australian Modifcation; ART, assisted reproductive technology; NR, not reported; IVF, in vitro fertilization; ICSI, intracytoplasmic sperm injection; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging; rASRM, revised American Society for Reproductive Medicine classification; ICD-10-AM, International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, 10th revision, Australian Modification; CPR, clinical pregnancy rate; LBR, live birth rate; PTB, preterm birth; SGA, small for gestational age; PP, placenta previa; PH, postpartum hemorrhage; CS, cesarean section; LBW, low birth weight; LGA, large for gestational age; EP, ectopic pregnancy; HDP, hypertensive disorders of pregnancy.

3.3 Pooled effect and subgroup analysis of the primary outcomes

3.3.1 Clinical pregnancy rate

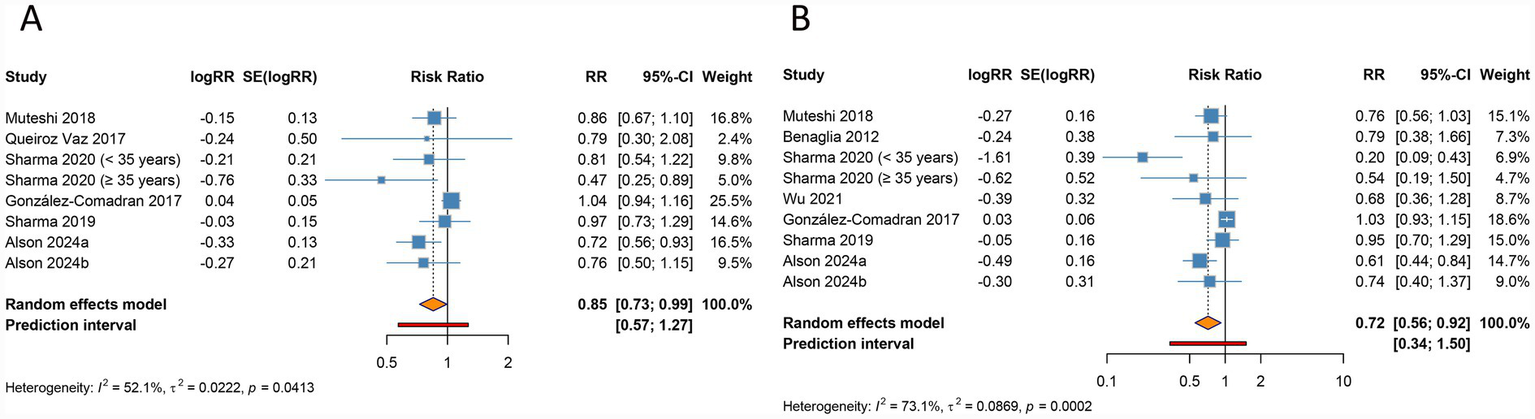

The meta-analysis identified a notable reduction in clinical pregnancy rate among women with endometriosis undergoing ART compared to those without endometriosis (RR 0.850, 95% CI 0.726–0.994, 95% PI 0.570–1.267), accompanied by significant heterogeneity across studies (I2 = 52.1%, Tau2 = 0.0222) (Table 2; Figure 2A). Ethnicity-based subgroup analysis indicated that this association was statistically significant among Caucasian populations (RR 0.784, 95% CI 0.666–0.923, 95% PI 0.548–1.122), whereas no significant relationship was observed in Asian (RR 0.786, 95% CI 0.554–1.115, 95% PI 0.231–2.673) or other ethnic groups (RR 1.041, 95% CI 0.936–1.157, 95% PI 0.522–2.074). Further stratification by endometriosis stage and ART method (IVF/ICSI) revealed no notable differences in all stages or within the IVF/ICSI subgroup (all p > 0.05) (Table 2; Supplementary Figure S1).

Table 2

| Outcomes and subgroups | Number of studies | Meta-analysis | Heterogeneity | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RR | 95% CI | p value | 95% PI | I2, Tau2 | p value | ||

| Clinical pregnancy rate | |||||||

| Overall | 8 | 0.850 | 0.726–0.994 | 0.042 | 0.570–1.267 | 52.1%, 0.0222 | 0.041 |

| Ethnicity | |||||||

| Caucasian | 3 | 0.784 | 0.666–0.923 | 0.004 | 0.548–1.122 | 0%, 0 | 0.610 |

| Asian | 3 | 0.786 | 0.554–1.115 | 0.177 | 0.231–2.673 | 51.7%, 0.0491 | 0.126 |

| Others | 2 | 1.041 | 0.936–1.157 | 0.465 | 0.522–2.074 | 0%, 0 | 0.576 |

| Endometriosis stage | |||||||

| All stages | 2 | 1.013 | 0.918–1.117 | 0.802 | 0.182–5.282 | 49.5%, 0.0093 | 0.159 |

| Others | 6 | 0.784 | 0.673–0.914 | 0.002 | 0.639–0.962 | 0.4%, 0.0002 | 0.413 |

| Mode of ART | |||||||

| IVF/ICSI | 7 | 0.838 | 0.693–1.012 | 0.066 | 0.513–1.368 | 57.3%, 0.0308 | 0.029 |

| Live birth rate | |||||||

| Overall | 9 | 0.716 | 0.556–0.923 | 0.010 | 0.341–1.504 | 73.1%, 0.0869 | <0.001 |

| Ethnicity | |||||||

| Caucasian | 4 | 0.698 | 0.571–0.854 | 0.001 | 0.504–0.967 | 0%, 0 | 0.775 |

| Asian | 4 | 0.542 | 0.274–1.073 | 0.079 | 0.059–4.957 | 78.6%, 0.3622 | 0.003 |

| Endometriosis stage | |||||||

| All stages | 2 | 0.917 | 0.685–1.228 | 0.560 | 0.046–18.242 | 70.9%, 0.0332 | 0.064 |

| Others | 7 | 0.633 | 0.455–0.880 | 0.007 | 0.258–1.549 | 60.0%, 0.1057 | 0.020 |

| Mode of ART | |||||||

| IVF/ICSI | 8 | 0.698 | 0.518–0.941 | 0.018 | 0.294–1.659 | 75.1%, 0.1109 | <0.001 |

| Preterm birth | |||||||

| Overall | 21 | 1.277 | 1.187–1.373 | <0.001 | 1.024–1.591 | 54.1%, 0.0098 | 0.002 |

| Ethnicity | |||||||

| Caucasian | 7 | 1.289 | 1.208–1.375 | <0.001 | 0.975–1.651 | 37.2%, 0.0078 | 0.145 |

| Asian | 5 | 1.626 | 1.024–2.583 | 0.039 | 0.394–6.716 | 81.6%, 0.2052 | <0.001 |

| Others | 9 | 1.251 | 1.195–1.308 | <0.001 | 1.089–1.432 | 27.9%, 0.0024 | 0.196 |

| Endometriosis stage | |||||||

| All stages | 16 | 1.264 | 1.218–1.311 | <0.001 | 1.185–1.344 | 6.5%, 0.0004 | 0.380 |

| Others | 5 | 1.522 | 0.744–3.115 | 0.250 | 0.158–14.628 | 85.1%, 0.5307 | <0.001 |

| Mode of ART | |||||||

| IVF/ICSI | 9 | 1.316 | 1.151–1.506 | <0.001 | 0.920–1.884 | 73.1%, 0.0195 | <0.001 |

| Uncategorized | 12 | 1.240 | 1.172–1.312 | <0.001 | 1.088–1.424 | 14.5%, 0.0023 | 0.303 |

| Small for gestational age | |||||||

| Overall | 14 | 0.994 | 0.915–1.080 | 0.891 | 0.743–1.285 | 28.0%, 0.0123 | 0.156 |

| Ethnicity | |||||||

| Caucasian | 4 | 1.020 | 0.916–1.137 | 0.715 | 0.856–1.216 | 0%, 0 | 0.753 |

| Asian | 5 | 1.023 | 0.832–1.257 | 0.830 | 0.764–1.370 | 0%, 0 | 0.813 |

| Others | 5 | 0.955 | 0.693–1.316 | 0.778 | 0.362–2.516 | 71.6%, 0.0949 | 0.007 |

| Endometriosis stage | |||||||

| All stages | 10 | 1.001 | 0.918–1.091 | 0.979 | 0.678–1.438 | 47.0%, 0.0221 | 0.049 |

| Others | 4 | 0.908 | 0.665–1.240 | 0.542 | 0.547–1.506 | 0%, 0 | 0.868 |

| Mode of ART | |||||||

| IVF/ICSI | 6 | 1.025 | 0.924–1.139 | 0.639 | 0.894–1.176 | 0%, 0 | 0.926 |

| Uncategorized | 8 | 0.970 | 0.777–1.211 | 0.789 | 0.532–1.770 | 55.6%, 0.0518 | 0.027 |

| Placenta previa | |||||||

| Overall | 11 | 2.246 | 1.759–2.869 | <0.001 | 1.028–4.910 | 78.1%, 0.1076 | <0.001 |

| Ethnicity | |||||||

| Caucasian | 2 | 4.692 | 2.800–7.863 | <0.001 | 0.165–133.404 | 0%, 0 | 0.418 |

| Others | 8 | 1.866 | 1.518–2.295 | <0.001 | 1.017–3.424 | 70.9%, 0.0547 | 0.001 |

| Endometriosis stage | |||||||

| All stages | 8 | 2.395 | 1.760–3.260 | <0.001 | 0.929–6.175 | 84.0%, 0.1357 | <0.001 |

| Others | 3 | 1.838 | 1.404–2.406 | <0.001 | 1.018–3.320 | 0%, 0 | 0.425 |

| Mode of ART | |||||||

| IVF/ICSI | 5 | 2.266 | 1.689–3.040 | <0.001 | 1.058–4.852 | 54.5%, 0.0527 | 0.067 |

| Uncategorized | 6 | 2.277 | 1.537–3.375 | <0.001 | 0.689–7.531 | 84.8%, 0.1762 | <0.001 |

| Miscarriage | |||||||

| Overall | 9 | 1.170 | 0.706–1.940 | 0.542 | 0.217–6.309 | 93.5%, 0.4673 | <0.001 |

| Ethnicity | |||||||

| Caucasian | 2 | 1.649 | 0.245–11.100 | 0.607 | - | 98.7%, 1.8687 | <0.001 |

| Asian | 5 | 1.115 | 0.927–1.342 | 0.249 | 0.858–1.450 | 0%, 0 | 0.968 |

| Others | 2 | 1.042 | 0.862–1.260 | 0.669 | 0.305–3.567 | 0%, 0 | 0.500 |

| Endometriosis stage | |||||||

| All stages | 5 | 1.305 | 0.687–2.480 | 0.417 | 0.146–11.662 | 96.7%, 0.5150 | <0.001 |

| Others | 4 | 1.028 | 0.630–1.678 | 0.911 | 0.464–2.277 | 0%, 0 | 0.835 |

| Mode of ART | |||||||

| IVF/ICSI | 7 | 1.079 | 0.945–1.232 | 0.261 | 0.914–1.273 | 0%, 0 | 0.974 |

| Uncategorized | 2 | 1.649 | 0.245–11.100 | 0.607 | - | 98.7%, 1.8687 | <0.001 |

Pooled effect and subgroup analysis of the association between endometriosis and primary adverse reproductive and perinatal outcomes.

ART, assisted reproductive technology; IVF, in vitro fertilization; ICSI, intracytoplasmic sperm injection.

Figure 2

Forest plots of the association between endometriosis and clinical pregnancy rate (A) and live birth rate (B) in women undergoing assisted reproductive technology.

3.3.2 Live birth rate

Live birth rate was found to be significantly lower in women with endometriosis undergoing ART relative to controls (RR 0.716, 95% CI 0.556–0.923, 95% PI 0.341–1.504), with significant heterogeneity present (I2 = 73.1%, Tau2 = 0.0869) (Table 2; Figure 2B). Subgroup analysis by ethnicity confirmed a significant reduction in live birth rate for Caucasian populations (RR 0.698, 95% CI 0.571–0.854, 95% PI 0.504–0.967), while findings for Asian groups were not statistically significant (RR 0.542, 95% CI 0.274–1.073, 95% PI 0.059–4.957). When examining endometriosis stage and ART method, a significant reduction in live birth rate was observed specifically within the IVF/ICSI subgroup (RR 0.698, 95% CI 0.518–0.941, 95% PI 0.294–1.659), while no differences were detected across all endometriosis stages (RR 0.917, 95% CI 0.685–1.228, 95% PI 0.046–18.242) (Table 2; Supplementary Figure S2).

3.3.3 Preterm birth

Endometriosis was found to be significantly associated with a higher risk of preterm birth (RR 1.277, 95% CI 1.187–1.373, 95% PI 1.024–1.591), with notable heterogeneity across studies (I2 = 54.1%, Tau2 = 0.0098) (Table 2; Figure 3A). Ethnicity-specific analysis demonstrated a consistent significant correlation in Caucasian (RR 1.289, 95% CI 1.208–1.375, 95% PI 0.975–1.651), Asian (RR 1.626, 95% CI 1.024–2.583, 95% PI 0.394–6.716), and other ethnic groups (RR 1.251, 95% CI 1.195–1.308, 95% PI 1.089–1.432). Stratification by disease stage indicated consistent risk across all stages of endometriosis (RR 1.264, 95% CI 1.218–1.311, 95% PI 1.185–1.344), and similar significant associations were observed irrespective of the ART modality employed (IVF/ICSI: RR 1.316, 95% CI 1.151–1.506, 95% PI 0.920–1.884; Uncategorized: RR 1.240, 95% CI 1.172–1.312, 95% PI 1.088–1.424) (Table 2; Supplementary Figure S3).

Figure 3

![Forest plot showing meta-analysis results. Panel A presents data from multiple studies on a specific treatment effect with log risk ratios, standard errors, and weights. Risk ratios (RR) are plotted with confidence intervals (CI). The random effects model shows an RR of 1.28 with CI of [1.19, 1.37]. Panel B similarly presents data with a common effect model showing an RR of 0.99 with CI of [0.91, 1.08]. Heterogeneity is indicated with I-squared values. The plot includes diamonds representing overall effect estimates and confidence intervals.](https://www.frontiersin.org/files/Articles/1630529/xml-images/fmed-13-1630529-g003.webp)

Forest plots of the association between endometriosis and preterm birth (A) and small for gestational age (B) in women undergoing assisted reproductive technology.

3.3.4 Small for gestational age

The pooled data revealed no significant relationship between endometriosis and the risk of SGA (RR 0.994, 95% CI 0.915–1.080, 95% PI 0.743–1.285), with heterogeneity across studies remaining negligible (I2 = 28.0%, Tau2 = 0.0123) (Table 2; Figure 3B). Further subgroup analyses, stratified by ethnicity, endometriosis stage, and mode of ART, also failed to identify significant associations, suggesting that the presence of endometriosis does not substantially affect the likelihood of SGA in women undergoing ART (all p > 0.05) (Table 2; Supplementary Figure S4).

3.3.5 Placenta previa

Endometriosis was identified as a significant risk factor for placenta previa (RR 2.246, 95% CI 1.759–2.869, 95% PI 1.028–4.910), with high heterogeneity observed across studies (I2 = 78.1%, Tau2 = 0.1076) (Table 2; Figure 4A). Ethnicity-based subgroup analyses revealed notable associations in Caucasian populations (RR 4.692, 95% CI 2.800–7.863, 95% PI 0.165–133.404) as well as in other ethnic groups (RR 1.866, 95% CI 1.518–2.295, 95% PI 1.017–3.424). Further stratification by endometriosis stage revealed consistent associations within all stage subgroup (RR 2.395, 95% CI 1.760–3.260, 95% PI 0.929–6.175), while different ART approaches similarly showed significant correlations (IVF/ICSI: RR 2.266, 95% CI 1.689–3.040, 95% PI 1.058–4.852; Uncategorized: RR 2.277, 95% CI 1.537–3.375, 95% PI 0.689–7.531) (Table 2; Supplementary Figure S5).

Figure 4

Forest plots of the association between endometriosis and placenta previa (A) and miscarriage (B) in women undergoing assisted reproductive technology.

3.3.6 Miscarriage

The aggregated data indicated no significant connection between endometriosis and the risk of miscarriage (RR 1.170, 95% CI 0.706–1.940, 95% PI 0.217–6.309), with heterogeneity across studies remaining significant (I2 = 93.5%, Tau2 = 0.4673) (Table 2; Figure 4B). Subgroup analyses based on ethnicity, disease stage, and ART type also failed to reveal significant associations, suggesting that endometriosis does not substantially influence miscarriage risk in women undergoing ART (all p > 0.05) (Table 2; Supplementary Figure S6).

3.4 Pooled effect and subgroup analysis of the secondary outcomes

3.4.1 Preeclampsia

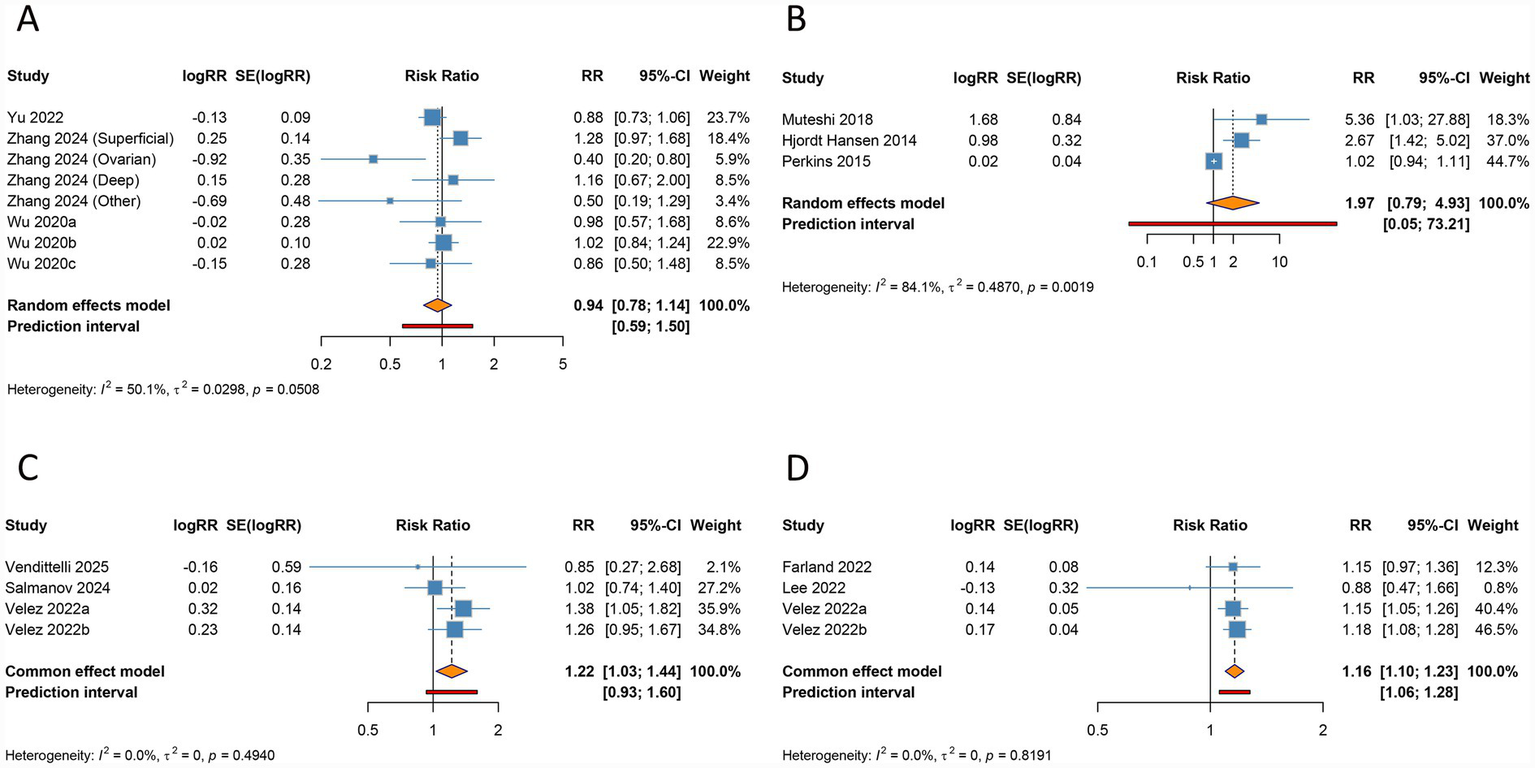

The meta-analysis revealed no significant correlation between endometriosis and preeclampsia (RR 1.082, 95% CI 0.986–1.188, 95% PI 0.626–1.777), with low heterogeneity noted across the studies included (I2 = 46.8%, Tau2 = 0.0168) (Table 3; Figure 5A). Subgroup analysis by ethnicity identified a significant association in Caucasian populations (RR 1.139, 95% CI 1.027–1.263, 95% PI 0.908–1.428), whereas no significant links were identified across other subgroups, including those categorized by endometriosis stage or ART modality (all p > 0.05) (Table 3; Supplementary Figure S7).

Table 3

| Outcomes and subgroups | Number of studies | Meta-analysis | Heterogeneity | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RR | 95% CI | p value | 95% PI | I2, Tau2 | p value | ||

| Preeclampsia | |||||||

| Overall | 4 | 1.082 | 0.986–1.188 | 0.097 | 0.626–1.777 | 46.8%, 0.0168 | 0.131 |

| Ethnicity | |||||||

| Caucasian | 3 | 1.139 | 1.027–1.263 | 0.014 | 0.908–1.428 | 0%, 0 | 0.785 |

| Endometriosis stage | |||||||

| All stages | 4 | 1.082 | 0.986–1.188 | 0.097 | 0.626–1.777 | 46.8%, 0.0168 | 0.131 |

| Mode of ART | |||||||

| Uncategorized | 3 | 0.927 | 0.759–1.132 | 0.459 | 0.386–2.576 | 25.8%, 0.0242 | 0.260 |

| Postpartum hemorrhage | |||||||

| Overall | 5 | 1.310 | 1.198–1.432 | <0.001 | 1.154–1.486 | 0%, 0 | 0.880 |

| Ethnicity | |||||||

| Caucasian | 2 | 1.220 | 0.930–1.602 | 0.151 | 0.209–7.120 | 0%, 0 | 0.746 |

| Others | 3 | 1.321 | 1.202–1.452 | <0.001 | 1.073–1.626 | 0%, 0 | 0.673 |

| Endometriosis stage | |||||||

| All stages | 4 | 1.318 | 1.192–1.458 | <0.001 | 1.119–1.552 | 0%, 0 | 0.772 |

| Mode of ART | |||||||

| IVF/ICSI | 2 | 1.349 | 1.200–1.516 | <0.001 | 0.632–2.879 | 0%, 0 | 0.506 |

| Uncategorized | 3 | 1.257 | 1.094–1.444 | 0.001 | 0.927–1.704 | 0%, 0 | 0.920 |

| Cesarean section | |||||||

| Overall | 6 | 1.296 | 1.165–1.441 | <0.001 | 0.944–1.779 | 94.3%, 0.0123 | <0.001 |

| Ethnicity | |||||||

| Caucasian | 3 | 1.679 | 1.173–2.404 | 0.005 | 0.424–6.642 | 73.6%, 0.0686 | 0.023 |

| Others | 3 | 1.173 | 1.148–1.198 | <0.001 | 1.108–1.241 | 8.1%, <0.0001 | 0.337 |

| Endometriosis stage | |||||||

| All stages | 5 | 1.297 | 1.165–1.445 | <0.001 | 0.918–1.832 | 95.5%, 0.0124 | <0.001 |

| Mode of ART | |||||||

| IVF/ICSI | 3 | 1.316 | 1.081–1.604 | 0.006 | 0.613–2.826 | 96.4%, 0.0214 | <0.001 |

| Uncategorized | 3 | 1.275 | 1.101–1.477 | 0.001 | 0.718–2.263 | 88.3%, 0.0122 | <0.001 |

| Low birth weight | |||||||

| Overall | 7 | 1.159 | 1.050–1.279 | 0.003 | 1.025–1.310 | 0%, 0 | 0.714 |

| Ethnicity | |||||||

| Caucasian | 2 | 1.098 | 0.945–1.276 | 0.223 | 0.105–11.019 | 8.0%, 0.0144 | 0.297 |

| Asian | 4 | 1.295 | 1.041–1.611 | 0.020 | 0.909–1.845 | 0%, 0 | 0.766 |

| Endometriosis stage | |||||||

| All stages | 3 | 1.159 | 1.044–1.286 | 0.006 | 0.922–1.456 | 0%, 0 | 0.476 |

| Others | 4 | 1.158 | 0.856–1.567 | 0.342 | 0.708–1.893 | 0%, 0 | 0.524 |

| Mode of ART | |||||||

| IVF/ICSI | 6 | 1.158 | 1.023–1.310 | 0.020 | 0.985–1.362 | 0%, 0 | 0.590 |

| Large for gestational age | |||||||

| Overall | 8 | 0.942 | 0.781–1.135 | 0.530 | 0.591–1.501 | 50.1%, 0.0298 | 0.051 |

| Ethnicity | |||||||

| Asian | 4 | 0.940 | 0.829–1.066 | 0.334 | 0.767–1.153 | 0%, 0 | 0.727 |

| Others | 4 | 0.809 | 0.462–1.416 | 0.457 | 0.137–4.776 | 74.8%, 0.2297 | 0.008 |

| Endometriosis stage | |||||||

| All stages | 5 | 0.872 | 0.622–1.224 | 0.429 | 0.336–2.263 | 70.3%, 0.0881 | 0.009 |

| Others | 3 | 0.998 | 0.839–1.187 | 0.984 | 0.682–1.461 | 0%, 0 | 0.843 |

| Mode of ART | |||||||

| IVF/ICSI | 4 | 0.940 | 0.829–1.066 | 0.334 | 0.767–1.153 | 0%, 0 | 0.727 |

| Uncategorized | 4 | 0.809 | 0.462–1.416 | 0.457 | 0.137–4.776 | 74.8%, 0.2297 | 0.008 |

| Ectopic pregnancy | |||||||

| Overall | 3 | 1.973 | 0.789–4.931 | 0.146 | 0.053–73.205 | 84.1%, 0.4870 | 0.002 |

| Ethnicity | |||||||

| Caucasian | 2 | 2.919 | 1.619–5.264 | <0.001 | 0.064–133.440 | 0%, 0 | 0.439 |

| Endometriosis stage | |||||||

| All stages | 3 | 1.973 | 0.789–4.931 | 0.146 | 0.053–73.205 | 84.1%, 0.4870 | 0.002 |

| Mode of ART | |||||||

| Uncategorized | 3 | 1.973 | 0.789–4.931 | 0.146 | 0.053–73.205 | 84.1%, 0.4870 | 0.002 |

| Stillbirth | |||||||

| Overall | 4 | 1.219 | 1.032–1.440 | 0.020 | 0.930–1.597 | 0%, 0 | 0.494 |

| Ethnicity | |||||||

| Caucasian | 2 | 1.007 | 0.741–1.369 | 0.966 | 0.137–7.376 | 0%, 0 | 0.765 |

| Others | 2 | 1.320 | 1.083–1.608 | 0.006 | 0.366–4.760 | 0%, 0 | 0.652 |

| Endometriosis stage | |||||||

| All stages | 4 | 1.219 | 1.032–1.440 | 0.020 | 0.930–1.597 | 0%, 0 | 0.494 |

| Mode of ART | |||||||

| IVF/ICSI | 2 | 1.148 | 0.930–1.419 | 0.199 | 0.292–4.517 | 0%, 0 | 0.331 |

| Uncategorized | 2 | 1.344 | 1.026–1.760 | 0.032 | 0.233–7.734 | 0%, 0 | 0.422 |

| Hypertensive disorders of pregnancy | |||||||

| Overall | 4 | 1.161 | 1.096–1.231 | <0.001 | 1.057–1.276 | 0%, 0 | 0.819 |

| Ethnicity | |||||||

| Others | 3 | 1.164 | 1.098–1.234 | <0.001 | 1.024–1.323 | 0%, 0 | 0.911 |

| Endometriosis stage | |||||||

| All stages | 4 | 1.161 | 1.096–1.231 | <0.001 | 1.057–1.276 | 0%, 0 | 0.819 |

| Mode of ART | |||||||

| IVF/ICSI | 2 | 1.174 | 1.079–1.277 | <0.001 | 0.680–2.026 | 0%, 0 | 0.369 |

| Uncategorized | 2 | 1.150 | 1.062–1.246 | 0.001 | 0.685–1.930 | 0%, 0 | 0.999 |

Pooled effect and subgroup analysis of the association between endometriosis and secondary adverse reproductive and perinatal outcomes.

ART, assisted reproductive technology; IVF, in vitro fertilization; ICSI, intracytoplasmic sperm injection.

Figure 5

![Four forest plots labeled A, B, C, and D show meta-analysis results with various studies listed by year. Each plot includes columns for log risk ratio (logRR), standard error of logRR (SE[logRR]), risk ratio (RR), confidence intervals (95%-CI), and weight percentage. The plotted data points indicate study results, with summary diamonds representing overall effect estimates. Heterogeneity statistics (I², τ², p-value) are provided for each plot. Panels A and B use a common effect model, while C uses a random effects model. Panel D also uses a common effect model.](https://www.frontiersin.org/files/Articles/1630529/xml-images/fmed-13-1630529-g005.webp)

Forest plots of the association between endometriosis and preeclampsia (A), postpartum hemorrhage (B), cesarean section (C), and low birth weight (D) in women undergoing assisted reproductive technology.

3.4.2 Postpartum hemorrhage

Endometriosis was significantly associated with an elevated risk of postpartum hemorrhage in the overall analysis (RR 1.310, 95% CI 1.198–1.432, 95% PI 1.154–1.486), with minimal heterogeneity detected (I2 = 0%, Tau2 = 0) (Table 3; Figure 5B). Subgroup analysis revealed a significant relationship in other ethnic groups (RR 1.321, 95% CI 1.202–1.452, 95% PI 1.073–1.626), whereas no such association was evident in Caucasian populations (RR 1.220, 95% CI 0.930–1.602, 95% PI 0.209–7.120). Notably, the elevated risk of postpartum hemorrhage remained consistent regardless of endometriosis stage (All stages: RR 1.318, 95% CI 1.192–1.458, 95% PI 1.119–1.552) and modes of ART (IVF/ICSI: RR 1.349, 95% CI 1.200–1.516, 95% PI 0.632–2.879; Uncategorized: RR 1.257, 95% CI 1.094–1.444, 95% PI 0.927–1.704) (Table 3; Supplementary Figure S8).

3.4.3 Cesarean section

Endometriosis was significantly associated with an increased risk of cesarean section in the overall analysis (RR 1.296, 95% CI 1.165–1.441, 95% PI 0.944–1.779), accompanied by substantial heterogeneity (I2 = 94.3%, Tau2 = 0.0123) (Table 3; Figure 5C). Subgroup analyses based on ethnicity, disease stage, and ART modality demonstrated consistent associations, reinforcing the robustness of this finding (all p < 0.05) (Table 3; Supplementary Figure S9).

3.4.4 Low birth weight

The meta-analysis identified a significant link between endometriosis and an increased risk of LBW (RR 1.159, 95% CI 1.050–1.279, 95% PI 1.025–1.310), with minimal heterogeneity across the included studies (I2 = 0%, Tau2 = 0) (Table 3; Figure 5D). Stratified analyses by ethnicity revealed that this relationship was significant among Asian populations (RR 1.295, 95% CI 1.041–1.611, 95% PI 0.909–1.845), whereas no evidence of association was observed in Caucasian cohorts (RR 1.098, 95% CI 0.945–1.276, 95% PI 0.105–11.019). Within all endometriosis stage and IVF/ICSI subgroups, the association remained consistent (all p < 0.05) (Table 3; Supplementary Figure S10).

3.4.5 Large for gestational age

No significant association was observed between endometriosis and LGA in the overall analysis (RR 0.942, 95% CI 0.781–1.135, 95% PI 0.591–1.501), accompanied by moderate heterogeneity (I2 = 50.1%, Tau2 = 0.0298) (Table 3; Figure 6A). Subgroup analyses based on ethnicity, endometriosis stage, and mode of ART consistently failed to detect any significant relationships (all p > 0.05) (Table 3; Supplementary Figure S11).

Figure 6

Forest plots of the association between endometriosis and large for gestational age (A), ectopic pregnancy (B), stillbirth (C), and hypertensive disorders of pregnancy (D) in women undergoing assisted reproductive technology.

3.4.6 Ectopic pregnancy

The overall analysis suggested no significant association between endometriosis and ectopic pregnancy (RR 1.973, 95% CI 0.789–4.931, 95% PI 0.053–73.205), with significant heterogeneity (I2 = 84.1%, Tau2 = 0.4870) (Table 3; Figure 6B). Ethnicity-specific subgroup analysis uncovered a significant association between endometriosis and increased ectopic pregnancy risk within Caucasian populations (RR 2.919, 95% CI 1.619–5.264, 95% PI 0.064–133.440), while no significant links were observed across subgroups defined by endometriosis stage or ART modality (all p > 0.05) (Table 3; Supplementary Figure S12).

3.4.7 Stillbirth

The overall analysis demonstrated a significant correlation between endometriosis and an elevated risk of stillbirth (RR 1.219, 95% CI 1.032–1.440, 95% PI 0.930–1.597), with negligible heterogeneity across studies (I2 = 0%, Tau2 = 0) (Table 3; Figure 6C). This association remained consistent among patients across all stages of endometriosis (RR 1.219, 95% CI 1.032–1.440, 95% PI 0.930–1.597). However, no significant relationship was identified in Caucasian populations or in subgroups undergoing IVF/ICSI (all p > 0.05) (Table 3; Supplementary Figure S13).

3.4.8 Hypertensive disorders of pregnancy

Endometriosis was found to be significantly linked to a higher risk of HDP in the pooled analysis (RR 1.161, 95% CI 1.096–1.231, 95% PI 1.057–1.276), with minimal heterogeneity observed (I2 = 0%, Tau2 = 0) (Table 3; Figure 6D). Subgroup analyses stratified by ethnicity, endometriosis stage, and mode of ART consistently supported this association (all p < 0.05) (Table 3; Supplementary Figure S14).

3.5 Sensitivity analysis and publication bias

We performed sensitivity analysis and publication bias test for the pooled results of adverse pregnancy outcomes which included ≥ 10 studies. Sensitivity analysis involved recalculating pooled RRs and their associated 95% CIs following the systematic exclusion of individual studies, allowing an evaluation of the influence of each study on the aggregated results. This approach confirmed that the omission of any single study did not materially alter the conclusions, underscoring the reliability and stability of the findings (Supplementary Figure S15). Publication bias was assessed using Begg’s and Egger’s tests, both of which revealed no evidence of significant bias across the included studies (all p > 0.05). The funnel plots were provided in Supplementary Figure S16.

4 Discussion

This study conducted a meta-analysis of cohort studies to explore the impact of endometriosis on adverse pregnancy and perinatal outcomes in women undergoing ART. The results demonstrated that endometriosis significantly affects several critical pregnancy and perinatal outcomes, including clinical pregnancy rate, live birth rate, preterm birth, placenta previa, postpartum hemorrhage, cesarean section, LBW, stillbirth, and HDP. However, no statistically significant associations were observed for certain outcomes, such as SGA, miscarriage, preeclampsia, LGA, and ectopic pregnancy. Subgroup analyses based on ethnicity, endometriosis stage, and mode of ART further explored the associations between endometriosis and the aforementioned adverse pregnancy outcomes across different subpopulations.

Our findings revealed that women with endometriosis had significantly lower clinical pregnancy rate and live birth rate after ART compared to women without endometriosis. This result aligns with previous studies (27, 42), suggesting that endometriosis may impair ART success by affecting embryo implantation rates and pregnancy maintenance (50). The reduced endometrial receptivity in women with endometriosis is likely associated with chronic inflammation, local immune dysregulation, and endometrial fibrosis (51–53). These pathological changes may hinder embryo implantation and early pregnancy maintenance. Additionally, ovarian function in women with endometriosis may be compromised, leading to reduced oocyte quality and, consequently, diminished embryonic developmental potential (5). Our subgroup analyses indicated that the association of endometriosis and lower clinical pregnancy and live birth rate was more pronounced in Caucasian populations but less evident in Asian populations, indicating that racial differences may play a role in the influence of endometriosis on ART outcomes. These disparities could be attributed to variations in genetic background, disease phenotypes, and ART treatment strategies across populations.

In terms of perinatal outcomes, endometriosis significantly increased the risks of preterm birth, placenta previa, LBW, and stillbirth. Notably, the elevated risk of preterm birth was consistently observed across most subgroups, suggesting that endometriosis may influence pregnancy duration through multiple mechanisms. The endometrial environment in women with endometriosis may exhibit chronic inflammation, fibrosis, and abnormalities in angiogenesis (54), which could impair placental function and fetal growth. Additionally, endometriosis may alter the structure and function of the myometrium, increasing uterine contractility and thereby triggering preterm labor (55). The significantly increased risk of placenta previa may be related to the abnormal frequency and amplitude of uterine contractions observed in women affected (12). Previous studies have shown that reduced endometrial receptivity in these patients may lead to abnormal embryo implantation sites, thus increasing the likelihood of placenta previa (56). Furthermore, the heightened risk of LBW may be associated with placental insufficiency and intrauterine growth restriction (57), further supporting the adverse effects of endometriosis on placental development and function. Impaired placental perfusion in women with endometriosis could result in intrauterine growth restriction (58). Additionally, preterm birth is a major contributor to LBW, and the higher incidence of preterm birth in women with endometriosis may indirectly increase the risk of LBW. Moreover, the elevated risk of stillbirth in our study may reflect the cumulative adverse effects of endometriosis on pregnancy. Although the incidence of stillbirth is relatively low, its severity necessitates closer monitoring of high-risk patients in clinical practice.

This study also found that endometriosis was significantly associated with increased risks of HDP, cesarean section, and postpartum hemorrhage. The increased risk of HDP may be attributed to the chronic inflammatory state, endothelial dysfunction, and abnormal angiogenesis observed in women with endometriosis (59). These pathophysiological mechanisms could lead to inadequate placental perfusion and dysregulated maternal vascular tone, thereby increasing the risk of HDP (60). The elevated risk of postpartum hemorrhage may be related to uterine contractility disorders and abnormal placental implantation in women with endometriosis (61). Additionally, endometriosis may lead to myometrial dysfunction, increasing the risk of hemorrhage during delivery (62). Previous studies have suggested that endometriosis may cause myometrial fibrosis and vascular abnormalities (63), which could impair uterine contraction and placental separation during delivery. Furthermore, the significantly higher cesarean section rate may be due to the increased incidence of pregnancy complications (e.g., placenta previa, preterm birth) in women with endometriosis, prompting clinicians to opt for cesarean section to mitigate delivery-related risks, which in turn increases the risk of postpartum hemorrhage.

Although this study identified significant associations between endometriosis and several adverse perinatal outcomes, no statistically significant relationships were observed for certain outcomes, including SGA, miscarriage, preeclampsia, LGA, and ectopic pregnancy. These findings may reflect the selective impact of endometriosis on different pregnancy outcomes. For instance, the lack of a significant association between endometriosis and SGA suggested that while placental function may be impaired in women with endometriosis (64), it may not be sufficient to markedly increase the risk of intrauterine growth restriction. Moreover, the occurrence of SGA is influenced by multiple factors, including genetic predisposition, maternal nutritional status, and other pregnancy complications (65–67). Similarly, although endometriosis may increase the risk of miscarriage through inflammation, immune dysregulation, and implantation failure (3, 68), no significant association was observed in this study. This finding may be attributed to the rigorous selection of high-quality embryos during ART, which could reduce the likelihood of miscarriage. It is important to note, however, that the lack of a statistically significant association does not necessarily imply the absence of a true relationship. The relatively small number of studies reporting these results, along with limited sample sizes and racial differences among study populations, may have reduced the ability to detect statistically significant associations. Furthermore, variations in endometriosis staging and modes of conception may have contributed to residual heterogeneity, complicating the interpretation of these findings. Future studies with larger sample sizes and more homogeneous cohorts are needed to determine whether the observed lack of significant associations reflects a true absence of effect. Additionally, future research should further investigate the potential impact of different phenotypes or stages of endometriosis on these adverse pregnancy outcomes.

This study has some limitations. First, significant heterogeneity was observed among the included studies, which may be related to differences in participant characteristics, endometriosis stage, and mode of ART. Although subgroup analyses and random-effects models were applied to partially address heterogeneity, residual confounding factors (such as maternal age) cannot be entirely ruled out, as some studies adjusted for common confounding factors while others did not or failed to report such adjustments. Second, the control groups varied across studies, with some utilizing fertile individuals, others including subfertile patients, or those experiencing infertility due to male factors as non-endometriotic controls. Nevertheless, the majority of studies accounted for these differences by either adjusting for or restricting variables such as age, parity, or the number of pregnancies. Third, this study did not consider specific endometriosis phenotypes (e.g., deep infiltrating, ovarian, or superficial endometriosis) or adenomyosis comorbidity, which often coexists with endometriosis and shares adverse reproductive and obstetric outcomes. Adenomyosis has been shown to negatively impact fertility and pregnancy outcomes, including increased risks of hypertensive disorders, threatened preterm labor and postpartum maternal complications (69). Furthermore, the lack of standardized ART protocols across existing studies further limits the comparability of results. Future research should investigate these phenotypes and comorbidities to better understand their distinct impacts on ART outcomes. Fourth, due to the lack of detailed differentiation of ART methods in most studies, the current analysis is unable to compare outcomes between IVF and ICSI. Similarly, the majority of studies did not differentiate between the types of embryo transfer performed (e.g., frozen embryo transfer and fresh embryo transfer), which limits the feasibility of conducting further subgroup analyses. Future research should focus on comparing adverse pregnancy outcomes among various types of ART and different embryo transfer methods.

5 Conclusion

In summary, this study demonstrates that endometriosis significantly impacts pregnancy and perinatal outcomes following ART treatment. Specifically, endometriosis is associated with reduced clinical pregnancy and live birth rates, as well as an increased risk of preterm birth, placenta previa, postpartum hemorrhage, cesarean section, LBW, stillbirth, and HDP. Clinicians should implement closer surveillance for placenta previa and HDP, with early ultrasound screening and regular blood pressure monitoring. Multidisciplinary care is essential to manage risks such as preterm birth and LBW. Future research should further investigate the pathophysiological mechanisms of endometriosis and its effects on pregnancy outcomes, with the aim of optimizing treatment strategies and improving pregnancy management for affected patients.

Statements

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author contributions

YW: Methodology, Writing – original draft, Data curation, Software, Formal analysis, Investigation. XX: Investigation, Writing – original draft, Formal analysis, Data curation. XW: Conceptualization, Validation, Supervision, Methodology, Writing – review & editing. CX: Writing – original draft, Investigation, Validation. TL: Methodology, Writing – original draft, Formal analysis.

Funding

The author(s) declared that financial support was not received for this work and/or its publication.

Conflict of interest

The author(s) declared that this work was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declared that Generative AI was not used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fmed.2026.1630529/full#supplementary-material

References

1.

Taylor HS Kotlyar AM Flores VA . Endometriosis is a chronic systemic disease: clinical challenges and novel innovations. Lancet. (2021) 397:839–52. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(21)00389-5,

2.

Zondervan KT Becker CM Koga K Missmer SA Taylor RN Viganò P . Endometriosis. Nat Rev Dis Primers. (2018) 4:9. doi: 10.1038/s41572-018-0008-5,

3.

Pirtea P Cicinelli E De Nola R de Ziegler D Ayoubi JM . Endometrial causes of recurrent pregnancy losses: endometriosis, adenomyosis, and chronic endometritis. Fertil Steril. (2021) 115:546–60. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2020.12.010,

4.

Tomassetti C D'Hooghe T . Endometriosis and infertility: insights into the causal link and management strategies. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol. (2018) 51:25–33. doi: 10.1016/j.bpobgyn.2018.06.002,

5.

Somigliana E Li Piani L Paffoni A Salmeri N Orsi M Benaglia L et al . Endometriosis and IVF treatment outcomes: unpacking the process. Reprod Biol Endocrinol. (2023) 21:107. doi: 10.1186/s12958-023-01157-8,

6.

Lalani S Choudhry AJ Firth B Bacal V Walker M Wen SW et al . Endometriosis and adverse maternal, fetal and neonatal outcomes, a systematic review and meta-analysis. Hum Reprod. (2018) 33:1854–65. doi: 10.1093/humrep/dey269,

7.

Breintoft K Arendt LH Uldbjerg N Glavind MT Forman A Henriksen TB . Endometriosis and preterm birth: A Danish cohort study. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. (2022) 101:417–23. doi: 10.1111/aogs.14336,

8.

Vercellini P Viganò P Bandini V Buggio L Berlanda N Somigliana E . Association of endometriosis and adenomyosis with pregnancy and infertility. Fertil Steril. (2023) 119:727–40. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2023.03.018,

9.

Velez MP Bougie O Bahta L Pudwell J Griffiths R Li W et al . Mode of conception in patients with endometriosis and adverse pregnancy outcomes: a population-based cohort study. Fertil Steril. (2022) 118:1090–9. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2022.09.015,

10.

Yu H Liang Z Cai R Jin S Xia T Wang C et al . Association of adverse birth outcomes with in vitro fertilization after controlling infertility factors based on a singleton live birth cohort. Sci Rep. (2022) 12:4528. doi: 10.1038/s41598-022-08707-x,

11.

Farland LV Stern JE Liu CL Cabral HJ Coddington CC , 3rd, DiopHet alPregnancy outcomes among women with endometriosis and fibroids: registry linkage study in Massachusetts. Am J Obstet Gynecol (2022) 226:829.e1–e14. Doi:doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2021.12.268

12.

Leone Roberti Maggiore U Ferrero S Mangili G Bergamini A Inversetti A Giorgione V et al . A systematic review on endometriosis during pregnancy: diagnosis, misdiagnosis, complications and outcomes. Hum Reprod Update. (2016) 22:70–103. doi: 10.1093/humupd/dmv045,

13.

Salmanov AG Artyomenko VV Rud VO Dyndar OA Dymarska OZ Korniyenko SM et al . Pregnancy outcomes after assisted reproductive technology among women with endometriosis in Ukraine: results a multicenter study. Wiad Lek. (2024) 77:1303–10. doi: 10.36740/WLek202407101,

14.

Vendittelli F Barasinski C Rivière O Bourdel N Fritel X . Endometriosis and risk of adverse pregnancy outcomes: a retrospective multicenter cohort study. Fertil Steril. (2025) 123:137–47. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2024.07.037,

15.

Muteshi CM Ohuma EO Child T Becker CM . The effect of endometriosis on live birth rate and other reproductive outcomes in ART cycles: a cohort study. Hum Reprod Open. (2018) 2018:hoy016. doi: 10.1093/hropen/hoy016,

16.

Horton J Sterrenburg M Lane S Maheshwari A Li TC Cheong Y . Reproductive, obstetric, and perinatal outcomes of women with adenomyosis and endometriosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Hum Reprod Update. (2019) 25:592–632. doi: 10.1093/humupd/dmz012,

17.

Nagase Y Matsuzaki S Ueda Y Kakuda M Kakuda S Sakaguchi H et al . Association between endometriosis and delivery outcomes: A systematic review and Meta-analysis. Biomedicine. (2022) 10:10. doi: 10.3390/biomedicines10020478,

18.

Breintoft K Pinnerup R Henriksen TB Rytter D Uldbjerg N Forman A et al . Endometriosis and risk of adverse pregnancy outcome: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Clin Med. (2021) 10:667. doi: 10.3390/jcm10040667,

19.

Moher D Liberati A Tetzlaff J Altman DG . Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. BMJ. (2009) 339:b2535. doi: 10.1136/bmj.b2535,

20.

Wells G Shea B O'Connell J . The Newcastle-Ottawa scale (NOS) for assessing the quality of nonrandomised studies in Meta-analyses. Ottawa Health Research Institute Web site. (2014) 7

21.

Stang A . Critical evaluation of the Newcastle-Ottawa scale for the assessment of the quality of nonrandomized studies in meta-analyses. Eur J Epidemiol. (2010) 25:603–5. doi: 10.1007/s10654-010-9491-z,

22.

Bowden J Tierney JF Copas AJ Burdett S . Quantifying, displaying and accounting for heterogeneity in the meta-analysis of RCTs using standard and generalised Q statistics. BMC Med Res Methodol. (2011) 11:41. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-11-41,

23.

IntHout J Ioannidis JP Rovers MM Goeman JJ . Plea for routinely presenting prediction intervals in meta-analysis. BMJ Open. (2016) 6:e010247. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2015-010247,

24.

Higgins JP Thompson SG . Quantifying heterogeneity in a meta-analysis. Stat Med. (2002) 21:1539–58. doi: 10.1002/sim.1186

25.

Begg CB Mazumdar M . Operating characteristics of a rank correlation test for publication bias. Biometrics. (1994) 50:1088–101. doi: 10.2307/2533446,

26.

Egger M Davey Smith G Schneider M Minder C . Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. BMJ. (1997) 315:629–34. doi: 10.1136/bmj.315.7109.629,

27.

Alson S Henic E Jokubkiene L Sladkevicius P . Endometriosis diagnosed by ultrasound is associated with lower live birth rates in women undergoing their first in vitro fertilization/intracytoplasmic sperm injection treatment. Fertil Steril. (2024) 121:832–41. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2024.01.023,

28.

Benaglia L Bermejo A Somigliana E Scarduelli C Ragni G Fedele L et al . Pregnancy outcome in women with endometriomas achieving pregnancy through IVF. Hum Reprod. (2012) 27:1663–7. doi: 10.1093/humrep/des054,

29.

Carusi DA Gopal D Cabral HJ Bormann CL Racowsky C Stern JE . A unique placenta previa risk factor profile for pregnancies conceived with assisted reproductive technology. Fertil Steril. (2022) 118:894–903. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2022.08.013,

30.

Fujii T Wada-Hiraike O Nagamatsu T Harada M Hirata T Koga K et al . Assisted reproductive technology pregnancy complications are significantly associated with endometriosis severity before conception: a retrospective cohort study. Reprod Biol Endocrinol. (2016) 14:73. doi: 10.1186/s12958-016-0209-2,

31.

Gebremedhin AT Mitter VR Duko B Tessema GA Pereira GF . Associations between endometriosis and adverse pregnancy and perinatal outcomes: a population-based cohort study. Arch Gynecol Obstet. (2024) 309:1323–31. doi: 10.1007/s00404-023-07002-y,

32.

Glavind MT Forman A Arendt LH Nielsen K Henriksen TB . Endometriosis and pregnancy complications: a Danish cohort study. Fertil Steril. (2017) 107:160–6. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2016.09.020,

33.

Gómez-Pereira E Burgos J Mendoza R Pérez-Ruiz I Olaso F García D et al . Endometriosis increases the risk of placenta previa in both IVF pregnancies and the general obstetric population. Reprod Sci. (2023) 30:854–64. doi: 10.1007/s43032-022-01054-2,

34.

González-Comadran M Schwarze JE Zegers-Hochschild F Souza MD Carreras R Checa M . The impact of endometriosis on the outcome of assisted reproductive technology. Reprod Biol Endocrinol. (2017) 15:8. doi: 10.1186/s12958-016-0217-2,

35.

Healy DL Breheny S Halliday J Jaques A Rushford D Garrett C et al . Prevalence and risk factors for obstetric haemorrhage in 6730 singleton births after assisted reproductive technology in Victoria Australia. Hum Reprod. (2010) 25:265–74. doi: 10.1093/humrep/dep376,

36.

Hjordt Hansen MV Dalsgaard T Hartwell D Skovlund CW Lidegaard O . Reproductive prognosis in endometriosis. A national cohort study. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. (2014) 93:483–9. doi: 10.1111/aogs.12373

37.

Lee P Zhou C Li Y . Endometriosis does not seem to be an influencing factor of hypertensive disorders of pregnancy in IVF / ICSI cycles. Reprod Biol Endocrinol. (2022) 20:57. doi: 10.1186/s12958-022-00922-5,

38.

Perkins KM Boulet SL Kissin DM Jamieson DJ . Risk of ectopic pregnancy associated with assisted reproductive technology in the United States, 2001-2011. Obstet Gynecol. (2015) 125:70–8. doi: 10.1097/aog.0000000000000584,

39.

Queiroz Vaz G Evangelista AV Almeida Cardoso MC Gallo P Erthal MC Pinho Oliveira MA . Frozen embryo transfer cycles in women with deep endometriosis. Gynecol Endocrinol. (2017) 33:540–3. doi: 10.1080/09513590.2017.1296945,

40.

Rombauts L Motteram C Berkowitz E Fernando S . Risk of placenta praevia is linked to endometrial thickness in a retrospective cohort study of 4537 singleton assisted reproduction technology births. Hum Reprod. (2014) 29:2787–93. doi: 10.1093/humrep/deu240

41.

Sharma S Bathwal S Agarwal N Chattopadhyay R Saha I Chakravarty B . Does presence of adenomyosis affect reproductive outcome in IVF cycles? A retrospective analysis of 973 patients. Reprod Biomed Online. (2019) 38:13–21. doi: 10.1016/j.rbmo.2018.09.014

42.

Sharma S RoyChoudhury S Bathwal S Bhattacharya R Kalapahar S Chattopadhyay R et al . Pregnancy and live birth rates are comparable in young infertile women presenting with severe endometriosis and tubal infertility. Reprod Sci. (2020) 27:1340–9. doi: 10.1007/s43032-020-00158-x,

43.

Sunkara SK Antonisamy B Redla AC Kamath MS . Female causes of infertility are associated with higher risk of preterm birth and low birth weight: analysis of 117 401 singleton live births following IVF. Hum Reprod. (2021) 36:676–82. doi: 10.1093/humrep/deaa283,

44.

Volodarsky-Perel A Ton Nu TN Mashiach R Berkowitz E Balayla J Machado-Gedeon A et al . The effect of endometriosis on placental histopathology and perinatal outcome in singleton live births resulting from IVF. Reprod Biomed Online. (2022) 45:754–61. doi: 10.1016/j.rbmo.2022.04.015,

45.

Wu J Yang X Huang J Kuang Y Chen Q Wang Y . Effect of maternal body mass index on neonatal outcomes in women with endometriosis undergoing IVF. Reprod Biomed Online. (2020) 40:559–67. doi: 10.1016/j.rbmo.2020.01.010

46.

Wu Y Yang R Lan J Lin H Jiao X Zhang Q . Ovarian endometrioma negatively impacts oocyte quality and quantity but not pregnancy outcomes in women undergoing IVF/ICSI treatment: A retrospective cohort study. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). (2021) 12:739228. doi: 10.3389/fendo.2021.739228,

47.

Yang P Wang Y Wu Z Pan N Yan L Ma C . Risk of miscarriage in women with endometriosis undergoing IVF fresh cycles: a retrospective cohort study. Reprod Biol Endocrinol. (2019) 17:21. doi: 10.1186/s12958-019-0463-1,

48.

Zhang X Chambers GM Venetis C Choi SKY Gerstl B Ng CHM et al . Perinatal and infant outcomes after assisted reproductive technology treatment for endometriosis alone compared with other causes of infertility: a data linkage cohort study. Fertil Steril. (2024). 123:846–855. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2024.12.007

49.

Dai L Deng C Li Y Zhu J Mu Y Deng Y et al . Birth weight reference percentiles for Chinese. PLoS One. (2014) 9:e104779. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0104779,

50.

Shi J Xu Q Yu S Zhang T . Perturbations of the endometrial immune microenvironment in endometriosis and adenomyosis: their impact on reproduction and pregnancy. Semin Immunopathol. (2025) 47:16. doi: 10.1007/s00281-025-01040-1,

51.

Lessey BA Kim JJ . Endometrial receptivity in the eutopic endometrium of women with endometriosis: it is affected, and let me show you why. Fertil Steril. (2017) 108:19–27. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2017.05.031,

52.

Cheloufi M Kazhalawi A Pinton A Rahmati M Chevrier L Prat-Ellenberg L et al . The endometrial immune profiling may positively affect the Management of Recurrent Pregnancy Loss. Front Immunol. (2021) 12:656701. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2021.656701,

53.

Pathare ADS Loid M Saare M Gidlöf SB Zamani Esteki M Acharya G et al . Endometrial receptivity in women of advanced age: an underrated factor in infertility. Hum Reprod Update. (2023) 29:773–93. doi: 10.1093/humupd/dmad019,

54.

Zhu S Wang A Xu W Hu L Sun J Wang X . The heterogeneity of fibrosis and angiogenesis in endometriosis revealed by single-cell RNA-sequencing. Biochim Biophys Acta Mol basis Dis. (2023) 1869:166602. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2022.166602,

55.

Huang M Li X Guo P Yu Z Xu Y Wei Z . The abnormal expression of oxytocin receptors in the uterine junctional zone in women with endometriosis. Reprod Biol Endocrinol. (2017) 15:1. doi: 10.1186/s12958-016-0220-7,

56.

Sorrentino F Dep M Falagario M D'Alteri OM Diss A Pacheco LA et al . Endometriosis and adverse pregnancy outcome. Minerva Obstet Gynecol. (2022) 74:31–44. doi: 10.23736/s2724-606x.20.04718-8

57.

Damhuis SE Ganzevoort W Gordijn SJ . Abnormal fetal growth: small for gestational age, fetal growth restriction, large for gestational age: definitions and epidemiology. Obstet Gynecol Clin N Am. (2021) 48:267–79. doi: 10.1016/j.ogc.2021.02.002,

58.

Zur RL Kingdom JC Parks WT Hobson SR . The placental basis of fetal growth restriction. Obstet Gynecol Clin N Am. (2020) 47:81–98. doi: 10.1016/j.ogc.2019.10.008,

59.

Vest AR Cho LS . Hypertension in pregnancy. Curr Atheroscler Rep. (2014) 16:395. doi: 10.1007/s11883-013-0395-8

60.

Lin C Mazzuca MQ Khalil RA . Increased uterine arterial tone, stiffness and remodeling with augmented matrix metalloproteinase-1 and -7 in uteroplacental ischemia-induced hypertensive pregnancy. Biochem Pharmacol. (2024) 228:116227. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2024.116227,

61.

Abrams ET Rutherford JN . Framing postpartum hemorrhage as a consequence of human placental biology: an evolutionary and comparative perspective. Am Anthropol. (2011) 113:417–30. doi: 10.1111/j.1548-1433.2011.01351.x,

62.

Causa Andrieu P Stewart K Chun R Breiland M Chamie LP Burk K et al . Endometriosis: a journey from infertility to fertility. Abdom Radiol (NY). (2025) 50:5405–21. doi: 10.1007/s00261-025-04935-7,

63.

Powell SG Sharma P Masterson S Wyatt J Arshad I Ahmed S et al . Vascularisation in deep endometriosis: a systematic review with narrative outcomes. Cells. (2023) 12. doi: 10.3390/cells12091318,

64.

Koninckx PR Ussia A Adamyan L Wattiez A Gomel V Martin DC . Pathogenesis of endometriosis: the genetic/epigenetic theory. Fertil Steril. (2019) 111:327–40. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2018.10.013,

65.

Ambreen S Yazdani N Alvi AS Qazi MF Hoodbhoy Z . Association of maternal nutritional status and small for gestational age neonates in peri-urban communities of Karachi, Pakistan: findings from the PRISMA study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. (2024) 24:214. doi: 10.1186/s12884-024-06420-3,

66.

Stalman SE Solanky N Ishida M Alemán-Charlet C Abu-Amero S Alders M et al . Genetic analyses in small-for-gestational-age newborns. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. (2018) 103:917–25. doi: 10.1210/jc.2017-01843

67.

Wang P Yu Z Hu Y Li W Xu L Da F et al . BMI modifies the effect of pregnancy complications on risk of small- or large-for-gestational-age newborns. Pediatr Res. (2025) 97:301–10. doi: 10.1038/s41390-024-03298-x,

68.

Tomassetti C Meuleman C Pexsters A Mihalyi A Kyama C Simsa P et al . Endometriosis, recurrent miscarriage and implantation failure: is there an immunological link?Reprod Biomed Online. (2006) 13:58–64. doi: 10.1016/s1472-6483(10)62016-0,

69.

Giorgi M Raimondo D Pacifici M Bartiromo L Candiani M Fedele F et al . Adenomyosis among patients undergoing postpartum hysterectomy for uncontrollable uterine bleeding: a multicenter, observational, retrospective, cohort study on histologically-based prevalence and clinical characteristics. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. (2024) 166:849–58. doi: 10.1002/ijgo.15452,

Summary

Keywords

endometriosis, assisted reproductive technology, adverse pregnancy outcomes, preterm birth, placenta previa, meta-analysis

Citation

Wei Y, Xiao X, Wu X, Xie C and Li T (2026) Association between endometriosis and adverse reproductive and perinatal outcomes in women undergoing assisted reproductive technology: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Front. Med. 13:1630529. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2026.1630529

Received

17 May 2025

Revised

14 November 2025

Accepted

12 January 2026

Published

28 January 2026

Volume

13 - 2026

Edited by

Hong Zhang, Second Affiliated Hospital of Soochow University, China

Reviewed by

Lingqiong Meng, University of Arizona, United States

Matteo Giorgi, Ospedale del Valdarno, Italy

Updates

Copyright

© 2026 Wei, Xiao, Wu, Xie and Li.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Xixi Wu, 946453461@qq.com

†These authors have contributed equally to this work and share first authorship

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.