Abstract

Introduction:

Atopic dermatitis (AD) is a chronic inflammatory skin disease driven by skin-homing memory T cells. Recent evidence suggests that a subset of tissue-resident memory T (Trm) cells can exit tissues and recirculate as ex-Trm cells.

Methods:

Peripheral blood memory T cell subpopulations were analyzed in adults with AD, stratified by disease severity, using multiparametric flow cytometry. CD4+ and CD8+ memory subsets and the skin-homing markers CLA, CCR4, and CCR10 were evaluated.

Results:

Overall CD4+ and CD8+ memory T cell distributions were preserved. AD patients showed expansion of CD4+ central memory T cells expressing CLA, CCR4, and CCR10. Most notably, a circulating population of CD8+ ex-Trm cells co-expressing CLA, CCR4, and CCR10 was increased in moderate-to-severe disease and correlated positively with clinical severity. No comparable expansion was observed for CD4+ ex-Trm cells.

Discussion:

Circulating CD8+ ex-Trm cells with skin-homing properties may contribute to AD progression by reseeding distant skin sites and sustaining inflammation, whereas CD4+ ex-Trm cells may remain preferentially retained within inflamed skin. These findings identify circulating CD8+ ex-Trm cells as potential biomarkers of disease severity and disease dissemination.

1 Introduction

Atopic dermatitis (AD) is a complex disease involving genetic predisposition, barrier dysfunction, immune activation, and environmental factors (1). AD is a heterogeneous condition, with multiple inflammatory pathways (primarily type 2) variably activated depending on race or ethnicity (2–6). Therefore, T cells are central to the pathogenesis of AD, not only during the effector phase, but also in the memory phase, where memory T cells play a key role in sustaining immune responses, recurrence, and chronicity of the disease (7).

Memory T cells are broadly classified into four major subpopulations—central memory (Tcm), effector memory (Tem), effector memory re-expressing CD45RA (Temra), and tissue-resident memory T cells (Trm)—a classification based on the expression of specific surface markers. Recent findings indicates that not all Trm cells remain permanently confined to peripheral tissues; some may exit their resident sites and re-enter the bloodstream. These so-called ex-Trm cells retain epigenetic imprints acquired during their time in barrier tissues but downregulate CD69 upon circulation (8–10).

Skin-homing T memory cells in AD are characterized by the expression of the Cutaneous Lymphocyte-Associated Antigen (CLA) and contribute to multiple aspects of AD, including pruritus, the abnormal type 2 response and, colonization and overgrowth of Staphylococcus aureus (S. aureus) (7). CLA interacts with E-selectin on cutaneous endothelial cells (7). The presence of CLA + memory T cells in peripheral blood (PB) has been proposed as a potential biomarker of AD (11, 12). Additionally, keratinocytes release C-C motif chemokine ligands (CCL) 17 and 27, whose receptors, C-C motif chemokine receptors (CCR) 4 and 10, respectively, are potential therapeutic targets and mediate T-cell skin homing/chemoattraction in the disease (12–14).

While CLA expression has been previously studied in memory T cells, the combined expression of multiple skin-homing and chemoattraction markers across different memory subsets remains poorly investigated and rarely correlated with disease severity (7, 11). Additionally, current evidence on ex-Trm cells remains limited, with few studies addressing their role in human disease (15). This gap is even more pronounced in dermatologic conditions, where studies on ex-Trm cells expressing skin-homing markers are scarce, and to date, virtually unexplored in the context of AD. These cells could potentially contribute to disease progression by reseeding distant skin sites and sustaining inflammatory activity.

Here, we characterize circulating memory T cell subpopulations in adult patients with AD, stratified by disease severity, with a special focus on expression of CLA, CCR10, and CCR4 (skin-homing markers) within these subsets, as well as on the potential existence of circulating ex-Trm cells and their association with disease severity.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Patients and samples

An analytical cross-sectional study was conducted to characterize memory T cell subpopulations in PB of adult patients with AD, stratified by disease severity and the expression of previously described skin-homing/chemoattraction surface markers. Participants (aged 18 to 65 years) were excluded if pregnant or breastfeeding; past or current history of cancer; other autoinflammatory/autoimmune diseases; immunodeficiencies; chronic pancreatitis/liver disease; antibiotic use within the previous 3 months; and any infectious disease within the past month. Patients were treatment-free prior to sample collection: no phototherapy or systemic immunosuppressive therapies (including corticosteroids, azathioprine, methotrexate, cyclosporine, or Janus kinase inhibitors) for at least 4 weeks, and no biological therapies for at least 12 weeks. Although this was not a clinical trial, the core outcome set stablished by the Harmonizing Outcome Measure for Eczema was used to assess patients’ clinical status. AD severity was defined using the Eczema Area and Severity Index (EASI), categorized as mild (< 7), moderate (7–21), or severe (> 21) (16, 17). Patient-reported outcomes were evaluated using the Patient-oriented Eczema Measure (POEM), the peak pruritus Numerical Rating Scale over the past 24 h (pp-NRS) and the Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI) (17). Other scores used were SCORing Atopic Dermatitis index (SCORAD), Investigator’s Global Assessment (IGA), Mean pruritus NRS and Visual Analog Scale (VAS) for sleep disturbance. Healthy controls had no personal or family history of AD or other Th2-related conditions (asthma, allergic rhinitis, eosinophilic esophagitis, allergic conjunctivitis, or urticaria), and no history of systemic, inflammatory or infectious skin diseases. This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. Ethical approval was obtained from the institutional ethics committee (HMC 2023040, minute number: 9, date: 05-19-2023) prior to participant enrollment. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants before sample collection and clinical data acquisition.

Peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) were isolated from 10 mL of sodium-heparinized PB samples using density gradient centrifugation with Histopaque®-1077, Sigma. All samples were processed within two hours of collection.

2.2 Flow cytometry

PBMCs were stained for viability using ViaKrome 638 (®-Beckman Coulter) and labeled with an 11-color panel of fluorochrome-conjugated monoclonal antibodies targeting CD3, CD4, CD8, CD45RA, CD62L, CD69, CD103, CLA, CCR4, and CCR10 (Supplementary Table 1). A median of 1 × 106 events per sample was acquired for analysis.

Data were acquired on a DxFLEX flow cytometer (Beckman Coulter, Brea, CA, United States) equipped with 3 lasers (405 nm, 488 nm, and 638 nm) using the standard configuration. Compensation was performed using single-stained PBMC samples, and critical plots were manually reviewed. List-mode data files (.fcs) were analyzed using Kaluza™ Analysis Software, version 2.3.1 (®-Beckman Coulter). Percentages, mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) and integrated mean fluorescence intensity (iMFI: percentage of cells positive for a marker x MFI) of each subpopulation were identified. The gating strategy is shown in Figure 1.

FIGURE 1

Memory T cell subpopulations were analyzed using multiparametric 11-color flow cytometry. CD3, CD4, and CD8 were used to identify total T cells and to distinguish CD4 + and CD8 + subsets. Within these, memory subsets were classified based on CD45RA and CD62L expression as follows: naïve (CD45RA + CD62L +), Tcm (CD45RA–CD62L +), Tem (CD45RA–CD62L–), and Temra (CD45RA + CD62L–). In the Tem subpopulation, expression of CD69 and CD103 was used to identify Trm (CD69 + CD103 +) and ex-Trm (CD69–CD103 +). In each memory subset, the expression of the skin-homing markers CLA, CCR10, and CCR4 was evaluated.

2.3 Statistical analysis

Categorical variables were summarized as frequencies and percentages, and continuous variables using central tendency and dispersion measures according to their distribution (assessed by Shapiro–Wilk test). Given the non-normal distribution of most variables, non-parametric analyses were applied. Group comparisons were performed using the Kruskal–Wallis test with Dunn’s post hoc correction. Associations with clinical severity scores were evaluated using Spearman’s rank correlation. For dichotomous variables, group differences were assessed using the Wilcoxon rank-sum test. Statistical significance was set at p < 0.05. Analyses were conducted using R version 4.3.2

3 Results

A total of 26 participants were included: 18 AD patients, stratified by severity into mild (n = 6), moderate (n = 7), and severe (n = 5) groups, and 8 healthy controls. Median age was 27 years (IQR: 10.8), with 50% of participants being female. No significant sociodemographic differences were observed between patients and controls, including marital status, education level, or socioeconomic status. Among AD patients, 77.8% reported a personal history of allergic rhinitis, 55.6% of asthma, 44.4% of allergic conjunctivitis and 16.7% of food allergies. No aeroallergen allergies were reported, and one patient had drug allergy history. There were no statistically significant differences in the prevalence of atopic comorbidities across severity subgroups (Table 1).

TABLE 1

| Variable* | Total AD (n = 18) |

Mild (n = 6) |

Moderate (n = 7) |

Severe (n = 5) |

Controls (n = 8) |

p-valueΨ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Female sex | 9 (50) | 4 (66.7) | 2 (28.6) | 3 (60) | 4 (50) | 0.56 |

| Age, median (IQR) | 27 (10.8) | 33 (24.2) | 27 (4) | 20 (26) | 27 (10.75) | 0.90 |

| Cesarean delivery | 3 (16.7) | 2 (33.3) | 1 (14.3) | 0 (0) | 4 (50) | 0.59 |

| Single marital status | 14 (77.8) | 4 (66.7) | 7 (100) | 3 (60) | 7 (87.5) | 0.27 |

| Secondary or higher education | 13 (72.22) | 4 (66.7) | 5 (71.4) | 4 (80) | 6 (75) | 0.57 |

| Middle socioeconomic status | 11 (61.1) | 6 (100) | 3 (42.9) | 2 (40) | 6 (75) | 0.18 |

| Comorbidities | ||||||

| Asthma | 9 (50) | 3 (50) | 4 (57.1) | 2 (40) | 0 (0) | 0.85 |

| Allergic rhinitis | 14 (77.8) | 5 (83.3) | 5 (71.4) | 4 (80) | 0 (0) | 0.87 |

| Allergic conjunctivitis | 8 (44.4) | 4 (66.7) | 1 (14.3) | 3 (60) | 0 (0) | 0.13 |

| Food allergy | 3 (16.7) | 0 (0) | 2 (28.6) | 1 (20) | 0 (0) | 0.26 |

| Aeroallergen allergy | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 |

| Drug allergy | 1 (5.56) | 0 (0) | 1 (14.3) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0.44 |

Sociodemographic characteristics and comorbidities.

*Data are presented as n (%) unless otherwise specified.

Ψ Chi-square, Fisher’s exact test, or ANOVA applied according to data distribution. AD, atopic dermatitis; ns, not significant.

Median AD onset age was 2 years (IQR: 6.8), with 55.6% of patients reporting disease onset before 5 years of age. Median disease duration was 23 years (IQR: 19.8), with no differences observed between severity groups. Exacerbations were more common in severe AD (80%) compared to mild and moderate (p = 0.01). Regarding clinical phenotypes, 55.6% of patients had classic flexural, and 27.8% exhibited the head and neck variant. Clinician-Oriented Measures increased significantly with disease severity. Median EASI scores were 1.85, 11.00, and 22.10 in mild, moderate, and severe patients, respectively (p < 0.001). Similar trends were observed for SCORAD (p < 0.001) and IGA (p < 0.001).

Patient-reported outcomes also reflected greater disease burden in severe cases. DLQI and sleep disturbance scores were significantly higher in severe AD compared to mild and moderate cases (p < 0.05). Regarding treatment history, 44.4% of patients had received systemic corticosteroids and 11.1% had used cyclosporine. Topical corticosteroids were in use by 94.4% of patients at the time of sampling. Tacrolimus use was more frequent in mild AD (66.7%) than in moderate (14.3%) or severe disease (0%), reaching statistical significance (p < 0.05) (Table 2).

TABLE 2

| Variableϕ | Total AD (n = 18) |

Mild (n = 6) |

Moderate (n = 7) |

Severe (n = 5) |

p-value⟐ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age at AD onset, median (IQR) | 2 (6.75) | 2 (5.25) | 1 (10.4) | 5 (4) | 0.83 |

| Onset before 5 years of age | 10 (55.6) | 4 (66.7) | 4 (57.1) | 2 (40) | 0.69 |

| Disease duration, median (IQR) | 23 (19.8) | 31.5 (30.8) | 21 (7) | 24 (8) | 0.80 |

| Flare | 5 (27.8) | 0 (0) | 1 (14.3) | 4 (80) | 0.01 |

| Classic phenotype | 10 (55.6) | 2 (33.3) | 5 (71.4) | 3 (60) | 0.63 |

| Head and neck phenotype | 5 (27.8) | 4 (66.7) | 1 (14.3) | 0 (0) | < 0.01 |

| SCORES | |||||

| EASI, median (IQR) | 10.8 (17.2) | 1.85 (2) | 11 (4.25) | 22.1 (8.8) | < 0.001 |

| DLQI, median (IQR) | 17.5 (9.5) | 12.5 (6.25) | 15 (9.5) | 22 (9) | 0.04 |

| POEM, median (IQR) | 21 (4.75) | 19.5 (9.75) | 21 (4) | 22 (2) | 0.23 |

| ppNRS, median (IQR) | 9 (1.75) | 8.5 (4) | 9 (2.5) | 9 (1.75) | 0.39 |

| SCORAD, median (IQR) | 38.7 (27.1) | 22.2 (8.39) | 40.1 (9.78) | 61.8 (0.54) | < 0.001 |

| IGA, median (IQR) | 3 (1.75) | 1.5 (1) | 3 (0) | 4 (0) | < 0.001 |

| Mean pruritus NRS, median (IQR) | 7.5 (2.75) | 6.5 (3.25) | 8 (3) | 8 (2) | 0.43 |

| Sleep disturbance VAS median (IQR) | 7 (5.12) | 3.5 (2.5) | 7 (3) | 9 (4.5) | 0.04 |

| Previous systemic treatments | |||||

| Systemic corticosteroids | 8 (44.4) | 3 (50) | 2 (28.6) | 3 (60) | 0.55 |

| Cyclosporine | 2 (11.1) | 0 (0) | 1 (14.3) | 1 (20) | 0.56 |

| Current topical treatments | |||||

| Topical corticosteroids | 17 (94.4) | 6 (100) | 7 (100) | 4 (80) | 0.27 |

| Tacrolimus | 5 (27.8) | 4 (66.7) | 1 (14.3) | 0 (0) | 0.03 |

Clinical characteristics and history of the disease.

ϕData are presented as n (%) unless otherwise specified.

⟐Kruskal-Wallis test was used. AD, atopic dermatitis; DLQI, Dermatology Life Quality Index; EASI, Eczema Area and Severity Index; IGA, Investigator’s Global Assessment; POEM, Patient-Oriented Eczema Measure; pp-NRS, peak pruritus Numeric Rating Scale; SCORAD, SCORing Atopic Dermatitis index; VAS, Visual Analog Scale; ns, not significant.

3.1 Total CD4+ and CD8+ T cell distribution remains unaltered in AD, but CLA+CCR4+CCR10+ CD8+ T cells are upregulated

Total lymphocytes and CD3+ T cells percentages were similar between patients with AD and healthy controls. Similarly, CD4+ and CD8+ T cells proportions showed no differences between groups, nor among AD severity subgroups. CLA expression in total CD8+ T cells did not differ between controls and patients, or by disease severity (Supplementary Figure 1). However, CLA+CCR10+CCR4+ CD8+ T cells percentage tended to be higher in patients, with significant increase in moderate-to-severe cases compared to mild AD (p < 0.05) (Figures 2A–D). In CD4+ T cells, CLA expression also showed no differences across groups. Although a similar distribution was observed in the CLA+CCR10+CCR4+ CD4+ subset, the differences did not reach statistical significance between patients and controls or among severity subgroups (Supplementary Figure 2).

FIGURE 2

CLA+CCR10+CCR4+ CD8+ T cells. (A) Proportion in healthy controls vs. AD patients. (B) Mild vs. moderate-to-severe AD. (C) Representative dot plot in healthy control; and (D) AD patient. Percentages represent the proportion of each subset within its respective gated parent population. *p < 0.05.

3.2 Among CD4+ memory T cell subsets, Tcm cells show pronounced alterations in skin-homing marker expression in AD

Naïve, Tcm and Tem CD4 + T cells proportions showed no differences between patients and controls or among AD severity subgroups. In contrast, Temra CD4 + T cells (p < 0.05) and Trm CD4 + T cells (p < 0.01) percentages were significantly higher in patients compared to controls, although no differences were observed among severity groups (Supplementary Figure 3).

No differences in CLA expression were observed between patients and controls, nor across AD severity subgroups, in naïve and Trm CD4+ T cell populations (Supplementary Figure 4). In contrast, CLA+ Tcm CD4+ T cells proportion was significantly higher in patients (p < 0.01), and also showed higher iMFI values (p < 0.001). This pattern remained consistent across AD severity subgroups, but the differences did not reach statistical significance (Figures 3A–D). CLA+ Tem CD4+ T cells (p < 0.001) and CLA+ Temra CD4+ T cells (p < 0.05) percentages were lower in patients compared to controls, without variation by severity (Supplementary Figure 4).

FIGURE 3

Tcm CLA+CD4+ T cells. (A) Proportion and (B) iMFI in healthy controls vs. AD patients. (C) Proportion and (D) iMFI by AD severity. Percentages represent the proportion of each subset within its respective gated parent population. *p < 0.05.

No differences were observed in CLA+CCR10+CCR4+ cells proportion within naïve, Tem, Temra, or Trm CD4+ T cell subsets between patients and healthy controls, nor across AD severity groups. In contrast, CLA+CCR10+CCR4+ cells percentage was significantly higher in Tcm CD4+ T cells from patients (p < 0.01), although this difference was not maintained when stratified by disease severity (Supplementary Figure 5).

3.3 CLA+CCR10+CCR4+ frequency and expression are reduced in ex-Trm CD4+ T Cells in AD

Ex-Trm CD4+ cells percentage showed no differences between patients and controls or among AD severity subgroups. Similarly, CLA+ ex-Trm CD4+ T cells proportion did not differ between groups. However, patients showed a significantly lower percentage of CLA+CCR10+CCR4+ ex-Trm CD4+ T cells compared to controls (p < 0.01), a finding that was also supported by iMFI analysis, which revealed reduced expression intensity in patients (p < 0.05). These changes were not associated or correlated with disease severity (Figures 4A–H). The frequency of ex-Trm CD4+CLA+CCR10+CCR4+ cells out of the total CD4 + T cells was 0.08, 0.08, and 0.05% in patients with mild, moderate, and severe disease, respectively, and 0.08% in healthy controls.

FIGURE 4

ex-Trm CD4+ T cells and skin-homing marker expression. (A) Proportion of total ex-Trm CD4+ T cells in healthy controls vs. AD patients; (B) by AD severity. (C) Proportion of CLA+ ex-Trm CD4+ T cells in controls vs. patients; (D) by AD severity. (E) Proportion of CLA+CCR10+CCR4+ ex-Trm CD4+ T cells in controls vs. patients. (F) iMFI of CLA+CCR10+CCR4+ ex-Trm CD4+ T cells in controls vs. patients. (G) Proportion of CLA+CCR10+CCR4+ ex-Trm CD4+ T cells by AD severity. (H) Spearman correlation between CLA+CCR10+CCR4+ ex-Trm CD4+ T cells and EASI score. Percentages represent the proportion of each subset within its respective gated parent population. *p < 0.05.

3.4 Minimal shifts in proportion and skin-homing profile of CD8+ Memory T cells subsets in AD

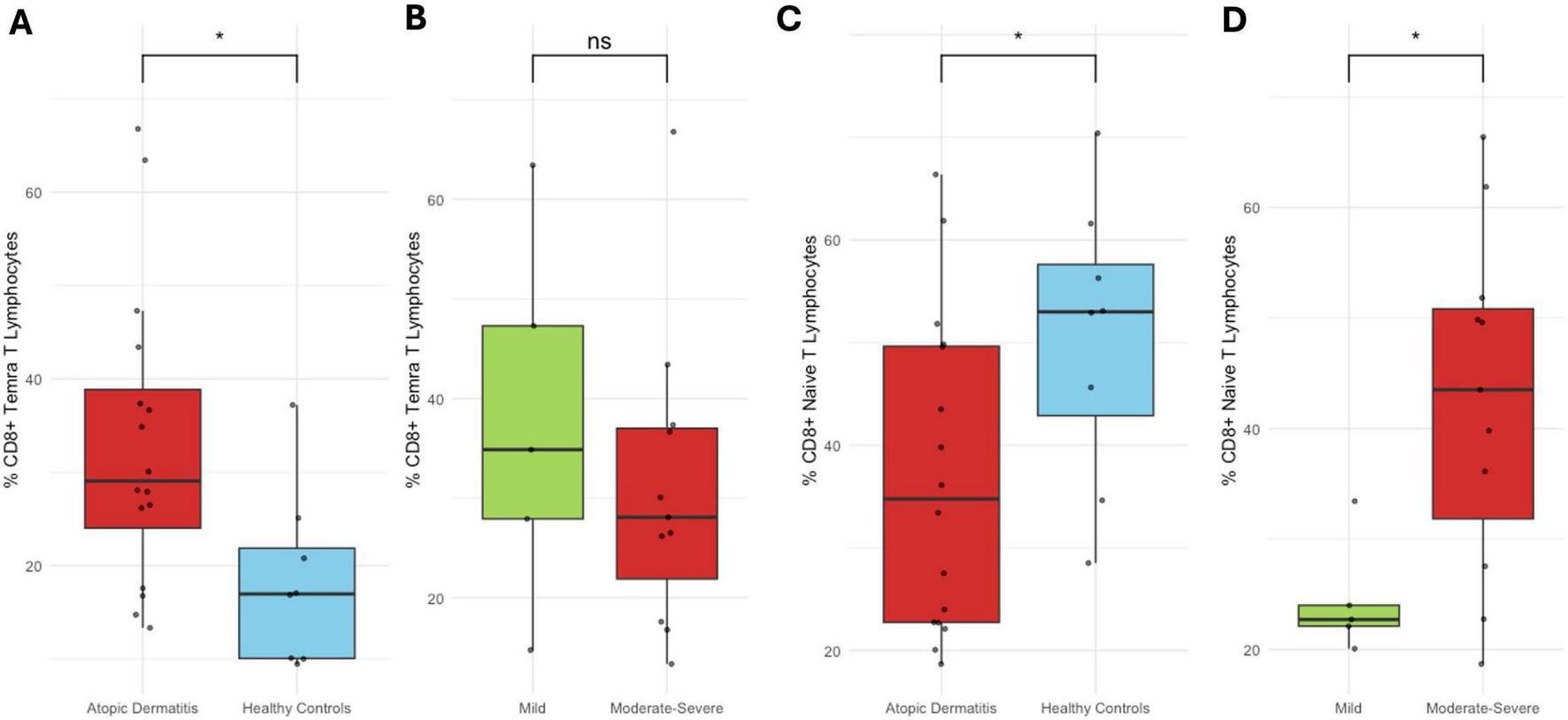

No significant differences were observed in Tcm, Tem, or Trm CD8+ T cells proportions between patients and healthy controls, nor across AD severity subgroups. CD8+ Temra cells percentage was significantly higher in patients than in controls (p < 0.05), although no variation was seen with disease severity (Supplementary Figure 6). Naïve CD8+ T cells proportion was lower in patients compared to controls (p < 0.05), but it increased significantly in moderate-to-severe AD compared to mild cases (p < 0.05) (Figures 5A–D).

FIGURE 5

CD8+ Temra and naïve T cell subsets. (A) Proportion of CD8+ Temra cells in healthy controls vs. AD patients; (B) by AD severity. (C) Proportion of CD8+ naïve T cells in controls vs. patients; (D) by AD severity. Percentages represent the proportion of each subset within its respective gated parent population. *p < 0.05.

No significant differences were observed in CLA+ CD8+ T cells proportion within the naïve, Tcm, Tem, Temra, or Trm subsets between patients and healthy controls, nor across AD severity groups (Supplementary Figure 7).

Across most CD8+ memory subsets—including Tcm, Tem, Temra, and Trm—no significant differences were found in CLA+CCR10+CCR4+ cells proportion between patients and controls or among AD severity groups. While CLA + CCR10 + CCR4 + naïve CD8+ T cells showed comparable percentages between healthy and AD individuals, a higher proportion was observed in moderate compared to mild AD, whereas values in severe AD were not significantly different. These differences, however, were not mirrored in iMFI analysis (Supplementary Figure 8).

3.5 CLA+CCR10+CCR4+ ex-Trm CD8+ T cells correlate with disease severity in AD

Ex-Trm CD8+ T cells proportion was similar between patients and healthy controls, with no significant variation across AD severity subgroups. Likewise, no differences were observed in CLA+ ex-Trm CD8+ T cells percentage between groups or by severity (Supplementary Figure 9).

No differences were observed in CLA+CCR10+CCR4+ ex-Trm CD8+ T cells percentage between patients and healthy controls. However, when analyzed by disease severity, a progressive increase in this subset was identified, with a significantly higher proportion in severe cases compared to mild AD (p < 0.05), and a higher proportion in severe compared to moderate cases, although this difference did not reach statistical significance. This upward trend was also supported by iMFI analysis (Figures 6A–C). Notably, CLA+CCR10+CCR4+ ex-Trm CD8+ T cells percentage and iMFI correlated positively with disease severity as measured by the EASI score (Spearman’s rho = 0.62, p < 0.05; and rho = 0.526, p < 0.05, respectively). The percentage of this subset also showed significant positive correlations with IGA (rho = 0.54, p < 0.05), SCORAD (rho = 0.539, p < 0.05), and DLQI (rho = 0.609, p < 0.05) (Figures 7A–E). In contrast, no correlations or associations were found with disease duration, age at onset, or patient age; the presence of clinical flares or Th2 comorbidities; disease phenotype or socioeconomic status; nor with prior use of systemic corticosteroids or cyclosporine, or current use of topical corticosteroids (Data not shown). The frequency of ex-Trm CD8+CLA+CCR10+CCR4+ cells out of the total CD8 + T cells was 0.01, 0.02, and 0.05% in patients with mild, moderate, and severe disease, respectively, and 0.02% in healthy controls.

FIGURE 6

CLA+CCR10+CCR4+ ex-Trm CD8+ T cells. (A) Proportion in healthy controls vs. AD patients; (B) by AD severity. (C) iMFI by AD severity. Percentages represent the proportion of each subset within its respective gated parent population. *p < 0.05.

FIGURE 7

Correlations between CLA+CCR10+CCR4+ ex-Trm CD8+ T cells and clinical severity scores. (A) Proportion vs. EASI. (B) iMFI vs. EASI. (C) Proportion vs. IGA. (D) vs. SCORAD; and (E) vs. DLQI. All correlations were calculated using Spearman’s rank test (p < 0.05). Percentages represent the proportion of each subset within its respective gated parent population.

4 Discussion

Trm were thought to be a memory T cell subset that permanently reside in non-lymphoid tissue, providing localized immunosurveillance (18). Evidence demonstrating that Trm can egress from their tissue of origin, enter circulation and seed other tissues has challenged this paradigm (15). Although initially described in parabiosis murine models, human research has confirmed the phenomena, especially in ex-Trm derived from the skin, mediating Th2 and Th17 responses in hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT) (19–21). Together, ex-Trm may help explain recall responses in several previously unexplained immune phenomena, including the dissemination of skin inflammation to distant cutaneous sites (15, 22).

Parabiosis experiments in mice have shown that 15–30% of circulating memory T cells originate from ex-Trm (22, 23). Studies in humanized mice and healthy human volunteers have confirmed the presence of a small but stable population of ex-Trm in PB, accounting for approximately 1% of circulating CD4 + T cells (24). In healthy individuals, circulating CLA + T cell compartment is thought to be maintained by a steady outflow of ex-Trm from the skin (24, 25). Upon leaving the tissue, ex-Trm downregulate CD69 and are characterized by CLA and CD103 expression (24). These cells retain their tissue-specific tropism and preserve much of the transcriptional identity of their resident counterparts (21). It has been suggested that CD4+ Trm have a greater capacity to exit the skin and re-enter the circulation compared to CD8+ Trm (22). However, in a gastrointestinal infection model, antigen reencounter drives CD8+ ex-Trm cell expansion, with these cells differentiating into Tcm and Tem, retaining their tissue-imprinted transcriptional profile, and preserving the capacity to return to the intestine, including distant sites (26).

Our findings align with emerging evidence that skin-Trm are not permanently retained in the tissue (15). We identified an expanded population of a subset of ex-Trm CD8 + T cells expressing CLA, CCR10, and CCR4 in severe AD patients. This population showed a positive correlation with EASI, IGA, SCORAD and DLQI scores, suggesting a potential role as a circulating biomarker of disease severity.

While previous studies have focused primarily on CD4 + Trm and ex-Trm dynamics in other diseases, our findings highlight the contribution of CD8 + ex-Trm cells with a skin-homing phenotype, which may reflect active immune trafficking from inflamed skin (20, 21, 24). Their enrichment in patients with more extensive and severe disease raises the possibility that these cells contribute to eczema dissemination to distant cutaneous areas, potentially playing a role in disease progression by exiting inflamed skin, reseeding distant sites, and establishing new immune memory foci. This could explain why newly affected areas in more severe patients tend to become recurrent inflammation sites, remaining susceptible to flare-ups once involved (27). Previous studies showing that CD8+ Trm cells are enriched in the skin of AD patients further support the relevance of this population in sustaining local inflammatory memory. Combined with our findings, this suggests that CD8+ ex-Trm cells may also disseminate this memory to distant skin sites as disease severity increases (28).

In patients with ankylosing spondylitis (AS), another chronic inflammatory disease, a pathogenic role for CD8+ ex-Trm cells has also been described (15). In this context, a population of CD8+ ex-Trm cells expressing β7 integrin, CD103, and CD49a—molecules associated with gut homing—was identified and found to be increased in both PB (≈ 0.9%) and synovial fluid (≈ 7.5%) of patients with AS. These cells produced TNFα, perforin, and IL-10, suggesting a functional effector phenotype with cytotoxic and regulatory features. Based on their phenotypic similarity at both the protein and transcriptomic levels to intestinal intraepithelial lymphocytes, the authors proposed that this population originates from the gut and traffics to the joint, supporting the hypothesis of a gut–joint axis as a driver of systemic inflammation in AS (29). Together, these findings illustrate the concept that CD8+ ex-Trm cells may be expanded and contribute to disease progression across tissues depending on the expression of tissue-specific homing receptors.

Although classic surface markers of senescence (CD28, CD27) were not included in our multicolor panel, the design allowed us to determine that ex-Trm CD8+ cells were not Temra; therefore, this population is not expected to be senescent. As previously described in the context of HSCT, Trm cells can persist in the skin through the expression of senescence-associated markers; however, upon stimulation, these markers are downregulated, and the proportions of cells producing effector cytokines are comparable to those of healthy skin-derived T cells, or they may become pathogenic and contribute to graft-versus-host disease (19, 21).

CD8+ T cells protect mammalian hosts from intracellular infections. Persistent antigen exposure by Herpes simplex virus (HSV), a frequent intracellular infection in AD patients, has been shown to influence Trm biology (30, 31). Murine studies demonstrate that re-stimulated Trm can undergo retrograde migration, re-enter the circulation, and give rise to Tcm and Tem cells while retaining Trm potential (26). Other models of recurrent cutaneous viral infection have revealed pathogen-specific CD8+ Trm at both primary and distal skin sites, with repeated infections driving stable, skin-wide Trm populations (31, 32). These findings support HSV as a plausible factor contributing to the generation of circulating ex-Trm CD8+ cells with skin-homing potential in AD. Although other pathogens frequently implicated in AD, such as Staphylococcus aureus, Candida, or Malassezia, may also contribute to ex-Trm formation due to their chronicity, frequency, and recurrence, their predominantly extracellular biology is more likely to favor the generation of CD4+ rather than CD8+ Trm (33).

In contrast, circulating ex-Trm CD4+ T cells did not exhibit the same behavior. This may be explained by two mechanisms: (1) CLA+CCR10+CCR4+ ex-Trm CD4+ T cells might not be expanded, even in inflamed skin; and (2), CD4+ T cells actively drive local inflammation and eczematous responses in AD, as the principal effector population they may be preferentially retained in the skin. Previous studies showing that CD4+ Trm cells are not enriched in the skin of AD patients—even in lesional areas—reinforce the first hypothesis suggesting a distinct role in the effector phase for CD4+ T cells including systemic recall, rather than maintenance and expansion of local memory (28). This interpretation is further supported by our findings, as well as by others, of CLA+ and CLA+CCR10+CCR4+ CD4+ Tcm cells increased frequency, consistent with a systemic memory profile (11, 34–36).

We acknowledge that we identified a very low-frequency population of circulating ex-Trm cells that nevertheless reached statistical significance in relation to disease severity. Although the biological significance of these cells remains to be established, their detection by flow cytometry indicates that they can be observed in AD and that they carry skin-homing markers associated with type 2 responses. Given their rarity and the absence of functional or clonal data, these results should be viewed as an initial step, and documenting their presence provides a necessary basis for future studies to determine their physiological and potential pathogenic roles using functional assays, transcriptomics, and other state-of-the-art techniques.

This study has some limitations. The cross-sectional design precludes assessment of temporal dynamics in immune alterations. The sample size may limit the generalizability of the findings; however, it is comparable to that of other mechanistic studies in AD and was sufficient to identify consistent patterns suggesting potential differences between patients and controls, as well as across severity groups, which might have reached statistical significance in a larger cohort (5, 37, 38). Flow cytometric characterization was confined to surface markers, without evaluation of intracellular markers, cytotoxic molecules, functional assays, or clonality analyses that could help define the potential clonal status and type 1/2/3 inflammatory profile of the identified lymphocytes, as well as their cytotoxic capacity and potential contribution to tissue damage in AD. The levels of plasma chemokines were not assessed, which would provide valuable insight into the systemic effects that skin-derived chemokines may exert on the subsets of memory lymphocytes expressing skin-homing receptors that we identified.

Notable strengths of this study include stringent patient selection criteria, enabling analysis of immune parameters in untreated individuals—providing a clearer view of disease physiology without the confounding effects of recent therapeutic interventions. Additionally, all participants underwent a comprehensive and detailed clinical evaluation, allowing for precise phenotypic and immunological correlations.

Future longitudinal studies should evaluate CLA+CCR10+CCR4+ ex-Trm CD8+ T cells dynamics during disease flaring, treatment response, or overall disease course. Simultaneous assessment of both compartments—skin and PB—could offer valuable insight into pathophysiology of these poorly characterized cells, and into their behavior between affected skin and circulation, in both CD4+ and CD8+ ex-Trm populations. Furthermore, functional assays or single-cell transcriptomic analyses of these cells may elucidate pathogenic roles, whether they represent valid therapeutic targets or biomarkers of disease severity in AD.

Finally, we identified a circulating CLA+CCR4+CCR10+ CD8+ ex-Trm subset, whose enrichment in more severe patients suggests a role in disease dissemination and progression in AD, highlighting these cells—largely overlooked in skin disease models and human studies—as potential biomarkers of disease severity and therapeutic targets.

Statements

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request, in accordance with ethical and data protection requirements.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by Hospital Militar Central institutional ethics committee: HMC 2023040, minute number: 9, date: 05-19-2023. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

MO-R: Funding acquisition, Writing – original draft, Investigation, Formal analysis, Conceptualization, Project administration, Data curation, Writing – review & editing, Methodology. MP: Writing – review & editing, Supervision, Methodology, Conceptualization. DB: Conceptualization, Supervision, Writing – review & editing, Methodology. CR-S: Supervision, Conceptualization, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declared that financial support was received for this work and/or its publication. This research and publication was funded by the Hospital Militar Central through an internal research call, code: 2023040 and Universidad El Bosque: UEB-2023-020.

Acknowledgments

Laura Díaz, for her contribution in processing the samples and standardization of the experiments.

Conflict of interest

The author(s) declared that this work was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declared that generative AI was not used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fmed.2026.1656289/full#supplementary-material

References

1.

Sroka-Tomaszewska J Trzeciak M . Molecular mechanisms of atopic dermatitis pathogenesis.Int J Mol Sci. (2021) 22:4130. 10.3390/ijms22084130

2.

Brunner P Guttman-Yassky E . Racial differences in atopic dermatitis.Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. (2019) 122:449–55. 10.1016/j.anai.2018.11.015

3.

Gittler J Shemer A Suárez-Fariñas M Fuentes-Duculan J Gulewicz K Wang C et al Progressive activation of T(H)2/T(H)22 cytokines and selective epidermal proteins characterizes acute and chronic atopic dermatitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. (2012) 130:1344–54. 10.1016/j.jaci.2012.07.012

4.

Noda S Suárez-Fariñas M Ungar B Kim S de Guzman Strong C Xu H et al The Asian atopic dermatitis phenotype combines features of atopic dermatitis and psoriasis with increased TH17 polarization. J Allergy Clin Immunol. (2015) 136:1254–64. 10.1016/j.jaci.2015.08.015

5.

Sanyal R Pavel A Glickman J Chan T Zheng X Zhang N et al Atopic dermatitis in African American patients is TH2/TH22-skewed with TH1/TH17 attenuation. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. (2019) 122:99–110.e6. 10.1016/j.anai.2018.08.024

6.

Chan T Sanyal R Pavel A Glickman J Zheng X Xu H et al Atopic dermatitis in Chinese patients shows TH2/TH17 skewing with psoriasiform features. J Allergy Clin Immunol. (2018) 142:1013–7. 10.1016/j.jaci.2018.06.016

7.

Nicolàs L Czarnowicki T Akdis M Pujol R Lozano-Ojalvo D Leung D et al CLA+ memory T cells in atopic dermatitis. Allergy. (2024) 79:15–25. 10.1111/all.15816

8.

Buggert M Price D Mackay L Betts M . Human circulating and tissue-resident memory CD8+ T cells.Nat Immunol. (2023) 24:1076–86. 10.1038/s41590-023-01538-6

9.

Künzli M Masopust D . CD4+ T cell memory.Nat Immunol. (2023) 24:903–14. 10.1038/s41590-023-01510-4

10.

Cossarizza A Chang H Radbruch A Abrignani S Addo R Akdis M et al Guidelines for the use of flow cytometry and cell sorting in immunological studies (third edition). Eur J Immunol. (2021) 51:2708–3145. 10.1002/eji.202170126

11.

Czarnowicki T Santamaria-Babí L Guttman-Yassky E . Circulating CLA+ T cells in atopic dermatitis and their possible role as peripheral biomarkers.Allergy. (2017) 72:366–72. 10.1111/all.13080

12.

Yoshie O Matsushima K . CCR4 and its ligands: from bench to bedside.Int Immunol. (2015) 27:11–20. 10.1093/intimm/dxu079

13.

Xiong N Fu Y Hu S Xia M Yang J . CCR10 and its ligands in regulation of epithelial immunity and diseases.Protein Cell. (2012) 3:571–80. 10.1007/s13238-012-2927-3

14.

Bissonnette R DuBois J Facheris P Del Duca E Kim M Correa Da Rosa J et al Clinical and molecular effects of oral CCR4 antagonist RPT193 in atopic dermatitis: a phase 1 study. Allergy. (2024) 79:924–36. 10.1111/all.15949

15.

Rodger B Stagg A Lindsay J . The role of circulating T cells with a tissue resident phenotype (ex-TRM) in health and disease.Front Immunol. (2024) 15:1415914. 10.3389/fimmu.2024.1415914

16.

Chopra R Vakharia P Sacotte R Patel N Immaneni S White T et al Severity strata for Eczema area and severity index (EASI), modified EASI, Scoring atopic dermatitis (SCORAD), objective SCORAD, atopic dermatitis severity index and body surface area in adolescents and adults with atopic dermatitis. Br J Dermatol. (2017) 177:1316–21. 10.1111/bjd.15641

17.

Williams H Schmitt J Thomas K Spuls P Simpson E Apfelbacher C et al The HOME Core outcome set for clinical trials of atopic dermatitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. (2022) 149:1899–911. 10.1016/j.jaci.2022.03.017

18.

Steinert E Schenkel J Fraser K Beura L Manlove L Igyártó B et al Quantifying memory CD8 T cells reveals regionalization of immunosurveillance. Cell. (2015) 161:737–49. 10.1016/j.cell.2015.03.031

19.

Strobl J Gail L Kleissl L Pandey R Smejkal V Huber J et al Human resident memory T cells exit the skin and mediate systemic Th2-driven inflammation. J Exp Med. (2021) 218:e20210417. 10.1084/jem.20210417

20.

de Almeida G Lichtner P Eckstein G Brinkschmidt T Chu C Sun S et al Human skin-resident host T cells can persist long term after allogeneic stem cell transplantation and maintain recirculation potential. Sci Immunol. (2022) 7:eabe2634. 10.1126/sciimmunol.abe2634

21.

Strobl J Pandey R Krausgruber T Bayer N Kleissl L Reininger B et al Long-term skin-resident memory T cells proliferate in situ and are involved in human graft-versus-host disease. Sci Transl Med. (2020) 12:eabb7028. 10.1126/scitranslmed.abb7028

22.

Marchesini Tovar G Gallen C Bergsbaken T . CD8+ tissue-resident memory T cells: versatile guardians of the tissue.J Immunol. (2024) 212:361–8. 10.4049/jimmunol.2300399

23.

Beura L Wijeyesinghe S Thompson E Macchietto M Rosato P Pierson M et al T Cells in nonlymphoid tissues give rise to lymph-node-resident memory T cells. Immunity. (2018) 48:327–38.e5. 10.1016/j.immuni.2018.01.015

24.

Klicznik M Morawski P Höllbacher B Varkhande S Motley S Kuri-Cervantes L et al Human CD4+CD103+ cutaneous resident memory T cells are found in the circulation of healthy individuals. Sci Immunol. (2019) 4:eaav8995. 10.1126/sciimmunol.aav8995

25.

Watanabe R Gehad A Yang C Scott L Teague J Schlapbach C et al Human skin is protected by four functionally and phenotypically discrete populations of resident and recirculating memory T cells. Sci Transl Med. (2015) 7: 279ra39. 10.1126/scitranslmed.3010302

26.

Fonseca R Beura L Quarnstrom C Ghoneim H Fan Y Zebley C et al Developmental plasticity allows outside-in immune responses by resident memory T cells. Nat Immunol. (2020) 21:412–21. 10.1038/s41590-020-0607-7

27.

Abuabara K Margolis D Langan S . The long-term course of atopic dermatitis.Dermatol Clin. (2017) 35:291–7. 10.1016/j.det.2017.02.003

28.

He H Suryawanshi H Morozov P Gay-Mimbrera J Del Duca E Kim H et al Single-cell transcriptome analysis of human skin identifies novel fibroblast subpopulation and enrichment of immune subsets in atopic dermatitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. (2020) 145:1615–28. 10.1016/j.jaci.2020.01.042

29.

Qaiyum Z Gracey E Yao Y Inman R . Integrin and transcriptomic profiles identify a distinctive synovial CD8+ T cell subpopulation in spondyloarthritis.Ann Rheum Dis. (2019) 78:1566–75. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2019-215349

30.

Gebhardt T Wakim L Eidsmo L Reading P Heath W Carbone F . Memory T cells in nonlymphoid tissue that provide enhanced local immunity during infection with herpes simplex virus.Nat Immunol. (2009) 10:524–30. 10.1038/ni.1718

31.

Hobbs S Nolz J . Targeted expansion of tissue-resident CD8+ T cells to boost cellular immunity in the skin.Cell Rep. (2019) 29:2990–7.e2. 10.1016/j.celrep.2019.10.126

32.

Jiang X Clark R Liu L Wagers A Fuhlbrigge R Kupper T . Skin infection generates non-migratory memory CD8+ T(RM) cells providing global skin immunity.Nature. (2012) 483:227–31. 10.1038/nature10851

33.

Clegg J Soldaini E Bagnoli F McLoughlin R . Targeting skin-resident memory T cells via vaccination to combat Staphylococcus aureus infections.Trends Immunol. (2021) 42:6–17. 10.1016/j.it.2020.11.005

34.

Santamaria Babi L Perez Soler M Hauser C Blaser K . Skin-homing T cells in human cutaneous allergic inflammation.Immunol Res. (1995) 14:317–24. 10.1007/BF02935627

35.

Antúnez C Torres M Mayorga C Cornejo-García J Santamaría-Babi L Blanca M . Different cytokine production and activation marker profiles in circulating cutaneous-lymphocyte-associated antigen T cells from patients with acute or chronic atopic dermatitis.Clin Exp Allergy. (2004) 34:559–66. 10.1111/j.1365-2222.2004.1933.x

36.

Czarnowicki T Malajian D Shemer A Fuentes-Duculan J Gonzalez J Suárez-Fariñas M et al Skin-homing and systemic T-cell subsets show higher activation in atopic dermatitis versus psoriasis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. (2015) 136:208–11. 10.1016/j.jaci.2015.03.032

37.

Wongvibulsin S Sutaria N Kannan S Alphonse M Belzberg M Williams K et al Transcriptomic analysis of atopic dermatitis in African Americans is characterized by Th2/Th17-centered cutaneous immune activation. Sci Rep. (2021) 11:11175. 10.1038/s41598-021-90105-w

38.

Esaki H Brunner P Renert-Yuval Y Czarnowicki T Huynh T Tran G et al Early-onset pediatric atopic dermatitis is TH2 but also TH17 polarized in skin. J Allergy Clin Immunol. (2016) 138:1639–51. 10.1016/j.jaci.2016.07.013

Summary

Keywords

atopic dermatitis, atopic eczema, CLA, memory T cells, memory T lymphocytes

Citation

Ordóñez-Rubiano MF, Parra M, Bautista D and Romero-Sánchez C (2026) Circulating ex-Trm CD8 + T cells with skin-homing/chemoattraction phenotype are associated with disease severity in atopic dermatitis. Front. Med. 13:1656289. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2026.1656289

Received

29 June 2025

Revised

03 January 2026

Accepted

08 January 2026

Published

09 February 2026

Volume

13 - 2026

Edited by

Oleg E. Akilov, University of Pittsburgh, United States

Reviewed by

Patrizia Fuschiotti, University of Pittsburgh, United States

Sunil Nagpal, GlaxoSmithKline, United States

Updates

Copyright

© 2026 Ordóñez-Rubiano, Parra, Bautista and Romero-Sánchez.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Maria F. Ordóñez-Rubiano, mfordonezr@unbosque.edu.co

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.