Abstract

Aim:

Labor pain represents a significant challenge for parturients during childbirth. Transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (TENS) is an effective analgesic modality. However, its efficacy and safety for intrapartum analgesia remain unclear. To address this knowledge gap, we performed a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials (RCTs) to comprehensively assess the analgesic effectiveness and safety profile of TENS during the first stage of labor.

Methods:

We searched databases from inception to October 17, 2024 and updated them to July 22, 2025. Paired researchers independently extracted data and assessed the risk of bias. All meta-analyses were performed via random effects models, and the GRADE approach was employed to evaluate the certainty of evidence.

Results:

We included 51 randomized controlled trials (10,038 participants, all females). Low evidence showed that compared with the blank control, parturients using TENS may experience more pain relief (WMD –1.98 cm, 95%CI -2.6 to −1.35 cm, the modelled RD 52, 95% CI 37 to 62%), parturients using TENS may shorten the duration of the first stage of labor (WMD –46.78 min,95% CI –61.32 to −32.25 min); compared with the epidural analgesia groups, parturients using TENS may shorten the duration of the first stage of labor (WMD-62.22 min, 95%CI -92.51 to −31.94 min).

Conclusion:

Compared with the blank control, TENS may reduce pain intensity and shorten the duration of the first stage of labor in parturients, with little to no difference in adverse events. When compared to epidural analgesia, TENS may shorten the duration of the first stage of labor, with very small differences observed in analgesic efficacy or adverse effects.

Systematic review registration:

https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/PROSPERO/view/CRD420251066439, identifier PROSPERO (CRD420251066439).

1 Introduction

Labor pain, which is primarily induced by uterine contractions and cervical dilation, represents one of the most intense pain experiences in a woman’s lifetime (1). Characterized by progressive intensification, it initially manifests as dull lower abdominal or lumbosacral discomfort, evolving into rhythmic and excruciating sharp pain as labor advances. The intensity of labor pain and the duration of labor are two critical clinical indicators during maternal delivery. Timely and effective analgesia is crucial for ensuring maternal safety, facilitating spontaneous vaginal delivery, and optimizing neonatal outcomes (2).

The following provides a description of Transcutaneous Electrical Nerve Stimulation (TENS): Its physiological basis encompasses (1) the Gate Control Theory, where stimulation of Aβ fibers inhibits nociceptive signal transmission (via Aδ and C fibers); (2) the release of endogenous opioids, elevating cerebrospinal fluid levels of β-endorphin; and (3) central nervous system inhibition via activation of descending pain inhibitory pathways. Its indications include conditions such as labor pain, low back pain, and neuropathic pain. Contraindications involve application over implanted electronic devices, the abdomen during pregnancy, the carotid sinus region, malignant tumor sites, and areas with bleeding tendencies. The most frequently reported side effects are skin irritation, manifested as erythema, pruritus, and discomfort beneath the electrodes. Key advantages are its non-invasive nature, safety, ease of administration, provision of immediate analgesia, and compatibility with other therapies. Its disadvantages include restricted efficacy against severe or deep-seated pain, significant inter-individual variability in therapeutic outcomes, and anatomical constraints on application. Epidemiologically, as a significant pain-relief modality, its utilization demonstrates an upward trend, with potential for reducing long-term healthcare expenditures. Compared to epidural analgesia, TENS is suitable for parturients who prioritize maintaining mobility, control, and a more natural birth experience. In contrast, epidural analgesia is indicated for those experiencing severe pain or those at high obstetric risk necessitating emergency cesarean section.

Currently, TENS is employed as a non-pharmacological approach for analgesia, with its non-invasive nature offering distinct clinical advantages (3). The review article by Lowe, titled “The Nature of Labor Pain” (4), systematically delineates the stages of labor, the characteristics and physiological mechanisms of pain, as well as analgesia strategies. However, the efficacy and safety of TENS for labor analgesia remain uncertain. The first stage of labor, the cervical dilation stage, extends from the onset of regular uterine contractions to complete cervical dilatation. Its analgesic significance lies in effectively blocking the pain of contractions, for which Transcutaneous Electrical Nerve Stimulation (TENS) can be employed. In contrast, the physiological focus of the second stage is fetal expulsion, where the pain transitions to somatic pain originating from the pelvic floor and perineum. Here, the analgesic goal shifts to balancing pain relief with the preservation of the parturient’s ability to push effectively, a balance often achieved using epidural analgesia. TENS is primarily indicated for the first stage and offers limited utility in the second stage, when investigating the analgesic efficacy of Transcutaneous Electrical Nerve Stimulation (TENS), the primary research focus is typically on the first stage of labor. This study aims to quantitatively evaluate the analgesic effects of TENS compared to blank control, and assess its benefits and limitations relative to epidural analgesia. The findings are expected to provide evidence-based guidance for clinical decision-making, particularly in resource-limited settings where the non-invasive characteristics of TENS may enhance its applicability.

2 Materials and methods

Our systematic review was conducted in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines (5) and was prospectively registered on PROSPERO (CRD420251066439).

2.1 Literature search

Researchers have developed database-specific search strategies, without language restrictions or publication status limitations, for Pubmed, EMBASE, Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL), Web of Science, Chinese National Knowledge Infrastructure (CNKI), VIP Database for Chinese Technical Periodicals, and Wan Fang, which were searched from inception to October 17, 2024 and updated to July 22, 2025 (Supplementary Table 1). We also reviewed previous systematic reviews and included other studies that have met the criteria. We systematically examined the reference lists of prior systematic reviews (6–8) and cross-verified all potentially eligible randomized controlled trials (RCTs), implementing individual exclusion assessments.

2.2 Literature screen and data extraction

A pair of researchers, DNY and XXL, and ZYC and YQL, independently screened the titles and abstracts using a unified standard, and then the full texts that met the criteria were selected. Standardized pretest forms, with comprehensive instructions were used to ensure consistent application across all research sites. Any discrepancies between researchers were resolved through group discussion or, when necessary, with the assistance of an arbitrator (ZYH) to ensure consensus.

We included the following trials: (1) naturally delivered, full-term pregnancy (≥37 weeks), singleton mothers, aged more than 18 years old; (2) on the basis of usual care, TENS vs. blank treatment, or TENS vs. epidural stimulation; (3) pain intensity or duration reduction, during the first stage of labor; (4) Parallel-group randomized controlled trial.

A pair of reviewers: DNY and XXL, ZYC and YQL, independently abstracted data from each eligible trial. We have collected the relevant information of the article, including the author’s name and publication year, country of origin, sample size, characteristics of the parturient, intervention and outcome indicators, etc. We extracted the change scores from the baseline to reflect the internal changes in individuals.

2.3 Risk of bias assessment

Reviewers (ZYH, DNY and XXL) independently assessed the risk of bias, via a modified Cochrane Risk of Bias Tool 1.0 (9, 10), including random sequence generation, allocation concealment, blinding of study participants, operators, data collectors, evaluators and analysts, incomplete outcome data (≥20% missing data was considered high risk of bias), and other potential sources of bias. The answer options for each question are “definitely or possibly” (low bias risk) or “definitely or possibly Not” (high bias risk). Disagreements among researchers are resolved through discussion, those that cannot be resolved are determined by a third party.

2.4 Data analysis

We computed relative risk (RR) with 95% confidence intervals for dichotomous outcomes, while weighted mean differences (WMD) with 95% CIs were derived for continuous variables. We converted all continuous result data to a common scale in each domain (11): (1) pain intensity to the 10 cm visual analogue scale (VAS) for pain, the minimal clinically important difference (MID) was 1 cm (12, 13). (2) Duration of the first stage of labor. Modeled values were computed to facilitate comparative interpretation of the results.

All meta-analyses were performed via a Der Simonian-Laird random-effects model, with statistical processing executed in STATA 17 (Stata Corp, College Station, TX, USA).”

We examined publication bias through the visual assessment of funnel plot asymmetry when 10 or more studies were included in the analysis (14). All comparisons were two-tailed using a threshold of p ≤ 0.05.

2.5 Certainty of evidence

The certainty of evidence for each outcome was evaluated via the GRADE (Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development, and Evaluation) methodology (15, 16). While randomized controlled trials initially receive high certainty ratings, downgrading may occur across five domains: risk of bias, consistency, directness, precision, and publication bias, potentially yielding moderate, low, or very low certainty assessments. Treatment effects were judged to be imprecise under two distinct conditions: (1) for pain outcomes, when the 95% confidence interval encompassed half of the minimal clinically important difference (MID); (2) for adverse events, when the 95% CI included the null effect value (Table 1).

Table 1

| Study ID | Intervention | Control | Funding | Country | Number of participants at baseline, n | Mean duration of gestational age (SD), weeks | Mean age (SD), years |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gao Y 2023(17) | TENS | Blank | NR | China | 160 | 39.7 (0.95) | 27.8 (2.22) |

| M. Movahedi 2022(64) | TENS | Blank | NR | Iran | 100 | 38.9 (0.81) | 29.9 (4.12) |

| Gao XX 2021(18) | TENS | Blank | NR | China | 220 | 39.2 (1.42) | 30.3 (4.08) |

| Yan J 2021(19) | TENS | Blank | NR | China | 286 | 39.7 (0.84) | 26.74 (2.79) |

| A. Njogu 2021(20) | TENS | Blank | governmental | China | 413 | 39.1 (0.89) | 29 (3.52) |

| Lei FY 2021(21) | TENS | Blank | NR | China | 140 | 39.7 (1.65) | 28.5 (4.69) |

| Peng LL 2021(22) | TENS | Blank | NR | China | 145 | 39.1 (1.3) | 27.8 (2.42) |

| Zhang XF 2020(23) | TENS | Blank | NR | China | 200 | NR | 28.37 (4.16) |

| Zhang LQ 2020(24) | TENS | Blank | NR | China | 86 | NR | 28.9 (3.44) |

| Li HY 2020(25) | TENS | Blank | governmental | China | 100 | 38.7 (1.13) | 29.6 (2.74) |

| Huang JZ 2020(26) | TENS | Blank | NR | China | 160 | 39.4 (0.96) | 28.7 (7.33) |

| Liu PP 2020(27) | TENS | Blank | NR | China | 186 | 38.7 (1.18) | 28 (1) |

| Jiang DM 2020(28) | TENS | EA | NR | China | 50 | 39.5 (0.56) | 29.6 (0.92) |

| Huang LY 2019(29) | TENS | EA | NR | China | 480 | NR | 26.4 (2.25) |

| Zhao ZP 2018(30) | TENS | Blank | NR | China | 92 | 38.2 (0.72) | 28.3 (3.34) |

| A. Baez-Suarez 2018(62) | TENS | Blank | NR | Spain | 63 | 39.5 (1.42) | 28.1 (5.51) |

| Lu L 2018(31) | TENS+EA | EA | governmental | China | 200 | NR | 28.2 (3.64) |

| Li L 2018(32) | TENS | Blank | governmental | China | 80 | 38.5 (1.49) | 29 (1.42) |

| A. Nyambura 2017 (33) | TENS | Blank | NR | China | 326 | 39.1 (0.89) | 29 (3.52) |

| Liu J 2016(34) | TENS | Blank | NR | China | 100 | 39 (1.14) | 27.4 (3.44) |

| TENS | EA | NR | China | 100 | 38.9 (1.1) | 27.6 (3.61) | |

| Xiao H 2015(35) | TENS+EA | EA | governmental | China | 40 | NR | NR |

| Li J 2015(36) | TENS | EA | government | China | 80 | NR | NR |

| TENS | Blank | governmental | China | 80 | NR | NR | |

| Cai XL 2015(37) | TENS | Blank | NR | China | 172 | NR | NR |

| TENS | EA | NR | China | 172 | NR | NR | |

| Xiao H 2015(38) | TENS + EA | EA | governmental | China | 40 | 39.3 (1.55) | 26.6 (2.27) |

| Li HY 2012(39) | TENS | Blank | NR | China | 60 | 38.6 (NR) | 28.4 (NR) |

| Xu MJ 2006 (39) | TENS | Blank | NR | China | 60 | 39.3 (0.64) | 29.1 (3.58) |

| TENS | EA | NR | China | 60 | 39.3 (0.7) | 28.8 (3.6) | |

| Su XJ 2001(41) | TENS | Blank | NR | China | 40 | 39.3 (0.5) | 25.8(0.96) |

| Yang X 2021(42) | TENS | Blank | NR | China | 60 | 40 (0.47) | 28(4.06) |

| An ZZ 2015(43) | TENS | Blank | NR | China | 60 | NR | NR |

| Cao JG 2025(44) | TENS | Blank | governmental | China | 136 | 39.1 (1.12) | 27.6 (5.84) |

| Wang L 2019(45) | TENS | Blank | NR | China | 64 | 39.2 (0.7) | 28.6 (4.3) |

| Xu JH 2022(46) | TENS | Blank | governmental | China | 60 | 39.1 (1.12) | 27.6 (5.84) |

| Song KK 2023(47) | TENS | Blank | governmental | China | 90 | 38.7 (0.95) | 30 (3.15) |

| He J 2020(48) | TENS | Blank | NR | China | 200 | 39.1 (1.1) | 28.5 (8) |

| Ma ZH 2018(49) | TENS | Blank | NR | China | 60 | 37.5 (3.81) | 27.5 (6.05) |

| Miao WJ 2020 (50) | TENS | EA | NR | China | 151 | 39.6 (0.7) | 27.5 (3.03) |

| Meng LK 2020(51) | TENS | Blank | NR | China | 130 | 38.6 (1.26) | 28.8 (4.27) |

| Han CP 2021(52) | TENS | EA | governmental | China | 200 | 38.5 (1.15) | 30.4 (3.3) |

| Zhao KL 2024(53) | TENS | Blank | governmental | China | 130 | 39.6 (0.91) | 27.1 (5.74) |

| Shi J 2002(54) | TENS | Blank | NR | China | 60 | NR | NR |

| Niu CY 2017(65) | TENS | Blank | NR | China | 400 | NR | 22.3 (4.63) |

| Liu Ye 2015(55) | TENS | EA | NR | China | 60 | 39.2 (0.76) | 27.8 (3.93) |

| TENS | Blank | NR | China | 60 | 39 (0.75) | 27.1 (3.9) | |

| QianJ 2025(56) | TENS | Blank | governmental | China | 60 | 40.2 (1.82) | 31.5 (1.62) |

| Miao Y 2025(57) | TENS | EA | governmental | China | 92 | NR | NR |

| Xu J 2024(58) | TENS | Blank | NR | China | 60 | NR | 30.3 (4.53) |

| Shi XL 2024(59) | TENS | Blank | governmental | China | 80 | 39.6 (1.03) | 26.4 (3.66) |

| TENS | EA | governmental | China | 80 | 39.6 (1.05) | 26.4 (3.64) | |

| Huang XZ 2019(66) | TENS | Blank | NR | China | 94 | 39.3 (0.72) | 28.8 (2.49) |

| R. Sulu 2022(61) | TENS | Blank | governmental | Turkey | 42 | 38.27 (0.55) | 22.02 (3.13) |

| Santana, L. S.2016(60) | TENS | Blank | NR | Brazil | 46 | NR | 20 (4) |

| Zahra MEHRI 2022(67) | TENS | Blank | NR | Iran | 130 | 39 (1.32) | 24.5 (4.1) |

| V. Rashtchi 2022(68) | TENS | Blank | NR | Iran | 80 | NR | 24(4.16) |

Baseline characteristics of included studies.

NR, not reported; TENS, transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation; EA, epidural analgesia.

3 Results

3.1 Literature screening

We screened 3,905 citations, and 51 RCTs (7,096 participants) were ultimately included. Workflow is shown in Supplementary Figure 1.

3.2 Characteristics of included studies

Forty-four studies were conducted in China (17–59), three in Iran (60), one in Spain (31), one in Turkey (61), and one in Brazil (60). All participants were adult females, with a full-term (≥37 weeks) singleton delivery. The median of the mean age of participants was 26.5 years (IQR 18 to 35 years). Pain intensity were evaluated in 36 trials (19, 21, 24–29, 31–33, 36–42, 62, 63). First-stage labor duration was assessed in 33 trials (17–31, 33, 34, 36, 37, 39, 40, 43–47, 54–57, 59, 64, 65). Forty-five trials compared TENS with a blank control (17–27, 30–34, 36–49, 51, 53–56, 62–65), and eleven trials compared TENS with epidural analgesia (28, 29, 34, 36, 37, 40, 50, 54, 55, 57, 59). The TENS parameters for each article were also recorded (Table 4).

3.3 Risk of bias

All 51 trials had at least one risk-of-bias domain: 33 trials (66%) adequately generated random sequences, 4 trials (8%) concealed allocation, 3 trials (6%) blinded participants, 1 trial (2%) blinded healthcare providers, 3 trials (6%) blinded each of the data collectors, outcome assessors, and data analysts, and 2 trials (4%) had ≥20% data missing in the trial report (Supplementary Table 2).

3.4 TENS vs. blank control

3.4.1 Pain intensity in the first stage of labor

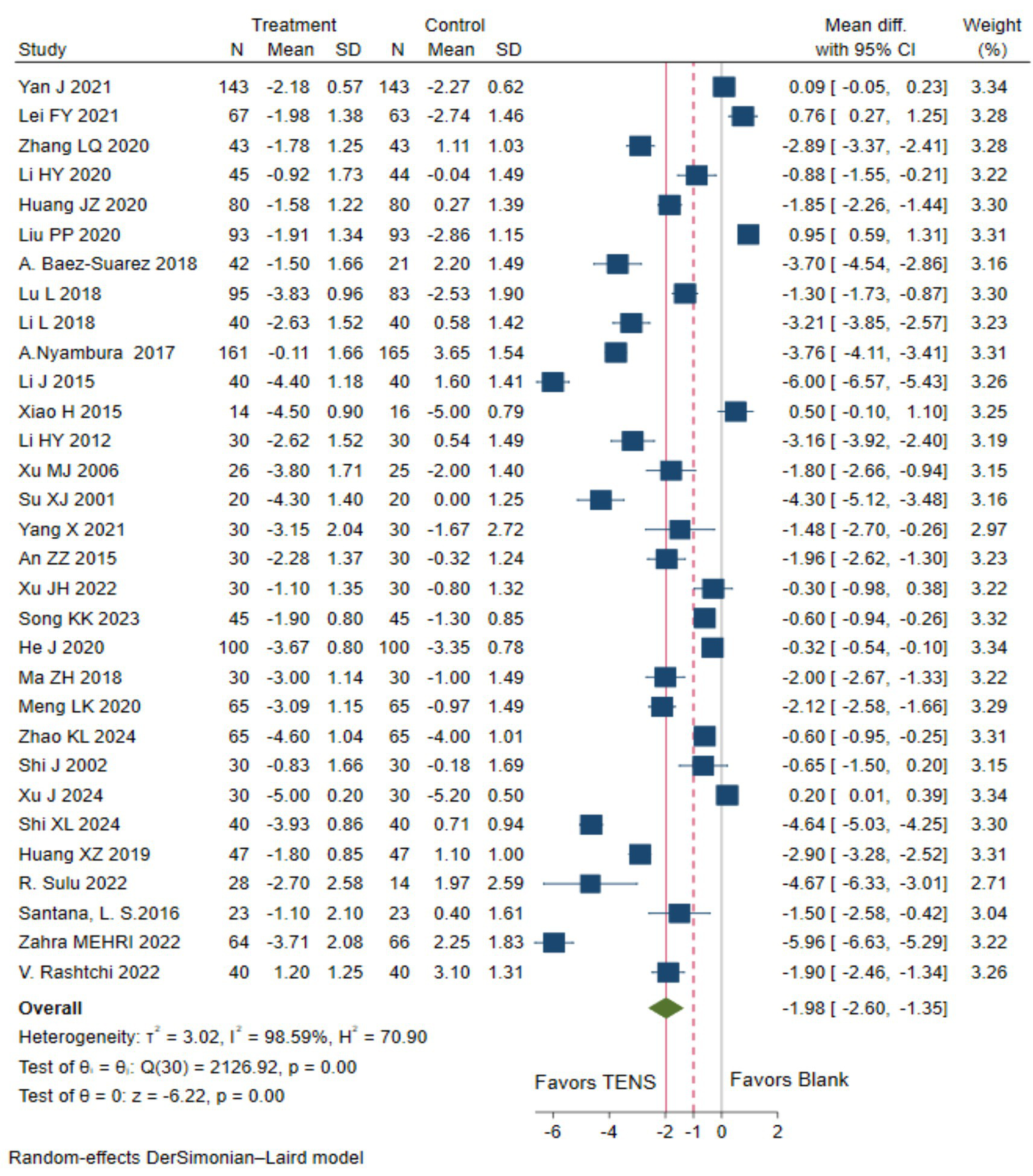

Low evidence (31 RCTs, 3,227 patients) showed that compared with the blank control, parturients using TENS may experience more pain relief (WMD-1.98 cm, 95%CI -2.6 to −1.35 cm, modelled RD 52, 95%CI 37 to 62%; Table 2 and Figure 1) (19, 21, 24, 25, 27, 31–33, 36, 38, 41–43, 46–49, 51, 62, 63).

Table 2

| No. of trials (No. of patients) |

Risk of bias | Inconsistency | Indirectness | Imprecision | Publication bias | Treatment association (95% CI) | Overall quality of evidence | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pain: 0–10 cm VAS for pain; lower is better; MID = 1 cm | ||||||||

| 31 (3,227) | Serious a | Not serious b | Not serious | Not serious | Serious c | Achieved at or above MID | Low | |

| TENS 79.6% | Control 27.9% | |||||||

| Modelled RD 0.52 (0.37,0.62) | ||||||||

| WMD –1.98 cm (−2.6, −1.35 cm) | ||||||||

| Duration of the first labor stage(minutes): shorter is better | ||||||||

| 30(4,092) | Serious a | Not serious b | Not serious | Not serious | Serious c | WMD -46.78 min (−61.32, −32.25 min) | Low | |

| Adverse effects | ||||||||

| 11 (1,278) | Serious a | Not serious, I2 = 27.5% |

Not serious | Not serious | Serious c | RR 0.51(0.38,0.69) | Low | |

Grade evidence profile of TENS versus the blank control for first-stage labor analgesia.

NA, not available; MID, minimal clinical important difference. a, high risk of bias in blinding; b, The observed high variance originated primarily from substantial dispersion in reported treatment effects across studies, rather than data sparsity; c, high risk in publication bias.

Figure 1

The pain intensity measured by the 10 cm VAS during the first stage of labor with TENS analgesia was compared to blank control.

3.4.2 Duration of the first stage of labor

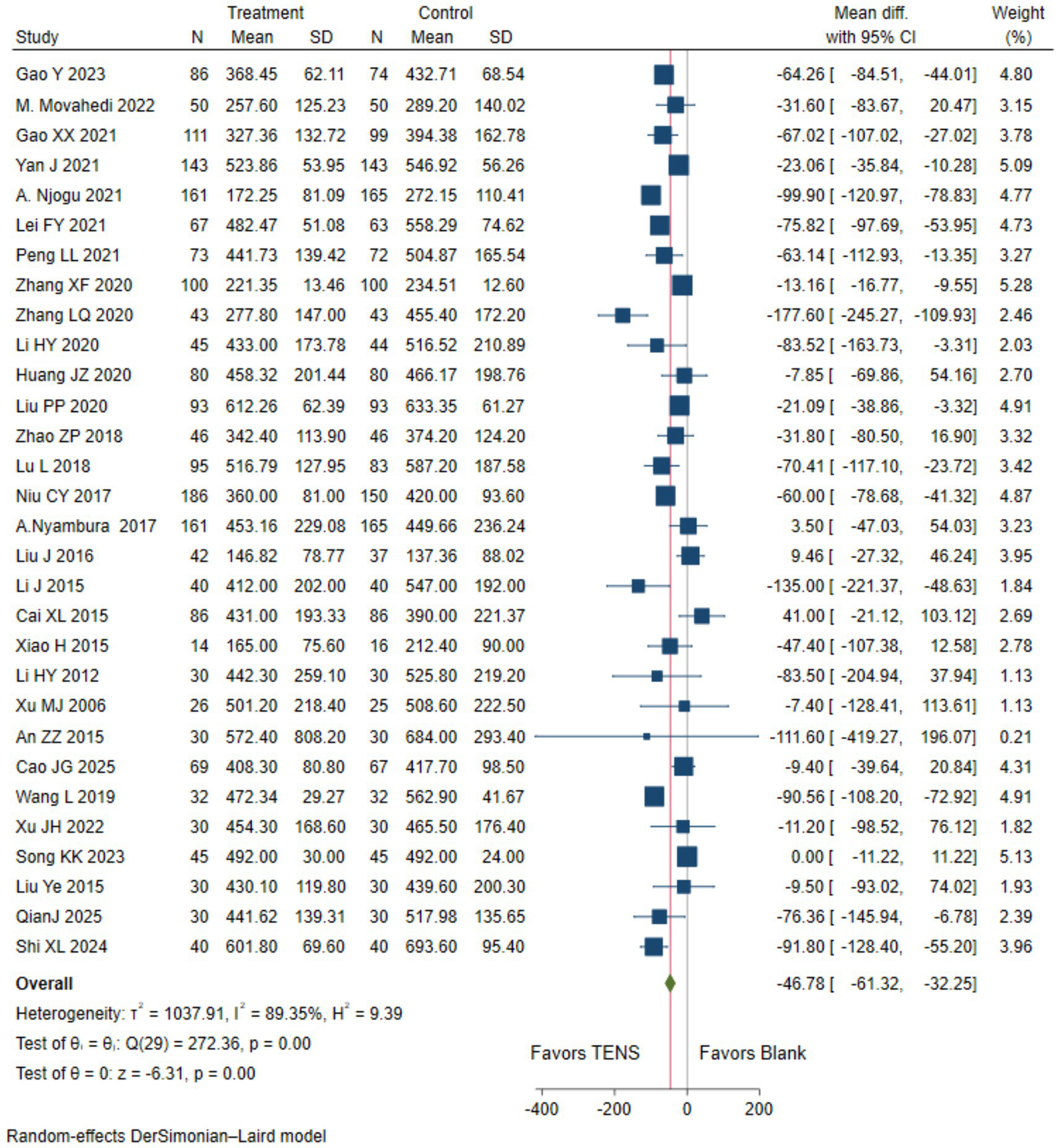

Low evidence (30 RCTs, 4,092 patients) reported that compared with blank control, parturients using TENS may shorten the duration of the first stage of labor (WMD-46.78 min,95%CI -61.32 to −32.25 min; Table 2 and Figure 2) (17–27, 30, 31, 33, 34, 36–40, 43–47, 55, 56, 58, 64, 65).

Figure 2

The duration of the first stage of labor with TENS analgesia was compared to blank control.

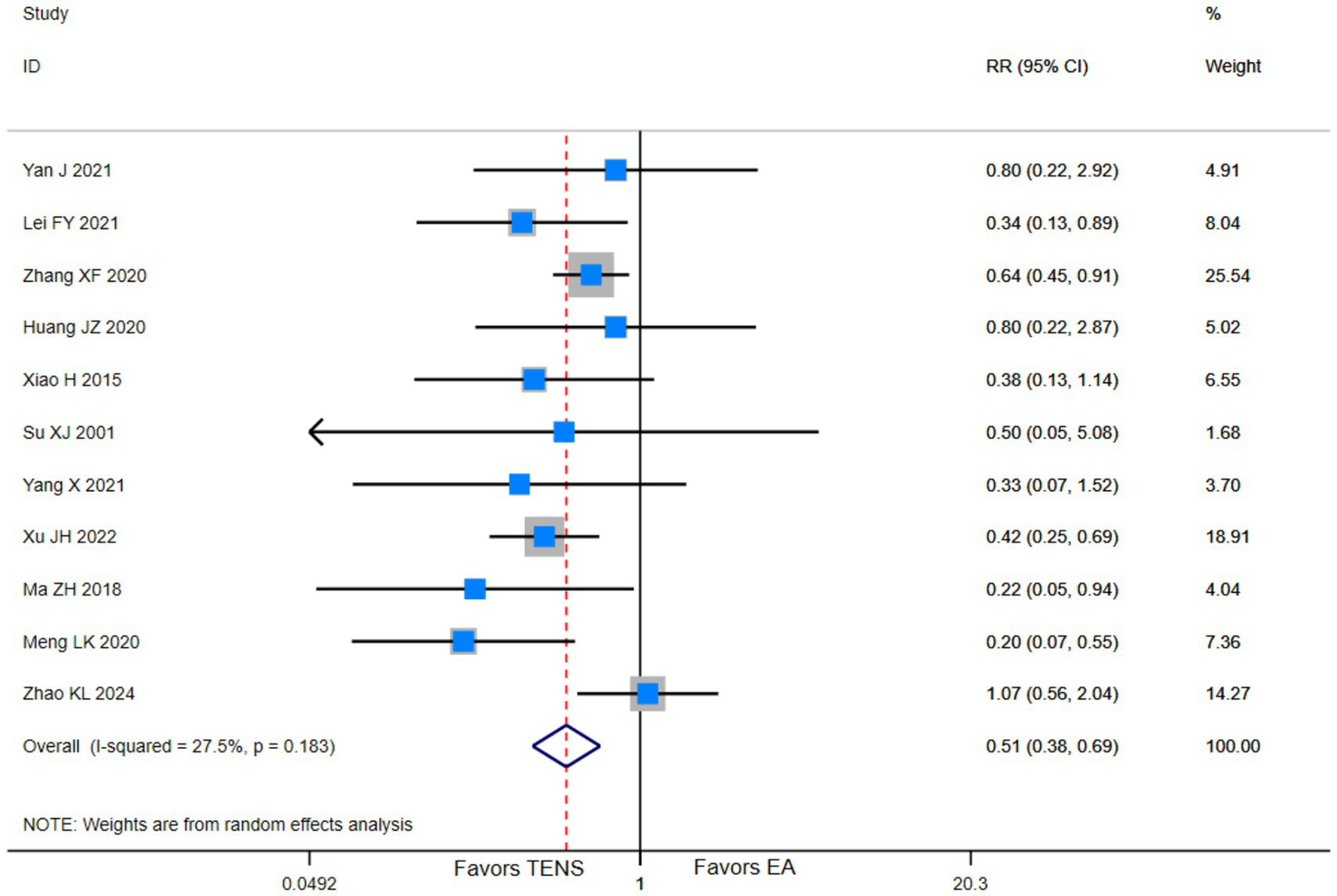

3.4.3 Adverse effects

Low evidence (11 RCTs,1,278 patients) suggests that compared with blank control, TENS may have little to no effect on reducing adverse effects in parturients during the first stage of labor (RR 0.51, 95% CI 0.38 to 0.69; Table 2 and Figure 3) (19, 21, 23, 26, 38, 41, 42, 46, 49, 51, 53).

Figure 3

Adverse events among parturients in the first stage of labor who received TENS versus blank control.

3.5 TENS vs. epidural analgesia

3.5.1 Pain intensity in the first stage of labor

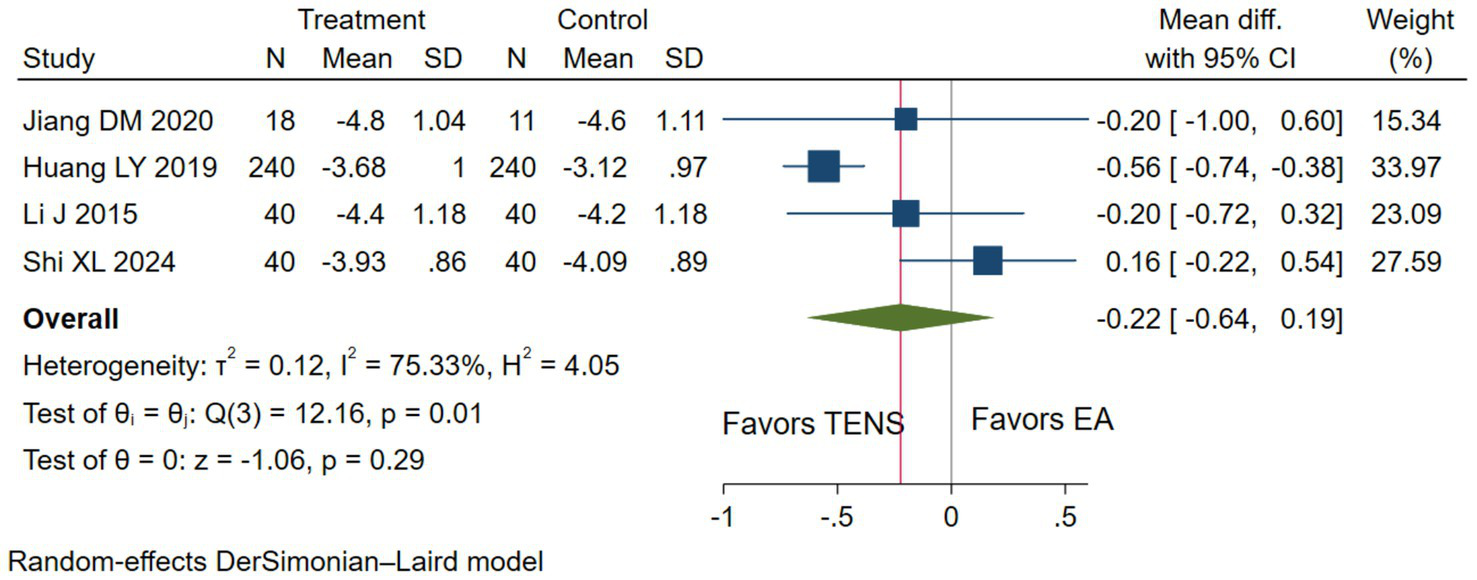

Low evidence (4 RCTs, 669 patients) showed that compared with epidural analgesia groups, parturients using TENS may have little to no difference in pain relief (WMD-0.22 cm, 95%CI-0.64 to-0.19 cm, modelled RD 0, 95%CI 0 to 0%; Table 3 and Figure 4) (28, 29, 36).

Table 3

| No. of trials (No. of patients) |

Risk of bias | Inconsistency | Indirectness | Imprecision | Publication bias | Treatment association (95% CI) | Overall quality of evidence | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pain: 0 to 10 cm VAS for pain; lower is better; MID = 1 cm | ||||||||

| 4 (669) | Serious a | Serious, I2 = 75.33% | Not serious | Not serious | NA | Achieved at or above MID | Low | |

| TENS 99.9% | Control 99.9% | |||||||

| Modelled RD 0.00 (0.00, 0.00) | ||||||||

| WMD -0.22 cm (−0.64, 0.19 cm) | ||||||||

| Duration of the first labor stage(minutes): shorter is better | ||||||||

| 8 (1,055) | Serious a | Serious, I2 = 65.53% | Not serious | Not serious | Not serious | WMD -62.22 min (−92.51, −31.94 min) | Low | |

| Adverse effects | ||||||||

| 3 (271) | Serious a | Not serious, I2 = 30.7% |

Not serious | Serious b | NA | RR 0.37(0.12,1.14) | Low | |

Grade evidence profile of TENS versus EA for first-stage labor analgesia.

NA, not available. a, high risk of bias in blinding; b, small sample size.

Table 4

| Study ID | Frequency | Stimulation site | Device type | Intensity | Duration |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gao Y 2023(17) | 2 Hz/100 Hz | Bilateral Zusanli (ST36), Sanyinjiao (SP6), Hegu (LI4) | Huatuo SDZ-II | 15 mA | Until the end of the second stage of labor |

| M. Movahedi 2022(64) | 100 Hz | Spinal nerve roots T10-L1 and S2-S4 | Not specified | 10–18 mA | 30 min |

| Gao XX 2021(18) | Self-adjusted | Bilateral Hegu (LI4), median nerve 4 cm proximal to wrist crease; proximal to wrist crease; highest point of iliac crest to lumbar spinous process | China Doule Group GT500 Series Seventh Generation Multi-functional DAOLE Doule Instrument | Mild muscle tremor induced | Self-adjusted usage time |

| Yan J 2021(19) | Not specified | Bilateral Zusanli (ST36), Hegu (LI4), Sanyinjiao (SP6) | Not specified | Gradually increased from 15 mA to obvious tremor | 20 min/session, twice, 2-h interval, Stop when the cervix is fully dilated. M |

| A. Njogu 2021(20) | Adjusted per tolerance | Hegu (LI4), Neiguan (PC6), paravertebral regions T10-L1 and S2-S4 | SRL998A Bio-feed TENS System | Peak current: 15 mA | From the onset of the active phase until the end of the second stage of labor |

| Lei FY 2021(21) | 2 Hz/100 Hz | Bilateral Hegu (LI4), Sanyinjiao (SP6), Zusanli (ST36) | Huatuo brand SDZ-II electronic acupuncture stimulator | Start at 15 mA, increase to slight muscle tremor and the pregnant woman’s tolerance level | Until the end of the second stage of labor |

| Peng LL 2021(22) | 2 Hz | Bilateral Hegu (LI4), Sanyinjiao (SP6), Zusanli (ST36) | Huatuo brand SDZ-II electronic acupuncture stimulator | Start at 15 mA, increase to painless | Every 2 h for 30 min, until active phase |

| Zhang XF 2020(23) | Not specified | T10-L1, S2-S4, Bilateral Hegu (LI4), Neiguan (PC6) | Lebeier BTX-9800D labor analgesia instrument | Start at 15 mA, increase to distinct tremor without pain | Until full cervical dilation |

| Zhang LQ 2020(24) | 2 Hz/100 Hz | Bilateral Hegu (LI4), Sanyinjiao (SP6), Zusanli (ST36) | SRL998 Youbeibei A type labor monitoring analgesia instrument | Start at 15 mA, increase to tolerable distinct tremor | Until the end of labor |

| Li HY 2020(25) | Not specified | Bilateral Hegu (LI4), Neiguan (PC6); Qihaishu (BL24), Guanyuanshu (BL26) | LABOUR-RI-Z TENS device | Not specified | Until entering the second stage |

| Huang JZ 2020(26) | 40–80 Hz | Bilateral Hegu (LI4), DaLing (PC8); Paravertebral region of lower back | Lebeier labor analgesia instrument | Frequency: 0–55 mA. Usually, during contractions it is 25–40 mA, and during the intervals between contractions it is 5–10 mA. | Until full cervical dilation |

| Liu PP 2020(27) | Not specified | T10-L1, S1-S4 | Fanlesheng non-invasive labor analgesia instrument | 15–50 mA, to slight muscle tremor and the pregnant woman’s tolerance level | Until the end of the second stage |

| Jiang DM 2020(28) | Not specified | Bilateral Hegu (LI4), Neiguan (PC6), T10–L1, L5–S4 | Not specified | Gradually increase to tolerance, stop at slight tremor | Not specified |

| Huang LY 2019(29) | 2 Hz | Bilateral Hegu (LI4), Sanyinjiao (SP6), Zusanli (ST36) | Not specified | Start at 15 mA, increase to distinct tremor without pain and the pregnant woman’s tolerance level | 30 min/session, 1 h interval, until active phase |

| Zhao ZP 2018(30) | Not specified | Both shoulders and lower back | “Lucky Baby” low-frequency nerve and muscle stimulator | It is advisable to use a mild tremor of the muscles and one that the pregnant woman can tolerate. | Until the end of the second stage |

| A. Baez-Suarez 2018(62) | 100 Hz (TENS1); 80–100 Hz (TENS2) | Paravertebral regions T10–L1 and S2–S4 | Cefar Rehab 2pro® TENS device | Individually titrated | 30 min/session, may be extended |

| Lu L 2018(31) | 2 Hz | Bilateral Hegu (LI4), Sanyinjiao (SP6), Zusanli (ST36) | Huatuo brand SDZ-II electronic acupuncture stimulator | Start at 15 mA, increase to distinct tremor without pain | 30 min/session, 1 h interval, until active phase |

| Li L 2018(32) | 2 Hz/100 Hz | Bilateral Hegu (LI4), Sanyinjiao (SP6), Zusanli (ST36) | Huatuo brand SDZ-II electronic acupuncture stimulator | Start at 15 mA, increase to distinct tremor and one that the pregnant woman can tolerate. | Until the end of the first stage |

| A. Nyambura 2017 (33) | Not specified | Bilateral Hegu (LI4), Neiguan (PC6); T10–L1, S2–S4 | SRL998A labor monitoring analgesia instrument | Initial <30 units, then adjusted to tolerance, throughout labor, intensity 30–60 units | Until the end of labor |

| Liu J 2016(34) | active phase: 100 Hz; incubation phase: 3–10–100 Hz | T10–L1, S1–S4 | KD-2A labor analgesia instrument | Not specified | 30 min/session, 2 h interval |

| 2 Hz | Bilateral Hegu (LI4), Sanyinjiao (SP6) | KD-2A transcutaneous nerve stimulator | Start at 15 mA, increase to distinct tremor without pain | 20 min/session, 2 h interval, until full dilation | |

| Xiao H 2015(35) | 1–100 Hz adaptive | Bilateral Hegu (LI4), Neiguan (PC6); T10–L1, L5–S4 | Sanrui SRL998A biofeedback labor analgesia doula instrument | Peak output ≤15 mA | Not specified |

| Li J 2015(36) | Not specified | Bilateral Hegu (LI4), Neiguan (PC6); T10–L1, L5–S4 | Not specified | Increase to tolerance, slight tremor | Not specified |

| 2 Hz | Bilateral Hegu (LI4), Sanyinjiao (SP6) | KD-2A transcutaneous nerve stimulator | Start at 15 mA, increase to distinct tremor without pain | 20 min/session, 2 h interval, until full dilation | |

| Cai XL 2015(37) | Not specified | Bilateral Hegu (LI4), median nerve 4 cm proximal to wrist crease; proximal to wrist crease; T10 (3 cm away from the left and right sides of the spine),5 cm vertically downward from the front side. | Not specified | Adjust to slight muscle tremor and tolerance | Stop after the second stage of labor or before a cesarean section; stop after the second stage of labor and before switching to a cesarean section to terminate natural childbirth |

| 2 Hz/100 Hz | Jiaji points (T10–L3), Ciliao points (S2–S4) | Han’s Acupoint Nerve Stimulator | 15 ~ 25 mA | Once per hour for 30 min | |

| Xiao H 2015(38) | 2 Hz/100 Hz | Bilateral Hegu (LI4), Zhiyang (GV9, between T7-T8), Jizhong (GV6, between T11-T12) | Han’s Acupoint Nerve Stimulator | Hegu 8–12 mA, Back points 15–25 mA | Once per hour for 30 min |

| Li HY 2012(39) | Not specified | Bilateral Hegu (LI4), Neiguan (PC6), Shangliao (BL31), Ciliao (BL32), Zhongliao (BL33), Xialiao (BL34) | Not specified | Adjust to tolerance every 10 min | Until the end of delivery |

| Xu MJ 2006 (40) | 2–100 Hz dense-dispersed wave | Jiaji points (T10–L1, L2 3 centimeters lateral to both sides of the spine), Ciliao points (S2–S4 offset 3 cm to the side) | Electronic acupuncture stimulator (Suzhou Medical Supplies Co., Ltd.) | 15–30 mA, up to maximum tolerance | Once per hour for 30 min, until the end of the second stage |

| 2/100 Hz | Bilateral Hegu (LI4), Zusanli (ST36), Sanyinjiao (SP6) | Han’s Acupoint Nerve Stimulator | 10–20 mA, to tolerance limit | Once per hour for 30 min, until delivery ends | |

| Su XJ 2001(41) | Not specified | Bilateral Tianzong (SI11), Shenshu (BL23), Sanjiaoshu (BL22), Jianjing (GB21) | Fanke P0-9632 multifunctional electrotherapy apparatus | Adjust clockwise to tolerance | Until the end of delivery |

| Yang X 2021(42) | 2 Hz | Bilateral Zusanli (ST36), Hegu (LI4), Sanyinjiao (SP6) | Huatuo brand electronic acupuncture stimulator | Start at 15 mA, increase to distinct tremor without pain | 20 min/session, 2 h interval, until placental delivery |

| An ZZ 2015(43) | 2 Hz/100 Hz | Bilateral Hegu (LI4), Sanyinjiao (SP6), Zusanli (ST36) | Not specified | Slowly increase to mild numbness/prickling | 30 min/session, 2 h interval, until full dilation |

| Cao JG 2025(44) | 2 Hz/100 Hz | Bilateral Hegu (LI4), Sanyinjiao (SP6) | Not specified | 15–30 mA | Once per hour for 30 min, until 3 cm dilation |

| Wang L 2019(45) | 2 Hz | Bilateral Zusanli (ST36), Hegu (LI4), Sanyinjiao (SP6) | Huatuo brand SDZ-II electronic acupuncture stimulator | Start at 15 mA, increase to distinct tremor without pain | 20 min/session, 2 h interval, until the end of the second stage |

| Xu JH 2022(46) | 2 Hz/100 Hz | Bilateral Hegu (LI4), Neiguan (PC6); Jiaji (T10–L1 3 centimeters lateral to both sides of the spine), Ciliao (S2–S4) | SRL998K fetal monitor/neuromuscular stimulator | 15–50 mA, manual or auto adjustment | Not specified |

| Song KK 2023(47) | 2 Hz | Bilateral Hegu (LI4), Zusanli (ST36), Sanyinjiao (SP6) | Huatuo brand SDZ-II electronic acupuncture stimulator | 15–25 mA, increase to distinct tremor | 20 min/session, 2 h interval, until the end of the second stage |

| He J 2020(48) | Hand: 10–30 Hz; Back: 20–40 Hz | Bilateral Hegu (LI4), Neiguan (PC6) (hands); Bilateral Shenshu (BL23), Sanjiaoshu (BL22), Eight Liao points (back) | SRL998A nerve and muscle stimulator | Hand: 6–20 mA; Back: 7–26 mA | Until the end of delivery |

| Ma ZH 2018(49) | 2 Hz/100 Hz | Bilateral Hegu (LI4), Sanyinjiao (SP6), Zusanli (ST36) | Not specified | Start at 15 mA, increase to tolerable distinct tremor | Until fetal delivery |

| Miao WJ 2020 (50) | Not specified | Jiaji points (T10–L3 3 cm lateral to the spine (bilaterally).), Ciliao points (S2–S4 3 cm lateral to the spine (bilaterally).) | Korean-style nerve electrical stimulation analgesic device (HA NS) | Gradually increase to maximum tolerance | Not specified |

| Meng LK 2020(51) | 2 Hz/100 Hz | Jiaji points (T10–L3), Ciliao (BL32) | Korean-style nerve electrical stimulation analgesic device (HA NS) | 15–30 mA | 30 min/session |

| Han CP 2021(52) | Not specified | Back: T10–L1, L5–S4; Hands: Bilateral Hegu (LI4), Neiguan (PC6) | SRL998A neuromuscular stimulator | Back: 30–70, Hand: 30–50 (units not specified) | From 3 cm to 10 cm cervical dilation |

| Zhao KL 2024(53) | Hand: 6–20 mA; Back: 20–40 Hz | Bilateral Hegu (LI4), Neiguan (PC6), Quchi (LI11) (hands); The horizontal line at the waist is the apex of the gluteal cleft, and the vertical axis is the spine. | Not specified | Hand: 6–20 mA, Back: 20–40 Hz | Until the end of delivery |

| Shi J 2002(54) | Not specified | Bilateral Hegu (LI4), Neiguan (PC6) (hands); T10–L1 (spine) | Lebeier labor analgesia instrument | Start at 15 mA, increase to muscle tremor without pain | Until full cervical dilation |

| Niu CY 2017(65) | 2 Hz/100 Hz | Bilateral Hegu (LI4), Zusanli (ST36) | Not specified | Start at 15 mA, increase to distinct tremor without pain | 30 min/session, 1 h interval, until full dilation |

| Liu Ye 2015(55) | 2 Hz/100 Hz | Zusanli (ST36), Hegu (LI4), Sanyinjiao (SP6) | Not specified | Start at 15 mA, increase to tolerable distinct tremor, ≤30 mA | Once per hour for 30 min, until fetal delivery |

| 2 Hz/100 Hz | Bilateral Hegu (LI4), Sanyinjiao (SP6), Zusanli (ST36) | Not specified | Start at 15 mA, increase to tolerable distinct tremor | Until the end of the first stage | |

| QianJ 2025(56) | 100 Hz (TENS1); 80–100 Hz (TENS2) | Paravertebral regions T10–L1 and S2–S4 | Cefar Rehab 2pro® TENS device | Not specified | 30 min/session |

| Miao Y 2025(57) | 100 Hz | 1 cm lateral to the spine (bilaterally). T10–L1 and S2–S4 | Portable TENS unit | Individually titrated | 30 min/session |

| Xu J 2024(58) | 2–4 Hz (Phase 1:until 8 cm dilation.); 100 Hz (Phase 2 until delivery end) | Phase 1(the cervix has dilated to 4 centimeters.): Sanyinjiao (SP6) Neiguan (PC6) (right hands); Phase 2(8 cm dilation to delivery end)Bilateral Hegu (LI4), Shenmen(HT7) | Portable TENS device | Gradually increase to tolerance | Until the end of delivery |

| Shi XL 2024(59) | 50 Hz (continuous); 2 Hz (burst) | Paravertebral regions T10–L1 and S2–S4 | Not specified | Not specified | Until the end of delivery |

| 100 Hz | Spinal nerve roots T10-L1 and S2-S4 | Not specified | 10–18 mA | 30 min | |

| Huang XZ 2019(66) | Self-adjusted | Bilateral Hegu (LI4), median nerve 4 cm proximal to wrist crease; proximal to wrist crease; highest point of iliac crest to lumbar spinous process | China Doule Group GT500 Series Seventh Generation Multi-functional DAOLE Doule Instrument | Mild muscle tremor induced | Self-adjusted usage time |

| R. Sulu 2022(61) | Not specified | Bilateral Zusanli (ST36), Hegu (LI4), Sanyinjiao (SP6) | Not specified | Gradually increased from 15 mA to obvious tremor | 20 min/session, twice, 2-h interval, Stop when the cervix is fully dilated. M |

| Santana, L. S.2016(60) | Adjusted per tolerance | Hegu (LI4), Neiguan (PC6), paravertebral regions T10-L1 and S2-S4 | SRL998A Bio-feed TENS System | Peak current: 15 mA | From the onset of the active phase until the end of the second stage of labor |

| Zahra MEHRI 2022(67) | 2 Hz/100 Hz | Bilateral Hegu (LI4), Sanyinjiao (SP6), Zusanli (ST36) | Huatuo brand SDZ-II electronic acupuncture stimulator | Start at 15 mA, increase to slight muscle tremor and the pregnant woman’s tolerance level | Until the end of the second stage of labor |

| V. Rashtchi 2022(68) | 2 Hz | Bilateral Hegu (LI4), Sanyinjiao (SP6), Zusanli (ST36) | Huatuo brand SDZ-II electronic acupuncture stimulator | Start at 15 mA, increase to painless | Every 2 h for 30 min, until active phase |

TENS Parameters.

Figure 4

The pain intensity measured by the 10 cm VAS during the first stage of labor with TENS analgesia was compared to epidural analgesia.

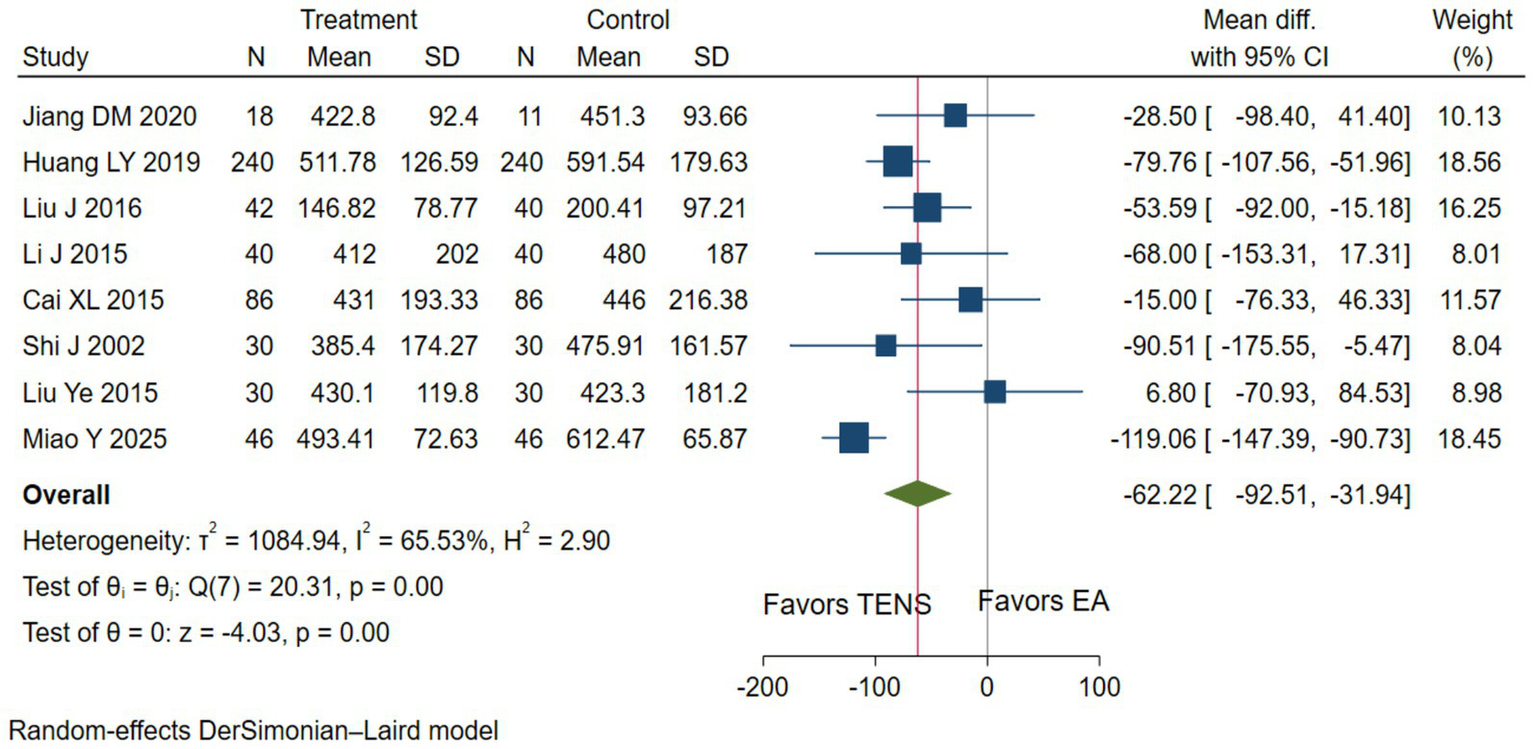

3.5.2 Duration of the first stage of labor

Low evidence (8 RCTs, 1,055 patients) reported that compared with epidural analgesia groups, parturients using TENS may shorten the duration of the first stage of labor (WMD-62.22 min, 95%CI –92.51 to −31.94 min; Table 3 and Figure 5) (28, 29, 34, 36, 37, 50, 54, 55, 57, 59).

Figure 5

The duration of the first stage of labor with TENS analgesia was compared to epidural analgesia.

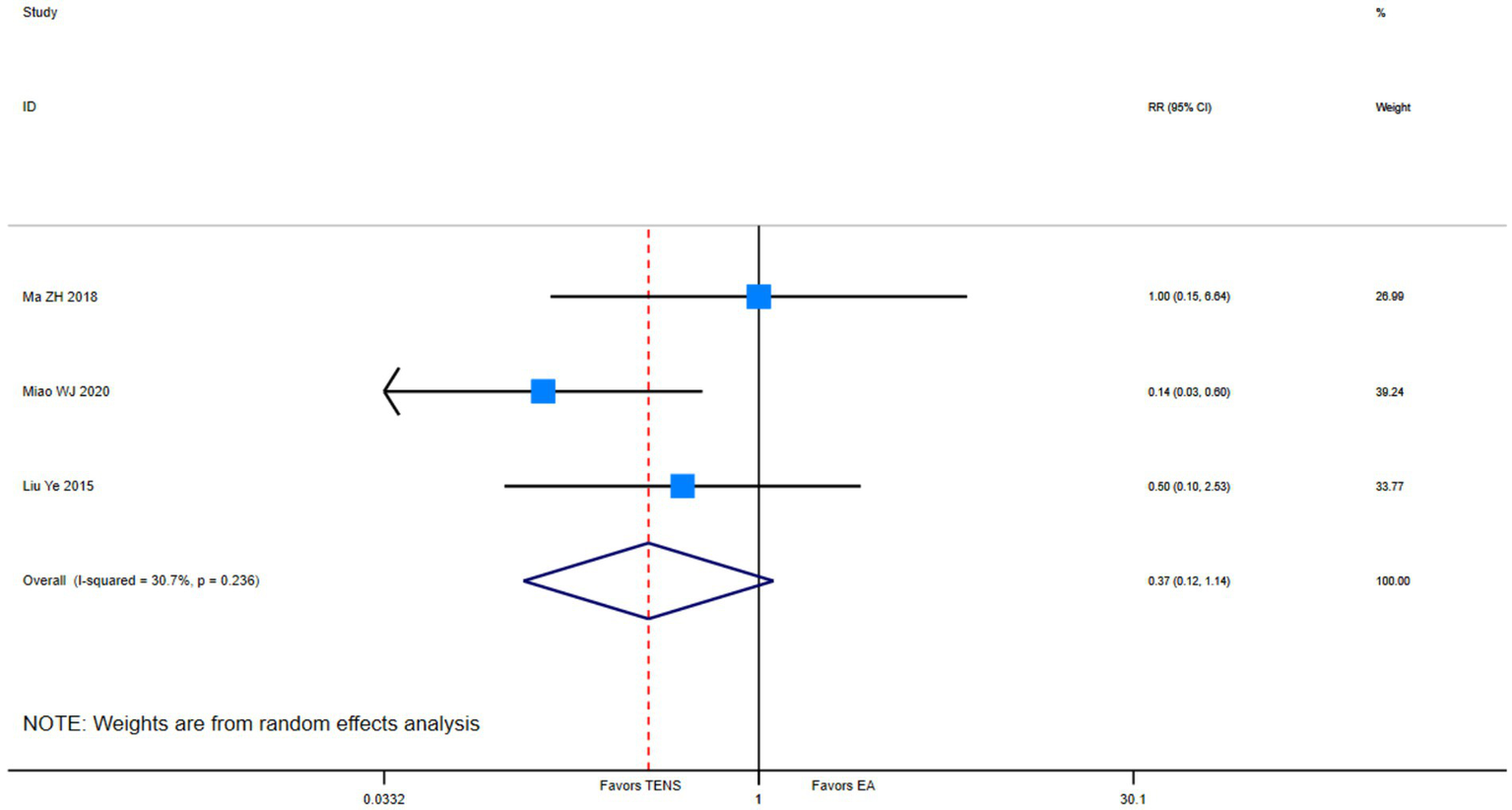

3.5.3 Adverse effects

Low evidence (3 RCTs, 271 patients) suggests that compared with epidural analgesia groups, parturients using TENS may be little to no difference in adverse effects (RR 0.37, 95%CI 0.12 to 1.14; Table 3 and Figure 6) (49, 50, 55).

Figure 6

Adverse events among parturients during the first stage of labor who received TENS versus epidural analgesia.

4 Discussion

4.1 Overall findings

Low-quality evidence suggests that TENS may reduce pain intensity in the first stage of labor compared with sham treatment. When compared with epidural analgesia, TENS may shorten the duration of the first stage; however, no significant differences were observed in analgesic efficacy or the incidence of adverse effects.

4.2 Relations to other reviews

Despite four prior syntheses (75 trials total), one article was included. None of the studies exceeded 32 RCTs threshold surpassed by our 51-trial inclusion. The application of GRADE methodology in this review (absent in 75% of predecessors) provides critical evidence-level stratification.

4.3 Strengths and limitations

The primary strength of this review lies in its comprehensive consideration of two critical concerns during childbirth: effective pain management and labor duration reduction. However, several methodological limitations should be acknowledged, particularly concerning the elevated risk of bias in allocation concealment and blinding procedures.

4.4 Implications

This review holds significant clinical value by demonstrating that transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (TENS) serves as a viable alternative analgesic option for parturients who wish to avoid epidural analgesia during labor. Compared with no analgesic intervention, TENS has a pronounced pain-relieving effect. From a research perspective, our findings underscore the necessity for future clinical trials to optimize methodological rigor, particularly in allocation concealment and blinding procedures, to minimize potential bias.

5 Conclusion

In this systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials on analgesia during the first stage of labor, low-certainty evidence suggests that, Compared with the blank control, TENS may reduce pain intensity and shorten the duration of the first stage of labor in parturients, with little to no difference in adverse events. Compared with epidural analgesia, TENS may shorten the duration of the first stage of labor, with no statistically significant differences observed in analgesic efficacy or adverse effects.

In summary, the current low-certainty evidence suggests that TENS may offer potential benefits for analgesia during the first stage of labor. However, to generate high-quality evidence applicable to clinical practice, there is an urgent need for future large-scale, methodologically rigorous randomized controlled trials that employ adequate randomization and blinding, utilize standardized intervention protocols, and report core clinical outcomes.

Statements

Data availability statement

The datasets presented in this study can be found in online repositories. The names of the repository/repositories and accession number(s) can be found in the article/Supplementary material.

Author contributions

Z-YH: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Software, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. JT: Data curation, Resources, Software, Writing – review & editing. X-XL: Data curation, Formal analysis, Software, Writing – review & editing. D-NY: Data curation, Formal analysis, Software, Writing – review & editing. Z-YC: Data curation, Resources, Writing – review & editing. Y-QL: Data curation, Formal analysis, Writing – review & editing. W-BM: Data curation, Writing – review & editing. LL: Conceptualization, Methodology, Supervision, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declared that financial support was received for this work and/or its publication. This work was supported by the Chengdu University of Traditional Chinese Medicine University-Institute Joint Innovation Fund (Grant No. LH202402049).

Conflict of interest

The author(s) declared that this work was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declared that Generative AI was not used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fmed.2026.1730360/full#supplementary-material

References

1.

Shi MCFX Hou JJ Ma X Zhou CX . Application progress of appropriate traditional Chinese medicine techniques in pain management during labor. J Nurs Sci. (2024) 39:20–4. doi: 10.3870/j.issn.1001-4152.2024.12.020

2.

Zhang MZG . Research Progress on the clinical application of labor analgesia. Jiangsu Medical J. (2020) 46:956–60. doi: 10.19460/j.cnki.0253-3685.2020.09.025

3.

Gu YYXF Li ZZ Zhang GY Gu CY . Transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation for reducing labor pain in women undergoing trial of labor: a Meta-analysis. Chin. J. Women Child. Health. (2024) 15:63–72. doi: 10.19757/j.cnki.issn1674-7763.2024.06.010

4.

Nancy K Lowe P . The nature of labor pain. Am J Obstet Gynecol. (2002)

5.

Moher D Liberati A Tetzlaff J Altman DG . Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. (2009) 6:e1000097. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097,

6.

Yan W Kan Z Yin J Ma Y . Efficacy and safety of transcutaneous electrical Acupoint stimulation (TEAS) as An analgesic intervention for labor pain: a network Meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Pain Ther. (2023) 12:631–44. doi: 10.1007/s40122-023-00496-z,

7.

Yan SX . Impact of epidural analgesia versus transcutaneous neuromuscular electrical stimulation on pregnancy and labor outcomes: A meta-analysis. Lanzhou University. (2019)

8.

Thuvarakan K Zimmermann H Mikkelsen MK Gazerani P . Transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation as a pain-relieving approach in labor pain: a systematic review and Meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Neuromodulation. (2020) 23:732–46. doi: 10.1111/ner.13221,

9.

Melillo A Maiorano P Rachedi S Caggianese G Gragnano E Gallo L et al . Labor analgesia: a systematic review and Meta-analysis of non-pharmacological complementary and alternative approaches to pain during first stage of labor. Crit Rev Eukaryot Gene Expr. (2022) 32:61–89. doi: 10.1615/CritRevEukaryotGeneExpr.2021039986,

10.

Higgins JP Altman DG Gøtzsche PC Jüni P Moher D Oxman AD et al . The Cochrane collaboration's tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ. (2011) 343:d5928. doi: 10.1136/bmj.d5928,

11.

Akl EA Sun X Busse JW Johnston BC Briel M Mulla S et al . Specific instructions for estimating unclearly reported blinding status in randomized trials were reliable and valid. J Clin Epidemiol. (2012) 65:262–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2011.04.015,

12.

Thorlund K Walter SD Johnston BC Furukawa TA Guyatt GH . Pooling health-related quality of life outcomes in meta-analysis-a tutorial and review of methods for enhancing interpretability. Res Synth Methods. (2011) 2:188–203. doi: 10.1002/jrsm.46,

13.

Santesso N Glenton C Dahm P Garner P Akl EA Alper B et al . GRADE guidelines 26: informative statements to communicate the findings of systematic reviews of interventions. J Clin Epidemiol. (2020) 119:126–35. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2019.10.014,

14.

Wang Y Devji T Carrasco-Labra A King MT Terluin B Terwee CB et al . A step-by-step approach for selecting an optimal minimal important difference. BMJ. (2023) 381:e073822. doi: 10.1136/bmj-2022-073822,

15.

Page MJ HJ Sterne J . Chapter 13: Assessing risk of bias due to missing results in a synthesis. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions version 64 (2023).

16.

Guyatt GH Oxman AD Vist GE Kunz R Falck-Ytter Y Alonso-Coello P et al . GRADE: an emerging consensus on rating quality of evidence and strength of recommendations. BMJ. (2008) 336:924–6. doi: 10.1136/bmj.39489.470347.AD,

17.

Gao Y . Effect of transcutaneous low-frequency electrical stimulation combined with doula support on labor analgesia and outcomes in Primiparas. Lab Med Clin. (2023) 20:3514–7. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1672-9455.2023.23.023

18.

Gao XSX Guo Y Lin L Han JX Huang M . Impact of low-frequency electrical nerve and muscle stimulation on labor Progress, delivery mode, and maternal-neonatal outcomes: An analysis. Progress Modern Biomed. (2021) 21:248–53. doi: 10.13241/j.cnki.pmb.2021.02.011

19.

Yan JSY . Effects of combined transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation and epidural block for labor analgesia on maternal pain neurotransmitters, inflammatory cytokines, and stress factors. Maternal Child Health Care China. (2021) 36:955–8. doi: 10.19829/j.zgfybj.issn.1001-4411.2021.04.071

20.

Njogu A Qin S Chen Y Hu L Luo Y . The effects of transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation during the first stage of labor: a randomized controlled trial. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. (2021) 21:164. doi: 10.1186/s12884-021-03625-8,

21.

Lei FYSJ Bi SJ Wang DM Han HJ Zheng DY Yu MJ . Efficacy and safety of transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation combined with a birthing ball for labor analgesia: An investigation. Sichuan. J Tradit Chin Med. (2021) 39

22.

Peng LLLH Cai MY Wang Y Zhao Y Qi DM Luo CR . Effects of combined transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation and epidural block on pain neurotransmitters, inflammatory factors, and stress response in Parturients undergoing labor analgesia. J Clin Experiment Med. (2021) 20:1760–3. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1671–4695.2021.16.022

23.

Zhang XF . Efficacy of transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation combined with intradermal sterile water injections for labor analgesia in Parturients: a study. Contemp Med Symp. (2020) 18:92–93.

24.

Zhang LQ . Application of transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation in labor analgesia: a study. China Continu Med Educ. (2020) 12:120–2. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1674-9308.2020.19.051

25.

Li HYCP Chen H Xu J . Evaluation of two analgesic interventions in doula-assisted delivery. Prev Med. (2020) 32:778–81. doi: 10.19485/j.cnki.issn2096-5087.2020.08.005

26.

Huang JZSL Li JS Wang ZH . Impact and safety analysis of combined electrical stimulation and doula analgesia on labor outcomes. J Binzhou Med Univers. (2020) 43:420–2. doi: 10.19739/j.cnki.issn1001-9510.2020.06.006

27.

Liu PPLJ Zhao YQ Zhang S Wang L . Effects of transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation combined with birthing ball on labor Progress, labor pain, and analgesic drug utilization. Shanghai J Acupunct Moxibust. (2020) 39:47–52. doi: 10.13460/j.issn.1005-0957.2020.01.0047

28.

Jiang DMSH Lai XT Wang L Liu JH . Clinical application of doula support combined with transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation in labor. Med Innov China. (2020) 17. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1674-4985.2020.29.031

29.

Huang LYSP . Impact of full-course multimodal labor analgesia on maternal and neonatal safety. Maternal Child Health Care China. (2019) 34:5134–5137. doi: 10.7620/zgfybj.j.issn.1001-4411.2019.22.19

30.

Zhao ZPQL Lei ZW . Efficacy of Lamaze breathing combined with transcutaneous low-frequency electrical stimulation for labor analgesia and its impact on maternal-infant safety. Nurs Res. (2018) 32:3801–4. doi: 10.12102/j.issn.1009-6493.2018.23.041

31.

Lyu NLY Li L . Safety and efficacy of transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation combined with epidural block for full-course labor analgesia. China Medical Herald. (2018) 15:94–97.

32.

Li LLY Zhai XJ Wang B Cui HY . Clinical study of transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation for labor analgesia. Int J Obstetrics Gynecol. (2018) 45:37–40.

33.

Nyambura A . Application of transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation therapy for pain relief during the first stage of labor. Hunan Normal University. (2020)

34.

Liu JQD Tan X Zuo L Qin JJ Li RM . Efficacy observation of transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation for labor analgesia. J Jinan Univ. (2016) 37:416–9. doi: 10.11778/j.jdxb.2016.05012

35.

Xiao HWJ Wu MX . Adverse reactions assessment of combined electrical stimulation and epidural labor analgesia. (Natural Science & Medicine Edition). J Jinan Univ. (2015) 28:26. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1006-1959.2015.11.032

36.

Li JYY . Study on biofeedback-based transcutaneous electrical stimulation for analgesia in natural childbirth. Shanxi Med J. (2015) 44:2113–5.

37.

Cai XLLD Yao JY Yuan YQ Feng M Jiang M . Impact of two analgesic modalities (transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation and epidural anesthesia) under doula assistance on maternal delivery outcomes. Chin Foreign Med Res. (2015) 13:23–5. doi: 10.14033/j.cnki.cfmr.2015.24.013

38.

Xiao HWJ Kong JQ Li YQ . Clinical study of transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation combined with epidural labor analgesia. J Clin Anesthesiol. (2014) 30:745–7.

39.

Li HYWZ Wang F Xu XF . Efficacy observation of transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation for labor analgesia. Nurs Rehabil. (2012) 11:1140–1.

40.

Xu MJZG Chen L Zhang JY . Clinical study of HANS-assisted PCEA for Labor Analgesia. In: Peking University-Harvard Anesthesia and Pain Therapy Symposium (2006) 3Beijing, China

41.

Su XJAJ . Clinical observation and evaluation of Han's Acupoint nerve stimulator (HANS) for labor analgesia. Chin J Pain Med. (2001) 2:89–93.

42.

Yang XCJ Hu LH . Effects of electrical stimulation at Hegu, Neiguan, and lumbosacral Acupoints on labor pain and duration in Parturients. Guangming J Chin Med. (2021) 36:2592–4. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1003-8914.2021.15.043

43.

An ZZYZ Tong B Zhang YQ . Study on transcutaneous Acupoint electrical stimulation (TEAS) combined with Dexmedetomidine for labor analgesia. Shaanxi J Trad Chin Med. (2015) 36:1410–1.

44.

Cao JGZL Wang YF Li SH Luo W Wang CS . Effect of transcutaneous Acupoint electrical stimulation on intrapartum fever in Parturients receiving epidural labor analgesia. J Clin Anesthesiol. (2025) 41:36–39. doi: 10.12089/jca.2025.01.007

45.

Wang LLP . Effect of transcutaneous Acupoint electrical stimulation on labor pain perception in Primiparas undergoing natural childbirth. Electron J Pract Clin Nurs Sci. (2019) 4:30–1.

46.

Xu JH Xiong DD . Impact of transcutaneous Acupoint electrical stimulation-assisted remifentanil full-course intravenous labor analgesia on mother and infant. Pract Clin J Integrated Trad Chin Western Med. (2022) 22:6–9+13. doi: 10.13638/j.issn.1671-4040.2022.14.002

47.

Song KKYT Yang L Kong ZD Wang Q Gao W . Clinical efficacy of transcutaneous Acupoint electrical stimulation combined with epidural anesthesia for labor analgesia. Chongqing Med. (2023) 52:3133–6+41.

48.

He JWH Zhang RH . Application of transcutaneous Acupoint electrical stimulation combined with epidural block in painless labor and its impact on delivery outcomes. Shanghai J Acupunct Moxibust. (2020) 39:1269–73. doi: 10.13460/j.issn.1005-0957.2020.10.1269

49.

Ma ZHYF Zhao YY Jiao BJ Qu M Mao SH . Clinical study of transcutaneous Acupoint electrical stimulation combined with remifentanil for labor analgesia. Shanghai J Acupunct Moxibust. (2018) 37:526–30. doi: 10.13460/j.issn.1005-0957.2018.05.0526

50.

Miao WJ Qi WH Liu H . Role of Transcutaneous Acupoint Electrical Stimulation in Labor Analgesia. Chinese acupuncture and moxibustion. (2020) 40:615–618, 628. doi: 10.13703/j.0255-2930.20190824-0001

51.

Meng LKWM . Analgesic efficacy of Acupoint electrical stimulation combined with remifentanil PCIA for labor analgesia and its effect on peripheral blood β-endorphin levels. Psychol Monthly. (2020) 15:41+3. doi: 10.19738/j.cnki.psy.2020.01.028

52.

Han CPXW Xie QY . Comparison of analgesic efficacy between Acupoint electrical stimulation and Neuraxial anesthesia in multiparous women during labor. J Minimal Invasive Med. (2021) 16:51–3+62. doi: 10.11864/j.issn.1673.2021.01.11

53.

Zhao KLML Li Y Cui C Yang R Zhang L Li XY et al . Efficacy of combined epidural labor analgesia and transcutaneous Acupoint electrical stimulation in Primiparous women undergoing vaginal delivery. J Women and Children's Health Guide. (2024) 3

54.

Shi JWZ . Efficacy observation of analgesia device combined with tramadol and psychological nursing for labor analgesia. Nurs Res. (2002) 4:210–2. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1009-6493.2002.04.014

55.

Liu Y Xu M Che X He J Guo D Zhao G et al . Effect of direct current pulse stimulating acupoints of JiaJi (T10-13) and Ciliao (BL 32) with Han's Acupoint nerve stimulator on labour pain in women: a randomized controlled clinical study. J Tradit Chin Med. (2015) 35:620–5. doi: 10.1016/s0254-6272(15)30149-7,

56.

Qian JCF Wang YX Yin MQ Zhu XQ . Application of transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation in labor analgesia and its impact on maternal pain scores. Chin Sci J Database Med Health. (2025):57–60.

57.

Miao YLX Zhang X Li GL . Efficacy observation of epidural block anesthesia versus transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation for painless delivery. J Bengbu Med Univ. (2025) 50:630–633. doi: 10.13898/j.cnki.issn.2097-5252.2025.05.015

58.

Xu JXM Lyu F Zhang N . Clinical observation of transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation combined with epidural labor analgesia. China Med Herald. (2024) 21. doi: 10.2004/j.issn.1673-7210.2024.28.26

59.

Shi XLLL Shen T Gao Y . Efficacy of transcutaneous Acupoint electrical stimulation combined with continuous epidural anesthesia for labor analgesia in Primiparas. Pract Clin Med. (2024) 25:68–72. doi: 10.13764/j.cnki.lcsy.2024.04.018

60.

Santana LS Gallo RBS Ferreira CHJ Duarte G Quintana SM Marcolin AC . Transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (TENS) reduces pain and postpones the need for pharmacological analgesia during labour: a randomised trial. J Physiother. (2016) 62:29–34. doi: 10.1016/j.jphys.2015.11.002,

61.

Sulu R Akbas M Cetiner S . Effects of transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation applied at different frequencies during labor on hormone levels, labor pain perception, and anxiety: a randomized placebo-controlled single-blind clinical trial. Eur J Integr Med. (2022) 52:102–124. doi: 10.1016/j.eujim.2022.102124

62.

Báez-Suárez A Martín-Castillo E García-Andújar J García-Hernández J Quintana-Montesdeoca MP Loro-Ferrer JF . Evaluation of different doses of transcutaneous nerve stimulation for pain relief during labour: a randomized controlled trial. Trials. (2018) 19:652. doi: 10.1186/s13063-018-3036-2,

63.

Mehri Z Moafi F Alizadeh A Habibi M Ranjkesh F . Effect of acupuncture-like transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation on labor pain in nulliparous women: a randomized controlled trial [J]. J Acu Tuina Sci. (2022) 20:376–382. doi: 10.1007/s11726-022-1298-4

64.

Movahedi M Ebrahimian M Saeedy M Tavoosi N . Comparative study of transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation, the aromatherapy of Lavandula and physiologic delivery without medication on the neonatal and maternal outcome of patients. Int J Physiol Pathophysiol Pharmacol. (2022) 14:206–10. doi: 10.1007/s11726-022-1298-4

65.

Niu CYTF Kong XL Yang HH . Application of low-frequency pulse electrical stimulation combined with traditional Chinese medicine Meridian theory in labor analgesia: a study. Chin J Mater Child Health Res. (2017) 28:43–4.

66.

H XZ . Clinical study of transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation for labor analgesia. J Pract Med Techniq. (2019) 26:328–30. doi: 10.19522/j.cnki.1671-5098.2019.03.032

67.

Ranjkesh ZMA . Effect of acupuncture-like transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation on labor pain in nulliparous women:a randomized controlled trial. J Acupunct Tuina Sci. (2022) 20:376–82. doi: 10.1007/s11726-022-1298-4

68.

Rashtchi V Maryami N Molaei B . Comparison of entonox and transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (TENS) in labor pain: a randomized clinical trial study. J Maternal-Fetal Neonatal Med. (2022) 35:3124–8. doi: 10.1080/14767058.2020.1813706,

Summary

Keywords

childbirth, labor analgesia, meta-analysis, systematic review, TENS, the first stage of labor, transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation

Citation

Hu Z-Y, Tang J, Li X-X, Yuan D-N, Chen Z-Y, Lyu Y-Q, Ma W-B and Lan L (2026) The efficacy and safety of transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation for labor analgesia in the first stage of labor: a qualitative and quantitative analysis. Front. Med. 13:1730360. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2026.1730360

Received

22 October 2025

Revised

09 December 2025

Accepted

02 January 2026

Published

27 January 2026

Volume

13 - 2026

Edited by

Mattia Dominoni, San Matteo Hospital Foundation (IRCCS), Italy

Reviewed by

John Mitchell, CHU UCL Namur Site Godinne, Belgium

Cansu Kılınç Berktaş, University of Health Sciences, Türkiye

Updates

Copyright

© 2026 Hu, Tang, Li, Yuan, Chen, Lyu, Ma and Lan.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Lei Lan, email@uni.edu

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.