Abstract

Background:

Severe organ function deterioration is associated with poor prognosis in patients with septic shock combined with ARDS. This study aimed to develop a validated predictive model for early organ function deterioration and to evaluate the factors associated with this deterioration, as well as the prognosis, in patients with septic shock combined with ARDS.

Methods:

This is a retrospective study including 67 patients with septic shock combined with ARDS. Patients were categorized into two groups based on the change in their Sequential Organ Failure Assessment (SOFA) score over 24 h: the organ function deterioration group (SOFA24h − 0h score ≥ 1) and the non-deterioration group (SOFA24h − 0h score <1). The sublingual microvasculature of patients was assessed using microcirculatory microimaging to obtain metrics such as proportion of perfusion vessel change rate (ΔPPV), which were then analyzed to characterize the patients with early organ function deterioration.

Results:

There were a total of 34 patients with early organ function deterioration. ΔPPV and LCR were independently associated with early organ function deterioration, and ΔPPV and lactate clearance rate (LCR) were associated with ΔSOFA. The AUC for ΔPPV was 0.813 (95% CI: 0.707–0.919), and when combined with the LCR, the AUC was 0.871 (95% CI: 0.785–0.957).

Conclusions:

Deterioration of organ function is common in patients with septic shock combined with ARDS and early detection is crucial. Microcirculation is an important factor in safeguarding organ function. We developed a predictive model to predict the risk of early organ function deterioration, and the combination of ΔPPV and LCR may merit further investigation.

1 Introduction

Sepsis is caused by a dysregulated host response to infection, resulting in life-threatening organ dysfunction. Characterized by an imbalance in oxygen supply and demand, septic shock is a type of distributive shock that concurrently affects both macrocirculation and microcirculation (1, 2). The lungs, often the initial target in the cascade of multiple organ dysfunction syndrome (MODS) triggered by sepsis, are particularly susceptible to acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) (3), making septic shock and ARDS significant contributors to mortality in critically ill patients.

Additionally, the severity of microcirculatory disorders are associated with increased risk of organ failure and poor prognosis (4). Interestingly, few studies have examined the direct relationship between microcirculatory disturbances and early organ functional impairment.

Trzeciak et al. found that improvements in sublingual microcirculation were associated with enhanced organ function during the early stages of septic shock resuscitation (5). Prompt improvement in microcirculation within the first 6 h can significantly reduce the likelihood of early organ failure and mortality (6). Pan et al. (7) adopted 6 h as the critical time window for evaluating microcirculatory changes and metabolic indicators in their study. Therefore, 6 h represents a pivotal and extensively researched time point for assessing early recovery responses and predicting subsequent disease progression. De Bacher et al. (8) demonstrated that the extent of microcirculatory dysfunction independently predicted survival, with the proportion of perfused vessels (PPV) being the most significant predictor.

Recent studies emphasize the dynamic changes in microvasculature following treatment, which are influenced by individual differences and potential confounding factors, making a single measurement of PPV less reliable. The rate of change in PPV provides insights into changes in vascular opening and the quality of microvascular perfusion over time and is closely associated with poor prognosis in patients with septic shock (7). However, clinical studies focusing on ΔPPV in the early deterioration of organ function in septic shock combined with ARDS are scarce. Normalization of blood lactate levels is a critical goal in the resuscitation of septic shock patients, thus lactate clearance rate (LCR) is a valuable metric for evaluating the effectiveness of treatment (9). Nguyen et al. (10) demonstrated that early lactate clearance is a strong predictor of survival in patients with sepsis.

In this study, we observed the proportion of perfused vessels change rate (ΔPPV) and LCR, analyzing their predictive value for early deterioration of organ function in patients with septic shock and ARDS. Additionally, we investigated the correlation between ΔPPV, LCR, and ΔSOFA to provide clinical insights for the management of sepsis-induced organ failure.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Patients

A retrospective study was conducted on patients diagnosed with septic shock and ARDS who were admitted to the intensive care unit (RICU) of Zhengzhou Central Hospital, affiliated with Zhengzhou University, from October 1, 2021, to May 31, 2023. Inclusion criteria included patients who met the diagnostic standards of Sepsis-3 (11) and the ARDS Berlin Criteria (12). Exclusion criteria were age under 18 years, pregnancy, presence of malignant neoplasms, use of immunosuppressive drugs, oral diseases or heavy bleeding that could affect sample quality, inability to perform invasive mechanical ventilation, and a hospital stay of less than 24 h or death shortly after unsuccessful resuscitation. The study was conducted in accordance with the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Ethics Committee of Zhengzhou Central Hospital affiliated with Zhengzhou University (approval number: 202408).

2.2 Clinical date collection

Data collected included the proportion of perfused vessels (PPV), lactate (Lac), oxygen to inspired oxygen fraction (PaO2/FiO2), central venous pressure (CVP), and mean arterial pressure (MAP) at the time of admission to the RICU (0 h) and at 6 h. Serum creatinine (SCr), total bilirubin (Tbil), C-reactive protein (CRP), procalcitonin (PCT), and platelet count (PLT) were collected on admission.

The change in perfused vessel proportion (ΔPPV) was calculated as ΔPPV = [(PPVT – PPVT0)/PPVT0] × 100%; lactate clearance rate (LCR) was calculated as LCR = [(LacT0 – LacT)/LacT0] × 100%. Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation II (APACHE II) and Sequential Organ Failure Assessment (SOFA) scores were recorded at admission and 24 h later. Patients were categorized based on the change in SOFA score over 24 h (SOFA24h − 0h score), with groups defined as having organ function deterioration (SOFA24h − 0h score ≥ 1) or non-deterioration (SOFA24h − 0h score <1).

2.2.1 Methods for measuring sublingual microcirculation

Sublingual microcirculation was assessed using the MicroSeeV100 handheld video microscope (Medsoft, Guangzhou, China). This device operates based on the principle of side-stream dark-field imaging. Image acquisition strictly followed the standardized operating procedures outlined in the 2018 European Society of Intensive Care Medicine (ESICM) Microcirculation Consensus Statement (13):

Operator training and patient preparation: prior to data collection, the operator completed a structured training program that included theoretical instruction on microcirculatory physiology, hands-on practice on healthy volunteers, and calibration against reference videos to ensure consistent probe handling and artifact recognition. Sublingual secretions were gently removed using a cotton swab moistened with 37 °C saline. The probe, fitted with a disposable sterile cap, was placed lightly on the sublingual mucosa bilaterally to the lingual frenulum, with careful avoidance of any pressure to prevent compression-induced flow artifacts.

Image acquisition time window: to assess microcirculatory responses during early recovery, measurements were taken at patient admission to the RICU (0 h) and 6 h after initiating standard therapy. Each measurement occurred at least 15 min after stabilization of hemodynamic interventions (e.g., rapid fluid resuscitation, vasoactive drug adjustments) to ensure images reflected a relatively stable physiological state.

Acquisition protocol: video sequences were captured from at least five distinct fields of view on both sides of the lingual frenulum. Each sequence lasted a minimum of 20 s to ensure intermittent blood flow capture and sufficient frames for spatiotemporal analysis.

Real-time image quality assessment: operators confirm during acquisition that individual red blood cell movement is clearly observable within capillaries, ensuring uniform illumination, sharp focus, and absence of saliva or bubble obstruction in the field of view.

Image quality control (MIQS): the obtained video clips were sent to two trained physicians, who immediately scored them using the MIQS developed by Massey et al. (14). MIQS comprises lighting, duration, focus, content, stability, and pressure. The two physicians were unaware of the patient's clinical status. If either physician deemed a video clip unacceptable, a new clip was immediately captured and submitted to both physicians for re-evaluation. This process continued until all five video clips received acceptable or good quality scores, at which point the unacceptable clips were discarded.

Data analysis: the screened videos were analyzed by two physicians blinded to the clinical data of the patients, using a sublingual microcirculation imaging system (Model V100, Version V1; Medsoft, Guangzhou, China). The captured video is divided into four independent quadrants, each evaluated based on microvascular blood flow characteristics. A standardized scoring system is applied: no blood flow (score 0), intermittent blood flow (score 1), slow blood flow (score 2), normal blood flow (score 3). The mean score across the four quadrants yields a quantitative indicator of overall microcirculatory perfusion: the Microcirculatory Flow Index (MFI). Perfusion Pressure Ratio (PPV) is calculated as the ratio of perfused microvascular length to total microvascular length, serving as an indicator of microcirculatory perfusion quality.

2.2.2 Measurement of hemodynamic indicators

Intracervical or subclavian venous catheters (7FR, Weihai Jiwei Intensive Care Medical Products Co., Ltd., China) were placed in all patients, and hemodynamic measurements were performed using IntelliVue MP60 monitors (Philips, Germany). Monitored parameters included heart rate (HR), central venous pressure (CVP), and mean arterial pressure (MAP).

2.3 Statistical analysis

Data were analyzed using SPSS 26.0 (IBM, Armonk, NY, USA) and GraphPad Prism 9.4.1.681 (GraphPad Software, Boston, USA). Continuous variables following a normal distribution were expressed as mean ± standard deviation, and comparisons between groups were made using the t-test. Variables not normally distributed were described using the median and interquartile range (IQR), with the Mann-Whitney u-test applied for intergroup comparisons. Categorical variables were summarized as counts and percentages, and analyzed using the Chi-square or Fisher's exact test as appropriate. Correlations were assessed using the Spearman rho statistic. The receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve analysis was used to evaluate the discriminative ability of the clinical predictors. The 28-day mortality rates were calculated, and survival curves were plotted using the Kaplan-Meier method, with the Log-rank test assessing differences among predefined groups. A P-value <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

3 Results

3.1 General characteristics

We initially collected 106 patients with a confirmed diagnosis of septic shock and ARDS. After screening, seven patients were excluded due to death or discharge within 24 h of admission to the intensive care unit. Additionally, nine patients with malignant tumors, six patients receiving immunosuppressive therapy, four patients with oral diseases or hemorrhage, and 13 patients unable to undergo invasive mechanical ventilation were also excluded. Ultimately, 67 patients were included in the study −43 males and 24 females—with an average age of 74.12 ± 14.01 years. Based on the 24-h change in SOFA scores, patients were classified into two groups: the deterioration group (n = 34) and the non-deterioration group (n = 33). The overall ΔSOFA (24-h minus 0-h) across all patients had a median of 0.00 (IQR: −1.00 to 2.00). In the deterioration group, the median ΔSOFA was 2.00 (IQR: 1.00 to 2.25), while in the non-deterioration group, it was −1.00 (IQR: −2.00 to 0.00). Tbil and PCT in the deteriorating group were significantly different from those in the non-deteriorating group. Otherwise, no significant statistical differences were observed in the baseline characteristics between these groups (P > 0.05; see Table 1).

Table 1

| Characteristics | Deterioration (n = 34) | Non-deterioration (n = 33) | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 71.94 ± 15.58 | 76.36 ± 12.02 | 0.199 |

| Males | 22 (64.7) | 21 (63.6) | 0.927 |

| Temperature (°C) | 37.40 ± 1.06 | 37.60 ± 0.99 | 0.435 |

| Respiratory rate (breaths/min) | 21.86 ± 4.59 | 21.00 ± 3.35 | 0.387 |

| Comorbidities, n(%) | |||

| Hypertension | 11 (32.4) | 15 (45.5) | 0.271 |

| Diabetes | 10 (29.4) | 9 (27.3) | 0.846 |

| Cardiovascular | 16 (47.1) | 15 (45.5) | 0.895 |

| Respiratory | 14 (41.2) | 10 (30.3) | 0.353 |

| Site of infection, n(%) | 0.914 | ||

| Respiratory tract | 11 (32.4) | 14 (42.4) | |

| Intra-abdominal | 5 (14.7) | 4 (12.1) | |

| Urinary tract | 5 (14.7) | 4 (12.1) | |

| Skin/soft tissue | 9 (26.5) | 6 (18.2) | |

| Others | 4 (11.8) | 5 (15.2) | |

| APACHE II score | 24.23 ± 5.86 | 22.82 ± 5.24 | 0.301 |

| SOFA score | |||

| 0 h | 12.59 ± 2.56 | 12.15 ± 2.77 | 0.505 |

| 24 h | 14.53 ± 2.51 | 11.33 ± 2.90 | <0.001* |

| ΔSOFA | 2 (1.00, 2.25) | −1 (−2.00, 0.00) | <0.001* |

| SCr (μ mol/L) | 127.50 ± 84.25 | 104.97 ± 71.24 | 0.242 |

| Tbil (μ mol/L) | 23.65 (17.68, 43.13) | 19.60 (9.70,27.10) | 0.009* |

| CRP (mg/L) | 119.45 ± 82.40 | 94.63 ± 72.82 | 0.196 |

| PCT (ng/L) | 28.17 ± 42.50 | 8.19 ± 13.36 | 0.013* |

| PLT (× 109/L) | 113.41 ± 80.10 | 133.24 ± 81.55 | 0.319 |

| Length of stay RICU (days) | 16.47 ± 13.41 | 17.12 ± 11.61 | 0.833 |

Characteristics of the study population.

Data are presented as means (standard deviation; ± SD), median (interquartile range; IQR), or counts (percentage). Differences were tested using the Kruskal–Wallis test or Fisher exact test unless indicated otherwise. APACHE-II, acute physiology and chronic health evaluation II; SCr, serum creatinine; Tbil, total bilirubin; CRP, c-reactive protein; PCT, procalcitonin; PLT, blood platelet; RICU, ICU, respiratory intensive care unit. *P < 0.05.

3.2 Hemodynamic and microcirculatory perfusion indicators

At the outset and 6 h post-admission, there were no significant differences in heart rate (HR), central venous pressure (CVP), mean arterial pressure (MAP), and PaO2/FiO2 ratios between the two groups (P > 0.05). Similarly, no significant differences were noted in initial PPV values. However, after 6 h of treatment, the PPV was significantly lower in the deteriorated group compared to the non-deteriorated group, although it remained higher than the initial value (P < 0.05; see Table 2). Additionally, both ΔPPV and LCR were lower in the deterioration group compared to the non-deterioration group (P < 0.05). We classified the patients into mild, moderate, and severe ARDS categories and compared the respective metrics across these groups. A statistically significant difference in ΔPPV was observed between the severe and moderate ARDS groups (Supplementary Table E1).

Table 2

| Characteristics | Deterioration (n = 34) | Non-deterioration (n = 33) | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR (min-1) | 0 h | 100.59 ± 8.00 | 97.24 ± 7.75 | 0.087 |

| 6 h | 97.50 ± 12.98 | 93.88 ± 6.13 | 1.149 | |

| CVP (cmH2O) | 0 h | 9.32 ± 2.77 | 9.12 ± 1.43 | 0.710 |

| 6 h | 9.38 ± 2.28 | 9.27 ± 1.35 | 0.811 | |

| MAP (mmHg) | 0 h | 73.36 ± 13.97 | 73.44 ± 11.79 | 0.981 |

| 6 h | 79.61 ± 14.98 | 81.09 ± 10.58 | 0.641 | |

| PaO2/FiO2 | 0 h | 186.32 ± 70.08 | 187.24 ± 62.16 | 0.955 |

| 6 h | 218.78 ± 89.58 | 231.86 ± 65.62 | 0.499 | |

| Lac (mmol/L) | 0 h | 7.3 (5.28–9.65) | 5.1 (3.90–6.75) | 0.026* |

| 6 h | 6.25 (4.52–8.75) | 4.00 (3.15–5.45) | 0.001* | |

| PPV % | 0 h | 70.61 ± 11.94 | 72.28 ± 12.25 | 0.574 |

| 6 h | 74.54 ± 11.58 | 81.18 ± 12.54 | 0.028* | |

| LCR | - | 13.41 (4.06–20.71) | 17.65 (9.71–29.75) | 0.003* |

| ΔPPV | - | 6.41 (3.08–8.78) | 11.66 (8.75–14.07) | <0.001* |

Comparison of patient indicators between the two groups.

HR, heart rate; CVP, central venous pressure; MAP, mean arterial pressure; PaO2/FiO2-ratio, pressure of oxygen/fraction of inspired oxygen-ratio; PPV, the proportion of perfused vessels; ΔPPV, the proportion of perfused vessels change rate; LCR, lactate clearance rate. *P < 0.05.

3.3 Independent factors influencing early organ function deterioration in patients with septic shock and ARDS

Multivariate logistic regression analysis revealed that factors including ΔPPV and LCR were independently associated with the onset of early organ function deterioration (see Figure 1, Table 3).

Figure 1

Independent factors associated with early organ function deterioration in patients.

Table 3

| Variable | OR | 95% CI | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| LCR | 0.926 | 0.871–0.984 | 0.013* |

| ΔPPV | 0.818 | 0.716–0.935 | 0.003* |

| PCT | 1.038 | 0.995–1.084 | 0.087 |

| Tbil | 1.024 | 0.995–1.053 | 0.100 |

Results of multivariate analysis in patients.

LCR, lactate clearance rate; ΔPPV, the proportion of perfused vessels change rate; PCT, procalcitonin; Tbil, total bilirubin. *P < 0.05.

3.4 ΔPPV and LCR are important parameters for assessing early organ function deterioration.

Based on the above analysis in Table 2, we found that ΔPPV and LCR were significantly lower in the early organ function deterioration group, and both were independent correlates of early organ function deterioration in patients with septic shock combined with ARDS. We further performed a correlation analysis between ΔPPV, LCR and ΔSOFA (SOFA24h − 0h) and found that ΔPPV, LCR and ΔSOFA were all negatively correlated (rs = −0.326, −0.261; p = 0.007, 0.033; see Figure 2).

Figure 2

ΔPPV and LCR are important parameters for assessing early organ function deterioration.

3.5 Predictive test of early organ function deterioration

ROC analysis indicated that ΔPPV possesses predictive value for early organ function deterioration in patients with septic shock and ARDS. The combined area under the curve (AUC) for ΔPPV and LCR was 0.871, with a sensitivity of 61.80% and a specificity of 97.00% (see Figure 3, Table 4).

Figure 3

ROC curves for predicting early organ function deterioration in patients.

Table 4

| Variable | AUC (95% CI) | Sensitivity (%) | Specificity (%) | Cutoff | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ΔPPV | 0.813 (0.707, 0.919) | 90.90 | 64.70 | 7.642 | <0.0001* |

| LCR | 0.685 (0.559, 0.811) | 69.70 | 38.20 | 14.557 | 0.009* |

| ΔPPV+ LCR | 0.871 (0.789, 0.957) | 61.80 | 97.00 | – | <0.0001* |

Predictive value of single and combined indicators in the early organ function deterioration.

ROC, receiver operating characteristic; AUC, area under the curve.*P < 0.05.

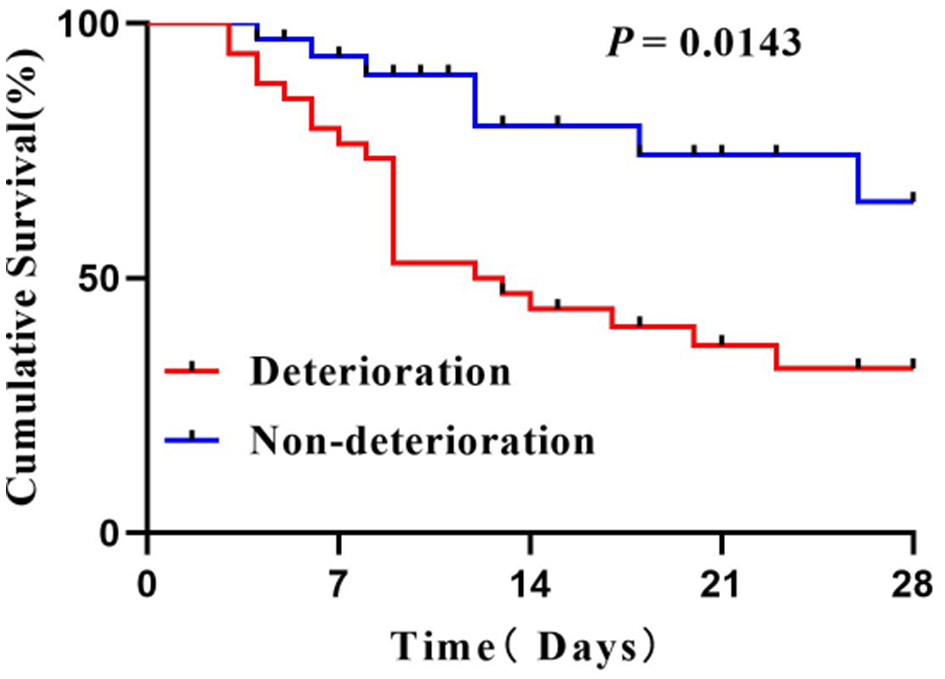

3.6 Survival curves of patients in patients with septic shock and ARDS

Cumulative survival was comparable between the two groups. The patients with early organ failure tending to have shorter 28-day cumulative survival (Log-rank test, P = 0.0143; see Figure 4).

Figure 4

Survival curves of patients.

4 Discussion

Organ failure is a critical event in the pathogenesis of sepsis, marking a hallmark of the disease and a pivotal determinant of prognosis. The damage induced by sepsis stems from the persistence of a mismatch between perfusion and tissue metabolic demands (15). Inflammatory responses leading to cardiac dysfunction and systemic volume redistribution are central to this mismatch, but the situation is exacerbated by impaired tissue oxygen utilization (16). Early indicators of organ function deterioration are vital for prognosis, as they represent the most significant changes in the disease's course. Thus, the prompt, accurate assessment of macrocirculation-microcirculation coupling, and clarification of patient conditions are essential for developing personalized blood flow management strategies to reduce organ failure rates and improve outcomes (17). Our study defines “early organ function deterioration” as ΔSOFA ≥ 1, with this threshold designed to capture early, subtle functional changes for early warning purposes. This is consistent with the definition used by Zeng et al. (18) in a similar microcirculation study. However, we acknowledge that while this threshold exhibits high sensitivity, its specificity may be insufficient. It could potentially include transient, clinically insignificant fluctuations in SOFA scores within the deterioration group, thereby affecting the specificity of the results.

Recent advances in visual imaging technology have enabled the direct observation of capillary changes at the bedside. Studies confirm that alterations in sublingual microcirculation mirror changes in other vital organs, such as the intestines and kidneys (19, 20). Therefore, microcirculation imaging systems used to analyze sublingual microcirculation parameters effectively evaluate the early and ongoing deterioration of critically ill patients and guide precise, individualized treatment strategies. Research by Sakr et al. (21) found that microcirculatory perfusion, continuously impaired in non-survivors of multiple organ failure, improved rapidly in survivors. Our study corroborates these findings, showing uncoupling of microcirculation from macrocirculation after early resuscitation, with sustained hypoperfusion despite normal macrocirculation indices. Patients whose organ function did not deteriorate exhibited significantly higher ΔPPV and PPV during early resuscitation, suggesting that disturbances in microcirculation induced by sepsis are a likely mechanism behind multiorgan dysfunction. Even when initial microcirculatory abnormalities are corrected, improved responses can gradually reduce the likelihood of organ function deterioration (22). Trzeciak et al. also demonstrated experimentally that microcirculatory disturbances occur independently of macrocirculatory changes, with early fluid resuscitation enhancing microcirculatory flow and reducing organ failure within 24 h (5). Levy et al. (23) indicates that improvement in organ function within the first 24 h after treatment initiation is significantly correlated with 28-day survival rates. This emphasizes the importance of assessing patients' dynamic response during the earliest treatment phase (within 24 h). Although shorter time windows (e.g., 6 h) may reflect hemodynamic or metabolic responses earlier, organ function cannot fully reflect the overall therapeutic response within such a short timeframe. Delaying assessment and intervention until 48 h may miss the optimal treatment window, adversely affecting prognosis. Therefore, the 24-h window achieves an optimal balance between sensitivity, specificity, and clinical feasibility, making it suitable for this exploratory study.

Abnormal microcirculatory perfusion often coincides with impaired cellular metabolic energy. Although cell metabolism indices reflect tissue cellular metabolism, they also indirectly indicate microcirculatory function. Occasionally, despite optimal resuscitation and life support, elevated lactate levels persist, possibly due to mitochondrial dysfunction triggered by sepsis (24). Effective lactate clearance requires not only sufficient macrocirculatory blood flow to provide oxygen and reduce anaerobic fermentation but also robust microcirculatory function for effective lactate metabolism. Our findings reveal that the lactate clearance rate (LCR) is higher in patients without early organ function deterioration, suggesting that mitochondrial dysfunction is another critical factor contributing to organ dysfunction during sepsis. Previous studies have shown that both human and animal models exhibit improved organ function and survival rates when mitochondrial function is enhanced (25–27). Our findings demonstrate that both ΔPPV and lactate clearance rate (LCR) are independently and negatively associated with early organ dysfunction, supporting a dual-pathway model of sepsis-induced organ failure. Specifically, ΔPPV reflects dynamic microcirculatory responsiveness—its reduction indicating impaired capillary perfusion despite adequate macrocirculation—while LCR integrates systemic perfusion adequacy with cellular metabolic capacity, particularly mitochondrial function. The negative correlation between these parameters and worsening organ function underscores their pathophysiological relevance. Both ΔPPV and LCR proved to be valuable in predicting early organ dysfunction; however, their combination enhanced predictive efficacy. Although the sensitivity has decreased, the specificity has improved, indicating that the combined index can more accurately identify patients with relatively normal microcirculation and organ function. This may provide more clinically significant predictions in practice, particularly for individuals at higher risk. Pan et al. (7) noted that 28-day mortality rates are elevated in septic shock patients with ΔPPV below 12.1% 6 h post-admission. In our study, a ΔPPV cutoff below 7.6% is also significant for identifying patients at increased risk of early organ function deterioration and mortality. The lower threshold in our study may reflect differences in patient severity but collectively these findings reinforce ΔPPV as a clinically meaningful indicator of microcirculatory compromise and poor prognosis.

Microvascular endothelial cells are essential for regulating microcirculation function and maintaining vascular integrity, and they are significantly affected during sepsis. Recent clinical studies have frequently detected high concentrations of vascular endothelial shedding biomarkers in patients with sepsis-induced ARDS. Preliminary research by Kajita et al. (28) also highlights the close association between persistently elevated vascular endothelial shedding biomarkers levels and sepsis-induced ARDS. Our findings indicate more severe and prolonged microcirculation damage in patients with early-stage organ dysfunction, suggesting that prompt repair of the microcirculatory perfusion could enhance patient outcomes. The negative correlation between ΔPPV, LCR and ΔSOFA further emphasizes the relationship between microcirculatory disturbances and organ failure. In our research, the 28-day cumulative survival rate of patients without early organ function deterioration was significantly higher than that of patients with early organ function deterioration. This finding also underscores the importance for clinicians to monitor microvascular blood flow during resuscitation and to make active efforts to restore microvascular perfusion.

Our study has several limitations. First, this is a single-center, retrospective study with a relatively limited sample size. The retrospective design allows only for the identification of associations, not causal inference. Although bootstrap internal validation was used to assess model overfitting, the small sample size limits statistical power, particularly in multivariate logistic regression with multiple predictors, and increases the risk of spurious findings. Second, despite collecting baseline hemodynamics, laboratory data, and treatment details, we did not adjust for key therapeutic confounders (e.g., timing of antibiotics, source control, ventilator or vasoactive strategies), which may introduce residual confounding. Future large-scale, multicenter, prospective studies should collect data prospectively with different threshold predefined as a primary endpoint to validate our findings.

5 Conclusions

This study demonstrates that the change rate in the proportion of perfused vessels (ΔPPV) holds significant predictive value for early organ function deterioration in patients with septic shock and acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS). When combined with the lactate clearance rate (LCR), ΔPPV enhances predictive efficiency, establishing these metrics as effective indicators for evaluating disease progression and treatment outcomes. Monitoring sublingual microcirculation and its changes has emerged as a key focus in future clinical research, with the aim of enhancing treatment strategies for microcirculation.

Statements

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by Zhengzhou Central Hospital affiliated with Zhengzhou University. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The ethics committee/institutional review board waived the requirement of written informed consent for participation from the participants or the participants' legal guardians/next of kin.

Author contributions

SH: Formal analysis, Writing – original draft, Data curation, Conceptualization, Project administration. XL: Project administration, Conceptualization, Writing – review & editing, Data curation, Formal analysis. RD: Formal analysis, Data curation, Conceptualization, Project administration, Writing – review & editing. YG: Project administration, Resources, Conceptualization, Supervision, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declared that financial support was received for this work and/or its publication. This work was supported by the Medical Science and Technology Research Project of Henan Province (No. LHGJ20240970), the Key Scientific Research Project of Colleges and Universities of Henan Province (No. 23A320036), and the Key Research, Development and Promotion Program (Science and Technology Breakthrough) of Henan Province (No. 252102310110).

Conflict of interest

The author(s) declared that his work was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declared that generative AI was not used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fmed.2026.1733855/full#supplementary-material

References

1.

Gavelli F Castello LM Avanzi GC . Management of sepsis and septic shock in the emergency department. Intern Emerg Med. (2021) 16:1649–61. doi: 10.1007/s11739-021-02735-7

2.

Sygitowicz G Sitkiewicz D . Molecular mechanisms of organ damage in sepsis: an overview. Braz J Infect Dis. (2020) 24:552–60. doi: 10.1016/j.bjid.2020.09.004

3.

Bos LDJ Ware LB . Acute respiratory distress syndrome: causes, pathophysiology, and phenotypes. Lancet. (2022) 400:1145–56. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(22)01485-4

4.

Hobbs KJ Johnson PJ Wiedmeyer CE Schultz L Foote CA . Plasma syndecan-1 concentration as a biomarker for endothelial glycocalyx degradation in septic adult horses. Equine Vet J. (2023) 55:456–62. doi: 10.1111/evj.13862

5.

Trzeciak S McCoy JV Phillip Dellinger R Arnold RC Rizzuto M Abate NL et al . Early increases in microcirculatory perfusion during protocol-directed resuscitation are associated with reduced multi-organ failure at 24 h in patients with sepsis. Intensive Care Med. (2008) 34:2210–7. doi: 10.1007/s00134-008-1193-6

6.

Drost EM Kassabian G Meiselman HJ Gelmont D Fisher TC . Increased rigidity and priming of polymorphonuclear leukocytes in sepsis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. (1999) 159:1696–702. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.159.6.9803061

7.

Pan P Liu DW Su LX He HW Wang XT Yu C . Role of combining peripheral with sublingual perfusion on evaluating microcirculation and predicting prognosis in patients with septic shock. Chin Med J (Engl). (2018) 131:1158–66. doi: 10.4103/0366-6999.231524

8.

De Backer D Donadello K Sakr Y Ospina-Tascon G Salgado D Scolletta S et al . Microcirculatory alterations in patients with severe sepsis: impact of time of assessment and relationship with outcome. Crit Care Med. (2013) 41:791–9. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e3182742e8b

9.

Rimachi R Carvahlo FBD Orellano-Jimenez C Cotton F Vincent JL De Backer DD . Lactate/pyruvate ratio as a marker of tissue hypoxia in circulatory and septic shock. Anaesth Intensive Care. (2012) 40:427–32. doi: 10.1177/0310057X1204000307

10.

Nguyen HB Rivers EP Knoblich BP Jacobsen G Muzzin A Ressler JA et al . Early lactate clearance is associated with improved outcome in severe sepsis and septic shock. Crit Care Med. (2004) 32:1637–42. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000132904.35713.A7

11.

Singer M Deutschman CS Seymour CW Shankar-Hari M Annane D Bauer M et al . The third international consensus definitions for sepsis and septic shock (sepsis-3). JAMA. (2016) 315:801–10. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.0287

12.

Ranieri VM Rubenfeld GD Thompson BT Ferguson ND Caldwell E Fan E et al . Acute respiratory distress syndrome. JAMA. (2012) 307:2526–33. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.5669

13.

Ince C Boerma EC Cecconi M De Backer D Shapiro NI Duranteau J et al . Second consensus on the assessment of sublingual microcirculation in critically ill patients: results from a task force of the European Society of Intensive Care Medicine. Intensive Care Med. (2018) 44:281–99. doi: 10.1007/s00134-018-5070-7

14.

Massey MJ Larochelle E Najarro G Karmacharla A Arnold R Trzeciak S et al . The microcirculation image quality score: development and preliminary evaluation of a proposed approach to grading quality of image acquisition for bedside videomicroscopy. J Crit Care. (2013) 28:913–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrc.2013.06.015

15.

Donoso A Arriagada-Santis D . Síndrome de disfunción de órganos y adaptación mitocondrial en el paciente séptico. Bol Med Hosp Infant Mex. (2021) 78:1–15. doi: 10.24875/BMHIM.20000323

16.

Howell MD Donnino M Clardy P Talmor D Shapiro NI . Occult hypoperfusion and mortality in patients with suspected infection. Intensive Care Med. (2007) 33:1892–9. doi: 10.1007/s00134-007-0680-5

17.

De Backer D Ricottilli F Ospina-Tascón GA . Septic shock: a microcirculation disease. Curr Opin Anaesthesiol. (2021) 34:85–91. doi: 10.1097/ACO.0000000000000957

18.

Zeng XY Liao XL Kang Y Chen Y Yin WH Zhao L . Predictive value of early changes in sublingual microcirculation on organ failure of patients with septic shock. J Sichuan Univ (Med Sci Ed). (2016) 47:574–9.

19.

Ferrara G Edul VSK Canales HS Martins E Canullán C Murias G et al . Systemic and microcirculatory effects of blood transfusion in experimental hemorrhagic shock. ICMx. (2017) 5:27. doi: 10.1186/s40635-017-0136-3

20.

Lima A van Rooij T Ergin B Sorelli M Ince Y Specht PAC et al . Dynamic contrast-enhanced ultrasound identifies microcirculatory alterations in sepsis-induced acute kidney injury. Crit Care Med. (2018) 46:1284–92. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000003209

21.

Sakr Y Dubois MJ De Backer D Creteur J Vincent JL . Persistent microcirculatory alterations are associated with organ failure and death in patients with septic shock. Crit Care Med. (2004) 32:1825–31. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000138558.16257.3F

22.

Hernandez G Bruhn A Luengo C Regueira T Kattan E Fuentealba A et al . Effects of dobutamine on systemic, regional and microcirculatory perfusion parameters in septic shock: a randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind, crossover study. Intensive Care Med. (2013) 39:1435–43. doi: 10.1007/s00134-013-2982-0

23.

Levy MM Macias WL Vincent JL Russell JA Silva E Trzaskoma B et al . Early changes in organ function predict eventual survival in severe sepsis. Crit Care Med. (2005) 33:2194–201. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000182798.39709.84

24.

Lipinska-Gediga M . Sepsis and septic shock—is a microcirculation a main player?Anaesthesiol Intensive Ther. (2016) 48:261–5. doi: 10.5603/AIT.a2016.0037

25.

Carré JE Orban JC Re L Felsmann K Iffert W Bauer M et al . Survival in critical illness is associated with early activation of mitochondrial biogenesis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. (2010) 182:745–51. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201003-0326OC

26.

Sunahara S Watanabe E Hatano M Swanson PE Oami T Fujimura L et al . Influence of autophagy on acute kidney injury in a murine cecal ligation and puncture sepsis model. Sci Rep. (2018) 8:1027. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-19350-w

27.

Kazune S Caica A Volceka K Suba O Rubins U Grabovskis A . Relationship of mottling score, skin microcirculatory perfusion indices and biomarkers of endothelial dysfunction in patients with septic shock: an observational study. Crit Care. (2019) 23:311. doi: 10.1186/s13054-019-2589-0

28.

Kajita Y Terashima T Mori H Islam MM Irahara T Tsuda M et al . A longitudinal change of syndecan-1 predicts risk of acute respiratory distress syndrome and cumulative fluid balance in patients with septic shock: a preliminary study. J Intensive Care. (2021) 9:27. doi: 10.1186/s40560-021-00543-x

Summary

Keywords

acute respiratory distress syndrome, deterioration of organ function, lactic acid clearance, microcirculation, septic shock

Citation

Huang S, Li X, Dong R and Gao Y (2026) The value of proportion of perfused vessels change rate in the evaluation of early organ function deterioration in septic shock and ARDS. Front. Med. 13:1733855. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2026.1733855

Received

28 October 2025

Revised

26 December 2025

Accepted

05 January 2026

Published

22 January 2026

Volume

13 - 2026

Edited by

Marcos Ferreira Minicucci, Sao Paulo State University, Brazil

Reviewed by

Carmen Silvia Valente Barbas, University of São Paulo, Brazil

Hongsheng Wu, Southern Medical University, China

Updates

Copyright

© 2026 Huang, Li, Dong and Gao.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Yanqiu Gao, drgaoyanqiu@126.com

†These authors have contributed equally to this work and share first authorship

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.