Abstract

Introduction:

Geriatric syndromes are nonspecific symptoms and signs that occur with aging. This study aims to investigate the prevalence of geriatric syndromes among elderly hospitalized patients in China.

Method:

This cross-sectional study conducted a Comprehensive Geriatric Assessment (CGA) on elderly patients hospitalized in Ruijin Hospital Luwan Branch, between January 2023 and July 2024. The CGA included evaluations of pain, sleep, constipation, fall risk, urinary incontinence, polypharmacy, nutritional risk, and dementia.

Result:

A total of 150 patients were included in this study. The five most prevalent geriatric syndromes were sleep disorders (44.67%), polypharmacy (40.67%), fall risk (24.67%), urinary incontinence (21.33%), and malnutrition (20.67%). The fall risk was significantly higher in women compared to men (37.50% vs. 12.82%, p < 0.001). Additionally, widowed individuals exhibited higher rates of fall risk (57.70% vs. 9.62%, p < 0.001) and malnutrition (47.83% vs. 8.65%, p < 0.001) compared to married individuals and other groups, with statistically significant differences.

Conclusion:

This study suggested that the incidence of sleep disorders, polypharmacy, and fall risk was relatively high among elderly hospitalized patients. Gender and marital status may have influenced the occurrence of these syndromes. Future care strategies could be tailored to specific populations.

Introduction

Geriatric syndromes encompass a broad range of non-specific symptoms and signs that emerge as older adults experience functional decline across multiple organ systems with advancing age, without fitting into specific disease categories (1). Following the broad, operational definition adopted by the Chinese Geriatric Society (42) and Inouye et al. (2), we use the term “geriatric syndromes” to encompass pain, constipation, and sleep disturbances when they occur in interaction with age-related vulnerability. These syndromes commonly include gait abnormalities, chronic pain, urinary and fecal incontinence, Parkinson’s disease, delirium, falls, frailty, dizziness, syncope, and malnutrition (2, 3). They are not attributed to a single cause but result from progressive dysfunction across various systems, influenced by physical diseases, psychological conditions, social factors, and environmental elements (4). Geriatric syndromes significantly impact activities of daily living (ADLs) and increase vulnerability to morbidity and mortality in older adults (5). They also affect quality of life and psychological well-being, leading to progressive disability, greater caregiving needs, and markedly reduced life expectancy. The presence of geriatric syndromes can serve as important prognostic indicators for morbidity and survival in older adults (6). With the growing aging population in China, comprehensive geriatric assessment (CGA) is increasingly recognized and implemented. This assessment utilizes a multidisciplinary approach to evaluate various aspects of an older adult’s health, including physical function, nutritional status, cognition, activities of daily living, fall risk, sleep, mental health, polypharmacy, frailty, pressure ulcers, and home environment (7–9). The information gathered through these evaluations enables the formulation of tailored intervention plans and integrated care strategies that address immediate and long-term care needs (10). These treatment plans aim to protect the health and functional status of older adults, thereby enhancing their quality of life.

A recent study of 779 older adults in the United States found that 82% had at least one geriatric syndrome (11). In a cohort of 1,705 Australians aged over 70, fewer than 10% of those aged 70–79 exhibited poor mobility, falls, urinary incontinence, frailty, or dementia, whereas this proportion rose to over 10% among those aged 84 and older (12). In 2020, the population of individuals aged 60 and above in China was approximately 264 million (13), and a study of 706 older Chinese adults revealed that 90.5% had at least one geriatric syndrome (14).

Many studies have investigated the prevalence of individual geriatric syndromes (15–17), but up-to-date, multicentre data from mainland China using uniform CGA tools are still scarce, and regional estimates vary widely due to heterogeneous definitions and assessment methods. Understanding the prevalence of geriatric syndromes is crucial for developing effective care strategies for specific subgroups. Therefore, this study aimed to investigate the prevalence of geriatric syndromes among elderly hospitalized patients in China, providing a reference for subsequent integrated management.

Methods

Study design and patients

This cross-sectional study included older adult patients admitted to the Geriatrics Department of the Ruijin Hospital Luwan Branch, affiliated with the Shanghai Jiao Tong University School of Medicine, between January 2023 and July 2024, All patients aged ≥ 60 y admitted to the Department of Geriatrics during the study period were screened consecutively for eligibility, for diseases other than geriatric syndromes. This study was approved by Ruijin Hospital Luwan Branch Ethics Committee Shanghai JiaoTong University School of Medicine (LWEC2020025), and all participants provided written informed consent. After an amendment approved by the Ethics Committee on 03-Mar-2023 (LWEC2020025-A1) the analytical cohort was restricted to patients aged ≥ 80 y because of ward re-organisation.

The inclusion criteria were (1) patients aged 60 years or older and (2) those who provided informed consent. The exclusion criteria were (1) participation in other clinical trials, (2) abnormal mental status, (3) severe comorbidities (such as end-stage disease or critical illness), (4) severe dementia or (5) complete disability.

We acknowledge that excluding patients with severe dementia or altered mental status may underestimate the true prevalence of cognitive impairment and other syndromes. Consequently, our figures should be interpreted as a lower-bound estimate for the population able to participate in structured interviews.

Data collection

All geriatric assessments were completed within 24 h of admission (median 18 h, IQR 12–23) to minimise hospital-related confounding.

The questionnaires were distributed, collected, inspected, and evaluated by healthcare professionals who had received standardized training. The questionnaire included sections on general information and the assessment of geriatric syndromes. The general information section assessed variables such as gender, age, marital status, height, weight, smoking, alcohol consumption, education level, occupation, and hobbies. The geriatric syndromes assessed included pain, evaluated using the Numeric Rating Scale (NRS) (18); sleep quality, assessed using the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI) (19); constipation, assessed using the Chronic Constipation Assessment (20); fall risk, assessed using the Morse Fall Scale (21); urinary incontinence (22); polypharmacy, assessed using the STOPP/START criteria (23); nutritional risk, assessed using the Nutritional Risk Screening (NRS-2002) (24); and cognitive function, assessed using the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) (25). If an individual exhibited any one of the above symptoms, they were diagnosed with geriatric syndrome. The specific assessment criteria are as follows:

The NRS for pain was used to assess pain intensity, with scores assigned as follows: 5 points for extreme pain, 4 points for very severe pain, 3 points for severe pain, 2 points for moderate pain, 1 point for mild pain, and 0 points for no pain.

The PSQI was used to assess sleep quality over the past month, evaluating factors such as sleep duration, efficiency, difficulty falling asleep, nighttime awakenings, and daytime dysfunction (e.g., daytime fatigue). PSQI scores ranging from 0 to 5 indicate good sleep quality, while scores greater than 5 suggest the presence of sleep disorders.

The Chronic Constipation Assessment was used to evaluate bowel movement frequency, stool consistency, and defecation difficulty. Key factors include the frequency of weekly bowel movements, stool hardness (assessed using the Bristol Stool Form Scale), and the need for assistance in defecation (e.g., medication or enema).

The Morse Fall Scale was used to assess fall risk based on factors such as (1) history of falls (0 or 25 points), (2) multiple diagnoses (0 or 15 points), (3) use of assistance devices (0–30 points), (4) medication (20 points for IV or special medications), (5) gait/mobility (0–20 points), and (6) mental status (0 or 15 points). Total scores of 0–24 indicate no risk, 25–50 indicate low risk, and >50 indicate high risk.

Urinary incontinence was screened with the validated International Consultation on Incontinence Questionnaire-Short Form (ICIQ-SF); participants scoring ≥1 were classified as incontinent and the subtype (stress/urge/mixed) was extracted from ICIQ-SF item 3. The Chinese version (Cronbach’s α = 0.88, test–retest r = 0.91) was employed (22).

Polypharmacy was assessed using the STOPP/START criteria, focusing on duplicate medications, unnecessary drugs (which may lead to drug interactions or adverse effects), missing essential medications, and the appropriateness of dosage and duration.

Malnutrition was assessed using the NRS-2002, which evaluates nutritional status based on disease severity, weight loss, and age. The scoring criteria include (1) disease severity (1–3 points), (2) nutritional status (0–3 points based on weight loss or BMI), and (3) an additional point for patients aged 70 or above. A total score greater than 3 indicates a risk of malnutrition.

The Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) was used to evaluate cognitive function across domains such as orientation, memory, attention, calculation, recall, and language. MMSE scores of 24–30 indicate normal cognition, 20–23 indicate mild cognitive impairment, 10–19 indicate moderate cognitive impairment, and scores below 10 indicate severe cognitive impairment.

Sample size

The final sample size (n = 150) was determined by the number of eligible patients admitted during the 6-month recruitment window. No a-priori power calculation was performed because the study was exploratory and descriptive, consistent with STROBE recommendations for observational prevalence surveys.

Statistical analysis

Data were processed and analyzed using SPSS 22.0 (IBM, Armonk, NY, United States). Categorical data were expressed as n (%) and analyzed using the chi-squared (χ2) test. For n > 30 and <5, the Fisher’s exact test was used. Statistical significance was set at p < 0.05.

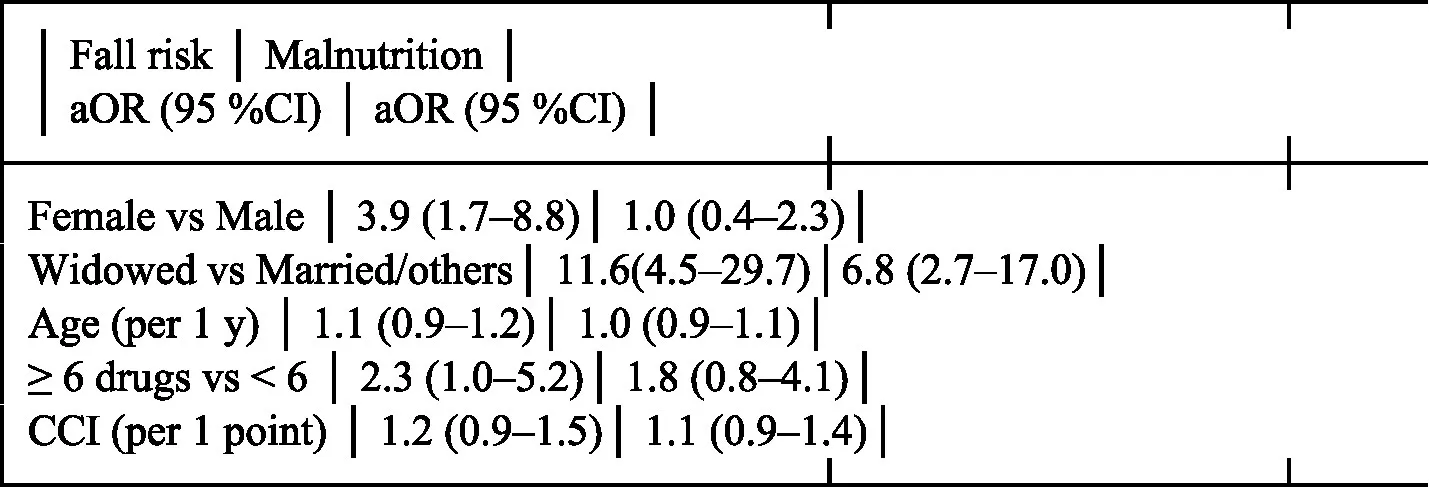

Multivariable logistic regression was performed for the two primary outcomes—fall risk and malnutrition—with simultaneous entry of age (continuous), sex (female vs. male), education level (≤ primary vs. ≥ primary), marital status (widowed vs. married/others), number of medications (≥ 6 vs. ≤ 6), and Charlson Comorbidity Index (continuous). Adjusted odds ratios (aOR) with 95% confidence intervals (CI) are reported in Table 1. A two-tailed p ≤ 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Table 1

|

Multivariable logistic regression analysis of factors associated with fall risk and malnutrition.

This manuscript was prepared in accordance with the STROBE guideline for cross-sectional studies. The completed STROBE checklist is provided as Supplementary Material 1.

Results

Figure 1 shows the flow of participants. During the 6-month recruitment period (January 2023–July 2024), 387 consecutive patients aged ≥ 60 y admitted to the Department of Geriatrics were screened for eligibility; 212 were aged 60–79 y and transferred to the general-medicine ward after an amendment approved on March 03, 2023, leaving 175 patients aged ≥ 80 y. Of these, 25 did not meet inclusion criteria (severe dementia n = 12, critical illness n = 8, complete disability n = 5), and 52 declined to participate. Consequently, 150 patients were enrolled and completed the assessment.

Figure 1

Trial profile of screened, excluded, and enrolled participants aged ≥ 80 y.

Figure 1 shows the trial profile. During the 19-month recruitment period (January 2023–July 2024), 387 consecutive patients aged ≥ 60 y admitted to the Department of Geriatrics were screened; 212 were aged 60–79 y and transferred to the general-medicine ward after the 03-Mar-2023 amendment, leaving 175 patients aged ≥ 80 y. Of these, 25 did not meet inclusion criteria (severe dementia n = 12, critical illness n = 8, complete functional dependence n = 5) and 52 declined to participate. Consequently, 150 patients were enrolled and completed the assessment (Figure 1). The most prevalent geriatric syndrome was sleep disorders (44.67%), followed by polypharmacy (40.67%), fall risk (24.67%), urinary incontinence (21.33%), malnutrition (20.67%), pain (15.33%), chronic constipation (14.67%), and dementia (7.33%) (Table 2). These 11 participants had mild-to-moderate dementia (CDR ≤ 2) and retained decisional capacity after bedside assessment (MMSE ≥ 17 plus UBACC ≥ 14.5); written consent was obtained directly (n = 7) or from a legal proxy (n = 4).

Table 2

| Clinical data | Amount (N = 150) | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Sex | ||

| Male | 78 | 52 |

| Female | 72 | 48 |

| Age (years) | ||

| 80–85 | 45 | 30 |

| 86–90 | 81 | 54 |

| >90 | 24 | 16 |

| Income (RMB) | ||

| <5,000 | 74 | 49.3 |

| 5,000–6,000 | 52 | 34.7 |

| >6,000 | 24 | 16 |

| Marital status | ||

| Widowed | 46 | 30.7 |

| Married and others | 104 | 69.4 |

| Geriatric syndromes | ||

| Sleep disorders | 67 | 44.67 |

| Polypharmacy | 61 | 40.67 |

| Chronic constipation | 22 | 14.67 |

| Fall risk | 37 | 24.67 |

| Urinary incontinence | 32 | 21.33 |

| Pain | 23 | 15.33 |

| Malnutrition | 31 | 20.67 |

| Dementia | 11 | 7.33 |

The clinical characteristics of the study population.

The rate of fall risk was higher in females than in males (37.50% vs. 12.82%, p < 0.001) and in widowed individuals than in marrier and others (57.70% vs. 9.62%, p < 0.001). The rate of malnutrition was higher among widows than in married or other individuals (47.83% vs. 8.65%, p < 0.001). Age and income were not associated with any of the geriatric syndromes assessed in this study (all p > 0.05) (Table 3; Table 4; Supplementary Tables 1–6).

Table 3

| Variable | n (%) | Z/χ2 | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | 12.272 | <0.001 | |

| Male | 10 (12.82) | ||

| Female | 27 (37.50) | ||

| Age (years) | 1.745 | 0.080 | |

| 80–85 | 9 (20.00) | ||

| 86–90 | 17 (20.99) | ||

| >90 | 11 (45.83) | ||

| Income (RMB) | 0.192 | 0.847 | |

| <5,000 | 17 (22.97) | ||

| 5,000–6,000 | 15 (28.85) | ||

| >6,000 | 5 (20.83) | ||

| Marital status | 41.344 | <0.001 | |

| Widowed | 27 (57.70) | ||

| Married and others | 10 (9.62) |

Comparison of characteristics in patients with Fall risk.

Table 4

| Variable | n (%) | Z/χ2 | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | 0.002 | 0.961 | |

| Male | 16 (20.51) | ||

| Female | 15 (20.83) | ||

| Age (years) | 0.880 | 0.379 | |

| 80–85 | 8 (17.77) | ||

| 86–90 | 16 (19.75) | ||

| >90 | 7 (29.17) | ||

| Income (RMB) | 0.563 | 0.573 | |

| <5,000 | 14 (18.92) | ||

| 5,000–6,000 | 11 (21.15) | ||

| >6,000 | 6 (25.00) | ||

| Marital status | 29.849 | <0.001 | |

| Widowed | 22 (47.83) | ||

| Married and others | 9 (8.65) |

Comparison of characteristics in patients with malnutrition.

Discussion

The results of this study revealed a relatively high prevalence of sleep disorders, polypharmacy, and fall risk among elderly hospitalized patients. Furthermore, gender and marital status appear to influence the prevalence of these geriatric syndromes.

The increased prevalence of geriatric syndromes in the elderly is closely linked to the decline in organ function that accompanies aging, as well as the high prevalence of multiple chronic conditions (26). The findings of this study align with previous research, which have shown that geriatric syndromes are common among older adults. For instance, studies have reported that 90.5% of elderly individuals experience at least one geriatric syndrome, and 72.8% suffer from multiple syndromes (27, 28). In this study, the primary geriatric syndromes detected in elderly hospitalized patients were sleep disorders, polypharmacy, and fall risk. The main contributing factors to these results may include the prevalence of chronic diseases, multimorbidity, and the decline in function and cognition commonly seen in older adults. Sleep disorders are particularly prevalent in the elderly population. Age-related changes in circadian rhythms lead to a reduction in melatonin secretion and lower growth hormone levels, which disrupt sleep patterns. Most elderly individuals experience an advanced biological clock, contributing to sleep disturbances and regulatory issues (29). Additionally, the effects of chronic diseases or medication side effects cause gradual organ degeneration, making older adults more susceptible to conditions such as cardiovascular diseases and migraines, both of which can exacerbate sleep disorders. Research has shown that the prevalence of sleep disorders in elderly individuals is significantly higher compared to other age groups, with rates reaching up to 60% (30, 31).

At the time of PSQI administration, median length of stay (LOS) was 1 day (IQR 1–2). To examine whether acute hospital environment biased the results, we repeated the analysis after excluding 14 patients whose LOS ≥ 3 days; the prevalence of poor sleep remained virtually identical (46% vs. 47%, p = 0.91), suggesting that acute hospital-related factors had minimal impact on the PSQI findings. Polypharmacy is also highly prevalent among the elderly, often due to the presence of multiple chronic conditions. Recent studies have found that the comorbidity rate among elderly hospitalized patients in China ranges from 40 to 80%, with some regions reporting rates exceeding 90% (32). Multicentre surveys from Beijing (87%), Shanghai (92%), and Guangzhou (76%) have reported that the comorbidity rate among elderly in-patients in China ranges from 40% to over 90% (33–35). On average, elderly individuals in China suffer from six chronic conditions, which predisposes them to polypharmacy. Approximately 50% of elderly patients take three medications simultaneously, and 25% use four to six medications (32). The decline in physiological reserves in older adults increases their vulnerability to drug side effects, narrowing the safety margin between therapeutic and toxic doses. Several factors contribute to the increased fall risk in elderly individuals, including vision impairments, osteoporosis, decreased muscle strength, impaired balance, and the side effects of medications. These factors compromise physical stability and significantly increase the likelihood of falls (36, 37). Interestingly, gender and marital status were found to be statistically significant in influencing fall risk. Female patients, for example, may have a higher risk due to the loss of estrogen after menopause, leading to osteoporosis and muscle atrophy, which in turn increases fall risk. Among elderly individuals aged 65 to 69, women were found to have a higher incidence of falls compared to men, and a similar trend was observed in those aged 80 and above (38). Additionally, elderly individuals living alone are at greater risk due to a lack of communication and interaction with others, which can lead to undiagnosed physical decline, including vision and hearing impairments, as well as gait and balance problems (39). The absence of social engagement and support can delay recognition and treatment of these issues, further increasing fall risk (40). Moreover, elderly individuals living alone often face challenges with nutrition, as the lack of family and social support may result in poor dietary habits and insufficient nutrient intake (39). The decline in physiological function exacerbates the risk of malnutrition (41), which may help explain the correlation between malnutrition and marital status observed in this study.

After multivariable adjustment, female sex and widowhood remained independently associated with both fall risk and malnutrition, suggesting that these factors are important targets for tailored geriatric interventions.

Additional strengths include < 1% missing data across all instruments and inter-rater reliability κ ≥ 0.85 for every geriatric syndrome assessed.

This study has several limitations. First, the single-centre design limits the generalisability of our findings to other settings. Second, the cross-sectional nature precludes causal inference and temporal assessment of geriatric syndromes. Third, by excluding patients with severe dementia or complete functional impairment we likely under-represented the frailest segment of the hospitalised older population and may have underestimated the true prevalence of geriatric syndromes (potential selection bias). Fourth, the analytical cohort was restricted to patients aged ≥ 80 y after an ethics-approved amendment, further narrowing external validity to younger-old in-patients. Fifth, although we added multivariable models, residual confounding from unmeasured variables (e.g., social support, caregiver availability) cannot be ruled out. Sixth, the sample size was determined by practical recruitment rather than a-priori power calculation, which may reduce precision of estimates for rarer syndromes. Finally, longitudinal multicentre studies are needed to confirm our cross-sectional associations and to test whether targeted comprehensive geriatric assessment interventions can reduce syndrome burden.

In this single-centre cross-sectional study, three out of four hospitalised older adults aged ≥ 80 y presented with at least one geriatric syndrome. Female sex and widowhood were independently associated with higher prevalence. Multicentre longitudinal studies are needed to confirm these associations and to test whether targeted CGA interventions can reduce syndrome burden.

Statements

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by Ruijin Hospital Luwan Branch Ethics Committee Shanghai JiaoTong University School of Medicine (LWEC2020025). The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

XH: Methodology, Writing – original draft, Conceptualization, Resources, Writing – review & editing. WC: Writing – original draft, Software, Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing – review & editing. HR: Formal Analysis, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing, Data curation. JS: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Visualization, Validation. XP: Writing – original draft, Project administration, Investigation, Supervision, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declared that financial support was received for this work and/or its publication. The study was supported by Shanghai Huangpu District Research Project (HLM202002) and Research Project of Shanghai Municipal Health Commission (202140031). The funders had no role in study design, data collection, and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Conflict of interest

The author(s) declared that this work was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declared that Generative AI was not used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fmed.2026.1734756/full#supplementary-material

References

1.

Rosso AL Eaton CB Wallace R Gold R Stefanick ML Ockene JK et al . Geriatric syndromes and incident disability in older women: results from the Women's Health Initiative observational study. J Am Geriatr Soc. (2013) 61:371–9. doi: 10.1111/jgs.12147,

2.

Inouye SK Studenski S Tinetti ME Kuchel GA . Geriatric syndromes: clinical, research, and policy implications of a Core geriatric concept. J Am Geriatr Soc. (2007) 55:780–91. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2007.01156.x,

3.

Zhao L Lu J Li X . Influencing factors of geriatric syndrome in Beijing and the relationship between Barthel Adl score and quality of life. Public Health Prev Med. (2022) 33:95–9.

4.

Yang Y Shi X Ma Q . The impact of common geriatric syndromes on adverse prognoses in patients undergoing Haemodialysis. Chin J Geriatr Med. (2024) 43:406–9. doi: 10.1016/j.gerinurse.2024.03.012

5.

Kozaki K . Frailty and geriatric syndrome. Nihon Rinsho Japan J Clin Med. (2013) 71:974–9.

6.

Wang J Cheng C Fang X . Research Progress on the therapeutic effects of music on chronic diseases and geriatric syndrome in the elderly. Chin J Clin Healthcare. (2023) 26:126–30. doi: 10.1016/j.gerinurse.2023.01.008

7.

Welsh TJ Gordon AL Gladman JR . Comprehensive geriatric assessment--a guide for the non-specialist. Int J Clin Pract. (2014) 68:290–3. doi: 10.1111/ijcp.12313,

8.

Garrard JW Cox NJ Dodds RM Roberts HC Sayer AA . Comprehensive geriatric assessment in primary care: a systematic review. Aging Clin Exp Res. (2020) 32:197–205. doi: 10.1007/s40520-019-01183-w,

9.

Kudelka J Ollenschlager M Dodel R Eskofier BM Hobert MA Jahn K et al . Which comprehensive geriatric assessment (Cga) instruments are currently used in Germany: a survey. BMC Geriatr. (2024) 24:347. doi: 10.1186/s12877-024-04913-6,

10.

Parker SG McCue P Phelps K McCleod A Arora S Nockels K et al . What is comprehensive geriatric assessment (Cga)? An umbrella review. Age Ageing. (2018) 47:149–55. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afx166,

11.

Shah SJ Fang MC Jeon SY Gregorich SE Covinsky KE . Geriatric syndromes and atrial fibrillation: prevalence and association with anticoagulant use in a National Cohort of older Americans. J Am Geriatr Soc. (2021) 69:349–56. doi: 10.1111/jgs.16822,

12.

Noguchi N Blyth FM Waite LM Naganathan V Cumming RG Handelsman DJ et al . Prevalence of the geriatric syndromes and frailty in older men living in the community: the Concord health and ageing in men project. Australas J Ageing. (2016) 35:255–61. doi: 10.1111/ajag.12310,

13.

Payne CF Xu KQ . Life course socioeconomic status and healthy longevity in China. Demography. (2022) 59:629–52. doi: 10.1215/00703370-9830687,

14.

Wang LY Hu ZY Chen HX Tang ML Hu XY . Multiple geriatric syndromes in community-dwelling older adults in China. Sci Rep. (2024) 14:3504. doi: 10.1038/s41598-024-54254-y,

15.

Zhang X Liu Y Van der Schans CP Krijnen W Hobbelen JSM . Frailty among older people in a community setting in China. Geriatr Nurs. (2020) 41:320–4. doi: 10.1016/j.gerinurse.2019.11.013,

16.

Gu L Yu M Xu D Wang Q Wang W . Depression in community-dwelling older adults living alone in China: Association of Social Support Network and Functional Ability. Res Gerontol Nurs. (2020) 13:82–90. doi: 10.3928/19404921-20190930-03,

17.

Wu X Li X Xu M Zhang Z He L Li Y . Sarcopenia prevalence and associated factors among older Chinese population: findings from the China health and retirement longitudinal study. PLoS One. (2021) 16:e0247617. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0247617,

18.

Williamson A Hoggart B . Pain: a review of three commonly used pain rating scales. J Clin Nurs. (2005) 14:798–804. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2005.01121.x,

19.

Buysse DJ Reynolds CF 3rd Monk TH Berman SR Kupfer DJ . The Pittsburgh sleep quality index: a new instrument for psychiatric practice and research. Psychiatry Res. (1989) 28:193–213. doi: 10.1016/0165-1781(89)90047-4,

20.

Allison OC Porter ME Briggs GC . Chronic constipation: assessment and management in the elderly. J Am Acad Nurse Pract. (1994) 6:311–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-7599.1994.tb00960.x

21.

Strini V Schiavolin R Prendin A . Fall risk assessment scales: a systematic literature review. Nurs Rep. (2021) 11:430–43. doi: 10.3390/nursrep11020041,

22.

Bradley CS Rahn DD Nygaard IE Barber MD Nager CW Kenton KS et al . The questionnaire for urinary incontinence diagnosis (Quid): validity and responsiveness to change in women undergoing non-surgical therapies for treatment of stress predominant urinary incontinence. Neurourol Urodyn. (2010) 29:727–34. doi: 10.1002/nau.20818,

23.

O'Mahony D Cherubini A Guiteras AR Denkinger M Beuscart JB Onder G et al . Stopp/Start criteria for potentially inappropriate prescribing in older people: version 3. Eur Geriatr Med. (2023) 14:625–32. doi: 10.1007/s41999-023-00777-y,

24.

Kondrup J Allison SP Elia M Vellas B Plauth M Educational, et al. Espen guidelines for nutrition screening 2002. Clin Nutr (2003) 22:415–421. doi: 10.1016/s0261-5614(03)00098-0.

25.

Arevalo-Rodriguez I Smailagic N Roque-Figuls M Ciapponi A Sanchez-Perez E Giannakou A et al . Mini-mental state examination (Mmse) for the early detection of dementia in people with mild cognitive impairment (mci). Cochrane Database Syst Rev. (2021) 2021:CD010783. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD010783.pub3,

26.

Cesari M Marzetti E Canevelli M Guaraldi G . Geriatric syndromes: how to treat. Virulence. (2017) 8:577–85. doi: 10.1080/21505594.2016.1219445,

27.

Sinha A Kerketta S Ghosal S Kanungo S Lee JT Pati S . Multimorbidity and complex multimorbidity in India: findings from the 2017-2018 longitudinal ageing study in India (Lasi). Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2022) 19:9091. doi: 10.3390/ijerph19159091,

28.

Kumar M Kumari N Chanda S Dwivedi LK . Multimorbidity combinations and their association with functional disabilities among Indian older adults: evidence from longitudinal ageing study in India (Lasi). BMJ Open. (2023) 13:e062554. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2022-062554,

29.

Expert Consensus Group on Diagnosis and Assessment of Sleep Apnoea Syndrome in the Elderly. Excerpts from the expert consensus on the diagnosis and assessment of sleep apnoea syndrome in the elderly. Pract J Cardiac Pulm Vasc Dis. (2022) 30:107–34. doi: 10.3760/cma.j.cmcr.2022.e10134

30.

Ding X Chen Z Chen D . Research progress on the impact of sleep disorders in elderly patients on perioperative neurocognitive dysfunction. Pract Geriatr Med. (2022) 36:437–40. doi: 10.3760/cma.j.cn121430-20220228-00087

31.

Stepnowsky CJ Ancoli-Israel S . Sleep and its disorders in seniors. Sleep Med Clin. (2008) 3:281–93. doi: 10.1016/j.jsmc.2008.01.011,

32.

Dai J Li J He X . Prevalence and influencing factors of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease among elderly inpatients: a study based on the Yunnan Province comprehensive geriatric assessment system. Chin Gen Pract. (2022) 25:1320–6. doi: 10.3760/cma.j.cn121430-20211208-00761

33.

Li J Zhang Y Wang L Liu X Chen S Zhou Q et al . Multimorbidity and its associated factors among elderly inpatients in Beijing: a cross-sectional study. BMC Geriatr. (2021) 21:342. doi: 10.1186/s12877-021-02288-7

34.

Chen S Liu X Huang R Li J Wang Y Zhou Q et al . Prevalence and patterns of multimorbidity in hospitalized older adults in Shanghai. Geriatr Nurs. (2022) 43:89–95. doi: 10.1016/j.gerinurse.2021.11.006

35.

Zhao M Wu C Lin B Zhang Y Li T Chen Y et al . Disease combinations and health outcomes in elderly inpatients in Guangzhou: a retrospective cohort study. Chin J Geriatr. (2022) 41:123–9. doi: 10.3760/cma.j.cn121336-20210305-00123

36.

Fu X Shi J Teng X . The significance of changes in airway inflammatory damage and serum Saa and Crp levels in elderly patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease combined with sleep apnoea syndrome and pulmonary infections. Hebei Med J. (2024) 30:564–9.

37.

Li X . The application of geriatric syndrome assessment in elderly patients with critical cardiac emergencies. Chin J Geriatr Cardiocerebrovasc Dis. (2024) 26:1–4.

38.

Gale CR Westbury LD Cooper C Dennison EM . Risk factors for incident falls in older men and women: the English longitudinal study of ageing. BMC Geriatr. (2018) 18:117. doi: 10.1186/s12877-018-0806-3,

39.

Park J Shin HE Kim M Won CW Song YM . Longitudinal association between eating alone and deterioration in frailty status: the Korean frailty and aging cohort study. Exp Gerontol. (2023) 172:112078. doi: 10.1016/j.exger.2022.112078,

40.

Hopewell S Adedire O Copsey BJ Boniface GJ Sherrington C Clemson L et al . Multifactorial and multiple component interventions for preventing falls in older people living in the community. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. (2018) 7:CD012221. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD012221.pub2,

41.

Tang H Xu H Guo Q . Nutritional risk assessment and influencing factors for the elderly in Minhang community, Shanghai. Environ Occup Med. (2023) 40:1068–73.

42.

Chinese Geriatric Society. Expert consensus on geriatric syndromes assessment and intervention (2020 update).Chin J Geriatr.. (2020) 39:1081–1090. Chinese.

Summary

Keywords

China, geriatrics, polypharmacy, risk of falling, sleep disorders

Citation

Huang X, Cai W, Ren H, Sun J and Pang X (2026) Geriatric syndromes in elderly hospitalized patients in China: a cross-sectional study. Front. Med. 13:1734756. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2026.1734756

Received

12 November 2025

Revised

20 January 2026

Accepted

27 January 2026

Published

11 February 2026

Volume

13 - 2026

Edited by

Tomasz Kryczka, Medical University of Warsaw, Poland

Reviewed by

Ana Domínguez-Navarro, University of Cadiz, Spain

Lena Serafin, Medical University of Warsaw, Poland

Updates

Copyright

© 2026 Huang, Cai, Ren, Sun and Pang.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Xiaofen Pang, xiaofenpang@126.com

†These authors share first authorship

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.