Abstract

Background:

Autosomal recessive polycystic kidney disease (ARPKD) is an inherited renal disorder characterized by multiple renal cysts. This study aimed to investigate the pathogenesis of PKHD1 gene variants in a Chinese ARPKD pedigree and elucidate the mechanisms underlying the phenotypic heterogeneity in patients with PKHD1 mutations.

Methods:

Clinical data and blood samples were collected from the proband and family members. Whole-exome sequencing (WES) and Sanger sequencing were performed. Conservative analysis and local secondary structure prediction of the mutation site were performed to evaluate the pathogenicity. The genotype-phenotype correlation of PKHD1 mutations was analyzed in combination with this pedigree.

Results:

A pediatric patient with ARPKD was identified. Ultrasonography revealed bilateral renal enlargement with multiple cysts, accompanied by hepatic fibrosis. WES identified a novel compound heterozygous variant in the PKHD1 gene (c.5850_5851insTTCAT; p.Gly1951Phefs*25 and c.8710G > A; p.Glu2904Lys). Conservation analysis confirmed that both mutations occurred in conserved regions, indicating potential pathogenicity. Secondary structure prediction revealed that the p.Gly1951Phefs*25 frameshift mutation resulted in protein truncation and conformational changes, whereas the p.Glu2904Lys missense mutation caused drastic changes in amino acid polarity, impairing protein stability and function. Genotype-phenotype analysis of 605 PKHD1 mutations revealed a trend suggesting that hepatobiliary manifestations might present with less severe mutational burden compared to renal phenotypes, and mild homozygous missense mutations or heterozygous states may attenuate or eliminate renal phenotypes.

Conclusion:

This study uncovered novel PKHD1 mutations in an ARPKD patient, expanding the pathogenic gene spectrum of ARPKD and providing insights for genetic counseling and prenatal diagnosis. Our findings also contribute to the understanding of genotype-phenotype correlations in PKHD1 mutation carriers and generate hypotheses regarding potential organ-specific thresholds for disease manifestation.

1 Introduction

Polycystic kidney disease (PKD) is an inherited disorder primarily affecting the kidneys, characterized by the presence of multiple cysts in the renal cortex and medulla, often accompanied by polycystic lesions in the hepatobiliary system (1). Based on the inheritance patterns, PKD can be classified into autosomal recessive polycystic kidney disease (ARPKD, OMIM#263200) and autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease (ADPKD, OMIM#601313) (2). ARPKD is a rare autosomal recessive monogenic cystic disorder with a global incidence of approximately 1/20,000. Clinically, it manifests as bilateral cystic kidneys and hepatic fibrosis, representing one of the most severe diseases leading to end-stage renal disease in children.

The primary pathogenic genes of ARPKD are polycystic kidney and hepatic disease 1 (PKHD1) and DAZ-interacting protein 1-like (DZIP1L). These genes encode the fibrocystin/polyductin (FPC) and DZIP1L proteins, both of which localize to cilia and are associated with ciliary defects; thus, ARPKD is classified as a ciliopathy (2–4). ARPKD is predominantly caused by PKHD1 mutations, whereas DZIP1L mutations are rare. The PKHD1 gene, located on chromosome 6p12, comprises 86 exons and encodes multiple protein isoforms, with FPC being the longest (5). FPC consists of 4074 amino acids and contains two core components: an N-terminal extracellular domain harboring IPT, PA14, G8, and PBH1 domains, and a C-terminal intracellular domain with a ciliary targeting sequence. This sequence may facilitate interactions between FPC and intracellular proteins such as polycystic protein-2 and can be released via Notch-like proteolytic cleavage to execute specific functions (5–7). FPC expression exhibits both tissue specificity and cell type specificity, and is found predominantly in ductal cells and their precursors in the developing kidney, liver, and pancreas (8, 9). Currently, the precise function of FPC remains incompletely understood, and it is hypothesized that FPC acts mainly as a receptor protein, potentially regulating ductal cell formation, proliferation, apoptosis, adhesion, and signal transduction (8).

The typical clinical manifestations of ARPKD in fetuses/neonates include increased bilateral renal volume in late pregnancy or the neonatal period, poor differentiation of the renal cortex and medulla, oligohydramnios, and pulmonary hypoplasia (10). Over 50% of ARPKD neonates die from respiratory insufficiency due to pulmonary hypoplasia. However, survival rates improve significantly beyond the perinatal period, with 1-year and 10-years survival rates reaching 85% and 82%, respectively (2). Owing to cyst formation and interstitial fibrosis in the renal distal tubules and collecting ducts, renal function progressively deteriorates, with approximately 50% of patients developing chronic renal failure in adulthood (5). The liver manifestations primarily include congenital hepatic fibrosis and portal hypertension (11). ARPKD can traditionally be clinically diagnosed in prenatal, neonatal, or end-stage patients exhibiting polycystic kidney features on ultrasound. However, these findings are non-specific and may overlap with those of other disorders, necessitating genetic confirmation (12, 13). Next-generation sequencing, particularly whole-exome sequencing (WES), has been widely applied in the diagnosis of monogenic disorders because of its broad sequencing coverage and relatively low cost, providing a basis for clinical genetic counseling (14, 15).

In this study, WES was employed to investigate the pathogenic mechanism of an ARPKD pedigree complicated with hepatic dysfunction, followed by a systematic genotype-phenotype analysis of PKHD1 gene mutations. These findings not only expand the mutation spectrum of the PKHD1 gene but also elucidate the genotype-phenotype correlation in PKHD1 mutation carriers, laying a foundation for more precise individualized diagnosis and treatment strategies.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Subject

This study included one patient with ARPKD at Shanghai Children’s Hospital. The patient underwent clinical and imaging examinations conducted by specialists, including inquiries about family history, systemic disease history, examination of kidney and liver conditions, and recording of findings. Both the patient (or the guardian if the patient was under 18 years old) and their family members were informed of the content. The study was conducted in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Shanghai Children’s Hospital.

2.2 DNA sample collection

Peripheral venous blood (3–5 ml) was collected from the proband and family members, anticoagulated with EDTA, transferred into a labeled freezing tube, and stored at −80 °C.

2.3 Whole-exome sequencing

Blood genomic DNA was extracted from the proband and their immediate family members via a blood genomic extraction kit (Qiagen) according to the kit’s instructions. After DNA quality testing, exome capture, and library construction, quality control was performed on the library. Once the library passed quality inspection, whole-exome sequencing was conducted on the samples via the Illumina HiSeq PE150 sequencing platform. Bioinformatics analysis was performed on the raw sequencing data, including sequence alignment and variant detection; variant annotation based on variant information, disease information, population frequency, software prediction results, and pathogenicity reports; and variant filtering based on biological harmfulness, genetic coincidence (consistent with familial cosegregation, i.e., different phenotypes and genotypes between patients and healthy family members), and clinical feature coincidence. Mutations with a frequency greater than 0.01 in the Exome Aggregation Consortium (ExAC) and 1000 Genome Browsers (1000G) databases were removed, as well as mutations in intron regions, retaining only exon region mutations. Silent mutations that did not alter the amino acid sequence were also excluded. According to the guidelines of the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics (ACMG),1 variants were classified as pathogenic, likely pathogenic, uncertain significance, likely benign, or benign.

2.4 Sanger sequencing and segregation analysis

Sanger sequencing was performed to verify the PKHD1 (RefSeq: NM_138694.4) mutations we found. All sequence information was extracted from the NCBI database. The primers were designed using Primer 32. SnapGene software was used to analyze the sequencing data. Familial cosegregation analysis was conducted on the probands and their family members, and variants that conform to phenotypic cosegregation were annotated as PP1 in the ACMG classification.

2.5 Conservation and structural modeling of the PKHD1 variants

For conservation analysis, the amino acid sequence encoded by the human PKHD1 gene was obtained from the UniProtKB database3. Strap4 was used to conduct the multiple sequence alignment. For tertiary structural analysis, the protein structure encoded by the PKHD1 gene was predicted using AlphaFold35 to analyze the impact of mutations on protein structure. All the crystal structure figures were generated using the PyMOL Molecular Graphics System6.

2.6 Genotype-phenotype analysis

Literature search was conducted in PubMed for articles reporting PKHD1 variants and associated phenotypes published until April 31, 2023. Variants were included if they were explicitly linked to a clinical diagnosis in the report. Phenotypes were categorized based on the authors’ original descriptions as follows: ARPKD (bilateral renal cysts with or without hepatobiliary involvement); Caroli Disease (CD: isolated segmental intrahepatic bile duct dilatation) (16); Polycystic Liver Disease (PCLD: isolated multiple hepatic cysts) (17); Von Meyenburg Complexes (VMC) (18). For cases with longitudinal data, the most severe or latest reported phenotype was used. Cases with insufficient clinical detail or ambiguous diagnoses were excluded. This curation aims to summarize reported associations rather than calculate epidemiological risk.

3 Results

3.1 Clinical phenotype of the patient

A 5-years-old male patient was admitted for further evaluation following a 5-days history of bilateral lower extremity rash upon referral. The patient had a medical history of premature birth requiring neonatal hospitalization. Abdominal ultrasonography at 2 years of age revealed bilateral nephromegaly. Physical examination upon admission demonstrated hepatomegaly with a firm liver palpable 4 cm below the right costal margin and 6 cm below the xiphoid process. Splenomegaly was also noted, with the spleen palpable 3 cm below the left costal margin and exhibiting firm consistency. No lower extremity edema was observed. Relevant laboratory tests showed significant hepatic dysfunction, manifesting as jaundice, and the urine test results were not significant. Abdominal magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) demonstrated enlarged kidneys with enhanced echoes in the renal medulla and multiple visible cysts. The liver appeared enlarged with irregular surface contours, lobar disproportion, heterogeneous parenchymal signal intensity, and portal vein dilatation, suggesting possible cirrhosis (Figure 1). Both parents underwent abdominal ultrasonography and urinalysis, with all the results falling within normal limits.

FIGURE 1

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) manifestations of the kidney and liver in a child with polycystic kidney disease. (A) Enlarged bilateral kidneys with multiple cysts. (B) Enlarged liver, disproportionate liver lobe ratio, and widened portal vein. MRI, magnetic resonance imaging.

3.2 Whole-exome sequencing and Sanger sequencing

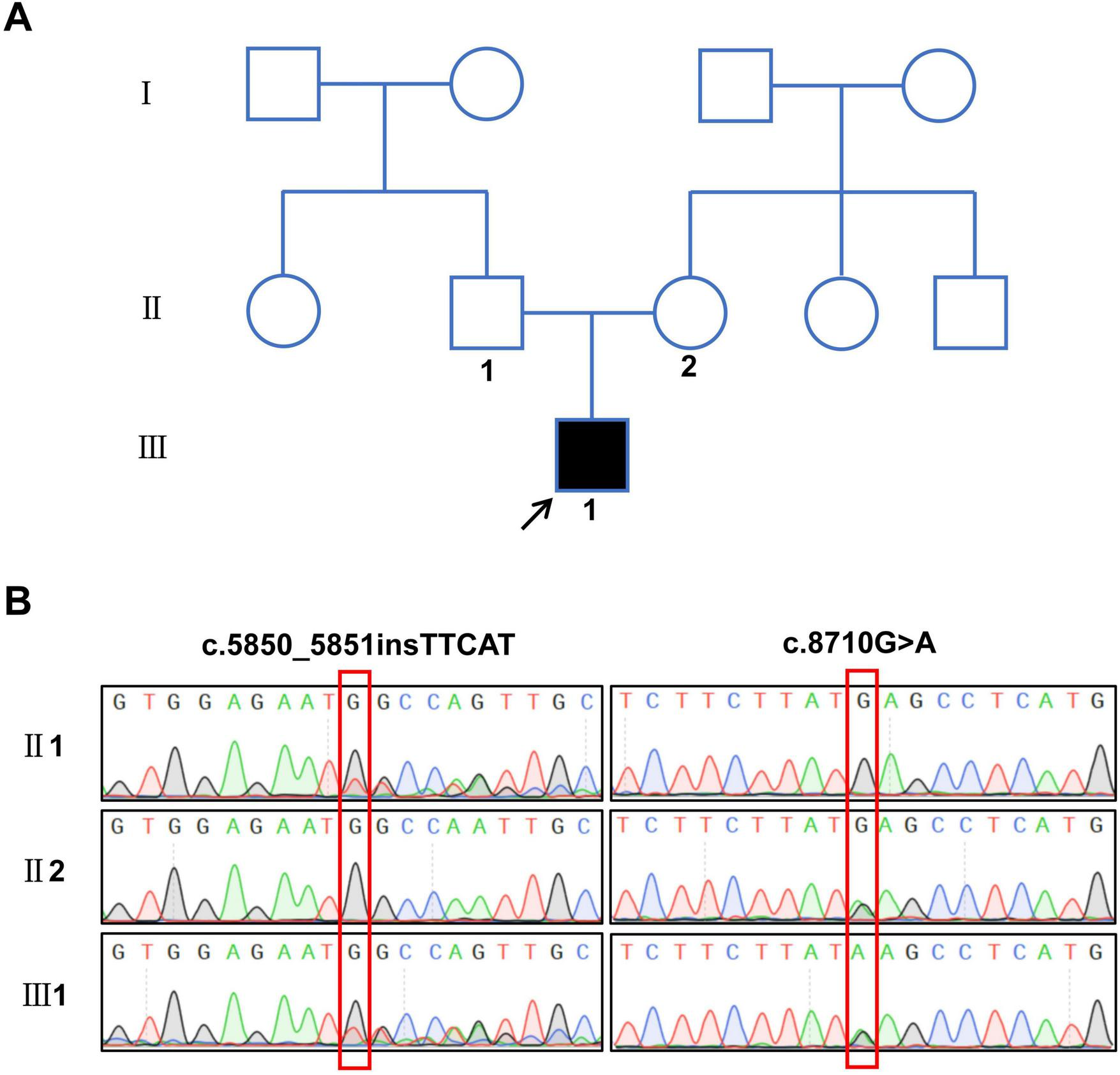

Through whole-exome sequencing and validation by Sanger sequencing, the proband was found to carry a compound heterozygous variation in the PKHD1 gene. The mutations included a frameshift mutation resulting from a multi-base insertion (c.5850_5851insTTCAT, p.Gly1951Phefs*25) and a missense mutation caused by a single-base substitution (c.8710G > A, p.Glu2904Lys). The father carried the c.5850_5851insTTCAT mutation, whereas the mother carried the c.8710G > A mutation (Figure 2). According to the ACMG classification, these two mutations were defined as pathogenic or likely pathogenic. Additionally, pathogenicity predictions using methods such as SIFT, PolyPhen-2, and Mutation Taster indicated that both variants were deleterious (Table 1).

FIGURE 2

Family pedigree and sequencing results of the patient with polycystic kidney disease. (A) Pedigree of the proband’s family, the arrow shows the proband. (B) Sequencing results of compound heterozygous variant sites in the PKHD1 gene.

TABLE 1

| Nucleotide change | Amino acid change | Zygosity | Mutation type | ACMG criteria | Mutation Taster | PROVEAN | SIFT | PolyPhen-2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| c.5850_5851 insTTCAT | p.Gly1951Phefs | Het | Frameshift | P (PVS1 + PM2 + PP1) | Disease causing | NA | NA | NA |

| c.8710G > A | p.Glu2904Lys | Het | Missense | LP (PM1 + PM2 + PP1 + PP3) |

Disease causing | −2.80 deleterious | 0.01 damaging | 0.999 probably damaging |

Clinical description and prediction of the pathogenesis of PKHD1 mutations.

Het, heterozygous; P, pathogenic; LP, likely pathogenic; NA, not available.

3.3 Pathogenesis analysis of PKHD1 mutations

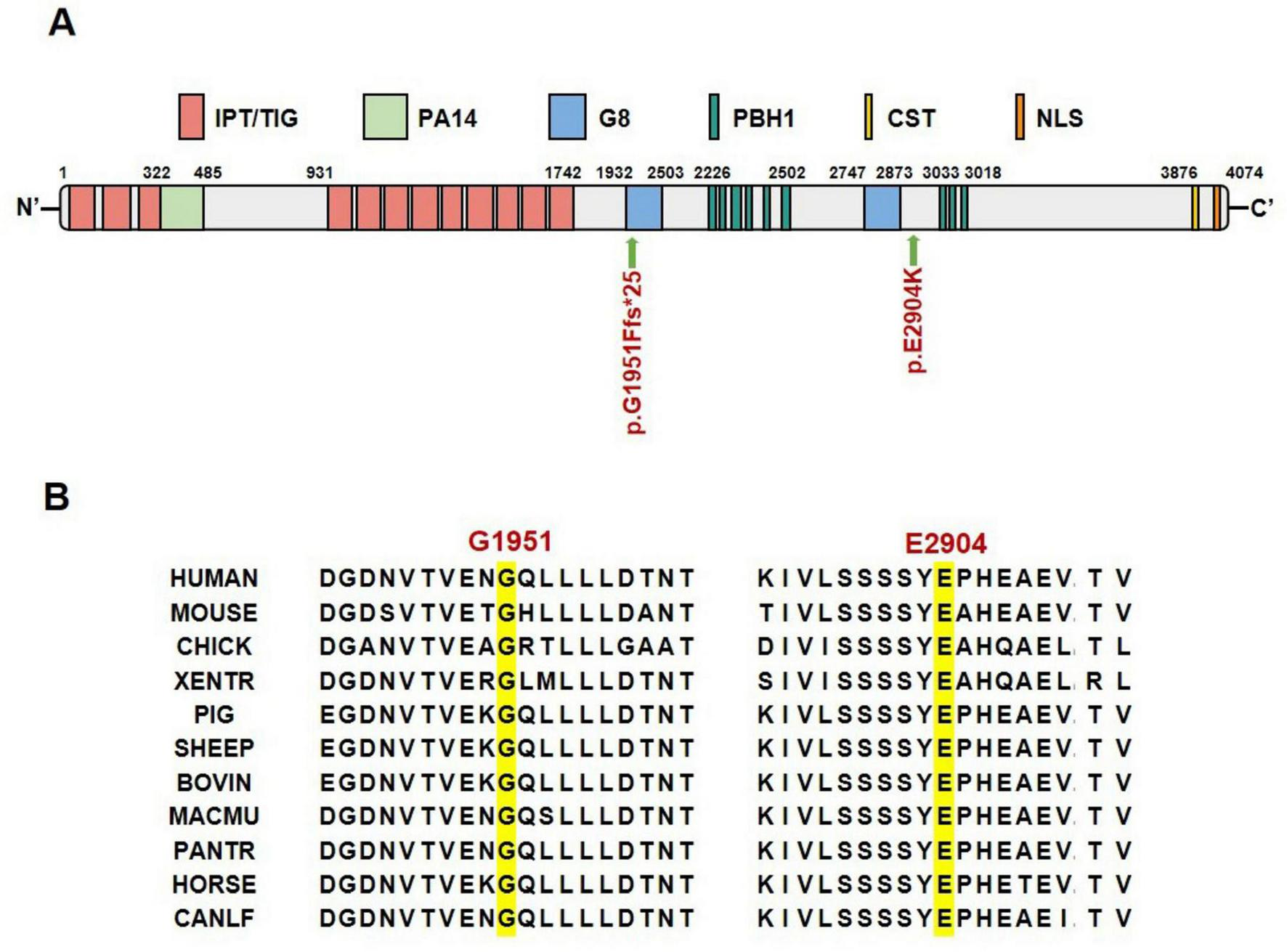

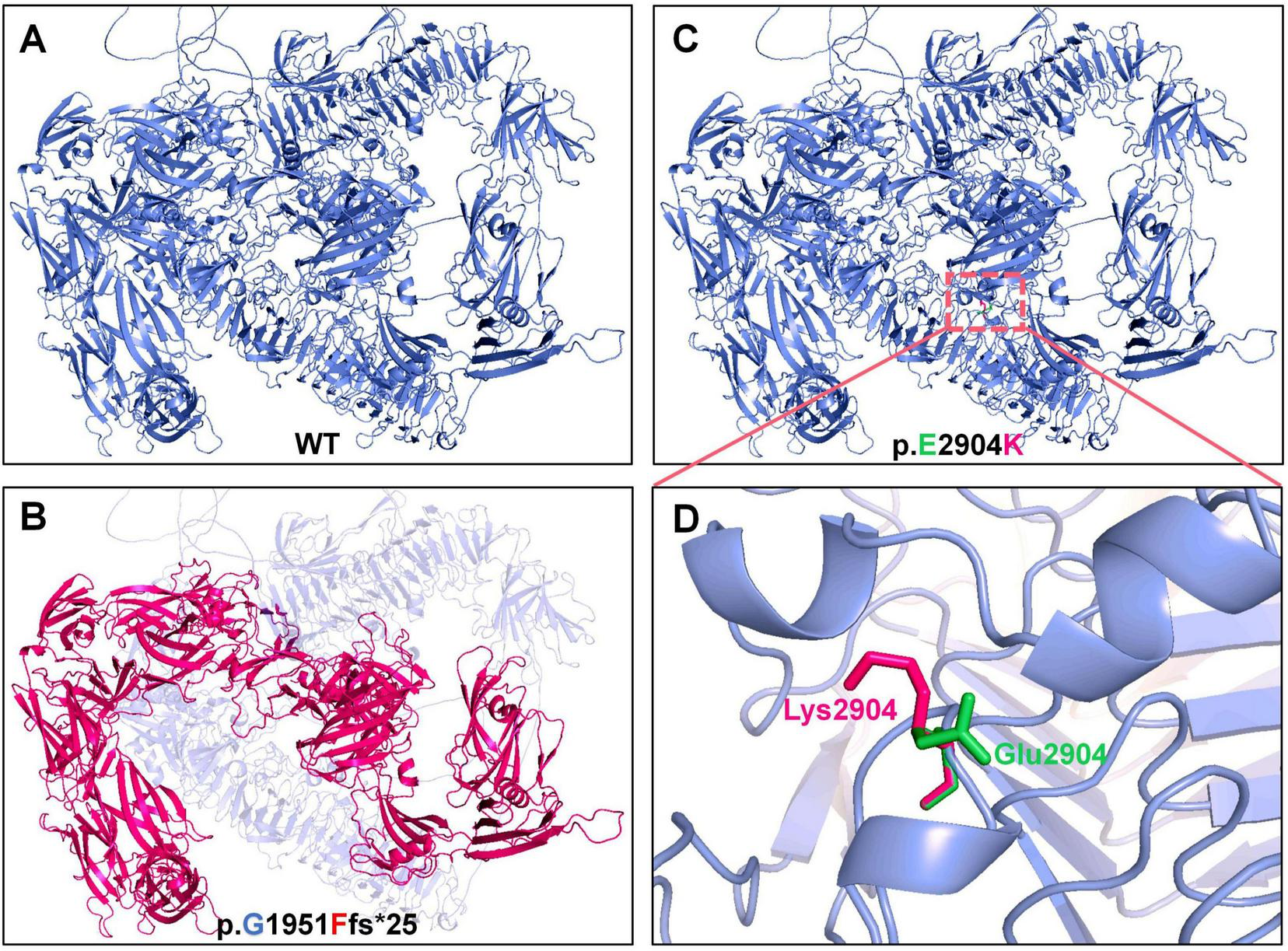

The PKHD1 gene encodes the FPC protein, which comprises two core components. The first core component is the extracellular domain, which includes the N-terminal region and contains multiple domains of interest, such as IPT, PA14, G8, and PBH1. The second core component is the intracellular C-terminal domain, which has a ciliary-targeting sequence (Figure 3A). The p.Gly1951Phefs*25 mutation is located in the first G8 domain and leads to a shortened FPC protein containing only a partial extracellular domain, representing a loss-of-function mutation. The p.Glu2904Lys mutation is located in the extracellular domain and is adjacent to the second G8 domain. Conservation analysis of the FPC protein sequence across different vertebrate species revealed that both mutated amino acid positions, p.Gly1951Phefs*25 and p.Glu2904Lys, were highly conserved across species, suggesting that these mutations may be deleterious variations (Figure 3B). In silico structural modeling using AlphaFold3 predicted that these mutations would significantly affect the secondary structure of the FPC protein. Specifically, the p.Gly1951Phefs*25 mutation caused a frameshift mutation in the FPC protein, resulting in a shift of the protein-coding frame and premature termination 25 amino acids downstream of the mutation site, thereby shortening the protein length (Figures 4A, B). The amino acid Glu is a negatively charged polar amino acid, whereas Lys is a positively charged polar amino acid. The p.Glu2904Lys mutation may lead to a significant change in the charge properties that destabilize the protein. Furthermore, since glutamate acts as an α-helix breaker and lysine serves as an α-helix former, this mutation may also induce local secondary structural alterations. Consequently, the p.Glu2904Lys mutation is likely to alter the local conformation and impair the overall function of the FPC protein (Figures 4C, D).

FIGURE 3

Location and conservation analysis of mutation sites. (A) Schematic diagram of FPC protein domains and mutation sites. (B) Conservation analysis of FPC mutated amino acid sites across different species. IPT/TIG, Ig-like, plexins, transcription factors/transcription factor Ig; PA14, anthrax protective antigen 14; G8, named for 8 conserved glycines; PbH1, parallel beta-helix repeats; CST, ciliary targeting sequence; NLS, nuclear localization signal.

FIGURE 4

Structural prediction of wild-type and mutant FPC. (A,B) Wild-type structure (blue) and the truncated, destabilized structure predicted for the p.Gly1951Phefs*25 mutant (red). (C,D) Local wild-type conformation (green) and the altered conformation predicted for the p.Glu2904Lys mutant (red), highlighting the charge reversal from glutamate (E, negatively charged) to lysine (K, positively charged).

3.4 Genotype-phenotype analysis of patients carrying PKHD1 variants

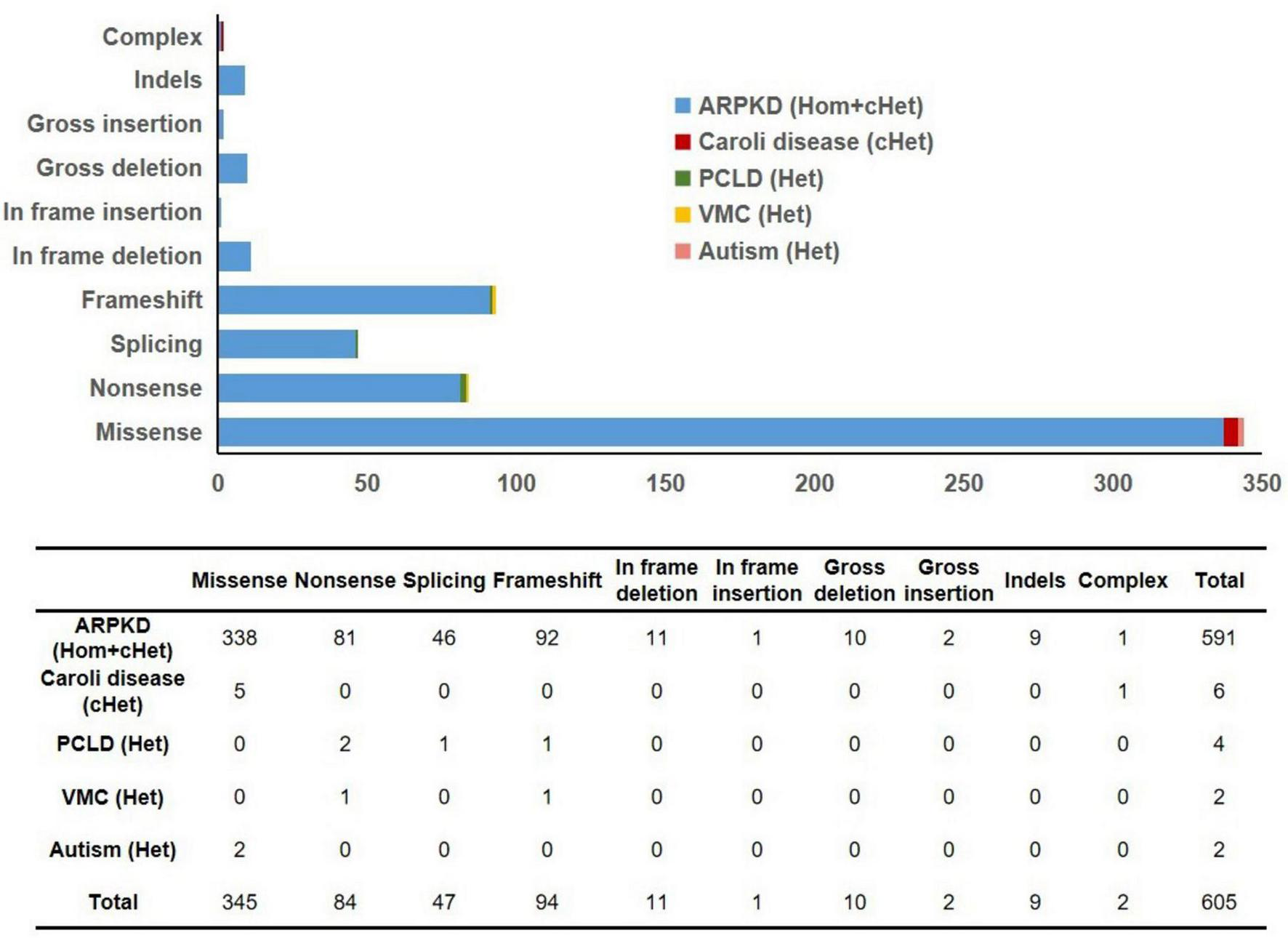

A total of 605 PKHD1 gene mutations and their corresponding clinical phenotypes were summarized (Figure 5 and Supplementary Table 1). Classification by mutation type revealed that missense mutations (345/605) were most prevalent, characterized by single-base-pair substitutions in coding regions. These mutations were followed in frequency by frameshift mutations (94/605), nonsense mutations (84/605), splicing mutations (47/605), in-frame deletions (11/605), large insertions (10/605), insertion-deletions (9/605), large deletions (2/605), complex mutations (2/605), and in-frame insertions (1/605). Although PKHD1 deficiency is well-established in ARPKD, six PKHD1 mutations have been identified in association with Caroli disease (CD, OMIM#600643), a rare autosomal recessive disorder characterized by segmental cystic dilatation of intrahepatic bile ducts, with an estimated occurrence rate of 1 per 1,000,000 live births (16). Notably, all three CD patients carried compound heterozygous mutations–two with missense mutation combinations and one with concurrent missense and complex mutations (Figure 5). Furthermore, four pathogenic mutations responsible for autosomal dominant isolated polycystic liver disease (PCLD) were identified (Figure 5). This condition shares identical hepatic cyst imaging and pathological features with ADPKD, but lacks clinically significant renal cysts (17). It is crucial to note that PKHD1-related disease exists on a continuum. The categorization of isolated hepatic disease is based on the absence of reported renal cysts at the time of publication and does not preclude later renal manifestations or subclinical renal pathology. Four PCLD patients all carried heterozygous loss-of-function mutations (frameshift, nonsense, or splice-site variants). Two additional mutations were associated with von Meyenburg complexes (VMC) (Figure 5), a rare type of ductal plate malformation, with no observed renal abnormalities in these heterozygous patients (18). Two other mutations showed potential associations with autism spectrum disorder, although further validation is required (Figure 5). These pathogenic variants were distributed throughout the PKHD1 gene sequence without apparent mutational hotspots. The majority of patients exhibited ARPKD phenotypes with compound heterozygous PKHD1 mutations. Only three homozygous missense mutation carriers manifested CD without renal involvement, whereas PCLD or VMC patients primarily carried heterozygous nonsense or frameshift mutations, and also lacked renal phenotypes (Figure 5). These findings indicate that the kidney may be less sensitive to PKHD1 mutations compared to hepatic and biliary structures. Severe homozygous mutations may lead to renal phenotypes, whereas milder homozygous missense mutations or heterozygous states may result in attenuated or absent renal manifestations.

FIGURE 5

Summary of mutation types in 605 previously reported PKHD1 variants. ARPKD, autosomal recessive polycystic kidney disease; PCLD, autosomal dominant isolated polycystic liver disease; VMC, von Meyenburg complexes; Hom, homozygous; cHet, compound heterozygous; Het, heterozygous.

4 Discussion

Autosomal recessive polycystic kidney disease is a rare chronic kidney disorder characterized by the presence of cystic kidneys with numerous fluid-filled cysts in the renal parenchyma that continuously expand and progress throughout the lifetime of the patient (1, 19). This study reports a case of ARPKD with early-onset hepatic fibrosis caused by compound heterozygous mutations in the PKHD1 gene. The proband was a 5-years-old boy who presented with significant hepatosplenomegaly and biochemical evidence of hepatic dysfunction, while renal function remained compensated despite enlarged kidneys with multiple cysts. Notably, this case exhibited two prominent features. The liver pathology manifested early and showed potential for progression to cirrhosis. Furthermore, both mutant alleles involved the G8 domains: p.Gly1951Phefs*25 is located within the first G8 domain, and p.Glu2904Lys lies adjacent to the second G8 domain, suggesting that the integrity of these domains may play a crucial role in the development and maintenance of the hepatobiliary system. This pattern resembles observations in some cases from Supplementary Table 1, where compound heterozygous or severe heterozygous mutations at certain loci appeared to correlate with significant liver involvement. The PKHD1 gene encodes FPC, a type I transmembrane protein localized to primary cilia, involved in regulating cell proliferation, apoptosis, and polarity (20, 21). The two novel variants identified in the proband, c.5850_5851insTTCAT (frameshift) and c.8710G > A (missense), are highly conserved in vertebrates, suggesting potential deleterious effects. Structural analysis based on AlphaFold predictions indicated that p.Gly1951Phefs*25 leads to premature translational termination and loss of the intracellular C-terminal domain, potentially disrupting the interaction with polycystin-2 (22, 23); p.Glu2904Lys may cause local charge reversal and alter α-helical propensity, thereby changing conformation and weakening extracellular matrix adhesion. However, these structural inferences are derived from in silico modeling, and further biological experiments are required to validate the pathogenicity of these mutations.

A total of 605 PKHD1 variants were collated in this study. Genotype-phenotype analysis revealed a trend: the vast majority of patients exhibited the ARPKD phenotype associated with compound heterozygous PKHD1 mutations. Additionally, three patients with compound heterozygous missense mutations presented with Caroli disease without renal involvement; four patients with PCLD and two patients with VMC primarily carried heterozygous nonsense or frameshift mutations and showed no renal phenotype at the last evaluation. These findings suggest that the hepatobiliary system may be more sensitive to specific forms of PKHD1 deficiency, while severe renal cystic phenotypes tend to occur in individuals with biallelic loss-of-function mutations. Severe heterozygous mutations (nonsense/frameshift) or mild compound heterozygous missense mutations may be sufficient to cause hepatobiliary abnormalities, which may be related to the crucial role of FPC in ductal plate remodeling and the lack of compensatory mechanisms (24). Conversely, severe renal cystic phenotypes typically require biallelic loss-of-function mutations, likely because polycystin-1/polycystin-2 may partially compensate for FPC dysfunction during collecting duct development (25). In this study, the proband developed liver fibrosis/cirrhosis at 5 years of age while renal function remained compensated, further supporting the hypothesis that the hepatobiliary system may be more sensitive to FPC dysfunction. However, these observations are based on cross-sectional data presented in Supplementary Table 1, without statistical testing or longitudinal adjustment, and lack estimates of population prevalence or risk; therefore, they should be regarded as hypothesis-generating findings rather than definitive biological principles.

This study systematically outlines the mutation types and corresponding phenotypes of Caroli disease, PCLD, and VMC in a relatively large cohort. The data indicate that specific mutation combinations or heterozygous loss-of-function variants may be sufficient to cause hepatobiliary abnormalities, which may reflect the critical role of FPC in ductal plate remodeling and its limited compensatory capacity (26–29). Based on these preliminary findings, it is proposed that regular liver ultrasound monitoring for PKHD1 heterozygous carriers could be considered as a potential clinical consideration. However, it is acknowledged that current evidence is limited, the number of such cases is small, prevalence and risk estimates are lacking, and existing clinical guidelines do not recommend routine screening for asymptomatic carriers. Validation in larger, longitudinally followed cohorts is needed to untangle organ-specific susceptibility and inform risk-stratification strategies. Notably, the proband’s father carries the PKHD1 frameshift mutation c.5850_5851insTTCAT (p.Gly1951Phefs*25) but showed no abnormalities on abdominal ultrasound or urinalysis, indicating no clinically detectable hepatobiliary or renal phenotype in adulthood. Possible explanations include developmental or genetic modifiers that attenuate phenotypic expression; mutation-site-dependent functional impact; limitations of conventional imaging in detecting subtle or early lesions; and age-dependent phenotypic manifestation. Therefore, the mere presence of a truncating variant does not predict disease occurrence, emphasizing the need for cautious interpretation in genetic counseling and consideration of longitudinal familial assessment.

This study expands the mutational spectrum of PKHD1-related disorders, provides genotype-phenotype observations based on a large-scale variant dataset, and offers references for genetic counseling and prenatal diagnosis for the studied family. Major limitations include: the relatively small number of reported cases with so-called isolated liver phenotypes (CD, PCLD, VMC), limiting statistical power; reliance on in silico structure-function inferences without functional experimental validation; the dichotomous classification of phenotypes failing to fully capture the disease continuum, where renal involvement may be delayed or subclinical; and the integration of data from heterogeneous sources with incomplete clinical information or short follow-up in the genotype-phenotype analysis dataset. Future studies should employ standardized methods to recruit larger cohorts, conduct functional experiments, and perform lifelong clinical monitoring to elucidate the molecular basis and clinical implications of organ-specific susceptibility.

5 Conclusion

In summary, this study expands the mutational spectrum of ARPKD, and analysis of reported PKHD1 variants suggests a potential correlation between mutation severity and phenotypic expression, with hepatobiliary manifestations may be associated with a milder mutational burden compared with renal phenotypes. Our findings underscore the utility of genetic diagnosis for counseling and indicate the need for further investigation to clarify the true organ-specific vulnerability.

Statements

Data availability statement

The datasets presented in this study can be found in online repositories. The names of the repository/repositories and accession number(s) can be found in this article/Supplementary material.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by Ethical Committee of the Children’s Hospital of Shanghai. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. Written informed consent for participation in this study was provided by the participants’ legal guardians/next of kin. Written informed consent was obtained from the individual(s), and minor(s)’ legal guardian/next of kin, for the publication of any potentially identifiable images or data included in this article.

Author contributions

JZ: Data curation, Validation, Methodology, Writing – original draft. KY: Funding acquisition, Writing – review & editing, Investigation, Data curation. YH: Investigation, Writing – review & editing, Data curation, Supervision.

Funding

The author(s) declared that financial support was received for this work and/or its publication. This work was supported by the grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant no. 82501084) and the China Postdoctoral Science Foundation (Grant no. 2025M771767).

Acknowledgments

We thank the patient as well as his parents for their participation.

Conflict of interest

The author(s) declared that this work was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declared that generative AI was not used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fmed.2026.1741795/full#supplementary-material

Footnotes

3.^ https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/

4.^ http://www.bioinformatics.org/strap/

References

1.

Roediger R Dieterich D Chanumolu P Deshpande P . Polycystic kidney/liver disease.Clin Liver Dis. (2022) 26:229–43. 10.1016/j.cld.2022.01.009

2.

Bergmann C Guay-Woodford LM Harris PC Horie S Peters DJM Torres VE . Polycystic kidney disease.Nat Rev Dis Primers. (2018) 4:50. 10.1038/s41572-018-0047-y

3.

Lu H Galeano MCR Ott E Kaeslin G Kausalya PJ Kramer C et al Mutations in Dzip1l, which encodes a ciliary-transition-zone protein, cause autosomal recessive polycystic kidney disease. Nat Genet. (2017) 49:1025–34. 10.1038/ng.3871

4.

Ward CJ Hogan MC Rossetti S Walker D Sneddon T Wang X et al The gene mutated in autosomal recessive polycystic kidney disease encodes a large, receptor-like protein. Nat Genet. (2002) 30:259–69. 10.1038/ng833

5.

Goggolidou P Richards T . The genetics of Autosomal Recessive Polycystic Kidney Disease (ARPKD).Biochim Biophys Acta Mol Basis Dis. (2022) 1868:166348. 10.1016/j.bbadis.2022.166348

6.

Dafinger C Mandel AM Braun A Göbel H Burgmaier K Massella L et al The carboxy-terminus of the human ARPKD protein fibrocystin can control STAT3 signalling by regulating SRC-activation. J Cell Mol Med. (2020) 24:14633–8. 10.1111/jcmm.16014

7.

Melchionda S Palladino T Castellana S Giordano M Benetti E De Bonis P et al Expanding the mutation spectrum in 130 probands with ARPKD: identification of 62 novel PKHD1 mutations by sanger sequencing and MLPA analysis. J Hum Genet. (2016) 61:811–21. 10.1038/jhg.2016.58

8.

Ma M . Cilia and polycystic kidney disease.Semin Cell Dev Biol. (2021) 110:139–48. 10.1016/j.semcdb.2020.05.003

9.

Onuchic LF Furu L Nagasawa Y Hou X Eggermann T Ren Z et al PKHD1, the polycystic kidney and hepatic disease 1 gene, encodes a novel large protein containing multiple immunoglobulin-like plexin-transcription-factor domains and parallel beta-helix 1 repeats. Am J Hum Genet. (2002) 70:1305–17. 10.1086/340448

10.

Mateescu DŞ Gheonea M Bălgrădean M Enculescu AC Şerbănescu MS Nechita F et al Polycystic kidney disease in neonates and infants. Clinical diagnosis and histopathological correlation. Rom J Morphol Embryol. (2019) 60:543–54.

11.

Benz EG Hartung EA . Predictors of progression in autosomal dominant and autosomal recessive polycystic kidney disease.Pediatr Nephrol. (2021) 36:2639–58. 10.1007/s00467-020-04869-w

12.

Iorio P Heidet L Rutten C Garcelon N Audrézet MP Morinière V et al The “salt and pepper” pattern on renal ultrasound in a group of children with molecular-proven diagnosis of ciliopathy-related renal diseases. Pediatr Nephrol. (2020) 35:1033–40. 10.1007/s00467-020-04480-z

13.

Bergmann C . Recent advances in the molecular diagnosis of polycystic kidney disease.Expert Rev Mol Diagn. (2017) 17:1037–54. 10.1080/14737159.2017.1386099

14.

Manickam K McClain MR Demmer LA Biswas S Kearney HM Malinowski J et al Exome and genome sequencing for pediatric patients with congenital anomalies or intellectual disability: an evidence-based clinical guideline of the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics (ACMG). Genet Med. (2021) 23:2029–37. 10.1038/s41436-021-01242-6

15.

Xu D Mao A Chen L Wu L Ma Y Mei C . Comprehensive Analysis of PKD1 and PKD2 by long-read sequencing in autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease.Clin Chem. (2024) 70:841–54. 10.1093/clinchem/hvae030

16.

Fahrner R Dennler SG Inderbitzin D . Risk of malignancy in Caroli disease and syndrome: a systematic review.World J Gastroenterol. (2020) 26:4718–28. 10.3748/wjg.v26.i31.4718

17.

Besse W Dong K Choi J Punia S Fedeles SV Choi M et al Isolated polycystic liver disease genes define effectors of polycystin-1 function. J Clin Invest. (2017) 127:1772–85. 10.1172/JCI90129

18.

Lin S Shang TY Wang MF Lin J Ye XJ Zeng DW et al Polycystic kidney and hepatic disease 1 gene mutations in von Meyenburg complexes: case report. World J Clin Cases. (2018) 6:296–300. 10.12998/wjcc.v6.i9.296

19.

Burgmaier K Broekaert IJ Liebau MC . Autosomal Recessive Polycystic Kidney Disease: diagnosis, Prognosis, and Management.Adv Kidney Dis Health. (2023) 30:468–76. 10.1053/j.akdh.2023.01.005

20.

Wang S Zhang J Nauli SM Li X Starremans PG Luo Y et al Fibrocystin/polyductin, found in the same protein complex with polycystin-2, regulates calcium responses in kidney epithelia. Mol Cell Biol. (2007) 27:3241–52. 10.1128/MCB.00072-07

21.

Outeda P Menezes L Hartung EA Bridges S Zhou F Zhu X et al A novel model of autosomal recessive polycystic kidney questions the role of the fibrocystin C-terminus in disease mechanism. Kidney Int. (2017) 92:1130–44. 10.1016/j.kint.2017.04.027

22.

Bergmann C Frank V Küpper F Kamitz D Hanten J Berges P et al Diagnosis, pathogenesis, and treatment prospects in cystic kidney disease. Mol Diagn Ther. (2006) 10:163–74. 10.1007/BF03256455

23.

Hopp K Ward CJ Hommerding CJ Nasr SH Tuan HF Gainullin VG et al Functional polycystin-1 dosage governs autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease severity. J Clin Invest. (2012) 122:4257–73. 10.1172/JCI64313

24.

Woollard JR Punyashtiti R Richardson S Masyuk TV Whelan S Huang BQ et al A mouse model of autosomal recessive polycystic kidney disease with biliary duct and proximal tubule dilatation. Kidney Int. (2007) 72:328–36. 10.1038/sj.ki.5002294

25.

Wu Y Dai XQ Li Q Chen CX Mai W Hussain Z et al Kinesin-2 mediates physical and functional interactions between polycystin-2 and fibrocystin. Hum Mol Genet. (2006) 15:3280–92. 10.1093/hmg/ddl404

26.

Ishimoto Y Menezes LF Zhou F Yoshida T Komori T Qiu J et al A novel ARPKD mouse model with near-complete deletion of the Polycystic Kidney and Hepatic Disease 1 (Pkhd1) genomic locus presents with multiple phenotypes but not renal cysts. Kidney Int. (2023) 104:611–6. 10.1016/j.kint.2023.05.027

27.

Yang H Sieben CJ Schauer RS Harris PC . Genetic Spectrum of Polycystic Kidney and Liver Diseases and the Resulting Phenotypes.Adv Kidney Dis Health. (2023) 30:397–406. 10.1053/j.akdh.2023.04.004

28.

Cordido A Vizoso-Gonzalez M Garcia-Gonzalez MA . Molecular pathophysiology of autosomal recessive polycystic kidney disease.Int J Mol Sci. (2021) 22:6523. 10.3390/ijms22126523

29.

Hanna C Iliuta IA Besse W Mekahli D Chebib FT . Cystic kidney diseases in children and adults: differences and gaps in clinical management.Semin Nephrol. (2023) 43:151434. 10.1016/j.semnephrol.2023.151434

Summary

Keywords

autosomal recessive polycystic kidney disease, genotype-phenotype, novel mutation, pathogenic mechanism, PKHD1

Citation

Zhao J, Yu K and Huang Y (2026) Novel compound heterozygous PKHD1 mutations in a Chinese ARPKD pedigree and analysis of genotype-phenotype correlations. Front. Med. 13:1741795. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2026.1741795

Received

07 November 2025

Revised

10 January 2026

Accepted

15 January 2026

Published

06 February 2026

Volume

13 - 2026

Edited by

Marina V. Nemtsova, I.M. Sechenov First Moscow State Medical University, Russia

Reviewed by

Mingzhu Miao, The First Affiliated Hospital of Nanjing Medical University, China

Tamara Nikuseva Martic, University of Zagreb, Croatia

Updates

Copyright

© 2026 Zhao, Yu and Huang.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Yujuan Huang, huangyj2012@sjtu.edu.cnKang Yu, kqyukang@163.com

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.