Abstract

Functional Constipation (FC) is a prevalent gastrointestinal motility disorder worldwide that markedly impairs patients’ quality of life, yet the currently available treatment options often show limited efficacy. In recent years, research has gradually revealed the critical role of the gut microbiota and bile acid metabolism in the pathogenesis of FC. Fecal Microbiota Transplantation (FMT), which restores the intestinal microecological balance by transferring gut microbiota from healthy donors, has demonstrated clinical efficacy in promoting bowel movements, improving stool consistency, and enhancing patients’ quality of life. However, its underlying mechanisms remain incompletely understood. Current evidence indicates that FMT restores microbial diversity, increases beneficial taxa, and partially reconstructs the bile acids (BAs) profile, thereby modulating Farnesoid X Receptor (FXR) and Takeda G Protein–Coupled Receptor 5 (TGR5) mediated signaling pathways to enhance intestinal secretion and alleviate constipation-related symptoms. The resulting microbiota–bile acid–receptor pathway elucidates the mechanistic link between microbial remodeling and host gastrointestinal motility, thereby offering theoretical support for the therapeutic application of FMT in functional constipation.

1 Introduction

Functional Constipation (FC) represents one of the most common subtypes of constipation in clinical practice, is typically defined by decreased bowel movement frequency, prolonged or difficulty in evacuation, and a sensation of incomplete defecation. The global prevalence of this condition is approximately 12% (1). Beyond affecting daily life, FC has been strongly associated with metabolic derangements as well as psychological comorbidities, including anxiety and depression (2, 3). Current therapies such as laxatives and prokinetics often provide suboptimal and transient relief, underscoring the need for alternative strategies (4). It is thus of considerable clinical significance to explore new therapeutic modalities.

Accumulating evidence indicates that alterations in gut microbiota structure and function play an essential role in the onset and progression of FC. Patients with FC often exhibit reduced microbial diversity, accompanied by a deficiency of functional bacteria responsible for producing short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs) and secondary bile acids (BAs) (5). Bile acid, especially secondary bile acid, was demonstrated to modulate the intestinal motor function and mucosal function primarily through the activation of two key bile acid receptors: Farnesoid X receptor (FXR) and Takeda G protein–coupled receptor 5 (TGR5) (6). Fecal Microbiota Transplantation (FMT) has recently been recognized as a promising therapeutic approach for Functional Constipation (FC) and related disorders, demonstrating improvements in bowel function and enhancements in quality of life (7). However, despite encouraging clinical outcomes, the mechanisms by which FMT exerts its benefits remain incompletely understood. This review synthesizes current evidence on how FMT influences the gut microbiota–BA–receptor axis and its relevance to FC pathophysiology, and then correlate these influences and clinical symptom improvements, so as to lay a basis of FMT application at the level of theory.

2 Changes in intestinal microbiota after FMT intervention

2.1 Changes in microbiota diversity due to FMT

FMT restores intestinal microecological balance by introducing donor microbiota into the recipient’s gut, thereby significantly improving the intestinal microbial environment. This includes enhancing α-diversity (richness and evenness of microbial communities) as well as β-diversity (differences in microbial composition among populations). Specifically speaking, FMT expands α-diversity of the receiver’s gut, and the microbiota profile of the receiver becomes more similar to healthy donor microbiotas. Increased α-diversity is positively correlated with increased bowel movement frequencies among FC patients. Furthermore, the restoration of α-diversity is often accompanied by an increase in key metabolic products, such as short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs), which are instrumental in sustaining intestinal barrier homeostasis and improving bowel function (8, 9). And β-diversity FMT expands similarity among donor and receiver microbiotas. It’s manifested not only at the general level of the structure of the community, but at transplantation and steady establishment of key microbial species, respectively (10, 11). After FMT, for example, there’s reappearance of Faecalibacterium prausnitzii in the receiver’s gut, and it’s closely connected with clinical symptom amelioration (7). Donor source of FMT and treatment times exert significant influences on the scale of restoration. Healthy donor sources tend toward more lasting restoration of improvements, and repeat transplantation achieves superior steady reconstruction of microbiotas toward a single transplantation (7, 12).

2.2 Changes in microbiota structure

In patients with FC, the gut microbiota imbalance is not only reflected in the overall reduction of diversity but also in specific structural changes. Studies have shown that common characteristics of this imbalance include an increased Firmicutes/Bacteroidetes ratio, reflecting increased Firmicutes abundance, decreased Bacteroidetes, along with an increase in certain opportunistic pathogens, while beneficial bacteria are reduced (13, 14). At the family and genus levels, microbiota associated with short-chain fatty acid (SCFA) production, such as Muribaculaceae and Bacteroides, tend to decrease, while certain opportunistic pathogens, including Enterobacteriaceae and Clostridium sensu stricto, tend to increase. These changes are closely related to gastrointestinal motility disorders (15, 16).

Following FMT intervention, these structural imbalances gradually recover. At the phylum level, the ratio of Firmicutes to Bacteroidetes tends to normalize, reflecting the reconstruction of intestinal homeostasis. Notably, at the family level, increases in the abundance of key taxa such as Prevotellaceae and Ruminococcaceae, contribute to enhanced the production of short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs) and secondary bile acids. At the genus level, there is a marked restoration of Faecalibacterium and Roseburia, both of which are butyrate-producing bacteria. Butyrate serves as the main energy substrate for colonic epithelial cells, promotes intestinal motility, and enhances barrier function (17). Meanwhile, the proportion of opportunistic pathogens decreases (16, 18). These changes suggest that FMT reshapes the microbiota composition, restores metabolic function, and establishes a foundation for balancing the downstream bile acid profile and activating receptor signaling. Table 1 summarizes the major effects of FMT on gut microbiota in patients with FC (Table 1).

Table 1

| Microbiota level | Changes in FC patients | Post-FMT changes | Potential mechanisms |

|---|---|---|---|

| α-diversity | Reduced richness and evenness | Increased, closer to donors | Restoration of ecological stability |

| β-diversity | Distinct from healthy controls | Shifted toward donor profile | Reconstruction of overall community balance |

| F/B ratio | Elevated (Firmicutes↑, Bacteroidetes↓) | Normalized | Modulation of SCFA production and motility |

| Butyrate producers (e.g., Faecalibacterium, Roseburia) | Decreased | Increased | Enhanced butyrate supply; improved epithelial energy and barrier |

| Conditional pathogens (e.g., Enterobacteriaceae, Clostridium sensu stricto) | Increased | Decreased | Reduced pro-inflammatory activity and harmful metabolites |

| Other key taxa (e.g., Bacteroides, Prevotella) | Bacteroides↓, Prevotella dysregulated | Partially restored | Re-establishment of bile acid metabolism and polysaccharide degradation |

Major effects of fecal microbiota transplantation on gut microbiota diversity and composition.

FC, functional constipation; FMT, fecal microbiota transplantation; F/B, Firmicutes/Bacteroidetes; SCFAs, short-chain fatty acids.

In addition to functional constipation, evidence from other clinical contexts suggests that fecal microbiota transplantation can induce comparable shifts in gut microbial composition. In the study by DuPont et al., which examined microbiota changes following FMT in PD patients, the genera Roseburia and Ruthenibacterium became among the 10 most prevalent taxa during and after treatment, although they were not among the dominant genera at baseline. Roseburia belongs to the butyrate-producing Lachnospiraceae family (Firmicutes phylum), while Ruthenibacterium spp. are members of the Ruminococcaceae family, well known for producing short-chain fatty acids and contributing to gut barrier integrity and immune function. Ruthenibacterium spp. have previously been detected in the intestinal microbiota of PD patients. In addition, Collinsella emerged as one of the most common genera following FMT. Collinsella (Actinomycetota/Actinobacteria) has been associated with protection against SARS-CoV-2 infection and was shown to decrease during weight-loss interventions in obese patients with type 2 diabetes. Other Firmicutes taxa, including Limnochordaceae, Peptostreptococcaceae, and Lactobacillaceae, also increased significantly after FMT. However, there is currently no evidence indicating that increased abundance of members of the Limnochordaceae family confers specific health benefits (19).

3 Changes in bile acid profile

3.1 The impact of FMT on the balance between primary and secondary bile acids

Bile acid metabolism relies on the critical process of the enterohepatic circulation, in which most bile acids are reabsorbed in the terminal ileum via the portal circulation and transported back to the liver (20). Only a small proportion of primary bile acids, such as Cholic Acid (CA) and Chenodeoxycholic Acid (CDCA), escape absorption in the small intestine and enter the colon. There, through enzymatic reactions such as 7α-dehydroxylation mediated by bacterial genera including Clostridium scindens, they are converted into secondary bile acids, including Deoxycholic Acid (DCA) and Lithocholic Acid (LCA) (21, 22). In healthy individuals, secondary bile acids typically dominate the fecal bile acid profile. This is dependent on the cooperative actions of various microbiota species, such as those carrying bile salt hydrolase (BSH), which catalyze the deconjugation reaction and provide substrates for subsequent 7α-dehydroxylation (23, 24).

Research evidence indicates that patients with constipation often exhibit an increased proportion of primary bile acids and a marked reduction in secondary bile acids, suggesting a functional impairment in the bile acid conversion process (25). This imbalance not only indicates the loss of key functional microbiota but may also lead to insufficient activation of downstream receptors such as FXR and TGR5, then affecting intestinal motility and secretory function. FMT can partially restore this imbalance. Experimental studies have shown that FMT elevates secondary bile acid concentrations while reducing primary bile acid proportions in recipient feces, resulting in a bile acid profile that gradually approximates that of healthy donors (26–28). This suggests that FMT not only alters the microbiota composition but also restores the balance between primary and secondary bile acids by rebuilding microbial functional groups, thereby providing a foundation for the activation of FXR/TGR5 signaling and improvement in clinical symptoms.

In addition to primary and secondary bile acids, FMT may also influence other derivatives, such as ursodeoxycholic acid (UDCA). These metabolites play a potential role in maintaining gut barrier integrity and microbiota homeostasis. However, direct evidence linking these metabolites to constipation remains limited (29). Table 2 summarizes the main primary and secondary bile acids, the microbial processes involved, and their major receptor pathways (Table 2).

Table 2

| Bile acid type | Representative molecules | Key taxa/enzymes | Major receptors | Physiological significance |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Primary BAs | CA, CDCA | Synthesized in the liver; secreted as conjugates | FXR (mainly in ileal epithelium), TGR5 (partly) | Feedback regulation of BAs synthesis; maintenance of mucosal barrier |

| Secondary BAs | DCA, LCA | Clostridium scindens and other 7α-dehydroxylating bacteria; require cooperation of BSH-positive strains | TGR5 (enteroendocrine L cells, neurons), FXR (partly) | Activation of GLP-1/5-HT signaling; stimulation of motility and secretion |

| Other derivatives | UDCA, ω-MCA | Produced by various microbial transformations | FXR, TGR5 | Anti-inflammatory effects; modulation of microbiota; potential motility improvement |

Primary and secondary bile acids, related microbiota, and major receptors.

Bas, bile acids; CA, cholic acid; CDCA, chenodeoxycholic acid; DCA, deoxycholic acid; LCA, lithocholic acid; UDCA, ursodeoxycholic acid; ω-MCA, ω-muricholic acid; BSH, bile salt hydrolase; FXR, Farnesoid X receptor; TGR5, Takeda G protein–coupled receptor 5; GLP-1, Glucagon-like peptide-1; 5-HT, 5-hydroxytryptamine.

3.2 The relationship between bile acids and receptor activation

The reestablishment of the ratio between primary and secondary bile acids restores secondary bile acids as effective agonists of TGR5, while maintaining the sustained stimulation of FXR by primary bile acids (30, 31). This indicates that the restoration of the bile acid profile is not only a metabolic outcome but also represents the reestablishment of receptor signaling pathways. Therefore, the therapeutic effect of FMT on FC can be understood as a progressive process: initially, bile acid metabolism is reestablished through microbial modulation, primary and secondary bile acids act as signaling mediators to activate FXR and TGR5 pathways. The following section will elaborate on the specific manifestations of this receptor activation pattern.

4 Activation of FXR/TGR5 receptors

Bile acids, beyond their digestive roles, also function as pivotal signaling molecules in the regulation of intestinal physiology. Among their receptors, FXR and TGR5 are particularly critical, as they not only maintain bile acid homeostasis but also play a central role in regulating intestinal motility. FMT can indirectly influence these signaling pathways by altering the bile acid profile. Several animal studies have consistently shown that after FMT, secondary bile acids increase in the recipient’s feces, leading to activates FXR and TGR5 in both the ileum and colon (6).

4.1 FXR activation pattern and its effects

After FMT, gut microbiota remodeling significantly increases the concentration of CDCA in the ileum (32). CDCA, as an endogenous ligand for FXR, can directly activate FXR (33). Once activated, FXR plays a pivotal role in maintaining bile acid homeostasis by inhibiting the activity of cholesterol 7α-hydroxylase (CYP7A1), while simultaneously facilitating the generation of primary bile acids, including CA and CDCA (34). Furthermore, FXR activation in intestinal epithelial cells stimulates fibroblast growth factor 19 (FGF19) secretion, thereby establishing a “gut–liver axis” feedback loop. This axis further fine-tunes hepatic bile acid synthesis and integrates bile acid signaling with energy metabolism (35).

4.2 TGR5 activation pattern and its effects

Representative secondary bile acids, including DCA and LCA, exhibit high binding affinity for TGR5 and activate this receptor when they accumulate in the colon (36). Activation of TGR5 stimulates the synthesis of cyclic Adenosine Monophosphate (cAMP) through the Gs protein–coupled signaling pathway, which subsequently leading to activation of downstream Protein Kinase A (PKA) (37), ultimately inducing the expression and release of 5-Hydroxytryptamine (5-HT) (38).

5-HT, as a key neurotransmitter in the gut, not only promotes chloride and water secretion, softening stool (39), but also enhances smooth muscle contraction and colonic propulsive motility by stimulating the enteric nervous system. In addition, TGR5 activation stimulates enteroendocrine L cells to release Glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1), which, similar to 5-HT, works in concert to promote motility and secretion (40). Clinical studies have further confirmed that, following FMT treatment, patients with constipation exhibit a significant increase in 5-HT levels within the colonic mucosa, along with enhanced 5-HT expression on intestinal epithelial cell surfaces, thereby effectively enhancing intestinal secretion and propulsive motility (41). Results from animal experiments demonstrate that in TGR5 knockout mice, the colonic propulsion rate increased by only 18% after FMT intervention, which was markedly lower than the 42% observed in wild-type mice (p < 0.05). This provides compelling evidence that TGR5 plays an indispensable role in the pro-motility effects induced by FMT (42, 43).

FXR and TGR5, both bile acid–dependent receptors, cooperate to maintain bile acid homeostasis and intestinal function. FXR activation can upregulate the expression of TGR5, and the coordinated activity of these receptors promotes the GLP-1 secretion from L cells, thereby further enhancing intestinal propulsive function (44). Additionally, the use of an FXR-selective agonist alone has limited effects on metabolic improvement, but when combined with TGR5 activation, it can more effectively correct bile acid imbalance and microbiota abnormalities (45).

4.3 Differences in receptor activation and subtype specificity

Although the involvement of FXR and TGR5 receptors has been confirmed in multiple studies, there are still discrepancies between studies. In animal experiments, both FXR and TGR5 are often activated after FMT (6). However, in clinical patients, the improvement in constipation symptoms following FMT is more strongly associated with the activation of the FXR pathway. This difference may be related to factors such as the donor microbiota composition, the patients’ bile acid levels, and the method of microbiota transplantation (46–48).

Additionally, the dysbiosis patterns of the microbiota differ across constipation subtypes, leading to variations in bile acid metabolites. In slow-transit constipation (STC), the deficiency of secondary bile acids results in impaired TGR5 signaling. FMT can restore its function by rebuilding microbiota that produce secondary bile acids (49, 50). On the other hand, outlet obstruction constipation (OOC) is often accompanied by localized inflammation and barrier damage, making it more reliant on compensatory FXR activation to maintain mucosal barrier integrity and bile acid homeostasis (51).

5 The link between the microbiota–bile acid–receptor axis and constipation improvement

FMT has been shown to significantly increase bowel movement frequency, with studies reporting that nearly 75% of patients achieve at least three spontaneous complete bowel movements per week after treatment and the Wexner Constipation Score (WCS) decreased from 12.12 ± 4.05 before treatment to 7.12 ± 3.52 after treatment (p < 0.05), indicating a significant reduction in the severity of constipation. Stool consistency also improved, with the Bristol Stool Form Scale transitioning from harder types (1–2) to softer types (3–4). In addition to improving bowel movements, FMT also enhanced the patients’ quality of life. The Gastrointestinal Quality of Life Index (GIQLI) score significantly increased, suggesting that patients experienced relief from symptom distress, psychological burden, and daily life impact (7, 48, 52).

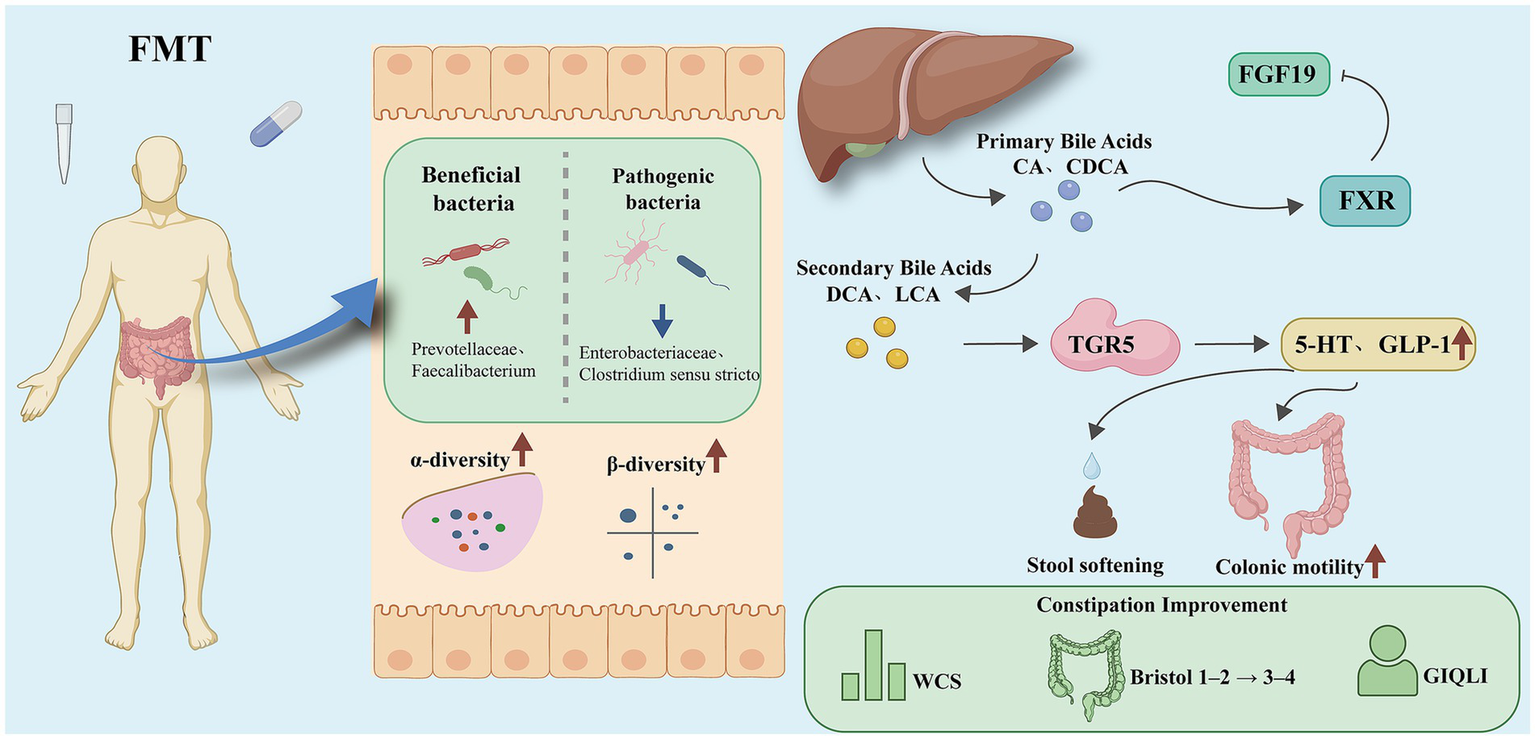

At the mechanistic level, FMT reshapes the composition of the colonic microbiota (22), restores microbiota that produce secondary bile acids, and promotes the reactivation of the bile acid-mediated FXR/TGR5 signaling pathway. This process not only improves the distribution of microbiota-derived metabolites but also enhances intestinal barrier function and colonic propulsion, leading to a reduction in colonic transit time (CTT) (6, 26). While the specific microbiota–metabolite–receptor effect chain still requires further elucidation, existing evidence supports that FMT improves motility and alleviates symptoms through the “microbiota–bile acid–receptor axis.” It is noteworthy that although FMT demonstrates significant clinical efficacy in the short term, its long-term therapeutic effects remain somewhat unstable and uncertain. Follow-up studies have shown that some patients maintain symptom improvement for 3–6 months, while others gradually experience relapse (48). Therefore, the stability of the donor microbiota and its persistent colonization in the recipient’s gut are considered key factors determining long-term efficacy (53). Additionally, factors such as microbiota selection, diet, medications, and the host’s metabolic state may interfere with the colonization and maintenance of the transplanted microbiota. Optimizing donor selection, adopting multiple transplantation strategies, and assessing the baseline microbiota of the recipient could help improve the lasting efficacy of FMT (54, 55). The overall mechanism is summarized in Figure 1.

Figure 1

Schematic diagram of FMT improving FC through the “microbiota–bile acid–FXR/TGR5” axis.

FMT alleviates constipation via the gut microbiota-bile acid-FXR/TGR5-5-HT axis. Overall mechanism framework of Fecal microbiota transplantation (FMT) in functional constipation. FMT reshapes gut microbiota composition by increasing beneficial taxa (e.g., Prevotellaceae, Faecalibacterium) and reducing pathogenic taxa (e.g., Enterobacteriaceae, Clostridium sensu stricto), thereby restoring both α-diversity and β-diversity. Microbial remodeling facilitates bile acid metabolism reconstruction, characterized by reduced primary bile acids [cholic acid (CA), chenodeoxycholic acid (CDCA)] and increased secondary bile acids [deoxycholic acid (DCA), lithocholic acid (LCA)]. These metabolites activate bile acid receptors in distinct regions of the intestine: in the ileum, Farnesoid X Receptor (FXR) induces fibroblast growth factor 19 (FGF19) to maintain bile acid homeostasis, whereas in the colon, Takeda G Protein–Coupled Receptor 5 (TGR5) promotes the secretion of 5-Hydroxytryptamine (5-HT) and Glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1). Through these pathways, stool softening, enhanced colonic motility, and improved bowel habits are achieved, reflected by reduced Wexner constipation scores (WCS), normalized Bristol stool scale (from type 1–2 to type 3–4), and higher gastrointestinal quality of life index (GIQLI).

6 Discussion and outlook

This article reviews the mechanisms by which FMT influences functional constipation, emphasizing the critical role of the microbiota–bile acid–receptor axis in symptom improvement. Existing evidence shows that FMT can significantly improve the diversity of the gut microbiota, reshaping its structure to more closely resemble that of a healthy donor (8, 16, 18). This creates favorable conditions for bile acid conversion an SCFA production.

The restoration of bile acid metabolism represents a critical mechanism through which FMT alleviates constipation. Patients with FC commonly exhibit an imbalance in bile acid composition, with elevated primary bile acids and reduced secondary bile acids (25). Through FMT, the concentration of secondary bile acids, such as DCA and LCA, is increased, thereby promoting intestinal secretion and motility while engaging bile acid receptors, TGR5 in the colon and FXR in the ileum, to modulate gut function. Animal studies also confirm that both FXR and TGR5 pathways are activated after FMT (6).

At the pharmacological level, research targeting bile acid receptors offers new perspectives for treating FC. FXR agonists, such as obeticholic acid, can improve the intestinal barrier by regulating bile acid synthesis (56). TGR5 agonists, like INT-777, enhance the secretion of 5-HT and GLP-1, promoting intestinal motility (57). In animal experiments, the dual agonist INT-767, which simultaneously targets FXR and TGR5, has been shown to produce a more pronounced pro-motility effect (58, 59). However, single-agent treatments have limitations in efficacy (60). Therefore, the combined application of FMT and targeted drugs holds promise in not only improving microbiota imbalance but also enhancing receptor signaling, potentially leading to more sustained and stable therapeutic effects.

Beyond functional constipation, evidence from other disease settings offers valuable complementary insights into the clinical outcomes of fecal microbiota transplantation. In a systematic review evaluating the safety of fecal microbiota transplantation (FMT) for the treatment of Parkinson’s disease (PD), it was noted that stool frequency and quality of life improved significantly in PD patients treated with FMT compared with control groups (61, 62). Evidence regarding changes in Bristol Stool Scale (BSS) scores, however, remains limited, and findings on stool consistency are inconclusive. Differences in alpha diversity between the FMT and placebo groups were less pronounced than changes in beta diversity. Reductions in levodopa-equivalent daily dose (LEDD) and in Beck Anxiety Inventory (BAI) scores were observed in the FMT group at 12 months and 6 months, respectively, compared with placebo. In contrast, complete bowel movements remained more frequent in the placebo group than in the FMT group up to 12 months (63).

At the same time, clinical outcomes following fecal microbiota transplantation show considerable variability across studies, underscoring limitations in the current evidence base. Non-Motor Symptoms Scale (NMSS) scores increased in the FMT group compared with placebo at 6 months in the study by Scheperjans et al., whereas in the study by DuPont et al., subjective non-motor symptoms assessed using visual analog scales improved in the FMT group. In the study by Segal et al., the follow-up duration was approximately 24 weeks. Overall, additional research is needed to clarify long-term efficacy, durability of response, and safety (63).

In addition to functional and metabolic alterations, intestinal barrier impairment and low-grade inflammation may also contribute to constipation-related symptoms. Bellini et al. reported that patients with Parkinson’s disease exhibit disrupted epithelial integrity accompanied by gut microbiota dysbiosis and enteric glial activation. Although derived from Parkinson’s disease, these findings suggest that microbial imbalance may be linked to mucosal dysfunction and neuro-immune alterations, providing complementary mechanistic support for the potential benefits of FMT (64).

The stability of the donor microbiota and its persistent colonization in the recipient’s gut are key factors, while individual differences, such as diet, can also affect the sustainability of FMT’s efficacy (54). Therefore, future research should further optimize areas such as donor selection (e.g., microbiota that produce secondary bile acids or butyrate-producing bacteria) (12, 65), transplantation methods, and frequency (66, 67). Additionally, exploring the combined use of dietary interventions, probiotics, or prebiotics could help enhance and maintain the therapeutic effects of FMT (68, 69).

Future research directions include: ① Conducting large-scale, multi-center, randomized controlled trials to authenticate the long-term therapeutic safety and efficacy of FMT. ② Applying multi-omics approaches to elucidate causal relationships within the microbiota–bile acid–receptor axis. ③ Exploring personalized intervention strategies, including efficacy prediction and patient stratification based on bile acid profiles, downstream FXR/TGR5 signaling, and microbiota biomarkers. ④ Combining synthetic biology and customized microbial interventions to advance precision treatment for functional constipation.

Overall, FMT can improve functional constipation by reshaping the gut microbiota, restoring the balance between primary and secondary bile acids, and activating the FXR/TGR5 signaling pathway. Whether as a standalone intervention or in combination with targeted drugs, FMT shows great promise and offers new clinical value for bile acid receptors as therapeutic targets.

Statements

Author contributions

DW: Writing – original draft. SL: Validation, Writing – review & editing. YW: Investigation, Writing – review & editing. HZ: Writing – review & editing, Conceptualization. KZ: Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declared that financial support was received for this work and/or its publication. This study was supported by Project of the State Administration of Traditional Chinese Medicine of China (Grant No. GZY-KJS-SD-2024-027).

Conflict of interest

The author(s) declared that this work was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declared that Generative AI was not used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1.

Brenner DM Corsetti M Drossman D Tack J Wald A . Perceptions, definitions, and therapeutic interventions for occasional constipation: a Rome working group consensus document. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. (2024) 22:397–412. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2023.08.044,

2.

Yun Q Wang S Chen S Luo H Li B Yip P et al . Constipation preceding depression: a population-based cohort study. EClinicalMedicine. (2024) 67:102371. doi: 10.1016/j.eclinm.2023.102371,

3.

Verheyden A Hreinsson JP Bangdiwala SI Drossman D Simrén M Sperber AD et al . Occasional constipation: prevalence and impact in the Rome IV global epidemiology study. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. (2025) 30:27. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2025.09.027

4.

Huang L Zhu Q Qu X Qin H . Microbial treatment in chronic constipation. Sci China Life Sci. (2018) 61:744–52. doi: 10.1007/s11427-017-9220-7,

5.

Zhang X Yang H Zheng J Jiang N Sun G Bao X et al . Chitosan oligosaccharides attenuate loperamide-induced constipation through regulation of gut microbiota in mice. Carbohydr Polym. (2021) 253:117218. doi: 10.1016/j.carbpol.2020.117218,

6.

Han B Lv X Liu G Li S Fan J Chen L et al . Gut microbiota-related bile acid metabolism-FXR/TGR5 axis impacts the response to anti-α4β7-integrin therapy in humanized mice with colitis. Gut Microbes. (2023) 15:2232143. doi: 10.1080/19490976.2023.2232143,

7.

Xie L Xu C Fan Y Li Y Wang Y Zhang X et al . Effect of fecal microbiota transplantation in patients with slow transit constipation and the relative mechanisms based on the protein digestion and absorption pathway. J Transl Med. (2021) 19:490. doi: 10.1186/s12967-021-03152-2,

8.

Xu Y Shao M Fang X Tang W Zhou C Hu X et al . Antipsychotic-induced gastrointestinal hypomotility and the alteration in gut microbiota in patients with schizophrenia. Brain Behav Immun. (2022) 99:119–29. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2021.09.014,

9.

Yadegar A Pakpoor S Ibrahim FF Nabavi-Rad A Cook L Walter J et al . Beneficial effects of fecal microbiota transplantation in recurrent clostridioides difficile infection. Cell Host Microbe. (2023) 31:695–711. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2023.03.019,

10.

Ng HY Zhang L Tan JT Hui RWH Yuen MF Seto WK et al . Gut microbiota predicts treatment response to empagliflozin among MASLD patients without diabetes mellitus. Liver Int. (2025) 45:e70023. doi: 10.1111/liv.70023,

11.

Tian L Wang XW Wu AK Fan Y Friedman J Dahlin A et al . Deciphering functional redundancy in the human microbiome. Nat Commun. (2020) 11:6217. doi: 10.1038/s41467-020-19940-1,

12.

Ye H Ghosh TS Hueston CM Vlckova K Golubeva AV Hyland NP et al . Engraftment of aging-related human gut microbiota and the effect of a seven-species consortium in a pre-clinical model. Gut Microbes. (2023) 15:2282796. doi: 10.1080/19490976.2023.2282796,

13.

Silva-Veiga FM Marinho TS de Souza-Mello V Aguila MB Mandarim-de-Lacerda CA . Tirzepatide, a dual agonist of glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide (GIP) and glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1), positively impacts the altered microbiota of obese, diabetic, ovariectomized mice. Life Sci. (2025) 361:123310. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2024.123310

14.

Meng JX Wei XY Guo H Chen Y Wang W Geng HL et al . Metagenomic insights into the composition and function of the gut microbiota of mice infected with Toxoplasma gondii. Front Immunol. (2023) 14:1156397. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2023.1156397,

15.

Fan Y Xu C Xie L Wang Y Zhu S An J et al . Abnormal bile acid metabolism is an important feature of gut microbiota and fecal metabolites in patients with slow transit constipation. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. (2022) 12:956528. doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2022.956528,

16.

Zheng F Yang Y Lu G Tan JS Mageswary U Zhan Y et al . Metabolomics insights into gut microbiota and functional constipation. Meta. (2025) 15:269. doi: 10.3390/metabo15040269,

17.

Deng M Ye J Zhang R Zhang S Dong L Su D et al . Shatianyu (Citrus grandis L. Osbeck) whole fruit alleviated loperamide-induced constipation via enhancing gut microbiota-mediated intestinal serotonin secretion and mucosal barrier homeostasis. Food Funct. (2024) 15:10614–27. doi: 10.1039/d4fo02765e,

18.

Tan S Peng C Lin X Peng C Yang Y Liu S et al . Clinical efficacy of non-pharmacological treatment of functional constipation: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. (2025) 15:1565801. doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2025.1565801,

19.

DuPont HL Suescun J Jiang ZD Brown EL Essigmann HT Alexander AS et al . Fecal microbiota transplantation in Parkinson's disease – a randomized repeat-dose, placebo-controlled clinical pilot study. Front Neurol. (2023) 14:1104759. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2023.1104759,

20.

Kunst RF Verkade HJ Oude Elferink RPJ van de Graaf SFJ . Targeting the four pillars of enterohepatic bile salt cycling; lessons from genetics and pharmacology. Hepatology. (2021) 73:2577–85. doi: 10.1002/hep.31651,

21.

Yang C Huang S Lin Z Chen H Xu C Lin Y et al . Polysaccharides from Enteromorpha prolifera alleviate hypercholesterolemia via modulating the gut microbiota and bile acid metabolism. Food Funct. (2022) 13:12194–207. doi: 10.1039/d2fo02079c,

22.

Hou JJ Wang X Wang YM Wang BM . Interplay between gut microbiota and bile acids in diarrhoea-predominant irritable bowel syndrome: a review. Crit Rev Microbiol. (2022) 48:696–713. doi: 10.1080/1040841X.2021.2018401,

23.

Cai J Rimal B Jiang C Chiang JYL Patterson AD . Bile acid metabolism and signaling, the microbiota, and metabolic disease. Pharmacol Ther. (2022) 237:108238. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2022.108238,

24.

Collins SL Stine JG Bisanz JE Okafor CD Patterson AD . Bile acids and the gut microbiota: metabolic interactions and impacts on disease. Nat Rev Microbiol. (2023) 21:236–47. doi: 10.1038/s41579-022-00805-x,

25.

Duan X Zheng L Zhang X Wang B Xiao M Zhao W et al . A membrane-free liver-gut-on-chip platform for the assessment on dysregulated mechanisms of cholesterol and bile acid metabolism induced by PM2.5. ACS Sens. (2020) 5:3483–92. doi: 10.1021/acssensors.0c01524,

26.

Xu Y Wang J Wu X Jing H Zhang S Hu Z et al . Gut microbiota alteration after cholecystectomy contributes to post-cholecystectomy diarrhea via bile acids stimulating colonic serotonin. Gut Microbes. (2023) 15:2168101. doi: 10.1080/19490976.2023.2168101,

27.

Chen L Ye Z Li J Wang L Chen Y Yu M et al . Gut bacteria Prevotellaceae related lithocholic acid metabolism promotes colonic inflammation. J Transl Med. (2025) 23:55. doi: 10.1186/s12967-024-05873-6,

28.

Lin Z Feng Y Wang J Men Z Ma X . Microbiota governs host chenodeoxycholic acid glucuronidation to ameliorate bile acid disorder induced diarrhea. Microbiome. (2025) 13:36. doi: 10.1186/s40168-024-02011-8,

29.

Mao Z Hui H Zhao X Xu L Qi Y Yin L et al . Protective effects of dioscin against Parkinson's disease via regulating bile acid metabolism through remodeling gut microbiome/GLP-1 signaling. J Pharm Anal. (2023) 13:1153–67. doi: 10.1016/j.jpha.2023.06.007,

30.

Zhao S Lin H Li W Xu X Wu Q Wang Z et al . Post sleeve gastrectomy-enriched gut commensal Clostridia promotes secondary bile acid increase and weight loss. Gut Microbes. (2025) 17:2462261. doi: 10.1080/19490976.2025.2462261,

31.

Song L Hou Y Xu D Dai X Luo J Liu Y et al . Hepatic FXR-FGF4 is required for bile acid homeostasis via an FGFR4-LRH-1 signal node under cholestatic stress. Cell Metab. (2025) 37:104–120.e9. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2024.09.008,

32.

Zhao C Bao L Qiu M Wu K Zhao Y Feng L et al . Commensal cow Roseburia reduces gut-dysbiosis-induced mastitis through inhibiting bacterial translocation by producing butyrate in mice. Cell Rep. (2022) 41:111681. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2022.111681,

33.

Cao S Meng X Li Y Sun L Jiang L Xuan H et al . Bile acids elevated in chronic Periaortitis could activate Farnesoid-X-receptor to suppress IL-6 production by macrophages. Front Immunol. (2021) 12:632864. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2021.632864,

34.

Donepudi AC Boehme S Li F Chiang JY . G-protein-coupled bile acid receptor plays a key role in bile acid metabolism and fasting-induced hepatic steatosis in mice. Hepatology. (2017) 65:813–27. doi: 10.1002/hep.28707,

35.

Simbrunner B Trauner M Reiberger T . Review article: therapeutic aspects of bile acid signalling in the gut-liver axis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. (2021) 54:1243–62. doi: 10.1111/apt.16602,

36.

Han Z Yao L Zhong Y Xiao Y Gao J Zheng Z et al . Gut microbiota mediates the effects of curcumin on enhancing Ucp1-dependent thermogenesis and improving high-fat diet-induced obesity. Food Funct. (2021) 12:6558–75. doi: 10.1039/d1fo00671a,

37.

Zhao C Wu K Hao H Zhao Y Bao L Qiu M et al . Gut microbiota-mediated secondary bile acid alleviates Staphylococcus aureus-induced mastitis through the TGR5-cAMP-PKA-NF-κB/NLRP3 pathways in mice. NPJ Biofilms Microbiomes. (2023) 9:8. doi: 10.1038/s41522-023-00374-8,

38.

Zhang D Chen K Yu Y Feng R Cui SW Zhou X et al . Polysaccharide from Aloe vera gel improves intestinal stem cells dysfunction to alleviate intestinal barrier damage via 5-HT. Food Res Int. (2025) 214:116675. doi: 10.1016/j.foodres.2025.116675

39.

Liu J Cao Q Ewing M Zuo Z Kennerdell JR Finkel T et al . ATP depletion in anthrax edema toxin pathogenesis. PLoS Pathog. (2025) 21:e1013017. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1013017,

40.

Wang Q Lin H Shen C Zhang M Wang X Yuan M et al . Gut microbiota regulates postprandial GLP-1 response via ileal bile acid-TGR5 signaling. Gut Microbes. (2023) 15:2274124. doi: 10.1080/19490976.2023.2274124

41.

Fu R Li Z Zhou R Li C Shao S Li J . The mechanism of intestinal flora dysregulation mediated by intestinal bacterial biofilm to induce constipation. Bioengineered. (2021) 12:6484–98. doi: 10.1080/21655979.2021.1973356,

42.

Zhang N Guo D Guo N Yang D Yan H Yao J et al . Integration of UPLC-MS/MS-based metabolomics and desorption electrospray ionization-mass spectrometry imaging reveals that Shouhui Tongbian capsule alleviates slow transit constipation by regulating bile acid metabolism. J Chromatogr B Analyt Technol Biomed Life Sci. (2024) 1247:124331. doi: 10.1016/j.jchromb.2024.124331,

43.

Zhu X Dai X Zhao L Li J Zhu Y He W et al . Quercetin activates energy expenditure to combat metabolic syndrome through modulating gut microbiota-bile acids crosstalk in mice. Gut Microbes. (2024) 16:2390136. doi: 10.1080/19490976.2024.2390136,

44.

Pathak P Xie C Nichols RG Ferrell JM Boehme S Krausz KW et al . Intestine Farnesoid X receptor agonist and the gut microbiota activate G-protein bile acid receptor-1 signaling to improve metabolism. Hepatology. (2018) 68:1574–88. doi: 10.1002/hep.29857,

45.

Comeglio P Cellai I Mello T Filippi S Maneschi E Corcetto F et al . INT-767 prevents NASH and promotes visceral fat brown adipogenesis and mitochondrial function. J Endocrinol. (2018) 238:107–27. doi: 10.1530/JOE-17-0557,

46.

Fiorucci S Distrutti E Carino A Zampella A Biagioli M . Bile acids and their receptors in metabolic disorders. Prog Lipid Res. (2021) 82:101094. doi: 10.1016/j.plipres.2021.101094,

47.

Feng R Zhu Q Wang A Wang H Wang J Chen P et al . Effect of fecal microbiota transplantation on patients with sporadic amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. BMC Med. (2024) 22:566. doi: 10.1186/s12916-024-03781-6,

48.

Wang L Xu Y Li L Yang B Zhao D Ye C et al . The impact of small intestinal bacterial overgrowth on the efficacy of fecal microbiota transplantation in patients with chronic constipation. MBio. (2024) 15:e0202324. doi: 10.1128/mbio.02023-24,

49.

Spatz M Ciocan D Merlen G Rainteau D Humbert L Gomes-Rochette N et al . Bile acid-receptor TGR5 deficiency worsens liver injury in alcohol-fed mice by inducing intestinal microbiota dysbiosis. JHEP Rep. (2021) 3:100230. doi: 10.1016/j.jhepr.2021.100230,

50.

Zhang C Wang L Liu X Wang G Zhao J Chen W . Bifidobacterium longum subsp. longum relieves loperamide hydrochloride-induced constipation in mice by enhancing bile acid dissociation. Food Funct. (2025) 16:297–313. doi: 10.1039/d4fo04660a,

51.

Dong X Qi M Cai C Zhu Y Li Y Coulter S et al . Farnesoid X receptor mediates macrophage-intrinsic responses to suppress colitis-induced colon cancer progression. JCI Insight. (2024) 9:e170428. doi: 10.1172/jci.insight.170428

52.

Zhang Q Zhao W Luo J Shi S Niu X He J et al . Synergistic defecation effects of Bifidobacterium animalis subsp. lactis BL-99 and fructooligosaccharide by modulating gut microbiota. Front Immunol. (2025) 15:1520296. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2024.1520296,

53.

El-Salhy M Winkel R Casen C Hausken T Gilja OH Hatlebakk JG . Efficacy of Fecal microbiota transplantation for patients with irritable bowel syndrome at 3 years after transplantation. Gastroenterology. (2022) 163:982–994.e14. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2022.06.020,

54.

Zhang B Li J Fu J Shao L Yang L Shi J . Interaction between mucus layer and gut microbiota in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: soil and seeds. Chin Med J. (2023) 136:1390–400. doi: 10.1097/CM9.0000000000002711,

55.

Wilson BC Vatanen T Jayasinghe TN Leong KSW Derraik JGB Albert BB et al . Strain engraftment competition and functional augmentation in a multi-donor fecal microbiota transplantation trial for obesity. Microbiome. (2021) 9:107. doi: 10.1186/s40168-021-01060-7,

56.

De Vito F Marasco R Suraci E Facciolo A Hribal ML Sesti G et al . FXR stimulation by obeticholic acid treatment restores gut mucosa functional and structural integrity in individuals with altered glucose tolerance. Diabetes. (2025) 74:1399–410. doi: 10.2337/db25-0035,

57.

Yue Z Zhao F Guo Y Zhang Y Chen Y He L et al . Lactobacillus reuteri JCM 1112 ameliorates chronic acrylamide-induced glucose metabolism disorder via the bile acid-TGR5-GLP-1 axis and modulates intestinal oxidative stress in mice. Food Funct. (2024) 15:6450–8. doi: 10.1039/d4fo01061b,

58.

Ramachandran P Brice M Sutherland EF Hoy AM Papachristoforou E Jia L et al . Aberrant basement membrane production by HSCs in MASLD is attenuated by the bile acid analog INT-767. Hepatol Commun. (2024) 8:e0574. doi: 10.1097/HC9.0000000000000574,

59.

Chen C Zhang B Tu J Peng Y Zhou Y Yang X et al . Discovery of 4-aminophenylacetamide derivatives as intestine-specific Farnesoid X receptor antagonists for the potential treatment of nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. Eur J Med Chem. (2024) 264:115992. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2023.115992,

60.

Almeqdadi M Gordon FD . Farnesoid X receptor agonists: a promising therapeutic strategy for gastrointestinal diseases. Gastro Hep Adv. (2023) 3:344–52. doi: 10.1016/j.gastha.2023.09.013,

61.

Segal A Zlotnik Y Moyal-Atias K Abuhasira R Ifergane G . Fecal microbiota transplant as a potential treatment for Parkinson's disease – a case series. Clin Neurol Neurosurg. (2021) 207:106791. doi: 10.1016/j.clineuro.2021.106791,

62.

Kuai XY Yao XH Xu LJ Zhou YQ Zhang LP Liu Y et al . Evaluation of fecal microbiota transplantation in Parkinson's disease patients with constipation. Microb Cell Factories. (2021) 20:98. doi: 10.1186/s12934-021-01589-0,

63.

Scheperjans F Levo R Bosch B Lääperi M Pereira PAB Smolander OP et al . Fecal microbiota transplantation for treatment of Parkinson disease: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Neurol. (2024) 81:925–38. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2024.2305,

64.

Bellini G Benvenuti L Ippolito C Frosini D Segnani C Rettura F et al . Intestinal histomorphological and molecular alterations in patients with Parkinson's disease. Eur J Neurol. (2023) 30:3440–50. doi: 10.1111/ene.15607,

65.

Shtossel O Turjeman S Riumin A Goldberg MR Elizur A Bekor Y et al . Recipient-independent, high-accuracy FMT-response prediction and optimization in mice and humans. Microbiome. (2023) 11:181. doi: 10.1186/s40168-023-01623-w,

66.

Li N Zuo B Huang S Zeng B Han D Li T et al . Spatial heterogeneity of bacterial colonization across different gut segments following inter-species microbiota transplantation. Microbiome. (2020) 8:161. doi: 10.1186/s40168-020-00917-7,

67.

He R Li P Wang J Cui B Zhang F Zhao F . The interplay of gut microbiota between donors and recipients determines the efficacy of fecal microbiota transplantation. Gut Microbes. (2022) 14:2100197. doi: 10.1080/19490976.2022.2100197,

68.

Lai H Li Y He Y Chen F Mi B Li J et al . Effects of dietary fibers or probiotics on functional constipation symptoms and roles of gut microbiota: a double-blinded randomized placebo trial. Gut Microbes. (2023) 15:2197837. doi: 10.1080/19490976.2023.2197837

69.

Shao T Hsu R Hacein-Bey C Zhang W Gao L Kurth MJ et al . The evolving landscape of fecal microbial transplantation. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol. (2023) 65:101–20. doi: 10.1080/19490976.2023.2197837

Summary

Keywords

bile acids, Farnesoid X receptor, fecal microbiota transplantation, functional constipation, Takeda G protein–coupled receptor 5

Citation

Wen D, Liu S, Wu Y, Zhang H and Zhang K (2026) Fecal microbiota transplantation improves functional constipation through the gut microbiome–bile acid–receptor axis. Front. Med. 13:1751593. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2026.1751593

Received

21 November 2025

Revised

07 January 2026

Accepted

09 January 2026

Published

09 February 2026

Volume

13 - 2026

Edited by

Massimo Bellini, University of Pisa, Italy

Reviewed by

Lorenzo Bini, University of Pisa, Italy

Updates

Copyright

© 2026 Wen, Liu, Wu, Zhang and Zhang.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Kun Zhang, qdcwssrs@outlook.com

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.