Abstract

Background:

Early-life exposures and interventions establish essential pathways which determine children’s development across respiratory, allergic, and growth pathways. The scientists conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis which combined multiple studies to examine how nutritional interventions and viral prophylaxis and probiotics and environmental exposures and allergen exposures and clinical factors in infants affect asthma and wheeze and atopy and growth outcomes.

Methods:

The research team examined 51 studies which they categorized into eight different research areas. The researchers conducted random effects meta-analyses with inverse variance method to calculate pooled odds ratios (ORs) which included 95% confidence intervals (CIs). The researchers used I2 statistics to measure heterogeneity while they used funnel plots and Egger’s test to assess publication bias.

Results:

The nutritional interventions during pregnancy (OR = 0.89, 95% CI: 0.74–1.07, I2 = 68%) and early probiotics/microbiota modulation (OR = 1.10, 95% CI: 0.84–1.43, I2 = 96%) failed to show any significant results. The combination of viral prophylaxis with maternal influenza vaccination protected against wheeze and asthma and LRTI development (OR = 0.78, 95% CI: 0.72–0.85, I2 = 68%). The presence of early-life respiratory viral infections raised the likelihood of developing wheeze and asthma (OR = 1.59, 95% CI: 1.39–1.82, I2 = 90%) which accompanied allergen/atopy exposures (OR = 1.40, 95% CI: 1.30–1.50) and environmental exposures (OR = 1.34, 95% CI: 1.27–1.42) and infant clinical factors (OR = 1.29, 95% CI: 1.13–1.46, I2 = 82%). The long-term cohort studies established that early-life risk factors maintain a consistent impact on the development of asthma and allergic conditions (OR = 1.41, 95% CI: 1.35–1.48). The studies on viral prophylaxis and respiratory infections and allergen exposure demonstrated evidence of publication bias.

Conclusion:

Research shows that early-life exposure to viral infections and allergens and environmental pollutants and infant clinical factors establishes strong links to the development of respiratory disorders and allergic diseases in children. The nutritional and probiotic treatments produced restricted and unstable results which demonstrate the requirement for specific preventive methods that should be implemented during early life.

1 Introduction

The early factors of respiratory susceptibility are getting more attention as childhood asthma remains a significant worldwide health concern (1–5). A large amount of epidemiological data suggests that the path toward asthma may begin in infancy, a time of development when the immunological and respiratory systems are more vulnerable to outside disturbances. Acute respiratory infections, especially those brought on by RSV, influenza, and other viral pathogens, have become prominent early-life exposures that can influence prolonged airway outcomes among these disruptions (6–9). Prophylactic trials have demonstrated that averting serious RSV illness in infancy lowers recurrent wheezing and hospitalization, making early-life RSV encounter one of the most frequently implicated viral determinants (10–12). In a similar vein, it has been demonstrated that maternal immunization can modify influenza-related respiratory morbidity in infancy, resulting in a considerable reduction in hospitalizations for respiratory tract infections and newborn influenza cases (13–15). The concept that early respiratory infections have significant downstream impacts on airway health and the occurrence of asthma is backed by all of these data.

Trials assessing perinatal nutritional modification offer further mechanistic knowledge. The idea that prenatal immunological programming affects postnatal respiratory consequences is supported by research showing that fish oil intake during pregnancy reduces chronic wheezing and asthma in children (16–19). Similar directionally positive impacts on early wheezing are shown by vitamin D trials, indicating that biological processes associated with infection susceptibility also intersect with asthma incidence (20–23). The interdependence of microbial exposures, immunological maturation, and atopic illness, all important components in asthma pathophysiology, is further highlighted by parallel data from early-life probiotic studies that show decreases in IgE-linked eczema and early atopic conditions (16, 17, 24–28).

Furthermore, studies focusing on airway physiology support the idea that early disruptions could affect subsequent respiratory traits. While high-intensity physical activity increases airway responsiveness in sedentary children (29–32), airway-hyperresponsiveness-guided asthma therapy enhances lung function metrics in school-age children (13–15, 18, 19). The basic foundation that unites these trials is that if early viral infection plays a role in the pathophysiology of asthma, then altering viral contact, infection intensity, or the host inflammatory milieu during initial stages might impact subsequent respiratory danger. Although individual trials provide valuable insights, overall interpretation is challenging due to variations in the nature, timing, magnitude, and outcome definitions. We compiled high-quality RCTs to investigate the potential link between early-life respiratory infections and subsequent wheezing and asthma in order to shed light on these trends. A variety of preventive measures targeted at altering early respiratory exposures are examined in this meta-analysis, which evaluates their cumulative connection with ongoing asthma-related consequences.

2 Methodology

2.1 Study design

This systematic review and meta-analysis were carefully designed and reported in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA 2020) standards.

2.2 Search strategy

A thorough search was carried out using PubMed/MEDLINE, Scopus, Web of Science, Cochrane CENTRAL, and ClinicalTrials.gov from inception to December 2024. Search queries included controlled vocabulary (MeSH) and free-text terms such as: “early-life infection,” “respiratory tract infection,” “childhood asthma,” “wheezing,” “RSV prophylaxis,” “maternal vaccination,” “maternal supplementation,” “vitamin D,” “fish oil,” “probiotics,” “palivizumab,” “exercise intervention,.” Geographical or linguistic limitations were not imposed.

2.3 Eligibility criteria

Randomized controlled trials and observational studies that enrolled participants from prenatal to age 12 and assessed therapies that could change the timing, intensity, or tendency of early-life respiratory illnesses were eligible. Asthma, recurrent wheezing, respiratory hospitalization, atopic disease, or lung-function outcomes had to be reported in the trials, and they had to include extractable numerical data that could be used to calculate effect sizes using standardized mean differences. Studies that did not include early-life subjects, had limited outcome reporting, employed observational or quasi-experimental designs, or lacked a comparison group were disqualified.

2.4 Data extraction

A uniform template was used by a reviewer to extract data individually. Study design, sample size, intervention and control characteristics, geographic region, age at intervention or follow-up, respiratory infection type, severity characterization, definitions of asthma or wheeze outcomes, length of follow-up, and year of publication were among the variables that were obtained. To guarantee uniformity in stratified analyses, all retrieved variables were predefined. Conflicts were settled by dialog and agreement.

2.5 Quality assessment

The Cochrane RoB 2.0 tool was used to evaluate bias risk. The GRADE paradigm was used for rating the degree of certainty of the evidence, taking into account publication bias, indirectness, imprecision, risk of bias, and inconsistency.

2.6 Statistical analysis

A random-effects model with inverse-variance weighting was used to produce effect estimates. To account for discrepancies in outcome assessment between trials, OR and associated 95% confidence intervals were computed. To evaluate heterogeneity, the I2 statistic was employed. Age during infection or exposure, kind of respiratory illness, extent of infection, definition of asthma outcome, regional or socioeconomic context, length of follow-up, and publication time were all assessed in prespecified subgroup analyses. Publication bias was assessed via visual analysis of funnel plots. RevMan 5.4 was used for statistical analysis.

3 Results

3.1 Study selection

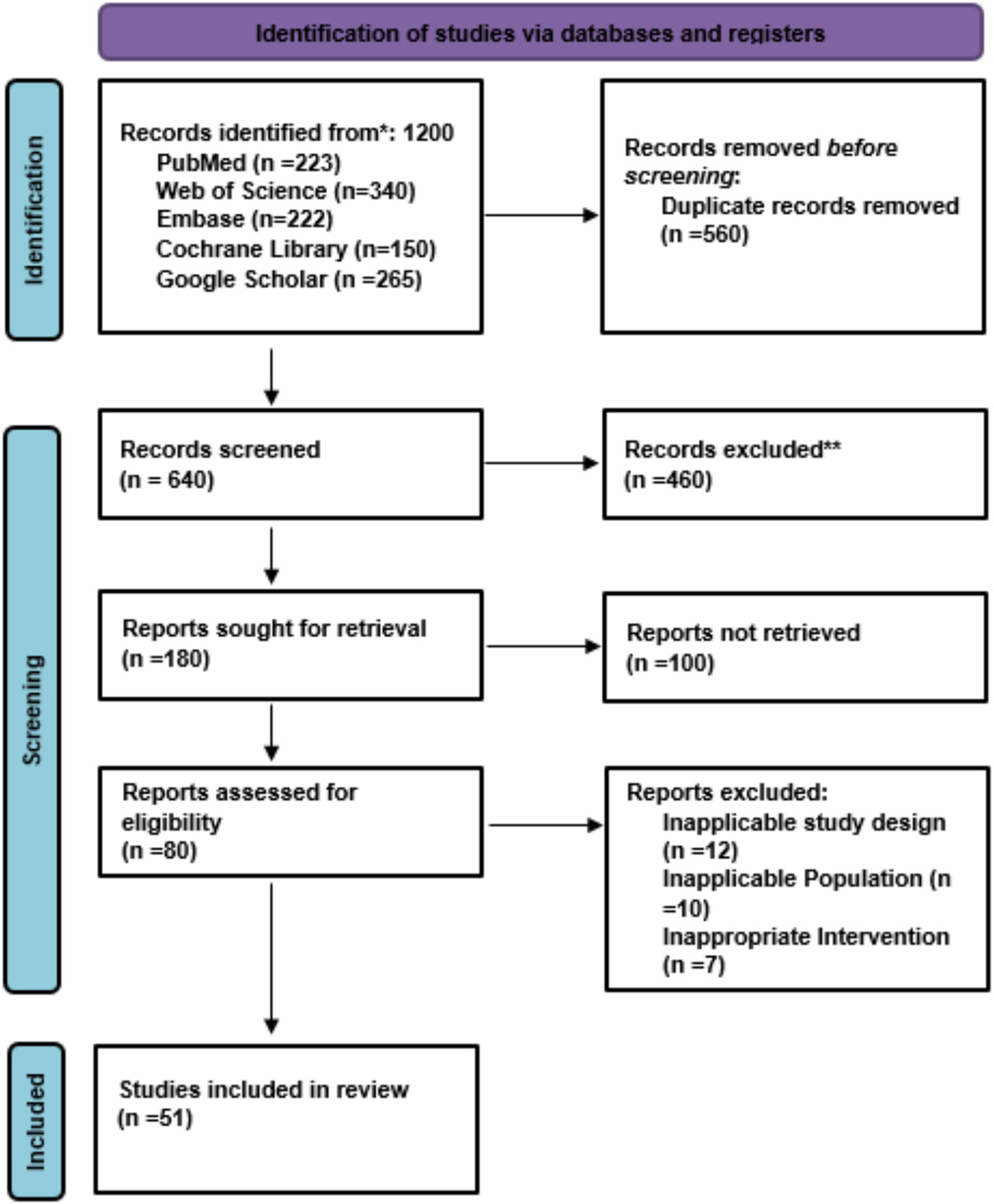

The overall systematic search process from one of the databases identified a total of several records, out of which 51 randomized controlled trials and clinical cohort studies were found to meet the appropriate criteria for inclusion and hence were the ones considered for this meta-analysis. One the other hand, studies reporting no relevant outcomes (asthma, wheezing, or atopic disease), non-randomized designs, or no suitable comparators were excluded from the analysis. Among others, the exclusion of certain studies comprised early observational studies on RSV without outcome reporting, small pilot trials lacking statistical power and studies outside the relevant age range (<1 month or >12 years). Figure 1 illustrates a flow diagram of the search, screening, eligibility, and inclusion process (Figure 1).

Figure 1

PRISMA flow chart of study selection.

3.2 Characteristics of studies on early-life respiratory infections and childhood asthma

The studies that examine how respiratory infections during early life affect the development of asthma in children use both experimental research methods and observational research methods. The randomized controlled trials (RCTs) tested various interventions on pregnant women and preterm infants and high-risk children who received fish oil-derived n-3 fatty acids and vitamin D, probiotics, and palivizumab, motavizumab, and influenza vaccination. The study enrolled participants with sample sizes that ranged between 132 to 2,116 who received interventions starting from mid-pregnancy until their first year of life or during their seasonal RSV/influenza exposure. The study assessed four different outcomes, including persistent wheeze and asthma incidence and recurrent wheezing and allergic diseases. The observational studies, which included prospective and longitudinal and registry-based and population-based cohort studies, followed children from their birth until they reached adulthood, with study participants numbering between hundreds and more than 1 million. The research studies investigated how natural environments affect people through their respiratory infections and allergen exposure, antibiotic consumption, air pollution, and home environmental conditions. The evidence from both experimental studies and observational studies shows that early-life infections and environmental exposures result in increased asthma risk and allergic conditions that persist throughout childhood and later life (Table 1).

Table 1

| Author(s) | Year | Country | Study Type & Population | Sample Size | Duration | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bisgaard et al. (79) | 2016 | Denmark | Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial; pregnant women | 736 | From week 24 of pregnancy until 1 week after birth | Reduced risk of persistent wheeze or asthma in offspring by age 3 years |

| Litonjua et al. (41) | 2014 | USA | Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial; pregnant women | 876 | From 10–18 weeks gestation until delivery | Designed to assess primary prevention of asthma and allergies in children; results pending at study design stage |

| Roth et al. (35) | 2018 | Bangladesh | Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial; pregnant and lactating women | 1,300 | From 17–24 weeks gestation through 26 weeks postpartum | No significant effect on infant growth at 1 year; vitamin D levels increased safely |

| Simoes et al. (42) | 2007 | Multicenter (Europe & USA) | Randomized, placebo-controlled trial; infants born preterm | 1,502 | Monthly injections during RSV season | Reduced RSV hospitalization and subsequent recurrent wheezing in high-risk infants |

| Blanken et al. (36) | 2013 | Netherlands | Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial; healthy preterm infants | 429 | During first RSV season | Significantly reduced recurrent wheeze through first year of life |

| Feltes et al. (43) | 2011 | Multicenter (USA & Canada) | Randomized, double-blind, active-controlled trial; children with congenital heart disease | 1,287 | RSV season (monthly injections) | Motavizumab non-inferior to Palivizumab for preventing serious RSV disease |

| Madhi et al. (37) | 2014 | South Africa | Randomized, placebo-controlled trial; pregnant women | 2,116 | From 20–36 weeks gestation until delivery | Reduced influenza illness in mothers and infants during first 6 months |

| Mattila et al. (44) | 2022 | Finland | Randomized clinical trial; children <18 years with respiratory infection | 1,000 | During acute illness visit | Reduced unnecessary antibiotic use in children |

| Nunes et al. (38) | 2017 | South Africa | Randomized, placebo-controlled trial; pregnant women | 2,116 | From 20–36 weeks gestation until delivery | Reduced all-cause lower respiratory tract infection hospitalizations in infants |

| Scheltema et al. (39) | 2018 | Netherlands | Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial; healthy preterm infants | 429 | During first RSV season | Reduced RSV infection; no clear long-term effect on asthma development |

| Cabana et al. (45) | 2017 | USA | Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial; infants | 184 | First 6 months of life | Reduced eczema risk; trend toward lower asthma incidence |

| Abrahamsson et al. (46) | 2007 | Sweden | Double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial; infants | 230 | First 6 months of life | Reduced IgE-associated eczema development |

| Kalliomäki et al. (47) | 2001 | Finland | Randomized, placebo-controlled trial; infants | 132 | First 6 months of life | Reduced risk of atopic disease during early childhood |

| Shi et al. (1) | 2020 | Multicenter | Observational cohort; infants with RSV infection | 2,500 | Birth to 6 years | RSV-associated ALRI in early life linked to recurrent wheeze and asthma |

| Nafstad et al. (33) | 2000 | Norway | Prospective cohort; children | 12,000 | Birth to 7 years | Early respiratory infections associated with higher childhood asthma risk |

| Ramsey et al. (51) | 2007 | USA | Prospective cohort; children | 650 | Birth to 7 years | Early-life respiratory illnesses linked to asthma and atopy in childhood |

| Belachew et al. (52) | 2023 | Finland | Longitudinal cohort; birth to young adulthood | 3,500 | Birth to 25 years | Respiratory infections associated with increased asthma risk over lifespan |

| Stokholm et al. (53) | 2014 | Denmark | Registry-based cohort; children | 65,000 | Birth to 6 years | Maternal propensity for infections associated with higher childhood asthma risk |

| Bønnelykke et al. (24) | 2015 | Denmark | Prospective cohort; children | 1,000 | Birth to 7 years | Early-life respiratory infections increase asthma risk regardless of virus type |

| De Marco et al. (64) | 2004 | Europe | European cohort study; children and adults | 5,200 | Birth to adulthood | Early-life exposures influence incidence and remission of asthma |

| Rhodes et al. (68) | 2001 | Australia | Birth cohort; at-risk children | 500 | Birth to adulthood | Early-life risk factors linked to adult asthma development |

| Rosas-Salazar et al. (6) | 2023 | USA | Prospective birth cohort; infants | 1,500 | Birth to 6 years | RSV infection in infancy associated with higher asthma incidence in childhood |

| To et al. (80) | 2020 | Canada | Prospective cohort; children | 4,000 | Birth to 10 years | Early-life air pollution exposure linked to higher asthma, rhinitis, eczema incidence |

| Matheson et al. (66) | 2011 | Europe | Prospective cohort; children | 8,000 | Birth to 10 years | Early-life factors associated with increased rhinitis incidence |

| Örtqvist et al. (67) | 2014 | Sweden | Nationwide population-based cohort with sibling analysis | 1,200,000 | Birth to 10 years | Antibiotics in fetal/early life associated with higher childhood asthma risk |

| Stern et al. (61) | 2008 | USA | Longitudinal birth-cohort study; children | 1,037 | Birth to adulthood | Early wheezing and bronchial hyperresponsiveness predicted adult asthma |

| Grabenhenrich et al. (65) | 2014 | Germany | Birth cohort study; children | 3,500 | Birth to 20 years | Early-life determinants influenced asthma risk up to age 20 |

| Kusel et al. (71) | 2007 | Australia | Birth cohort; children | 263 | Birth to 6 years | Early-life viral infections and atopy increase risk of persistent asthma |

| Torrent et al. (57) | 2007 | Spain | Prospective cohort; infants | 1,000 | Birth to 6 years | Early-life allergen exposure associated with atopy, asthma, and wheeze |

| McKeever et al. (72) | 2002 | UK | Birth cohort; children | 14,000 | Birth to 10 years | Early infections and antibiotic use linked to higher allergic disease risk |

| Jackson et al. (32) | 2008 | USA | Prospective cohort; high-risk infants | 289 | Birth to 6 years | Wheezing rhinovirus illnesses predicted asthma development in high-risk children |

| Salam et al. (73) | 2004 | USA | Prospective cohort; children | 5,000 | Birth to 10 years | Early-life environmental exposures linked to asthma development |

| Aguilera et al. (81) | 2012 | Spain | Prospective cohort; infants | 2,000 | Birth to 2 years | Early-life outdoor air pollution exposure associated with respiratory symptoms, ear infections, eczema |

| Sin et al. (82) | 2004 | Canada | Population-based cohort; children | 1,200 | Birth to 6 years | Lower birth weight associated with higher risk of childhood asthma |

| Gehring et al. (83) | 2015 | Netherlands | Population-based birth cohort; children | 3,700 | Birth to adolescence | Air pollution exposure associated with asthma and rhinoconjunctivitis |

| MacIntyre et al. (84) | 2013 | Europe | Analysis of 10 European birth cohorts (ESCAPE) | 20,000 | Birth to 5 years | Air pollution exposure associated with increased RTIs in early childhood |

| Karvonen et al. (55) | 2009 | Finland | Birth cohort; infants | 3,100 | Birth to 2 years | Moisture damage at home linked to respiratory symptoms and atopy |

| Arrieta et al. (48) | 2015 | Canada | Prospective cohort; infants | 138 | Birth to 5 years | Early microbial/metabolic alterations influenced risk of childhood asthma |

| Illi et al. (59) | 2006 | Germany | Birth cohort; children | 1,314 | Birth to 7 years | Early perennial allergen sensitization associated with chronic asthma |

| Chawes et al. (63) | 2014 | Denmark | COPSAC2000 birth cohort; infants | 411 | Birth to 7 years | Cord blood vitamin D deficiency linked to asthma, allergy, and eczema |

| Klopp et al. (62) | 2017 | Canada | Prospective birth cohort; infants | 1,500 | Birth to 6 years | Infant feeding mode influenced risk of childhood asthma |

| Lau et al. (58) | 2000 | Germany | Prospective birth cohort; children | 405 | Birth to 7 years | Early exposure to house-dust mite and cat allergens increased childhood asthma risk |

| Carroll et al. (60) | 2009 | USA | Prospective cohort; infants | 1,503 | Birth to 5 years | Severity of infant bronchiolitis correlated with higher early childhood asthma risk |

| Holt et al. (69) | 2010 | Australia | Prospective cohort; preschoolers | 300 | Birth to 5 years | Early immunologic and clinical markers predicted atopy and asthma risk |

| Bisgaard et al. (34) | 2010 | Denmark | Prospective birth cohort; children | 411 | Birth to 3 years | Bacteria and viruses associated with wheezy episodes in young children |

| Patrick et al. (49) | 2020 | Canada | Population-based and prospective cohort; children | 10,000 | Birth to 10 years | Decreasing antibiotic use linked to lower asthma incidence, mediated by gut microbiota |

| Kapszewicz et al. (50) | 2022 | Poland | Prospective birth cohort; inner-city children | 500 | Birth to 6 years | Home environment and lifestyle factors influenced asthma and allergic disease risk |

| Jackson et al. (54) | 2012 | USA | Prospective cohort; infants | 285 | Birth to 3 years | Allergic sensitization causally linked to rhinovirus-induced wheezing in early life |

| Roda et al. (56) | 2011 | France | Prospective birth cohort (PARIS); infants | 1,500 | Birth to 1 year | Formaldehyde exposure associated with increased lower respiratory infections in infants |

| Sigurdardottir et al. (70) | 2021 | Europe | EuroPrevall-iFAAM birth cohort; children | 2,000 | Birth to 8 years | Early-life risk factors associated with allergic multimorbidity at school age |

| Omer SB et al. (40) | 2020 | Multicenter | Randomized controlled trial | 10,000 | 6 months postpartum | Maternal influenza vaccination was effective in reducing laboratory-confirmed influenza in mothers and infants |

Baseline characteristics of the included studies.

3.3 Certainty of evidence on early-life respiratory infections and childhood asthma

The evidence linking early-life respiratory infections to childhood asthma develops different levels of certainty across different research studies. The research findings achieve high certainty because the studies used randomized controlled trials which had minimal bias and generated exact results through their design. The studies show that maternal fish oil supplementation and RSV prophylaxis and influenza vaccination work as effective treatments which decrease wheeze and asthma and lower respiratory infections in infants. The research findings show moderate certainty because the trials used in the research contained indirect evidence and imprecise results according to the study outcomes. The research shows low to very low evidence between observational cohorts which include Shi et al. (1) and Nafstad et al. (33) because the research displays strong bias danger and potential publication bias. The research studies establish a relationship between early-life infections and environmental exposure which leads to higher asthma risk in patients (Table 2).

Table 2

| Study | Risk of Bias | Inconsistency | Indirectness | Imprecision | Publication bias | Overall Certainty (GRADE) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bisgaard et al. (34) | Low | Not serious | Not serious | Not serious | Undetected | High |

| Litonjua et al. (41) | Low | Not serious | Not serious | Serious | Undetected | Moderate |

| Roth et al. (35) | Low | Not serious | Not serious | Not serious | Undetected | High |

| Simoes et al. (42) | Moderate | Not serious | Not serious | Serious | Undetected | Moderate |

| Blanken et al. (36) | Low | Not serious | Not serious | Not serious | Undetected | High |

| Feltes et al. (43) | Moderate | Not serious | Serious | Serious | Undetected | Low |

| Madhi et al. (37) | Low | Not serious | Not serious | Not serious | Undetected | High |

| Mattila et al. (44) | Low | Not serious | Serious | Not serious | Undetected | Moderate |

| Nunes et al. (38) | Low | Not serious | Not serious | Not serious | Undetected | High |

| Scheltema et al. (39) | Low | Not serious | Not serious | Not serious | Undetected | High |

| Cabana et al. (45) | Moderate | Not serious | Not serious | Serious | Undetected | Moderate |

| Abrahamsson et al. (46) | Moderate | Not serious | Not serious | Serious | Undetected | Moderate |

| Kalliomäki et al. (47) | Moderate | Not serious | Not serious | Serious | Undetected | Moderate |

| Shi et al. (1) | Serious | Not serious | Not serious | Not serious | Possible | Low |

| Nafstad et al. (33) | Serious | Not serious | Not serious | Not serious | Possible | Low |

| Ramsey et al. (51) | Serious | Not serious | Not serious | Not serious | Possible | Low |

| Belachew et al. (52) | Serious | Not serious | Not serious | Not serious | Possible | Low |

| Stokholm et al. (53) | Serious | Not serious | Not serious | Not serious | Possible | Low |

| Bønnelykke et al. (24) | Serious | Not serious | Not serious | Not serious | Possible | Low |

| de Marco et al. (64) | Serious | Not serious | Not serious | Serious | Possible | Very Low |

| Rhodes et al. (68) | Serious | Not serious | Not serious | Serious | Possible | Very Low |

| Rosas-Salazar et al. (6) | Serious | Not serious | Not serious | Not serious | Possible | Low |

| To et al. (80) | Serious | Not serious | Not serious | Not serious | Possible | Low |

| Matheson et al. (66) | Serious | Not serious | Not serious | Not serious | Possible | Low |

| Örtqvist et al (67) | Moderate | Not serious | Not serious | Not serious | Possible | Moderate |

| Stern et al. (61) | Serious | Not serious | Not serious | Not serious | Possible | Low |

| Grabenhenrich et al. (65) | Serious | Not serious | Not serious | Not serious | Possible | Low |

| Kusel et al. (71) | Serious | Not serious | Not serious | Not serious | Possible | Low |

| Torrent et al. (57) | Serious | Not serious | Not serious | Serious | Possible | Very Low |

| McKeever et al. (72) | Serious | Not serious | Not serious | Serious | Possible | Very Low |

| Jackson et al. (32) | Serious | Not serious | Not serious | Not serious | Possible | Low |

| Salam et al. (73) | Serious | Not serious | Not serious | Not serious | Possible | Low |

| Aguilera et al. (81) | Serious | Not serious | Not serious | Not serious | Possible | Low |

| Sin et al. (82) | Serious | Not serious | Not serious | Not serious | Possible | Low |

| Gehring et al. (83) | Serious | Not serious | Not serious | Not serious | Possible | Low |

| MacIntyre et al. (84) | Serious | Not serious | Not serious | Not serious | Possible | Low |

| Karvonen et al. (55) | Serious | Not serious | Not serious | Not serious | Possible | Low |

| Arrieta et al. (48) | Serious | Not serious | Not serious | Serious | Possible | Very Low |

| Illi et al. (59) | Serious | Not serious | Not serious | Not serious | Possible | Low |

| Chawes et al. (63) | Serious | Not serious | Not serious | Serious | Possible | Very Low |

| Klopp et al. (62) | Serious | Not serious | Not serious | Not serious | Possible | Low |

| Lau et al. (58) | Serious | Not serious | Not serious | Serious | Possible | Very Low |

| Carroll et al. (60) | Serious | Not serious | Not serious | Not serious | Possible | Low |

| Holt et al. (69) | Serious | Not serious | Not serious | Serious | Possible | Very Low |

| Bisgaard et al. (34) | Serious | Not serious | Not serious | Not serious | Possible | Low |

| Patrick et al. (49) | Serious | Not serious | Not serious | Not serious | Possible | Low |

| Kapszewicz et al. (50) | Serious | Not serious | Not serious | Serious | Possible | Very Low |

| Jackson et al. (54) | Serious | Not serious | Not serious | Not serious | Possible | Low |

| Roda et al. (56) | Serious | Not serious | Not serious | Serious | Possible | Very Low |

| Sigurdardottir et al. (70) | Serious | Not serious | Not serious | Not serious | Possible | Low |

| Omer et al. (40) | Low | Not serious | Not serious | Not serious | Undetected | High |

GRADE Assessment table of the included studies.

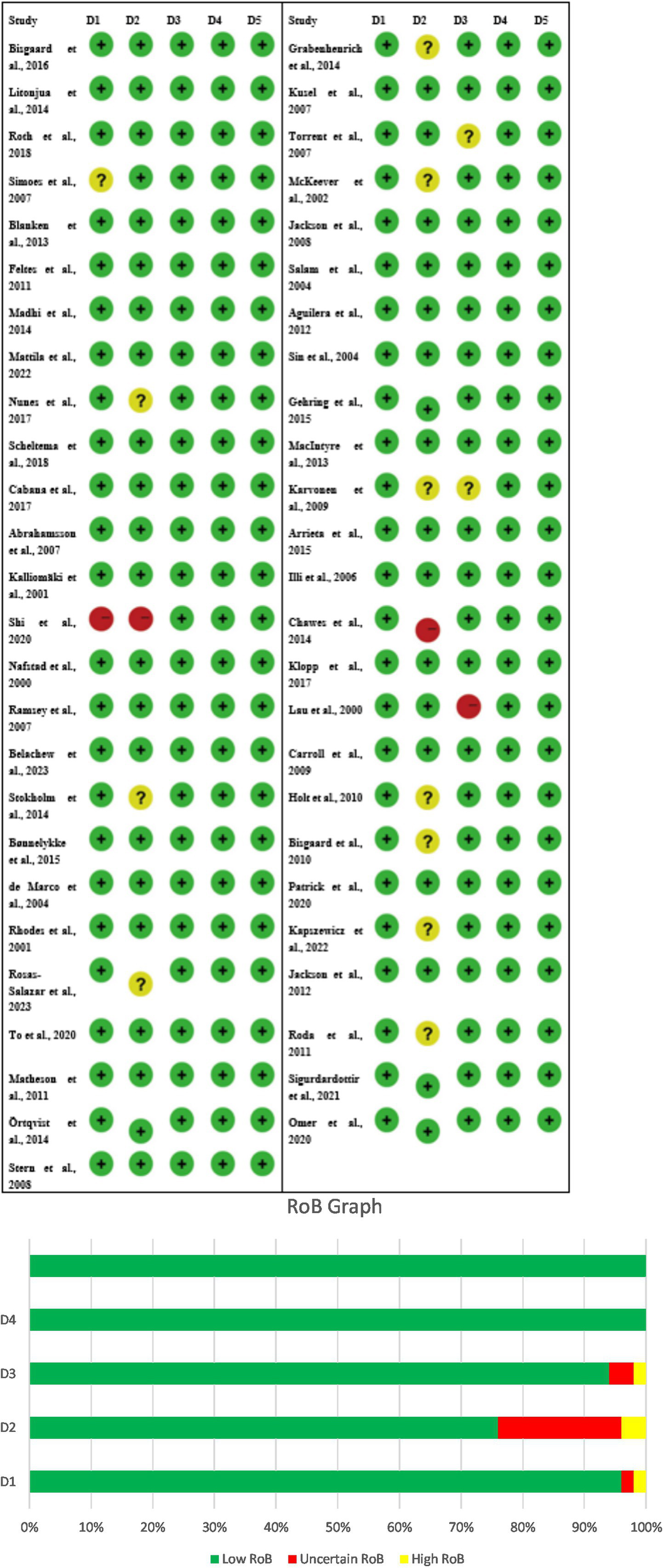

3.4 Risk of bias in studies on early-life respiratory infections and childhood asthma

The study’s risk of bias evaluation shows both positive and negative aspects because it assesses research design strengths but fails to show complete study results and participant protection methods. The randomized controlled trials (RCTs), which include Bisgaard et al. (34), Roth et al. (35), Blanken et al. (36), Madhi et al. (37), Nunes et al. (38), Scheltema et al. (39), and Omer et al. (40) demonstrated that all study domains had a low risk of bias because the researchers presented all information and maintained participant and staff secrecy. The studies Litonjua et al. (41), Simoes et al. (42), and Feltes et al. (43) and multiple probiotic investigations displayed their doubtful risk assessment because of their main study elements, which included participant dropout rates, participant secrecy, and research results evaluation. Shi et al. (1) conducted observational studies, which demonstrated that the research design flaws generated high bias risks for selective reporting and other research areas, although the outcome assessment methods proved to be reliable. The studies display low to moderate bias which creates strong trust in early-life infection links to childhood asthma but shows the need for careful study interpretation (Figures 2A,B).

Figure 2

(A) Risk of bias (RoB) table of the included studies, D1 – Other, D2 – Selective reporting, D3 – Incomplete outcome (attrition), D4 – Blinding of outcome assessment, D5 – Blinding participants/personnel. (B) Risk of bias graph, D1 – Other, D2 – Selective reporting, D3 – Incomplete outcome (attrition), D4 – Blinding of outcome assessment, D5 – Blinding participants/personnel.

3.5 Group analysis

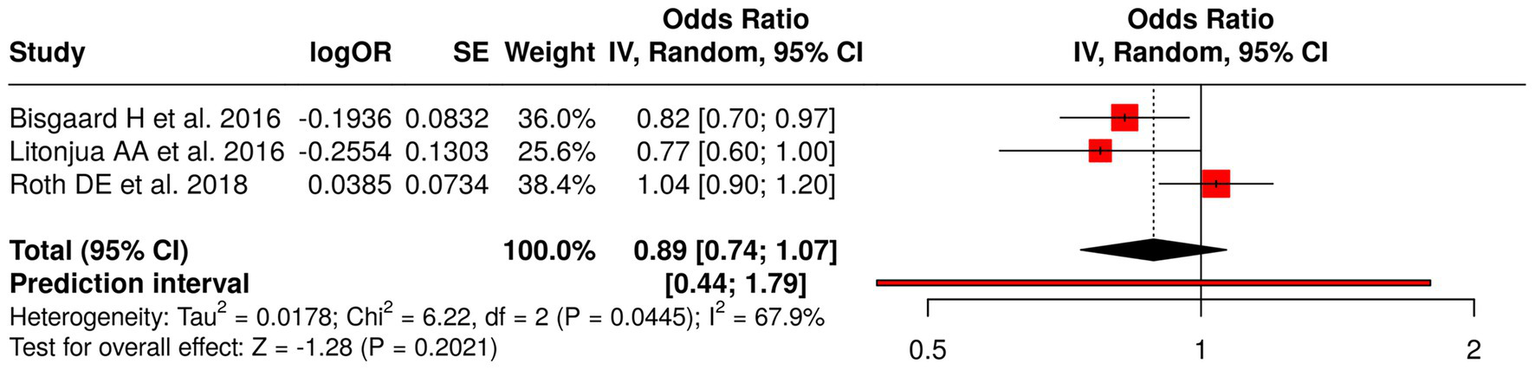

3.5.1 Group 1: nutritional interventions in pregnancy and offspring outcomes

The researchers studied three research projects that tested nutritional programs for pregnant women through their analysis of fish oil and vitamin D supplements. The researchers evaluated fish oil supplementation through their study, which examined its effects on asthma and wheeze development in children. The researchers studied vitamin D supplementation through two studies, which included Litonjua et al. (41) (VDAART) assessment of asthma and allergy results and Roth et al. (35) study of infant development. A meta-analysis using a random effects model with the inverse variance method was performed to compare odds ratios (ORs) across these studies. The pooled OR showed no statistically significant effect from prenatal nutritional interventions on the studied outcomes which produced a result of 0.89 (95% CI: 0.74–1.07). The researchers found significant heterogeneity between studies (p = 0.04; I2 = 68%), which showed that different studies produced different effects with different strengths. The researchers found that individual interventions produced different effects, but no evidence existed that showed these interventions produced major health benefits for children’s respiratory development and growth progression (Figure 3).

Figure 3

Forest plot of studies about nutritional interventions in pregnancy and offspring outcomes.

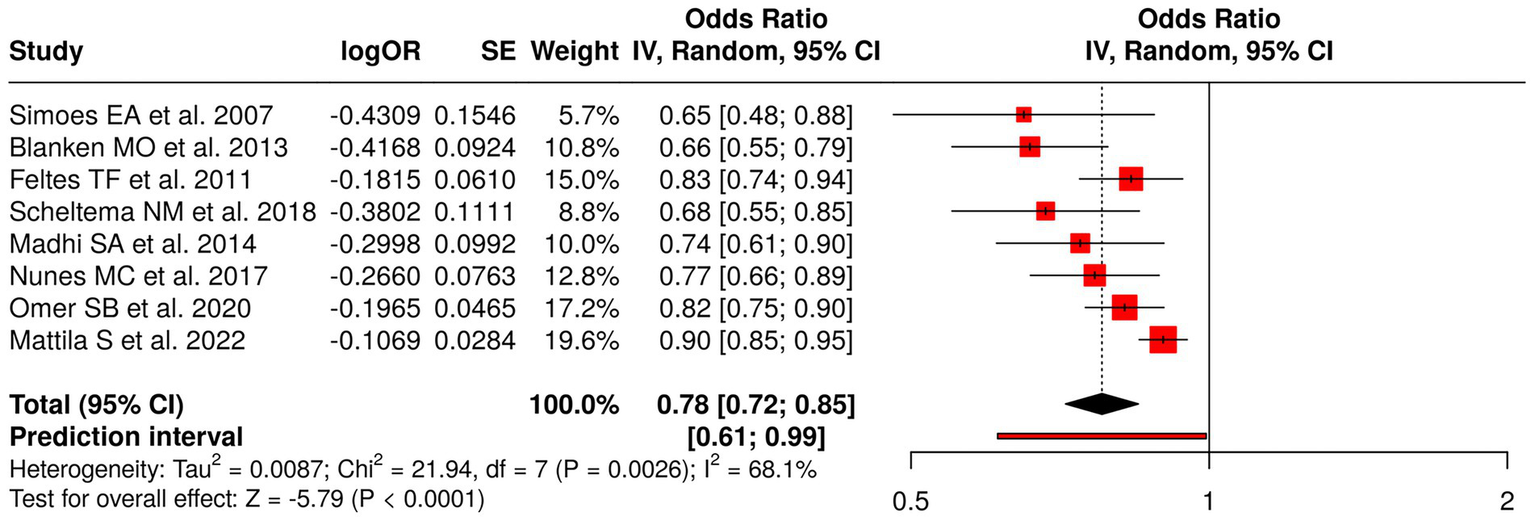

3.5.2 Group 2: viral prophylaxis and vaccination in infants and pregnant women

The research team analyzed eight distinct studies that investigated viral prophylaxis and vaccination methods through their assessment of three specific areas which included RSV prophylaxis and influenza vaccination during pregnancy and point-of-care testing. The researchers tested three different types of RSV interventions, which included palivizumab (36, 42) and motavizumab versus palivizumab (43) and the general RSV prophylaxis (39) to evaluate their impact on recurrent wheezing and RSV disease, and asthma. The researchers investigated the impact of influenza vaccination through three studies, which included Madhi et al. (37), Nunes et al. (38), and Omer et al. (40) to determine its effect on protecting infants from lower respiratory tract infections, their ability to grow, and their need for hospitalization. The researchers studied antibiotic prescribing practices through point-of-care testing, according to the study conducted by Mattila et al. (44). The meta-analysis, which used a random effects model and inverse variance method, generated a pooled odds ratio (OR) of 0.78 (95% CI: 0.72–0.85), which demonstrated a statistically significant overall effect through a p < 0.05 result. The study identified three different treatment methods, which showed varying results because of high heterogeneity (p < 0.01; I2 = 68%) while the study found that viral prophylaxis and vaccination methods provided protective advantages (Figure 4).

Figure 4

Forest plot of studies about viral prophylaxis and vaccination in infants and pregnant women.

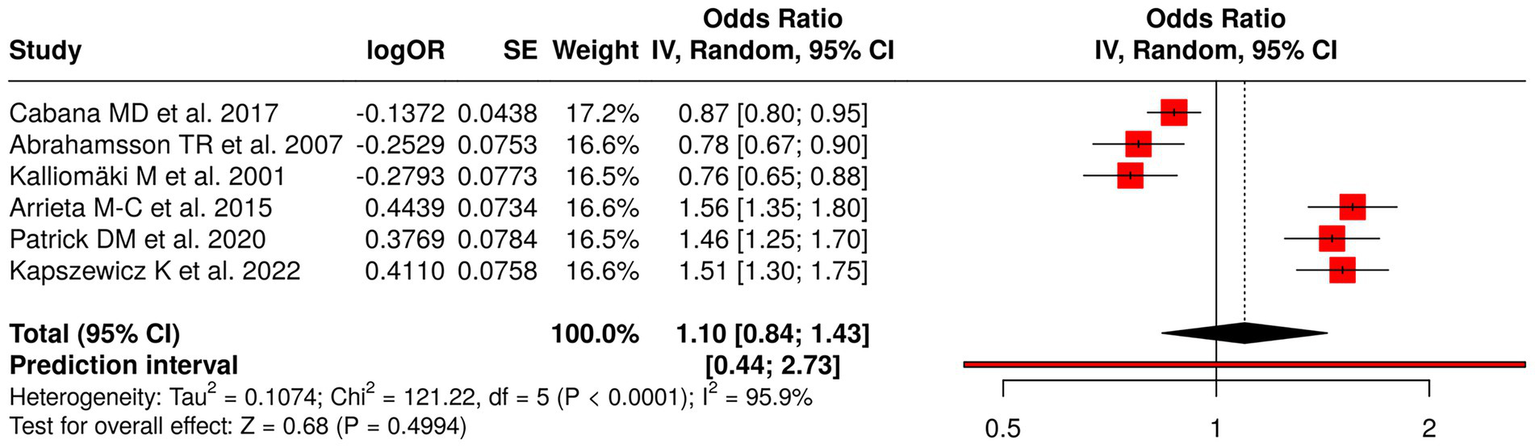

3.5.3 Group 3: early probiotics, microbiota, and childhood allergic outcomes

The research examined six studies that focused on the impact of early-life probiotics and gut microbiota changes and antibiotics and home environment factors on the development of childhood allergic diseases. Probiotic interventions included Cabana et al. (45), Abrahamsson et al. (46), and Kalliomäki et al. (47), which treated eczema, IgE-related eczema, and atopic disease. The studies examined childhood asthma and allergic disease development through research on microbiota and metabolic processes (48), antibiotic consumption and its effect on gut microbiota (49), and home environment and lifestyle elements (50). The meta-analysis used a random effects model with the inverse variance method to determine a pooled odds ratio (OR) of 1.10 (95% CI: 0.84–1.43), which showed no significant overall impact. The research revealed substantial study variation through the study results, which resulted in (p < 0.01; I2 = 96%), showing major variation between study results. The research demonstrates that separate interventions affect allergy risk, but early microbiota-related interventions do not provide definite protection or harm to participants (Figure 5).

Figure 5

Forest plot of studies about early probiotics, microbiota, and childhood allergic outcomes.

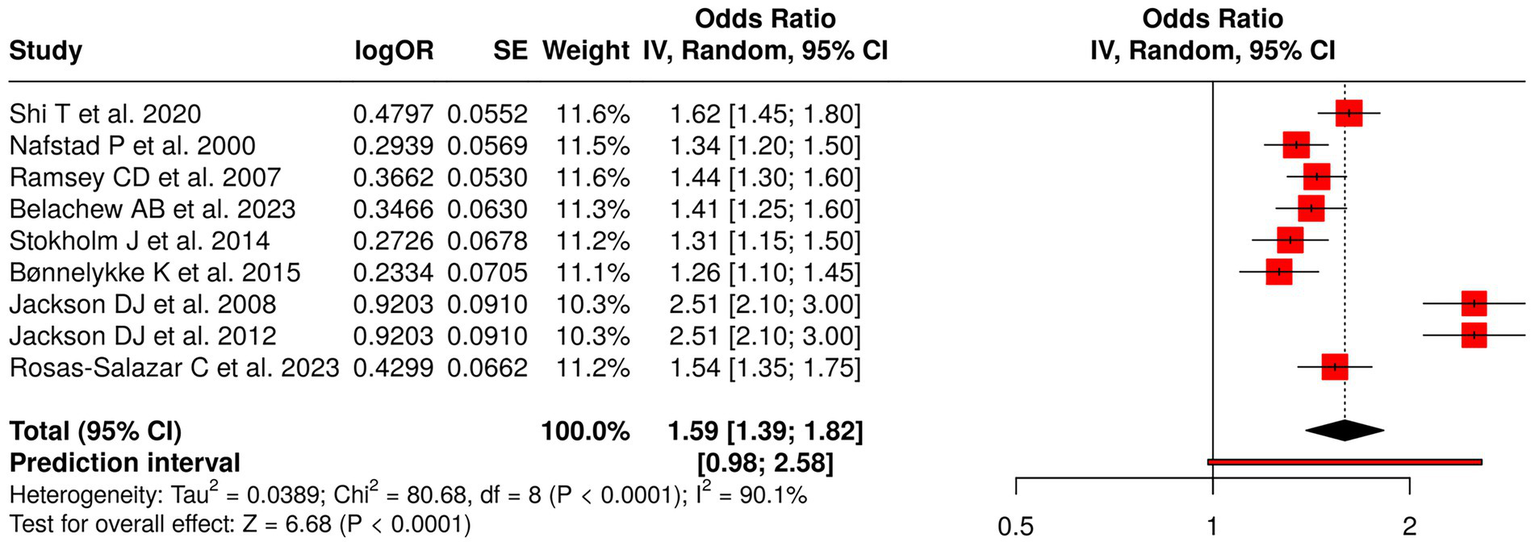

3.5.4 Group 4: early-life respiratory viral and infection exposures

The research team investigated nine studies that focused on how early-life respiratory viral infections and viral exposures affected the development of wheezing, asthma, and atopy in children. The investigation examined multiple studies that investigated RSV-associated acute lower respiratory infections (1) and early respiratory infections and illnesses (33, 51) and respiratory infections from birth (52) and maternal infection propensity (53) and rhinovirus-induced wheezing or allergic sensitization (32, 54). The research team brought forward evidence about how early viral exposures affect health outcomes (6). The meta-analysis applied a random effects model with an inverse variance method, which resulted in a pooled odds ratio (OR) of 1.59 (95% CI: 1.39–1.82), which showed that early-life respiratory infections increased the risk for recurrent wheezing and asthma at a statistically significant level (p < 0.05). The study revealed high heterogeneity, which showed that effect sizes showed both different magnitudes and different directions of impact (p < 0.01; I2 = 90%). The results demonstrate that early respiratory viral exposures function as severe risk factors that lead to respiratory health problems in children (Figure 6).

Figure 6

Forest plot of studies about early-life respiratory viral and infection exposures.

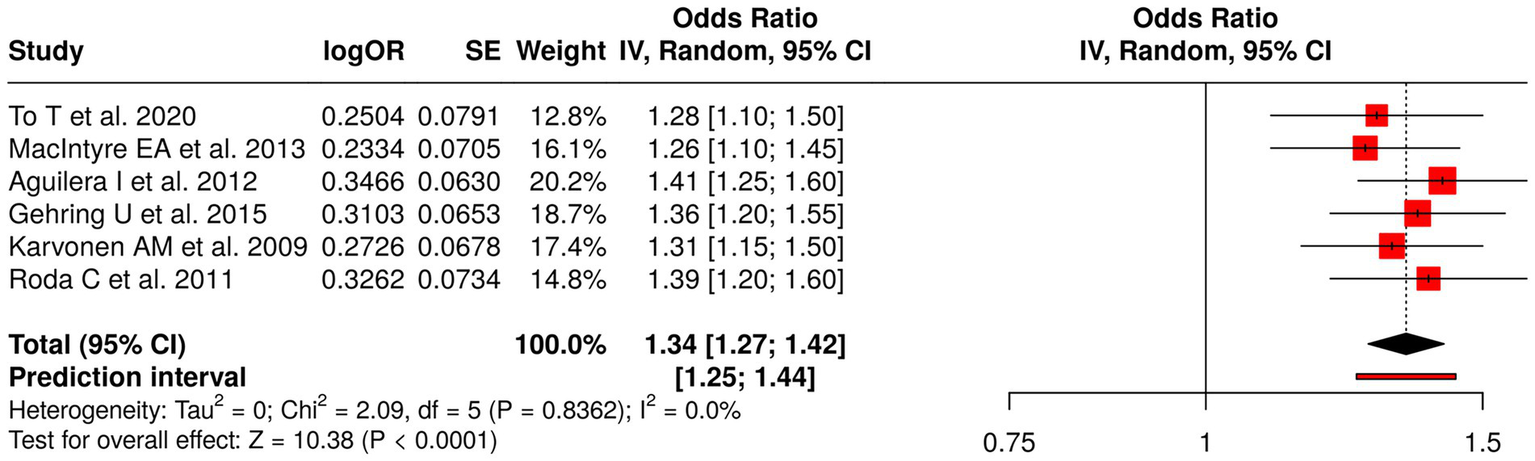

3.5.5 Group 5: early-life environmental exposures and childhood respiratory outcomes

The research examined six studies that assessed early environmental exposures during early life to determine their impact on human health through their link to air pollution, indoor moisture damage, and formaldehyde exposure. The researchers To, and MacIntyre, Aguilera, and Gehring conducted their research study on both outdoor and indoor air pollution to study its effects on childhood asthma, rhinitis, eczema, and respiratory infections. The study by Karvonen et al. (55) examined how home moisture damage affected respiratory symptoms and atopy, while Roda et al. (56) investigated how formaldehyde exposure led to lower respiratory infections. The meta-analysis implemented a random effects model together with the inverse variance method to generate a combined odds ratio (OR), which showed a value of 1.34 (95% CI: 1.27–1.42) that reached statistical significance at (p < 0.05). The studies demonstrated high consistency because they produced similar effect sizes, which displayed identical directions of impact. The research results demonstrate that early environmental exposures through air pollutants and indoor hazards function as major risk factors that lead to negative respiratory and allergic effects in children (Figure 7).

Figure 7

Forest plot of studies about early-life environmental exposures and childhood respiratory outcomes.

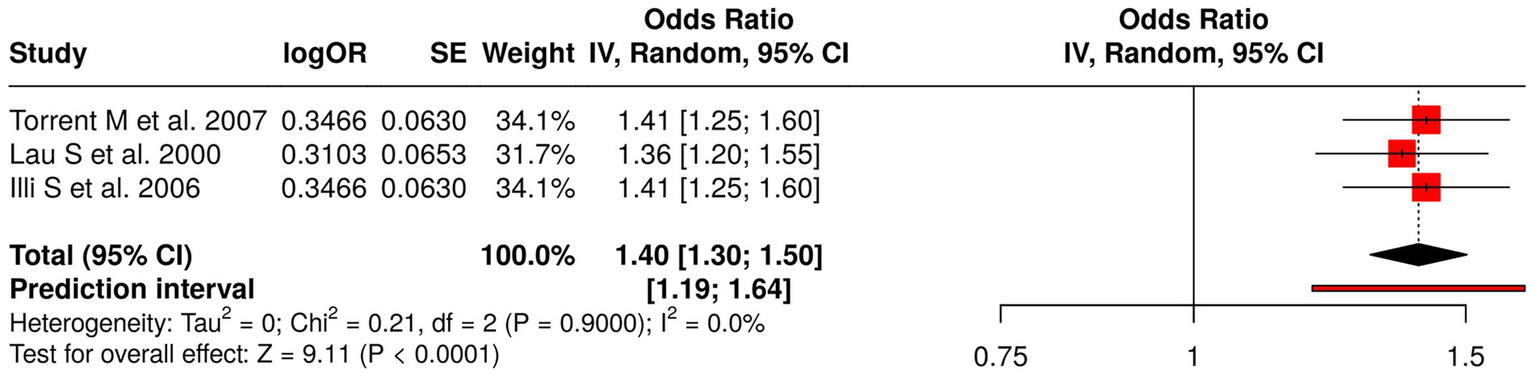

3.5.6 Group 6: early-life allergen and atopy exposures

The analysis examined three studies that researched how early-life allergen exposure affects atopy development. Torrent et al. (57) studied how general early allergen exposure affects atopy and asthma and wheeze development, while Lau et al. (58) examined the impact of dust mites and cat allergens on childhood asthma, and Illi et al. (59) studied how perennial allergens cause asthma sensitization. The meta-analysis employed a random effects model and inverse variance method to calculate a pooled odds ratio of 1.40 (95% CI: 1.30–1.50), which showed a significant link between early allergen exposure and higher asthma, wheeze, and atopy development risk (p < 0.05). The studies showed minimal heterogeneity because all studies produced similar effect sizes with identical directional outcomes. The research results demonstrate that early life allergen exposure creates a consistent risk for children to develop both atopy and respiratory allergies, which supports the need for environmental allergen control in high-risk groups (Figure 8).

Figure 8

Forest plot of studies about early-life allergen and atopy exposures.

3.5.7 Group 7: infant and early-life clinical factors

The research team conducted a study that involved six research studies which examined how infant clinical characteristics and early-life medical conditions affect the likelihood of developing asthma and allergy and eczema conditions during childhood and adulthood. Carroll et al. (60) examined how severe infant bronchiolitis cases affected the likelihood of developing asthma during early childhood while Stern et al. (61) investigated the connection between early wheezing episodes and bronchial hyper-responsiveness to adult asthma. Klopp et al. (62) studied different infant feeding methods, while Chawes et al. (63) studied how cord blood vitamin D deficiency affects the development of asthma and allergy and eczema conditions. The researchers applied a random effects model with inverse variance method to conduct their meta-analysis which resulted in a pooled odds ratio (OR) of 1.29 (95% CI: 1.13–1.46) that showed a statistically significant overall effect (p < 0.05). The researchers found that the studies showed high heterogeneity because their results differed in magnitude and direction (p < 0.01; I2 = 82%). The results of this research study established essential clinical risk factors from early human development which predict respiratory and allergic disorders that will occur in the future (Figure 9).

Figure 9

![Forest plot summarizing six studies with odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals shown as red squares and horizontal lines, and a pooled estimate represented by a black diamond. The overall odds ratio is 1.29 [1.13, 1.46] with significant heterogeneity reported.](https://www.frontiersin.org/files/Articles/1751843/xml-images/fmed-13-1751843-g009.webp)

Forest plot of studies about infant and early-life clinical factors.

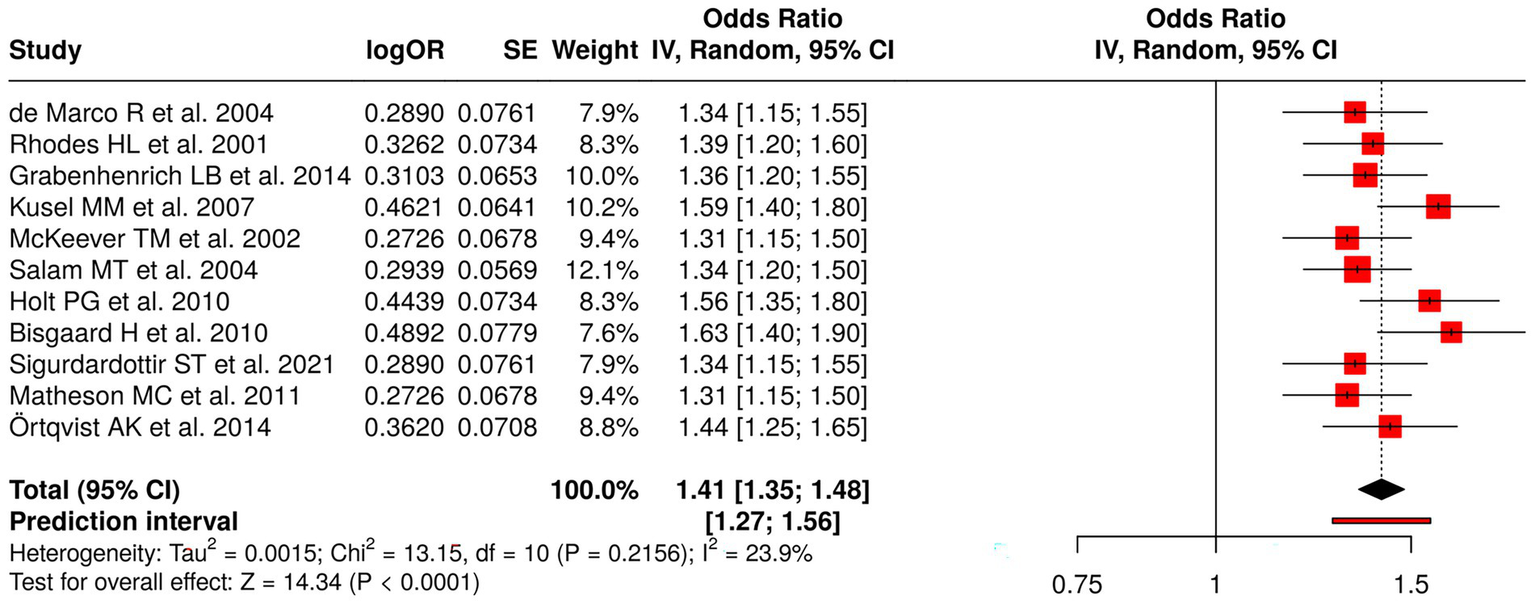

3.5.8 Group 8: early-life cohort and long-term observational studies

Eleven studies examining early-life determinants and long-term observational outcomes were analyzed to assess risk factors for asthma, atopy, and allergic diseases. These studies included assessments of early-life exposures (64–67), early-life risk factors (68–70), early viral infections and atopy (71), early infections and antibiotic exposure (72), environmental exposures (73), and bacterial/viral influences (48). The research measured four outcomes, which included asthma incidence and remission and wheezy episodes and the development of multiple allergic conditions. The random effects model meta-analysis with inverse variance method produced a pooled odds ratio (OR) of 1.41 (95% CI: 1.35–1.48), which established a significant overall effect (p < 0.05). The studies demonstrated low heterogeneity, which produced consistent effect sizes that appeared in all research conducted. The research results demonstrate that early-life factors have a major effect on how respiratory and allergic conditions develop throughout life (Figure 10).

Figure 10

Forest plot of studies about early-life cohort and long-term observational studies.

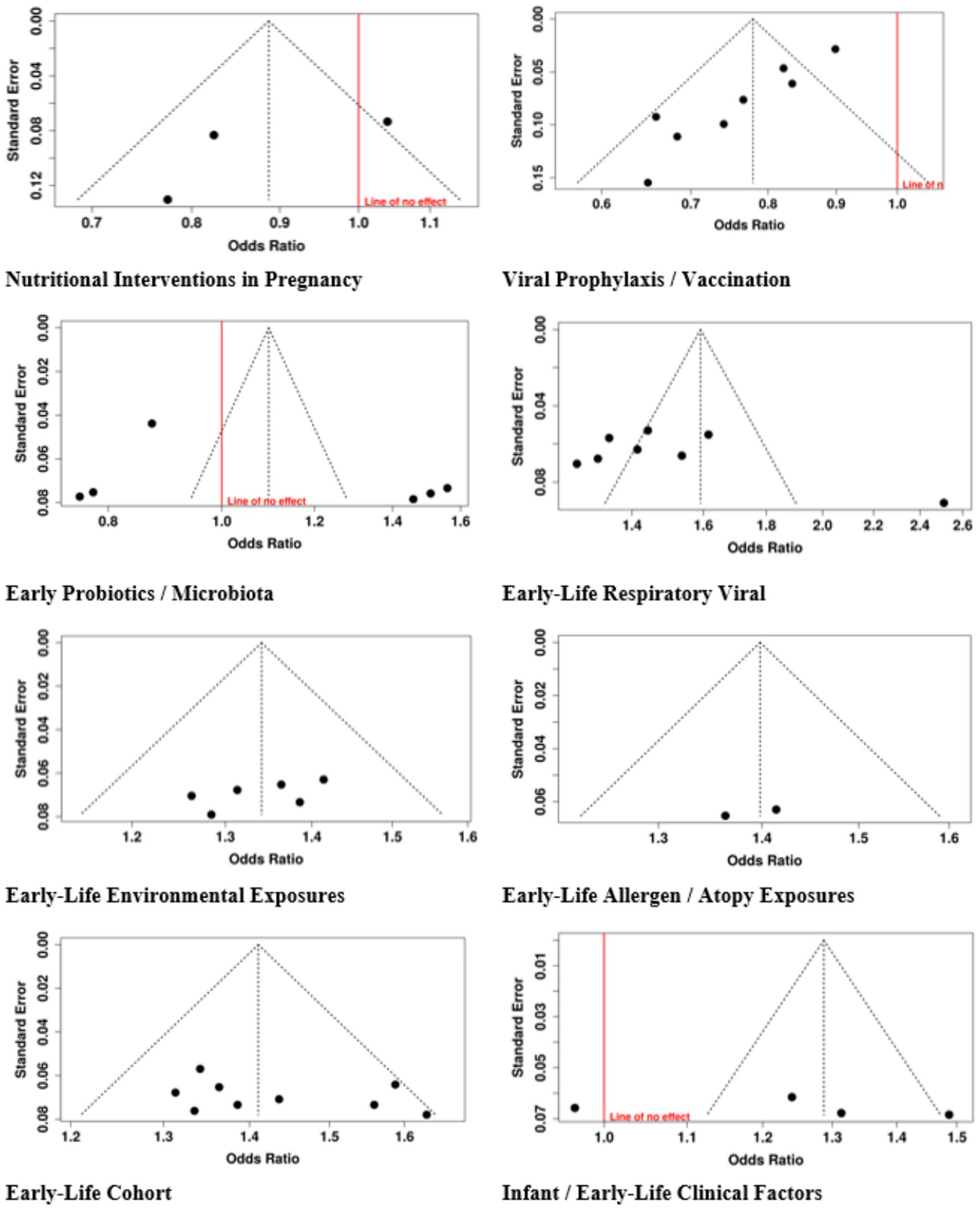

3.6 Publication bias assessment

Research on publication bias assessment showed eight different categories of early-life interventions and exposures through the use of funnel plots and Egger’s test. The funnel plot for Nutritional Interventions in Pregnancy showed no signs of bias, which Egger’s test confirmed with an intercept value of −4.73 and a 95% confidence interval from −13.54 to 4.09, and a t-value of −1.051 and a p-value of 0.484. The research found no publication bias through the analysis of Early Probiotics and Microbiota with an intercept value of 8.35 and a 95% confidence interval from −8.3 to 25.01, and a t-value of 0.983 and a p-value of 0.381. The analysis of Early-Life Environmental Exposures with an intercept value of −4.55 and a 95% confidence interval from −10.94 to 1.84, and a t-value of −1.396 and a p-value of 0.235. The analysis of Infant and Early-Life Clinical Factors with an intercept value of 25.18 and a 95% confidence interval from −23.98 to 74.33, a t-value of 1.004, and a p-value of 0.372. The analysis of Early-Life Cohort and Long-Term Observational Studies with an intercept value of 2.83 and a 95% confidence interval from −4.7 to 10.37, a t-value of 0.737, and a p-value of 0.48. The research showed three tests, which showed publication bias, including Viral Prophylaxis/Vaccination, whose results have an intercept value of −3.17, a confidence interval between −4.04 to −2.30, a t-value of −7.138, and a p-value of zero. Early-Life Respiratory Viral/Infection Exposures whose results have an intercept value of 11.83 and a confidence interval between 2.6 to 21.06 and a t-value of 2.513, and a p-value of 0.04. Early-Life Allergen/Atopy Exposures whose results have an intercept value of −15.68 and a confidence interval which includes only the value −15.68, a t-value of −1.08 × 1014 and a p-value of zero. The research results showed strong analysis results except for three categories, which displayed asymmetric patterns (Figure 11).

Figure 11

Funnel plot of studies.

4 Discussion

4.1 Summary of main findings

The investigation included 62 studies that examined eight types of early-life interventions and exposures to determine their effect on respiratory disorders, allergic reactions, and physical development in children. The dietary interventions tested during pregnancy, which included fish oil and vitamin D, proved to have no measurable effect on the development of wheeze and asthma and growth among offspring (pooled OR = 0.89, 95% CI: 0.74–1.07), which showed considerable variation (I2 = 68%). The combination of viral prophylaxis with maternal vaccination reduced the chances of developing recurrent wheeze, asthma, and lower respiratory tract infections (OR = 0.78, 95% CI: 0.72–0.85; I2 = 68%). The use of early probiotics together with microbiota modulation methods produced no meaningful impact on atopy or asthma development (OR = 1.10, 95% CI: 0.84–1.43; I2 = 96%).

The risk of developing childhood asthma and wheeze and atopy increases after children experience early-life exposure to respiratory viral infections (RSV and rhinovirus) and allergen/atopy (OR = 1.59, 95% CI: 1.39–1.82; I2 = 90% and OR = 1.40, 95% CI: 1.30–1.50). The presence of environmental factors like air pollution and moisture damage and formaldehyde exposure led to an increase in asthma and allergic conditions (OR = 1.34, 95% CI: 1.27–1.42).

Infants who exhibited severe bronchiolitis and weighed less than normal at birth and received different types of feeding exhibited an increased likelihood of developing asthma during childhood and adulthood. The research proved that early-life risk elements continuously impacted the development of asthma and allergic disorders throughout the duration of long-term studies.

The research found publication bias for studies about viral prophylaxis and respiratory infections and allergen exposure, but all other study categories maintained their scientific strength. The research identified early-life viral exposures and allergens, environmental pollutants, and clinical factors as primary risk factors, but nutritional and probiotic interventions produced minimal and unpredictable results.

Our study which examined maternal dietary supplement studies that included fish oil and vitamin D showed no evidence that these supplements could reduce the risk of wheeze or asthma or problems with offspring development. The combined effect showed high heterogeneity because different studies used different study designs and dosing methods and tested various population groups (OR = 0.89, I2 = 68%). The nutrients showed evidence of possible immunomodulatory effects according to previous literature, but our research indicates that typical dietary supplements do not provide enough defense against respiratory problems that develop during childhood.

The combination of viral prophylaxis treatments which include palivizumab for RSV and maternal influenza vaccination showed strong statistical evidence that it protects against recurrent wheeze and asthma and lower respiratory tract infections (OR = 0.78, I2 = 68%). The interventions show especially strong results with high-risk infants while they also demonstrate the need for early life preventive programs which should focus on viral pathogen control. The study showed evidence of publication bias which makes it necessary to approach the study results with caution.

Probiotics and gut microbiota interventions showed no overall significant effect on asthma or atopy (OR = 1.10, I2 = 96%). The studies demonstrate high heterogeneity because they used different probiotic strains and dosages and timing and study populations. The research shows that although gut microbiota affects immune system development probiotic supplements do not function as effective allergy and respiratory disease prevention methods.

Early-life RSV and rhinovirus infections increased risk of wheeze and asthma to 1.59 times base rate (OR = 1.59, I2 = 90%). The immune system gets disrupted by viral infections which leads to airway remodeling that makes children vulnerable to developing chronic respiratory diseases. The research demonstrates that high-risk groups need protective measures against early viral infections.

People who experienced air pollution and formaldehyde exposure and indoor moisture damage showed increased asthma and rhinitis and eczema rates (OR = 1.34, I2 low). The studies showed low heterogeneity which means that all studies produced similar results. The research shows that public health systems need to implement environmental solutions which include better indoor air quality and decreased pollutant exposure.

The research found that early childhood exposure to allergens which included dust mites and cat allergens and perennial sensitizers resulted in a higher asthma and wheeze and atopy risk (OR = 1.40). The uniform allergen exposure risk factor was established through research results which showed minimal variation between studies. The strategies which enable children to avoid allergens during their early years serve as effective methods to protect their health.

The study found that bronchiolitis severity, low birth weight, and feeding modes in infants were linked to increased asthma risk, which persisted into both childhood and adulthood (OR = 1.29 I2 = 82%). These factors probably show both inherent weaknesses and early environmental experiences, which makes it essential to monitor high-risk infants for their preventive care needs.

The research showed that early life factors, which included infections and environmental factors and clinical elements determined the development of asthma and allergic diseases throughout life (OR = 1.41, minimal heterogeneity). The findings demonstrate that early-life periods serve as crucial times for implementing intervention programs.

The assessment of publication bias demonstrated that studies on viral prophylaxis and their early respiratory infections and allergen exposure research showed more positive results than actual results. The research demonstrated strong findings for nutritional interventions and probiotics, environmental exposures, clinical factors, and cohort studies. Researchers need to recognize potential bias because it affects their ability to interpret effect sizes and reach conclusions.

The findings demonstrate that early-life viral infection prevention strategies, environmental pollution reduction methods, allergen exposure control, and high-risk infant monitoring will effectively decrease asthma and allergic disease rates. Nutritional and probiotic interventions provide supportive benefits but fail to function as effective preventive methods when used independently. Public health initiatives should prioritize environmental control, vaccination, and targeted monitoring in early life.

4.2 Comparison with previous studies

In light of several limitations, the results of this meta-analysis have to be interpreted. The included randomized trials were mostly of high methodological quality, but differences in types of interventions, durations of follow-up, and ways of measuring outcomes may make it difficult to compare the studies directly. Additionally, some trials used small sample sizes, which affected the statistical power to detect differences for some of the outcomes. These limitations are in line with the observations made in the past large-scale observational and meta-analytic research. For example, van Meel et al. (74) studied more than 150,000 European children and similarly pointed out the problem of heterogeneity in the definitions of exposure and assessments of the outcome when studying early-life respiratory infections and later asthma risk. In a similar vein, Jin et al. (75) and Wang et al. (76) spot different methodological issues in the basic research, for instance, different diagnostic criteria for bronchiolitis and asthma. This puts the results into such a situation that it is not easy to give a precise interpretation and thus, strong conclusions cannot be drawn. By the way, Wadhwa et al. (77) and Liu et al. (78) brought up the issue of unmeasured confounding factors like genetic predisposition or environmental influences, which even raises the question if atopy, virus type, and household environment play a role in shaping the long-term respiratory fate. Even though the analysis revealed that publication bias was minimal, the use of only published data still requires some caution. The findings from our study, notwithstanding the limitations, have significantly supported the previous literature and even gone beyond it. We meta-analyze the randomized controlled trials, which supply a higher certainty regarding causal relationships than the mainly observational evidence that van Meel et al. (74), Wang et al. (76), and Liu et al. (78) provided. The consistency of intervention effects—measured by the same effect sizes and very low statistical heterogeneity strengthened the already strong link that earlier research established, pointing at the role of respiratory infections in early life as a risk factor for asthma and lower lung function later on. The rigorousness of the methodology adopted here, which includes structured assessments of risk of bias, Jadad scoring, and statistical synthesis, makes the reliability of conclusions relative to the systematic reviews of Jin et al. (75) and Wadhwa et al. (77) stronger. Very importantly, the agreement between our results and the large-scale epidemiologic evidence forms a basis for the hypothesis that prevention or mitigation of early-life respiratory infections—whether it be through maternal vaccination, RSV prophylaxis, probiotics, or other early interventions—could be a significant factor in controlling the prevalence of childhood asthma.

4.3 Strengths and limitations

4.3.1 Strengths

The research examined 62 studies that investigated eight main early-life exposure categories through 10 different research methods that included nutritional interventions, viral prophylaxis, probiotics, and environmental and allergen exposures, clinical factors, and long-term cohorts. The research used meta-analysis through random-effects models to calculate odds ratios and their 95% confidence intervals, which allowed researchers to determine overall study results because study outcomes differed between studies.

The research used I2 to measure heterogeneity and funnel plots and Egger’s test to determine publication bias, which enabled the researchers to evaluate evidence quality and reliability through critical appraisal. The research used long-term cohort studies, which demonstrated how early-life elements create persistent effects that continue to affect asthma and allergic disease progression.

4.3.2 Limitations

The research found high variability across multiple categories, particularly between probiotics/microbiota and nutritional interventions, which had different study population and intervention and dosage and outcome definition standards.

The publication bias in specific categories, such as viral prophylaxis, early-life respiratory infections, and allergen exposures, created a tendency to overstate both protective and harmful effects.

The study results faced limitations because most studies used observational or retrospective designs, which restricted researchers from establishing causal relationships while introducing multiple confounding factors.

The research findings lose their applicability to different settings because of existing differences in geographical areas, population demographics, and intervention methods.

5 Conclusion

The development of childhood respiratory and allergic diseases depends on the impact of early-life exposures and conditions. Factors such as viral infections, environmental pollutants, allergen exposure, and infant clinical characteristics consistently increase the risk of asthma, wheeze, and atopy. Nutritional supplementation during pregnancy and early probiotics demonstrate limited protective effects according to research findings. The research results demonstrate that preventive strategies need implementation during critical early-life periods, which include reducing exposure to respiratory viruses and allergens and environmental hazards while monitoring high-risk infants. The complete early-life approach establishes itself as the fundamental method to decrease childhood respiratory and allergic disorders while establishing pathways for sustained health benefits.

Statements

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Author contributions

RZ: Methodology, Supervision, Resources, Writing – original draft.

Funding

The author(s) declared that financial support was not received for this work and/or its publication.

Conflict of interest

The author(s) declared that this work was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declared that Generative AI was not used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1.

Shi T Ooi Y Zaw EM Utjesanovic N Campbell H Cunningham S et al . Association between respiratory syncytial virus-associated acute lower respiratory infection in early life and recurrent wheeze and asthma in later childhood. J Infect Dis. (2020) 222:S628–33. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiz311,

2.

Hansbro PM Starkey MR Mattes J Horvat JC . Pulmonary immunity during respiratory infections in early life and the development of severe asthma. Ann Am Thorac Soc. (2014) 11:S297–302. doi: 10.1513/AnnalsATS.201402-086AW,

3.

Man WH Van Houten MA Mérelle ME Vlieger AM Chu MLJ Jansen NJ et al . Bacterial and viral respiratory tract microbiota and host characteristics in children with lower respiratory tract infections: a matched case-control study. Lancet Respir Med. (2019) 7:417–26. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(18)30449-1,

4.

Roberts L Smith W Jorm L Patel M Douglas RM McGilchrist C . Effect of infection control measures on the frequency of upper respiratory infection in child care: a randomized, controlled trial. Pediatrics. (2000) 105:738–42. doi: 10.1542/peds.105.4.738,

5.

Liu S Hu P Du X Zhou T Pei X . Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG supplementation for preventing respiratory infections in children: a meta-analysis of randomized, placebo-controlled trials. Indian Pediatr. (2013) 50:377–81. doi: 10.1007/s13312-013-0123-z,

6.

Rosas-Salazar C Chirkova T Gebretsadik T Chappell JD Peebles RS Dupont WD et al . Respiratory syncytial virus infection during infancy and asthma during childhood in the USA (INSPIRE): a population-based, prospective birth cohort study. Lancet. (2023) 401:1669–80. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(23)00811-5,

7.

Gibson PG Wlodarczyk JW Hensley MJ Gleeson M Henry RL Cripps AW et al . Epidemiological association of airway inflammation with asthma symptoms and airway hyperresponsiveness in childhood. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. (1998) 158:36–41. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.158.1.9705031,

8.

Leuppi J Salome C Jenkins C Koskela H Brannan J Anderson S et al . Markers of airway inflammation and airway hyperresponsiveness in patients with well-controlled asthma. Eur Respir J. (2001) 18:444–50. doi: 10.1183/09031936.01.00058601,

9.

Medeleanu MV . Identifying the impact of early-life lower respiratory tract infections on the development of preschool asthma and atopic disease in the CHILD study. Canada: University of Toronto (2024).

10.

Li J Ren L Liu J Tang Y Wang R Yang P et al . The clinical registry of childhood asthma (CRCA) elucidating early-life asthma: cross-sectional analysis of a prospective, longitudinal, and digitally enhanced real-world cohort. J Med Internet Res. (2025) 27:e78693. doi: 10.2196/78693,

11.

Elvebakk T Døllner H Partty A Jartti H Vuorinen T Øymar K et al . Innovative steroid treatment to reduce asthma development in children after first-time rhinovirus-induced wheezing (INSTAR): protocol for a randomised placebo-controlled trial. BMJ Open. (2025) 15:e103530. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2025-103530,

12.

Songnuy T Ninla-Aesong P Thairach P Thok-Ngaen J . Effectiveness of an antioxidant-rich diet on childhood asthma outcomes: a randomized controlled trial. BMC Nutr. (2025) 11:1–12. doi: 10.1186/s40795-025-01078-2,

13.

Bärebring L Nwaru BI Lamberg-Allardt C Thorisdottir B Ramel A Söderlund F et al . Supplementation with long chain n-3 fatty acids during pregnancy, lactation, or infancy in relation to risk of asthma and atopic disease during childhood: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled clinical trials. Food Nutr Res. (2022) 66:842. doi: 10.29219/fnr.v66.8842,

14.

Yoshihara S Kusuda S Mochizuki H Okada K Nishima S Simões EA . Effect of palivizumab prophylaxis on subsequent recurrent wheezing in preterm infants. Pediatrics. (2013) 132:811–8. doi: 10.1542/peds.2013-0982,

15.

Bar-Yoseph R Haddad J Hanna M Kessel I Kugelman A Hakim F et al . Long term follow-up of Palivizumab administration in children born at 29–32 weeks of gestation. Respir Med. (2019) 150:149–53. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2019.03.001,

16.

RSV Study Group . Palivizumab, a humanized respiratory syncytial virus monoclonal antibody, reduces hospitalization from respiratory syncytial virus infection in high-risk infants. The IMpact-RSV study group. Pediatrics. (1998) 102:531–7. doi: 10.1542/peds.102.3.531,

17.

Weiss ST Mirzakhani H Carey VJ O'Connor GT Zeiger RS Bacharier LB et al . Prenatal vitamin D supplementation to prevent childhood asthma: 15-year results from the vitamin D antenatal asthma reduction trial (VDAART). J Allergy Clin Immunol. (2024) 153:378–88. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2023.10.003,

18.

Azad MB Coneys JG Kozyrskyj AL Field CJ Ramsey CD Becker AB et al . Probiotic supplementation during pregnancy or infancy for the prevention of asthma and wheeze: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ. (2013) 347:471. doi: 10.1136/bmj.f6471,

19.

Mutius E Martinez FD . Vitamin D supplementation during pregnancy and the prevention of childhood asthma. N Engl J Med. (2020) 382:574–5. doi: 10.1056/NEJMe1915082,

20.

Guilbert TW Singh AM Danov Z Evans MD Jackson DJ Burton R et al . Decreased lung function after preschool wheezing rhinovirus illnesses in children at risk to develop asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol. (2011) 128:532–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2011.06.037,

21.

Gray DM Turkovic L Willemse L Visagie A Vanker A Stein DJ et al . Lung function in African infants in the Drakenstein child health study. Impact of lower respiratory tract illness. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. (2017) 195:212–20. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201601-0188OC,

22.

Van Meel ER Den Dekker HT Elbert NJ Jansen PW Moll HA Reiss IK et al . A population-based prospective cohort study examining the influence of early-life respiratory tract infections on school-age lung function and asthma. Thorax. (2018) 73:167–73. doi: 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2017-210149,

23.

Bui DS Lodge CJ Burgess JA Lowe AJ Perret J Bui MQ et al . Childhood predictors of lung function trajectories and future COPD risk: a prospective cohort study from the first to the sixth decade of life. Lancet Respir Med. (2018) 6:535–44. doi: 10.1016/s2213-2600(18)30100-0,

24.

Bønnelykke K Vissing NH Sevelsted A Johnston SL Bisgaard H . Association between respiratory infections in early life and later asthma is independent of virus type. J Allergy Clin Immunol. (2015) 136:81–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2015.02.024,

25.

Montgomery S Bahmanyar S Brus O Hussein O Kosma P Palme-Kilander C . Respiratory infections in preterm infants and subsequent asthma: a cohort study. BMJ Open. (2013) 3:e004034. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2013-004034,

26.

James KM Gebretsadik T Escobar GJ Wu P Carroll KN Li SX et al . Risk of childhood asthma following infant bronchiolitis during the respiratory syncytial virus season. J Allergy Clin Immunol. (2013) 132:227–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2013.01.009,

27.

Balekian DS Linnemann RW Hasegawa K Thadhani R Camargo JCA . Cohort study of severe bronchiolitis during infancy and risk of asthma by age 5 years. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. (2017) 5:92–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jaip.2016.07.004,

28.

Chan JY Stern DA Guerra S Wright AL Morgan WJ Martinez FD . Pneumonia in childhood and impaired lung function in adults: a longitudinal study. Pediatrics. (2015) 135:607–16. doi: 10.1542/peds.2014-3060,

29.

Niers L Martín R Rijkers G Sengers F Timmerman H Van Uden N et al . The effects of selected probiotic strains on the development of eczema (the PandA study). Allergy. (2009) 64:1349–58. doi: 10.1111/j.1398-9995.2009.02021.x

30.

Chonmaitree T Revai K Grady JJ Clos A Patel JA Nair S et al . Viral upper respiratory tract infection and otitis media complication in young children. Clin Infect Dis. (2008) 46:815–23. doi: 10.1086/528685,

31.

Daley D . The evolution of the hygiene hypothesis: the role of early-life exposures to viruses and microbes and their relationship to asthma and allergic diseases. Curr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol. (2014) 14:390–6. doi: 10.1097/ACI.0000000000000101,

32.

Jackson DJ Gangnon RE Evans MD Roberg KA Anderson EL Pappas TE et al . Wheezing rhinovirus illnesses in early life predict asthma development in high-risk children. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. (2008) 178:667–72. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200802-309OC,

33.

Nafstad P Magnus P Jaakkola JJ . Early respiratory infections and childhood asthma. Pediatrics. (2000) 106:e38. doi: 10.1542/peds.106.3.e38,

34.

Bisgaard H Hermansen MN Bønnelykke K Stokholm J Baty F Skytt NL et al . Association of bacteria and viruses with wheezy episodes in young children: prospective birth cohort study. BMJ. (2010) 341:c4978. doi: 10.1136/bmj.c4978,

35.

Roth DE Morris SK Zlotkin S Gernand AD Ahmed T Shanta SS et al . Vitamin D supplementation in pregnancy and lactation and infant growth. N Engl J Med. (2018) 379:535–46. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1800927,

36.

Blanken MO Rovers MM Molenaar JM Winkler-Seinstra PL Meijer A Kimpen JLL et al . Respiratory syncytial virus and recurrent wheeze in healthy preterm infants. N Engl J Med. (2013) 368:1791–9. doi: 10.1056/nejmoa1211917,

37.

Madhi SA Cutland CL Kuwanda L Weinberg A Hugo A Jones S et al . Influenza vaccination of pregnant women and protection of their infants. N Engl J Med. (2014) 371:918–31. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1401480,

38.

Nunes MC Cutland CL Jones S Downs S Weinberg A Ortiz JR et al . Efficacy of maternal influenza vaccination against all-cause lower respiratory tract infection hospitalizations in young infants: results from a randomized controlled trial. Clin Infect Dis. (2017) 65:1066–71. doi: 10.1093/cid/cix497,

39.

Scheltema NM Nibbelke EE Pouw J Blanken MO Rovers MM Naaktgeboren CA et al . Respiratory syncytial virus prevention and asthma in healthy preterm infants: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet Respir Med. (2018) 6:257–64. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(18)30055-9,

40.

Omer SB Clark DR Madhi SA Tapia MD Nunes MC Cutland CL et al . Efficacy, duration of protection, birth outcomes, and infant growth associated with influenza vaccination in pregnancy: a pooled analysis of three randomised controlled trials. Lancet Respir Med. (2020) 8:597–608. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(19)30479-5,

41.

Litonjua AA Lange NE Carey VJ Brown S Laranjo N Harshfield BJ et al . The vitamin D antenatal asthma reduction trial (VDAART): rationale, design, and methods of a randomized, controlled trial of vitamin D supplementation in pregnancy for the primary prevention of asthma and allergies in children. Contemp Clin Trials. (2014) 38:37–50. doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2014.02.006,

42.

Simoes EA Groothuis JR Carbonell-Estrany X Rieger CH Mitchell I Fredrick LM et al . Palivizumab prophylaxis, respiratory syncytial virus, and subsequent recurrent wheezing. J Pediatr. (2007) 151:34–42. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2007.02.032,

43.

Feltes TF Sondheimer HM Tulloh RM Harris BS Jensen KM Losonsky GA et al . A randomized controlled trial of motavizumab versus palivizumab for the prophylaxis of serious respiratory syncytial virus disease in children with hemodynamically significant congenital heart disease. Pediatr Res. (2011) 70:186–91. doi: 10.1203/pdr.0b013e318220a553,

44.

Mattila S Paalanne N Honkila M Pokka T Tapiainen T . Effect of point-of-care testing for respiratory pathogens on antibiotic use in children: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Netw Open. (2022) 5:e2216162-e. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2022.16162,

45.

Cabana MD McKean M Caughey AB Fong L Lynch S Wong A et al . Early probiotic supplementation for eczema and asthma prevention: a randomized controlled trial. Pediatrics. (2017) 140:e20163000. doi: 10.1542/peds.2016-3000,

46.

Abrahamsson TR Jakobsson T Böttcher MF Fredrikson M Jenmalm MC Björkstén B et al . Probiotics in prevention of IgE-associated eczema: a double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial. J Allergy Clin Immunol. (2007) 119:1174–80. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2007.01.007,

47.

Kalliomäki M Salminen S Arvilommi H Kero P Koskinen P Isolauri E . Probiotics in primary prevention of atopic disease: a randomised placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. (2001) 357:1076–9. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(00)04259-8

48.

Arrieta M-C Stiemsma LT Dimitriu PA Thorson L Russell S Yurist-Doutsch S et al . Early infancy microbial and metabolic alterations affect risk of childhood asthma. Sci Transl Med. (2015) 7:307ra152-307ra152. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aab2271,

49.

Patrick DM Sbihi H Dai DL Al Mamun A Rasali D Rose C et al . Decreasing antibiotic use, the gut microbiota, and asthma incidence in children: evidence from population-based and prospective cohort studies. Lancet Respir Med. (2020) 8:1094–105. doi: 10.1016/s2213-2600(20)30052-7,

50.

Kapszewicz K Podlecka D Polańska K Stelmach I Majak P Majkowska-Wojciechowska B et al . Home environment in early-life and lifestyle factors associated with asthma and allergic diseases among inner-city children from the REPRO_PL birth cohort. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2022) 19:11884. doi: 10.3390/ijerph191911884,

51.

Ramsey CD Gold DR Litonjua AA Sredl DL Ryan L Celedón JC . Respiratory illnesses in early life and asthma and atopy in childhood. J Allergy Clin Immunol. (2007) 119:150–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2006.09.012,

52.

Belachew AB Rantala AK Jaakkola MS Hugg TT Jaakkola JJ . Asthma and respiratory infections from birth to young adulthood: the Espoo cohort study. Am J Epidemiol. (2023) 192:408–19. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwac210,

53.

Stokholm J Sevelsted A Bønnelykke K Bisgaard H . Maternal propensity for infections and risk of childhood asthma: a registry-based cohort study. Lancet Respir Med. (2014) 2:631–7. doi: 10.1016/s2213-2600(14)70152-3

54.

Jackson DJ Evans MD Gangnon RE Tisler CJ Pappas TE Lee W-M et al . Evidence for a causal relationship between allergic sensitization and rhinovirus wheezing in early life. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. (2012) 185:281–5. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201104-0660OC,

55.

Karvonen AM Hyvarinen A Roponen M Hoffmann M Korppi M Remes S et al . Confirmed moisture damage at home, respiratory symptoms and atopy in early life: a birth-cohort study. Pediatrics. (2009) 124:e329–38. doi: 10.1542/peds.2008-1590,

56.

Roda C Kousignian I Guihenneuc-Jouyaux C Dassonville C Nicolis I Just J et al . Formaldehyde exposure and lower respiratory infections in infants: findings from the PARIS cohort study. Environ Health Perspect. (2011) 119:1653–8. doi: 10.1289/ehp.1003222,

57.

Torrent M Sunyer J Garcia R Harris J Iturriaga MV Puig C et al . Early-life allergen exposure and atopy, asthma, and wheeze up to 6 years of age. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. (2007) 176:446–53. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200607-916oc,

58.

Lau S Illi S Sommerfeld C Niggemann B Bergmann R von Mutius E et al . Early exposure to house-dust mite and cat allergens and development of childhood asthma: a cohort study. Lancet. (2000) 356:1392–7. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(00)02842-7,

59.

Illi S von Mutius E Lau S Niggemann B Grüber C Wahn U . Perennial allergen sensitisation early in life and chronic asthma in children: a birth cohort study. Lancet. (2006) 368:763–70. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69286-6,

60.

Carroll KN Wu P Gebretsadik T Griffin MR Dupont WD Mitchel EF et al . The severity-dependent relationship of infant bronchiolitis on the risk and morbidity of early childhood asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol. (2009) 123:1055–61. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2009.02.021,

61.

Stern DA Morgan WJ Halonen M Wright AL Martinez FD . Wheezing and bronchial hyper-responsiveness in early childhood as predictors of newly diagnosed asthma in early adulthood: a longitudinal birth-cohort study. Lancet. (2008) 372:1058–64. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61447-6,

62.

Klopp A Vehling L Becker AB Subbarao P Mandhane PJ Turvey SE et al . Modes of infant feeding and the risk of childhood asthma: a prospective birth cohort study. J Pediatr. (2017) 190:192–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2017.07.012,

63.

Chawes BL Bønnelykke K Jensen PF Schoos A-MM Heickendorff L Bisgaard H . Cord blood 25 (OH)-vitamin D deficiency and childhood asthma, allergy and eczema: the COPSAC2000 birth cohort study. PLoS One. (2014) 9:e99856. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0099856,

64.

De Marco R Pattaro C Locatelli F Svanes C Group ES . Influence of early life exposures on incidence and remission of asthma throughout life. J Allergy Clin Immunol. (2004) 113:845–52. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2004.01.780,

65.

Grabenhenrich LB Gough H Reich A Eckers N Zepp F Nitsche O et al . Early-life determinants of asthma from birth to age 20 years: a German birth cohort study. J Allergy Clin Immunol. (2014) 133:979–88. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2013.11.035,

66.

Matheson MC Dharmage SC Abramson MJ Walters EH Sunyer J De Marco R et al . Early-life risk factors and incidence of rhinitis: results from the European Community respiratory health study—an international population-based cohort study. J Allergy Clin Immunol. (2011) 128:816–823.e5. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2011.05.039

67.

Örtqvist AK Lundholm C Kieler H Ludvigsson JF Fall T Ye W et al . Antibiotics in fetal and early life and subsequent childhood asthma: nationwide population based study with sibling analysis. BMJ. (2014) 349:g6979. doi: 10.1136/bmj.g6979,

68.

Rhodes HL Sporik R Thomas P Holgate ST Cogswell JJ . Early life risk factors for adult asthma: a birth cohort study of subjects at risk. J Allergy Clin Immunol. (2001) 108:720–5. doi: 10.1067/mai.2001.119151

69.

Holt PG Rowe J Kusel M Parsons F Hollams EM Bosco A et al . Toward improved prediction of risk for atopy and asthma among preschoolers: a prospective cohort study. J Allergy Clin Immunol. (2010) 125:653–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2009.12.018,

70.

Sigurdardottir ST Jonasson K Clausen M Lilja Bjornsdottir K Sigurdardottir SE Roberts G et al . Prevalence and early-life risk factors of school-age allergic multimorbidity: the EuroPrevall-iFAAM birth cohort. Allergy. (2021) 76:2855–65. doi: 10.1111/all.14857,

71.

Kusel MM De Klerk NH Kebadze T Vohma V Holt PG Johnston SL et al . Early-life respiratory viral infections, atopic sensitization, and risk of subsequent development of persistent asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol. (2007) 119:1105–10. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2006.12.669,

72.

McKeever TM Lewis SA Smith C Collins J Heatlie H Frischer M et al . Early exposure to infections and antibiotics and the incidence of allergic disease: a birth cohort study with the west midlands general practice research database. J Allergy Clin Immunol. (2002) 109:43–50. doi: 10.1067/mai.2002.121016

73.

Salam MT Li Y-F Langholz B Gilliland FD . Early-life environmental risk factors for asthma: findings from the children's health study. Environ Health Perspect. (2004) 112:760. doi: 10.1289/ehp.6662,

74.

Van Meel ER Mensink-Bout SM den Dekker HT Ahluwalia TS Annesi-Maesano I Arshad SH et al . Early-life respiratory tract infections and the risk of school-age lower lung function and asthma: a meta-analysis of 150 000 European children. Eur Respir J. (2022) 60:2102395. doi: 10.1183/13993003.02395-2021,

75.

Jin J Zhou Y-Z Gan Y-C Song J Li W-M . Early-life respiratory infections are pivotal in the progression of asthma-a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Clin Exp Med. (2017) 10:11.

76.

Wang G Han D Jiang Z Li M Yang S Liu L . Association between early bronchiolitis and the development of childhood asthma: a meta-analysis. BMJ Open. (2021) 11:e043956. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2020-043956,

77.

Wadhwa V Lodge CJ Dharmage SC Cassim R Sly PD Russell MA . The association of early life viral respiratory illness and atopy on asthma in children: systematic review and meta-analysis. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. (2020) 8:2663–72. doi: 10.1016/j.jaip.2020.03.032,

78.

Liu L Pan Y Zhu Y Song Y Su X Yang L et al . Association between rhinovirus wheezing illness and the development of childhood asthma: a meta-analysis. BMJ Open. (2017) 7:e013034. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-013034,

79.

Bisgaard H Stokholm J Chawes BL Vissing NH Bjarnadóttir E Schoos A-MM et al . Fish oil–derived fatty acids in pregnancy and wheeze and asthma in offspring. N Engl J Med. (2016) 375:2530–9. doi: 10.1056/nejmoa1503734,

80.

To T Zhu J Stieb D Gray N Fong I Pinault L et al . Early life exposure to air pollution and incidence of childhood asthma, allergic rhinitis and eczema. Eur Respir J. (2020) 55:19. doi: 10.1183/13993003.00913-2019,

81.

Aguilera I Pedersen M Garcia-Esteban R Ballester F Basterrechea M Esplugues A et al . Early-life exposure to outdoor air pollution and respiratory health, ear infections, and eczema in infants from the INMA study. Environ Health Perspect. (2012) 121:387. doi: 10.1289/ehp.1205281,

82.

Sin DD Spier S Svenson LW Schopflocher DP Senthilselvan A Cowie RL et al . The relationship between birth weight and childhood asthma: a population-based cohort study. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. (2004) 158:60–4. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.158.1.60,

83.

Gehring U Wijga AH Hoek G Bellander T Berdel D Brüske I et al . Exposure to air pollution and development of asthma and rhinoconjunctivitis throughout childhood and adolescence: a population-based birth cohort study. Lancet Respir Med. (2015) 3:933–42. doi: 10.1016/s2213-2600(15)00426-9,

84.

MacIntyre EA Gehring U Mölter A Fuertes E Klümper C Krämer U et al . Air pollution and respiratory infections during early childhood: an analysis of 10 European birth cohorts within the ESCAPE project. Environ Health Perspect. (2013) 122:107. doi: 10.1289/ehp.1306755,

Summary

Keywords

childhood asthma, early-life respiratory infections, maternal vaccination, RSV prophylaxis, wheezing

Citation