Abstract

Introduction:

This case highlights an uncommon presentation of Vogt–Koyanagi–Harada (VKH) syndrome, in which acute angle-closure glaucoma (AACG) served as the initial ocular manifestation. This atypical onset may lead to misdiagnosis as primary angle-closure glaucoma. This report adds to the existing literature by emphasizing the diagnostic value of ciliary body imaging and the mechanistic link between inflammatory ciliary body detachment and secondary angle closure.

Case presentation:

A 27-year-old woman presented with acute ocular pain, vision loss, and markedly elevated intraocular pressure (IOP). Important clinical findings included conjunctival congestion, corneal edema, medium-depth anterior chambers, and the absence of keratic precipitates or aqueous flare. Ultrasound biomicroscopy revealed a ciliary body detachment, whereas optical coherence tomography revealed multiple serous retinal detachments. The patient was initially misdiagnosed with glaucoma before a revised diagnosis of VKH syndrome-associated secondary AACG was made.

Interventions and outcomes:

The patient was treated with intravenous methylprednisolone pulse therapy combined with topical corticosteroids, mydriatic agents, and IOP-lowering agents. Visual acuity and IOP gradually improved, and subretinal fluid completely resolved during follow-up.

Conclusion:

VKH syndrome rarely presents with AACG as the initial manifestation. Awareness of this presentation and careful imaging evaluation are essential to avoid misdiagnosis. Early and aggressive anti-inflammatory therapy remains key to reversing both angle closure and retinal pathology. This case highlights the importance of considering autoimmune uveitis in patients with atypical angle-closure glaucoma.

1 Introduction

Vogt–Koyanagi–Harada (VKH) syndrome is an autoimmune disease that primarily affects melanocytes and predominantly affects individuals aged 20–50 years. The hallmark of this syndrome is bilateral granulomatous panuveitis, often accompanied by systemic manifestations, including decreased hearing and vision, headache, tinnitus, and vitiligo (1, 2). The course of VKH syndrome is complex, with a high rate of misdiagnosis and missed diagnosis in the early stages. This disease is easily misdiagnosed as sympathetic ophthalmia, birdshot retinochoroidopathy, and Behçet’s disease (3). Moreover, complications are commonly mistaken for primary disease (4). In some cases, VKH syndrome can be misdiagnosed as primary acute angle-closure glaucoma (AACG), presenting with peripheral anterior synechiae and increased intraocular pressure (IOP). However, AACG, as the first ocular manifestation of VKH syndrome, is uncommon (1). Its pathogenesis may involve acute inflammatory edema, disruption of the blood–aqueous humor barrier in the ciliary body, or forward rotation of the iris–lens diaphragm (5, 6). Herein, we present a case of VKH syndrome with AACG as the initial manifestation and investigate its underlying pathogenesis.

2 Case presentation

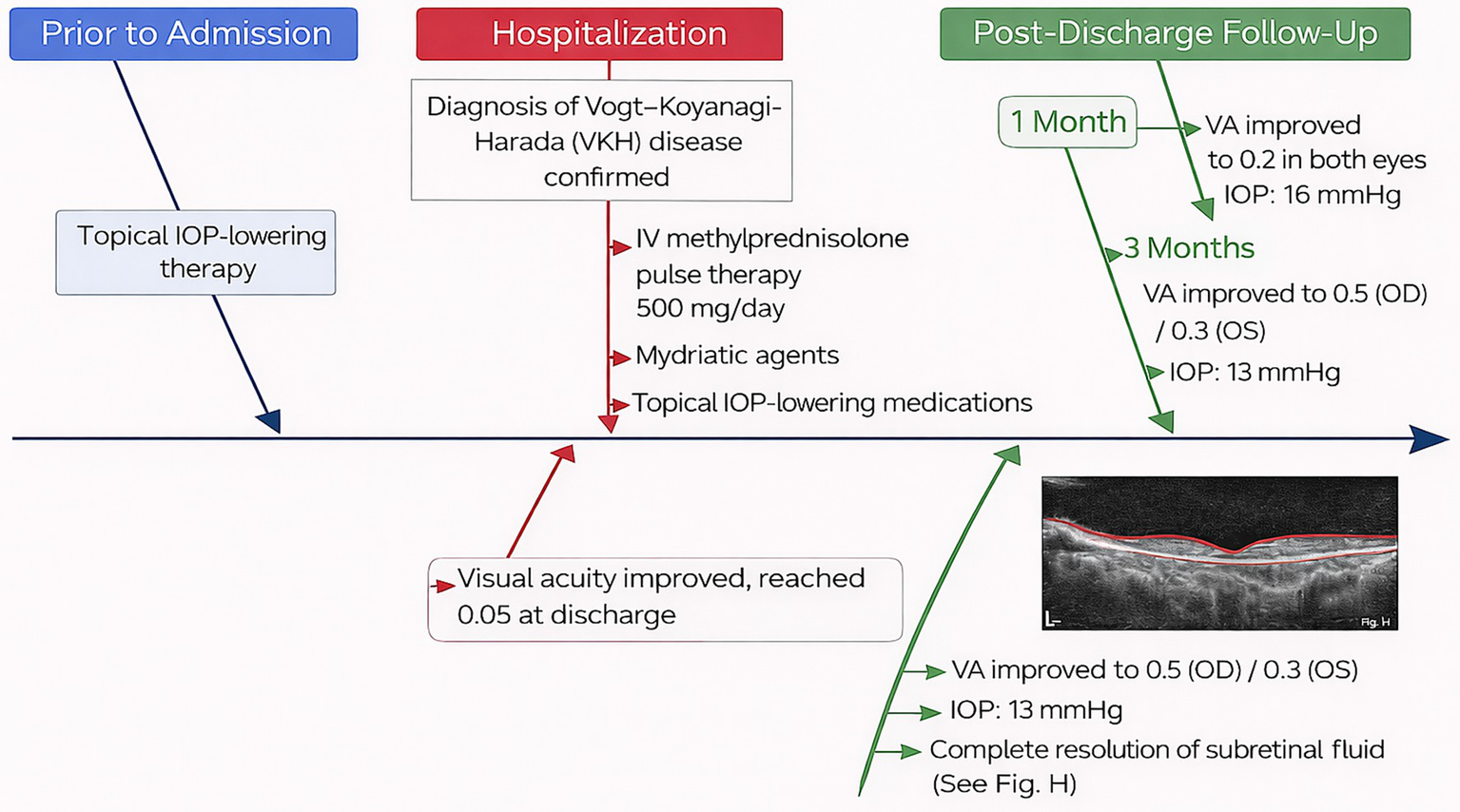

A 27-year-old woman was admitted for treatment of red eyes, ocular pain, increased IOP, and self-perceived decreased vision (near-absent light perception) for 2 days. The patient had been diagnosed with glaucoma at another hospital 1 day before admission and underwent glaucoma treatment, after which IOP decreased; however, vision continued to deteriorate progressively. After admission, relevant examinations were performed, and the findings suggested that the initial manifestation was VKH syndrome with AACG. Anterior segment photography (after pupil dilation) showed conjunctival congestion with edema, corneal opacity, absence of keratic precipitates, medium-depth anterior chambers, and absence of aqueous flare (−) (Figures 1A,B). Notably, ultrasound biomicroscopy revealed ciliary body detachment (Figures 1C,D). Secondary angle-closure glaucoma in eyes with uveitis can result from several mechanisms, including angle closure with pupillary block, which occurs when anterior chamber inflammation leads to 360° posterior synechiae, as well as inflammation and edema causing forward rotation of the ciliary body and angle closure. Optical coherence tomography of both eyes revealed multiple serous retinal detachments at the posterior pole (Figures 1E,F). Fundus fluorescein angiography revealed diffuse fluorescein leakage and staining (Figures 1G,H). Before admission, the patient had received topical IOP-lowering therapy. After admission, following the confirmation of a diagnosis of VKH syndrome, intravenous methylprednisolone pulse therapy (500 mg/day) was initiated in combination with mydriatic agents and topical IOP-lowering medications. Visual acuity gradually improved and reached 0.05 at discharge. At the 1-month follow-up, visual acuity had improved to 0.2 in both eyes, with an IOP of 16 mmHg. At the 3-month follow-up, visual acuity further improved to 0.5 in the right eye and 0.3 in the left eye, with an IOP of 13 mmHg, and complete resolution of subretinal fluid was observed. The patient’s diagnostic and therapeutic course is shown in Figure 2.

Figure 1

After outpatient pupil dilation, anterior segment photography shows conjunctival congestion with edema, corneal opacity, absence of keratic precipitates, medium-deep anterior chambers, and absence of aqueous flare (A,B). Ultrasound biomicroscopy reveals ciliary body detachment (C,D). Optical coherence tomography demonstrates multiple serous retinal detachments involving the posterior pole in both eyes (E,F). Fundus fluorescein angiography shows diffuse fluorescein leakage and staining (G,H).

Figure 2

Diagnostic and therapeutic course of the patient from pre-admission to follow-up, illustrating the sequence of management and disease progression. IOP, intraocular pressure.

3 Diagnosis of VKH syndrome

The diagnosis of VKH syndrome was established according to the revised diagnostic criteria of the International Committee on VKH Disease. This patient exhibited the following features:

-

Bilateral ocular involvement.

-

Serous retinal detachments on optical coherence tomography.

-

Ciliary body detachment, suggesting choroidal inflammation.

-

Systemic features, including headache.

-

Absence of keratic precipitates, infectious symptoms, or a history of trauma.

HLA-DR4/DRB104 testing, while supportive, was not performed because the diagnosis was sufficiently supported by clinical findings and multimodal imaging.

4 Discussion

4.1 Pathophysiological interplay

The exact pathophysiological mechanisms underlying the association between VKH syndrome and AACG remain incompletely understood (7, 8). Current evidence suggests that the primary mechanisms include posterior iris adhesion with pupillary block, anterior chamber angle occlusion, trabecular meshwork inflammation, accumulation of inflammatory cells near the trabecular meshwork, and long-term use of glucocorticoids (9). Notably, this patient did not exhibit angle recession but instead demonstrated ciliary body detachment, which we believe was the primary cause of elevated IOP. This finding is consistent with that of previous reports (10). Detachment of the ciliary body leads to zonular laxity, allowing anterior displacement of the lens and subsequent compression of the iris, resulting in pupillary block. This obstruction impairs aqueous humor flow from the posterior to the anterior chamber, ultimately leading to the development of malignant glaucoma. Differential diagnoses, including sympathetic ophthalmia, infectious uveitis, central serous chorioretinopathy, and primary AACG, were excluded based on clinical features and imaging findings.

4.2 Treatment considerations

Management of VKH syndrome-associated AACG requires a comprehensive approach that addresses both the underlying inflammatory and mechanical components of the disease (11, 12). In this case, the patient underwent the following interventions.

4.3 Systemic corticosteroids

Systemic corticosteroids (intravenous methylprednisolone, 500 mg/day for 5 days) were administered to treat the acute inflammatory process. This high-dose therapy aims to reduce inflammation, alleviate pupillary block, and prevent further complications, such as retinal detachment. The dosage was gradually tapered over several weeks to minimize adverse effects associated with prolonged steroid use, in accordance with standard management strategies for autoimmune uveitis (13, 14).

4.4 Topical corticosteroids

Topical corticosteroid eye drops were administered to reduce anterior segment inflammation. The dosage and frequency were adjusted according to the severity of anterior chamber inflammation and corneal edema and were gradually tapered once inflammation was adequately controlled.

4.5 Mydriatic therapy

Mydriatic agents were used to induce pupil dilation and relieve pupillary block caused by anterior displacement of the lens. Mydriatic therapy helped maintain pupillary dilation and reduce elevated IOP secondary to forward displacement of the lens–iris diaphragm resulting from ciliary body detachment.

4.6 Changes in interventions

During the course of treatment, the initial priority was controlling elevated IOP, a critical concern in secondary angle-closure glaucoma. As the patient’s condition improved, corticosteroid therapy was gradually tapered to reduce potential adverse effects. Visual acuity and IOP normalized, and subretinal fluid progressively resolved during follow-up visits at 1 and 3 months.

4.7 Rationale for treatment changes

The initial use of systemic corticosteroids was essential for controlling inflammation and secondary angle closure caused by ciliary body detachment and pupillary block.

Corticosteroids were tapered as the patient’s condition stabilized, following established protocols to minimize complications associated with prolonged steroid use while maintaining inflammatory control.

The use of mydriatic agents was critical for preventing further IOP elevation and improving patient comfort by alleviating pupillary block.

These treatment strategies are consistent with established clinical guidelines for VKH syndrome-associated AACG and were selected to address both the acute and chronic aspects of the disease while accounting for the patient’s individual response (7, 14, 15).

5 Conclusion

This case report provides important insights into the pathogenesis and clinical decision-making involved in VKH syndrome-associated AACG. Early recognition of systemic symptoms, appropriate imaging evaluation, and a multidisciplinary treatment approach are essential for optimizing outcomes and preventing irreversible visual loss.

Statements

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Ethics statement

Written informed consent was obtained from the individual(s) for the publication of any potentially identifiable images or data included in this article. Written informed consent was obtained from the participant/patient(s) for the publication of this case report.

Author contributions

FL: Writing – original draft. DW: Writing – original draft. XZ: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declared that financial support was received for this work and/or its publication. This study was supported by the 2024 Zhongshan City First Batch of Social Welfare and Basic Research Project (2024B1140) and the 2024 Zhongshan City Traditional Chinese Medicine Inheritance and Innovation Development Research Special Fund (2024B3055).

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Editage (www.editage.cn) for English language editing.

Conflict of interest

The author(s) declared that this work was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declared that Generative AI was not used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1.

Bai X Hua R . Case Report: Vogt–Koyanagi–Harada syndrome mimicking acute angle-closure glaucoma in a patient infected with human immunodeficiency virus. Front Med. (2022) 8:752002. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2021.752002,

2.

Urzua CA Herbort CP Takeuchi M Schlaen A Concha-del-Rio LE Usui Y et al . Vogt–Koyanagi–Harada disease: the step-by-step approach to a better understanding of clinicopathology, immunopathology, diagnosis, and management: a brief review. J Ophthalmic Inflamm Infect. (2022) 12:17. doi: 10.1186/s12348-022-00293-3,

3.

See WS Sawri Rajan R Alexander SM . Diagnostic and management challenges in atypical central serous chorioretinopathy mimicking Vogt–Koyanagi–Harada disease: a case report. Cureus. (2025) 17:e91080. doi: 10.7759/cureus.91080,

4.

Patyal S Narula R Thulasidas M . Vogt–Koyanagi–Harada disease associated with anterior ischemic optic neuropathy in a young woman presenting as acute angle closure glaucoma. Indian J Ophthalmol. (2020) 68:1937. doi: 10.4103/ijo.IJO_793_20,

5.

Iwahashi C Fukuda M Makita S Takahashi A Kurihara T Sugioka K et al . A rare case of membrane pupillary-block glaucoma in a phakic eye with uveitis. BMC Ophthalmol. (2025) 25:358. doi: 10.1186/s12886-025-04191-9,

6.

Yao J Chen Y Shao T Ling Z Wang W Qian S . Bilateral acute angle closure glaucoma as a presentation of Vogt–Koyanagi–Harada syndrome in four Chinese patients: a small case series. Ocul Immunol Inflamm. (2013) 21:286–91. doi: 10.3109/09273948.2013.792937,

7.

Abu El-Asrar AM Van Damme J Struyf S Opdenakker G . New perspectives on the immunopathogenesis and treatment of uveitis associated with Vogt–Koyanagi–Harada disease. Front Med. (2021) 8:705796. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2021.705796,

8.

Baltmr A Lightman S Tomkins-Netzer O . Vogt–Koyanagi–Harada syndrome—current perspectives. Clin Ophthalmol. (2016) 10:2345–61. doi: 10.2147/OPTH.S94866,

9.

Joye A Suhler E . Vogt–Koyanagi–Harada disease. Curr Opin Ophthalmol. (2021) 32:574–82. doi: 10.1097/ICU.0000000000000809,

10.

Yang P Wang C Su G Pan S Qin Y Zhang J et al . Prevalence, risk factors and management of ocular hypertension or glaucoma in patients with Vogt–Koyanagi–Harada disease. Br J Ophthalmol. (2021) 105:1678–82. doi: 10.1136/bjophthalmol-2020-316323,

11.

Ceballos EM Beck AD Lynn MJ . Trabeculectomy with antiproliferative agents in uveitic glaucoma. J Glaucoma. (2002) 11:189–96. doi: 10.1097/00061198-200206000-00005,

12.

Siddique SS Suelves AM Baheti U Foster CS . Glaucoma and uveitis. Surv Ophthalmol. (2013) 58:1–10. doi: 10.1016/j.survophthal.2012.04.006,

13.

Friedman DS Holbrook JT Ansari H Alexander J Burke A Reed SB et al . Risk of elevated intraocular pressure and glaucoma in patients with uveitis. Ophthalmology. (2013) 120:1571–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2013.01.025,

14.

Ozge G Karaca U Savran M Usta G Gulle K Sevimli M et al . Salubrinal ameliorates inflammation and neovascularization via the caspase 3/eNOS signaling in an alkaline-induced rat corneal neovascularization model. Medicina. (2023) 59:323. doi: 10.3390/medicina59020323,

15.

Commodaro AG Bueno V Belfort R Rizzo LV . Autoimmune uveitis: the associated proinflammatory molecules and the search for immunoregulation. Autoimmun Rev. (2011) 10:205–9. doi: 10.1016/j.autrev.2010.10.002,

Summary

Keywords

case report, ciliary body detachment, secondary angle-closure glaucoma, ultrasound biomicroscopy, Vogt–Koyanagi–Harada syndrome

Citation

Li F, Wu D and Zhu X (2026) Case Report: Vogt–Koyanagi–Harada syndrome complicated by secondary glaucoma: diagnostic insights and mechanistic correlations in uveitic ocular hypertension. Front. Med. 13:1755451. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2026.1755451

Received

27 November 2025

Revised

20 January 2026

Accepted

26 January 2026

Published

10 February 2026

Volume

13 - 2026

Edited by

Ilaria Testi, Moorfields Eye Hospital NHS Foundation Trust, United Kingdom

Reviewed by

Azzurra Invernizzi, Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, United States

Indra Tri Mahayana, Gadjah Mada University, Indonesia

Updates

Copyright

© 2026 Li, Wu and Zhu.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Xiaowei Zhu, xiaowei8338@126.com

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.