Abstract

Objective:

To evaluate the effectiveness of transcutaneous electrical acupoint stimulation (TEAS) in relieving postoperative pain and reducing the incidence of postoperative nausea and vomiting (PONV) in patients undergoing cancer surgery.

Methods:

A systematic search was conducted in PubMed, Web of Science, Embase, the Cochrane Library, CNKI, and Wanfang databases to identify randomized controlled trials (RCTs) published between January 2015 and May 2025. Postoperative pain scores at different time points, assessed using the visual analog scale (VAS) or numerical rating scale (NRS), as well as the incidence of PONV, postoperative nausea (PON), and postoperative vomiting (POV), were extracted. Subgroup analyses were performed according to the timing of TEAS intervention and pain assessment methods. The risk of bias was evaluated using the Cochrane Risk of Bias (RoB) tool, and the meta-analysis was conducted using RevMan 5.4 software.

Results:

A total of 16 randomized controlled trials involving 2,017 postoperative cancer patients were included (1,125 in the TEAS group and 892 in the control group). Meta-analysis of 13 studies showed that TEAS significantly reduced postoperative pain scores (SMD = −1.19, 95% CI: −1.42 to −0.95, p < 0.00001). Eleven studies indicated that TEAS decreased the incidence of PONV (RR = 0.47.95% CI:0.37~0.61, P<0.00001). Four studies were included in the meta-analysis of postoperative nausea, showing a significant reduction in incidence in the TEAS group compared to controls (RR = 0.33, 95% CI: 0.22 to 0.49, p < 0.00001). Another four studies showed a downward trend in postoperative vomiting but without statistical significance (RR = 0.69, 95% CI: 0.44 to 1.09, p = 0.11).

Conclusion:

TEAS appears to be an effective adjunctive intervention for alleviating postoperative pain and nausea in patients undergoing cancer surgery, showing clear clinical advantages. Further high-quality, large-scale, and multicenter studies are warranted to confirm its long-term efficacy and to promote the standardization of TEAS protocols for broader clinical application.

Systematic review registration:

1 Introduction

Surgical treatment is one of the primary modalities for cancer treatment, with common postoperative complications including pain, postoperative nausea and vomiting (PONV), sleep disturbances, and gastrointestinal dysfunction (1, 2). Among these, postoperative pain and PONV are considered the most prevalent symptoms, with incidence rates ranging from 30 to 80% (3–5). These complications not only exacerbate patients’ physical distress but also contribute to anxiety and depression, which can affect treatment adherence and postoperative recovery (6). Additionally, some patients may undergo chemotherapy or radiotherapy, whose side effects further impair the overall health condition (7).

In cancer surgery, especially in procedures involving extensive tissue resection or organ reconstruction, postoperative pain tends to be more severe. Conventional pain management strategies, including patient-controlled analgesia (PCA) pumps and opioid use, are commonly employed (8). While effective in pain relief, these strategies are often associated with notable adverse effects such as respiratory depression, nausea, vomiting, and tolerance (9). PONV, being a common postoperative complication, is typically managed with antiemetic drugs such as 5-HT₃ receptor antagonists; however, their effectiveness is inconsistent, and they may lead to side effects like headaches and constipation (10, 11). Therefore, exploring a safe, low side-effect, and patient-compliant non-pharmacological intervention is of significant clinical importance.

Transcutaneous Electrical Acupoint Stimulation (TEAS), a non-invasive treatment that applies low-frequency electrical stimulation through skin electrodes at specific acupoints, is often referred to as “needleless acupuncture.” Transcutaneous Electrical Nerve Stimulation (TENS) is also a non-invasive electrical stimulation technique, and in many studies, stimulation is similarly applied at defined acupoints. Both approaches are easy to administer and repeatable, and they have gained attention in perioperative pain management and PONV prevention (12–14). Several systematic reviews and meta-analyses have demonstrated that TEAS can significantly improve postoperative recovery outcomes across various surgical populations. These benefits include enhanced overall quality of recovery, reduced postoperative pain—particularly within the first 72 h after surgery—and decreased opioid consumption, highlighting TEAS as a promising non-pharmacological adjunctive intervention (15, 16). In addition, Liu et al. (17) and Wu et al. (18) demonstrated that TEAS is effective in reducing PONV, especially among patients receiving general anesthesia, further supporting its role in perioperative symptom management.

However, patients undergoing cancer-related surgery often experience a higher postoperative symptom burden due to tumor-related factors and prior treatments, such as chemotherapy. Despite this, evidence specifically addressing the effects of TEAS on postoperative pain and PONV in cancer patients remains limited. Therefore, the present study systematically assessed the efficacy of TEAS in patients undergoing cancer-related surgery, with postoperative nausea (PON) and postoperative vomiting (POV) analyzed as separate outcomes. Furthermore, this review incorporates randomized controlled trials published in the past decade, thereby enhancing the timeliness and completeness of the evidence and providing a more robust evidence base for the application of TEAS in postoperative rehabilitation among cancer patients.

2 Methods

2.1 Protocol and registration

This meta-analysis has been prospectively registered on the International Systematic Review platform, PROSPERO (registration number: CRD420251038890). A systematic literature review and quantitative synthesis approach were used to assess the effects of TEAS on postoperative pain and PONV in cancer patients. The literature selection, data extraction, and statistical analysis were conducted in accordance with the PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) statement and the AMSTAR (A Measurement Tool to Assess Systematic Reviews) guidelines for systematic review methodology and quality assessment (19–21).

2.2 Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Two researchers independently screened the literature. We included RCTs published from January 2015 to May 2025 that assessed TEAS for postoperative pain control and/or PONV prevention in surgical patients with cancer. TEAS was administered using surface electrodes at predefined acupoints, while comparators were conventional medication or placebo/sham stimulation. No limits were set on age, sex, ethnicity, or country. We excluded non-RCT designs (e.g., reviews, case reports, crossover trials, commentaries, and retrospective studies), animal studies, and studies in which outcome data required for meta-analysis were not available in extractable quantitative form (e.g., continuous outcomes without mean and SD/SE, or dichotomous outcomes without event counts, or outcomes reported only graphically without sufficient numerical information).

The primary outcome measures included postoperative pain (assessed using the Numerical Rating Scale [NRS] and Visual Analog Scale [VAS]) and the incidence of PONV, including PON and POV. Secondary outcomes included the use of postoperative analgesics and the reporting of TEAS-related adverse events.

2.3 Search strategy

We conducted systematic searches in six databases: PubMed, EMBASE, Web of Science, Cochrane Library, CNKI, and Wanfang, covering articles from database inception to May 5, 2025. The search strategy combined Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) and free text terms. The key search terms included ‘Transcutaneous Electrical Acupoint Stimulation,’ ‘Postoperative Pain,’ ‘Postoperative Nausea and Vomiting,’ and ‘Cancer’ in both English and Chinese, tailored to each database’s indexing format. Boolean operators “AND” and “OR” were used to combine terms, with adjustments made according to the characteristics of each database. To reduce publication bias, we also searched ClinicalTrials.gov and the Chinese Clinical Trial Registry, but no relevant studies were found. Additionally, we supplemented our search by reviewing the reference lists of included studies. An example of the detailed search strategy used for PubMed is provided in Supplementary File S1.

2.4 Literature screening and data extraction

Two researchers independently conducted the literature screening and data extraction according to the standards outlined in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (22). Any discrepancies during the screening process were resolved by a third researcher, who made the final decision.

The literature screening process involved the following steps: First, we screened the titles and abstracts to exclude obviously irrelevant studies. Then, full-text articles were reviewed to further assess eligibility based on the inclusion and exclusion criteria. Finally, the reference lists of the included studies were manually searched to identify any additional relevant studies that may have been missed.

The data extracted from the eligible studies covered study details (e.g., authors, year of publication, country, and study setting), patient characteristics (sample size, age, sex, and type of surgery), and intervention information (TEAS acupoints, stimulation frequency and intensity, session duration, and treatment cycle). We also collected outcome data, including postoperative pain scores, the incidence of PONV, the number of nausea and vomiting episodes, analgesic use, and any TEAS-related adverse events. Risk of bias was assessed using the ROB tool. However, the number of nausea and vomiting episodes was not pooled due to the limited number of studies reporting this data. When key data were missing or unclear, we contacted the study authors to request the original information.

2.5 Risk of bias

The Cochrane Risk of Bias (ROB) assessment tool was used to evaluate the risk of bias in the included randomized controlled trials (RCTs), with two researchers independently assessing each study. The evaluation covered seven domains: randomization process, allocation concealment, blinding of interventions, blinding of outcome assessment, completeness of outcome data, selective reporting, and other potential biases. Each domain was rated as “low risk,” “high risk,” or “unclear” based on the information provided in the studies.

2.6 Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using RevMan 5.4 software, following the guidance of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions. For dichotomous variables, the relative risk (RR) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were used to assess the effect size. For continuous variables, the mean difference (MD) or standardized mean difference (SMD) and 95% CI were calculated. Different pain scoring tools, including the VAS and NRS, were both used to assess pain. Previous studies suggest a good correlation between the two (23), and the Cochrane Handbook recommends combining studies using different scales to assess the same continuous outcome using SMD (24). Subgroup analyses were performed based on postoperative time points and the type of pain scale used. A p-value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant (25).

Heterogeneity was assessed using the Chi-square test and the I2 statistic. If I2 > 50% or p < 0.1, significant heterogeneity was considered present, and a random-effects model was applied; otherwise, a fixed-effects model was used (26). Sensitivity analyses were performed by excluding studies with high risk of bias or those with significant heterogeneity. Funnel plots were used to assess publication bias for the primary outcomes.

3 Results

3.1 Screening results

A total of 836 articles were initially identified, and after removing duplicates, 553 studies remained for title and abstract screening. After excluding studies that did not meet the inclusion criteria, 506 studies were discarded. The remaining 47 studies underwent full-text assessment, of which 2 were excluded due to unavailability of the full text. The remaining 45 studies were thoroughly evaluated against the inclusion and exclusion criteria, resulting in the inclusion of 16 RCTs for the meta-analysis (Figure 1).

Figure 1

PRISMA 2020 flow diagram for new systematic reviews.

3.2 Baseline characteristics

The 16 included RCTs involved a total of 2,017 patients, with 1,125 in the TEAS group and 892 in the control group. The average age of participants ranged from 40 to 60 years. The intervention primarily involved TEAS, with some studies combining other treatments, such as ondansetron or auricular acupressure. The control group received either conventional treatment or sham TEAS. The types of cancers included gastrointestinal tumors (6 studies), breast cancer (6 studies), lung cancer (2 studies), thyroid cancer (1 study), and cervical cancer (1 study). Geographically, 15 studies were conducted in China, while 1 study was from Turkey. The specific characteristics of the studies are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1

| Study | Country | Surgery type | Intervention | Sample size | Mean age (years) | Outcomes* | RoB |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gu 2018 (55) | China | LRG | Control | 60 | 58.80 ± 8.70 | 1,4 | Unclear |

| Short TEAS | 60 | 56.90 ± 9.30 | |||||

| Long TEAS | 60 | 60.20 ± 7.60 | |||||

| Jiang 2019 (38) | China | URT | Sham TEAS + Sham auricular acupressure | 31 | 47.00 ± 9.00 | 2,3,4 | Unclear |

| TEAS + auricular acupressure | 31 | 44.00 ± 11.00 | |||||

| Fu 2022 (36) | China | LRRC | Sham TEAS | 21 | 59.8 ± 10.55 | 2,3,4 | Unclear |

| TEAS | 25 | 62.0 ± 10.81 | |||||

| Zhang 2020 (56) | China | ECCS | Sham TEAS | 45 | 65.00 ± 11.00 | 1 | Unclear |

| TEAS | 45 | 64.00 ± 12.00 | |||||

| Chen 2021 (57) | China | CCS | Sham TEAS | 36 | 47.13 ± 5.24 | 1,4 | Unclear |

| TEAS | 36 | 45.36 ± 5.21 | |||||

| Yan 2025 (28) | China | UMRM | Sham TEAS | 68 | 48.00 ± 8.00 | 1,4 | High |

| TEAS | 70 | 48.00 ± 8.00 | |||||

| Jin 2020 (37) | China | RM | Sham TEAS | 31 | 50.90 ± 7.10 | 1,4 | High |

| TEAS | 30 | 48.20 ± 6.90 | |||||

| Ye 2024 (58) | China | GCS | Sham TEAS | 40 | 63.84 ± 8.50 | 4 | Unclear |

| TEAS | 40 | 62.92 ± 8.34 | |||||

| Ma 2023 (33) | China | RM | Control | 60 | 44.79 ± 4.91 | 1,4 | High |

| TEAS | 60 | 45.10 ± 4.96 | |||||

| Liu 2019 (59) | China | MRM | control + sham teas | 40 | 43.50 ± 5.10 | 1 | Unclear |

| ondansetron + sham teas | 40 | 42.70 ± 7.20 | |||||

| TEAS | 40 | 42.30 ± 6.50 | |||||

| TEAS + ondansetron | 40 | 41.20 ± 6.40 | |||||

| Lei 2024 (34) | China | VATS-RRLC | Control | 33 | 62.95 ± 5.03 | 1,4 | High |

| TEAS | 32 | 61.46 ± 2.47 | |||||

| Li 2023 (35) | China | RHCC | Control | 30 | 55.40 ± 10.20 | 1,4 | High |

| TAP | 30 | 54.80 ± 9.30 | |||||

| TEAS+TAP | 30 | 53.90 ± 9.60 | |||||

| Gu 2019 (29) | China | LRG | Sham TEAS | 59 | 56.67 ± 6.23 | 1,4 | Low |

| TEAS | 58 | 57.59 ± 7.32 | |||||

| Erden S 2022 (30) | Turkey | MRM | Control | 40 | 57.10 ± 10.88 | 2,4 | High |

| TEAS | 40 | 56.90 ± 10.20 | |||||

| Chen 2020 (31) | China | VATS-RRLC | Sham TEAS | 40 | 55.80 ± 3.20 | 2,3,4 | Low |

| TEAS | 40 | 56.00 ± 3.70 | |||||

| Lu 2021 (32) | China | RM | Sham TEAS | 188 | 48.20 ± 8.20 | 1,2,3,4 | High |

| single acupoint | 198 | 48.00 ± 9.10 | |||||

| combined acupoints | 190 | 48.20 ± 9.00 |

Characteristic of the included studies.

TEAS, transcutaneous electrical acupoint stimulation; TAP, Transversus Abdominis Plane block; LRG, Laparoscopic radical gastrectomy; URT, Unilateral Radical thyroidectomy; LRRCC, Laparoscopic radical resection for colorectal cancer; ECCS, Elective surgery for colorectal cancer; CCS, Colorectal cancer surgery; UMRM, Unilateral modified radical mastectomy for breast cancer; RM, Radical mastectomy; GCS, Gastric cancer surgery; MRM, Modified radical mastectomy for breast cancer; VATS-RRLC, Video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery radical resection for lung cancer; RHCC, Radical hysterectomy for cervical cancer; NR, not reported; *1: nausea and vomiting; 2: postoperative nausea; 3: postoperative vomiting; 4: Postoperative pain.

Table 2 summarizes the key characteristics of the TEAS interventions in the included studies, including the selected acupoints, stimulation duration, frequency, and current intensity. Commonly used acupoints included Neiguan (PC6), Zusanli (ST36), Hegu (LI4), and Sanyinjiao (SP6). Most studies initiated TEAS intervention 30 min before surgery, with some continuing during or after surgery. The electrical stimulation frequency was mostly in the form of sparse-dense waves, with the current intensity typically ranging from 2 to 30 mA. Most studies did not report any TEAS-related adverse events, though a few studies mentioned mild discomfort at the electrode site.

Table 2

| Study | Acupoints | Time point | Frequency | Adverse events | Device | Post-operative medication |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gu 2018 (55) | PC6, ST36 | short TEAS-throughout the procedure; longTEAS-1 h before the procedure to 30 min postoperatively;2d, 30 min/session, 3 times/d | 2/100 Hz; 8~12 mA; 0.2~0.6 ms | NR | HANS-LH402 (Beijing Pukang Pharmaceutical Technology Development Co. Ltd.) | PCIA |

| Jiang 2019 (38) | LI4, PC6 | 30 min before the procedure; throughout the procedure | 2/100 Hz; 6~12 mA | NR | HANS-200A (Batch No. 200110514089) | NR |

| Fu 2022 (36) | ST36, SP6 | 30 min before the procedure | 2/100 Hz; maximum tolerable level minus 1 mA | NR | HANS-200A (Nanjing Jisheng Medical Technology Co. Ltd. Nanjing, China) | PCIA |

| Zhang 2020 (56) | ST36, SP6, ST37 | 30 min after the procedure;3d, 30 min/session, 1 times/d | 2 Hz; 10~25 mA | NR | TEAS device (not specified) | NR |

| Chen 2021 (57) | PC6, ST36 | 30 min before surgery to 30 min after surgery;2d, 30 min/session; 3times/d | 2/100 Hz; 8~12 mA; 0.2 ~ 0.6 ms | NR | TEAS device (not specified) | NR |

| Yan 2025 (28) | PC6, ST36, CV17 | 30 min before the procedure;1d, 30 min/session, 1 times/d | 2/100 Hz; Maximally tolerated intensity | NR | SDZ-V electroacupuncture device | PCIA |

| Jin 2020 (37) | LI4, PC6, ST36, SP6 | 30 min before the procedure, throughout the procedure | 2/100 Hz; 6~9 mA | NR | HANS-200A (Nanjing Jisheng Medical Technology Co. Ltd. Nanjing, China) | PCIA |

| Ye 2024 (58) | LI4, PC6, ST36 | 1d before the procedure;7d, 30 min/session, every 12 h | 2/100 Hz; 8~12 mA; 0.2~0.6 ms | NR | KD-2B (Beijing Yaoyang Kangda Medical Instrument Co. Ltd. Beijing, China) | NR |

| Ma 2023 (33) | LI4, PC6, ST36 | 30 min before the procedure | 2/30 Hz; 6~10 mA | NR | Huatuo SDZ-V electroacupuncture device | PCIA |

| Liu 2019 (59) | ST36, PC6 | 30 min before the procedure | 2/10 Hz; Maximally tolerated intensity | NR | Huatuo SDZ-V (Suzhou Medical Appliance Factory Co. Ltd. Suzhou, China) | PCIA |

| Lei 2024 (34) | LI4, PC6, ST36 | throughout the procedure | 2/100 Hz; 30 mA | NR | TEAS device(not specified) | PCIA |

| Li 2023 (35) | ST36, SP6 | After the procedure | 2/10 Hz; Maximally tolerated intensity | NR | SDZ-V (Suzhou Medical Appliance Factory Co. Ltd. Suzhou, China) | PCIA |

| Gu 2019 (29) | ST36, PC6 | 30 min before the procedure to 30 min after surgery; postoperative 2d, 30 min/session, 3 times/d |

2/100 Hz; 5~30 mA | NR | HANS LH-202 Transcutaneous Electrical Acupoint Stimulation device | Analgesics (not specified) |

| Erden S 2022 (30) | NR | Twice postoperatively(20 min/session) | 85 Hz; 50~250 ms | NR | Dual-channel TENS device (Intelect) | NR |

| Chen 2020 (31) | LI4, PC6, SI3, TE6 | 30 min before the procedure; throughout the procedure; 6, 24 and 48 h after the procedure(30 min/session) | 2/100 Hz; 10–15 mA; 30 mA | NR | HANS-200A (Nanjing Jisheng Medical Technology Co. Ltd. Jiangsu, China) | sufentanil |

| Lu 2021 (32) | PC6, CV17 | 30 min before the procedure | 2/10 Hz | discomfort in the skin area attached to the electrodes | Hwato (Model SDZ-V, Suzhou Medical Appliance Factory, Suzhou, China) | Sufentanil, Parecoxib sodium 40 mg |

TEAS stimulation parameters.

Hz, hertz; h, hour; d, day; mA, milliampere; min, minute; ms, millisecond; NR, not reported; TEAS, transcutaneous electrical acupoint stimulation; PCIA, Patient-Controlled Intravenous Analgesia; PC6, Neiguan; CV17, Danzhong; LI4, Hegu; SI3, Houxi; SP6, Sanyinjiao; TE6, Zhigou; ST37, Shangjuxu; ST36 Zusa.

3.3 Risk of bias

In this study, the Cochrane Risk of Bias assessment tool was used to evaluate the risk of bias in the included RCTs (27). The results are shown in Figure 2. Most studies were classified as low risk for randomization process, completeness of outcome data, selective reporting, and other potential biases. However, there were differences in the risk of bias across some domains in the studies.

Figure 2

Risk of bias summary.

Regarding allocation concealment, only 5 RCTs explicitly reported the allocation concealment method and were rated as low risk (28–32), while the remaining studies did not report specific methods and were classified as “unclear risk.” In terms of performance bias, about 20 to 30% of studies were rated as high risk or unclear risk (30, 32–35). Given the nature of TEAS and other physical interventions, blinding of both participants and researchers was challenging in these trials, leading to potential bias.

For outcome assessment blinding, 6 RCTs reported blinding procedures, with only one study not specifying whether blinding was implemented (33). Concerning the completeness of outcome data, 5 studies had missing data or attrition, and were rated as unclear risk (28, 29, 32, 36, 37), while the remaining studies had complete data. The vast majority of studies were rated as low risk for selective reporting and other potential biases. Overall, 1 study was classified as low risk across all domains (31), 3 studies had only 1 domain with unclear or high risk (28, 30, 38), and the remaining studies were of acceptable overall quality.

Sensitivity analyses were performed by excluding studies with high or unclear risk of bias to assess their impact on the overall results. The analysis showed that excluding individual studies did not change the direction of the combined effect, indicating the robustness of the results. Publication bias was assessed using funnel plots. As shown in Figure 3, the funnel plot distribution was nearly symmetrical, suggesting a low likelihood of significant publication bias.

Figure 3

![Funnel plot displaying publication bias with study effect size on the x-axis labeled RR and standard error on the y-axis labeled SE(log[RR]), showing individual study points clustered symmetrically within blue dashed triangular boundaries.](https://www.frontiersin.org/files/Articles/1772210/xml-images/fmed-13-1772210-g003.webp)

Funnel plot of PONV incidence.

3.4 Meta-analysis results

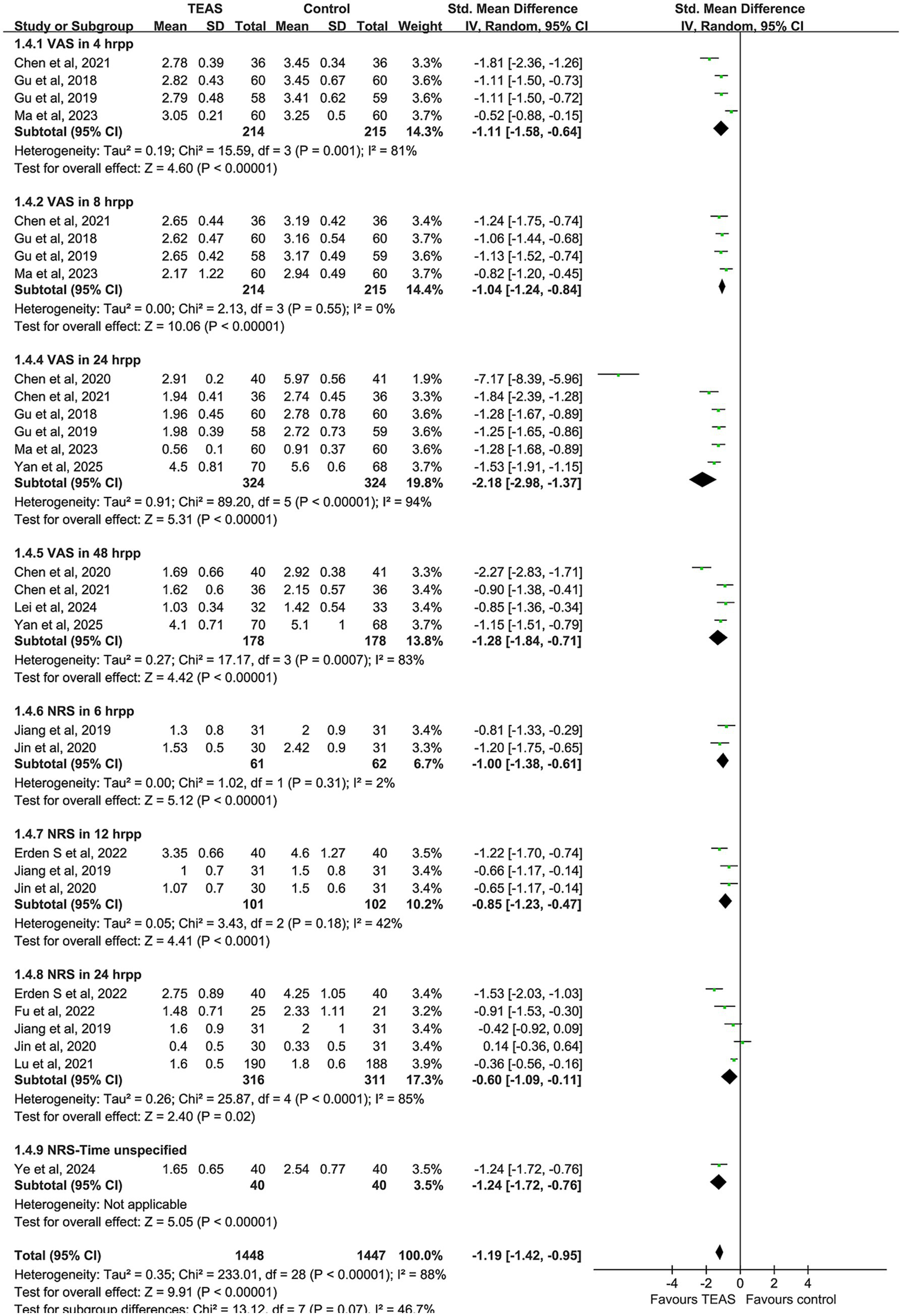

3.4.1 Postoperative pain

A total of 14 studies were included in the meta-analysis of postoperative pain, comprising 742 patients in the TEAS group and 737 in the control group. There was significant heterogeneity among the included studies (I2 = 88%, p < 0.00001), and therefore a random-effects model was used. The pooled results indicated that patients in the TEAS group experienced significantly reduced postoperative pain compared to those in the control group (SMD = −1.19, 95% CI [−1.42, −0.95], p < 0.00001).

Subgroup analyses based on different postoperative time points and pain assessment tools (VAS and NRS) were performed. The VAS results demonstrated that TEAS significantly reduced pain at 4 h (SMD = −1.11, 95% CI [−1.58, −0.64], p < 0.00001), 8 h (SMD = −1.04, 95% CI [−1.24, −0.84], p < 0.00001), 24 h (SMD = −2.18, 95% CI [−2.98, −1.37], p < 0.00001), and 48 h (SMD = −1.28, 95% CI [−1.84, −0.71], p < 0.00001) after surgery.

Regarding the NRS scores, TEAS was also effective in reducing pain at 6 h (SMD = −1.00, 95% CI [−1.38, −0.61], p < 0.00001), 12 h (SMD = −0.85, 95% CI [−1.23, −0.47], p < 0.00001), and 24 h (SMD = −0.60, 95% CI [−1.09, −0.11], p = 0.02), postoperatively (Figure 4).

Figure 4

Forest plot comparing the incidence of postoperative nausea and vomiting (PONV) between TEAS and control group.

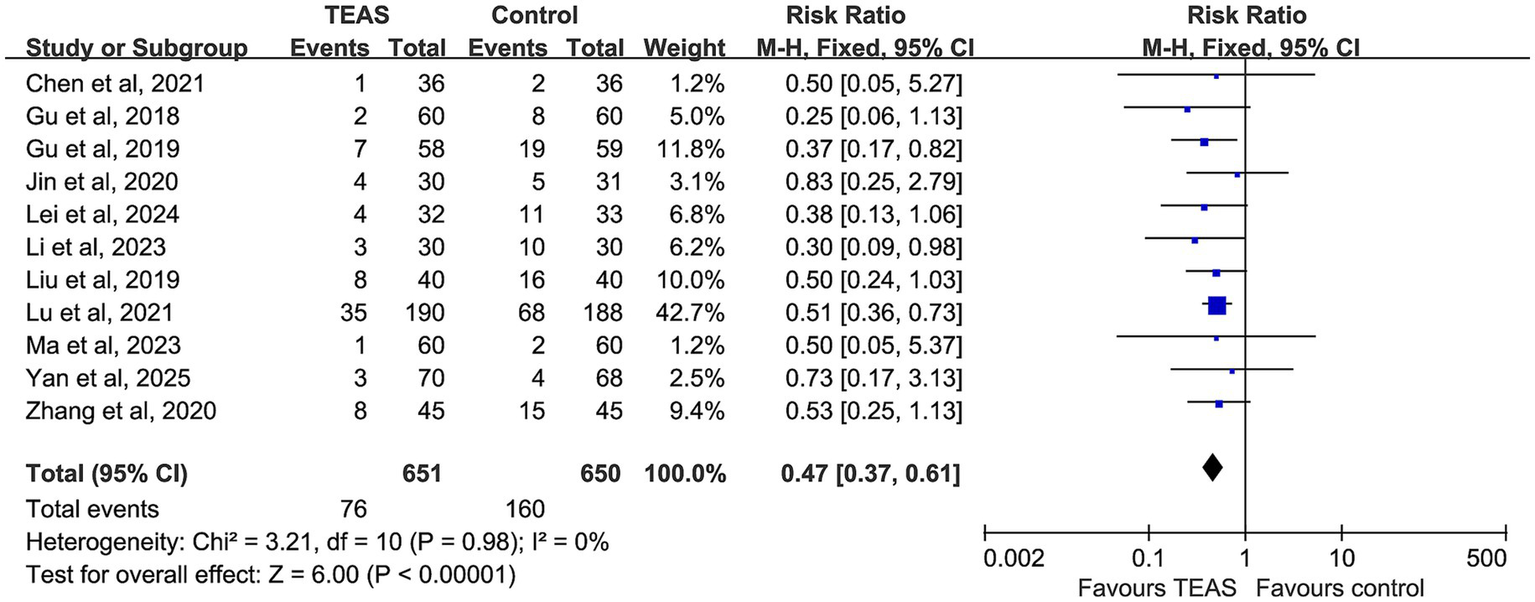

3.4.2 Incidence of postoperative nausea and vomiting

A total of 11 studies reported the incidence of PONV, involving 651 participants in the TEAS group and 650 in the control group. No evidence of heterogeneity was observed among studies (p = 0.98, I2 = 0%), and a fixed-effect model was applied. The pooled analysis revealed that TEAS significantly reduced the incidence of PONV compared with the control group (RR = 0.47, 95% CI: 0.37–0.61, p < 0.00001) (Figure 5).

Figure 5

Forest plot comparing the impact of TEAS group and control group on postoperative pain based on postoperative time and measurement tools.

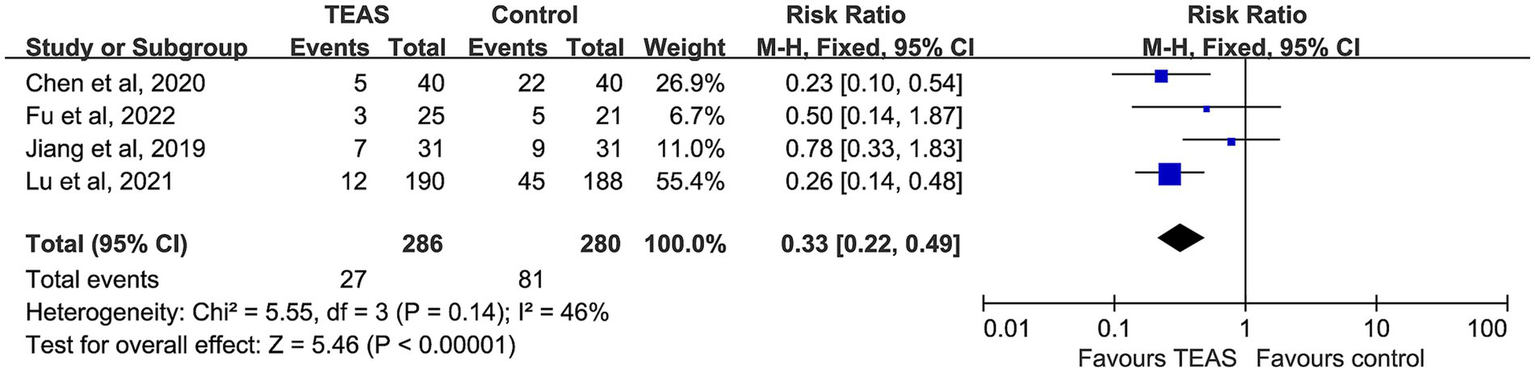

3.4.3 Incidence of postoperative nausea

Five studies reported the incidence of postoperative nausea. However, the study by Sevilay ERDEN (2022) assessed nausea using a scoring scale rather than actual event counts, and thus was excluded from quantitative synthesis. Ultimately, data from 286 patients in the TEAS group and 280 in the control group were analyzed. Moderate heterogeneity was present but not statistically significant (I2 = 46%, p = 0.14), and a fixed-effect model was used. The results indicated a significantly lower incidence of postoperative nausea in the TEAS group compared with the control group (RR = 0.33, 95% CI: 0.22–0.49, p < 0.00001) (Figure 6).

Figure 6

Forest plot comparing the incidence of postoperative nausea (PON) between TEAS and control group.

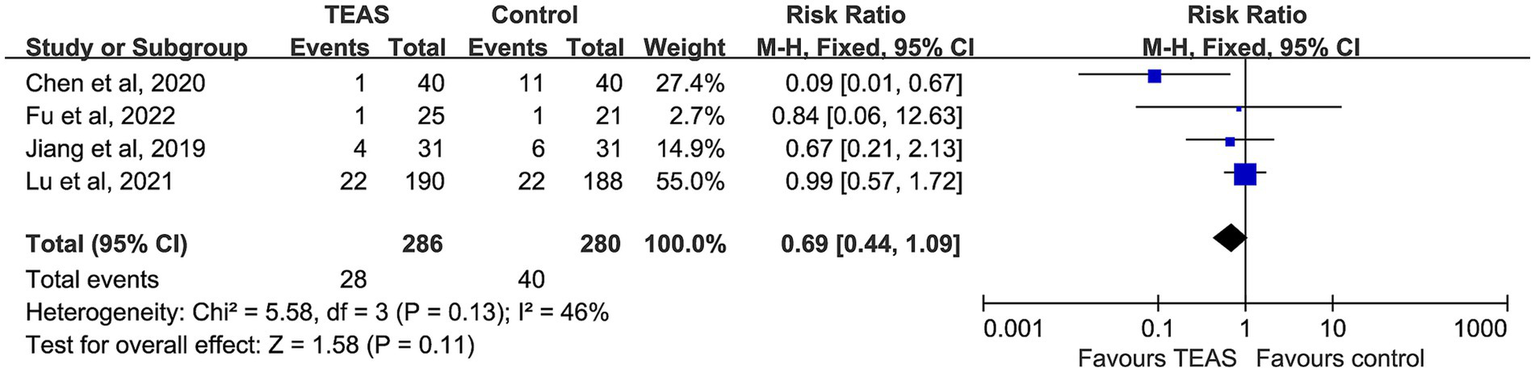

3.4.4 Incidence of postoperative vomiting

Four studies compared the incidence of postoperative vomiting, including 286 participants in the TEAS group and 280 in the control group. No significant heterogeneity was detected (I2 = 46%, p = 0.13), and a fixed-effect model was adopted. Although the TEAS group had a relatively lower incidence of vomiting, the difference was not statistically significant (RR = 0.69, 95% CI: 0.44–1.09, p = 0.11) (Figure 7).

Figure 7

Forest plot comparing the incidence of postoperative vomiting (POV) between TEAS and control group.

4 Discussion

This study included 16 RCTs involving cancer patients post-surgery. Significant heterogeneity was observed only in the postoperative pain outcome, and no apparent publication bias was detected. The meta-analysis demonstrates that TEAS significantly alleviates postoperative pain and reduces the incidence of PONV, showing high clinical potential. It can help reduce patient discomfort and lower the risk of postoperative complications.

Currently, postoperative pain and PONV in cancer patients are primarily managed with pharmacological treatments. Opioids such as morphine and fentanyl are commonly used for pain relief. While these drugs provide rapid pain relief, they are associated with adverse effects such as respiratory depression, tolerance, nausea, vomiting, and excessive sedation (9). For PONV, 5-HT₃ receptor antagonists like ondansetron are frequently used, but these medications can cause side effects such as headaches, constipation, and QT prolongation (10). Some cancer patients may have poor responses to pharmacological treatments or may have contraindications, which further complicates postoperative management. Compared to general surgical patients, cancer patients often have more extensive surgical trauma, as well as comorbidities such as malnutrition, anemia, and impaired liver and kidney function, leading to poor opioid tolerance and a higher risk of adverse reactions like constipation and respiratory depression (39, 40). Additionally, some patients may have a history of perioperative chemotherapy, which significantly increases the risk of recurrent PONV post-surgery (41), further highlighting the importance of non-pharmacological interventions.

In this context, TEAS, a non-pharmacological treatment combining traditional Chinese medicine meridian theory and modern electrical stimulation techniques, has gained attention for its non-invasive, cost-effective, easy-to-operate, and low-equipment and environmental requirements. It has gradually been applied in perioperative management (42). Administered by trained physicians or nurses at different stages (preoperative, intraoperative, or postoperative), TEAS helps alleviate postoperative pain and PONV without adding to the pharmacological burden. It effectively reduces opioid and antiemetic medication usage and related side effects, making it particularly valuable for cancer patients, a high-risk group. TEAS has the potential to become an essential component of postoperative pain and PONV management for cancer patients. Future studies could include outcomes related to medication dosage and opioid-related adverse events to provide a more comprehensive evaluation of TEAS in ERAS (Enhanced Recovery After Surgery) protocols for cancer patients during the perioperative period.

Previous systematic reviews on acupoint stimulation for PONV prevention have mostly focused on mixed surgical or anesthetic populations (43, 44). These studies mainly assess the overall incidence of PONV but lack a systematic exploration of the differences in PON and POV in cancer patients. In contrast, this study focused on cancer surgical patients and separately evaluated the effects of TEAS on postoperative pain, PON, and POV. These findings contribute to expanding the evidence base for the application of TEAS in perioperative oncology care.

4.1 Pain

This study demonstrates that TEAS significantly alleviates postoperative pain, which is consistent with previous research. Subgroup analysis indicated that VAS and NRS scores at different time points (4 h, 24 h, and 48 h postoperative) were significantly lower in the TEAS group compared to the control group, with the most significant effect observed at 24 h post-surgery. The effective pain relief not only helps reduce discomfort but also facilitates early mobilization and functional recovery of the patients.

Regarding acupoint selection, LI4 (Hegu) and ST36 (Zusanli) were the most commonly used acupoints for pain relief. Research has shown that stimulation of LI4 and ST36 can regulate pain transmission and perception by activating the hypothalamus-pituitary–adrenal axis and enhancing the release of endogenous opioid peptides. It also reduces pain sensitivity by downregulating TRPV1 and associated neuroinflammatory signals (45–47). Most studies used an alternating frequency of 2/100 Hz, combining the dual mechanisms of low-frequency stimulation to induce the release of encephalins and high-frequency stimulation to inhibit the release of substance P, which helps to enhance the analgesic effect (48). Regarding the timing of intervention, a preoperative start 30 min before surgery with continuation into the postoperative period was associated with better analgesic effects. This suggests that continuous electrical stimulation may help reduce the postoperative pain peak and opioid consumption, indicating that the timing of intervention could be a key factor influencing efficacy (49).

Postoperative pain in cancer patients is often accompanied by chronic inflammation and opioid tolerance. TEAS offers an advantage by reducing pain and decreasing opioid use through a non-pharmacological approach. This study exhibited high heterogeneity in postoperative pain outcomes, which is common in meta-analyses of pain-related outcomes. The sources of heterogeneity may include variations in TEAS stimulation parameters, acupoint selection, the use of adjunctive analgesic medications, different postoperative assessment time points, and the types of surgeries performed. However, the heterogeneity did not significantly affect the direction of the effect, as all studies indicated that TEAS had a positive impact on postoperative pain. Therefore, while this conclusion is meaningful, the effect size should be interpreted with caution in light of the observed heterogeneity.

4.2 Nausea and vomiting

The results of this study show that TEAS significantly reduces the incidence of PONV and PON in cancer patients, with low heterogeneity between studies. However, while there was a trend towards a reduction in POV, the difference did not reach statistical significance. This may be due to the different neuroregulatory pathways involved in PON and POV. Nausea primarily involves the cortical–limbic system and is a subjective experience. TEAS can suppress excessive gastrointestinal motility, regulate serum 5-HT levels, and modulate vagal nerve activity, which reduces nausea (50), while maintaining higher postoperative serum ghrelin levels to enhance gastrointestinal motility, thus reducing the incidence of PONV (51). In contrast, vomiting is a complex somatic reflex behavior coordinated by the brainstem and the vomiting center (52). The modulation of this reflex pathway by TEAS may not be as sensitive as its effect on nausea, resulting in limited efficacy. Controlling vomiting may require interventions that directly target the brainstem reflex mechanism, which warrants further investigation in future studies.

Differences in acupoint selection across studies may also influence POV outcomes. For example, Chen et al. successfully reduced postoperative vomiting incidence in lung cancer patients by stimulating LI4, PC6, SI3, and TE6, while Lu et al. using a combination of PC6 and CV17 did not observe significant improvements. This suggests that the choice of acupoints may play a role in the therapeutic outcomes. Additionally, the small sample sizes in some studies may limit the statistical power. Overall, TEAS was found to have more consistent efficacy in alleviating nausea.

The frequency of stimulation in the studies we included was primarily 2/100 Hz, but Liu et al. used a low-frequency 2/10 Hz. Both frequencies demonstrated some efficacy, though there is no established standard for frequency at this time. Notably, in studies involving laparoscopic surgery, TEAS significantly alleviated PONV, which may be related to the specific injury pattern and anesthesia management associated with this type of surgery. This suggests that future research should explore the impact of surgical techniques on TEAS efficacy.

While different cancer types may influence the baseline risk of PONV, no significant differences were found in the subgroup analysis, indicating that TEAS may offer consistent efficacy across different cancer types post-surgery. However, it should be noted that some subgroups had small sample sizes, and the results require further validation.

Safety and tolerability are important considerations for the clinical application of TEAS. Previous studies have shown that TEAS-related adverse events are generally limited to mild local skin reactions, such as irritation, redness, tingling, or itching, which may be more likely to occur in patients with sensitive skin or during prolonged use. These discomforts can be effectively minimized through appropriate selection of electrode materials, standardized electrode placement, adjustment of stimulation intensity, and regular assessment of skin condition, thereby improving patient adherence. Across the randomized controlled trials included in the present review, TEAS-related adverse events were infrequently reported. Only one patient in the study by Lu et al. (32) experienced mild local discomfort at the stimulation site, including itching and erythema, which resolved spontaneously without treatment interruption. Overall, current evidence indicates that TEAS-related discomfort is typically mild, transient, and self-limiting. Its favorable safety profile and non-invasive nature support TEAS as a feasible adjunctive option for postoperative symptom management, particularly in cancer patients with a high symptom burden.

Several limitations of the current study must be acknowledged. First, most of the included studies had small sample sizes, which may reduce the stability of the analysis. Second, there was significant heterogeneity in the postoperative pain outcomes, possibly due to differences in intervention parameters, assessment tools, and cancer types. Furthermore, 15 of the included studies were from China, which introduces regional limitations. This means that our findings primarily reflect the unique medical environment, clinical practices, and healthcare culture specific to China. The influence of traditional Chinese medicine, the proficiency of healthcare providers, and patients’ acceptance of treatments may differ substantially from those in other countries. Additionally, variations in surgical techniques and postoperative care protocols across countries could influence the effectiveness of TEAS in different regions. As a result, the generalizability of our conclusions is limited, and they are most applicable to regions with similar medical and cultural contexts. In addition, another important limitation is the lack of consideration for the combined use of TEAS with other traditional Chinese medicine (TCM) therapies in clinical practice. In actual clinical settings, TEAS is often used alongside TCM treatments such as topical herbal applications, herbal formulas, or acupoint compresses to enhance effectiveness. However, the studies included in this meta-analysis did not report data on such combinations, which may represent a potential confounding factor. Different herbal formulas and their interactions with TEAS could vary by region. Although literature suggests that TCM may enhance the effects of TEAS, this aspect remains underexplored (53, 54). Future research should investigate the combined effects of TEAS and TCM treatments, with multi-center, standardized research designs to assess their synergistic effects. This will provide a stronger evidence base for the broader application of TEAS in clinical practice. Although the study systematically searched major Chinese and English-language databases and supplemented searches in ClinicalTrials.gov and ChiCTR, no grey literature meeting the inclusion criteria was found, meaning some unpublished or ongoing studies may have been missed. Therefore, future studies should prioritize multicenter, large-scale randomized controlled trials with standardized TEAS protocols and outcome measures, conducted across diverse geographic regions and healthcare systems to improve generalizability. In addition, the potential synergistic effects of TEAS combined with traditional Chinese medicine therapies warrant further investigation using standardized study designs.

Nevertheless, the meta-analysis in this study provides strong support for the use of TEAS in postoperative pain and PONV management in cancer patients. The effectiveness of TEAS in reducing postoperative pain and overall PONV, particularly nausea, has been confirmed, and it demonstrates good safety and tolerability. Given the significant impact of pain and PONV on postoperative recovery and quality of life in cancer patients, TEAS, as a safe, non-invasive, and patient-compliant intervention, is particularly suitable for this population and holds promising potential for broader application. Future studies should further explore its efficacy across different cancer types and surgical procedures, optimize acupoint combinations and stimulation parameters, and provide a basis for the development of standardized treatment protocols.

5 Conclusion

In summary, TEAS is a safe, non-invasive, and easy-to-administer intervention that shows promising efficacy in postoperative pain and PONV management for cancer patients. The meta-analysis results indicate that TEAS significantly reduces pain scores at multiple postoperative time points and decreases the overall incidence of PONV, as well as postoperative nausea. These effects may reduce opioid analgesic use, thus improving postoperative recovery quality.

Although this study has limitations, including regional concentration of research and inconsistent intervention protocols, the overall evidence supports the use of TEAS as a beneficial adjunctive strategy for postoperative pain and PONV management in cancer patients. Future multicenter, large-scale, rigorously designed clinical trials are needed to further validate its impact on postoperative recovery, long-term survival, and quality of life. Additionally, efforts should focus on standardizing TEAS intervention parameters and protocols to better serve clinical practice.

Statements

Data availability statement

The data analyzed in this study is subject to the following licenses/restrictions: the dataset used in this meta-analysis was extracted from published studies. No individual participant data were collected. The extracted study-level dataset and analysis files are not publicly available at this stage, but can be provided by the corresponding author upon reasonable request for academic purposes. Requests to access these datasets should be directed to CT, tc2023tc@163.com.

Author contributions

JC: Conceptualization, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. JY: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Visualization. RL: Data curation, Methodology, Project administration, Writing – original draft. ZW: Resources, Software, Writing – original draft. CL: Resources, Writing – original draft. CT: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Methodology, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declared that financial support was received for this work and/or its publication. This research was funded by the Tianfu Jincheng Laboratory (Frontier Medicine Center) Achievement Transformation Project, grant number 2025ZH043; the High-Level Talent Introduction Program of the Sichuan Provincial Department of Science and Technology (“Haiju Plan”), grant number 2024JDHJ0046; the Sichuan Provincial Health Commission Science and Technology Project, grant number 24CGZH01; and the Tianfu Jincheng Laboratory (Future Medicine City) 2024 First Batch “Unveiling and Commanding” Science and Technology Project, grant number TFJC-2024-JB002. The funding was used solely to cover the APC.

Conflict of interest

The author(s) declared that this work was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declared that Generative AI was not used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fmed.2026.1772210/full#supplementary-material

References

1.

Rüsch D Eberhart LHJ Wallenborn J Kranke P . Nausea and vomiting after surgery under general anesthesia: an evidence-based review concerning risk assessment, prevention, and treatment. Dtsch Arztebl Int. (2010) 107:733–41. doi: 10.3238/arztebl.2010.0733,

2.

Gordon DB de Leon-Casasola OA Wu CL Sluka KA Brennan TJ Chou R . Research gaps in practice guidelines for acute postoperative pain Management in Adults: findings from a review of the evidence for an American pain society clinical practice guideline. J Pain. (2016) 17:158–66. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2015.10.023,

3.

Gan TJ Belani KG Bergese S Chung F Diemunsch P Habib AS et al . Fourth consensus guidelines for the Management of Postoperative Nausea and Vomiting. Anesth Analg. (2020) 131:411–48. doi: 10.1213/ANE.0000000000004833,

4.

Institute of Medicine . Relieving pain in America. Washington, DC: National Academies Press (2011).

5.

Gan TJ Habib AS Miller TE White W Apfelbaum JL . Incidence, patient satisfaction, and perceptions of post-surgical pain: results from a US national survey. Curr Med Res Opin. (2014) 30:149–60. doi: 10.1185/03007995.2013.860019,

6.

Wu CL Raja SN . Treatment of acute postoperative pain. Lancet. (2011) 377:2215–25. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60245-6,

7.

Siegel RL Giaquinto AN Jemal A . Cancer statistics. CA Cancer J Clin. (2024) 74:12–49. doi: 10.3322/caac.21820,

8.

Oderda GM Said Q Evans RS Stoddard GJ Lloyd J Jackson K et al . Opioid-related adverse drug events in surgical hospitalizations: impact on costs and length of stay. Ann Pharmacother. (2007) 41:400–6. doi: 10.1345/aph.1H386,

9.

Gan TJ . Poorly controlled postoperative pain: prevalence, consequences, and prevention. J Pain Res. (2017) 10:2287–98. doi: 10.2147/JPR.S144066,

10.

Cao X White PF Ma H . An update on the management of postoperative nausea and vomiting. J Anesth. (2017) 31:617–26. doi: 10.1007/s00540-017-2363-x,

11.

Kovac AL . Comparative pharmacology and guide to the use of the serotonin 5-HT3 receptor antagonists for postoperative nausea and vomiting. Drugs. (2016) 76:1719–35. doi: 10.1007/s40265-016-0663-3,

12.

Li X Kou Z Liu R Zhou Z Mei J Yan W . Transcutaneous electrical Acupoint stimulation improves postoperative nutrition and promotes early recovery of gastrointestinal function in patients with colorectal Cancer. Comb Chem High Throughput Screen. (2025) 28:64–73. doi: 10.2174/0113862073255619231102112544,

13.

Liu J Zhang K Zhang Y Ji F Shi H Lou Y et al . Perioperative transcutaneous electrical Acupoint stimulation reduces postoperative pain in patients undergoing Thoracoscopic surgery: a randomized controlled trial. Pain Res Manag. (2024) 2024:5365456. doi: 10.1155/2024/5365456,

14.

Viderman D Nabidollayeva F Aubakirova M Sadir N Tapinova K Tankacheyev R et al . The impact of transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (TENS) on acute pain and other postoperative outcomes: a systematic review with Meta-analysis. J Clin Med. (2024) 13:427. doi: 10.3390/jcm13020427,

15.

Wang D Shi H Yang Z Liu W Qi L Dong C et al . Efficacy and safety of transcutaneous electrical Acupoint stimulation for postoperative pain: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Pain Res Manag. (2022) 2022:1–10. doi: 10.1155/2022/7570533,

16.

Zhang M Zhang H Li P Li J . Effect of transcutaneous electrical acupoint stimulation on the quality of postoperative recovery: a meta-analysis. BMC Anesthesiol. (2024) 24:104. doi: 10.1186/s12871-024-02483-z,

17.

Wu C Deng Z Zhu Y Li Y Chen Y Wang L et al . Transcutaneous electrical acupoint stimulation accelerates gastrointestinal function recovery after abdominal surgery: a systemic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Int J Surg. (2025) 111:8592–603. doi: 10.1097/JS9.0000000000002946,

18.

Liu Y Chen Z Zhang Z Hu Q Wang J Cao R et al . Can transcutaneous electrical acupoint stimulation prevent postoperative nausea and vomiting?Complement Ther Med. (2025) 95:103294. doi: 10.1016/j.ctim.2025.103294,

19.

Arya S Kaji AH Boermeester MA . PRISMA reporting guidelines for Meta-analyses and systematic reviews. JAMA Surg. (2021) 156:789–90. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2021.0546,

20.

Rethlefsen ML Kirtley S Waffenschmidt S Ayala AP Moher D Page MJ et al . PRISMA-S: an extension to the PRISMA statement for reporting literature searches in systematic reviews. Syst Rev. (2021) 10:39. doi: 10.1186/s13643-020-01542-z,

21.

Page MJ McKenzie JE Bossuyt PM Boutron I Hoffmann TC Mulrow CD et al . The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ. (2021) 372:n71. doi: 10.1136/bmj.n71,

22.

Cumpston M Li T Page MJ Chandler J Welch VA Higgins JP et al . Updated guidance for trusted systematic reviews: a new edition of the Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. (2019) 10:ED000142. doi: 10.1002/14651858.ED000142,

23.

Ferreira-Valente MA Pais-Ribeiro JL Jensen MP . Validity of four pain intensity rating scales. Pain. (2011) 152:2399–404. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2011.07.005,

24.

Higgins JPT Thomas J Chandler J Cumpston M Li T Page MJ et al Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions. Version 6.5 (updated august 2024). Cochrane; (2024). Available online at: www.cochrane.org/handbook (Accessed January 31, 2026).

25.

Deeks JJ Higgins JPT Altman DG McKenzie JE Veroniki AA . ".Chapter 10: chapter 10: Analysing data and undertaking meta-analyses [last updated November 2024]" In: HigginsJPTThomasJChandlerJCumpstonMLiTPageMJet al, editors. Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions version 6.5. London: Cochrane (2024)

26.

Migliavaca CB Stein C Colpani V Barker TH Ziegelmann PK Munn Z et al . Prevalence estimates reviews-systematic review methodology group (PERSyst). Meta-analysis of prevalence: I2 statistic and how to deal with heterogeneity. Res Synth Methods. (2022) 13:363–7. doi: 10.1002/jrsm.1547,

27.

Higgins JPT Altman DG Gøtzsche PC Jüni P Moher D Oxman AD et al . The Cochrane collaboration’s tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ. (2011) 343:d5928. doi: 10.1136/bmj.d5928,

28.

Yan L Sun B Zhou M Zhang Y Gao F Zhao Q et al . Effect of transcutaneous electrical acupoint stimulation on postoperative pain in patients undergoing modified radical mastectomy for breast cancer. Zhongguo Zhen Jiu. (2025) 45:162–6. doi: 10.13703/j.0255-2930.20240206-k0002,

29.

Gu S Lang H Gan J Zheng Z Zhao F Tu Q . Effect of transcutaneous electrical acupoint stimulation on gastrointestinal function recovery after laparoscopic radical gastrectomy – a randomized controlled trial. Eur J Integr Med. (2019) 26:11–7. doi: 10.1016/j.eujim.2019.01.001

30.

Erden S Yurtseven Ş Demir SG Arslan S Arslan UE Dalcı K . Effects of transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation on mastectomy pain, patient satisfaction, and patient outcomes. J Perianesth Nurs. (2022) 37:485–92. doi: 10.1016/j.jopan.2021.08.017,

31.

Chen J Zhang Y Li X Wan Y Ji X Wang W et al . Efficacy of transcutaneous electrical acupoint stimulation combined with general anesthesia for sedation and postoperative analgesia in minimally invasive lung cancer surgery: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Thorac Cancer. (2020) 11:928–34. doi: 10.1111/1759-7714.13343,

32.

Lu Z Wang Q Sun X Zhang W Min S Zhang J et al . Transcutaneous electrical acupoint stimulation before surgery reduces chronic pain after mastectomy: a randomized clinical trial. J Clin Anesth. (2021) 74:110453. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinane.2021.110453,

33.

Ma Y Zhao R Yu S Meng J Chen K Ma Q . Anesthesia effect of thoracic paravertebral nerve block guided by ultrasound and percutaneous acupoint electrical stimulation for breast cancer radical surgery. J Xinjiang Med Univ. (2023) 46:957–60. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1009-5551.2023.07.018

34.

Lei J Cao H Cui Y Xia M . Application of percutaneous acupoint electrical stimulation combined with ultrasound-guided thoracic paravertebral nerve block in thoracoscopic radical surgery for lung cancer. J Hubei Univ Trad Chin Med. (2024) 26:87–9. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1008-987x.2024.04.24

35.

Li G Rao JZ . Effect of transcutaneous electrical acupoint stimulation combined with transversus abdominis plane block on analgesia and rehabilitation after radical resection of cervical carcinoma. Chin J Mod Med. (2023) 61:27–30. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1673-9701.2023.13.007

36.

Fu HF Zhao ZF Du WW Wang JL Jia DB . Effect of transcutaneous electrical acupoint stimulation on pain and enhanced recovery after laparoscopic radical resection of colorectal cancer. Chin J Mod Med. (2022) 60:15–8.

37.

Jin WJ Mo YC Jiang Q Jin D Dai OX Pan W et al . Effect of transcutaneous electrical acupoint stimulation on the postoperative recovery quality and long-term survival quality in breast cancer patients undergoing radical mastectomy. Chin J Integr Tradit West Med. (2020) 40:1315–21. doi: 10.7661/j.cjim.20201012.192

38.

Jiang Q Mo Y Jin D Jin W Pan Y Wang Y et al . Effect of acupoint stimulation on the quality of recovery in patients with radical thyroidectomy under the concept of enhanced recovery after surgery: a randomized controlled trial. Chin Acupunct Moxibustion. (2019) 39:1289–93. doi: 10.13703/j.0255-2930.2019.12.009

39.

Mesía R Virizuela Echaburu JA Gómez J Sauri T Serrano G Pujol E . Opioid-induced constipation in oncological patients: new strategies of management. Curr Treat Options in Oncol. (2019) 20:91. doi: 10.1007/s11864-019-0686-6,

40.

Bossi P De Luca R Ciani O D’Angelo E Caccialanza R . Malnutrition management in oncology: an expert view on controversial issues and future perspectives. Front Oncol. (2022) 12:910770. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2022.910770,

41.

Grigio TR Furuya TK Slullitel A Murillo Carrasco AG Uno M Alves MJF et al . Clinical, ethnic and genetic risk factors associated with postoperative nausea and vomiting in patients undergoing cancer surgery: a case-control study. Am J Transl Res. (2025) 17:3235–46. doi: 10.62347/DGRM3907,

42.

Huang L Pan Y Chen S Zhang M Zhuang X Jin S et al . Prevention of propofol injection-related pain using pretreatment transcutaneous electrical acupoint stimulation. Turk J Med Sci. (2017) 47:1267–76. doi: 10.3906/sag-1611-35,

43.

Chen J Tu Q Miao S Zhou Z Hu S . Transcutaneous electrical acupoint stimulation for preventing postoperative nausea and vomiting after general anesthesia: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Int J Surg. (2020) 73:57–64. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2019.10.036,

44.

Hao LN Hou T Li J Kang F Yin GB . Effect of transcutaneous electrical acupoint stimulation on postoperative nausea and vomiting in patients undergoing craniotomy. Chin J Clin Health Care. (2020) 23:672–5. doi: 10.3969/J.issn.1672-6790.2020.05.023

45.

Wang L An J Song S Mei M Li W Ding F et al . Electroacupuncture preserves intestinal barrier integrity through modulating the gut microbiota in DSS-induced chronic colitis. Life Sci. (2020) 261:118473. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2020.118473,

46.

Lin Y-W Chou AIW Su H Su K-P . Transient receptor potential V1 (TRPV1) modulates the therapeutic effects for comorbidity of pain and depression: the common molecular implication for electroacupuncture and omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids. Brain Behav Immun. (2020) 89:604–14. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2020.06.033,

47.

Fu T Li J . Mechanisms and clinical applications of transcutaneous electrical acupoint stimulation in improving postoperative gastrointestinal dysfunction: a review. J Clin Anesthesiol. (2023) 39:528–31. doi: 10.12089/jca.2023.05.016

48.

Chen P Xu H Zhang R Tian X . Dose-effect relationship between electroacupuncture with different parameters and the regulation of endogenous opioid peptide system. World J Acupunct Moxibustion. (2024) 34:9–15. doi: 10.1016/j.wjam.2023.06.003

49.

Lee A Chan SKC Fan LTY . Stimulation of the wrist acupuncture point PC6 for preventing postoperative nausea and vomiting. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. (2015) 2016:CD003281. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD003281.pub4,

50.

Liu YL Wang MS Li QJ Wang L Li JZ . Transcutaneous electrical acupoint stimulation for nausea and vomiting after cesarean section and its effect on plasma 5-HT levels. Chinese Acupunct Moxibustion. (2015) 35:1039–43. doi: 10.13703/j.0255-2930.2015.10.017.

51.

Li JL Wang XJ Rong JF . Effects of transcutaneous electrical acupoint stimulation with different acupoint combinations on postoperative nausea and vomiting and serum motilin secretion in patients undergoing laparoscopic surgery. Acupunct Res (2020) 45:920–923, 928. doi:10.13702/j.1000-0607.200060,

52.

Zhong W Shahbaz O Teskey G Beever A Kachour N Venketaraman V et al . Mechanisms of nausea and vomiting: current knowledge and recent advances in intracellular emetic signaling systems. Int J Mol Sci. (2021) 22:5797. doi: 10.3390/ijms22115797,

53.

Jiang XY Chen J Miao MR Chen YN Sun JY et al . Transcutaneous electrical acupoint stimulation for preventing postoperative nausea and vomiting after laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Chin J Anesthesiol. (2025) 41:1065–9. doi: 10.12089/jca.2025.10.010

54.

Chen YL Cheng W Wang SY Wei YF Liang PW Xiao LW et al . Clinical observation on early functional rehabilitation after total knee arthroplasty by transcutaneous electrical acupoint stimulation combined with Chinese ointment rubbing. J Tianjin Univ Tradit Chin Med. (2021) 40:739–43. doi: 10.11656/j.issn.1673-9043.2021.06.14

55.

Gu SH Gan JH Lang HB . Comparison of analgesic effect and gastrointestinal function recovery after laparoscopic radical gastrectomy with different TEAS methods. J Fujian Med Univ. (2018) 52:125–9.

56.

Zhang HL Hao JJ Bai YB YW Lu YQ . Effect of transcutaneous electrical stimulation on postoperative intestinal function in patients with colorectal cancer. J Mod Oncol. (2020) 28:611–4. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1672-4992.2020.04.020

57.

Chen J Fang YL Lan YY . Effect of transcutaneous acupoint electrical stimulation on postoperative intestinal function in patients with colorectal cancer. Chin Foreign Med Res. (2021) 19:22–4. doi: 10.14033/j.cnki.cfmr.2021.06.009

58.

Ye ZX Shi PS Zhang SH Luo DS . Effect of percutaneous point electrical stimulation on pain and gastrointestinal peristalsis function in patients after surgery for gastric cancer. New Chin Med. (2024) 56:160–4. doi: 10.13457/j.cnki.jncm.2024.08.027

59.

Liu Q Zhang YQ Yang ZL Zhang XQ . Effect of transcutaneous acupoint electrical stimulation combined with ondansetron on postoperative nausea and vomiting after modified radical mastectomy for breast cancer. Herald of Medicine. (2019) 38:747–50. doi: 10.3870/j.issn.1004-0781.2019.06.013

Summary

Keywords

cancer, meta-analysis, PONV, postoperative pain, systematic review, transcutaneous electrical acupoint stimulation (TEAS)

Citation

Chu J, You J, Li R, Wu Z, Liu C and Tian C (2026) Effectiveness of transcutaneous electrical acupoint stimulation for postoperative nausea, vomiting and pain in cancer patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Front. Med. 13:1772210. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2026.1772210

Received

20 December 2025

Revised

31 January 2026

Accepted

02 February 2026

Published

13 February 2026

Volume

13 - 2026

Edited by

Yangzi Zhu, Xuzhou Central Hospital, China

Reviewed by

Yerkin G. Abdildin, Nazarbayev University, Kazakhstan

Yufan Chen, Fuzhou Second General Hospital, China

Updates

Copyright

© 2026 Chu, You, Li, Wu, Liu and Tian.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Chao Tian, hxtc2000@163.com

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.