Abstract

Objective:

Evidence regarding the impact of annual hospital sepsis case volume on clinical outcomes in patients with sepsis remains controversial. This study aimed to conduct a meta-analysis to evaluate the potential association between annual sepsis case volume and mortality among patients with sepsis.

Methods:

A comprehensive electronic search was performed in PubMed, Web of Science, Embase, and Cochrane Library databases. Mean differences (MDs) or odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were calculated using Review Manager 5.3.

Results:

A total of 4,408,416 patients from 18 studies were included in this meta-analysis, comprising 1,828,689 patients treated in high-volume hospitals and 2,579,727 patients treated in low-volume hospitals. Compared with low-volume hospitals, treatment in high-volume hospitals was associated with significantly lower in-hospital mortality [OR = 0.90 (95% CI: 0.87–0.93, P < 0.00001)], ICU mortality [OR = 0.93 (95% CI: 0.91–0.94, P < 0.00001)], and early mortality [OR = 0.81 (95% CI: 0.76–0.87, P < 0.00001)], as well as a significantly shorter ICU length of stay [MD = −0.11 days (95% CI: −0.22 to −0.01, P = 0.04)]. However, no significant difference was observed in hospital length of stay between high- and low-volume hospitals.

Conclusions:

Hospitals with a high annual sepsis case volume are associated with reduced mortality among patients with sepsis. Future studies are warranted to further define clinically meaningful thresholds for high-volume hospitals.

1 Introduction

Sepsis has become one of the leading causes of in-hospital mortality worldwide. In the United States alone, sepsis accounts for approximately 19 million hospitalizations and more than 5 million deaths annually (1). It is estimated that sepsis imposes an economic burden of nearly USD 24 billion on the U.S. healthcare system each year (2). Consequently, effective strategies to reduce the clinical and economic burden of sepsis are urgently needed. Early identification, timely treatment, and optimization of care processes are widely recognized as key determinants of sepsis outcomes (2).

High-volume centers generally possess greater clinical experience and more abundant medical resources, which may facilitate timely evaluation and implementation of effective treatments. Therefore, treatment in high-volume hospitals may confer potential survival benefits for patients with sepsis (3–5). However, the association between hospital volume and sepsis outcomes remains controversial. Recently, a study by Ohki et al. (6) involving 934 patients with sepsis reported improved survival outcomes in high-volume centers compared with low-volume centers. In addition, Kahn et al. (7) estimated that routinely transferring patients from low-volume hospitals to high-volume hospitals across eight U.S. states could potentially save approximately 4,720 lives per year. In contrast, a study by Naar et al. (8) found no significant association between hospital volume and in-hospital mortality among patients with sepsis.

Given these conflicting findings, we systematically collected the currently available evidence and conducted a meta-analysis to investigate the association between hospital sepsis case volume and mortality outcomes in patients with sepsis.

2 Methods

2.1 Search strategy

This review was conducted in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines. The study protocol was registered in PROSPERO (CRD420261289937). PubMed, Web of Science, Embase, and the Cochrane Library were systematically searched from database inception to October 20, 2025. The complete search strategy is presented in Table 1. In addition, the reference lists of eligible studies were manually screened to identify potentially relevant articles. No language restrictions were applied.

Table 1

| Database | Search term (published up to October 20, 2025) | Number |

|---|---|---|

| PubMed | (centrali*[Title/Abstract] OR hospital volume*[Title/Abstract] OR center volume*[Title/Abstract] OR center volume*[Title/Abstract] OR low volume*[Title/Abstract] OR lower volume*[Title/Abstract] OR lowest volume*[Title/Abstract] OR high volume*[Title/Abstract] OR higher volume*[Title/Abstract] OR highest volume*[Title/Abstract] OR medium volume*[Title/Abstract] OR mid volume*[Title/Abstract] OR middle volume*[Title/Abstract] OR minimum volume*[Title/Abstract] OR volume outcome*[Title/Abstract] OR surgical volume*[Title/Abstract] OR surgeon volume*[Title/Abstract] OR surgeon's volume*[Title/Abstract] OR volume cost*[Title/Abstract] OR case volume*[Title/Abstract] OR caseload volume*[Title/Abstract] OR patient volume*[Title/Abstract] OR procedure volume*[Title/Abstract] OR procedural volume*[Title/Abstract] OR volume standard*[Title/Abstract]) AND (sepsis[Title/Abstract] OR Pyemia [Title/Abstract] OR Pyohemia[Title/Abstract] OR septicemia[Title/Abstract] OR septic[Title/Abstract]) |

981 |

| Embase | (centrali* OR hospital volume* OR center volume* OR center volume* OR low volume* OR lower volume* OR lowest volume* OR high volume* OR higher volume* OR highest volume* OR medium volume* OR mid volume* OR middle volume* OR minimum volume* OR volume outcome* OR surgical volume* OR surgeon volume* OR surgeon's volume* OR volume cost* OR case volume* OR caseload volume* OR patient volume* OR procedure volume* OR procedural volume* OR volume standard*).ab,kw,ti. AND (sepsis OR Pyemia OR Pyohemia OR septicemia OR septic).ab,kw,ti. |

1,972 |

| Cochrane library trials | ((centrali* OR hospital volume* OR center volume* OR center volume* OR low volume* OR lower volume* OR lowest volume* OR high volume* OR higher volume* OR highest volume* OR medium volume* OR mid volume* OR middle volume* OR minimum volume* OR volume outcome* OR surgical volume* OR surgeon volume* OR surgeon's volume* OR volume cost* OR case volume* OR caseload volume* OR patient volume* OR procedure volume* OR procedural volume* OR volume standard*):ti,ab,kw) AND ((sepsis OR Pyemia OR Pyohemia OR septicemia OR septic):ti,ab,kw) |

1,690 |

| Web of science | (TS=(centrali* OR hospital volume* OR center volume* OR center volume* OR low volume* OR lower volume* OR lowest volume* OR high volume* OR higher volume* OR highest volume* OR medium volume* OR mid volume* OR middle volume* OR minimum volume* OR volume outcome* OR surgical volume* OR surgeon volume* OR surgeon's volume* OR volume cost* OR case volume* OR caseload volume* OR patient volume* OR procedure volume* OR procedural volume* OR volume standard*)) AND (TS=(sepsis OR Pyemia OR Pyohemia OR septicemia OR septic)) |

484 |

Electronic search strategy.

2.2 Study selection

Studies were eligible for inclusion if they met the following criteria: (1) Population: patients diagnosed with sepsis, severe sepsis, or septic shock; (2) Intervention: treatment in hospitals with a high annual sepsis case volume (high-volume hospitals); (3) Comparison: treatment in hospitals with a low annual sepsis case volume (low-volume hospitals). Hospital sepsis case volume was defined as the annual number of sepsis cases treated in the hospital during the year of patient admission; (4) Outcomes: the primary outcome was in-hospital mortality. Secondary outcomes included ICU mortality, early mortality, ICU length of stay, and hospital length of stay. Early mortality was defined as death within 2 days of admission; (5) Study type: randomized controlled trials, cohort studies or case-control studies.

Exclusion criteria were as follows: case reports, conference abstracts, animal studies, studies without relevant outcome indicators, and letters.

2.3 Data extraction

Data were independently extracted from all eligible studies by two authors (Jiaan Chen and Fan Zhang) using a standardized data extraction form. Disagreements were resolved through discussion with a third independent author (Guangjun Jin). Extracted data included author name, year of publication, sepsis definition, study design, country, study population (sample size and volume category), and outcome data (in-hospital mortality, ICU mortality, early mortality, ICU length of stay, and hospital length of stay). When required data were unavailable, corresponding authors were contacted for additional information.

2.4 Quality assessment

The quality assessment was conducted independently by two authors (Jiaan Chen and Fan Zhang) using the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS), which assigns a score on a nine-point scale. A score of ≥7 indicates high quality, and scores of 5–6 indicate moderate quality. Any discrepancies were resolved by a third author (Guangjun Jin).

2.5 Statistical analysis

Meta-analyses were performed using Review Manager (RevMan) version 5.3 (The Nordic Cochrane Center, The Cochrane Collaboration, Copenhagen, Denmark) and Stata version 14. Odds ratios (ORs) with corresponding 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were calculated for categorical outcomes (in-hospital mortality, ICU mortality, and early mortality), and mean differences (MDs) were calculated for continuous outcomes (ICU length of stay and hospital length of stay). Statistical heterogeneity was assessed using the Cochran Q test and the I2 statistic. A random-effects model was applied when I2 > 50%; otherwise, a fixed-effects model was used (9). Subgroup analyses were performed based on patient age and sepsis definition era (pre-2016 vs. post-2016). Sensitivity analyses were conducted using a one-study removal approach. Publication bias was assessed using funnel plots and Egger's test when more than 10 studies were available. A P value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

3 Results

3.1 Literature retrieval

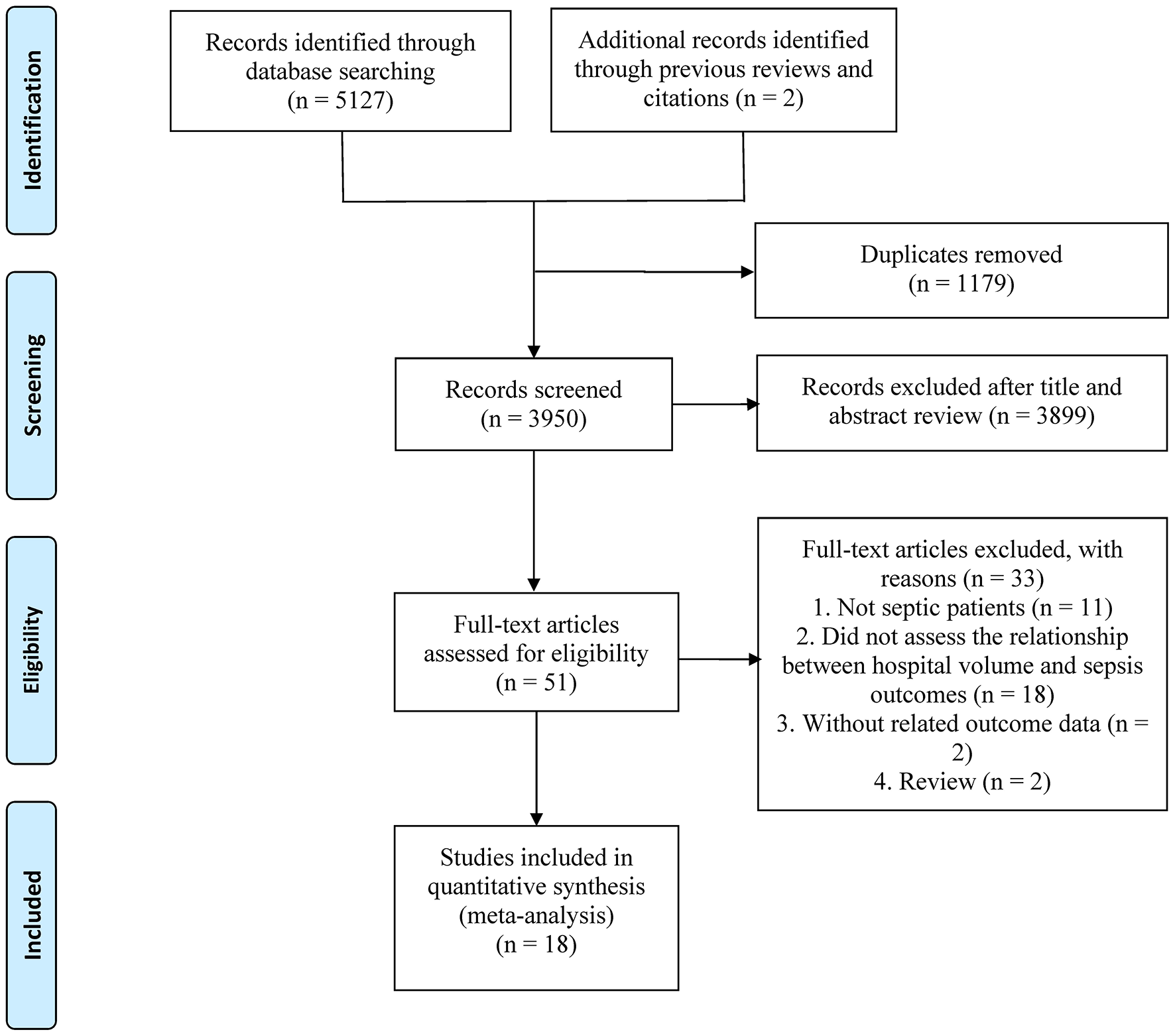

The initial database search identified 5,129 records (Figure 1), of which 1,179 were duplicates. After reviewing titles and abstracts, 3,899 papers were excluded, and the full texts of the remaining 51 studies were evaluated. Finally, 18 eligible studies (4–6, 8, 10–23) were enrolled in this study.

Figure 1

The PRISMA flowchart.

3.2 Study characteristics and quality assessment

The included studies were published between 2005 and 2025 and involved a total of 4,408,416 patients (high-volume hospitals: 1,828,689 patients; low-volume hospitals: 2,579,727 patients). Sample sizes ranged from 934 to 1,213,219 patients. All 18 studies were retrospective in design. The study populations were primarily drawn from the United States, France, China, Japan, and the United Kingdom. All studies were rated as moderate to high quality, with NOS scores ≥5. Detailed study characteristics are summarized in Table 2.

Table 2

| First author, year | Design | Country or region | Period of study | Diagnostic criteria | Sample size | Patients in each group | Patients | Volume cut-off (case/year) | Outcome | NOS |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Markovitz 2005 | RCS | USA | 2001–2002 | Severe sepsis | 6,693 | LVH: 1,504 HVH: 5,189 |

Pediatric sepsis | LVH: ≤ 250 HVH: > 250 |

In-hospital mortality | 6/9 |

| Powell 2010 | RCS | USA | 2007 | Sepsis | 87,166 | LVH: 65,035 HVH: 22,131 |

Adult sepsis | LVH: ≤ 371 HVH: > 371 |

In-hospital mortality, early mortality | 6/9 |

| Banta 2012 | RCS | USA | 2005–2010 | Severe sepsis | 1,213,219 | LVH: 1,010,458 HVH: 202,761 |

Adult sepsis | LVH: < 500 HVH: ≥ 500 |

In-hospital mortality | 6/9 |

| Shahin 2012 | RCS | UK | 2008–2009 | Severe sepsis | 30,720 | LVH: 10,460 HVH: 20,260 |

Adult sepsis | LVH: ≤ 537 HVH: > 537 |

In-hospital mortality, ICU mortality, ICU length of stay, hospital length of stay | 8/9 |

| Zuber 2012 | RCS | France | 1997–2008 | Septic shock | 3,437 | LVH: 299 HVH: 3,138 |

Adult sepsis | LVH: < 13 HVH: ≥ 13 |

ICU mortality, ICU length of stay, hospital length of stay | 7/9 |

| Walkey 2013 | RCS | USA | 2011 | Severe sepsis | 1,838 | LVH: 199 HVH: 1,639 |

Adult sepsis | LVH: NA HVH: NA |

In-hospital mortality, hospital length of stay | 7/9 |

| Gaieski 2014 | RCS | USA | 2004–2011 | Severe sepsis | 914,200 | LVH: 319,596 HVH: 594,604 |

Adult sepsis | LVH: < 500 HVH: ≥ 500 |

In-hospital mortality | 7/9 |

| Kocher 2014 | RCS | USA | 2005–2009 | Sepsis | 528,767 | LVH: 317,683 HVH: 211,084 |

Adult sepsis | LVH: NA HVH: NA |

In-hospital mortality, early mortality | 6/9 |

| Shahul 2014 | RCS | USA | 2002–2011 | Severe sepsis | 646,988 | LVH: 94,695 HVH: 552,293 |

Adult sepsis | LVH: < 60 HVH: ≥ 60 |

In-hospital mortality | 7/9 |

| Goodwin 2015 | RCS | USA | 2010 | Severe sepsis | 9,815 | LVH: 497 HVH: 9,318 |

Adult sepsis | LVH: < 75 HVH: ≥ 75 |

In-hospital mortality, hospital length of stay | 6/9 |

| Fawzy 2017 | RCS | USA | 2010–2012 | Sepsis | 287,914 | LVH: 129,148 HVH: 158,766 |

Adult sepsis | LVH: < 353 HVH: ≥ 353 |

In-hospital mortality, hospital length of stay | 7/9 |

| Maharaj 2021 | RCS | UK | 2010–2016 | Sepsis | 273,001 | LVH: 138,221 HVH: 134,780 |

Adult sepsis | LVH: NA HVH: NA |

In-hospital mortality, ICU mortality, hospital length of stay, ICU length of stay | 7/9 |

| Naar 2021 | RCS | USA | 2014–2015 | Sepsis | 10,716 | LVH: 1,350 HVH: 9,366 |

Adult sepsis | LVH: NA HVH: NA |

In-hospital mortality, ICU mortality | 7/9 |

| Chen 2022 | RCS | China | 2020 | Septic shock case | 1,920 | LVH: 943 HVH: 959 |

Adult sepsis | LVH: < 74 HVH: ≥ 74 |

In-hospital mortality, ICU mortality | 7/9 |

| Fujinaga 2024 | RCS | Japan | 2015–2021 | Sepsis | 72,214 | LVH: 55,065 HVH: 17,149 |

Adult sepsis | LVH: < 541 HVH: ≥ 541 |

In-hospital mortality | 8/9 |

| Oami 2024 | RCS | Japan | 2010–2017 | Sepsis | 317,365 | LVH: 158,099 HVH: 159,266 |

Adult sepsis | LVH: < 198 HVH: ≥ 198 |

In-hospital mortality, hospital length of stay, ICU length of stay | 8/9 |

| Scott 2024 | RCS | USA | 2015–2021 | Sepsis | 1,527 | LVH: 760 HVH: 767 |

Pediatric sepsis | LVH: < 100 HVH: ≥ 100 |

In-hospital mortality | 7/9 |

| Ohki 2025 | RCS | Japan | 2014–2018 | Sepsis | 934 | LVH: 700 HVH: 234 |

Pediatric sepsis | LVH: < 26 HVH: ≥ 26 |

In-hospital mortality | 8/9 |

Characteristics of eligible studies.

HVH, high-volume hospitals; LOS, length of stay; LVH, low-volume hospitals; ICU, intensive care unit; NOS, Newcastle-Ottawa Scale; RCS, retrospective cohort study; UK, United Kingdom; USA, United States of America.

3.3 Meta-analysis

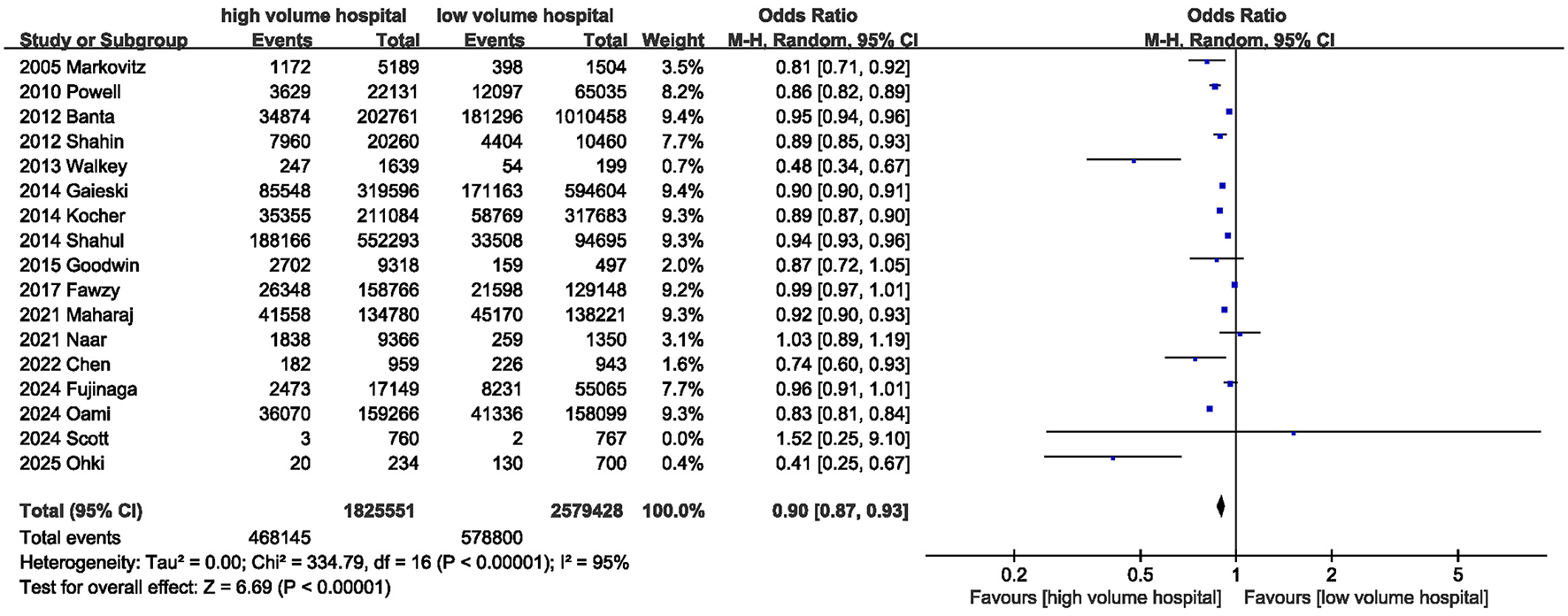

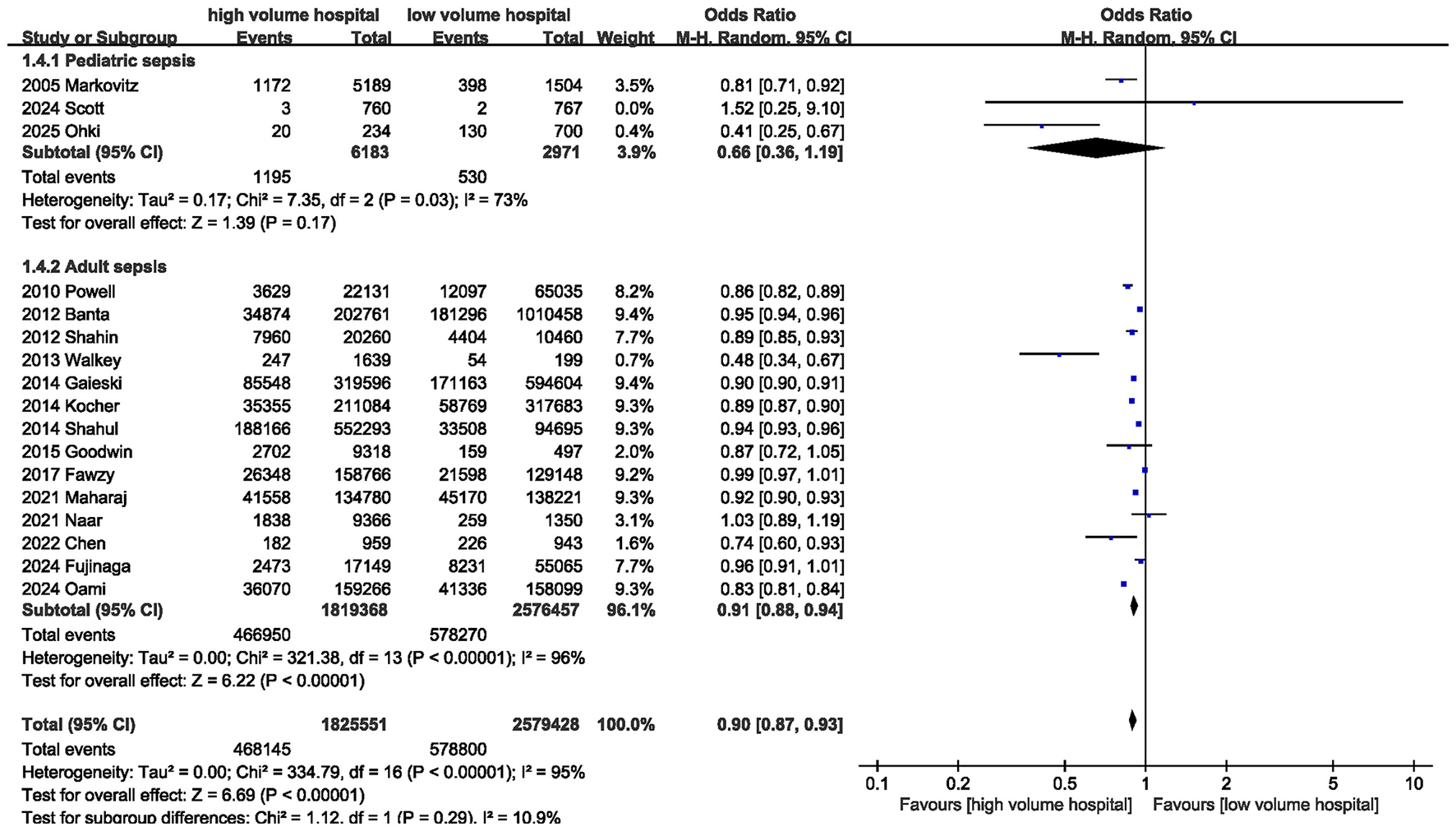

3.3.1 In-hospital mortality

Seventeen studies reported data on in-hospital mortality. The pooled results of the 17 studies showed that in-hospital mortality was significantly lower in high-volume hospitals compared with low-volume hospitals [OR = 0.90 (95% CI: 0.87–0.93, P < 0.00001)] (Figure 2; Table 3); however, substantial heterogeneity was observed among the included studies (I2 = 95%; P < 0.00001).

Figure 2

Meta-analysis of in-hospital mortality between high volume hospital and low volume hospital.

Table 3

| Outcomes of interest | Studies, n | Events for high volume hospital | Events for low-volume hospitals | MD/OR | 95%CI | P-value | I 2 (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| In-hospital mortality | 17 | 468,145/1,825,551 | 578,800/2,579,428 | 0.90 | 0.87, 0.93 | < 0.00001 | 95 |

| ICU mortality | 5 | 38,933/168,503 | 36,093/151,273 | 0.93 | 0.91, 0.94 | < 0.0001 | 24 |

| Early mortality | 2 | 14,791/233,215 | 28,806/382,718 | 0.81 | 0.76, 0.87 | < 0.0001 | 77 |

| ICU length of stay | 4 | – | – | −0.11 | −0.22, −0.01 | 0.04 | 89 |

| Hospital stay | 7 | – | – | 0.35 | −0.71, 1.41 | 0.51 | 99 |

Summary of results of meta-analysis.

CI, confidence interval; ICU, intensive care unit; MD, mean differences; OR, Odds ratio.

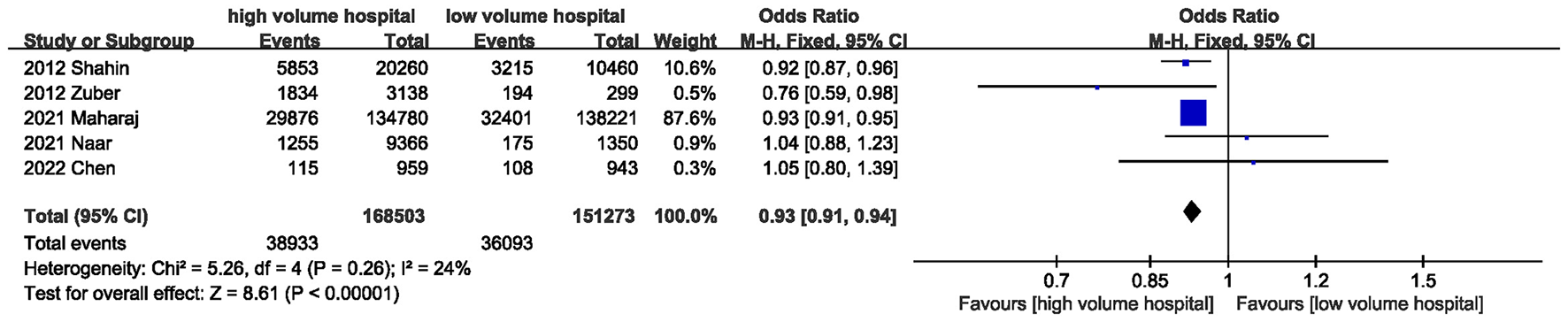

3.3.2 ICU mortality

Five studies assessed ICU mortality. The pooled results indicated that treatment in high-volume hospitals was associated with a lower risk of ICU mortality [OR = 0.93 (95% CI: 0.91–0.94, P < 0.00001)] (Figure 3; Table 3).

Figure 3

Meta-analysis of ICU mortality between high volume hospital and low volume hospital.

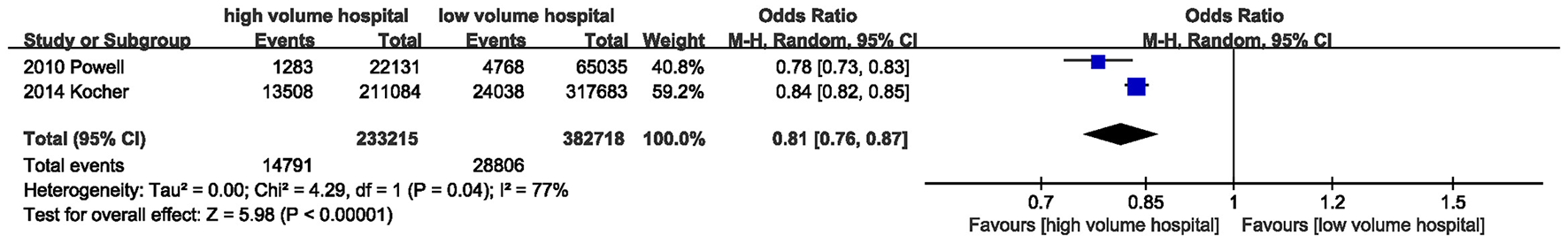

3.3.3 Early mortality

Early mortality was evaluated in two studies, and the pooled results showed that early mortality was lower in high-volume hospitals than in low-volume hospitals [OR = 0.81 (95% CI: 0.76–0.87, P < 0.00001)] (Figure 4; Table 3).

Figure 4

Meta-analysis of early mortality between high volume hospital and low volume hospital.

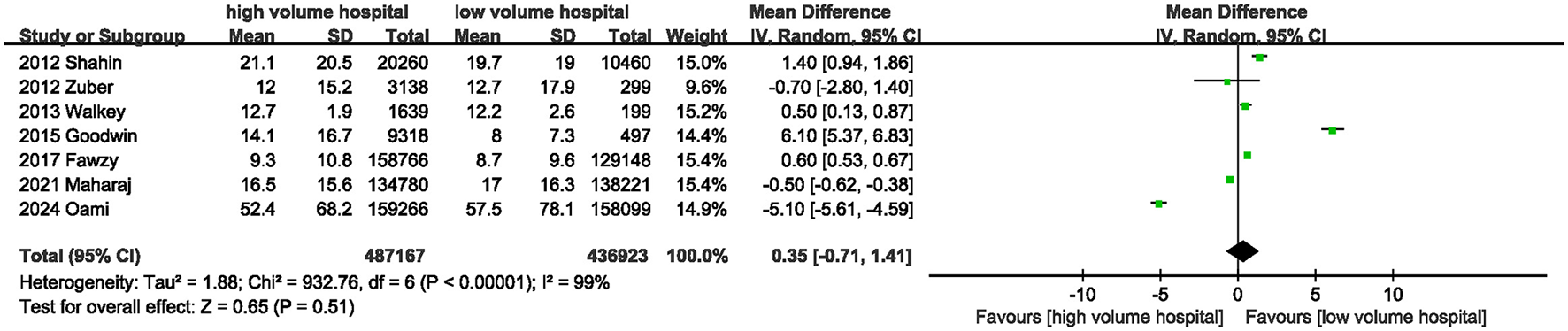

3.3.4 Hospital stay

Seven studies provided information on hospital stay. The combined results showed that the high-volume hospital group had a similar hospital length of stay to the low-volume hospital group [MD = 0.35 days (95% CI: −0.71 to 1.41, P = 0.51)] (Figure 5; Table 3).

Figure 5

Meta-analysis of hospital stay between high volume hospital and low volume hospital.

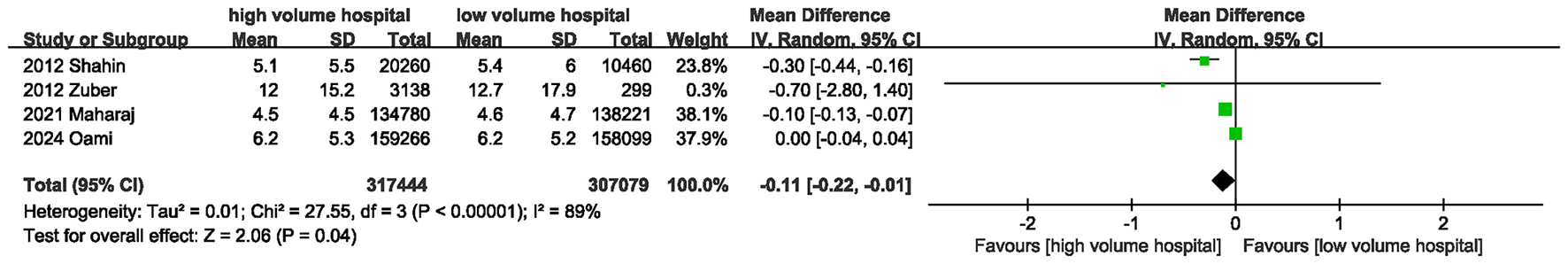

3.3.5 ICU length of stay

The ICU length of stay was reported in 4 trials. The pooled results indicated that treatment in high-volume hospitals was associated with a significantly shorter ICU length of stay compared with low-volume hospitals [MD = −0.11 days (95% CI: −0.22 to −0.01, P = 0.04)] (Figure 6; Table 3).

Figure 6

Meta-analysis of ICU length of stay between high volume hospital and low volume hospital.

3.4 Subgroup analysis

Subgroup analyses were conducted based on age and sepsis definition era (Table 4). In adult patients, treatment in high-volume hospitals was associated with significantly lower in-hospital mortality [OR = 0.91 (95% CI: 0.88–0.94, P < 0.00001)] (Figure 7). In pediatric patients, although mortality was numerically lower in high-volume hospitals, the difference did not reach statistical significance [OR = 0.66 (95% CI: 0.36–1.19, P = 0.17)]. Moreover, in both the pre-2016 and post-2016 sepsis definition subgroups, treatment in high-volume hospitals was consistently associated with reduced in-hospital mortality and ICU mortality. However, no substantial reduction in heterogeneity for in-hospital mortality was observed across these subgroups.

Table 4

| Indicators | Subgrouped by | The number of studies | Effect size | 95%CI | I 2 (%) | P for between subgroup heterogeneity |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| In-hospital mortality | Age | – | – | – | – | 0.29 |

| Adult sepsis | 14 | 0.91 | 0.88, 0.94 | 96 | – | |

| Pediatric sepsis | 3 | 0.66 | 0.36, 1.19 | 73 | – | |

| Sepsis definition era | – | – | – | – | 0.92 | |

| Pre-2016 | 9 | 0.90 | 0.87, 0.93 | 92 | – | |

| Post-2016 | 8 | 0.90 | 0.84, 0.98 | 97 | – | |

| ICU mortality | Sepsis definition era | – | – | – | – | 0.35 |

| Pre-2016 | 2 | 0.91 | 0.86, 0.96 | 51 | – | |

| Post-2016 | 3 | 0.93 | 0.92, 0.95 | 15 | – | |

| ICU length of stay | Sepsis definition era | – | – | – | – | 0.003 |

| Pre-2016 | 2 | −0.30 | −0.44, −0.16 | 0 | – | |

| Post-2016 | 2 | −0.05 | −0.15, 0.05 | 93 | – | |

| Hospital stay | Sepsis definition era | – | – | – | – | 0.01 |

| Pre-2016 | 4 | 1.91 | −0.47, 4.30 | 98 | – | |

| Post-2016 | 3 | −1.62 | −3.06, −0.18 | 100 | – |

Summary of results from subgroup analyses.

ICU, intensive care unit.

Figure 7

Subgroup analysis of in-hospital mortality between high volume hospital and low volume hospital.

3.5 Publication bias and sensitivity analysis

Egger's test (P = 0.519) and funnel plot inspection indicated no significant publication bias for in-hospital mortality (Figure 8). Sensitivity analyses showed that no single study substantially influenced the pooled estimates for in-hospital mortality, ICU mortality, early mortality, or ICU length of stay. However, removal of the study by Oami et al. resulted in a notable change in the pooled estimate for hospital length of stay (MD, 1.32 days; 95% CI, 0.45, 2.20).

Figure 8

![Funnel plot displaying odds ratio (OR) on the x-axis and standard error of the logarithm of OR, SE(log[OR]), on the y-axis with open circles for data points, showing symmetry around a vertical dashed reference line at OR equals one.](https://www.frontiersin.org/files/Articles/1777875/xml-images/fmed-13-1777875-g0008.webp)

Funnel plot of in-hospital mortality between high volume hospital and low volume hospital.

4 Discussion

Over the past two decades, substantial evidence has evaluated the association between hospital volume and clinical outcomes in patients with sepsis; however, the findings remain inconsistent. Gu et al. (24) conducted a meta-analysis of nine studies published before 2015 and reported an inverse association between annual case volume and mortality among patients with sepsis [OR = 0.76 (95% CI: 0.65–0.89, P = 0.001)]. Nevertheless, in recent years, advances in medical technology and evolving sepsis management strategies have substantially altered clinical practice. Therefore, data from more recently published studies may better reflect contemporary real-world care.

In comparison, our meta-analysis incorporated more up-to-date evidence, including 18 studies encompassing a total of 4,408,416 patients. In addition, we evaluated a broader range of clinically relevant outcomes, including in-hospital mortality, ICU mortality, and early mortality. Our findings demonstrate that higher hospital sepsis volume is associated with lower in-hospital mortality, ICU mortality, and early mortality. Moreover, whereas previous meta-analyses focused exclusively on adult patients with sepsis, our study included a wider age spectrum, encompassing both adult and pediatric populations. Age-stratified subgroup analyses showed that higher hospital volume was significantly associated with reduced in-hospital mortality in adult patients. In pediatric patients, although in-hospital mortality was lower in high-volume centers compared with low-volume centers, the difference did not reach statistical significance. These findings have important clinical implications, as they provide evidence supporting an association between higher hospital volume and improved survival outcomes in patients with sepsis, which may help inform healthcare policy and clinical decision-making.

The relationship between hospital volume and clinical outcomes has been well-documented in several medical fields. In complex surgical procedures, such as pancreatic resection, colorectal surgery, pancreaticoduodenectomy, aortic dissection repair, kidney transplantation, and cardiac surgery, high-volume centers consistently demonstrate superior outcomes compared with low-volume centers (25–30). A meta-analysis by Fischer et al. (26) confirmed the positive impact of hospital volume on outcomes following pancreatic surgery. Similarly, Guo et al. (25) reported reduced postoperative mortality after colorectal cancer surgery in high-volume hospitals. Weng et al. (29) found that lower surgeon case volume in kidney transplantation was associated with an increased risk of severe sepsis and graft failure, including mortality. Mortality remains a critical outcome measure in sepsis management, with previous data indicating that in-hospital mortality rates for sepsis remain as high as 26.7% (5). Our results suggest that in-hospital mortality among patients with sepsis is significantly lower in high-volume centers, consistent with several prior studies (2, 31, 32). Ofoma et al. (2) demonstrated that patients with severe sepsis treated in high-volume hospitals had the lowest mortality. Wang et al. (31) assessed healthcare capacity using three ICU volume-related indicators (the proportion of septic shock patients occupying ICU beds, the patient-to-intensivist ratio, and the patient-to-nurse ratio), and found that treatment in hospitals with greater care capacity was associated with lower in-hospital mortality among patients with septic shock. Immunosuppressive conditions are well-established risk factors for mortality in patients with severe infections. Greenberg et al. (32) reported that among patients with sepsis complicated by immunosuppressive diseases, mortality risk was significantly higher in low-volume hospitals than in high-volume hospitals. With regard to the length of hospital stay, no significant difference was observed between high-volume and low-volume hospitals. Although a statistically significant reduction in ICU length of stay was noted in high-volume centers compared with low-volume centers, the magnitude of this reduction was modest, and its clinical relevance may therefore be limited.

Although the hospital volume–outcome relationship was first reported in 1979, the mechanisms underlying the association between higher hospital volume and improved survival in sepsis remain incompletely understood (24). Several potential explanations have been proposed. First, higher patient volumes may enable hospitals to accumulate greater clinical experience, with frequent patient encounters facilitating continuous process optimization and quality improvement, thereby delivering higher-quality care (24). Second, differences in care processes may exist between high- and low-volume centers. Early implementation of standardized sepsis treatment bundles has been associated with lower in-hospital mortality, and adherence to these protocols tends to be higher in high-volume centers, suggesting that more consistent application of evidence-based care may contribute to improved outcomes (6). Third, differences in institutional preparedness may play a role. A U.S.-based study demonstrated that higher emergency department preparedness scores were associated with improved survival, and high-volume centers are more likely to achieve higher preparedness ratings (6, 33). Finally, high-volume hospitals often possess greater healthcare resources, including higher staffing levels, more advanced medical equipment, and improved access to multidisciplinary care teams, all of which may contribute to better sepsis outcomes (4, 34). Ofoma et al. (34) evaluated hospitals based on six resource utilization characteristics (bed capacity, annual sepsis volume, major diagnostic procedures, renal replacement therapy, mechanical ventilation, and major therapeutic interventions), and classified hospitals into low-, medium-, and high-capacity tiers. Lower-capacity hospitals may be better suited to managing less complex sepsis cases.

From a clinical practice perspective, these findings suggest that centralization of sepsis care may help improve patient outcomes (24). However, comprehensive centralization is challenging to implement, particularly in rural or sparsely populated regions. Moreover, the risk–benefit balance of such strategies requires further investigation. In addition to centralization, a tiered care approach may represent a feasible alternative, whereby low-volume centers manage patients with milder disease, while more severe or complex cases are identified early and transferred to high-volume centers. The expanding application of internet-based healthcare systems may further transform current care models by fostering collaborative networks between high- and low-volume centers. Remote multidisciplinary consultations and decision-support guidance may improve outcomes in patients with complex sepsis. In the future, artificial intelligence–assisted tools may also provide valuable decision support for clinicians practicing in low-volume or resource-limited settings (35).

Our study has several strengths. On the one hand, we conducted a comprehensive literature search across multiple databases, thereby minimizing potential selection bias. On the other hand, we focused exclusively on patients with sepsis, ensuring a relatively homogeneous and clinically relevant study population.

This study has the following limitations. First, substantial heterogeneity was observed among the included studies, which may be attributable to differences in study design, regional variations in ICU staffing expertise and experience, healthcare system structures, and definitions of hospital volume. To account for these factors, random-effects models were applied when heterogeneity was high. We also performed age-based subgroup analyses; although higher hospital volume was associated with lower mortality in pediatric patients, the difference did not reach statistical significance. Given the limited number of studies evaluating pediatric sepsis, this finding warrants further investigation. Moreover, variations in the definition of sepsis across studies may represent a potential source of heterogeneity. Given that the Sepsis-3 definitions were updated in 2016, we performed subgroup analyses based on the era of sepsis definition. The results demonstrated that, in both the pre-2016 and post-2016 sepsis definition subgroups, treatment in high-volume hospitals was associated with reduced in-hospital mortality and ICU mortality. No significant heterogeneity was observed between the two subgroups with respect to in-hospital mortality. Second, most included studies were retrospective in nature and therefore subject to inherent limitations of observational designs. Additionally, several studies did not exclude transferred patients; low-volume hospitals are more likely to refer severe or complex cases to high-volume centers, which may attenuate the observed benefits of high-volume care. Nonetheless, our findings still indicate a survival advantage in high-volume centers. Finally, data regarding the impact of hospital volume on long-term outcomes were lacking. Given the observed association between hospital volume and in-hospital mortality, further studies are needed to explore the relationship between hospital volume and long-term outcomes in patients with sepsis.

In conclusion, based on the most recent and currently available evidence, this meta-analysis demonstrates that higher hospital volume is associated with a reduced risk of in-hospital mortality among adult patients with sepsis. However, the relationship between hospital volume and outcomes in pediatric sepsis requires further investigation. Future studies should aim to elucidate the mechanisms underlying the volume–outcome relationship and to identify clinically meaningful volume thresholds associated with improved survival.

Statements

Author contributions

JC: Formal analysis, Writing – original draft, Visualization, Resources, Methodology, Data curation, Supervision, Writing – review & editing, Investigation, Software, Conceptualization. FZ: Project administration, Conceptualization, Data curation, Methodology, Supervision, Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Visualization, Funding acquisition, Software, Formal analysis. DS: Writing – original draft, Formal analysis, Resources, Conceptualization, Data curation, Validation, Writing – review & editing, Software, Investigation. GJ: Visualization, Funding acquisition, Project administration, Validation, Formal analysis, Resources, Data curation, Supervision, Conceptualization, Writing – review & editing, Methodology, Investigation, Writing – original draft, Software.

Funding

The author(s) declared that financial support was received for this work and/or its publication. This work was financially supported by Joint Science and Technology Program of the Department of Science and Technology of the State Administration of Traditional Chinese Medicine and the Zhejiang Provincial Administration of Traditional Chinese Medicine (GZY-ZJ-KJ-24070).

Conflict of interest

The author(s) declared that this work was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declared that generative AI was not used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1.

Palakshappa JA Taylor SP . Management of sepsis in hospitalized patients. Ann Intern Med. (2025) 178:Itc161–76. doi: 10.7326/ANNALS-25-02685

2.

Ofoma UR Dahdah J Kethireddy S Maeng D Walkey AJ . Case volume-outcomes associations among patients with severe sepsis who underwent interhospital transfer. Crit Care Med. (2017) 45:615–22. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000002254

3.

Kanhere MH Kanhere HA Cameron A Maddern GJ . Does patient volume affect clinical outcomes in adult intensive care units?Intensive Care Med. (2012) 38:741–51. doi: 10.1007/s00134-012-2519-y

4.

Fujinaga J Otake T Umeda T Fukuoka T . Case volume and specialization in critically ill emergency patients: a nationwide cohort study in Japanese ICUs. J Intensive Care. (2024) 12:20. doi: 10.1186/s40560-024-00733-3

5.

Chen Y Ma XD Kang XH Gao SF Peng JM Li S et al . Association of annual hospital septic shock case volume and hospital mortality. Crit Care. (2022) 26:161. doi: 10.1186/s13054-022-04035-8

6.

Ohki S Otani M Tomioka S Komiya K Kawamura H Nakada TA et al . Association between hospital case volume and mortality in pediatric sepsis: a retrospective observational study using a Japanese nationwide inpatient database. J Crit Care Med. (2025) 11:87–94. doi: 10.2478/jccm-2025-0006

7.

Kahn JM Linde-Zwirble WT Wunsch H Barnato AE Iwashyna TJ Roberts MS et al . Potential value of regionalized intensive care for mechanically ventilated medical patients. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. (2008) 177:285–91. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200708-1214OC

8.

Naar L Hechi MWE Gallastegi AD Renne BC Fawley J Parks JJ et al . Intensive care unit volume of sepsis patients does not affect mortality: results of a nationwide retrospective analysis. J Intensive Care Med. (2022) 37:728–35. doi: 10.1177/08850666211024184

9.

Higgins JP Thompson SG . Quantifying heterogeneity in a meta-analysis. Stat Med. (2002) 21:1539–58. doi: 10.1002/sim.1186

10.

Markovitz BP Goodman DM Watson RS Bertoch D Zimmerman J . A retrospective cohort study of prognostic factors associated with outcome in pediatric severe sepsis: what is the role of steroids?Pediatr Crit Care Med. (2005) 6:270–4. doi: 10.1097/01.PCC.0000160596.31238.72

11.

Powell ES Khare RK Courtney DM Feinglass J . Volume of emergency department admissions for sepsis is related to inpatient mortality: results of a nationwide cross-sectional analysis. Crit Care Med. (2010) 38:2161–8. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e3181f3e09c

12.

Banta JE Joshi KP Beeson L Nguyen HB . Patient and hospital characteristics associated with inpatient severe sepsis mortality in California, 2005-2010. Crit Care Med. (2012) 40:2960–6. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e31825bc92f

13.

Shahin J Harrison DA Rowan KM . Relation between volume and outcome for patients with severe sepsis in United Kingdom: retrospective cohort study. BMJ. (2012) 344:e3394. doi: 10.1136/bmj.e3394

14.

Zuber B Tran TC Aegerter P Grimaldi D Charpentier J Guidet B et al . Impact of case volume on survival of septic shock in patients with malignancies. Crit Care Med. (2012) 40:55–62. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e31822d74ba

15.

Walkey AJ Wiener RS . Hospital case volume and outcomes among patients hospitalized with severe sepsis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. (2014) 189:548–55. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201311-1967OC

16.

Gaieski DF Edwards JM Kallan MJ Mikkelsen ME Goyal M Carr BG . The relationship between hospital volume and mortality in severe sepsis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. (2014) 190:665–74. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201402-0289OC

17.

Kocher KE Haggins AN Sabbatini AK Sauser K Sharp AL . Emergency department hospitalization volume and mortality in the United States. Ann Emerg Med. (2014) 64:446–57.e6. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2014.06.008

18.

Shahul S Hacker MR Novack V Mueller A Shaefi S Mahmood B et al . The effect of hospital volume on mortality in patients admitted with severe sepsis. PLoS ONE. (2014) 9:e108754. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0108754

19.

Goodwin AJ Simpson KN Ford DW . Volume-mortality relationships during hospitalization with severe sepsis exist only at low case volumes. Ann Am Thorac Soc. (2015) 12:1177–84. doi: 10.1513/AnnalsATS.201406-287OC

20.

Fawzy A Walkey AJ . Association between hospital case volume of sepsis, adherence to evidence-based processes of care and patient outcomes. Crit Care Med. (2017) 45:980–8. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000002409

21.

Maharaj R McGuire A Street A . Association of annual intensive care unit sepsis caseload with hospital mortality from sepsis in the United Kingdom, 2010-2016. JAMA Netw Open. (2021) 4:e2115305. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.15305

22.

Oami T Imaeda T Nakada TA Aizimu T Takahashi N Abe T et al . Association of intensive care unit case volume with mortality and cost in sepsis based on a Japanese nationwide medical claims database study. Cureus. (2024) 16:e65697. doi: 10.7759/cureus.65697

23.

Scott HF Lindberg DM Brackman S McGonagle E Leonard JE Adelgais K et al . Pediatric sepsis in general emergency departments: association between pediatric sepsis case volume, care quality, and outcome. Ann Emerg Med. (2024) 83:318–26. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2023.10.011

24.

Gu WJ Wu XD Zhou Q Zhang J Wang F Ma ZL et al . Relationship between annualized case volume and mortality in sepsis: a dose-response meta-analysis. Anesthesiology. (2016) 125:168–79. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0000000000001133

25.

Guo YR Bai X Lu XS Tang XY Sun YD Lang JX et al . Hospital volume matters: a meta-analysis of mortality after colorectal cancer surgery. Int J Surg. (2025) 111:9634–45. doi: 10.1097/JS9.0000000000003168

26.

Fischer C Alvarico SJ Wildner B Schindl M Simon J . The relationship of hospital and surgeon volume indicators and post-operative outcomes in pancreatic surgery: a systematic literature review, meta-analysis and guidance for valid outcome assessment. HPB. (2023) 25:387–99. doi: 10.1016/j.hpb.2023.01.008

27.

De León Ayala IA Chang FC Chen CY Cheng YT Chan YH Wu VC et al . Hospital volume and outcomes of surgical repair in type A acute aortic dissection: a nationwide cohort study. PLoS ONE. (2025) 20:e0325689. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0325689

28.

Zhuli Y Su C Shen L Yang F Zhou J . Improved robotic-assisted cardiac surgery outcomes with greater hospital volume: a national representative cohort analysis of 10,543 cardiac surgery surgeries. J Robot Surg. (2025) 19:142. doi: 10.1007/s11701-025-02308-2

29.

Weng SF Chu CC Chien CC Wang JJ Chen YC Chiou SJ . Renal transplantation: relationship between hospital/surgeon volume and postoperative severe sepsis/graft-failure. A nationwide population-based study. Int J Med Sci. (2014) 11:918–24. doi: 10.7150/ijms.8850

30.

Conroy PC Calthorpe L Lin JA Mohamedaly S Kim A Hirose K et al . Determining hospital volume threshold for safety of minimally invasive pancreaticoduodenectomy: a contemporary cutpoint analysis. Ann Surg Oncol. (2022) 29:1566–74. doi: 10.1245/s10434-021-10984-1

31.

Wang L Ma X Qiu Y Chen Y Gao S He H et al . Association of medical care capacity and the patient mortality of septic shock: a cross-sectional study. Anaesth Crit Care Pain Med. (2024) 43:101364. doi: 10.1016/j.accpm.2024.101364

32.

Greenberg JA Hohmann SF James BD Shah RC Hall JB Kress JP et al . Hospital volume of immunosuppressed patients with sepsis and sepsis mortality. Ann Am Thorac Soc. (2018) 15:962–9. doi: 10.1513/AnnalsATS.201710-819OC

33.

Ames SG Davis BS Marin JR Fink EL Olson LM Gausche-Hill M et al . Emergency department pediatric readiness and mortality in critically ill children. Pediatrics. (2019) 144:e20190568. doi: 10.1542/peds.2019-0568

34.

Ofoma UR Deych E Mohr NM Walkey A Kollef M Wan F et al . The relationship between hospital capability and mortality in sepsis: development of a sepsis-related hospital capability index. Crit Care Med. (2023) 51:1479–91. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000005973

35.

Lin Z Deng J Chen S He J Li Z Mo J et al . Global trends, collaboration networks and knowledge mapping of artificial intelligence evolution in sepsis diagnosis and management: a bibliometric analysis. Digit Health. (2025) 11:20552076251396574. doi: 10.1177/20552076251396574

Summary

Keywords

hospital case volume, ICU mortality, in-hospital mortality, meta-analysis, sepsis

Citation

Chen J, Zhang F, Sun D and Jin G (2026) Impact of hospital sepsis case volume on mortality in sepsis patients: a meta-analysis. Front. Med. 13:1777875. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2026.1777875

Received

30 December 2025

Revised

25 January 2026

Accepted

29 January 2026

Published

16 February 2026

Volume

13 - 2026

Edited by

Marcos Ferreira Minicucci, São Paulo State University, Brazil

Reviewed by

Marie Al Rahmoun, INSERM Biologie cellulaire, développement et évolution, France

Antony Arumairaj, New York City Health and Hospitals Corporation, United States

Updates

Copyright

© 2026 Chen, Zhang, Sun and Jin.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Guangjun Jin, jinguangjun1973@163.com

†These authors have contributed equally to this work and share first authorship

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.