Abstract

Salvia is a genus of Lamiaceae family with more than 1,000 species having diverse utility. The wide range of uses encompasses food, flavor, cosmetics, aromatherapy, horticulture, and medicine. It has been attributed to the presence of bioactive compounds belonging to essential oils, phenolic compounds, and flavonoids that are extensively studied using spectroscopic and chromatographic techniques. This review aims to investigate in-depth previously published literature from 2020 to 2025 on 59 Salvia species. It was performed with several key search words focused on the chemical compounds in Salvia spp. and their pharmacological efficacy. Salvia species were enriched with essential oils comprising important components: α-pinene, β-pinene, limonene, linalool, caryophyllene, germacrene, myrcene, α-thujone, and humulene. Potential health benefits owing to anticancer, antioxidant, antidiabetic, anti-inflammatory, antithrombotic, antirheumatic, and antiviral properties were reported from Salvia species. Salvia phytochemicals have been studied as regulating anticancer mechanisms at the cellular level by effectively modulating host cell responses in multiple ways. This review summarizes and discusses recent studies on the metabolite profiling of Salvia plants and bioactivities of the extracts and compounds. It may provide future perspectives on the in silico and pharmacognostic studies on potent Salvia compounds. Isolation and evaluation of bioactive compounds from the least studied species is recommended.

Graphical Abstract

1 Introduction

Plants are an important source of medicine in all eras (Nwozo et al., 2023). For centuries, herbal medicines and bioactive plant compounds have been used as traditional curatives. Now, these are progressively integrated into modern medical practices (Kızıltaş et al., 2023; Bjørklund et al., 2024). Medicinal plants are widely used to treat various diseases. They possess health-promoting effects and are used to treat neurological disorders (Nasir et al., 2024), glaucoma, cancer (Samuel et al., 2024), and other diseases related to oxidative stress (Karagecili et al., 2023; Ashraf et al., 2024). It is well established that medicinal plants are a source of active compounds, including alkaloids, terpenoids, phenolic compounds, flavonoids, and fatty acids, which exhibit significant biological activity (Bingol et al., 2021; Anbessa et al., 2024). The Lamiaceae family comprises more than 7,000 species and 250 genera, including many culinary herbs such as basil, mint, rosemary, and thyme (Ali et al., 2024; Cristani and Micale, 2024). The subfamily Nepetoideae encompasses 33 genera and approximately 3,685 species. Species of this subfamily have culinary value, medicinal properties, and are ingredients in the cosmetic industry (Ortiz-Mendoza et al., 2022). Salvia is the largest genus of herbaceous perennials (Ihsan et al., 2024). It consists of more than 1,000 distinct species and is found on several continents across the world (Esmaeili et al., 2022; Kalnyuk et al., 2025). Salvia is widely distributed throughout the Mediterranean, eastern and southern Asia, and Mexico/South America (Abd Rashed and Rathi, 2021; Mátis et al., 2023; Nikolova and Aneva, 2017) mentioned in their study that 36 species in the Flora Europea belong to the genus Salvia. Salvia, derived from the Latin word “salvare” or sage, meaning “to heal”. Salvia species have been used since ancient times to treat a variety of diseases, including colds, cardiovascular diseases, gastric diseases, diabetes, and bronchitis (Deshmukh, 2022; Uysal et al., 2023; Kharazian et al., 2024).

Plants are described as herbaceous and belong to all life forms (annuals, biennials, and perennials). The flowers grow in clusters and range in color from blue to red, with white and yellow less prevalent (Figure 1) (Askari et al., 2021). The stamens of Salvia species are described as lever-shaped stamens formed by elongated connective and stamen filaments (Kalnyuk et al., 2025). Plant species of this genus play a crucial role in traditional medicine (Li et al., 2021) and horticulture. This is due to the presence of various phytochemicals, including essential oils, phenolic compounds, and flavonoids. Promising pharmacological properties: antioxidant (Jing et al., 2023), antidiabetic (Niu et al., 2022), antimicrobial (Dembińska et al., 2025), anti-inflammatory (Liu et al., 2023), and cytotoxic properties (Demirpolat, 2023) have been reported in Salvia species. These effects are attributed to key compounds such as rosmarinic acid [1], salvianolic acids [146, 167, 168, 197, 199], camphor [48], and 1,8-cineol [43] (Terzi et al., 2025). Additionally, the genus is economically important in aromatherapy and cosmetics due to its fragrance-rich oils. The composition of essential oils varies significantly between species and environmental conditions, making these plants a subject of ongoing phytochemical studies (Giuliani et al., 2020). For a long time, sage has been extensively used to flavor food, aromatics, and beauty products (Uysal et al., 2023).

FIGURE 1

(A) Illustration of Salvia miltiorrhiza (1), and Salvia nemorosa (2). (B) Photographs of Salvia verticillata L. (3) and Salvia nemorosa L. subsp. nemorosa (4) from the herbarium specimens of Prof. Jarosław Proćków.

Diverse chemical compounds and the composition of essential oils (EOs) are observed in the species of sage, such as Salvia deserta (desert sage), consisting of 0.02% EOs in aerial parts. In comparison, the seeds contain 23% fatty acids (Zhumaliyeva et al., 2023). Salvia rosmarinus Spenn. has analgesic, antitumor, and antioxidant activity, and EOs have applications in cosmetics and aromatherapy (Dejene et al., 2025). This review examines the therapeutic potential of 59 Salvia extracts in healthcare, identifies key chemical constituents in various Salvia species, and explores their mechanistic pharmacological relevance. A total of 43 Salvia species were reported in studies on their chemical profile. It revealed the presence of 273 bioactive metabolites belonging to the group: phenolic acids, terpenes, flavonoids, essential oils, and fatty acids. However, it is observed that 37 species of Salvia were evaluated for pharmacological efficacy. It includes the evaluation of their antioxidant, anticancer, antimicrobial, antidiabetic, anti-inflammatory, and neuroprotective activity. Twenty-two species were studied both for chemical profiling and biological activity. Some of these commonly analyzed Salvia plants were: S. officinalis L., S. rosmarinus, S. cadmica Bioss., S. verticillata, S. nemorosa L., S. fruticosa Mill., S. verbenaca L., S. palaestina Benth., S. hispanica L., and S. miltiorrhiza Bunge.

2 Materials and methods

A systematic approach was used to analyze, collect, and summarize recent studies and trends in research work conducted around the world on 59 Salvia species (Table 1). Data collection was carried out for this study, focusing on the aspects of phytochemistry and pharmacological effects of Salvia species. The data on ethnomedicinal use, phytochemical compounds, and pharmacological activities were collected from recent literature studies. Different databases were used to access publications: PubMed, SpringerLink, Scopus, Web of Science, ScienceDirect, and Wiley Online. For the identification of relevant publications, keywords such as “Chemical profile of Salvia” and “Salvia bioactivities” are used. Searches were made for the literature published from 2020 to 2025. Secondary metabolites of Salvia and therapeutic activities were taken as inclusion criteria for publications. Inclusive criteria were taxonomic, agricultural, and environmental studies on the selected genus. The naming of plants was verified using the World Flora Online portal (WFO). Their full names, with citations to their authors’ names, are given in Tables 1, 3, 4. Figures were designed using Canva Software.

TABLE 1

| Plant Taxa from the Salvia genus | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| S. officinalis L | S. rosmarinus | S. santolinifolia Boiss | S. macrosiphon Boiss |

| S. absconditiflora Greuter & Burdet | S. mirzayanii Rech f. and Esfand | S. compressa Vent | S. leucantha Cav |

| S. verbenaca L | S. hispanica | S. verticillata L | S. hydrangea DC. ex Benth |

| S. palaestina Benth | S. aethiopis L | S. chudaei Batt. and Trab | S. fructicosa × officinalis |

| S. fruticosa Mill | S. aristata Aucher ex Benth | S. substolonifera E. Peter | S. tomentosa Mill |

| S. apiana | S. lanceolata Lam | S. chamelaeagnea Berg | S. limbate |

| S. cadmica Boiss | S. aurea L. (S. africana-lutea L) | S. chloroleuca Rech f. and Allen | S. divinorum Epling and Játiva |

| S. sclarea L | S. ceratophylla | S. plebeia | S. balansae Noë ex Coss |

| S. potentillifolia | S. russellii | S. elegans Vahl | S. spinosa |

| S. pisidica | S. bucharica | S. tebesana Bunge | S. eremophila |

| S. multicaulis | S. sahendica | S. lachnocalyx Hedge | S. dominica |

| S. hierosolymitana | S. caespitosa | S. leriifolia | S. repens Burch. ex. Benth |

| S. barrelieri | S. deserta Schangin | S. lavandulaefolia | S. uliginosa Benth |

| S. aspera | S. nemorosa L | S. miltiorrhiza | S. cilicica Boiss |

| S. triloba | S. atropatana | S. chorassanica | |

List of 59 Salvia species reviewed for the Phytochemical and Bioactivities Assessment.

3 Results and discussion

3.1 Phytochemical composition of Salvia species

Flavonoids, anthocyanins, phenolic acids, phenolic glycosides, polysaccharides, terpenoids, coumarins, and essential oils are among the main phytochemicals found in Salvia species (Moshari-Nasirkandi et al., 2024). The bioactivity of Salvia species is owed to the presence of this diverse range of chemical compounds (Bingol et al., 2021) as shown in Table 2. This table enlists 20 species and 273 compounds from these groups: phenolic acids, flavonoids, terpenoids, fatty acids, and sterols.

TABLE 2

| Plant species | Plant part/Fraction | Isolation technique | Analytical method | Compounds | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| S. cadmica Boiss | Aerial and roots/Hydromethanolic | Not available | UPLC-DAD/ESI-MS/MS HPLC-DAD |

Rosmarinic [1], salvianolic acid K [2] | Piątczak et al. (2021) |

|

S. absconditiflora Greuter & Burdet S. sclarea L S. palaestina Benth |

Aerial/Ethylacetate | Maceration | HPLC-MS/MS | Cynaroside [3], rosmarinic acid [1], cosmosiin [4], luteolin [5], apigenin [6], acacetin [7] | Onder et al. (2022) |

| S. verbenaca L | Aerial/Essential Oils (EOs) | Steam Distillation | GC-MS | Germacrene D [8], β-phellandrene [9], α-copaene [10], β-caryophyllene [11], epi-α-cadinol [12], and 1,10-di-epi-cubenol [13] | Belloum et al. (2014), Mrabti et al. (2022) |

| S. verbenaca L | Flower/Volatile Organic Constituents (VOCs) | HS-SPME | GC-MS | γ-Selinene [14], germacrene D [8], β-caryophyllene [11], sabinene [15], and trans-sabinene hydrate [16] | Al-Jaber et al. (2020), Khouchlaa et al. (2021) |

| S. fruticosa Mill | Leaves/70% ethanol | Ultrasound-assisted Extraction | LC-Q-Orbitrap HRMS | salvigenin [17], apigenin [6], jaceosidin [18], genkwanin [19], isorhamnetin [20], hesperidin [21] | Mróz and Kusznierewicz (2023) |

| S. hispanica L | Aerial/70% ethanol | Cold Maceration | UPLC-ESI-MS/MS | β-sitosterol [22], betulinic acid [23], oleanolic acid [24], β-sitosterol-3-O-β-D-glucoside [25] | Abdel Ghani et al. (2023) |

| S. hispanica L | Seeds/85% methanol | Maceration | UPLC-ESI-MS | Raffinose [26], rosmarinic acid [1] and its derivatives, saponarin [27] and its isomer, Vicenin-2 [28], oleic acid [29], hederagenin [30] | Mohamed et al. (2024) |

| S. hispanica L | Seeds/ethylacetate | Maceration | GLC-MS | Palmitic acid [31], α-Linolenic acid [32], stearic acid [33], γ-sitosterol [34], and β-sitosterol [22] | |

| S. macrosiphon Boiss | Aerial/methanol | Maceration | CC, TLC, NMR | 13-epi manoyl oxide [35], 6-α-hydroxy-13-epimanoyl oxide [36], 5-hydroxy-7,4′-dimethoxyflavone [37], and β-sitosterol [22] | Balaei-Kahnamoei et al. (2021) |

| S. leucantha Cav | Aerial parts/EOs | Steam Distillation | Steam distillation GC-MS and GC-FID |

6.9-guaiadiene [38], (E)-caryophyllene [39], germacrene D [8], (E)-β-farnesene [40], and bicyclogermacrene [41] | Villalta et al. (2021) |

| S. hydrangea DC. ex Benth | Leaves and flowers/EOs | Hydrodistillation | GC-MS | Spathulenol [42], 1,8-cineole [43], β-caryophyllene [11], β-pinene [44], β-eudesmol [45] in leaves, while flowers contain caryophyllene oxide [46], 1,8-cineole [43], β-caryophyllene [11], β-eudesmol [45], caryophyllenol-II [47], and camphor [48] | Ghavam et al. (2020) |

| S. officinalis L | Ariel/EOs | Hydrodistillation | GC-MS | Naphthalenone [49], camphor [48], 1.8-cineole [43], and α-thujone [50] | Assaggaf et al. (2022) |

| S. tomentosa Mill | Whole plant/EOs | Hydrodistillation | GC-MS and GC-FID | Camphor [48], γ-muurolene [51], α-pinene [52], α-caryophyllene [53], viridiflorol [54], δ-cadinene [55], and terpinene-4-ol [56] | Koçer and İstifli (2022) |

| S. sclarea L | Ariel/EOs | Hydrodistillation | GC-MS | Linalool acetate [57], linalool [58], (E)-caryophyllene [39], p-cymene [59], a-terpineol [60], and geranyl acetate [61] | Kačániová et al. (2023), Bojan et al. (2024) |

| S. officinalis L | Ariel/EOs | Hydrodistillation | GC-MS | Camphor [48], 1,8-cineole [43], β-pinene [44], camphene [62], and α-thujone [50] | Tundis et al. (2020) |

| S. balansae Noë ex Coss | Leaves/Methanol | Maceration | HPLC-DAD | Luteolin [5], ferulic acid [63], vanillic acid [64], kaempferol [65], benzoic acid [66], quercetin [67], myricetin [68], and ascorbic acid [69] | Mokhtar et al. (2023) |

| S. chudaei Batt. and Trab | Aerial/ethanol | Maceration | HPLC | Catechin hydrate [70], resorcinol [71], ferulic acid [63], sinapic acid [72], and resveratrol [73] | Tlili et al. (2025) |

| S. substolonifera E. Peter | Whole plant/95% ethanol | Maceration | CC, TLC, NMR, FTIR, HRESIMS | Substolide H [74], ferruginol [75], dihydrotanshinone I [76], methyl rosmarinate [77], ursolic acid [78], caffeic acid [79], and digitoflavone [80] | Zhong et al. (2025) |

| S. santolinifolia Boiss | Roots/90% methanol | Maceration | 1 D, 2 D NMR, and HR-ESIMS | Aegyptinone E [81], aegyptinone A [82], and aegyptinone D [83] | Sargazifar et al. (2024) |

| S. compressa Vent | Shoots/dichloromethane | Maceration | CC, NMR | Citrostadienol [84], β-sitosterol [22], linolenic acid [85], linoleic acid [86], palmitic acid [31], and geraniol [87] | Noorbakhsh et al. (2022) |

|

S. aurea L. (S. africana-lutea L) S. lanceolata Lam S. chamelaeagnea Berg |

Aerial/Methanol | Ultrasonic-assisted Extraction | UPLC-qToF-MS | Caffeic acid [79], rosmarinic acid [1], carnosol [88], carnosic acid [89], and ursolic acid [78] | Tock et al. (2021) |

| S. officinalis L | Leaves/water | Water bath shaking | UPLC-MS/MS | Procyandinin trimer [91], epigallocatechin gallate [92], epicatechin gallate [93], catechin [94], epicatechin [95], Ruthin [96], kaempferol-3-rutinoside [97], quercetin-3-rhamnoside [98], kaempferol-3-o-hexoside [99], luteolin [5], apigenin [6], rosmarinic acid [1], chlorogenic acid [100], ferulic acid [63], caffeic acid [79], syringic acid [101], gallic acid [102], hydroxybenzoic acid [103] | Maleš et al. (2022) |

| S. hispanica | Seed/oil | Orbital Shaking | HPLC | Rosmarinic acid [1], chlorogenic acid [100], gallic acid [102], and caffeic acid [79] | Gebremeskal et al. (2024), Mutlu et al. (2025) |

| S. hispanica | Seed/oil | Cold Pressing | LC-HRMS | Ascorbic acid [69], chlorogenic acid [100], caffeic acid [79], rosmarinic acid [1], ellagic acid [104], salicylic acid [105], hispidulin [106], and luteolin [5] | Mutlu et al. (2025) |

| S. aethiopis L | Ariel/ethanol | Orbital Shaking | LC-MS/MS | Hydroxybenzoic acid [103], caffeic acid [79], ellagic acid [104], p-Coumaric acid [107], rosmarinic acid [1], syringic acid [101], chlorogenic acid [100], ferulic acid [63], hyperoside [108], hesperidin [21], rutin [109], luteolin [5], kaempferol [65], quercetin [67], apigenin [6], galangin [110], naringenin [111], and genkwanin [10] | Bilginoğlu et al. (2025) |

| S. aristata Aucher ex Benth | Aerial/EOs | Hydrodistillation | GC-MS | β-caryophyllene [11], caryophyllene oxide [46], bicyclogermacrene [41] | Dabaghian et al. (2025) |

| S. officinalis L | Aerial/ethanol | Maceration | LC-ESI-MS | Cirsilineol [113], cirsiliol [114], luteolin [5], apigenin [6], naringenin [111], kaempferol [65], quercetin [67], naringin [115], apigenin-7-o-glucoside, [116], luteolin-7-o-glucoside [117], rosmarinic acid [1], syringic acid [101], p-coumaric acid [107], caffeic acid [79], protocatechuic acid [118], chlorogenic acid [100], quinic acid [119], and ferulic acid [63] | Akrimi et al. (2025) |

| S. officinalis L | Leaves/EOs | HS-SPME | GC-MS | Hexanal [120], trans-salvene [121], cis-salvene [122], tricyclene [123], camphene [62], α-thujene [124], α-pinene [52], β-pinene [44], sabinene [15], 1-octen-3-ol [125], α-phellandrene [126], α-terpinene [127], γ-terpinene [128], p-cymene [59], eucalyptol [130], cis-sabinene hydrate [131], cis-linalool oxide [132], linalool [58], terpinolene [133], α-thujone [50], β-thujone [134], α-campholenal [135], camphor [48], iso-thujol [136], humulene-1,2-epoxide [137], viridiflorol [54], β-caryophyllene [11], and α-humulene [138] | Pachura et al. (2022) |

| S. deserta Schangin | Roots/95% ethanol | Maceration | HPLC | Salvidesertone A [139], Salvidesertone B [140], Salvidesertone C [141], 8α,9α-epoxy-7-oxoroyleanone [142], 8α,9α-epoxy-6-deoxycoleon U [143] | Zheng et al. (2020) |

| S. verticillata L | Aerial/Methanol | Maceration | UPLC/MS-MS | Salvianic acid A [144], caffeic acid [79], coumaric acid [145], salvianolic acid C [146], dicaffeoylquinic acid [147], hydroxyrosmarinic acid [148], rosmarinic acid [1], quercetin 3-O-rutinoside [149], luteolin 7-O-glucoside [117], luteolin 7-O-hexuronide [150], quercetin 3-O-rhamnoside [151], apigenin 7-O-glucoside [116], apigenin 7-O-hexuronide [152], and apigenin [6] | Stanković et al. (2020) |

| S. verbenaca L | Aerial/EOs | Steam Distillation | GC-MS | α-pinene [52], β-pinene [44], sabinene [15], 1,8-cineole [43], β-phellandrene [9], linalool [58], p-cymene [59], linalyl acetate [153], E-β-ocimene [154], (Z)-β-ocimene [155], tricyclene [123], camphor [48], 1,10-di-epi-cubenol [13], epi-13-manool [156], cis-muurola-3,5-diene [157], γ-selinene [14], trans-sabinene hydrate acetate [158], β-caryophyllene [11], viridiflorol [54], and germacrene D [8] | Aissaoui et al. (2014), Mrabti et al. (2022) |

| S. mirzayanii Rech f. and Esfand | Seeds/80% methanol | Maceration | GC-MS | Linalool [58], spathulenol [42], δ-cadinene [55], cubenol [159], β-eudesmol [45], α-cadinol [160], linalyl acetate [153], and α-terpinyl acetate [161], teuclatriol [162], bicyclogermacrene [41], chrysoeriol [163], cirsimaritin [164], salvigenin [17] | Shahraki et al. (2024) |

| S. nemorosa L | Aerial/80% Methanol | Ultrasonic bath | UHPLC-HRMS | Rosmarinic acid [1], ferulic acid [63], caffeoylquinic acid [165], syringic acid [101], sagerinic acid [166], salvianolic acid A [167], salvianolic acid B [168], salvianolic acid C [146], salvianolic acid K [2], yunnaneic acid F [169], yunnaneic acid E [170], caffeic acid [79], sagecoumarin [171], verbascoside [172], forsythoside A [173], myricitrin [174], hyperoside [108], eriodictyol-O-glucuronide [175], hispidulin [106], genistein [176], 6-hydroxyluteolin 7-O-glucuronide [177], lipedoside A [178], luteolinglucoside [179], luteolin [5], luteolinglucuronide, apigenin 7-O-glucoside [180], apigenin [6], kaempferol [65], luteolin acetyl glucoside [181] | Moshari-Nasirkandi et al. (2024) |

| S. miltiorrhiza Bunge | Roots/Methanol | Water bath | UHPLC | Tanshinone I [182], cryptotanshinone [183] | Tran et al. (2024) |

| S. elegans Vahl | Aerial/ethylacetate | Maceration | HPLC | a-amirin [184], b-amirin [185], ursolic acid [78], oleanolic acid [186], corosolic acid [187], maslinic acids [188], and eupatorine [189] | Gutiérrez-Román et al. (2022) |

Secondary metabolites reported in different parts and extracts of Salvia species, along with the isolation technique and analytical methods.

3.1.1 Non-volatile compounds present in Salvia species

The storage of non-volatiles was observed in plant parts such as flavonoids, triterpenoids, monoterpenoids, and sesquiterpenoids in the above-ground portion, while roots accumulate diterpenoids and phenolic acids. These compounds are believed to impart useful properties of promoting health and healing (Askari et al., 2021). Different groups of non-volatiles are present in the species of sage: terpenoids (diterpenes, triterpenes, sisterpenes), flavonoids (flavanols, flavonols, flavones), caffeic acid derivatives, and phenolic acids (Tock et al., 2021; Maciel et al., 2022; Maleš et al., 2022; Luca et al., 2023). More than 160 polyphenols have been identified in Salvia species. Caffeic acid occurs mainly in the dimer form, as rosmarinic acid [1], in the Lamiaceae family. It is a building block for a variety of plant metabolites, from monomers to oligomers, and a large number of polyphenolic compounds are constructed from it through various condensation reactions (Zhumaliyeva et al., 2023).

Natural phenolic compounds exhibit many beneficial health effects in humans (Saleem et al., 2022), including antioxidant, antimicrobial (Dembińska et al., 2025), anticancer (Kapil et al., 2025), and anti-inflammatory activity (Liu et al., 2023). Lamiaceae and its largest genus, Salvia, are among the richest sources of antioxidant and antimicrobial phenolics (Piątczak et al., 2021). In a study by Onder et al. (2022), acacetin [7] was the highest phenolic compound in the extracts of S. sclarea and S. palaestina (24.094 and 69.297 mg analyte/g of dry extract, respectively). The total flavonoid content was 83.23, 60.62, and 58.71 mg RE/g of extract in S. palaestina, S. absconditiflora, and S. sclarea, respectively. Righi et al. (2021) quantified phenolics in the extract of S. verbenaca, and the amount was 206 mg GAE/g extract. Moshari-Nasirkandi et al. (2024) analyzed the TPC and TFC of 102 samples from 20 species of Salvia. The maximum TPC of >55 mg GAE/g DW was shown by samples of S. ceratophylla, S. verticillata, S. nemorosa, and S. limbata. These species were also rich in TFC. Nilofar et al. (2024) reported a TPC of 92.10 mg GAE/g and a TFC of 50.85 mg RE/g in the Salvia hybrid (S. fructicosa × officinalis), providing the plant with promising antioxidant activity. Some of the phenols listed in the study are shown in Figure 2 (Nilofar et al., 2024).

FIGURE 2

Different classes of phenols present in Salvia species.

Khouchlaa et al. (2021) enlisted the main phenolics in S. verbenaca, such as: rosmarinic acid [1], p-hydroxybenzoic acid [190], and caffeic acid [79]. They reported the presence of four flavonic aglycons (apigenin [6], luteolin [5], salvigenin [17], and 5-hydroxy-7,4′-dimethoxyflavone [37]) in the leaves of S. verbenaca from Spain and three flavonoids (5-hydroxy-3,4′,7-trimethoxyflavone [191], retusin [192], verbenacoside [193]) in aerial parts of samples collected from Saudi Arabia. Naringenin [111], hesperidin [21], and cirsiliol [114] were the main flavonoids identified in the flowering stage of Tunisian species.

Rashwan et al. (2021) identified 12 polyphenols by HPLC analysis of S. officinalis EOs. The main compounds were coumaric acid [145] (0.043 mg/g), chlorogenic acid [100] (0.037 mg/g), caffeic acid [79] (0.028 mg/g), catechin [94] (0.025 mg/g), vanillin [194] (0.024 mg/g), ellagic acid [104] (0.019 mg/g), gallic acid [102] (0.017 mg/g) and naringenin [111] (0.011 mg/g). Francik et al. (2020) studied the phenolic composition of S. officinalis dried in different ways. Ferulic acid [63], rutin [109], hesperidin [21], catechin [94], quercetin [67], isorhamnetin [20], 3,5-dicaffeoylquinic acid [195], p-coumaric acid [107], and sinapinic acid [196] were reported in all samples. Maciel et al. (2022) reported the presence of caffeic acid [79], rosmarinic acid [1], salvianolic acid I [197], methyl salvianolate I [198], salvianolic acid K [2], salvianolic acid L [199], and sagerinic acid [166] in S. officinalis. Krol et al. (2022) observed the accumulation of different phenolics in S. apiana. The ethanol extract contained cirsimaritin [164] and salvigenin [17], whereas in the decoction, hesperidin [21], quercetin-O-hexoside [200], and cirsimaritin [164] were observed. Rosmarinic acid [1] was determined in methanol extracts (1.1 mg/mL).

Phenolic acids and tanshinones are the main bioactive ingredients of S. miltiorrhiza. Pharmacologically active phenolics are rosmarinic acid [1] and salvianolic acid B [168], which play a role in anticoagulation, antioxidation, and antithrombosis (Deng et al., 2020; Tran et al., 2024). Park et al. (2025) reported phenolic acids such as caffeic acid [79], sinapic acid [72], benzoic acid [66], ferulic acid [63], rosmarinic acid [1], trans-cinamic acid [202], salvianolic acid A [167], and salvianolic acid B [168] in the ethanol extract of S. miltiorrhiza.

Mokhtar et al. (2023) identified catechin [94] (72.5%), myricetin [174] (21.7%), epicatechin [95] (1.3%), butylated hydroxyanisole [201] (1.1%) as the main phenolics in S. balansae by HPLC-MS. Motyka et al. (2022) reported the presence of polyphenols in the seeds of S. hispanica, such as gallic acid [102], caffeic acid [79], ferulic acid [63], p-coumaric acid [107], chlorogenic acid [100], rosmarinic acid [1], apigenin [6], kaempferol [65], quercetin [67], myricetin [68], rutoside [203], daidzein [204], glycitin [205], genistein [176], genistin [206], and epicatechin [95].

Karadeniz-Pekgöz et al. (2024) analyzed phenolic acids and flavonoids by HPLC–DAD in seeds of four Salvia species. Salvia potentillifolia was enriched with caffeic acid [79] (0.02 mg/mL), rosmarinic acid [1] (0.01 mg/mL), and quercetin [67] (0.09 mg/mL) were found in S. pisidica. Salvia cadmica was highly rich in caffeic acid [79] (0.01 mg/mL) and quercetin [67] (0.05 mg/mL). Ferulic acid [63] (0.01 mg/mL) and rutin [109] (0.02 mg/mL) were observed in S. hispanica.

Five classes of terpenoids were reported in Salvia species (Figure 3) (Nilofar et al., 2024). Sargazifar et al. (2024) mentioned in their study that abietane diterpenoids are the largest class of compounds in the Salvia genus. Out of the 545 known Salvia diterpenoids, 365 are abietane diterpenoids. Three 20,24-epoxydammarane triterpenes (santolin A, santolin B, and avinsl C [207–209]), two amyrin-type triterpenes (slavins A and B [210–211]), and a new ursane-type triterpene (santolinoic acid [212]) have been isolated and identified from S. santolinifolia. Another study by Maciel et al. (2022) reported the presence of diterpenes in Salvia species; 12-methoxy-carnosic acid [213] in S. repens Burch. ex. Benth and isoicetexone [214], icetexone [215] in S. uliginosa Benth. They also reported triterpenes (ursolic acid [78], oleanolic acid [186]) in S. cilicica Boiss.

FIGURE 3

Diversity of terpenoid classes reported in Salvia species.

Khouchlaa et al. (2021) evaluated the terpenoid profile of the petroleum ether extract of the roots of S. verbenaca. The distribution of compounds was as follows: roots having taxodione [216], horminone [217], and 613-hydroxy-7-acetoxyroyleanon [218]. The presence of epi-13-manool [156] and manool [219] was observed in leaves, β-caryophyllene [11] and caryophyllene oxide [46] in fruits, and stems enriched with camphor [48] and viridiflorol [54]. The main phenolic diterpenoids were methyl carnosate [220] and carnosic acid [89].

Krol et al. (2022) reported the presence of triterpenes (oleanolic acid [186], ursolic acid [78], uvaol [221]) and diterpenes (sageone [222], carnosol [88], 16-hydroxycarnosol [223], rosmadial [224]) in the aerial part of ethanol extracts of S. apiana. Different diterpenes were found in the acetone extract, such as 16-hydroxycarnosic acid [225], salvicanol [226], rosmanol [227], 7-epirosmanol [228], 16-hydroxycarnosol [223], 16-hydroxyrosmanol [229], and 16-hydroxy-7-methoxyrosmanol [230]. However, the composition of the leaf extract was diterpenes (carnosic acid [89], carnosol [88], 16-hydroxycarnosic acid [225]) and triterpenes (α-amyrin [184], oleanolic acid [186], ursolic acid [78]). Zhong et al. (2025) isolated and identified a new compound using different approaches, such as the HR-ESIMS, COSY, and NOESY experiments in conjunction with ECD analysis in S. substolonifera. The name of the compound is substolide H [74] and is a norditerpene lactone. Barhoumi et al. (2022) reported a total of 14 compounds from the aqueous methanol fraction of S. multicaulis, including a new abietane diterpene derivative identified as 2,20-dihydroxyferruginol [231].

Park et al. (2025) reported the presence of dihydrotanshinone I [76], cryptotanshinone [183], and tanshinone IIA [232] in the ethanol extract of S. miltiorrhiza at varying concentrations in different cultivars ranging from 32 to 272 mg/100 g. Hafez Ghoran et al. (2022) listed 106 unusual terpenoids from different Salvia species. They reported the presence of salvilymitol [233] and salvilymitone [234] in the acetone extract of the aerial parts of S. hierosolymitana. Pixynol [235] was found in the acetone extract of the roots of S. barrelieri. Amblyol [236] and amblyone [237] were identified in the acetone extract of the aerial parts of S. aspera. Russelliinosides [238] are reported from the dichloromethane extract of the aerial parts of S. russellii. Salvadione A [239] and salvadione B [240] were isolated from the n-hexane-soluble fraction of S. bucharica. The n-hexane extract from aerial parts of S. hydrangea was enriched with salvadione C [241], perovskone B [242], and hydrangenone [243]. A new norsesterterpene (C-17, C-18, C-19, and C-20 tetranorsesterterpene [244]) was isolated from the acetone extract of the aerial parts of S. sahendica.

3.1.2 Essential oils

Essential oils (EOs) contain VOCs of various functional groups (Levaya et al., 2025). EOs are a rich source of bioactive compounds and may contain up to 200 compounds (Pezantes-Orellana et al., 2024). Many Salvia species are known for their essential oils, which are primarily composed of four chemotypes, with sesquiterpenes being the most common, particularly β-caryophyllene [11] and germacrene D [8] (Asgarpanah, 2021). Monoterpenes in Salvia oils are: α-pinene [52], β-pinene [44], camphor [48], limonene [245], linalool [58], and borneol [246]. The chemical composition of the essential oil of S. rosmarinus from Italy is characterized mainly by monoterpene hydrocarbons (39.32%–40.70%) and oxygenated monoterpenes (36.08%–39.47%). Representative compounds are: 1,8-cineole [43], α-pinene [52], camphor [48], and β-caryophyllene [11] (Leporini et al., 2020). A total of 42 compounds were analyzed using GC-MS and GC-FID in the EOs of S. leucantha Cav. Six major compounds were: 6.9-guaiadiene [38] (19.14%), (E)-caryophyllene [39] (16.80%), germacrene D [8] (10.22%), (E)-β-farnesene [40] (10%), bicyclogermacrene [41] (7.52%), bornyl acetate [112] (14.74%), and α-pinene [52] (3.31%) (Villalta et al., 2021). The EOs reported in the leaves of S. hydrangea were found to be predominantly composed of spathulenol [42] (16.07%), 1,8-cineole [43] (13.96%), β-caryophyllene [11] (9.58%), β-pinene [44] (8.91%), and β-eudesmol [45] (5.33%). In comparison, the EOs obtained from the flowers were characterized by a high proportion of caryophyllene oxide [46] (35.47%), followed by 1,8-cineole [43] (9.54%), β-caryophyllene [11] (6.36%), β-eudesmol [45] (4.11%), caryophyllenol-II [47] (3.46%), and camphor [48] (3.33%) (Ghavam et al., 2020).

Gourich et al. (2022) examined the EOs composition of S. officinalis by GC-MS, which was extracted using hydrodistillation. It showed the presence of oxygenated monoterpenes and sesquiterpenes. The main constituents are 1,8-cineole [43] (16.8%), β-thujone [134] (15.9%), β-caryophyllene [11] (12.6%), and camphor [48] (11.7%). Other compounds with a composition of 7%–8% were: α-humulene [138], α-pinene [52], and viridiflorol [54]. Some minor compounds (camphene [62], α-thujone [50], limonene [245], and α-pinene [52]) were found, ranging between 1% and 3%. Rashwan et al. (2021) in another study, identified 39 components in the EOs of the S. officinalis aqueous extract. The main constituent was 9-octadecenamide [247] (55.8%), while other compounds were eucalyptol [130], trimethylsaline (TMS) derivatives of palmitic acid [31] and stearic acid [33], and other long-chain hydrocarbons and fatty acid derivatives in smaller amounts.

In line with these findings on S. officinalis, another study has also reported a consistent presence of oxygenated monoterpenes and sesquiterpenes as the main constituents of the EOs of S. officinalis. The principal compounds identified by GC-MS included naphthalenone [49], camphor [48], 1,8-cineole [43], α-pinene [52], camphene [62], isoborneol [248], and α-thujone [50] (Assaggaf et al., 2022). Similarly, in the Italian species of S. officinalis, camphor [48] (16.16%–18.92%), 1,8-cineole [43] (8.80%–9.86%), β-pinene [44] (3.08%–9.14%), camphene [62] (6.27%–8.08%), and α-thujone [50] (1.17%–9.26%) are identified as the most abundant constituents of EOs (Tundis et al., 2020). Similarly, α-thujone [50] (33.77%), β-caryophyllene [11] (12.28%), α-humulene [138] (12.19%), camphor [48] (11.52%), naphthalene [249] (9.94%), eucalyptol [130] (8.11%), α-pinene [52] (3.31%), β-pinene [44] (1.8%), β-myrcene [250] (1.49%), germacrene D [8] (1.36%), and borneol [246] (1.18%) were identified as the main components in other EOs of S. officinalis (Al-Mijalli et al., 2022).

A total of 60 compounds, accounting for 98.2% of the EOs composition, were identified in S. tomentosa. The predominant constituents included camphor [48] (9.35%), γ-muurolene [51] (8.37%), α-pinene [52] (7.59%), α-caryophyllene [251] (6.25%), viridiflorol [54] (5.13%), δ-cadinene [55] (5.01%), and terpinene-4-ol [56] (5.01%) (Koçer and İstifli, 2022). On the contrary, the EOs of S. sclarea were characterized mainly by linalool acetate [57] (49.1%) and linalool [58] (20.6%), with other notable components such as (E)-caryophyllene [39] (5.1%), p-cymene [59] (4.9%), α-terpineol [129] (4.9%), and geranyl acetate [61] (4.4%) (Kačániová et al., 2023). GC-MS analysis revealed the presence of 139 compounds in the EOs of 12 native Iranian Salvia species. Some of the common compounds reported in all samples were as follows: Linalool [58], α-terpineol [129], β-caryophyllene [11], spathulenol [42], and caryophyllene oxide [46]. The yield of EOs extracted from plants was also calculated in the range of 0.06%–0.96% w/w (Gharehbagh et al., 2023).

Alves-Silva et al. (2023) performed hydro distillation of S. aurea leaves and collected EOs. They studied the composition of EOs by GC-MS and GC-FID. Similar compounds were observed in the EOs of other Salvia species. The main components of EOs were: 1,8-cineole [43] (16.7%), β-pinene [44] (11.9%), α-thujone [50] (10.5%), camphor [48] (9.5%), and (E)-caryophyllene [39] (9.3%). Other compounds were limonene [245], viridiflorol [54], γ-muurolene [51], α-humulene [138], β-myrcene [250], and α-pinene [52].

3.1.3 Fatty acids

The fatty acid profiling of seven species of Salvia revealed the presence of compounds of therapeutic value. Dihydroxyoctadecadienoic acid [252] and 13-hydroxy-9,11-octadecadienoic acid [253] were observed in S. fruticosa by (Mróz and Kusznierewicz, 2023). Mokhtar et al. (2023) reported that out of the 17 compounds, palmitic acid [31] was the main fatty acid, followed by oleic acid [29], linoleic acid [86], stearic acid [33], eicosanoic acid [254], and dimethyl phthalate [255] in the petroleum ether extract of S. balansae. Abdel Ghani et al. (2023) reported that the GLC-MS analysis of the seed oil of S. hispanica L. showed a high concentration of omega-3 fatty acids, with a percentage of 35.64% of the total fatty acid content in the seed oil. The identified compounds were methyl esters of linoleic acid [86] (35.64%), α-linolenic acid [32] (23.95), palmitic acid [31] (14.12%), stearic acid [33] (7.63%), lauric acid [256] (5.87%), myristic acid [257] (2.31%), 11,14,17-eicosatrienoic acid [258] (0.59%), arachidic acid [259] (0.57%), caprylic acid [260] (0.54%) and capric acid [261] (0.42%).

Motyka et al. (2022) reported that the oil obtained from S. hispanica seeds accounts for 30%–33% of the fatty acids, of which 80% are essential fatty acids (EFAs) such as α-linolenic [32] and linoleic acid [86]. Chia seeds also contain the following sterols in small amounts: campesterol [262] (472 mg/kg), stigmasterol [263] (1,248 mg/kg), β-sitosterol [22] (2057 mg/kg), and stigmasta-5,24 (28)-dien-3β-ol (Δ5-avenasterol) [264] (355 mg/kg). Gebremeskal et al. (2024) analyzed the fatty acid composition of S. hispanica seed oil by GC-MS. α-linolenic acid [32] was found to be the main compound with a percentage of 62.65, and other compounds were linoleic acid [86] (19.27%), oleic acid [29] (7.47%), palmitic acid [31] (8.79%), stearic acid [33] (1.66%), and myristic acid [257] (0.16%). Karadeniz-Pekgöz et al. (2024) determined the fatty acid profile of seeds of Salvia species by GC-MS. Palmitic acid [31], stearic acid [33], oleic acid [29], and linoleic acid [86] were present in significant amounts in S. cadmica, S. caespitosa, S. pisidica, S. potentillifolia, and S. hispanica, with a maximum composition of linoleic acid [86] that was above 70% in all samples.

3.2 Pharmacological activities of the plant extracts of Salvia species

Sage plants have been used for centuries in the culinary, cosmetic, and fragrance industries. It is used to cure a wide range of ailments, including digestive, respiratory, renal, hepatic, neurological, cardiac, blood circulation, and metabolic disorders (Afonso et al., 2021). The Salvia genus contains flavonoids, phenolic acids, terpenoids, lipophilic diterpenoids, and tanshinone derivatives. The mentioned compounds exhibit antioxidant, antibacterial, anticancer, antimicrobial, anti-inflammatory, anti-dermatophyte, antiviral, antineoplastic, and anti-platelet aggregation properties, as shown in Figure 4 (Yilmaz et al., 2022; Zhumaliyeva et al., 2023). Salvia officinalis is an important medicinal and aromatic plant because of its bioactive components. These components are phenolics, terpenoids, polyphenols, and flavonoids. It has an anticancer, antimicrobial, and anti-inflammatory role (Poulios et al., 2020). Some of the Salvia species with potential pharmacological activities are listed in Table 3.

FIGURE 4

Pharmacological activity of some Salvia species.

TABLE 3

| Species | Plant part/Extract | Therapeutic potential | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| S. deserta Schangin | Roots/Ethylacetate | Antimicrobial, antileishmanial, and antithrombotic | Zhumaliyeva et al. (2023) |

| S. sclarea L | Leaves/EOs | Antioxidant, antibacterial | Stanciu et al. (2022) |

| S. verticillata L | Leaves/EOs | Improve liver fibrosis, cardio- and hepatoprotection, Alzheimer’s disease, antioxidant potential, anti-inflammatory, antibacterial, and antifungal activity | Ivanova et al. (2024) |

| S. officinalis L | Aerial/Aqueous | Photoprotective, antioxidant, and cytotoxic activity | Tsitsigianni et al. (2023), Akacha et al. (2024) |

| S. divinorum Epling and Játiva | Leaves/Aqueous | Psychoactive | Brito-da-Costa et al. (2021), Ertas et al. (2023) |

| S. absconditiflora Greuter & Burdet | Aerial/EOs | Antioxidant, cytotoxic, and antimicrobial | Demirpolat (2023) |

| S. verbenaca L | Leaves/decoction | Antidiabetic, antipyretic, wound healing, cure skin, digestive, and respiratory problems | Mrabti et al. (2022) |

| S. mirzayanii Rech f. and Esfand | Seeds/80% methanol | Antioxidant and antibacterial Gastrointestinal diseases, skin infections, spasms, inflammations, and weakness |

Hadkar and Selvaraj (2023), Shahraki et al. (2024) |

| S. chloroleuca Rech f. and Allen | Not available | Antibacterial, antitumoral, antiviral, antifungal, antiparasitic, antirheumatic, anticancer, and neuroprotective | Salimikia and Mirzania (2022) |

| S. nemorosa L | Aerial/80% ethanol | Antimicrobial, anticancer, and antioxidant | Luca et al. (2023) |

| S. miltiorrhiza Bunge | Herbal extract | Improve blood circulation, treat insomnia, abdominal and chest lumps, palpitations, and skin carbuncles | Nwafor et al. (2021), Huang et al. (2024) |

| S. aurea L. (S. africana-lutea L.) | Leaves/aqueous | Cold, flu, tuberculosis, headaches, fever, and chronic bronchitis | Ezema et al. (2024) |

| S. elegans Vahl | Aerial/ethyl acetate | Antihypertensive effect | Gutiérrez-Román et al. (2022) |

| S. hispanica L | Seeds/aqueous | Hypoglycemic, antimicrobial, anticancer, anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, antihypersensitive, anti-obesity, and cardioprotective properties | Amtaghri and Eddouks (2023), Ashish et al. (2022) |

| S. miltiorrhiza Bunge | Tanshinones | Antifibrotic, antitumor, and inflammatory, neuroprotection, and cardiovascular diseases | Shou et al. (2025) |

| S. aethiopis L | Aerial/aqueous | Anticancer and antioxidant | Tasheva et al. (2025) |

The therapeutic potential of various species of the genus salvia.

3.2.1 Antioxidant activity

Sage (S. officinalis) is a fragrant and medicinal herb well known for its pharmacological characteristics. DPPH, FRAP, and ABTS tests demonstrated that the best antioxidant activity of S. officinalis EOs was observed in the full flowering stage. IC50 values were 0.011 ± 3.29, 0.012 ± 2.17, and 0.014 ± 1.81 mg/mL for the DPPH, FRAP, and ABTS assays, respectively (Assaggaf et al., 2022). An antioxidant activity was found in a concentration-dependent manner for the EOs of the aerial parts of S. officinalis. The ABTS assay showed the highest radical scavenging with IC50 values of 20.64 μg/mL (Tundis et al., 2020). Another study by Al-Mijalli et al. (2022) analyzed the antioxidant activity of EOs from S. officinalis, and the reported results were significant. The IC50 values were 0.093 ± 2.17 mg/mL, 0.0112 ± 3.18 mg/mL, and 0.0129.74 ± 2.11 mg/mL for the DPPH, FRAP, and ABTS assays, respectively.

Piątczak et al. (2021) determined the antioxidant activities of hydromethanolic extracts of the aerial parts and root of S. cadmica. The aerial parts showed a strong antioxidant potential for DPPH with an IC50 value of 0.034 mg/mL. Onder et al. (2022) analyzed the antioxidant potential of the ethyl acetate extract from the aerial parts of S. absconditiflora, S. sclarea, and S. palaestina. Salvia absconditiflora showed significant antioxidant activity with a value of 251.39 mg TE/g extract using the DPPH assay. Mróz and Kusznierewicz (2023) showed the antioxidant activity of the 70% ethanol extract of S. fruticosa. It was found to be dose-dependent in the ABTS assay, as well as in the DPPH test. It is attributed to the presence of rosmarinic acid [1].

Abdel Ghani et al. (2023) studied that the dichloromethane fraction of the aerial parts of S. hispanica revealed antioxidant activity against the DPPH radical (IC50 = 0.014 mg/mL). This activity was approximately comparable to that of ascorbic acid [69] (IC50 = 0.012 mg/mL). Gebremeskal et al. (2024) reported that the chia seed extract with an ethanol concentration of 80% scavenged DPPH with a maximum inhibition percentage of 90%. This activity is attributed to the presence of a flavonoid content (1.08 ± 0.20 mg QE/g extract). Akrimi et al. (2025) analyzed the antioxidant activity of the hexane extract of S. officinalis. The lowest IC50 value of 0.03 mg/mL was observed by the DPPH assay and a similar trend was shown for the FRAP assay, with the reducing power of EC50 = 0.17 mg/mL. An increased antioxidant activity of S. mirzayanii was observed after treatment with elicitors (salicylic acid [105] and yeast extract) (Shahraki et al., 2024).

Karadeniz-Pekgöz et al. (2024) reported that the methanol extract of S. pisidica showed a significant DPPH radical scavenging activity with an IC50 value of 0.0182 mg/mL, and it is attributed to the presence of TPC of 0.0176 mg/mL GAE. Tsakni et al. (2025) showed that the leaf extract of S. rosmarinus demonstrated promising antioxidant activity with the IC50 value of 0.0129 mg/mL. It is attributed to the synergistic effect of phenolic acids such as rosmarinic acid [1], benzoic acid [66], and vanillic acid [64].

3.2.2 Anti-inflammatory properties

Assaggaf et al. (2022) showed that S. officinalis EO at the full flowering stage exhibits the best anti-inflammatory activity with an IC50 value of 0.092 ± 0.03 mg/mL, while quercetin [67] activity was IC50 = 0.048 ± 0.02 mg/mL. Righi et al. (2021) showed that the hydromethanolic extract of S. verbenaca exhibited a strong anti-lipid peroxidation effect with an IC50 value of 0.011 mg/mL. Similarly, Abdel Ghani et al. (2023) reported that the dichloromethane fraction of S. hispanica L. showed stronger anti-inflammatory activity with IC50 of 0.061 mg/mL compared to diclofenac sodium as a positive control, with an IC50 of 0.0179 mg/mL. This activity is attributed to the presence of diterpenes and phenolics in the dichloromethane fraction. Sterols, such as β-sitosterol [22], betulinic acid [265], oleanolic acid [186], and β-sitosterol-3-O-β-D-glucoside [25], are also known to exhibit anti-inflammatory activity.

3.2.3 Antimicrobial properties

Essential oils from Salvia species, particularly those containing thujones and eucalyptol, exhibit antibacterial and antifungal properties. EOs from leaves and flowers of S. hydrangea showed a significant inhibitory effect on the Gram-negative bacterial species: Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Shigella dysenteriae, and K. pneumoniae, with a minimum inhibitory concentration of 16–62 μg/mL (Ghavam et al., 2020). Kačániová et al. (2023) reported the strong effects of S. sclarea EOs compared to the standard (33 mm) for the Gram bacterial strain, Bacillus subtilis (12 ± 1.00 mm), and the yeast, C. albicans (11.33 ± 0.58 mm). Taking into account the strains of fungi, the strongest activity of the tested EOs was observed toward Aspergillus flavus with an inhibition zone of 10.33 ± 0.58 mm. Piątczak et al. (2021) showed that the roots of S. cadmica demonstrated antimicrobial activity. They noticed it against two species of Candida and several Gram-positive bacteria, including Bacillus cereus and four strains of Staphylococcus spp. Demirpolat (2023) reported that the EOs of Salvia species showed varying antimicrobial activity. Promising antibacterial results against Escherichia coli and Bacillus megaterium were observed by using S. multicaulis. Furthermore, the EOs of S. verbenaca and S. ceratophylla were active against K. pneumoniae and Staphylococcus aureus, respectively. The active Salvia species against Candida albicans and Candida glabrata were S. verbenaca and S. multicaulis, with an inhibition zone of 25–28 mm, respectively.

Balaei-Kahnamoei et al. (2021) reported in their study that S. aureus and E. coli were inhibited by the chloroform fraction of aerial parts of S. macrosiphon. The MIC was 0.6 mg/mL for both strains. Sargazifar et al. (2024) studied that aegyptinone A [82], present in the root extract of S. santolinifolia showed moderate antibacterial activity against S. aureus, Staphylococcus epidermis, and B. subtilis with a MIC of 25 μg/mL. Karadeniz-Pekgöz et al. (2024) reported the anti-bacterial activity of a 10 mg/mL concentration of chia seed methanol extract. They found efficiency against strains of S. aureus, S. enterica, and L. monocytogenes. Bilginoğlu et al. (2025) observed the inhibition zones (15–20 mm) presenting the antimicrobial activity of the ethanol extract of S. aethiopis at a concentration of 4 mg/mL. Promising results were observed against these bacterial strains: S. epidermidis, Micrococcus luteus, B. cereus, Listeria monocytogenes, K. pneumoniae, S. dysenteriae, and C. albicans.Akrimi et al. (2025) analyzed that the hexane extract of S. officinalis demonstrated the greatest antibacterial effect against S. epidermidis and S. aureus (MIC = 0.156 mg/mL), and the authors reported that it is due to the presence of rosmarinic acid [1] as the main component.

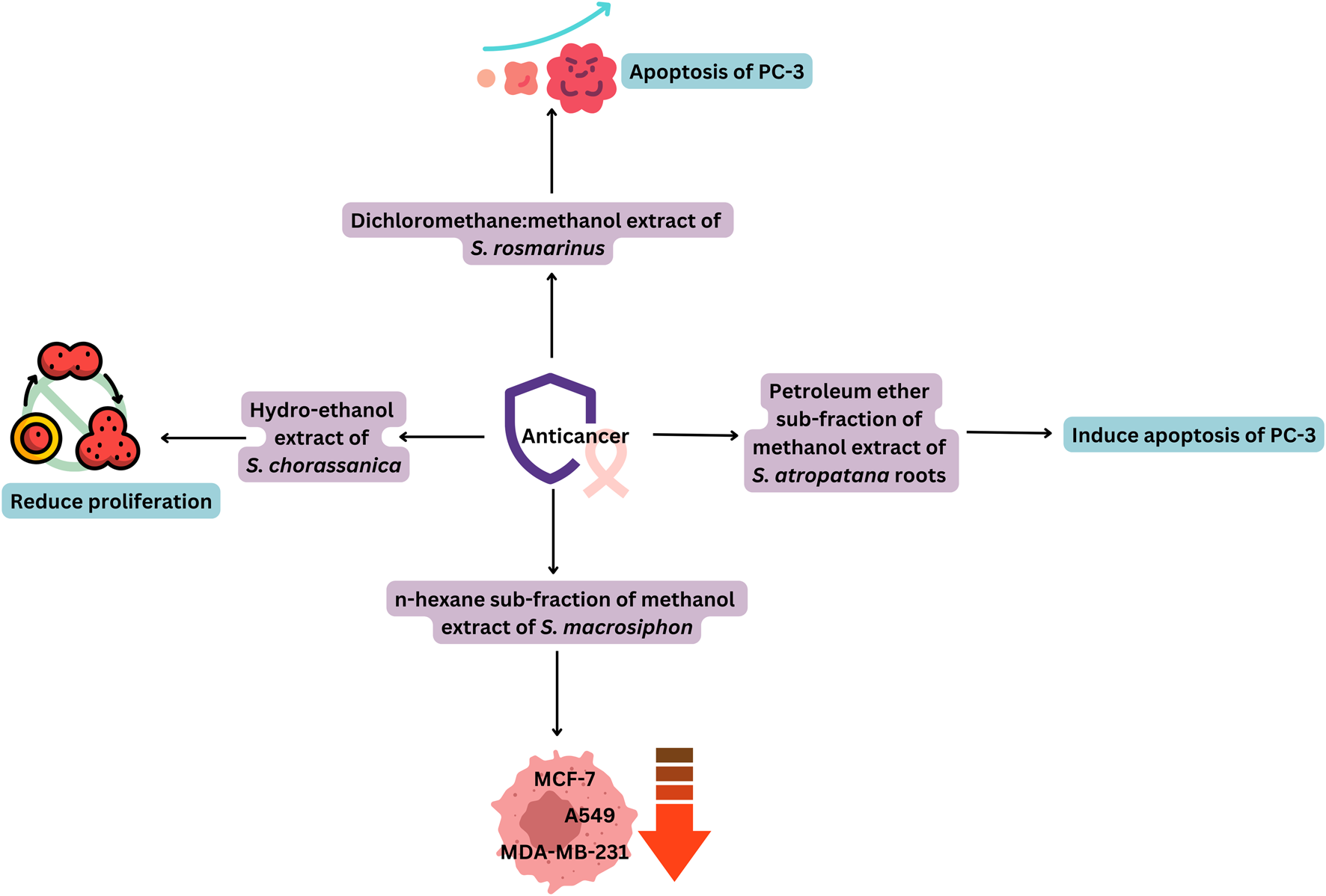

3.2.4 Anticancer potential

Extracts of some Salvia spp. or their phytochemicals have shown the potential to inhibit carcinogenesis, proliferation, and metastasis of cancer cells (Table 4), while causing minimal damage to normal cells. The anticancer activity of the extracts was quite effective, since it showed results similar to reference anticancer drugs (Figure 5) (Ezema et al., 2022). Deng et al. (2020) identified different tanshinones in S. miltiorrhiza, including dihydrotanshinone I [76], cryptotanshinone [183], tanshinone I [182], and tanshinone IIA [232]. These compounds exhibit a variety of pharmacological activities, including antitumor, anti-inflammatory, and antibacterial effects. A similar study by Zhao et al. (2022) showed that S. miltiorrhiza is enriched with liposoluble tanshinones (dihydrotanshinone I [76], tanshinone I [182], tanshinone IIA [232], and cryptotanshinone [183]) and water-soluble phenolic acids (salvianolic acid A [167], salvianolic acid B [168], salvianolic acid C [146], and rosmarinic acid [1]). These compounds target breast cancer cells by altering the mechanisms such as: induction of apoptosis, autophagy, and cell cycle arrest, anti-metastasis, formation of cancer stem cells, and potentiation of antitumor immunity.

TABLE 4

| Plant species | Isolated phytochemical | Cancer cells | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| S. tebesana Bunge | Aegyptinone A [82], tebesinone B [266] | Michigan Cancer Foundation-7 (MCF-7), melanoma, human prostate (PC-3), and colon (C26) carcinoma | Ezema et al. (2022) |

| S. lachnocalyx Hedge | Ferruginol [75], taxodione [216], sahandinone [267], 4-dehydrosalvilimbinol [268], and labda-7,14-dien-13-ol [269] | Acute lymphoblastic leukemia, colorectal adenocarcinoma, and MCF-7 | Mirzaei et al. (2017) |

| S. lachnocalyx Hedge | 15-deoxyfuerstione [270], horminone [217], microstegiol [271], and 14-deoxycoleon U [272] | Human Erythroleukemia (K562) and MCF-7 | Mirzaei et al. (2020) |

| S. hispanica L | Chrysin [273] | Ovarian Clear Cell Carcinoma (ES2) and Ovarian Papillary Serous Adenocarcinoma (OV90) | Lim et al. (2018), Lima et al. (2020), Çelik et al. (2024) |

Cellular targets of anticancer phytochemicals from Salvia species.

FIGURE 5

Promising anticancer activity of Salvia extracts.

Piątczak et al. (2021) reported that the 10 mg/mL concentration of root extract of S. cadmica showed a 70% reduction in cell viability against mouse L929 fibroblasts in the MTT assay (Righi et al., 2021). showed the potential cytotoxic effect of the hydromethanolic extract of S. verbenaca against Artemia salina larvae with an LC50 value of 0.030 mg/mL. Abdel Ghani et al. (2023) studied that the dichloromethane fraction of aerial parts of S. hispanica revealed moderate cytotoxic activity against the human lung cancer cell line (A-549), human prostate carcinoma (PC-3), and colon carcinoma (HCT-116) with IC50 values of 0.035 ± 2.1, 0.042 ± 2.3, and 0.047 ± 1.3 mg/mL, respectively.

The n-hexane fraction of S. macrosiphon was found to be potent for the lung cancer cell line (A-549), two human breast cancer cell lines (MCF-7 and MDA-MB-231), and normal cells (Human Dermal Fibroblast). The tested sample exhibited cytotoxicity with IC50 values of 0.02, 0.01, 0.02, and 0.02 mg/mL, respectively. A compound (3-epi manoyl oxide [35]) of S. macrosiphon was found to be potent against MCF-7 with an IC50 value of 15.79 ± 0.35 µM, and it showed stronger activity than etoposide (37.51 ± 0.66 µM). It also showed less toxicity toward HDF, confirming that it could be considered a potent candidate in the research and development of anticancer drugs (Balaei-Kahnamoei et al., 2021). The ethyl acetate extract of chia seeds showed a potent cytotoxic effect against liver cancer cell lines (HepG2) and pancreatic cancer (MIA PaCa-2) in humans, with an IC50 of 0.011 mg/mL and 0.0877 mg/mL, and a percentage of cytotoxicity at 0.01 mg/mL of 98% and 56.2%, respectively. According to considerations from the United States National Cancer Institute (NCI), a crude extract is assumed to be a promising anticancer agent if its IC50 value ranges between 0.03 and 0.04 mg/mL. Based on these observations, it can be assumed that all Salvia extracts reported could be a promising source for the development of an anticancer drug (Mohamed et al., 2024).

The S. officinalis propylene glycol extract revealed oncostatic properties in vitro and in vivo due to the presence of phenolics (rosmarinic acid [1], protocatechuic acid [118], and salicylic acid [105]) and triterpenoids (ursolic acid [78] and oleanolic acid [24]) (Kubatka et al., 2024). The diterpenoids present in the roots of S. leriifolia were purified and identified by HPLC and NMR. Then, the effect of these compounds on the cell viability of different cell lines: MIA PaCa-2, Human Gastric Cancer Cell Line (AGS), MCF-7, Human Immortalized Keratinocytes (HaCaT), and cervical cancer cells (HeLa), was evaluated by the MTT method. The diterpene pisiferal has high cytotoxicity against all investigated cell lines at a concentration between 9.3 ± 0.6 and 14.38 ± 1.4 μM (Sarhadi et al., 2022). The dichloromethane extract from S. compressa shoots showed moderate activity against MCF-7 and reduced cell viability to 68.2% ± 13.1% at a concentration of 0.05 mg/mL (Noorbakhsh et al., 2022). The viability of non-small cell lung cancer cells was significantly affected when treated with the ethanol extract of S. aethiopis at a concentration of 0.02 mg/mL, and cell viability was observed as 6.40% and 8.52% after 24 and 48 h of treatment. The IC50 values were reported as 0.08 and 0.05 mg/mL, respectively (Bilginoğlu et al., 2025).

3.2.5 Neuroprotective effects

Different disorders of the central nervous system affect 22% of the human population worldwide. To cope with depression, drugs are used that work to modify one or more monoamine neurotransmitter systems. Different Salvia species are used to enhance memory, as a sedative, and for the treatment of headaches (Abdelhalim and Hanrahan, 2021). The enzymes acetylcholinesterase (AChE) and butyrylcholinesterase (BChE) are considered to be primary cholinesterase regulators. Inhibition of cholinesterase (ChE) is the most effective treatment approach for Alzheimer’s disease (AD) to date. In a normal brain, AChE represents 80% of the activity, while BuChE represents the remaining 20%. AD is characterized by an increase in the level of BuChE, while AChE activity remains unchanged or declines. Selective inhibition of BuChE is a strategy to improve memory in elderly rats (Villalta et al., 2021). Sefah et al. (2025) studied the hydroethanolic leaf extract of S. officinalis and found that it improves memory and alleviates lipopolysaccharide-induced neuroinflammation in mice.

Tundis et al. (2020) reported significant activity of S. officinalis EO against AChE. Samples confirmed a slight difference in activity based on locality, as the IC50 values of 0.0476 and 0.0583 mg/mL were shown by samples from Orsomarso and Civita regions, respectively. Ertas et al. (2023) enlisted the neuroprotective effect of different Salvia species (Figure 6). The study reported that capsules containing 0.05 mL of S. lavandulaefolia EOs resulted in increased performance of secondary memory and attention tasks. A single dose of S. lavandulaefolia essential oil has been found to improve memory and attention task performance, increase alertness, and reduce mental fatigue during the long-term performance of difficult tasks. Similarly, the ethanolic extract (70%) of dried leaves of S. officinalis demonstrated significant improvements in the memory scores. Gharehbagh et al. (2023) studied that the EOs of aerial parts of S. mirzayanii were a potent inhibitor of AChE and BChE at a concentration of 0.05 mg/mL, with an inhibition of 72.68% and 40.6%, respectively. Ivanova et al. (2024) collected data on the neuroprotective effect of S. verticillata. They concluded that S. verticillata could be used as an adjunctive therapy in neurodegenerative diseases, including Alzheimer’s disease, due to the presence of monoterpenes, phenolic diterpenes, quercetin [67], and rosmarinic acid [1].

FIGURE 6

Neuroprotective effects of some Salvia species.

3.2.6 Anti-diabetic activity

The EOs distilled from S. officinalis in the full flowering stage showed antidiabetic activity. IC50 values were 0.069, 0.022, and 0.037 mg/mL against α-amylase, α-glycosidase, and lipase, respectively (Assaggaf et al., 2022). The in vitro inhibitory effects of S. officinalis (EOs) on α-amylase and α-glucosidase were significant, with IC50 values of 0.081 and 0.011 mg/mL (Al-Mijalli et al., 2022). Salvia hispanica shows a reduction in insulin resistance that is attributed to the omega-3 content (35.64% of total fatty acids). Similarly, the dichloromethane fraction inhibited the α-amylase enzyme with an IC50 of 0.067 mg/mL (Abdel Ghani et al., 2023). Salvia spinosa was found to be a potent inhibitor (90.5% inhibition at 0.05 mg/mL) of α-glucosidase (Gharehbagh et al., 2023). Shojaeifard et al. (2023) analyzed α-glucosidase inhibitory activity of 80% MeOH extract from different Salvia species. At a concentration of 0.01 mg/mL, S. santolinifolia (94.35%), S. multicaulis (94.27%), and S. eremophila (94.02%) showed significant inhibitory activity compared to acarbose (87.88%). However, S. nemorosa showed 70% activity, while S. verticillata did not show significant activity. Several compounds: rosmarinic acid [1], carnosic acid [89], carnosol [88], luteolin [5], apigenin [6], and hispidulin [106] are believed to be the modulators of the proposed activity.

3.2.7 Other activities

Abdel Ghani et al. (2023) analyzed the anti-obesity activity of S. hispanica using a pancreatic lipase inhibitory assay. The dichloromethane fraction has moderate activity with an IC50 of 0.059 mg/mL compared to orlist (IC50 of 0.023 mg/mL). Vestuto et al. (2024) performed LC-MS analyses on the extracellular vesicles of hairy roots of S. sclarea and S. dominica. It highlighted the presence of ursolic acid [78] and oleanolic acid [24] derivatives. These compounds have already shown antibacterial, antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, antineoplastic, and anti-aggregant properties, along with neuroprotective effects. Kong et al. (2023) presented different mechanisms by which S. miltiorrhiza effectively attenuates the symptoms of Placenta-mediated pregnancy complications. In particular, S. miltiorrhiza and its active compounds have been shown to treat preeclampsia, mitigate the severity of fetal growth restriction, and improve adverse symptoms of spontaneous recurrent abortion. Jedidi et al. (2023) reported that the aqueous extract of S. officinalis flowers has protective effects against hepatorenal toxicities.

The administration of ethanol extract of aerial parts of S. chudaei effectively reversed the adverse effects of triton-induced hyperlipidemia. It significantly lowers cholesterol, triacylglycerol, and LDL levels. A positive effect was observed as the HDL cholesterol improved. It also enhanced antioxidant defenses and reduced markers of oxidative stress, demonstrating its protective role against metabolic dysfunction. HPLC confirmed the presence of bioactive compounds in the extract that contribute to these benefits (Tlili et al., 2025). Park et al. (2025) reported the potential to reduce inflammation of the ethanol extract of S. miltiorrhiza. Inflammation in RAW 264.7 macrophages was reduced by 0.08 mg/mL of ethanol extract of S. miltiorrhiza.

Akrimi et al. (2025) assessed the inhibitory effect of S. officinalis hexane extract on methicillin-resistant S. aureus. The concentration of 0.156 mg/mL caused a 70% inhibition of the biofilm. Therefore, the extract can improve food safety by interrupting the bacterial biofilm production process. Tsakni et al. (2025) analyzed the antiviral activity of S. rosmarinus leaf extract in HuhD-2 cell cultures infected with dengue virus and discovered that it has the potential for the development of antiviral drugs. Alves-Silva et al. (2023) reported the wound healing power of S. aurea by promoting cell migration without affecting cell viability. Huang et al. (2024) showed that S. miltiorrhiza is listed as a “top-tier” herb (a TCM that does not have observable toxicity) in the Sheng Nong’s Herbal Classic.

4 Conclusion

The potential anti-inflammatory, antibacterial, antioxidant, and neuroprotective abilities of Salvia species are well-studied and confirmed. It is ensured by the presence of bioactive compounds. As some species are quite popular and well-studied for their chemical profile and bioactivities, a few are least studied, leaving room for further evaluation. The present review provided recent studies on the 59 Salvia species reported during 2020–2025. It is observed that the variability in the chemical composition of Salvia can lead to significant variation in its bioactivity. There are some other factors affecting the chemical composition, such as: extraction method, plant part, solvent, and freshness of the sample. The high content of flavonoids, terpenoids, and phenolic compounds in the Salvia species is promising. It indicates the prospects for further study of these species for the pharmaceutical industry.

5 Future perspectives

Deep characterization of Salvia compounds along with the analysis of their ADMIT properties. Molecular Docking studies will help elucidate the molecular interaction of the compound with the receptor cell. Therefore, we can predict the binding properties and their effectiveness in curing the disease and the mechanism by which it copes. The scope of studies can be improved and optimized by considering multiple and advanced methods to ensure accuracy. It will be helpful in improving the wellness of healthcare, cosmetics, and other industries associated with natural products.

Statements

Author contributions

TA: Writing – original draft, Data curation, Conceptualization, Visualization, Writing – review and editing. JP: Formal Analysis, Validation, Writing – review and editing, Writing – original draft, Supervision. JL: Supervision, Formal Analysis, Writing – review and editing, Writing – original draft, Conceptualization, Methodology, Investigation, Validation.

Funding

The authors declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. The article is part of a PhD dissertation title ‘Chemotaxonomy and Chemical Profiling of a selected group of plants with particular emphasis on Lamiaceae family’, prepared during Doctoral School at the Wrocław University of Environmental and Life Sciences. The APC/BPC is financed/co-financed by Wrocław University of Environmental and Life Sciences.

Acknowledgments

The article is part of a PhD dissertation titled ‘Chemotaxonomy and Chemical Profiling of a selected group of plants with particular emphasis on Lamiaceae family’, prepared during the Doctoral School at the Wrocław University of Environmental and Life Sciences. The authors are thankful to Prof. Hab. Iwona Gruss, Department of Plant Protection, Wrocław University of Environmental and Life Sciences, Poland, for the valuable suggestions and help in the writing process of this review article.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The authors declare that no Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Correction note

This article has been corrected with minor changes. These changes do not impact the scientific content of the article.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Glossary

- EOs

Essential Oils

- WFO

World Flora Online

- UPLC-DAD

Ultra Performance Liquid Chromatography-Diode Array Detector

- ESI-MS/MS

Electrospray Ionization Tandem Mass Spectrometry

- HPLC-DAD

High Performance Liquid Chromatography-Diode Array Detector

- GC-MS

Gas Chromatography- Mass Spectrometry

- LC-Q-Orbitrap

Liquid Chromatography coupled with a Quadrupole-Orbitrap

- HRMS

High Resolution Mass Spectrometry

- GLC-MS

Gas Liquid Chromatography- Mass Spectrometry

- CC

Column Chromatography

- TLC

Thin Layer Chromatography

- NMR

Nuclear Magnetic Resonance

- GC-FID

Gas Chromatography- Flame Ionization Detector

- FTIR

Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy

- HRESIMS

High-Resolution Electrospray Ionization Mass Spectrometry

- 1D and 2D

One-Dimensional and Two-Dimensional

- UPLC-qToF-MS

Ultra-Performance Liquid Chromatography coupled with Quadrupole Time-of-Flight Mass Spectrometry

- LC-MS/MS

Liquid Chromatography- Tandem Mass Spectrometry

- LC-ESI-MS

Liquid Chromatography- Electrospray Ionization Mass Spectrometry

- HS-SPME

Headspace Solid-Phase Microextraction

- VOCs

Volatile Organic Constituents

- TMS

Tetramethylsilane

- RE

Rutin Equivalent

- GAE

Gallic Acid Equivalent

- TPC

Total Phenolic Content

- TFC

Total Flavonoid Content

- DW

Dry Weight

- mg/g

milligrams per Gram

- mg/mL

milligrams per milliliter

- COSY

Correlated Spectroscopy

- NOESY

Nuclear Overhauser Effect Spectroscopy

- ECD

Electron Capture Detector

- EFAs

Essential Fatty Acids

- DPPH

2,2-Diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl

- FRAP

Ferric Reducing Antioxidant Power

- ABTS

2,2′-azino-bis(3-ethylbenzothiazoline-6-sulfonic acid)

- IC50

Half-maximal Inhibitory Concentration

- EC50

Half Maximal Effective Concentration

- LC50

Median Lethal Concentration

- TE

Trolox Equivalent

- QE

Quercetin Equivalent

- MIC

Minimum Inhibitory Concentration

- mg/kg

Milligram per kilogram

- µM

Micromolar

- MCF-7

Michigan Cancer Foundation-7

- PC3

Human Prostate Carcinoma Cells

- C26

Colon Carcinoma Cells

- K562

Human Erythroleukemia Cells

- ES2

Ovarian Clear Cell Carcinoma Cells

- OV90

Ovarian Papillary Serous Adenocarcinoma Cells

- MTT

3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide

- L929

Mouse Fibroblast Cell Line

- MDA-MB-231

MD Anderson-Metastatic Breast-231

- HDF

Human Dermal Fibroblast

- HepG2

Human Liver Hepatoblastoma

- MIA PaCa-2

Human Pancreatic Cancer Cell Line

- AGS

Human Gastric Cancer Cell Line

- HaCaT

Human Immortalized Keratinocytes

- HeLa

Cervical Cancer Cells

- AD

Alzheimer’s disease

- AChE and BChE

Acetylcholinesterase and Butyrylcholinesterase

- ChE

Cholinesterase

- LDL and HDL

Low-Density Lipoprotein and High-Density Lipoprotein

- TCM

Traditional Chinese Medicine

- ADMET

Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism, Excretion, and Toxicity

- UHPLC-HRMS

Ultra-High-Performance Liquid Chromatography–High-Resolution Mass Spectrometry

References

1

Abd Rashed A. Rathi D.-N. G. (2021). Bioactive components of salvia and their potential antidiabetic properties: a review. Molecules26, 3042. 10.3390/molecules26103042

2

Abdel Ghani A. E. Al-Saleem M. S. Abdel-Mageed W. M. AbouZeid E. M. Mahmoud M. Y. Abdallah R. H. (2023). UPLC-ESI-MS/MS profiling and cytotoxic, antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, antidiabetic, and antiobesity activities of the non-polar fractions of Salvia hispanica L. aerial parts. Plants12, 1062. 10.3390/plants12051062

3

Abdelhalim A. Hanrahan J. (2021). Biologically active compounds from lamiaceae family: central nervous system effects. Stud. Nat. Prod. Chem.68, 255–315. 10.1016/B978-0-12-819485-0.00017-7

4

Afonso A. F. Pereira O. R. Cardoso S. M. (2021). Salvia species as nutraceuticals: focus on antioxidant, antidiabetic and anti-obesity properties. Appl. Sci.11, 9365. 10.3390/app11209365

5

Aissaoui M. Chalard P. Figuérédo G. Marchioni E. Zao MintJe Z. M. Benayache F. et al (2014). Chemical composition of the essential oil of Salvia verbenaca (L.) briq. ssp. Pseudo-jaminiana. Available online at: https://www.cabidigitallibrary.org/doi/full/10.5555/20143419107 (Accessed November 2, 2025).

6

Akacha B. B. Kačániová M. Mekinić I. G. Kukula-Koch W. Koch W. Orhan I. E. et al (2024). Sage (Salvia officinalis L.): a botanical marvel with versatile pharmacological properties and sustainable applications in functional foods. South Afr. J. Bot.169, 361–382. 10.1016/j.sajb.2024.04.044

7

Akrimi H. Jerbi A. Elghali F. Mnif S. Aifa S. Fki L. et al (2025). Investigation of the bioactive properties of Tunisian sage extracts: a detailed analysis of phytochemical composition and their antioxidant, antibacterial, and antibiofilm activities. Chem. Afr.8, 1351–1363. 10.1007/s42250-025-01240-0

8

Al-Mijalli S. H. Assaggaf H. Qasem A. El-Shemi A. G. Abdallah E. M. Mrabti H. N. et al (2022). Antioxidant, antidiabetic, and antibacterial potentials and chemical composition of Salvia officinalis and Mentha suaveolens grown wild in Morocco. Adv. Pharmacol. Pharm. Sci.2022, 2844880. 10.1155/2022/2844880

9

Ali M. Muhammad A. Lin Z. He H. Zhang Y. (2024). Exploring Lamiaceae-derived bioactive compounds as nature’s arsenal for sustainable pest management. Phytochem. Rev.24, 1989–2013. 10.1007/s11101-024-09987-z

10

Alves-Silva J. M. Maccioni D. Cocco E. Gonçalves M. J. Porcedda S. Piras A. et al (2023). Advances in the phytochemical characterisation and bioactivities of Salvia aurea L. Essential Oil. Plants12, 1247. 10.3390/plants12061247

11

Al‐Jaber H. I. Obeidat S. M. Afifi F. U. Abu Zarga M. H. (2020). Aroma profile of two populations of Salvia verbenaca collected from two bio‐geographical zones from Jordan. Chem. Biodivers.17, e1900553. 10.1002/cbdv.201900553

12

Amtaghri S. Eddouks M. (2023). Ethnopharmacology, nutritional value, therapeutic Effects,Phytochemistry, and toxicology of Salvia hispanica L.: a review. Curr. Top. Med. Chem.23, 2621–2639. 10.2174/0115680266248117230922095003

13

Anbessa B. Lulekal E. Hymete A. Debella A. Debebe E. Abebe A. et al (2024). Ethnomedicine, antibacterial activity, antioxidant potential and phytochemical screening of selected medicinal plants in Dibatie district, Metekel zone, western Ethiopia. BMC Complement. Med. Ther.24, 199. 10.1186/s12906-024-04499-x

14

Asgarpanah J. (2021). A review on the essential oil chemical profile of Salvia genus from Iran. Nat. Volatiles Essent. Oils8, 1–28. 10.37929/nveo.852794

15

Ashish A. Das S. Mazumder A. (2022). Ethnopharmacological importance of Salvia hispanica L.: an herbal panacia. Int. J. Health Sci.6, 5949–5963. 10.53730/ijhs.v6ns5.10007

16

Ashraf M. V. Khan S. Misri S. Gaira K. S. Rawat S. Rawat B. et al (2024). High-altitude medicinal plants as promising source of phytochemical antioxidants to combat lifestyle-associated oxidative stress-induced disorders. Pharmaceuticals17, 975. 10.3390/ph17080975

17

Askari S. F. Avan R. Tayarani-Najaran Z. Sahebkar A. Eghbali S. (2021). Iranian Salvia species: a phytochemical and pharmacological update. Phytochemistry183, 112619. 10.1016/j.phytochem.2020.112619

18

Assaggaf H. M. Naceiri Mrabti H. Rajab B. S. Attar A. A. Alyamani R. A. Hamed M. et al (2022). Chemical analysis and investigation of biological effects of Salvia officinalis essential oils at three phenological stages. Molecules27, 5157. 10.3390/molecules27165157

19

Balaei-Kahnamoei M. Eftekhari M. Ardekani M. R. S. Akbarzadeh T. Saeedi M. Jamalifar H. et al (2021). Phytochemical constituents and biological activities of Salvia macrosiphon Boiss. BMC Chem.15, 4. 10.1186/s13065-020-00728-9

20

Barhoumi L. M. Al-Jaber H. I. Abu Zarga M. H. (2022). A new diterpene and other constituents of Salvia multicaulis from Jordan. Nat. Prod. Res.36, 4921–4928. 10.1080/14786419.2021.1912745

21

Belloum Z. Chalard P. Figuérédo G. Marchioni E. Zao M. Benayache F. et al (2014). Chemical composition of the essential oil of Salvia verbenaca (L.) Briq. ssp. clandestina (L.) Pugsl. Available online at: https://www.cabidigitallibrary.org/doi/full/10.5555/20143419098 (Accessed October 24, 2025).

22

Bilginoğlu E. Kızıl H. E. Öğütcü H. Ağar G. Bağcı Y. (2025). Pharmacological potential and bioactive components of wild anatolian sage (Salvia aethiopis L.). Food Sci. Nutr.13, e70118. 10.1002/fsn3.70118

23

Bingol Z. Kızıltaş H. Gören A. C. Kose L. P. Topal M. Durmaz L. et al (2021). Antidiabetic, anticholinergic and antioxidant activities of aerial parts of shaggy bindweed (Convulvulus betonicifolia Miller subsp.)–profiling of phenolic compounds by LC-HRMS. Heliyon7, e06986. 10.1016/j.heliyon.2021.e06986

24

Bjørklund G. Cruz-Martins N. Goh B. H. Mykhailenko O. Lysiuk R. Shanaida M. et al (2024). Medicinal plant-derived phytochemicals in detoxification. Curr. Pharm. Des.30, 988–1015. 10.2174/1381612829666230809094242

25

Bojan L. Tripon M. Huiban F. Camen D. Sokolovic M. Tulcan C. (2024). Biochemical potential of Salvia sclarea L.: in vitro cultivation and chemical profiling approaches. J. Hortic. For. Biotechnol.28, 349–354.

26

Brito-da-Costa A. M. Dias-da-Silva D. Gomes N. G. Dinis-Oliveira R. J. Madureira-Carvalho Á. (2021). Pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of salvinorin A and Salvia divinorum: clinical and forensic aspects. Pharmaceuticals14, 116. 10.3390/ph14020116

27

Çelik Ş. Dervişoğlu G. İzol E. Sęczyk Ł. Özdemir F. A. Yilmaz M. E. et al (2024). Comprehensive phytochemical analysis of Salvia hispanica L. callus extracts using LC–MS/MS. Biomed. Chromatogr.38, e5975. 10.1002/bmc.5975

28

Cristani M. Micale N. (2024). Bioactive compounds from medicinal plants as potential adjuvants in the treatment of mild Acne vulgaris. Molecules29, 2394. 10.3390/molecules29102394

29

Dabaghian F. Aalinezhad S. Delnavazi M. R. Saeedi M. (2025). Salvia aristata essential oil: chemical composition, cholinesterase inhibition, and neuroprotective effects against oxidative stress in PC12 cells. Res. J. Pharmacogn.12, 65–75.

30

Dejene M. Dekebo A. Jemal K. Murthy H. C. A. Reddy S. G. (2025). Phytochemical screening and evaluation of anti-oxidant, anti-inflammatory and anticancer activities of leaves of Vernonia amygdalina, Otostegia integrifolia, and Salvia rosmarinus. Green Chem. Lett. Rev.18, 2438069. 10.1080/17518253.2024.2438069

31

Dembińska K. Shinde A. H. Pejchalová M. Richert A. Swiontek Brzezinska M. (2025). The application of natural phenolic substances as antimicrobial agents in agriculture and food industry. Foods14, 1893. 10.3390/foods14111893

32

Demirpolat A. (2023). Essential oil composition analysis, antimicrobial activities, and biosystematic studies on six species of Salvia. Life13, 634. 10.3390/life13030634

33

Deng C. Shi M. Fu R. Zhang Y. Wang Q. Zhou Y. et al (2020). ABA-responsive transcription factor bZIP1 is involved in modulating biosynthesis of phenolic acids and tanshinones in Salvia miltiorrhiza. J. Exp. Bot.71, 5948–5962. 10.1093/jxb/eraa295

34

Deshmukh V. P. (2022). Phytochemistry and Pharmacology of Salvia officinalis L.: a review. Bioact. Pharmacol. Med. Plants, 339–358. 10.1201/9781003281702-27

35

Ertas A. Yigitkan S. Orhan I. E. (2023). A focused review on cognitive improvement by the genus Salvia L.(Sage)—From ethnopharmacology to clinical evidence. Pharmaceuticals16, 171. 10.3390/ph16020171

36

Esmaeili G. Fatemi H. Baghani avval M. Azizi M. Arouiee H. Vaezi J. et al (2022). Diversity of chemical composition and morphological traits of eight Iranian wild Salvia species during the first step of domestication. Agronomy12, 2455. 10.3390/agronomy12102455

37

Ezema C. A. Ezeorba T. P. C. Aguchem R. N. Okagu I. U. (2022). Therapeutic benefits of Salvia species: a focus on cancer and viral infection. Heliyon8, e08763. 10.1016/j.heliyon.2022.e08763

38

Ezema C. A. Aguchem R. N. Aham E. C. Ezeorba W. F. C. Okagu I. U. Ezeorba T. P. C. (2024). Salvia africana-lutea L.: a review of ethnobotany, phytochemistry, pharmacology applications and future prospects. Adv. Tradit. Med.24, 703–724. 10.1007/s13596-023-00726-x

39

Francik S. Francik R. Sadowska U. Bystrowska B. Zawiślak A. Knapczyk A. et al (2020). Identification of phenolic compounds and determination of antioxidant activity in extracts and infusions of Salvia leaves. Materials13, 5811. 10.3390/ma13245811

40

Gebremeskal Y. H. Nadtochii L. A. Eremeeva N. B. Mensah E. O. Kazydub N. G. Soliman T. N. et al (2024). Comparative analysis of the nutritional composition, phytochemicals, and antioxidant activity of chia seeds, flax seeds, and psyllium husk. Food Biosci.61, 104889. 10.1016/j.fbio.2024.104889

41

Gharehbagh H. J. Ebrahimi M. Dabaghian F. Mojtabavi S. Hariri R. Saeedi M. et al (2023). Chemical composition, cholinesterase, and α-glucosidase inhibitory activity of the essential oils of some Iranian native Salvia species. BMC Complement. Med. Ther.23, 184. 10.1186/s12906-023-04004-w

42

Ghavam M. Manca M. L. Manconi M. Bacchetta G. (2020). Chemical composition and antimicrobial activity of essential oils obtained from leaves and flowers of Salvia hydrangea DC. ex Benth. Sci. Rep.10, 15647. 10.1038/s41598-020-73193-y

43