- 1College of First Clinical Medicine, Shandong University of Traditional Chinese Medicine, Jinan, China

- 2Department of Breast and Thyroid Surgery, Affiliated Hospital of Shandong University of Traditional Chinese Medicine, Jinan, China

Breast cancer bone metastasis involves dynamic reprogramming of transcriptional networks and cellular homeostasis. Current primary treatment strategy relies on palliative care, and the search for effective therapeutic targets remains a critical challenge. MicroRNAs (miRNAs), endogenous non-coding RNA molecules, exert precise regulation of gene expression through sequence-specific binding to the 3′ UTR of target mRNAs. Accumulating evidence has established miRNAs as pivotal regulators of breast cancer and its metastatic bone disease. Depending on their target genes, individual miRNAs may function as oncogenic miRNAs (oncomiRs) or as tumor suppressor miRNAs (tsmiRs), and hold potential as biomarkers for diagnosis and prognosis. This review systematically analyzes the regulatory mechanisms of critical miRNAs and their target genes in breast cancer bone metastasis, offering novel insights for early diagnosis and targeted therapeutic strategies.

1 Introduction

Breast cancer remains the most prevalent malignancy among women worldwide, with bone metastasis representing the most common site of distant metastasis (Sui et al., 2022). Epidemiological data reveal that approximately 90% of breast cancer-related deaths are caused by complications arising from metastatic disease. Notably, bone metastasis occurs in up to 70% of metastatic breast cancer patients (Chen et al., 2018). These skeletal lesions frequently precipitate severe skeletal-related events, including intense bone pain, spinal cord or nerve compression, hypercalcemia, urinary and bowel dysfunction, and even paralysis, all of which contribute to elevated mortality rates (Aielli and Ponzetti Mrucci, 2019). Current therapeutic strategies include systemic therapies, such as chemotherapy and endocrine treatment, aimed at inhibiting tumor proliferation, as well as bone-targeted drugs, such as bisphosphonates or denosumab, which inhibit excessive cancer-induced bone destruction (Coleman et al., 2014). However, while these interventions alleviate symptoms and improve quality of life, they remain palliative, underscoring the need for new therapeutic or diagnostic interventions to prevent the formation of bone metastasis.

In recent years, the underlying mechanisms of bone metastasis have become a popular research focus, with increasing evidence supporting the “seed and soil” hypothesis, which posits that tumor cells can only thrive in a microenvironment that is conducive to their growth (Marazzi et al., 2020; Mashouri et al., 2019; Elshimy et al., 2025). Breast cancer bone metastasis-a complex, multi-step process (Liang et al., 2020; Shin Ekoo and Koo, 2020; Arakil et al., 2024)-often begins with clinically undetectable micrometastases preceding overt lesions, involving the formation and invasion of the primary breast tumor, the survival of tumor cells along the metastatic pathway, and their colonization and proliferation at the bone site, making vigilant monitoring and early intervention crucial. Currently, effective and reliable markers for monitoring and therapeutic targets for detecting and (Arakil et al., 2024) treating breast cancer bone metastasis remain lacking in clinical trials (Arakil et al., 2024), highlighting the urgent need for foundational research to elucidate the underlying mechanisms and molecular networks.

Significantly, microRNAs (miRNAs) have emerged as crucial post-transcriptional regulators in this process, capable of accurately controlling the expression of various genes linked to tumor invasion, bone colonization, and osteoclast activation. By orchestrating these intricate interactions, miRNAs occupy a central role within the signaling network of metastasis. miRNAs are small endogenous non-coding RNAs comprising 19–25 nucleotides. In 1993, Victor Ambros and colleagues discovered that the lin-4 gene, the first identified miRNA, regulates developmental timing in Caenorhabditis elegans (Slack and Ruvkun, 1997; Lee et al., 1993). Subsequent studies have shown that miRNAs are widely expressed across human tissues and organs, playing critical roles in physiological processes (Abadi et al., 2021) such as proliferation, apoptosis, differentiation, and metabolism, as well as in pathological processes like cancer, pulmonary fibrosis, and diabetes. In recent years, the aberrant expression of miRNAs has been increasingly associated with the progression of human breast cancer. This review summarizes recent findings on key miRNAs involved in the formation and development of breast cancer bone metastasis, aiming to provide a theoretical foundation for understanding its molecular regulatory network and identifying new therapeutic targets for clinical diagnosis and treatment.

2 Biogenesis and function of miRNAs

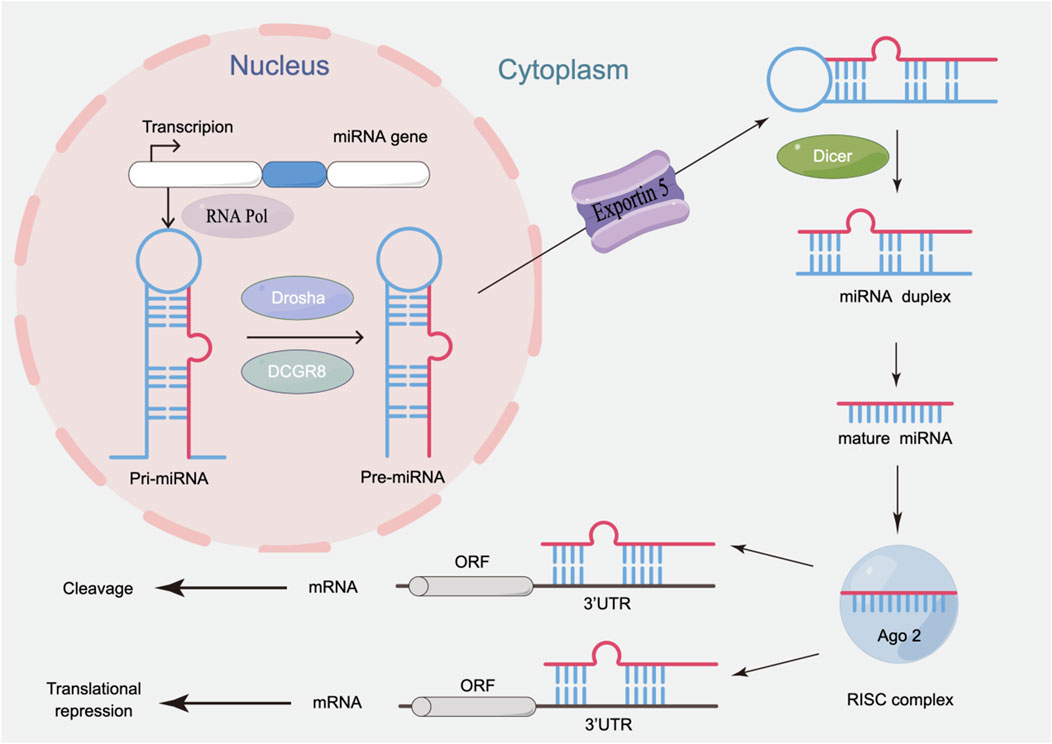

MiRNA biogenesis involves tightly regulated nuclear and cytoplasmic processing stages (Figure 1). Initially, miRNA genes are transcribed into primary miRNAs (pri-miRNAs) by RNA polymerase II (RNA Pol II) in the nucleus. The pri-miRNAs are then processed by the nuclease Drosha and its cofactor DGCR8 to form precursor miRNAs (pre-miRNAs) (Hill and Tran, 2021). Exportin-5 mediates the translocation of pre-miRNA to the cytoplasm, where the Dicer enzyme catalyzes the excision of the terminal loop to generate mature double-stranded miRNAs (Bernstein et al., 2001). These mature miRNAs are loaded onto Argonaute (AGO) proteins, forming the miRNA-induced silencing complex (miRISC). One strand is rapidly degraded, while the other strand can bind to the 3′ untranslated region (UTR) of target mRNAs, inhibiting translation or inducing specific degradation of mRNA, thereby influencing post-transcriptional regulation of target genes, and participating in key cellular processes.

The function of miRNAs primarily depends on their ability to bind to the 3′ UTR of target mRNAs, thereby regulating gene expression (Desvignes et al., 2021). Interestingly, a single miRNA can target multiple different mRNA targets, and the expression of specific mRNAs can be regulated by several distinct miRNAs. Thus, miRNA-mediated gene regulation affects nearly every fundamental cellular process (Jia and Wei, 2020). Furthermore, cancer-related miRNAs are broadly categorized as oncogenic miRNAs (oncomiRs), which promote tumorigenesis by suppressing tumor suppressor genes, or tumor suppressor miRNAs (tsmiRs), which inhibit oncogene expression to counteract malignant progression (Loh et al., 2019). Studies have also shown that in bone metastasis, abnormal miRNA expression, as a crucial driver of intracellular molecular changes, participates in regulating the pathological processes of bone metastasis in various cancers, including breast cancer (Puppo et al., 2021). Therefore, miRNAs could serve as promising therapeutic targets and regulators of metastatic progression in breast cancer bone metastasis.

3 miRNAs in the bone microenvironment of breast cancer metastasis

Bone metastasis is a pathological connection between the primary tumor and the secondary metastatic site in bone, arising from reciprocal interactions between disseminated tumor cells and the bone microenvironment. Tumor metastasis is a multi-step cascade process (Figure 2) involving tumor cell invasion and infiltration, intravasation across the vascular endothelium into the circulatory system, survival in circulation, subsequent extravasation to distant organs, adaptation to the metastatic microenvironment, and proliferation to form metastatic lesions (Liang et al., 2020). Epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT), as a key step, confers invasiveness to tumor cells, facilitating their dissemination to distant sites (Hanahan and Folkman, 1996; Huber and Kraut Nbeug, 2005). Secondly, the matrix metalloproteinase (MMP) family of extracellular proteases, secreted by tumor cells, degrades the basement membrane and extracellular matrix, which also leads to the release of growth factors and cytokines from cells and the extracellular matrix, thereby promoting cancer cell growth and survival (Liang et al., 2020; Kessenbrock and Plaks Vwerb, 2010). Subsequently, abnormally structured blood vessels within the tumor tissue (such as leaky vasculature) (Weis and Mcheresh, 2011) facilitate tumor cell entry into the bloodstream; circulating tumor cells can express CD47 (Chao et al., 2012), among other molecules, to evade phagocytosis by macrophages. Metastatic breast cancer cells migrate via the bloodstream from the primary site to distant organs such as the bone (Song and Wei Cli, 2022). Bone cells can release factors like CXCL12 to promote cancer cell bone metastasis, and the abundant blood supply and continuous remodeling process in bone create a permissive microenvironment: osteoblasts and osteoclasts secrete chemokines that recruit these cancer cells, subsequently triggering bone destruction while promoting cancer cell proliferation and differentiation (Hiraga et al., 2012). Among these processes, the RANK/RANKL/OPG axis and canonical Wnt signaling, among others, regulate osteoclast and osteoblast activity (Kenkre and Sbassett, 2018). Furthermore, tumor cell-derived factors such as parathyroid hormone-related protein (PTHrP) and interleukin-11 (IL-11) promote osteoclast activity by altering the RANKL/OPG ratio. During increased osteolysis, tumor growth-promoting factors such as bone morphogenetic proteins (BMPs), insulin-like growth factor-1 (IGF-1), and transforming growth factor-beta1 (TGF-β1) are released from the bone matrix (Clezardi et al., 2007; Clines and Aguise, 2008; Haider et al., 2022). Notably, bone-colonizing breast cancer cells further upregulate osteogenic transcription factors like Runx2, promote the release of bone growth factors and cytokines, accelerate tumor growth, and form a vicious cycle (Song and Wei Cli, 2022). Osteoclasts are key drivers of osteolytic breast cancer metastasis; thus, in addition to conventional radiotherapy and chemotherapy, standard care includes drugs that inhibit excessive bone resorption, such as bisphosphonates and the anti-RANKL antibody denosumab (D'Oronzo et al., 2019). However, these approaches merely mitigate symptoms without addressing metastatic causes.

MiRNAs, as small non-coding RNAs, play a crucial role in regulating the complex cellular crosstalk within the bone microenvironment—a system shaped by secreted factors, signaling pathways, and epigenetic mechanisms—and in establishing and maintaining the bone metastatic environment during the metastatic cascade (Zoni Evan der Pluijm and van der Pluijm, 2016). Researchers have found that miR-20a-5p, derived from exosomes of MDA-MB-231 cells, enhances osteoclast activity and promotes their proliferation and differentiation by targeting the expression of SRCIN1—a negative regulator of malignant phenotypes and breast cancer progression (Guo et al., 2019; Grasso et al., 2019). Additionally, miR-141 and miR-219 have been shown to reduce osteoclast activity and diminish osteoblastic breast cancer bone metastasis in vivo (Ell et al., 2013). Further studies have revealed that in breast cancer cells, miR-218-5p directly targets two key inhibitors of the Wnt signaling pathway—Sclerostin (SOST) and secreted frizzled-related protein 2 (sFRP2)—thereby activating Wnt signaling, promoting osteoclast differentiation, and accelerating breast cancer bone metastasis (Taipaleenmäki et al., 2016). It is noteworthy that miR-218 also disrupts bone matrix homeostasis through dual mechanisms: on one hand, cancer cell-secreted miR-218 directly acts on osteoblasts to suppress type I collagen expression; on the other hand, intracellular miR-218 upregulates inhibin βA, which in turn interferes with the processing and deposition of type I collagen (Liu et al., 2018). These direct and indirect effects collectively exacerbate the osteolytic vicious cycle, creating a favorable environment for breast cancer cell colonization in bone tissue. These findings demonstrate that miRNAs can regulate the process of breast cancer bone metastasis through multi-target and multi-pathway mechanisms, highlighting their potential value as therapeutic targets.

4 Roles of miRNAs in breast cancer bone metastasis

Numerous studies have shown that miRNAs regulate the intricate communication between bone cells and breast cancer tumor cells, with different functional regulations by miRNAs modulating the vicious cycle of bone metastasis (Table 1) (Croset et al., 2018; Cai et al., 2018). Clinically, alterations in miRNA expression profiles strongly correlate with disease progression and clinical outcomes in breast cancer patients, making them candidate biomarkers for risk stratification, prognosis, and disease monitoring (Swellam et al., 2021).

4.1 OncomiRs in breast cancer bone metastasis

4.1.1 miR-21

In breast cancer, miR-21 is overexpressed and promotes the metastasis of breast cancer cells to the bone, leading to poor prognosis for patients (Sah et al., 2015). Mechanistically, miR-21 drives tumor progression by downregulating SMAD7 and MSH2 in the TGF-β pathway while upregulating human epidermal growth factor receptor 2, thereby functioning as an oncogene (Chen et al., 2013; Gong et al., 2011). The tumor suppressor gene TPM1, a direct target of miR-21, inhibits anchorage-independent growth when overexpressed in MCF-7 breast cancer cells (Zhu et al., 2007). Other studies have found that lysophosphatidic acid receptor 1 (LPA1), a metastasis-driving GPCR, upregulates oncogenic miR-21 via PI3K/ZEB1 to promote breast cancer invasion and bone colonization; miR-21 inhibition blocks LPA1-mediated migration and reduces metastatic burden in vivo (Sah et al., 2015). Therefore, targeting multiple points in the miR-21 pathway may prevent metastatic cells from migrating to the bone.

4.1.2 miR-10b

Highly expressed in metastatic breast cancer cells, miR-10b actively regulates cancer cell migration and invasion, establishing its role as a critical metastasis-associated oncomiR (Ma and Teruya-Feldstein Jweinberg, 2007). Research demonstrates that TWIST1 promotes breast cancer bone metastasis by binding the miR-10b promoter to induce its expression, which suppresses HOXD10 and activates the metastasis-promoting gene RHOC, thereby increasing tumor burden and bone destruction (Ma and Teruya-Feldstein Jweinberg, 2007; Croset et al., 2014). Clinically, serum miR-10b levels are significantly elevated in breast cancer patients with confirmed bone metastasis (sensitivity: 76.9%, specificity: 97.9%) compared to non-metastatic cases, highlighting its potential as a novel biomarker for diagnosing and detecting breast cancer bone metastasis (Dwedar et al., 2021; Roth et al., 2010).

4.1.3 miR-224

Overexpression of miR-224 enhances the metastatic capacity of breast cancer cells. In MDA-MB-231 breast cancer cells, miR-224 overexpression silences the tumor suppressor RKIP, thereby activating pro-metastatic genes (CXCR4, MMP1, OPN) that mediate bone-specific metastasis through enhanced invasion and osteoclast activation (Huang et al., 2012). Furthermore, miR-224 directly suppresses caspase-9 (CASP9) by targeting its mRNA, and knockdown of miR-224 in MDA-MB-231 cells significantly restores CASP9 protein levels, thereby inhibiting cell proliferation, migration, and invasion, suggesting preclinical drug candidate for breast cancer patients (Zhang et al., 2019).

4.1.4 miR-214-3p

miR-214-3p, derived from osteoclasts, is an important regulator in breast cancer bone metastasis. Metastatic cancer cells can induce excessive osteoclast formation and overactive bone resorption, leading to osteolytic bone metastasis (OBM). Elevated miR-214-3p expression in osteoclasts, which was observed in bone tissues of breast cancer patients with OBM and corroborated in osteoclasts from breast cancer xenograft (BCX) models, directly targets TRAF3 to suppress its expression, thereby enhancing osteoclast differentiation and bone-resorbing activity that drives OBM progression (Liu et al., 2017). Moreover, miR-214 directly targets p53 to promote breast cancer cell invasion, and overexpression of p53 reverses this oncogenic effect, suggesting miR-214 as a potential therapeutic target for inhibiting invasion in breast cancer (Wang et al., 2015).

4.1.5 Other OncomiRs

miR-665 is significantly upregulated in breast cancer tissues and promotes cancer cell proliferation, invasion, and metastasis by inhibiting NR4A3 to activate the MEK signaling pathway, thereby functioning as an oncomiR in breast cancer progression (Zhao et al., 2019). Serum miR-218-5p levels are markedly elevated in patients with bone metastasis compared to non-metastatic cases, suggesting its pro-metastatic role in skeletal dissemination. The pathological elevation of miR-218-5p activates the Wnt signaling pathway, thereby enhancing the metastatic properties of breast cancer cells and exacerbating cancer-induced osteolytic disease (Taipaleenmäki et al., 2016). miR-155 is identified as the most commonly associated with breast cancer (Grimaldi et al., 2020). miR-155 upregulates HK2 through dual mechanisms: suppressing SOCS1 to activate STAT3-mediated transcription and inhibiting C/EBPβ to block miR-143-dependent translational repression, thereby driving oncogenic phenotypes in tumor cells (Jiang et al., 2012). Similarly, within the bone microenvironment, miR-16 promotes the osteoclast activity and osteolytic bone destruction induced by breast cancer metastasis (Kitayama et al., 2021). Interestingly, during the early stages of breast cancer bone metastasis, miR-662 inhibits the differentiation of bone-resorbing osteoclasts, thereby concealing the presence of metastatic foci; overexpression of miR-662 ultimately leads to the development of overt osteolytic metastases (Puppo et al., 2023). Moreover, whether metastasis-promoting miRNAs known to facilitate dissemination to other organs, such as miR-141 [which promotes breast cancer brain metastasis (Debeb et al., 2016)], also participate in the initiation and progression of bone metastasis remains to be clarified.

4.2 TsmiRs in breast cancer bone metastasis

4.2.1 miR-30 family

The miR-30 family, comprising miR-30a, miR-30b, miR-30c, miR-30d, and miR-30e, acts as an effective suppressor of breast cancer bone metastasis (Croset et al., 2018). High expression of miR-30a significantly improves survival in triple-negative breast cancer patients. Researchers have further demonstrated that p53 suppresses breast cancer cell invasion and dissemination by activating miR-30a expression, which subsequently inhibits the EMT-related transcription factor ZEB2 (di Gennaro et al., 2018). In xenograft mouse models of breast cancer stem cells, miR-30 overexpression effectively reduces bone metastasis (Ouzounova et al., 2013). Overall, the regulatory role of the miR-30 family in breast cancer bone metastasis involves multiple critical pathways, providing a theoretical basis for using miR-30 family members to inhibit breast cancer bone metastasis (Croset et al., 2018).

4.2.2 miR-429

As a member of the miR-200 family, miR-429 acts as a tumor suppressor that inhibits cancer progression (Zhang et al., 2016). Compared with primary breast cancer tissue, miR-429 is downregulated in the bone tissue of patients with metastatic breast cancer, suggesting a negative correlation between miR-429 levels and bone metastasis (Zhang X. et al., 2020). However, miR-429 has also been observed at high levels in bone tissue samples from breast cancer patients. Subsequent overexpression of miR-429 in MDA-MB-231 cells significantly suppressed tumor cell invasion (Ye et al., 2015; Zhang L. et al., 2020). Furthermore, miR-429 directly suppresses v-Crk sarcoma virus CT10 oncogene homolog-like (CrkL) expression, thereby inhibiting osteoclast-mediated bone resorption and reducing local bone destruction and distant bone metastasis (Zhang X. et al., 2020).

4.2.3 miR-203

miR-203 is notably downregulated in highly metastatic breast cancer cells. Research has shown reveals that TGF-β signaling induces transcriptional repression of miR-203 through direct binding of SNAI2 to the miR-203 promoter, thereby promoting EMT and metastatic progression in breast cancer (Ding et al., 2013). Compared with healthy bone, miR-203 levels are lower in bone tissue from patients with breast cancer bone metastases. In MDA-MB-231 cells, elevated miR-203 expression downregulates cell motility-related genes (ROCK, CD44, and PTK2), reducing primary tumor size and spontaneous metastasis, including bone lesions (Taipaleenmäki et al., 2015). Thus, modulating miR-203 expression may serve as a potential therapeutic approach for metastatic breast cancer patients.

4.2.4 miR-31

miR-31 functions as a multifaceted tumor suppressor, coordinating inhibition of cell cycle progression. Upregulating miR-31 significantly decreases migration and invasion in MDA-MB-231 and MCF-7 cells (Luo et al., 2016). Compared with healthy breast tissue, miR-31 expression is reduced in breast cancer tissue (Gharib et al., 2022), with low expression correlating with adverse pathological features such as bone metastasis (Vimalraj et al., 2013). Notably, the miR-31-p specifically suppresses Dicer expression in MCF-7 cells (Chan et al., 2013). Separately, in triple-negative breast cancer miR-31 acts as a metastasis suppressor by directly targeting SATB2, thereby inhibiting tumor cell migration and invasion (Luo et al., 2016).

4.2.5 miR-146

miR-146a/miR-146b exhibits therapeutic potential for suppressing breast cancer metastasis. In MDA-MB-231 cells, miR-146 significantly downregulates epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) expression, inhibiting breast cancer cell invasion and migration in vitro and mitigating bone destruction (Hurst et al., 2009). Additionally, miR-146a/miR-146b negatively regulates NF-κB activity in highly metastatic breast cancer cell lines, impairing migratory capacity and confirming its tumor-suppressive role (Bhaumik et al., 2008). Consequently, miR-146 has been proposed as a diagnostic and prognostic biomarker for breast cancer bone metastasis.

4.2.6 Other TsmiRs

Research has revealed that miR-1976 expression is lower in bone metastatic breast cancer cells than in primary tumors. Moreover, suppression of miR-1976 promotes epithelial-mesenchymal transition and cancer stem cell properties by targeting PIK3CG (Wang J. et al., 2020). Another study demonstrated that within the bone microenvironment, miR-133a and miR-223 inhibit osteoclast activity and bone destruction induced by breast cancer metastasis (Kitayama et al., 2021). During the early stages of breast cancer bone metastasis, miR-24-2-5p suppresses tumor cell dissemination in bone tissue and impedes the differentiation of precursor cells into mature osteoclasts, exerting a protective effect (Puppo et al., 2024).

5 miRNA-mediated regulation of key genes in the bone microenvironment during breast cancer bone metastasis

5.1 Runx2

Runx2, abnormally expressed in bone-metastatic tumors, serves as a critical regulator of osteogenesis and metastasis in human malignancies including breast cancer (Vishal et al., 2017). Evidence suggests that Runx2 is highly expressed in metastatic breast cancer cells and plays a significant role in regulating breast cancer progression (Chang et al., 2014). Multiple miRNAs have been shown to modulate Runx2 in breast cancer bone metastasis. miR-135 and miR-203 reduce breast cancer bone metastasis by directly targeting and downregulating Runx2 expression (Taipaleenmäki et al., 2015). miR-3960 targets and downregulates Hoxa2, a repressor of Runx2 expression, thereby alleviating its inhibitory effect on Runx2 and promoting BMP-2-induced osteoblast differentiation (Hu R. et al., 2011). Moreover, miR-204 and its homolog miR-211 directly target Runx2, suppressing its expression and thereby inhibiting osteogenesis (Huang et al., 2010). miR-153 directly inhibits Runx2, thereby suppressing breast cancer cell proliferation, migration, and invasion, establishing the miR-153/Runx2 regulatory axis as a potential therapeutic target (Zuo et al., 2019). These findings collectively confirm Runx2’s pivotal role in breast cancer-mediated bone metastasis.

5.2 c-Myc

c-Myc participates in regulating diverse biological functions, including the growth, proliferation, and differentiation of aggressive breast cancer cells, acting as a potent activator of oncogenic transcription (Obaya et al., 2002; Gao et al., 2023). Studies reveal that c-Myc is highly expressed in triple-negative breast cancer cell lines. Let-7a downregulates c-Myc expression by binding to its 3′UTR, thereby inhibiting the proliferation, migration, and invasion of MDA-MB-231 cells (Du et al., 2019). Knockdown of c-Myc significantly reduces the expression of miR-4723-5p, which in turn decreases breast cancer initiation and metastasis (Jin et al., 2022). The MYC proto-oncogene, overexpressed in triple-negative breast tissues, cooperates with DNA methyltransferase 3A (DNMT3A) to induce promoter methylation, downregulating miR-200b expression and promoting EMT (Pang et al., 2018). Additionally, miR-3189-3p exerts anti-tumor activity by targeting transforming regulatory proteins, impairing c-Myc translation, and inhibiting skeletal metastasis, providing novel therapeutic insights (Vittori et al., 2022).

5.3 Cyclin D1

Cyclin D1 becomes overexpressed following genomic rearrangement and functions as a crucial oncogene in breast cancer pathogenesis (Mohammedi et al., 2019; Arnold and Papanikolaou, 2005). miR-373, a well-characterized oncomiR, influences patient prognosis by modulating cyclin D1 (Bakr et al., 2021). Similarly, miR-425-5p overexpression upregulates Cyclin D1 protein levels and activates PI3K/AKT signaling, both of which contribute to breast cancer development (Zhang LF. et al., 2020). In breast cancer cells, the miR-17/20 cluster demonstrates an inverse relationship with cyclin D1 protein levels, suppressing its translation via 3′UTR binding and inhibiting cancer cell proliferation (Yu et al., 2008). Moreover, miR-1250-5p expression is significantly reduced in triple-negative breast cancer cells. Restoring miR-1250-5p decreases cyclin D1 protein levels, induces apoptosis, and inhibits epithelial-mesenchymal transition, thereby exerting tumor-suppressive effects (Shuaib and Kumar, 2023). These findings suggest that strategic upregulation or downregulation of specific miRNAs represents an effective approach to modulate Runx2, c-Myc, and cyclin D1 expression, potentially enabling novel therapeutic strategies against breast cancer bone metastasis.

5.4 Other potential biomarkers

Interleukins (ILs) play crucial regulatory roles in multiple stages of the breast cancer bone metastasis cascade (Haider et al., 2021). Among them, IL-1β, IL-6, IL-8, IL-11, and IL-17 have been extensively validated as mediators of bidirectional communication between bone cells and breast cancer cells, making them potential therapeutic targets (Haider et al., 2021; Zhou and Tulotta Cottewell, 2022; Shibabaw and Teferi Bayelign, 2023). miRNAs also influence bone metastasis progression by regulating these IL-mediated signaling pathways. For example, miR-520b suppresses breast cancer cell migration through targeting the HBXIP/IL-8 regulatory network (Hu N. et al., 2011). Notably, studies have identified miR-204, miR-211, and miR-379 as inhibitors of TGF-β-induced IL-11 production in bone metastatic breast cancer cells; these miRNAs directly target IL-11 expression by binding to its 3′UTR (Pollari et al., 2012). Further research revealed that miR-124, which is significantly downregulated in breast cancer bone metastases, inhibits osteoclastogenesis and suppresses bone metastasis through direct targeting of its downstream gene, IL-11 (Cai et al., 2018). Collectively, these findings suggest that miRNA-mediated regulation of interleukins is a critical molecular mechanism involved in the bone microenvironment during breast cancer bone metastasis.

The transcription factor SOX9, markedly upregulated in breast cancer patient samples, serves as a key regulator of breast cancer cell survival and metastasis (Ma et al., 2020; Chao et al., 2022). Studies have demonstrated that downregulation of miR-134-3p and miR-224-3p increases SOX9 levels, thereby promoting breast cancer progression (Chao et al., 2022). Similarly, research has shown that miR-215-5p targets the oncogenic transcription factor SOX9, effectively inhibiting breast cancer cell invasion, metastasis, and disease progression (Gao et al., 2019). Additionally, miR-133 modulates breast cancer tumorigenesis and metastasis via targeting SOX9 (Wang et al., 2018).

Furthermore, miRNAs interact with long non-coding RNAs (lncRNAs) through various mechanisms, including acting as competing endogenous RNA sponges, regulating miRNA degradation, mediating intrachromosomal interactions, and modulating epigenetic elements, ultimately influencing tumor initiation and progression (Bhattacharjee et al., 2023). In breast cancer, inhibition of lncRNA PANDAR reduces cancer cell proliferation and invasion (Li and Su Xpan, 2019), while lncRNA SPRY4-IT1 promotes breast cancer cell proliferation and stemness by targeting miR-6882-3p (Song et al., 2019). Further research demonstrates that lncRNA SNHG3 modulates osteogenic differentiation of bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells during bone metastasis via the miR-1273g-3p/BMP3 axis (Sun et al., 2022), and TRG-AS1 competitively binds miR-877-5p to upregulate WISP2, thereby inhibiting bone metastasis (Zhu et al., 2023).

6 miRNAs as potential biomarkers for the detection and treatment of breast cancer bone metastasis

Bone involvement in metastatic breast cancer presents a significant clinical challenge, with approximately 65%–70% of advanced-stage patients developing bone metastases (Salvador and Llorente, 2019). Early prevention and accurate diagnosis are therefore critical for improving survival outcomes. Current imaging modalities, including bone scintigraphy, positron emission tomography-computed tomography (PET-CT), and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), exhibit comparable diagnostic performance for bone metastasis detection, yet their specificity and sensitivity remain suboptimal due to multifactorial limitations (Kundaktepe et al., 2021). Key limitations impairing their performance include variable detection of micrometastases, challenges in differentiating malignant from benign bone conditions, and the high cost or radiation exposure of certain techniques—prompting the exploration of auxiliary diagnostic techniques. miRNAs demonstrate relative stability and tissue specificity in physiological fluids, with detectable alterations in serum, plasma, breast ductal fluid, and circulating exosomes of breast cancer patients (Ying et al., 2023; Do Canto et al., 2016). Changes in miRNA expression correlate with disease status and clinical outcomes, suggesting their potential as non-invasive biomarkers for “liquid biopsy,” an approach that provides advantages including low invasiveness, cost-effectiveness, and technical simplicity (Haider et al., 2022; Cai et al., 2015; Ochiya and Hashimoto Kshimomura, 2025).

By comparing serum miRNA profiles of healthy individuals and breast cancer patients, researchers have identified a combination of miR-1246, miR-1307-3p, miR-4634, miR-6861-5p, and miR-6875-5p that detects breast cancer with high sensitivity, specificity, and accuracy (Shimomura et al., 2016). Moreover, numerous clinical studies (Nassar and Nasr Rtalhouk, 2017; Chiorino et al., 2023; Jordan-Alejandre et al., 2023) support the potential of miRNAs in early breast cancer detection. Our investigations further indicate that, in the complex interactions between breast cancer cells and the bone microenvironment, miRNAs may serve as potential biomarkers for detecting bone metastases. We have summarized the key miRNAs that, under experimental intervention, directly or indirectly affect the progression of bone metastasis (Figure 3). In clinical studies, serum levels of miR-129, miR-24-2-5p, miR-662, and miR-10b show promise as biomarkers for early diagnosis of bone metastasis in breast cancer patients (Puppo et al., 2023; Puppo et al., 2024; Wang C. et al., 2020; Zhao et al., 2012). However, studies have indicated that miR-21 acts as a non-specific molecule broadly involved in systemic inflammatory responses and multi-organ metastatic processes (Jenike and Ehalushka, 2021); therefore, its solitary detection in body fluids lacks organ specificity. Combining miR-21 detection with bone-specific miRNAs or serum markers indicative of osteogenesis or osteolysis, and validating these combinations in large-scale prospective cohorts, may establish such non-specific miRNA markers as adjunctive tools for assessing the risk of breast cancer bone metastasis. Furthermore, findings based on laboratory studies and small-scale clinical validation may exhibit significant variability. Therefore, large-scale, fixed-population microRNA screening with extended follow-up durations needs to be conducted. Clinically valuable diagnostic screening should be performed according to breast cancer subtype specificity, combined with other imaging modalities and biological markers (Ochiya and Hashimoto Kshimomura, 2025), to detect metastatic lesions at earlier stages and implement more effective therapeutic interventions.

Inhibition of oncomiRs or restoration of tsmiRs has emerged as a potential therapeutic strategy in cancer treatment. Two primary miRNA-based approaches exist: (1) miRNA replacement therapy, which utilizes miRNA mimics to restore or overexpress tsmiR function; and (2) miRNA inhibition, employing inhibitors to suppress or downregulate oncomiRs (Abou Madawi et al., 2024; Mollaei and Safaralizadeh Rrostami, 2019). Recent advances have overcome miRNA delivery barriers through engineered carriers with optimized size, shape, structure, chemistry, and functionality, enabling efficient targeted delivery for cancer gene regulation to modulate gene expression and treat cancer (Tian et al., 2024). Researchers have developed polyethyleneimine-modified magnetic nanoparticle carriers to deliver miR-21, miR-145, and miR-9, achieving targeted in situ tumor delivery and effectively inhibiting tumor growth (Yu et al., 2016). In another study, researchers designed ultra-small iron oxide nanoparticles conjugated with anti-miR-10b antagonists (MN-anti-miR10b), successfully resulting in complete and sustained regression of local lymph node and distant metastatic lesions without detectable systemic toxicity (Le Fur et al., 2021). Further studies demonstrated that MN-anti-miR10b treatment reduced the stem-cell-like characteristics of breast cancer cells, making it a promising therapeutic option for stem-like breast cancer subtypes (Halim et al., 2024). Similarly, branched polyethyleneimine (PEI 25k), a commonly used gene vector, has been modified with alendronate groups as bone-targeting moieties to construct a targeted delivery system for miR-34a to breast cancer bone metastases, achieving significant antitumor effects in metastatic lesions (Han et al., 2023). Notably, a bone-targeting polymeric nucleic acid delivery carrier (ALN-Pabol) chieved direct skeletal delivery of miR-339, offering a promising strategy against bone-metastatic breast cancer (Li et al., 2025).

7 Conclusion

Over the past decade, RNA-based medicine has received increasing attention, with non-coding RNAs including miRNAs emerging as promising candidates for therapeutic development alongside mRNA-based approaches. Although no miRNA-targeted drugs have yet received clinical approval, several miRNA-based compounds are undergoing preclinical evaluation and clinical trials, showing encouraging progress in cancer treatment applications. Recent advances in transcriptomic research have further reinforced the diagnostic and prognostic value of miRNAs, particularly as predictors of therapeutic response and biomarkers for breast cancer bone metastasis formation and progression. The growing complexity of breast cancer research has spurred extensive investigations into miRNA-mediated regulatory networks, revealing differential expression patterns and mechanistic insights into miRNAs associated with tumor growth and skeletal dissemination. In metastatic breast cancer cells, changes such as miRNA silencing, translational blockade, miRNA modification, or overexpression suggest new possibilities for delivering miRNAs or inhibiting miRNA synthesis to modulate key metastatic oncogenes—a promising direction for future breast cancer bone metastasis therapies.

Capitalizing on the stability of miRNAs in biofluids and their pivotal roles in bone metastasis, current research explores the possibility of modulating breast cancer-derived miRNA expression to alter tumor cell phenotypes or disrupt bone microenvironment interactions. Such approaches may pave the way for developing precision therapies and preventive strategies. However, inherent biological challenges persist, including off-target effects, tissue specificity limitations, and delivery system inefficiencies inherent to short non-coding RNA molecules. Overcoming these barriers is critical for advancing miRNA-based therapeutics, particularly for unmet clinical needs like metastatic bone disease. Future efforts should resolve these challenges to translate miRNA research into clinically viable treatments for breast cancer bone metastasis.

Author contributions

FM: Writing – original draft, Writing – review and editing. MZ: Software, Writing – original draft. DP: Investigation, Writing – review and editing. GS: Investigation, Writing – review and editing. JL: Conceptualization, Writing – original draft.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China, grant number 82374452.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Abadi, A. J., Zarrabi, A., Gholami, M. H., Mirzaei, S., Hashemi, F., Zabolian, A., et al. (2021). Small in size, but large in action: microRNAs as potential modulators of PTEN in breast and lung cancers. Biomolecules 11, 304. doi:10.3390/biom11020304

Abou Madawi, N. A., Darwish, Z., and Eomar, E. M. (2024). Targeted gene therapy for cancer: the impact of microRNA multipotentiality. Med. Oncol. 41, 214. doi:10.1007/s12032-024-02450-1

Aielli, F., and Ponzetti Mrucci, N. (2019). Bone metastasis pain, from the bench to the bedside. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 20, 280. doi:10.3390/ijms20020280

Arakil, N., Akhund, S. A., and Elaasser Bmohammad, K. S. (2024). Intersecting paths: unraveling the complex journey of cancer to bone metastasis. Biomedicines 12, 1075. doi:10.3390/biomedicines12051075

Arnold, A. P. A., and Papanikolaou, A. (2005). Cyclin D1 in breast cancer pathogenesis. J. Clin. Oncol. 23, 4215–4224. doi:10.1200/JCO.2005.05.064

Bakr, N. M., Mahmoud, M. S., Nabil, R., and Boushnak Hswellam, M. (2021). Impact of circulating miRNA-373 on breast cancer diagnosis through targeting VEGF and cyclin D1 genes. J. Genet. Eng. Biotechnol. 19, 84. doi:10.1186/s43141-021-00174-7

Bernstein, E., Caudy, A. A., Hammond, S., and Mhannon, G. J. (2001). Role for a bidentate ribonuclease in the initiation step of RNA interference. Nature 409, 363–366. doi:10.1038/35053110

Bhattacharjee, R., Prabhakar, N., Kumar, L., Bhattacharjee, A., Kar, S., Malik, S., et al. (2023). Crosstalk between long noncoding RNA and microRNA in cancer. Cell. Oncol. (Dordr) 46, 885–908. doi:10.1007/s13402-023-00806-9

Bhaumik, D., Scott, G. K., Schokrpur, S., Patil, C. K., and Campisi Jbenz, C. C. (2008). Expression of microRNA-146 suppresses NF-kappaB activity with reduction of metastatic potential in breast cancer cells. Oncogene 27, 5643–5647. doi:10.1038/onc.2008.171

Cai, X., Janku, F., and Zhan Qfan, J. B. (2015). Accessing genetic information with liquid biopsies. Trends Genet. 31, 564–575. doi:10.1016/j.tig.2015.06.001

Cai, W. L., Huang, W. D., Li, B., Chen, T. R., Li, Z. X., Zhao, C. L., et al. (2018). microRNA-124 inhibits bone metastasis of breast cancer by repressing Interleukin-11. Mol. Cancer 17, 9. doi:10.1186/s12943-017-0746-0

Chan, Y. T., Lin, Y. C., Lin, R. J., Kuo, H. H., Thang, W. C., Chiu, K. P., et al. (2013). Concordant and discordant regulation of target genes by miR-31 and its isoforms. PLoS One 8, e58169. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0058169

Chang, C. H., Fan, T. C., Yu, J. C., Liao, G. S., Lin, Y. C., Shih, A. C., et al. (2014). The prognostic significance of RUNX2 and miR-10a/10b and their inter-relationship in breast cancer. J. Transl. Med. 12, 257. doi:10.1186/s12967-014-0257-3

Chao, M. P., Weissman, I., and Lmajeti, R. (2012). The CD47-SIRPα pathway in cancer immune evasion and potential therapeutic implications. Curr. Opin. Immunol. 24, 225–232. doi:10.1016/j.coi.2012.01.010

Chao, T.-Y., Kordaß, T., Osen Weichmüller, S. B., and Eichmüller, S. B. (2022). SOX9 is a target of miR-134-3p and miR-224-3p in breast cancer cell lines. Mol. Cell. Biochem. 478, 305–315. doi:10.1007/s11010-022-04507-z

Chen, L., Li, Y., Fu, Y., Peng, J., Mo, M. H., Stamatakos, M., et al. (2013). Role of deregulated microRNAs in breast cancer progression using FFPE tissue. PLoS One 8, e54213. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0054213

Chen, W., Hoffmann, A. D., and Liu Hliu, X. (2018). Organotropism: new insights into molecular mechanisms of breast cancer metastasis. NPJ Precis. Oncol. 2, 4. doi:10.1038/s41698-018-0047-0

Chiorino, G., Petracci, E., Sehovic, E., Gregnanin, I., Camussi, E., Mello-Grand, M., et al. (2023). Plasma microRNA ratios associated with breast cancer detection in a nested case-control study from a mammography screening cohort. Sci. Rep. 13, 12040. doi:10.1038/s41598-023-38886-0

Clezardin, P. T. A., and Teti, A. (2007). Bone metastasis: pathogenesis and therapeutic implications. Clin. Exp. Metastasis 24, 599–608. doi:10.1007/s10585-007-9112-8

Clines, G., and Aguise, T. A. (2008). Molecular mechanisms and treatment of bone metastasis. Expert Rev. Mol. Med. 10, e7. doi:10.1017/S1462399408000616

Coleman, R., Body, J. J., Aapro, M., and Hadji Pherrstedt, J.ESMO Guidelines Working Group (2014). Bone health in cancer patients: ESMO clinical Practice Guidelines. Ann. Oncol. 25 (Suppl. 3), iii124–iii137. doi:10.1093/annonc/mdu103

Croset, M., Goehrig, D., Frackowiak, A., Bonnelye, E., Ansieau, S., Puisieux, A., et al. (2014). TWIST1 expression in breast cancer cells facilitates bone metastasis formation. J. Bone Min. Res. 29, 1886–1899. doi:10.1002/jbmr.2215

Croset, M., Pantano, F., Kan, C. W. S., Bonnelye, E., Descotes, F., Alix-Panabières, C., et al. (2018). miRNA-30 family members inhibit breast cancer invasion, osteomimicry, and bone destruction by directly targeting multiple bone metastasis-associated genes. Cancer Res. 78, 5259–5273. doi:10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-17-3058

Du, J., Fan, J. J., Dong, C., Li, H., and Tma, B. L. (2019). Inhibition effect of exosomes-mediated Let-7a on the development and metastasis of triple negative breast cancer by down-regulating the expression of c-Myc. Eur. Rev. Med. Pharmacol. Sci. 23, 5301–5314. doi:10.26355/eurrev_201906_18197

D'Oronzo, S., Coleman, R., and Brown Jsilvestris, F. (2019). Metastatic bone disease: pathogenesis and therapeutic options: Up-date on bone metastasis management. J. Bone Oncol. 15, 004–4. doi:10.1016/j.jbo.2018.10.004

Debeb, B. G., Lacerda, L., Anfossi, S., Diagaradjane, P., Chu, K., Bambhroliya, A., et al. (2016). miR-141-Mediated regulation of brain metastasis from breast cancer. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 108, djw026. doi:10.1093/jnci/djw026

Desvignes, T., Sydes, J., Montfort, J., and Bobe Jpostlethwait, J. H. (2021). Evolution after whole-genome duplication: teleost MicroRNAs. Mol. Biol. Evol. 38, 3308–3331. doi:10.1093/molbev/msab105

di Gennaro, A., Damiano, V., Brisotto, G., Armellin, M., Perin, T., Zucchetto, A., et al. (2018). A p53/miR-30a/ZEB2 axis controls triple negative breast cancer aggressiveness. Cell. Death Differ. 25, 2165–2180. doi:10.1038/s41418-018-0103-x

Ding, X., Park, S. I., McCauley, L., and Kwang, C. Y. (2013). Signaling between transforming growth factor β (TGF-β) and transcription factor SNAI2 represses expression of microRNA miR-203 to promote epithelial-mesenchymal transition and tumor metastasis. J. Biol. Chem. 288, 10241–10253. doi:10.1074/jbc.M112.443655

Do Canto, L. M., Marian, C., Willey, S., Sidawy, M., Da Cunha, P. A., Rone, J. D., et al. (2016). MicroRNA analysis of breast ductal fluid in breast cancer patients. Int. J. Oncol. 48, 2071–2078. doi:10.3892/ijo.2016.3435

Dwedar, F. I., Shams-Eldin, R. S., Nayer Mohamed, S., Mohammed, A., and Fgomaa, S. H. (2021). Potential value of circulatory microRNA10b gene expression and its target E-cadherin as a prognostic and metastatic prediction marker for breast cancer. J. Clin. Lab. Anal. 35, e23887. doi:10.1002/jcla.23887

Ell, B., Mercatali, L., Ibrahim, T., Campbell, N., Schwarzenbach, H., Pantel, K., et al. (2013). Tumor-induced osteoclast miRNA changes as regulators and biomarkers of osteolytic bone metastasis. Cancer Cell. 24, 542–556. doi:10.1016/j.ccr.2013.09.008

Elshimy, Y., Alkhatib, A. R., and Atassi Bmohammad, K. S. (2025). Biomarker-Driven approaches to bone metastases: from molecular mechanisms to clinical applications. Biomedicines 13, 1160. doi:10.3390/biomedicines13051160

Gao, J. B., Zhu, M., and Nzhu, X. L. (2019). miRNA-215-5p suppresses the aggressiveness of breast cancer cells by targeting Sox9. FEBS Open Bio 9, 1957–1967. doi:10.1002/2211-5463.12733

Gao, F. Y., Li, X. T., Xu, K., Wang, R., and Tguan, X. X. (2023). c-MYC mediates the crosstalk between breast cancer cells and tumor microenvironment. Cell. Commun. Signal 21, 28. doi:10.1186/s12964-023-01043-1

Gharib, A. F., Khalifa, A. S., Eed, E. M., Banjer, H. J., Shami, A. A., Askary, A. E., et al. (2022). Role of MicroRNA-31 (miR-31) in breast carcinoma diagnosis and prognosis. Vivo 36, 1497–1502. doi:10.21873/invivo.12857

Gong, C., Yao, Y., Wang, Y., Liu, B., Wu, W., Chen, J., et al. (2011). Up-regulation of miR-21 mediates resistance to trastuzumab therapy for breast cancer. J. Biol. Chem. 286, 19127–19137. doi:10.1074/jbc.M110.216887

Grasso, S., Cangelosi, D., Chapelle, J., Alzona, M., Centonze, G., Lamolinara, A., et al. (2019). The SRCIN1/p140Cap adaptor protein negatively regulates the aggressiveness of neuroblastoma. Cell. Death and Differ. 27, 790–807. doi:10.1038/s41418-019-0386-6

Grimaldi, A. M., Nuzzo, S., Condorelli, G., and Salvatore Mincoronato, M. (2020). Prognostic and clinicopathological significance of MiR-155 in breast cancer: a systematic review. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 21, 5834. doi:10.3390/ijms21165834

Guo, L., Zhu, Y., Li, L., Zhou, S., Yin, G., Yu, G., et al. (2019). Breast cancer cell-derived exosomal miR-20a-5p promotes the proliferation and differentiation of osteoclasts by targeting SRCIN1. Cancer Med. 8, 5687–5701. doi:10.1002/cam4.2454

Haider, M. T., Ridlmaier, N., Smit, D., and Jtaipaleenmaki, H. (2021). Interleukins as mediators of the tumor cell-bone cell crosstalk during the initiation of breast cancer bone metastasis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 22, 2898. doi:10.3390/ijms22062898

Haider, M. T., Smit, D., and Jtaipaleenmäki, H. (2022). MicroRNAs: emerging regulators of metastatic bone disease in breast cancer. Cancers (Basel) 14, 729. doi:10.3390/cancers14030729

Halim, A., Al-Qadi, N., Kenyon, E., Conner, K. N., Mondal, S. K., Medarova, Z., et al. (2024). Inhibition of miR-10b treats metastatic breast cancer by targeting stem cell-like properties. Oncotarget 15, 591–606. doi:10.18632/oncotarget.28641

Han, T. Y., Hou, L. S., Li, J. X., Huan, M. L., Zhou, S., and Yzhang, B. L. (2023). Bone targeted miRNA delivery system for miR-34a with enhanced anti-tumor efficacy to bone-associated metastatic breast cancer. Int. J. Pharm. 635, 122755. doi:10.1016/j.ijpharm.2023.122755

Hanahan, D. F. J., and Folkman, J. (1996). Patterns and emerging mechanisms of the angiogenic switch during tumorigenesis. Cell. 86, 353–364. doi:10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80108-7

Hill, M. T. N., and Tran, N. (2021). miRNA interplay: mechanisms and consequences in cancer. Dis. Model. Mech. 14, dmm047662. doi:10.1242/dmm.047662

Hiraga, T., Myoui, A., Hashimoto, N., Sasaki, A., Hata, K., Morita, Y., et al. (2012). Bone-derived IGF mediates crosstalk between bone and breast cancer cells in bony metastases. Cancer Res. 72, 4238–4249. doi:10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-11-3061

Hu, R., Liu, W., Li, H., Yang, L., Chen, C., Xia, Z. Y., et al. (2011a). A Runx2/miR-3960/miR-2861 regulatory feedback loop during mouse osteoblast differentiation. J. Biol. Chem. 286, 12328–12339. doi:10.1074/jbc.M110.176099

Hu, N., Zhang, J., Cui, W., Kong, G., Zhang, S., Yue, L., et al. (2011b). miR-520b regulates migration of breast cancer cells by targeting Hepatitis B X-interacting protein and Interleukin-8. J. Biol. Chem. 286, 13714–13722. doi:10.1074/jbc.M110.204131

Huang, J., Zhao, L., and Xing Lchen, D. (2010). MicroRNA-204 regulates Runx2 protein expression and mesenchymal progenitor cell differentiation. Stem Cells 28, 357–364. doi:10.1002/stem.288

Huang, L., Dai, T., Lin, X., Zhao, X., Chen, X., Wang, C., et al. (2012). MicroRNA-224 targets RKIP to control cell invasion and expression of metastasis genes in human breast cancer cells. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 425, 127–133. doi:10.1016/j.bbrc.2012.07.025

Huber, M. A., and Kraut Nbeug, H. (2005). Molecular requirements for epithelial-mesenchymal transition during tumor progression. Curr. Opin. Cell. Biol. 17, 548–558. doi:10.1016/j.ceb.2005.08.001

Hurst, D. R., Edmonds, M. D., Scott, G. K., Benz, C. C., Vaidya, K., and Swelch, D. R. (2009). Breast cancer metastasis suppressor 1 up-regulates miR-146, which suppresses breast cancer metastasis. Cancer Res. 69, 1279–1283. doi:10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-3559

Jenike, A., and Ehalushka, M. K. (2021). miR-21: a non-specific biomarker of all maladies. Biomark. Res. 9, 18. doi:10.1186/s40364-021-00272-1

Jia, Y. W. Y., and Wei, Y. (2020). Modulators of MicroRNA function in the immune System. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 21, 2357. doi:10.3390/ijms21072357

Jiang, S., Zhang, L. F., Zhang, H. W., Hu, S., Lu, M. H., Liang, S., et al. (2012). A novel miR-155/miR-143 cascade controls glycolysis by regulating hexokinase 2 in breast cancer cells. Embo J. 31, 1985–1998. doi:10.1038/emboj.2012.45

Jin, X. X., Gao, C., Wei, W. X., Jiao, C., Li, L., Ma, B. L., et al. (2022). The role of microRNA-4723-5p regulated by c-myc in triple-negative breast cancer. Bioengineered 13, 9097–9105. doi:10.1080/21655979.2022.2056824

Jordan-Alejandre, E., Campos-Parra, A. D., Castro-López, D., and Lsilva-Cázares, M. B. (2023). Potential miRNA use as a biomarker: from breast cancer diagnosis to metastasis. Cells 12, 525. doi:10.3390/cells12040525

Kenkre, J., and Sbassett, J. (2018). The bone remodelling cycle. Ann. Clin. Biochem. 55, 308–327. doi:10.1177/0004563218759371

Kessenbrock, K., and Plaks Vwerb, Z. (2010). Matrix metalloproteinases: regulators of the tumor microenvironment. Cell. 141, 52–67. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2010.03.015

Kitayama, K., Kawamoto, T., Kawakami, Y., Hara, H., Takemori, T., Fujiwara, S., et al. (2021). Regulatory roles of miRNAs 16, 133a, and 223 on osteoclastic bone destruction caused by breast cancer metastasis. Int. J. Oncol. 59, 97. doi:10.3892/ijo.2021.5277

Kundaktepe, B. P., Sozer, V., Kundaktepe, F. O., Durmus, S., Papila, C., Uzun, H., et al. (2021). Association between bone mineral density and bone turnover markers in breast cancer patients and bone-only metastasis. Med. Kaunas. 57, 880. doi:10.3390/medicina57090880

Le Fur, M., Ross, A., Pantazopoulos, P., Rotile, N., Zhou, I., Caravan, P., et al. (2021). Radiolabeling and PET-MRI microdosing of the experimental cancer therapeutic, MN-anti-miR10b, demonstrates delivery to metastatic lesions in a murine model of metastatic breast cancer. Cancer Nanotechnol. 12, 16. doi:10.1186/s12645-021-00089-5

Lee, R. C., Feinbaum, R., and Lambros, V. (1993). The C. elegans heterochronic gene lin-4 encodes small RNAs with antisense complementarity to lin-14. Cell. 75, 843–854. doi:10.1016/0092-8674(93)90529-y

Li, Y., and Su Xpan, H. (2019). Inhibition of lncRNA PANDAR reduces cell proliferation, cell invasion and suppresses EMT pathway in breast cancer. Cancer Biomark. 25, 185–192. doi:10.3233/CBM-182251

Li, Z., Xiao, X., Pu, X., Yang, X., Shi, J., He, S., et al. (2025). Bone-Targeting nucleic acid delivery polymer vector for effective therapy of bone metastasis. ACS Nano 19, 17014–17027. doi:10.1021/acsnano.5c04743

Liang, Y., Zhang, H., and Song Xyang, Q. (2020). Metastatic heterogeneity of breast cancer: molecular mechanism and potential therapeutic targets. Semin. Cancer Biol. 60, 14–27. doi:10.1016/j.semcancer.2019.08.012

Liu, J., Li, D., Dang, L., Liang, C., Guo, B., Lu, C., et al. (2017). Osteoclastic miR-214 targets TRAF3 to contribute to osteolytic bone metastasis of breast cancer. Sci. Rep. 7, 40487. doi:10.1038/srep40487

Liu, X., Cao, M., Palomares, M., Wu, X., Li, A., Yan, W., et al. (2018). Metastatic breast cancer cells overexpress and secrete miR-218 to regulate type I collagen deposition by osteoblasts. Breast Cancer Res. 20, 127. doi:10.1186/s13058-018-1059-y

Loh, H. Y., Norman, B. P., Lai, K. S., Rahman, N., Alitheen, N. B., and Mosman, M. A. (2019). The regulatory role of MicroRNAs in breast cancer. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 20, 4940. doi:10.3390/ijms20194940

Luo, L. J., Yang, F., Ding, J. J., Yan, D. L., Wang, D. D., Yang, S. J., et al. (2016). MiR-31 inhibits migration and invasion by targeting SATB2 in triple negative breast cancer. Gene 594, 47–58. doi:10.1016/j.gene.2016.08.057

Ma, L., and Teruya-Feldstein Jweinberg, R. A. (2007). Tumour invasion and metastasis initiated by microRNA-10b in breast cancer. Nature 449, 682–688. doi:10.1038/nature06174

Ma, Y., Shepherd, J., Zhao, D., Bollu, L. R., Tahaney, W. M., Hill, J., et al. (2020). SOX9 is essential for triple-negative breast cancer cell survival and metastasis. Mol. Cancer Res. 18, 1825–1838. doi:10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-19-0311

Marazzi, F., Orlandi, A., Manfrida, S., Masiello, V., Di Leone, A., Massaccesi, M., et al. (2020). Diagnosis and treatment of bone metastases in breast cancer: radiotherapy, local approach and systemic therapy in a guide for clinicians. Cancers (Basel) 12, 2390. doi:10.3390/cancers12092390

Mashouri, L., Yousefi, H., Aref, A. R., Ahadi, A. M., and Molaei Falahari, S. K. (2019). Exosomes: composition, biogenesis, and mechanisms in cancer metastasis and drug resistance. Mol. Cancer 18, 75. doi:10.1186/s12943-019-0991-5

Mohammedi, L., Doula, F. D., and Mesli Fsenhadji, R. (2019). Cyclin D1 overexpression in Algerian breast cancer women: correlation with CCND1 amplification and clinicopathological parameters. Afr. Health Sci. 19, 2140–2146. doi:10.4314/ahs.v19i2.38

Mollaei, H., and Safaralizadeh Rrostami, Z. (2019). MicroRNA replacement therapy in cancer. J. Cell. Physiol. 234, 12369–12384. doi:10.1002/jcp.28058

Nassar, F. J., and Nasr Rtalhouk, R. (2017). MicroRNAs as biomarkers for early breast cancer diagnosis, prognosis and therapy prediction. Pharmacol. Ther. 172, 34–49. doi:10.1016/j.pharmthera.2016.11.012

Obaya, A. J., Kotenko, I., Cole, M., and Dsedivy, J. M. (2002). The proto-oncogene c-myc acts through the cyclin-dependent kinase (Cdk) inhibitor p27(Kip1) to facilitate the activation of Cdk4/6 and early G(1) phase progression. J. Biol. Chem. 277, 31263–31269. doi:10.1074/jbc.M202528200

Ochiya, T., and Hashimoto Kshimomura, A. (2025). Prospects for liquid biopsy using microRNA and extracellular vesicles in breast cancer. Breast Cancer 32, 10–15. doi:10.1007/s12282-024-01563-9

Ouzounova, M., Vuong, T., Ancey, P. B., Ferrand, M., Durand, G., Le-Calvez, K. F., et al. (2013). MicroRNA miR-30 family regulates non-attachment growth of breast cancer cells. BMC Genomics 14, 139. doi:10.1186/1471-2164-14-139

Pang, Y., Liu, J., Li, X., Xiao, G., Wang, H., Yang, G., et al. (2018). MYC and DNMT3A-mediated DNA methylation represses microRNA-200b in triple negative breast cancer. J. Cell. Mol. Med. 22, 6262–6274. doi:10.1111/jcmm.13916

Pollari, S., Leivonen, S. K., Perala, M., Fey, V., Kakonen, S., and Mkallioniemi, O. (2012). Identification of microRNAs inhibiting TGF-beta-induced IL-11 production in bone metastatic breast cancer cells. PLoS One 7, e37361. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0037361

Puppo, M., Taipaleenmäki, H., Hesse Eclézardin, P., and Clézardin, P. (2021). Non-coding RNAs in bone remodelling and bone metastasis: mechanisms of action and translational relevance. Br. J. Pharmacol. 178, 1936–1954. doi:10.1111/bph.14836

Puppo, M., Valluru, M. K., Croset, M., Ceresa, D., Iuliani, M., Khan, A., et al. (2023). MiR-662 is associated with metastatic relapse in early-stage breast cancer and promotes metastasis by stimulating cancer cell stemness. Br. J. Cancer 129, 754–771. doi:10.1038/s41416-023-02340-9

Puppo, M., Croset, M., Ceresa, D., Valluru, M. K., Canuas Landero, V. G., Hernandez, G. M., et al. (2024). Protective effects of miR-24-2-5p in early stages of breast cancer bone metastasis. Breast Cancer Res. 26, 186. doi:10.1186/s13058-024-01934-2

Roth, C., Rack, B., Müller, V., Janni, W., and Pantel Kschwarzenbach, H. (2010). Circulating microRNAs as blood-based markers for patients with primary and metastatic breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res. 12, R90. doi:10.1186/bcr2766

Sahay, D., Leblanc, R., Grunewald, T. G., Ambatipudi, S., Ribeiro, J., Clézardin, P., et al. (2015). The LPA1/ZEB1/miR-21-activation pathway regulates metastasis in basal breast cancer. Oncotarget 6, 20604–20620. doi:10.18632/oncotarget.3774

Salvador, F., and Llorente, A. G. R. R. (2019). From latency to overt bone metastasis in breast cancer: potential for treatment and prevention. J. Pathol. 249, 6–18. doi:10.1002/path.5292

Shibabaw, T., and Teferi Bayelign, B. (2023). The role of Th-17 cells and IL-17 in the metastatic spread of breast cancer: as a means of prognosis and therapeutic target. Front. Immunol. 14, 1094823. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2023.1094823

Shimomura, A., Shiino, S., Kawauchi, J., Takizawa, S., Sakamoto, H., Matsuzaki, J., et al. (2016). Novel combination of serum microRNA for detecting breast cancer in the early stage. Cancer Sci. 107, 326–334. doi:10.1111/cas.12880

Shin Ekoo, J. S., and Koo, J. S. (2020). The role of adipokines and bone marrow adipocytes in breast cancer bone metastasis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 21, 4967. doi:10.3390/ijms21144967

Shuaib, M. K. S., and Kumar, S. (2023). Induced expression of miR-1250-5p exerts tumor suppressive role in triple-negative breast cancer cells. J. Cell. Biochem. 124, 282–293. doi:10.1002/jcb.30362

Slack, F. R. G., and Ruvkun, G. (1997). Temporal pattern formation by heterochronic genes. Annu. Rev. Genet. 31, 611–634. doi:10.1146/annurev.genet.31.1.611

Song, X., and Wei Cli, X. (2022). The signaling pathways associated with breast cancer bone metastasis. Front. Oncol. 12, 855609. doi:10.3389/fonc.2022.855609

Song, X., Zhang, X., Wang, X., Chen, L., Jiang, L., Zheng, A., et al. (2019). LncRNA SPRY4-IT1 regulates breast cancer cell stemness through competitively binding miR-6882-3p with TCF7L2. J. Cell. Mol. Med. 24, 772–784. doi:10.1111/jcmm.14786

Sui, L., Sanders, A., Jiang, W., and Gye, L. (2022). Deregulated molecules and pathways in the predisposition and dissemination of breast cancer cells to bone. Comput. Struct. Biotechnol. J. 20, 2745–2758. doi:10.1016/j.csbj.2022.05.051

Sun, Z., Hu, J., Ren, W., Fang, Y., Hu, K., Yu, H., et al. (2022). LncRNA SNHG3 regulates the BMSC osteogenic differentiation in bone metastasis of breast cancer by modulating the miR-1273g-3p/BMP3 axis. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 594, 117–123. doi:10.1016/j.bbrc.2021.12.075

Swellam, M., Zahran, R. F. K., Ghonem, S., and Aabdel-Malak, C. (2021). Serum MiRNA-27a as potential diagnostic nucleic marker for breast cancer. Arch. Physiol. Biochem. 127, 90–96. doi:10.1080/13813455.2019.1616765

Taipaleenmäki, H., Browne, G., Akech, J., Zustin, J., van Wijnen, A. J., Stein, J. L., et al. (2015). Targeting of Runx2 by miR-135 and miR-203 Impairs Progression of breast cancer and metastatic bone disease. Cancer Res. 75, 1433–1444. doi:10.1158/0008-5472.can-14-1026

Taipaleenmäki, H., Farina, N. H., van Wijnen, A. J., Stein, J. L., Hesse, E., Stein, G. S., et al. (2016). Antagonizing miR-218-5p attenuates Wnt signaling and reduces metastatic bone disease of triple negative breast cancer cells. Oncotarget 7, 79032–79046. doi:10.18632/oncotarget.12593

Tian, H., Cheng, L., Liang, Y., Lei, H., Qin, M., Li, X., et al. (2024). MicroRNA therapeutic delivery strategies: a review. J. Drug Deliv. Sci. Technol. 93, 105430. doi:10.1016/j.jddst.2024.105430

Vimalraj, S., Miranda, P. J., and Ramyakrishna Bselvamurugan, N. (2013). Regulation of breast cancer and bone metastasis by microRNAs. Dis. Markers 35, 369–387. doi:10.1155/2013/451248

Vishal, M., Swetha, R., Thejaswini, G., and Arumugam Bselvamurugan, N. (2017). Role of Runx2 in breast cancer-mediated bone metastasis. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 99, 608–614. doi:10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2017.03.021

Vittori, C., Jeansonne, D., Yousefi, H., Faia, C., Lin, Z., Reiss, K., et al. (2022). Mechanisms of miR-3189-3p-mediated inhibition of c-MYC translation in triple negative breast cancer. Cancer Cell. Int. 22, 204. doi:10.1186/s12935-022-02620-z

Wang, F., Lv, P., Liu, X., and Zhu, M. Q. X. (2015). microRNA-214 enhances the invasion ability of breast cancer cells by targeting p53. Int. J. Mol. Med. 35, 1395–1402. doi:10.3892/ijmm.2015.2123

Wang, Q. Y., Zhou, C. X., Zhan, M. N., Tang, J., Wang, C. L., Ma, C. N., et al. (2018). MiR-133b targets Sox9 to control pathogenesis and metastasis of breast cancer. Cell. Death Dis. 9, 752. doi:10.1038/s41419-018-0715-6

Wang, J., Li, M., Han, X., Wang, H., Wang, X., Ma, G., et al. (2020a). MiR-1976 knockdown promotes epithelial-mesenchymal transition and cancer stem cell properties inducing triple-negative breast cancer metastasis. Cell. Death Dis. 11, 500. doi:10.1038/s41419-020-2711-x

Wang, C., Pang, L., Shi, Q., and Liu Xliu, Y. (2020b). The diagnostic value of serum miR-129 in breast cancer patients with bone metastasis. Clin. Lab. 66. doi:10.7754/Clin.Lab.2019.190438

Weis, S., and Mcheresh, D. A. (2011). Tumor angiogenesis: molecular pathways and therapeutic targets. Nat. Med. 17, 1359–1370. doi:10.1038/nm.2537

Ye, Z. B., Ma, G., Zhao, Y. H., Xiao, Y., Zhan, Y., Jing, C., et al. (2015). miR-429 inhibits migration and invasion of breast cancer cells in vitro. Int. J. Oncol. 46, 531–538. doi:10.3892/ijo.2014.2759

Ying, M., Mao, J., Sheng, L., Wu, H., Bai, G., Zhong, Z., et al. (2023). Biomarkers for prostate cancer bone metastasis detection and prediction. J. Pers. Med. 13, 705. doi:10.3390/jpm13050705

Yu, Z., Wang, C., Wang, M., Li, Z., Casimiro, M. C., Liu, M., et al. (2008). A cyclin D1/microRNA 17/20 regulatory feedback loop in control of breast cancer cell proliferation. J. Cell. Biol. 182, 509–517. doi:10.1083/jcb.200801079

Yu, Y., Yao, Y., Yan, H., Wang, R., Zhang, Z., Sun, X., et al. (2016). A tumor-specific MicroRNA recognition System facilitates the accurate targeting to tumor cells by magnetic nanoparticles. Mol. Ther. Nucleic Acids 5, e318. doi:10.1038/mtna.2016.28

Zhang, M., Dong, B. B., Lu, M., Zheng, M. J., Chen, H., Ding, J. Z., et al. (2016). miR-429 functions as a tumor suppressor by targeting FSCN1 in gastric cancer cells. Onco Targets Ther. 9, 1123–1133. doi:10.2147/OTT.S91879

Zhang, L., Zhang, X., Wang, X., and He Mqiao, S. (2019). MicroRNA-224 promotes tumorigenesis through downregulation of Caspase-9 in triple-negative breast cancer. Dis. Markers 2019, 7378967. doi:10.1155/2019/7378967

Zhang, X., Yu, X., Zhao, Z., Yuan, Z., Ma, P., Ye, Z., et al. (2020a). MicroRNA-429 inhibits bone metastasis in breast cancer by regulating CrkL and MMP-9. Bone 130, 115139. doi:10.1016/j.bone.2019.115139

Zhang, L., Liu, Q., Mu, Q., Zhou, D., Li, H., Zhang, B., et al. (2020b). MiR-429 suppresses proliferation and invasion of breast cancer via inhibiting the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway. Thorac. Cancer 11, 3126–3138. doi:10.1111/1759-7714.13620

Zhang, L. F., Zhang, J. G., Zhou, H., Dai, T. T., Guo, F. B., Xu, S. Y., et al. (2020c). MicroRNA-425-5p promotes breast cancer cell growth by inducing PI3K/AKT signaling. Kaohsiung J. Med. Sci. 36, 250–256. doi:10.1002/kjm2.12148

Zhao, F. L., Hu, G. D., Wang, X. F., Zhang, X. H., Zhang, Y., and Kyu, Z. S. (2012). Serum overexpression of microRNA-10b in patients with bone metastatic primary breast cancer. J. Int. Med. Res. 40, 859–866. doi:10.1177/147323001204000304

Zhao, X. G., Hu, J. Y., Tang, J., Yi, W., Zhang, M. Y., Deng, R., et al. (2019). miR-665 expression predicts poor survival and promotes tumor metastasis by targeting NR4A3 in breast cancer. Cell. Death Dis. 10, 479. doi:10.1038/s41419-019-1705-z

Zhou, J., and Tulotta Cottewell, P. D. (2022). IL-1β in breast cancer bone metastasis. Expert Rev. Mol. Med. 24, e11. doi:10.1017/erm.2022.4

Zhu, S., Si, M. L., and Wu Hmo, Y. Y. (2007). MicroRNA-21 targets the tumor suppressor gene tropomyosin 1 (TPM1). J. Biol. Chem. 282, 14328–14336. doi:10.1074/jbc.M611393200

Zhu, J., Dai, H., Li, X., Guo, L., Sun, X., Zheng, Z., et al. (2023). LncRNA TRG-AS1 inhibits bone metastasis of breast cancer by the miR-877-5p/WISP2 axis. Pathol. Res. Pract. 243, 154360. doi:10.1016/j.prp.2023.154360

Zoni Evan der Pluijm, G., and van der Pluijm, G. (2016). The role of microRNAs in bone metastasis. J. Bone Oncol. 5, 104–108. doi:10.1016/j.jbo.2016.04.002

Keywords: miRNAs, breast cancer, bone metastasis, targeted therapy, bone microenvironment

Citation: Meng F, Zhang M, Pu D, Shi G and Li J (2025) Dual-regulatory miRNAs: master regulators and therapeutic targets in bone-metastatic breast cancer. Front. Mol. Biosci. 12:1680908. doi: 10.3389/fmolb.2025.1680908

Received: 06 August 2025; Accepted: 13 October 2025;

Published: 28 October 2025.

Edited by:

Wenyong Yang, Chengdu Third People’s Hospital, ChinaReviewed by:

Laura Duran-Lozano, Vall d’Hebron Institute of Oncology (VHIO), SpainKumar Subramanian, Georgetown University, United States

Copyright © 2025 Meng, Zhang, Pu, Shi and Li. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Jingwei Li, NzEwMDAzOTVAc2R1dGNtLmVkdS5jbg==

Feifei Meng

Feifei Meng Mengdi Zhang

Mengdi Zhang Dongqing Pu2

Dongqing Pu2