Abstract

SR proteins are RNA-binding proteins with one or two RNA recognition motif (RRM)-type RNA-binding domains and a C-terminal region rich in arginine-serine dipeptides. They function in cellular processes ranging from transcription to translation. The best-known SR protein, SRSF1, modulates RNA splicing by stabilizing the binding of constitutive splicing factors, but there is also evidence that it participates in constitutive splicing reactions and is present in spliceosomal complexes. It has been shown recently that it interacts with DDX23, an RNA helicase that triggers the transition from complex pre-B to complex B during activation of the spliceosome. To identify in which other steps of spliceosome assembly and reaction it might be present, we have used split-APEX with SRSF1 and a number of helicases, each of the latter being involved in a particular step. Peroxidase activity should only be reconstituted if SRSF1 and the helicase were in contact, and the consequent biotinylation should reveal proteins in the vicinity. Our results show that all the helicases tested can complement SRSF1, but that the proximal proteins are very similar in all cases. Moreover, the proteins identified fall into two major classes: splicing-related proteins and ribosomal proteins. The results raise the possibility that SRSF1 and the canonical helicases have hitherto unsuspected collaborative roles in ribosomal assembly or translation.

Introduction

SRSF1 was first identified as both an essential splicing factor, required to complement cytoplasmic extracts to enable them to splice pre-mRNA in vitro (Krainer et al., 1990), and an alternative splicing factor involved in 5′SS selection (Ge and Manley, 1990), but it has been shown subsequently to have roles also in transcription, nuclear export, control of translation, nonsense-mediated decay, X-chromosome inactivation and genome stability (Arif et al., 2023; Das and Krainer, 2014; Ji et al., 2013; Long and Caceres, 2009; Maslon et al., 2014; Muller-McNicoll et al., 2016; Paz et al., 2014; Paz et al., 2021; Sliskovic et al., 2022; Trotman et al., 2025). Interactome studies have shown that SRSF1 is promiscuous: it associates directly or indirectly with over 30 other spliceosomal proteins(Akerman et al., 2015), as well as a number of proteins involved in other processes (Das and Krainer, 2014), and BioGRID lists 590 interactions.

The best-understood action of SRSF1 is as an activator of exon inclusion during splicing. It binds purine-rich enhancer sequences (Anczukow et al., 2015; Clery et al., 2021; Lavigueur et al., 1993; Sanford et al., 2009; Sun et al., 1993; Tacke and Manley, 1995) and stabilizes the binding of core splicing components at the 5′and 3′splice sites via protein-protein interactions (Eperon et al., 1993; Eperon et al., 2000; Kohtz et al., 1994; Lavigueur et al., 1993; Staknis and Reed, 1994; Tarn and Steitz, 1995; Wang and Manley, 1995; Wu and Maniatis, 1993). We have inferred from single molecule experiments that there is a low probability that an ESE is occupied at any moment by SRSF1, but that interactions with the splicing components by 3D diffusion stabilize a complex (Jobbins et al., 2018). Interestingly, however, SRSF1 can also be recruited to 5′splice sites by U1 snRNPs (Jamison et al., 1995; Jobbins et al., 2022), to which it binds by protein-RNA and protein-protein interactions (Jobbins et al., 2022; Kohtz et al., 1994; Paul et al., 2024; Xiao and Manley, 1998). This interaction may facilitate exon definition by a 5′SS, if the bound SRS1 interacts across the exon, or it may stabilize U1 snRNP binding to the pre-mRNA and thereby affect 5′splice site selection (Eperon et al., 1993; Jobbins et al., 2022).

Other findings suggest that SRSF1 may have a role in the spliceosome itself. SRSF1 RRM2 has been found in structures of the pre-Bact spliceosome (Townsend et al., 2020). Recent work has shown that there is also a direct interaction between SRSF1 and DDX23 (Segovia et al., 2024), a DEAD-box helicase that enters the spliceosome with the tri-snRNP and displaces the U1 snRNP during the pre-B to B complex transition (Charenton et al., 2019; Zhang Z. et al., 2024). In this case, the interaction of SRSF1 with both the U1 snRNP and DDX23 might facilitate docking of the U1 snRNP and the 5′splice site to DDX23 in the tri-snRNP in the pre-B complex, prior to displacement of the U1 snRNP. The role of SRSF1 may extend beyond the early stages alone, though, since the addition of SRSF1 or an RNA-tethered RS domain to a cytoplasmic extract led to contacts between the RS domain and the 5′splice site, branchpoint or 5′exon of the pre-mRNA in spliceosomal complexes A, B and C (Shen and Green, 2004; 2007). If SRSF1 does contact DDX23 in the spliceosome and remains after DDX23 leaves, we reasoned that it might come into very close proximity with the succession of other helicases that drive spliceosomal transitions and reactions (Dorner and Hondele, 2024; Enders et al., 2023; Wan et al., 2019; Wilkinson et al., 2020). Some support for this possibility comes from high-throughput screens that have linked SRSF1 with a number of helicases (Havugimana et al., 2012; Hein et al., 2015; Huttlin et al., 2021).

Molecular proximity can be tested by split-APEX, in which ascorbate peroxidase activity is reconstituted from two fragments fused to other proteins when the fragments are brought together by intermolecular interactions (Han et al., 2019). If biotin tyramide is supplied, peroxidase activity would generate short-lived radicals that biotinylate nearby proteins. Thus, the detection of biotinylated proteins would confirm that the two fragments of APEX2 had been brought together to enable the full protein to be reconstituted and, in addition, would provide an indication of the local protein environment when reconstitution occurs. We describe results here that show that SRSF1 does interact with helicases involved at all stages of pre-mRNA splicing, but these interactions take place in very similar environments, not necessarily in the spliceosome, and raise the possibility that SRSF1 and the helicases are involved in ribosomal biogenesis.

Results

Split-APEX involves the separate fusion of two portions of a modified soybean ascorbate peroxidase (APEX2) to the two proteins being interrogated. The N-terminal and C-terminal portions (AP and EX respectively) are ∼200 and 50 amino acids in length, and had been selected for a low affinity for each other (Huttlin et al., 2021). They were cloned at the N-terminal side of full-length SRSF1, DDX46, DDX23, DHX16, DHX38, DHX8 and, as controls for intranuclear location, the speckle factor SRRM2 (Ilik et al., 2020) and the nuclear export factor TNPO3, the latter of which associates directly with SRSF1 during nuclear import (Maertens et al., 2014) (Supplementary Figure S1). DDX46 (an othologue of yeast Prp5) is a component of the U2 snRNP, associated with SF3B1 and plays critical roles in complex A formation (Perriman et al., 2003; Talkish et al., 2019; Yang et al., 2023; Zhang X. et al., 2024; Zhang et al., 2020); DDX23 (yeast Prp28) is a component of the tri-snRNP, required for displacement of the U1 snRNP during the transition from the pre-B to the B complex (Boesler et al., 2016; Charenton et al., 2019; Staley and Guthrie, 1999; Zhang Z. et al., 2024); DHX16 (yeast Prp2), in conjunction with the helicase Aquarius, is required for the step in assembly during which the branch site enters the active site and the catalytic B*/C complex forms (Kim and Lin, 1996; King and Beggs, 1990; Krishnan et al., 2013; Schmitzova et al., 2023; Zhan et al., 2024); DHX38 (yeast Prp16) replaces DHX16 in the spliceosome and rearranges the active site from a step 1 configuration in complex C to that required for step 2 in complex C* (Bertram et al., 2017; Fica et al., 2017; Schwer and Guthrie, 1992; Semlow et al., 2016; Wilkinson et al., 2021; Zhan et al., 2024; Zhan et al., 2018); DHX8 (yeast Prp22) replaces DHX38, and triggers dissociation of the spliced mRNA, leaving a spliceosome containing the lariat intron (Bertram et al., 2017; Company et al., 1991; Fica et al., 2017; Liu et al., 2017; McPheeters and Muhlenkamp, 2003; Schwer, 2008; Zhan et al., 2022); DDX48 (eIF4A3) plays an important role in assembling the post-splicing exon junction complex (Chan et al., 2004; Gehring et al., 2005). All the proteins were fused separately to both the AP and the EX fragments of APEX2. An additional control included the fusion of intact APEX2 to SRSF1.

To determine the optimal configuration of AP and EX fusions for each pair, both combinations were transfected into HEK293T cells and the levels of biotinylation assessed by Western blotting of the lysates. Control experiments with DDX46 and SRSF1 showed that there was no biotinylation if either the AP or EX fusions were transfected on their own (Supplementary Figure S2). When the AP and EX fusions were transfected together, successful biotinylation was seen (Supplementary Figure S2; Figure 1); the level was generally higher when SRSF1 was fused to the short EX fragment of APEX2, except when used in pairs with DHX38 and SRRM2, when SRSF1 was fused to the AP fragment. The optimal combinations were used in subsequent experiments. The functional activity of these SRSF1 fusions was tested by analysing their ability to enhance splicing of an intron in the 3′UTR of the SRSF1 pre-mRNA, an activity that mediates some autoregulation of SRSF1 expression (Ding et al., 2022; Lareau et al., 2007; Sun et al., 2010). All of the combinations being used resulted in increased levels of the spliced mRNA (Supplementary Figure S3).

FIGURE 1

Effects of split-APEX combinations on the efficiency of biotinylation. AP or EX fragments of APEX2 fused to SRSF1 were co-transfected into HEK293T cells with EX or AP fragments fused to the helicases, TNPO3 or SRRM2. Cells were lysed in 8 M urea and the equivalent of 40 µg of total protein content was analysed by SDS-PAGE. Biotinylation was detected by Western blotting with dye-labelled streptavidin (upper panel) and equal loading and transfer were shown by staining the membrane with Ponceau S (lower panel).

Following scaled-up transfections, the levels of expression of the fusion protein compared with the endogenous protein were determined by Western blotting of the lysate (Supplementary Figure S4). In all cases, expression of the EX fragment fusion protein (usually SRSF1) was undetectable, and that of the AP fragment fusions was in most cases no higher than the level of the endogenous protein, with the exceptions of AP-DHX8 and AP-TNPO3. The very low levels of expression of the EX fusions reduce the probability that the APEX fragments would associate in the cell by collisions resulting from free diffusion rather than by being bound in close proximity. Biotinylated proteins were recovered from the lysates and analysed by MS/MS mass spectrometry. In addition, two further replicates were done for each combination, so altogether three independent experiments were analysed (Supplementary Figure S5). Every experiment included three negative controls, in which the cells had not been transfected but had been treated otherwise as the transfected cells. Scaffold software was used to produce a total spectral count for each protein identified, and this was used to estimate the relative yields of each protein in different samples (Old et al., 2005; Schmidt et al., 2014).

The lists of proteins identified in each condition contained only those proteins found in at least two replicates. In addition, the lists were edited to remove keratin, tubulin, actin and endogenously biotinyated proteins (Niers et al., 2011), which were the only proteins found in the negative control samples. The lists comprised 106, 138, 104, 113, 140, 97, 137 and 69 proteins respectively for the combinations of SRSF1 with the targets DDX46, DDX23, DHX16, DDX48, DHX38, DHX8, TNPO3 and SRRM2 (Figure 2; Supplementary Table S1). This compares with 917 proteins labelled by the full-length APEX fused to SRSF1, suggesting that the SRSF1-helicase combinations were either less efficient or labelled a restricted set of proteins. UpSet plots show the numbers of proteins common to two or more experiments (Figure 3). Strikingly, all the split-APEX experiments labelled a core set of 66 proteins, and the SRSF1-helicase combinations labelled an additional 18, producing 84 proteins that were common to all the SRSF1-helicase combinations (Figure 2; Supplementary Table S2).

FIGURE 2

(A) List of proteins found with at least one combination of an SRSF1 fusion to AP or EX and a helicase, TNPO3 or SRRM2 fused to EX or AP. Each combination was tested in three separate experiments, and each dataset lists proteins found in at least two experiments. These proteins are arranged in blocks according to the number of datasets in which the proteins were found, indicated by the depth of colour of the block. (B) The proteins in the DDX46-SRSF1 dataset are listed in blocks according to the number of other helicase datasets in which they were found. Within each block the proteins are ranked according to the total 679 spectral counts of each protein (highest at the top; dark purple). The same proteins in the other datasets are coloured according to their ranking in the total spectral counts in that dataset.

FIGURE 3

Similarities and differences among datasets. An UpSet plot shows the numbers of proteins found in each of the possible combinations of the datasets. Bar charts show the numbers of proteins in each dataset and the numbers found in any particular combination of datasets.

To compare the sets of proteins, the proteins in each set were ranked according to their total spectral count. Both SRSF1 and the tagged helicase appeared in the top 10 hits of each SRSF1/helicase set, as might be expected. However, in most cases the helicases do not appear in the sets generated using other helicases (e.g., DDX46 appears only when it was tagged, and not in the sets from SRSF1/DDX23, etc.). The only exception is DDX48 (eIF4A3), which does appear in the SRSF1/DDX23 set. In contrast, all the helicases were recovered in the APEX2-SRSF1 set. One possible inference is that each helicase interacts with SRSF1 only when the other helicases are not in close proximity. TNPO3 was identified only in the SRSF1/TNPO3 experiment, where it was ranked only 37th, and it was not in the APEX2-SRSF1 set. SRRM2 did not appear in the SRRM2/SRSF1 experiment, and in the APEX2-SRSF1 set it was not ranked highly. Other helicases appear more abundantly: DDX5, DDX17 and DHX9 are abundant in all of the sets. The highest-ranking proteins generally are the hnRNPs: A1, A2B1, K and H1.

The ranked sets were compared pair-wise in diagonal plots to assess their overall similarity. Strikingly, the proteins in common between any two helicase-SRSF1 combinations showed clear convergence towards the line expected if the ranks were identical (Figures 4–7). To test whether rankings depended on the helicase partner or were merely the outcome of labelling directed by SRSF1, the common factor in all the tests, the ranked sets were plotted against the ranked set produced by APEX2-SRSF1 alone (Figure 8). Some of these plots showed no apparent correlation, apart from a possible cluster of highly abundant proteins near the origin (SRSF1, of course, and hnRNPs A1, A2B1, and K), such as the plots of APEX2-SRSF1 hits vs. combinations of SRSF1/DDX46, SRSF1/DDX48 and SRSF1/SRRM2.

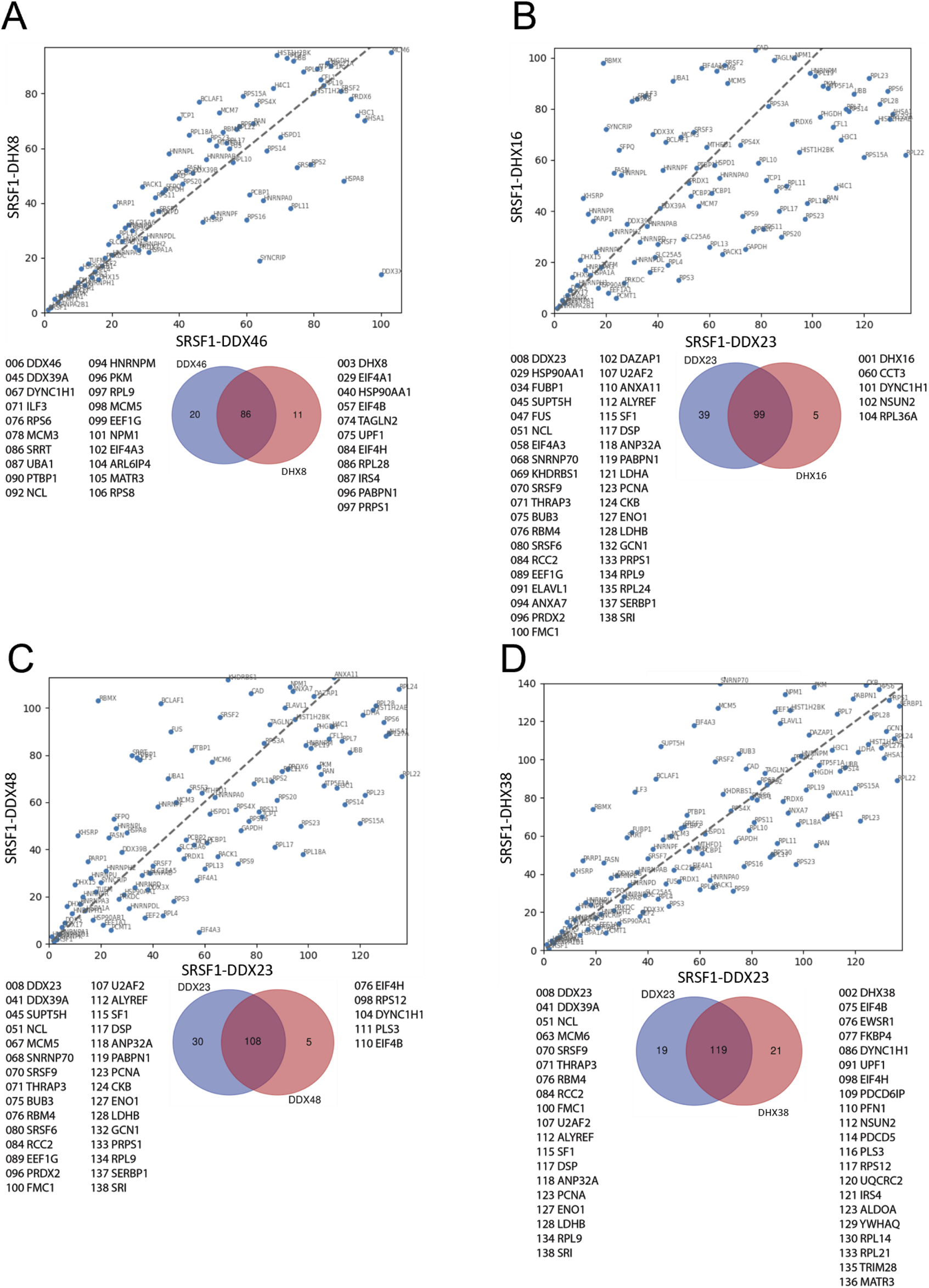

FIGURE 4

Comparisons between the ranking of proteins in different SRSF1-helicase datasets. The diagonal plots are based on the ranking of proteins in each of two datasets. Venn diagrams were used to identify the differences in the presence/absence of proteins between the datasets. The adjacent lists show the proteins that are unique to each member of the pair. Numbers in front of the proteins indicate the ranking position. (A) SRSF1+DDX46 vs. SRSF1+DDX23. (B) SRSF1+DDX46 vs. SRSF1+DHX16 comparison. (C) SRSF1+DDX46 vs. SRSF1+DDX48. (D) SRSF1+DDX46 vs. SRSF1+DHX38.

FIGURE 5

Comparisons between the ranking of proteins in different SRSF1-helicase datasets. The diagonal plots are based on the ranking of proteins in each of two datasets. Venn diagrams were used to identify the differences in the presence/absence of proteins between the datasets. The adjacent lists show the proteins that are unique to each member of the pair. Numbers in front of the proteins indicate the ranking position. (A) SRSF1+DDX46 vs. SRSF1+DHX8. (B) SRSF1+DDX23 vs. SRSF1+DHX16. (C) SRSF1+DX23 vs. SRSF1+DDX48. (D) SRSF1+DDX23 vs. SRSF1+DHX38.

FIGURE 6

Comparisons between the ranking of proteins in different SRSF1-helicase datasets. The diagonal plots are based on the ranking of proteins in each of two datasets. Venn diagrams were used to identify the differences in the presence/absence of proteins between the datasets. The adjacent lists show the proteins that are unique to each member of the pair. Numbers in front of the proteins indicate the ranking position. (A) SRSF1+DDX23 vs. SRSF1+DHX8. (B) SRSF1+DHX16 vs. SRSF1+DDX48. (C) SRSF1+DHX16 vs. SRSF1+DHX38. (D) SRSF1+DHX16 vs. SRSF1+DHX8.

FIGURE 7

Comparisons between the ranking of proteins in different SRSF1-helicase datasets. The diagonal plots are based on the ranking of proteins in each of two datasets. Venn diagrams were used to identify the differences in the presence/absence of proteins between the datasets. The adjacent lists show the proteins that are unique to each member of the pair. Numbers in front of the proteins indicate the ranking position. (A) SRSF1+DDX48 vs. SRSF1+DHX38. (B) SRSF1+DDX48 vs. SRSF1+DHX8. (C) SRSF1+DHX38 vs. SRSF1+DHX8.

FIGURE 8

Diagonal plots comparing the rankings of proteins in common between the APEX2-SRSF1 and the split-APEX2 datasets. The ordinate shows proteins ranked in the APEX2-SRSF1 dataset, and the abscissa shows proteins ranked in the split-APEX2 dataset.

To test further whether the results might be consequent upon sequestration into speckles by SRSF1, the lists were compared with previous data in which proteins enriched in speckles were determined by indirect peroxidase labelling (Dopie et al., 2020) (Figure 9). No correlation was observed. Even the SRSF1/SRRM2 combination did not label SRRM2 or SON, which are major speckle factors (Dopie et al., 2020; Ilik et al., 2020). Another possibility is that the results reflected the concentrations of proteins in the cells and that the limited numbers of proteins found simply reflected a limiting efficiency. Thus, the lists were compared with the results with previous measurements of protein abundance in HeLa cells (Hein et al., 2015), although these was not based on peroxidase labelling, but again no correlation was observed (Supplementary Figure S6). The results therefore suggest that the sites in the cell at which SRSF1 comes into contact with helicases, SRRM2 or TNPO3 are in some sense unique.

FIGURE 9

Diagonal plots comparing the rankings of proteins in common between a previously-reported APEX dataset from speckles (Dopie et al., 2020) and the split-APEX2 datasets.

Among the 84 proteins common to all the SRSF1-helicase pairs, gene ontology analysis based on biological process revealed a very marked enrichment of terms related to translation and splicing (Figure 10A; Supplementary Table S2), whereas the 917 proteins labelled with full-length APEX2 fused to SRSF1 were predominantly assigned to splicing or RNA processing (Figure 10B). Likewise, an analysis of molecular function showed enrichment for ribosome constituents and mRNA binding (Figure 10C) and ther APEX2-SRSF1 hits were predominantly involved in RNA binding (Figure 10D). This contrast is revealed very clearly in a bi-lobed STRING plot of protein associations for the split-APEX hits (Figure 11A) in comparison with a single network for APEX2-SRSF1 (Figure 11B). It is possible that the association of SRSF1 with the helicases, SRRM2 or TNPO3 occurs during ribosomal biogenesis as well as splicing.

FIGURE 10

Gene ontology analyses of the proteins common to all SRSF1-helicase split-APEX2 datasets and proteins in the full-length APEX2-SRSF1 dataset. The String database was used for analysis of biological processes (A,B) and molecular function (C,D). Panels A and C show the proteins common to all the SRSF1-helicase datasets, while B and D include all the proteins in the APEX2-SRSF1 dataset.

FIGURE 11

String protein networks. (A) Network for the proteins common to all the SRSF1-helicase split-APEX2 datasets. Edges indicate both functional and physical protein associations. The line thickness indicates the strength of data support. The proteins were clustered using MCL clustering and the edges between clusters are represented by dotted lines. (B) Network for the full-length APEX2-SRSF1 dataset.

Discussion

The intentions of these experiments were to establish whether all the splicing helicases are at any point sufficiently close to SRSF1 for the two portions of the split APEX2 enzyme to coalesce into a single functional enzyme and reconstitute peroxidase activity, thereby enabling information to be gained about the local environment when they interact directly. The numbers of proteins detected with each combination of SRSF1 and helicase are all quite similar, which suggests that SRSF1 associates as much in the cell with the other helicases as it does with DDX23 or TNPO3, interactions that have been confirmed previously (Maertens et al., 2014; Segovia et al., 2024). However, if the interactions took place at discrete points in the splicing pathway, then spliceosomal components would be disproportionately enriched compared with other nuclear proteins and, moreover, those components that are characteristic of the stage in splicing at which the helicase was associated would be enriched in the appropriate SRSF1/helicase experiment and not in the others. The U1 snRNP 70K protein, which would be expected to be present with DDX46 and DDX23, appears in the middle of the SRSF1/DDX23 list and elsewhere only as the lowest-ranked entry in the DHX38 list. Few of the unique hits had any links to splicing. The main exception was the SRSF1-DDX23 pair, which revealed two early stage proteins, U2AF2 and SF1, and SRSF9. Neither of the early stage proteins would be expected to be present when DDX23 enters with the tri-snRNP into association with complex A to form the pre-B complex (Charenton et al., 2019; Zhang Z. et al., 2024), since they would be displaced when complex A forms (Chen et al., 2017; Fleckner et al., 1997; Martinez-Lumbreras et al., 2024; Tholen et al., 2022), but there are other reports suggesting some continuing engagement in complex A (Agafonov et al., 2011). The other exception was with the SRSF1-DDX46 pair, which produced ARL6IP4. This protein, also known as SRp37, is an SR-like protein that has been located in nuclear speckles and nucleoli and has been shown to affect alternative splicing (Ouyang, 2009). Nothing is known of the mechanisms by which it affects splicing, but involvement at an early stage when DDX46 is present is possible. The role of this protein in splicing reactions would seem to be worth further investigation. However, we did not identify other examples of potential stage-specific spliceosomal proteins that are enriched in just one list, and the lists are dominated in the top dozen ranks by factors regulating splicing, which are generally present at higher concentrations than the spliceosomal factors (Hein et al., 2015).

These results raise questions as to the nature of the compartments, virtual or actual, in the cell in which SRSF1 interacts with helicases, SRRM2 and TNPO3. Since there is no substantial similarity in ranking to that seen with SRSF1 alone, factors such as the abundance of a protein or the presence of electrophilic amino acids do not seem to be the sole determinants of the more restricted outcomes seen with split-APEX. It will be useful to determine the location within the cell of the fusion proteins, although the absence of highly abundant cytoplasmic proteins favours the expected nuclear location. A potential limitation to these experiments is that the low concentrations of the EX fusions might limit the ability to detect all but the tightest interactions or interactions at those sites where the fusion protein is most concentrated, even if the interaction normally takes place and is functional but transient at other sites in the cell. A major drawback to experiments with APEX, split or entire, is the high mobility of the biotin-phenoxy radical. The labelling efficiency declines with distance and time from the source, but labelling is detected out to 20–270 nm from the source (Hung et al., 2016; Oakley et al., 2022). Improving the resolution of labelling might be achieved by less stable radicals, bulkier radicals that diffuse more slowly or the use of the expansion methods used in microscopy. Carbene-based radicals have already been shown to enable a higher resolution (Bartholow et al., 2024; Geri et al., 2020; Oakley et al., 2022).

A striking feature of our split-APEX results is the high proportion of labelled proteins that are involved in translation or ribosomal biogenesis. STRING plots show this very clearly: the majority of the split-APEX hits belong to either the splicing or translation networks, whereas the APEX2-SRSF1 hits include a much smaller proportion of proteins linked to translation and they are subsumed into the pattern of a single extensive network (Figure 11). It is unlikely that the helicases, SRRM2 and TNPO3 are recruited by SRSF1 to sites where they would not normally be located as a result of interactions between the AP and EX domains, since the pattern of proteins labelled is so different from that of SRSF1 alone. Instead, our results raise the possibility that these proteins, together with SRSF1, have roles in translation or ribosomal biogenesis. There is already evidence that DDX46, DDX23, DDX48, DHX8 and one of the abundant common hits, DDX5, have some involvement in ribosomal biogenesis (Martin et al., 2013; Tafforeau et al., 2013), and many splicing factors including SRSF1 have been found in the nucleolus (Andersen et al., 2005). The yeast orthologue of SRSF1, Npl3, has a role in exporting the large pre-ribosomal subunit (Hackmann et al., 2011). The binding of SRSF1 to RNA is in competition with the folding of the RNA into G-quadruplexes (Smith et al., 2014), and it has been shown recently that it promotes the unfolding of quadruplexes (De Silva et al., 2024). It is therefore not beyond the bounds of possibility that SRSF1 and the helicases cooperate in the remodelling of rRNA during ribosomal biogenesis to enable the formation of long-range secondary structures or to remove snoRNAs (Rodgers and Woodson, 2021). There is at present still some uncertainty regarding the number and roles of helicases involved in rRNA maturation (Mitterer and Pertschy, 2022).

An alternative possibility is that SRSF1 and the helicases might be involved in the activities of long non-coding (lnc) RNA transcribed by RNA polymerases I or II in the nucleolus and localized either in the nucleolus or the perinucleolar compartment (Dogra and Kriwacki, 2025; Feng and Manley, 2022). Of particular interest is the exemplar PNCTR, a perinucleolar lncRNA that regulates pre-mRNA splicing by sequestering polypyrimidine tract-binding protein, (PTBP1) (Yap et al., 2018) and was found by APEX2 labelling to be in close proximity to a number of pre-mRNA splicing factors (Yap et al., 2022). Significantly, one of these is SRSF1 (Yap et al., 2022). Thus, another possibility is that SRSF1 and the protein partners we tested might be involved in the organisation and modelling of nucleolar or perinucleolar RNA to control the level of binding of splicing factors by regulatory RNA. A prerequisite for further research would be to identify the sites within the nucleus at which SRSF1 and the tested proteins are colocalized and to test whether pre-rRNA processing, lncRNA abundance or the localization of splicing factors in the nucleolar regions are affected by knockdown or mutations that affect the interactions of SRSF1 with the helicases.

Materials and methods

Cloning

The human DDX46, DHX16, DDX48, DHX38 and DHX8 genes were bought from Insight Biotechnology UK (RC202320, RC202912, SC114843, RC200044, SC324113). The human TNPO3 gene was bought from Sino Biological (HG18667-U). The human SRRM2 gene was a kind gift from Wesley Sundquist & Katie Ullman (Addgene plasmid # 174089). The AP and EX fragments were kind gifts from Alice Ting (Addgene plasmid # 120912, plasmid #120913) (Han et al., 2019). The pEGFP-C1 vector was used as a backbone to generate constructs encoding for AP- and EX-fused DDX46, DDX23, DHX16, DDX48, DHX38, DHX8, TNPO3 and SRRM2 (Supplementary Figure 1). The cloning was performed using In-Fusion seamless cloning (Takara) or NEBuilder HiFi DNA Assembly (New England Biolabs) according to the manufacturers’ instructions. All constructs were verified using Nanopore DNA sequencing (Source Bioscience, UK).

Mammalian cell culture and transfections

HEK293T cells from ATCC (passages <20) were cultured in complete growth media consisting of 90% DMEM, GlutaMAX (Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle medium, Gibco) supplemented with 10% w/v FBS (Fetal Bovine Serum, Gibco) at 37 °C, under 5% CO2. Cells were transfected at 70%–80% confluence using jetPrime (Polyplus), with 10 μL jetPrime reagent, 500 μL jetPrime Buffer and 5 μg total DNA (AP-fusion: 2 μg, EX-fusion: 3 μg) per 9 × 106 cells for 4 h, after which transfection media was replaced with fresh growth media. The cells were tested negative for mycoplasma.

Biotin-phenol proximity labelling

HEK293T cells were transiently transfected with the plasmids encoding for the split APEX2 pairs. Labelling was done with the concentrations of biotin tyramide and hydrogen peroxide described in previous split-APEX experiments (Han et al., 2019). 24 h after the transfection, the growth media was changed with fresh growth media containing 500 μΜ Biotin tyramide, that was sonicated for at least 30 min. Cells were incubated at 37 °C, under 5% CO2 for 30 min, prior to labelling initiation with the addition of H2O2 (1 mM final concentration in PBS) and gentle agitation. The labelling reaction was quenched after 1 min with the removal of the growth media and the addition of Quenching solution (10 mM Sodium Ascorbate, 5 mM Trolox, 10 mM sodium azide in PBS). The cells were washed twice with the Quenching solution, before being harvested in Quenching solution by centrifugation at 1000 × g for 5 min.

Western blotting

A small proportion of a cell pellet from the biotin-phenol labelling was used for Western blotting. Cells were incubated at 90 °C, for 10 min, in the presence of 8 M Urea and then resolved on 4%–12% v/v SDS-polyacrylamide gels (NuPAGE Invitrogen). The gels were transferred to nitrocellulose membranes, stained with Ponceau S (0.1% w/v Ponceau S, 5% v/v acetic acid) and blocked at 4 °C, overnight with SuperBlock T20 (PBS) Blocking Buffer (Fisher Scientific). Blots aiming at the detection of biotinylated proteins were immersed at room temperature, for 1 h in IRDye 800CW Streptavidin (Li-Cor, 926–32230, 1:5000 dilution), rinsed three times with Blocking buffer 10 min each time and visualised using Odyssey Imager (Li-Cor). Blots aiming at the detection of the AP/EX-fused pairs were immersed at room temperature, for 1 h in rabbit anti-DDX46 (Insight Biotechnology, GTX115308, 1:1000 dilution)/rabbit anti-DDX23 (Insight Biotechnology, GTX115234, 1:1000 dilution)/rabbit anti-DHX16 (Insight Biotechnology, GTX115088, 1:1000 dilution)/rabbit anti-DDX48 (Sino Biological, 200,323-T36, 1:500 dilution)/rabbit anti-DHX38 (Proteintech, 10098-2-AP, 1:1000 dilution)/rabbit anti-DHX8 (Stratech Scientific, C14659-ABT, 1:500 dilution)/rabbit anti-TNPO3 (Bio-Techne, NBP3-15908, 1:1000 dilution)/mouse anti-SRSF1 (gift from A.R. Krainer, CSH laboratory, 1:1000 dilution). The blots were rinsed with Blocking buffer three times for 10 min each time, before being immersed at room temperature, for 1 h in IRDye 680RD Goat anti-rabbit IgG secondary antibody (Li-Cor, 926–68071, 1:1000 dilution) or IRDye 800CW Goat anti-mouse IgG secondary antibody (Li-Cor, 926–32210, 1:1000 dilution). Then, blots were rinsed with Blocking buffer three times for 10 min each time and visualised using Odyssey Imager (Li-Cor).

Sample preparation for mass spectroscopy

∼30 × 106 cells were used for each sample. Cells were lysed in lysis buffer comprised of 50 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.5, 0.5 M NaCl, 0.4% w/v SDS, 1 mM EDTA, 1 mM DTT, 2% v/v TritonX-100, Roche Complete Protease Inhibitor Cocktail mix using an ultrasonic disintegrator. The amount of protein content in each sample was assessed in triplicate using a nanodrop spectrophotometer and normalised amount to the sample with the lowest protein content was loaded on pre-washed High capacity Neutravidin resin (Thermo Fisher Scientific, #29204). The lysates were incubated with the resin at 4 °C, overnight with rotation. The resin was washed and pelleted by centrifugation at 1500 g, 4 °C, 5 min three times with each of the following buffers wash 1 (2% w/v SDS), wash 2 (50 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.5, 0.5 M NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 1% v/v TritonX-100, 0.1% w/v deoxycholate), wash 3 (10 mM Tris-HCl pH 8.0, 250 mM LiCl, 1 mM EDTA, 0.5% w/v deoxycholate) and wash 4 (50 mM Tris-HCl pH 8.0), wash 5 (100 mM Triethylammonium bicarbonate (TEAB)). Then, the samples were reduced and alkylated with the addition of buffer containing 100 mM TEAB, 40 mM Iodoacetamide (IAA), 10 mM DTT at 70 °C for 20 min (gentle agitation) prior to cooling down to 37 °C and overnight trypsinisation with 1 μg trypsin (Thermo Scientific) at 37 °C, overnight (gentle agitation). The next day the samples were acidified using Trifluoroacetic acid (TFA) (3<pH < 4). The Mass Spectroscopy initial analysis was performed at Warwick Scientific Services, University of Warwick.

RNA extraction - Reverse transcription–PCR

Total RNA was extracted using the Qiagen RNeasy Mini kit, with the addition of the on-column DNase treatment (Qiagen) to remove any residual DNA. PrimeScript RT master Mix was used for the cDNA synthesis (Takara). OneTaq 2x Master Mix was used for the PCR reactions (NEB). In all cases, the manufacturers’ protocols were followed. Bands from agarose gels were quantified using Fiji (Schindelin et al., 2012).

Gene ontology analysis

Gene Ontology (GO) analysis was performed using ShinyGO 0.80 (Ge et al., 2020) and the String database (Szklarczyk et al., 2023). KEGG pathway database was also used (Kanehisa et al., 2023; Kanehisa & Goto, 2000). Circos plots were generated with Circos software (Krzywinski et al., 2009) and Metascape (Zhou et al., 2019). Venn/Euler diagrams were generated using the Venn diagram tool from Gent University (https://bioinformatics.psb.ugent.be/webtools/Venn).

Statements

Data availability statement

The Scaffold files have been published on Figshare: https://doi.org/10.25392/leicester.data.30217723.

Ethics statement

Ethical approval was not required for the studies on humans in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements because only commercially available established cell lines were used.

Author contributions

VP: Methodology, Formal Analysis, Conceptualization, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Investigation, Writing – review and editing. MW: Writing – review and editing, Software, Formal Analysis. PD: Methodology, Validation, Writing – review and editing. CL: Resources, Writing – review and editing. ST: Writing – review and editing. SC: Writing – review and editing, Resources. HK: Writing – review and editing. CB-A: Writing – review and editing. MS-V: Writing – review and editing. AT-S: Writing – review and editing. ZZ: Writing – review and editing. AA: Writing – review and editing. CD: Funding acquisition, Writing – review and editing. AC: Funding acquisition, Writing – review and editing. GB: Writing – review and editing, Conceptualization, Funding acquisition. AH: Writing – review and editing, Conceptualization, Funding acquisition. IE: Supervision, Validation, Resources, Writing – review and editing, Conceptualization, Writing – original draft, Project administration, Funding acquisition, Visualization.

Funding

The authors declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. The research was supported by a Strategic Longer and Larger Grant: Frontier Bioscience from the Biotechnology and Biological Sciences Research Council, BBSRC (How do RNA-binding proteins control splice site selection? BB/T000627/1).

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge the advice received from Cleidiane Zampronio and Andrew Bottrill, WPH Proteomics Facility, University of Warwick.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

The author(s) declared that they were an editorial board member of Frontiers, at the time of submission. This had no impact on the peer review process and the final decision.

Generative AI statement

The authors declare that no Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fmolb.2025.1714378/full#supplementary-material

References

1

Agafonov D. E. Deckert J. Wolf E. Odenwalder P. Bessonov S. Will C. L. et al (2011). Semiquantitative proteomic analysis of the human spliceosome via a novel two-dimensional gel electrophoresis method. Mol. Cell. Biol.31, 2667–2682. 10.1128/MCB.05266-11

2

Akerman M. Fregoso O. I. Das S. Ruse C. Jensen M. A. Pappin D. J. et al (2015). Differential connectivity of splicing activators and repressors to the human spliceosome. Genome Biol.16, 119. 10.1186/s13059-015-0682-5

3

Anczukow O. Akerman M. Clery A. Wu J. Shen C. Shirole N. H. et al (2015). SRSF1-Regulated alternative splicing in breast cancer. Mol. Cell.60, 105–117. 10.1016/j.molcel.2015.09.005

4

Andersen J. S. Lam Y. W. Leung A. K. Ong S. E. Lyon C. E. Lamond A. I. et al (2005). Nucleolar proteome dynamics. Nature433, 77–83. 10.1038/nature03207

5

Arif W. Mathur B. Saikali M. F. Chembazhi U. V. Toohill K. Song Y. J. et al (2023). Splicing factor SRSF1 deficiency in the liver triggers NASH-Like pathology and cell death. Nat. Commun.14, 551. 10.1038/s41467-023-35932-3

6

Bartholow T. G. Burroughs P. W. W. Elledge S. K. Byrnes J. R. Kirkemo L. L. Garda V. et al (2024). Photoproximity labeling from single catalyst sites allows calibration and increased resolution for carbene labeling of protein partners in vitro and on cells. ACS Cent. Sci.10, 199–208. 10.1021/acscentsci.3c01473

7

Bertram K. Agafonov D. E. Liu W. T. Dybkov O. Will C. L. Hartmuth K. et al (2017). Cryo-EM structure of a human spliceosome activated for step 2 of splicing. Nature542, 318–323. 10.1038/nature21079

8

Boesler C. Rigo N. Anokhina M. M. Tauchert M. J. Agafonov D. E. Kastner B. et al (2016). A spliceosome intermediate with loosely associated tri-snRNP accumulates in the absence of Prp28 ATPase activity. Nat. Commun.7, 11997. 10.1038/ncomms11997

9

Chan C. C. Dostie J. Diem M. D. Feng W. Mann M. Rappsilber J. et al (2004). eIF4A3 is a novel component of the exon junction complex. RNA10, 200–209. 10.1261/rna.5230104

10

Charenton C. Wilkinson M. E. Nagai K. (2019). Mechanism of 5' splice site transfer for human spliceosome activation. Science364, 362–367. 10.1126/science.aax3289

11

Chen L. Weinmeister R. Kralovicova J. Eperon L. P. Vorechovsky I. Hudson A. J. et al (2017). Stoichiometries of U2AF35, U2AF65 and U2 snRNP reveal new early spliceosome assembly pathways. Nucleic Acids Res.45, 2051–2067. 10.1093/nar/gkw860

12

Clery A. Krepl M. Nguyen C. K. X. Moursy A. Jorjani H. Katsantoni M. et al (2021). Structure of SRSF1 RRM1 bound to RNA reveals an unexpected bimodal mode of interaction and explains its involvement in SMN1 exon7 splicing. Nat. Commun.12, 428. 10.1038/s41467-020-20481-w

13

Company M. Arenas J. Abelson J. (1991). Requirement of the RNA helicase-like protein PRP22 for release of messenger RNA from spliceosomes. Nature349, 487–493. 10.1038/349487a0

14

Das S. Krainer A. R. (2014). Emerging functions of SRSF1, splicing factor and oncoprotein, in RNA metabolism and cancer. Mol. Cancer Res.12, 1195–1204. 10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-14-0131

15

De Silva N. I. U. Lehman N. Fargason T. Paul T. Zhang Z. Zhang J. (2024). Unearthing a novel function of SRSF1 in binding and unfolding of RNA G-quadruplexes. Nucleic Acids Res.52, 4676–4690. 10.1093/nar/gkae213

16

Ding F. Su C. J. Edmonds K. K. Liang G. Elowitz M. B. (2022). Dynamics and functional roles of splicing factor autoregulation. Cell Rep.39, 110985. 10.1016/j.celrep.2022.110985

17

Dogra P. Kriwacki R. W. (2025). Phase separation via protein-protein and protein-RNA networks coordinates ribosome assembly in the nucleolus. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Gen. Subj.1869, 130835. 10.1016/j.bbagen.2025.130835

18

Dopie J. Sweredoski M. J. Moradian A. Belmont A. S. (2020). Tyramide signal amplification mass spectrometry (TSA-MS) ratio identifies nuclear speckle proteins. J. Cell Biol.21910, e201910207–jcb. 10.1083/jcb.201910207

19

Dorner K. Hondele M. (2024). The story of RNA unfolded: the molecular function of DEAD- and DExH-Box ATPases and their complex relationship with membraneless organelles. Annu. Rev. Biochem.93, 79–108. 10.1146/annurev-biochem-052521-121259

20

Enders M. Neumann P. Dickmanns A. Ficner R. (2023). Structure and function of spliceosomal DEAH-Box ATPases. Biol. Chem.404, 851–866. 10.1515/hsz-2023-0157

21

Eperon I. C. Ireland D. C. Smith R. A. Mayeda A. Krainer A. R. (1993). Pathways for selection of 5' splice sites by U1 snRNPs and SF2/ASF. EMBO J.12, 3607–3617. 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1993.tb06034.x

22

Eperon I. C. Makarova O. V. Mayeda A. Munroe S. H. Caceres J. F. Hayward D. G. et al (2000). Selection of alternative 5' splice sites: role of U1 snRNP and models for the antagonistic effects of SF2/ASF and hnRNP A1. Mol. Cell. Biol.20, 8303–8318. 10.1128/MCB.20.22.8303-8318.2000

23

Feng S. Manley J. L. (2022). Beyond rRNA: nucleolar transcription generates a complex network of RNAs with multiple roles in maintaining cellular homeostasis. Genes Dev.36, 876–886. 10.1101/gad.349969.122

24

Fica S. M. Oubridge C. Galej W. P. Wilkinson M. E. Bai X. C. Newman A. J. et al (2017). Structure of a spliceosome remodelled for exon ligation. Nature542, 377–380. 10.1038/nature21078

25

Fleckner J. Zhang M. Valcarcel J. Green M. R. (1997). U2AF65 recruits a novel human DEAD box protein required for the U2 snRNP-branchpoint interaction. Genes Dev.11, 1864–1872. 10.1101/gad.11.14.1864

26

Ge H. Manley J. L. (1990). A protein factor, ASF, controls cell-specific alternative splicing of SV40 early pre-mRNA in vitro. Cell62, 25–34. 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90236-8

27

Ge S. X. Jung D. Yao R. (2020). ShinyGO: a graphical gene-set enrichment tool for animals and plants. Bioinformatics36, 2628–2629. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btz931

28

Gehring N. H. Kunz J. B. Neu-Yilik G. Breit S. Viegas M. H. Hentze M. W. et al (2005). Exon-junction complex components specify distinct routes of nonsense-mediated mRNA decay with differential cofactor requirements. Mol. Cell.20, 65–75. 10.1016/j.molcel.2005.08.012

29

Geri J. B. Oakley J. V. Reyes-Robles T. Wang T. Mccarver S. J. White C. H. et al (2020). Microenvironment mapping via dexter energy transfer on immune cells. Science367, 1091–1097. 10.1126/science.aay4106

30

Hackmann A. Gross T. Baierlein C. Krebber H. (2011). The mRNA export factor Npl3 mediates the nuclear export of large ribosomal subunits. EMBO Rep.12, 1024–1031. 10.1038/embor.2011.155

31

Han Y. Branon T. C. Martell J. D. Boassa D. Shechner D. Ellisman M. H. et al (2019). Directed evolution of split APEX2 peroxidase. ACS Chem. Biol.14, 619–635. 10.1021/acschembio.8b00919

32

Havugimana P. C. Hart G. T. Nepusz T. Yang H. Turinsky A. L. Li Z. et al (2012). A census of human soluble protein complexes. Cell150, 1068–1081. 10.1016/j.cell.2012.08.011

33

Hein M. Y. Hubner N. C. Poser I. Cox J. Nagaraj N. Toyoda Y. et al (2015). A human interactome in three quantitative dimensions organized by stoichiometries and abundances. Cell163, 712–723. 10.1016/j.cell.2015.09.053

34

Hung V. Udeshi N. D. Lam S. S. Loh K. H. Cox K. J. Pedram K. et al (2016). Spatially resolved proteomic mapping in living cells with the engineered peroxidase APEX2. Nat. Protoc.11, 456–475. 10.1038/nprot.2016.018

35

Huttlin E. L. Bruckner R. J. Navarrete-Perea J. Cannon J. R. Baltier K. Gebreab F. et al (2021). Dual proteome-scale networks reveal cell-specific remodeling of the human interactome. Cell184, 3022–3040.e28. 10.1016/j.cell.2021.04.011

36

Ilik I. A. Malszycki M. Lubke A. K. Schade C. Meierhofer D. Aktas T. (2020). SON and SRRM2 are essential for nuclear speckle formation. Elife9, e60579. 10.7554/eLife.60579

37

Jamison S. F. Pasman Z. Wang J. Will C. Luhrmann R. Manley J. L. et al (1995). U1 snRNP-ASF/SF2 interaction and 5' splice site recognition: characterization of required elements. Nucleic Acids Res.23, 3260–3267. 10.1093/nar/23.16.3260

38

Ji X. Zhou Y. Pandit S. Huang J. Li H. Lin C. Y. et al (2013). SR proteins collaborate with 7SK and promoter-associated nascent RNA to release paused polymerase. Cell153, 855–868. 10.1016/j.cell.2013.04.028

39

Jobbins A. M. Reichenbach L. F. Lucas C. M. Hudson A. J. Burley G. A. Eperon I. C. (2018). The mechanisms of a Mammalian splicing enhancer. Nucleic Acids Res.46, 2145–2158. 10.1093/nar/gky056

40

Jobbins A. M. Campagne S. Weinmeister R. Lucas C. M. Gosliga A. R. Clery A. et al (2022). Exon-independent recruitment of SRSF1 is mediated by U1 snRNP stem-loop 3. EMBO J.41, e107640. 10.15252/embj.2021107640

41

Kanehisa M. Goto S. (2000). KEGG: kyoto encyclopedia of genes and genomes. Nucleic Acids Res.28, 27–30. 10.1093/nar/28.1.27

42

Kanehisa M. Furumichi M. Sato Y. Kawashima M. Ishiguro-Watanabe M. (2023). KEGG for taxonomy-based analysis of pathways and genomes. Nucleic Acids Res.51, D587–D592. 10.1093/nar/gkac963

43

Kim S. H. Lin R. J. (1996). Spliceosome activation by PRP2 ATPase prior to the first transesterification reaction of pre-mRNA splicing. Mol. Cell. Biol.16, 6810–6819. 10.1128/MCB.16.12.6810

44

King D. S. Beggs J. D. (1990). Interactions of PRP2 protein with pre-mRNA splicing complexes in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Nucleic Acids Res.18, 6559–6564. 10.1093/nar/18.22.6559

45

Kohtz J. D. Jamison S. F. Will C. L. Zuo P. Luhrmann R. Garcia-Blanco M. A. et al (1994). Protein-protein interactions and 5'-splice-site recognition in Mammalian mRNA precursors. Nature368, 119–124. 10.1038/368119a0

46

Krainer A. R. Conway G. C. Kozak D. (1990). Purification and characterization of pre-mRNA splicing factor SF2 from HeLa cells. Genes Dev.4, 1158–1171. 10.1101/gad.4.7.1158

47

Krishnan R. Blanco M. R. Kahlscheuer M. L. Abelson J. Guthrie C. Walter N. G. (2013). Biased brownian ratcheting leads to pre-mRNA remodeling and capture prior to first-step splicing. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol.20, 1450–1457. 10.1038/nsmb.2704

48

Krzywinski M. Schein J. Birol I. Connors J. Gascoyne R. Horsman D. et al (2009). Circos: an information aesthetic for comparative genomics. Genome Res.19, 1639–1645. 10.1101/gr.092759.109

49

Lareau L. F. Inada M. Green R. E. Wengrod J. C. Brenner S. E. (2007). Unproductive splicing of SR genes associated with highly conserved and ultraconserved DNA elements. Nature446, 926–929. 10.1038/nature05676

50

Lavigueur A. La Branche H. Kornblihtt A. R. Chabot B. (1993). A splicing enhancer in the human fibronectin alternate ED1 exon interacts with SR proteins and stimulates U2 snRNP binding. Genes Dev.7, 2405–2417. 10.1101/gad.7.12a.2405

51

Liu S. Li X. Zhang L. Jiang J. Hill R. C. Cui Y. et al (2017). Structure of the yeast spliceosomal postcatalytic P complex. Science358, 1278–1283. 10.1126/science.aar3462

52

Long J. C. Caceres J. F. (2009). The SR protein family of splicing factors: master regulators of gene expression. Biochem. J.417, 15–27. 10.1042/BJ20081501

53

Maertens G. N. Cook N. J. Wang W. Hare S. Gupta S. S. Oztop I. et al (2014). Structural basis for nuclear import of splicing factors by human transportin 3. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A.111, 2728–2733. 10.1073/pnas.1320755111

54

Martin R. Straub A. U. Doebele C. Bohnsack M. T. (2013). DExD/H-box RNA helicases in ribosome biogenesis. RNA Biol.10, 4–18. 10.4161/rna.21879

55

Martinez-Lumbreras S. Morguet C. Sattler M. (2024). Dynamic interactions drive early spliceosome assembly. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol.88, 102907. 10.1016/j.sbi.2024.102907

56

Maslon M. M. Heras S. R. Bellora N. Eyras E. Caceres J. F. (2014). The translational landscape of the splicing factor SRSF1 and its role in mitosis. Elife3, e02028. 10.7554/eLife.02028

57

Mcpheeters D. S. Muhlenkamp P. (2003). Spatial organization of protein-RNA interactions in the branch site-3' splice site region during pre-mRNA splicing in yeast. Mol. Cell. Biol.23, 4174–4186. 10.1128/MCB.23.12.4174-4186.2003

58

Mitterer V. Pertschy B. (2022). RNA folding and functions of RNA helicases in ribosome biogenesis. RNA Biol.19, 781–810. 10.1080/15476286.2022.2079890

59

Muller-Mcnicoll M. Botti V. De Jesus Domingues A. M. Brandl H. Schwich O. D. Steiner M. C. et al (2016). SR proteins are NXF1 adaptors that link alternative RNA processing to mRNA export. Genes Dev.30, 553–566. 10.1101/gad.276477.115

60

Niers J. M. Chen J. W. Weissleder R. Tannous B. A. (2011). Enhanced in vivo imaging of metabolically biotinylated cell surface reporters. Anal. Chem.83, 994–999. 10.1021/ac102758m

61

Oakley J. V. Buksh B. F. Fernandez D. F. Oblinsky D. G. Seath C. P. Geri J. B. et al (2022). Radius measurement via super-resolution microscopy enables the development of a variable radii proximity labeling platform. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A.119, e2203027119. 10.1073/pnas.2203027119

62

Old W. M. Meyer-Arendt K. Aveline-Wolf L. Pierce K. G. Mendoza A. Sevinsky J. R. et al (2005). Comparison of label-free methods for quantifying human proteins by shotgun proteomics. Mol. Cell Proteomics4, 1487–1502. 10.1074/mcp.M500084-MCP200

63

Ouyang P. (2009). SRrp37, a novel splicing regulator located in the nuclear speckles and nucleoli, interacts with SC35 and modulates alternative pre-mRNA splicing in vivo. J. Cell Biochem.108, 304–314. 10.1002/jcb.22255

64

Paul T. Zhang P. Zhang Z. Fargason T. De Silva N. I. U. Powell E. et al (2024). The U1-70K and SRSF1 interaction is modulated by phosphorylation during the early stages of spliceosome assembly. Protein Sci.33, e5117. 10.1002/pro.5117

65

Paz S. Krainer A. R. Caputi M. (2014). HIV-1 transcription is regulated by splicing factor SRSF1. Nucleic Acids Res.42, 13812–13823. 10.1093/nar/gku1170

66

Paz S. Ritchie A. Mauer C. Caputi M. (2021). The RNA binding protein SRSF1 is a master switch of gene expression and regulation in the immune system. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev.57, 19–26. 10.1016/j.cytogfr.2020.10.008

67

Perriman R. Barta I. Voeltz G. K. Abelson J. Ares M. Jr. (2003). ATP requirement for Prp5p function is determined by Cus2p and the structure of U2 small nuclear RNA. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A.100, 13857–13862. 10.1073/pnas.2036312100

68

Rodgers M. L. Woodson S. A. (2021). A roadmap for rRNA folding and assembly during transcription. Trends Biochem. Sci.46, 889–901. 10.1016/j.tibs.2021.05.009

69

Sanford J. R. Wang X. Mort M. Vanduyn N. Cooper D. N. Mooney S. D. et al (2009). Splicing factor SFRS1 recognizes a functionally diverse landscape of RNA transcripts. Genome Res.19, 381–394. 10.1101/gr.082503.108

70

Schindelin J. Arganda-Carreras I. Frise E. Kaynig V. Longair M. Pietzsch T. et al (2012). Fiji: an open-source platform for biological-image analysis. Nat. Methods9, 676–682. 10.1038/nmeth.2019

71

Schmidt C. Gronborg M. Deckert J. Bessonov S. Conrad T. Luhrmann R. et al (2014). Mass spectrometry-based relative quantification of proteins in precatalytic and catalytically active spliceosomes by metabolic labeling (SILAC), chemical labeling (iTRAQ), and label-free spectral count. RNA20, 406–420. 10.1261/rna.041244.113

72

Schmitzova J. Cretu C. Dienemann C. Urlaub H. Pena V. (2023). Structural basis of catalytic activation in human splicing. Nature617, 842–850. 10.1038/s41586-023-06049-w

73

Schwer B. (2008). A conformational rearrangement in the spliceosome sets the stage for Prp22-dependent mRNA release. Mol. Cell.30, 743–754. 10.1016/j.molcel.2008.05.003

74

Schwer B. Guthrie C. (1992). A conformational rearrangement in the spliceosome is dependent on PRP16 and ATP hydrolysis. EMBO J.11, 5033–5039. 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1992.tb05610.x

75

Segovia D. Adams D. W. Hoffman N. Safaric Tepes P. Wee T. L. Cifani P. et al (2024). SRSF1 interactome determined by proximity labeling reveals direct interaction with spliceosomal RNA helicase DDX23. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A.121, e2322974121. 10.1073/pnas.2322974121

76

Semlow D. R. Blanco M. R. Walter N. G. Staley J. P. (2016). Spliceosomal DEAH-Box ATPases remodel Pre-mRNA to activate alternative splice sites. Cell164, 985–998. 10.1016/j.cell.2016.01.025

77

Shen H. Green M. R. (2004). A pathway of sequential arginine-serine-rich domain-splicing signal interactions during mammalian spliceosome assembly. Mol. Cell.16, 363–373. 10.1016/j.molcel.2004.10.021

78

Shen H. Green M. R. (2007). RS domain-splicing signal interactions in splicing of U12-type and U2-type introns. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol.14, 597–603. 10.1038/nsmb1263

79

Sliskovic I. Eich H. Muller-Mcnicoll M. (2022). Exploring the multifunctionality of SR proteins. Biochem. Soc. Trans.50, 187–198. 10.1042/BST20210325

80

Smith L. D. Dickinson R. L. Lucas C. M. Cousins A. Malygin A. A. Weldon C. et al (2014). A targeted oligonucleotide enhancer of SMN2 exon 7 splicing forms competing quadruplex and protein complexes in functional conditions. Cell Rep.9, 193–205. 10.1016/j.celrep.2014.08.051

81

Staknis D. Reed R. (1994). SR proteins promote the first specific recognition of Pre-mRNA and are present together with the U1 small nuclear ribonucleoprotein particle in a general splicing enhancer complex. Mol. Cell. Biol.14, 7670–7682. 10.1128/mcb.14.11.7670-7682.1994

82

Staley J. P. Guthrie C. (1999). An RNA switch at the 5' splice site requires ATP and the DEAD box protein Prp28p. Mol. Cell.3, 55–64. 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80174-4

83

Sun Q. Hampson R. K. Rottman F. M. (1993). In vitro analysis of bovine growth hormone pre-mRNA alternative splicing. Involvement of exon sequences and trans-acting factor(s). J. Biol. Chem.268, 15659–15666. 10.1016/s0021-9258(18)82307-9

84

Sun S. Zhang Z. Sinha R. Karni R. Krainer A. R. (2010). SF2/ASF autoregulation involves multiple layers of post-transcriptional and translational control. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol.17, 306–312. 10.1038/nsmb.1750

85

Szklarczyk D. Kirsch R. Koutrouli M. Nastou K. Mehryary F. Hachilif R. et al (2023). The STRING database in 2023: protein-protein association networks and functional enrichment analyses for any sequenced genome of interest. Nucleic Acids Res.51, D638–D646. 10.1093/nar/gkac1000

86

Tacke R. Manley J. L. (1995). The human splicing factors ASF/SF2 and SC35 possess distinct, functionally significant RNA binding specificities. EMBO J.14, 3540–3551. 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1995.tb07360.x

87

Tafforeau L. Zorbas C. Langhendries J. L. Mullineux S. T. Stamatopoulou V. Mullier R. et al (2013). The complexity of human ribosome biogenesis revealed by systematic nucleolar screening of Pre-rRNA processing factors. Mol. Cell.51, 539–551. 10.1016/j.molcel.2013.08.011

88

Talkish J. Igel H. Hunter O. Horner S. W. Jeffery N. N. Leach J. R. et al (2019). Cus2 enforces the first ATP-dependent step of splicing by binding to yeast SF3b1 through a UHM-ULM interaction. RNA25, 1020–1037. 10.1261/rna.070649.119

89

Tarn W. Y. Steitz J. A. (1995). Modulation of 5' splice site choice in pre-messenger RNA by two distinct steps. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A.92, 2504–2508. 10.1073/pnas.92.7.2504

90

Tholen J. Razew M. Weis F. Galej W. P. (2022). Structural basis of branch site recognition by the human spliceosome. Science375, 50–57. 10.1126/science.abm4245

91

Townsend C. Leelaram M. N. Agafonov D. E. Dybkov O. Will C. L. Bertram K. et al (2020). Mechanism of protein-guided folding of the active site U2/U6 RNA during spliceosome activation. Sci. 37010.1126/science.abc3753370, eabc3753. 10.1126/science.abc3753

92

Trotman J. B. Porrello A. Schactler S. A. Deleon L. E. Eberhard Q. E. Boyson S. P. et al (2025). Xist Repeat A coordinates an assembly of SR proteins to recruit SPEN and induce gene silencing. BioRxiv Trotman928, 2025.05.21.655143. 10.1101/2025.05.21.655143

93

Wan R. Bai R. Shi Y. (2019). Molecular choreography of pre-mRNA splicing by the spliceosome. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol.59, 124–133. 10.1016/j.sbi.2019.07.010

94

Wang J. Manley J. L. (1995). Overexpression of the SR proteins ASF/SF2 and SC35 influences alternative splicing in vivo in diverse ways. RNA1, 335–346.

95

Wilkinson M. E. Charenton C. Nagai K. (2020). RNA splicing by the spliceosome. Annu. Rev. Biochem.89, 359–388. 10.1146/annurev-biochem-091719-064225

96

Wilkinson M. E. Fica S. M. Galej W. P. Nagai K. (2021). Structural basis for conformational equilibrium of the catalytic spliceosome. Mol. Cell.81, 1439–1452.e1439. 10.1016/j.molcel.2021.02.021

97

Wu J. Y. Maniatis T. (1993). Specific interactions between proteins implicated in splice site selection and regulated alternative splicing. Cell75, 1061–1070. 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90316-i

98

Xiao S. H. Manley J. L. (1998). Phosphorylation-dephosphorylation differentially affects activities of splicing factor ASF/SF2. EMBO J.17, 6359–6367. 10.1093/emboj/17.21.6359

99

Yang F. Bian T. Zhan X. Chen Z. Xing Z. Larsen N. A. et al (2023). Mechanisms of the RNA helicases DDX42 and DDX46 in human U2 snRNP assembly. Nat. Commun.14, 897. 10.1038/s41467-023-36489-x

100

Yap K. Mukhina S. Zhang G. Tan J. S. C. Ong H. S. Makeyev E. V. (2018). A short tandem repeat-enriched RNA assembles a nuclear compartment to control alternative splicing and promote cell survival. Mol. Cell.72, 525–540.e513. 10.1016/j.molcel.2018.08.041

101

Yap K. Chung T. H. Makeyev E. V. (2022). Hybridization-proximity labeling reveals spatially ordered interactions of nuclear RNA compartments. Mol. Cell.82, 463–478.e11. 10.1016/j.molcel.2021.10.009

102

Zhan X. Yan C. Zhang X. Lei J. Shi Y. (2018). Structure of a human catalytic step I spliceosome. Science359, 537–545. 10.1126/science.aar6401

103

Zhan X. Lu Y. Zhang X. Yan C. Shi Y. (2022). Mechanism of exon ligation by human spliceosome. Mol. Cell.82, 2769–2778.e4. 10.1016/j.molcel.2022.05.021

104

Zhan X. Lu Y. Shi Y. (2024). Molecular basis for the activation of human spliceosome. Nat. Commun.15, 6348. 10.1038/s41467-024-50785-0

105

Zhang Z. Will C. L. Bertram K. Dybkov O. Hartmuth K. Agafonov D. E. et al (2020). Molecular architecture of the human 17S U2 snRNP. Nature583, 310–313. 10.1038/s41586-020-2344-3

106

Zhang X. Zhan X. Bian T. Yang F. Li P. Lu Y. et al (2024a). Structural insights into branch site proofreading by human spliceosome. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol.31, 835–845. 10.1038/s41594-023-01188-0

107

Zhang Z. Kumar V. Dybkov O. Will C. L. Zhong J. Ludwig S. E. J. et al (2024b). Structural insights into the cross-exon to cross-intron spliceosome switch. Nature630, 1012–1019. 10.1038/s41586-024-07458-1

108

Zhou Y. Zhou B. Pache L. Chang M. Khodabakhshi A. H. Tanaseichuk O. et al (2019). Metascape provides a biologist-oriented resource for the analysis of systems-level datasets. Nat. Commun.10, 1523. 10.1038/s41467-019-09234-6

Summary

Keywords

RNA splicing helicases, split-APEX, SRSF1, ribosomal biogenesis, spliceosomal assembly

Citation

Paschalis V, Wills MFK, De Gusmao Araujo P, Lucas C, Tubasum S, Cui S, Kara H, Bueno-Alejo C, Santana-Vega M, Taladriz-Sender A, Zhao Z, Axer A, Dominguez C, Clark AW, Burley GA, Hudson AJ and Eperon IC (2025) Split-APEX implicates splicing factor SRSF1 and splicing helicases in ribosomal biogenesis. Front. Mol. Biosci. 12:1714378. doi: 10.3389/fmolb.2025.1714378

Received

27 September 2025

Revised

24 November 2025

Accepted

25 November 2025

Published

19 December 2025

Volume

12 - 2025

Edited by

Athar Ansari, Wayne State University, United States

Reviewed by

Cristian Prieto-Garcia, Goethe University Frankfurt, Germany

Zemin Yang, St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital, United States

Updates

Copyright

© 2025 Paschalis, Wills, De Gusmao Araujo, Lucas, Tubasum, Cui, Kara, Bueno-Alejo, Santana-Vega, Taladriz-Sender, Zhao, Axer, Dominguez, Clark, Burley, Hudson and Eperon.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Vasileios Paschalis, vasileios.paschalis@leicester.ac.uk; Ian C. Eperon, eci@leicester.ac.uk

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.