Abstract

Arterial hypertension is considered a main risk factor for cognitive impairment and stroke. Although chronic hypertension leads to adaptive changes in the lager cerebral blood vessels which should protect the downstream microvessels, profound changes in the structure and function of cerebral microcirculation were reported in this disease. The structural changes lead to dysregulation of the neurovascular unit and manifest themselves in particular as endothelial dysfunction, disruption of the blood-brain barrier and impairment of neurovascular coupling. The impairment of neurovascular coupling results in inadequate functional hyperemia, which in turn may lead to cognitive decline and dementia. In this review the effects of chronic arterial hypertension on the essential components of neurovascular unit involved in neurovascular coupling such as endothelial cells, astrocytes and pericytes are discussed.

1 Introduction

The brain is entirely dependent on the blood supply due to the high rate of oxygen and glucose metabolism and lack of the energy reserves. The human brain receives as much as 15% of the cardiac output, although it weighs only 2% of the body weight (Williams and Leggett, 1989). The mean cerebral blood flow does not change during local alterations of brain activity, but a redistribution of flow takes place to deliver more blood to metabolically activated areas thanks to the efficient local mechanisms of microflow regulation.

The local regulation of cerebral blood flow was first suggested in 1890 by Roy and Sherrington (1890). Performing the pioneering experiments in which they stimulated the sciatic nerve in dogs and measured changes of blood volume in the brain, they came to the conclusion that “the brain possesses an intrinsic mechanism by which its vascular supply can be varied locally in correspondence with local variations of functional activity.” About 90 years later, Larsen et al. (1978) and Lassen et al. (1978) published for the first time a functional mapping of the human brain, detecting activated brain regions by their increases in blood flow.

Extensive experimental studies on the morphological basis and on the mechanisms of this regulation have resulted in the introduction of two new concepts–the neurovascular unit and the neurovascular coupling (Iadecola, 2017; Nippert et al., 2018).

The neurovascular unit (NVU) is a structural and functional entity composed of neurons, astrocytes, and the microvascular endothelium, which together with perivascular astrocytic foot processes, pericytes and the extracellular matrix, form the blood-brain barrier (BBB).

In recent years, the participation of the luminal lining of the endothelial cells–the glycocalyx–in the BBB mechanisms is extensively discussed (Zhao et al., 2021).

The BBB is one of the primary mechanisms of the central nervous system (CNS) homeostasis. The maintenance of chemical composition of the extracellular fluid ensures the stabilization of resting potentials and the proper excitability of nerve cells. The presence of the blood-brain barrier also helps to maintain a constant volume of the extracellular space and thus the stable intracranial pressure. Keeping ions and proteins inside capillaries produces a gradient of osmotic pressure between the intra- and extravascular spaces, so that water that has been filtered through the wall of the capillary system is resorbed into the vascular system. This is essential for the pressure-volume balance of the brain, which does not have true lymphatic vessels and, together with the vascular system and cerebrospinal fluid, is surrounded by a rigid skull. However, the equivalent of the lymphatics, named a glymphatic system, has been described in the CNS (Iliff et al., 2012). This pathway will be discussed in more detail later in this review.

The structural components of the NVU are closely and reciprocally linked to each other to ensure an efficient system of microflow control (Abbott et al., 2006; Iadecola, 2017). In brief, the signals generated by activated neurons induce vasodilation of precapillary arterioles and increase microflow in a process named neurovascular coupling (NVC), which involves coordinated action of all elements of the NVU (Iadecola, 2017). The NVC is essential for the normal functioning of the brain. Impairment of neurovascular coupling is associated with cognitive decline and dementia as reported in neurodegenerative diseases and in hypertension (Iadecola and Gottesman, 2019; Meissner, 2016; Santisteban et al., 2023; Yu et al., 2020). According to Santisteban et al. (2023) long lasting high arterial blood pressure disturbs the structure and function of NVU, which in turn may result in the impairment of the NVC.

In this review, the effects of chronic arterial hypertension on the essential components of neurovascular unit involved in neurovascular coupling such as endothelial cells, astrocytes and pericytes are discussed.

The discussion of the impact of hypertension on the structure and function of the NVU is preceded by a brief description of the physiology of individual NVU components. Although the complex nature of the NVU in health has been extensively reviewed (Lochhead et al., 2020; McConnell and Mishra, 2022; Presa et al., 2020; Segarra et al., 2019), the present review is supplemented with recent data on the important role of the endothelial glycocalyx and the glymphatic system in NVU homeostasis.

This review is based on the findings from the experimental models of human arterial hypertension such as: (1) pharmacological models [Angiotensin II (ANG II)-, deoxycorticosterone acetate (DOCA)- salt-, high salt diet (HSD)-, and N-nitro-L-arginine methyl ester (L-NAME)-induced hypertension]; (2) genetic models of essential hypertension [spontaneously hypertensive rat (SHR); stroke-prone SHR; Dahl salt-sensitive rats]; and (3) surgically induced hypertension [the two-kidney one-clip model (i.e., constriction of only one renal artery), the two-kidney two-clip model (i.e., aortic constriction or constriction of both renal arteries), or the one-kidney one-clip model (i.e., constriction of one renal artery and ablation of the contralateral kidney)].

It should be mentioned that in recent years, thanks to modern genomics and omics technologies offering cell-specific molecular insights (such as e.g., single-cell RNA sequencing), considerable heterogeneity of the cerebrovascular network was demonstrated depending on the brain region or the position within the vascular tree.

For the readers interested in the issue of segmental heterogeneity and in the evolving concept of neurovascular complex, we recommend recent reviews by Schaeffer and Iadecola (2021), Matsuoka et al. (2022) and Iadecola et al. (2023).

2 Physiology of the NVU

2.1 Cerebral microvascular endothelium and glycocalyx

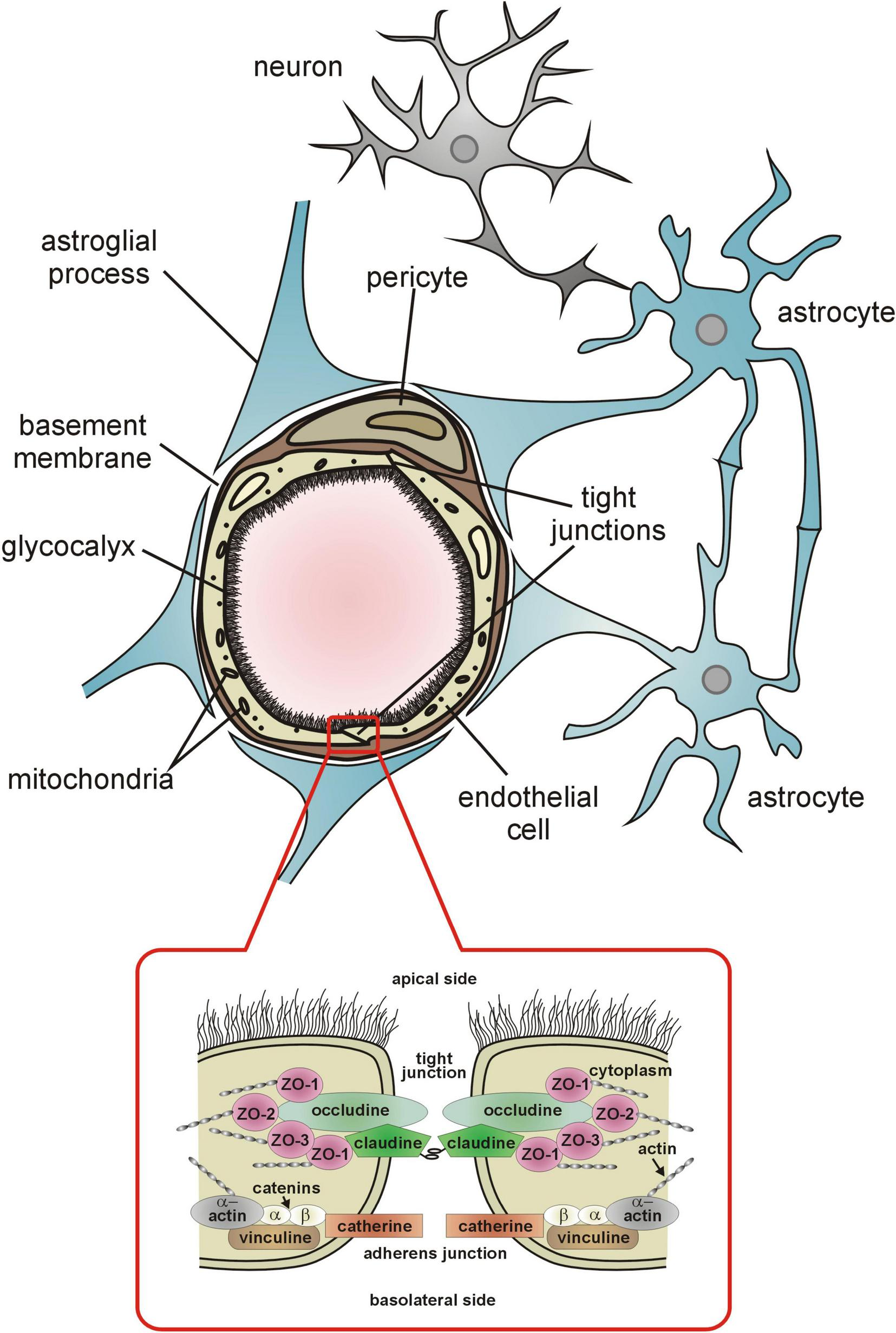

The endothelial cells (ECs) of capillaries form the structural basis of the BBB. They are connected by tight and adherens junctions (Figure 1) that restrict paracellular transport to the brain of unwanted and unnecessary blood born molecules and ions (Abbott et al., 2006; Daneman and Prat, 2015). The tightness of tight junctions (TJs) in the BBB is evidenced by their high electrical resistance which approximates 2,000 Ω cm–2. In other organs with continuous capillary wall (e.g., skeletal muscles) the resistance of the intercellular junctions does not exceed 30 Ω cm–2 (Butt et al., 1990). In addition, endothelial cells of cerebral capillaries under normal conditions have very few cytoplasmic vesicles that limits transcytosis (Langen et al., 2019). Delivery of essential, not freely diffusing nutrients is based on specialized transport systems (Abbott et al., 2006; Daneman and Prat, 2015; Langen et al., 2019).

FIGURE 1

The components of the blood-brain barrier. Detailed description is provided in the text.

The luminal surface of the cerebral capillary endothelium is lined with a hundreds of nanometer thick glycocalyx (eGC) synthesized by the endothelial cells (Zhao et al., 2021; Figure 1). It is composed mainly of transmembrane and membrane-bound proteoglycans, glycosaminoglycans, and glycoproteins, predominantly hyaluronan, syndecan-1, and heparan sulfate (Reitsma et al., 2007). The eGC is best known as a sensor and transducer of shear stress forces exerted on the endothelium by circulating blood and intravascular pressure (Weinbaum et al., 2003; Tarbell and Pahakis, 2006; Curry and Adamson, 2012) and plays a key role in shear stress activation of the endothelial production of NO and prostacyclin (Resnick and Gimbrone, 1995; Chien et al., 1998; Andrews et al., 2014; Williams and Flood, 2015). Both compounds are vasodilators and anticoagulants. Endothelial NO is essential for the maintaining resting cerebral blood flow and microvascular resistance, whereas prostacyclin ensures patency of microvessels by inhibiting intravascular coagulation (Gryglewski et al., 1997; Iadecola et al., 1994; Kozniewska et al., 1992).

Recent data indicates that glycocalyx is essential also for the maintenance of the barrier properties of the capillary endothelium (Kutuzov et al., 2018; Stoddart et al., 2022; Zhao et al., 2021; Zhu et al., 2018). It has been demonstrated that enzymatic degradation of the eGC under physiological conditions led to increased vesicular activity in the endothelium, transcytosis, and subsequent BBB leakage (Zhu et al., 2018). It has been also shown with two-photon microscopy imaging of single cortical capillaries in anesthetized mice that glycocalyx forms a barrier to large but not to small molecules (Kutuzov et al., 2018).

It is worth mentioning that luminal portion of eGC is negatively charged and is responsible for repelling from the vessel wall the negatively charged albumins and inflammatory leukocytes (Foote et al., 2022). Thus, under physiological conditions the eGC stabilizes BBB, prevents leakage of plasma components and adhesion of leukocytes to the endothelium, inhibits platelet activation and intravascular coagulation.

The abluminal side of the cerebral vessels endothelium is surrounded by a basement membrane shared with the adjacent pericytes (Figure 1). Capillary pericytes and ECs are in almost 98% covered by astrocytic foot processes (end-feet).

The interaction between the cells constituting the NVU is essential for the formation and maintenance of the BBB as well as for the adequate blood supply of the neurons.

To maintain selective BBB permeability, the endothelium regulates the exchange of fluids and solutes, including plasma proteins by paracellular and transcellular transport. The paracellular transport is characterized by passive diffusion for solutes, leading to relatively unregulated movement of substances compared to the more tightly controlled transcellular pathway (Abbott et al., 2006; Komarova and Malik, 2010). The paracellular transport is limited by the above-mentioned tight junctions and adherens junctions, which connect adjacent endothelial cells into the monolayer to limit the transport of plasma proteins from the vessel lumen to stroma (Komarova and Malik, 2010; Figure 1).

The TJs are composed of three integral membrane proteins: claudins, occludin, and the adhesion proteins (Figure 1). Claudins are considered to establish the backbone of TJs (Günzel and Yu, 2013). The claudin molecules of adjacent cells are linked by adhesion proteins. Both claudins and occludin appear to regulate the tightness of TJs, depending on the level of phosphorylation (Hirase et al., 1997; Yamamoto et al., 2008; Ma et al., 2017). Some experimental data indicate that claudin-5, the major claudin of the BBB, is able to induce barrier function in rat brain endothelial cells (Ohtsuki et al., 2007) whereas claudin-5 deficiency is associated with increased BBB permeability (Nitta et al., 2003). On the other hand, phosphorylation of occludin has been reported to stabilize tight junction, its electrical resistance and permeability (Farshori and Kachar, 1999; Tsukamoto and Nigam, 1999; Wachtel et al., 1999). The intracellular proteins zonula occludens: ZO-1, ZO-2 and ZO-3 link claudins and occludin with actin of the cytoskeleton. In vitro studies have shown that zonula occludens, particularly ZO-1, similarly to occludin, is a tight junction regulatory protein (Huber et al., 2001). The most important intracellular signals influencing tight junction formation and permeability include protein kinase C, adenylate cyclase, and calcium ions (Gloor et al., 2001). The adherens junction, composed of vascular endothelial (VE) cadherin, also contacts cytoskeletal actin by means of the corresponding catenin subunit, and seems necessary for the formation and stabilization of tight junction (Huber et al., 2001). In vitro studies have shown that modification of the cadherin molecule leads to a reduction in the tightness of TJs (Navarro et al., 1995; Mitic and Anderson, 1998). The barrier function of TJs also significantly depends on the spatial structure of actin. The numerous experimental studies have shown that reorganization of this cytoskeleton protein leads to the destabilization and reduction of tightness of TJs (Huber et al., 2001; Kniesel and Wolburg, 2000). The reorganization of cytoskeletal actin may be one of the causes of increased TJs permeability in hypertension (Nag, 1995).

The second type of endothelial transport, named transcellular pathway or transcytosis, is responsible for the transport of macromolecules across the endothelial barrier (Bourdet et al., 2006). Transcytosis is typically energy-dependent and allows for the selective transport of larger or charged molecules that cannot diffuse freely through tight junctions. It also maintains transendothelial oncotic pressure (Komarova and Malik, 2010). Transcytosis involves the fission of caveolin-1 (Cav-1)-enriched plasma membrane macrodomains, from the endothelial cell’s luminal surface, and then the movement of caveolar vesicles to the basal surface. The vesicles release macromolecules through exocytosis after fusing with the abluminal side’s plasma membrane (Minshall et al., 2002). Currently it is postulated that endothelial transcytosis can be divided into: non-selective adsorptive transcytosis, in which charged interactions between the molecules and the plasma membrane facilitate cargo entry, and receptor-mediated transcytosis (RMT), in which ligand–receptor binding initiates endocytosis (Yang et al., 2025). Recently, RMT is believed to be a potential route for delivering drugs with high molecular weights to the brain (Baghirov, 2025; Zhang et al., 2025). In physiological conditions, endothelial cells usually exhibit a low level of transcytosis (Ayloo and Gu, 2019). Its increased activity is rather associated with pathological conditions (Knowland et al., 2014; Yang et al., 2020). Despite that, both transcytosis and paracellular transport play an important role in maintaining tissue fluid homeostasis, however they act through different mechanisms, contribute differently to physiological processes and responses to pathological conditions.

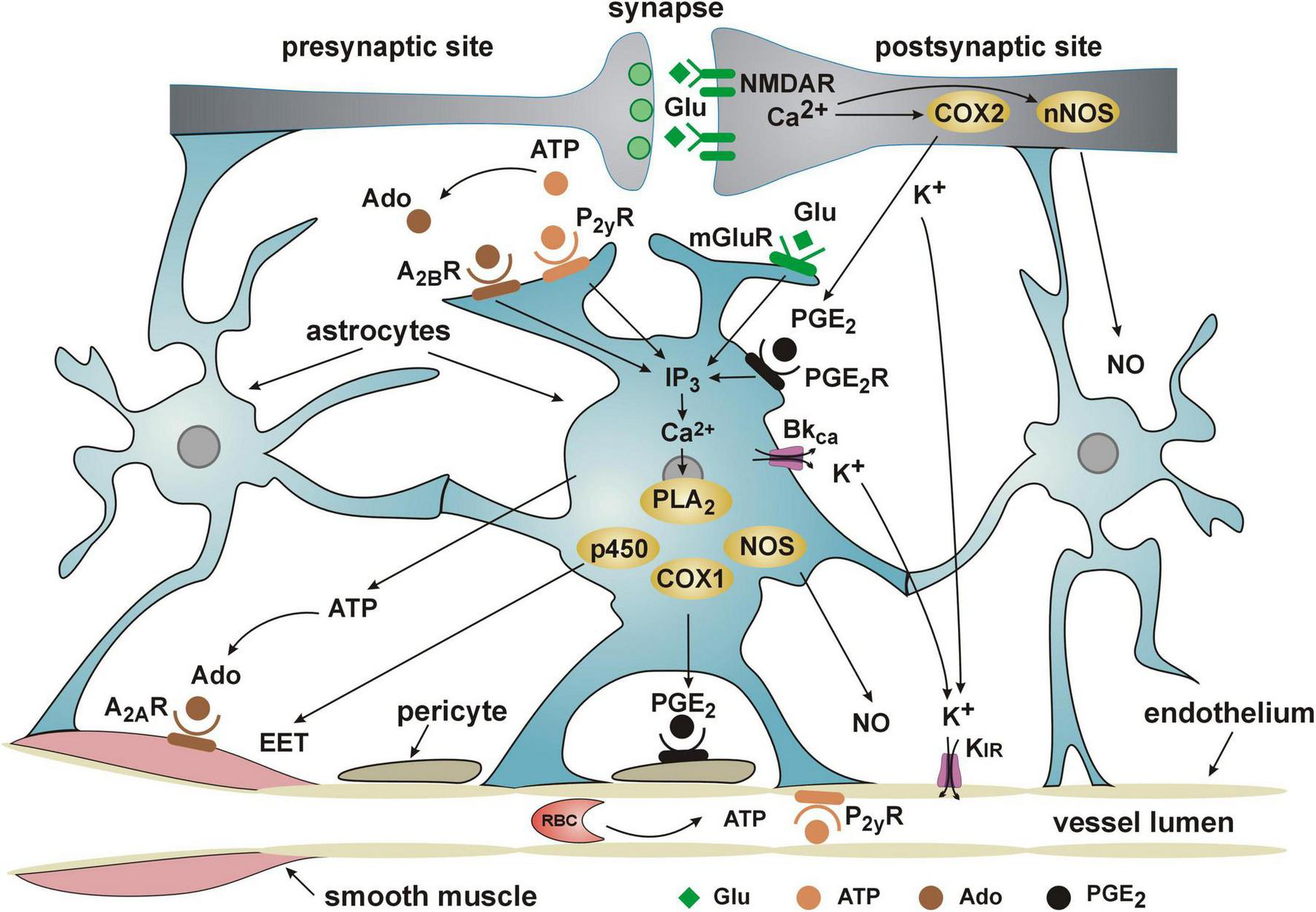

Although sealing in the BBB is considered to be the most important function of the cerebral microvascular endothelium, the current knowledge points out the role of the endothelium in the initiation and propagation of the signals underlying NVC and functional hyperemia (Chen et al., 2014; Mishra et al., 2016; Iadecola, 2017; Longden et al., 2017; Rungta et al., 2018; Santisteban et al., 2023). According to a current point of view, increased extracellular concentration of K+, associated with neural firing (Figure 2), activates inward-rectifier potassium channels Kir2.1 in capillary endothelial cells which leads to endothelial hyperpolarization. The hyperpolarizing current back-propagates along endothelial cells and spreads to vascular smooth muscle cells in precapillary arterioles through the myo-endothelial junctions to cause dilation of upstream penetrating arterioles and pial arteries, thereby inducing an increase in blood flow to the site of signal initiation (Longden et al., 2017; Rungta et al., 2018).

FIGURE 2

Current view of the cooperation of NVU elements in functional hyperemia/neurovascular coupling. Detailed description of the role of the endothelium in NVC is provided in the text. ADO, adenosine diphosphate; ATP, adenosine triphosphate; A2AR and A2BR, adenosine receptors; COX1 and COX2, cyclooxygenases 1 and 2; p450, cytochrome P450; EET, epoxyeicosatrienoic acid; IP3, inositol trisphosphate; PGE2, prostaglandin E2; PGE2R, prostaglandin E2 receptor; KIR, inward rectifier potassium channels; BKCa, channel, large conductance calcium-activated potassium channel; Glu, glutamate; mGluR, metabotropic glutamate receptor; NMDAR, N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor; NO, nitric oxide; NOS, nitric oxide synthase; nNOS, neuronal nitric oxide synthase; P2YR, purinoceptor; PLA2, phospholipase A2; PLD2, phospholipase D2.

2.2 The role of astrocytes

The astrocytes spreading between the neurons and capillary wall (Figures 1, 2), cover with their extensive foot processes (end-feet) about 98% of the abluminal surface of the endothelium. They are essential for the formation and maintenance of the BBB as discussed by Abbott et al. (2006).

Astrocytes are also important mediators of functional hyperemia (Figure 2). For a long time they were considered as a main source of the signals responsible for NVC (for review see Lia et al., 2023). It has been established that during the release of glutamate from the firing neurons, astrocytic glutamate receptors, both metabotropic and NMDA, are stimulated what results in the increase of intracellular Ca2+ concentration. The astrocytic Ca2+ concentration increases also due to the stimulation of purinergic (P2yR, A2BR) and prostaglandin E2 (PGE2R) receptors. Activation of calcium-dependent metabolic pathways in astrocytes results in the release of vasodilators such as epoxyeicosatrienoic acid (EET), prostaglandin PGE2 and nitric oxide (NO). EET inhibits vascular smooth muscle tone directly whereas PGE2 seems to diminish capillary resistance indirectly by hyperpolarizing the pericytes (Lia et al., 2023). The main action of astrocytic NO is it to inhibit production by astrocytes of 20-hydroxyeicosatetraenoic acid (20-HETE), a product of omega-hydroxylation of arachidonic acid, and a strong vasoconstrictor (Hoopes et al., 2015).

Astrocytes also participate in the exchange of cerebrospinal (CSF) and interstitial fluid (ICF), of the brain parenchyma which helps to eliminate metabolic waste products from the central nervous system. This clearance mechanism, known as glymphatic system, is mediated by a water channel aquaporin-4 (AQP4) located at the astrocytic end-feet processes close to the capillary wall (Iliff et al., 2012). According to the glymphatic theory, the CSF flows along the periarterial space, passes through AQP4 channel and enters the parenchyma where it mixes with ISF, and leaves the brain along perivenous space. This way, waste products included in ISF are cleared out of the brain. It has been demonstrated that lack of AQP4 at the gliovascular interface impairs clearance and transport via the glymphatic system (Iliff et al., 2012).

2.3 The pericyte

Pericytes are pluripotent, perivascular mural cells found in precapillary arterioles, capillaries and postcapillary venules. The density of pericytes covering brain capillary wall varies between 30 and 99% of the abluminal surface (Dalkara et al., 2011; Hartmann et al., 2015). They are embedded in the basement membrane of the endothelial cells (Sims, 1991; Mathiisen et al., 2010). Although the ratio of pericytes to endothelial cells in cerebral capillaries is 1:3, the pericytes send out the extensive projections along the capillaries (Sá-Pereira et al., 2012). The processes of adjacent pericytes do not overlap, although they end in close proximity. Such a morphology allows for a better contact of pericytes with endothelial cells and astrocytic end-feet. Pericytes are characterized by significant plasticity. Interestingly, it has been demonstrated that elimination of a single pericyte in a mouse cerebral cortex results in the mobilization of the neighboring pericytes to send their projections to the uncovered endothelium (Berthiaume et al., 2018).

Pericytes were reported to control protein expression of the tight junctions (Armulik et al., 2010; Bell et al., 2010; Daneman et al., 2010). Pericyte ablation has been shown to breakdown of the BBB in experimental conditions (Nikolakopoulou et al., 2019).

Pericytes also play a key role in the formation and stabilization of new blood vessels (Durham et al., 2014; Blocki et al., 2018).

Being located between astrocytic end-feet and endothelial cells (Figure 1), pericytes are in excellent position to regulate the resistance to flow through capillaries, particularly as they express the contractile protein alpha-smooth muscle actin (Nehls and Drenckhahn, 1991; Bandopadhyay et al., 2001; Alarcon-Martinez et al., 2018) and receptors for vasoactive compounds such as ATP, noradrenaline, thromboxane A2, acetylcholine, PGE2 (Fernández-Klett et al., 2010; Peppiatt et al., 2006; Hamilton et al., 2010). Accordingly, numerous studies have shown that pericytes regulate capillary diameter and are important players in NVC (Peppiatt et al., 2006; Yemisci et al., 2009; Hamilton et al., 2010; Hall et al., 2014; Khennouf et al., 2018). As demonstrated by Khennouf et al. (2018) capillaries dilate during activation of the barrel cortex in mice (whisker stimulation) due to the decrease of calcium signal in the pericytes. According to Hall et al. (2014) during functional hyperemia, pericytes may dilate capillaries via a prostaglandin E2-dependent pathway as presented in Figure 2.

Some experimental studies reported that ablation or degeneration of pericytes leads to neurovascular uncoupling, reduced oxygen supply to the brain and metabolic stress. Neurovascular deficits lead over time to impaired neuronal excitability and neurodegenerative changes (Kisler et al., 2017, 2020).

3 Neurovascular coupling

The increase in microflow adequate to support neuronal activity requires, as mentioned, the close cooperation of all elements of the NVU (Figure 2). The trigger of the flow response is the release of the excitatory neurotransmitter glutamate and stimulation of NMDA and metabotropic glutamate receptors on neurons and astrocytes. The resulting increase in the intracellular Ca2+ concentration leads to the release of vasodilators such as PGE2, NO and EET. An essential role in NVC is played by K+ ions, released during depolarization of neurons and from astrocytic end-feet due to the opening of BKCa potassium channels. Increasing the extracellular K+ concentration activates Kir channels in the endothelial cells, leading to their hyperpolarization. This in turn is transmitted in a retrograde fashion as wave of hyperpolarization to the level of arterioles to dilate them and ensure the increase in blood supply of the activated neurons.

In conclusion, all components of the NVU are essential for the maintenance of the blood-brain barrier and a close cooperation between them is required to ensure proper NVC.

4 Effects of arterial hypertension on the components of the neurovascular unit

The arterial hypertension has profound effects on the structure and function of all components of the NVU, resulting in an impaired communication between neurons and microvessels (Calcinaghi et al., 2013; Capone et al., 2012; Girouard et al., 2007; Kazama et al., 2003), neurons and astrocytes (Tagami et al., 1991), and astrocytes and microvessels (Diaz et al., 2019; Marins et al., 2017). The diseased communication, in turn, leads to the impairment of NVC and inadequate functional hyperemia, resulting in a cognitive decline and hypertension-associated dementia (Dahlöf, 2007; Iadecola and Gottesman, 2019). An additional cause of functional impairment associated with hypertension may be the rarefaction of cerebral capillaries, reported in the different animal models of hypertension (Kozniewska et al., 1982; Suzuki et al., 2003; Tarantini et al., 2016) and in the retina of patients with untreated mild hypertension (Bosch et al., 2017). In the context of cognitive deficits, a decreased density of capillaries in the cerebral cortex, as observed in the study by Kozniewska et al. (1982), was associated with a decrease in cerebral microflow.

4.1 Impact on the endothelial cells, glycocalyx, and the BBB

Accumulating evidence indicates that the BBB is a dynamic structure which is dysregulated in cardiovascular diseases including hypertension (Lochhead et al., 2020). Hypertension leads to increased endothelial permeability and BBB disruption, which has been shown in several experimental models of hypertension, including: SHR (Tagami et al., 1991; Ueno et al., 2004), Dahl-salt sensitive rats (Pelisch et al., 2011; Maeda et al., 2021), the two-kidney two-clip model of hypertension (Mohammadi and Dehghani, 2014), and angiotensin II-induced hypertension (Vital et al., 2010; Santisteban et al., 2020). Hypertension-induced changes in the BBB comprise unsealing of the TJs, damage of the glycocalyx and endothelial dysfunction. The effect of hypertension on paracellular transport appears complex. Some studies demonstrated dysfunction of paracellular transport (Pelisch et al., 2011, 2013; Biancardi et al., 2014; Mohammadi and Dehghani, 2014), while other indicated mainly a transcellular transport as the determinant of increased capillary leakage (Fragas et al., 2021; Candido et al., 2023). For example Santisteban et al. (2020) showed that sustained elevations in blood pressure caused by ANG II induce morphological and molecular remodeling of TJs. ANG II-dependent decreased expression of mRNA for TJs proteins was observed in Dahl salt-sensitive rats fed a high-salt diet (Pelisch et al., 2011). On the other hand, Fleegal-DeMotta et al. (2009) demonstrated that ANG II did not affect the expression of markers of endothelial tight junctions, including occludin and claudin-5. In contrast, expression of claudin-5 was reduced in stroke-prone SHR (Bailey et al., 2011) and the two-kidney, two-clip model of hypertension (Mohammadi and Dehghani, 2014), however, the role of ANG II was not investigated in these studies. Unlike TJs, there are few experimental studies on the effect of hypertension on VE-cadherin. Recent clinical research showed decreased plasma VE-cadherin levels in hypertensive patients (Tjili et al., 2025). Some data indicate that not paracellular transport but transcytosis is the primary mechanism underlying increased BBB permeability in hypertension, at least in brain areas related to the autonomic system (Fragas et al., 2021; Candido et al., 2023). Fragas et al. (2021), analyzing changes in caveolin-1 expression within hypothalamus of the SHRs, showed increased transcytosis and a positive effect of exercise training on normalization of this type of endothelial transport (Fragas et al., 2021). The recent studies showed an increase in transcellular transport and a reduction in claudin-5 expression in the two-kidney, one-clip model of hypertension (Perego et al., 2025). These latest research suggests that both types of endothelial transport may coexist and may be affected concomitantly in hypertension.

In addition to the negative impact of hypertension on endothelial transport, unfavorable changes in the glycocalyx are also observed. The degradation of the microvascular glycocalyx was demonstrated in stroke-resistant and stroke-prone SHR (Ueno et al., 2004) and in ANG II-induced hypertension (Nag, 1984), what inevitably led to dysfunction of the endothelium. In consequence, glycocalyx degradation may lead to leakage of the blood–brain barrier and the formation of brain edema (Zhu et al., 2018).

The endothelial glycocalyx breakdown is followed by up-regulation of endothelial adhesion molecules, such as endothelial selectin (E-selectin), platelet selectin (P-selectin), vascular cell adhesion molecule (VCAM-1), and intercellular adhesion molecules (ICAM-1) (Rabelink et al., 2010). The vast majority of studies regarding the effect of hypertension on the expression of adhesion molecules have been conducted on peripheral vessels. These studies have demonstrated increased expression of adhesion molecules in stroke-prone SHRs (Liu et al., 1996), two-kidney one-clip hypertensive rats (Mai et al., 1996), and in angiotensin II-induced hypertension (Tummala et al., 1999). Furthermore, clinical trials revealed that patients with moderate hypertension had considerably greater circulating levels of both ICAM-1 and VCAM-1 than their normotensive peers of similar age, body composition, and metabolic profile (Desouza et al., 1997). Another clinical investigation demonstrated significant increases in E-selectin, P-selectin, and ICAM-1, as well as a trend toward increased levels of VCAM-1, in hypertension patients compared to controls (Shalia et al., 2009). Notably, there was an increase in the expression of adhesion molecules in cerebral blood vessels (Suzuki et al., 2001). An increased level of adhesion molecules is critical in the progression of thrombosis and stroke (Blankenberg et al., 2003). This is one of the causes that hypertension is regarded as a major risk factor for stroke development (Johansson, 1999; Przykaza, 2021).

Some experimental studies demonstrated that increased endothelial permeability is associated with increased brain ANG II level rather than with blood pressure changes (Pelisch et al., 2011; Faraco et al., 2016). The AT1 receptors on endothelial cells are essential for initiating the increase in BBB permeability. However, experimental studies have shown that the AT1 receptors in perivascular macrophages (PVM), innate immune cells closely associated with cerebral arterioles, were major contributors to the neurovascular dysfunction (Santisteban et al., 2020). In hypertension, ANG II can enter the perivascular space and activate AT1 receptors in PVMs, leading to the production of ROS through the superoxide-producing enzyme NOX2 (Faraco et al., 2016). The downstream mechanisms by which ANG II-induced oxidative stress alters cerebrovascular function involve nitrosative stress and NO depletion (Girouard et al., 2007; De Silva and Faraci, 2013). ANG II-derived superoxide anion reacts with NO to form a powerful oxidant, peroxynitrite, which, in turn, mediates damage to the endothelium (Beckman et al., 1990). Impaired response of microvessels to endothelium-dependent acetylcholine was observed not only in ANG II-induced hypertension (Girouard et al., 2007) but also in DOCA-salt–induced hypertension (Matin et al., 2016) and in SHR (Freitas et al., 2017).

BBB dysfunction facilitates the infiltration of plasma components into the brain and the production of pro-inflammatory signals that lead to the activation of microglia and astrocytes (Presa et al., 2020). Circulating inflammatory molecules, such as tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α), C-reactive protein, interleukin IL-6, and IL-1β, are upregulated in the brain both in hypertensive patients and in hypertensive animal models (Coffman, 2011; Winklewski et al., 2015). Inflammatory factors, in turn, impair endothelial function, resulting in a further reduction in the functionality of the microvasculature (Meissner, 2016). It is known that ANG II–induced hypertension attenuates the increase in neocortex CBF produced by whisker stimulation (Kazama et al., 2003; Girouard et al., 2007). Further studies revealed that impaired neurovascular coupling in ANG II–induced hypertension is associated with ROS production in the subfornical organ (SFO), one of the forebrain circumventricular organs responsible for hormonal release and sympathetic activation that drive the elevation in arterial pressure (Capone et al., 2012). The effect of ANG II on neurovascular coupling was blocked by losartan, the antagonist of AT1 receptors (Kazama et al., 2003). In addition, no impairment of neurovascular coupling was found in mice administered phenylephrine to induce a similar degree of hypertension (Kazama et al., 2003; Capone et al., 2012), suggesting that ANG II, rather than the elevation in systemic pressure per se, caused the neurovascular dysfunction. On the other hand, neurovascular coupling to whisker stimulation is also impaired in SHR (Calcinaghi et al., 2013), and losartan treatment did not improve functional hyperemia, indicating that the effects of blood pressure elevation on arterial structure, such as the response of microvessels to acetylcholine, cannot be ignored.

In hypertension, the change of endothelial cell phenotype is observed. Instead of promoting vasodilation and anticoagulation, the endothelial cells in hypertension are pro-contractile, pro-inflammatory, and pro-oxidative. As a result of this unfavorable change, cerebral blood microvessels are unable to respond with vasodilation to increased neuronal activity, pointing to the impairment of NVC (Kazama et al., 2003; Girouard et al., 2007; Capone et al., 2012; Calcinaghi et al., 2013). Since the normal endothelium exerts trophic effects on brain cells and contributes to maintaining the health of neurons, glia, and oligodendrocytes (Iadecola and Gottesman, 2019), the dysfunction of endothelial cells in hypertension may affect all components of NVU.

4.2 Impact on astrocytes

Although astrocytes establish a functional bridge between brain perfusion and neuronal activity due to their close contact with blood vessels and synapses, there is still a limited understanding of the changes in their structure and function in hypertension. The increasing amount of recent research sheds new light on this issue (Xia et al., 2025; Diaz et al., 2019; Bhat et al., 2018; Gowrisankar and Clark, 2016; Haspula and Clark, 2021; Marins et al., 2017). One of the first studies investigating the influence of hypertension on astrocytes showed that in stroke-prone SHR rats, astrocytes swelled around the capillaries, due to increased endothelial permeability, which in turn led to their fibrosis (Tagami et al., 1991). The dead neurons were detected adjacent to the fibrous astrocytes, suggesting that dysfunction of astrocytes disturbs the neural environment, leading to neuronal death. Further studies have confirmed structural changes in astrocytes, known as astrogliosis, in stroke-prone SHR (Yamagata, 2012) and SHR (Sabbatini et al., 2002; Tomassoni et al., 2004; Marins et al., 2017). Astrogliosis (also termed reactive gliosis) is a process in which normal astrocytes undergo hypertrophy and proliferation in response to brain injury and become reactive astrocytes. Typically, the term astrogliosis refers to neurodegenerative diseases (Lagos-Cabré et al., 2020), however, arterial hypertension, which induces cerebrovascular changes, can also lead to brain damage, neurodegeneration, and vascular dementia. The transformation of quiescent into reactive astrocytes may result in the formation of a glial scar (Tomassoni et al., 2004; Lagos-Cabré et al., 2020). Although reactive gliosis is a normal physiological response that can protect brain cells from further damage, it also has detrimental effects on neuronal survival, by creating a non-permissive environment for axonal repair. In astrogliosis, the expression of several proteins is enhanced, including glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP) and inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS). Increased GFAP immunoreactivity was detected in astrocytes of SHR rats in the hippocampus (Sabbatini et al., 2002), frontal cortex, occipital cortex, and striatum (Tomassoni et al., 2004), and in the intermediate insular cortex (Marins et al., 2017). Elevated GFAP levels were also detected in hippocampal astrocytes in a 2-kidney-1-clip (Bhat et al., 2018), DOCA (Pietranera et al., 2006), and high-salt diet-induced model of chronic hypertension (Deng et al., 2017). Expression of inducible NO synthase (iNOS) by reactive astrocytes was observed in stroke-prone SHR (Gotoh et al., 1996). The distribution of iNOS+ astrocytes colocalized with the brain histological lesions observed in this model, i.e., petechiae and edema, suggesting that NO generation due to iNOS activation may be involved in the development of hypertensive cerebral lesions (Gotoh et al., 1996).

In addition to the increased expression of GFAP and iNOS, astrogliosis also results in the expression of pro-inflammatory cytokines, including tumor necrosis factor α and β, interleukins, and interferons (Chen and Swanson, 2003). These mediators of inflammation impair the glial trophic support of both the vasculature and neurons (Iadecola, 2013), leading to neuronal injury and neurodegeneration (Chen and Swanson, 2003). Upregulated expression of tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α), as well as pro-inflammatory interleukin-6 (IL-6) and interleukin-1β (IL-1β), was detected in astrocytes in a high salt diet-induced model of chronic hypertension (Deng et al., 2017). A shift toward pro-inflammatory TNF-α and a decrease in anti-inflammatory interleukin-10 (IL-10) in both cortex and hippocampus was also shown in the 2-kidney-1-clip model of hypertensive rats (Bhat et al., 2018). Different results were presented by Haspula and Clark (2021). These authors reported that not only the mRNA expression of pro-inflammatory IL-1β, but also the mRNA expression of anti-inflammatory IL-10, was significantly elevated in brainstem and cerebellar astrocytes isolated from SHR compared with Wistar astrocytes. A further part of the studies showed that ANG II treatment resulted in an inhibitory effect on IL-10 gene expression in astrocytes from both brain regions of SHR and Wistar rats, as well as an increase in IL-1β gene expression in brainstem astrocytes from both strains (Haspula and Clark, 2021). Similar pro-inflammatory effects of ANG II were described in other research studies (Benicky et al., 2011; Gowrisankar and Clark, 2016; Bhat et al., 2018). Gowrisankar and Clark (2016) demonstrated that ANG II could trigger an increase in IL-6 mRNA and protein expression in astroglial cultures obtained from SHRs and normotensive control Wistar rats. Moreover, ANG II receptor blockers have been shown to limit inflammatory responses in the brain, suggesting a dependence of neuroinflammatory responses on the AT1 receptor (Benicky et al., 2011; Bhat et al., 2018).

Astrocytic activation also results in the increased production of reactive oxygen species (ROS), leading to neuronal injury and neurodegeneration (Chen and Swanson, 2003). There is a wealth of data supporting the role of ROS in hypertension; however, these data are derived from peripheral cell systems, including resistance arteries and the kidneys (Gowrisankar and Clark, 2016). Few experimental studies performed on isolated astrocytes have shown that in the 2-kidney-1-clip model of hypertension, there is an increased activation of NADPH oxidase and ROS production. Further experiments revealed that inhibition of AT1 receptor, independent of its blood pressure-lowering effect, prevents the activation of NADPH oxidase and ROS production (Bhat et al., 2018). Similar results were obtained by studies Gowrisankar and Clark (2016), in which ANG II also induced ROS generation, and there were no significant differences between ROS generation in SHR-derived astrocytes as compared to the Wistar samples, indicating that an excessive production of ROS in the brain plays a crucial role in the pathogenesis of ANG II-dependent hypertension.

Furthermore, several research groups have noted that hypertension alters intracellular astrocyte Ca2+ dynamics (Tallant and Higson, 1997; Diaz et al., 2019). Tallant and Higson (1997) showed that in medullary and cerebellar, but not cortical or hypothalamic astrocytes from neonatal mice, ANG II stimulates a PLC/IP3-mediated increase in Ca2+ concentration via AT1 receptor as well as PGI2 release. A similar observation in the same model of hypertension, but in adult mice, was reported by Diaz et al. (2019). In these studies, increases of spontaneous and myogenic-evoked Ca2+ events were associated with enhanced astrocyte TRPV4 channel activity and expression. Moreover, elevated basal astrocyte Ca2+ activity was associated with a greater contribution to resting parenchymal arterioles tone (Diaz et al., 2019). Although it is not entirely clear how this contributes to pathogenesis, the authors hypothesized that sustained intracellular Ca2+ elevation in astrocytes could trigger or facilitate the transition of these cells to a proinflammatory state.

Hypertension leads also to dysfunction of the glymphatic system. Experimental investigations have shown that the glymphatic system is considerably impaired in SHRs (Xia et al., 2025; Mortensen et al., 2019) and angiotensin II-induced hypertension (Mestre et al., 2018). Mortensen et al. (2019) and Xia et al. (2025) used dynamic contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging to show that SHRs have delayed glymphatic transport relative to normotensive rats (Mortensen et al., 2019; Xia et al., 2025). This impairment of the glymphatic system in hypertension may be associated with changes in arterial pulsatility produced by arterial stiffness, which disturbs the dynamics of cerebrospinal fluid influx (Krings et al., 2025; Iliff et al., 2012). Moreover, Xia et al. (2025) demonstrated reduced AQP4 expression in the brainstem and olfactory bulb of SHRs, which likely leads to a reduction in fluid transport and clearance (Xia et al., 2025; Klostranec et al., 2021).

Impairment of glymphatic transport in hypertension and decreased efficiency in waste clearance mechanisms may potentially lead to the accumulation of neurotoxic substances, such as Aβ, tau, and α-synuclein. This, in turn, is involved in an increased risk of developing neurodegenerative diseases in hypertension (Iliff et al., 2012).

Considering the importance of astrocyte-neuron and astrocyte-vessel communication, structural and functional changes of astrocytes induced by hypertension could have significant adverse effects on the neurovascular unit and brain plasticity.

4.3 Impact on pericytes

There are not much data in the literature directly reporting the effects of arterial hypertension on the structure or function of the brain microvascular pericytes. Few studies have found that vascular alterations associated with hypertension, such as up-regulation of vasoconstricting substances and oxidative stress, can lead to enhanced pericyte contractility and, as a result, capillary rarefaction (Goligorsky, 2010; Hirunpattarasilp et al., 2019). Wu et al. (2020) showed that brain microvascular pericytes from SHRs had abnormal levels of several miRNAs compared to the normotensive group. Authors suggested that these pericyte miRNAs could be potential biomarkers or therapeutic targets for hypertension (Wu et al., 2020). The latest research shows that pericyte metabolism shifts toward glycolysis under hypertensive conditions. This adaptation occurs despite the presence of sufficient oxygen, showing that pericytes prioritize rapid energy production during stress in order to survive and maintain vascular integrity (Morton et al., 2025).

The small number of studies regarding the effect of hypertension on pericytes, suggest that functional and structural changes in pericytes in response to increased arterial blood pressure are relatively less understood compared to other components of the neurovascular unit.

5 Conclusion

Arterial hypertension has an adverse effect on all components of the neurovascular unit.

The most popular animal models used to study the influence of hypertension on the neurovascular unit include SHRs, stroke-prone SHRs, two-kidney two-clip models, and angiotensin II-induced hypertension. Regardless of the experimental model, the results showed increased endothelial permeability, BBB disruption, glycocalyx damage, an increase in adhesion molecule expression, astrogliosis, changes in intracellular astrocyte Ca2+ dynamics, impairment of the glymphatic system and possibly pericyte dysfunction. Furthermore, there is a disruption in communication between neurons, astrocytes, and microvessels. All of these changes ultimately lead to poor neurovascular coupling and insufficient functional hyperemia, which in turn contributes to cognitive decline and hypertension-related dementia.

Understanding the changes occurring in the structure of the neurovascular unit in hypertension should enable the development of antihypertensive therapy with a protective effect on the higher brain functions. Indeed, several studies have linked antihypertensive treatment to decreased cognitive impairment (Iadecola and Gottesman, 2019).

Statements

Author contributions

EK: Conceptualization, Writing – review & editing, Visualization. MA: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declared that no financial support was not received for this work and/or its publication.

Conflict of interest

The author(s) declared that this work was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declared that generative AI was not used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1

Abbott N. J. Rönnbäck L. Hansson E. (2006). Astrocyte-endothelial interactions at the blood-brain barrier.Nat. Rev. Neurosci.741–53. 10.1038/nrn1824

2

Alarcon-Martinez L. Yilmaz-Ozcan S. Yemisci M. Schallek J. Kılıç K. Can A. et al (2018). Capillary pericytes express α-smooth muscle actin, which requires prevention of filamentous-actin depolymerization for detection.eLife21:e34861.

3

Andrews A. M. Jaron D. Buerk D. G. Barbee K. A. (2014). Shear stress-induced NO production is dependent on ATP autocrine signaling and capacitative calcium entry.Cell. Mol. Bioeng.7510–520. 10.1007/s12195-014-0351-x

4

Armulik A. Genové G. Mäe M. Nisancioglu M. H. Wallgard E. Niaudet C. et al (2010). Pericytes regulate the blood-brain barrier.Nature468557–561. 10.1038/nature09522

5

Ayloo S. Gu C. (2019). Transcytosis at the blood-brain barrier.Curr. Opin. Neurobiol.5732–38. 10.1016/j.conb.2018.12-014

6

Baghirov H. (2025). Mechanisms of receptor-mediated transcytosis at the blood-brain barrier.J. Control. Release381:113595. 10.1016/j.jconrel.2025.113595

7

Bailey E. L. Wardlaw J. M. Graham D. Dominiczak A. F. Sudlow C. L. M. Smith C. (2011). Cerebral small vessel endothelial structural changes predate hypertension in stroke-prone spontaneously hypertensive rats: A blinded, controlled immunohistochemical study of 5- to 21-week-old rats.Neuropathol. Appl. Neurobiol.37711–726. 10.1111/j.1365-2990.2011.01170.x

8

Bandopadhyay R. Orte C. Lawrenson J. G. Reid A. R. De Silva S. Allt G. (2001). Contractile proteins in pericytes at the blood-brain and blood-retinal barriers.J. Neurocytol.3035–44. 10.1023/a:1011965307612

9

Beckman J. S. Beckman T. W. Chen J. Marshall P. A. Freeman B. A. (1990). Apparent hydroxyl radical production by peroxynitrite: Implications for endothelial injury from nitric oxide and superoxide.Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A.871620–1624. 10.1073/pnas.87.4.1620

10

Bell R. D. Winkler E. A. Sagare A. P. Singh I. LaRue B. Deane R. et al (2010). Pericytes control key neurovascular functions and neuronal phenotype in the adult brain and during brain aging.Neuron68409–427. 10.1016/j.neuron.2010.09.043

11

Benicky J. Sánchez-Lemus E. Honda M. Pang T. Orecna M. Wang J. et al (2011). Angiotensin II AT1 receptor blockade ameliorates brain inflammation.Neuropsychopharmacology36857–870. 10.1038/npp.2010.225

12

Berthiaume A. A. Grant R. I. McDowell K. P. Underly R. G. Hartmann D. A. Levy M. et al (2018). Dynamic remodeling of pericytes in vivo maintains capillary coverage in the adult mouse brain.Cell Rep.228–16. 10.1016/j.celrep.2017.12.016

13

Bhat S. A. Goel R. Shukla S. Shukla R. Hanif K. (2018). Angiotensin receptor blockade by inhibiting glial activation promotes hippocampal neurogenesis via activation of wnt/β-catenin signaling in hypertension.Mol. Neurobiol.555282–5298. 10.1007/s12035-017-0754-5

14

Biancardi V. C. Son S. J. Ahmadi S. Filosa J. A. Stern J. E. (2014). Circulating angiotensin II gains access to the hypothalamus and brain stem during hypertension via breakdown of the blood-brain barrier.Hypertension63572–579. 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.113.01743

15

Blankenberg S. Barbaux S. Tiret L. (2003). Adhesion molecules and atherosclerosis.Atherosclerosis170191–203. 10.1016/S0021-9150(03)00097-2

16

Blocki A. Beyer S. Jung F. Raghunath M. (2018). The controversial origin of pericytes during angiogenesis - Implications for cell-based therapeutic angiogenesis and cell-based therapies.Clin. Hemorheol. Microcirc.69215–232. 10.3233/CH-189132

17

Bosch A. J. Harazny J. M. Kistner I. Friedrich S. Wojtkiewicz J. Schmieder R. E. (2017). Retinal capillary rarefaction in patients with untreated mild-moderate hypertension.BMC Cardiovasc. Disord.17:300. 10.1186/s12872-017-0732-x

18

Bourdet D. L. Pollack G. M. Thakker D. R. (2006). Intestinal absorptive transport of the hydrophilic cation ranitidine: A kinetic modeling approach to elucidate the role of uptake and efflux transporters and paracellular vs. transcellular transport in Caco-2 cells.Pharm. Res.231178–1187. 10.1007/s11095-006-0204-y

19

Butt A. M. Jones H. C. Abbott N. J. (1990). Electrical resistance across the blood-brain barrier in anaesthetized rats: A developmental study.J. Physiol.42947–62. 10.1113/jphysiol.1990.sp018243

20

Calcinaghi N. Wyss M. T. Jolivet R. Singh A. Keller A. L. Winnik S. et al (2013). Multimodal imaging in rats reveals impaired neurovascular coupling in sustained hypertension.Stroke441957–1964. 10.1161/STROKEAHA.111.000185

21

Candido V. B. Perego S. M. Ceroni A. Metzger M. Colquhoun A. Michelini L. C. (2023). Trained hypertensive rats exhibit decreased transcellular vesicle trafficking, increased tight junctions’ density, restored blood-brain barrier permeability and normalized autonomic control of the circulation.Front. Physiol.14:1069485. 10.3389/fphys.2023.1069485

22

Capone C. Faraco G. Peterson J. R. Coleman C. Anrather J. Milner T. A. et al (2012). Central cardiovascular circuits contribute to the neurovascular dysfunction in angiotensin II hypertension.J. Neurosci.324878–4886. 10.1523/jneurosci.6262-11.2012

23

Chen B. R. Kozberg M. G. Bouchard M. B. Shaik M. A. Hillman E. M. C. (2014). A critical role for the vascular endothelium in functional neurovascular coupling in the brain.J. Am. Heart Assoc.3:e000787. 10.1161/JAHA.114.000787

24

Chen Y. Swanson R. A. (2003). Astrocytes and brain injury.J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab.23137–149. 10.1097/01.WCB.0000044631.80210.3C

25

Chien S. Li S. Shyy Y. J. (1998). Effects of mechanical forces on signal transduction and gene expression in endothelial cells.Hypertension31162–169. 10.1161/01.hyp.31.1.162

26

Coffman T. M. (2011). Under pressure: The search for the essential mechanisms of hypertension.Nat. Med.171402–1409. 10.1038/nm.2541

27

Curry F. E. Adamson R. H. (2012). Endothelial glycocalyx: Permeability barrier and mechanosensor.Ann. Biomed. Eng.40828–839. 10.1007/s10439-011-0429-8

28

Dahlöf B. (2007). Prevention of stroke in patients with hypertension.Am. J. Cardiol.10017J–24J. 10.1016/j.amjcard.2007.05.010

29

Dalkara T. Gursoy-Ozdemir Y. Yemisci M. (2011). Brain microvascular pericytes in health and disease.Acta Neuropathol.1221–9. 10.1007/s00401-011-0847-6

30

Daneman R. Prat A. (2015). The blood–brain barrier.Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol.7:a0200412. 10.1101/cshperspect.a020412

31

Daneman R. Zhou L. Kebede A. A. Barres B. A. (2010). Pericytes are required for the blood-brain barrier integrity during embryogenesis.Nature468562–566. 10.1038/nature09513

32

De Silva T. M. Faraci F. M. (2013). Effects of angiotensin II on the cerebral circulation: Role of oxidative stress.Front. Physiol.3:484. 10.3389/fphys.2012.00484

33

Deng Z. Wang Y. Zhou L. Shan Y. Tan S. Cai W. et al (2017). High salt-induced activation and expression of inflammatory cytokines in cultured astrocytes.Cell Cycle16785–794. 10.1080/15384101.2017.1301330

34

Desouza C. A. Dengel D. R. Macko R. F. Cox K. Seals D. R. (1997). Elevated levels of circulating cell adhesion molecules in uncomplicated essential hypertension.Am. J. Hypertens.101335–1341. 10.1016/S0895-7061(97)00268-9

35

Diaz J. R. Kim K. J. Brands M. W. Filosa J. A. (2019). Augmented astrocyte microdomain Ca2+ dynamics and parenchymal arteriole tone in angiotensin II-infused hypertensive mice.Glia67551–565. 10.1002/glia.23564

36

Durham J. T. Surks K. Dulmovits B. M. Herman I. M. (2014). Pericyte contractility controls endothelial cell cycle progression and sprouting: Insights into angiogenic switch mechanics.Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol.307C878–C892. 10.1152/ajpcell.00185.2014

37

Faraco G. Sugiyama Y. Lane D. Garcia-Bonilla L. Chang H. Santisteban M. M. et al (2016). Perivascular macrophages mediate the neurovascular and cognitive dysfunction associated with hypertension.J. Clin. Invest.1264674–4689. 10.1172/JCI86950

38

Farshori P. Kachar B. (1999). Redistribution and phosphorylation of occludin during opening and resealing of tight junctions in cultured epithelial cells.J. Membr. Biol.170147–156. 10.1007/s002329900544

39

Fernández-Klett F. Offenhauser N. Dirnagl U. Priller J. Lindauer U. (2010). Pericytes in capillaries are contractile in vivo, but arterioles mediate functional hyperemia in the mouse brain.Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A.10722290–22295. 10.1073/pnas.1011321108

40

Fleegal-DeMotta M. A. Doghu S. Banks W. A. (2009). Angiotensin II modulates BBB permeability via activation of the AT 1 receptor in brain endothelial cells.J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab.29640–647. 10.1038/jcbfm.2008.158

41

Foote C. A. Soares R. N. Ramirez-Perez F. I. Ghiarone T. Aroor A. Manrique-Acevedo C. et al (2022). Endothelial glycocalyx.Compr. Physiol.123781–3811. 10.1002/cphy.c210029

42

Fragas M. G. Candido V. B. Davanzo G. G. Rocha-Santos C. Ceroni A. Michelini L. C. (2021). Transcytosis within PVN capillaries: A mechanism determining both hypertension-induced blood-brain barrier dysfunction and exercise-induced correction.Am. J. Physiol. Regul. Integr. Comp. Physiol.321R732–R741. 10.1152/ajpregu.00154.2020

43

Freitas F. Estato V. Reis P. Castro-Faria-Neto H. C. Carvalho V. Torres R. et al (2017). Acute simvastatin treatment restores cerebral functional capillary density and attenuates angiotensin II-induced microcirculatory changes in a model of primary hypertension.Microcirculation24:e12416. 10.1111/micc.12416

44

Girouard H. Park L. Anrather J. Zhou P. Iadecola C. (2007). Cerebrovascular nitrosative stress mediates neurovascular and endothelial dysfunction induced by angiotensin II.Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol.27303–309. 10.1161/01.ATV.0000253885.41509.25

45

Gloor S. M. Wachtel M. Bolliger M. F. Ishihara H. Landmann R. Frei K. (2001). Molecular and cellular permeability control at the blood-brain barrier.Brain Res. Rev.36258–264. 10.1016/S0165-0173(01)00102-3

46

Goligorsky M. S. (2010). Microvascular rarefaction: The decline and fall of blood vessels.Organogenesis61–10. 10.4161/org.6.1.10427

47

Gotoh K. Kikuchi H. Kataoka H. Nagata I. Nozaki K. Takahashi J. C. et al (1996). Altered nitric oxide synthase immunoreactivity in the brain of stroke-prone spontaneously hypertensive rats.Acta Neuropathol.92123–129. 10.1007/s004010050499

48

Gowrisankar Y. V. Clark M. A. (2016). Angiotensin II induces interleukin-6 expression in astrocytes: Role of reactive oxygen species and NF-κB.Mol. Cell. Endocrinol.437130–141. 10.1016/j.mce.2016.08.013

49

Gryglewski R. J. Korbut R. Uracz W. Malinski T. (1997). Crossroads of L-arginine/arachidonate metabolism.Thromb. Haemost.78191–194. 10.1055/s-0038-1657524

50

Günzel D. Yu A. S. L. (2013). Claudins and the modulation of tight junction permeability.Physiol. Rev.93525–569. 10.1152/physrev.00019.2012

51

Hall C. N. Reynell C. Gesslein B. Hamilton N. B. Mishra A. Sutherland B. A. et al (2014). Capillary pericytes regulate cerebral blood flow in health and disease.Nature50855–60. 10.1038/nature13165

52

Hamilton N. B. Attwell D. Hall C. N. (2010). Pericyte-mediated regulation of capillary diameter: A component of neurovascular coupling in health and disease.Front. Neuroenergetics2:5. 10.3389/fnene.2010.00005

53

Hartmann D. A. Underly R. G. Grant R. I. Watson A. N. Lindner V. Shih A. Y. (2015). Pericyte structure and distribution in the cerebral cortex revealed by high-resolution imaging of transgenic mice.Neurophotonics2:041402. 10.1117/1.NPh.2.4.041402

54

Haspula D. Clark M. A. (2021). Contrasting roles of ang II and ACEA in the regulation of IL10 and IL1β gene expression in primary SHR astroglial cultures.Molecules26:3012. 10.3390/molecules26103012

55

Hirase T. Staddon J. M. Saitou M. Ando-Akatsuka Y. Itoh M. Furuse M. et al (1997). Occludin as a possible determinant of tight junction permeability in endothelial cells.J. Cell Sci.1101603–1613. 10.1242/jcs.110.14.1603

56

Hirunpattarasilp C. Attwell D. Freitas F. (2019). The role of pericytes in brain disorders: From the periphery to the brain.J. Neurochem.150648–665. 10.1111/jnc.14725

57

Hoopes S. L. Garcia V. Edin M. L. Schwartzman M. L. Zeldin D. C. (2015). Vascular actions of 20-HETE.Prostaglandins Other Lipid Mediat.1209–16. 10.1016/j.prostaglandins.2015.03.002

58

Huber J. D. Egleton R. D. Davis T. P. (2001). Molecular physiology and pathophysiology of tight junctions in the blood -brain barrier.Trends Neurosci.24719–725. 10.1016/s0166-2236(00)02004-x

59

Iadecola C. (2013). The pathobiology of vascular dementia.Neuron80844–866. 10.1016/j.neuron.2013.10.008

60

Iadecola C. (2017). The neurovascular unit coming of age: A journey through neurovascular coupling in health and disease.Neuron9617–42. 10.1016/j.neuron.2017.07.030

61

Iadecola C. Gottesman R. F. (2019). Neurovascular and cognitive dysfunction in hypertension.Circ. Res.1241025–1044. 10.1161/circresaha.118.313260

62

Iadecola C. Pelligrino D. A. Moskowitz M. A. Lassen N. A. (1994). Nitric oxide synthase inhibition and cerebrovascular regulation.J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab.14175–192. 10.1038/jcbfm.1994.25

63

Iadecola C. Smith E. E. Anrather J. Gu C. Mishra A. Misra S. et al (2023). The neurovasculome: Key roles in brain health and cognitive impairment: A scientific statement from the american heart association/american stroke association.Stroke54e251–e271. 10.1161/STR.0000000000000431

64

Iliff J. J. Wang M. Liao Y. Plogg B. A. Peng W. Gundersen G. A. et al (2012). A paravascular pathway facilitates CSF flow through the brain parenchyma and the clearance of interstitial solutes, including amyloid β.Sci. Transl. Med.4:147ra111. 10.1126/scitranslmed.3003748

65

Johansson B. B. (1999). Hypertension mechanisms causing stroke.Clin. Exp. Pharmacol. Physiol.26563–565. 10.1046/j.1440-1681.1999.03081.x

66

Kazama K. Wang G. Frys K. Anrather J. Iadecola C. (2003). Angiotensin II attenuates functional hyperemia in the mouse somatosensory cortex.Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol.2851890–1899. 10.1152/ajpheart.00464.2003

67

Khennouf L. Gesslein B. Brazhe A. Octeau J. C. Kutuzov N. Khakh B. S. et al (2018). Active role of capillary pericytes during stimulation-induced activity and spreading depolarization.Brain1412032–2046. 10.1093/brain/awy143

68

Kisler K. Nelson A. R. Rege S. V. Ramanathan A. Wang Y. Ahuja A. et al (2017). Pericyte degeneration leads to neurovascular uncoupling and limits oxygen supply to brain.Nat. Neurosci.20406–416. 10.1038/nn.4489

69

Kisler K. Nikolakopoulou A. M. Sweeney M. D. Lazic D. Zhao Z. Zlokovic B. V. (2020). Acute ablation of cortical pericytes leads to rapid neurovascular uncoupling.Front. Cell. Neurosci.14:27. 10.3389/fncel.2020.00027

70

Klostranec J. M. Vucevic D. Bhatia K. D. Kortman H. G. J. Krings T. Murphy K. P. et al (2021). Current concepts in intracranial interstitial fluid transport and the glymphatic system: Part I-anatomy and physiology.Radiology301502–514. 10.1148/radiol.2021202043

71

Kniesel U. Wolburg H. (2000). Tight junctions of the blood-brain barrier.Cell. Mol. Neurobiol.2057–76. 10.1023/a:1006995910836

72

Knowland D. Arac A. Sekiguchi K. J. Hsu M. Lutz S. E. Perrino J. et al (2014). Stepwise recruitment of transcellular and paracellular pathways underlies blood-brain barrier breakdown in stroke.Neuron82603–617. 10.1016/j.neuron.2014.03.003

73

Komarova Y. Malik A. B. (2010). Regulation of endothelial permeability via paracellular and transcellular transport pathways.Annu. Rev. Physiol.72463–493. 10.1146/annurev-physiol-021909-135833

74

Kozniewska E. Oseka M. Stys T. (1992). Effects of endothelium-derived nitric oxide on cerebral circulation during normoxia and hypoxia in the rat.J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab.12311–317. 10.1038/jcbfm.1992.43

75

Kozniewska E. Skolasinska K. Rutczynska Z. (1982). “Severity of hypertension, ultrastructure of cerebral cortex and cerebral blood flow in the inbred strain of spontaneously hypertensive stroke resistant rats,” in Hypertensive mechanisms, edsRascherW.CloughD.GantenD. (Stuttgart: F. K. Schattauer Verlag), 345–349.

76

Krings T. Takemoto Y. Mori K. Kee T. P. (2025). The glymphatic system and its role in neurovascular diseases.J. Neuroendovasc. Ther.192025–2020. 10.5797/jnet.ra.2025-0020

77

Kutuzov N. Flyvbjerg H. Lauritzen M. (2018). Contributions of the glycocalyx, endothelium, and extravascular compartment to the blood–brain barrier.Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A.115E9429–E9438. 10.1073/pnas.1802155115

78

Lagos-Cabré R. Burgos-Bravo F. Avalos A. M. Leyton L. (2020). Connexins in astrocyte migration.Front. Pharmacol.10:1546. 10.3389/fphar.2019.01546

79

Langen U. H. Ayloo S. Gu C. (2019). Development and cell biology of the blood-brain barrier.Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol.35591–613. 10.1146/annurev-cellbio-100617-062608

80

Larsen B. Skinhoj E. Lassen N. A. (1978). Variations in regional cortical blood flow in the right and left hemispheres during automatic speech.Brain101193–209. 10.1093/brain/101.2.193

81

Lassen N. A. Ingvar D. H. Skinhøj E. (1978). Brain function and blood flow.Sci. Am.23962–71. 10.1038/scientificamerican1078-62

82

Lia A. Di Spiezio A. Speggiorin M. Zonta M. (2023). Two decades of astrocytes in neurovascular coupling.Front. Netw. Physiol.3:1162757. 10.3389/fnetp.2023.1162757

83

Liu Y. Liu T. McCarron R. M. Spatz M. Feuerstein G. Hallenbeck J. M. et al (1996). Evidence for activation of endothelium and monocytes in hypertensive rats.Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol.270H2125–H2131. 10.1152/ajpheart.1996.270.6.h2125

84

Lochhead J. J. Yang J. Ronaldson P. T. Davis T. P. (2020). Structure, function, and regulation of the blood-brain barrier tight junction in central nervous system disorders.Front. Physiol.11:914. 10.3389/fphys.2020.00914

85

Longden T. A. Dabertrand F. Koide M. Gonzales A. L. Tykocki N. R. Brayden J. E. et al (2017). Capillary K+-sensing initiates retrograde hyperpolarization to increase local cerebral blood flow.Nat. Neurosci.20717–726. 10.1038/nn.4533

86

Ma S. C. Li Q. Peng J. Y. Zhouwen J. L. Diao J. F. Niu J. X. et al (2017). Claudin-5 regulates blood-brain barrier permeability by modifying brain microvascular endothelial cell proliferation, migration, and adhesion to prevent lung cancer metastasis.CNS Neurosci. Ther.23947–960. 10.1111/cns.12764

87

Maeda K. J. McClung D. M. Showmaker K. C. Warrington J. P. Ryan M. J. Garrett M. R. et al (2021). Endothelial cell disruption drives increased blood-brain barrier permeability and cerebral edema in the Dahl SS/jr rat model of superimposed preeclampsia.Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol.320535–548. 10.1152/AJPHEART.00383.2020

88

Mai M. Hilgers K. F. Geiger H. (1996). Experimental studies on the role intracellular adhesion molecule-1 and lymphocyte function-associated antigen-1 in hypertensive nephrosclerosis.Hypertension28973–979. 10.1161/01.hyp.28.6.973

89

Marins F. R. Iddings J. A. Fontes M. A. P. Filosa J. A. (2017). Evidence that remodeling of insular cortex neurovascular unit contributes to hypertension-related sympathoexcitation.Physiol. Rep.5:e13156. 10.14814/phy2.13156

90

Mathiisen T. M. Lehre K. P. Danbolt N. C. Ottersen O. P. (2010). The perivascular astroglial sheath provides a complete covering of the brain microvessels: An electron microscopic 3D reconstruction.Glia581094–1103. 10.1002/glia.20990

91

Matin N. Pires P. W. Garver H. Jackson W. F. Dorrance A. M. (2016). DOCA-salt hypertension impairs artery function in rat middle cerebral artery and parenchymal arterioles.Microcirculation23571–579. 10.1111/micc.12308

92

Matsuoka R. L. Buck L. D. Vajrala K. P. Quick R. E. Card O. A. (2022). Historical and current perspectives on blood endothelial cell heterogeneity in the brain.Cell. Mol. Life Sci.79:372. 10.1007/s00018-022-04403-1

93

McConnell H. L. Mishra A. (2022). Cells of the blood-brain barrier: An overview of the neurovascular unit in health and disease.Methods Mol. Biol.24923–24. 10.1007/978-1-0716-2289-6_1

94

Meissner A. (2016). Hypertension and the brain: A risk factor for more than heart disease.Cerebrovasc. Dis.42255–262. 10.1159/000446082

95

Mestre H. Tithof J. Du T. Song W. Peng W. Sweeney A. M. et al (2018). Flow of cerebrospinal fluid is driven by arterial pulsations and is reduced in hypertension.Nat. Commun.9:4878. 10.1038/s41467-018-07318-3

96

Minshall R. D. Tiruppathi C. Vogel S. M. Malik A. B. (2002). Vesicle formation and trafficking in endothelial cells and regulation of endothelial barrier function.Histochem. Cell Biol.117105–112. 10.1007/s00418-001-0367-x

97

Mishra A. Reynolds J. P. Chen Y. Gourine A. V. Rusakov D. A. Attwell D. (2016). Astrocytes mediate neurovascular signaling to capillary pericytes but not to arterioles.Nat. Neurosci.191619–1627. 10.1038/nn.4428

98

Mitic L. L. Anderson J. M. (1998). Molecular architecture of tight junctions.Annu. Rev. Physiol.60121–142. 10.1146/annurev.physiol.60.1.121

99

Mohammadi M. T. Dehghani G. A. (2014). Acute hypertension induces brain injury and blood-brain barrier disruption through reduction of claudins mRNA expression in rat.Pathol. Res. Pract.210985–990. 10.1016/j.prp.2014.05.007

100

Mortensen K. N. Sanggaard S. Mestre H. Lee H. Kostrikov S. Xavier A. L. R. et al (2019). Impaired glymphatic transport in spontaneously hypertensive rats.J. Neurosci.396365–6377. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1974-18.2019

101

Morton L. Garza A. P. Debska-Vielhaber G. Villafuerte L. E. Henneicke S. Arndt P. et al (2025). Pericytes and extracellular vesicle interactions in neurovascular adaptation to chronic arterial hypertension.J. Am. Heart Assoc.14:e038457. 10.1161/JAHA.124.038457

102

Nag S. (1984). Cerebral endothelial surface charge in hypertension. Acta. Neuropathol.63, 276–81. 10.1007/BF00687333

103

Nag S. (1995). Role of the endothelial cytoskeleton in blood-brain-barrier permeability to protein.Acta Neuropathol.90454–460. 10.1007/BF00294805

104

Navarro P. Caveda L. Breviario F. Mandoteanu I. Lampugnani M. G. Dejana E. (1995). Catenin-dependent and –independent functions of vascular endothelial cadherin.J. Biol. Chem.27030965–30972. 10.1074/jbc.270.52.30965

105

Nehls V. Drenckhahn D. (1991). Heterogeneity of microvascular pericytes for smooth muscle type alpha-actin.J. Cell Biol.113147–154. 10.1083/jcb.113.1.147

106

Nikolakopoulou A. M. Montagne A. Kisler K. Dai Z. Wang Y. Huuskonen M. T. et al (2019). Pericyte loss leads to circulatory failure and pleiotrophin depletion causing neuron loss.Nat. Neurosci.221089–1098. 10.1038/s41593-019-0434-z

107

Nippert A. R. Mishra A. Newman E. A. (2018). Keeping the brain well fed: The role of capillaries and arterioles in orchestrating functional hyperemia.Neuron99248–250. 10.1016/j.neuron.2018.07.011

108

Nitta T. Hata M. Gotoh S. Seo Y. Sasaki H. Hashimoto N. et al (2003). Size-selective loosening of the blood-brain barrier in claudin-5-deficient mice.J. Cell Biol.161653–660. 10.1083/jcb.200302070

109

Ohtsuki S. Sato S. Yamaguchi H. Kamoi M. Asashima T. Terasaki T. (2007). Exogenous expression of claudin-5 induces barrier properties in cultured rat brain capillary endothelial cells.J. Cell. Physiol.21081–86. 10.1002/jcp.20823

110

Pelisch N. Hosomi N. Mori H. Masaki T. Nishiyama A. (2013). RAS inhibition attenuates cognitive impairment by reducing blood-brain barrier permeability in hypertensive subjects.Curr. Hypertens. Rev.993–98. 10.2174/15734021113099990003

111

Pelisch N. Hosomi N. Ueno M. Nakano D. Hitomi H. Mogi M. et al (2011). Blockade of AT1 receptors protects the blood-brain barrier and improves cognition in dahl salt-sensitive hypertensive rats.Am. J. Hypertens.24362–368. 10.1038/ajh.2010.241

112

Peppiatt C. M. Howarth C. Mobbs P. Attwell D. (2006). Bidirectional control of CNS capillary diameter by pericytes.Nature443700–704. 10.1038/nature05193

113

Perego S. Gomes P. Makuch-Martins M. Morais C. Michelini L. (2025). Altered transport mechanisms across the blood-brain barrier in renovascular hypertension: Effects of exercise training.Physiology40:S1. 10.1152/physiol.2025.40.S1.0228

114

Pietranera L. Saravia F. Gonzalez Deniselle M. C. Roig P. Lima A. De Nicola A. F. (2006). Abnormalities of the hippocampus are similar in deoxycorticosterone acetate-salt hypertensive rats and spontaneously hypertensive rats.J. Neuroendocrinol.18466–474. 10.1111/j.1365-2826.2006.01436.x

115

Presa J. L. Saravia F. Bagi Z. Filosa J. A. (2020). Vasculo-neuronal coupling and neurovascular coupling at the neurovascular unit: Impact of hypertension.Front. Physiol.11:584135. 10.3389/fphys.2020.584135

116

Przykaza Ł (2021). Understanding the connection between common stroke comorbidities, their associated inflammation, and the course of the cerebral ischemia/reperfusion cascade.Front. Immunol.12:782569. 10.3389/fimmu.2021.782569

117

Rabelink T. J. De Boer H. C. Van Zonneveld A. J. (2010). Endothelial activation and circulating markers of endothelial activation in kidney disease.Nat. Rev. Nephrol.6404–414. 10.1038/nrneph.2010.65

118

Reitsma S. Slaaf D. W. Vink H. van Zandvoort M. A. oude Egbrink M. G. (2007). The endothelial glycocalyx: Composition, functions, and visualization.Pflugers Arch.454345–359. 10.1007/s00424-007-0212-8

119

Resnick N. Gimbrone M. A. Jr. (1995). Hemodynamic forces are complex regulators of endothelial gene expression.FASEB J.9874–882. 10.1096/fasebj.9.10.7615157

120

Roy C. S. Sherrington C. S. (1890). On the regulation of the blood-supply of the brain.J. Physiol.1185–104. 10.1113/jphysiol.1890.sp000321

121

Rungta R. L. Chaigneau E. Osmanski B. F. Charpak S. (2018). Vascular compartmentalization of functional hyperemia from the synapse to the pia.Neuron99362–375.e4. 10.1016/j.neuron.2018.06.012

122

Sabbatini M. Catalani A. Consoli C. Marletta N. Tomassoni D. Avola R. (2002). The hippocampus in spontaneously hypertensive rats: An animal model of vascular dementia?Mech. Ageing Dev.123547–559. 10.1016/S0047-6374(01)00362-1

123

Santisteban M. M. Ahn S. J. Lane D. Faraco G. Garcia-Bonilla L. Racchumi G. et al (2020). Endothelium-macrophage crosstalk mediates blood-brain barrier dysfunction in hypertension.Hypertension76795–807. 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.120.15581

124

Santisteban M. M. Iadecola C. Carnevale D. (2023). Hypertension, neurovascular dysfunction and cognitive impairment.Hypertension8022–34. 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.122.18085

125

Sá-Pereira I. Brites D. Brito M. A. (2012). Neurovascular unit: A focus on pericytes.Mol. Neurobiol.45327–347. 10.1007/s12035-012-8244-2

126

Schaeffer S. Iadecola C. (2021). Revisiting the neurovascular unit.Nat. Neurosci.241198–1209. 10.1038/s41593-021-00904-7

127

Segarra M. Aburto M. R. Hefendehl J. Acker-Palmer A. (2019). Neurovascular interactions in the nervous system.Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol.35615–635. 10.1146/annurev-cellbio-100818-125142

128

Shalia K. K. Mashru M. R. Vasvani J. B. Mokal R. A. Mithbawkar S. M. Thakur P. K. (2009). Circulating levels of cell adhesion molecules in hypertension.Indian J. Clin. Biochem.24388–397. 10.1007/s12291-009-0070-6

129

Sims D. (1991). Recent advances in pericyte biology - Implications for health and disease.Can. J. Cardiol.7431–443.

130

Stoddart P. Satchell S. C. Ramnath R. (2022). Cerebral microvascular endothelial glycocalyx damage, its implications on the blood-brain barrier and a possible contributor to cognitive impairment.Brain Res.1780:147804. 10.1016/j.brainres.2022.147804

131

Suzuki K. Masawa N. Sakata N. Takatama M. (2003). Pathologic evidence of microvascular rarefaction in the brain of renal hypertensive rats.J. Stroke Cerebrovasc. Dis.128–16. 10.1053/jscd.2003.1

132

Suzuki K. Masawa N. Takatama M. (2001). The pathogenesis of cerebrovascular lesions in hypertensive rats.Med. Electron Microsc.34230–239. 10.1007/s007950100020

133

Tagami M. Kubota A. Nara Y. Yamori Y. (1991). Detailed disease processes of cerebral pericytes and astrocytes in stroke-prone SHR.Clin. Exp. Hypertens. A131069–1075. 10.3109/10641969109042113

134

Tallant E. A. Higson J. T. (1997). Angiotensin II activates distinct signal transduction pathways in astrocytes isolated from neonatal rat brain.Glia19333–342.

135

Tarantini S. Tucsek Z. Valcarcel-Ares M. N. Toth P. Gautam T. Giles C. B. et al (2016). Circulating IGF-1 deficiency exacerbates hypertension-induced microvascular rarefaction in the mouse hippocampus and retrosplenial cortex: Implications for cerebromicrovascular and brain aging.Age38273–289. 10.1007/s11357-016-9931-0

136

Tarbell J. M. Pahakis M. Y. (2006). Mechanotransduction and the glycocalyx.J. Intetern. Med.259339–350. 10.1111/j.1365-2796.2006.01620.x

137

Tjili T. M. July J. Darwin E. Syafrita Y. Suntoro V. A. Lukito P. P. et al (2025). Vascular endothelial cadherin dysfunction: A predictor of hypertensive nonlobar intracerebral hemorrhage.Surg. Neurol. Int.16:268. 10.25259/SNI_20_2025

138

Tomassoni D. Avola R. Di Tullio M. A. Sabbatini M. Vitaioli L. Amenta F. (2004). Increased expression of glial fibrillary acidic protein in the brain of spontaneously hypertensive rats.Clin. Exp. Hypertens.26335–350. 10.1081/CEH-120034138

139

Tsukamoto T. Nigam S. K. (1999). Role of tyrosine phosphorylation in the reassembly of occludin and other tight junction proteins.Am. J. Physiol.276F737–F750. 10.1152/ajprenal.1999.276.5.f737

140

Tummala P. E. Chen X. L. Sundell C. L. Laursen J. B. Hammes C. P. Alexander R. W. et al (1999). Angiotensin II induces vascular cell adhesion molecule-1 expression in rat vasculature: A potential link between the renin-angiotensin system and atherosclerosis.Circulation1001223–1229. 10.1161/01.CIR.100.11.1223

141

Ueno M. Sakamoto H. Tomimoto H. Akiguchi I. Onodera M. Huang C. L. et al (2004). Blood-brain barrier is impaired in the hippocampus of young adult spontaneously hypertensive rats.Acta Neuropathol.107532–538. 10.1007/s00401-004-0845-z

142

Vital S. A. Terao S. Nagai M. Granger D. N. (2010). Mechanisms underlying the cerebral microvascular responses to angiotensin II-induced hypertension.Microcirculation17641–649. 10.1111/j.1549-8719.2010.00060.x

143

Wachtel M. Frei K. Ehler E. Fontana A. Winterhalter K. Gloor S. M. (1999). Occludin proteolysis and increased permeability in endothelial cells through tyrosine phosphatase inhibition.J. Cell Sci.1124347–4356. 10.1242/jcs.112.23.4347

144

Weinbaum S. Zhang X. Han Y. Vink H. Cowin S. C. (2003). Mechanotransduction and flow across the endothelial glycocalyx.Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A.247988–7995. 10.1073/pnas.1332808100

145

Williams D. A. Flood M. H. (2015). Capillary tone: Cyclooxygenase, shear stress, luminal glycocalyx, and hydraulic conductivity (Lp).Physiol. Rep.3:e12370. 10.14814/phy2.12370

146

Williams L. R. Leggett R. W. (1989). Reference values for resting blood flow to organs of man.Clin. Phys. Physiol. Meas.10187–217. 10.1088/0143-0815/10/3/001

147

Winklewski P. J. Radkowski M. Wszedybyl-Winklewska M. Demkow U. (2015). Brain inflammation and hypertension: The chicken or the egg?J. Neuroinflammation12:85. 10.1186/s12974-015-0306-8

148

Wu Q. Yuan X. Li B. Yang J. Han R. Zhang H. et al (2020). Differential miRNA expression analysis of extracellular vesicles from brain microvascular pericytes in spontaneous hypertensive rats.Biotechnol. Lett.42389–401. 10.1007/s10529-019-02788-x

149

Xia Y. Lyu C. Chen P. Jiang Y. Qu C. Lyu X. et al (2025). The glymphatic system was impaired in spontaneously hypertensive rats.Sci. Rep.15:18321. 10.1038/s41598-025-02054-3

150

Yamagata K. (2012). Pathological alterations of astrocytes in stroke-prone spontaneously hypertensive rats under ischemic conditions.Neurochem. Int.6091–98. 10.1016/j.neuint.2011.11.002

151

Yamamoto M. Ramirez S. H. Sato S. Kiyota T. Cerny R. L. Kaibuchi K. et al (2008). Phosphorylation of claudin-5 and occludin by Rho kinase in brain endothelial cells.Am. J. Pathol.172521–533. 10.2353/ajpath.2008.070076

152

Yang A. C. Stevens M. Y. Chen M. B. Lee D. P. Stähli D. Gate D. et al (2020). Physiological blood-brain transport is impaired with age by a shift in transcytosis.Nature583425–430. 10.1038/s41586-020-2453-z

153