- 1Department of Urology, The Sixth People’s Hospital of Huizhou, Huizhou, Guangdong, China

- 2Department of Oncology and Hematology, The Sixth People’s Hospital of Huizhou, Huizhou, Guangdong, China

- 3Department of Urology, Lanxi People’s Hospital, Jinhua, Zhejiang, China

Superparamagnetic iron oxide nanoparticles (SPIONs) have emerged as transformative theranostic platforms in urological oncology. This review systematically synthesizes literature from PubMed, Web of Science, and Scopus (2010–2024) to evaluate SPION-based strategies for bladder cancer (BCa) and prostate cancer (PCa). We highlight their role in enhancing diagnostic precision (e.g., PSMA-targeted MRI, sentinel lymph node navigation) and enabling innovative therapies (e.g., magneto-photothermal synergy, ferroptosis immunomodulation). Key advantages include superior targeting, multimodal imaging capability, and the ability to overcome physiological barriers such as the blood-prostate and blood-urine barriers. While preclinical results are promising, clinical translation requires addressing biosafety, scalable production, and regulatory hurdles. SPIONs represent a robust alternative to conventional therapeutics, particularly in settings requiring precision and combinatory approaches.

Introduction

Bladder cancer (BCa) and prostate cancer (PCa), prevalent malignancies among men globally, pose significant threats to male health, necessitating innovative diagnostic and therapeutic solutions (Siegel et al., 2022; Sanli et al., 2017). BCa is characterized by high recurrence and progression rates, subjecting patients to repeated invasive surveillance post-surgery, while advanced cases often face therapeutic resistance and plummeting survival rates. Although widespread PSA screening has reduced overall PCa mortality, advanced metastatic disease, particularly castration-resistant prostate cancer (CRPC), remains a leading cause of death. Current diagnostic methods lack sufficient specificity, contributing to overtreatment, while therapeutic options for advanced stages are limited. Common challenges across both cancers include invasive diagnostics, inefficient treatments, drug resistance, and diminished quality of life. Consequently, there is an urgent need for novel platforms integrating precise diagnosis and effective therapy.

The advent of nanomedicine offers a revolutionary perspective to overcome these hurdles (Song et al., 2019; He et al., 2018; Jain et al., 2021). Nanomaterials, leveraging their unique size effects and high degree of tunability, represent promising platforms for theranostics (Song et al., 2019; He et al., 2018; Jain et al., 2021). Through surface engineering, they can achieve active or passive tumor targeting, enhancing accumulation at disease sites. Their superior drug-loading capacity allows for co-delivery of multiple therapeutic agents. They facilitate the integration of diagnostic, therapeutic, and monitoring functions within a single entity. Furthermore, they optimize pharmacokinetics, overcoming physiological barriers such as the blood-urine barrier (BUB) and blood-prostate barrier (BPB), utilizing the enhanced permeability and retention (EPR) effect or enabling specific transmembrane transport, thus paving new paths for precision medicine (Song et al., 2019; He et al., 2018; Jain et al., 2021; Alvarez et al., 2017; Gianchandani and Meng, 2012). Recent advances in nanomedicine have also highlighted the potential of other nanoparticle systems, such as silver nanoparticles for anticancer therapy (Doğan et al., 2025) and activated carbon-coated iron oxide nanocomposites for drug delivery (Doğan et al., 2024), which share common design principles with SPIONs. Similarly, chitosan-based formulations (Evcil et al., 2025) and adrenergic receptor targeting in gliomas (Gareev et al., 2025) illustrate the broader potential of nanomaterial-based theranostics.

Among nanomaterials, superparamagnetic iron oxide nanoparticles (SPIONs) stand out due to their unique physicochemical properties and extensive biomedical research foundation (Connell et al., 2015; Ferreira-Filho et al., 2024; Paw et al., 2025; Bakhtiary et al., 2016; Akhtar et al., 2022). SPIONs consist of a magnetite (Fe3O4) or maghemite (γ-Fe2O3) core coated with biocompatible materials (e.g., dextran, polyethylene glycol (PEG), silica) (Akhtar et al., 2022; Samrot et al., 2021). Their exceptional magnetic responsiveness underpins efficient imaging (e.g., MRI, magnetic particle imaging - MPI) and active interventions (e.g., magnetic targeting, magnetothermal therapy) (Samrot et al., 2021; Muthiah et al., 2013; Ali et al., 2021; Yan et al., 2024; Kara and Ozpolat, 2024; Zhi et al., 2020; Yoffe et al., 2013; Solar et al., 2015). Crucially, SPIONs can overcome physiological barriers like the BUB and BPB, enabling targeted accumulation at lesion sites. Their highly tunable physicochemical properties allow precise control over size, shape, surface charge, and chemistry via synthesis and surface modification, directly influencing in vivo stability, pharmacokinetics, and targeting efficiency (Samrot et al., 2021; Muthiah et al., 2013; Ali et al., 2021; Yan et al., 2024; Kara and Ozpolat, 2024; Zhi et al., 2020; Yoffe et al., 2013; Solar et al., 2015). Relatively good biocompatibility and potential biodegradability stem from the stability of the iron oxide core in physiological environments and the metabolic clearance of iron ions (Samrot et al., 2021; Muthiah et al., 2013; Ali et al., 2021; Yan et al., 2024; Kara and Ozpolat, 2024; Zhi et al., 2020; Yoffe et al., 2013; Solar et al., 2015). Significant potential for multifunctionalization enables facile surface conjugation of targeting ligands (antibodies, peptides), loading of fluorescent dyes, therapeutic drugs, nucleic acids, or photosensitizers, creating a highly modular “nanoplatform” (Samrot et al., 2021; Muthiah et al., 2013; Ali et al., 2021; Yan et al., 2024; Kara and Ozpolat, 2024; Zhi et al., 2020; Yoffe et al., 2013; Solar et al., 2015). Collectively, these properties confer substantial theranostic value to SPIONs, opening novel avenues for precision medicine in urological oncology. While the primary focus of this review is on iron oxide-based SPIONs, we also include representative hybrid magnetic nanoplatforms (e.g., J591-DSPE-SIPPs) where their design or function provides critical insights relevant to SPION development, and these are clearly labeled as such. The versatile journey and core mechanisms of SPIONs in tumor diagnosis and treatment are graphically summarized in Figure 1.

This review focuses on SPIONs as an advanced nanoplatform, systematically elucidating their recent research progress, application potential, and translational prospects in the integrated diagnosis and therapy of PCa and BCa. We will delve into the core mechanisms and representative case studies demonstrating how SPIONs enhance diagnostic precision (e.g., detection of micrometastases, sentinel lymph node navigation, non-invasive biomarker detection) and revolutionize therapeutic strategies (e.g., targeted delivery for efficacy enhancement, magneto-photothermal synergy, ferroptosis-immunomodulation). Concurrently, we will objectively examine key challenges regarding scalable manufacturing uniformity, long-term biosafety, targeting efficiency optimization, and clinical translation pathways. Based on this analysis, we will provide a prospective discussion on future directions, such as stimuli-responsive designs, multimodal technology integration, and personalized theranostics integration, aiming to propel the substantive transition of SPIONs from the laboratory to the clinic, ultimately benefiting patients.

Methods: literature search strategy

A systematic literature search was conducted using the PubMed, Web of Science, and Scopus databases for articles published between January 2010 and June 2024. Search keywords included: “superparamagnetic iron oxide nanoparticles,” “SPIONs,” “prostate cancer,” “bladder cancer,” “theranostics,” “magnetic nanoparticle,” “targeted drug delivery,” “MRI,” “MPI,” “sentinel lymph node,” “PSMA,” and combinations thereof. The inclusion criteria encompassed original research articles and authoritative reviews focusing on the application of SPIONs in the diagnosis, therapy, or theranostics of prostate or bladder cancer. Articles were excluded if they were not available in English, did not primarily involve iron oxide-based nanoparticles (unless providing direct comparative insights), or were focused on non-urological cancers without relevant mechanistic parallels. The selected evidence was synthesized to highlight key mechanistic insights, preclinical and clinical outcomes, and identified translational challenges, with an emphasis on providing a balanced and critical appraisal of the field’s current state.

Integrated applications and challenges of SPIONs in prostate cancer diagnosis and therapy

PCa poses a severe threat to male health globally, ranking as the second most common male malignancy. Its burden is particularly heavy in developed nations and shows a persistent upward trend with population aging (Siegel et al., 2022). Despite the reduction in overall mortality attributable to prostate-specific antigen (PSA)-based screening, advanced metastatic disease, especially castration-resistant prostate cancer (CRPC) resistant to androgen deprivation therapy (ADT), remains the primary cause of death, underscoring the urgent need for more precise diagnostics and effective therapeutics (Sekhoacha et al., 2022; Parker et al., 2020; Tilki et al., 2024; Wasim et al., 2022). Current clinical practice faces significant bottlenecks: widely used PSA screening lacks specificity, leading to numerous unnecessary and invasive biopsies (associated with bleeding and infection risks) (Andriole et al., 2009; Schröder et al., 2012; Negoita et al., 2018); emerging multiparametric MRI (mpMRI) improves lesion detection but faces limitations in accessibility, interpretive subjectivity, and insufficient discriminatory power for small or atypical lesions (Ahmed et al., 2017). Therapeutically, more sensitive monitoring tools are needed for biochemical recurrence after local treatments (surgery or radiotherapy); effective options for advanced stages, particularly CRPC, are scarce and offer limited survival benefit; and managing bone-related events (SREs) due to metastases is challenging, significantly impairing patient quality of life (Teo et al., 2019; Evans, 2018; Gamat and McNeel, 2017). SPIONs, with their unique superparamagnetism, highly tunable physicochemical properties, good biocompatibility, and strong multifunctionalization potential, offer innovative perspectives to address these challenges.

Molecular imaging diagnostics

The application of SPIONs in molecular imaging entered a new phase with breakthroughs in prostate-specific membrane antigen (PSMA) targeting. The iron-platinum immunomicelle platform J591-DSPE-SIPPs, developed by Taylor et al. (anti-PSMA antibody J591 conjugated to iron platinum nanomicelles), demonstrated an exceptionally high transverse relaxivity (r2) of 300.6 s−1·mM−1 (measured at 4.7 T), a 13-fold higher than commercial SPIONs attributed to its unique hybrid composition and targeting capability. This exceptional relaxivity, combined with fluorescent labeling, enabled highly sensitive and specific dual-modal (fluorescence/MRI) imaging of prostate cancer cells, significantly improving the detection of micrometastases and early metastatic deposits, thereby providing a powerful tool for accurate staging (Taylor et al., 2011). Peptide-based targeting strategies also show great promise. Examples include CQKHHNYLC peptide-SPIONs and SPIONs based on the Glu-Urea-Lys scaffold, which achieved significant tumor-specific accumulation in xenograft models due to high PSMA binding affinity, offering important directions for novel targeted probe development (Zhu et al., 2015). Innovation extends beyond probe design. The [Fe]MRI technique developed by Sillerud et al. enables precise, non-invasive quantification of SPION concentration with a remarkably low detection limit of 2 μM. Using gradient-echo sequences in xenograft models, this technique effectively discriminated between PSMA-positive and PSMA-negative tumor cells (a >15-fold difference in uptake), providing a robust quantitative tool for real-time, dynamic assessment of treatment response (e.g., efficacy of targeted drugs or radiotherapy), potentially guiding personalized treatment adjustments (Sillerud, 2018). In summary, PSMA-targeted SPIONs offer powerful tools for preclinical research and are entering early-phase clinical trials for precise staging. However, their routine integration into clinical practice awaits larger-scale validation and regulatory approval.

Clinical translation

SPION-guided sentinel lymph node dissection (sLND) is demonstrating transformative value, potentially optimizing lymph node staging strategies. Large-scale clinical studies by Winter and Geißen et al. (n = 104–218 patients) confirmed that sLND achieves consistently high sensitivity (88%–100%) and negative predictive value (>95%) in intermediate- and high-risk PCa patients. Its key advantage lies in successfully detecting micrometastases outside the range of conventional extended pelvic lymph node dissection (ePLND), thereby enabling a more accurate assessment of true nodal involvement (Winter et al., 2017; Geißen et al., 2019). Clinical trials using the SentiMag Pro II system further validated the reliability of this technology, achieving a remarkable 100% in vivo SLN detection rate in initial cohorts (Winter et al., 2017; Geißen et al., 2019). It is important to note that while sLND demonstrated high sensitivity in these studies, a single missed detection in the SentiMag Pro II trial resulted in an overall sensitivity of 94.4%, underscoring that the technique is highly effective but not infallible and may benefit from complementary imaging strategies (Winter et al., 2019). In addition, diagnostic applications are expanding into non-invasive liquid biopsy. Uhlirova et al. developed SOX-chitosan-SPIONs, ingeniously utilizing their pseudo-peroxidase activity to achieve highly sensitive colorimetric detection of sarcosine, a potential PCa biomarker (LOD = 5 μM). This nanozyme-based detection platform offers new hope for non-invasive early diagnosis and convenient therapeutic monitoring of PCa (Uhlirova et al., 2018). The sLND technique, particularly when standardized, represents a clinically ready tool that can refine surgical staging and potentially reduce the extent of unnecessary lymph node dissections. Its implementation in multicenter studies is a key near-term goal.

Therapeutic applications

Research focuses on leveraging SPIONs’ targeted delivery capabilities combined with synergistic physical energy strategies to overcome resistance, enhance efficacy, and reduce toxicity. PSMA-directed multifunctional theranostic platforms are particularly noteworthy. The Dox@Apt-hybr-TCL-SPIONs system, based on a PSMA aptamer, successfully integrated doxorubicin chemotherapy with MR imaging-guided targeted delivery, exemplifying visualized precision therapy (Yu et al., 2011). Integrating therapeutic radionuclides Scandium-44 (diagnostic PET) and Scandium-47 (therapeutic beta-emitter) with the PSMA-targeting ligand PSMA-617 and SPIONs forms a complex that innovatively combines the high sensitivity of PET diagnostics with the precise cytotoxic power of targeted radionuclide therapy, representing the forefront of theranostics and demonstrating significant tumor growth suppression (>70%) in preclinical models (Ünak et al., 2023). Other types of multifunctional carriers also demonstrate significant advantages, for example, Anti-prostate stem cell antigen (PSCA) antibody-modified PLGA-SPIONs significantly prolonged the release of docetaxel (up to 764 h) and effectively suppressed xenograft tumor growth in animal models (Gao et al., 2012). Liposome-SPION complexes constructed using the highly efficient targeting peptide SP204, identified via phage display, markedly enhanced the cytotoxic efficacy of co-loaded doxorubicin and vinorelbine against tumor cells, offering a novel approach to combat multidrug resistance (Yeh et al., 2016). Physical energy-assisted therapy has opened up new avenues for enhancing efficacy and reducing toxicity, Strategies combining physical energy with SPIONs open new paths for efficacy enhancement and toxicity reduction. The etoposide-loaded bovine serum albumin nanoparticle-coated SPIONs system (Eto-BSA@PAA@SPIONs) designed by Onbasli et al., combined with 808 nm NIR laser irradiation, synergistically enhanced cytotoxicity through laser-triggered precise drug release and photothermal effect-generated reactive oxygen species (ROS), reducing the IC50 of etoposide against LNCaP cells to a remarkable 0.08 μg/mL (Onbasli et al., 2022). The ingenious combination of electromagnetic hyperthermia (magnetic induction heating) with electrochemotherapy significantly increased cell membrane permeability to bleomycin via electroporation, dramatically enhancing the drug’s sensitivity against DU-145 resistant cells, providing an innovative physico-chemical solution to overcome common clinical chemoresistance (Vizcarra-Ramos et al., 2024). The application of biomimetic strategies further enhances targeting efficiency and biocompatibility. The exosome-based theranostic platform SPIONs@EXO-Dye leveraged homologous targeting (targeting efficiency: 66.48%, significantly superior to 34.57% for the free group), enabling highly sensitive magnetic particle imaging (MPI) guidance and successful implementation of photothermal-magnetothermal synergistic therapy, highlighting the immense potential of multimodal theranostic platforms (Liu et al., 2024). These therapeutic platforms showcase the potential of SPIONs to enhance drug efficacy and overcome resistance, yet their translation requires careful assessment of long-term safety and scalable manufacturing.

Integrated applications of SPIONs in bladder cancer diagnosis and therapy

BCa ranks among the top 10 most common cancers globally, exhibiting significant geographical and gender disparities (higher incidence in males) and characterized by high recurrence rates (Siegel et al., 2022; Sanli et al., 2017). Patients with non-muscle-invasive bladder cancer (NMIBC) face high recurrence risks post-surgery, enduring long-term, frequent invasive monitoring (cystoscopy) (Grimm et al., 2020; Sylvester et al., 2006; Ritch et al., 2020). Radical cystectomy for muscle-invasive bladder cancer (MIBC) is highly traumatic, severely impacting urinary and sexual function and quality of life. Furthermore, the high risk of post-operative lymph node and distant organ metastasis contributes to mortality rates reaching 50% (Galsky et al., 2016; Catto et al., 2022; Mitra et al., 2022). While targeted therapies and immunotherapies show significant potential for BCa based on improved biological understanding, advanced patients often develop resistance to systemic chemotherapy and immunotherapy or cannot tolerate their side effects, leading to 5-year survival rates below 40% (von der Maase et al., 2005; Antoni et al., 2017; Alifrangis et al., 2019; Lou et al., 2022). Major diagnostic bottlenecks persist: the gold standard cystoscopy is invasive, causing patient discomfort and urinary tract infection risk, while non-invasive urine cytology suffers from insufficient sensitivity, particularly for low-grade tumors, leading to missed diagnoses (Gopala et al., 2016; Yafi et al., 2015; Gandhi et al., 2018). Therefore, developing novel, efficient, low-toxicity, minimally invasive, or non-invasive diagnostic and therapeutic strategies is an urgent need in BCa. The unique local anatomy of the bladder (a cavity) and the primary local treatment modality (e.g., intravesical chemotherapy/immunotherapy) provide a highly promising and relatively direct application scenario for SPIONs. SPIONs can be delivered directly to the lesion site via instillation, leveraging their magnetic responsiveness for local concentration and retention while overcoming the blood-urine barrier.

Targeted intravesical delivery

The cisplatin-coordinated nanoparticles Pt-Fe-PNs, developed by Huang et al., exhibited excellent sustained release properties in artificial urine at 37 °C (approx. 30% release at 4 h, sustained release up to 4 days). Crucially, this nanosystem displayed intelligent temperature responsiveness, with significantly accelerated drug release at hyperthermia temperatures (42 °C–45 °C). This property provides a critical foundation for the precise synergistic implementation of intravesical chemotherapy and local hyperthermia, potentially enabling controlled burst release at the tumor site via external heating (e.g., radiofrequency or microwave), thereby improving efficacy (Huang et al., 2012). Bai et al.'s coaxial closely-arranged magnetic field system represents an advanced attempt at actively manipulating intravesical SPIONs. This system achieved precise and rapid (within 12 s) aggregation and positioning control of SPIONs instilled into rabbit bladders. Combined with the team’s self-developed magnetic particle imaging (MPI) device, this study achieved, for the first time, real-time visualization of SPION delivery and aggregation within the bladder in vivo. This prototype technology offers a highly promising solution for achieving precise, controllable targeted intravesical drug delivery in the clinic, although its efficacy in the larger, more complex human bladder with dynamic urine cycling requires validation in large-animal models (Bai et al., 2024). These delivery strategies highlight the potential for localized efficacy, but must be optimized for human anatomy and physiology.

Innovative therapeutic mechanisms

The pomegranate-like nanoparticles rPAE@SPIONs, constructed by Cai et al., achieved triple synergistic anti-tumor effects via NIR light triggering: (1) Mild photothermal effects promoting spatiotemporally controlled doxorubicin release at the tumor site; (2) Induction of ferroptosis, an iron-dependent form of regulated cell death, in tumor cells; (3) Simultaneous polarization of tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs) towards the anti-tumor M1 phenotype, enhancing local anti-tumor immune responses. This unique multi-mechanism synergistic strategy combining photothermal therapy, chemodynamic therapy, ferroptosis induction, and immunomodulation opens a novel pathway to overcome BCa’s inherent high recurrence challenge, demonstrating significant tumor growth inhibition in preclinical models (Cai et al., 2024). Research exploring SPIONs combined with other intravesical agents (e.g., immune checkpoint inhibitors, oncolytic viruses, gene therapy drugs) is ongoing. Their magnetic targeting potential could significantly increase drug concentration and dwell time at the bladder mucosa, particularly tumor sites, while reducing systemic exposure and toxicity. In summary, this multi-mechanism approach represents a promising investigational strategy to address BCa recurrence in preclinical models. Its clinical translation will require rigorous safety assessment and confirmation of efficacy in human trials.

Cross-cancer challenges and insights

Despite the immense potential demonstrated by SPION technology in urologic oncology, its clinical translation faces a series of common and cancer-specific challenges. While sLND has revolutionized nodal staging, Geißen’s study revealed that the magnetic activity of a sentinel lymph node (SLN) does not necessarily correlate with the presence of metastasis (Geißen et al., 2019). Furthermore, even in high-detectability trials like SentiMag Pro II, a single instance of in vivo missed detection occurred (sensitivity reduced to 94.4%), indicating the technique is not infallible (Winter et al., 2019). Future optimization may involve combining preoperative localization with more specific molecular imaging probes (e.g., PSMA PET/CT) or conjugating probes targeting biomarkers of nodal micrometastasis (e.g., cytokeratin) onto SPIONs for more precise “magnetic-biological” dual-targeting detection. Although PSMA-targeting probes are efficient, inherent tumor spatiotemporal heterogeneity (e.g., absent or low PSMA expression in some lesions) and tumor microenvironment (TME) barriers (e.g., interstitial hypertension, abnormal vasculature) remain key underlying risks for targeting failure and insufficient drug delivery (Taylor et al., 2011; Zhu et al., 2015; Sillerud, 2018; Yu et al., 2011; Ünak et al., 2023; Sillerud, 2016; Abdolahi et al., 2013; Zhou et al., 2022). This necessitates the development of smarter responsive nanocarriers (e.g., SPIONs sensitive to TME pH, enzymes, or redox state) or combinatorial targeting strategies (e.g., targeting both PSMA and cancer-associated fibroblasts - CAFs).

For BCa, nanomedicines like Pt-Fe-PNs must effectively overcome the bladder glycosaminoglycan (GAG) layer, a natural physiological barrier, to achieve uniform distribution and efficient penetration into the bladder wall (Huang et al., 2012). While Bai’s coaxial magnetic field system showed efficacy in small animal models, its effective penetration depth, manipulation uniformity, and targeting efficiency for deep-seated tumors in large organs like the human bladder require rigorous validation and optimization in larger animal models (e.g., pigs) (Bai et al., 2024). Additionally, the periodic filling and emptying of the bladder challenge drug residence time, necessitating nanocarriers with stronger mucosal adhesion or intelligent retention properties responsive to bladder filling status.

Common challenges are broader and more profound. First, despite employing encapsulation strategies like casein coating to enhance biocompatibility, the long-term stability of the SPIONs core in physiological environments, its degradation kinetics, as well as the metabolism and potential accumulation of iron ions, still require systematic evaluation. Dose-dependent studies in large animals are needed to define safety thresholds, as iron accumulation in organs like the liver and spleen can induce oxidative stress via Fenton reactions, posing risks of lipid peroxidation and fibrosis (Esmaili et al., 2021). Regulatory frameworks (e.g., FDA, EMA) for novel SPION-based theranostics are evolving, and no such platform has yet gained full approval for urological cancers. Known adverse events for earlier, simpler injectable iron oxide formulations (e.g., ferumoxides) included back pain, hypotension, and anaphylactoid reactions, underscoring the need for rigorous safety profiling of new, more complex SPION designs.

Second, the spatiotemporal specificity of magnetic actuation exists; cellular responses to external mechanical stimuli constitute a complex process. This response depends not only on the magnitude of the force, but also on the loading rate and the frequency of the applied force. Simultaneously, the temporal scale of the externally applied force needs to match the intrinsic timescale of the targeted intracellular signaling processes to achieve the desired mechanical control over biological phenomena. In fact, it is speculated that cellular responses to physical stimuli may be as complex as their biochemical and genetic signaling pathways.

Furthermore, excessive accumulation of iron ions may induce oxidative stress via the Fenton reaction, leading to risks such as lipid peroxidation damage or fibrosis in organs like the liver and spleen (Esmaili et al., 2021). Longer-term animal toxicological studies and more sensitive methods for tracking biodistribution and metabolism (e.g., isotopic labeling) are required. Thirdly, the synthesis of structurally complex nano-systems such as J591-DSPE-SIPPs, PLGA-SPIONs, and biomimetic exosome composites often involves multiple steps, demanding extremely high purity of raw materials, stringent reaction conditions, and rigorous purification methods (Gao et al., 2012; Abdolahi et al., 2013). Achieving high batch-to-batch uniformity (in size, shape, drug loading, and surface modification density) is a prerequisite for ensuring their safety and efficacy. This uniformity is also the current key bottleneck limiting large-scale production, cost reduction, and ultimately, widespread clinical adoption.

Establishing stringent, standardized quality control criteria and regulatory frameworks is crucial. Additionally, the efficacy of passive targeting (e.g., the EPR effect) in human tumors is controversial and exhibits significant inter-individual variability. Counter-examples and neutral findings are important to consider; for instance, the EPR effect is often less pronounced in human tumors than in rodent models, and the formation of a protein corona in vivo can mask targeting ligands, reducing binding efficiency by up to 60% in some reported cases, highlighting a significant barrier between preclinical design and clinical performance. Active targeting is limited by target expression heterogeneity, receptor saturation effects, and the formation of a complex protein corona in vivo. This corona can mask the targeting ligands, significantly reducing their binding efficiency. Moreover, navigating physiological and pathological barriers such as the blood-prostate barrier, blood-tumor barrier, and the aforementioned bladder mucus layer imposes higher design requirements on SPIONs. Furthermore, effectively integrating and quantifying the multi-modal imaging information (e.g., MRI, MPI) provided by SPIONs, and mining deep radiomics features closely related to tumor biology and treatment response for precise diagnosis and prognosis prediction, is a critical direction requiring future strengthening. Finally, transitioning from successful preclinical studies (in cell and animal models) to human clinical trials (Phase I-III) involves substantial financial investment, complex regulatory approvals (e.g., FDA, EMA), strict Good Manufacturing Practice (GMP) compliance, and meticulously designed clinical trial protocols. Demonstrating significant advantages relative to existing standard therapies (either enhanced efficacy or reduced toxicity) is the core requirement for successful translation. A comparative overview of key SPION applications for prostate and bladder cancers is provided in Table 1.

Table 1. Comparison of SPION applications in prostate cancer and bladder cancer diagnosis and treatment.

Future directions and translation pathways

Based on current research progress and existing challenges, future development of SPIONs in theranostic applications for urological tumors should focus on accelerating the clinical translation of mature technologies demonstrating significant advantages, prioritizing their advancement into larger-scale, rigorously designed clinical trials. This includes standardizing techniques like sLND, potentially drawing on staging and procedural optimization strategies proposed by the Geißen team (Geißen et al., 2019), and validating their value in multicenter studies for reducing unnecessary surgical extent (e.g., avoiding ePLND) while improving micro-metastasis detection. Simultaneously, clinical translation studies for PSMA-targeted SPION probes (e.g., J591-DSPE-SIPPs, PSMA-617-SPIONs radionuclide complexes) should be expedited to evaluate their human safety, pharmacokinetics, targeting specificity, diagnostic sensitivity, and therapeutic efficacy (Taylor et al., 2011; Yu et al., 2011; Ünak et al., 2023).

Development of intelligent stimuli-responsive nanoplatforms is crucial, inspired by designs like temperature-responsive Pt-Fe-PNs (Huang et al., 2012). Efforts should focus on creating SPION carriers responsive to specific bladder microenvironment signals such as urine pH ranges, overexpressed enzymes (e.g., MMPs) in the tumor microenvironment (TME), or reductive glutathione (GSH). Examples include designing dual pH/temperature-responsive SPIONs stable in the neutral bladder at body temperature yet rapidly releasing drugs in the acidic TME or upon localized hyperthermia for precise intravesical therapy. For systemic challenges, “smart” SPIONs sensitive to systemic TME signals (e.g., low pH, high ROS, specific enzymes) should be developed to achieve in situ drug activation or targeted release.

Deepening mechanistic research and exploring combination therapies is essential, particularly investigating unique advantages like the ferroptosis-immunity synergy induced by rPAE@SPIONs (Cai et al., 2024). This requires elucidating how SPIONs regulate iron metabolism genes (e.g., GPX4, ACSL4), influence lipid peroxidation levels, and trigger specific molecular pathways for immunogenic cell death (ICD) and M1 macrophage polarization. Such mechanistic understanding will guide effective combination strategies with existing immunotherapies (e.g., PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors) or novel immunomodulators to maximize synergistic antitumor effects and overcome the immunosuppressive TME.

Pushing the integration of multimodal technologies to build closed-loop diagnostic-treatment-monitoring systems is vital. Combining techniques like the coaxial magnetic field precise manipulation and MPI visualization developed by Bai’s team (Bai et al., 2024) with the MPI-MRI multimodal imaging guidance represented by SPIONs@EXO-Dye (Liu et al., 2024) could enable real-time monitoring of intravesical drug delivery, temperature imaging and dose control during therapies (e.g., magnetic/photo-hyperthermia), and post-treatment efficacy assessment using the same probe (e.g., monitoring tumor regression/recurrence via MRI/MPI signal changes or released reporter genes/probes). This “treating what is visualized and evaluating what is treated” closed-loop model epitomizes precision medicine.

Continuous material innovation and optimization of in vivo fate are needed, involving the development of novel functional coatings with better biocompatibility, clearer degradability, and lower immunogenicity (e.g., biomimetic membranes, specific peptides, natural polysaccharide derivatives). Optimizing SPION parameters like size, shape, surface charge, and hydrophilicity/hydrophobicity is critical to precisely control their biodistribution, blood circulation time, barrier-crossing ability, and ultimate metabolic clearance pathways, thereby minimizing long-term toxicity risks. Research into the impact of surface PEG density and conformation on “stealth” effects and avoiding MPS capture is also important.

Establishing standardization and regulatory frameworks demands close collaboration between academia, industry, and regulatory agencies to jointly develop characterization standards (physicochemical properties, stability), safety evaluation protocols (acute/chronic toxicity, immunotoxicity, reproductive toxicity, carcinogenicity), and clinical evaluation guidelines for SPIONs and their composite nanomedicines. Creating reliable reference materials and testing methods is fundamental to ensuring product quality and facilitating industrialization.

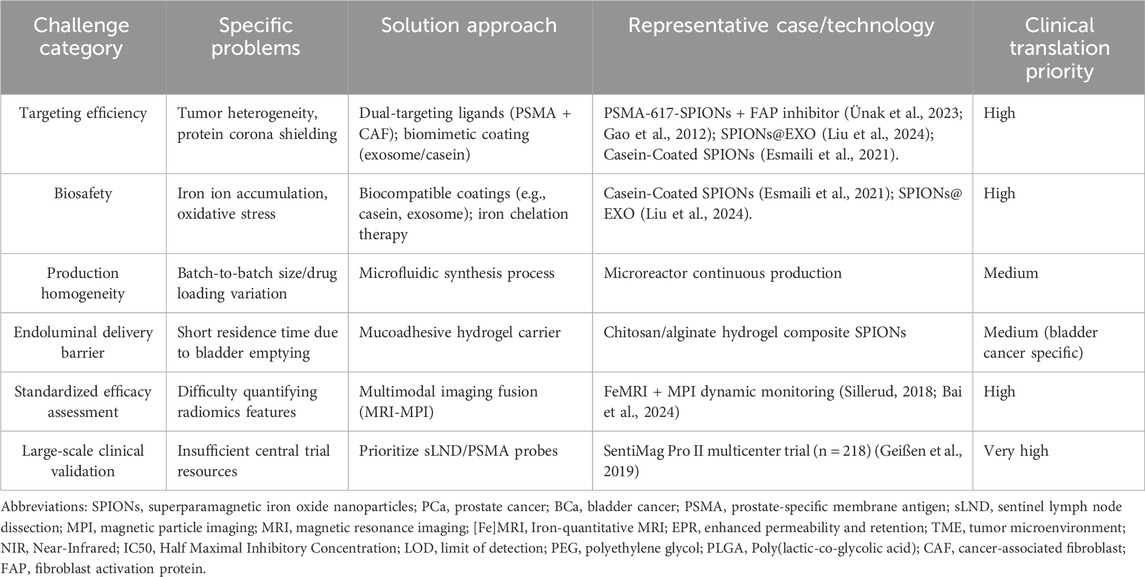

Finally, exploring the integration of personalized diagnosis and treatment should leverage SPIONs’ multifunctional platform nature. By combining patient-specific genomic, proteomic, and radiomic information, truly individualized nanotheranostic strategies can be developed. This could involve selecting targeting ligands for SPION modification based on the patient’s tumor-specific target expression profile, choosing co-loaded drug combinations according to resistance mechanisms, or adjusting parameters for physical therapies (e.g., magnetic hyperthermia dose) based on predicted treatment response. The major challenges and strategic solutions for the clinical translation of SPION technology are systematically compared in Table 2.

Conclusion

Superparamagnetic iron oxide nanoparticles (SPIONs), as a distinctive class of multifunctional nanoplatforms, demonstrate revolutionary potential in the integrated precision diagnosis and therapy of prostate and bladder cancer. Significant research progress has been made in molecular imaging diagnostics (e.g., high-sensitivity MRI/MPI, targeted imaging), minimally invasive surgical navigation (sLND), targeted drug delivery (overcoming resistance, reducing systemic toxicity), synergistic physical energy therapies (magneto-/photothermal therapy), and innovative therapeutic mechanisms (ferroptosis induction, immunomodulation). These advances provide innovative concepts and effective tools to address key bottlenecks in current urologic oncology practice. However, transitioning from laboratory successes to widespread clinical application necessitates systematically overcoming core challenges: scalable manufacturing uniformity, in-depth assessment of long-term biosafety, optimization of in vivo targeting efficiency, penetration of complex physiological/pathological barriers, and stringent clinical translation hurdles. Future research should focus on developing intelligent stimuli-responsive designs for spatiotemporal control, deepening understanding of nano-bio interactions and therapeutic mechanisms, promoting multimodal technology integration for closed-loop theranostics, and actively establishing standardization while exploring personalized integration strategies. Through multidisciplinary collaboration and sustained innovation, SPION technology holds the promise to reshape urologic oncology paradigms, ultimately achieving the overarching goals of improving patient survival, enhancing quality of life, and alleviating societal healthcare burdens.

Author contributions

DL: Writing – original draft. WW: Writing – review and editing. HL: Writing – review and editing. KL: Writing – original draft, Writing – review and editing.

Funding

The authors declare that no financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The authors declare that no Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Abdolahi, M., Shahbazi-Gahrouei, D., Laurent, S., Sermeus, C., Firozian, F., Allen, B. J., et al. (2013). Synthesis and in vitro evaluation of MR molecular imaging probes using J591 mAb-conjugated SPIONs for specific detection of prostate cancer. Contrast Media Mol. Imaging 8 (2), 175–184. doi:10.1002/cmmi.1514

Ahmed, H. U., El-Shater Bosaily, A., Brown, L. C., Gabe, R., Kaplan, R., Parmar, M. K., et al. (2017). Diagnostic accuracy of multi-parametric MRI and TRUS biopsy in prostate cancer (PROMIS): a paired validating confirmatory study. Lancet 389 (10071), 815–822. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(16)32401-1

Akhtar, N., Mohammed, H. A., Yusuf, M., Al-Subaiyel, A., Sulaiman, G. M., and Khan, R. A. (2022). SPIONs conjugate supported anticancer drug doxorubicin's delivery: current status, challenges, and prospects. Nanomaterials (Basel) 12 (20), 3686. doi:10.3390/nano12203686

Ali, A., Shah, T., Ullah, R., Zhou, P., Guo, M., Ovais, M., et al. (2021). Review on recent progress in magnetic nanoparticles: synthesis, characterization, and diverse applications. Front. Chem. 9, 629054. doi:10.3389/fchem.2021.629054

Alifrangis, C., McGovern, U., Freeman, A., Powles, T., and Linch, M. (2019). Molecular and histopathology directed therapy for advanced bladder cancer. Nat. Rev. Urol. 16 (8), 465–483. doi:10.1038/s41585-019-0208-0

Alvarez, M. M., Aizenberg, J., Analoui, M., Andrews, A. M., Bisker, G., Boyden, E. S., et al. (2017). Emerging trends in micro- and nanoscale technologies in medicine: from basic discoveries to translation. ACS Nano 11 (6), 5195–5214. doi:10.1021/acsnano.7b01493

Andriole, G. L., Crawford, E. D., Grubb, R. L., Buys, S. S., Chia, D., Church, T. R., et al. (2009). Mortality results from a randomized prostate-cancer screening trial. N. Engl. J. Med. 360 (13), 1310–1319. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa0810696

Antoni, S., Ferlay, J., Soerjomataram, I., Znaor, A., Jemal, A., and Bray, F. (2017). Bladder cancer incidence and mortality: a global overview and recent trends. Eur. Urol. 71 (1), 96–108. doi:10.1016/j.eururo.2016.06.010

Bai, S., Zhang, X. D., Zou, Y. Q., Lin, Y. X., Liu, Z. Y., Li, K. W., et al. (2024). Development of high-efficiency superparamagnetic drug delivery system with MPI imaging capability. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 12, 1382085. doi:10.3389/fbioe.2024.1382085

Bakhtiary, Z., Saei, A. A., Hajipour, M. J., Raoufi, M., Vermesh, O., and Mahmoudi, M. (2016). Targeted superparamagnetic iron oxide nanoparticles for early detection of cancer: possibilities and challenges. Nanomedicine 12 (2), 287–307. doi:10.1016/j.nano.2015.10.019

Cai, X., Ruan, L., Wang, D., Zhang, J., Tang, J., Guo, C., et al. (2024). Boosting chemotherapy of bladder cancer cells by ferroptosis using intelligent magnetic targeting nanoparticles. Colloids Surf. B Biointerfaces 234, 113664. doi:10.1016/j.colsurfb.2023.113664

Catto, J. W. F., Khetrapal, P., Ricciardi, F., Ambler, G., Williams, N. R., Al-Hammouri, T., et al. (2022). Effect of robot-assisted radical cystectomy with intracorporeal urinary diversion vs open radical cystectomy on 90-Day morbidity and mortality among patients with bladder cancer: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA 327 (21), 2092–2103. doi:10.1001/jama.2022.7393

Connell, J. J., Patrick, P. S., Yu, Y., Lythgoe, M. F., and Kalber, T. L. (2015). Advanced cell therapies: targeting, tracking and actuation of cells with magnetic particles. Regen. Med. 10 (6), 757–772. doi:10.2217/rme.15.36

Doğan, Y., Öziç, C., Ertaş, E., Baran, A., Rosic, G., Selakovic, D., et al. (2024). Activated carbon-coated iron oxide magnetic nanocomposite (IONPs@CtAC) loaded with morin hydrate for drug-delivery applications. Front. Chem. 12, 1477724. doi:10.3389/fchem.2024.1477724

Doğan, S., Baran, A., Baran, M. F., Eftekhari, A., Khalilov, R., Aliyev, E., et al. (2025). Silver nanoparticles for anticancer and antibacterial therapy: a biogenic and easy production strategy. ChemistrySelect 10 (3), e202404453. doi:10.1002/slct.202404453

Esmaili, M., Dezhampanah, H., and Hadavi, M. (2021). Surface modification of super paramagnetic iron oxide nanoparticles via milk casein for potential use in biomedical areas. J. Biomol. Struct. Dyn. 39 (3), 977–987. doi:10.1080/07391102.2020.1722751

Evans, A. J. (2018). Treatment effects in prostate cancer. Mod. Pathol. 31 (S1), S110–S121. doi:10.1038/modpathol.2017.158

Evcil, M., Kurt, B., Baran, A., Mouhoub, A., and Karakaplan, M. (2025). Development, characterization and application of chitosan-based formulation incorporating Crataegus orientalis extract for food conservation. Adv. Biol. Earth Sci. 10, 208–225. doi:10.62476/abes10-208

Ferreira-Filho, V. C., Morais, B., Vieira, B. J. C., Waerenborgh, J. C., Carmezim, M. J., Tóth, C. N., et al. (2024). Influence of SPION surface coating on magnetic properties and Theranostic profile. Molecules 29 (8), 1824. doi:10.3390/molecules29081824

Galsky, M. D., Stensland, K. D., Moshier, E., Sfakianos, J. P., McBride, R. B., Tsao, C. K., et al. (2016). Effectiveness of adjuvant chemotherapy for locally advanced bladder cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 34 (8), 825–832. doi:10.1200/JCO.2015.64.1076

Gamat, M., and McNeel, D. G. (2017). Androgen deprivation and immunotherapy for the treatment of prostate cancer. Endocr. Relat. Cancer 24 (12), T297–t310. doi:10.1530/ERC-17-0145

Gandhi, N., Krishna, S., Booth, C. M., Breau, R. H., Flood, T. A., Morgan, S. C., et al. (2018). Diagnostic accuracy of magnetic resonance imaging for tumour staging of bladder cancer: systematic review and meta-analysis. BJU Int. 122 (5), 744–753. doi:10.1111/bju.14366

Gao, X., Luo, Y., Wang, Y., Pang, J., Liao, C., Lu, H., et al. (2012). Prostate stem cell antigen-targeted nanoparticles with dual functional properties: in vivo imaging and cancer chemotherapy. Int. J. Nanomedicine 7, 4037–4051. doi:10.2147/IJN.S32804

Gareev, l., Pavlov, V., Eyvazova, K., Mashkin, A., Iessa Obeid, A. A., and Yang, L. (2025). Harnessing adrenergic receptor pathways in gliomas: from tumor biology to targeted therapies. Adv. Biol. Earth Sci. 10 (2), 245–261. doi:10.62476/abes10-245

Geißen, W., Engels, S., Aust, P., Schiffmann, J., Gerullis, H., Wawroschek, F., et al. (2019). Diagnostic accuracy of magnetometer-guided sentinel lymphadenectomy after intraprostatic injection of superparamagnetic iron oxide nanoparticles in Intermediate- and high-risk prostate cancer using the magnetic activity of sentinel nodes. Front. Pharmacol. 10, 1123. doi:10.3389/fphar.2019.01123

Gianchandani, Y., and Meng, E. (2012). Emerging micro- and nanotechnologies at the interface of engineering, science, and medicine for the development of novel drug delivery devices and systems. (preface). Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 64 (14), 1545–1546. doi:10.1016/j.addr.2012.09.001

Gopalakrishna, A., Longo, T. A., Fantony, J. J., Owusu, R., Foo, W. C., Dash, R., et al. (2016). The diagnostic accuracy of urine-based tests for bladder cancer varies greatly by patient. BMC Urol. 16 (1), 30. doi:10.1186/s12894-016-0147-5

Grimm, M. O., van der Heijden, A. G., Colombel, M., Muilwijk, T., Martínez-Piñeiro, L., Babjuk, M. M., et al. (2020). Treatment of high-grade non-muscle-invasive bladder carcinoma by standard number and dose of BCG instillations versus reduced number and standard dose of BCG instillations: results of the European Association of Urology Research Foundation randomised phase III clinical trial NIMBUS. Eur. Urol. 78 (5), 690–698. doi:10.1016/j.eururo.2020.04.066

He, M. H., Chen, L., Zheng, T., Tu, Y., He, Q., Fu, H. L., et al. (2018). Potential applications of nanotechnology in urological cancer. Front. Pharmacol. 9, 745. doi:10.3389/fphar.2018.00745

Huang, C., Neoh, K. G., Xu, L., Kang, E. T., and Chiong, E. (2012). Polymeric nanoparticles with encapsulated superparamagnetic iron oxide and conjugated cisplatin for potential bladder cancer therapy. Biomacromolecules 13 (8), 2513–2520. doi:10.1021/bm300739w

Jain, P., Kathuria, H., and Momin, M. (2021). Clinical therapies and nano drug delivery systems for urinary bladder cancer. Pharmacol. Ther. 226, 107871. doi:10.1016/j.pharmthera.2021.107871

Kara, G., and Ozpolat, B. (2024). SPIONs: superparamagnetic iron oxide-based nanoparticles for the delivery of microRNAi-therapeutics in cancer. Biomed. Microdevices 26 (1), 16. doi:10.1007/s10544-024-00698-y

Liu, S., Shang, W., Song, J., Li, Q., and Wang, L. (2024). Integration of photomagnetic bimodal imaging to monitor an autogenous exosome loaded platform: unveiling strong targeted retention effects for guiding the photothermal and magnetothermal therapy in a mouse prostate cancer model. J. Nanobiotechnology 22 (1), 421. doi:10.1186/s12951-024-02421-8

Lou, K., Feng, S., Zhang, G., Zou, J., and Zou, X. (2022). Prevention and treatment of side effects of immunotherapy for bladder cancer. Front. Oncol. 12, 879391. doi:10.3389/fonc.2022.879391

Mitra, A. P., Cai, J., Miranda, G., Bhanvadia, S., Quinn, D. I., Schuckman, A. K., et al. (2022). Management trends and outcomes of patients undergoing radical cystectomy for urothelial carcinoma of the bladder: evolution of the University of Southern California experience over 3,347 cases. J. Urol. 207 (2), 302–313. doi:10.1097/JU.0000000000002242

Muthiah, M., Park, I. K., and Cho, C. S. (2013). Surface modification of iron oxide nanoparticles by biocompatible polymers for tissue imaging and targeting. Biotechnol. Adv. 31 (8), 1224–1236. doi:10.1016/j.biotechadv.2013.03.005

Negoita, S., Feuer, E. J., Mariotto, A., Cronin, K. A., Petkov, V. I., Hussey, S. K., et al. (2018). Annual report to the nation on the status of cancer, part II: recent changes in prostate cancer trends and disease characteristics. Cancer 124 (13), 2801–2814. doi:10.1002/cncr.31549

Onbasli, K., Erkısa, M., Demirci, G., Muti, A., Ulukaya, E., Sennaroglu, A., et al. (2022). The improved killing of both androgen-dependent and independent prostate cancer cells by etoposide loaded SPIONs coupled with NIR irradiation. Biomater. Sci. 10 (14), 3951–3962. doi:10.1039/d2bm00107a

Parker, C., Castro, E., Fizazi, K., Heidenreich, A., Ost, P., Procopio, G., et al. (2020). Prostate cancer: ESMO clinical practice guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann. Oncol. 31 (9), 1119–1134. doi:10.1016/j.annonc.2020.06.011

Pawar, P., and Prabhu, A. (2025). Smart SPIONs for multimodal cancer theranostics: a review. Mol. Pharm. 22 (5), 2372–2391. doi:10.1021/acs.molpharmaceut.5c00411

Ritch, C. R., Velasquez, M. C., Kwon, D., Becerra, M. F., Soodana-Prakash, N., Atluri, V. S., et al. (2020). Use and validation of the AUA/SUO risk grouping for nonmuscle invasive bladder cancer in a contemporary cohort. J. Urol. 203 (3), 505–511. doi:10.1097/JU.0000000000000593

Samrot, A. V., Sahithya, C. S., Selvarani, J., Purayil, S. K., and Ponnaiah, P. (2021). A review on synthesis, characterization and potential biological applications of superparamagnetic iron oxide nanoparticles. Curr. Res. Green Sustain. Chem. 4, 100042. doi:10.1016/j.crgsc.2021.100042

Sanli, O., Dobruch, J., Knowles, M. A., Burger, M., Alemozaffar, M., Nielsen, M. E., et al. (2017). Bladder cancer. Nat. Rev. Dis. Prim. 3, 17022. doi:10.1038/nrdp.2017.22

Schröder, F. H., Hugosson, J., Roobol, M. J., Tammela, T. L., Ciatto, S., Nelen, V., et al. (2012). Prostate-cancer mortality at 11 years of follow-up. N. Engl. J. Med. 366 (11), 981–990. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1113135

Sekhoacha, M., Riet, K., Motloung, P., Gumenku, L., Adegoke, A., and Mashele, S. (2022). Prostate cancer review: genetics, diagnosis, treatment options, and alternative approaches. Molecules 27 (17), 5730. doi:10.3390/molecules27175730

Siegel, R. L., Miller, K. D., Fuchs, H. E., and Jemal, A. (2022). Cancer statistics, 2022. CA Cancer J. Clin. 72 (1), 7–33. doi:10.3322/caac.21708

Sillerud, L. O. (2016). Quantitative [Fe]MRI of PSMA-targeted SPIONs specifically discriminates among prostate tumor cell types based on their PSMA expression levels. Int. J. Nanomedicine 11, 357–371. doi:10.2147/IJN.S93409

Sillerud, L. O. (2018). Quantitative [Fe]MRI determination of the dynamics of PSMA-targeted SPIONs discriminates among prostate tumor xenografts based on their PSMA expression. J. Magn. Reson Imaging 48 (2), 469–481. doi:10.1002/jmri.25935

Solar, P., González, G., Vilos, C., Herrera, N., Juica, N., Moreno, M., et al. (2015). Multifunctional polymeric nanoparticles doubly loaded with SPION and ceftiofur retain their physical and biological properties. J. Nanobiotechnology 13, 14. doi:10.1186/s12951-015-0077-5

Song, W., Anselmo, A. C., and Huang, L. (2019). Nanotechnology intervention of the microbiome for cancer therapy. Nat. Nanotechnol. 14 (12), 1093–1103. doi:10.1038/s41565-019-0589-5

Sylvester, R. J., van der Meijden, A. P., Oosterlinck, W., Witjes, J. A., Bouffioux, C., Denis, L., et al. (2006). Predicting recurrence and progression in individual patients with stage Ta T1 bladder cancer using EORTC risk tables: a combined analysis of 2596 patients from seven EORTC trials. Eur. Urol. 49 (3), 466–477. doi:10.1016/j.eururo.2005.12.031

Taylor, R. M., Huber, D. L., Monson, T. C., Ali, A. M., Bisoffi, M., and Sillerud, L. O. (2011). Multifunctional iron platinum stealth immunomicelles: targeted detection of human prostate cancer cells using both fluorescence and magnetic resonance imaging. J. Nanopart. Res. 13 (10), 4717–4729. doi:10.1007/s11051-011-0439-3

Teo, M. Y., Rathkopf, D. E., and Kantoff, P. (2019). Treatment of advanced prostate cancer. Annu. Rev. Med. 70, 479–499. doi:10.1146/annurev-med-051517-011947

Tilki, D., van den Bergh, R. C. N., Briers, E., Van den Broeck, T., Brunckhorst, O., Darraugh, J., et al. (2024). EAU-EANM-ESTRO-ESUR-ISUP-SIOG guidelines on prostate cancer. Part II-2024 update: treatment of relapsing and metastatic prostate cancer. Eur. Urol. 86 (2), 164–182. doi:10.1016/j.eururo.2024.04.010

Uhlirova, D., Stankova, M., Docekalova, M., Hosnedlova, B., Kepinska, M., Ruttkay-Nedecky, B., et al. (2018). A rapid method for the detection of sarcosine using SPIONs/Au/CS/SOX/NPs for prostate cancer sensing. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 19 (12), 3722. doi:10.3390/ijms19123722

Ünak, P., Yasakçı, V., Tutun, E., Karatay, K. B., Walczak, R., Wawrowicz, K., et al. (2023). Multimodal radiobioconjugates of magnetic nanoparticles labeled with (44)Sc and (47)Sc for Theranostic application. Pharmaceutics 15 (3), 850. doi:10.3390/pharmaceutics15030850

Vizcarra-Ramos, S., Molina-Pineda, A., Gutiérrez-Ortega, A., Herrera-Rodríguez, S. E., Aguilar-Lemarroy, A., Jave-Suárez, L. F., et al. (2024). Synergistic strategies in prostate cancer therapy: electrochemotherapy and electromagnetic hyperthermia. Pharmaceutics 16 (9), 1109. doi:10.3390/pharmaceutics16091109

von der Maase, H., Sengelov, L., Roberts, J. T., Ricci, S., Dogliotti, L., Oliver, T., et al. (2005). Long-term survival results of a randomized trial comparing gemcitabine plus cisplatin, with methotrexate, vinblastine, doxorubicin, plus cisplatin in patients with bladder cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 23 (21), 4602–4608. doi:10.1200/JCO.2005.07.757

Wasim, S., Lee, S. Y., and Kim, J. (2022). Complexities of prostate cancer. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 23 (22), 14257. doi:10.3390/ijms232214257

Winter, A., Engels, S., Reinhardt, L., Wasylow, C., Gerullis, H., and Wawroschek, F. (2017). Magnetic marking and intraoperative detection of primary draining lymph nodes in high-risk prostate cancer using superparamagnetic iron oxide nanoparticles: additional diagnostic value. Molecules 22 (12), 2192. doi:10.3390/molecules22122192

Winter, A., Engels, S., Goos, P., Süykers, M. C., Gudenkauf, S., Henke, R. P., et al. (2019). Accuracy of magnetometer-guided sentinel lymphadenectomy after intraprostatic injection of superparamagnetic iron oxide nanoparticles in prostate cancer: the SentiMag pro II study. Cancers (Basel) 12 (1), 32. doi:10.3390/cancers12010032

Yafi, F. A., Brimo, F., Steinberg, J., Aprikian, A. G., Tanguay, S., and Kassouf, W. (2015). Prospective analysis of sensitivity and specificity of urinary cytology and other urinary biomarkers for bladder cancer. Urol. Oncol. 33 (2), 66.e25–66.e31. doi:10.1016/j.urolonc.2014.10.015

Yan, L., Chen, Y., Zhang, S., Zhu, C., Xiao, S., Xia, H., et al. (2024). Reconstruction of TNF-α with specific isoelectric point released from SPIONs basing on variable charge to enhance pH-sensitive controlled-release. Nanomedicine 60, 102758. doi:10.1016/j.nano.2024.102758

Yeh, C. Y., Hsiao, J. K., Wang, Y. P., Lan, C. H., and Wu, H. C. (2016). Peptide-conjugated nanoparticles for targeted imaging and therapy of prostate cancer. Biomaterials 99, 1–15. doi:10.1016/j.biomaterials.2016.05.015

Yoffe, S., Leshuk, T., Everett, P., and Gu, F. (2013). Superparamagnetic iron oxide nanoparticles (SPIONs): synthesis and surface modification techniques for use with MRI and other biomedical applications. Curr. Pharm. Des. 19 (3), 493–509. doi:10.2174/138161213804805211

Yu, M. K., Kim, D., Lee, I. H., So, J. S., Jeong, Y. Y., and Jon, S. (2011). Image-guided prostate cancer therapy using aptamer-functionalized thermally cross-linked superparamagnetic iron oxide nanoparticles. Small 7 (15), 2241–2249. doi:10.1002/smll.201100472

Zhi, D., Yang, T., Yang, J., Fu, S., and Zhang, S. (2020). Targeting strategies for superparamagnetic iron oxide nanoparticles in cancer therapy. Acta Biomater. 102, 13–34. doi:10.1016/j.actbio.2019.11.027

Zhou, W., Huang, J., Xiao, Q., Hu, S., Li, S., Zheng, J., et al. (2022). Glu-Urea-Lys scaffold functionalized superparamagnetic iron oxide nanoparticles targeting PSMA for in vivo molecular MRI of prostate cancer. Pharmaceutics 14 (10), 2051. doi:10.3390/pharmaceutics14102051

Keywords: superparamagnetic iron oxide nanoparticles (SPIONs), prostate cancer, bladder cancer, magnetic nanoparticles, cancer nanomedicine, theranostics

Citation: Li D, Wu W, Liu H and Lou K (2025) SPIONs as theranostic agents in bladder and prostate cancer: integrating diagnosis and therapy. Front. Nanotechnol. 7:1660979. doi: 10.3389/fnano.2025.1660979

Received: 17 September 2025; Accepted: 24 November 2025;

Published: 04 December 2025.

Edited by:

Hang Ta, Griffith University, AustraliaReviewed by:

Parviz Vahedi, Maragheh University of Medical Sciences, IranPrakash Daniel Nallathamby, University of Notre Dame, United States

Copyright © 2025 Li, Wu, Liu and Lou. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Kecheng Lou, MTgzMjkwMzc2MTVAMTYzLmNvbQ==

Dezheng Li1

Dezheng Li1 Haicheng Liu

Haicheng Liu Kecheng Lou

Kecheng Lou