- 1Department of Plant Biotechnology, Institute of Agricultural Sciences, Banaras Hindu University, Varanasi, India

- 2Department of Veterinary Physiology and Biochemistry, Faculty of Veterinary and Animal Sciences, Institute of Agricultural Sciences, Banaras Hindu University, Varanasi, India

The rapid advancement and integration of engineered nanomaterials (ENMs) into consumer products, industrial processes, biomedical applications, and environmental technologies have revolutionized multiple sectors. However, their increased production and environmental release raise critical concerns about unintended interactions with microbial ecosystems. ENMs, including metal-based nanoparticles (silver, titanium dioxide, zinc oxide) and carbon nanomaterials (graphene, carbon nanotubes), possess unique physicochemical properties such as high surface area-to-volume ratios, tunable reactivity, and antimicrobial potential that allow them to interact directly with microbial cells or indirectly influence their habitats. This review critically examines the emerging evidence on ENM–microbiome interactions across human, aquatic, terrestrial, and agricultural systems. In human-associated microbiomes, especially the gut, ENMs can induce dysbiosis by disrupting microbial diversity, altering metabolite production (e.g., short-chain fatty acids), and impairing gut barrier integrity, contributing to inflammation and metabolic disorders. In environmental settings, ENMs influence key microbial functions like nitrogen fixation, organic matter decomposition, and biogeochemical cycling, potentially undermining ecosystem stability and agricultural productivity. Moreover, ENMs are increasingly implicated in accelerating antimicrobial resistance by promoting horizontal gene transfer and enriching resistance genes in microbial communities. The review highlights methodological advances such as high-throughput sequencing, meta-omics approaches, in vitro colon simulators, and in vivo models that have enhanced the assessment of ENM-induced microbiome alterations. Despite these advances, significant gaps remain in understanding long-term and low-dose effects, dose–response relationships, and ecological thresholds. Addressing these gaps through multidisciplinary research and regulatory frameworks is essential for ensuring the safe and sustainable deployment of nanotechnologies in a microbiome-sensitive world.

1 Introduction

The emergence and widespread integration of engineered nanomaterials (ENMs) into consumer products, industrial processes, environmental technologies, and biomedical applications has revolutionized multiple sectors of modern life (Bora et al., 2022; Rocco, 2025). These nanoscale materials, typically ranging from 1 to 100 nm in size, exhibit novel physicochemical properties such as high surface area-to-volume ratio, tunable reactivity, and enhanced mechanical or optical behavior (Kumar A. Y. N. et al., 2024). Common ENMs include metal-based nanoparticles (NPs), such as silver nanoparticles (AgNPs), titanium dioxide nanoparticles (TiO2 NPs), zinc oxide nanoparticles (ZnO NPs), carbon-based nanomaterials (CNMs) like graphene, carbon nanotubes (CNTs), and composite nanostructures (Fritea et al., 2021). While these innovations have brought significant technological and economic benefits, their increasing production and environmental release have raised growing concerns about potential biological and ecological risks, especially concerning their interactions with microbial communities (Rajpal et al., 2025). Microbial ecosystems spanning human-associated microbiomes to those found in aquatic, terrestrial, and agricultural environments play fundamental roles in maintaining physiological and ecological equilibrium (Ma L. C. et al., 2023). In the human body, particularly within the gastrointestinal tract, the gut microbiota contributes to digestion, immune regulation, synthesis of essential vitamins and short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs), and defense against pathogens (See et al., 2025). Similarly, in natural environments, microbial communities regulate biogeochemical cycles, decompose organic matter, support plant growth through symbiosis, and influence soil and water quality. Any disturbance in microbial diversity, abundance, or metabolic function, termed as dysbiosis, can have cascading effects on host health and ecosystem resilience (Prasad et al., 2024; Zaman et al., 2025).

ENMs are increasingly recognized as potential disruptors of microbial homeostasis. When released into the environment through waste streams, or ingested or inhaled by humans and animals, ENMs can interact directly with microbial cells or indirectly influence their surrounding microenvironments (Ray et al., 2009; Kumar et al., 2022). Their mechanisms of action include generation or induction of reactive oxygen species (ROS), disruption of membrane integrity, interference with DNA and protein function, and modulation of microbial metabolic and signaling pathways (Kumar R. et al., 2024). These effects can lead to reduced microbial diversity, shifts in community composition, alterations in metabolite production, and perturbation of key functional processes such as nutrient cycling, energy metabolism, and host–microbe communication (Wang et al., 2017). In human systems, such alterations have been linked to inflammatory bowel diseases, metabolic disorders, immune dysregulation, and neurobehavioral conditions (Xuan et al., 2023). In environmental settings, ENMs can affect microbial-driven processes like nitrogen fixation, denitrification, and organic matter decomposition, ultimately threatening soil fertility, water quality, and ecosystem services (Hochella et al., 2019; Huang et al., 2024).

Furthermore, ENMs may play a role in accelerating antimicrobial resistance (AMR) by enhancing horizontal gene transfer, altering microbial stress responses, and promoting the persistence of resistance genes in various environmental matrices (Wang X. et al., 2024; Piergiacomo et al., 2022). This poses a dual risk: while ENMs are often employed for their antimicrobial properties, their indiscriminate or chronic use could inadvertently select for resistant strains, complicating both clinical and ecological health management (Alav and Buckner, 2024).

Given the breadth of these interactions, the current review aims to provide a comprehensive overview of the current understanding of ENM–microbiome dynamics, the effects of various NMs on the human gut microbiota, aquatic and soil microbial ecosystems, and the potential for ENMs to influence microbial resistance development. It also evaluates the methodologies used to study these effects, including high-throughput sequencing, omics technologies, and in vitro/in vivo models, while highlighting regulatory and scientific challenges in assessing long-term risks. Finally, key knowledge gaps are identified and future directions are proposed for ensuring that the deployment of nanotechnologies is conducted safely and sustainably in a microbiome-sensitive world.

2 ENMs as anthropogenic sources of environmental and human microbiome perturbation

ENMs, especially AgNPs, ZnO NPs, TiO2 NPs, etc., are now ubiquitous across consumer, medical, agricultural, and industrial applications—ranging from antimicrobial coatings and textiles to water treatment, pesticides, cosmetics, and electronics (Figure 1). AgNPs are incorporated into food packaging materials for their antimicrobial properties, helping to extend shelf life and reduce spoilage (Martirosyan and Schneider, 2014). Titanium dioxide and silica (e.g., TiO2, SiO2 NPs) are common food additives or colourants (for example, TiO2 as food colourant E171) or anticaking agents in powdered products (Villamayor et al., 2023). ENMs are also used in nano-encapsulation of bioactive compounds, improving bioavailability of vitamins or nutraceuticals, and in smart packaging systems (with sensors, diffusion barriers, or controlled antimicrobial release) (Martirosyan and Schneider, 2014). ENMs are widely used in cosmetic formulations to improve efficacy, texture, appearance, and UV protection. Common nanomaterials include nano-TiO2 and nano-zinc oxide, which serve as UV filters in sunscreens because, at the nanoscale, they offer strong UV protection while remaining transparent on skin (Pastrana et al., 2018; Catalano et al., 2021). Other ENMs include nano-silica, used to improve spreadability, reduce greasiness, act as anti-caking agents in powders and lipsticks, and enhance pigment dispersion (Ferreira et al., 2023). ENMs are increasingly integrated into drugs and medical products due to their unique physicochemical properties, such as high surface area, tunable size, and surface functionality. In drug and vaccine delivery, ENMs like liposomes, polymeric nanoparticles, and metal-based nanoparticles enhance bioavailability, facilitate targeted drug delivery and sustained release to specific tissues, and reduce systemic side effects. Applications of ENMs in medical devices, diagnostic imaging, wound dressings, antimicrobial textiles/implants, etc., are also increasing exponentially (Cai et al., 2023; Kurul et al., 2025); ENMs are increasingly applied in agriculture to enhance nutrient efficiency, promote plant growth, and control pests. Nano-fertilizers using metal or oxide NPs (e.g., ZnO, Fe3O4) and carrier platforms (e.g., nanoclay, chitosan) help minimize nutrient leaching and increase uptake (N, P, K) in crops (Yin et al., 2018). Nanopesticides formulated with ENMs offer targeted delivery, lower chemical doses, and longer persistence against pathogens (Adisa et al., 2019). Beyond these applications, ENMs find widespread use in general industrial sectors such as coatings, electronics, energy, and construction. TiO2 NPs are used in self-cleaning and UV-resistant coatings, paints, and solar panel coatings to improve durability and reduce maintenance (Moloi et al., 2021; Hussein, 2023). Graphene, CNTs, and hybrid nanocomposites enhance electrical and thermal properties in devices, lightweight materials, and structural composites (Cataldi et al., 2020). Silver, zinc oxide, and silicon dioxide ENMs are used in textiles, antimicrobial surfaces, filtration systems, and sensors, due to their unique optical, catalytic or antimicrobial functionalities (Moloi et al., 2021; Singh et al., 2023).

Figure 1. Applications of engineered nanomaterials (ENMs), exposure pathways, and associated microbiome perturbations. The schematic tree illustrates the diverse applications of ENMs across major sectors including medicine and healthcare, water purification, food and packaging, agriculture, electronics and energy, industry, textiles, and coatings and paints. Exposure through ingestion, inhalation, dermal absorption, or soil/water contamination can disrupt human and environmental microbiomes, causing functional, compositional, and resistance-related shifts.

The ongoing and widespread use of ENMs brings them into frequent contact with environmental and human microbial communities, representing emerging anthropogenic sources of microbial disruption. ENMs in food (additives, packaging, nano-encapsulation), drugs or cosmetics are ingested or absorbed, while agricultural nano-fertilizers and nanopesticides enter soil and water, exposing soil and gut microbiota (Kah, 2015; Khan et al., 2021; Yadav et al., 2023). Improperly managed industrial nano-effluents serve as significant sources of toxicants to the environment and the food chain causing microbiome perturbations (Naz et al., 2024). These perturbations are dose-dependent, often manifest first in metabolic or enzymatic function and substrate utilization before major shifts in diversity or taxonomy (Avila-Arias et al., 2023). Given the environmental persistence and bioaccumulation potential of many ENMs, understanding realistic exposure levels (in water, soil, diet), their transformation (coating, aggregation, ion release), and their functional effects on microbial communities is critical for risk assessment and regulatory oversight.

3 ENMs and human microbiome

The human gut microbiota is a complex community of trillions of microorganisms, primarily bacteria that live in the gastrointestinal tract, especially the colon. These microbes play a crucial role in maintaining human health by aiding in digestion, synthesizing essential vitamins, regulating the immune system, and protecting against harmful pathogens. The composition of the gut microbiota is influenced by various factors, including diet, antibiotics, age, and lifestyle. A balanced microbiota supports overall health, while disruptions, known as dysbiosis, have been linked to numerous conditions such as inflammatory bowel disease, obesity, diabetes, and mental health disorders (Thursby and Juge, 2017; Hou et al., 2022). ENMs, such as Ag NPs, TiO2 NPs, ZnO NPs, and CNMs are increasingly used in food additives, packaging, pharmaceuticals, and cosmetics. When ingested, either directly through food or indirectly via environmental exposure, these NMs can interact with the gut microbiota and potentially disrupt gut health. Studies have shown that certain ENMs can alter the composition and diversity of the microbial community, leading to dysbiosis, inflammation, and impaired gut barrier function (Utembe et al., 2022). For example, Ag NPs and TiO2 NPs have been associated with reduced beneficial bacteria (like Lactobacillus and Bifidobacterium) and increased pro-inflammatory species (Utembe et al., 2022; Ma Y. et al., 2023). Additionally, ENMs can affect microbial metabolism and the production of SCFAs, which are vital for maintaining intestinal health (Figure 2). While the long-term impacts on human health are still being investigated, emerging evidence suggests that chronic exposure to ENMs may contribute to gastrointestinal disorders, immune dysregulation, and metabolic disturbances by disrupting the delicate balance of the gut ecosystem (Table 1) (Tang et al., 2021; Wojciechowska et al., 2023).

Figure 2. Effects of engineered nanomaterials (ENMs) on human gut microbiota and environmental microbial communities. This schematic illustrates the multifaceted impacts of ENMs, including metal-based nanoparticles and carbon nanomaterials, on microbial ecosystems. In the human gut, ENMs disrupt microbial diversity and composition, reducing beneficial taxa, altering short-chain fatty acid (SCFA) production, and compromising gut barrier integrity, which may lead to dysbiosis, inflammation, and metabolic disorders. In environmental systems (aquatic, soil, and agricultural), ENMs interfere with microbial-mediated biogeochemical processes such as nitrogen fixation, denitrification, and organic matter decomposition, potentially impairing nutrient cycling and ecosystem resilience.

3.1 Impact of titanium dioxide nanoparticles on gut microbiota and their mechanism of interaction

TiO2 NPs appear to exert a limited effect on gut microbiota diversity; however, they tend to influence the overall abundance of gut bacteria more noticeably (Table 1). Notably, TiO2 NPs have been found to affect specific bacterial groups, including Lactobacillus, as well as members of the Firmicutes and Proteobacteria phyla, while leaving overall microbial diversity at higher taxonomic levels relatively unaffected (Lin et al., 2014; Sohm et al., 2015; Burke et al., 2015; Zhang et al., 2022; Ma Y. et al., 2023). For instance, a total of 42 bacterial species were reported to undergo significant changes upon TiO2 NPs exposure, suggesting a risk of dysbiosis (Zhang et al., 2022). These compositional shifts are accompanied by disruptions in key metabolic pathways, particularly those associated with oxidative phosphorylation and energy metabolism, which are critical for maintaining gut health (Figure 2). In vitro studies also indicated that TiO2 NPs can inhibit the growth of beneficial bacteria like Lactobacillus and Bifidobacterium, through an exposure of diets containing 0.1% TiO2 NPs for 90 days to 1 mg/kg TiO2 NP for 7 days respectively, further implicating them in adverse gut effects (Wu et al., 2023). Such microbial disturbances have been associated with health risks, including colitis and obesity (Gangadoo et al., 2021). Although some evidence suggests that TiO2 NPs might enhance probiotic diversity under certain conditions, the prevailing data highlight their potential to negatively impact gut microbial communities (Kumar A. et al., 2024). Notably, these effects appear to be dose- and duration-dependent, underscoring the need for more comprehensive research to clarify the complex interactions between TiO2 NPs and the gut microbiome.

TiO2 NPs interact with gut microbiota primarily through mechanisms that induce dysbiosis linked to various health disorders, inflammation, immune modulation, and metabolic pathway disruption (Figure 2). Studies have shown that oral exposure to TiO2 NPs leads to significant shifts in microbial composition; for instance, decreasing beneficial bacteria like Veillonella while increasing genera such as Lactobacillus gasseri, Turicibacter, Lachnospiraceae NK4A136 group, etc., thereby impairing normal gut function and metabolism (Chen et al., 2019; Yan et al., 2020; Rinninella et al., 2021; Bianchi et al., 2024). These NPs also induce ROS within the gut, causing oxidative stress and inflammation that facilitate lipopolysaccharide (LPS) leakage from Gram-negative bacteria, further exacerbating gut inflammation-a process implicated in chronic metabolic diseases like obesity and diabetes. Additionally, TiO2 NPs may directly engage with intestinal immune cells, altering the microbiota–immune system axis and perpetuating inflammatory responses (Lamas et al., 2023). Metabolically, TiO2 NP exposure disrupts critical bacterial pathways including energy metabolism, detoxification, amino acid metabolism and SCFA production, which are vital for maintaining gut barrier integrity and regulating host energy homeostasis (Utembe et al., 2022; Wu et al., 2023; Pinget et al., 2019; Yang et al., 2022). Liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS)-based untargeted metabolomics analysis demonstrated that TiO2 NPs disrupt critical metabolic pathways in gut bacteria, particularly tryptophan and arginine metabolism, which are essential for maintaining gut and host health. In vivo studies showed that mice fed a diet containing TiO2 NPs (0.1 wt% for 8 weeks) exhibited significant changes in urinary metabolites, with notable alterations in the tryptophan metabolism pathway. Furthermore, different neuroprotective metabolites such as tryptamine, N-Methyltryptamine, 6-Hydroxymelatonin, and N-Acetylserotonin, were significantly decreased in both bacterial cultures and the urine of treated mice (Wu et al., 2023). These interlinked mechanisms, i.e., microbial imbalance, oxidative-inflammation signaling, immune dysregulation, and metabolic impairment highlight how TiO2 NPs can detrimentally reshape the gut ecosystem and contribute to metabolic health disturbances.

The interactions between NPs and gastrointestinal microbiota are governed by multiple parameters, including the surface charge and physicochemical properties of both NPs and bacterial cells, the electrostatic interactions with digested food matrices, the chemical composition and bioactivity of dietary components, as well as dynamic physicochemical conditions within the gastrointestinal tract, such as pH gradients, enzymatic activity, ionic strength, and the presence of bile salts and other metabolites (Siemer et al., 2018; Baranowska-Wójcik, 2021). Analysis of the impact of engineered NPs on both commensal and pathogenic microorganisms in a gastrointestinal study showed that food-grade and model NPs readily form stable complexes with both probiotic and pathogenic bacteria under simulated gastrointestinal conditions. NP size emerged as the key determinant of NP–bacteria interactions, with smaller negatively charged NPs binding more efficiently to bacterial surfaces than larger positively charged ones, regardless of charge similarity. Additionally, low gastric pH enhanced complexation, while polymer coatings on NPs inhibited binding via steric repulsion, highlighting factors influencing NP–microbe interactions in the GI tract (Siemer et al., 2018). Toxicity analysis of five TiO2 NPs (10–50 nm) with different crystal phases using Escherichia coli revealed that antibacterial activity decreased with larger particle size and higher rutile content. Smaller anatase TiO2 NPs induced greater ROS production, membrane damage, and internalization, while higher pH and ionic strength reduced their antibacterial efficacy (Lin et al., 2014). Further, it has been reported that oral TiO2 NPs aggravated acute colitis by activating the NLRP3 inflammasome, leading to IL-1β and IL-18 release, ROS generation, and increased intestinal permeability. TiO2 crystals accumulated in the spleen of treated mice, and elevated titanium levels were detected in UC patients with active disease (Ruiz et al., 2017). These findings suggest potential harm of TiO2 NPs in individuals with compromised gut barrier and pre-existing inflammation, like IBD.

3.2 AgNPs and gut microbiota: exploring their impact and interaction mechanisms

The impacts of AgNPs on the human gut microbiota are complex and multifaceted, involving direct antimicrobial activity, disruption of microbial community structure, modulation of host metabolism, and impairment of gut barrier integrity (Table 1). AgNPs exert direct antimicrobial effects by interacting with bacterial cells, where they damage cell membranes, interfere with metabolic pathways, and inhibit DNA replication, ultimately leading to bacterial death (Bruna et al., 2021; Rodrigues et al., 2024). A key mechanism underlying these effects is the induction of oxidative stress within gut bacteria, characterized by increased nitric oxide production, lipid peroxidation, and DNA damage, all of which can destabilize the gut microbial ecosystem and promote dysbiosis (Li et al., 2019; Adeyemi et al., 2020; Manuja et al., 2021).

Such antimicrobial actions lead to significant alterations in the structural composition of the gut microbiota, with notable shifts in community diversity and abundance (Figure 2). AgNPs have been shown to selectively inhibit the growth of certain Gram-negative bacteria, reducing the prevalence of beneficial taxa like Bacteroides while favoring opportunistic and potentially pathogenic groups such as Enterococcus (More et al., 2023; Xie et al., 2023). These compositional changes result in a measurable loss of microbial diversity, particularly after short-term AgNP exposure (Bi et al., 2020; Wang X. et al., 2023). This loss of diversity has been directly associated with dysbiosis and adverse health outcomes, including gastrointestinal disorders (Ghebretatios et al., 2021). Interestingly, some studies suggest that microbial diversity may partially recover over extended exposure periods; however, metabolic perturbations often persist, indicating enduring effects on host physiology (Wang X. et al., 2023). Structural alterations are particularly prominent among microorganisms involved in energy, amino acid, and lipid metabolism (Wang, X. et al., 2022). Notably, in studies where mice received oral gavage of AgNPs once daily for 120 consecutive days, there were significant alterations in gut microbial functions associated with amino acid, purine, pyrimidine, lipid, and energy metabolism, as well as downstream effects on liver metabolic pathways (Wang, X. et al., 2022). Further, AgNPs significantly impact bacterial adhesion to the intestinal epithelium, a critical step in colonization and biofilm development. AgNPs exert a dual role in adhesion dynamics—primarily inhibiting bacterial attachment and biofilm formation, yet potentially triggering compensatory virulent behaviors under certain conditions. These adhesion-disrupting effects are crucial for their application in gut environments, where they may influence both pathogen colonization and commensal biofilm stability (Saeki et al., 2021; Afrasiabi and Partoazar, 2024; González-Fernández et al., 2025).

Moreover, AgNPs can compromise the integrity of the intestinal barrier, which serves as a critical defense against the translocation of bacteria and toxins from the gut lumen into the systemic circulation (Figure 2). Disruption of this barrier has been linked to increased gut permeability, low-grade inflammation, and the potential development of systemic health issues (Shayo et al., 2024; Li W. et al., 2024). While AgNPs hold promise in controlling pathogenic bacteria, their ability to perturb microbial balance and host metabolic processes raises significant concerns regarding their widespread use in consumer products and medical applications. The inherent resilience of the gut microbiome may offer some degree of recovery from AgNP-induced dysbiosis; however, the persistence of metabolic and barrier-related disruptions highlights the need for cautious evaluation of AgNP exposure and its long-term implications for gut and overall health.

The biological impact of AgNPs on gut microbiota is strongly shaped by particle size, shape, surface charge, concentration, surface coating, and the existing microbial community. Smaller AgNPs (<10 nm) exhibit heightened toxicity due to their larger surface-area-to-volume ratios, accelerated release of Ag+ ions, and greater ROS generation, which promotes oxidative stress in microbial cells (Zhang L. et al., 2018; Menichetti et al., 2023; Dinç, 2025; Sati et al., 2025). NP shape also affects efficacy; spherical, triangular, hexagonal, cubic or rod-shaped forms of AgNPs displayed variable antimicrobial activity. However, the anti-microbial potential based upon morphological attributes varied contrastingly according to the variable experimental conditions (Van Dong et al., 2012; Alshareef et al., 2017; Hanan et al., 2018; Vanlalveni et al., 2024). Therefore, a generalization may draw false narrative. Surface charge modulates interactions with bacteria: positively charged AgNPs strongly adhere to negatively charged bacterial membranes via electrostatic attraction, increasing membrane disruption and antimicrobial potency, whereas negatively charged or neutral coatings can reduce this effect (El Badawy et al., 2011; Alshareef et al., 2017). The concentration of AgNPs is critical—higher doses induce more pronounced disturbances in microbial diversity, metabolic function, and intestinal inflammation, while low or sub-threshold levels may have minimal or reversible effects; for instance, a dose-dependent alteration in gut microbiota α- and β-diversity has been reported in mice orally exposed for 28 days to food pellets supplemented with increasing doses of AgNPs (0, 46, 460, or 4,600 ppb). They also observed that higher doses shifted the phyla balance (Firmicutes vs. Bacteroidetes), but low doses had lesser or no overt toxicity (van Den Brule et al., 2015). Similarly, oral exposure to AgNPs (0, 1, 5, 10, 25, 50 mg/kg bw/day for 4 weeks) induced dose-dependent toxicity in mice, evidenced by body weight suppression and reduced intestinal dendritic cell numbers, confirming that both systemic and local immune effects scale with dose (Ren et al., 2023). However, contrasting results have also been reported documenting no changes in the Firmicutes/Bacteroidetes ratio in gut microbiota of rats and mice exposed to AgNPs at dose levels of 9 mg/kg bw/day and 10 mg/kg bw/day, respectively (Wilding et al., 2016; Hadrup et al., 2012). The duration of NP exposure may also have significant effects. In mice, administration of AgNPs and Ag nanowires (0.5 and 2.5 mg/kg) for 14 days reduced gut microbial diversity and altered community structure. After 28 days, partial recovery of the microbiota was observed, although metabolic disturbances, particularly in gut metabolites, persisted (Wang X. et al., 2023). Surface coatings, such as PEG, PVP, or chitosan, are routinely used to reduce toxicity by limiting dissolution and aggregation; PEG-coated AgNPs, for instance, exhibit reduced cytotoxicity and attenuated gut microbiota disruption (Caballero-Díazet al., 2013; Das et al., 2017; Menichetti et al., 2023; Vanlalveni et al., 2024). Finally, the baseline gut microbiota composition and host factors shape the response to AgNPs exposure—individual differences in microbial communities, and host-specific parameters determine susceptibility to dysbiosis and ecological shifts (Ren et al., 2023). Even, AgNPs exposure during critical developmental periods leads to enduring gut dysbiosis, neurobehavioral, and metabolic alterations as evidenced in mice (Lyu et al., 2021). Together, these factors underscore that the effects of AgNPs on gut health are not solely dependent on dosage but are the result of complex nanoparticle–microbiome interactions that must be addressed in designing safe, targeted applications.

3.3 ZnO NPs and gut microbiota dynamics

ZnO NPs exert multifaceted effects on the human gut microbiota, influencing microbial diversity, community composition, and metabolic activity (Table 1) (Figure 2). Research shows that these effects are highly dependent on factors such as concentration and the individual’s health status. For example, ZnO NPs [0 mg/kg (control), 25 mg/kg, 50 mg/kg, and 100 mg/kg] were fed to poultry birds for 9 weeks; at the highest concentration (100 mg/kg), ZnO NPs tended to reduce microbial richness and diversity, particularly impacting beneficial bacteria such as Lactobacillus (Feng et al., 2017). Exposure of the human intestinal microbiome to ZnO NPs at 0.1, 2.5, and 50 mg/L revealed clear dose-dependent effects. While low concentrations caused minimal changes, higher doses (especially 50 mg/L) significantly altered microbial composition, reduced diversity, and disrupted metabolic functions (Zhang et al., 2021). However, the response is not uniform across all populations. In children with Autism Spectrum Disorder, ZnO NPs actually increased gut bacterial diversity, whereas a decrease was observed in healthy children, suggesting that pre-existing health conditions may modulate the microbial response to ZnO NP exposure (Yu et al., 2021). Metabolically, ZnO NPs have been associated with a reduction in the production of SCFAs, which play essential roles in gut health and host metabolism (Zhang et al., 2021). Additionally, alterations in gut microbiota composition due to ZnO NPs have been linked to changes in plasma metabolites, indicating a complex and systemic metabolic impact (Feng et al., 2017). The effects of ZnO NPs also extend to microbial resistance traits. While medium concentrations were shown to reduce antibiotic resistance genes, low concentrations paradoxically enriched tetracycline resistance genes, revealing a nuanced influence on the gut resistome (Zhang et al., 2021). Interestingly, not all effects of ZnO NPs are negative. In certain contexts, such as in broiler chickens, ZnO NPs have been found to support the growth of beneficial bacteria, enhance gut health, and boost immune function (Qu et al., 2023). This duality highlights the complexity of ZnO NP interactions with the gut microbiome and underscores the need for further targeted studies to fully elucidate their health implications.

ZnO NPs influence gut microbiota through several mechanisms of action, with their effects varying depending on individual health status, such as in children with Attention-Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder or Autism Spectrum Disorder, as well as in various animal models. One of the primary mechanisms is their antibacterial activity. ZnO NPs have been shown to inhibit the growth of gut bacteria, particularly in healthy children, where they significantly reduced the number of live bacterial cells (Zhou et al., 2021; Yu et al., 2021). However, this response appears to differ in children with ASD, where ZnO NP exposure was associated with an increase in gut bacterial diversity, suggesting a more complex interaction with pre-existing microbial communities (Yu et al., 2021). Additionally, ZnO NPs are known to modulate microbial diversity by altering the overall community structure of gut bacteria. Higher concentrations, particularly 100 mg/kg, orally, for 9 days have been linked to a notable decline in beneficial bacteria such as Lactobacillus in poultry birds, with bacterial richness showing a negative correlation with ZnO NPs concentration indicating that excessive exposure may contribute to gut dysbiosis (Feng et al., 2017). Beyond their antimicrobial properties, ZnO NPs also possess anti-inflammatory effects. In conditions such as ulcerative colitis, they have been reported to help restore gut homeostasis by activating the Nrf2 signaling pathway and reducing levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines (Li et al., 2017). These findings suggest that while ZnO NPs can beneficially modulate gut microbiota and reduce inflammation under certain conditions, their overuse or inappropriate application may lead to harmful effects. Therefore, careful consideration of dosage and individual health status is essential when evaluating the therapeutic or dietary use of ZnO nanoparticles.

3.4 Carbon nanomaterials-gut microbiota interaction

CNMs, including single-walled carbon nanotubes (SWCNTs) and graphene oxide (GO), CNM-based nanozymes, quantum dots have a significant and multifaceted impact on the human gut microbiota, influencing both microbial composition and metabolic processes (Table 1) (Bantun et al., 2022; Zhao et al., 2024). These materials become integrated into the gut’s carbon flow, where they affect microbial fermentation and alter the production of key metabolites such as butyrate (Cui et al., 2023). This interaction has the potential to influence the proliferation and differentiation of intestinal stem cells, raising concerns about the possible health risks associated with CNM exposure. One major impact of CNMs is on the microbial composition within the gut. Studies in rodents show that single-walled CNTs and GO, when ingested, alter microbial composition shifting the Firmicutes/Bacteroidetes balance and increasing pro-inflammatory taxa like Alistipes and Lachnospiraceae (Chen et al., 2018; Utembe et al., 2022). CNM exposure can inhibit the growth of beneficial probiotic bacteria while promoting the growth of opportunistic pathogens, leading to dysbiosis (Figure 2) (Ma Y. et al., 2023; Wojciechowska et al., 2023; Chen et al., 2025). Interestingly, CNMs may also lead to an increase in butyrate-producing bacteria, as some of these microbes can utilize CNMs as a carbon source. This shift in population dynamics can have downstream effects on gut health and homeostasis (Cui et al., 2023). Beyond compositional changes, CNMs also influence gut microbial metabolism. Through fermentation, CNMs are converted into organic metabolites such as butyrate, which plays a critical role in gut physiology. However, the excessive production of butyrate due to CNM metabolism can disrupt normal intestinal processes by affecting the proliferation and differentiation of intestinal stem cells (Cui et al., 2023). These metabolic shifts could have long-term implications for intestinal function and overall health. Although the adverse effects of CNMs on gut microbiota are becoming increasingly evident, the broader implications for human health are still being explored. Responses to CNM exposure appear to vary among individuals, likely due to differences in baseline microbiota composition and genetic predispositions. Therefore, more comprehensive research is necessary to understand the full scope of health risks and to identify potential strategies for mitigating the negative effects of CNMs on the gut microbiome (Wojciechowska et al., 2023; Zickgraf et al., 2023; Chen et al., 2025).

The mechanisms through which CNMs affect the human gut microbiome are complex, involving both direct interactions with microbial populations and indirect influences via metabolic pathways. Recent research has shown that CNMs, such as single-walled carbon nanotubes and GO, can be utilized by gut microbiota as a novel carbon source. This fermentation process results in the production of beneficial metabolites such as butyrate, a SCFA, essential for gut health and the regulation of intestinal cellular functions (Cui et al., 2023). CNMs enhance microbial fermentation by selectively supporting the growth of specific butyrate-producing bacteria, thereby increasing butyrate levels in the gut. This has important implications for maintaining intestinal health and promoting epithelial integrity (Cui et al., 2023). However, the impact of CNMs on microbial metabolism is concentration-dependent. While moderate levels may support SCFA production, high concentrations of CNMs can suppress key metabolic pathways, disrupting SCFA synthesis and potentially leading to adverse physiological outcomes (Figure 2) (Cui et al., 2023; Wojciechowska et al., 2023). In addition to their metabolic effects, CNMs possess antimicrobial properties. They can compromise microbial cell integrity through oxidative stress, membrane disruption, and other toxic effects. The antimicrobial efficacy of CNMs including GO, CNTs, fullerenes, and carbon quantum dots is strongly governed by their physical and chemical attributes: size, shape, and surface functionalization. (Maksimova, 2019). Smaller GO sheets, for instance, exhibit higher oxidative stress–mediated killing when used as surface coatings, while larger sheets in suspension are more effective at entrapping and isolating bacteria, with smaller ones (∼0.01 µm2) showing a four-fold increase in antibacterial activity relative to larger sheets (∼0.65 µm2) in coatings (Perreault et al., 2015). The shape is equally decisive: sharp, high-aspect-ratio edges such as those in GO nanowalls or CNT tips mechanically disrupt bacterial membranes, significantly reducing survival rates of E. coli and S. aureus (Mohammed et al., 2020). Surface functionalization further modulates activity: oxygenated groups (–COOH, –OH), reduced forms (rGO), or conjugation with Cu2+ or Ag nanoparticles enhance dispersion, surface charge, ROS production, and targeted adhesion, with rGO–Cu hybrids achieving two orders of magnitude greater antibacterial effect compared to rGO alone (Tu et al., 2021). Thus, tuning CNM size, tailoring sharp morphologies, and engineering surface chemistries—especially via metal decoration or functional groups—synergistically optimize antimicrobial performance (Cobos et al., 2020; Khairol Anuar et al., 2021). Although CNMs hold promise for modulating gut microbial activity and enhancing certain health-related functions, their long-term impact on microbial diversity and gut health remains uncertain. Prolonged or high-level exposure may disrupt normal microbial communities and even promote the development of antibiotic resistance (Figure 2) (Xie et al., 2016). Therefore, while the therapeutic potential of CNMs is notable, careful evaluation of their safety and biological interactions is essential.

The interactions of ENMs with the human microbiome cannot be fully understood without considering their broader ecological footprint. ENMs released into soil, water, and air do not remain confined to the environment but can re-enter the food chain and drinking water, ultimately influencing human exposure. For instance, agricultural ENMs that alter soil or rhizosphere microbial communities may indirectly affect nutritional and microbial inputs to the human gut via crops (Mgadi et al., 2024; Dixit et al., 2024); similarly, ENM contamination of aquatic systems can influence water-borne microbiota that serve as reservoirs of antimicrobial resistance genes (Cui and Smith, 2022). Studies show that exposure to polluted or microbe-rich environments correlates with shifts in gut microbiome composition and diversity, suggesting a soil-plant-gut axis of microbial transmission and those environmental pollutants select for microbiome functionality in the gut (Ma et al., 2025; De Filippis et al., 2024). Thus, environmental and human microbiomes are interconnected through shared exposure pathways, bioaccumulation, and resistome exchange, highlighting the need to view ENM–microbiome interactions not as isolated domains but as part of a continuum linking ecosystem health and human health.

4 ENMs and environmental microbial communities

ENMs, such as nano-TiO2 and various metal NPs, have a profound impact on water-borne microbial communities, influencing key ecological functions like nutrient cycling and overall ecosystem health (Table 2). Chronic exposure to ENMs can disrupt the structure and function of microbial communities, leading to significant changes in biogeochemical processes essential for ecosystem sustainability. For instance, long-term exposure to nano-TiO2 has been found to reduce biofilm biomass and alter microbial community composition by decreasing the presence of taxa involved in nitrogen fixation and denitrification, the processes critical to nutrient cycling (Binh et al., 2016; Passarelli et al., 2020). Similarly, metal NPs such as silver and copper exhibit toxicity toward microbial populations, impairing enzymatic activities necessary for processes like nitrogen fixation and organic matter decomposition (Peyrot et al., 2014; Chhipa, 2021). ENMs also affect microbial activity by suppressing fundamental metabolic processes including respiration and photosynthesis, which are essential for maintaining ecosystem functions (Binh et al., 2016). Additionally, the presence of ENMs can lead to a shift in microbial community composition, favoring resistant taxa while reducing those crucial for nutrient cycling, thereby impairing key ecosystem services (Binh et al., 2016). These disruptions can have cascading effects on ecosystem health, such as reduced soil fertility and compromised ecosystem functionality, ultimately threatening agricultural productivity and environmental stability (Yadav and Yadav, 2024). Despite these concerns, some studies suggest that under certain conditions, ENMs may also enhance specific microbial functions or increase microbial resilience, highlighting a complex and context-dependent interaction between ENMs and microbial communities. As such, a comprehensive understanding of the dual roles of ENMs, both beneficial and detrimental is essential for evaluating their environmental impact and guiding their responsible use (Yadav and Yadav, 2024).

4.1 Impact of ENMs on aquatic ecosystems

ENMs, such as nano-TiO2 and various metal NPs, profoundly affect aquatic microbial communities, disrupting ecological processes like nutrient cycling and ecosystem stability (Table 2) (Figure 2). In freshwater systems, chronic exposure to nano-TiO2 can drastically reduce biofilm biomass and alter community composition, particularly diminishing nitrogen-fixing bacteria like Azotobacter and denitrifiers such as Pseudomonas, which play essential roles in nitrogen cycling (Binh et al., 2014). Short-term exposure further highlights species-specific effects: nano-TiO2 has been shown to depress Bacillus subtilis and Aeromonas hydrophila, while paradoxically enhancing growth of Arthrobacter and Klebsiella, likely by photo-oxidizing organic matter into more bioavailable forms (Binh et al., 2014). Simultaneously, metal NPs like copper oxide (CuO NPs) disrupt critical microbial function such as nitrate reduction by damaging cell membranes, down-regulating enzymes like NADH dehydrogenase, cytochromes, nitrate and nitrite reductases in model denitrifier Paracoccus denitrificans, ultimately reducing denitrification efficiency by roughly 36% (from ∼98% to ∼62%) at concentrations between 0.05–0.25 mg/L (Su et al., 2015).

ENMs also impair microbial metabolic pathways integral to ecosystem function. Nano-TiO2 and ZnO NPs suppress respiration and photosynthesis in primary producers; for instance, ZnO exposure lowers photosynthetic activity in cyanobacteria like Microcystis aeruginosa. Nano-TiO2 inhibits metabolic activity in algae and bacteria, reshaping taxa distribution by reducing sensitive algal species and allowing more resistant cyanobacteria to thrive, raising concerns around harmful algal blooms (Chen B. et al., 2022). These disruptions carry serious ecological consequences (Figure 2). In agricultural runoff zones, ENMs can reduce microbial diversity and soil nutrient availability, decreasing fertility and crop yield. In wetlands, altered biofilm and microbial enzyme activity impairs organic matter decomposition, affecting carbon sequestration and water purification. However, not all effects are negative: low concentrations of iron oxide NPs have been observed to stimulate growth and denitrification in P. denitrificans and other denitrifiers, illustrating the nuanced, context-dependent nature of ENM–microbe interactions. Therefore, ENMs exert complex dual roles in aquatic ecosystems: they can both disrupt and potentially enhance microbial community structure and function. A deeper, context-sensitive understanding of these interactions is essential to assess environmental risks and guide responsible applications of nanotechnology.

The influence of ENMs on bioaccumulation and ecotoxicological effects within keystone microbial species is profound and multifaceted. Silver and copper NPs, for instance, readily accumulate in microbial cells, disrupting physiological functions and reshaping community structures based on concentration and particle type (He et al., 2014; Von Moos and Slaveykova, 2014). In freshwater sediments, exposure to citrate- and PVP-coated AgNPs at 0, 25, 50, 75, 100, and 125 mg/L caused dose-dependent inhibition of microbial functional diversity. At the highest concentration (125 mg/L), citrate-AgNP significantly reduced microbial catabolic activity by up to 80% and diminished both substrate richness and diversity, impairing organic matter degradation and broader nutrient cycling (Kusi et al., 2020). This bioaccumulation at lower trophic levels also poses a risk of trophic transfer, potentially leading to biomagnification in higher organisms.

Ecotoxicologically, ENMs can both generate ROS at their surfaces (e.g., via catalytic activity or metal ion release) and induce ROS production within organisms (e.g., via mitochondrial dysfunction or activation of NADPH oxidases) (Mendoza and Brown, 2019; Ge et al., 2019). This oxidative stress disrupts essential enzymatic and metabolic functions such as nitrogen fixation, respiration, and organic matter decomposition, all critical for ecosystem sustainability (Von Moos and Slaveykova, 2014; Zhai et al., 2018; Gambardella and Pinsino, 2022). In microbial and algal models (e.g., Chlorella vulgaris), exposure to CNTs and metal-oxide NPs triggered elevated antioxidant enzyme activity (e.g., superoxide dismutase) alongside ROS-induced damage and reduced cell viability (Pereira et al., 2014). In environmental contexts, even low levels of AgNPs reduced metabolic diversity in organic-matter-associated microbial communities, which in turn indirectly stunted invertebrate growth in aquatic food webs (Zhai et al., 2018; Guo et al., 2019; Bao et al., 2016; Kusi et al., 2020). The toxicity of these materials is closely tied to their physicochemical characteristics such as size, shape, surface chemistry, ion dissolution rates, all of which modulate interactions with microbial cells (Triboulet et al., 2013; He et al., 2014; Pereira et al., 2014; Von Moos and Slaveykova, 2014; Kusi et al., 2020). For instance, the ecotoxicity of silver varies significantly between metallic AgNPs and their sulfide-transformed forms (Ag2S), with reduced bioavailability and toxicity in soils (Courtois et al., 2019). Copper NPs similarly trigger oxidative stress and metabolic shifts in bacteria, affecting glutathione levels and antioxidant enzyme pathways (Figure 2) (Rana and Kalaichelvan, 2013; Triboulet et al., 2013; Javurek et al., 2017).

Despite these adverse outcomes, there is emerging potential for ENMs in bioremediation applications, where targeted use of certain NPs can enhance microbial degradation of pollutants. This highlights a complex dual role: while ENMs may pose significant ecological hazards, they also offer novel opportunities for environmental management. However, addressing this duality requires nuanced and context-aware research to assess long-term impacts and guide responsible use of nanotechnologies.

4.2 Impact of ENMs on soil microbiome

ENMs significantly influence soil microbial diversity and enzymatic activities, thereby affecting soil health and agricultural productivity (Figure 2). Exposure to metal ENMs such as AgNPs, ZnO NPs and TiO2 NPs can significantly alter microbial metabolic diversity and key enzyme functions in soils (Table 2) (Rajput et al., 2023; Islam, 2025). In one study, metal ENMs like AgNPs and ZnO NPs altered community-level physiological profiles of soil bacteria and significantly decreased the diversity indices, such as Shannon’s diversity index, Evenness diversity index, and Simpson’s diversity index while TiO2 NPs had no detectable impact (Asadishad et al., 2018; Chavan and Nadanathangam, 2020; Yadav and Yadav, 2024). Further, soil amendments with AgNPs, ZnO NPs, and CuO NPs showed dose-dependent effects on enzymatic activity: ZnO and CuO either enhanced or had no effect at moderate doses (1–10 mg/kg), while AgNPs at higher concentrations (100 mg/kg) inhibited enzymes such as dehydrogenase, phosphatase, and urease (Tripathi et al., 2023). High levels of ZnO, TiO2, and CeO2 (around 1,000 mg/kg) also reduced populations of Azotobacter and other nutrient-solubilizing bacteria, along with suppressed enzyme activities. AgNPs are reported to suppress populations of essential nitrogen-fixing and nitrifying microbes, including Rhizobium and Nitrosomonas, which disrupts nitrogen cycling processes in soil ecosystems (Shah and Belozerova, 2009). Likewise, ZnO NPs have been found to impair microbial respiration and inhibit key enzymatic activities, such as dehydrogenase and urease, both of which are vital for organic matter breakdown and nutrient recycling (Parada et al., 2019). In another study, acute exposure to CuO NPs (10–500 mg kg-1) through nano-pesticide markedly inhibited soil denitrification, with the highest dose (500 mg kg-1) causing an 11-fold increase in nitrate accumulation and a 10.2%–24.1% reduction in N2O emissions. This suppression was linked to decreased activities of nitrate reductase and nitric oxide reductase, along with inhibited electron transport system activity, altered expression of denitrifying functional genes, and shifts in bacterial community composition (Zhao et al., 2020). Similarly, only 90-day exposure of agricultural soils to TiO2 NPs (1 and 500 mg kg-1) significantly inhibited nitrification enzyme activities and reduced the abundance of ammonia-oxidizing microorganisms, as indicated by decreased amoA gene copies. This suppression cascaded to reduce denitrification enzyme activity, with declines in nirK and nirS gene abundances, alongside marked shifts in bacterial community structure, even at the lowest realistic NP concentration (Simonin et al., 2016). These disruptions can impair soil nutrient cycling. Specifically, enzymes critical for organic matter decomposition and nutrient release such as urease, phosphatase, and dehydrogenase show decreased activity upon ENM exposure, threatening soil fertility (Figure 2) (Asadishad et al., 2018; Chavan and Nadanathangam, 2019). Moreover, ZnO and CuO NPs may reprogram microbial metabolic pathways by upregulating nitrogen fixation genes (nifH, amoA) while downregulating denitrification genes (norB, nosZ), leading to imbalances in nitrogen cycling (Luche et al., 2016; Sun et al., 2022; Tripathi et al., 2023). Despite these negative impacts, low to moderate ENM levels could stimulate microbial resilience. Biogenic NMs like nanozeolite and nanochitosan, combined with plant probiotics, were found to enhance dehydrogenase, alkaline phosphatase, and fluorescein diacetate hydrolase activities—doubling or tripling enzyme performance under agricultural conditions (Upadhayay et al., 2023), a promising application in sustainable agriculture.

ENMs profoundly affect plant–microbe interactions, especially those involving mycorrhizal fungi and nitrogen-fixing bacteria, with outcomes that vary depending on material type, concentration, and microbial partners (Table 2). Arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi, essential for enhancing plant nutrient uptake, can be adversely impacted by ENMs, which inhibit fungal growth and disrupt nutrient exchange between plants and soil (Yu M. et al., 2020; Vera-Reyes et al., 2023). Additionally, nitrogen-fixing bacteria such as Bradyrhizobium diazoefficiens are sensitive to ENM exposure: cerium oxide nanoparticles (CeO2 NPs) and multi-walled carbon nanotubes (MWCNTs) can suppress their growth, reduce nodulation competitiveness, and interfere with plant–bacteria signaling critical for effective symbiosis (Mortimer et al., 2020). ENMs further reshape the soil microbiome, altering processes such as mineralization and nitrogen fixation (Figure 2). Their antimicrobial properties can decrease beneficial microbial populations, further disrupting plant–microbe symbioses. This disruption undermines soil functions that are key to plant health. However, context matters: in certain situations, NMs have been shown to enhance plant growth and mitigate abiotic stress by supporting beneficial microbial interactions and functioning as “smart fertilizers” (Ma et al., 2022; Berrios et al., 2023; Sodhi et al., 2025). At low concentrations (∼5 mg/kg Ag and 50 mg/kg Zn and Ti), ENMs in biosolids did not adversely affect Medicago truncatula growth or metal accumulation in shoots. Instead, they enhanced symbiotic interactions with rhizobia (Sinorhizobium meliloti), as reflected by a higher nodule number, and significantly increased total soil microbial biomass. Furthermore, ENM exposure at low concentrations altered microbial community composition, increasing Gram-negative and anaerobic bacteria while reducing eukaryotic abundance. These findings suggest potential stimulatory effects of transformed ENMs on soil microbial activity and plant–rhizobia symbiosis (Chen et al., 2017). Exposure to ZnO NPs as nanofertilizer at 10 mg/kg and 100 mg/kg significantly reshaped the rhizospheric bacterial community structure, particularly altering the abundance of Cyanobacteria and key plant growth-promoting taxa, while alpha diversity remained stable. These compositional shifts were more pronounced at the higher dose (100 mg/kg), suggesting dose-dependent effects of ZnO NPs on soil microbial ecology. While 10 mg/kg ZnO NPs also coincided with enhanced lettuce biomass and photosynthetic rate, no additional plant growth benefits were observed at 100 mg/kg, despite the intensified microbial community changes (Xu et al., 2018). Therefore, the effects of ENMs on soil microbial communities are complex. High concentrations of metal-based NPs tend to inhibit diversity and enzyme function compromising nutrient cycling and soil fertility, while the use of certain nanobiofertilizers at controlled doses shows potential for improving microbial function and crop productivity (Zhang et al., 2024). Therefore, ENMs offer potential agricultural benefits such as improved nutrient delivery and stress resistance, while their adverse effects on crucial microbial partnerships raise concerns about their long-term ecological impact. This underscores the need for targeted research to balance ENM applications benefits against ecological risks.

5 Cross-talk between ENMs and microbial resistance

ENMs are increasingly implicated in exacerbating antimicrobial resistance among microbial communities by facilitating the persistence and dissemination of antimicrobial resistance genes (ARGs). Notably, metal oxide NPs such as ZnO NPs have been shown to promote horizontal gene transfer among bacteria. In laboratory and soil studies, ZnO NPs increased transformation frequency in E. coli by approximately 1.8-fold and enhanced the copy number of metal resistance–linked genes, indicating co-selection of resistance mechanisms (Markowicz et al., 2023; Otinov et al., 2020; Wang X. et al., 2024; Alav and Buckner, 2024). Furthermore, AgNPs and CuNPs stimulate the conjugative transfer of ARG-laden plasmids across bacterial genera; for instance, silver ions and AgNPs have been shown to facilitate plasmid-mediated resistance gene transfer, and CuNPs promoted multi-antibiotic resistance gene spread in environmental bacteria (Yu K. et al., 2020). The mechanisms underlying these effects include enhanced horizontal gene transfer among bacterial communities, particularly fostering the spread of ARGs through oxidative stress, increased membrane permeability, induction of the bacterial SOS response, and upregulation of conjugation-related genes (Figure 2) (Yu K. et al., 2020). Sub-lethal exposure to ENMs like nano-alumina (Al2O3) has been shown to induce ROS, which damage cell membranes and create pores that facilitate plasmid uptake; this also triggers the SOS DNA damage response that further promotes plasmid transformation and conjugation (e.g., pBR322 into E. coli and S. aureus)—a striking increase in horizontal gene transfer efficiency linked directly to NP presence (Ding et al., 2016). Similarly, nanofullerene (nC60) exposure increases ROS generation and membrane disruption, upregulating genes crucial for DNA transfer and conjugative machinery (e.g., trbBp, korA/B) in exposed bacteria (Ji et al., 2020; Amaro et al., 2021). ENMs also act as environmental ARG reservoirs. For example, certain NPs can adsorb plasmids or ARG-containing DNA, protecting them from degradation and increasing their environmental persistence. CeO2 NPs, in particular, have been investigated both for their facilitation and inhibition of antimicrobial resistance genes propagation; while some studies identified increased conjugation, others found that CeO2 can suppress antimicrobial resistance genes transfer by reducing ROS and downregulating horizontal gene transferring genes (Yu K. et al., 2020; Sharma et al., 2025). Additionally, ENMs impose selective pressure on microbial communities: resistant strains, better able to cope with metal-induced stress, proliferate while susceptible strains decline leading to enrichment of antimicrobial resistance traits (Neethu et al., 2022).

Comprehensive reviews reinforce the notion that ENMs in environments from various sources such as wastewater treatment plants exert selective pressure on microbial communities and enhance horizontal gene transfer by increasing membrane permeability through both direct interaction and ROS-mediated damage, concurrently inducing genetic changes linked to conjugation (Figure 2) (Cui and Smith, 2022; Li et al., 2025). Additionally, ENMs contribute to these effects by adsorbing extracellular ARGs and plasmids, protecting them from degradation and facilitating persistence and uptake in microbial populations (Ding et al., 2016; Cui and Smith, 2022; Xu et al., 2023; Kalli et al., 2023; Kaushik et al., 2023; Mosaka et al., 2023; Li et al., 2025). These processes lead to accelerated spread of resistance genes in microbial communities, with ENMs acting as vectors and catalysts for antimicrobial resistant gene propagation in wastewater and natural environments, a trend confirmed by increased antimicrobial resistant gene and mobile genetic element abundance following NP exposure (Ding et al., 2016; Cui and Smith, 2022; Li et al., 2025). However, research also suggests a potential dual role: emerging NP designs with antioxidant or electrochemical properties may attenuate ARG transmission, indicating a path toward mitigating antimicrobial resistance spread via ENMs. The ENMs may also hold beneficial potential in antimicrobial resistance mitigation by their use in targeted drug-delivery systems for antibiotics and/or having synergistic effects reducing the overall required dosage, lowering selective pressure and slowing resistance development (Ribeiro et al., 2022; AlQurashi et al., 2025; Sharma et al., 2025). For instance, encapsulation of enrofloxacin in PLGA and lignin NPs mitigated its disruptive effects on the gut microbiome compared to free enrofloxacin, with lignin-encapsulated Enro showing minimal impact on microbial diversity. Notably, NP delivery delayed the rise in ARG expression between 24 and 72 h, suggesting a potential to reduce antibiotic-induced resistome shifts in the gut (Herrera et al., 2024). Nano-ZnO exposures have been reported to cause dose-dependent alterations in gut microbiota composition and diversity, suppressed SCFA production, and shifted key microbial functional pathways. While medium doses (2.5 mg/L) reduced several ARGs by inhibiting host bacteria, low doses (0.1 mg/L) unexpectedly enriched tetracycline resistance genes, highlighting potential risks to gut health and resistome stability (Zhang et al., 2021). Another study reported that during cultivation of leachate microbiota, ARG diversity and abundance dropped significantly (1.4–3.2 log), with NPs—especially metal oxides (CuO, ZnO)—enhancing this attenuation in an ARG-specific manner. The attenuation was driven by metal-induced bacterial growth inhibition, dissolved ion stress, and internalized NPs inducing oxidative stress (ROS), which together reduced horizontal ARG transfer and damaged resistance genes (Su et al., 2019). Altogether, ENMs may promote antimicrobial resistance—yet, with mindful design, they may also serve as tools to counteract microbial resistance dissemination in environmental as well as in vivo settings.

Another crucial aspect is ENMs in combination with existing pollutants, such as heavy metals, can synergistically drive microbial resistance, posing a complex environmental hazard (Balta et al., 2025). ENMs like TiO2 NPs and ZnO NPs interact with heavy metals to alter their bioavailability, which may enhance metal uptake by microbes and foster resistance via genetic mutations or horizontal gene transfer. This synergy not only increases toxicity to microbial populations but also pressures communities to develop resistance mechanisms such as efflux pumps and biofilm formation (Dickinson et al., 2019; Wu et al., 2021). The combined presence of ENMs and pollutants alters microbial community structures, often favoring resistant strains over susceptible ones and intensifying resistance traits through continuous stress. Moreover, co-contamination with ENMs and organic pollutants can result in synergistic toxicity effects that are typically underestimated in conventional environmental risk assessments (Tufail et al., 2022; Zhu et al., 2024; Olawade et al., 2024). This increases the overall health risks posed by resistant pathogens by creating niches that sustain and spread antimicrobial resistance (Balta et al., 2025). Despite these challenges, the interaction between ENMs and pollutants also presents opportunities for novel antimicrobial strategies. By understanding these synergistic effects, researchers hope to develop targeted nanoparticle-based interventions that can disrupt resistant microbial communities or enhance contaminant removal, offering a balanced approach to combating antimicrobial resistance.

6 Tools and techniques for assessing ENM-Microbiome interactions

Assessing the impact of ENMs on microbiome interactions requires a comprehensive, multi-tiered approach that integrates high-throughput sequencing (16S rRNA, metagenomics, metatranscriptomics), functional assays (enzyme activity, SCFA profiling, metaproteomics, metabolomics), resistome analysis (qPCR, metagenomics), microscopy techniques (TEM, confocal), and in vitro/in vivo models (organoids and organ-on-a-chip technologies, gnotobiotic mice, “Humanized” murine models) to evaluate compositional, functional, and genetic changes. Advanced tools like meta-analyses and machine learning further enhance the interpretation of complex omics data and support a holistic understanding of ENM–microbiome dynamics (Galloway-Peña and Hanson, 2020; Moreno-Indias et al., 2021; Mortimer et al., 2021). A global meta-analysis involving over 2,100 observations demonstrated clear negative effects of ENMs on soil microbial diversity, biomass, and functional enzyme activity, with machine learning models effectively predicting key determinants of impact, highlighting the power of these computational tools for ecological risk assessment. Beyond statistical modeling, mass spectrometry-based multi-omics approaches, including genomics, proteomics, lipidomics, and metabolomics provide essential systems-level insights into how ENMs alter microbial physiology and cellular pathways, revealing widespread adaptations and stress responses at multiple biological layers (Day et al., 2023). Community structure analysis further shows that ENMs, especially metal NPs, can profoundly disrupt microbial populations, diminishing critical functions like nutrient cycling and pollutant degradation by suppressing enzymatic activities.

Despite the robustness of these methodological frameworks, significant variability across studies underscores the need for standardized protocols. Differences in ENM types, doses, exposure durations, microbial communities, and omics platforms often limit comparability and reproducibility. Addressing this heterogeneity through harmonized experimental designs and cross-laboratory validation will be crucial to ensure consistent and reliable assessments of ENM-induced ecological risks across diverse environments.

6.1 Marker gene sequencing for microbiome analysis

Marker gene sequencing is a widely used and cost-effective approach in microbiome analysis that targets conserved genetic regions (e.g., 16S rRNA for bacteria and archaea, ITS for fungi, 18S rRNA for eukaryotes) to profile microbial community composition and diversity (Figure 3). This technique enables identification and relative quantification of taxa within complex microbial ecosystems by amplifying and sequencing these phylogenetic markers. It provides insights into taxonomic structure but has limited resolution for functional and strain-level analysis compared to whole metagenome sequencing (De la Cuesta-Zuluaga and Escobar, 2016; Douglas et al., 2018; Johnson et al., 2019; Galloway-Peña and Hanson, 2020; Bharti and Grimm, 2021).

Figure 3. General workflow for marker gene sequencing in microbiome analysis. The schematic outlines the traditional metagenomics workflow using amplicon sequencing of marker genes (16S rRNA for bacteria/archaea, 18S rRNA for eukaryotes, and ITS for fungi). Key steps include DNA extraction, amplification of target regions, high-throughput sequencing, and bioinformatics analysis for taxonomic profiling and diversity assessment.

6.1.1 16S ribosomal RNA (rRNA) gene sequencing

16S rRNA gene sequencing is a cornerstone method for profiling bacterial and archaeal communities by targeting conserved and hypervariable regions (e.g., V1–V2, V3–V4, V4–V5) of the ∼1,500 bp 16S gene. Primer choice such as V3–V4 for broad bacterial coverage or V1–V2 for higher species resolution is critical to capture the desired taxonomic groups accurately (Na et al., 2023; Combrink et al., 2023; Lee et al., 2023). Post-sequencing, raw reads undergo quality filtering, chimera removal, and demultiplexing using pipelines like QIIME 2 or Mothur (Galloway-Peña and Hanson, 2020; Combrink et al., 2023; Lewis et al., 2021). Feature tables can be generated as Operational Taxonomic Units (OTUs) by clustering at ∼97% similarity which is effective for legacy comparisons and mitigating sequencing noise, or as Amplicon Sequence Variants (ASVs) via denoising tools like DADA2 for single-nucleotide resolution, improved reproducibility, and finer ecological insights (Galloway-Peña and Hanson, 2020; Lewis et al., 2021; Jeske and Gallert, 2022; Chiarello et al., 2022; Daly et al., 2024). Finally, taxonomic assignment is performed against curated databases (e.g., SILVA, Greengenes) and downstream analyses include diversity metrics and phylogenetic comparisons to reveal community structure and dynamics (Figure 3) (Johnson et al., 2019; Lewis et al., 2021; Combrink et al., 2023).

Using 16S rRNA gene sequencing targeting the V3–V4 region, a study revealed that long-term dietary exposure to Ag, SiO2, and TiO2 NPs significantly altered the gut microbiota composition and β-diversity in mice. ASV analysis using DADA2 method showed a dose-dependent increase in Cyanobacteria and a marked reduction in Tenericutes and Turicibacter with TiO2 NPs, while SiO2 and TiO2 also suppressed SCFA production. These shifts in microbial composition and metabolic function were largely reversible after an 8-week recovery period without NP exposure, indicating transient but notable perturbations of the gut microbiome by dietary NMs (Perez et al., 2021). Another research employed 16S rRNA gene sequencing (targeting V1–V3 regions with 27f/534r primers) to investigate the influence of plant-derived nanoparticles on the gut microbiome of germ-free mice colonized with human fecal bacteria. Sequencing on the 454 Jr. platform and QIIME 2-based analysis revealed significant shifts in microbiota composition upon NP exposure, with notable enrichment of Lachnospiraceae, Bacteroidaceae, Coriobacteriaceae, and Ruminococcaceae families. OTUs were clustered at 97% similarity, and hierarchical clustering highlighted differences between in vitro and in vivo bacterial uptake of plant-derived nanoparticles, suggesting these NPs selectively modulate gut microbial communities and may alter functional pathways (Teng et al., 2025). Further, 16S rRNA gene sequencing revealed that oral exposure to SiO2NPs in young mice significantly altered gut microbiota composition and diversity, with increased abundances of Firmicutes and Patescibacteria and distinct shifts in β-diversity profiles. OTU-based analysis (97% similarity) and LEfSe identified 41 bacterial clades with differential abundance, suggesting SiO2NP-induced microbiome dysbiosis, which was associated with neurobehavioral impairments via disruption of the gut–brain axis (Diao et al., 2021). Oral exposure to lead-based (CsPbBr3) perovskite nanoparticles (CPB-PNPs) induced significant, dose-dependent alterations in gut microbiota composition as revealed by 16S rRNA gene sequencing. ASV-based analysis showed reduced alpha diversity indices (Chao1, Shannon, Simpson) and a marked shift in β-diversity, as evidenced by principal coordinate analysis (PCoA). High-dose CPB-PNPs increased pro-inflammatory taxa such as Clostridia and decreased beneficial Muribaculaceae, disrupting the Firmicutes/Bacteroidetes ratio. Differential abundance analysis further identified enrichment of microbial taxa linked to intestinal inflammation. These microbiota perturbations were associated with compromised gut barrier integrity and colitis-like phenotypes in exposed mice (Mei et al., 2023).

6.1.2 18S rRNA and internal transcribed spacer (ITS) sequencing

18S rRNA and ITS amplicon sequencing are pivotal techniques for profiling fungal and other eukaryotic communities in microbiome studies (Figure 3). The 18S rRNA gene, with its conserved and hypervariable regions (V1–V9), enables broad phylogenetic placement across diverse eukaryotes, though it typically resolves taxa only down to genus level. In contrast, the ITS regions (ITS1 and ITS2), located between 18S, 5.8S, and 28S genes, exhibit high variability and are therefore standard markers for species- and strain-level identification of fungi (Banos et al., 2018; Gao et al., 2021; Olivier et al., 2023). These amplicon data are processed through pipelines like QIIME 2, LotuS2, or ITSx, which include quality filtering, chimera removal, OTU/ASV clustering, and taxonomic assignment using curated databases such as SILVA for 18S and UNITE for ITS (Gao et al., 2021; Özkurt et al., 2022). This dual-marker approach offers comprehensive insights into eukaryotic microbiome structure and diversity. Using long-read sequencing of the nearly complete rRNA operon (16S-ITS-23S), a clear enhancement in species-level resolution of Lactobacillaceae has been reported compared to shorter amplicons. RibDif2 analysis revealed substantial allele overlap in V3–V4 (n = 43 overlaps) and whole 16S (∼11), while complete 16S-ITS-23S showed zero predicted overlaps. Empirical MinION™ data confirmed these predictions: full-length operon sequencing identified 100% of target species with fewer misclassifications, outperforming both V3–V4 (80% correct) and single 16S (∼95%), thus highlighting the combined power of 18S rRNA/ITS region (rRNA operon) for accurate microbiome profiling (Olivier et al., 2023).

Most of the available reports focused on 16S rRNA gene sequencing to track bacterial community changes, and responses of eukaryotic microbes (fungi, protozoa) via 18S/ITS remains largely unexplored in NP exposure contexts. Using 16S and 18S rRNA gene sequencing with PNA clamps and ITS qPCR, a study demonstrated that nanoscale sulfur (pristine and stearic acid-coated) modulated both bacterial and fungal communities in the tomato rhizosphere. While bacterial ASV diversity increased under nano-sulfur treatments, eukaryotic communities, particularly fungi and ciliates, showed resilience with minimal diversity shifts. ITS qPCR revealed no significant changes in total fungal abundance, but differential analysis indicated reduced relative abundance of Fusarium oxysporum in nano-sulfur treatments compared to controls. Enrichment of sulfur-oxidizing bacteria (Thiobacillus) and subtle shifts in fungal taxa suggest nano-sulfur may suppress soil-borne pathogens indirectly by altering microbiome composition and functional interactions (Steven et al., 2024).

6.2 Whole-genome shotgun (WGS) metagenomics

Whole-Genome Shotgun (WGS) metagenomics is an untargeted sequencing method that captures the entire genetic content of all microorganisms in a sample that include bacteria, archaea, fungi, viruses, and eukaryotes, providing comprehensive taxonomic and functional insights. Compared to 16S rRNA amplicon sequencing, WGS delivers higher species- and strain-level resolution, detects greater microbial diversity, and identifies functional genes such as antibiotic resistance and metabolic pathways (Ranjan et al., 2016; Jovel et al., 2016; Keepers et al., 2019; Brumfield et al., 2020). However, it is more expensive, requires deeper sequencing coverage, and demands advanced computational infrastructure due to large data volumes and complexity (Jovel et al., 2016; Fox et al., 2024). WGS metagenomics offers a powerful, holistic view of microbial communities and their functional potential, making it indispensable for studies that extend beyond taxonomic profiling into functional and ecological questions.

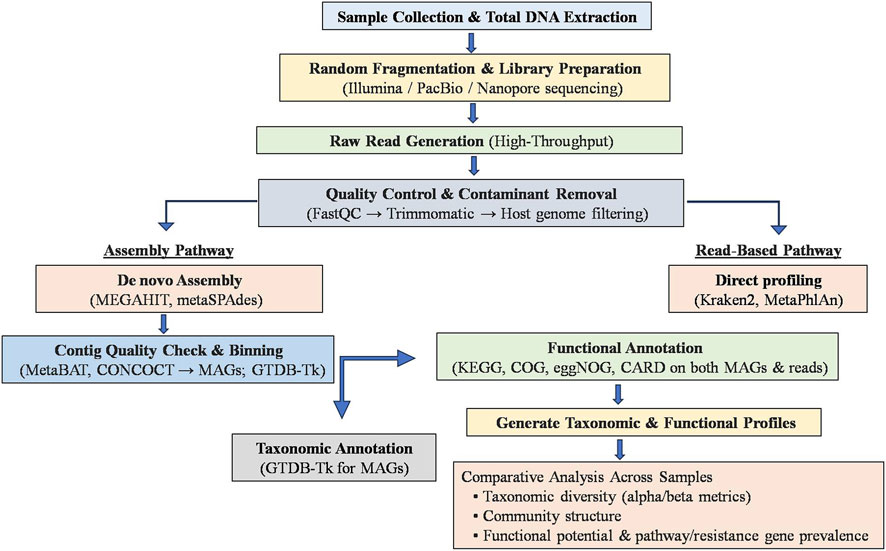

WGS metagenomics begins with sample collection and total DNA extraction, followed by random fragmentation and high-throughput sequencing (e.g., Illumina, PacBio, Nanopore). After quality control and contaminant removal (using tools like FastQC and Trimmomatic), reads are assembled de novo into contigs and binned into putative genomes (MAGs) using assemblers (e.g., MEGAHIT, metaSPAdes) and binning tools (e.g., MetaBAT, CONCOCT). These assemblies and unassembled reads are then annotated taxonomically (with tools like Kraken2, GTDB-Tk for MAGs, or Kraken2, MetaPhlAn for reads) and functionally profiled against databases such as KEGG, COG, eggNOG, and CARD to reveal metabolic pathways and resistance genes (Pérez-Cobas et al., 2020; Bharti and Grimm, 2021; Saenz et al., 2022). The final step involves comparing taxonomic and functional profiles across samples to assess microbial diversity, community structure, and functional potential (Figure 4).

Figure 4. General workflow for whole genome shotgun (WGS) metagenomics in microbiome analysis. The schematic illustrates the WGS metagenomics workflow starting from sample collection and total DNA extraction, followed by random fragmentation, library preparation, and high-throughput sequencing (e.g., Illumina, PacBio, Nanopore). Quality control and contaminant removal (using tools such as FastQC and Trimmomatic) are performed before downstream analysis. Two pathways are depicted: the assembly-based pathway involves de novo assembly (MEGAHIT, metaSPAdes), binning (MetaBAT, CONCOCT), and taxonomic annotation (GTDB-Tk); the read-based pathway uses direct profiling tools (Kraken2, MetaPhlAn). Both approaches undergo functional annotation (KEGG, COG, eggNOG, CARD) to generate taxonomic and functional profiles, supporting comparative analyses of microbial diversity, community structure, and functional potentials across samples.

WGS metagenomics and traditional metagenomics (e.g., amplicon sequencing of marker genes like 16S, 18S, or ITS) both aim to profile microbial communities, but they differ fundamentally in scope and resolution. WGS metagenomics sequences all DNA fragments randomly, enabling species- and strain-level identification, comprehensive detection of bacteria, archaea, fungi, viruses, and functional gene content including antibiotic resistance and metabolic pathways. In contrast, marker gene-based metagenomics targets specific loci (like 16S, 18S, ITS) to characterize community composition more cost-effectively and with simpler bioinformatics, though typically limited to genus-level resolution and offering limited insight into functional potential. While WGS metagenomics demands deeper sequencing, greater computational resources, and more complex analysis pipelines, it reveals richer diversity including rare taxa and accurate functional profiling, making it ideal for comprehensive ecological or clinical microbiome studies (Ranjan et al., 2016; Rausch et al., 2019; Brumfield et al., 2020; Pérez-Cobas et al., 2020; Wang Z. et al., 2023).