Abstract

Vernonia amygdalina is a perennial shrub that belongs to the family Asteraceae. The herb is an indigenous African plant that grows in most parts of sub-Saharan Africa. It is probably the most used medicinal plant in the genus Vernonia. Previous studies on the traditional medicinal value, nutritional composition, classes of phytochemical or compound isolation, and evaluation of their pharmacology activity are numerous. This provokes us to review and provide up-to-date evidence-based information on the study plant. A systematic online search using the databases of Google Scholar, PubMed, Science Direct, Wiley, Elsevier and Sci-Hub was carefully applied, using some important key words to get appropriate information. The leafy part of Vernonia amygdalina contributes greatly to the nutritional requirements for human health and to food security since it contains enough concentrations of proximate composition, minerals, and vitamins. The plant parts are used in traditional medicine for many human and animal healthcare purposes, including diarrhea, diabetes, wound healing, tonsillitis, evil eye, retained placenta, headache, eye disease, intestinal parasite, bloating, hepatitis, toothache, anthrax, malaria, urine retention, gastritis, stomach disorders, and snake bites. The chemical analysis revealed the presence of flavonoids, alkaloids, saponins, tannins, triterpenoids, sesquiterpene lactones, steroids, cardiac glycosides, oxalates, phytates, cyanogenic glycosides, and phenols. Additionally, various compounds such as vernolide, luteolin, vernodalol, vernoamyoside A, vernoamyoside B, isorhamnetin, glucuronolactone, and 1-Heneicosenol O-β-D-glucopyranoside were isolated. Some of the isolated compounds pharmacological activity was evaluated against some diseases and showed antioxidant, antibacterial, antifungal, antihelmintic, anticancer, and anti-inflammatory potencies. Thus, the review provides comprehensive information about ethnomedicinal value, nutritional composition, isolated classes of phytochemicals, and compounds, including an evaluation of the pharmacological activity of the isolated compounds of Vernonia amygdalina. A review with this much information could be extremely valuable for future research on developing innovative nutraceutical products.

1 Introduction

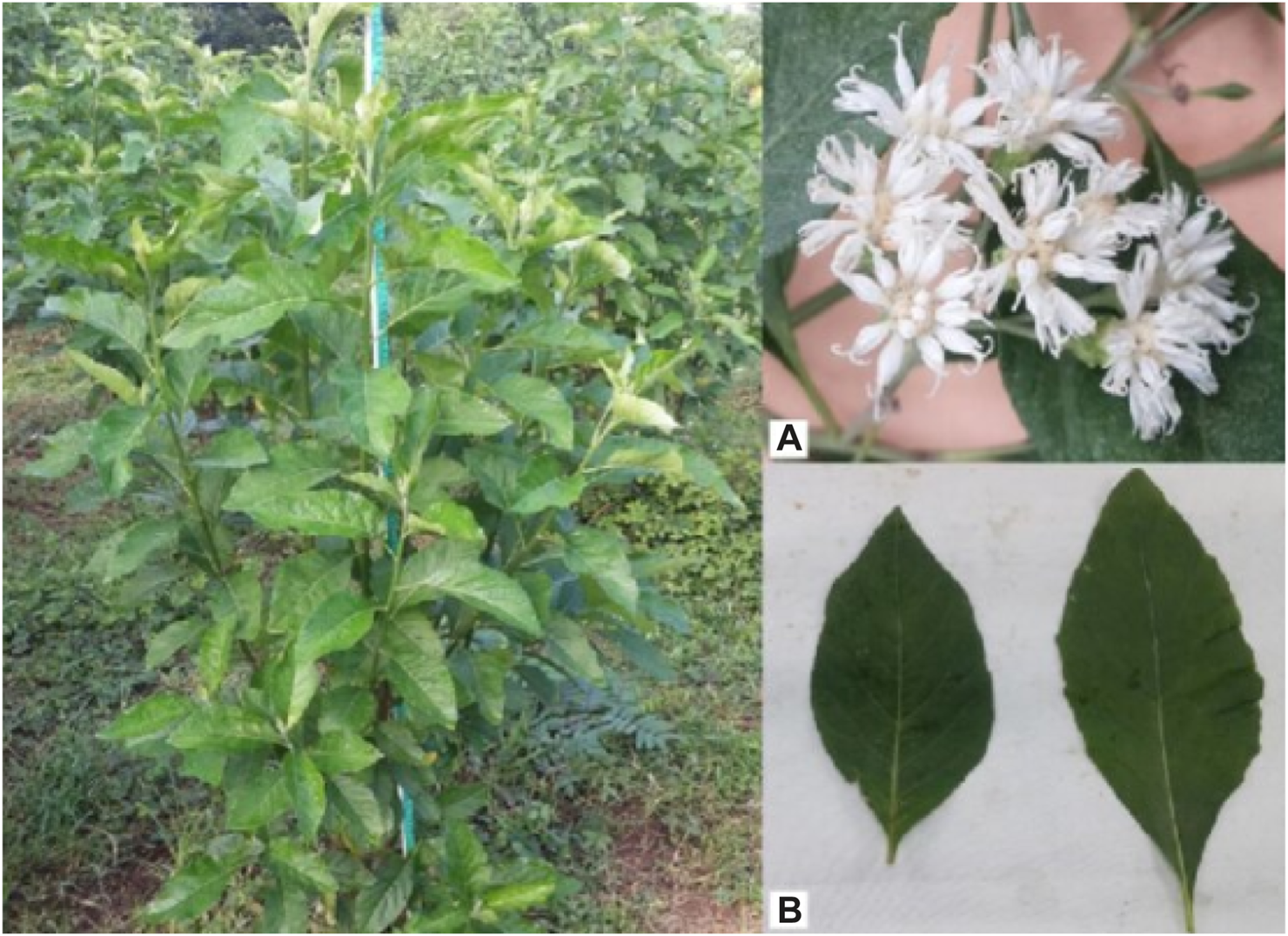

Vernonia amygdalina (VA) is a perennial shrub or small tree in the genus Vernonia of the Asteraceae family (Ijeh and Ejike, 2011). When completely grown, it can reach a height of roughly 23 feet. It has flaky, rough bark colored gray or brown (Echem and Kabari, 2013). The leaves are medium to dark green, oblong-lanceolate, usually measuring 10–15 cm in length and 4–5 cm in width. They have visible red veining, a tapering apex and base, an almost symmetric base, a complete or finely toothed margin, and a petiole that is typically very short but can reach 1–2 cm in length. Its little, creamy white, Thistle-like flower heads measure 10 mm in length. They are packed densely in axillary and terminal clusters to form enormous, flat clusters that have a lovely aroma and measure 15 cm in diameter (Ofori et al., 2013).

The herb is an indigenous African plant that thrives throughout most of sub-Saharan Africa as well as being widely spread in Asia (Echem and Kabari, 2013). It is widely grown in Yemen, Brazil, South Uganda, Ethiopia, Kenya, and Tanzania (Bhattacharjee et al., 2013), even though it is native to tropical Africa (Ijeh and Ejike, 2011; Nursuhaili et al., 2019). Naturally, the plant can be found in regions with 2,800 m of elevation and 750–2000 mm of annual rainfall, such as the edges of forests, the areas surrounding rivers and lakes, woodlands, and grasslands. It requires direct sunlight and prefers a humid environment. Although it may grow on any kind of soil, it favors humus-rich soils (Ofori et al., 2013).

It is probably the most widely used medicinal herb in the genus Vernonia (Ijeh and Ejike, 2011). Because of its bitter flavor, it is commonly referred to as “bitter leaf” and is used both medicinally and as a vegetable. The species’ secondary metabolites, which include saponins, tannins, alkaloids, and glycosides, are anti-dietary components. These constituents are the source of the bitter taste in this medicinal plant (Yeap et al., 2010; Danladi et al., 2018). Outside of bitter leaf, this medicinal plant is known by a variety of common names in different languages in different regions (for instance, “ebicha” (oromifa) (Bekele and Reddy, 2015), “grawa” (Amharic), and “vernonia tree” (English) (Wubayehu et al., 2018).

Numerous therapeutic herbs are known for their antibacterial (Degu et al., 2021a; Gonfa et al., 2022; Legesse et al., 2022; Asfaw et al., 2023b; Dagne et al., 2023), antifungal (Degu et al., 2020b), antiviral (Meresa et al., 2017; Tesera et al., 2022), anti-parasitic (Basha et al., 2018; Muluye et al., 2021), anti-hypertensive (Fekadu et al., 2017), anti-asthmatic (Sisay et al., 2020), insect repellent (Degu et al., 2020a), and so on effects. They are utilized as a food source in addition to their medical properties (Olowoyeye et al., 2022). In history, bitter leaf has been utilized for generations in Africa for both food and medicinal purposes. The plant has a wide spectrum of uses in African traditional medicine and has been used in the management and treatment of a number of health conditions (Ijeh and Ejike, 2011). There have been several previous studies on the traditional medicinal value (Asfaw et al., 2023a), nutritional content (Okolie et al., 2021), isolation of different classes of phytochemicals and compounds, and evaluation of their pharmacological activities (Habtamu and Melaku, 2018) of VA. The purpose of this review is to give current, evidence-based information about the medicinal role of the plant, its existing nutritional and phytochemical composition, and the pharmacological properties of the isolated substances. Thus, this review summarizes the current evidence which is as an updating work of the previous review (Yeap et al., 2010; Ijeh and Ejike, 2011). As a result, the current study provides a deep and updated knowledge on this therapeutic herb that could stimulate more research into pharmacopeia and the discovery of novel pharmaceuticals. Figure 1 is a representative image of the species VA with its leaf and flower.

FIGURE 1

Vernonia amygdalina plant (left), flowers (A), top right) and leaves (B), bottom right) (TjhiaA et al., 2018).

2 Methodology

The data on the nutritional makeup, discovered phytochemicals and compounds and their pharmacology, and traditional therapeutic efficacy of VA have been extracted from research published articles. The relevant various ethnobotanical publications and laboratory-based studies regarding the plant were looked at in order to gather relevant data on the study area. Using key words like VA, nutritional composition, isolated phytochemicals, isolated compounds, pharmacological activities, traditional uses, leaf, root, stem, flower, bark, method of preparation, and application, an exhaustive online search was conducted using the databases of Google Scholar, PubMed, Science Direct, Wiley, Elsevier and the Sci-Hub website. These terms were used separately or in combination. In order to tabulate the accessed data, an appropriate format for data gathering was established. This review included only research articles, master’s theses, and doctoral theses published in English that offered complete information.

3 The dietary composition and importance of Vernonia amygdalina

Due to its bitterness, VA can be used as a bittering agent (spice) and as an antimicrobial agent in beer production. Leaves are used to prepare bitter leaf soup (‘Onugbo’, a popular Nigerian dish) (Nursuhaili et al., 2019) as an appetizer and as a digestive tonic. The leaves and shoots are regarded as good fodder for goats (Okeke et al., 2015). The bitter leaf meal, given with drinking water, also numerically enhanced the growth rate of the birds (Nwogwugwu et al., 2015). In Ethiopia, it is used to make honey wine called ‘Tej’ (Nursuhaili et al., 2019) and as hops in preparing ‘tella’ beer (Shewo and Girma, 2017).

The leafy part of VA contributes greatly to the nutritional requirement for human health and to food security since it contains enough concentrations of proximate composition (Usunomena and Ngozi, 2016). The high concentration value of protein, dry matter, crude fiber, ash, minerals (sodium, potassium, calcium, magnesium, zinc, and iron), and ash in the leaves of the plant presented it as excellent sources of food (Oboh, 2006; Offor, 2014; Agbankpé et al., 2015; Okeke et al., 2015; Usunomena and Ngozi, 2016; Olusola and Olaifa, 2018; Olumide et al., 2019). Additionally, numerous studies also revealed different concentrations of protein (including essential amino acids), moisture, carbohydrates, ash, and fat within the leaves (Nwaoguikpe, 2010; Ogunnowo and Alao-Sanni, 2010; Ugwoke et al., 2010; Momoh et al., 2012; Yakubu et al., 2012; Omoyeni et al., 2015; Udochukwu et al., 2015; Usunomena and Ngozi, 2016; Etta et al., 2017; Olumide et al., 2019).

A study on micronutrients, macronutrients, and minerals obtained a concentration difference in which magnesium, copper, and lead were found to be high in fresh leaves and calcium, ash, fiber, lipid content, and iron were high in dried leaves (Garba and Oviosa, 2019). The leaf also has oil (Biru et al., 2022), starch (Okeke et al., 2015), and iodine (Ojimelukwe and Amaechi, 2019). Moreover, the leaf contains vitamins like vitamin A, vitamin C (ascorbic acid), vitamin E, vitamin B1, vitamin B2, niacin (Nwaoguikpe, 2010; Dafam et al., 2020), and carotenoid (Ejoh et al., 2005). The nutritional composition of the leaves and their corresponding literature is summarized in Table 1.

TABLE 1

Nutritional composition of Vernonia amydalina leaves.

The quantitative proximate evaluation of the leaf extract showed that it incorporates carbohydrates (37%), proteins (28.2%), fats (5.5%), crude fiber (11.6%), moisture content (8.4%), and ash content (9.3%) (Ali et al., 2020). The leaves had an 83.0% moisture content (dry matter: 17.02%), a 1.30% protein content, and a 0.50% ash content in another study on fresh green leaves. Based on the fresh weight of the leaves, the mineral content was 61.55 μg/g, 8.2 × 10−3 μg/g, 4.71 μg/g, and 1.13 μg/g of phosphorus, selenium, iron, and zinc, respectively (Oboh and Masodje, 2009). This result was consistent with the study by Okolie et al. (2021), which found that the quantified results for sodium, magnesium, phosphorus, potassium, iron, and zinc were 180.36 mg/100g, 162.54 mg/100g, 27.8 mg/100g, 949.35 mg/100mg, 1.13 mg/100g, and 0.48 mg/100g, respectively. Once again according to Okolie et al. (2021), the analysis of vitamins B1, B2, B3, and E yielded values of 0.16 mg/100g, 0.22 mg/100g, 0.15 mg/100mg, and 0.32 mg/100g, respectively.

Zinc (14.23 mg/kg), iron (322 mg/kg), phosphate (33.25 mg/kg), copper (19.50 mg/kg), chromium (3.75 mg/kg), cadmium (4.99 mg/kg), sodium (483.06 mg/kg), potassium (627.98 mg/kg), magnesium (6,813 mg/kg), calcium (12,641.76 mg/kg), and zinc (14.23 mg/kg) were found in the powdered leaves (Usunobun and Okolie, 2015). Vitamins E and A, starch (only the stem), protein, ash, fat, zinc, iron, copper, ascorbic acid, thiamin, riboflavin, and nicotinamide are abundant in the stems and roots (Okeke et al., 2015; Ojimelukwe and Amaechi, 2019). Additionally, the proximal composition of ash, moisture, crude fat, crude fiber, protein, and carbohydrate was found in another study that intends to explore the nutritional value of the stem, root, and seed (Okeke et al., 2015; Adebayo et al., 2019). Moreover, vitamin C, vitamins B1 and B2, sodium, potassium, calcium, magnesium, iron, zinc, and manganese are present in the seeds (Adebayo et al., 2019).

These results show that VA is a rich source of important nutrients, with varying quantities throughout various trials. There are numerous reasons for the variance in the outcome. For example, the nutritional composition of the VA varies according on the kind of soil, environmental conditions, and by geographic locations (Okolie et al., 2021; Olowoyeye et al., 2022). There was difference in the content of nutritious components between dried and fresh leaves as well. Most of the proximate ingredients’ concentrations increased noticeably with drying. Drying significantly increased the ash, fiber, and lipid contents, which improved from 2.56%, 1.62%, and 0.62% in the fresh sample to 11.20%, 4.02%, and 2.64% in the dried sample, respectively. The results of this study’s mineral analysis showed that calcium and iron were high in the dried sample whereas magnesium, copper, and lead were high in the fresh sample (Garba and Oviosa, 2019).

3.1 Effect of different processing methods on nutritional composition of bitter leaf

Some proximate, calcium, iron, potassium, and vitamin C are lost when processed traditionally, which includes boiling, squeeze washing, and salting, or squeeze washing and boiling (Tsado et al., 2015). Nutrients are lost when leaves are de-bittered to make them more palatable; conversely, when leaves are boiled in water (without being squeezed) to increase beta-carotene concentration, water-soluble vitamins are lost (Nkechi, 2023). A 2016 study by Agomuo et al. (2016) found that squeezing bitter leaves with palm oil improves nutrient retention, which may be a loss-preventing solution. The study by Yakubu et al. (2012) found that different processing methods, like soaking in water for an entire night, blanching, and abrasion with and without salt (Nacl), reduced the antioxidant capacity, protein content, and moisture content of the leaves. Blanching and abrasion without salt resulted in a decrease in fat content, but soaking and abrasion with salt enhanced it. Soaking resulted in reduced crude fiber content, whereas salt abrasion increased it. Abrasions increased the contents of the ash, whereas blanching and soaking significantly reduced them. Additionally, the vegetable’s mineral, tannin, and phytate contents were significantly reduced by the processing techniques of overnight soaking, blanching, and abrasion (Yakubu et al., 2012).

In a different study, the amount of nutrients and antinutrients (phytate and tannin) in the leaf significantly decreased when it was abraded. It results in a large decrease in the proximate and mineral composition with the exception of magnesium and carbohydrates, which saw a considerable rise and no significant change, respectively (Oboh, 2006). Therefore, the nutrient content of VA is reduced when they are abraded to remove the bitter flavor during soup and other meal preparation. Moreover, study on fresh leaf and on the leaf subjected to spontaneous fermentation for 5 days at room temperature revealed a significant amount of mineral content that appeared stable after fermentation. However, significant losses in vitamins and a noticeable rise in ash and fiber content were observed (Ifesan et al., 2014).

Vital minerals and nutrients, which are present in the VA, are beneficial to the body. Nevertheless, the concentrations of Pb, Cr, Zn, Co, and Ni in VA leaves are higher than those recommended by the WHO (Ssempijja et al., 2020); therefore, these materials may need to be reduced or removed before feeding. Various methods, such as blanching and abrasion, are used to lessen the anti-nutritional components of bitter leaves, such as tannin and phylate (Yakubu et al., 2012). Few attempts have been made to preserve this vegetable, despite its excellent nutritional value. Therefore, to prevent any changes in flavor, color, or nutritional content, it is imperative that dried leaves be packaged appropriately (Degu et al., 2021b) and kept at the proper temperature when consumed out of their extremely fresh form. VA maintained at 4°C preserves more of its nutritional and therapeutic characteristics than when stored at −20°C, according to a study on the effect of preservation on two different types of bitter leaves (Tonukari et al., 2015).

4 Ethnomedicinal uses

VA has a wide range of traditional medical applications worldwide. The plant is used in traditional and herbal medicine to treat a variety of conditions, including intestinal worms, headaches, bloating, malaria, urinary problems, herpes, athletes foot, blood clotting, dyspepsia, menstrual pain, gout, wounds, tonsillitis, evil eye, skin infections, and other conditions affecting humans and animals (Abebe, 2011; Jima and Megersa, 2018; Girma et al., 2022; Mekonnen et al., 2022). According to reviewed ethnobotanical studies, the leaf is the part most frequently claimed for various diseases, followed by the root, shoot, stem, and seed. These medicinal plants are used either separately or in combination to cure a variety of diseases. Table 2 displays the plant parts, ethno-medicinal claims, and method of preparation, along with the application site.

TABLE 2

| Ethnomedicinal uses | part(s) | Method of preparation and application | References |

| Abdominal pain (H) | Leaf | Preparation: grinding and, dissolving with water | Getaneh and Girma (2014) |

| Application: drinking | |||

| Abdominal pain (L) | Seed | Preparation: blending the seeds and dissolve with water and then filtration | Hassen et al. (2021) |

| Application: oral or intranasal | |||

| Ameba and Giardia (H) | leaf | Preparation: Crushing leaves and soaking in honey | Cheklie (2020) |

| Application: oral | |||

| Anthrax (H) | Leaf | Preparation: blending the leaves with Justicia schimperiana, Croton macrostachyus, Teclea nobilis, and Achyranthes aspera leaves | Kassa et al. (2016) |

| Application: Through left side intranasal and left ear | |||

| Anthrax (L) | leaf and Root | Preparation: crushing the leaf and root followed by dissolving with water | Haile (2022) |

| Application: orally to Cattles | |||

| Ascariasis | Leaf | Preparation: pulverizing leaves | Tsegay et al. (2019) |

| Application: oral consumption | |||

| Athletes foot (H) | Leaf | Preparation: crushing and squeezing | Abebe (2011), Amsalu (2020) |

| Leaf | Application: topical | ||

| Bladder distention | Leaf | Preparation: Pulverizing the leaf in water | Wubetu et al. (2017) |

| Application: oral | |||

| Bloating (H) | Leaf | Preparation: crushing fresh leaves | Chekole et al. (2015) |

| Application: orally with water | |||

| Bloating (L) | Leaf | Preparation: crushing fresh leaves and combined with water | Lulekal et al. (2014), Beyi (2018), Molla (2019), Kindie (2023) |

| Application: orally to the cattle | |||

| Leaf | Preparation: Mashing the leaves and blending with Justicia schiperiana and salt | Kassa et al. (2016) | |

| Application: orally to cattle | |||

| Bloating and malaria (H) | Leaf | Preparation: crushing fresh leaves and combining with water | Girma et al. (2022), Mekonnen et al. (2022) |

| Application: orally | |||

| Bloating and urine retention (L) | Leaf | Preparation: squeezing and mixing with water | Amde (2017), Melkamu (2021) |

| Application: orally to the cattle in the morning and at night until recovery | |||

| Blood clotting (H) | Leaf | Not described | Girma et al. (2022) |

| Dandruff (H) | Leaf | Preparation: freshly pounding to obtain creamy texture | Chekole et al. (2015) |

| Application: topically on the affected area | |||

| Diarrhea (H) | Leaf | Preparation: Chopping the leaf, combining with coffee grounds and blending with butter | Kindie (2023) |

| Application: orally | |||

| Leaf and seed | Preparation: combining fresh leaves with pounded seeds and blending with butter | Lulekal et al. (2014) | |

| Application: orally | |||

| Leaf and seed | Preparation: combining fresh leaves with pounded seeds and blending with butter | Beyi (2018) | |

| Application: orally | |||

| Dyspepsia (H) | Leaf | Not described | Girma et al. (2022) |

| Evil eye (H) | Root | Preparation: Drying and grinding the root in to powder | Gebeyehu (2020) |

| Application: inhaling the smoked powder | |||

| Evil spirit (H) | Shoot | Preparation: Pulverizing and combining with water | Wendimu et al. (2021) |

| Application: placing in a beaker before being displayed in front of the room. When an evil spirited person enters to the home, the water in the beaker falls and the patient is identified | |||

| Expelling leeches (L) | Leaf | Preparation: Crushing and squeezing the fresh leaves | Abrha et al. (2020) |

| Application: oral ingestion | |||

| Febrile illness (H) | Leaf | Preparation: boiling a fresh leaf in water | Tahir et al. (2021) |

| Application: fumigating the steam | |||

| Febrile malaria and helminthiasis | Leaf | Preparation: Maceration with water | Tuasha et al. (2018) |

| Application: orally | |||

| Gastro-intestinal disorder (H) | Leaf | Preparation: crushing | Asfaw et al. (2021), Asfaw et al. (2023a) |

| Application: orally | |||

| Gout (H) | Leaf | Preparation: boiling the leaves with water | Chekole (2017) |

| Application: Fumigating through oral, nasal, and dermal | |||

| Headache (H) | Leaf | Preparation: crushing ten leaves | Jima and Megersa (2018) |

| Application: applying to the head for 3 days | |||

| Headache and eye disease (H) | Leaf | Preparation: Pulverizing, and powdering | Assefa et al. (2021) |

| Application: fumigating the smoke in the nose and mouth | |||

| Herpes (H) | Leaf | Preparation: Drying, pulverizing and powdering | Abebe (2011) |

| Application: fumigating through the nose and mouth | |||

| Impotency (H) | Root | Preparation: concocting of fresh root | Chekole et al. (2015) |

| Application: Drinking with “tella” | |||

| Intestinal parasite (H) | Root (H, L) | Preparation and Application: Fresh plant consumed orally | Bogale et al. (2023) |

| Leaf | Preparation: decocting | Jima and Megersa (2018) | |

| Application: consuming three to seven leaves together with one cup of coffee for adults and half for children | |||

| Leaf | Preparation: extracting a juice | Kindie et al. (2021) | |

| Application: one cup orally | |||

| Leaf | Preparation: extracting a juice | Amsalu et al. (2018) | |

| Application: one cup orally | |||

| Intestinal parasite(L) | Leaf | Preparation: extracting a juice and combining with salt and “local beer” | Kindie (2023) |

| Application: fed to the animal | |||

| Leaf | Preparation: extracting a juice and combining with salt and “local katikala” | Beyi (2018) | |

| Application: fed to the animal | |||

| Intestinal parasites, abdominal pain, malaria, gastritis, retained placenta (H) | Leaf and steam | Preparation and Application: Infusion taken orally | Teka et al. (2020) |

| Intestinalparasites (H) and Stomach problem (L) | Leaf | Preparation: crushing fresh leaves and combining with water | Kebebew and Mohamed (2017) |

| Application: filtering and drinking | |||

| Jaundice (H) | Leaf | Preparation: pounding fresh or dry leaves | Kassa et al. (2016) |

| Application: topically with butter | |||

| Leaf | Preparation: pulverizing and combining with water | Beyi (2018) | |

| Application: filtering and drinking | |||

| Leaf | Preparation: Crushing and combining fresh leaf with water | Kindie (2023) | |

| Application: filtering and drinking | |||

| Leeches (L) | Leaf | Preparation: blending pounded leaves with Premna schimperi, Nicotiana tabacum, Calpurnia aurea, and Croton macrostachyus | Kassa et al. (2016) |

| Application: orally feeding the cattle | |||

| Malaria (H) | Leaf | Preparation: Combining Ruta chalepensis leaves combined with crushed VA leaves | Amde (2017), Melkamu (2021) |

| Application: serving as one cup as a beverage for three to 5 days, in the morning with cold water | |||

| Roots/Leaf | Preparation: and crushing and mixing with water | Girmay and Teshome (2017) | |

| Application: orally | |||

| Leaf and root | Preparation: crushing, mixing with water and filtering either the fresh roots or leaves | Molla (2019) | |

| Application: drinking | |||

| Menstrual pain (H) | Leaf | Preparation: Crushing, boiling, and combing with honey in water | Tassew (2019) |

| Application: one tea cup taken orally (each day for 3 days) | |||

| Neck swelling (L) | Leaf | Preparation: Squeezing | Abrha et al. (2020) |

| Application: apply topically | |||

| Nematodes (H) | Leaf | Preparation and Application: Orally | Agisho et al. (2014) |

| Retained placenta (L) | Root | Preparation: crushing and mixing the fresh root with cold water | Lulekal et al. (2014) |

| Application: allowing the animal to consume it orally | |||

| Snake bite (H) | Leaf | Preparation: Crushing the leaves | Amde (2017), Melkamu (2021) |

| Application: washing the patient’s body, or area that has been infected | |||

| Stomach ache and worm expulsion (H and L) | Leaf and root | Preparation: Combining the root and leaves combined to make a beverage | Wondimu et al. (2007) |

| Application: orally | |||

| Stomach disorder (L) | leaf | Preparation: Crushing and soaking in water | Cheklie (2020) |

| Application: one bottle orally | |||

| Stomachache (H) | Leaf | Preparation: Squeezing leaves | Birhan et al. (2017) |

| Application: Consume orally | |||

| Leaf | Preparation: crushing, squeezing, and mixing fresh leaf with water | Kindie (2023) | |

| Application: orally | |||

| Leaf | Preparation and Application: crushing, squeezing, and combining with water then decanted | Amsalu et al. (2018) | |

| Application: Orally | |||

| Leaf | Preparation: Crushing and mixing with water | Teklehaymanot et al. (2007) | |

| Application: orally | |||

| Stomachache and malaria(H) | Leaf | Preparation: Blending fresh leaves with Rumex nervosus and Justicia schimperiana leaves. Then, squeezing together with water and the resulting juice | Wendimu et al. (2021) |

| Application: orally | |||

| Tapeworm and Ascaris (H) | Leaf | Preparation: crushing and mixing with water | Teklehaymanot et al. (2007) |

| Application: orally | |||

| Tonsilitis (H) | Root | Preparation: crushing and mixing the root with salt | Gebeyehu (2020) |

| Application: orally | |||

| Toothache (H) | leaf | Preparation and Application: chewing of the leaves | Amenu (2007), Getaneh and Girma (2014) |

| Urinary problems (H and L) | Leaf | Preparation: Blending crushed fresh leaf of with leaf of Eucalyptus globulus (concoction) | Molla (2019), Mekonnen et al. (2022) |

| Application: orally | |||

| Urinating problem and bloating (H and L) | Leaf and shoot | Preparation: crushing and pounding fresh leaf | Abdela and Sultan (2018) |

| Application: orally | |||

| Vomiting and stomach-ache (H) | Leaf | Preparation: Crushing one feast of leaves cut from seven different parts, with small amount of water followed by filtering | Amsalu (2020) |

| Application: Orally drinking | |||

| Worms, malaria, fever and, indigestion | Leaf and root | Preparation: decoction | Tugume and Nyakoojo (2019) |

| Application: drinking | |||

| Wound (H) | leaf | Preparation: Crushing one spoonful powder of leaf | Cheklie (2020) |

| Application: Dressing on the wound | |||

| Leaf | Preparation: crushing | Teka et al. (2020) | |

| Application: topical application | |||

| Leaf | Preparation: crushing fresh leaves | Wendimu et al. (2021) | |

| Application: topical application to a wound to halt bleeding |

Plant parts, ethno-medicinal claims, and method of preparation, along with the application site.

It has been demonstrated that the synergistic effects of combining this medicinal plant part with other plant parts, local preparations, and animal byproducts in the formulation of herbal medicines boost the effectiveness of the cures. The leaf, for example, is combined with butter and coffee seeds (Beyi, 2018; Kindie, 2023), leaves of Ruta chalepensis (Melkamu, 2021), leaves of Eucalyptus globules (Molla, 2019), leaves of Teclea nobilis, Croton macrostachyus, Justicia schimperiana, and Achyranthes aspera are pounded together and administered through the left ear and left noisetril (Kassa et al., 2016); and with local “katukala” and salt (Beyi, 2018) as treatments for diarrhea, malaria, urinary issues, anthrax, and internal parasites, respectively. Furthermore, fresh root infused with “tella” is utilized as an impotence cure (Chekole et al., 2015).

5 Phytochemical constituents

5.1 Phytochemical classes

Numerous phytochemicals from VA with a variety of pharmacological and biochemical effects were investigated such as alkaloids, glycosides, sesquiterpene lactones, steroids, flavonoids, proanthocyanidins, tannins, terpenoids, phenylpropanoids, resins, lignans, furocoumarines, naphthodianthrones, proteins, and peptides (Erasto et al., 2006; Senthilkumar et al., 2018; Tian et al., 2023). For instance, phytochemical screening of ethanol and aqueous leaf extracts revealed the presence of flavonoids, alkaloids, saponins, tannins, triterpenoids, steroids, and cardiac glycosides (Asaolu et al., 2010; Usunomena and Ngozi, 2016). Furthermore, the presence of phytate, oxalate, cyanogenic glycosides, anthraquinone (Ugwoke et al., 2010; Udochukwu et al., 2015), and phenol (Asaolu et al., 2010; Ali et al., 2019) have been revealed (Table 3).

TABLE 3

Phytochemical classes isolated in Vernonia amygdalina plant-parts.

According to Ali et al. (2019), the plant leaves’ aqueous extract contained 27 mg/g of saponins, 46 mg/g of alkaloids, 122 mg/g of flavonoids, 17 mg/g of terpenoids, 12 mg/g of tannins, 48 mg/g of steroids, and 36 mg/g of phenols. In another study, the ethanol extract contained tannins (99 mg/g), flavonoids (70 mg/g), saponins (64 mg/g), phenols (36 mg/g), and alkaloids (32 mg/g) (Lyumugabe Loshima et al., 2017). In accordance with the Imohiosen et al. (2021) findings, bitter leaf has 139 mg/g of alkaloids, 180 mg/g of flavonoids, 60 mg/g of saponin, 2.3 mg/g of oxalate, and 167 mg/g of phytate. A further investigation reported 305 mg/g flavonoids, 104 mg/g phytate, 6 mg/g saponin, 1.7 mg/mL tannin, and 20 mg/mL alkaloids (Olumide et al., 2019). As mentioned above, the outcomes of many investigations demonstrated notable chemical variations between plant preparations or extracts, both in terms of kind and quantity.

As already stated, alkaloids, tannins, phenolics, saponins, and other significant groups of chemicals were present in various amounts, as demonstrated by the screening and quantification tests. These phytochemicals have been found to have a wide variety of biological activities, showing the plant’s potential as a medicine. Alkaloids, flavonoids, terpenoid, phenolics, tannin are known by their antimicrobial activity (Usunomena and Ngozi, 2016), antioxidants (Erdman et al., 2007), prevention and therapy of several diseases (Rabi and Bishayee, 2009), free radical scavengers and strong anticancer activities (Ugwu et al., 2013), potentials antiviral (Cheng et al., 2002) and anticancer activities (Narayanan et al., 1999), respectively. Consequently, the existence of these and other phytochemicals in VA could account for their use as medicine.

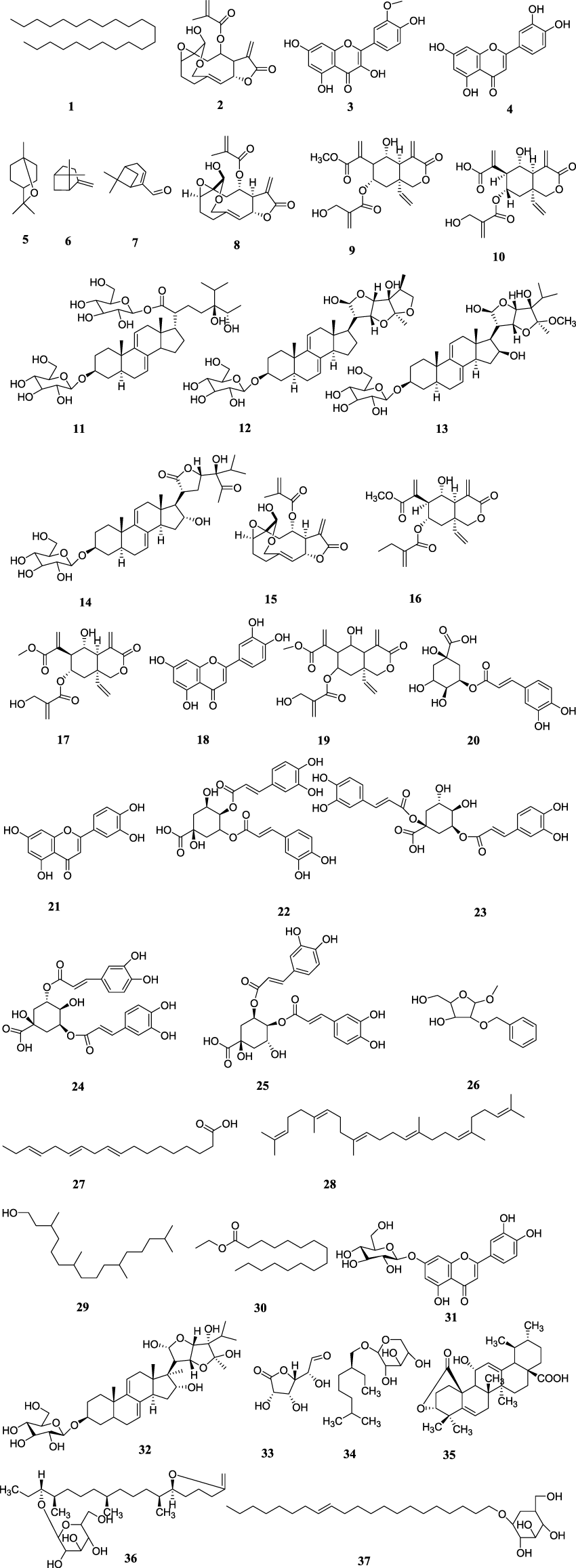

5.2 Compounds isolated from Vernonia amygdalina

Medicinal plants are the primary source of a broad variety of chemical structures that aid in the development of novel therapeutic medications. Numerous compounds have been identified from the leaves, flowers, stems, and other parts of VA through different NMR techniques and GC-MS analysis. The list of compounds isolated from Vernonia amygdalina along with their compound name, plant part and literature references are presented (Table 4; Figure 2).

TABLE 4

| Compound name | Str. No | Plant parts | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|

| Tricosane | 1 | F | Habtamu and Melaku (2018) |

| Vernolid | 2 | F | Habtamu and Melaku (2018) |

| Isorhamnetin | 3 | F | Habtamu and Melaku (2018) |

| Luteolin | 4 | F | Habtamu and Melaku (2018) |

| 1, 8 Cineole | 5 | L | Asawalam and Hassanali (2006) |

| beta-Pinene | 6 | L | Asawalam and Hassanali (2006) |

| Myrtenal | 7 | L | Asawalam and Hassanali (2006) |

| Vernolide | 8 | L | Abay et al. (2015) |

| vernodalol | 9 | L | Abay et al. (2015) |

| vernodalinol | 10 | L | Luo et al. (2011) |

| vernoamyoside A | 11 | L | Quasie et al. (2016) |

| Vernoamyoside B | 12 | L | Quasie et al. (2016) |

| Vernoamyoside C | 13 | L | Quasie et al. (2016) |

| Vernoamyoside D | 14 | L | Quasie et al. (2016) |

| Vernolide | 15 | L | Erasto et al. (2006) |

| Vernodalol | 16 | L | Erasto et al. (2006) |

| Epivernodalol | 17 | L | Oluyege (2019) |

| Luteolin | 18 | L | Djeujo et al. (2023) |

| Vernodalol | 19 | RT | Djeujo et al. (2023) |

| 5-O-caffeoylquinic acid | 20 | L | Nowak et al. (2022) |

| luteolin hexoside | 21 | L | Nowak et al. (2022) |

| 3,4-O-dicaffeoylquinic acid | 22 | L | Nowak et al. (2022) |

| 1,5-O-dicaffeoylquinic acid | 23 | L | Nowak et al. (2022) |

| 3,5-O-dicaffeoylquinic acid | 24 | L | Nowak et al. (2022) |

| 4,5-O-dicaffeoylquinic acid | 25 | L | Nowak et al. (2022) |

| Ethyl-2-O-benzyl-d-arabinofuranoside | 26 | L | Oladunmoye et al. (2019) |

| -9, 12, 15, octadecatrienoic acid | 27 | L | Oladunmoye et al. (2019) |

| Squalene | 28 | L | Oladunmoye et al. (2019) |

| Phytol | 29 | L | Oladunmoye et al. (2019) |

| Hexadecanoic acid ethyl ester | 30 | L | Olusola-Makinde et al. (2021) |

| luteolin-7-O-gluc-glucopyranoside (cynaroside) | 31 | L | Nguyen et al. (2021) |

| Vernonioside V | 32 | L | Nguyen et al. (2021) |

| Glucuronolactone | 33 | ST | IfedibaluChukwu et al. (2020) |

| 10-Geranilanyl-O-β-D-xyloside | 34 | ST | IfedibaluChukwu et al. (2020) |

| 11α-Hydroxyurs-5,12-dien-28-oic acid-3α,25-olide | 35 | ST | IfedibaluChukwu et al. (2020) |

| 6β,10β,14β-Trimethylheptadecan-15α-olyl-15-O-β-D-glucopyranosyl1,5β-olide | 36 | ST | IfedibaluChukwu et al. (2020) |

| 1-Heneicosenol O-β-D-glucopyranoside | 37 | ST | IfedibaluChukwu et al. (2020) |

List of compounds isolated from Vernonia amygdalina.

F: flower, ST: stem, L: leaf, RT: root, Str No: structure number; Ref: Reference.

FIGURE 2

Chemical structures of isolated compounds from Vernonia amygdalina.

6 Biological activity of isolated compounds

People all over the world, including modern medicine professionals, have used bitter leaf as traditional medicine. Common illnesses are treated with a variety of plant parts, including the leaves, roots, seeds, shoots, and stems (Ugbogu et al., 2021). Nowadays, phytochemicals from plants are used in herbal medicine; hence, it is essential to know about and explain the compounds present in medicinal plants in order to ensure their successful utilization and preservation. To date, not many investigations have been conducted to evaluate the pharmacological activity of the isolated chemicals from VA using a variety of in vitro and/or in vivo techniques. Few studies have reported the anti-inflammatory (Nguyen et al., 2021), antioxidant (Erasto et al., 2007), antibacterial, antifungal (Erasto et al., 2006), anti-cancer (Luo et al., 2011), anti-diabetic, and anti-helminthic (IfedibaluChukwu et al., 2020) activities of isolated compounds from VA.

Vernolide and Vernodalol have antioxidant (Erasto et al., 2007; Djeujo et al., 2023), antibacterial (Erasto et al., 2006; Habtamu and Melaku, 2018), and antifungal (Erasto et al., 2006) properties. Vernodalol’sin silico pharmacokinetics and toxicity profile, as reported by Djeujo et al. (2023), indicate that the compound could be a good drug candidate due to its appropriate pharmacokinetic characteristics. Glucuronolactone, 6β,10β,14β-Trimethylheptadecan-15α-olyl-15-O-β-D-glucopyranosyl1,5β-olide, Vernodalinol, and Vernonioside V have anti-helmintic healing (IfedibaluChukwu et al., 2020), anti-diabetic potency (IfedibaluChukwu et al., 2020), inhibition of breast cancerous cells (Luo et al., 2011), and inflammation-treating ability (Nguyen et al., 2021), respectively.

Four other isolated compounds, Vernoamyoside A, B, C, and D, demonstrated an anti-inflammatory effect by inhibiting the production of nitric oxide when tested in vitro in LPS-induced RAW264.7 macrophages (Quasie et al., 2016). However, luteolin-7-O-gluc-glucopyranoside, also known as cynaroside, did not show any effects. Luteolin (Djeujo et al., 2023), isorhamnetin (Habtamu and Melaku, 2018),6β,10β,14β-Trimethylheptadecan-15α-olyl-15-O-β-D-glucopyranosyl1,5β-olide, 1-Heneicosenol O-β-D-glucopyranoside, 11α-Hydroxyurs-5,12-dien-28-oic acid-3α,25-olide, 10-Geranilanyl-O-β-D-xyloside, and Glucuronolactone (IfedibaluChukwu et al., 2020) also showed antioxidant efficacy. The toxicity and pharmacokinetics study on luteolin indicates that the compound is safe and has adequate pharmacokinetic good manners (Djeujo et al., 2023). Isorhamnetin also had antibacterial activity with an inhibition zone of 9–14 mm against gram-positive and gram-negative bacteria at a 1 mg/mL dose (Habtamu and Melaku, 2018) (Table 5).

TABLE 5

| Isolated compounds | Pharmacological activities | References |

|---|---|---|

| Vernolide | Antioxidant activity (IC50 = 0.04 mg/mL for DPPH scavenging capabilities) | Erasto et al. (2007) |

| Antibacterial activity (zone of inhibition at 1 mg/mL dosage range from 10 to 19 mm) | Habtamu and Melaku (2018) | |

| It exhibited bactericidal activity against five strains of Gram-positive bacteria but was ineffective against strains of Gram-negative bacteria. The antifungal activity demonstrated with LC50 values of 0.2, 0.3, and 0.4 mg/mL against Penicillium notatum, Aspergillus flavus, Aspergillus niger, and Mucor hiemalis, respectively. However, it is ineffective against Fusarium oxysporum | Erasto et al. (2006) | |

| Vernodalol | Bactericidal activity against five g-positive bacteria while lacking efficacy against the gram-negative strains. The antifungal activity was moderate inhibitions with LC50 values of 0.2, 0.3 and 0.4 mg/mL against Penicillium notatum, Aspergillus flavus, Aspergillus niger and Mucor hiemalis, respectively.But, ineffective against Fusarium oxysporum | Erasto et al. (2006) |

| Anti-cancer (inhibited HT-29 cell viability with IC50 of 5.7 µM) and antioxidant activity with a scavenger effect comparable to ascorbic acid | Djeujo et al. (2023) | |

| Antioxidant activities as manifested through their DPPH scavenging properties (IC50 = 0.03 mg/ml) | Erasto et al. (2007) | |

| Vernodalinol | At 25 and 50 μg/mL, vernodalinol reduced the proliferation of breast malignant cells (DNA synthesis) by 34% and 40%, respectively | Luo et al. (2011) |

| Vernonioside V | Anti-inflammatory effect: TNF-a, IL-6, and IL-8 inflammatory cytokine production in LPS-activated Raw 264.7 was suppressed at a dose of 30 mg/mL | Nguyen et al. (2021) |

| Vernoamyoside D | Anti-inflammatory effect: In vitro, LPS-induced RAW264.7 macrophages at 50 µM showed a 37.6% inhibition of nitric oxide production, while the positive control (N-monomethylL-arginine) exhibited a 57.34% inhibition | Quasie et al. (2016) |

| Vernoamyoside C | Anti-inflammatory effect: In vitro, LPS-induced RAW264.7 macrophages at 50 µM showed a 50.0% inhibition of nitric oxide production, while the positive control (N-monomethylL-arginine) exhibited a 57.34% inhibition | Quasie et al. (2016) |

| Vernoamyoside B | Anti-inflammatory effect: In vitro, LPS-induced RAW264.7 macrophages at 50 µM showed a 24.5% inhibition of nitric oxide production, while the positive control (N-monomethylL-arginine) exhibited a 57.34% inhibition | Quasie et al. (2016) |

| Vernoamyoside A | Anti-inflammatory effect: In vitro, LPS-induced RAW264.7 macrophages at 50 µM showed a 20.5% inhibition of nitric oxide production, while the positive control (N-monomethylL-arginine) exhibited a 57.34% inhibition | Quasie et al. (2016) |

| Luteolin-7-O-gluc-glucopyranoside (cynaroside) | On LPS-induced raw 264.7 cells, cynaroside did not exhibit an anti-inflammatory effect (cytokines did not decrease in raw 264.7 cells incubated with cynaroside) | Nguyen et al. (2021) |

| Luteolin | Anti-oxidant activity (Luteolin showed a 49% DPPH radical scavenging potential) | Habtamu and Melaku (2018) |

| Its strong capacity to scavenge free radicals and decrease HT-29 cell viability with an IC50 of 22.2 µM, respectively, indicate its antioxidant and anti-cancer properties | Djeujo et al. (2023) | |

| Isorhamnetin | Antioxidant capacity notably reduced lipid peroxidation by 80% and scavenged the DPPH radical by 94%. Moreover, it exhibited antibacterial activity against Gram positive and negative bacteria at a concentration of 1 mg/mL, with an inhibition zone ranging from 9 to 14 mm | Habtamu and Melaku (2018) |

| Glucuronolactone | Anti-helminthiceffect:witha total paralysis and death periods (in minutes) of 154, 85, and 53 against adult Eisenia foetida, the anti-helminthic efficacy was found to be less effective to that of the conventional treatment (albendazole) at 30, 50, and 70 mg, which was 17, 11 and 8 min. Moreover demonstrated a certain amount of anti-oxidation effect | IfedibaluChukwu et al. (2020) |

| 6β,10β,14β-Trimethylheptadecan-15α-olyl-15-O-β-D-glucopyranosyl1,5β-olide | Anti-diabetic potency showed a substantial decrease in blood glucose during therapy and a moderate anti-oxidation impact. Did not exhibit any anti-helminthic activity at dosages of 30, 50, or 70 mg against adult Eisenia foetida | IfedibaluChukwu et al. (2020) |

| 1-Heneicosenol O-β-D-glucopyranoside | At doses of 30, 50, and 70 mg, there was a slight antioxidation effect, but no anti-helminthic alters against adult Eisenia foetida | IfedibaluChukwu et al. (2020) |

| 11α-Hydroxyurs-5,12-dien-28-oic acid-3α,25-olide | At doses of 30, 50, and 70 mg, there was a slight antioxidation effect, but no anti-helminthic alters against adult Eisenia foetida | IfedibaluChukwu et al. (2020) |

| 10-Geranilanyl-O-β-D-xyloside | At doses of 30, 50, and 70 mg, there was a slight antioxidation effect, but no anti-helminthic alters against adult Eisenia foetida | IfedibaluChukwu et al. (2020) |

| Epivernodalol | LC50 of the compound was 22 ± 1.2 μg/mL against human melanoma skin cancer cells (HT-144 cell line) | Owoeye et al. (2010) |

The pharmacological activity of compounds isolated from Vernonia amygdalina.

7 General discussion

VA, commonly known as bitter leaf, is a medicinal plant that has been used traditionally for its therapeutic properties in many different cultures. This review paper provides emphasis on the plant’s possible health implications and therapeutic applications by offering a thorough investigation of its nutritional makeup, phytochemical components, and pharmacological activities. VA has been used traditionally for a variety of medical purposes, including but not restricted to its supposed antioxidant, antibacterial, anti-diabetic, anticancer, and anti-inflammatory effects. A wide range of conditions, from infectious to digestive issues, have been treated using the plant’s leaves, roots, seeds, and stems, demonstrating the plant’s adaptable therapeutic profile as a natural treatment. VA’s nutritional composition is noteworthy as it is rich in vital nutrients, vitamins, and minerals, all of which support the plant’s benefits for health. The biological activities and pharmacological characteristics of the plant are mostly determined by its phytochemical makeup, which includes bioactive substances including flavonoids, alkaloids, terpenoids, and phenolic compounds. By applying phytochemical compound isolation and analysis from VA, researchers have discovered a multitude of pharmacological characteristics linked to these chemicals. These highlight the plant’s potential as a source of bioactive molecules with therapeutic potential in a variety of health conditions. These include potential anti-inflammatory (Nguyen et al., 2021), antioxidant (Erasto et al., 2007), antibacterial, antifungal (Erasto et al., 2006), anti-cancer (Luo et al., 2011), anti-diabetic, and anti-helminthic effects.

8 Conclusion

The review provides compiled information about VA’s therapeutic role, nutritional and phytochemical makeup, and the pharmacological characteristics of its isolated compounds. Its chemical and nutritional content offers significant promise for the prevention and treatment of numerous illnesses, as well as for enhancing food security being an alternative nutrition. Different studies investigated various phytochemicals/compounds from VA that exhibit effective pharmacological activities. Moreover, several investigations have also shown that the leaves possess different concentrations of protein, moisture, carbohydrates, ash, fat, minerals, oils, and vitamins. However, the literature still show that not many researches’ have been conducted to date to evaluate the pharmacological activity of the extracted chemicals from VA using a variety of in vitro and/or in vivo techniques. Consequently, additional research is still needed to investigate the therapeutic potential of the phytochemicals and compounds within VA as well as to address many of the obstacles that still stand in the path of a meticulous scientific study about their medical uses. This is because an in-depth knowledge and characterization of the phytochemicals present in medicinal plants is essential for efficient usage. Thus, in order to maximize the benefits, bitter leaf’s safety profile and therapeutic potential must be thoroughly investigated and evaluated.

8.1 Limitations

Despite rigorous efforts to collect extensive data, the review’s analysis may have been limited in scope and depth due to the lack of some data points. The differences in the study designs, approaches, and reporting standards of the primary studies included in the review could have had an impact on the review’s results’ accuracy and consistency.

8.2 Future perspectives

Future studies should clarify the mechanisms of action of important phytochemicals, carry out clinical trials to support conventional claims, investigate possible synergistic effects of compounds, and create standardized formulations for therapeutic applications as Vernonia amygdalina research continues to develop. Through the use of multidisciplinary methods and cooperative projects, there is still hope for utilizing Vernonia amygdalina’s medicinal properties in contemporary health care.

Statements

Author contributions

SD: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal Analysis, Methodology, Writing–original draft, Writing–review and editing. AM: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal Analysis, Methodology, Writing–original draft, Writing–review and editing. ZA: Data curation, Validation, Writing–original draft, Writing–review and editing. MJ: Data curation, Validation, Writing–original draft, Writing–review and editing. AA: Data curation, Validation, Writing–original draft, Writing–review and editing. GT: Data curation, Validation, Writing–original draft, Writing–review and editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Abbreviations

DPPH, 2,2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl; MPLC, medium pressure liquid chromatography; HPLC, high performance liquid chromatography; HRMS, high-resolution mass spectrometry; UHPLC-DAD-ESI-MS/MS, Ultra-high-performance liquid chromatography diode array detector electrospray ionisation tandem mass spectrometry; VA, Vernonia amygdalina; IC50, Half-maximal inhibitory concentration (inhibitory concentration at 50%); LC50, 50% Lethal concentration; UV, Ultraviolet; IR, Infrared; GC-MS, Gas chromatography–mass spectrometry.

References

1

Abay S. M. Lucantoni L. Dahiya N. Dori G. Dembo E. G. Esposito F. et al (2015). Plasmodium transmission blocking activities of Vernonia amygdalina extracts and isolated compounds. Malar. J.14 (1), 288–319. 10.1186/s12936-015-0812-2

2

Abdela G. Sultan M. (2018). Indigenous knowledge, major threats and conservation practices of medicinal plants by local community in Heban Arsi District, Oromia, South Eastern Ethiopia. Adv. Life Sci. Technol.68 (10), 8–26.

3

Abebe E. (2011). Ethnobotanical study on medicinal plants used by local communities in Debark wereda, North Gondar zone, Amhara regional state, Ethiopia. PhD Thesis. Addis Ababa: Addis Ababa University, 1–139.

4

Abrha H. K. Gerima Y. G. E. W. Gebreegziabher S. T. B. (2020). Indigenous knowledge of local communities in utilization of ethnoveterinary medicinal plants and their conservation status in dess’a priority forest, north eastern escarpment of Ethiopia. 10.21203/rs.3.rs-88909/v1

5

Adebayo O. L. Abugri J. Kasim S. B. Onilimor P. J. (2014). Leaf extracts of Vernonia amygdalina Del. From northern Ghana contain bioactive agents that inhibit the growth of some beta-lactamase producing bacteria in vitro. Br. J. Pharm. Res.4 (2), 192–202. 10.9734/bjpr/2014/3200

6

Adebayo O. R. Efunwole O. O. Adegoke B. M. Raimi M. M. Adedokun A. A. (2019). Nutritional, phytochemical and fourier transform infra-red spectroscopy profiling of VA seeds. Sci. Res. J. (SCIRJ)3 (2).

7

Adewole E. Olabiran T. (2015). Antioxidant activities and nutritional compositions of Vernonia amygdalina. Acad. J. Food. Res.3 (3), 026–031. 10.15413/ajfr.2015.0101

8

Adu J. K. Twum K. Brobbey A. Amengor C. Duah Y. (2018). Resistance modulation studies of vernolide from Vernonia colorata (Drake) on ciprofloxacin, amoxicillin, tetracycline and erythromycin. J. Phytopharm.7 (5), 425–430. 10.31254/phyto.2018.7504

9

Agbankpé A. J. Bankolé S. H. Dougnon T. J. Yèhouénou B. Hounmanou Y. M. G. Baba-Moussa L. S. (2015). Comparison of nutritional values of Vernonia amygdalina, Cratevaadansoniiand Sesamum radiatum: three main vegetables used in traditional medicine for the treatment of bacterial diarrhoea in southern Benin (West Africa). Food Public Health5 (4), 144–149. 10.5923/j.fph.20150504.07

10

Agisho H. Osie M. Lambore T. (2014). Traditional medicinal plants utilization, management and threats in Hadiya Zone, Ethiopia. J. Med. Plants2 (2), 94–108.

11

Agomuo J. K. Akajiaku L. O. Alaka I. C. Taiwo M. (2016). Mineral and antinutrients of fresh and squeeze washed bitter leaf (Vernonia amygdalina) as affected by traditional de-bittering methods. Eur. J. Food Sci. Technol.4 (2), 21–30.

12

Alara O. R. Abdurahman N. H. Ukaegbu C. I. Kabbashi N. A. (2019). Extraction and characterization of bioactive compounds in Vernonia amygdalina leaf ethanolic extract comparing Soxhlet and microwave-assisted extraction techniques. J. Taibah Univ. Sci.13 (1), 414–422. 10.1080/16583655.2019.1582460

13

Ali M. Diso S. U. Waiya S. A. Abdallah M. S. (2019). Phytochemical screening and antibacterial activity of bitter leaf (Vernonia amygdalina). Ann. Microbiol. Infect. Dis.2 (4), 01–07.

14

Ali M. Muazu L. Diso S. U. Ibrahim I. S. (2020). Determination of proximate, phytochemicals and minerals composition of vernonia amygdalina (bitter leaf). Nutraceutical Res.1 (1), 1–8. 10.35702/nutri.10001

15

Amde L. A. (2017). Ethnobotanical study of traditional medicinal plants in debark district, north gondar, Ethiopia. Master’s thesis. Gondar: University of Gondar.

16

Amenu E. (2007). Use and management of medicinal plants by indigenous people of Ejaji area (Chelya woreda) West Shoa, Ethiopia: an Ethnobotanical. Master’s thesis. Addis Ababa: Addis Ababa University.

17

Amsalu B. (2020). An eNguyenno botanical study of traditional medicinal plants used in Guna Begimder woreda, South gonder zone of Amhara region, Ethiopia. Master’s thesis. Hawassa: Hawassa University.

18

Amsalu N. Bezie Y. Fentahun M. Alemayehu A. Amsalu G. (2018). Use and conservation of medicinal plants by indigenous people of GozaminWereda, East Gojjam Zone of Amhara region, Ethiopia: an ethnobotanical approach. Evidence-Based Complementary Altern. Med.2018, 1–23. 10.1155/2018/2973513

19

Andrew O. (2021). Assessing the phytochemical contents and antimicrobial activity of bitter leaf (vernonia amygdalina) on micro-organisms. Int. J. Adv. Res.9 (04), 477–483. 10.21474/ijar01/12714

20

Aremu O. I. Asiru I. D. Femi-Oyewo N. N. (2018). Formulation and antifungal screening of Vernonia amygdalina Delile (Asteraceae) leaf extract ointment. Indian J. Nov. Drug Deliv.10 (1), 11–16.

21

Asaolu M. F. Asaolu S. S. Adanlawo I. G. (2010). Evaluation of phytochemicals and antioxidants of four botanicals with antihypertensive properties. Int. J. Pharma Bio Sci.1 (2).

22

Asawalam E. F. Hassanali A. (2006). Constituents of the essential oil of Vernonia amygdalina as maize weevil protectants. Trop. Subtropical Agroecosyst.6 (2), 95–102.

23

Asfaw A. Lulekal E. Bekele T. Debella A. Abebe A. Degu S. (2021). Ethnobotanical investigation on medicinal plants traditionally used against human ailments in Ensaro district, north Shewa zone, Amhara regional state, Ethiopia. Research article (preprint). Available at: https://doi.org/10.21203/rs.3.rs-720404/v1 (Accessed September 11, 2023).

24

Asfaw A. Lulekal E. Bekele T. Debella A. Abebe A. Degu S. (2023a). Documentation of traditional medicinal plants use in Ensaro District, Ethiopia: implications for plant biodiversity and indigenous knowledge conservation. J. Herb. Med.38, 100641. 10.1016/j.hermed.2023.100641

25

Asfaw A. Lulekal E. Bekele T. Debella A. Meresa A. Sisay B. et al (2023b). Antibacterial and phytochemical analysis of traditional medicinal plants: an alternative therapeutic Approach to conventional antibiotics. Heliyon9, e22462. 10.1016/j.heliyon.2023.e22462

26

Assefa B. Megersa M. Jima T. T. (2021). Ethnobotanical study of medicinal plants used to treat human diseases in Gura Damole District, Bale Zone, Southeast Ethiopia. Asian J. Ethnobiol.4 (1). 10.13057/asianjethnobiol/y040105

27

Basha H. Debella A. Hailu A. Mequanente S. Mersa A. Ashebir R. et al (2018). In-vitro anthelmintic efficacy of the 80% hydro-alcohol extract of Myrsineafricana (kechemo) leaf on hookworm larvae. J. Public Health Dis. Prev.1, 106.

28

Bekele G. Reddy P. R. (2015). Ethnobotanical study of medicinal plants used to treat human ailments by Guji Oromo tribes in Abaya District, Borana, Oromia, Ethiopia. Univers. J. Plant Sci.3 (1), 1–8. 10.13189/ujps.2015.030101

29

Beyi M. W. (2018). Ethnobotanical investigation of traditional medicinal plants in dugda district, oromia regio. SM J. Med. Plant Stud.2 (1), 1007.

30

Bhattacharjee B. Lakshminarasimhan P. Bhattacharjee A. Agrawala D. K. Pathak M. K. (2013). Vernonia amygdalina Delile (Asteraceae)–An African medicinal plant introduced in India. Zoo’s Print28 (5), 18–20.

31

Birhan Y. S. Kitaw S. L. Alemayehu Y. A. Mengesha N. M. (2017). Ethnobotanical study of medicinal plants used to treat human diseases in EnarjEnawga District, East Gojjam zone, Amhara region, Ethiopia. SM J. Med. Plant Stud.1 (1), 1–9.

32

Biru M. A. Waday Y. A. Shumi L. D. (2022). Optimization of essential oil extraction from bitter leaf (vernonia amygdalina) by using an ultrasonic method and response surface methodology. Int. J. Chem. Eng.2022, 1–6. 10.1155/2022/4673031

33

Bogale M. Sasikumar J. M. &Egigu M. C. (2023). An ethnomedicinal study in tulo district, west hararghe zone, oromia region, Ethiopia. Heliyon9 (4), e15361. 10.1016/j.heliyon.2023.e15361

34

Cheklie G. (2020). Ethnobotanical study of medicinial plants in debube mecha woreda, west gojam zone, amhara regional state Ethiopia. Master’s thesis. Hawassa: Hawassa University.

35

Chekole G. (2017). Ethnobotanical study of medicinal plants used against human ailments in Gubalafto District, Northern Ethiopia. J. Ethnobiol. ethnomedicine13 (1), 55–29. 10.1186/s13002-017-0182-7

36

Chekole G. Asfaw Z. Kelbessa E. (2015). Ethnobotanical study of medicinal plants in the environs of Tara-gedam and Amba remnant forests of Libo Kemkem District, northwest Ethiopia. J. Ethnobiol. ethnomedicine11, 4–38. 10.1186/1746-4269-11-4

37

Cheng H. Y. Lin C. C. Lin T. C. (2002). Antiherpes simplex virus type 2 activity of casuarinin from the bark of Terminalia arjuna Linn. Antivir. Res.55 (3), 447–455. 10.1016/s0166-3542(02)00077-3

38

Dafam D. G. Agunu A. Dénou A. Kagaru D. C. Ohemu T. L. Ajima U. et al (2020). Determination of the ascorbic acid content, mineral and heavy metal levels of some common leafy vegetables of Jos, Plateau State (North Central Nigeria). Int. J. Biosci.16 (3), 389–396.

39

Dagne A. Degu S. Abebe A. Bisrat D. (2023). Antibacterial activity of a phenylpropanoid from the root extract of Carduus leptacanthusfresen. J. Trop. Med.2023, 1–6. 10.1155/2023/4983608

40

Danladi S. Hassan M. A. Masa'ud I. A. Ibrahim U. I. (2018). Vernonia amygdalina Del: a mini review. Res. J. Pharm. Technol.11 (9), 4187–4190. 10.5958/0974-360X.2018.00768.0

41

Degu S. Abebe A. Gemeda N. Bitew A. (2021a). Evaluation of antibacterial and acute oral toxicity of Impatiens tinctoria A. Rich root extracts. Plos one16 (8), e0255932. 10.1371/journal.pone.0255932

42

Degu S. Berihun A. Muluye R. Gemeda H. Debebe E. Amano A. et al (2020a). Medicinal plants that used as repellent, insecticide and larvicide in Ethiopia. Pharm. Pharmacol. Int. J.8 (5), 274–283. 10.15406/ppij.2020.08.00306

43

Degu S. Gemeda N. Abebe A. Berihun A. Debebe E. Sisay B. et al (2020b). In vitro antifungal activity, phytochemical screening and thin layer chromatography profiling of Impatiens tinctoria A. Rich root extracts. J. Med. Plants Stud.8, 189–196.

44

Degu S. Kassie E. Tsige M. Tesera Y. Desta K. (2021b). Food and beverage packaging using naturally occurring things up to modern technologies and its impact. Int. J. Agric. Nutr.3 (1), 25–32. 10.33545/26646064.2021.v3.i1a.42

45

Djeujo F. M. Stablum V. Pangrazzi E. Ragazzi E. Froldi G. (2023). Luteolin and vernodalol as bioactive compounds of leaf and root vernonia amygdalina extracts: effects on α-glucosidase, glycation, ROS, cell Viability, and in silico ADMET parameters. Pharmaceutics15 (5), 1541. 10.3390/pharmaceutics15051541

46

Echem O. G. Kabari L. G. (2013). Heavy metal content in bitter leaf (Vernonia amygdalina) grown along heavy traffic routes in Port Harcourt. Agric. Chem., 201–210. 10.5772/55604

47

Ejoh A. R. Tanya A. N. Djuikwo N. V. Mbofung C. M. (2005). Effect of processing and preservation methods on vitamin C and total carotenoid levels of some Vernonia (bitter leaf) species. Afr. J. food, Agric. Nutr. Dev.5 (2). 10.18697/ajfand.9.1525

48

Erasto P. Grierson D. S. Afolayan A. J. (2006). Bioactive sesquiterpene lactones from the leaves of Vernonia amygdalina. J. Ethnopharmacol.106 (1), 117–120. 10.1016/j.jep.2005.12.016

49

Erasto P. Grierson D. S. Afolayan A. J. (2007). Antioxidant constituents in Vernonia amygdalina leaves. Pharm. Biol.45 (3), 195–199. 10.1080/13880200701213070

50

Erdman J. W. Jr Balentine D. Arab L. Beecher G. Dwyer J. T. Folts J. et al (2007). Flavonoids and heart health: proceedings of the ILSI North America flavonoids workshop, May 31–June 1, 2005, Washington, DC. J. Nutr.137 (3), 718S–737S. 10.1093/jn/137.3.718s

51

Etta H. E. Obinze A. E. Osim S. E. (2017). Proximate composition of five accessions ofVernonia amygdalina (del) in south eastern Nigeria. NISEB J.14 (4).

52

Fekadu N. Basha H. Meresa A. Degu S. Girma B. Geleta B. (2017). Diuretic activity of the aqueous crude extract and hot tea infusion of Moringa stenopetala (Baker f.) Cufod. leaves in rats. J. Exp. Pharmacol.9, 73–80. 10.2147/JEP.S133778

53

Frederick Eleyinmi A. Sporns P. Bressler D. C. (2008). Nutritional composition of Gongronema latifolium and Vernonia amygdalina. Nutr. Food Sci.38 (2), 99–109. 10.1108/00346650810862975

54

Garba Z. N. Oviosa S. (2019). The effect of different drying methods on the elemental and nutritional composition of Vernonia amygdalina (bitter leaf). J. Taibah Univ. Sci.13 (1), 396–401. 10.1080/16583655.2019.1582148

55

Gebeyehu F. (2020). An Ethnobotanical study of medicinial plants used to treat human and livestock ailments in entoto forest and its environment, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. Master’s thesis. Hawassa: Hawassa University.

56

Getaneh S. Girma Z. (2014). An ethnobotanical study of medicinal plants in Debre LibanosWereda, Central Ethiopia. Afr. J. Plant Sci.8 (7), 366–379. 10.5897/AJPS2013.1041

57

Girma Z. Abdela G. Awas T. (2022). Ethnobotanical study of medicinal plant species in Nensebo District, south-eastern Ethiopia. Ethnobot. Res. Appl.24, 1–25. 10.32859/era.24.28.1-25

58

Girmay T. Teshome Z. (2017). Assessment of traditional medicinal plants used to treat human and livestock ailments and their threatening factors in Gulomekeda District, Northern Ethiopia. Int. J. Emerg. Trends Sci. Technol.4 (4), 5061–5070. 10.18535/ijetst/v4i4.03

59

Gonfa Y. H. Tessema F. B. Gelagle A. A. Getnet S. D. Tadesse M. G. Bachheti A. et al (2022). Chemical compositions of essential oil from aerial parts of Cyclospermumleptophyllum and its application as antibacterial activity against some food spoilage bacteria. J. Chem.2022, 1–9. 10.1155/2022/5426050

60

Habtamu A. Melaku Y. (2018). Antibacterial and antioxidant compounds from the flower extracts of Vernonia amygdalina. Adv. Pharmacol. Pharm. Sci.2018, 1–6. 10.1155/2018/4083736

61

Haile A. A. (2022). Ethnobotanical study of medicinal plants used by local people of MojanaWadera woreda, north shewa zone, amhara region, Ethiopia. Asian J. Ethnobiol.5 (1). 10.13057/asianjethnobiol/y050104

62

Hassen A. Muche M. Muasya M. Abraha B. T. (2021). Exploration of traditional plant based medicines used as potential remedies for livestock aliments in northeastern Ethiopia. 10.21203/rs.3.rs-250728/v1

63

IfedibaluChukwu E. I. Aparoop D. Kamaruz Z. (2020). Antidiabetic, anthelmintic and antioxidation properties of novel and new phytocompounds isolated from the methanolic stem-bark of Vernonia amygdalina Delile (Asteraceae). Sci. Afr.10, e00578. 10.1016/j.sciaf.2020.e00578

64

Ifesan B. O. T. Egbewole O. O. &Ifesan B. T. (2014). Effect of fermentation on nutritional composition of selected commonly consumed green leafy vegetables in Nigeria. Int. J. Appl. Sci. Biotechnol.2 (3), 291–297. 10.3126/ijasbt.v2i3.11003

65

Ijeh I. I. Ejike C. E. C. C. (2011). Current perspectives on the medicinal potentials of Vernonia amygdalina Del. J. Med. plants Res.5 (7), 1051–1061.

66

Imohiosen O. Samaila D. andElisha A. (2021). Comparative study for phytochemical analysis of dry bitter leaf (vernonia amygdalina delile) and sweet bitterleaf (Vernonia hymenolepis) leave for their nutritional and medicinal benefits. Int. J. Interdiscip. Res. Innovations9 (2), 9–17.

67

Inusa A. Sanusi S. B. Linatoc A. C. Mainassara M. M. Awawu J. J. (2018). Phytochemical analysis and antimicrobial activity of bitter leaf (Vernonia amygdalina) collected from Lapai, Niger State, Nigeria on some selected pathogenic microorganisms. Sci. World J.13 (3), 15–18.

68

Jima T. T. Megersa M. (2018). Ethnobotanical study of medicinal plants used to treat human diseases in berbere district, bale zone of oromia regional state, south east Ethiopia. Evidence-Based Complementary Altern. Med.2018, 1–16. 10.1155/2018/8602945

69

Johnson M. Kolawole O. S. Olufunmilayo L. A. (2015). Phytochemical analysis, in vitro evaluation of antioxidant and antimicrobial activity of methanolic leaf extract of Vernonia amygdalina(bitter leaf) against Staphylococcus aureus and Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Int. J. Curr. Microbiol. App. Sci.4 (5), 411–426.

70

Kassa Z. Asfaw Z. Demissew S. (2016). Ethnobotanical study of medicinal plants used by the local people in Tulu Korma and its surrounding areas of Ejere district, Western Shewa zone of Oromia regional state, Ethiopia. J. Med. Plants Stud.4 (2), 24–47.

71

Kaur D. Kaur N. Chopra A. (2019). A comprehensive review on phytochemistry and pharmacological activities of Vernonia amygdalina. J. Pharmacogn. Phytochemistry8 (3), 2629–2636.

72

Kebebew M. Mohamed E. (2017). Indigenous knowledge on use of medicinal plants by indigenous people of Lemo district, Hadiya zone, Southern Ethiopia. Int. J. Herb. Med.5 (4), 124–135.

73

Kindie B. (2023). Study on medicinal plant use and conservation practices in selected woreda around harar town, eastern Ethiopia. Age20 (35), 21.

74

Kindie B. Tamiru C. Abdala T. (2021). Ethnobotanical study of medicinal plants and conservation status used to treat human and livestock ailments in Fadis District, Eastern Ethiopia. Int. J. Homeopath Nat. Med.7 (1), 7–17. 10.11648/j.ijhnm.20210701.12

75

Legesse M. Abebe A. Degu S. Alebachew Y. Tadesse S. (2022). Synthesis and antimicrobial activity of knipholone analogs. Nat. Prod. Res., 1–7. 10.1080/14786419.2022.2139696

76

Lulekal E. Asfaw Z. Kelbessa E. Van Damme P. (2014). Ethnoveterinary plants of Ankober district, north Shewa zone, Amhara region, Ethiopia. J. Ethnobiol. ethnomedicine10 (1), 21–19. 10.1186/1746-4269-10-21

77

Luo X. Jiang Y. Fronczek F. R. Lin C. Izevbigie E. B. Lee K. S. (2011). Isolation and structure determination of a sesquiterpene lactone (vernodalinol) from Vernonia amygdalina extracts. Pharm. Biol.49 (5), 464–470. 10.3109/13880209.2010.523429

78

Lyumugabe Loshima F. Uyisenga J. P. Bayingana C. Songa E. B. (2017). Antimicrobial activity and phytochemicals analysis of Vernonia aemulans, Vernonia amygdalina, Lantana camara andMarkhamia lutea leaves as natural beer preservatives. Am. J. Food. 10.3923/ajft.2017.35.42

79

Mekonnen A. B. Mohammed A. S. Tefera A. K. (2022). Ethnobotanical study of traditional medicinal plants used to treat human and animal diseases in sedie muja district, south gondar, Ethiopia. Evidence-based Complementary Altern. Med.2022, 1–22. 10.1155/2022/7328613

80

Melkamu G. (2021). Ethnobotanical study on assessment of indigenous knowledge on traditional plant medicine use among people of wonchi district in southwest shewa zone, oromia national regional state, Ethiopia. Health Sci. J.15 (9), 1–9.

81

Meresa A. Degu S. Tadele A. Geleta B. Moges H. Teka F. et al (2017). Medicinal plants used for the management of rabies in Ethiopia–a review. Med. Chem. (Los Angeles)7, 795–806. 10.4172/2161-0444.1000431

82

Molla A. M. (2019). Ethnobotanical study of traditional medicinal plants used to treat human and livestock ailments in dera woreda, south gondar, Ethiopia. Master’s thesis. Hawasssa: Hawasssa University.

83

Momoh M. A. Muhamed U. Agboke A. A. Akpabio E. I. Osonwa U. E. (2012). Immunological effect of aqueous extract of Vernonia amygdalina and a known immune booster called immunace® and their admixtures on HIV/AIDS clients: a comparative study. Asian Pac. J. Trop. Biomed.2 (3), 181–184. 10.1016/S2221-1691(12)60038-0

84

Muluye R. A. Berihun A. M. Gelagle A. A. Lemmi W. G. Assamo F. T. Gemeda H. B. et al (2021). Evaluation of in vivo antiplasmodial and toxicological effect of Calpurnia aurea, Aloe debrana, Vernonia amygdalina and Croton macrostachyus extracts in mice. Med. Chem.11, 534.

85

Narayanan B. A. Geoffroy O. Willingham M. C. Re G. G. Nixon D. W. (1999). p53/p21 (WAF1/CIP1) expression and its possible role in G1 arrest and apoptosis in ellagic acid treated cancer cells. Cancer Lett.136 (2), 215–221. 10.1016/s0304-3835(98)00323-1

86

Nguyen T. X. T. Dang D. L. Ngo V. Q. Trinh T. C. Trinh Q. N. Do T. D. et al (2021). Anti-inflammatory activity of a new compound from Vernonia amygdalina. Nat. Prod. Res.35 (23), 5160–5165. 10.1080/14786419.2020.1788556

87

Nkechi O. (2023). Effects of de-bittering treatments on the nutrient composition, carotenoid content and profile of bitter leaf (Vernonia amygdalina). Repository.mouau.edu.ng (project): Available at: https://repository.mouau.edu.ng/work/view/effects-of-de-bittering-treatments-on-the-nutrient-composition-carotenoid-content-and-profile-of-bitter-leaf-vernonia-amygdalina-7-2 (Accessed November 25, 2023).

88

Nowak J. Kiss A. K. Wambebe C. Katuura E. Kuźma Ł. (2022). Phytochemical analysis of polyphenols in leaf extract from Vernonia amygdalina Delile plant growing in Uganda. Appl. Sci.12 (2), 912. 10.3390/app12020912

89

Nursuhaili A. B. Nur Afiqah Syahirah P. Martini M. Y. Azizah M. Mahmud T. M. M. (2019). A review: medicinal values, agronomic practices and postharvest handlings of Vernonia amygdalina. Food Res.3 (5), 380–390. 10.26656/fr.2017.3(5).306

90

Nwaoguikpe R. N. (2010). The effect of extract of bitter leaf (Vernonia amygdalina) on blood glucose levels of diabetic rats. Int. J. Biol. Chem. Sci.4 (3). 10.4314/ijbcs.v4i3.60500

91

Nwogwugwu C. P. Petrus N. E. Ethelbert O. C. Lynda O. C. (2015). Effect of Vernonia amygdalina (bitter leaf) extract on growth performance, carcass quality and economics of production of broiler chickens. Int. J. Agric. Earth Sci.1 (5), 1–13.

92

Oboh G. (2006). Nutritive value and haemolytic properties (in vitro) of the leaves of Vernonia amygdalina on human erythrocyte. Nutr. health18 (2), 151–160. 10.1177/026010600601800207

93

Oboh F. O. Masodje H. I. (2009). Nutritional and antimicrobial properties of Vernonia amygdalina leaves. Int. J. Biomed and Health.5 (2).

94

Offor C. E. (2014). Comparative chemical analyses of Vernonia amygdalina and Azadirachta indica leaves. IOSR J. Pharm. Biol. Sci.9 (5), 73–77. 10.9790/3008-09527377

95

Ofori D. A. Anjarwalla P. Jamnadass R. Stevenson P. C. Smith P. (2013). Pesticidal plant leaflet Vernonia amygdalina Del. Australia: Royal botanic garden, 1–2.

96

Ogunnowo A. A. Alao-Sanni O. Ayodele Og A. (2010). Comparative antioxidant, phytochemical and proximate analysis of aqueous and methanolic extracts of Vernonia amygdalina and Talinum triangulare. Pak. J. Nutr.9 (3), 259–264. 10.3923/pjn.2010.259.264

97

Ojimelukwe P. C. Amaechi N. (2019). Composition of Vernonia amygdalina and its potential health benefits. Int. J. Environ. Agric. Biotechnol.4 (6), 1836–1848. 10.22161/ijeab.46.34

98

Okeke C. U. Ezeabara C. A. Okoronkwo O. F. Udechukwu C. D. Uka C. J. Bibian O. A. (2015). Determination of nutritional and phytochemical compositions of two variants of bitter leaf (Vernonia amygdalina Del). J. Hum. Nutr. Food Sci.3 (3), 1065.

99

Okolie H. Ndukwe O. Obidiebube E. Obasi C. Enwerem J. (2021). Evaluation of nutritional and phytochemical compositions of two bitter leaf (vernonia amygdalina) accessions in Nigeria. Int. J. Res. Innovation Appl. Sci.6 (12), 2454–6194.

100

Oladunmoye M. K. Afolami O. I. Oladejo B. O. Amoo I. A. Osho B. I. (2019). Identification and quantification of bioactive compounds present in the plant vernonia amygdalina delile using GC-MS Technique. Nat. Prod. Chem. Res.7 (356), 2. 10.4172/2329-6836.1000356

101

Olowoyeye O. J. Sunday A. Abideen A. A. Owolabi O. A. Oluwadare O. E. Ogundele J. A. (2022). Effects of vegetative zones on the nutritional composition of vernonia amygdalina leaves in ekiti state. Int. J. Med. Pharm. Drug Res.6 (2), 29–34. 10.22161/ijmpd.6.2.4

102

Olumide M. D. Ajayi O. A. Akinboye O. E. (2019). Comparative study of proximate, mineral and phytochemical analysis of the leaves of Ocimumgratissimum, Vernonia amygdalina and Moringa oleifera. J. Med. Plants Res.13 (15), 351–356. 10.5897/JMPR2019.6775

103

Olusola S. E. Olaifa F. E. (2018). Evaluation of some edible leaves as potential feed ingredients in aquatic animal nutrition and health. J. Fish.6 (1), 569–578. 10.17017/jfish.v6i1.2018.266

104

Olusola-Makinde O. Olabanji O. B. Ibisanmi T. A. (2021). Evaluation of the bioactive compounds of Vernonia amygdalinaDelile extracts and their antibacterial potentials on water-related bacteria. Bull. Natl. Res. Cent.45, 191. 10.1186/s42269-021-00651-6

105

Oluyege J. O. Orjiakor P. I. Olowe B. M. Miriam U. O. Oluwasegun O. D. (2019). Antimicrobial potentials of Vernonia amygdalina and honey on vancomycin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus from clinical and environmental sources. Open Access Libr. J.6 (05), 1–13. 10.4236/oalib.1105437

106

Omoyeni O. A. Olaofe O. Akinyeye R. O. (2015). Amino acid composition of ten commonly eaten indigenous leafy vegetables of South-West Nigeria. World J. Nutr. Health3 (1), 16–21. 10.12691/jnh-3-1-3

107

Owoeye O. Yousuf S. Akhtar M. N. Qamar K. Dar A. Farombi E. O. et al (2010). Another anticancer elemanolide from Vernonia amygdalina Del. Int. J. Biol. Chem. Sci.4 (1). 10.4314/ijbcs.v4i1.54250

108

Paul T. A. Taibat I. Kenneth E. I. Haruna N. I. Baba O. V. Helma A. R. (2018). Phytochemical and antibacterial analysis of aqueous and alcoholic extracts of Vernonia amygdalina (del.) leaf. World J. Pharm.7 (7), 9–17.

109

Quasie O. Zhang Y. M. Zhang H. J. Luo J. Kong L. Y. (2016). Four new steroid saponins with highly oxidized side chains from the leaves of Vernonia amygdalina. Phytochem. Lett.15, 16–20. 10.1016/j.phytol.2015.11.002

110

Rabi T. Bishayee A. (2009). Terpenoids and breast cancer chemoprevention. Breast cancer Res. Treat.115, 223–239. 10.1007/s10549-008-0118-y

111

Senthilkumar A. Karuvantevida N. Rastrelli L. Kurup S. S. Cheruth A. J. (2018). Traditional uses, pharmacological efficacy, and phytochemistry of Moringa peregrina (Forssk) Fiori—a review. Front. Pharmacol.9, 465. 10.3389/fphar.2018.00465

112

Shewo B. S. Girma B. (2017). Review on nutritional and medicinal values of Vernonia amygdalina and its uses in human and veterinary medicines. Glob. Veterinaria19 (3), 562–568. 10.5829/idosi.gv.2017.562.568

113

Shokunbi O. S. Anionwu O. A. Sonuga O. S. Tayo G. O. (2011). Effect of post-harvest processing on the nutrient and anti-nutrient compositions of Vernonia amygdalina leaf. Afr. J. Biotechnol.10 (53), 10980–10985. 10.5897/ajb11.1532

114

Sisay B. Debebe E. Meresa A. Gemechu W. Kasahun T. Teka F. et al (2020). Phytochemistry and method preparation of some medicinal plants used to treat asthma-review. J. Anal. Pharm. Res.9 (3), 107–115. 10.15406/japlr.2020.09.00359

115

Ssempijja F. Iceland Kasozi K. Daniel Eze E. Tamale A. Ewuzie S. A. Matama K. et al (2020). Consumption of raw herbal medicines is associated with major public health risks amongst Ugandans. J. Environ. Public Health2020, 1–10. 10.1155/2020/8516105

116

Tahir M. Gebremichael L. Beyene T. Van Damme P. (2021). Ethnobotanical study of medicinal plants in Adwa district, central zone of Tigray regional state, northern Ethiopia. J. Ethnobiol. ethnomedicine17 (1), 71–13. 10.1186/s13002-021-00498-1

117

Tassew G. (2019). Ethnobotanical study of medicinal plants in borecha woreda, buno bedele zone southwestern Ethiopia. Int. J. Sci. Res.8 (9), 1484–1498. 10.21275/ART20201305

118

Teka A. Asfaw Z. Demissew S. Van Damme P. (2020). Medicinal plant use practice in four ethnic communities (Gurage, Mareqo, Qebena, and Silti), south central Ethiopia. J. Ethnobiol. ethnomedicine16, 27–12. 10.1186/s13002-020-00377-1

119

Teklehaymanot T. Giday M. Medhin G. Mekonnen Y. (2007). Knowledge and use of medicinal plants by people around Debre Libanos monastery in Ethiopia. J. Ethnopharmacol.111 (2), 271–283. 10.1016/j.jep.2006.11.019

120

Tesera Y. Desalegn A. Tadele A. Mengesha A. Hurisa B. Mohammed J. et al (2022). Phytochemical screening, acute toxicity and anti-rabies activities of extracts of selected Ethiopian traditional medicinal plants. J. Pharm. Res.7 (1), 150–158.

121

Tian B. Liu J. Liu Y. Wan J. B. (2023). Integrating diverse plant bioactive ingredients with cyclodextrins to fabricate functional films for food application: a critical review. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr.63 (25), 7311–7340. 10.1080/10408398.2022.2045560

122

TjhiaA B. AzizB S. A. SuketiB K. (2018). Correlations between leaf nitrogen, phosphorus and potassium and leaf chlorophyll, anthocyanins and carotenoids content at vegetative and generative stage of bitter leaf (vernonia amygealina del). J. Trop. Crop Sci.5 (1), 25–33. 10.29244/jtcs.5.1.25-33

123

Tonukari N. J. Avwioroko O. J. Ezedom T. Anigboro A. A. (2015). Effect of preservation on two different varieties of Vernonia amygdalina Del (bitter) leaves. Food Nutr. Sci.6 (07), 633–642. 10.4236/fns.2015.67067

124

Tsado A. N. Lawal B. Santali E. S. Shaba A. M. Chirama D. N. Balarabe M. M. et al (2015). Effect of different processing methods on nutritional composition of Bitter Leaf (Vernonia amygdalina). IOSR J. Pharm.5.

125

Tsegay B. Mazengia E. Beyene T. (2019). Short Communication: diversity of medicinal plants used to treat human ailments in rural Bahir Dar, Ethiopia. Asian J. For.3 (2). 10.13057/asianjfor/r00300205

126

Tuasha N. Petros B. Asfaw Z. (2018). Medicinal plants used by traditional healers to treat malignancies and other human ailments in Dalle District, Sidama Zone, Ethiopia. J. Ethnobiol. ethnomedicine14 (1), 15–21. 10.1186/s13002-018-0213-z

127

Tugume P. Nyakoojo C. (2019). Ethno-pharmacological survey of herbal remedies used in the treatment of paediatric diseases in Buhunga parish, Rukungiri District, Uganda. BMC Complementary Altern. Med.19 (1), 353–410. 10.1186/s12906-019-2763-6

128