Abstract

The increasing prevalence of viral infections and the emergence of drug-resistant or mutant strains necessitate the exploration of novel antiviral strategies. Accumulating evidence suggests that natural plant products have significant potential to enhance the human antiviral response. Various plant natural products (PNPs) known for their antiviral properties have been evaluated for their ability to modulate immune responses and inhibit viral infections. Research has focused on understanding the mechanisms by which these PNPs interact with the human immune system and their potential to complement existing antiviral therapies. PNPs control compounds such as alkaloids, flavonoids, terpenoids, and polyphenols to promote antiviral cytokine synthesis, increase T-cell and macrophage activity, and activate antiviral genes. Studies have investigated the molecular interactions between PNPs, viruses, and host cells, exploring the potential of combining PNPs with conventional antiviral drugs to enhance efficacy. However, several challenges remain, including identifying, characterizing, and standardizing PNP extracts, optimizing dosages, improving bioavailability, assessing long-term safety, and navigating regulatory approval. The promising potential of PNPs is being explored to develop new, effective, and natural antiviral therapies. This review outlines a framework for an integrative approach to connect the full potential of PNPs in combating viral infections and improving human health. By combining natural plant products with conventional antiviral treatments, more effective and sustainable management of viral diseases can be achieved.

Introduction

Infectious diseases have shaped human civilization, with urbanization and trade increasing zoonotic pathogen spread. Major pandemics like SARS-CoV, MERS-CoV, and COVID-19 have highlighted the global health burden and socioeconomic conditions of viral infections, with COVID-19 alone causing over 180 million cases and 4 million deaths (World Health Organization, 2021), Despite advancements in immunization and drug development, many viruses still lack preventive vaccines and effective antiviral treatments, often undermined by viral escape mutants (Lin L.-T. et al., 2014). Therefore, discovering new antiviral drugs is crucial, and natural products offer a valuable resource for these discoveries. Natural products from plants, animals, or microbes offer pharmacological benefits beyond nutrition and have long been used as medicines, hallucinogens, food additives, and fragrances.

Plants are the primary source of natural products that serve as a key source of human medicines and play a pivotal role in drug discovery and design. Various traditional medicinal practices, such as Ayurveda, traditional Chinese medicine, Kampo, traditional Korean medicine, and Unani medicine, have enlisted several kinds of plant species used for treating human diseases. Identifying active compounds in these medicines remains a source of modern drug discovery. Interestingly, the FDA approved 1,562 drugs till 2019, of which 586 (37%) are natural products or their derivatives (Newman and Cragg, 2020). Of these approved drugs, only 53 are antiviral drugs, classified into biological molecules, natural product derivatives, and mimics of natural compounds (Newman and Cragg, 2020). However, antiviral drug discovery acts slowly compared to antibiotics, probably due to the “one drug one virus” dogma. Viruses are obligatory parasites, and most naturally derived antiviral compounds inhibit viral replication and target virus-host interactions. Some natural compounds can inhibit the growth of multiple viruses that utilize a similar pathway or host factor, acting as a source for the “one drug multiple virus” consortium. Thus, the pharmaceutical industry’s focus on natural products can accelerate antiviral drug discovery. In addition to aiding in drug discovery, plant natural products (PNPs), can improve human immunity. Consuming PNPs as probiotics and functional foods helps combat infections due to their bioactive compounds. These foods, rich in flavonoids, phenolics, carotenoids, vitamins, and minerals, can eliminate or inactivate viruses, boost immunity, and improve overall health. Regular intake may prevent viral replication, reduce symptom severity, low mortality rate, and speed recovery. Furthermore, PNPs function as probiotics to prevent viral infections by adhering to them and hindering host-cell communication (Singh S. et al., 2021; Saddiqa et al., 2024).

PNPs are involved in innate immunity response modulation, B-lymphocyte proliferation, and the generation of cytotoxic chemicals such as nitric oxide free radicals, T-lymphocytes, and phagocytosis activation (Vieira et al., 2024). Various ex-vivo and in vivo measures have proven that consuming PNPs enhances immunity against viruses (Elshafie et al., 2023). In this review, we discussed the role of bioactive natural products in antiviral drug discovery and highlighted their action against viral invasion based on insights from previously published studies.

Plant natural products (PNPs): an insight

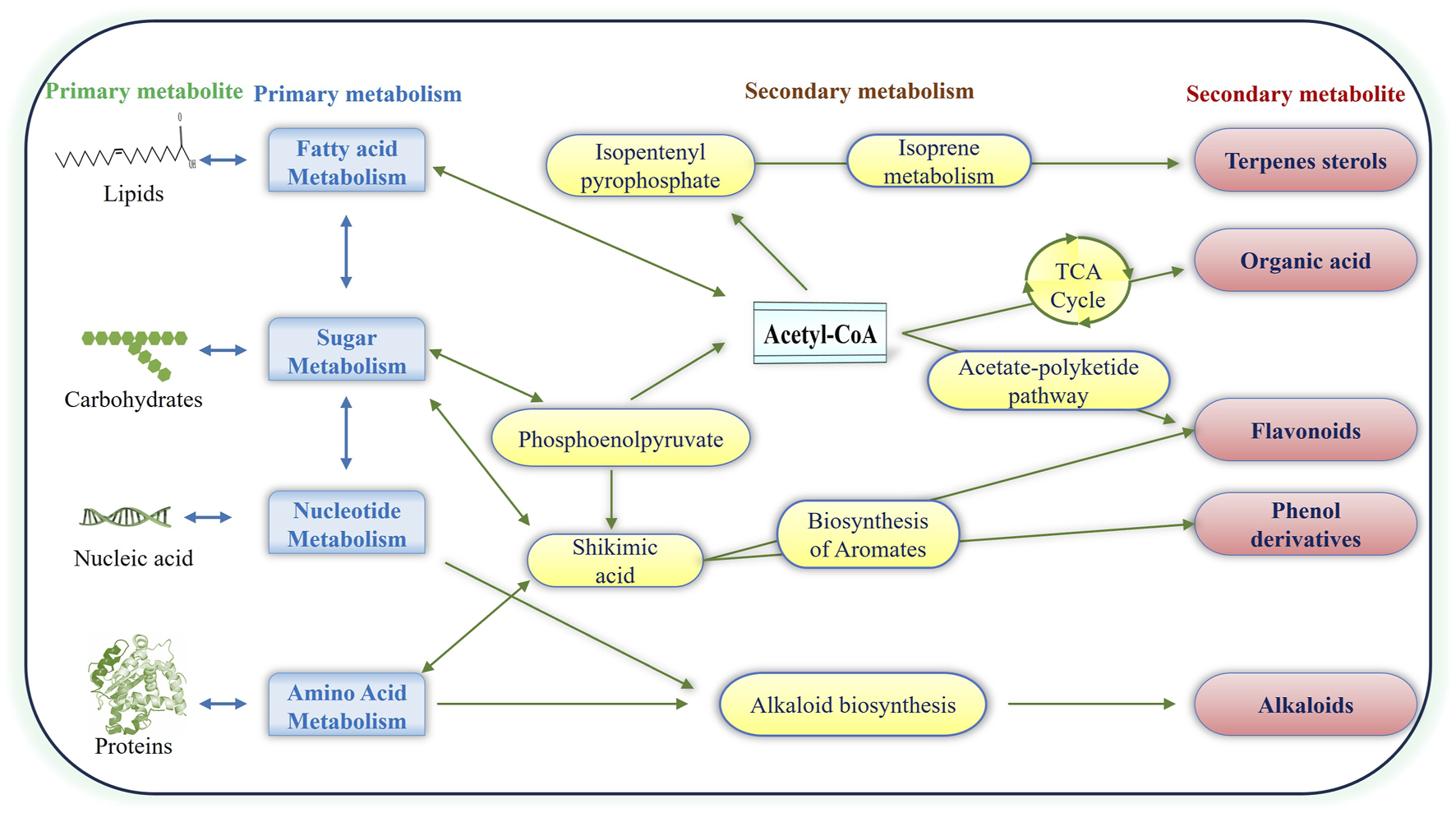

PNPs have high structural diversity and unique pharmacological or biological activities due to the natural selection and evolutionary processes that have shaped their utility over hundreds of thousands of years. PNPs include a wide range of compounds, for example, Alkaloids (Nicotine, morphine, quinine), Phenolics (Flavonoids, tannins, lignans), Terpenoids (Essential oils, carotenoids, saponins), Glycosides (Cardiac glycosides, cyanogenic glycosides), Polysaccharides (Beta-glucans, pectins) (Kaur et al., 2021; Prakash et al., 2021; Thomas et al., 2021; Kumar A. et al., 2022; Al-Khayri et al., 2023; Bhatla and Lal, 2023). PNP compounds are often divided into two major classes: primary and secondary metabolites (Figure 1). Primary metabolites are vital for survival, forming key macromolecules like nucleic acids, amino acids, and sugars. Secondary metabolites, though not essential for survival, aid in the organism’s competitiveness within its environment. (Bhardwaj et al., 2021; Elshafie et al., 2023). Plants produce a wide array of secondary metabolites with complex chemical compositions. These compounds are synthesized in response to various stresses and serve crucial physiological functions (Srivastava et al., 2014; Pandey et al., 2016; Srivastava et al., 2018; Pandey et al., 2019; Mishra et al., 2020; Bajpai et al., 2023; Elshafie et al., 2023). Plant secondary metabolites are classified into four major classes depending on their biosynthetic pathway: (i) phenolic groups; (ii) terpenes and steroids (iii) nitrogen-containing compounds; and (iv) sulfur-containing compounds (Prakash et al., 2021; Kumar A. et al., 2022; Al-Khayri et al., 2023; Bhatla and Lal, 2023). Due to their bioactive qualities, which can have toxicological or pharmacological impacts on humans as well as animals, many of these secondary metabolites are relevant to the drug manufacturing sector. Plant secondary metabolites have various health benefits, including immune system support, antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, neutralizing free radicals, allergy relief, cardiovascular health, neurodegenerative diseases, pain-relieving effects, and anti-carcinogenic properties (Elshafie et al., 2023).

FIGURE 1

Illustration of Plant Natural Products: primary and secondary metabolites. Pathways from primary metabolites contribute to the production of terpenes, flavonoids, phenolics, alkaloids and organic acids, forming distinctive major classes of secondary metabolites.

Viral infections and human immunity

Human viral infections can seriously negatively influence society and the economy. Human viral diseases are a major global health concern due to their high morbidity and mortality rates, frequency, and potential for outbreaks (Luo and Gao, 2020; Baker et al., 2022). Viruses are tiny entities with either RNA or DNA as their genetic material, and they cannot exist without a host. Structurally, a typical virus has a lipid membrane called the viral envelope, covering a protein coat called a capsid that surrounds the genetic material (MW, 2014; Luo and Gao, 2020). Viruses reproduce by inserting their genome into the host cell, making multiple copies, and assembling new viral components within the infected cell (Roossinck, 2011; Hull, 2014). The etiologies vary due to distinct viruses, such as RNA viruses (e.g., influenza, coronaviruses) and DNA viruses (e.g., poxviruses, herpesviruses). The dsDNA (double standard DNA) viruses that infect humans have genome sizes ranging from 5 to 1,180 kb, linked to the stability of dsDNA and a low replication error rate (Payne, 2017). At the same time, ssDNA (single standard DNA) viruses have smaller genomes (2–7 Kb) and are generally non-enveloped with icosahedral capsids. Retroviruses, which include families like Retroviridae (e.g., HIV) and Hepadnaviridae (e.g., Hep B), challenge the Central Dogma of human biology (Gelderblom, 1996; Tramontano et al., 2019). Human viral infections can present with a wide variety of symptoms, from mild flu-like signs to severe respiratory distress, neurological disorders, and potentially premature death. These viral infections may be progressive, cancer-causing, latent, revived, acute, or chronic. The specific health problems vary based on the infection’s progression, cellular affinity, and host cell resistance. Because of their high rates of morbidity and mortality, high frequency, and potential for outbreaks and pandemics, human viral diseases have become a major global health concern (Morales-Sánchez and Fuentes-Pananá, 2014; Prasad et al., 2017). The illnesses’ etiologies differ because of distinct viruses, such as RNA viruses (e.g., G. influenza, and coronaviruses) and DNA viruses (e.g., G. Poxviruses, Herpesviruses, etc.) (Payne, 2017; Rampersad and Tennant, 2018).

The defense against pathogens is broadly classified into innate and adaptive immunity. Innate immunity is non-specific and serves as the first line of defense such as inflammatory responses and the complement system (Smith et al., 2019; Pal and Chakravarty, 2020). Adaptive immunity is specific and acquired over time, involving antibodies, lymphocytes, antigen presentation and immunological memory. Human viral infections can range from mild symptoms, like the flu, to severe respiratory issues, neurological disorders, or even death. The health impact of viral infections depends on factors like infection progression, cellular affinity, and host resistance, with infections potentially being acute, chronic, latent, or cancer-causing. (Silva et al., 2022; Brown et al., 2023).

Multiple consequences of viruses on human immunity frequently result in a compromised immune system and increased vulnerability to new infections. For example, HIV targets and destroys CD4+ T cells, causing immunosuppression, while the measles virus induces “immune amnesia” by depleting memory T and B cells (Mueller and Rouse, 2008; McNab et al., 2015; Sette and Crotty, 2021). Through antigenic variation and latency, viruses have developed evasive ways to avoid the immune system being recognized. For instance, Viruses like HIV and influenza evade immunity through antigenic variation, continually mutating their surface proteins. Herpesviruses, such as HSV and EBV, enter latency within host cells, reactivating periodically to avoid detection by the immune system (Yewdell and Hill, 2002; Paludan et al., 2011; White et al., 2012; Silva et al., 2024).

Certain viruses generate proteins that directly disrupt the host’s immune system, resulting in the suppression of immunological responses. Hepatitis C and other viruses produce proteins that inhibit interferon synthesis. In chronic infections like Hepatitis B and C, viruses also disrupt immune checkpoints to suppress effective T-cell responses. (Gokhale et al., 2014; Karamichali et al., 2022; Zheng et al., 2023). Prolonged viral infections result in chronic or persistent immunological activation, which could have negative consequences. Persistent infections, like Hepatitis B and C, leading to liver damage and cirrhosis (Marcellin and Boyer, 2003; Baseke et al., 2015; Ferrari, 2015). Persistent immune activation in HIV is linked deterioration of immune function (Gobran et al., 2021). Some viral infections may induce the immunopathology condition where the immune system causes tissue destruction. For example, Severe COVID-19 can trigger a “cytokine storm,” causing widespread inflammation and tissue damage (Gour et al., 2021; Que et al., 2022; Panteleev et al., 2023).

Viral infections can impact various components of both the innate and adaptive immune systems. For instance, Viruses like HIV and dengue impair dendritic cell function, disrupting antigen presentation and adaptive immunity (St. John and Rathore, 2019; Constant et al., 2022; Lee et al., 2022). Some also reduce natural killer (NK) cell activity by downregulating activating ligands. HIV and Hepatitis C cause T cell exhaustion, lowering functionality, while Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) infects B cells, increasing lymphoma risk (Rouse and Sehrawat, 2010; Carty et al., 2021; Singh H. et al., 2021).

Mechanisms of plant-natural products on human immunity

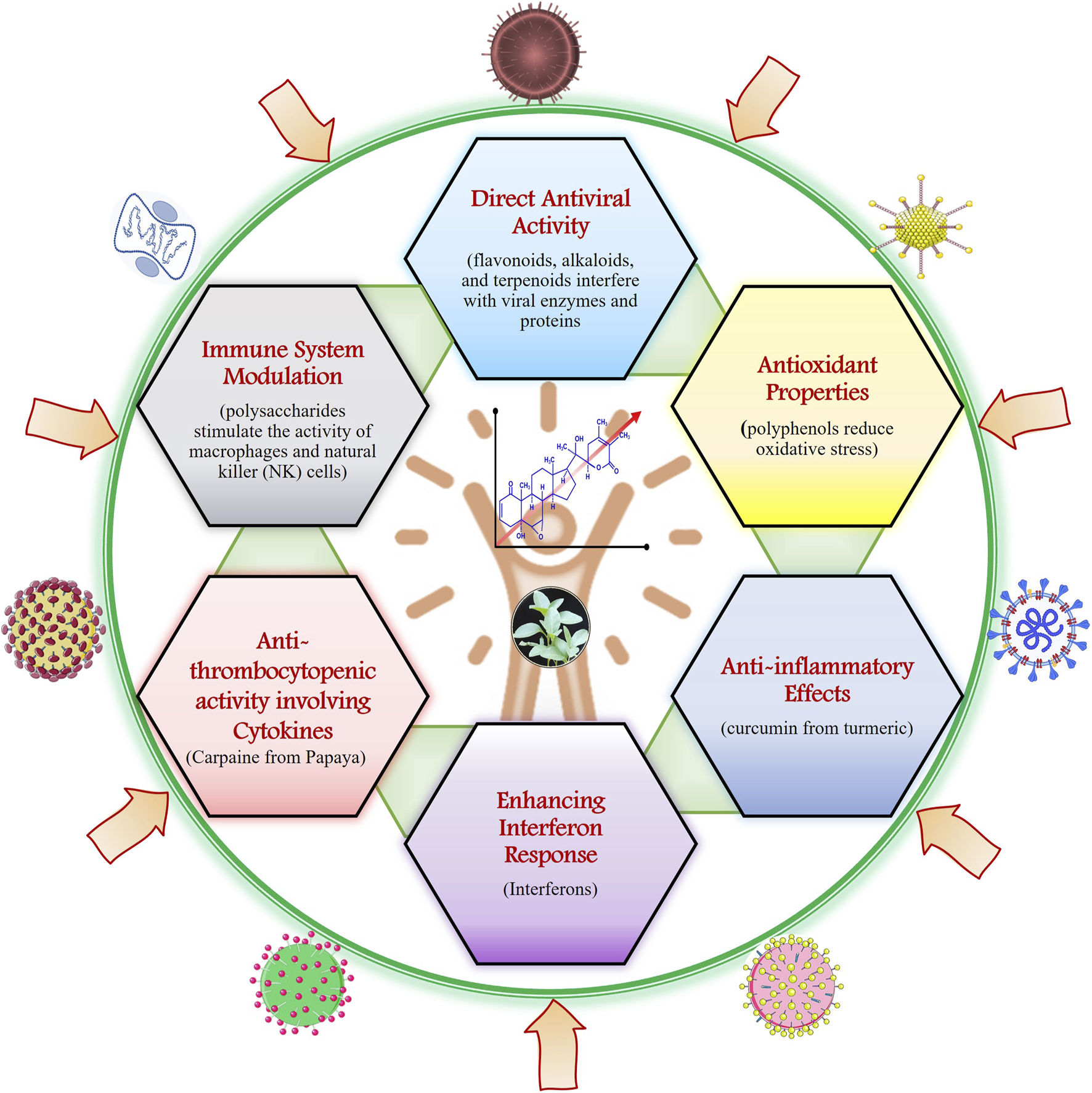

Plant-based natural products have been used in traditional medicine for centuries to address various health issues, including viral infections. Plant natural products (PNPs) have a significant impact on human immunity through their various bioactive compounds (Hu et al., 2024). Recently, scientific research has delved into understanding how these natural compounds boost the human antiviral response. Those mechanisms can be broadly categorized in direct antiviral activity, immune system modulation, antioxidant properties, anti-inflammatory effects, enhancement of interferon response, and anti-thrombocytopenic properties, as depicted in Figure 2 and Table 1. Firstly, direct antiviral activity involves plant compounds that inhibit viral replication. For instance, flavonoids, alkaloids, and terpenoids have been shown to interfere with viral enzymes and proteins crucial for the virus’s lifecycle (Table 1). Secondly, immune system modulation is achieved by plant-derived compounds that enhance the immune system’s ability to fight off infections. Some PNPs can modulate immune responses by enhancing or suppressing specific immune system components. PNPs can enhance the adaptive immune response by promoting the production and activity of T-cells and B-cells. Green tea catechins improve the proliferation and differentiation of T-cells. For example, Plant Ginseng whose active component is Ginsenosides enhances both innate and adaptive immunity and increases the activity of macrophages, NK cells, and T-cells (Ferrucci et al., 2024; Nikiema et al., 2024).

FIGURE 2

The image illustrates various mechanisms by which natural products contribute to antiviral activity and enhance immune function in the human.

TABLE 1

| Compound | Plant source | Metabolite class | Plant organ | Virus against working | Antiviral activity | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alkaloid extract | Haemanthus albiflos | Alkaloids | Bulbs | HRV | Inhibited RNA synthesis | Husson et al. (1994) |

| Anisotine | Justicia adhatoda L. | Alkaloids | Leaf | SARS-CoV-2, HSV | Inhibit Mpro of SARS-CoV-2 which mediates the cleavage of polyprotein to matured and acquire infectivity | Chavan and Chowdhary (2014), Ghosh et al. (2021) |

| Berberine | Berberis vulgaris | Alkaloids | Plant roots, Rhizomes, and Stem bar | IAV | Impairing the export of ribonucleotides | Botwina et al. (2020) |

| Camptothecin, a quinoline alkaloid | Camptotheca acuminata | Alkaloids | Bark | EV71 | Protein expression was suppressed | Wu et al. (2004) |

| Harman alkaloid | Ophiorrhiza nicobarica | Alkaloids | Herpes virus | Inhibition of replication, inhibits plaque formation and delays the eclipse phase of | Gurjar and Pal (2024) | |

| Isoquinoline alkaloid thalimonine | Thalictrum Simplex L | Alkaloids | Aerial parts | Influenza A virus | by reducing the expression of virus-specific protein synthesis | Serkedjieva and Velcheva (2003) |

| Lycorine | Lycoris radiate L. | Alkaloids | Bulbs | SARS-CoV, H5N1 | Block assembly, Inhibiting viral RNA-dependent RNA polymerase activity | Li et al. (2005), He et al. (2013), Jin et al. (2021) |

| Piperine | Piper longum L. | Alkaloids | Seed | VSV-IN, PIV, and HBV | Inhibit the secretion of HBsAg and HBeAg of HBV | Jiang et al. (2013), Kumari and Priya (2017) |

| Skimmianine | Zanthoxylum chalybeum | Alkaloids | Seed | Swartz and Edmonston measles virus | Suppresses virus | Olila et al. (2002) |

| Solamargine and michellamine B, glycoalkaloids | Solanum khasianum | Alkaloids | Berries | HIV. | Prevent virus multiplication | Gurjar and Pal (2024) |

| Oils | Fortunella margarita | Essential Oils | Fruit | H5N1 IAV | Antiviral plant natural products | Ibrahim et al. (2015) |

| Sandalwood oil | Santalum album Linn. | Essential Oils | Heartwood | HSV-1 | Prevent adsorption | Khan Yusuf and Sen Das (2023) |

| Tea tree oil | Tea tree (Melaleuca alternifolia) | Essential Oils | Leaves | IAV | Viral adsorption inhibited | Garozzo et al. (2011) |

| Silvestrol is a flavagline compound | Aglaia foveolata | Flavaglines | Fruits and Twigs | Ebola virus, human coronavirus, MERS-CoV, Human rhinovirus A1 and poliovirus, Zika virus | Preventing protein translation | Müller et al. (2018) |

| 5,7-dihydroxy −3,6,4-trimethoxy, flavone-7-O-α-L xylopyranosyl (1→3)-O-α-L arabinopyranosyl- (1→4)-O-β-D galactopyranoside | Butea monosperma (Lam.) Taub. | Flavonoids | All plant part | EV-71 | Inhibit virus activity | Panda et al. (2017), Tiwari et al. (2019) |

| Baicalein and baicalin, flavonoids | Scutellaria baicalensis Georgi | Flavonoids | Dried root | HIV | It interacted with HIV envelope glycoproteins and chemokine coreceptors to prevent virus entrance into CD4 cells and limit HIV-1 replication | Li et al. (2000) |

| bioflavonoid quercetin | Carica papaya | Flavonoids | leaves | DENV | Antiviral and platelet-protective properties | Shrivastava et al. (2022) |

| Calanolide A | Calophyllum lanigerum | Flavonoids | Leaves and twigs | HIV-1 | Inhibits reverse transcriptase | Buckheit et al. (1999) |

| Camelliiatannin | Camellia japonica | Flavonoids | Pericarp | HIV | Prevent virus attachment and penetration. | Park et al. (2002) |

| Epigallocatechin-3-gallate, epicatechin gallate, epicatechin and catechin | Camellia sinensis (L.) Kuntze | Flavonoids | Leaf | HIV, HSV-I, IAV, HCV, HBV, VSV, Reovirus, DENV, JEV, CHIKV, ZIKV, TBEV, EV71, Rotavirus | Inhibit influenza virus replication Inhibit reverse transcriptase | Song et al. (2005), Xu et al. (2017) |

| Flavonol iridoid glycosides luteoside | Barleria prionitis | Flavonoids | Leaves | RSV | Inhibit virus actvity | Chen et al. (1998), Gurjar and Pal (2024) |

| Hesperidin, luteolin, and vitamin C | Citrus sinensis (L.) Osbeck | Flavonoids | Fruit | HAV, SARS-CoV-2 | Inhibit, spike protein formation | Battistini et al. (2019), Bellavite and Donzelli (2020), Goyal et al. (2020) |

| Kaempferol-3-O-(6″-O-Ep- coumaroyl)- β-D-glucopyranoside | Bombax ceiba L. | Flavonoids | Flower | RSV, SARS-CoV-2 | Inhibit cytopathic effect of RSV | Zhang et al. (2003), Schwarz et al. (2014) |

| Mangiferin | Mangifera indica L. | Flavonoids | Fruit | Human influenza virus, HSV-I, HIV | Inhibit HSV-1 virus duplication | Al-rawi et al. (2019) |

| (+)-cycloolivil-4′-O-β-dglucopyranoside, swertiachiralatone A, swertiachoside A, swertiachirdiol A, and swertiachoside B | Swertia angustifolia var. pulchella (D. Don) Burkill | Glycosides | Whole plant | HBV, HSV-I | Inhibit HBsAg and HBeAg secretion and HBV DNA replication | Verma et al. (2008), Zhou et al. (2015) |

| (+)-pinoresinol 4-O-(6″- O-vanilloyl)-β-D-glucopyranoside 6′-O-vanilloyltachioside 6′-Ovanilloyl- isotachioside | Calotropis gigantean (L.) Dryand. | Glycosides | Latex | H1N1 | Inhibit NF-κB pathway and viral ribonucleoproteins | Parhira et al. (2014) |

| Forsythoside A | Forsythia suspensa | Glycosides | Fruit | H1N1 | Inhibitory of viral replication | Law et al. (2017) |

| Geraniin and 1,3,4,6-tetra-O-galloyl-betad- glucose (1346TOGDG) | Phyllanthus urinaria | Glycosides | Acetone extract | HSV-1, HSV-2 | Suppressed virus multipliaction | Yang et al. (2007) |

| Maltol 60-b-D-apiofuranosyl-b-Dgluco- pyranoside, and grevilloside G | Hedyotis scandens Roxb. | Glycosides | Whole plant | RSV | Inhibit virus actvity | Wang et al. (2013) |

| Phyllanthin, and hypophyllantin | Phyllanthus niruri L. | Glycosides | Whole plant | HBV, WHV, HCV | Bind to protein of HCV leading to interference in viral entry to host cells | Tan et al. (2013), Wahyuni et al. (2019) |

| Podophyllotoxin | Podophyllum peltatum L. | Glycosides | Aquous extract | HSV-1 | Bedows and Hatfield (1982) | |

| Progoitrin | Isatis indigotica | Glycosides | Sun-dried roots | H1N1 | Neutralize the influenza virus strain | Nie et al. (2020) |

| Torvoside H | Solanum torvum | Glycosides | Fruit | HSV-1 | Inhibit virus activity | Arthan et al. (2002) |

| Anolignan A Anolignan B | Anogeissus acuminata (Roxb. Ex DC.) Wall. ex Guillem. & Perr | Lignans | Stem | HIV | Inhibit HIV-I reverse transcriptase | Rimando et al. (1994), El-Ansari et al. (2020), Bachar et al. (2021) |

| Lignans like Schizarin B, Taiwanschirin D, and Rhinacanthin E and F | Justicia procumbens, Pelargonium peltatum, Kadsura matsudai | Lignans | Different plant part | HIV, Hepatitis B, Influenza A | Preventing the virus from replicating. | Bekhit and Bekhit (2014), Gurjar and Pal (2024) |

| Matairesinol and harman | Symplocos setchuensis | Lignans | Stems | HIV | Prevent virus replication | Ishida et al. (2001) |

| Strictinin, shephagenin, and hippophaenin | Shepherdia argentea | Lignans | Leaf | HSV-1, HIV | Reverse transcriptase inhibitors and inactivating transport proteins | Yoshida et al. (1996), Gurjar and Pal (2024) |

| Trychnobiflavone | Strychnos pseudoquina | Lignans | Stem bark | HSV-1 | Reduced HSV-1 protein expression | Thomas et al. (2021) |

| Shuanghuanglian | Chinese traditional medicine extracted from the herbs Lonicera japonica, Scutellariia baicalensis and Forsythia suspense | Mixture | Mixture of many plants | SARSCoV-2 | Antiviral activities in a cell-based system | Su et al. (2020) |

| Meliacine, a cyclic peptide | Melia azedarach | Peptides | leaf | Foot and mouth disease virus VSV, and HSV-I | Inhibition of foot and mouth disease virus | Wachsman et al. (1998) |

| (+)-catechin, and protocatechuic acid | Albizia procera (Roxb.) Benth. | Phenolics | Bark | HIV | Inhibit integrase enzyme of human influenza virus-I | Panthong et al. (2015) |

| Chrysophanate and chrysophanic acid | Pterocaulon sphacelatum and Dianella longifolia | Phenolics | Poliovirus 2 and 3 | Impede the replication | Gurjar and Pal (2024) | |

| Coumarins (2H-chromen-2-on) | Tonka beans, liquorice, cassia, etc | Phenolics | Different plant part | HSV-1 | Stimulate macrophages | Hassan et al. (2016) |

| Coumestan | Eclipta prostrata L. | Phenolics | Leaf | HCV | Inhibit HCV NS5B protein leading to RNA replication | Kaushik-Basu et al. (2008) |

| Curcumin | Curcuma longa | Phenolics | Rhizome | HBV, SARS-CoV-2, HIV, IAV, DENV, CHIKV, VSV, ZIKV, Kaposi sarcoma associated HSV, RSV | Inhibiting HCV protein expression, and replication of other viruses | Kim et al. (2009), Chen et al. (2012), Jennings and Parks (2020), Sharifi et al. (2020), Bachar et al. (2021), Thimmulappa et al. (2021) |

| Eugeniin | Syzygium aromaticum L. | Phenolics | Clove | HSV-1, COVID-19 | - | Vicidomini et al. (2021), Gurjar and Pal (2024) |

| Feralolide, 9-dihydroxyl-2-O-(z)- cinnamoyl-7-methoxy-aloesin, aloeresin, quercetin, catechin hydrate, and kaempferol | Aloe vera (L.) Burm.f. | Phenolics | Leaf | SARS-CoV-2, H1N1, H3N2 | Inhibit the main protease (3CLpro) responsible for the replication of SARS-CoV-2 | Choi et al. (2019), Mpiana et al. (2020) |

| Geraniin | Phyllanthus amarus | Phenolics | Leaf | HIV | Blocks reverse transcriptase | Notka et al. (2004) |

| Honokiol | Magnolia officinalis | Phenolics | Bark | HCV | Interfering with the HCV life cycle | Gurjar and Pal (2024) |

| Hypericin | Hypericum perforatum L. | Phenolics | Leaves | SARS-CoV-2 | Direct virus-blocking effect against SARS-CoV-2 virus particles | Mohamed et al. (2022) |

| Indole-3-carboxylic acid, dihydroxyoleanoic acid, and Begonanline | Begonia nantoensis | Phenolics | Rhizome | HIV | Inhibit virus replication | Wu et al. (2004) |

| Oligophenols | Stylogne cauliflora | Phenolics | Plant extract | HCV | Inhibit protease activity | Cadman (1959), Hegde et al. (2003), Gurjar and Pal (2024) |

| Oxyresveratrol | Artocarpus lakoocha and Millettia erythrocalyx | Phenolics | Heartwood and leaves | HSV, HIV-1 | Effective inhibitor of poliovirus genomic | Likhitwitayawuid et al. (2005) |

| Phenanthrene | Bletilla striata | Phenolics | Rhizomes | H3N2 | Reduction in transcription of viral matrix protein mRNA | Shi et al. (2017) |

| Polyphenols | Geranium sanguineum L. | Phenolics | Plant extract | SARS-CoV-2, Herpes virus | Hindering viral replication by inhibiting enzymes like DNA polymerase and reverse transcriptase | Abarova et al. (2024), Gurjar and Pal (2024) |

| Polyphenols and proanthocyanidins | Hamamelis virginiana | Phenolics | Bark | HSV-1, HIV-1 | Exhibit reverse transcriptase activity | Erdelmeier et al. (1996) |

| Proanthocyanidin A-1 | Vaccinium vitis-idaea | Phenolics | Dried whole plants | HSV-2 | Attachment and infiltration | Cheng et al. (2005) |

| Eugenol, 1,8- cineole and, rosmarinic acid | Ocimum tenuiflorum L. | Phenolics | Aerial part | HSV-I, II | Inhibit replication of HSV-I and II | Caamal-Herrera et al. (2016), Tshilanda et al. (2020) |

| L-galactan hybrid C2S-3 | Cryptonemia crenulata | Polysaccharides | Red alage | Dengue virus | Anti-viral activity | Talarico et al. (2007) |

| Polysaccharides | Rhizophora mucronata | Polysaccharides | Bark and leaves | HIV | Budding prevented | Asres et al. (2005) |

| Cyanovirin N (CV-N) (an 11-kDa protein) | Nostoc ellipsosporum. | Proteins | Blue green alage | HIV-1 | Inhibiting HIV infection | Boyd et al. (1997) |

| Griffithsin | Griffithisia sp. | Proteins | Red alage | HIV, MERS-CoV | Antibody-dependent neutralization of HIV-1 particles | Emau et al. (2007), Millet et al. (2016) |

| Hydrolysed peptides AIHIILI and LIAVSTNIIFIVV | Quercus infectoria | Peptides | Fruit and peel | HIV-1 | Against RT | Seetaha et al. (2021) |

| Lectins like MAP30, GAP31 and jacalin | Momordica charantia, Gelonium multiflorum, Artocarpus heterophyllus | Proteins | Leaf and fruit | HIV, CMV | Ribosomal binding and other activty | Amirzadeh et al. (2023), Gurjar and Pal (2024) |

| Garlic oil, alliin, garlicin, and lectin, etc | Allium sativum L. | Sulfur Compounds | Bulb | ADV-3, SARS-CoV-2, HSV-I, H1N1, HIV-1 | Inhibit virus by diminishing inflammation by suppressing oxidative stress | Rouf et al. (2020), Bachar et al. (2021) |

| Tannins | Bergenia ligulata, Phaseolus vulgaris | Tannins | Rhizome and leaf extracts | Influenza, HIV | Suppress RNA and protein synthesis in a dose-dependent way | Gurjar and Pal (2024) |

| Andrographolide | Andrographis paniculata (Burm.f.) | Terpenoids | Leaf | HSV-I, HIV, and EBV | Inhibit the expression enveloped glycoproteins, induce lymphocyte | Jayakumar et al. (2013) |

| Arganine C, a triterpene | Tieghemella heckelii | Terpenoids | Fruit | HIV | Inhibits HIV entry | Gosse et al. (2002) |

| Essential oil (Humulene epoxide, and caryophyllene oxide) | Cyperus rotundus L. | Terpenoids | Rhizome | SARS-CoV-2, HAV HSV-I, CVB |

Inhibit four target proteins of SARS-CoV-2 such as spike, glycoprotein, papain-like protease ( | Samra et al. (2020), Amparo et al. (2021) |

| Eucalyptus oil and terpinen-4-oil | Eucalyptus species | Terpenoids | Fresh leaves | HSV-1, HSV-2 | Prevent adsorption | Mieres-Castro et al. (2021) |

| Gedunin, pongamol, and azadirachtin | Azadirachta indica A.Juss. | Terpenoids | Bark and leaf | HSV-I, HBV, SARS-CoV-2 | Inhibit NS3 RNA polymerase and NS3 protease helicase | Alzohairy (2016), Rao and Yeturu (2020), Nesari et al. (2021) |

| Gingeronone A | Zingiber officinale Roscoe | Terpenoids | Rhizome | SARS-CoV-2 | Inhibit SARS-CoV-2 | Pandey et al. (2021) |

| Guaiol | Piper nigrum L | Terpenoids | Seed | VSV-IN, PIV, and SARS-CoV-2 | Inhibit 6LU7 and 7JTL of SARS-CoV-2 | Kumari and Priya (2017), Pandey et al. (2021) |

| Illic acid | Laggera pterodonta | Terpenoids | Total plants | H1N1, H3N2, H6N2 | inhibits the early stage of the virus replication. | Wang et al. (2015) |

| Pandanin | Pandanus amaryllifolius Roxb. | Terpenoids | leaves | HSV-1, H1N1 | Ooi et al. (2004) | |

| Phorbol ester, hop-8 | Ostodes katharinae | Terpenoids | Dried leaves | HIV-1 and HIV-2 | Vif-mediated degradation | Chen et al. (2017) |

| Flacourtosides A and E, betulinic acid 3β-caffeate, and scolochinenoside D | Flacourtia indica (Burm.f.) Merr. | Triterpenoids | Stem bark | DENV, CHIKV | Inhibit RNA polymerase | Bourjot et al. (2012) |

| Glycyrrhizin | Glycyrrhiza uralensis | Triterpenoids | Root | SARS-CoV | Replication and block assembly | Cinatl et al. (2003) |

| Oleanolic acid | Achyranthes aspera L. | Triterpenoids | Leaf | HSV-I and II | Inhibited the early stage of multiplication and protease enzyme activity | Mukherjee et al. (2013), Tshilanda et al. (2020), Bachar et al. (2021) |

| Triterpene vaticinone | Vatica cinerea | Triterpenoids | Leaves and Stem | HIV-1 | Prevent adsorption and replication | Zhang et al. (2003) |

| Triterpenoid betulinic acid | Caesalpinia minax | Triterpenoids | Seed | HIV, Parainfluenza 3 virus | Anti-viral activity | Chattopadhyay and Naik (2007) |

| Ursolic acid | Geum japonicum | Triterpenoids | Whole plant | HIV | Inhibits the action of the HIV-1 protease enzyme | Xu et al. (1996) |

Detail of some plant products use to control the human affecting viral diseases.

Polysaccharides from plants such as Echinacea, for example, can stimulate macrophages and natural killer (NK) cells. PNPs play a crucial role in modulating the immune system through their anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, immunomodulatory, antimicrobial, and adaptive immunity-enhancing properties (Ferrucci et al., 2024; Nikiema et al., 2024). Plant antioxidants, such as polyphenols, can mitigate oxidative stress and protect cells from viral damage. Quercetin, found in apples and onions, is a potent antioxidant that enhances the function of the immune system. Anti-inflammatory effects also play a role, as chronic inflammation can weaken immune responses. The PNPs exhibit anti-inflammatory properties by modulating the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines and enzymes, which remain the main mechanisms of their action (Alarabei et al., 2024; Wu et al., 2024). Compounds like curcumin from turmeric help maintain immune balance by reducing excessive inflammation. The active component of Curcumin from turmeric shows anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, and enhances antibody responses. For example, curcumin from turmeric inhibits the activity of nuclear factor-kappa B (NF-κB), a key regulator of inflammation. PNPs, particularly flavonoids and phenolics, scavenge free radicals, reducing oxidative stress and protecting immune cells from damage (Hooda et al., 2024). Furthermore, some plant compounds enhance the production and activity of interferons, which are essential for the antiviral immune response. Carpaine, an alkaloid from papaya leaves, has demonstrated notable anti-thrombocytopenic activity, offering potential for managing Dengue Virus (DENV) by modulating cytokine responses and platelet levels. Studies indicate that carpaine significantly increases blood platelet counts in DENV-infected individuals by upregulating the expression of platelet-activating factor receptor and arachidonate 12-lipoxygenase genes (Zunjar et al., 2016; Anjum et al., 2017; Kapoor, 2017; Sarker et al., 2021; Munir et al., 2022). Advanced phytochemical analyses have identified several metabolites in Carica papaya leaf extract, including quinic acid, malic acid, caffeoyl malate, quercetin, p-coumaroyl malate, clitorin, rutin, feruloyl malate, nicotiflorin, and carpaine (Kasture et al., 2016; Ayodipupo Babalola et al., 2024). The diverse bioactive compounds of PNPs interact with various components of the immune system, making them valuable in promoting overall health and resilience against diseases (Frazzoli et al., 2023; Gasmi et al., 2023; Kussmann et al., 2023). However, it is crucial to note that the PNP dosage intake, effectiveness, and safety can all vary, and further investigation is needed to understand their processes and possible therapeutic uses properly.

Application of PNP to control human viral infection

Plant-derived natural products play a crucial role not only in drug discovery but also in enhancing human immunity against pathogens. As challenges in developing chemical-based antiviral treatments continue, plant extract or fraction are increasingly recognized as safe and affordable alternatives to traditional antiviral medications (Elshafie et al., 2023). These compounds offer a range of antiviral properties and contribute to bolstering the immune system. Several studies highlight the potential of plant-derived compounds in the prevention and treatment of viral infection (Pebam et al., 2022). For instance, according to Chassagne et al. (2021), natural compounds that have been extracted from a variety of plants may help improve the development flow and yield novel drugs (Chassagne et al., 2021). Studies have shown that several medicinal plants with antiviral properties, including Andrographis paniculata, Lindera chunii, Dioscorea bulbifera, Wisteria floribunda, Xanthoceras sorbifolia, and Aegle marmelos, exhibit significant anti-HIV activity (Kaur et al., 2020). Additionally, various plant-derived compounds from different chemical groups have demonstrated potential anti-HBV activity (Wu, 2016). Unlike conventional antivirals and antibiotics that target pathogens broadly, plant-based medications may offer more specific mechanisms of action against viruses. For instance, quercetin, a well-known flavonoid available as a dietary supplement, is commonly used to boost immunity, manage allergies, and improve general health. It has been shown to inhibit the replication of several viruses, including influenza, herpes simplex, and hepatitis C viruses (Agrawal et al., 2020).

Despite the availability of antiviral medications and vaccines, effectively controlling infections remains challenging due to the unique characteristics of each virus and the limited number of approved antiviral drugs (Adamson et al., 2021; Cheung et al., 2024; Mahmoudieh et al., 2024). This has driven increased interest in plant-based treatments, as PNPs exhibit diverse bioactive properties, including antiviral effects. Research supports the use of plant-based medications in treating viral infections (Chassagne et al., 2021). Advances in genetic engineering and molecular breeding in plantations have facilitated the development of potential treatments for viruses such as SARS-CoV-2. Recent studies indicate that plant extracts possess therapeutic potential against the COVID-19 strain (Jalal et al., 2021; Mukherjee et al., 2024), suggesting that the therapeutic effects of plant extracts on COVID-19 highlight their significance in managing viral infections.

Even though, the presence of over 220 identified human viruses and the limited number of clinical approvals for antiviral drugs are major concerns (Adamson et al., 2021; Cheung et al., 2024). Each virus’s unique characteristics and behaviors require customized medications or therapies, which can be challenging. Additionally, rapid viral genome evolution contributes to the emergence of several mutants in the virus leading to antiviral resistance and complicating treatment efforts (Ghaebi et al., 2020). Research on compounds such as K22, which has demonstrated strong anti-CoV activity by reducing endoplasmic reticulum zippering, offers promising insights into overcoming these challenges (Bills et al., 2023).

Humans have used herbs and supplements to treat illnesses since ancient times. Even today, influenza and coronavirus vaccinations are not 100 percent effective, so the immune system can use all the help it can get from antiviral herbs. Some of the best antiviral herbs and supplements have been used therapeutically to manage symptoms of coronavirus (Saddiqa et al., 2024). Some prevalent plant natural products that help ameliorate the effects of viral infections in humans include quercetin, resveratrol, echinacea, allicin, and epigallocatechin gallate (Lin L. T. et al., 2014; Adeosun and Loots, 2024) (Table 1).

Polyphenols prevent viral infection of host cells by disturbing virus adsorption and attachment and by suppressing reverse transcriptase and RNA polymerase activity in HIV and influenza virus attacks (Chojnacka et al., 2021). Resveratrol, is a potent polyphenolic compound, found in grapes and red wine, exhibits antiviral properties against several viruses, including influenza and herpes simplex virus, by inhibiting viral protein synthesis (Abba et al., 2015). Baicalein and luteolin are two flavones, a family of polyphenolic compounds, whose antiviral properties have also been well studied. Baicalein substantially effect viral DNA synthesis and reduced human cytomegalovirus (HCMV) early and late protein levels (Croft, 1998). Luteolin exhibits antiviral activity against viruses like the poliovirus and coxsackievirus and has antimicrobial properties that help fight bacterial and viral infections (Zakaryan et al., 2017). Polyphenols Epigallocatechin gallate, derived from green tea, has potent antiviral effects against viruses such as hepatitis B and C, influenza, and herpes, partly through inhibiting viral entry and replication (Wang et al., 2021). Echinacea is widely used in traditional medicine and contains various secondary metabolites, primarily phenolics (such as caffeic acid derivatives) and polysaccharides, which can boost immune function. It has also been shown to reduce the duration and severity of colds and other respiratory infections (Karsch-Völk et al., 2014). Curcumin, a natural polyphenolic compound and the primary ingredient in turmeric, is known for its ability to eliminate human viruses such as H5N1, SARS-CoV-2, HIV-1 & HIV-2, influenza, HSV-1 & HSV-2, coxsackievirus, hepatitis B, and other pathogens. (Babaei et al., 2020; Bormann et al., 2021; Sahoo et al., 2021; Srivastava et al., 2022). The basil (Ocimum sanctum), or tulsi, contains many flavonoids such as orientin, vicenin, eugenol, rosmarinic acid, and luteolin, which contribute to its medicinal properties. Tulsi’s antiviral properties make it a valuable herbal remedy for managing and preventing viral infections by inhibiting viral replication, modulating the immune system, reducing inflammation, and providing antioxidant support including Influenza-A, flu A subtype H9N2, HSV1, HSV2, ADV-8, CVB1, EV71, ADV-3, ADV-II, HIV-1, HIV-2, HPV, HCV, DEN-1 & 2, DNA, and RNA viruses, and SARS-CoV-2 (Bhattacharya et al., 2024; Jayashankar et al., 2024; Rani, 2024; Sao et al., 2024). Coumarins from Calophyllum lanigerum and C. inophyllum have been shown to inhibit reverse transcriptase and are effective against HIV-1 (Sharapov et al., 2023). Black tea phenolics such as tannic acid, 3-isotheaflavin-3-gallate, and theaflavin-3,3′-digallate, as well as phenolics from Isatis indigotica like hesperetin, and have exhibited inhibitory effects against various viruses (Salasc et al., 2022b; Sezer et al., 2022; Gamil and Abeer, 2023). Strychnobiflavone is a bioactive flavonoid compound derived from the bark of Strychnos pseudoquina, known for its ability to inhibit HSV-1 virus and its associated disease (Thomas et al., 2021).

Different alkaloids like Isoquinoline alkaloid thalimonine, berberine, Camptothecin, Harman, Gingeronone A, alkaloid isolated from Zanthoxylum chalybeum, Thalictrum Simplex L, Berberis vulgaris, Camptotheca acuminata, Ophiorrhiza nicobarica, Camellia sinensis (L.) Kuntze, Zingiber officinale Roscoe, used to control the viral diseases like Swartz and Edmonston measles virus, Influenza A virus, IAV, EV71, Herpes virus (Olila et al., 2002; Serkedjieva and Velcheva, 2003; Wu et al., 2004; Song et al., 2005; Xu et al., 2017; Botwina et al., 2020; Pandey et al., 2021; Gurjar and Pal, 2024). Lycorine is a natural alkaloid from Lycoris radiata L., showed anti-SARS-CoV activity (Li et al., 2005). Sanguinarine, alkaloid derived from the bloodroot plant (Sanguinaria canadensis), has potential antiviral effects against hepatitis C virus (HCV) and herpes simplex virus (HSV) by inhibiting viral RNA synthesis and blocking viral protein expression, enhancing the host’s immune response to viral infections (Croaker et al., 2016; Wink, 2020).

Artemisinin, a terpenoid derived from Artemisia annua, is used in treating malaria and has shown antiviral activity against hepatitis B and C viruses (Uzun and Toptas, 2020). Oregano (Origanum vulgare), a popular herb from the mint family, has medicinal properties. Its oil’s active components, such as carvacrol and thymol, possess antiviral properties and disrupt the lipid envelopes of viruses, leading to the inactivation of the virus, allowing it to treat murine norovirus (MNV) (Gilling et al., 2014; Solis-Sanchez et al., 2020; Mohanty and Murhekar, 2024). Andrographolide, a diterpene lactone found in Andrographis paniculata, has shown antiviral properties against influenza, hepatitis C, and dengue viruses (Kaushik et al., 2021). Components like Andrographolide, Oleanolic acid, Phorbol ester, hop-8, etc., isolated from the leaf of A. paniculata, Justicia adhatoda L., Achyranthes aspera L., Ostodes katharinae., protect against viruses like HSV-I, HIV, SARS-CoV-2, and EBV (Jayakumar et al., 2013; Mukherjee et al., 2013; Chavan and Chowdhary, 2014; Chen et al., 2017; Tshilanda et al., 2020; Bachar et al., 2021; Ghosh et al., 2021). Bel (Aegle marmelos), plant is an important ethanobotanical use in Indian culture. Seselin, a compound isolated from A. marmelos (L.) Corrêa showed effective against SARS-CoV-2 (Bachar et al., 2021; Nivetha et al., 2022). Licorice, known as “sweet grass,” has been used in traditional Chinese medicine. The plant’s root is the primary source of its antiviral and antibacterial properties. Licorice, frequently used in folk food systems during cold and cough, contains glycyrrhizin from Glycyrrhiza uralensis. Glycyrrhizin, a triterpenoid saponin compound derived from the licorice plant (Glycyrrhiza glabra), has shown activity against a range of viruses, including herpes simplex, hepatitis C, HIV, and SARS-CoV-2, by interfering with virus replication and boosting the immune response (Cinatl et al., 2003; Rizzato et al., 2017; Tseng et al., 2017; Gomaa and Abdel-Wadood, 2021). Celastrol, a quinone methide triterpene obtained from Tripterygium wilfordii root extracts, has shown promise to prevent HCV replication by targeting on the JNK/Nrf2/HO-1 pathway, providing a viable strategy to fight HCV infection (Tseng et al., 2017).

Garlic (Allium sativum L.) has been used for centuries in food and medicine and has been shown to heal viral infections in humans, animals, and plants (Tesfaye, 2021). Studies indicate that garlic can help treat the common cold, flu, viral hepatitis, and even warts (Sasi et al., 2021). Allicin, a sulfur-containing compound derived from garlic, has broad-spectrum antiviral activity, inhibiting viral RNA synthesis and boosting immune cell activity. Bulb of A. sativum L., produces garlic oil, garlicin, and lectin, etc., protects against L. ADV-3, SARS-CoV-2, HSV-I, H1N1, HIV-1 (Rouf et al., 2020; Bachar et al., 2021). Another sulfur-containing compound Progoitrin, a glucosinolate, isolated from the root of I. indigotica protect against H1N1 (Nie et al., 2020).

Essential oils, concentrated extracts from plants, contain various bioactive complex mixture of terpenes, phenolics, and other secondary metabolites that can exert antiviral effects. Some essential oils can directly inactivate viruses by disrupting their lipid envelopes, denaturing proteins, or interfering with viral entry into host cells. They can also inhibit viral replication within host cells by interfering with viral RNA or DNA synthesis and disrupting viral enzyme activity. Additionally, essential oils can enhance the immune response and reduce inflammation associated with viral infections. Different plant oils, such as those from lavender, camphor, peppermint, cinnamon, eucalyptus, tea, and thyme, contain compounds used for antiviral activity (Mohammed Ail, 2021). Specific essential oils with antiviral properties include tea tree oil (Melaleuca alternifolia), which contains compounds like terpinen-4-ol and alpha-terpineol that disrupt viral envelopes and inhibit viral replication of HSV, influenza, and HPV. Eucalyptus oil (Eucalyptus globulus) contains eucalyptol (1,8-cineole), which inhibits viral replication and enhances immune responses against influenza, HSV, and RSV (Garozzo et al., 2009). Peppermint oil (Mentha piperita) has menthol and other compounds that exhibit antiviral activity against HSV, influenza, and adenovirus. Lavender oil (Lavandula angustifolia) contains linalool and linalyl acetate, which can inactivate viruses and reduce inflammation during HSV and influenza infections (Abou Baker et al., 2021). Oregano oil (O. vulgare) is rich in carvacrol and thymol, which have strong antiviral, antibacterial, and antifungal properties, disrupting viral envelopes and inhibiting replication of HSV, rotavirus, and norovirus. Lemon balm oil (Melissa officinalis) part of the mint family, possesses antioxidant, antihistamine, anti-cancer, antibacterial, antifungal, and antiviral properties. Contains compounds like citral and citronellal, which have antiviral effects by inhibiting viral attachment and entry of HSV and enterovirus. Studies indicate that lemon balm essential oil helps treat the influenza virus (Behzadi et al., 2023; de Sousa et al., 2023). Lemon balm also relieves muscle spasms and may slow down HSV-1 (Mazzanti et al., 2008; Astani et al., 2012; Gurjar and Pal, 2024). Different oils viz., Sandalwood oil, Eucalyptus oil, Essential oil (Humulene epoxide, and caryophyllene oxide) Tea tree oil and Terpinen-4-ol from different plants like Cyperus rotundus L. Fortunella margarita, Tea tree (M. alternifolia), Santalum album Linn use against different viral disease. Eucalyptus species are used to control the disease of SARS, HAV, HSV, etc (Garozzo et al., 2011; Ibrahim et al., 2015; Battistini et al., 2019; Bellavite and Donzelli, 2020; Goyal et al., 2020; Samra et al., 2020; Amparo et al., 2021; Khan Yusuf and Sen Das, 2023).

More than 200 extracts from different plants, such as L. radiata, A. annua, Pyrrosia lingua, and Lindera aggregate, have been analyzed and found to have anti-SARS-CoV effects (Omrani et al., 2021; Perera et al., 2021; Salasc et al., 2022a; Gamil and Abeer, 2023; Pal and Lal, 2024; Sezer et al., 2024). Aqueous extract of Carica papaya leaves to treat Dengue fever (Shrivastava et al., 2022). Extracts from folk medicinal plants like Heracleum maximum, Plantago major Linn., and Sambucus nigra L. possess antiviral effects by stimulating macrophage activation (Barak et al., 2001; Chiang et al., 2003; Webster et al., 2006; Mukhtar et al., 2008). Similarly, anti-HCV activity has been observed in methanolic and aqueous extracts of Boswellia carterii, Acacia nilotica L., Embelia schimperi, Trachyspermum ammi L., Quercus infectoria, Piper cubeba L., and Syzygium aromaticum L. (Mukhtar et al., 2008). Astragalus root, a medicinal plant from Asia, is an antiviral agent used to treat avian influenza H9 (Shkondrov et al., 2023). Plant-derived zinc components boost the immune system and have effective antiviral properties, helping to protect the body from HPV, HIV, Picornavirus, Togavirus (Chikungunya), flu, coronavirus, and herpes (Murakami et al., 2007; Read et al., 2019; Khabour and Hassanein, 2021) Ginger (Z. officinale) is a spice packed with antioxidants beneficial to the human immune system’s health. It possesses antimicrobial properties and can fight off various human viruses in diseases such as Chikungunya, Dengue (DENV), SARS-CoV-2, and the human respiratory syncytial virus (HRSV) (Chang et al., 2013; Aboubakr et al., 2016; Kaushik et al., 2020; Mukherjee et al., 2024); Black elderberry (S. nigra), a popular medicinal shrub in Europe, possesses antioxidant properties and boosts the immune system. In vitro studies have shown that black elderberry can slow the spread of influenza A and B, as well as some bacterial lung (Charlebois et al., 2010; Hawkins et al., 2019; Torabian et al., 2019; Seymenska et al., 2023). The tubers of various Dioscorea species have been used to treat different viruses, including herpesvirus, poxvirus, and picornavirus. These extracts work against viruses by binding to the virion particles, preventing their penetration into cells, modifying the cell wall surface to prevent the release of viral replicates, and interfering with the intracellular replication of viruses (Ganjhu et al., 2015). Leaf extracts of Azadirachta indica have shown antiviral activity against several RNA and DNA viruses (Gurjar and Pal, 2024). Aqueous extract from the roots of Carissa edulis (Forssk.) V showed anti-HSV activity (Tolo et al., 2006), while the ethanolic extract of Phyllanthus (Phyllanthus nanus) showed anti-HBV activity (Lam et al., 2006). Whole plants of Cynodon dactylon L. and the leaf of Rosa centifolia L. show inhibitors of viruses like BCoV and HIV respectively (Nalanagula, 2020; Palshetkar et al., 2020; Bachar et al., 2021). Supplemented liquid fermented broth of Ganoderma lucidum with aqueous extract of Radix Sophorae flavescentis strongly showed anti-hepatitis B virus activity (Mukhtar et al., 2008). Hot water extracts of Stevia rebaudiana L. blocked the entry of various infectious HRV viruses (Takahashi et al., 2001).

Not only higher plant products but lower plant-like products of blue-green algae and red algae also help in managing the human attacking viruses. Cyanovirin N (CV-N), an 11-kDa protein product of cyanobacterium Nostoc ellipsosporum, and Griffithsin a red marine algae (Griffithisia sp.) product can develop anti-HIV-1 effect. These molecules neutralize the HIV viruses by inhibiting their infection and antibody based HIV particle neutralization processes (Boyd et al., 1997; Emau et al., 2007; Millet et al., 2016). DL-galactan hybrid C2S-3 derived from different algae Cryptonemia crenulata help to protect the human body from Dengue viruses (Talarico et al., 2007).

Peptides like Meliacine and Hydrolysed peptides AIHIILI and LIAVSTNIIFIVV isolated from Melia azedarach and Q. infectoria leaf and fruit part protect the human body from Foot and mouth disease virus VSV, and HSV-I, HIV-1 viruses (Wachsman et al., 1998; Alché et al., 2003; Seetaha et al., 2021). Lectins of S. nigra, which can administer either orally or parenterally in liquid composition inhibit the activity of several enveloped viruses (Ganjhu et al., 2015). Rhizome of Bletilla striata produce Phenanthrene to inhibit virus H3N2 propagation (Shi et al., 2017). Fruits of Mangifera indica L. and Forsythia suspensa produce Mangiferin and Forsythoside A which work as antiviral compounds against HSV, HIV and H1N1 (Law et al., 2017; Al-rawi et al., 2019).

These plant-derived substances have provided opportunities for creating novel antiviral treatments. However, it is crucial to remember that while many of these substances have shown antiviral activity in laboratory conditions, further clinical research is required to determine their safety and effectiveness in humans.

Limitation and toxicity of PNPs

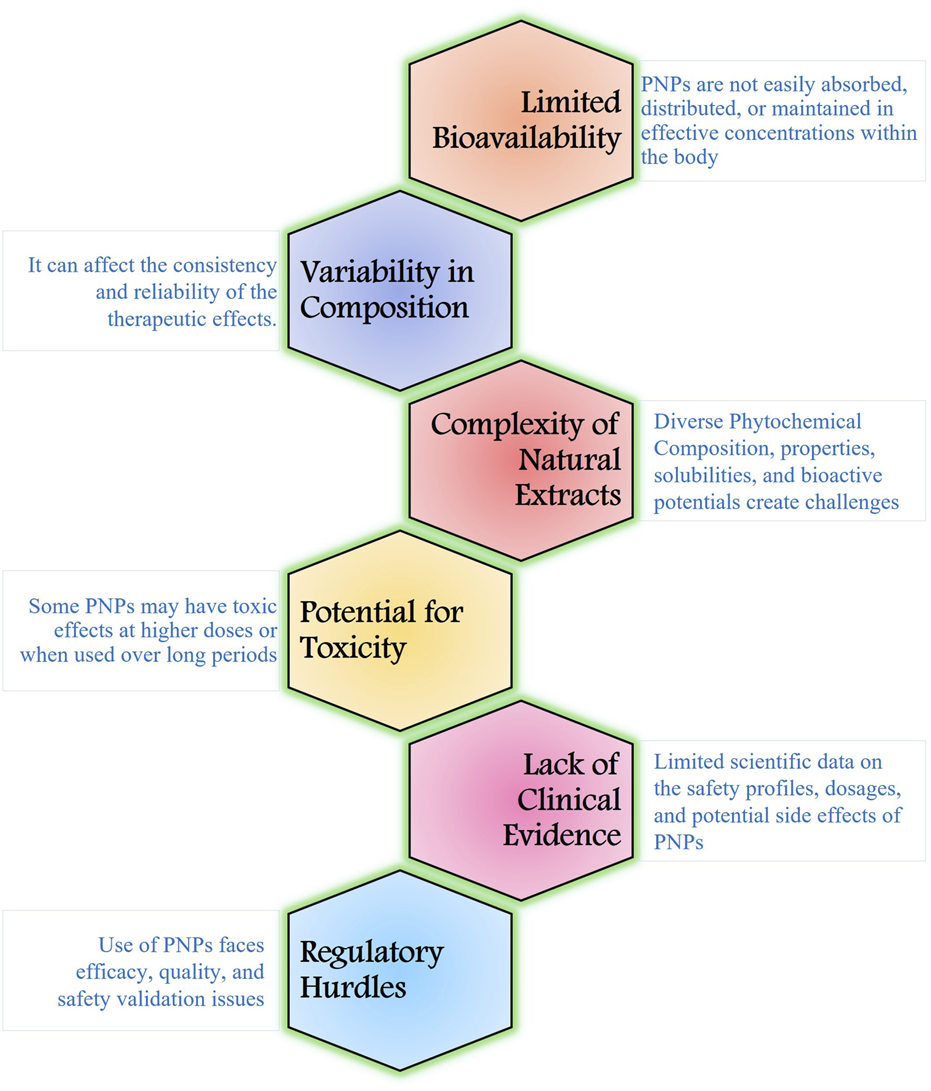

PNPs have shown promise in antiviral drug discovery, but they also have several limitations during viral infections (Figure 3). PNPs often exist as complex mixtures with multiple active compounds. The chemical composition of PNPs can vary significantly depending on the source, growing conditions, and extraction methods. Isolating and identifying the specific components responsible for antiviral activity can be challenging, making standardization difficult. This variability can affect the consistency and reliability of the therapeutic effects (Raskin et al., 2002; Kusumawati, 2021). Many PNPs suffer from poor bioavailability, as they are not easily absorbed, distributed, or maintained in effective concentrations within the body (Kumar S. et al., 2022). This can limit their therapeutic effectiveness. For example, the pharmacokinetics of quercetin in humans showed a low oral bioavailability (∼2%) after a single dosage (Li et al., 2016). The approval process for natural products as therapeutic agents is indeed intricate and lengthy. Regulatory authorities require extensive evidence to validate the efficacy, safety, and quality of PNPs, which can significantly delay their clinical availability. One major challenge is the limited scientific data on the safety profiles of many PNPs, especially concerning long-term use and their effects on vulnerable populations such as pregnant women, children, and the elderly. This lack of comprehensive safety information increases uncertainty about potential toxicity. Furthermore, while numerous PNPs demonstrate promising antiviral effects in vitro, the transition to robust clinical trials is often insufficient. This gap between preclinical findings and clinical validation hinders the acceptance of PNPs as mainstream antiviral therapies.

FIGURE 3

Limitations of using PNPs for widespread adoption and effectiveness.

The potential for toxicity in PNPs is an important consideration when using these substances for therapeutic purposes. Many PNPs are safe at low doses but can become toxic when consumed in larger quantities or when used over long periods. For instance, high doses of raw garlic extract given over an extended period of time could potentially interfere with blood coagulation, cause liver toxicity, and create gastrointestinal problems (Banerjee and Maulik, 2002). Several studies indicate that coumarin-induced hepatotoxicity is relatively infrequent in humans. Clinical research, however, suggests that coumarin therapy may be associated with liver damage, which is frequently seen as high transaminase levels (Pitaro et al., 2022). The safety profile of these compounds must be thoroughly evaluated to avoid adverse effects during treatment. Some individuals may have allergic reactions to specific PNPs. These reactions can range from mild symptoms like rashes or itching to severe anaphylactic reactions such as sesquiterpene lactones, found in plants like chamomile and arnica, these compounds can cause contact dermatitis in sensitive individuals (Paulsen, 2017). Addressing these limitations will enhance the credibility and therapeutic potential of PNPs, paving the way for their integration into modern antiviral treatments.

Conclusion and perspective

Plant-extract products with antiviral activity are gaining attention as safe and affordable alternatives to traditional antiviral medications. These plant-extract products, which include flavonoids, alkaloids, terpenoids, and phenolic compounds, have the ability to inhibit viral lifecycles and stimulate cellular immune responses, making them useful in fighting viral infections. Despite their potential, therapeutic use of PNPs faces several challenges: low natural concentrations, difficulty in identifying active components, slow plant growth rates, environmental dependence, and extinction risks. Addressing these limitations is essential, particularly in the current scenario of rapid viral infections. Biotechnological platforms, such as plant cell and tissue culture technologies, offer crucial solutions for producing large volumes of plant-derived compounds. Enhancing our understanding of biosynthetic pathways and improving supply chains for commercial production are key steps in this process.

Standardization and rigorous quality control are essential for ensuring the consistency and safety of plant-derived products in clinical applications. Research into these compounds not only aids in the development of new antiviral drugs but also helps design more effective treatments by understanding their mechanisms. Combining PNPs with conventional antiviral medications can enhance efficacy and reduce the risk of resistance, offering a synergistic approach to therapy. In-depth studies and clinical trials are necessary to fully explore the antiviral potential of these compounds. Researchers are investigating the relationship between phytochemical structures and antiviral activity through bioassays, but identifying active components in complex natural extracts remains challenging. Effectiveness may also vary within the human body, emphasizing the need for further validation. The ongoing exploration of PNPs holds significant promise for developing innovative antiviral therapies. By enhancing human antiviral responses and providing new pharmacological options, PNPs could play a crucial role in improving public health. Their nutraceutical and therapeutic properties position them as valuable candidates for combating a range of viruses, making continued research into their mechanisms, efficacy, and safety vital for the future of antiviral medicine.

Statements

Author contributions

RS (1st author): Resources, Writing–original draft, Data curation, Methodology, Visualization. ND: Data curation, Methodology, Visualization, Writing–original draft. MS: Data curation, Writing–original draft. HK: Writing–review and editing. RB: Writing–review and editing, Conceptualization. RS (6th author): Conceptualization, Data curation, Visualization, Writing–original draft, Writing–review and editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

Author RS (6th author) was employed by Helix Biosciences.

The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1

Abarova S. Alexova R. Dragomanova S. Solak A. Fagone P. Mangano K. et al (2024). Emerging therapeutic potential of polyphenols from Geranium sanguineum L. In viral infections, including SARS-CoV-2. Biomolecules14, 130. 10.3390/biom14010130

2

Abba Y. Hassim H. Hamzah H. Noordin M. M. (2015). Antiviral activity of resveratrol against human and animal viruses. Adv. Virology2015, 184241–184247. 10.1155/2015/184241

3

Abou Baker D. H. Amarowicz R. Kandeil A. Ali M. A. Ibrahim E. A. (2021). Antiviral activity of Lavandula angustifolia L. and Salvia officinalis L. essential oils against avian influenza H5N1 virus. J. Agric. Food Res.4, 100135. 10.1016/j.jafr.2021.100135

4

Aboubakr H. A. Nauertz A. Luong N. T. Agrawal S. El-Sohaimy S. A.A. Youssef M. M. et al (2016). In vitro antiviral activity of clove and ginger aqueous extracts against feline calicivirus, a surrogate for human norovirus. J. Food Prot.79, 1001–1012. 10.4315/0362-028x.jfp-15-593

5

Adamson C. S. Chibale K. Goss R. J. M. Jaspars M. Newman D. J. Dorrington R. A. (2021). Antiviral drug discovery: preparing for the next pandemic. Chem. Soc. Rev.50, 3647–3655. 10.1039/d0cs01118e

6

Adeosun W. B. Loots D. T. (2024). Medicinal plants against viral infections: a review of metabolomics evidence for the antiviral properties and potentials in plant sources. Viruses16, 218. 10.3390/v16020218

7

Agrawal P. K. Agrawal C. Blunden G. (2020). Quercetin: antiviral significance and possible COVID-19 integrative considerations. Nat. Product. Commun.15, 1934578X20976293. 10.1177/1934578x20976293

8

Alarabei A. A. Abd Aziz N. A.L. Ab Razak N. I. Abas R. Bahari H. Abdullah M. A. et al (2024). Immunomodulating phytochemicals: an insight into their potential use in cytokine storm situations. Adv. Pharm. Bull.14, 105–119. 10.34172/apb.2024.001

9

Alché L. E. Ferek G. A. Meo M. Coto C. E. Maier M. S. (2003). An antiviral meliacarpin from leaves of Melia azedarach L. Z Naturforsch C J. Biosci.58, 215–219. 10.1515/znc-2003-3-413

10

Al-Khayri J. M. Rashmi R. Toppo V. Chole P. B. Banadka A. Sudheer W. N. et al (2023). Plant secondary metabolites: the weapons for biotic stress management. Metabolites13, 716. 10.3390/metabo13060716

11

Al-Rawi A. Dulaimi H. Rawi M. (2019). Antiviral activity of Mangifera extract on influenza virus cultivated in different cell cultures. J. Pure Appl. Microbiol.13, 455–458. 10.22207/jpam.13.1.50

12

Alzohairy M. A. (2016). Therapeutics role of Azadirachta indica (neem) and their active constituents in diseases prevention and treatment. Evid. Based Complement. Altern. Med.2016, 7382506. 10.1155/2016/7382506

13

Amirzadeh N. Moghadam A. Niazi A. Afsharifar A. (2023). Recombinant anti-HIV MAP30, a ribosome inactivating protein: against plant virus and bacteriophage. Sci. Rep.13, 2091. 10.1038/s41598-023-29365-7

14

Amparo T. R. Seibert J. B. Silveira B. M. Costa F. S. F. Almeida T. C. Braga S. F. P. et al (2021). Brazilian essential oils as source for the discovery of new anti-COVID-19 drug: a review guided by in silico study. Phytochemistry Rev. Proc. Phytochemical Soc. Eur.20, 1013–1032. 10.1007/s11101-021-09754-4

15

Anjum V. Arora P. Ansari S. H. Najmi A. K. Ahmad S. (2017). Antithrombocytopenic and immunomodulatory potential of metabolically characterized aqueous extract of Carica papaya leaves. Pharm. Biol.55, 2043–2056. 10.1080/13880209.2017.1346690

16

Arthan D. Svasti J. Kittakoop P. Pittayakhachonwut D. Tanticharoen M. Thebtaranonth Y. (2002). Antiviral isoflavonoid sulfate and steroidal glycosides from the fruits of Solanum torvum. Phytochemistry59, 459–463. 10.1016/s0031-9422(01)00417-4

17

Asres K. Seyoum A. Veeresham C. Bucar F. Gibbons S. (2005). Naturally derived anti-HIV agents. Phytother. Res.19, 557–581. 10.1002/ptr.1629

18

Astani A. Reichling J. Schnitzler P. (2012). Melissa officinalis extract inhibits attachment of herpes simplex virus in vitro. Chemotherapy58, 70–77. 10.1159/000335590

19

Ayodipupo Babalola B. Ifeolu Akinwande A. Otunba A. A. Ebenezer Adebami G. Babalola O. Nwufo C. (2024). Therapeutic benefits of Carica papaya: a review on its pharmacological activities and characterization of papain. Arabian J. Chem.17, 105369. 10.1016/j.arabjc.2023.105369

20

Babaei F. Nassiri‐Asl M. Hosseinzadeh H. (2020). Curcumin (a constituent of turmeric): new treatment option against COVID‐19. Food Sci. & Nutr.8, 5215–5227. 10.1002/fsn3.1858

21

Bachar S. C. Mazumder K. Bachar R. Aktar A. Al Mahtab M. (2021). A review of medicinal plants with antiviral activity available in Bangladesh and mechanistic insight into their bioactive metabolites on SARS-CoV-2, HIV and HBV. Front. Pharmacol.12, 732891. 10.3389/fphar.2021.732891

22

Bajpai R. Srivastava R. Upreti U. K. (2023). Unraveling the ameliorative potentials of native lichen Pyxine cocoes (Sw.) Nyl., during COVID 19 phase. Int. J. Biometeorology67, 67–77. 10.1007/s00484-022-02386-z

23

Baker R. E. Mahmud A. S. Miller I. F. Rajeev M. Rasambainarivo F. Rice B. L. et al (2022). Infectious disease in an era of global change. Nat. Rev. Microbiol.20, 193–205. 10.1038/s41579-021-00639-z

24

Banerjee S. K. Maulik S. K. (2002). Effect of garlic on cardiovascular disorders: a review. Nutr. J.1, 4. 10.1186/1475-2891-1-4

25

Barak V. Halperin T. Kalickman I. (2001). The effect of Sambucol, a black elderberry-based, natural product, on the production of human cytokines: I. Inflammatory cytokines. Eur. Cytokine Netw.12, 290–296.

26

Baseke J. Musenero M. Mayanja-Kizza H. (2015). Prevalence of hepatitis B and C and relationship to liver damage in HIV infected patients attending joint clinical research centre clinic (JCRC), kampala, Uganda. Afr. Health Sci.15, 322–327. 10.4314/ahs.v15i2.3

27

Battistini R. Rossini I. Ercolini C. Goria M. Callipo M. R. Maurella C. et al (2019). Antiviral activity of essential oils against hepatitis A virus in soft fruits. Food Environ. Virol.11, 90–95. 10.1007/s12560-019-09367-3

28

Bedows E. Hatfield G. M. (1982). An investigation of the antiviral activity of Podophyllum peltatum. J. Nat. Prod.45, 725–729. 10.1021/np50024a015

29

Behzadi A. Imani S. Deravi N. Mohammad Taheri Z. Mohammadian F. Moraveji Z. et al (2023). Antiviral potential of melissa officinalis L.: a literature review. Nutr. Metab. Insights16, 11786388221146683. 10.1177/11786388221146683

30

Bekhit A. Bekhit A. (2014). ChemInform abstract: natural antiviral compounds. ChemInform45. 10.1002/chin.201444282

31

Bellavite P. Donzelli A. (2020). Hesperidin and SARS-CoV-2: new light on the healthy function of citrus fruits. Antioxidants (Basel)9, 742. 10.3390/antiox9080742

32

Bhardwaj K. Silva A. S. Atanassova M. Sharma R. Nepovimova E. Musilek K. et al (2021). Conifers phytochemicals: a valuable forest with therapeutic potential. Molecules26, 3005. 10.3390/molecules26103005

33

Bhatla S. C. Lal M. A. (2023). “Secondary metabolites,” in Plant physiology, development and metabolism (Singapore: Springer Nature Singapore), 765–808.

34

Bhattacharya R. Bose D. Maqsood Q. Gulia K. Khan A. (2024). Recent advances on the therapeutic potential with Ocimum species against COVID-19: a review. South Afr. J. Bot.164, 188–199. 10.1016/j.sajb.2023.11.034

35

Bills C. Xie X. Shi P. Y. (2023). The multiple roles of nsp6 in the molecular pathogenesis of SARS-CoV-2. Antivir. Res.213, 105590. 10.1016/j.antiviral.2023.105590

36

Bormann M. Alt M. Schipper L. Van De Sand L. Le-Trilling V. T. K. Rink L. et al (2021). Turmeric root and its bioactive ingredient curcumin effectively neutralize SARS-CoV-2 in vitro. Viruses13 (1914), 1914. 10.3390/v13101914

37

Botwina P. Owczarek K. Rajfur Z. Ochman M. Urlik M. Nowakowska M. et al (2020). Berberine hampers influenza A replication through inhibition of MAPK/ERK pathway. Viruses12, 344. 10.3390/v12030344

38

Bourjot M. Leyssen P. Eydoux C. Guillemot J. C. Canard B. Rasoanaivo P. et al (2012). Flacourtosides A-F, phenolic glycosides isolated from Flacourtia ramontchi. J. Nat. Prod.75, 752–758. 10.1021/np300059n

39

Boyd M. R. Gustafson K. R. Mcmahon J. B. Shoemaker R. H. O'keefe B. R. Mori T. et al (1997). Discovery of cyanovirin-N, a novel human immunodeficiency virus-inactivating protein that binds viral surface envelope glycoprotein gp120: potential applications to microbicide development. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother.41, 1521–1530. 10.1128/aac.41.7.1521

40

Brown B. Ojha V. Fricke I. Al-Sheboul S. A. Imarogbe C. Gravier T. et al (2023). Innate and adaptive immunity during SARS-CoV-2 infection: biomolecular cellular markers and mechanisms. Vaccines11, 408. 10.3390/vaccines11020408

41

Buckheit R. W. Jr. White E. L. Fliakas-Boltz V. Russell J. Stup T. L. Kinjerski T. L. et al (1999). Unique anti-human immunodeficiency virus activities of the nonnucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors calanolide A, costatolide, and dihydrocostatolide. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother.43, 1827–1834. 10.1128/aac.43.8.1827

42

Caamal-Herrera I. Muñoz-Rodriguez D. Madera-Santana T. J. Azamar A. (2016). Identification of volatile compounds in essential oil and extracts of Ocimum micranthum Willd leaves using GC/MS. Int. J. Appl. Res. Nat. Prod.9, 31.

43

Cadman C. H. (1959). Some properties of an inhibitor of virus infection from leaves of raspberry. Microbiology20, 113–128. 10.1099/00221287-20-1-113

44

Carty M. Guy C. Bowie A. G. (2021). Detection of viral infections by innate immunity. Biochem. Pharmacol.183, 114316. 10.1016/j.bcp.2020.114316

45

Chang J. S. Wang K. C. Yeh C. F. Shieh D. E. Chiang L. C. (2013). Fresh ginger (Zingiber officinale) has anti-viral activity against human respiratory syncytial virus in human respiratory tract cell lines. J. Ethnopharmacol.145, 146–151. 10.1016/j.jep.2012.10.043

46

Charlebois D. Byers P. L. Finn C. E. Thomas A. L. (2010). Elderberry: botany, horticulture, potential. Hortic. Rev.37 (37), 213–280. 10.1002/9780470543672.ch4

47

Chassagne F. Samarakoon T. Porras G. Lyles J. T. Dettweiler M. Marquez L. et al (2021). A systematic review of plants with antibacterial activities: a taxonomic and phylogenetic perspective. Front. Pharmacol.11, 586548. 10.3389/fphar.2020.586548

48

Chattopadhyay D. Naik T. N. (2007). Antivirals of ethnomedicinal origin: structure-activity relationship and scope. Mini Rev. Med. Chem.7, 275–301. 10.2174/138955707780059844

49

Chavan R. Chowdhary A. (2014). In vitro inhibitory activity of Justicia adhatoda extracts against influenza virus infection and hemagglutination. Int. J. Pharm. Sci. Rev. Res.25, 231–236.

50

Chen H. Zhang R. Luo R.-H. Yang L.-M. Wang R.-R. Hao X.-J. et al (2017). Anti-HIV activities and mechanism of 12-O-Tricosanoylphorbol-20-acetate, a novel Phorbol ester from Ostodes katharinae. Molecules22, 1498. 10.3390/molecules22091498

51

Chen J. L. Blanc P. Stoddart C. A. Bogan M. Rozhon E. J. Parkinson N. et al (1998). New iridoids from the medicinal plant Barleria prionitis with potent activity against respiratory syncytial virus. J. Nat. Prod.61, 1295–1297. 10.1021/np980086y

52

Chen M. H. Lee M. Y. Chuang J. J. Li Y. Z. Ning S. T. Chen J. C. et al (2012). Curcumin inhibits HCV replication by induction of heme oxygenase-1 and suppression of AKT. Int. J. Mol. Med.30, 1021–1028. 10.3892/ijmm.2012.1096

53

Cheng H.-Y. Lin T.-C. Yang C.-M. Shieh D.-E. Lin C.-C. (2005). In vitro anti‐HSV‐2 activity and mechanism of action of proanthocyanidin A‐1 from Vaccinium vitis‐idaea. J. Sci. Food Agric.85, 10–15. 10.1002/jsfa.1958

54

Cheung Y. Y. H. Lau E. H. Y. Yin G. Lin Y. Cowling B. J. Lam K. F. (2024). Effectiveness of vaccines and antiviral drugs in preventing severe and fatal COVID-19, Hong Kong. Emerg. Infect. Dis.30, 70–78. 10.3201/eid3001.230414

55

Chiang L. C. Chiang W. Chang M. Y. Lin C. C. (2003). In vitro cytotoxic, antiviral and immunomodulatory effects of Plantago major and Plantago asiatica. Am. J. Chin. Med.31, 225–234. 10.1142/s0192415x03000874

56

Choi J. G. Lee H. Kim Y. S. Hwang Y. H. Oh Y. C. Lee B. et al (2019). Aloe vera and its components inhibit influenza A virus-induced autophagy and replication. Am. J. Chin. Med.47, 1307–1324. 10.1142/s0192415x19500678

57

Chojnacka K. Skrzypczak D. Izydorczyk G. Mikula K. Szopa D. Witek-Krowiak A. (2021). Antiviral properties of polyphenols from plants. Foods10, 2277. 10.3390/foods10102277

58

Cinatl J. Morgenstern B. Bauer G. Chandra P. Rabenau H. Doerr H. W. (2003). Glycyrrhizin, an active component of liquorice roots, and replication of SARS-associated coronavirus. Lancet361, 2045–2046. 10.1016/s0140-6736(03)13615-x

59

Constant O. Maarifi G. Blanchet F. P. Van De Perre P. Simonin Y. Salinas S. (2022). Role of dendritic cells in viral brain infections. Front. Immunol.13, 862053. 10.3389/fimmu.2022.862053

60

Croaker A. King G. J. Pyne J. H. Anoopkumar-Dukie S. Liu L. (2016). Sanguinaria canadensis: traditional medicine, phytochemical composition, biological activities and current uses. Int. J. Mol. Sci.17, 1414. 10.3390/ijms17091414

61

Croft K. D. (1998). The chemistry and biological effects of flavonoids and phenolic acidsa. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci.854, 435–442. 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1998.tb09922.x

62

De Sousa D. P. Damasceno R. O. S. Amorati R. Elshabrawy H. A. De Castro R. D. Bezerra D. P. et al (2023). Essential oils: chemistry and pharmacological activities. Biomolecules13, 1144. 10.3390/biom13071144

63

El-Ansari M. Ibrahim L. Sharaf M. (2020). Anti-HIV activity of some natural phenolics. Herba Pol.66, 34–43. 10.2478/hepo-2020-0010

64

Elshafie H. S. Camele I. Mohamed A. A. (2023). A comprehensive review on the biological, agricultural and pharmaceutical properties of secondary metabolites based-plant origin. Int. J. Mol. Sci.24, 3266. 10.3390/ijms24043266

65

Emau P. Tian B. O'keefe B R. Mori T. Mcmahon J. B. Palmer K. E. et al (2007). Griffithsin, a potent HIV entry inhibitor, is an excellent candidate for anti-HIV microbicide. J. Med. Primatol.36, 244–253. 10.1111/j.1600-0684.2007.00242.x

66

Erdelmeier C. A. Cinatl J. Jr. Rabenau H. Doerr H. W. Biber A. Koch E. (1996). Antiviral and antiphlogistic activities of Hamamelis virginiana bark. Planta Med.62, 241–245. 10.1055/s-2006-957868

67

Ferrari C. (2015). HBV and the immune response. Liver Int.35, 121–128. 10.1111/liv.12749

68

Ferrucci V. Miceli M. Pagliuca C. Bianco O. Castaldo L. Izzo L. et al (2024). Modulation of innate immunity related genes resulting in prophylactic antimicrobial and antiviral properties. J. Transl. Med.22, 574. 10.1186/s12967-024-05378-2

69

Frazzoli C. Grasso G. Husaini D. C. Ajibo D. N. Orish F. C. Orisakwe O. E. (2023). Immune system and epidemics: the role of african indigenous bioactive substances. Nutrients15, 273. 10.3390/nu15020273

70

Gamil S. G. Z. Abeer M. A. (2023). “Antiviral plant extracts: a treasure for treating viral diseases,” in Antiviral strategies in the treatment of human and animal viral infections. Editor Arli AdityaP. (London, United Kingdom: Rijeka: IntechOpen).

71

Ganjhu R. K. Mudgal P. P. Maity H. Dowarha D. Devadiga S. Nag S. et al (2015). Herbal plants and plant preparations as remedial approach for viral diseases. Virusdisease26, 225–236. 10.1007/s13337-015-0276-6

72

Garozzo A. Timpanaro R. Bisignano B. Furneri P. M. Bisignano G. Castro A. (2009). In vitro antiviral activity of Melaleuca alternifolia essential oil. Lett. Appl. Microbiol.49 (6), 806–808. 10.1111/j.1472-765x.2009.02740.x

73

Garozzo A. Timpanaro R. Stivala A. Bisignano G. Castro A. (2011). Activity of Melaleuca alternifolia (tea tree) oil on Influenza virus A/PR/8: study on the mechanism of action. Antivir. Res.89, 83–88. 10.1016/j.antiviral.2010.11.010

74

Gasmi A. Shanaida M. Oleshchuk O. Semenova Y. Mujawdiya P. K. Ivankiv Y. et al (2023). Natural ingredients to improve immunity. Pharmaceuticals16, 528. 10.3390/ph16040528

75

Gelderblom H. R. (1996). “Structure and classification of viruses,” in Medical microbiology. Editor BaronS. (Galveston (TX): University of Texas Medical Branch at Galveston).

76

Ghaebi M. Osali A. Valizadeh H. Roshangar L. Ahmadi M. (2020). Vaccine development and therapeutic design for 2019-nCoV/SARS-CoV-2: challenges and chances. J. Cell Physiol.235, 9098–9109. 10.1002/jcp.29771

77

Ghosh R. Chakraborty A. Biswas A. Chowdhuri S. (2021). Identification of alkaloids from Justicia adhatoda as potent SARS CoV-2 main protease inhibitors: an in silico perspective. J. Mol. Struct.1229, 129489. 10.1016/j.molstruc.2020.129489

78

Gilling D. H. Kitajima M. Torrey J. R. Bright K. R. (2014). Antiviral efficacy and mechanisms of action of oregano essential oil and its primary component carvacrol against murine norovirus. J. Appl. Microbiol.116, 1149–1163. 10.1111/jam.12453

79

Gobran S. T. Ancuta P. Shoukry N. H. (2021). A tale of two viruses: immunological insights into HCV/HIV coinfection. Front. Immunol.12, 726419. 10.3389/fimmu.2021.726419

80

Gokhale N. S. Vazquez C. Horner S. M. (2014). Hepatitis C virus. Strategies to evade antiviral responses. Future Virol.9, 1061–1075. 10.2217/fvl.14.89

81

Gomaa A. A. Abdel-Wadood Y. A. (2021). The potential of glycyrrhizin and licorice extract in combating COVID-19 and associated conditions. Phytomedicine plus1, 100043. 10.1016/j.phyplu.2021.100043

82

Gosse B. Gnabre J. Bates R. B. Dicus C. W. Nakkiew P. Huang R. C. (2002). Antiviral saponins from Tieghemella heckelii. J. Nat. Prod.65, 1942–1944. 10.1021/np020165g

83

Gour A. Manhas D. Bag S. Gorain B. Nandi U. (2021). Flavonoids as potential phytotherapeutics to combat cytokine storm in SARS‐CoV ‐2. Phytotherapy Res.35, 4258–4283. 10.1002/ptr.7092

84

Goyal R. K. Majeed J. Tonk R. Dhobi M. Patel B. Sharma K. et al (2020). Current targets and drug candidates for prevention and treatment of SARS-CoV-2 (COVID-19) infection. Rev. Cardiovasc Med.21, 365–384. 10.31083/j.rcm.2020.03.118

85

Gurjar V. K. Pal D. (2024). “Classification of medicinal plants showing anti-viral activity, classified by family and viral infection types,” in Anti-viral metabolites from medicinal plants. Editor PalD. (Cham: Springer International Publishing), 97–195.

86

Hassan M. Z. Osman H. Ali M. A. Ahsan M. J. (2016). Therapeutic potential of coumarins as antiviral agents. Eur. J. Med. Chem.123, 236–255. 10.1016/j.ejmech.2016.07.056

87

Hawkins J. Baker C. Cherry L. Dunne E. (2019). Black elderberry (Sambucus nigra) supplementation effectively treats upper respiratory symptoms: a meta-analysis of randomized, controlled clinical trials. Complementary Ther. Med.42, 361–365. 10.1016/j.ctim.2018.12.004

88

He J. Qi W. B. Wang L. Tian J. Jiao P. R. Liu G. Q. et al (2013). Amaryllidaceae alkaloids inhibit nuclear-to-cytoplasmic export of ribonucleoprotein (RNP) complex of highly pathogenic avian influenza virus H5N1. Influenza Other Respir. Viruses7, 922–931. 10.1111/irv.12035

89

Hegde V. R. Pu H. Patel M. Das P. R. Butkiewicz N. Arreaza G. et al (2003). Two antiviral compounds from the plant Stylogne cauliflora as inhibitors of HCV NS3 protease. Bioorg Med. Chem. Lett.13, 2925–2928. 10.1016/s0960-894x(03)00584-5

90

Hooda P. Malik R. Bhatia S. Al-Harrasi A. Najmi A. Zoghebi K. et al (2024). Phytoimmunomodulators: a review of natural modulators for complex immune system. Heliyon10, e23790. 10.1016/j.heliyon.2023.e23790

91