Abstract

Background:

Acne is one of the most common inflammatory skin diseases associated with sebum hypersecretion and the action of steroid hormones in the skin and the whole body. Sebum secretion is increased due to overexpression or elevated amounts of type I 5α-reductase, leading to inflammation and acne.

Methods:

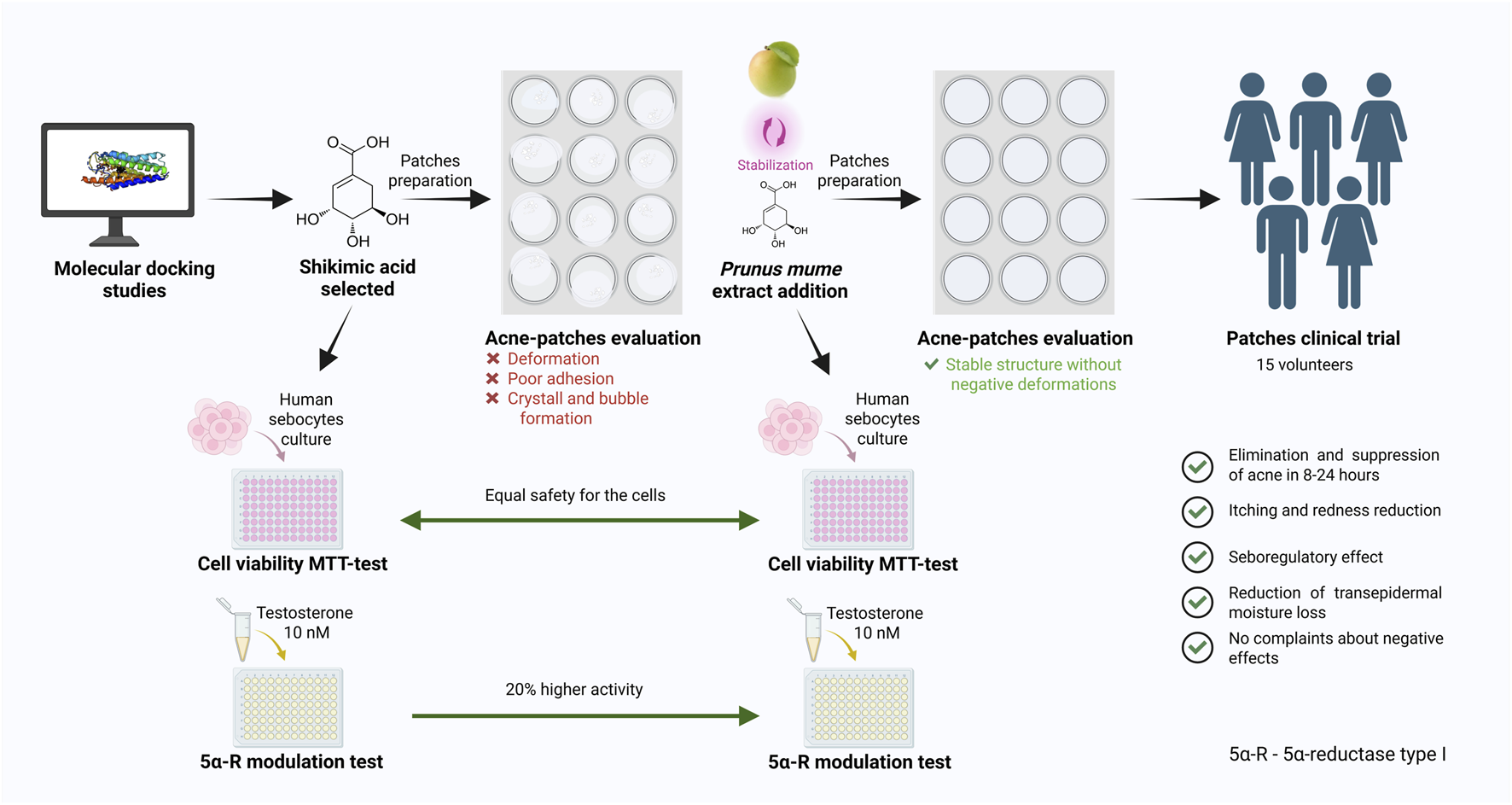

The research was conducted using Prunus mume fruit extract enriched with quercetin and shikimic acid. Type I 5α-reductase was selected as the main target for in silico molecular modelling of phytochemicals. The maximum tolerated concentration was evaluated on human sebocytes using the MTT assay. An in vitro study was performed to determine the effects of shikimic acid and the combination of shikimic acid with Prunus mume fruit extract on the level of type I 5α-reductase in skin sebocytes under testosterone-induced stress, using the ELISA method. Additionally, the stability of the cosmetic formulation containing these phytochemicals was assessed for future clinical research aimed at alleviating signs of inflammation in healthy volunteers, according to international ethical guidelines.

Results:

Based on in silico and in vitro results, shikimic acid was identified as an effective modulator of type I 5α-reductase in skin sebocytes. The addition of Prunus mume fruit extract, enriched with phenolic compounds, enhanced the activity of shikimic acid on type I 5α-reductase. The combination of shikimic acid and Prunus mume extract in a 1:1 mass ratio demonstrated a good cytotoxicity profile within the concentration range of 0.001 to 1.0 wt%, with cell viability ranging from 85% to 100%. Furthermore, at a concentration of 0.03% wt%, the phytochemical combination exhibited a significantly enhanced effect, reducing the amount of type I 5α-reductase to basal levels compared to the testosterone-stimulated group (p < 0.001). This effect was 20% more pronounced than shikimic acid alone (p < 0.001) and 30% higher than salicylic acid and azelaic acid, used as positive controls for acne treatment (p < 0.01). Moreover, Prunus mume extract stabilized shikimic acid in the cosmetic formulation, preventing crystal formation. Clinical research of the cosmetic patches containing these phytochemicals confirmed the absence of adverse skin effects and demonstrated improvement in inflammation signs in healthy volunteers.

Conclusion and discussion:

The study underscores the beneficial effects of combining shikimic acid with Prunus mume fruit extract on testosterone-induced acne lesions, providing significant efficacy and improved stability in cosmetic formulations. The phytochemical combination could be a promising natural modulator that alleviates skin inflammation by modulation of type I 5α-reductase activity. Further research could explore its effects on different stages of acne, leading to the development of novel pharmaceutical and cosmeceutical formulations.

Graphical Abstract

1 Introduction

Acne vulgaris is one of the most common skin problems in adults and adolescents worldwide. Acne affects about 85% of people aged 12–24 years (Bhate and Williams, 2013). Moreover, this pathology is becoming more prevalent every year, with a 5.1% increase in the occurrence of acne between 2006 and 2016 (GBD 2016 DALYs and HALE Collaborators, 2017). It usually occurs during puberty, when sebum production increases due to the sexual hormone activity, but it can also occur in adults from 40 years of age (Khunger and Kumar, 2012; Holzmann and Shakery, 2014; Tanghetti et al., 2014). Although acne is not a dangerous pathology, it causes dermatological and aesthetic discomfort and in some cases can lead to scarring, as well as emotional and psychological distress up to depression (Vasam et al., 2023).

There are currently three main acne treatment approaches: topical treatments, systemic treatments and procedural therapies. Topical treatment is the most affordable and safe of these, as it does not require specialized equipment and eliminates the risk of side effects from oral antibiotics or hormones (Kim and Kim, 2024). This non-invasive approach involves acne management by applying an active ingredient directly to the problem skin area. Various cosmetic products such as creams, serums and the increasingly popular anti-acne patches are used for topical acne treatment (Chularojanamontri et al., 2014; Khan et al., 2024; Yong et al., 2025).

Acne vulgaris is a pathology associated with the progression of inflammation, including that of a bacterial nature. Therefore, the active ingredient of topical acne treatment agents are usually antibiotics, compounds with anti-inflammatory and antibacterial activity like retinoids (Dreno et al., 2022), benzoyl peroxide (Yang et al., 2020), salicylic acid (Chularojanamontri et al., 2014; Lu et al., 2019), clindamycin (Del Rosso et al., 2024), erythromycin (Sayyafan et al., 2020), azelaic acid (Layton and Dias da Rocha, 2023). However, their prolonged use may induce resistance in Cutibacterium acnes and lead to worsening of acne conditions (Zhu et al., 2025; Sutaria et al., 2025; Alkhawaja et al., 2020). Therefore, new promising compounds for acne management, including phytochemicals, are being sought (Kuo et al., 2021; Khan et al., 2024; Yong et al., 2025). Notably, many phytochemicals exhibit significant anti-inflammatory properties which are highly relevant for the treatment of acne and other inflammatory skin conditions (Patel et al., 2025).

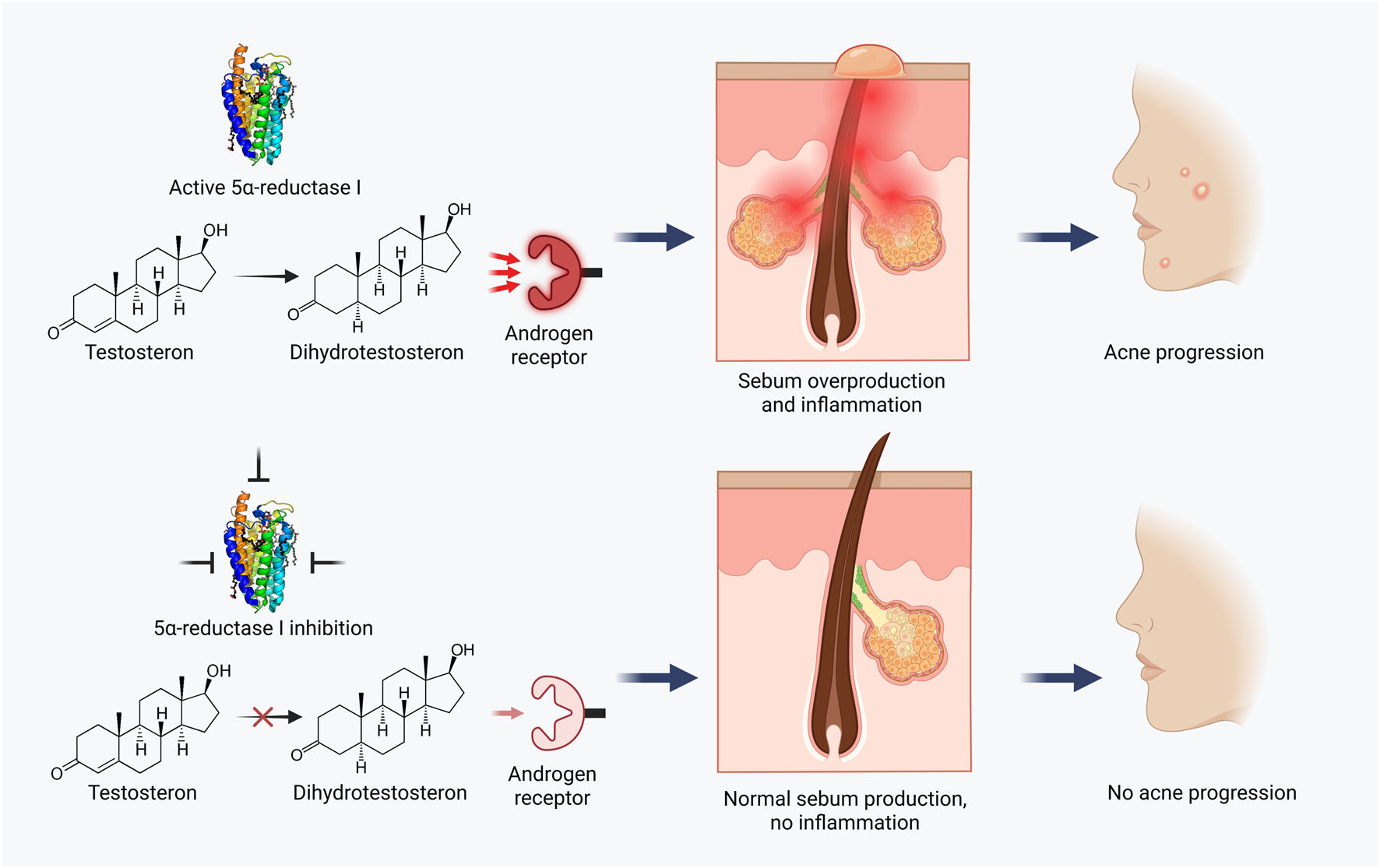

One of the key elements of pathogenesis, and therefore a key drug target, is type I 5-alpha reductase (5α-R) (Escamilla-Cruz et al., 2023). This enzyme converts testosterone to 5α-dihydrotestosterone, which has a strong effect on androgen receptors, increases sebum activity, sebocyte proliferation and inflammation (Wood and Rittmaster, 1994; Marks et al., 2020). Blocking 5α-R activity with inhibitors could prevent acne at its earliest stages (Figure 1). To date, there are only a limited number of publications investigating such drugs. Examples include dutasteride, finasteride and systemic type I 5α-R inhibitors (Leyden et al., 2004; Hirshburg, 2016). In all cited cases, 5α-R inhibitors were administered orally, which was associated with a risk of side effects. For example, dutasteride inhibits the production of dihydrotestosterone throughout the body, disrupting important functions of this hormone such as regulation of blood flow and prostate volume. As a result, patients complain of decreased libido, headache, and gastrointestinal discomfort (Roehrborn et al., 2002). Topical use of targeted 5α-R inhibitors completely eliminates the risk of such systemic effects and allows to target the problem area without disturbing the hormonal balance in the whole organism.

FIGURE 1

Acne treatment strategy based on 5α-reductase I inhibition.

Despite the abundance of various procedures, cosmetic and medicinal products aimed at acne control, to date there is still no universal way to treat this pathology, so the search for new approaches and molecules with high activity still remains a very urgent problem (Yang et al., 2017).

Various medicinal plants and their phytochemicals have long been extremely popular for the acne management (Pareek et al., 2025). Some of them, such as tea tree oil (Melaleuca alternifolia), grape seed extract (Vitis vinifera) and witch hazel (Hamamelis virginiana) have complex moisturizing and anti-acne actions (Chularojanamontri et al., 2014), but have no confirmed targeting activity on 5α-R. Medicinal plants from traditional oriental and Asian medicine, in particular star anise and Prunus mume fruits, are attracting special attention.

Shikimic acid is an organic mono-basic trihydroxymonocarboxylic acid derived from the fruit and seeds of the star anise (Illicium verum). This substance has only recently begun to be used in cosmetics and so far there are very few studies on its dermatological application. It has been shown that shikimic acid may have a deodorizing effect by inhibiting lipase and blocking the production of fatty acids (Garbossa et al., 2014). It also has exfoliating effects (Chen et al., 2016), helps to reduce skin dryness and sensitivity (Kim et al., 2001) and possess antibacterial properties (Bai et al., 2015).

Prunus Mume (Japanese apricot) has been used since antiquity in oriental medicine. According to phytochemical studies, P. mume fruit extract is rich in phenols, flavonoids and organic acids (Gong et al., 2021). It has been shown that P. mume fruit extract has antibacterial, anti-inflammatory and antioxidant activities (Seneviratne et al., 2011; Morimoto-Yamashita et al., 2015; Lee et al., 2017).

Therefore, the aim of this study was to investigate the targeting bioactivity of shikimic acid combined with P. mume fruit extract on type I 5α-R in skin sebocytes and to evaluate the clinical efficacy of these compounds in hydrocolloid patches to assess their applicability in the treatment of acne. An algorithm of in silico, in vitro, and in vivo methods was used for the multifaceted evaluation of the hypothesis, as described next.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Molecular docking studies

The three-dimensional structure of the 5α-R I type protein (PDB ID: 3LLQ) was obtained from the Protein Data Bank for structural fitting and subsequent docking analyses (Linstrom, 1997; Linstrom and Mallard, 2001). Protein structure was acquired in the standard .pdb format. The preparation process involved the removal of water molecules, excision of superfluous chains, and the addition of polar hydrogens and charges. The refined protein structures were then saved in .pdb for further in silico studies. Molecular docking experiments were conducted using a personal computer equipped with an Intel Core i7-12700U CPU (2.3 GHz) and 16 GB of RAM, running Windows 11 (64-bit OS). To validate the docking procedure, the native protein ligand was initially docked to ensure methodological consistency.

Subsequent molecular docking of 5α-R was performed with four ligands: salicylic acid, bakuchiol, quercetin as a main compound of P. mume extract and shikimic acid. A comprehensive computational methodology was implemented in this investigation for the execution of molecular docking analyses. A multi-tiered protocol was employed, wherein the DiffDock (Corso et al., 2022) model was selected due to its optimal suitability for blind docking methodologies, in which no a priori knowledge regarding binding site localization isx presumed. This diffusion-based algorithmic approach was utilized for the prediction and characterization of ligand positioning within protein binding cavities. In docking process, Diffdock algorithm created 10 conformation and calculate Diffdock-confidence score for each of them. Subsequently, quantitative assessment of protein-ligand binding affinities was performed utilizing GNINA (McNutt et al., 2021) with grid, a scoring function operating on deep learning principles and calculated specifically for the top-rank (higger Diffdock-confidence score) conformation derived from DiffDock.

Concurrently, systematic analysis of protein structure surface interactions was conducted through the application of MASIF (Molecular Surface Interaction Fingerprinting) (Gainza et al., 2020).

2.2 Performing molecular dynamics and MM/PBSA analysis

The highest-scoring docking poses of shikimic acid were further refined through molecular dynamics (MD) simulations using GROMACS v.2023.1 (Abraham et al., 2015) with MPI support. Each protein–ligand complex was set up for MD simulation employing the CHARMM36 force field (Huang and MacKerell, 2013) for the protein and CGenFF parameters (Vanommeslaeghe et al., 2010) for the ligand. The systems were embedded in a cubic solvent box filled with TIP3P water molecules (Mark and Nilsson, 2001), ensuring a minimum padding of 1.0 nm between the protein surface and the box edges. System neutrality was achieved by introducing counterions.

Initial geometry optimization was carried out via the steepest descent algorithm, followed by equilibration in the NVT ensemble (100 ps) and then in the NPT ensemble (100 ps). A production MD trajectory was generated for 20 ns under NPT conditions at 298.15 K and 1 bar, with temperature and pressure regulated by the Nosé–Hoover thermostat (Evans and Holian, 1985) and the Parrinello–Rahman barostat (Ke et al., 2022), respectively. Coordinates were recorded every 10 ps for downstream analyses.

Binding free energies were estimated using the MM/PBSA approach (Genheden and Ryde, 2015) as implemented in gmx_MMPBSA v.1.6.4 (Valdés-Tresanco et al., 2021). The calculation was based on the final 10 ns of each production trajectory, sampling frames at 100-ps intervals. The Poisson–Boltzmann (PB) implicit solvation model was used with a grid spacing of 0.5 Å and an ionic strength of 0.1 M (Stein et al., 2019).

2.3 Raw materials

Skikimic acid (CAS 138-59-0) was obtained from Shaanxi Huike Botanical Development Co., Ltd. (Xian city, China). Prunus mume fruit extract standardized for quercetin (1–5 wt%) was prepared by Danjoungbio Co., Ltd. (Gangwon-do, Republic of Korea). Azelaic acid (CAS 123-99-9) was obtained from Sunfine Global Co., Ltd. (Chungcheongbuk-do, Republic of Korea). Salicylic acid (CAS 69-72-7) stabilized by methyl cyclodextrin was purchased from Shangdong Binzhou Zhiyuan Biotechnology Co., Ltd. (Shangdong, China).

2.4 Sebocytes cell culture and growth conditions

Human sebocytes (Celprogen, United States) purchased from were grown in 75 cm2 flasks (Corning, United States), cultivated and expanded in an incubator at 37 °C in the presence of 5% CO2, using a culture medium with 0.03% Tween 20 (Sigma). When confluence was reached, the cells were seeded in 96-well plates (Corning, United States) to determine the non-cytotoxic concentrations of the evaluated substance.

2.5 In vitro evaluation of substances on sebocytes viability

Cell viability of dermal sebocytes was determined colorimetrically using MTT (3-[4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl]-2,5 diphenyl tetrazolium bromide) dye (Sigma Chemical, St. Louis, Mo., United States). For the assay the evaluated substance was prepared in culture medium with 0.03% Tween 20 (Sigma Chemical, St. Louis, Mo., United States) and added to the 96 well plate at a serial dilution in the range of 100.00–0.003 mg/mL using the dilution factor of 3.1610. Sebocyte cells were used in the amount of 105 cells per well in a 96-well plate. Pre-culture was carried out for 48 h before the test. Basal control was represented as cells without treatment. The number of surviving cells was fixed with MTT at 5 mg/mL (30 µL/well), incubated for another 4 h and absorbance measurements were performed at 570 nm using Multiskan GO monochromator (Thermo Scientific, Finland). Cell viability was expressed as a percentage relative to the control. The number of biological repetitions was 6. Statistical data processing was performed to calculate the mean, standard deviation, and trend for each biological repetition. The normality of the data was controlled using the Shapiro-Wilk test. Comparisons were made using a linear mixed-effects model in case of normality; in case of nonparametric statistics, the Wilcoxon test was used.

2.6 Type I 5-alpha reductase activity assay in skin sebocytes

The study was performed on skin sebocytes after culturing under standard conditions, using three maximum nontoxic concentrations from previous testing. Cells were additionally stimulated with 10 nM testosterone, simulating the inflammatory hormonal stress conditions of acne, and cultured for 72 h in an atmosphere with 5% CO2 at 37 °C. For each experimental condition (basal, testosterone-induced stress, and active substances concentrations), three wells were plated, each containing ∼90,000 sebocytes. The cell supernatant was then obtained, purified, and the 5α-R type I amount was assessed by ELISA enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay using Human 3-oxo-5-alpha-steroid-4-dehydrogenase ELISA Kit (5α-reductase type I, ABclonal, United States, catalog code RK12279). Quantification was performed spectrophotometrically at a wavelength of 450 nm using a Multiskan GO monochromator (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Finland). After the assay, protein levels (pg/mL) were obtained by applying the measured optical density (OD) to the linear regression equation derived from the standard curve provided by the kit. Thus, data normalization relies directly on the standard curve calibration.

Salicylic acid and azelaic acid, known for the treatment of acne and related conditions (Lu et al., 2019; King et al., 2023), were used as positive comparison controls. This study included three technical replicates per condition. No additional normalization (e.g., total protein quantification) was applied.

To evaluate the data obtained, the ANOVA test was used, which also allowed measuring the variation in results, comparing data between groups. The Bonferroni post-test was then applied, which reinforced and made the result presented in the ANOVA test even more precise. A significance level of 5% was used in both assessments.

2.7 Patches formulations for the clinical research and stability test

A novel phytochemical combination of shikimic acid and P. mume extract was implemented into the thin hydrocolloid cosmetic patches, as shown in Table 1.

TABLE 1

| No | Compound | Concentration, wt%. |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Water | Up to 100.00 |

| 2 | Acrylates copolymer (water solution in a mass ratio of 1:1) | 88.10 |

| 3 | Sodium acrylate/Sodium acryloyldimethyl taurate copolymer | 1.20 |

| 4 | 1,2-Hexanediol | 5.60 |

| 5 | Polyisobutene | 0.80 |

| 6 | Solubilizers (caprylyl/capric glucoside, sorbitan oleate) | 0.20 |

| 7 | Gluconolactone | 1.00 |

| 8 | Shikimic acid | 0.50 |

| 9 | Prunus mume fruit extract | 0.50 |

| 10 | Lespedeza cuneata extract | 0.25 |

| 11 | Lactobacillus ferment extract | 0.25 |

| 12 | Additives (glycerin, butylene glycol, 1,2-hexanediol) | Up to 3.00 |

Composition of acne patches with combination of shikimic acid and Prunus mume extract.

The pH of the final patch formulation (semi-finished product) was measured to be between 5.5 and 7.5 at 25 °C. For stability, the patches were stored in dry, well-ventilated areas at temperatures ranging from +5 °C to +25 °C and at a relative air humidity not exceeding 75%, protected from direct sunlight and heat sources.

2.8 Clinical research of cosmetic patches for acne treatment

This clinical research was performed with thin polymer acne-patches soaked with composition of shikimic acid and P. mume extract to evaluate its compatibility with human skin (irritant potential) under normal conditions of use and reasonably foreseeable misuse conditions. Thin patches consisting of Table 1 ingredients were used as the base for the ingredients introduction. As a positive control, thin cosmetic patches containing 0.5 wt% encapsulated salicylic acid as the main active for acne treatment were selected.

Study was carried out in compliance with the most recent recommendations of the Helsinki Declaration (64th WMA General Assembly, Fortaleza, Brazil, October 2013) and has followed the “Guidelines for the Assessment of Skin Tolerance of Potentially Irritant Cosmetic Ingredients,” (Walker et al., 1997). After a favorable opinion from the ethical committee of CosmoProdTest (protocol code DR079860, 28 March 2024), the participants provided written informed consent to voluntarily participate in this clinical study.

A prospective open-label, non-randomized, single-center, split-body within-subject controlled study was conducted to determine the effect of thin acne patches containing a composition of shikimic acid and P. mume extract. Fifteen male and female volunteers, aged 18–28 years, mean age 19.8 years, with oily or combined skin type were involved. The study included volunteers with mild to moderate acne. Inclusion criteria were: volunteer’s agreement to carefully and diligently follow the instructions provided by the investigator, age 18–28 years, skin type: combination, oily, or prone to oiliness; clinical examination data: oily shine on the facial skin, enlarged pores, open and closed comedones, single papules, pustules, post-inflammatory spots; papulopustular form of acne of mild severity (presence on the face of closed and open comedones, an insignificant number of papules and pustules). Exclusion criteria were: allergic history, increased sensitivity to the components of the investigational products, dermatological diseases in the acute phase, problematic pigmentation; oncological diseases, blood diseases, autoimmune diseases; endocrinopathies affecting the condition of the skin; severe injuries and surgical interventions during the last 6 months; any cosmetic procedures in the observation area in the last 3 months preceding the study and during the study period (including the use of cosmetic products with phytoestrogens, AHA acids, retinoids within the last 6 months, laser or mechanical resurfacing, medium or deep chemical peels within the last 6 months, implantation of gels, threads, botulinum toxin injections, mesotherapy, biorevitalization, plasmolifting, ozone therapy within the last 2 months, etc.); any plastic surgery in the observed area in the last 12 months; systemic or topical use of medicinal products which, in the investigator’s opinion, may influence the outcome of the study during the study period and in the 6 months preceding the study; visiting a solarium; various diets; alcohol, smoking, narcotic drugs abuse. Volunteers met the inclusion criteria and had no exclusion criteria.

The study was designed as a split-body within-subject, using the investigational patch and the patch with salycilic acid (0.5 wt.%) in the same subject in parallel, on two close body areas with similar acne spots. The main objective was to confirm non-inferiority of the investigational product to the patch used as a standard for acne treatment. Subjects used the product under dermatologist control according to their individual personal hygiene routine and in accordance with the following guidelines: determine the size of the skin inflammation, clean the skin in the usual way, stick the patch on the inflamed area, evaluate the inflamed area after 6–8 h and remove the patch in case of positive results. In case the inflammation signs were still preasent observation was continued up to 48 h or until resolution.

Before the study, the sensitizing and irritating properties were assessed by a single application of the investigated product with the composition on the skin under dermatologist supervision. Additionally, functional parameters of the skin - sebummetry, comedogenicity, erythema and pigmentation indices when using the products were evaluated. Before the study, all subjects underwent a preliminary examination, including physical examination, analysis of concomitant diseases, thorough collection of dermatologic, allergologic and pharmacologic anamnesis. All studies were conducted in the same conditions of humidity and air temperature 22 °C ± 2 °C and relative humidity 40%–60%. The effects were evaluated using certified medical equipment: Cutometer® 580 MPA equipped with a built-in sensor Sebumeter® SM 815 (sebumetry); mexameter with a special lamp with 2 wavelengths (mexametry); Tewameter® TM 300 (tevametry); UV lamp equipped with a magnifying glass manufactured by “IONTO-COMED GmbH” (Germany).

The clinical study included several visits to a dermatologist. Visit 0 served to obtain informed consent and visual assessment of skin condition using instrumental diagnostic methods. After that, thin patches were applied to selected areas with early inflammation. Visit 1 occurred 8 h after the start of the study and application of the patch to the inflamed area. The dermatologist removed the patches, after which the volunteer rested for 10 min to rule out false reactions to the patch. Next, the dermatologist performed clinical examination, local status assessment, and visual inspection. If the area of early inflammation did not resolve in 8 h, the dermatologist measured skin parameters and applied new thin patches. Visit 2 occurred 24 h after the first application of the study products. The dermatologist removed the patches, after which the volunteer rested for 10 min to rule out false reactions to the patch. Next, the dermatologist performed clinical examination, assessment of localized status, and visual inspection. If the area of early inflammation did not resolve in 24 h, the dermatologist measured skin parameters and applied new thin patches. Visit 3 occurred 48 h after the first application of the study products. The dermatologist removed the patches, after which the volunteer rested for 10 min to rule out false reactions to the patch. Next, the dermatologist performed clinical examination, assessment of localized status, and visual inspection. If the early inflammation area did not resolve in 48 h, the dermatologist measured the skin parameters and made a note in the individual patient’s medical record.

To assess efficacy measures a significance level of α = 0.05 was adopted for all statistical analyses. The primary hypothesis tested was the equality of means. The assumption of normality for the sampling distribution of the mean was inferred from the normality of the underlying data, which was assessed using the Shapiro-Wilk test. For within-group comparisons (baseline and post-treatment measurements), a paired Student’s t-test was employed. For comparisons between different patches groups, Welch’s t-test was used. To control the false discovery rate (FDR) arising from multiple comparisons, the p-values were adjusted using the Benjamin-Hochberg procedure. The obtained results were processed using the Statistica package (StatSoft, United States, Ver. 8.0).

3 Results and discussion

3.1 Molecular docking studies

Four ligands were selected to evaluate the interaction with 5α-R in silico: salicylic acid, bakuchiol, quercetin as a main phytochemical of P. mume extract and shikimic acid. Salicylic acid is one of the best known acne management components (Lu et al., 2019). Bacuchiol is a plant-derived component with anti-inflammatory and antibacterial effects, because of which it is widely used in dermatology and considered as a promising anti-acne agent (Puyana et al., 2022; Mascarenhas-Melo et al., 2024). Quercetin, found in Prunus mume fruit (Jang et al., 2018), has shown efficacy in the treatment of acne of bacterial nature due to its complex anti-inflammatory and antioxidant properties (Lim et al., 2021; Bo and Li, 2025). Shikimic acid has only recently entered the world of cosmetics and there are very few researches of testing this compound’s effects in humans. However, it has been reported to have potential for anti-acne applications due to its antibacterial and moisturizing properties (Batory and Rotsztejn, 2022).

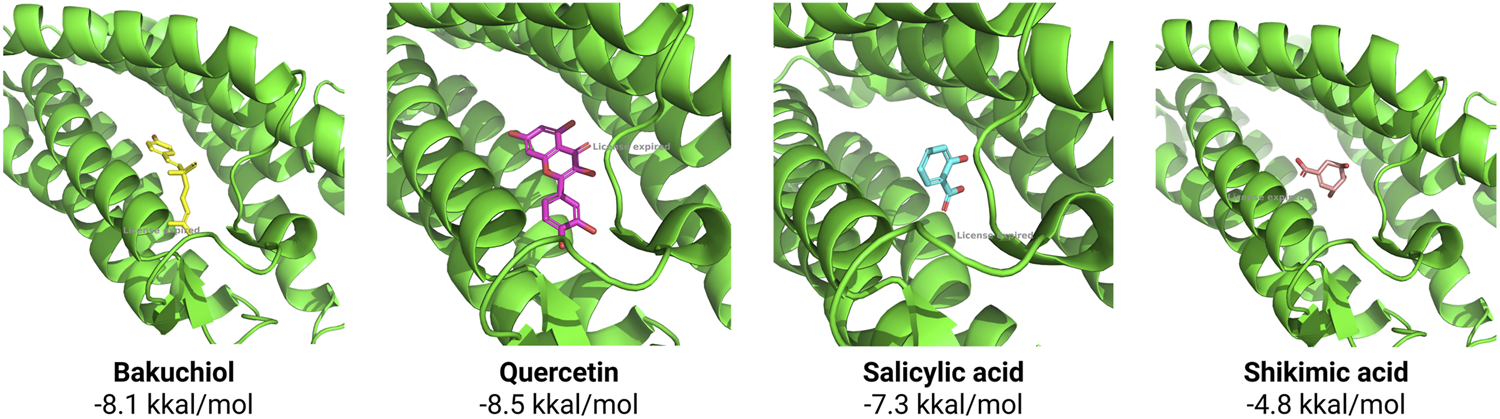

According to the results of molecular docking, all of the studied substances–bakuchiol, quercetin, salicylic acid, and shikimic acid–were found interact with the active center of 5α-R (Figure 2). Across 10 docking simulations, the best-scoring poses consistently reproduced the experimental ligand conformation with an average RMSD of 2.06 Å (±0.44 Å).

FIGURE 2

Molecular docking of substances with 5α-R active center and their affinity (kkal/mol).

The highest affinity to the 5α-R active center was shown by quercetin, but this compound is characterized by low stability due to its susceptibility to oxidative and light degradation and poor water solubility, which makes it limited for use in cosmetics (Osojnik Črnivec et al., 2024). Bakuchiol also has high affinity for the 5α-R active site, but its topical application is hampered by its low permeability across the epidermal barrier (Lu et al., 2025). Salicylic acid is one of the classical components for acne therapy, but it often causes dryness and irritation of the skin and therefore needs to be supplemented with moisturizers (Chularojanamontri et al., 2014).

Despite exhibiting relatively low binding affinity, shikimic acid is positioned within the steroid-binding pocket of the 5α-R active site. Optimal spatial complementarity and electrostatic interactions with critical catalytic residues are maintained in this orientation. Consequently, significant inhibitory efficacy is achieved through precise molecular recognition and stabilization within the enzymatic cleft, despite suboptimal affinity metrics. Shikimic acid is still not widely used in cosmetic products, but it has good stability (Chen et al., 2014) and moisturizing properties (Batory and Rotsztejn, 2022), so this substance was chosen for further work.

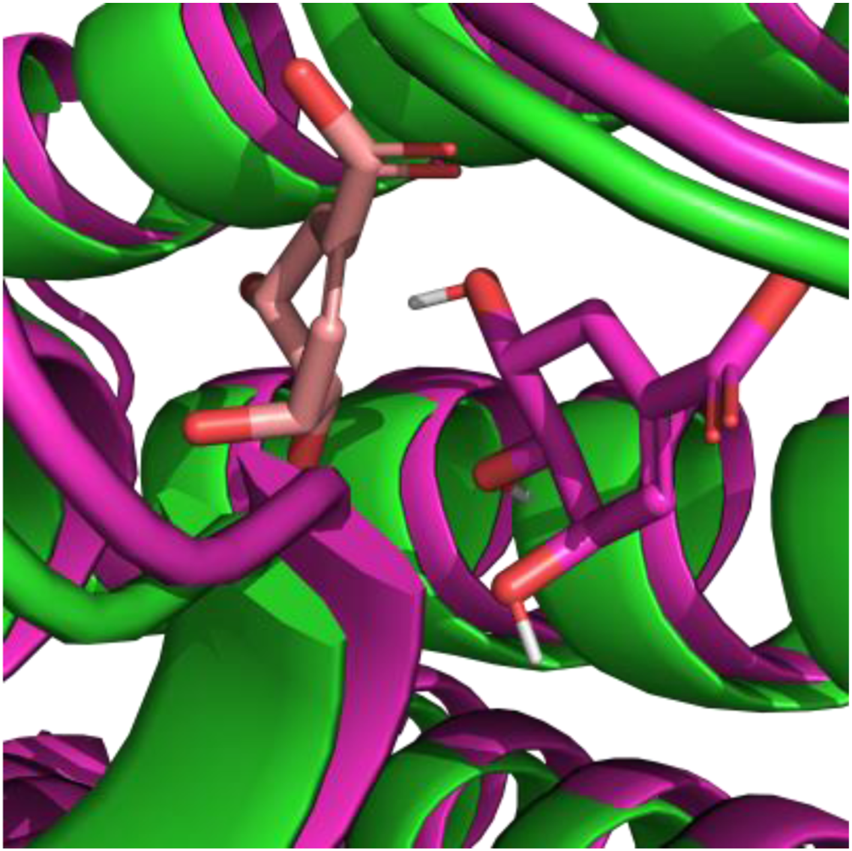

Molecular docking provides only an initial estimate of binding affinity and is inherently limited by the inaccuracies of scoring functions in reliably predicting true binding free energies (10.5772/intechopen.85991). For futher validation docking position of shikimic acid (Diffdock-confidence score equal, we used MM/PBSA analysis based on the Poisson–Boltzmann method yielded binding free energies of −6.53 ± 1.02 kcal/mol for 5-alpha-reductase. Analysis of the molecular dynamics (MD) trajectories indicated that paeoniflorin remained stably positioned within the corresponding docking binding site throughout the simulation (Figure 3).

FIGURE 3

Comparinsing positions of shikimic acid after MD: peach color represent docking position, green represent crystal structures of 5α-R, magenta represent position of shikimic acid and 5α-R stable positions after MD.

3.2 In vitro evaluation of sebocytes viability

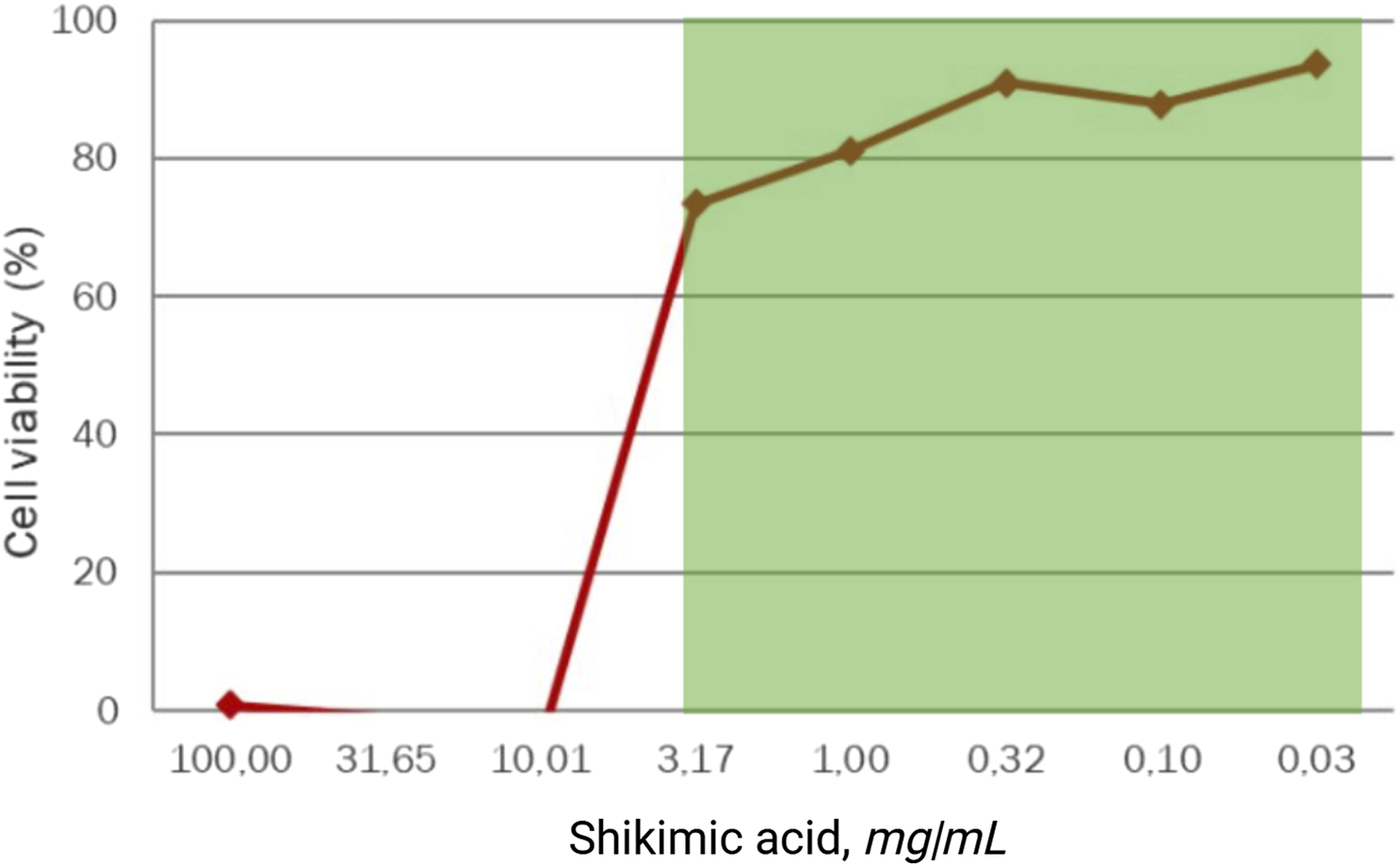

The evaluation of cytotoxicity revealed that shikimic acid had a favorable toxicological profile on the skin sebocyte model in the studied concentration interval from 0.001% to 1.0% wt. Cell viability was maintained throughout the entire concentration range of shikimic acid and above the threshold value of 70% (EC70), indicating a gentle effect on skin cells involved in the acne pathogenesis (Table 2; Figure 4). At the same time, the cytotoxicity of shikimic acid is about 15%–20% less than that of salicylic acid, often used for topical acne management.

TABLE 2

| Substance | Cell viability, % | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.001% | 0.006% | 0.02% | 0.06% | 0.20% | 0.6% | 2.0% | |

| Basal control | 100.0 ± 2.0 | 100.0 ± 2.0 | 100.0 ± 2.0 | 100.0 ± 2.0 | 100.0 ± 2.0 | 100.0 ± 2.0 | 100.0 ± 2.0 |

| Shikimic acid | 105.0 ± 3.0 | 105.0 ± 3.0 | 105.0 ± 3.0 | 105.0 ± 3.0 | 103.0 ± 3.0 | 104.0 ± 3.0 | 100.0 ± 3.0 |

| Positive control (salicylic acid) | 90.0 ± 2.0 | 90.0 ± 2.0 | 90.0 ± 2.0 | 85.0 ± 2.0 | 85.0 ± 2.0 | 83.0 ± 2.0 | 81.0 ± 2.0 |

Skin sebocytes viability in presence of substances.

FIGURE 4

Viability of dermal sebocytes treated for 48 h with shikimic acid (n = 3).

Next, the effect of P. mume extract and shikimic acid combination on dermal sebocyte viability was tested. It was found that cell survival was maintained at a high level (85%–102% of live cells), throughout the studied range of 0.001–1.0 wt.% compared to the basal control. Throughout the concentration range from 0.001% to 0.2%, the survival of cells treated with the combination of shikimic acid and P. mume extract is only slightly lower compared to those treated with pure shikimic acid (average difference between 3% and 5%). However, starting at a concentration of 0.6%, the survival rate of cells treated with the combination drops sharply to 90% and further to 85%, which is about 15% lower than the survival rate under pure shikimic acid. This indicates that at concentrations up to 0.6% the combination gently affects the metabolic activity of cells and can be used for topical acne treatment (Table 3).

TABLE 3

| Substance | Cell viability | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.001% | 0.006% | 0.02% | 0.06% | 0.20% | 0.6% | 2.0% | |

| Basal control | 100.0 ± 2.0 | 100.0 ± 2.0 | 100.0 ± 2.0 | 100.0 ± 2.0 | 100.0 ± 2.0 | 100.0 ± 2.0 | 100.0 ± 2.0 |

| Shikimic acid | 105.0 ± 3.0 | 105.0 ± 3.0 | 105.0 ± 3.0 | 105.0 ± 3.0 | 103.0 ± 3.0 | 104.0 ± 3.0 | 100.0 ± 3.0 |

| Prunus mume fruit extract + shikimic acid mass ratio 1:1 | 100.0 ± 3.0 | 100.0 ± 2.0 | 102.0 ± 3.0 | 101.0 ± 3.0 | 99.0 ± 3.0 | 90.0 ± 3.0 | 85.0 ± 3.0 |

Cytotoxicity assay of shikimic acid and Prunus Mume extract in mass ratio 1:1 on skin sebocytes

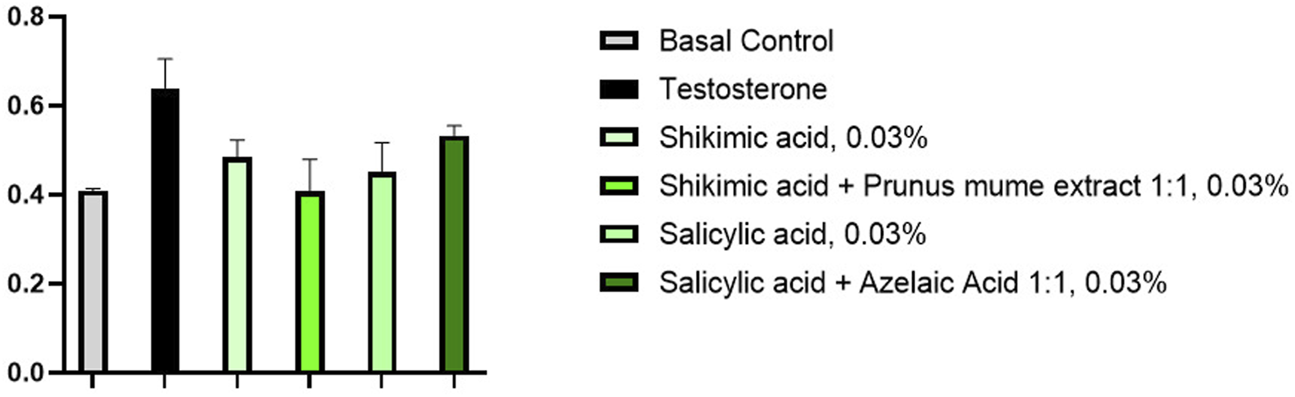

3.3 Determination of type I 5-alpha reductase in skin sebocytes

After shikimic acid exposure, the amount of 5α-R in skin sebocytes in vitro decreased by a value ranging from 67.5% to 101% depending on the acid concentration against the background of hormonal stress and returned to the initial physiological level (Table 4). This means that at a concentration of 0.3% shikimic acid completely eliminates the hormonal stress caused by excessive testosterone level (p < 0.001).

TABLE 4

| Substance, wt.% | Amount of type I 5α-R (mg/mL) | Decrease in type I 5α-R in relation to the difference between basal control and stressor, % | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Basal control | 0.409 ± 0.005 | — | |

| Stressor: Testosterone 10 nM | 0.640 ± 0.065 | +56.5% | |

| Shikimic acid | 0.03% | 0.484 ± 0.039 | −67.5%* |

| 0.1% | 0.445 ± 0.027 | −84.7%** | |

| 0.3% | 0.407 ± 0.021 | −101.1%*** | |

Evaluation of 5α-R amount in skin sebocytes.

Significance levels: *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001.

It was also checked whether the 5α-R-modulating properties of shikimic acid in the composition with P. mume fruit extract were not changed. According to the results of 5α-R quantification in skin sebocytes after the composition components were added to the culture medium, it turned out that in the combined presence of P. mume fruit extract not only does not impair the properties of shikimic acid, but shows an enhanced effect. This effect is well expressed even at the minimum concentration of 0.03% of the active ingredient studied by us (Figure 5).

FIGURE 5

Determination of 5α-R amount in skin sebocytes in the presence of substances (n = 3).

The combination of P. mume extract and shikimic acid in a mass ratio of 1:1 reduced the amount of 5α-R by more than 100% (p < 0.001) at a concentration of 0.3% under testosterone-induced hormonal inflammatory stress (10 nM) compared to basal levels after 48 h of skin dermal cell culture (Table 5). Thus, the combination of shikimic acid with P. mume extract completely eliminates the effects of hormonal stress by reducing 5α-R back to basal levels. At the same time, this combination is almost 20% more effective than a similar concentration of shikimic acid alone (p < 0.001) and almost 30% more effective than similar concentrations of azelaic and salicylic acids (p < 0.01).

TABLE 5

| Substance, wt.% | Amount of type I 5α-R (mg/mL) | Decrease in type I 5α-R relative to the difference between basal control and stressor, % | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Basal control | 0.409 ± 0.005 | — | |

| Stressor: Testosterone 10 nM | 0.640 ± 0.065 | +56.5% | |

| Shikimic acid | 0.03% | 0.484 ± 0.039 | −67.5%* |

| 0.1% | 0.445 ± 0.027 | −84.7%** | |

| 0.3% | 0.407 ± 0.021 | −101.1%*** | |

| Shikimic acid and Prunus mume extract in mass ratio 1:1 | 0.03% | 0.408 ± 0.072 | −100.5%*** |

| 0.1% | 0.387 ± 0.011 | −109.9%*** | |

| 0.3% | 0.365 ± 0.007 | −119.3%*** | |

| 1.0% | 0.340 ± 0.003 | −129.7%*** | |

| Salicylic acid | 0.03% | 0.451 ± 0.066 | −82.2%** |

| 0.1% | 0.446 ± 0.014 | −84.1%** | |

| 0.3% | 0.440 ± 0.043 | −86.5%** | |

| Azelaic acid + salicylic acid in mass ratio 1:1 | 0.03% | 0.533 ± 0.022 | −66.9%* |

| 0.1% | 0.486 ± 0.045 | −73.8%* | |

| 0.3% | 0.470 ± 0.003 | −82.1%** | |

Evaluation of 5α-R amounts in skin sebocytes in presence of shikimic acid and Prunus mume extract.

Significance levels: *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001.

Also the combination with P. mume fruit extract was found to exhibit significant bioactivity, effectively affecting 5α-R in sebocytes at concentrations ranging from 0.03% to 1.0%. Shikimic acid alone has a more moderate impact on reducing the expression of 5α-R in skin sebocyte cells, and for a comparable effect, it needs to be used 10 times more than the tested combination. The action of 0.3% shikimic acid is equivalent to that of 0.03% of the combination with P. mume fruit extract (p < 0.001). Thus, P. mume fruit extract has an enhansing effect, allowing to reduce the concentration of shikimic acid by 10 times while maintaining the high biological activity of the combination. At the same time, there is no information in the literature about the fact that P. mume fruit extract itself has inhibitory activity against 5α-R. It is assumed that P. mume extract may have a synergistic effect, but more detailed study of the component synergism and its effect on various biological targets is required further.

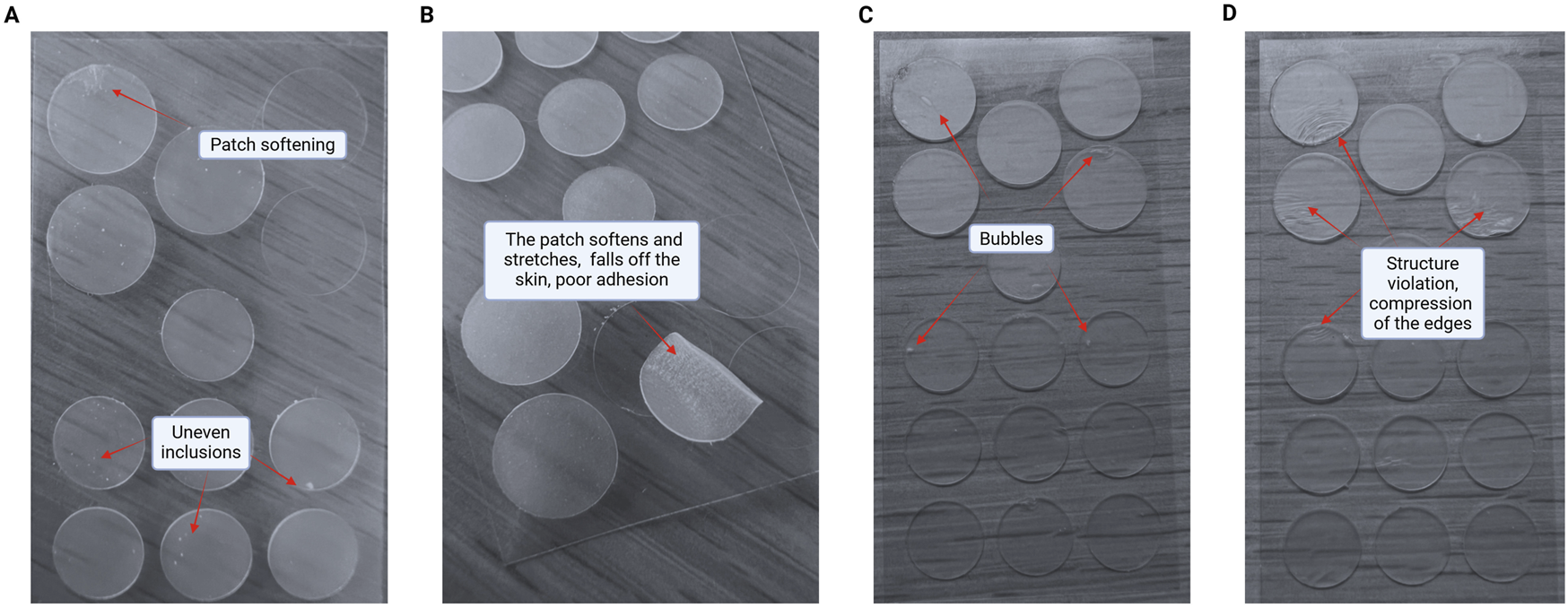

3.4 Evaluation of shikimic acid technological applicability as a component of cosmetic patches

The technological applicability of shikimic acid in cosmetic patches consisting of the components described in Table 1 was evaluated. Production of thin patches from hydrocolloid mass is a complex technological process that requiring a special method of preparation and composition introduction. It is necessary for the outer hydrogel layer to be impermeable and provide a protective film, while the inner layer has colloidal properties to bind exudate at the inflammation site. The stability and efficacy of such a construct depends on the preparation temperature and the interaction of the polymers in its composition, so technologically cosmetic patches are more complicated comparing to other topical acne treatments (Kuo et al., 2021). In this study, the technological complexity was further increased by the fact that shikimic acid is a water-soluble substance, and the thin patches have less than 5% free water to dissolve it.

When patches samples were made, it was found that shikimic acid at a concentration of 0.5 wt.% significantly impaired their stability and appearance. These changes were manifested by the precipitation of shikimic acid crystals over the entire patches surface, presumably due to its low solubility in anhydrous media. Thus, the patch samples had an uneven surface, crystalline inclusions, softening, decreased adhesion to the skin surface, color change during the stability test at 42 °C ± 2 °C, and impaired plasticity of the colloidal mass (Figure 6). The agglomerates formation was visible to the naked eye and confirmed by optical microscopy. Besides aesthetic imperfection, such changes critically affect the hydrocolloid patch properties. Patches with such a structure will unevenly release active ingredients into the skin and provide poor adhesion to the skin (checked by gluing the patch to the back of the previously cleaned hand (at the base of the thumb), the patch should instantly stick without bubbles or creases, fit tightly to the skin, not shift or slide across the surface), preventing delivery of the substance deep into the inflamed pore in acne. Shikimic acid crystals may also irritate the skin due to their moderate acidic properties. This means that despite their potential efficacy, in practice such patches are completely unsuitable for use on human skin.

FIGURE 6

Negative changes in patches structure and properties upon addition of shikimic acid. (A) Patch softening and uneven inclusions. (B) The patch softens and stretches, falls off the skin and has poor adhesion. (C) Bubbles formation. (D) Patches structure violation with compression of the edges.

The use of propylene glycol, glycerol and 1,2-hexanediol as solvents did not solve this technological problem. However, there are reports in the literature that plant extracts rich in polyphenols are able to unpredictably change the rheological properties of hydrocolloid films depending on the substances used: increase or decrease the viscosity of the solution, change thermostability and fluidity (Silva-Weiss, 2014). In particular, P. mume extract has similar properties due to its content of a large amount of flavonoids related in chemical structure to shikimic acid (Zhao et al., 2023). Thus, the P. mume extract addition potentially promoted the homogeneous dissolution of shikimic acid in the patches and ensured their stability over a long shelf life. To evaluate this hypothesis, a combination of shikimic acid and P. mume fruit extract in a mass ratio of 1:1 was prepared and its technological applicability as a stabilizing agent for thin acne patches was tested.

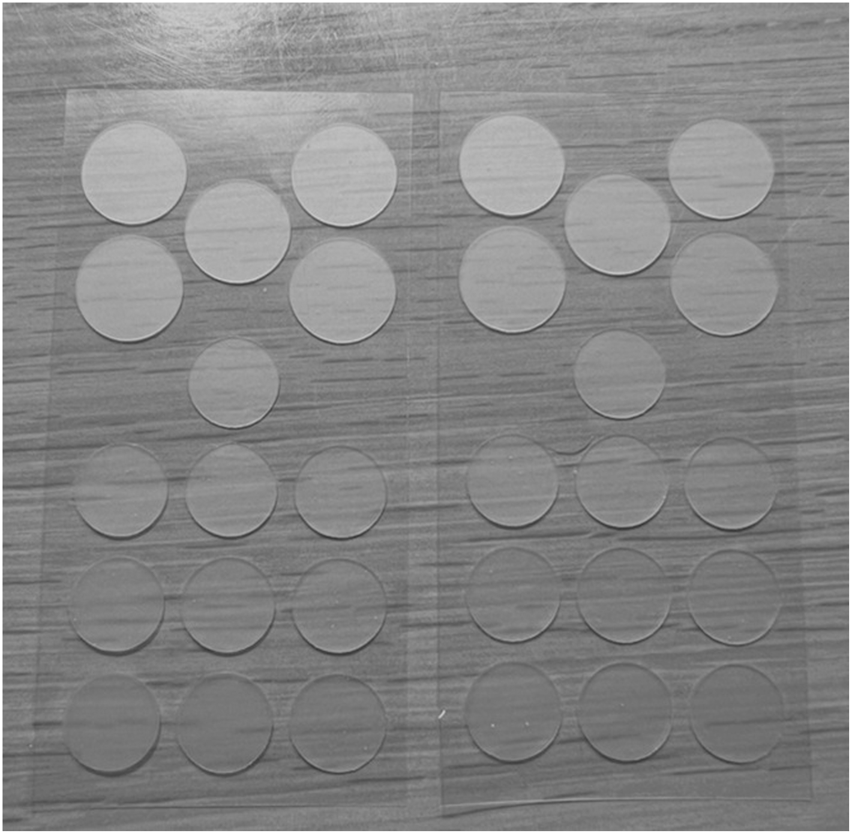

To preserve the patches consumptive and mechanical properties, it is necessary to make a premix of shikimic acid in the extract of P. mume fruits in a mass ratio of 1:1, with gradual addition of shikimic acid and a magnetic stirring at a speed of at least 300 rpm for at least 20 min. Under such conditions, shikimic acid starts to mutually dissolve in the P. mume fruit extract due to the high content of amphiphilic and lipophilic compounds, especially flavonoids, stabilizing shikimic acid due to related chemical structure. After preparation, the premix was introduced into the final hydrocolloid mass without heating under regular stirring until complete dissolution.

It turned out that the addition of P. mume fruit extract really increased the solubility of shikimic acid in the practically anhydrous hydrophobic hydrocolloid mass without crystal formation and without loss of elastic-viscosity-plastic properties of the patches. Patches produced by this technology had improved adhesion, stability and absence of inclusions, irregularities, air bubbles and crystals over the entire surface area (Figure 7).

FIGURE 7

Patches samples with composition of shikimic acid and Prunus mume extract without any defects.

3.5 Clinical research of patches with a composition of shikimic acid and Prunus mume extract

After stable patches with improved adhesion and 5α-R-modulating properties and safety on human sebocytes were obtained, the safety and efficacy of these patches for treatment of mild to moderate acne were clinically investigated. Lespedeza cuneata extract and Lactobacillus ferment extract were also included in the patch formula to eliminate post-acne signs and provide an antibacterial effect. Both named components have proven safety and are used in the cosmetic industry (Lee et al., 2018; Ingredient, 2022; Dou et al., 2023).

No serious adverse events were observed in the subject group during the patch approbation throughout the clinical study period, including home application, which indicates the good tolerability of these patches. At the final stage after 48 h, a clinical study showed positive dynamics of the skin condition in the absolute majority of the volunteers: elimination or resolution of early inflammed skin signs, removal of redness, elimination of subjective discomfort, even skin tone. In addition, there was no resumption of inflammatory processes in the patch application sites, pores were not clogged and the original skin condition was not aggravated.

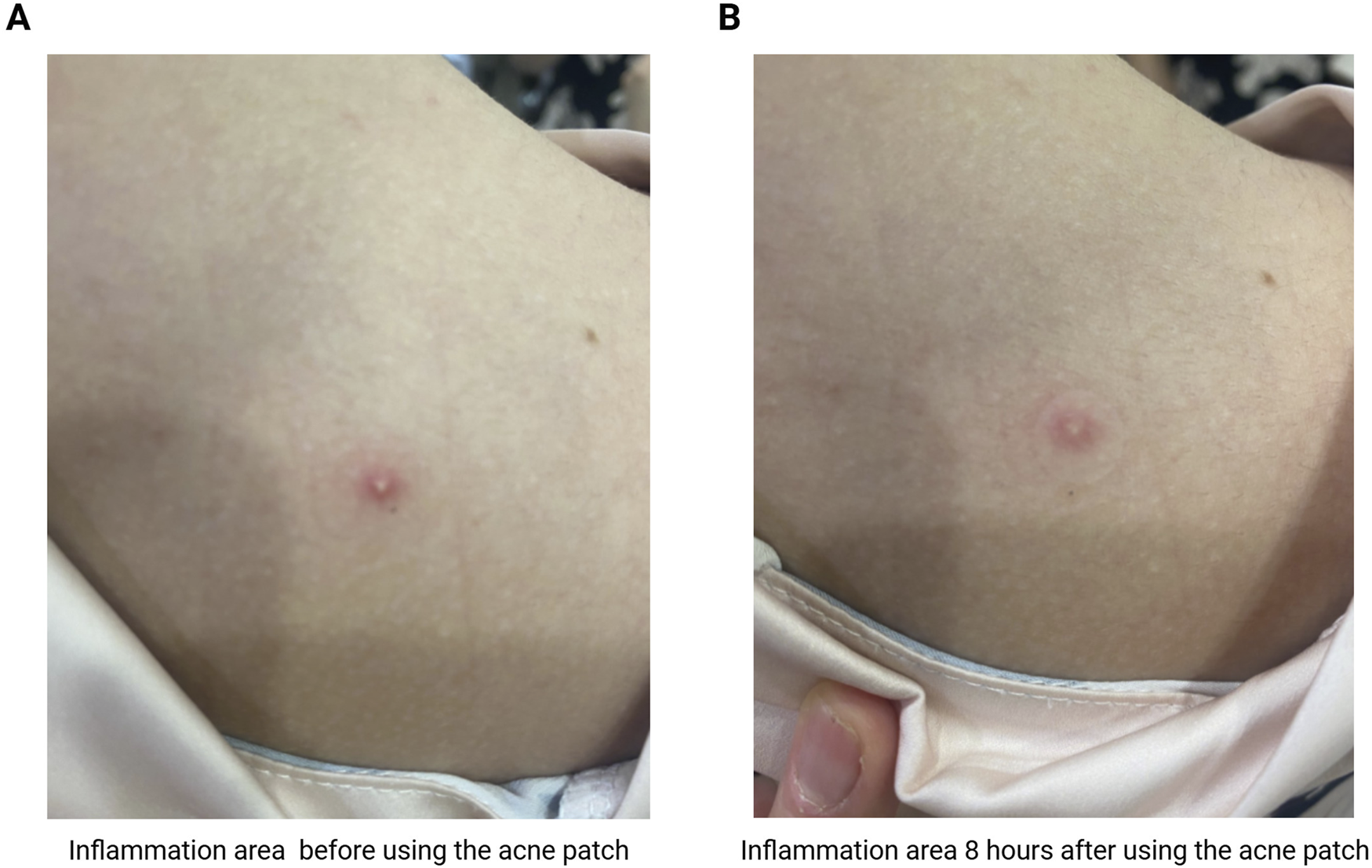

Acne signs elimination and supression at the early stage was achieved in 73% of the group of volunteers using study patches (11 out of 15 people) after 24 h. In 53% of volunteers who used thin patches with a composition based on shikimic acid and P. mume extract, the complete resolution of early inflammatory elements, regression of subjective sensations and visible improvement of skin condition after 8 h was noted. This demonstrates the rapid effect and hormonal stress normalization in mild acne (Figure 8). In the remaining 27% of volunteers inflammatory elements completely resolved after 48 h. The dermatologist noted the early resolution of inflammation with high efficacy and the patches’ safe impact on the skin. Early inflammatory elements disappeared in 24 h, while itching and redness were markedly reduced after one application within 8 h.

FIGURE 8

The effect of acne patches on healhy volunteer: (A) inflammation area before using the acne patch; (B) inflammation area 8 h after using the acne patch with shikimic acid and Prunus mume extract.

Using a positive control–patches with 0.5 wt.% salicylic acid–the acne signs elimination and suppression at the early stage was achieved in 73% of volunteers after 8–24 h, but with a predominant proportion after 24 h of constant patch contact with the skin. In 33% of volunteers using thin patches with salicylic acid, complete resolution of early inflammatory elements, regression of subjective sensations and visible improvement of skin condition was noted after 8 h. In the remaining 27% of volunteers, the inflammatory elements resolved after 48 h. Through in vitro study of 5α-R amount evaluation in human skin sebocytes, the combination of shikimic acid and P. mume was shown to be almost 30% more effective than salicylic acid. In this regard, the hypothesis of the research was that patches with salicylic acid may take longer time to produce a clinically significant effect than patches with shikimic acid and Prunus mume extract.

According to the results obtained by dynamic study of functional indices in the group of subjects using the biophysical research methods, an improvement in skin physiological parameters was found when using thin patches with a composition of shikimic acid and P. mume extract and with salicylic acid (Table 6). The combination of shikimic acid and P. mume fruit extract in a mass ratio of 1:1 significantly (p < 0.001) reduced the skin sebum content during 48 h of patches application, which allows normalizing the inflammation zone and reducing the influence of sebocytes on the acne pathogenesis. Patches with 0.5% salicylic acid also significantly (p < 0.01) reduced the skin sebum content during 48 h of patches application. A difference in efficacy was observed between the two types of acne patches, however, this difference did not reach statistical significance (p = 0.12).

TABLE 6

| Sample | Skin sebum content, µg/cm2 (n = 15) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Visit 0 before application | Visit 2 after 48 h of application | Relative change of visit 2 to visit 0, % | |

| Thin patches with a composition of 0.5% shikimic acid and 0.5% Prunus mume fruit extract, mass ratio 1:1 | 245.3 ± 12.6 | 205.6 ± 19.9 | −16.18*** |

| Thin patches with 0.5% salicylic acid (positive control) | 237.5 ± 12.1 | 211.6 ± 17.9 | −10.91** |

Skin sebum assessment on skin during clinical research.

Significance levels: ***p < 0.001, **p < 0.01.

The results obtained confirm the in vitro findings in terms of time frame. The comparatively rapid (from 8 h) inflammation area reduction is associated with the antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties of P. mume extract and shikimic acid. The subsequent skin improvement after 24 and 48 h is likely to mediated by 5αR modulation in sebocytes, which acts through epigenetic mechanisms and requires time to take effect.

It should be noted though that the study had certain limitations: the trial was planned as a pilot proof of concept study and the sample size (15 per group) was quite small (Julious, 2005). The results of this trial confirm safe test patch profile and good skin compatibility. Also the results show non-inferiority of the test therapy as compared to the control with a tendency to potentially higher efficacy. So the future research is stipulated with a bigger number of subjects and more thorough skin parameters assessment, potentially combining in vivo and in vitro assessments.

These results should be contextualized within existing acne therapies. In vitro studies included azelaic acid as a positive control, a well-established topical agent for acne. However, to achieve its therapeutic effect, azelaic acid typically requires high concentrations of 15%–20% in formulations, which are often associated with local side effects such as pain, itching, and dryness (Feng et al., 2024). In clinical study, salicylic acid was used as a positive control, which is often classified as quasi-drug—a regulatory category for products falling between cosmetics and pharmaceuticals. Other first-line topical treatments have inherent limitations. Retinoids, for instance, exert their effects by binding to nuclear retinoic acid receptors and modulating gene transcription (Huang et al., 2014). This genomic mechanism results in a cumulative effect, with significant clinical improvement often taking several weeks to manifest. Benzoyl peroxide, another acne treatment gold standart, possesses a potent antibacterial action against Cutibacterium acnes but, to the best of our knowledge, there is no substantial evidence documenting a direct inhibitory effect on I type 5α-reductase activity (Eid et al., 2023).

4 Conclusion

Shikimic acid is a highly active substance interacting with the active center of 5α-R and inhibiting the effects of hormonal stress induced by testosterone in skin. In vitro studies results have shown shikimic acid to be safe for human skin sebocytes and can reduce the amount of 5α-R in testosterone-exposed sebocytes to baseline physiologic levels in the skin. However, when introduced into cosmetic patches, shikimic acid negatively alters their structure, rendering the patches unusable.

This technological problem is solved by the addition of P. mume fruit extract, which stabilizes shikimic acid due to its related chemical structure and increases the shikimic acid solubility in a practically anhydrous hydrophobic hydrocolloid mass without crystal formation and loss of elastic-viscosity-plastic patch properties. In addition, P. mume extract has an enhanced effect with shikimic acid, increasing its 5α-R-modulating bioactivity and resulting in effective acne treatment. In clinical trial, the patches did not show any adverse effects and had a comparable effect on acne as salicylic acid analogs, eliminating skin imperfections within 24 h in the majority of the study group. The all observed results suggest that shikimic acid in combination with phenolic phytochemicals of P. mume extract has a promising potential for further research and development of cosmetic and pharmaceutical products to treat acne.

Statements

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by the ethics committee of Medical Scientific and Diagnosis Center Scientific and Practical Center on Expert Assessment of Food and Cosmetics Quality and Safety, СosmoProdTest Ltd., Moscow, Russia (research protocol No DR079860 dated 28.03.2024). The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. Written informed consent for participation in this study was provided by the participants’ legal guardians/next of kin. Written informed consent was obtained from the individual(s) for the publication of any potentially identifiable images or data included in this article.

Author contributions

EP: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal Analysis, Project administration, Software, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review and editing. EI: Data curation, Formal Analysis, Investigation, Software, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft. VF: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal Analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Software, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review and editing. EK: Methodology, Supervision, Validation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review and editing.

Funding

The author(s) declared that financial support was not received for this work and/or its publication.

Acknowledgments

The authors express their gratitude for the raw materials provided by SkyLab AG and expertise offered by the Faculty of Medicine and Department of Chemistry in Lomonosov Moscow State University.

Conflict of interest

Authors VF and EP were employed by SkyLab AG. SkyLab AG provided only non-financial support in supply of raw materials and substances (Prunus mume fruit extract, shikimic acid, salicylic acid, azelaic acid) and pilot scale-up of acne patches samples on high-performance technological equipment for further independent clinical research.

The remaining author(s) declared that this work was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declared that generative AI was not used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1

Abraham M. J. Murtola T. Schulz R. Páll S. Smith J. C. Hess B. et al (2015). GROMACS: high performance molecular simulations through multi-level parallelism from laptops to supercomputers. SoftwareX1-2, 19–25. 10.1016/j.softx.2015.06.001

2

Alkhawaja E. Hammadi S. Abdelmalek M. Mahasneh N. Alkhawaja B. Abdelmalek S. M. (2020). Antibiotic resistant Cutibacterium acnes among acne patients in Jordan: a cross sectional study. BMC Dermatol20, 17. 10.1186/s12895-020-00108-9

3

Bai J. Wu Y. Liu X. Zhong K. Huang Y. Gao H. (2015). Antibacterial activity of shikimic acid from pine needles of Cedrus deodara against Staphylococcus aureus through damage to cell membrane. Int. J. Mol. Sci.16, 27145–27155. 10.3390/ijms161126015

4

Batory M. Rotsztejn H. (2022). Shikimic acid in the light of current knowledge. J. Cosmet. Dermatol.21, 501–505. 10.1111/jocd.14136

5

Bhate K. Williams H. C. (2013). Epidemiology of acne vulgaris. Br. J. Dermatol.168, 474–485. 10.1111/bjd.12149

6

Bo Y. Li Y. (2025). Multi-target mechanisms and potential applications of quercetin in the treatment of acne vulgaris. Front. Pharmacol.16, 1523905. 10.3389/fphar.2025.1523905

7

Chen F. Hou K. Li S. Zu Y. Yang L. (2014). Extraction and chromatographic determination of shikimic acid in Chinese conifer needles with 1-benzyl-3-methylimidazolium bromide ionic liquid aqueous solutions. J. Anal. Methods Chem.2014, 256473. 10.1155/2014/256473

8

Chen Y.-H. Huang L. Wen Z.-H. Zhang C. Liang C.-H. Lai S.-T. et al (2016). Skin whitening capability of shikimic acid pathway compound. Eur. Rev. Med. Pharmacol. Sci.20, 1214–1220.

9

Chularojanamontri L. Tuchinda P. Kulthanan K. Pongparit K. (2014). Moisturizers for acne: what are their constituents?J. Clin. Aesthet. Dermatol.7, 36–44.

10

Corso G. Stärk H. Jing B. Barzilay R. Jaakkola T. (2022). DiffDock: diffusion steps, twists, and turns for molecular docking. ArXiv. 1, 1–25. 10.48550/arXiv.2210.01776

11

Del Rosso J. Q. Bunick C. G. Kircik L. Bhatia N. (2024). Topical clindamycin in the management of acne vulgaris: current perspectives and recent therapeutic advances. J. Drugs Dermatol.23, 438–445. 10.36849/JDD.8318

12

Dou J. Feng N. Guo F. Chen Z. Liang J. Wang T. et al (2023). Applications of probiotic constituents in cosmetics. Molecules28, 6765. 10.3390/molecules28196765

13

Dreno B. Kang S. Leyden J. York J. (2022). Update: mechanisms of topical retinoids in acne. J. Drugs Dermatol.21, 734–740. 10.36849/JDD.6890

14

Eid A. M. Naseef H. Jaradat N. Ghanim L. Moqadeh R. Yaseen M. (2023). Antibacterial and anti-acne activity of benzoyl peroxide nanoparticles incorporated in lemongrass oil nanoemulgel. Gels9, 186. 10.3390/gels9030186

15

Escamilla-Cruz M. Magaña M. Escandón-Perez S. Bello-Chavolla O. Y. (2023). Use of 5-alpha reductase inhibitors in dermatology: a narrative review. Dermatol. Ther. (Heidelb.)13, 1721–1731. 10.1007/s13555-023-00974-4

16

Evans D. J. Holian B. L. (1985). The nose–hoover thermostat. J. Chem. Phys.83, 4069–4074. 10.1063/1.449071

17

Feng X. Shang J. Gu Z. Gong J. Chen Y. Liu Y. (2024). Azelaic acid: mechanisms of action and clinical applications. Clin. Cosmet. Investig. Dermatol.17, 2359–2371. 10.2147/CCID.S485237

18

Gainza P. Sverrisson F. Monti F. Rodolà E. Boscaini D. Bronstein M. M. et al (2020). Deciphering interaction fingerprints from protein molecular surfaces using geometric deep learning. Nat. Methods17, 184–192. 10.1038/s41592-019-0666-6

19

Garbossa W. A. C. Mercurio D. G. Campos P. M. M. (2014). Ácido chiquímico para esfoliação cutânea. Surg. Cosmet. Dermatology6, 239–247.

20

GBD 2016 DALYs and HALE Collaborators (2017). Global, regional, and national disability-adjusted life-years (DALYs) for 333 diseases and injuries and healthy life expectancy (HALE) for 195 countries and territories, 1990-2016: a systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2016. Lancet390, 1260-1344. 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)32130-X

21

Genheden S. Ryde U. (2015). The MM/PBSA and MM/GBSA methods to estimate ligand-binding affinities. Expert Opin. Drug Discov.10, 449–461. 10.1517/17460441.2015.1032936

22

Gong X.-P. Tang Y. Song Y.-Y. Du G. Li J. (2021). Comprehensive review of phytochemical constituents, pharmacological properties, and clinical applications of Prunus mume. Front. Pharmacol.12, 679378. 10.3389/fphar.2021.679378

23

Hirshburg J. Kelsey P. A. Therrien C. A. Gavino A. C. Reichenberg J. S. (2016). Adverse effects and safety of 5-alpha reductase inhibitors (finasteride, dutasteride): a systematic review. J. Clin. Aesthetic Dermatology9, 56–62.

24

Holzmann R. Shakery K. (2014). Postadolescent acne in females. Skin. Pharmacol. Physiol.27 (Suppl. 1), 3–8. 10.1159/000354887

25

Huang J. MacKerell A. D. Jr (2013). CHARMM36 all-atom additive protein force field: validation based on comparison to NMR data. J. Comput. Chem.34, 2135–2145. 10.1002/jcc.23354

26

Huang P. Chandra V. Rastinejad F. (2014). Retinoic acid actions through mammalian nuclear receptors. Chem. Rev.114, 233–254. 10.1021/cr400161b

27

Ingredient (2022). COSMILE Europe. Available online at: https://cosmileeurope.eu/inci/detail/8246/lespedeza-cuneata-extract/(Accessed June 11, 2025).

28

Jang G. H. Kim H. W. Lee M. K. Jeong S. Y. Bak A. R. Lee D. J. et al (2018). Characterization and quantification of flavonoid glycosides in the prunus genus by UPLC-DAD-QTOF/MS. Saudi J. Biol. Sci.25, 1622–1631. 10.1016/j.sjbs.2016.08.001

29

Julious S. A. (2005). Sample size of 12 per group rule of thumb for a pilot study. Pharm. Stat.4, 287–291. 10.1002/pst.185

30

Ke Q. Gong X. Liao S. Duan C. Li L. (2022). Effects of thermostats/barostats on physical properties of liquids by molecular dynamics simulations. J. Mol. Liq.365, 120116. 10.1016/j.molliq.2022.120116

31

Khan N. Pawar A. P. Patil S. Patil P. R. Patil P. V. Patil P. N. et al (2024). Formulation and evaluation of polyherbal anti-acne patch. MGM J. Med. Sci.11, 234–241. 10.4103/mgmj.mgmj_137_24

32

Khunger N. Kumar C. (2012). A clinico-epidemiological study of adult acne: is it different from adolescent acne?Indian J. Dermatol Venereol. Leprol. Indian J. Dermatol Venereol. Leprol.78, 335–341. 10.4103/0378-6323.95450

33

Kim H. J. Kim Y. H. (2024). Exploring acne treatments: from pathophysiological mechanisms to emerging therapies. Int. J. Mol. Sci.25, 5302. 10.3390/ijms25105302

34

Kim T. H. Choi E. H. Kang Y. C. Lee S. H. Ahn S. K. (2001). The effects of topical alpha-hydroxyacids on the normal skin barrier of hairless mice. Br. J. Dermatol.144, 267–273. 10.1046/j.1365-2133.2001.04011.x

35

King S. Campbell J. Rowe R. Daly M.-L. Moncrieff G. Maybury C. (2023). A systematic review to evaluate the efficacy of azelaic acid in the management of acne, rosacea, melasma and skin aging. J. Cosmet. Dermatol.22, 2650–2662. 10.1111/jocd.15923

36

Kuo C.-W. Chiu Y.-F. Wu M.-H. Li M.-H. Wu C.-N. Chen W.-S. et al (2021). Gelatin/chitosan bilayer patches loaded with cortex Phellodendron amurense/Centella asiatica extracts for anti-acne application. Polym. (Basel)13, 579. 10.3390/polym13040579

37

Layton A. M. Dias da Rocha M. A. (2023). Real-world case studies showing the effective use of azelaic acid in the treatment, and during the maintenance phase, of adult female acne patients. Clin. Cosmet. Investig. Dermatol.16, 515–527. 10.2147/CCID.S396023

38

Lee S. W. Kim S. J. Kim H. Yang D. Kim H. J. Kim B. J. (2017). Effects of Prunus mume Siebold and Zucc. In the pacemaking activity of interstitial cells of cajal in murine small intestine. Exp. Ther. Med.13, 327–334. 10.3892/etm.2016.3963

39

Lee J. Ji J. Park S.-H. (2018). Antiwrinkle and antimelanogenesis activity of the ethanol extracts of Lespedeza cuneata G. Don for development of the cosmeceutical ingredients. Food Sci. Nutr.6, 1307–1316. 10.1002/fsn3.682

40

Leyden J. Bergfeld W. Drake L. Dunlap F. Goldman M. P. Gottlieb A. B. et al (2004). A systemic type I 5 alpha-reductase inhibitor is ineffective in the treatment of acne vulgaris. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol.50, 443–447. 10.1016/j.jaad.2003.07.021

41

Lim H.-J. Kang S.-H. Song Y.-J. Jeon Y.-D. Jin J.-S. (2021). Inhibitory effect of quercetin on propionibacterium acnes-induced skin inflammation. Int. Immunopharmacol.96, 107557. 10.1016/j.intimp.2021.107557

42

Linstrom P. (1997). NIST chemistry WebBook. NIST Stand. Ref. Database69. 10.18434/T4D303

43

Linstrom P. J. Mallard W. G. (2001). The NIST chemistry WebBook: a chemical data Re-source on the internet. J. Chem. Eng. Data46, 1059–1063. 10.1021/je000236i

44

Lu J. Cong T. Wen X. Li X. Du D. He G. et al (2019). Salicylic acid treats acne vulgaris by suppressing AMPK/SREBP1 pathway in sebocytes. Exp. Dermatol.28, 786–794. 10.1111/exd.13934

45

Lu B. Wang Z. Xu Y. Liu Y. Ruan B. Zhang J. et al (2025). Anti-aging and anti-inflammatory fulfilled through the delivery of supramolecular bakuchiol in ionic liquid. Supramol. Mater.4, 100093. 10.1016/j.supmat.2025.100093

46

Mark P. Nilsson L. (2001). Structure and dynamics of the TIP3P, SPC, and SPC/E water models at 298 K. J. Phys. Chem. A105, 9954–9960. 10.1021/jp003020w

47

Marks D. H. Prasad S. De Souza B. Burns L. J. Senna M. M. (2020). Topical antiandrogen therapies for androgenetic alopecia and acne vulgaris. Am. J. Clin. Dermatol.21, 245–254. 10.1007/s40257-019-00493-z

48

Mascarenhas-Melo F. Ribeiro M. M. Kahkesh K. H. Parida S. Pawar K. D. Velsankar K. et al (2024). Comprehensive review of the skin use of bakuchiol: physicochemical properties, sources, bioactivities, nanotechnology delivery systems, regulatory and toxicological concerns. Phytochem. Rev.23, 1377–1413. 10.1007/s11101-024-09926-y

49

McNutt A. T. Francoeur P. Aggarwal R. Masuda T. Meli R. Ragoza M. et al (2021). GNINA 1.0: molecular docking with deep learning. J. Cheminformatics13 (№ 1), 43. 10.1186/s13321-021-00522-2

50

Morimoto-Yamashita Y. Kawakami Y. Tatsuyama S. Miyashita K. Emoto M. Kikuchi K. et al (2015). A natural therapeutic approach for the treatment of periodontitis by MK615. Med. Hypotheses85, 618–621. 10.1016/j.mehy.2015.07.028

51

Osojnik Črnivec I. G. Skrt M. Polak T. Šeremet D. Mrak P. Komes D. et al (2024). Aspects of quercetin stability and its liposomal enhancement in yellow onion skin extracts. Food Chem.459, 140347. 10.1016/j.foodchem.2024.140347

52

Pareek A. Kapoor D. U. Yadav S. K. Rashid S. Fareed M. Akhter M. S. et al (2025). Advancing lipid nanoparticles: a pioneering technology in cosmetic and dermatological treatments. Colloids Interface Sci. Commun.64, 100814. 10.1016/j.colcom.2024.100814

53

Patel P. Garala K. Bagada A. Singh S. Prajapati B. G. Kapoor D. (2025). Phyto-pharmaceuticals as a safe and potential alternative in management of psoriasis: a review. Z. Naturforsch. C80, 409–430. 10.1515/znc-2024-0153

54

Puyana C. Chandan N. Tsoukas M. (2022). Applications of bakuchiol in dermatology: systematic review of the literature. J. Cosmet. Dermatol.21, 6636–6643. 10.1111/jocd.15420

55

Roehrborn C. G. Boyle P. Nickel J. C. Hoefner K. Andriole G. ARIA3001 ARIA3002 and ARIA3003 Study Investigators (2002). Efficacy and safety of a dual inhibitor of 5-alpha-reductase types 1 and 2 (dutasteride) in men with benign prostatic hyperplasia. Urology60, 434–441. 10.1016/s0090-4295(02)01905-2

56

Sayyafan M. S. Ramzi M. Salmanpour R. (2020). Clinical assessment of topical erythromycin gel with and without zinc acetate for treating mild-to-moderate acne vulgaris. J. Dermatol. Treat.31, 730–733. 10.1080/09546634.2019.1606394

57

Seneviratne C. J. Wong R. W. K. Hägg U. Chen Y. Herath T. D. K. Samaranayake P. L. et al (2011). Prunus mume extract exhibits antimicrobial activity against pathogenic oral bacteria: prunus mume extract exhibits antimicrobial activity. Int. J. Paediatr. Dent.21, 299–305. 10.1111/j.1365-263X.2011.01123.x

58

Silva-Weiss A. Bifani V. Ihl M. Sobral P. Gómez-Guillén M. (2014). Polyphenol-rich extract from murta leaves on rheological properties of film-forming solutions based on different hydrocolloid blends. J. Food Eng.140, 28–38. 10.1016/j.jfoodeng.2014.04.010

59

Stein C. J. Herbert J. M. Head-Gordon M. (2019). The poisson-boltzmann model for implicit solvation of electrolyte solutions: Quantum chemical implementation and assessment via sechenov coefficients. J. Chem. Phys.151, 224111. 10.1063/1.5131020

60

Sutaria A. H. Masood S. Saleh H. M. Schlessinger J. (2025). “Acne vulgaris,” in StatPearls (Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing).

61

Tanghetti E. A. Kawata A. K. Daniels S. R. Yeomans K. Burk C. T. Callender V. D. (2014). Understanding the burden of adult female acne. J. Clin. Aesthet. Dermatol.7, 22–30.

62

Valdés-Tresanco M. S. Valdés-Tresanco M. E. Valiente P. A. Moreno E. (2021). Gmx_MMPBSA: a new tool to perform end-state free energy calculations with GROMACS. J. Chem. Theory Comput.17, 6281–6291. 10.1021/acs.jctc.1c00645

63

Vanommeslaeghe K. Hatcher E. Acharya C. Kundu S. Zhong S. Shim J. et al (2010). CHARMM general force field: a force field for drug-like molecules compatible with the CHARMM all-atom additive biological force fields. J. Comput. Chem.31, 671–690. 10.1002/jcc.21367

64

Vasam M. Korutla S. Bohara R. A. (2023). Acne vulgaris: a review of the pathophysiology, treatment, and recent nanotechnology based advances. Biochem. Biophys. Rep.36, 101578. 10.1016/j.bbrep.2023.101578

65

Walker A. P. Basketter D. A. Baverel M. Diembeck W. Matthies W. Mougin D. et al (1997). Test guidelines for the assessment of skin tolerance of potentially irritant cosmetic ingredients in man. Food Chem. Toxicol. 35, 1099–1106. 10.1016/s0278-6915(97)00106-3

66

Wood A. J. J. Rittmaster R. S. (1994). Finasteride. N. Engl. J. Med.330, 120–125. 10.1056/nejm199401133300208

67

Yang J. H. Yoon J. Y. Kwon H. H. Min S. Moon J. Suh D. H. (2017). Seeking new acne treatment from natural products, devices and synthetic drug discovery. Dermatoendocrinol9, e1356520. 10.1080/19381980.2017.1356520

68

Yang Z. Zhang Y. Lazic Mosler E. Hu J. Li H. Zhang Y. et al (2020). Topical benzoyl peroxide for acne. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev.3, CD011154. 10.1002/14651858.CD011154.pub2

69

Yong L. X. Li W. Conway P. L. Loo S. C. J. (2025). Additive effects of natural plant extracts/essential oils and probiotics as an antipathogenic topical skin patch solution for acne and eczema. ACS Appl. Bio Mater.8, 1571–1582. 10.1021/acsabm.4c01742

70

Zhao F. Du L. Wang J. Liu H. Zhao H. Lyu L. et al (2023). Polyphenols from Prunus mume: extraction, purification, and anticancer activity. Food Funct.14, 4380–4391. 10.1039/d3fo01211e

71

Zhu C. Wei B. Li Y. Wang C. (2025). Antibiotic resistance rates in Cutibacterium acnes isolated from patients with acne vulgaris: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Front. Microbiol.16, 1565111. 10.3389/fmicb.2025.1565111

Summary

Keywords

5α-reductase, acne, bioactivity, cosmetics, phytochemicals, Prunus mume extract, shikimic acid, stability

Citation

Patronova E, Ilin E, Filatov V and Kalenikova E (2026) Novel prospectives of shikimic acid and Prunus mume extract for enhancing bioactivity on 5α-reductase and stability in cosmetic patches for acne treatment. Front. Nat. Prod. 4:1737986. doi: 10.3389/fntpr.2025.1737986

Received

02 November 2025

Revised

03 December 2025

Accepted

09 December 2025

Published

08 January 2026

Volume

4 - 2025

Edited by

Adriana K. Molina, University of Vigo, Spain

Reviewed by

Devesh U. Kapoor, Gujarat Technological University, India

Izamara Oliveira, Polytechnic Institute of Bragança (IPB), Portugal

Updates

Copyright

© 2026 Patronova, Ilin, Filatov and Kalenikova.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Viktor Filatov, viktor.filatov@fbm.msu.ru

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.