- Department of Energy, Politecnico di Torino, Torino, Italy

The Critical Heat Flux (CHF) is a physical phenomenon that may cause the deterioration of the heat transfer in the core of nuclear reactors, potentially leading to core damage. Its accurate prediction is therefore a crucial issue in nuclear reactor safety. To this aim, various empirical and mechanistic models have been proposed to estimate the CHF across various flow regimes and conditions, which however present some drawbacks: i) data scarcity in some parts of the input domain; ii) no information about prediction uncertainties; iii) difficult explainability and interpretability of the results. To address these issues, ensembles of Physics-Enhanced Neural Networks (PENNs) are considered to predict the CHF as a function of relevant physical input variables (e.g., pipe heated length and diameter, pressure, mass flux, outlet quality). Two different frameworks to integrate physics and data-driven NN-based strategies are here compared for the first time, to the best of the author’s knowledge. In the first, fixed-structure (prior) baseline models (i.e., the Groeneveld Look-Up Table-LUT and the mechanistic Liu model) are constructed relying on the existing knowledge on the physical phenomenon of interest, which serves as a reference solution; then, NN ensembles are employed to capture unknown, unexplored information from the mismatch (i.e., the residuals) between the real CHF values and the estimates produced by the knowledge-based models. In the second, the LUT and the mechanistic Liu model are directly implemented in the NN loss function for effective (physics- and data-driven) ensemble training. A case study is carried out with an extensive CHF database (published by the U.S. Nuclear Regulatory Commission with measurements in vertical uniformly-heated water-cooled cylindrical tubes) to demonstrate: i) the improved performance of the PENN-based approaches as compared to traditional knowledge-based models; ii) the PENN superior generalization capabilities over standalone data-driven NNs in the presence of small-sized datasets (i.e., a few tens or hundreds points); iii) the possibility to build robustness in the CHF predictions by bootstrap and PENN weights random reinitialization for quantifying uncertainty and estimating prediction intervals.

1 Introduction

Critical Heat Flux (CHF) is a fundamental parameter in the thermal-hydraulic design and safe operation of heat-generating systems, particularly nuclear reactors. CHF denotes the thermal limit at which the heat transfer from a heated surface to the coolant deteriorates drastically as the surface heat flux increases. Beyond this threshold, the cooling mechanism becomes insufficient, resulting in a sharp rise in surface temperature. Exceeding CHF conditions necessitates immediate shutdown procedures to prevent damage to the system and mitigate production losses. In severe cases, surpassing CHF can lead to significant structural failures, including fuel cladding rupture and potential core degradation in nuclear applications (Todreas and Kazimi, 2021; Khalid et al., 2024a). Two distinct mechanisms are primarily responsible for the onset of CHF: Departure from Nucleate Boiling (DNB) and dryout (DO). DNB typically occurs under low-quality flow conditions, where the coolant is predominantly in the liquid phase. In such cases, localized vapor production can form an insulating vapor blanket over the heated surface, suppressing nucleate boiling and leading to a rapid increase in surface temperature. In contrast, DO is characteristic of high-quality flow regimes, where a vapor core containing entrained droplets is surrounded by a thin liquid film along the channel walls. CHF due to DO occurs when this annular liquid film is depleted, eliminating the primary cooling mechanism at the surface. While both mechanisms are of concern in various heat transfer systems, their implications in nuclear reactors are particularly critical. DNB and DO can result in heat transfer deterioration severe enough to cause fuel cladding failure, and in extreme scenarios, lead to fuel melting. In conventional systems such as boilers and heat exchangers, DO may result in reduced thermal efficiency or mechanical failure, such as tube rupture. Given these risks, CHF is recognized as a key safety-related quantity in nuclear engineering. Its accurate prediction is essential during the thermal-hydraulic analysis and design phases to ensure operating conditions remain within safe margins. Predictive models and experimental validation are thus vital for maintaining system integrity and operational reliability (Zhao et al., 2020; 2021; Furlong et al., 2025a).

Extensive research has been devoted to understanding and predicting Critical Heat Flux (CHF), with the primary objective of developing a unified model capable of reliably forecasting its occurrence across a broad range of operating conditions and geometries. However, this endeavor remains challenging due to the strong dependence of CHF on reactor configuration, operational parameters, fuel rod geometry, and coolant thermophysical properties. Compounding this complexity is the lack of consensus on the fundamental mechanisms responsible for CHF onset. The precise triggering phenomena are still the subject of ongoing debate, largely due to the inherently complex nature of boiling heat transfer and phase-change dynamics (Celata et al., 1994; Bucci, 2017). As a result, the thermal engineering community has proposed a wide array of predictive approaches - numbering over 500 - that attempt to address various aspects of CHF behavior. These models can be broadly categorized into three principal frameworks (Kandlikar, 2001; Bruder et al., 2017; Groeneveld et al., 2018; Yang B.-W. et al., 2021): (i) empirical correlations developed through experimental data fitting (e.g., Hall and Mudawar, 2000; Todreas and Kazimi, 2021); (ii) Look-Up Tables (LUTs) derived from extensive experimental databases (Groeneveld et al., 2007; Groeneveld, 2019); and (iii) physics-based mechanistic models that attempt to resolve the underlying physical processes driving CHF (Okawa et al., 2004; Liu, 2022). Empirical correlations constitute a statistical modeling approach used to predict CHF based on observed relationships among experimentally measured variables. These correlations typically take the form of polynomial or other analytical expressions, enabling CHF estimation under conditions similar to those for which the underlying data were obtained. While widely employed due to their simplicity and computational efficiency, empirical correlations are inherently limited in their generalizability. Since they are derived from specific datasets, their predictive accuracy often deteriorates when applied outside the original experimental conditions or under differing boundary parameters. For instance, a correlation developed for a particular coolant, geometry, or pressure range may yield unreliable predictions when extrapolated to other configurations. The reliability of these models is also contingent upon the quality, representativeness, and scope of the experimental data used in their formulation. Consequently, empirical correlations must be applied with caution and rigorously validated against relevant experimental datasets prior to deployment in safety-critical applications. Several widely used empirical CHF models have been developed over the decades, each typically associated with either DNB or DO mechanisms. Notable examples include the Biasi (DNB) (Biasi et al., 1967), the Bowring (DO) (Bowring, 1972), the Westinghouse W-3 (DNB) (Tong, 1967), the Katto (DNB) (Katto, 1978; 1992), and the Electric Power Research Institute (EPRI) correlations (Reddy and Fighetti, 1983). The second major approach for predicting CHF is the use of Look-Up Tables (LUTs), which offer a systematic and relatively precise method for estimation. Unlike empirical correlations, LUTs are constructed from extensive experimental datasets, enabling interpolation across a wide range of operational parameters. However, the development of accurate LUTs necessitates considerable preparatory work, including the acquisition and rigorous analysis of large volumes of high-quality experimental data. A prominent example is the Groeneveld LUT (Groeneveld et al., 2007; Groeneveld, 2019), which was developed by aggregating data from 59 separate experiments. This comprehensive dataset contains nearly 25,000 entries, representing CHF measurements for uniformly heated vertical tubes under both DNB and DO conditions, and is parameterized by seven key input variables. In contrast, physics-based mechanistic models aim to predict CHF by incorporating assumptions grounded in the physical understanding of underlying flow boiling phenomena. These models typically solve conservation equations that are closed using empirically derived constitutive relationships (Zhao et al., 2020). While mechanistic models have the potential to provide greater insight into the governing processes, their development and application are inherently complex and demand a high degree of expertise. This is due, in part, to the dependence of CHF mechanisms on flow regime, channel geometry, and boundary conditions (Yan et al., 2021; Khalid et al., 2024a). A wide range of mechanistic models for flow boiling has been proposed in the literature. These can be broadly classified into six categories based on the hypothesized dominant DNB mechanism (Zhao et al., 2020): (i) liquid layer superheat limit, (ii) boundary layer separation, (iii) liquid flow blockage, (iv) near-wall bubble crowding, (v) liquid sublayer DO, and (vi) interfacial lift-off (Bruder et al., 2017). Among these, the liquid sublayer DO mechanism has received significant attention, supported by experimental evidence in internally heated round tubes (Katto, 1990). Notable sublayer DO-based models include those developed by Lee and Mudawwar (1988), Katto (1990), Celata et al. (1994), (1999), Liu et al. (2000), and Liu (2022). Despite the capabilities of empirical correlations, LUTs, and mechanistic models in predicting CHF across a broad range of input conditions, significant deviations from experimental measurements persist in various regions of the operational space (Groeneveld et al., 2007). These limitations have continued to motivate ongoing research efforts aimed at developing more accurate and robust predictive methodologies.

Recent advancements in computational power and optimization algorithms have enabled the emergence of purely data-driven approaches based on Machine Learning (ML) and Artificial Intelligence (AI) as viable alternatives to conventional CHF prediction methods (Huang et al., 2023). These include, among the others: Deep Neural Networks (DNNs), deep AutoEncoders (AEs), Deep Belief Networks (DBNs), Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs), Conditional Variational Autoencoders (CVAEs), Support Vector Machines (SVMs), Random Forests (RFs), and Gaussian Process Regression (GPR) (Alsafadi et al., 2025; Grosfilley et al., 2024; Khalid et al., 2024a; Kim et al., 2021; Kumar et al., 2024; Zhao et al., 2020; Zhou et al., 2024). Such techniques operate by learning patterns from training data without requiring explicit knowledge of the underlying physical processes. One of the principal advantages of ML- and AI-based models lies in their capacity to uncover complex, non-linear relationships within high-dimensional datasets - relationships that may be difficult or impossible to identify using traditional empirical or mechanistic methods. This capability often translates into improved predictive accuracy across diverse operating conditions. Additionally, once trained, these models are computationally efficient and inexpensive to deploy, further enhancing their practical appeal. The growing body of literature in this domain underscores the increasing interest and success of data-driven approaches in thermal-hydraulic applications (Qi et al., 2025).

Although standalone AI and ML methods offer the advantage of requiring minimal prior knowledge and no explicit mathematical modeling, their practical deployment is hindered by several notable limitations (Cicirello, 2024; Lye et al., 2025). Key challenges include: (1) poor data quality; (2) limited availability of reliable training data; (3) weak extrapolation and generalization capabilities under previously unseen conditions; (4) the presence of significant uncertainties; and (5) limited interpretability of the resulting models. A particularly critical concern is their susceptibility to generating unphysical or non-intuitive outputs, stemming from their purely data-driven and often “black-box” nature. As model complexity grows - often involving thousands to millions of tunable parameters depending on the algorithm and application - the potential for overfitting, instability, and loss of transparency increases. This poses a substantial barrier for high-stakes applications such as nuclear thermal-hydraulics, where model reliability, traceability, and interpretability are essential for ensuring safety and regulatory compliance. Data scarcity and poor data quality further exacerbate these challenges. For example, in some engineering problems and applications, traditional AI/ML architectures, such as DNNs, may require large volumes of high-quality data to attain satisfactory predictive performance (Hong et al., 2023; Shi and Zhang, 2022; Zhao et al., 2022; Zhu et al., 2022). Inadequate data, or datasets contaminated with noise, can significantly impair model training, leading to degraded performance or complete model failure. Although various data augmentation strategies have been proposed to alleviate the issue of limited data (Kim et al., 2021; Zhang et al., 2022; Alsafadi et al., 2025), such approaches still fall short in guaranteeing physically consistent outputs or providing interpretability, both of which are essential for deployment in critical engineering domains.

To address the limitations associated with purely data-driven models, recent research has focused on integrating domain-specific physical knowledge into the AI/ML framework, leading to the development of Physics-Enhanced Machine Learning (PEML) approaches1 (Furlong et al., 2025a; Mao and Jin, 2024; Zhao et al., 2020). These hybrid methodologies aim to combine the predictive power of data-driven techniques with the rigor and consistency of established physical laws governing nuclear systems. By embedding physical constraints and principles directly into the ML training process, PEML frameworks ensure that the learned models produce outputs that are not only data-consistent but also physically plausible and aligned with underlying conservation laws and mechanistic correlations. The fusion of reliable physical laws and data is expected to allow the model to generalize more effectively, to improve predictive accuracy, and to possibly enhance interpretability - key requirements for deployment in safety-critical fields such as nuclear engineering. Rather than relying solely on statistical patterns in the data, the learning algorithm is guided by physically informed structures or loss functions, enabling it to learn complex relationships while adhering to known physical behavior (Cicirello, 2024; Lye et al., 2025).

Given the complexity and non-linearity of the relationships between the physical input parameters and the CHF, in this paper Neural Networks (NNs) are selected as AI/ML techniques for their capability to capture intricate patterns and dependencies within the data (Zhao et al., 2020; Grosfilley et al., 2024). Then, the main objective is to systematically compare two different approaches to integrate physics and data-driven NN strategies, within a Physics-Enhanced Neural Network (PENN) framework:

1. The empirical Groeneveld LUT (Groeneveld et al., 2007; Groeneveld, 2019) and the mechanistic Liu model (Liu et al., 2000; 2012; Liu, 2022) are taken as (prior) reference, fixed-structure baseline solutions, since they rely on the existing knowledge on the physical phenomena of interest. Then, NNs are employed to capture unknown, unexplored information from the mismatch (i.e., the residuals) between the real CHF values and the estimates produced by the knowledge-based models, as proposed in Zhao et al. (2020). Notice that different from Zhao et al. (2020), the improved mechanistic physics-based model presented in Liu et al. (2012) is here adopted instead of that included in Liu et al. (2000). Hereafter, this approach will be referred to as Residual-based Physics-Enhanced Neural Network (Res-PENN).

2. The two reference models mentioned above (i.e., LUT and Liu) are implemented directly in the NN loss function for effective (hybrid physics- and data-driven) training. In other words, the PENN training is guided by two terms: i) the discrepancy between the NN prediction and the experimental data; ii) the difference between the NN estimates and the prior, baseline physics-based model outputs. Hereafter, this approach will be referred to as Hybrid Loss Function-based Physics-Enhanced Neural Network (HLF-PENN).

While the HLF-PENN methodology has proven beneficial across a variety of physics domains (Cuomo et al., 2022; De La Mata et al., 2023; Cicirello, 2024), including but not limited to fluid dynamics (Jin et al., 2021), structural mechanics (Diao et al., 2023; Marino and Cicirello, 2023; Yang et al., 2025), and heat transfer (Karpatne et al., 2017; Cai et al., 2021; Jalili et al., 2024), to the best of the author’s knowledge, few or no applications to CHF prediction in nuclear reactors are available in the open literature (Ahmed et al., 2025). Also, it is the first time that the Res-PENN and HLF-PENN approaches are systematically compared, with particular reference to the task of estimating CHF in the presence of very scarce data (i.e., a few tens or hundreds training patterns). This aspect is of paramount importance in the nuclear industry, where collecting a large amount of high-quality data is often too costly (and sometimes even impossible).

Finally, the uncertainty in CHF predictions of the two configurations above is quantified by an ensemble-based approach, conceived as an original combination of two nested procedures. On the one hand, we resort to the bootstrap method, i.e., a non-parametric statistical approach, in which many different NN models are trained each time using a different set of data, obtained by random sampling with replacement of the original training set. The resulting ensemble of NN models is then exploited to construct an empirical probability distribution of output responses (CHF predictions). This distribution reflects the portion of NN uncertainty due to the presence of a finite-sized (thus limited and incomplete) training dataset (Efron and Tibshirani, 1994; Abrate et al., 2023a; b). On the other hand, we adopt an initialization-based strategy, where different randomized weight/bias starting values are used to train a set of NN models, each of which subsequently explores a different solution space to attempt to find a global minimum of the objective function (LeCun et al., 2015; Furlong et al., 2025a). This approach allows us to assess the portion of uncertainty resulting from other sources than finiteness of the training dataset, such as randomness in the training process, model architecture, etc. (Yaseen and Wu, 2023; Tan et al., 2023).

The proposed methods are compared using the United States Nuclear Regulatory Commission (USNRC) CHF dataset from (Groeneveld, 2019) made available by the Working Party on Scientific Issues and Uncertainty Analysis of Reactor Systems (WPRS) Expert Group on Reactor Systems Multi-Physics (EGMUP) task force on AI and ML for Scientific Computing in Nuclear Engineering projects, promoted by the OECD/NEA (Le Corre et al., 2024).

The remainder of the paper is organized as follows. In Section 2, a detailed literature review on AI and ML methods for CHF estimation is provided. In Section 3, the CHF prediction problem is rigorously stated, while the PENN-based ensembles selected to address it are presented in detail in Section 4. The case study is described in Section 5, while the corresponding results obtained by the PENNs are thoroughly discussed in Section 6. Finally, some conclusions are drawn in Section 7.

2 Artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning (ML) for critical heat flux (CHF) prediction: a detailed literature review

With recent advances in computational capabilities and optimization techniques, methods based on purely data-driven Machine Learning (ML) and Artificial Intelligence (AI) provide an alternative approach to existing tools (Huang et al., 2023). These approaches rely on fitting parameters to training data and do not require any knowledge about the physical world or problem. The primary benefits of these approaches are their ability to find relationships that may not be readily apparent in the data (often leading to higher overall accuracy in comparison with traditional methods) as well as their inexpensive nature and quick performance post-training. This is demonstrated by the flourishing literature in the field (Qi et al., 2025). With reference only to the last 5–10 years (He and Lee, 2018), employ Support Vector Machines (SVMs) for data-driven CHF look-up table construction based on sparingly distributed training data points, showing appreciable performance also in extrapolation tasks. The same authors compare various machine learning methods, including ν-SVM, Back-Propagation Neural Network (BPNN), Radial Basis Function (RBF), General Regression Neural Network (GRNN), and Deep Belief Network (DBN) in the task of estimating CHF on microstructure surface by means of data from horizontal silicon specimens of cylindrical pillars with square arrangements (He and Lee, 2020). In (Park et al., 2020), Artificial Neural Networks (ANNs) are used to predict the wall temperature from a nucleate boiling heat transfer model at a given CHF within the thermal-hydraulic system code SPACE. ANNs are adopted also by Mudawar et al. (2024) for predicting flow boiling heat transfer and critical heat flux in both microgravity and Earth gravity for space applications. In (Jiang et al., 2020), a hybrid approach based on Gaussian Process Regression (GPR) and Ant Colony Optimization (ACO) is proposed for the prediction of CHF: in this model, the ACO algorithm is employed to optimize the hyper-parameters of GPR based on a training set derived from two published literature sources (Hedayat, 2021). develops cascade feed-forward Artificial Neural Networks (ANNs) with Deep Learning (DL) features to predict a full range CHF in different LWRs via parallel multi-processing to reduce the computational cost. In (Kim et al., 2021) a Deep Belief Network (DBN) and a Residual Network (ResNet) are combined to predict CHF in narrow rectangular channels in a steady state condition. DBN is used to perform feature extraction in an unsupervised pre-training phase, whereas ResNet is employed for (supervised) CHF prediction, as it improves accuracy through residual learning. The combined neural network is trained by means of an augmented “pseudo-dataset”, synthetically generated using four existing CHF correlations to cover a wide range of conditions involving thermal-hydraulic, geometric, and heater parameters. In (Rassoulinejad-Mousavi et al., 2021) Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) and Transfer Learning (TL) are compared in the task of detecting CHF in pool boiling, with the main objective of progressively adapting the trained models to new datasets collected under different conditions. In (Swartz et al., 2021) the effectiveness of three ML models (i.e., Least Absolute Shrinkage and Selection Operator-LASSO, Deep Feedforward Neural Networks-DFNN, and Random Forest-RF) is assessed in the predictions of critical heat fluxes for pillar-modified surfaces. In (Rohatgi et al., 2022), the authors use a data augmentation methodology based on Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs) to expand the training set for an ANN to predict the power at which DNB occurs in Pressurized Water Reactors (PWRs) as a function of the outlet pressure, inlet temperature and inlet mass flux as the input features, within the PWR subchannel and bundle tests (PSBT) benchmark. An approach based on data augmentation is presented also by Alsafadi et al. (2025), where a Conditional Variational AutoEncoder (CVAE) is employed to produce specific input data instances (e.g., data samples at conditions and domains desired by the user) starting from an important set of CHF experimental data. The CVAE performance is satisfactorily compared to that of Deep Neural Networks (DNNs) also in the uncertainty quantification task, obtained by (CVAE) repeated sampling and (DNN) ensembles. The use of DNNs is explored also by Khalid et al. (2024a), where an ensemble of deep sparse AutoEncoders (AEs) is used as a base-learner to extract robust features from the experimental data and a DNN is built on top of the ensemble of deep sparse AEs as a meta-learner to predict the CHF based on six input parameters (Zhang et al., 2022). compare three machine learning methods, the ε-Support Vector Machine (ε-SVM), Back Propagation Neural Network (BPNN) and Random Forest (RF), in the prediction of CHF on downward facing surfaces, also with the aid of synthetic pseudo-data generated by a simple fitting process. Several other papers are devoted to the comparison of purely data-driven AI/ML techniques on CHF predictions (Kim et al., 2022a; Khalid et al., 2023; Li et al., 2024; Kumar et al., 2024). Take into account ANNs, RFs, SVMs and LUT. In (Grosfilley et al., 2024) ν-SVMs, GPR, and ANNs are applied to the 2006 Groeneveld CHF database (nearly 25,000 data points). The same database is used by Zhou et al. (2024) to carry out an assessment of some state-of-the-art AI methods for critical heat flux prediction (i.e., ANNs, CNNs, Transformers with self-attention mechanism and Transfer Learning-TL) (Cabarcos et al., 2024). use a geometrical model of a rectangular channel at an inclined angle to evaluate the predictive performance of five ML models using collected CHF data: ANNs, AdaBoost, RF, XGBoost, and SVM. Most of these techniques (with the addition of K-Nearest Neighbors-KNN) are also embraced by Khalid et al. (2024b) to study the dependence of CHF in vertical flow systems on dimensional and dimensionless parameters. Finally (Quadros et al., 2024), analyze bubble departure and lift-off boiling model by computational intelligence techniques and hybrid algorithms, such as ANNs, the Fuzzy Mamdani model, Adaptive Neuro-Fuzzy Inference System (ANFIS) and ANN trained particle swarm optimization (ANN-PSO). The primary benefits of these approaches are their ability to find relationships that may not be readily apparent in the data - often leading to a higher overall accuracy in comparison with traditional methods - as well as their inexpensive nature and quick performance post-training. In 2022, under the guidance of the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) Nuclear Energy Agency (NEA), the Task Force on Artificial Intelligence and Machine Learning for Scientific Computing in Nuclear Engineering was formed with the objective of creating an ML benchmark for CHF prediction (Le Corre et al., 2024). Phase one of this project focused on feature analysis and the training and evaluation of ML regression models on the Groeneveld dataset (Groeneveld et al., 2007; Groeneveld, 2019) using the following parameters (or some of them) as inputs: tube diameter, heated length, pressure, mass flux, and equilibrium quality.

While standalone ML-based tools require minimal prior knowledge and almost no explicit mathematical modeling, they could fall short due to the following challenges (Cicirello, 2024; Lye et al., 2025): 1) poor data quality; 2) limited data availability; 3) poor extrapolation and generalization performance over unseen conditions; 4) the presence of uncertainties; and 5) the lack of model interpretability. In particular, they can be prone to undesired, unphysical solutions due to their purely data-driven nature and “black-box” feature. Because their complexity increases as the number of fitting parameters scales up, these fitting parameters are often on the order of thousands or even millions, depending on the problem and ML technique. Highly sensitive applications, such as nuclear analysis, require the development of a framework that emphasizes explainability and reliability in the models’ predictions. Data scarcity and poor quality are other substantial concerns in attempting to train data-driven models using the limited datasets available when working with experimental data. In some engineering problems and applications, traditional ML approaches, such as DNNs, may require a relatively large amount of high-quality data to achieve acceptable performance. Providing inadequate amounts of data or entries with a high degree of noise can significantly degrade model performance to the point of a complete breakdown of the training process. Although some data augmentation approaches (Kim et al., 2021; Zhang et al., 2022; Alsafadi et al., 2025) have been shown to be effective at mitigating the scarcity concern, they still lack explainability or a guarantee that completely nonphysical results will not be produced.

Recent studies have tackled the issues above by complementing data-driven learning with the consistency of the underlying physics of the nuclear system being studied, introducing the so-called Physics-Enhanced Machine Learning (PEML) approach, which yields predictions that are often more accurate, reliable, and interpretable. Known physics principles are introduced to guide the ML learning process, which ensures that the model’s predictions are consistent with the underlying physical laws describing the phenomena. By doing so, the ML model learns from the data and at the same time obeys the constraints imposed by physical correlations/models (Cicirello, 2024; Lye et al., 2025). Within the CHF prediction framework (Zhao et al., 2020), propose a hybrid, integrated “grey box” method, which leverages the prior Domain Knowledge (DK) in the field by using a “baseline reference model” in combination with data-driven ML. This hybrid approach first uses an established model, such as a reliable physical law, an empirical thermal-hydraulic correlation or mechanistic model, to compute an estimate for a target output (e.g., the CHF). The estimate value is then corrected by an ML model trained to predict the residual between those outputs and known experimental values. This correction will compensate for the bias and undiscovered mismatch between the DK-based model and actual observations. This arrangement may be easier to interpret because the bulk of prior physical knowledge is provided by the base model, reducing the amount of inferred knowledge required by the ML component. Structuring the model in this manner may offer higher interpretability, performance benefits in comparison with stand-alone ML methods, and built-in resistance to the deleterious effects of data limitations, as previously demonstrated in chemical, electrical and aerospace engineering applications (Acuña et al., 1999; Forssell and Lindskog, 1997; Wu et al., 2018). In (Zhao et al., 2020) two prior DK references are used: the Groeneveld 2006 LUT and the Liu model, one of the most recent and successful in the series of physics-driven tools based on the relatively well-accepted liquid sublayer DO mechanism; with respect to ML techniques, ANNs and RFs are chosen and compared. The same authors employ such an approach combining ANNs and RFs with a novel mechanistic model of DNB to achieve superior predictive capabilities for rod bundles (Zhao et al., 2021). The hybrid, residual-based method by Zhao et al. (2020), (2021) has apparently become very popular in the nuclear community and has given rise to an impressively large number of works in the same line of research. For example, in Kim et al. (2022b) ANNs and RFs are coupled with conventional empirical correlations (namely, Henry and Groeneveld-Stewart) for predicting the minimum film boiling temperature, a crucial parameter in post-CHF conditions by determining the collapse of stable vapor film on overheated surface. In (Mao and Jin, 2024) DNNs, CNNs, and RFs are chosen as the ML techniques and paired with the Biasi correlation, the Groeneveld LUT, or the Zuber correlation as the reference prior models. The authors carry out also uncertainty quantification via input perturbation to capture data uncertainty (but not uncertainty resulting from other sources, such as randomness in the training process, model architecture, or extrapolation, among others). The RF model using the LUT as the base model are shown to have the smallest relative error. The Biasi correlation is taken as the DK physics-based model also in (Qiu et al., 2024), where it is hybridized with ANNs, integrated into the self-developed analysis code ARSAC and then validated using the ORNL-THTF experiment. The paper by Khalid et al. (2023) provides a comparison between the stand-alone LUT and ANN, SVM, and RF residual-based hybrids, each of which using the LUT as the DK-based model. This study concludes that hybrid models exhibit better accuracy in every case in comparison with the stand-alone LUT and nonhybrid ML variants. In (Niu et al., 2024) DNNs are combined with Mirshak et al. (1959), Katto (1981) and Kaminaga et al. (1988) empirical correlations to predict the specific location of CHF occurrence, in addition to its magnitude, in rectangular channels. Finally, in (Furlong et al., 2025a) the hybrid approach implements the Biasi and Bowring CHF empirical correlations (Todreas and Kazimi, 2021) as prior models and considers three different ML methods for their abilities to quantify model uncertainties, i.e., DNN ensembles, Bayesian neural networks (BNNs), and deep Gaussian processes (DGPs). The proposed approaches are integrated within the CTF subchannel code via a custom Fortran framework and their performances are evaluated using two validation cases, i.e., a subset of the Nuclear Regulatory Commission CHF database and the Bennett dryout experiments, in Furlong et al. (2025b).

3 Problem statement: critical heat flux (CHF) prediction in nuclear reactors

The objective of the present study is to develop an accurate and robust predictive framework for Critical Heat Flux (CHF), a parameter of critical importance for ensuring the safe operation of water-cooled nuclear reactors. CHF prediction constitutes a complex heat transfer problem governed by a set of M key physical variables, each measured under specific boundary conditions at a generic observation point zi = [zi,1, zi,2, … , zi,j, … , zi,M]. These input variables typically encompass both geometric and hydraulic parameters, such as hydraulic or equivalent diameter (D), heated length (L), pressure (P), mass flux (G), outlet quality (X), inlet subcooling (Δhin) and inlet temperature (Tin). CHF prediction models may utilize the full set of these physical inputs (Ahmed et al., 2025), though in practice, a carefully selected subset is often employed to reduce model complexity and enhance generalizability. Existing analytical models for CHF prediction in convective boiling flows predominantly rely on a core set of input parameters, including pressure, P, local mass flux, G, channel diameter, D, and local equilibrium quality, X (Le Corre et al., 2024; Grosfilley et al., 2024). In some cases, additional parameters such as the heated length (L) are incorporated to improve model accuracy. Alternative modeling strategies also exist, employing input formulations based on saturated fluid properties in place of pressure (P), or utilizing non-dimensional representations. Such approaches, as illustrated in Hall and Mudawar (2000), have the potential advantage of improved generality and applicability across a range of working fluids. For the sake of CHF prediction, we consider the availability of a dataset Dbuild =

⁃ The measurement matrix Z

⁃ The corresponding CHF measurements qCHF =

The dataset Dbuild contains all the

4 Methods adopted in this work

Given the complexity and non-linearity of the relationships between the physical input parameters and the CHF, Neural Networks (NNs) are particularly well-suited for this task due to their capability to model intricate patterns and dependencies within the data (Zhao et al., 2020; Grosfilley et al., 2024). In brief, a feed-forward NN is essentially a collection of multiple layers (at least three: input, hidden, output) of fully connected units (called nodes or neurons), capable of nonlinear mapping via activation functions between the layers. From a mathematical viewpoint, NNs consist of a set of nonlinear (e.g., sigmoidal) basis functions (one for each neuron), with internal adaptable parameters/coefficients (namely, weights and biases) that are at first randomly initiated from a uniform distribution and then adjusted by a process of training (on many different input/output data examples), i.e., an iterative process of regression error minimization (backpropagation). The “depth” of these models (i.e., the number of hidden layers) influences the complexity of information gained from the training set, with early layers extracting coarse features with the finer features extracted in deeper layers. NNs with (far) more than two hidden layers are often referred to as Deep Neural Networks (DNNs) (Nassif et al., 2019; Alsafadi et al., 2025). NNs have been demonstrated to be universal approximants of continuous nonlinear functions (under mild mathematical conditions) (Cybenko, 1989), i.e., in principle, a NN model with a properly selected architecture can be a consistent estimator of any continuous nonlinear function. When a model is finished training, it is completely deterministic and will produce an identical output when given an identical input. Further details about NN regression models are not reported here for brevity; the interested reader may refer to the cited references and the copious literature in the field. Notice that the use of NNs (and DNNs) regression models in this work is mainly based on: (i) theoretical considerations about the (mathematically) demonstrated capability of NN regression models of being universal approximants of continuous nonlinear functions (Cybenko, 1989); (ii) the proven ability to carry out satisfactory predictions of CHF in a wide variety of conditions (see the relevant body of literature cited in Sections 1 and 2); (iii) the experience of the author in the use of NN regression models for mapping complex nonlinear dependences embedded in model codes of safety-critical systems (Pedroni and Zio, 2015; 2017; Pedroni, 2022; 2023).

NNs (and DNNs) are here chosen as AI/ML tools. Then, domain knowledge in the field and/or physics principles about the CHF are introduced to guide the NN learning process within a Physics-Enhanced Neural Network (PENN) framework. This approach ensures that the model’s predictions are consistent with the prior knowledge available and with the underlying physical laws describing the phenomena: in other words, the network learns from the data and at the same time obeys the constraints imposed by physical correlations/models and by background knowledge (Cicirello, 2024; Lye et al., 2025).

In Section 4.1, the two reference (prior) domain knowledge-based models used to “inform” and “enhance” the NN algorithms are briefly summarized. In Section 4.2, the PENN-based approaches here employed for estimating CHF in nuclear reactors (i.e., the Res-PENN and the HLF-PENN) are described in detail. In Section 4.3, the process relying on bootstrapped ensembles for uncertainty quantification in the PENN predictions of CHF is presented. Finally, in Section 4.4, all the quantitative metrics introduced for assessing the performance of PENNs against standalone domain knowledge-based models and pure data-driven NN techniques are listed.

4.1 Reference (prior) domain knowledge-based models

The empirical (data-based) Groeneveld Look-Up Table (LUT) (Groeneveld et al., 2007; Groeneveld, 2019) and the mechanistic, physics-based Liu model (Liu et al., 2000; 2012; Zhao et al., 2020; Liu, 2022) are selected and briefly summarized in Sections 4.1.1 and 4.1.2, respectively.

4.1.1 The empirical (data-driven) Groeneveld look-up table (LUT)

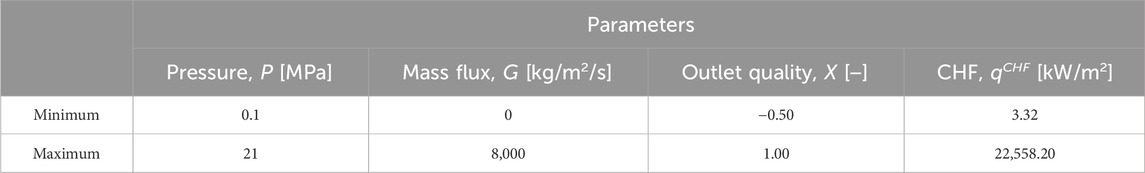

The Groeneveld Look-Up Table (LUT) (Groeneveld et al., 2007; Groeneveld, 2019) remains one of the most widely adopted and reliable data-driven tools for CHF prediction within the contemporary nuclear thermal-hydraulics community. Specifically, the LUT is based on a standardized and extensively validated database developed for a water-cooled vertical round uniformly heated channel with 8 mm inner diameter. This database comprises over 30,000 CHF data points, spanning a broad range of operating conditions, including mass fluxes from 0 to 8,000 kg/m2∙s, pressures from 0.1 to 21 MPa, and local equilibrium qualities from −0.50 to 1.00, as summarized in Table 1. Designed to support safe and reliable engineering decisions, the CHF LUT provides a comprehensive and consistent reference for a wide array of thermal-hydraulic applications. Among its key advantages are its broad applicability, user-friendly implementation, and the absence of iterative procedures typically required in predictive modeling, which implies very low computational cost. Also, the LUT is applicable to both DNB and DO scenarios. These features make the LUT a practical and efficient tool for routine CHF estimation (Groeneveld et al., 2007). To extend the applicability of the LUT beyond the reference geometry (i.e., 8 mm), Groeneveld et al. (2007) proposed a general correction equation to account for variations in channel diameter (from 2 to 16 mm). This correction is expressed as:

Table 1. Parameter ranges of the empirical (data-driven) Groeneveld Look-Up Table (LUT) (Groeneveld et al., 2007; Groeneveld, 2019).

4.1.2 The mechanistic physics-based Liu model

The mechanistic model developed by Liu et al. (2000), Liu et al. (2012), Liu (2022), Zhao et al. (2020) represents one of the most recent and prominent physics-based approaches for predicting CHF, grounded in the relatively well-established liquid sublayer dryout (DO) mechanism. This model postulates that the onset of Departure from Nucleate Boiling (DNB) occurs due to the complete evaporation of a thin, superheated liquid sublayer situated beneath a vapor blanket adjacent to the heated surface. The vapor blanket itself is assumed to form through the coalescence of vapor bubbles generated near the wall during nucleate boiling. Based on this physical interpretation, a heat balance can be applied to the liquid sublayer, from which a simplified governing equation is derived as

Notice that different from (Zhao et al., 2020), for the implementation of PENNs the improved mechanistic physics-based model presented in Liu et al. (2012) is here adopted instead of the one included in Liu et al. (2000). The model takes into account the microscopic bubble dynamics and integrates it within the liquid sublayer DO mechanism investigated in previous literature works (Liu et al., 2000). The forces exerted on the vapor blankets are duly considered to determine the liquid sublayer thicknesses and relative velocities of the vapor blankets through force balances in the radial and axial direction, respectively. It is worth noting that the referthan Liu model (Liu et al., 2000) was developed for DNB, which usually occurs in the subcooled and low-quality region: coherently, it was validated on 2,482 data characterized by outlet quality X ranging only between −0.6 and 0. Instead, the improved model is demonstrated to perform better that the original one in a wider range of thermodynamic conditions, as verified on 2,587 experimental data from both the subcooled and saturated flow boiling regions (the outlet quality X ranges between −0.4 and 1.0) (Table 2). In detail, the new model shows a lower bias and a higher precision (i.e., lower dispersion): the mean values of the ratio of the predicted to experimental CHF values (namely,

Table 2. Parameter ranges of the mechanistic physics-based Liu model (Liu et al., 2000; Liu et al., 2012).

4.2 Physics-enhanced neural network (PENN) strategies employed

The empirical (data-based) Groeneveld Look-Up Table (LUT) (Groeneveld et al., 2007; Groeneveld, 2019) and the improved mechanistic physics-based Liu model (Liu et al., 2012) are used in two different ways to incorporate the available background knowledge and physical principles within data-driven NN-based strategies:

1. They are taken as fixed-structure (prior) baseline models, which serve as reference solutions. Then, NN models are employed to capture unknown, unexplored information from the mismatch (i.e., the residuals) between the real CHF values and the estimates produced by the knowledge-based and physical models. The approach has been proposed by Zhao et al. (2020), but it has been coupled with the original Liu model (Liu et al., 2000) and tested on a different, smaller dataset with respect to the one of the present article (actually, the tube geometry and inlet conditions for the present database are in a wider and more extreme parameter range, particularly with respect to the outlet quality X and flow boiling conditions, both subcooled and saturated). The approach is hereafter referred to as Res-PENN (Section 4.2.1).

2. The reference models (i.e., LUT and improved Liu) are directly integrated into the NN loss function definition for effective (physics- and data-driven) training. In this way, domain knowledge-based physics principles guide the learning process, so that the model’s predictions are consistent with the physical principles underlying the phenomena and the corresponding body of knowledge. In other words, the network learns from the data, while at the same time obeying the constraints imposed by the prior, fixed-structure reference models (Section 4.2.2).

4.2.1 Residual-based physics-enhanced neural network (Res-PENN)

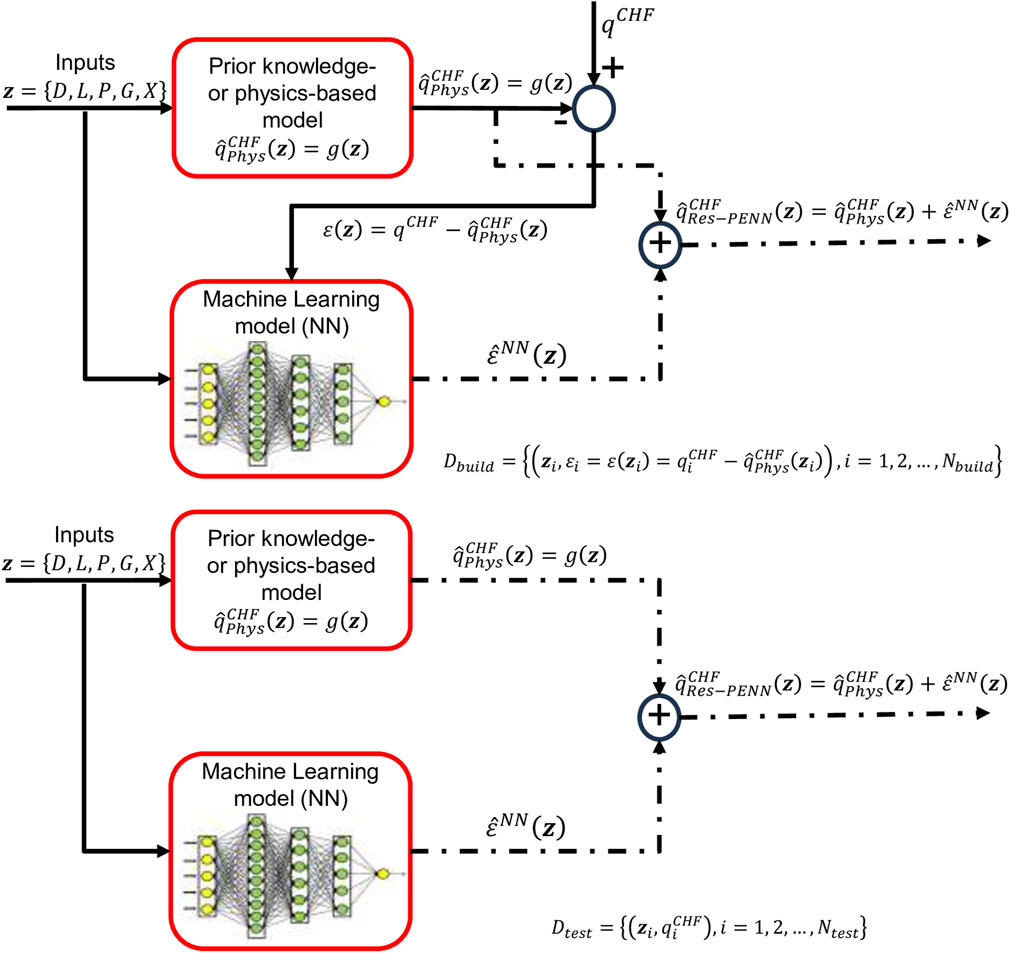

In the Residual-based Physics-Enhanced Neural Network (Res-PENN) approach proposed by Zhao et al. (2020), machine learning (i.e., the NN) compensates for biases in classical domain knowledge- or physics-based models and discerns information from the discrepancy between target values and those predicted by reference models. As depicted in Figure 1, during both the training and testing stages of Res-PENN, a conventional knowledge-based, physical or mathematical model g(z), such as the Groeneveld LUT (Groeneveld et al., 2007; Groeneveld, 2019) or the mechanistic physics-based Liu model (Liu et al., 2000; Liu et al., 2012), is selected to represent the “prior” knowledge in the field, or Domain Knowledge (DK) (Zhao et al., 2020). Rather than computing the target value directly, the NN is employed to estimate the disparity (or discrepancy, residual) between the actual target (experimental) value and the prediction from the foundational model. For instance, in a typical CHF study, an input vector z often comprises key thermal fluid quantities like pressure (P), mass flux (G), equilibrium quality (X), channel hydraulic diameter (D), inlet subcooling (Δhin), inlet temperature (Tin). This vector z is processed by the prior model

Figure 1. Conceptual structure for the Residual-based Physics-Enhanced Neural Network (Res-PENN) framework during (A) training/validation (top) and (B) testing phases (bottom).

4.2.2 Hybrid loss function-based physics-enhanced neural network (HLF-PENN)

Hybrid Loss Function-based Physics-Enhanced Neural Networks (HLF-PENNs) represent a novel class of modeling frameworks that combine the predictive capabilities of modern machine learning with the rigor of classical physical laws and/or background domain knowledge on the physical phenomena of interest. The primary objective of HLF-PENNs is to embed well-established physical principles directly into the Neural Network (NN) training process, using them as constraints or penalty functions to guide model learning and thereby ensure physically consistent predictions and improved extrapolation performance (Raissi et al., 2019). Unlike conventional data-driven approaches that rely solely on observational data, HLF-PENNs incorporate sound domain knowledge and/or reliable physical laws to inform the learning process, which may also contribute to enhanced interpretability and reduce the likelihood of generating unphysical outputs. By explicitly incorporating reliable knowledge- and/or rigorous physical law-based loss terms, HLF-PENNs tend to yield results that are often more transparent or, at least, aligned with theoretical expectations. It is worth mentioning that HLF-PENNs were originally introduced to address two primary categories of problems: (i) data-driven solutions of Partial Differential Equations (PDEs), and (ii) data-driven discovery of governing PDEs from data. In this framework, NNs are trained not only on data but also under constraints imposed by known physical laws. These laws - typically expressed in the form of PDEs - are embedded into the network’s loss function or imposed as constraints on the outputs, thereby enforcing physical consistency and possibly improving the interpretability of the model predictions (Farea et al., 2024). HLF-PENNs have demonstrated the capability to solve a broad class of differential equations, including classical PDEs, fractional differential equations, integro-differential equations, and stochastic PDEs. A growing body of literature illustrates their successful application across diverse physical domains (Cuomo et al., 2022; De La Mata et al., 2023; Cicirello, 2024). Notable examples include fluid dynamics solutions to the incompressible Navier-Stokes equations (Jin et al., 2021), heat transfer problems (Karpatne et al., 2017; Cai et al., 2021; Jalili et al., 2024), solid and structural mechanics simulations (Diao et al., 2023; Marino and Cicirello, 2023; Yang et al., 2025), and nuclear safety analysis (Antonello et al., 2023; Lai et al., 2024; Lye et al., 2025), highlighting the versatility and expanding relevance of PENNs in computational physics. Finally, it must be noted that while HLF-PENNs are more often associated with dynamic systems described by differential equations, in this work it is applied to a static model description, i.e., the empirical Groeneveld LUT and the improved Liu model.

HLF-PENNs often incorporates sound knowledge-based and rigorous physical constraints, equations and laws into the loss function using a Mean Squared Error (MSE)-like penalty, similar to conventional NNs (Yang L. et al., 2021; Stock et al., 2024; Pensoneault and Zhu, 2024; Ahmed et al., 2025). In other words, the HLF-PENN training is guided by two terms: i) the discrepancy between the NN prediction

The loss term associated with the knowledge- and mechanistic physics-related residuals (

The global (hybrid) loss function is then defined by weighing contributions (1) and (2) above by means of another hyperparameter λ to be optimized through validation and it is defined as in the following Equation 3 (Figure 2):

After training, which proceeds exactly as for classical NNs, the system has learnt how to approximate the CHF across the defined domain.

Figure 2. Conceptual structure of the Hybrid Loss Function-based Physics-Enhanced Neural Network (HLF-PENN).

A final word of caution is in order with respect to the (possibly increased) “interpretability” of our HLF-PENN model with respect to pure data-driven NN approaches. On the one hand, an argument for higher interpretability could be made by the inclusion of the improved mechanistic Liu model in the loss function (3) (i.e., when

4.3 Uncertainty quantification on CHF predictions by bootstrapped PENN ensembles

When employing the approximation of system outputs generated by a PENN empirical regression model, additional sources of uncertainty are introduced, which must be carefully assessed - particularly in safety-critical domains such as nuclear power plant technology. These uncertainties primarily arise from three key factors:

a. The set Dbuild (= Dtrain

b. The selection of the network architecture itself may be suboptimal. For instance, choosing an inappropriate number of hidden neurons - either too few or too many - can impair the model’s generalization capability. A balance between model complexity and generalization can be achieved by managing the number of parameters and adopting appropriate training strategies, such as early stopping (Zio, 2006).

c. Once trained, neural networks behave as deterministic functions, yielding identical outputs for repeated evaluations of the same input. However, when multiple networks are independently trained - differing in aspects such as weight initialization, hyperparameters, or optimization procedures - they often produce slightly different outputs for the same input. These variations can be interpreted as samples from an underlying predictive distribution, facilitating uncertainty quantification. Additionally, convergence to a global minimum of the loss function is not guaranteed during training. Optimization algorithms may converge to suboptimal local minima or may be halted prematurely before reaching a satisfactory error threshold (Zio, 2006; Furlong et al., 2025a). These aspects introduce further uncertainty that must be accounted for when assessing the reliability and robustness of neural network-based predictions.

Thus, due to the uncertainties, for given model input parameters/variables, the model output (i.e., the CHF prediction) can vary within a range of possible values (e.g., within a Prediction Interval-PI) (Efron and Tibshirani, 1994). The uncertainty described in item a) above is related to the limited size of the (possibly noisy) dataset and is here quantified by bootstrapping (Efron and Thibshirani, 1994). This approach can quantify the uncertainty by considering an ensemble of PENNs built on B different data sets that are sampled with replacement (bootstrapped) from the original one (Zio, 2006). From each bootstrap data set

4.4 Performance metrics

A combination of more than one statistical measure is used to comprehensively assess the proposed PENN models’ performance. The following metrics, commonly used in the nuclear engineering sector and suggested by Le Corre et al. (2024), are employed to assess the performance of the proposed method on the training, validation and test datasets, Dtrain =

⁃ the relative Root Mean Squared Percentage Error (rRMSPE), calculated as in Equation 4:

⁃ the relative Mean Absolute Percentage Error (rMAPE), computed as in Equation 5:

⁃ the normalized Root Mean Squared Percentage Error (nRMSPE), defined in Equation 6 as the RMSE divided by the estimated mean value of the (output) dataset

⁃ the Q2-error, evaluated as in Equation 7:

The relative percentage RMSE (

The mean value

The quantitative indicators above are used for hyperparameters optimization and ensemble (NN and PENN) model construction and evaluation. All the comparisons are carried out employing the early stopping method to avoid overfitting and guarantee satisfactory generalization capabilities to new (test) data (i.e., not employed during model construction).

With respect to the quantification of uncertainty, the use of bootstrapped ensembles produces a

where

where

5 Case study: the U.S. nuclear regulatory commission (NRC) CHF database

The present study employs the Critical Heat Flux (CHF) dataset compiled by the U.S. Nuclear Regulatory Commission (NRC), as documented in Groeneveld (2019), to train, validate, and test the proposed Physics-Enhanced Neural Network (PENN)-based predictive models. This dataset represents the largest publicly available compilation of CHF measurements, comprising 24,579 individual data points collected from 59 distinct experimental sources. Each entry corresponds to a CHF measurement obtained in a vertically oriented, water-cooled, uniformly heated tube subjected to varying experimental conditions. The majority of CHF values were identified using thermocouples positioned to detect rapid temperature excursions indicative of CHF onset. The dataset includes a comprehensive parameter space encompassing boundary conditions and geometric variables, as detailed in Table 3. Input features used for neural network modeling are categorized as follows: (i) geometric parameters (tube diameter D, heated length L); (ii) directly measured parameters (pressure P, mass flux G, inlet temperature Tin); and (iii) calculated parameters (outlet quality X, inlet subcooling Δhin), both calculated from water saturation properties. Although the NRC CHF dataset covers a wide and diverse range of the parameter space, it should be noted that the distribution of data points is not uniform across all variables. In particular, no data points exist for tube diameters greater than 16 mm. While the NRC dataset closely aligns with the database used in the development of the 2006 CHF LUT, all proprietary or non-public data have been excluded from the version used here (Groeneveld, 2019). Additionally, rigorous data preprocessing was undertaken to identify and eliminate non-physical entries, outliers, and duplicate records, as recommended in previous literature (Groeneveld, 2019; Groeneveld et al., 2007).

Table 3. Parameters range for the USNRC CHF dataset (Groeneveld, 2019).

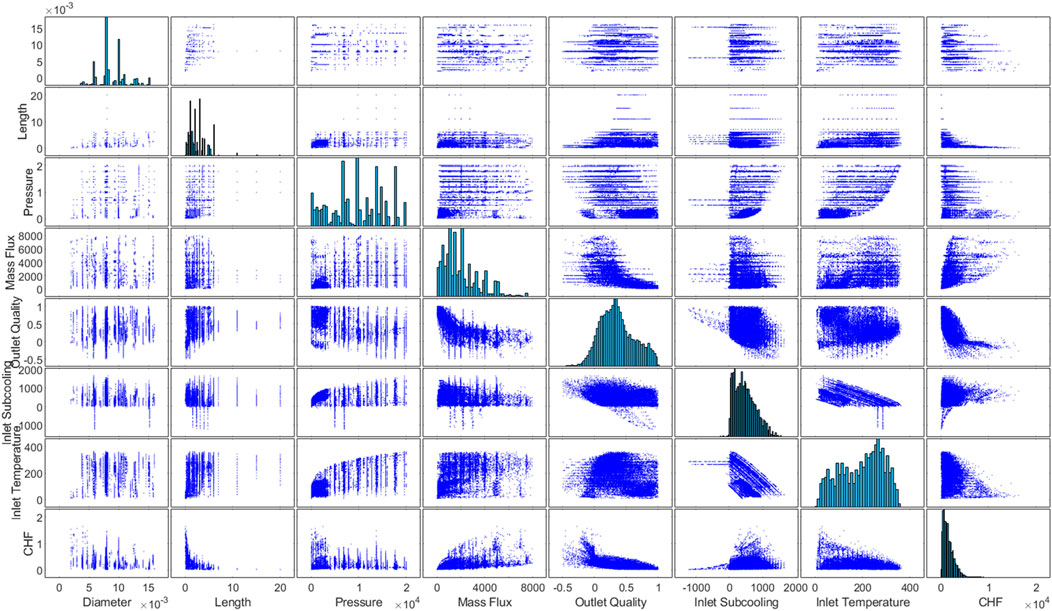

Figure 3 shows a scatter plot matrix of the NRC CHF dataset points to get an overview of the ranges with large amount of data availability (and thus providing higher reliability when modelled) and those lacking experimental points. Also, Figure 3 shows scatter plots highlighting the relationships between CHF and each input parameter. This allows for the evaluation of potential relationships between variables and the assessment of data distribution, as well as the study of possible input-output relationships. The CHF prediction can be made using all these input parameters (Ahmed et al., 2025) or, more often, by resorting to a properly selected subset. In this work, three different input sets are first considered to assess the predictive capability of a standalone (basic) NN model (Grosfilley et al., 2024): i)

Figure 3. Scatter plot matrix of the NRC CHF database (Groeneveld, 2019) showing the relationship between pairs of variables.

6 Results

In this section, the performances of the different PENNs models are assessed. In Section 6.1, the Res-PENNs and HLF-PENNs (based on both the LUT and the improved Liu models) are trained using the entire large NRC CHF dataset (24,579 points) and compared to purely data-driven NNs. In Section 6.2, the capability of PENNs to perform accurate and precise CHF predictions in the presence of very scarce data (e.g., a few tens or hundreds of training patterns) is systematically tested. Finally, in Section 6.3, the uncertainty associated with the CHF estimates provided by the standalone NNs and PENNs is estimated by bootstrapped ensembles and random weights reinitialization.

6.1 Performance of PENNs trained on the entire USNRC CHF dataset

The PENN performances are compared to the following references: i) the standalone empirical LUT (Section 4.1.1) and the improved mechanistic physics-based Liu (Section 4.1.2) models; and ii) purely data-driven ensemble NN models. The synthetic indicators described in Section 4.4 are summarized in Table 4 for the LUT and Liu models. As highlighted also in Zhao et al. (2020), the LUT performs in general slightly better than the Liu model: this is particularly evident with respect to the rMAPE, nRMSPE, Q2,

Table 4. Performance metrics (Section 4.4) calculated for the standalone empirical LUT (Groeneveld et al., 2007; Groeneveld, 2019) and the improved mechanistic physics-based Liu model (Liu et al., 2000; Liu et al., 2012) on the entire USNRC CHF dataset.

With respect to the NN regression models, in the present case study the number of inputs is equal to M = 5, whereas the number of outputs is equal to 1 (i.e., the CHF). The network structure, i.e., the number of hidden layers and the number of nodes in each hidden layer (see Table 5), has been optimally identified by grid search (Zio, 2006; Chicco, 2017): the interested reader is referred to (Castrignanò, 2025) for details, since the NN structure optimization does not represent the main purpose of the paper. It is only worth mentioning that for the regression task to be fair, as a rough guideline, each NN architecture is such that the overall number of internal weights and adjustable parameters does not exceed the number of patterns used to build the model (i.e., Nbuild = Ntrain

Table 5. Performance metrics (Section 4.4) obtained by purely data-driven NN ensembles (B = 100, S = 20) on the entire USNRC CHF dataset, in correspondence of three input sets

As mentioned above, three different input sets are first considered to assess the predictive capability of a standalone (basic) NN model (Grosfilley et al., 2024): i)

Even if using Tin or

Table 6. Performance metrics (Section 4.4) obtained by the Res-PENN ensembles (B = 100, S = 20) on the entire USNRC CHF dataset, using the empirical Groeneveld LUT and the improved Liu as domain knowledge- and mechanistic physics-based reference models, respectively, and input set

The situation is different for the HLF-PENN concept (Section 4.2.2), whose training is driven by a combination of data- and physics-based losses implemented directly in the NN error function through the weighting parameter

Figure 4. Sensitivity of the performance metrics rRMSPE, rMAPE and Q2 (Section 4.4) to parameter

6.2 Performance of PENNs trained with very small-sized datasets

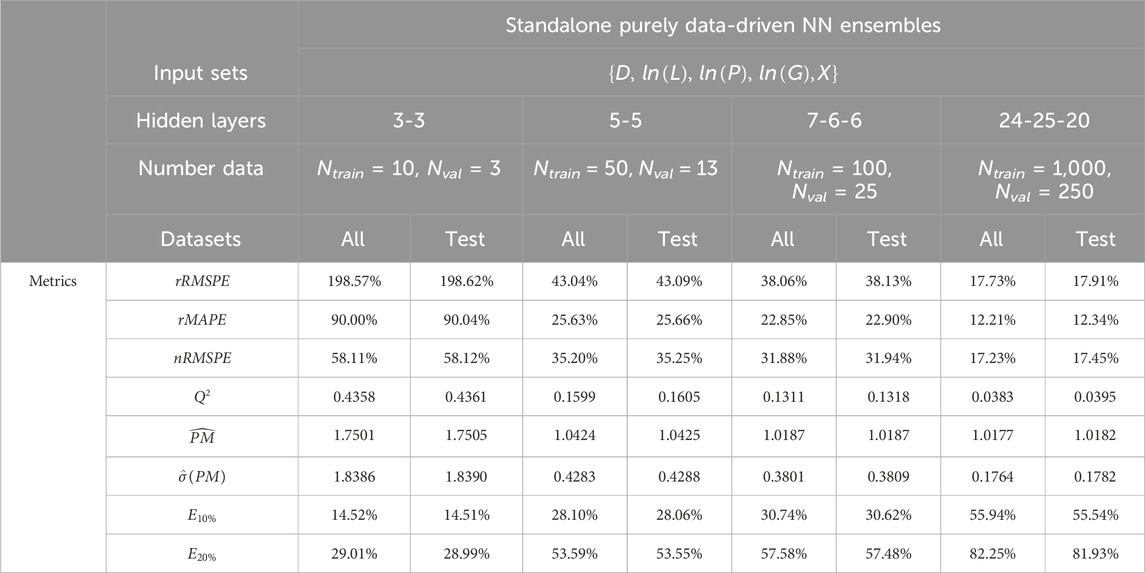

The predictive capabilities of NNs and PENNs are here tested in the presence of very small-sized datasets: this aspect is of paramount importance in the nuclear industry, where collecting a large amount of high-quality data is often too costly (and sometimes even impossible). In this respect, different small sizes of the training and validation sets are considered for building the NNs, i.e., Ntrain = 10, 50, 100, 1,000 and Nval = 3, 13, 25, 250, respectively (in practice, Nbuild = 13, 63, 125 and 1,250, respectively, in order to keep the same 80%–20% training-validation split ratio adopted in the previous tests of Section 6.1, for the sake of consistency). These small numbers of validation points combined with the early stopping procedure (based on the progress of the validation loss) may create some concern regarding instabilities of the training process, possibly leading to an early termination before adequate convergence (and also to overfitting). The non smooth evolution of the (training and validation) losses with respect to the learning epochs cannot be reported here due to space limitations. However, these detrimental effects have been significantly softened through the following strategies (it is observed that in general the training process is never stopped before 100–200 epochs, depending on the dataset size): (a) the overall number of internal weights and adjustable parameters has been carefully selected not exceed the number Nbuild of patterns used to build the model (see Tables 7, 8 and 9); (b) attention has been paid not to use training algorithms that converge too rapidly (such as the Levenberg-Marquardt one): to this aim, the scaled conjugate gradient backpropagation has been chosen; (c) the (bootstrap) ensemble learning (B) and NN model retraining (S) strategies adopted in this study are well known to satisfactorily cope with these issues and “absorb” possible training deficiencies (Zio, 2006); (d) extreme, badly trained models are discarded from the ensembles (see Section 4.3). In the future, to further reduce such convergence problems related to very small amount of data, other techniques could be employed instead of (or combined with) early stopping, such as L1/L2 regularization and dropout, which add a penalty to the model’s loss function or randomly drop neurons, respectively, to reduce complexity, stabilize the training process and prevent overfitting (Grosfilley et al., 2024; Furlong et al., 2025a). Also, in order to make the best use of the entire USNRC dataset, in each case the instances not included in the training and validation sets are employed to test the corresponding models, i.e., Ntest = Ndata–Nbuild = Ndata – (Ntrain + Nval) = 24,566, 24,516, 24,454 and 23,329, respectively. Table 7 shows the performance indicators (Section 4.4) for purely data-driven NN ensembles with input set

Table 7. Performance metrics (Section 4.4) obtained by purely data-driven NN ensembles (B = 100, S = 20) with inputs

Table 8. Performance metrics (Section 4.4) obtained by Res-PENN ensembles (B = 100, S = 20) relying on the empirical Groeneveld LUT and the improved Liu as domain knowledge- and mechanistic physics-based reference models, with inputs

Table 9. Performance metrics (Section 4.4) obtained by HLF-PENN ensembles (B = 100, S = 20) relying on the empirical Groeneveld LUT and the improved Liu as domain knowledge- and mechanistic physics-based reference models, with inputs

The results of Table 7 serve as reference comparison for the PENN architectures trained with the same amount of data. Table 8 reports the metrics (Section 4.4) obtained by Res-PENN ensembles relying on the empirical Groeneveld LUT and the improved Liu as domain knowledge- and mechanistic physics-based reference models, using small training sets of different sizes, i.e., Ntrain = 10, 50, 100 and 1,000. As before, the results are very interesting, since both Res-PENN ensembles significantly improve the performance obtained by the corresponding purely data-driven NN model using the same inputs (Table 7). For example, the corresponding percentage improvements obtained by the LUT-based Res-PENN range from 0.92% (

The HLF-PENN requires the identification of an optimal value for parameter

Figure 5. Sensitivity of the performance metrics rRMSPE, rMAPE and Q2 (Section 4.4) to parameter

Figure 6. Sensitivity of the performance metrics rRMSPE, rMAPE and Q2 (Section 4.4) to parameter

The behavior of the Liu-based HLF-PENN presents both similarities and interesting differences with respect to the LUT-based one. On one hand, the introduction of a “small amount” of physics (

Table 9 reports the metrics (Section 4.4) obtained by HLF-PENN ensembles relying on the empirical Groeneveld LUT and the improved Liu as domain knowledge- and mechanistic physics-based reference models, using very small training sets of different sizes, i.e., Ntrain = 10, 50 and 100, and the optimal values of

6.3 Uncertainty in the PENN predictions of the CHF

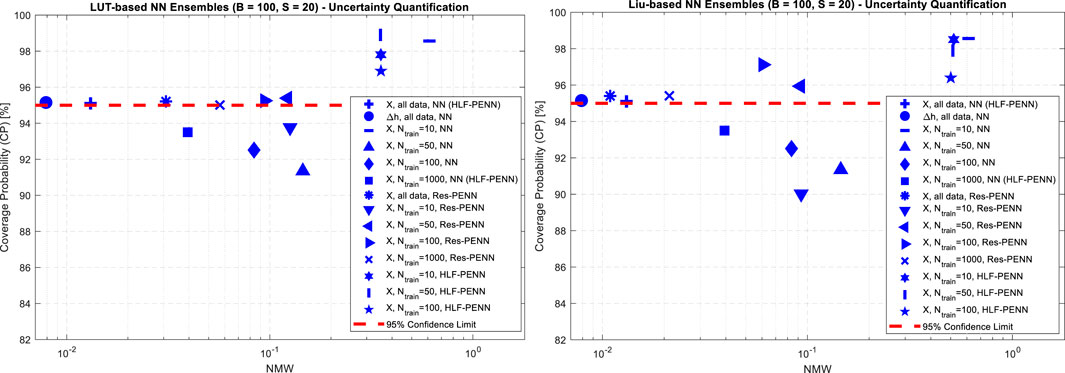

The uncertainty in CHF predictions (resulting from the finiteness of the training datasets, the randomness in the training process and model architecture) is quantified by 95% Prediction Intervals (PIs)

Figure 7. Coverage Probability (CP) and Normalized Mean Width (NMW) for the 95% Prediction Intervals (PIs) of the CHF predictions produced by all the NN- and PENN-based approaches here considered: (A) empirical LUT-based models (left); (B) mechanistic physics-based improved Liu model (right).

The uncertainty analyses of the PENN frameworks confirm to some extent the findings highlighted in the previous sections. When the Res-PENN approaches are adopted (asterisk, triangle-down, triangle-left, triangle-right, x-mark in Figure 7), the combination with the (worse performing) mechanistic physics-based Liu model produces more appreciable (i.e., less uncertain) results than the LUT: among the validated models, the corresponding NMWs (resp., the PIs) are 1.32–2.83 times smaller (resp., tighter). Instead, when the HLF-PENNs are embraced (hexagram, vertical line, pentagram in Figure 7), the best performances are obtained by hybridization with the (best performing) empirical LUT model: actually, the corresponding NMWs (resp., the PIs) are 1.42–1.47 times smaller (resp., tighter).

Finally, from the comparison of the general performance of classical NN, Res-PENN and HLF-PENN frameworks, it can be seen that: (i) for small- (Ntrain = 50–100) and moderate-sized (Ntrain = 1,000) datasets, PENNs are evidently preferable than classical NNs, as the CPs of their 95% PIs sre consistently larger than 95%, while most of the purely data-driven NN models are not validated; (ii) Res-PENN algorithms represent in general more convenient options than HLF-PENN ones, as their CHF estimates are much more precise (i.e., less uncertain): the corresponding NMWs are 3.0–24.5 times smaller; (iii) the HLF-PENN framework becomes an interesting option when the training set size is very small (Ntrain = 10–50), as it can produce validated models (differently from the other approaches); on the other hand, the associated uncertainty is typically overestimated, as it can be argued by the “excessive” values of the CPs (96.4%–98.9%, i.e., much larger than 95%) and by the comparatively large PIs (i.e., NMWs around 0.50–0.52).

7 Conclusion

In this paper, Residual- and Hybrid Loss Function-based Physics Enhanced Neural Networks (Res- and HLF-PENNs, respectively) using 5 input variables (pressure, hydraulic diameter, mass flux, heated length and critical quality) have been thoroughly and systematically compared in the tasks of accurately and precisely predicting the Critical Heat Flux (CHF) in nuclear reactors and of estimating the corresponding uncertainty. Two reference (prior) models have been considered for hybridization with NNs to produce PENN frameworks: the empirical (data-driven) Groeneveld Look-Up Table (LUT) (Groeneveld, 2019) and an improved version of the mechanistic physics-based Liu model (Liu et al., 2012). The main methodological and applicative contributions of the work can be summarized as follows:

⁃ While the HLF-PENN methodology has proven beneficial across a variety of physics domains, few or no applications to CHF prediction in nuclear reactors are available in the open literature up to now;

⁃ the improved Liu model proposed in Liu et al. (2012) has been considered for the first time within a PENN-based CHF prediction framework, as it covers a much wider range of thermodynamic conditions (i.e., both subcooled and saturated boiling) with respect to the original one (Liu et al., 2000; Zhao et al., 2020);

⁃ it was the first time that the Res-PENN and HLF-PENN approaches have been systematically compared, with particular reference to the task of estimating CHF in the presence of very scarce data (i.e., a few tens or hundreds training patterns), which is of paramount importance in the nuclear industry, where collecting a large amount of high-quality data is often too costly (and sometimes even impossible);

⁃ the uncertainty in the PENN predictions (due to the finiteness of the training dataset, randomness in the training process and model architecture) has been quantified by an ensemble-based approach, conceived as an original combination of two nested procedures involving the bootstrap method and a random weight/bias initialization strategy.

The application of the methods to the United States Nuclear Regulatory Commission (USNRC) CHF dataset from (Groeneveld, 2019) has allowed to derive the following guidelines and conclusions:

⁃ When very large datasets (i.e., containing >> 1,000 training patterns) are available:

o Classical, purely data-driven NNs can obtain excellent performances (e.g., rMAPE ≈ 2.58–7.73%) that are consistently superior to those of the standalone reference LUT and improved Liu models. More important, the results are at least comparable to (or even better than) those reported in the open literature and produced by more sophisticated algorithms (e.g., Convolutional Neural Networks-CNNs, Transformers, Ensembles of Deep Sparse AutoEncoders, …) employing a higher number of inputs and/or more complex structures and architectures (i.e., a much larger number of adjustable parameters);

o The very flexible Res-PENN framework can significantly improve the results obtained by purely data-driven NN models, showing performances that are almost independent of the embedded knowledge-based reference model (i.e., either LUT or Liu). Thanks to the availability of large data, the Res-PENN is very efficient in capturing and “absorbing” the associated model errors and biases, no matter the quality of the prior model;

o The HLF-PENN does not seem to represent the most convenient option, in particular when the (data- or physics-based) prior reference models “driving” the NN hybrid loss function are imperfect and show comparatively poor predictive capabilities with respect to purely data-driven ones (like in the present case), However, this conclusion (which seems to “limit” the effectiveness of HLF-PENNs in the presence of large data) has not been formally and analytically proven by the author, it may depend to some extent on the particular engineering problem at hand and, above all, on the particular task requested to the ML algorithm (i.e, , regression and/or interpolation and/or extrapolation), Thus, even in the presence of large datasets, quick testing and optimization of the weighting hyperparameter

⁃ When moderate-sized datasets (i.e., containing ≈1,000 training patterns) are available, the use of Res-PENN ensembles is strongly suggested, as they significantly improve the performance of purely data-driven NN models. However, as the number of data points decreases, the Res-PENN is shown to have an increasingly powerful action in situations where residuals/errors are more scattered or biased, i.e., when the reference (knowledge- or physics-based) model presents lower accuracy and precision (in this case, the improved Liu). Thus, a combination/hybridization with a poorly performing reference model is (paradoxically) preferable, as also found by Zhao et al. (2020).

⁃ Instead, when very small-sized datasets (i.e., containing ≈10–100 training patterns) are available, it becomes difficult even for the Res-PENN to capture effectively the undiscovered trends and absorb systematic model errors. Thus, the HLF-PENN framework starts to play an interesting role and may be taken as the preferable option, provided that: i) the weighting parameter

With respect to the quantification of uncertainty, it can be concluded that:

⁃ for small- (50–100 points) and moderate-sized (1,000 points) datasets, PENNs are evidently preferable than classical purely data-driven NNs, whose models are typically not validated from a statistical viewpoint;

⁃ Res-PENN algorithms represent in this case more convenient options than HLF-PENN ones, as their CHF estimates are much more precise (i.e., less uncertain);

⁃ the HLF-PENN framework becomes an interesting option only when the training set size is very small (10–50 points), as it can produce validated models (differently from the other approaches). On the other hand, their associated uncertainty is typically overestimated, as can be argued by the comparatively large width of the Prediction Intervals.

Future research will be devoted to: (i) testing the proposed PENN models on different datasets and possibly on different tube geometries; (ii) testing the PENNs extrapolation capabilities (i.e., predictions outside the training ranges): in this condition, HLF-PENNs are expected to play a relevant role, thanks to the presence of a reference prior model, which “emerges” in the hybrid loss function and compensates for the complete lack of experimental (training) data in the extrapolation range; (iii) creating Res-PENN and HLF-PENN algorithms based on the hybridization with new (possibly more accurate, more precise and less biased) empirical correlations and/or mechanistic physics-based models (when available, rigorous first-principle physical laws representing the “ground truth” for the phenomena of interest could be implemented): ideally, an ensemble of reference (prior) models could be considered, each one showing outstanding performances over a limited portion of the input space; (iv) comparing the ensemble-based strategy for uncertainty quantification with other approaches, e.g., dropout Neural Networks, Bayesian Neural Networks or In-series Neural Networks (Tran et al., 2020; Furlong et al., 2025a); (v) testing the PENN models on the “slice” datasets provided by the leaders of the “Task Force on Artificial Intelligence and Machine Learning for Scientific Computing in Nuclear Engineering” (i.e., datasets where only one input parameter at a time is allowed to vary within predefined intervals, while all the other parameters are kept reasonably constant). The objective is twofold: (a) although overfitting has been here carefully avoided by early stopping and accurate selection of the NN architecture and number of adjustable hyperparameters, this analysis will help demonstrating further the PENNs predictive and generalization capabilities; (b) visualizing how the uncertainty unfolds over the “slice” datasets will help checking if and how the PIs change expectedly in regions of data sparsity with respect to those of high data density.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author contributions

NP: Writing – original draft, Software, Resources, Visualization, Methodology, Formal Analysis, Conceptualization, Validation, Data curation, Writing – review and editing, Investigation.

Funding

The authors declare that no financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article.

Acknowledgements

The author would like to acknowledge the contribution of all those individuals who had a key role and leadership in the conduct of the activity of the OECD/NEA/WPRS/EGMUP “Task Force on Artificial Intelligence and Machine Learning for Scientific Computing in Nuclear Engineering”, especially the task leaders: Jean-Marie LE CORRE (Westinghouse Electric Sweden AB, Sweden), Gregory DELIPEI (North Carolina State University, United States), Xu WU (North Carolina State University, United States), Xingang ZHAO (Oak Ridge National Laboratory, United States), Oliver BUSS (NEA).

Conflict of interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

The author(s) declared that they were an editorial board member of Frontiers, at the time of submission. This had no impact on the peer review process and the final decision.

Generative AI statement

The authors declare that no Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.