- 1Eye Clinic, Department of Neurosciences, Reproductive and Odontostomatological Sciences, University of Naples Federico II, Naples, Italy

- 2Department of Clinical Medicine and Surgery, University of Naples Federico II, Naples, Italy

- 3Division of Pathology, Department of Advanced Biomedical Sciences, University of Naples Federico II, Naples, Italy

- 4Department of Medicine and Health Sciences “V. Tiberio”, University of Molise, Campobasso, Italy

- 5Department of Advanced Biomedical Sciences, University of Naples Federico II, Naples, Italy

- 6Division of Neurosurgery, Department of Neurosciences, Reproductive and Odontostomatological Sciences, University of Naples Federico II, Naples, Italy

Background: Merkel cell carcinoma (MCC) of the eyelid is rare and aggressive. Diagnostic delay and inadequate excision may promote early nodal spread. We assessed the influence of surgical margins and re-excision timing on outcomes, supported by a PRISMA-guided systematic review on metastatic risk.

Methods: A single-center retrospective series (2012–2024) included 9 histologically confirmed eyelid MCCs, analyzing presentation, treatment, and outcomes. Surgical strategies were classified as one-step wide local excision (1WLE, ≥5 mm), two-step wide local excision (2WLE) with early (E2WLE, ≤2 months) or late (L2WLE, 6 months) re-excision, and insufficient margin excision (IME, <2 mm without re-excision). A systematic review identified periocular MCC cases with individual-level data on margins and outcomes.

Results: Patients (median age 71.8 years, range 42–92; 89% female) all presented with solitary nodules on the upper eyelid, and were node-negative and metastasis-free at diagnosis, consistent with AJCC 8th clinical stage I–IIA.Median follow-up was 48 months (IQR 12–120). Treatments included 1WLE (n=4), 2WLE (n=3; 2 E2WLE, 1 L2WLE), and IME (n=2). Three patients (33%) developed cervical lymph node metastases within 1–3 months: one after L2WLE (fatal at 12 months) and two after IME. Both IME patients showed marked responses to Avelumab. Of the remaining six, four (67%) remained disease-free and two (33%) died of unrelated causes. Metastatic risk was significantly higher after IME versus sufficient margins (p=0.0119). In the PRISMA-guided review (76 eyelid MCC), insufficient margins correlated with adverse outcomes; in a subset without baseline metastasis (n=39), insufficient margins increased risk of recurrence/metastasis (OR 10.56; 95% CI 1.84–77.24; Fisher’s exact p=0.002).

Conclusion: In eyelid MCC, adequate margins at first surgery or early re-excision are crucial to prevent early nodal spread. Our findings emphasize the prognostic value of surgical adequacy and support incorporating wide excision into initial management. Further multicenter studies are warranted to define evidence-based management pathways, improve long-term outcomes, and clarify the role of checkpoint inhibition in periocular MCC.

1 Introduction

Merkel cells were first described by Friedrich Merkel in 1875 as clear, large, round cells in the basal epidermis (1). A century later, Toker et al. reported a rare, aggressive neuroendocrine skin cancer, now called Merkel cell carcinoma (MCC) (1). Although eponymously linked to Merkel cells, the tumor’s cell of origin remains debated: the B-cell theory is supported by B-cell marker expression in a subset of tumors (2), whereas the coexistence of MCC with squamous cell carcinoma favors an epithelial precursor in some cases (3). Most investigators thus consider mature Merkel cells an unlikely universal source (4).

MCC is uncommon and its incidence varies by geography. In the EU, the annual incidence was ~0.13/100,000 in 1995–2002 (5); in the United States, it is ~0.7/100,000 (6). Most lesions arise on chronically ultraviolet (UV)-exposed site; about 42.6% occur on the head/neck (6), and 2.5–10% involve the eyelid (5, 6). Recognized risk factors include advanced age, Caucasian ethnicity, cumulative UV exposure, and immunosuppression (e.g., HIV, transplant) (5, 6). In 2008, Feng et al. identified Merkel cell polyomavirus (MCPyV) clonally integrated in MCC (7), a finding replicated in ~80% of tumors and consistent with a key etiologic role (8). This viral vs UV-driven dichotomy carries clinical and biological implications: MCPyV-positive tumors may elicit antigen-specific immunity and can aberrantly express PD-L1, with potential relevance for immune checkpoint inhibition (9, 10). Clinically, periocular MCC often presents on the upper eyelid, near the margin, sometimes with madarosis, and is frequently misdiagnosed as chalazion/cyst or basal cell carcinoma (5, 11–14). Typical lesions are painless, rapidly enlarging, violaceous-red nodules, aligning with the AEIOU features (Asymptomatic, Expanding rapidly ≤3 months, Immunosuppressed, Older >50, UV-exposed site) (11, 15). Histopathology shows a poorly differentiated neuroendocrine carcinoma expressing cytokeratins (AE1/3, CAM5.2, CK20) and neuroendocrine markers (synaptophysin, chromogranin, NSE) (11, 12). A key differential is small-cell lung carcinoma: MCC is typically cytokeratin 20 (CK20)-positive and thyroid transcription factor-1 (TTF-1)-negative, whereas SCLC frequently expresses TTF-1 (12, 16).

Multiple staging systems have been used historically; contemporary series use AJCC TNM staging for eyelid carcinoma (17). Eyelid MCC appears to have more favorable local control and lower distant relapse than extra-ocular MCC when managed within specialized centers (17–19). Surgery with attention to margin adequacy and adjuvant radiotherapy forms the cornerstone of localized disease management (18). While 1–2 cm margins are standard for extra-facial MCC (19), Peters et al. reported effective local control of eyelid MCC with 5-mm margins, consistent with practices for other aggressive eyelid malignancies (20). For advanced or unresectable disease, immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICI) have demonstrated promising activity (21–23); Avelumab became the first FDA-approved therapy for MCC in 2017 (24), supporting further evaluation in periocular presentations where prospective data are still limited (21–24).

The aim of this study is to describe presentation, management, and outcomes of eyelid MCC in a tertiary center and to test the association between initial margin adequacy (≥5 mm vs <5 mm without timely re-excision) and metastasis/recurrence, and to examine whether initial margin adequacy predicts metastasis/recurrence in our cohort and in a contemporaneous systematic evidence synthesis.

2 Methods

2.1 Patients and study design

A non-comparative, retrospective case series was conducted at a single tertiary referral center from January 2012 to January 2024. Nine patients with Merkel cell carcinoma (MCC) of the eyelid were identified through institutional medical records, and data were collected retrospectively. All patients had a confirmed diagnosis with pathology results.

Inclusion criteria were: (1) confirmed diagnosis of MCC by immunohistochemistry, (2) primary localization of the tumor to the eyelid, (3) managed at our institution during the study period with complete baseline clinicopathologic data, and (4) availability of complete clinical records with a minimum follow-up of one year. Exclusion criteria included (1) eyelid involvement due to regional/distant metastasis from an MCC primary outside the periocular region, (2) absence of definitive histopathological confirmation, (3) prior definitive treatment elsewhere with undocumented details that prevent outcome attribution, (4) collision tumors where the MCC component cannot be analyzed independently, and (5) incomplete clinical records or insufficient follow-up information.

For each patient, the following data were collected: age at diagnosis, sex, initial presenting symptoms, anatomical origin of the lesion, presence of regional or distant metastases at diagnosis, type of primary treatment administered (surgical excision, adjuvant radiotherapy, and/or chemotherapy), margin status, recurrence (local or regional), development of distant metastases during follow-up, duration of follow-up, and overall survival. At diagnosis, all patients underwent regional examination and high-resolution lymph-node ultrasound (preauricular, parotid, levels I–V). Contrast-enhanced head–neck CT was obtained in all cases. Whole-body PET/CT was performed in patients with suspicious US/CT. Sentinel lymph node biopsy (SLNB) was not performed at the baseline as no regional or distant metastases were detected at presentation. Clinical staging was assigned according to the TNM staging system for Merkel cell carcinoma, AJCC Cancer Staging Manual, 8th Edition.

All surgical decisions were taken in a multidisciplinary setting (oculoplastic oncology, dermatopathology, radiation oncology), balancing oncologic control with eyelid function and reconstruction. Resections were planned as wide local excisions (WLE) with a predefined margin policy adapted to periocular anatomy. Our unit targets ≥5 mm gross margins. When anatomy or reconstruction constraints preclude this at first pass, we perform a planned two-step WLE: an initial diagnostic/excisional pass to remove the tumor with clear but <5 mm microscopic margins, followed by early re-excision (≤8 weeks) to extend margins to ≥5 mm once histology confirms MCC and reconstructive planning is optimized (E2WLE). Margin were defined sufficient as histologic tumor-free margins ≥5 mm, and insufficient in case of insufficient margin excision (IME) <5 mm.

The study adhered to the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Ethics Committee of the University of Naples Federico II. Owing to its retrospective design and use of anonymized data, the requirement for individual informed consent was waived. For any images or data with potential identifiability, specific written consent for publication was obtained. Systematic Review.

This systematic review was conducted in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines (25). Studies were considered eligible if they involved patients diagnosed with Merkel cell carcinoma. Given the rarity of long-term follow-up data in this population, no minimum follow-up duration was required for inclusion.

The inclusion criteria were (1) human patients with eyelid/periocular MCC, (2) Observational studies (prospective/retrospective cohorts, case–control, case series ≥3 cases, and single case reports) when they specifically report periocular MCC with clinical course/outcome, (3) histopathological confirmation with immunohistochemistry consistent with MCC, (4) any of the following—local/regional recurrence, nodal status and management (SLNB/therapeutic dissection), distant metastasis, margin status, adjuvant therapy (RT/systemic), disease-specific survival, overall survival, complications, (5) publications from January 2011 to December 2024, (6) English language, (7) any type of settings (single-center, multicenter, registry).

Exclusion criteria included (1) secondary analyses without primary patient-level data (e.g., reviews, meta-analyses, editorials, letters, technical notes), (2) abstract-only publications (conference abstracts/posters) without full data, (3) non-human, in vitro, or non-clinical studies, (4) studies with unconfirmed MCC diagnosis or insufficient immunophenotypic confirmation, (5) studies on non-periocular MCC without extractable periocular subgroup data, (6) duplicate/overlapping cohorts: when multiple publications reported the same or overlapping populations, we retained the most comprehensive dataset (largest sample and/or longest follow-up) or contacted authors when necessary.

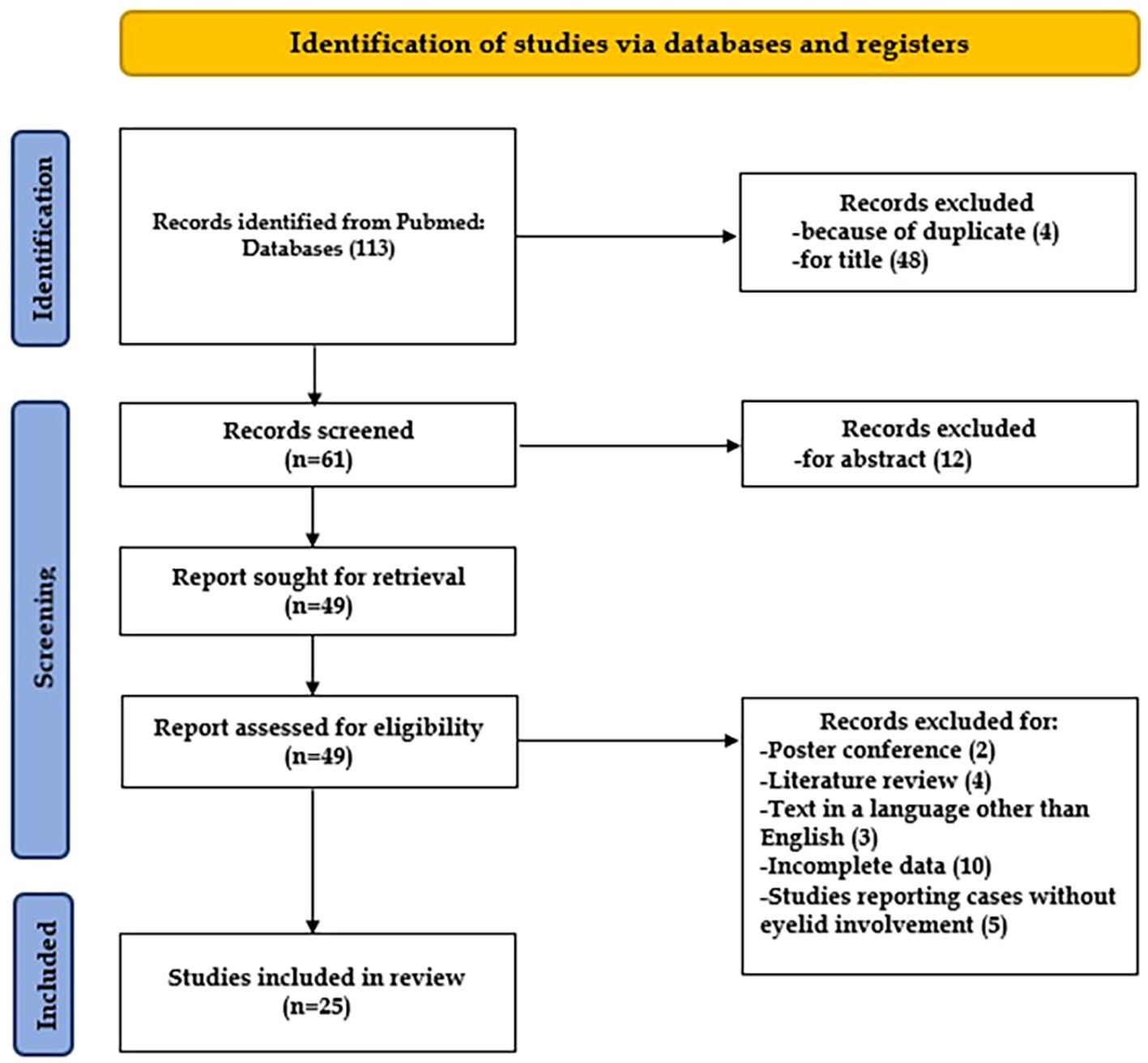

A comprehensive literature search was performed using the Medline database, from January 2011 to December 2024. The following keywords and phrases were used in various combinations: “Merkel cell carcinoma,” “Primary cutaneous neuroendocrine carcinoma,” “Merkel carcinoma,” “eyelid,” and “head and neck.” A total of 113 records were identified through PubMed, and after screening and exclusion, 25 studies met the inclusion criteria and were included in the systematic review (8, 14, 26–48).

From each included study, the following data were extracted: first author and year of publication, number of patients, sex, age, presenting symptoms, anatomical site of the tumor, clinical stage, treatment approach, and clinical outcome. An initial descriptive analysis was conducted. Additionally, we extracted data from studies reporting individual-level details on Merkel cell carcinoma patients treated surgically, where tumor size, resection margin status, and clinical outcomes were clearly documented.

2.2 Statistical analysis

To investigate the potential association between surgical margin status and clinical outcomes, a statistical analysis was performed on the subset of patients for whom both variables were available. Patients were grouped based on resection margin status (sufficient vs. insufficient), and their outcomes were categorized as either positive (no recurrence or metastasis) or negative (recurrence and/or metastasis). The association between margin status and clinical outcome was assessed using Fisher’s exact test, and the strength of association was estimated by calculating the odds ratio (OR) with a 95% confidence interval. A p-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

3 Results

A total of nine patients with histologically confirmed Merkel cell carcinoma (MCC) of the eyelid were identified from our institutional database. The median age at diagnosis was 71.8 years (range: 42–92), and the majority were female (n = 8, 88.9%). All patients presented with a single nodular lesion (n = 9, 100%) located on the upper eyelid (n = 9, 100%). At diagnosis—ultrasound and contrast-enhanced CT, with PET/CT when indicated—revealed no regional or distant metastases. Per AJCC 8th edition (clinical staging), three patients had Stage I disease and six had Stage IIA.

Individual data at presentation are detailed in Table 1. The median follow-up period was 48 months (IQR: 12–120).

Table 1. Demographic, clinical, radiologic, treatment, and outcome data for 9 patients with eyelid Merkel cell carcinoma managed at the Oculoplastic Unit, University of Naples Federico II (January 2012–December 2024).

Surgical excision was performed in all cases.

Four patients underwent one-step complete excision (1WLE) with margins ≥5 mm. Two patients (22%) underwent early (within 2 months) two-step wide local excision (E2WLE) with initial clear margins but less than 5 mm. One patient initially underwent partial excision elsewhere with close/positive margins and was referred to our unit. At ~6 months, we performed second-stage WLE (L2WLE) achieving ≥5 mm microscopic margins circumferentially (deep margin to 6.5mm), followed by skin graft. Two patients underwent initial local resection with clinical margins smaller than 2 mm but were unable to undergo a 2-step WLE re-excision (IME);. Three patients (33.3%) developed cervical lymph node metastasis (stage III), during a follow-up period ranging from 1 month to 3 month with one patient in the L2WLE margin group and two in the IME group. The patient with L2WLE developed distant metastases to the parotid gland and liver and succumbed to the disease approximately 12 months after diagnosis. Both patients in the IME group with metastatic disease were treated with Avelumab, exhibiting a remarkable response.

One of the two patients of the IME group had local recurrence and lymph node metastasis (14.3% of the cohort) within one month from the initial excision. Due to the patient’s age (92 years) and comorbidities, systemic therapy with Avelumab was initiated, resulting in regression of the lesion. The other metastatic patient of the IME group developed lateral cervical lymph node involvement approximately two months after surgery; the board recommended to commence the patient with Avelumab instead of proceeding with the second step wide excision, being the disease already disseminated. The patient responded to Avelumab with remarkable regression of the lymph node metastasis, which has been observed during 8-month follow-up.

Of the remaining patients, four (57.1%) were alive without disease, and two (28.6%) had died from unrelated causes, free of disease until they passed away. A comparison of clinical outcomes between patients with initially sufficient versus insufficient surgical margins revealed a statistically significant difference in terms of metastatic disease (p-value = 0.0119). Clinical presentation and postoperative appearance of three representative cases of eyelid Merkel cell carcinoma are reported in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Case 1 presurgery (1A) and postsurgery (1B); case 2 presurgery (2A) and postsurgery (2B); case 3 presurgery (3A) and postsurgery (3B).

3.1 Literature review

After screening a total of 113 articles, 25 met the predefined inclusion criteria and were included in the final review, as illustrated in Figure 2. Overall, the review comprised 76 patients diagnosed with Merkel cell carcinoma (MCC) of the eyelid.

Figure 2. Flow chart showing the methods for the selection of the studies included in the review, following PRISMA (25).

Data on patient sex were available for 75 out of 76 individuals (98.7%). Among them, 46 were female (61.3%) and 29 were male (38.7%). Presenting symptoms were reported in 94.7% of cases (n = 72/76), with the most common manifestation being a “single nodular lesion” (n = 60/72, 83.3%). Less typical presentations included “chalazion,” “single ulcerated lesion,” “tan cystic lesion,” or “multiple conjunctival nodules” (n = 12/72, 16.7%).

The anatomical origin of the tumor was reported for all patients. The most frequently involved site was the upper eyelid (n = 57/76, 75.0%), followed by the lower eyelid (n = 18/76, 23.7%). Metastatic disease at diagnosis was observed in 11 cases (14.5%), while the remaining 65 patients (85.5%) presented with localized tumors.

Full details of the included cases are summarized in Table 2.

Table 2. Demographic, clinical, and radiological characteristics of 76 eyelid Merkel cell carcinoma cases from a systematic review of the literature.

For the subset analysis—restricted to surgically treated patients with individual-level staging data—we excluded all cases with lymph-node involvement or distant metastasis at diagnosis to avoid immortal-time bias and reduce stage-related confounding, thereby isolating the potential association between surgical margin status and oncologic outcome. A total of 16 studies (39 patients) were included in this subgroup. The mean age was 74 years (SD 13), and the majority were female (49%), while 23% were male, and 28% had missing data on sex. Regarding clinical stage, 77% were stage I, and 23% were stage II. Margins were classified as sufficient in 69% of cases and insufficient in 31%. Adjuvant radiotherapy was administered in 53% of cases, and adjuvant chemotherapy in 5.3%. With regard to clinical outcomes, 69% of patients had a favorable course with no evidence of metastasis, whereas 31% developed metastatic disease during follow-up. Details are summarized in Table 3.

Table 3. Treatments and outcomes for 76 eyelid Merkel cell carcinoma cases from a systematic review of the literature.

Among patients with available data on surgical margins and clinical outcome, we observed a statistically significant association between insufficient resection margins and negative clinical outcome. Specifically, patients with insufficient margins had a substantially higher risk of developing metastasis or recurrence compared to those with sufficient margins (Fisher’s exact test, p = 0.002). The odds ratio was 10.56 (95% CI: 1.84–77.24), indicating that the likelihood of a negative outcome was approximately ten times greater in patients with insufficient margins, regardless of tumor-size and T-stage.

4 Discussion

Our patient cohort exhibited a pronounced female predominance (8/9, 88.9%) and a mean age at diagnosis of 71.8 years, which aligns closely with the findings of our literature review (67.9% female among cases with known sex; mean age 74 years). Notably, all cases in our cohort involved the upper eyelid (9/9, 100%), consistent with published reports where 75% of lesions (57/76) were localized to this region. In contrast to the reviewed studies, where 14.5% (11/76) of patients presented with regional or distant metastasis at diagnosis, none of our patients exhibited metastatic disease at initial presentation.

The local recurrence rate in our cohort was 14.3% (1/7), mirroring the rate reported in the literature (14.9%, 11/74). Similarly, the proportion of patients who developed distant metastases (28.6%) was comparable to that observed in published reports (31.0%).

One of the primary challenges in managing Merkel cell carcinoma (MCC) of the eyelid is the frequent underestimation of the initial diagnosis. Given its rarity, MCC is often misdiagnosed as more common benign conditions, which can lead to delayed treatment and poorer outcomes. This challenge is well-documented in the literature (49), emphasizing the need for early recognition and appropriate surgical management to improve patient outcomes. In our cohort, one case had a partial resection of the lesion performed elsewhere due to an initial misdiagnosis of chalazion, which ultimately proved to be the only case that succumbed to the disease.

Clinical experience and data from the literature review underscore the importance of achieving adequate surgical margins (≥5 mm of free margin) during initial surgery to minimize the risk of local recurrence. Unlike many cases reported in the literature, where MCC of the eyelid is often misdiagnosed, leading to inadequate initial excision, all of our patients underwent immediate excisional biopsy at first presentation, except for one case. When clinical margins were <5 mm (4/9, 44.4%), surgical wide re-excision was promptly performed within two months in most cases. In our cohort, outcomes differed significantly by initial margin status: metastatic events were more frequent after insufficient versus sufficient margins (p = 0.0119). This pattern mirrors our PRISMA-guided systematic review, where insufficient margins were strongly associated with adverse outcomes (OR = 10.56; 95% CI, 1.84–77.24; p = 0.002). Notably, timely conversion to wide margins in our series appears to mitigate risk, reinforcing the concept that surgical timing is critical in eyelid MCC management (50, 51).

From a clinical perspective, our findings highlight the importance of considering MCC in the differential diagnosis of eyelid masses. The systematic adoption of diagnostic criteria such as the AEIOU acronym (asymptomatic/lack of tenderness, expanding rapidly, immune suppression, older than 50 years, and ultraviolet-exposed site on a person with fair skin) can facilitate early diagnostic suspicion. When clinical suspicion for MCC is high—based on AEIOU features such as rapid growth, lack of tenderness, and lash loss—a excisional biopsy with an early re-excision if needed is preferred over small incisional biopsy, minimizing tumor manipulation and expediting definitive margins. Furthermore, it is crucial to educate ophthalmic surgeons and dermatologists about the importance of ensuring adequate surgical margins during the initial excision, even when the definitive diagnosis has not yet been confirmed by histopathological examination.

Although Ki-67 quantification was not available for all patients, those who developed distant metastases had values exceeding 90%, whereas patients who remained disease-free had lower Ki-67 values. This suggests that Ki-67 may serve as a prognostic biomarker and inform decisions regarding adjuvant therapies. Further studies are needed to validate its role in clinical practice.

Notably, our most recent two patients received adjuvant Avelumab following early metastatic recurrence, and both demonstrated tumor regression and were alive after 8 months of follow-up. Although these observations align with published evidence supporting immune checkpoint inhibition in Merkel cell carcinoma, our small retrospective series cannot provide any conclusions regarding treatment efficacy. The therapeutic role of ICIs lies beyond the scope of this study, and definitive assessment requires larger, prospective oncologic datasets. Case reports have also described MCC arising de novo during PD-1 blockade, indicating that immunotherapy does not eliminate the risk of new primary tumors and that vigilant periocular surveillance remains essential (52). Overall, while ICIs have transformed systemic MCC management when surgery or radiation are constrained by function or stage (53), our findings do not allow disease-directed therapeutic recommendations. This study has several limitations, including the single-center cohort small sample size (n = 9), the retrospective nature, and incomplete data points, limited power for stage-adjusted analyses, possible selection bias in surgical strategy, and heterogeneity of adjuvant regimens. These constraints preclude causal inference and render our margin–outcome comparisons hypothesis-generating Despite these limitations, our findings emphasize the critical importance of early and well-coordinated surgical management in eyelid MCC (50, 51). Achieving adequate excision margins, either at the time of diagnosis or through timely re-excision, appears to be essential in minimizing the risk of recurrence and progression. Further multicenter studies are warranted to develop robust, evidence-based management guidelines and improve long-term patient outcomes, and clarify the role of checkpoint inhibition in periocular MCC.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by Ethics Committee of the University of Naples Federico II. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. Written informed consent for participation in this study was provided by the participants’ legal guardians/next of kin. Written informed consent was obtained from the individual(s) for the publication of any potentially identifiable images or data included in this article.

Author contributions

DS: Conceptualization, Validation, Methodology, Supervision, Writing – original draft, Project administration, Writing – review & editing. CB: Data curation, Investigation, Writing – original draft. MT: Writing – original draft, Validation, Data curation. VL: Investigation, Writing – review & editing. VD: Writing – review & editing. RD: Writing – review & editing. MP: Validation, Writing – original draft. AD: Validation, Writing – review & editing. RN: Writing – review & editing, Investigation. MC: Writing – review & editing. DC: Writing – review & editing. GM: Writing – review & editing. CC: Writing – review & editing, Supervision. AI: Methodology, Validation, Supervision, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declared financial support was not received for this work and/or its publication.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared that this work was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

The author DS declared that they were an editorial board member of Frontiers, at the time of submission. This had no impact on the peer review process and the final decision.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that Generative AI was not used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1. Bickle K, Glass LF, Messina JL, Fenske NA, and Siegrist K. Merkel cell carcinoma: a clinical, histopathologic and immunohistochemical review. Semin Cutan Med Surg. (2004) 23:46–53.

2. Pietropaolo V, Prezioso C, and Moens U. Merkel cell polyomavirus and Merkel cell carcinoma. Cancers (Basel). (2020) 12:1774. doi: 10.3390/cancers12071774

3. Walsh NM. Primary neuroendocrine cell (Merkel cell) carcinoma of the skin: Morphological diversity and implications thereof. Hum Pathol. (2001) 32:680–9. doi: 10.1053/hupa.2001.25904

4. Harms PW, Harms KL, Moore PS, DeCaprio JA, Nghiem P, Wong MK, et al. The biology and treatment of Merkel cell carcinoma: Current understanding and research priorities. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. (2018) 15:763–76. doi: 10.1038/s41571-018-0103-2

5. Siqueira SOM, Campos-do-Carmo G, Dos Santos ALS, Martins C, and de Melo AC. Merkel cell carcinoma: epidemiology, clinical features, diagnosis and treatment of a rare disease. An Bras Dermatol. (2023) 98:277–86. doi: 10.1016/j.abd.2022.09.003

6. Strong J, Hallaert P, and Brownell I. Merkel cell carcinoma. Hematol. Oncol. Clin North Am. (2024) 38:1133–47. doi: 10.1016/j.hoc.2024.05.013

7. Feng H, Shuda M, Chang Y, and Moore PS. Clonal integration of a polyomavirus in human Merkel cell carcinoma. Science. (2008) 319:1096–100. doi: 10.1126/science.1152586

8. Komatsu H, Usui Y, Sukeda A, Yamamoto Y, Ohno SI, Goto K, et al. Prevalence of Merkel cell polyomavirus in primary eyelid Merkel cell carcinomas and association with clinicopathological features. Am J Ophthalmol. (2023) 249:49–56. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2022.12.001

9. Dong H, Strome SE, Salomao DR, Tamura H, Hirano F, Flies DB, et al. Tumor-associated B7-H1 promotes T-cell apoptosis: A potential mechanism of immune evasion. Nat Med. (2002) 8:793–800. doi: 10.1038/nm730

10. Lipson EJ, Vincent JG, Loyo M, Kagohara LT, Luber BS, Wang H, et al. PD-L1 expression in the Merkel cell carcinoma microenvironment: Association with inflammation, Merkel cell polyomavirus and overall survival. Cancer Immunol Res. (2013) 1:54–63. doi: 10.1158/2326-6066.CIR-13-0034

11. Merritt H, Sniegowski MC, and Esmaeli B. Merkel cell carcinoma of the eyelid and periocular region. Cancers (Basel). (2014) 6:1128–37. doi: 10.3390/cancers6021128

12. Cheuk W, Kwan MY, Suster S, and Chan JK. Immunostaining for thyroid transcription factor 1 and cytokeratin 20 aids the distinction of small cell carcinoma from Merkel cell carcinoma, but not pulmonary from extrapulmonary small cell carcinomas. Arch Pathol Lab Med. (2001) 125:228–31. doi: 10.5858/2001-125-0228-IFTTFA

13. Dong HY, Liu W, Cohen P, Mahle CE, and Zhang W. B-cell specific activation protein encoded by the PAX-5 gene is commonly expressed in Merkel cell carcinoma and small cell carcinomas. Am J Surg Pathol. (2005) 29:687–92. doi: 10.1097/01.pas.0000155162.33044.4f

14. Herbert HM, Sun MT, Selva D, Fernando B, Saleh GM, Beaconsfield M, et al. Merkel cell carcinoma of the eyelid: management and prognosis. JAMA Ophthalmol. (2014) 132:197–204. doi: 10.1001/jamaophthalmol.2013.6077

15. Heath M, Jaimes N, Lemos B, Mostaghimi A, Wang LC, Peñas PF, et al. Clinical characteristics of Merkel cell carcinoma at diagnosis in 195 patients: the AEIOU features. J Am Acad Dermatol. (2008) 58:375–81. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2007.11.020

16. Czapiewski P and Biernat W. Merkel cell carcinoma—recent advances in the biology, diagnostics and treatment. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. (2014) 53:536–46. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2014.04.023

17. Trinidad CM, Torres-Cabala CA, Prieto VG, and Aung PP. Update on eighth edition American Joint Committee on Cancer classification for Merkel cell carcinoma and histopathological parameters that determine prognosis. J Clin Pathol. (2019) 72:337–40. doi: 10.1136/jclinpath-2018-205504

18. Walsh NM. Merkel cell carcinoma of the eyelid and periocular region: A review. Saudi J Ophthalmol. (2022) 35:186–92. doi: 10.4103/SJOPT.SJOPT_55_21

19. Andruska N, Fischer-Valuck BW, Mahapatra L, Brenneman RJ, Gay HA, Thorstad WL, et al. Association between surgical margins larger than 1 cm and overall survival in patients with Merkel cell carcinoma. JAMA Dermatol. (2021) 157:540–8. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2021.0247

20. Peters GB 3rd, Meyer DR, Shields JA, Custer PL, Rubin PA, Wojno TH, et al. Management and prognosis of Merkel cell carcinoma of the eyelid. Ophthalmology. (2001) 108:1575–9. doi: 10.1016/S0161-6420(01)00701-1

21. Zhan S, Nguyen M, and Hollsten J. Immune checkpoint inhibition therapy as first-line treatment for localized eyelid Merkel cell carcinoma in a nonsurgical candidate. Can J Ophthalmol. (2024) 59:e183–4. doi: 10.1016/j.jcjo.2023.10.019

22. Nghiem PT, Bhatia S, Lipson EJ, KudChadkar RR, Miller NJ, Annamalai L, et al. PD-1 blockade with pembrolizumab in advanced Merkel-cell carcinoma. N Engl J Med. (2016) 374:2542–52. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1603702

23. Kaufman HL, Russell J, Hamid O, Bhatia S, Terheyden P, D’Angelo SP, et al. Avelumab in patients with chemotherapy-refractory metastatic Merkel cell carcinoma: A multicentre, single-group, open-label, phase 2 trial. Lancet Oncol. (2016) 17:1374–85. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(16)30364-3

24. Garcia GA and Kossler AL. Avelumab as an emerging therapy for eyelid and periocular Merkel cell carcinoma. Int Ophthalmol Clin. (2020) 60:91–102. doi: 10.1097/IIO.0000000000000306

25. Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ. (2021) 372:n71. doi: 10.1186/s13643-021-01626-4

26. Sugamata A, Goya K, and Yoshizawa N. A case of complete spontaneous regression of extremely advanced Merkel cell carcinoma. J Surg Case Rep. (2011) 2011:7. doi: 10.1093/jscr/2011.10.7

27. Santos AL, Magno Pereira V, Coelho R, Gaspar R, Cardoso H, Lopes J, et al. A rare cause of acute liver failure: diffuse liver metastization of Merkel cell carcinoma. GE Port J Gastroenterol. (2020) 27:203–6. doi: 10.1159/000503150

28. Boileau M, Dubois M, Abi Rached H, Escande A, Mirabel X, and Mortier L. An effective primary treatment using radiotherapy in patients with eyelid Merkel cell carcinoma. Curr Oncol. (2023) 30:6353–61. doi: 10.3390/curroncol30070468

29. Feng Y, Song X, and Jia R. Favorable response to the tyrosine kinase inhibitor apatinib in recurrent Merkel cell carcinoma: case report. Front Oncol. (2021) 11:625360. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2021.625360

30. Bostan C, de Souza MBD, Zoroquiain P, de Souza LAG, and Burnier MN Jr. Case series: Merkel cell carcinoma of the eyelid. Can J Ophthalmol. (2017) 52:e182–5. doi: 10.1016/j.jcjo.2017.03.009

31. Grubb AF and Hankollari E. Cerebral metastasis of Merkel cell carcinoma following resection with negative margins and adjuvant external beam radiation: case report. J Med Case Rep. (2021) 15:118. doi: 10.1186/s13256-021-02690-z

32. Tran MN, Ratnayake G, Wong D, and McGrath LA. Conjunctival Merkel cell carcinoma: case report and review of the literature. Digit J Ophthalmol. (2022) 28:64–8. doi: 10.5693/djo.02.2022.02.003

33. Kotelnikova EF, Laus M, and Croce A. Evidence and considerations on treatment of small size Merkel cell head and neck carcinoma. Int Arch Otorhinolaryngol. (2020) 24:e487–91. doi: 10.1055/s-0040-1709114

34. Berkowitz A, Neuman T, Frenkel S, Eliashar R, Weinberger J, and Hirshoren N. FDG-PET/CT for spontaneous regression of metastatic Merkel cell carcinoma: friend or foe? Isr Med Assoc J. (2019) 21:63–4.

35. Chen L, Zhu L, Wu J, Lin T, Sun B, and He Y. Giant Merkel cell carcinoma of the eyelid: case report and review of the literature. World J Surg Oncol. (2011) 9:58. doi: 10.1186/1477-7819-9-58

36. Zhu G, Xie L, and Hu X. Imaging of Merkel cell carcinoma of the eyelid: a case report. Oncol Lett. (2024) 27:119. doi: 10.3892/ol.2024.14252

37. Zhan S, Nguyen M, and Hollsten J. Immune checkpoint inhibition as first-line therapy for localized eyelid Merkel cell carcinoma in a nonsurgical candidate. Can J Ophthalmol. (2024) 59:e183–4. doi: 10.1016/j.jcjo.2023.10.019

38. Komatsu Y, Kitaguchi Y, Kurashige M, Morimoto T, and Nishida K. Lower eyelid Merkel cell carcinoma in a non-immunocompromised young female: case report. Case Rep Ophthalmol. (2024) 15:437–42. doi: 10.1159/000536098

39. Furdová A, Michalková M, and Javorská L. Merkel cell carcinoma of the eyelid and orbit. Cesk Slov Oftalmol. (2018) 74:37–43. doi: 10.31348/2018/1/6-1-2018

40. Casey C, Gallo N, and Gallo S. Merkel cell carcinoma of the left eyelid with metastasis to the left submandibular lymph nodes: case report and brief review. Case Rep Ophthalmol Med. (2022) 2022:4712301. doi: 10.1155/2022/4712301

41. Atamney M, Gutman D, Fenig E, Gutman H, and Avisar I. Merkel cell carcinoma of the eyelid. Isr Med Assoc J. (2016) 18:126–8.

42. Riesco B, Cárdenas N, Sáez V, Torres G, Gallegos I, Dassori J, et al. Carcinoma palpebral de células de Merkel: serie de 5 casos y revisión. Arch Soc Esp Oftalmol. (2016) 91:56–64. doi: 10.1016/j.oftal.2015.11.008

43. Krásný J, Šach J, Kolín V, and Zikmund J. Merkel cell carcinoma of the eyelids: clinical–histological study. Cesk Slov Oftalmol. (2019) 74:198–205. doi: 10.31348/2018/5/5

44. Baccarani A, Pompei B, Pedone A, and Brombin A. Merkel cell carcinoma of the upper eyelid: presentation and management. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. (2013) 42:711–5. doi: 10.1016/j.ijom.2012.10.031

45. Yamanouchi D, Oshitari T, Nakamura Y, Yotsukura J, Asanagi K, Baba T, et al. Primary neuroendocrine carcinoma of ocular adnexa. Case Rep Ophthalmol Med. (2013) 2013:281351. doi: 10.1155/2013/281351

46. Hao S, Zhao S, and Bu X. Radioactive seed implantation in primary eyelid Merkel cell carcinoma. Can J Ophthalmol. (2016) 51:e31–3. doi: 10.1016/j.jcjo.2015.10.003

47. Shah JM, Sundar G, Tan KB, and Zee YK. Unusual Merkel cell carcinoma of the eyelid. Orbit. (2012) 31:425–7. doi: 10.3109/01676830.2012.689084

48. Toto V, Colapietra A, Alessandri-Bonetti M, Vincenzi B, Devirgiliis V, Panasiti V, et al. Upper eyelid Merkel cell carcinoma treated with neoadjuvant chemoteraphy and surgical excision. Arch Craniofac Surg. (2019) 2:121–5. doi: 10.7181/acfs.2018.02089

49. Iuliano A, Tranfa F, Clemente L, Fossataro F, and Strianese D. A case series of Merkel cell carcinoma of the eyelid: A rare entity often misdiagnosed. Orbit. (2019) 38:395–400. doi: 10.1080/01676830.2018.1537291

50. Russo C, Strianese D, Perrotta M, Iuliano A, Bernardo R, Romeo V, et al. Multi-parametric magnetic resonance imaging characterization of orbital lesions: A triple-blind study. Semin Ophthalmol. (2020) 35:95–102. doi: 10.1080/08820538.2020.1742358

51. Lanni V, Iuliano A, Fossataro F, Russo C, Uccello G, Tranfa F, et al. The role of ultrasonography in differential diagnosis of orbital lesions. J Ultrasound. (2021) 24:35–40. doi: 10.1007/s40477-020-00443-0

52. Bearzi E, Sola S, Defferrari C, Chiodi S, Di Meo N, and Massone C. Rate of growth of Merkel cell carcinoma: a unique photographic evidence. Dermatol. (2025). doi: 10.4081/dr.2025.10457

Keywords: eyelid neoplasm, immune checkpoint inhibitors, immunohistochemistry, Merkel cell carcinoma, Merkel cell polyomavirus, ocular adnexal tumor, periocular malignancy

Citation: Strianese D, Barbato C, Troisi M, Lanni V, Damiano V, Di Crescenzo RM, Passaro ML, D’Aponte A, Nubi R, Conson M, Cohen D, Mariniello G, Costagliola C and Iuliano A (2025) Optimizing surgical margins in the treatment of eyelid Merkel cell carcinoma: a tertiary center experience and literature review. Front. Ophthalmol. 5:1691372. doi: 10.3389/fopht.2025.1691372

Received: 23 August 2025; Accepted: 30 November 2025; Revised: 29 November 2025;

Published: 16 December 2025.

Edited by:

Farzad Pakdel, Tehran University of Medical Sciences, IranReviewed by:

Lilly Wagner, Mayo Clinic, United StatesP. Umar Farooq Baba, Sher-I-Kashmir Institute of Medical Sciences, India

Copyright © 2025 Strianese, Barbato, Troisi, Lanni, Damiano, Di Crescenzo, Passaro, D’Aponte, Nubi, Conson, Cohen, Mariniello, Costagliola and Iuliano. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Diego Strianese, ZGllZ28uc3RyaWFuZXNlQHVuaW5hLml0; Mario Troisi, dHJvaXNpMTY1QGdtYWlsLmNvbQ==

Diego Strianese

Diego Strianese Claudio Barbato

Claudio Barbato Mario Troisi

Mario Troisi Vittoria Lanni

Vittoria Lanni Vincenzo Damiano

Vincenzo Damiano Rosa Maria Di Crescenzo

Rosa Maria Di Crescenzo Maria Laura Passaro

Maria Laura Passaro Antonella D’Aponte1

Antonella D’Aponte1 Raffaele Nubi

Raffaele Nubi Manuel Conson

Manuel Conson Dana Cohen

Dana Cohen Ciro Costagliola

Ciro Costagliola Adriana Iuliano

Adriana Iuliano